Streetcars - Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia (original) (raw)

Essay

For more than 150 years streetcars have served the Philadelphia area and helped Center City Philadelphia retain its commercial, retail, and entertainment supremacy in an ever-expanding region. Although the motive power switched from horses to electricity (with short detours into steam and cable), most change has been evolutionary rather than revolutionary. Perhaps the greatest transformation took place in the early twentieth century when the combination of rising working-class wages and regulated fares allowed streetcars, once a middle-class means of transport, to become a key component of a truly heterogeneous mass transit system. Because of the streetcars’ importance to urban life, twice they played key roles in the civil rights movement in Philadelphia.

The horse-drawn streetcar was introduced in 1858 and operated in Philadelphia until around 1897, when electric trolley cars became a more reliable and less expensive alternative. (Library Company of Philadelphia)

The first streetcars in the region, running on steel rails and pulled by horses, began operating on the Frankford and Southwark Philadelphia City Passenger Railway Company on January 20, 1858. Quickly the routes pioneered by the first form of on-street public transportation, the omnibus, became street railways. The steel rails made for a smoother and a faster journey for passengers. The result for the operators was an expanded range, and fewer horses and cars were needed to maintain the level of service that the omnibus had provided.

By the early 1860s, streetcars had replaced omnibuses throughout the city. Streetcar fares were lower than those charged by the omnibuses but still remained high enough that most regular riders were middle class or above. Although streetcars were credited with allowing middle-class women to travel freely throughout the city, there were two notable restrictions on patronage in the early years: Blacks were not permitted to ride on the cars and there was no Sunday service. Between 1859 and 1867, after African Americans protested the racial restriction on ridership, a few lines allowed Black passengers (some on segregated cars). Although white passengers in the city voted to continue the racial restrictions, civil rights activists William Still (1821-1902) and Octavius Catto (1839-1871) moved the debate to Harrisburg and Pennsylvania opened the streetcars to all in March 1867. Also that year, Philadelphia became the last city in the country to institute Sunday streetcar service.

The City Expands

Expansion of Philadelphia’s streetcar network allowed middle-class families to move to new residential areas like West Philadelphia east of Fortieth Street and lower North Philadelphia. These developments in areas annexed to the city by the Consolidation of 1854 became the region’s first streetcar “suburbs.”

Streetcar service also expanded throughout the region in the 1850s and 1860s. The rails allowed the streetcars to operate in areas where poorly paved or unpaved streets had prevented omnibus service. Trenton, Camden, and Atlantic City in New Jersey had streetcars, as did Norristown and Darby in Pennsylvania.

By the Centennial year of 1876, Philadelphia could claim the largest street railway system in the country. Although true, this claim was also a result of the city’s many narrow, one-way streets that meant that many streetcars traveled out of the city on one street, then returned on another, thus doubling the length of track in use. But all was not well on the system despite an annual ridership of over 100 million passengers. In 1872 the Great Epizootic, a fast-moving equine flu, affected most horses throughout the nation. Although many horses recovered, the outbreak caused streetcar operators to consider other means of power. Operators first tried steam engines on the street railways in 1876 and 1877-8, but these were unsuccessful and unpopular.

In 1883 a trio of entrepreneurs, William Kemble (1828-1891), Peter A. B. Widener (1834-1915), and William Lukens Elkins (1832-1903), formed the Philadelphia Traction Company to acquire existing streetcar lines and convert them to cable operation. The higher costs of the cable car infrastructure started the consolidation of the various routes into larger concerns despite restrictions on mergers and cross-ownership (usually avoided by the use of long-term leases and holding companies).

By the mid-1880s, however, the electric trolley was invented and it was clearly the technology of the future. Unfortunately Philadelphia Traction’s investment in cable cars and the small size of most other companies contributed to Philadelphia’s slow adoption of trolleys (as did safety and aesthetic concerns among the public). Following the conservative Kemble’s death in 1891, Widener decided to abandon cable operation for electrification. The first electric line on Bainbridge and Catharine streets opened in 1892, and the horse cars made their final runs in Philadelphia just five years later. In 1895 Widener and Elkins formed the Union Traction Company and within three years it controlled nearly all the lines in the city. To help increase off-peak ridership, the company built a large amusement park at Willow Grove in the northern suburbs in 1896. One of the region’s other successful amusement parks, Woodside in Fairmount Park, was owned by the Fairmount Park Transportation Company, which operated a popular trolley line through the park from 1897 to 1946.

Beyond City Limits

Starting in the 1890s and continuing for the first two decades of the twentieth century trolleys expanded throughout Philadelphia’s suburbs. Initially from Sixty-third Street in West Philadelphia (and after 1907 from the Sixty-ninth Street Terminal in Upper Darby), routes of the Philadelphia & West Chester Traction (later known as “Red Arrow Lines”) went to West Chester (1899), Ardmore (1902), Media (1913), and Sharon Hill (1917). In Norristown routes from Berks County and the Lehigh Valley met lines from Philadelphia. Southern New Jersey developed its own intricate systems centered on Camden and Trenton.

The expansion of the lines, combined with the construction of the Market Street Subway-Elevated through West Philadelphia, allowed for “streetcar suburbs” to become commonplace throughout the region. In the city itself, middle-class development moved steadily in virtually all directions from the core. The Red Arrow Lines allowed for the development of much of Delaware County, and other trolley lines opened up portions of eastern Montgomery and southern Bucks counties in Pennsylvania. In Camden County, New Jersey, the Public Service Railway owned the bulk of the network that allowed for the development of suburbs like Collingswood and Haddonfield.

In order to build the Market Street Subway-Elevated, the Widener-Elkins interests formed the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (PRT) to take over Union Traction in 1902 and this new corporation and its financial structure would adversely affect the streetcars. The PRT struggled because of its huge debts and large annual lease payments and, in 1911, following two violent strikes, Thomas Eugene Mitten (1864-1929) (with the backing of the banking firm of Drexel, Morgan) took over the company. Mitten began to purchase new cars (known as the “Nearside Cars”), modernize the system, and improve both employee and passenger relations. From 1920 onward, however, expansion of the PRT’s trolley lines effectively came to a halt as the company switched to using buses and trackless trolleys on new routes.

Although suburban trolley service began to contract in the 1930s as lines closed and were replaced by buses, the PRT system in the city remained largely intact (as did the Red Arrow system in Delaware County). Following Mitten’s death in 1929, the PRT struggled again and declared bankruptcy in 1934. Near the end of its existence, the PRT in 1938 placed in service a small number of modern, streamlined streetcars: the PCCs. In 1940 the PRT reorganized as the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) under the control of Albert M. Greenfield (1887-1967), a real estate developer and civic leader, and continued to order PCC cars.

Shipyard workers during the Philadelphia Transportation Company strike in 1944 struggled to find daily transportation and often relied on the few military vehicles that attempted to replace normal streetcar and subway service. (Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries)

Wildcat Strike

On August 1, 1944, a wildcat strike took place on the PTC to protest the hiring of African Americans in skilled positions (such as motormen and conductors). The protest, the largest U.S. labor action during World War II, lasted for a week and adversely affected war production. The NAACP moved to end the strike quickly and worked with many community organizations to ensure equal treatment and moderate violence. Because of the strike’s impact on war production, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) authorized the Army to take control of the transit system and 5,000 heavily armed soldiers were sent to Philadelphia to end the strike.

After the end of WWII, the PTC bought more PCC cars to modernize its existing streetcar system. In 1955, National City Lines (owned by General Motors and oil and rubber companies) acquired control of the PTC and quickly replaced twenty-four trolley routes with buses and abandoned over two hundred miles of track.

Despite National City Lines’ efforts, Philadelphia retained a large network of trolleys through the 1970s. In 1968 the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) acquired the PTC and initially no changes took place in the existing streetcar network. However, in 1975 a fire at the Woodland car barn destroyed approximately sixty of the PCC cars and SEPTA began to abandon trolley routes again. Following the purchase of new streetcars for the subway-surface lines in West Philadelphia in the early 1980s, SEPTA retired its PCC cars and abandoned all remaining surface streetcars by 1992. In 2005, SEPTA rebuilt a small fleet of PCC cars and reintroduced streetcar service on the Route 15 between Port Richmond and West Philadelphia via the Philadelphia Zoo.

In the suburbs, very few streetcars lines survived the Great Depression. The notable exception was the Red Arrow system radiating from Sixty-ninth Street Terminal. Although buses replaced the trolleys to West Chester in 1954 and Ardmore in 1966, the two remaining routes (to Media and Sharon Hill) are today still operated by SEPTA, which acquired Red Arrow in 1970. Starting in 1981, SEPTA reequipped both lines with a fleet of trolleys similar to the cars used on the subway-surface lines in the city.

John Hepp is associate professor of history and co-chair of the Division of Global History and Languages at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where he teaches American urban and cultural history with an emphasis on the period 1800 to 1940. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

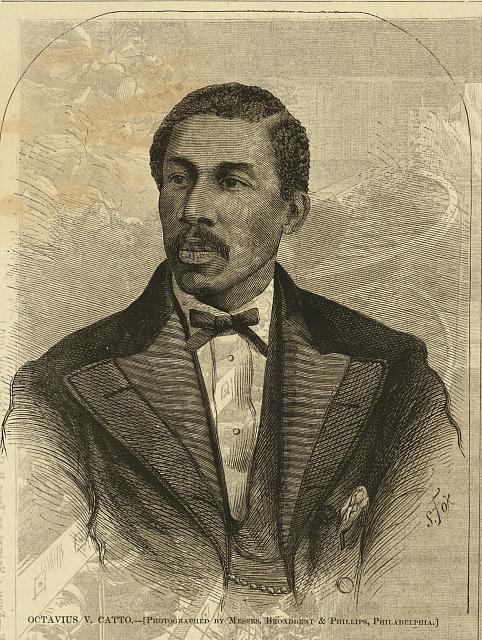

Octavius V. Catto

Even though the horse-drawn streetcar opened public transportation to more people, African Americans in Philadelphia were banned from riding any streetcar. Any African Americans who attempted to ride the streetcar were refused service and removed from the car. African American women, working together through local church organizations, actively worked against this policy in Philadelphia by repeatedly attempting to ride streetcars and filing petitions against the segregation law in local court. Once the Civil War started, African American women in Philadelphia began to push for ridership on streetcars with increased frequency, arguing that streetcar rides were essential to transport or visit African American soldiers to hospitals and camps. Within this setting, one of the lead participants in changing the segregated policy of Philadelphia's streetcars was Octavius V. Catto.

Octavius Catto was born, free from slavery, on February 22, 1839 in South Carolina. His family moved to Philadelphia when he was five years old, as his father became the minister of the First African Presbyterian Church. Catto attended a number of segregated public schools, briefly attended an all-white middle school in Allentown, New Jersey, and finished his education at the The Institute for Colored Youth (the precursor to the current Cheney University). Catto was the fourth student to graduate from the Institute in 1858, and within a year became an lecturer at the Institute. The Institute was a prominent center for the African American intellectual community in the greater Philadelphia area, and Catto used his position to become deeply involved with the African American community. Catto focused his career on educating members of the community and strived to build progress for African Americans in a culture that was heavily prejudiced against them. During the Civil War, Catto helped organize eleven regiments of the United States Colored Troops, and was elevated to the position of Major.

After the Civil War, Octavius Catto became involved in civil rights on the state level. Catto served as the Secretary of the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League and Vice President of the State Convention of Colored People in 1865. It was around the summer of 1865 that the streetcar issue dominated Catto's goals. Protests surrounding the prevention of African Americans on streetcars within Philadelphia (and elsewhere around Pennsylvania) had been occurring for years, but they began to grow in intensity after the end of the Civil War. While African Americans were committing non-violent protests on streetcars and at transportation terminals, Catto joined with a group from the Equal Rights League in early 1866 to lobby elected officials in Harrisburg. In March of 1867, a law was passed that prevented transportation operators from removing people based on their skin color. Just three days later, the law was tested as Catto's fiancé Caroline LeCount was refused service on a streetcar. The state law was upheld and the conductor was arrested and fined for his actions.

Catto was shot on his way to vote in October 1871. Groups of white Democrats (including a number of police officers) attempted to intimidate the black population of Philadelphia from voting by harassing them on their way to the polls. Catto was walking down South Street when he was confronted by a white male, later identified as Frank Kelly, and the confrontation ended when Catto was shot three times.

-Text by Joshua Lisowski

Horse-Drawn Streetcar

Library Company of Philadelphia

The horse-drawn streetcar, introduced in 1858, moved along a set of tracks, which improved upon the early omnibus by providing a smoother ride with faster travel speeds for the customers, regardless of the conditions of the road. Faster travel meant that middle-class workers could move into new residential areas, such as to the north of Center City or to West Philadelphia (east of Fortieth Street). Streetcar fares were lower than the omnibus, but still too expensive for members of the working-classes to use on daily basis. Horse-drawn streetcars operated in Philadelphia until around 1897, when electric trolley cars became a more reliable and less expensive alternative. The streetcar shown here at Sixth and Jackson Street in 1894 demonstrates how streetcars typically operated with two horses, a driver, and a conductor.

First Electric Trolley

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Although the electric trolley was developed in the 1880s, it did not appear in Philadelphia until the 1890s because the Philadelphia Traction Company had invested in cable streetcars during the 1880s. The first electric trolley line began operation in 1892, and by 1898 the Union Traction Company (owned by Peter A.B. Widener and William Lukens of the Philadelphia Traction Company) purchased and changed a majority of streetcar routes in Philadelphia to electric lines. The electrification of the streetcar required electrified cables along each route and new trolley cars, like Philadelphia Traction Company car shown pictured here in 1892, but the result was a cheaper transportation system that appealed to the masses of Philadelphia. Electric trolleys were not limited by the stamina of a horse, and they could operate all day on extended routes for a lower price. Lower prices to ride the electric trolley meant that the working class could take advantage of the transportation system on a regular basis, and the number of trolley routes expanded until the 1930s.

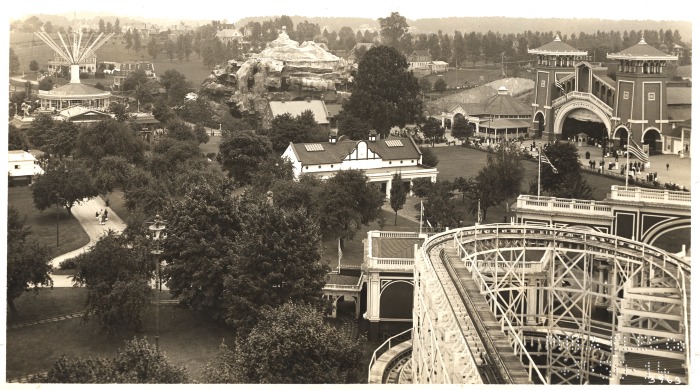

Willow Grove Amusement Park

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Willow Grove Amusement Park: After Peter A. B. Widener and William Lukens established the Union Traction Company and popularized electric trolley cars in Philadelphia, they established the Willow Grove Amusement Park. Pictured here in 1914, Willow Grove Amusement Park opened in 1895 to increase traffic on the electric trolley on weekends and holidays. Willow Grove Park maintained a high-class image while being affordable to the middle class. Staff members wore suits and dresses, rowdy customers were promptly removed from the park, and concerts featuring high-brow music were performed on a regular basis. Willow Grove Park was a success for the Union Traction Company but was sold to a private investor in 1926. The electric trolley still provided the primary mode of transportation to the park.

Philadelphia Transportation Company Strike

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

During the summer of 1944, the electric streetcars of the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) were at the center of the largest transportation labor strike in Philadelphia during World War II. At the end of July 1944, the PTC hired seven African American drivers to fill vacant jobs as conductors and motormen, due in part to the labor shortage during the war. By the first day of August, white members of the PTC began to strike to protest the placement of African Americans in skilled positions. The strike halted public transportation systems in Philadelphia and the result can be seen in photographs like this one, taken on Broad Street on the first day of the strike. Many of these workers in the photograph worked at the shipyards on the Delaware River. Workers who lived outside of Center City Philadelphia due to the relatively low cost of public transportation were stranded because of the PTC strike and had to wait for the few buses that were still operational. The limited availability of public transportation had an adverse affect on war production plants in the Philadelphia area. Military production plants lost millions of working hours as people struggled to find transportation to their jobs. By August 3, President Roosevelt authorized the Army to take control of the transit system and authorized military vehicles to transport people to military production plants.

Philadelphia Transportation Company Riot Vandalism

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

Although the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) strike was racially motivated, it did not expand into a riot like those experienced in some other American cities during World War II. African Americans in Philadelphia, the NAACP, and local community organizations took action to end the strike quickly without excessive violence. Some vandalism occurred, as shown in this photograph of one of fifty windows broken by demonstrators along Ridge Avenue in North Philadelphia. Within a week after the strike began, PTC's service of subways, trolley cars, and bus resumed their typical schedule.

Themes

Time Periods

- Twenty-First Century

- Twentieth Century after 1945

- Twentieth Century to 1945

- Nineteenth Century after 1854

Locations

Essays

- Red Arrow Lines

- Horses

- General Strike of 1910

- SEPTA

- Omnibuses

- Subways and Elevated Lines

- Buses

- Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) Strike

- Public Transportation

Cheape, Charles W. Moving the Masses: Urban Public Transit in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, 1880-1912. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Cox, Harold E. Surface cars of Philadelphia, 1911-1965. Privately published, 1965.

_____. The Fairmount Park trolley: A unique Philadelphia experiment. Privately published, 1970.

_____. Philadelphia car routes: Horse, cable, electric. Privately published, 1982.

_____ and Stanley Bowman. The Trolleys of Chester County, Pennsylvania. Privately published, 1975.

_____ and Harry Foesig. Trolleys of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Privately published, 1968.

Cudahy, Brian J. Cash, Tokens, and Transfers: A History of Urban Mass Transit in North America. New York: Fordham University Press, 1990.

Hepp, IV, John H. The Middle-Class City: Transforming Space and Time in Philadelphia, 1876-1926. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

Hilton, George W. “Transport Technology and the Urban Pattern,” Journal of Contemporary History (1969), 4:123-135.

Speirs, Frederick W. “The Street Railway System of Philadelphia, Its History and Present Condition,” Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science, Fifteenth Series. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1897.

Related Collections

- John Gibb Smith, Jr., Collection - Print and Picture Collection

Free Library of Philadelphia

1901 Vine Street, Philadelphia. - Samuel Castner Collection

Free Library of Philadelphia

1901 Vine Street, Philadelphia. - Harold E. Cox Transportation Collection (3158)

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia. - Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company Brochures

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia. - John F. Tucker Transit Collection (Accession 2046)

Hagley Museum and Library

Wilmington, Del.

Related Places

- Sixty-Ninth Street Transportation Center (Media and Sharon Hill Lines)

- Trolley Stations throughout the SEPTA system

- PCC Trolley on display in SEPTA Museum

- Electric City Trolley Museum (Philadelphia area trolleys in collection)