University City Science Center - Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia (original) (raw)

Essay

The University City Science Center, the nation’s first and oldest urban research park, represents a pivotal chapter in the story of American urban renewal, its associated racial tensions, and the important role played by institutions of higher education. Established in 1960 in West Philadelphia adjacent to and intertwining the campuses of the University of Pennsylvania and Drexel University as part of an urban renewal zone, the Science Center expanded to include sixteen buildings on its seventeen-acre campus, becoming in the process a key player in the economic and cultural vitality of University City.

The University City Science Center was constructed on Unit 3, a parcel of land between the Powelton Village and Mantua neighborhoods of West Philadelphia and the campus of the University of Pennsylvania. This area became known as University City after its construction. (Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries)

The University City Science Center was conceived as part of “Unit 3,” an urban renewal zone established by the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority that included the West Philadelphia blocks from Powelton and Lancaster Avenues south to Chestnut Street between Thirty-Fourth and Fortieth Streets. The properties were redeveloped in conjunction with the West Philadelphia Corporation, an institutional coalition that included the University of Pennsylvania as the senior partner and the Drexel Institute of Technology (now Drexel University), the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science (the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia), Presbyterian Hospital (Penn Presbyterian Medical Center), and the Osteopathic Medical School (Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine) as the junior partners.

Planners envisaged the University City Science Center as a catalyst for the economic, cultural, and scholarly efflorescence of University City, a brand name and marketing gambit they devised for the blocks that included or bordered on the West Philadelphia Corporation’s member institutions. As recruitment magnets for the Science Center and the scientists and scholars they hoped to attract, the West Philadelphia Corporation dedicated human and monetary capital across University City to school-improvement initiatives, housing conservation, and condominium developments, a guaranteed mortgage plan for University of Pennsylvania employees, arts and culture, beautification, recreation, and retail and restaurant development in the Walnut Street corridor. The Science Center was to rise one block deep along both sides of Market Street between Thirty-Fourth and Thirty-Eighth Streets and below Market between Thirty-Ninth and Fortieth Streets. According to Jean Paul Mather (1914–2007), the Science Center’s first president, research and development was the center’s primary objective—either through its own efforts or by facilitating office or laboratory space for industry, independent foundations, and member institutions.

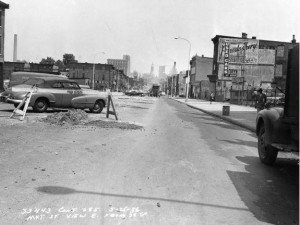

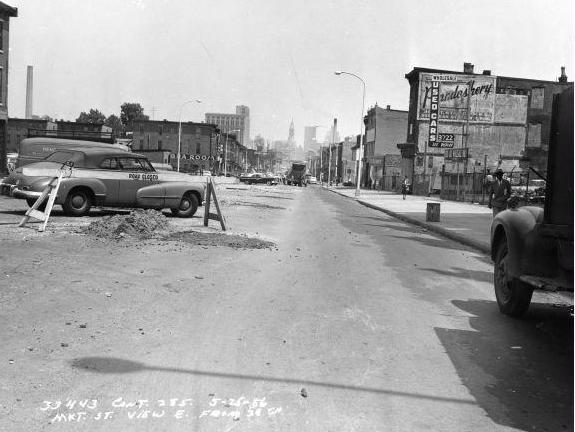

Market Street in the University City neighborhood was a mixed residential and commercial district known as the Black Bottom before the University City Science Center was constructed. (PhillyHistory.org)

Previously established university-related research parks that might have served as models were located in spacious, bucolic surroundings. While University City planners did not discount the extraordinary advantage that swaths of pastoral landscape conveyed to Stanford University’s Industrial Park, which included such wildly successful tenants as Hewlett-Packard, General Electric, and Lockheed, or to the heavily wooded Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, they gambled that the University of Pennsylvania’s brand and the promise of urban amenities would convey a distinct advantage for recruiting high-tech industries. In the fall of 1963, the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas approved articles of incorporation for the University City Science Center and the University City Science Center Institute. The Science Center was the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority’s designated real estate developer for the entire complex. In this role, the Science Center assumed the obligation under the urban renewal plan for Unit 3 to put up buildings “within a reasonable time as determined by the Redevelopment Authority” on properties it acquired from the authority. The Science Center Institute, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Science Center, was to conduct its own research and development under Science Center management. Recognizing from the start that the project would rise or fall on its ability to attract the research arms of major corporations such as IBM and General Electric to the Market Street corridor, planners assigned the highest priority to recruiting such organizations.

Racial Demographics

Science Center planners denied charges that they conspired to construct a buffer zone that would insulate Penn from working-poor blacks in Mantua and Belmont, neighborhoods north of Unit 3. Yet there was no denying that the type of professionals the Science Center hoped to recruit would be overwhelmingly white, simply by virtue of the racial demographics of higher education and the learned professions of the 1960s. Unit 3 redevelopment, with the University City Science Center at its core, thus effectively created a barrier between Penn and its neighbors to the north.

As demolitions began to displace working-poor blacks in the Market Street corridor, a neighborhood known locally as the Black Bottom, racial politics flared. Of the 2,653 people displaced in Unit 3, roughly 78 percent were black. The Science Center and the projected Science Center-affiliated University City High School caused just over half of the total Unit 3 displacements. Protests by displaced residents and their West Philadelphia allies, including student demonstrators at Penn, fell on deaf ears at the Redevelopment Authority and the West Philadelphia Corporation, which managed the affair with hubris and insensitivity to the probable consequences of the removals, one of which was to be lasting damage to Penn’s community relations.

The University City Science Center operated out of a converted industrial building in its earliest days. It was not until 1969 that the first purpose-built structure was completed. (Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries)

Adding to the original membership, the Science Center evolved as a consortium of some thirty-one educational and medical institutions throughout the Delaware Valley, although the University of Pennsylvania continued to hold a majority of the corporation’s stock in the 1960s and a plurality of its stock thereafter. Headquartered in a converted industrial building purchased in 1965, the Science Center opened its first new building in 1969 and successfully recruited the Monell Chemical Senses Center to its complex in April 1971. Despite that initial success, other major corporations with research and development departments, apparently wary of an area they regarded as a vestigial slum, failed to follow.

In its early years, the Science Center was undercapitalized and under constant pressure from the Redevelopment Authority to put up buildings regardless of their function. To meet its payroll and to hold the Redevelopment Authority at bay, the center reconfigured itself as a real estate operation by offering space to organizations regardless of whether they had a research focus. The General Services Administration, for example, constructed a fifteen-story office building on the corner of Thirty-Sixth and Market Streets to house the regional units of four federal agencies—a purpose that had nothing to do with research or development.

Strategic Redirection

Randall Whaley (c.1916–89), a technology innovator, became president of the Science Center in 1970, by which time the center was financially beleaguered and losing $30,000 per month. Under Whaley’s leadership, however, the center achieved financial stability, reporting its first operating surplus in 1973. As his signal contribution, Whaley restructured the Science Center as the nation’s first small business incubator in science and technology. In 1983, the Science Center was designated an Advanced Technology Center for Southeastern Pennsylvania (ATC/SEP)—one of four regional ATCs established under the auspices of the Commonwealth’s Ben Franklin Partnership (later renamed the Ben Franklin Technology Partners), created by Gov. Richard Thornburgh (b. 1932) in 1982. Consistent with the partnership’s guidelines, the ATC/SEP developed an incubator program with business-development support services. Contrary to the original vision of national research laboratories occupying single buildings, emphasis shifted to start-up ventures housed in multi-tenant buildings. By 1984, the incubator had launched forty-four small businesses; by the spring of 1987, the total number was 106 start-ups.

Plans to demolish Unit 3, an urban renewal zone established by the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, for the construction of the University City Science Center met with resistance from the community. Demolition of Unit 3 would require the displacement of the residents of the Black Bottom, a largely working-class African American neighborhood along the Market Street corridor. The Redevelopment Authority held meetings with the community, such as this one in 1965 at the Drew School, in advance of the demolitions, but residents’ pleas were to no avail. The neighborhood was declared blighted and demolished. (Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries)

By 1984 the center boasted nine buildings in the Market Street corridor between Thirty-Fourth and Thirty-Ninth Streets and counted twenty-eight colleges, universities, and hospitals as shareholders. By 1988, the number of organizations it hosted was up to 105, employing over six thousand people. The center’s total capital investment reached more than 90million,returningmorethan90 million, returning more than 90million,returningmorethan68 million in cumulative city wage and real estate taxes. The center did manage to attract some research and development activity, including a number of federally funded research projects sponsored by the University City Science Institute and projects among tenants such as the Connective Tissue Research Center (for example, research on the structure, immunology and molecular biology of basement membranes in diabetes, a study of lung endothelial cells’ response to infection and injury) and NASA’s Bioprocessing and Pharmaceutical Research Institute (research on processing pharmaceuticals and biological materials in space). Yet over the years, it remained dependent on non-R&Dentities to balance its books. Organizations such as the Otis Elevator Company, the Radiation Management Corporation, the John Hancock Health Plan, and the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools claimed significant space there.

Although they were usually able to find tenants for the existing multistory office buildings, Whaley and his board were continuously stymied by a lack of funds to complete the research park. A development first proposed in 1965, deemed essential to the Science Center’s claim to be a bona fide, world-class research park, was the World Forum for Science and Human Affairs. Conceived as the Science Center’s signature development, this initiative would have featured a spectacular residential hotel with state-of-the-art facilities for conferences, seminars, and continuing education programs. Whaley, a high-minded thinker, undaunted optimist, and crusader for innovation, latched onto the idea shortly after his arrival in 1970, and it remained his idée fixe until his retirement in 1985, even as the project siphoned off time and money from other projects. Every developer who considered taking on the project ultimately backed away, however. As one deal after another fell through and the requisite financing never materialized, the center finally shelved the project in 1992.

In the summer of 1983, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority extended the Science Center’s contract for fifteen years, giving the corporation a grace period within which to complete the research park. The center subsequently leased its leveled properties between Thirty-Sixth and Thirty-Eighth Streets to the Parkway Corporation, which laid down parking lots. In the following decade, the Science Center confronted a loss of R&D dollars and an outmigration of many of its resident technology companies to suburban Pennsylvania, an exodus attributed to the burden of the city’s wage tax and the lack of flexible facilities—for example, laboratories and light manufacturing space—in the mid-rise research park.

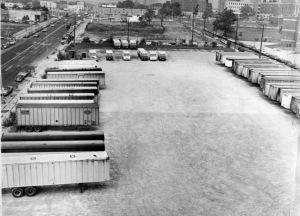

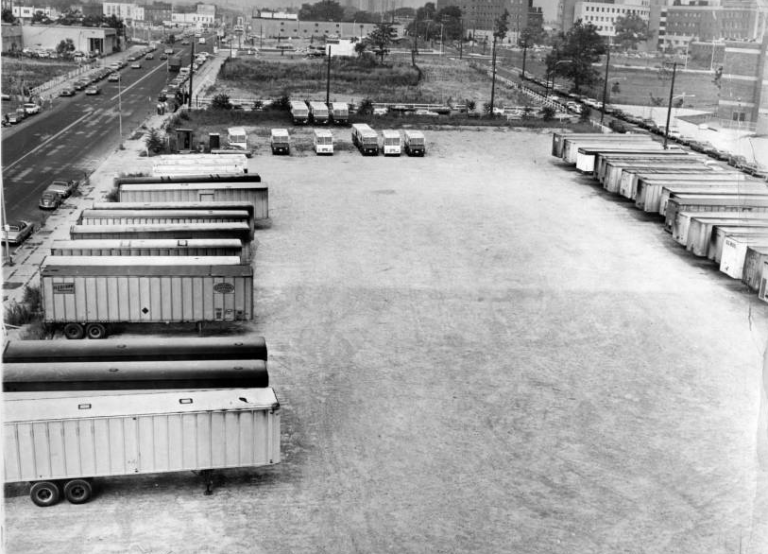

The World Forum for Science and Human Affairs was to be a splendid residential hotel offering conference spaces, state-of-the-art technology and continuing education classes. Though a site was cleared for the project in 1967-68, the ground was never broken and it was officially canceled in 1992. The site was used as a surface parking lot until the 2010s. (Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries)

Renaissance

In the mid-1990s, on the wings of the Clinton-era economy, the Science Center experienced a financial resurgence and physical growth spurt that continued, with the exception of the 2008 recession, for the next twenty years. In these decades, the center also benefited from a national zeitgeist that favored the revitalization of core areas of once historically vital cities in the Northeast Corridor. Urban research parks adjacent to major universities were suddenly au courant. The Science Center emerged as a major player in a University City building boom that began with the University of Pennsylvania’s commercial redevelopment of Walnut Street at the turn of the millennium and culminated with Drexel’s dramatic expansion and commercial redevelopment along Chestnut and Market Streets. Forming a phalanx of anchor institutions along a two-mile swath of the Schuylkill River’s west bank, Penn, Drexel, and the Science Center complemented, and intertwined with, each other’s astonishing growth. University City was poised to challenge Center City as a hub of urban redevelopment.

Commensurate with Randall Whaley’s vision of a science and technology incubator, in 2000 the Science Center debuted an eight-story building at 3711 Market Street housing the Port Business Incubator, organized to assist start-ups in biotechnology and information technology. Additions to the incubator included Quorum, a program that provided informal meeting spaces and liaison services for matching entrepreneurs and investors, and QED Proof-of-Concept, a program designed to help academic researchers in the life sciences and healthcare fields develop commercially viable information technologies. Drexel and the Science Center opened a 17,500 square-foot Innovation Center for business incubation on two floors of 3401 Market, a building that shared Thirty-Fourth Street with the rapidly growing Drexel campus.

By the mid-2010s, the Science Center had become a thriving engine of economic development for high-wage and middle-wage workers on the corporation’s Market Street campus. It was also a boon for talented entrepreneurs striving to launch small businesses in life sciences, clean tech, IT, bioinformatics, nanotechnology, and diagnostics and devices, as well as for the employees of these incubated businesses and their clientele. Two new buildings along the north side of Market between Thirty-Seventh and Thirty-Eighth Streets served as bulwarks of the Penn Health System—3701 Market Street for outpatient primary care and 3737 Market, a sparkling eleven-story tower that houses the Penn Presbyterian Medical Center’s integrative specialty medical services and outpatient treatment options. A low-rise “flex” building with laboratory and other tailorable spaces opened at 3615 Market. Drexel acquired a Science Center building in the 3401 block of Market, formerly the Institute for Scientific Research, a research indexing service, for its College of Media Arts and Design. The eyesore surface parking lot on the 3601 block of Market to Filbert, once earmarked for the Whaley’s World Forum, became the site of a twenty-eight–story postmodernist apartment tower with ground-story retail development.

In the planning stage in 2016 was uCity Square, a development formed in partnership with Wexford Science and Technology, a biomedical realty company. Bounded by Thirty-Seventh and Thirty-Eighth Streets between the line of Filbert and the point where Powelton Avenue joined Lancaster Avenue, it was designed to be a vibrant live/work/play neighborhood of postmodern residential buildings, a high-end grocery store, boutique retail venues, and interior walkways and public spaces. However, for all the realized and potential economic benefits of the University City Science Center, an open question remained as to whether its major reorganization of urban space and displacements of West Philadelphia’s poor and minority residents would help mitigate Philadelphia’s status as the nation’s poorest large city and the city with the highest level of deep poverty.

John L. Puckett is a professor in the Education, Culture, and Society Division of the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education. A co-founder of the Netter Center for Community Partnerships, he teaches academically-based community service courses at Penn, and he has been active in community organizing around schools in West Philadelphia. Among other books, he is a co-author of Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950–2000 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015) and Dewey’s Dream: Universities and Democracies in an Age of Education Reform (Temple University Press, 2007). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Market Street Before Construction of the University City Science Center

Prior to the construction of the University City Science Center, the Market Street corridor was a low-income, mixed residential and commercial district largely populated by working-class African Americans. The neighborhood was densely constructed with two- and three-story row houses and tenement buildings, many with retail and local-service operations on their ground floors.

The Science Center was conceived during an ambitious wave of urban renewal in the 1960s that sought to reverse the city's decline by attracting middle class residents, many of whom had left for the suburbs in the decades following World War II, back into the city. West Philadelphia’s Market Street corridor was one of the areas targeted for urban renewal. In conjunction with the Redevelopment Authority, the Science Center was organized by planners of the West Philadelphia Corporation, a nonprofit entity that served the area’s higher education and medical institutions and was dominated by the University of Pennsylvania.

Community Meeting with the Redevelopment Authority, 1965

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

Plans to demolish Unit 3, an urban renewal zone established by the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, for the construction of the University City Science Center met with resistance from the community. Demolition of Unit 3 would require the displacement of the residents of the Black Bottom, a largely working-class African American neighborhood along the Market Street corridor. The Redevelopment Authority held meetings with the community, such as this one in 1965 at the Drew School, in advance of the demolitions, but residents' pleas were to no avail. The neighborhood was declared blighted and demolished.

Aerial View of the Science Center Under Construction

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

This 1968 aerial photograph shows the University City Science Center in its early days. The project required the demolition of residences along Market, Filbert, and Warren Streets. Just over half of the displacements caused by the project took place to clear the land for the University City High School, shown here bordered by a trapezoidal fence in the lower left. Planned during an ambitious period of public school reforms in Philadelphia, the University City High School was to serve as a magnet school, attracting top-tier math and science students from across the region. The curriculum would offer a unique, individualized program for each student, without schedules or structured class periods.

Community friction combined with overcrowding in other schools and a change in the city's political climate subverted these lofty goals. University City High School opened in 1971 and was quickly forced to abandon its high-toned curriculum as an influx of new students from neighboring schools transferred to the new facility, regardless of academic aptitude. Difficulties staffing the new school adequately led to violence, including a 1972 incident where the student body took over the school and the Philadelphia Police Department's gang-control units were forced to intervene. The school's reputation was permanently tarnished. It closed in 2013 and was demolished.

Residences Cleared for Construction

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

Despite community opposition, the Black Bottom neighborhood was demolished for the construction of the University City Science Center. This photograph shows two clusters of houses standing, awaiting the relocation of the families residing in them. Since 1984 and continuing into the twenty-first century, the former residents of the Black Bottom and their families convened annually for a picnic in remembrance of the neighborhood. The picnic, held in Fairmount Park, was made official in 1999, when the Philadelphia City Council recognized the second Sunday in August as Black Bottom Day.

University of Pennsylvania Students Hold a Sit-in

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

The construction of the University City Science Center displaced residents of the Black Bottom, a predominantly African American neighborhood. The Black Bottom was located in the Market Street corridor between the campus of the University of Pennsylvania and the Powelton Village and Mantua neighborhoods of West Philadelphia. The Black Bottom blocks were condemned as blighted by the Redevelopment Authority, in accord with the authority’s urban renewal plan for “Unit 3.” This plan was coordinated with the West Philadelphia Corporation, a nonprofit entity that acted on behalf of the area’s higher education and medical institutions, notably the University of Pennsylvania. In 1967–68, the Black Bottom blocks were razed, the displaced residents were relocated in a haphazard way to other parts of West Philadelphia, and construction of the Science Center’s first new building was completed in 1969.

Protests against the displacements came not only from Black Bottom residents but also from students. This photograph from February 1969 shows student demonstrators from Penn and other Delaware Valley colleges and universities at a sit-in at Penn’s College Hall. The sit-in came too late to halt the Unit 3 removals. One of its primary aims was to force the Science Center to build high-quality, low-income housing units on its property. The students won that demand, although fifteen years would pass before low-income housing would be built; the units were located in the block bounded by Market, Chestnut, Thirty-Ninth, and Fortieth Streets on land the Science Center reverted to the city for public housing.

University City Science Center Under Construction

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

The University City Science Center operated out of converted warehouse spaces in its earliest days. It was not until 1969 that the first purpose-built structures were completed. An early deal in 1971 with Monell Chemical Sense Center, shown here under construction, helped the science center expand its facilities along the Market Street corridor. Other early expansion plans were abandoned as few businesses joined, apparently wary of the surrounding neighborhoods. The Science Center was forced to lease space to any organization willing to rent it, including those that had nothing to do with science and technology, in order to pay its bills. It took several decades before the University City Science Center was able to operate profitably.

World Forum for Science and Human Affairs Site, 1973

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

First proposed in 1965, the World Forum for Science and Human Affairs was to be a splendid residential hotel offering conference spaces, state-of-the-art technology, and continuing education classes. It was to be the University City Science Center's signature development, but lack of funding delayed its construction. In 1970, when Randall Whaley became the president of the Science Center, he initiated a renewed effort to construct the World Forum. Land was cleared for construction in 1967-68 (as seen in this 1973 photograph), but ground was never broken. Whaley remained transfixed on the project until his retirement in 1985. Funding deals fell through time and again, and the project languished until it was officially shelved in 1992. The site was used as a surface parking lot until the 2010s.

Themes

Time Periods

Locations

Essays

- Co-Working Spaces

- Gentrification

- Market Street

- Office Buildings

- Pharmaceutical Industry

- Urban Renewal

- West Philadelphia

- Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC)

Birch, Eugenie L. “From Science Parks to Innovation Districts: Research Facility Development in Legacy Cities on the Northeast Corridor,” Working Paper 2015/008. Philadelphia: Penn Institute for Urban Research, August 2015.

O’Mara, Margaret Pugh. Cities of Knowledge: Cold War Science and the Search for the Next Silicon Valley. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Puckett, John L. and Mark Frazier Lloyd. Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950–2000. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

——— . “Penn’s Great Expansion: Postwar Urban Renewal and the Alliance between Private Universities and the Public Sector.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 137, no. 4 (2013): 381–430.

Saffron, Inga. “Changing Skyline: University City Reinvents Itself—Again—with Apartments, Offices and Shops,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 29 January 2016.

Minutes of the Board of Directors, 1964–2004, University City Science Center, 3711 Market Street, Philadelphia. (Courtesy of University City Science Center, not publicly available.)

Related Collections

- University City, Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection, and West Philadelphia Corporation, Acc. 350

Urban Archives Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Charles Library

1900 N. Thirteenth Street, Philadelphia. - Redevelopment Authority of the City of Philadelphia, annual reports, 1950–1970, University of Pennsylvania

Fisher Fine Arts Library

220 S. Thirty-Fourth Street, Philadelphia. - West Philadelphia Corporation and University City Science Center, UPA 4

Office of the President of the University of Pennsylvania, University Archives and Records Center

3401 Market Street, Philadelphia.

Related Places

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Quorum plays matchmaker for Philly investors, clean energy startups (WHYY, October 3, 2012)

- University City Science Center names 7 startups for digital health accelerator (WHYY, July 16, 2014)

- University City Science Center plans expansion that will double its size (WHYY, June 2, 2015)

- Building Philadelphia's startup generation (WHYY, September 2, 2015)

- University City Science Center recasts two blocks of 37th as place to hang out (WHYY, December 2, 2015)