Evaluation and Treatment of Obesity and Its Comorbidities: 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity (original) (raw)

Abstract

The goal of the 8th edition of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity is to help primary care physician provide safe, effective care to patients with obesity by offering evidence-based recommendations to improve the quality of treatment. The Committee for Clinical Practice Guidelines comprised individuals with multidisciplinary expertise in obesity management. A steering board of seven experts oversaw the entire project. Recommendations were developed as the answers to key questions formulated in patient/problem, intervention, comparison, outcomes (PICO) format. Guidelines underwent multi-level review and cross-checking and received endorsement from relevant scientific societies. This edition of the guidelines includes criteria for diagnosing obesity, abdominal obesity, and metabolic syndrome; evaluation of obesity and its complications; weight loss goals; and treatment options such as diet, exercise, behavioral therapy, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric and metabolic surgery for Korean people with obesity. Compared to the previous edition of the guidelines, the current edition includes five new topics to keep up with the constantly evolving field of obesity: diagnosis of obesity, obesity in women, obesity in patients with mental illness, weight maintenance after weight loss, and the use of information and communication technology-based interventions for obesity treatment. This edition of the guidelines features has improved organization, more clearly linking key questions in PICO format to recommendations and key references. We are confident that these new Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity will be a valuable resource for all healthcare professionals as they describe the most current and evidence-based treatment options for obesity in a well-organized format. Click here to check the Graphical Abstract.

Keywords: Obesity, Practice guideline, Republic of Korea, Diagnosis, Therapeutics, Comorbidity

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of obesity is rapidly increasing in Korea, with the current obesity epidemic in the country characterized by a rapid increase in morbid obesity and obesity in children, adolescents, and young adults.1 This is a worrying trend as obesity is associated with a range of comorbidities such as diabetes and heart disease.2,3 While prevention of obesity is important in managing the condition, treatment also becomes crucial in controlling obesity-related comorbidities.4 It is vital that both prevention and treatment strategies be implemented to effectively combat the obesity epidemic in Korea. This will help to improve personal and public health in the long-term.5

The target audience of “Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity 2022” is primary healthcare professionals, including primary care physician who manage adults, children, and adolescents with obesity living in Korea. The guidelines have two main objectives. The first is to provide evidence-based recommendations that can assist primary care physicians in making safe and effective clinical decisions. To accomplish this, the guidelines are clear in their level of evidence and consider the balance between benefits and harms. The second objective is to improve the quality of care by providing high-quality, evidence-based information that helps primary care physicians avoid unnecessary and risky treatments, ultimately leading to better outcomes for patients.

METHODS

Development process

“Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity 2022” is the 8th edition of obesity management guidelines published by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity (KSSO). To evaluate the 7th edition and gather opinions on appropriate updates for the 8th edition, a survey was conducted of members of the Committee of Clinical Practice Guidelines and executive members of KSSO. As a result, five new topics were added: diagnosis of obesity, obesity in women, obesity in patients with mental illness, weight maintenance after weight loss, and obesity treatment using information and communication technology (ICT)-based interventions. As a result, the 8th edition of the guidelines now includes 14 topics.

The development period of the guidelines was from January 2021 to November 2022. Adaptation guideline development was applied to develop this edition of the guidelines according to the manual of the Korean Ministry of Health & Welfare and Korean Academy of Medical Science.6 The recommendations provided are clear and easy to understand.

Steering board

A steering board comprising seven experts was established to oversee the entire project and planned and confirmed all processes. The adequacy of key questions was discussed with their authors and the steering board to ensure relevance and appropriateness. Conflicts among authors and reviewers regarding recommendations were resolved with the steering board’s guidance to ensure that all final recommendations are fair and unbiased. The steering board played a crucial role in ensuring the success and integrity of the project by providing oversight and resolving any issues.

Personnel involved in the development of the guidelines

The Committee of Clinical Practice Guidelines comprised multidisciplinary experts in obesity management including family physicians, endocrinologists, clinical nutritionists, exercise specialists, pediatricians, surgeons, and psychiatrists. All members of the committee received education on developing clinical practice guidelines, developing key questions, and writing recommendations through literature review, through participation in multiple workshops. To effectively develop clinical practice guidelines, tasks such as literature and previous guidelines screening, evaluation of selected guidelines, and extraction of evidence for deriving recommendations were carried out by the committee members based on their professional areas of expertise. We used the extracted evidence to derive recommendations and develop clinical guidelines.

Key questions

The key questions for each topic were developed using the patient/ problem, intervention, comparison, outcomes (PICO) format so that the answers could be used as recommendations. This format clearly presents alternatives depending on the target population and clinical condition being addressed. Key questions and their corresponding recommendations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key questions and recommendations

| 1. Diagnosis of obesity |

|---|

| Q1-1. Is measuring BMI in adults an appropriate way to evaluate the risk of obesity-related comorbidities? |

| R1-1-1. It is recommended to measure BMI at least once a year in all adults (I, B).21,60 |

| R1-1-2. Considering the risk of obesity-related comorbidities, the criterion for adult obesity in Korea is a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher (IIa, B).15,61-69 |

| Q1-2. Does dividing obesity into grades help evaluate the risk of obesity-related diseases in adults? |

| R1-2. Obesity is divided into class 1 obesity (BMI 25.0−29.9 kg/m2), class 2 obesity (BMI 30.0−34.9 kg/m2), and class 3 obesity (severe obesity, BMI 35.0 kg/m2 or higher) in Korea, considering the risk of obesity-related comorbidities (IIa, B).38,63 |

| Q1-3. Does measuring WC in addition to BMI help evaluate the risk of obesity-related comorbidities in adults? |

| R1-3. The criteria for determining abdominal obesity by measuring WC are 90 cm or more for men and 85 cm or more for women in Korea (IIa, B).70 |

| 2. Pre-treatment evaluation of obesity |

| Q2-1. Is it necessary to confirm the cause of obesity in adults before treatment? |

| R2-1. Before starting treatment, consider conducting a medical interview and screening tests for genetic diseases, endocrinologic diseases, and medications that may cause obesity (IIa, B).16,17 |

| Q2-2. Is it necessary to confirm the presence of obesity-related comorbidities before treating adult patients with obesity? |

| R2-2. Because obesity increases the risk of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, gout, arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and cancer and increases mortality rate, it is recommended to conduct a medical interview and screening test for these diseases (I, A).18,38,39 |

| Q2-3. What should the weight loss goal for adults with obesity be before treatment? |

| R2-3. It is recommended to set a primary goal of losing 5%−10% of initial body weight within 6 months (I, A).18-20 |

| 3. Diet therapy |

| Q3-1. How much should energy intake be restricted for weight loss in adults with obesity or overweight? |

| R3-1-1. It is recommended to individualize the amount of energy restriction for weight loss in adults with obesity or overweight based on personal characteristics and medical conditions (I, A).38,39 |

| R3-1-2. Very low energy diets should only be performed under supervision of trained professionals under limited circumstances and should be implemented along with intensive lifestyle interventions (I, A).40,71,72 |

| Q3-2. Do differences in macronutrient content in nutritional approaches affect the efficacy of weight loss and improvement of metabolic markers in adults with obesity? |

| R3-2-1. While diverse types of diets (low energy, low carbohydrate, low-fat, high protein, etc.) can be chosen, it is recommended to use a diet that is nutritionally appropriate and achieves an energy deficit, emphasizing healthy eating habits (I, A).38-40 |

| R3-2-2. It is recommended to individualize the composition of macronutrients (carbohydrates, fats, proteins) based on personal characteristics and medical conditions (I, A).38-40 |

| 4. Exercise therapy |

| Q4-1. How should the decision of exercise participation be made before exercise therapy in adults with obesity? |

| R4-1. If there are symptoms of cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal diseases or if there are no symptoms but there is a history of cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal diseases and regular exercise is not performed, exercise should be started after consulting a doctor. In other cases, low to moderate intensity exercise without prior medical permission is appropriate (I, A).73,74 |

| Q4-2. What is the amount and method of exercise that can help lose weight in adults with obesity? |

| R4-2. For weight loss, it is recommended to perform aerobic exercise for at least 150 minutes per week, 3−5 times a week and resistance exercise using large muscle groups, 2−3 times a week (I, A).75-81 |

| Q4-3. What is the difference in weight loss effect between the combination of aerobic and resistance exercise versus aerobic exercise alone in adults with obesity? |

| R4-3. Exercise that combines aerobic exercise and resistance exercise is more effective for weight loss than either aerobic exercise alone or resistance exercise alone. Therefore, it is recommended to perform a combination of both aerobic and resistance exercise for weight loss (I, A).80,82 |

| Q4-4. What is the difference in weight loss effect between exercise alone and exercise performed in combination with diet therapy in adults with obesity? |

| R4-4. For effective weight loss, it is recommended to combine exercise with diet therapy (I, A).76,83 |

| 5. Behavioral therapy |

| Q5-1. Are comprehensive lifestyle interventions that incorporate behavioral therapy techniques more effective for weight loss and its maintenance in adults with obesity than typical treatments (e.g., providing advice and educational materials)? |

| R5-1-1. For weight loss, comprehensive lifestyle improvement such as reducing energy intake and increasing physical activity based on behavioral therapy is recommended (I, A).84,85 |

| R5-1-2. For effective weight loss, it is recommended that a trained therapist conduct face-to-face behavioral therapy for at least 6 months (I, A).71,86,87 |

| R5-1-3. For effective maintenance of weight loss, it is recommended that a trained therapist conduct behavioral therapy for at least 1 year (I, A).86,88-90 |

| R5-1-4. If a 2.5% weight loss is not achieved within 1 month of behavioral therapy, consider reinforcing the lifestyle interventions based on behavioral therapy (IIa, B).21,91,92 |

| Q5-2. What measures are necessary for weight loss and its maintenance in adults with obesity who drink alcohol? |

| R5-2. It is recommended to evaluate alcohol consumption during behavioral therapy for weight loss and its maintenance (I, A).93-95 |

| Q5-3. What treatment is needed to reduce weight gain when trying to quit smoking during obesity treatment? |

| R5-3. When attempting to quit smoking during obesity treatment, consider using smoking cessation medications in conjunction with behavioral therapy to prevent weight gain (IIa, B).96-98 |

| 6. Pharmacotherapy |

| Q6-1. Is it appropriate to only use medication to treat obesity in adults with obesity? |

| R6-1. The basic treatment for obesity is diet therapy, exercise therapy, and behavioral therapy, and it is recommended to use medication as an additional treatment method only in combination with these (I, A).99-112 |

| Q6-2. What are the indications for obesity pharmacotherapy in adults with obesity? |

| R6-2. In Korean adults with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or more who have failed to lose weight with non-medicinal treatment, pharmacotherapy should be considered (IIa, B).21,40,61,113 |

| Q6-3. What medications should be used for weight loss in adults with obesity? |

| R6-3. For long-term weight management, it is recommended to use medications that have been approved based on large-scale clinical trials (I, A).99,114 |

| Q6-4. Should anti-obesity medication be maintained in case of an insufficient response? |

| R6-4. If at least 5% weight loss is not achieved within 3 months of maintenance dosage of anti-obesity medication, it is recommended to change or stop the medication (I, A).115-120 |

| 7. Bariatric surgery |

| Q7-1. Which group of patients will benefit the most from weight loss or show improvement in obesity-related comorbidities if they undergo bariatric/metabolic surgery compared to non-surgical treatment? |

| R7-1-1. Bariatric/metabolic surgery should be considered in Korean adults with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more, or a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more with obesity-related comorbidities, who have failed to lose weight with non-surgical treatment (IIa, B).40,48 |

| R7-1-2. Bariatric/metabolic surgery should be considered in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus with a BMI of 27.5 kg/m2 or more and a blood sugar level that is not properly controlled with non-surgical treatment (IIa, B).40,48 |

| Q7-2. What should be evaluated before performing bariatric/metabolic surgery in patients who need it? |

| R7-2-1. It is recommended to collect a medical and psychosocial history, conduct a physical examination, and run diagnostic tests to evaluate the safety of the potential bariatric/metabolic surgery (I, A).121,122 |

| R7-2-2. Appropriate evaluation of nutritional status should be considered before bariatric/metabolic surgery (IIa, B).123 |

| R7-2-3. It is recommended to quit smoking at least 6 weeks prior to bariatric/metabolic surgery (I, B).124 |

| Q7-3. What type of bariatric/metabolic surgery should be performed in patients who need it? |

| R7-3. It is recommended to choose from among standard procedures that have been proven to be effective and safe, such as sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass,adjustable gastric banding, and biliopancreatic diversion/duodenal switch, taking into account the individual’s status (I, A).40 |

| Q7-4. Does continuous follow-up management after bariatric/metabolic surgery affect the outcome? If so, what is the appropriate follow-up method for management and evaluation? |

| R7-4-1. It is recommended to conduct multidisciplinary follow-up management for all patients who have undergone bariatric/metabolic surgery (I, B).47-50 |

| R7-4-2. It is recommended to supplement micronutrients and conduct regular follow-up examinations according to the surgical procedure after bariatric/metabolic surgery (I, B).76,81,84 |

| 8. Obesity in the elderly |

| Q8-1. What should be considered when evaluating obesity in the elderly? |

| R8-1. It is recommended to evaluate WC in conjunction with BMI when diagnosing obesity in the elderly (I, A).8-10 |

| Q8-2. When does weight loss help in the elderly? |

| R8-2. Weight loss should be considered when the benefits outweigh the risks for the elderly (IIa, B).21-32 |

| Q8-3. What should be considered for effective and safe obesity treatment in the elderly? |

| R8-3-1. In managing obesity in the elderly, it may be necessary to evaluate osteoporosis and sarcopenia (IIb, B).21,35-37 |

| R8-3-2. For treatment of obesity in the elderly, it is recommended to prioritize a low energy diet rich in protein and to increase physical activity (I, A).125-128 |

| R8-3-3. When treating obesity in the elderly, pharmacotherapy and surgical treatments may be considered with caution, taking into account the presence of accompanying diseases and medications to ensure patient safety (IIb, B).21,40,56-59,129 |

| 9. Obesity in children and adolescents |

| Q9-1. How is obesity diagnosed in children and adolescents? |

| R9-1-1. It is recommended to prevent and treat childhood and adolescent obesity, because obesity in this age group easily progresses to adult obesity and is associated with a high risk of obesity-related comorbidities (I, A).130-132 |

| R9-1-2. When diagnosing obesity for children and adolescents older than 2 years, it is recommended to use the BMI percentile for age and sex based on the 2017 Korean National Growth Chart for Children and Adolescents. A BMI in the 85th percentile or higher should be considered to indicate pre-obesity (overweight), while a BMI in the 95th percentile or higher should be considered to indicate obesity (I, A).12-14,130 |

| R9-1-3. Individualized medical risk assessment should be considered in children and adolescents with pre-obesity or obesity (IIa, B).14,130,132 |

| Q9-2. What are the treatment goals and principles for obesity in children and adolescents? |

| R9-2. Treatment of obesity in children and adolescents is recommended to maintain appropriate weight while supplying the energy and nutrients necessary for normal growth and to habituate a healthy lifestyle (I, A).14,52,130,132-135 |

| Q9-3. What are safe and effective treatment strategies for obesity in children and adolescents? |

| R9-3-1. Comprehensive lifestyle modifications including diet, exercise, and behavioral therapy are recommended for treatment of obesity in children and adolescents (I, A).14,52,130 |

| R9-3-2. In cases where weight gain and obesity-related comorbidities are sustained even with intensive diet, exercise, and behavioral therapy, obesity pharmacotherapy by an experienced specialist should be considered (IIa, B).130,133,134,136 |

| R9-3-3. In cases where weight gain and obesity-related comorbidities are sustained even with intensive multidisciplinary treatment and pharmacotherapy for obesity, surgical therapy may be considered in limited cases, only after completion of growth and puberty (IIb, C).52-55 |

| 10. Obesity in women |

| Q10-1. Does weight loss help in reducing pregnancy complications in women with obesity who are preparing for pregnancy? |

| R10-1. Women who are considering pregnancy are recommended to maintain a normal weight to reduce obstetric and perinatal risks (I, A).137-145 |

| Q10-2. What are the appropriate lifestyle habits for weight management during pregnancy and after delivery in women with obesity? |

| R10-2-1. In pregnant women with obesity, a balanced diet and regular physical activity should be considered for appropriate rather than excessive weight gain during pregnancy (IIa, B).146-150 |

| R10-2-2. Active lifestyle interventions, such as modification of diet and an increase in physical activity, are recommended for weight management after delivery in women with obesity (I, A).151 |

| Q10-3. Does menopause increase the risk of obesity and its comorbidities? |

| R10-3. Because menopause can lead to abdominal obesity, which increases the risk of obesity-related comorbidities, appropriate weight management is recommended for menopausal women with obesity (I, A).152-158 |

| Q10-4. Should hormone therapy be used to aid weight loss or to prevent weight gain in menopausal women? |

| R10-4. Hormone therapy is not recommended for the purpose of weight loss in menopausal women (III, A).159 |

| 11. Obesity in patients with mental illness |

| Q11-1. Is it necessary to conduct screening tests for obesity and metabolic diseases in patients with severe mental illness for proper management? |

| R11-1. It is recommended to conduct screening tests for obesity and metabolic diseases in patients with severe mental illness who are taking medications related to weight gain for prevention and management of metabolic diseases (I, B).160 |

| Q11-2. For patients with obesity and severe mental illness, is it effective and mentally safe to implement comprehensive lifestyle interventions, obesity pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery? |

| R11-2. For weight loss in patients with obesity and severe mental illness, comprehensive lifestyle interventions are recommended (I, A).161-166 |

| Q11-3. Is distinguishing whether a patient with obesity also has binge eating disorder useful in predicting the effectiveness of obesity treatment? |

| R11-3. Because patients with obesity in conjunction with binge eating disorder may experience less weight loss in response to typical obesity treatments, the presence of binge eating disorder should be considered for evaluation when treating obesity (IIa, C).167,168 |

| Q11-4. What kind of obesity treatment is effective at inducing weight loss and improving symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea? |

| R11-4. Comprehensive lifestyle interventions for weight loss are recommended for patients with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea (I, A).169-174 |

| 12. Weight maintenance after weight loss |

| Q12-1. Are there different long-term outcomes for obesity-related comorbidities in adults with obesity who have successfully maintained weight loss compared to those who have not? |

| R12-1. It is recommended to maintain weight loss for more than 1 year to prevent and manage obesity-related comorbidities (I, A).88,175-184 |

| Q12-2. What treatment is effective for long-term weight management and outcomes in adults with obesity? |

| R12-2-1. It is recommended to use a combination of diet, exercise, and cognitive behavioral therapy for weight maintenance after weight loss (I, A).185-193 |

| R12-2-2. The use of anti-obesity medications that are approved for long-term use may also be considered (IIb, B).88,107,194 |

| Q12-3. Is additional obesity pharmacotherapy helpful for long-term weight management in patients with morbid obesity who have regained weight after bariatric/metabolic surgery? |

| R12-3. In patients who have regained weight after bariatric/metabolic surgery, the use of anti-obesity medications in conjunction with lifestyle modifications may be considered (IIb, B).195-198 |

| 13. Metabolic syndrome |

| Q13-1. What are the diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome in Korean adults? |

| R13-1. In Korea, adults are diagnosed with metabolic syndrome if they meet three or more of the following criteria (-, A).70,199,200 |

| (1) Abdominal obesity (WC ≥ 90 cm in men and ≥ 85 cm in women) |

| (2) Elevated blood pressure (≥ 130/85 mmHg or use of hypertension medications) |

| (3) Elevated fasting blood sugar (≥ 100 mg/dL or use of diabetes medications) |

| (4) Elevated triglycerides (≥ 150 mg/dL or use of lipid-lowering drugs) |

| (5) Low HDL cholesterol (< 40 mg/dL in men and < 50 mg/dL in women or use of lipid-lowering drugs) |

| Q13-2. What are effective interventions for treating and managing metabolic syndrome in adults? |

| R13-2. To treat and manage metabolic syndrome, lifestyle modifications and, if necessary, drug interventions for individual components are recommended (I, A).201-211 |

| 14. Obesity treatment using ICT-based interventions |

| Q14-1. Can information and communication technology-based methods be used to modify lifestyle to manage obesity and metabolic syndrome? |

| R14-1. ICT-based interventions should be considered for managing obesity and metabolic syndrome (IIa, B).212,213 |

| Q14-2. Are ICT-based interventions effective at inducing weight loss and maintenance compared to conventional treatment in adults with obesity? |

| R14-2. ICT-based interventions may be considered as part of a comprehensive strategy for weight loss (IIb, B).214-216 |

Literature review

A medical librarian developed literature search strategies and formulas specifically tailored to each database search engine. Utilizing these strategies, the librarian systematically searched through literature- search software for selected topics and established key questions. These searches were executed in PICO format. The publication date range of the literature searched was between January 2010 and May 2021. Report types searched were systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized clinical trials, cohort studies, and guidelines. Narrative reviews were also included for topics lacking randomized clinical trials. Electronic databases of Pubmed (Medline), Embase, Cochrane Library, KoreaMed, RISS (KERIS), ScienceOn, Guidelines International Network (GIN), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), and Google were searched.

Level of evidence and recommendations

The level of evidence of the literature (or guidelines) used for developing the recommendations was classified into four categories (A, B, C, and D in Supplementary Table 1). The Committee of Clinical Practice Guidelines used the modified Grading of Recommendation Assessments, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) method to determine the strength of the recommendations considering the level of evidence, benefits and harms, feasibility, acceptability, and level of applicability in primary care practice. There were four grades of recommendations (I, IIa, IIb, and III in Supplementary Table 1)7. Even if the level of evidence was low, recommendations that were considered to have clear benefits or high applicability in clinical practice were upgraded by agreement of the Committee of Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Employment of multi-level reviews and cross-checks

After initial development of the recommendations, a small group discussion method was used to review these recommendations. Review and cross-checking by the steering board and writing members resulted in revision of the initial recommendations and explanations. Then, at KSSO congresses, two public hearings on the updated management guidelines were held. The revised version after the public hearings was reviewed by executive members of KSSO who were not members of the guidelines committee. Finally, the steering board supervised and confirmed the final version. Endorsement was requested and received from relevant scientific societies and associations.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR OBESITY, ABDOMINAL OBESITY, AND METABOLIC SYNDROME

Diagnostic criteria for obesity, abdominal obesity, and metabolic syndrome remain the same as in the previous version (Table 2). Diagnosis of obesity based on body mass index (BMI) applies regardless of age in adults. However, in the elderly, the same BMI may indicate a higher body fat percentage due to changes in body composition caused by decreased muscle and bone mass, as well as a decrease in height. Therefore, we recommended evaluation of waist circumference (WC) in conjunction with BMI when diagnosing obesity in the elderly (I, A).8-10 For children and adolescents older than 2 years, use of the BMI percentile for age and sex based on the 2017 Korean National Growth Chart for Children and Adolescents is recommended; a BMI in the 85th percentile or higher is considered to indicate pre-obesity (overweight), while that in the 95th percentile or higher is considered to indicate obesity (I, A).11-14 Obesity in adults is divided into class 1, class 2, and class 3 obesity (extreme obesity) (BMI 35.0 kg/m2 or higher) in Korea (IIa, B).12,15 Criteria used to diagnose obesity and abdominal obesity have been established, taking into account the risk of obesity-related comorbidities.

Table 2.

Diagnostic criteria for obesity, abdominal obesity, and metabolic syndrome and risk of comorbidity according to BMI and WC in Koreans

| Classification* | BMI (kg/m2) | Risk of comorbidity according to WC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 90 cm (men), < 85 cm (women) | ≥ 90 cm (men), ≥ 85 cm (women) | ||

| Adults ( ≥ 18 years) | |||

| Underweight | < 18.5 | Low | Average |

| Normal | 18.5–22.9 | Average | Increased |

| Pre-obesity | 23–24.9 | Increased | High |

| Class 1 obesity | 25–29.9 | High | Severe |

| Class 2 obesity | 30–34.9 | Severe | Very severe |

| Class 3 obesity | ≥ 35 | Very severe | Very severe |

| Metabolic syndrome in adults | |||

| Adults are diagnosed with metabolic syndrome if they meet three or more of the following criteria. | |||

| (1) Abdominal obesity (WC ≥ 90 cm in men and ≥ 85 cm in women) | |||

| (2) Elevated blood pressure ( ≥ 130/85 mmHg or use of hypertension medications) | |||

| (3) Elevated fasting blood sugar ( ≥ 100 mg/dL or use of diabetes medications) | |||

| (4) Elevated triglycerides ( ≥ 150 mg/dL or use of lipid-lowering drugs) | |||

| (5) Low HDL-cholesterol ( < 40 mg/dL in men and < 50 mg/dL in women or use of lipid-lowering drugs) | |||

| Children and adolescents (2−18 years old) | BMI percentile for sex and age based on 2017 Korean National Growth Chart for Children and Adolescents | ||

| Pre-obesity | 85th–94.9th | ||

| Obesity | ≥ 95th |

Although the cut-off values for each criterion were the same as those used in the previous KSSO guidelines, levels of evidence and grades of recommendations were modified through evaluation.

EVALUATING OBESITY STATUS AND RELATED COMORBIDITIES AND SETTING TREATMENT GOALS PRIOR TO TREATMENT INITIATION

More than 90% of obesity cases are due to an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure, known as primary obesity. However, in some cases, secondary causes such as genetic and congenital disorders, medications, neurological and endocrine diseases, or psychiatric illnesses may be present (Table 3). Accurately identifying and addressing these underlying causes can lead to more effective weight loss. Therefore, prior to initiating obesity treatment, a medical interview and screening tests should be considered to identify secondary obesity and its causes (IIa, B).16,17

Table 3.

Causes of secondary obesity

| Classification | Causes |

|---|---|

| Monogenic obesity | Leptin deficiency |

| Leptin receptor deficiency | |

| Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) deficiency | |

| Melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) deficiency | |

| Other | |

| Congenital syndromic obesity | Prader-Willi syndrome |

| Laurence-Moon-Biedl syndrome | |

| Alström syndrome | |

| Cohen syndrome | |

| Carpenter syndrome | |

| Other | |

| Drugs | Antipsychotics: thioridazine, olanzepine, clozapine, quetiapine, risperidone |

| Tricyclic antidepressants: imipramine, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, doxepin | |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: paroxetine | |

| Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants: mirtazapine | |

| Mood stabilizers: lithium | |

| Anti-convulsants: valproate, carbamazepine, gabapentin, pregabalin | |

| Anti-diabetics: insulin, sulfonylurea, glinide, thiazolidinedione | |

| Serotonin receptor antagonists: pizotifen | |

| H1 antihistamines: cyproheptadine | |

| β-Blockers: propranolol, metoprolol, atenolol, nadolol | |

| α-Blockers: terazosin, prazosin, clonidine | |

| Steroids: oral contraceptives, glucocorticoids | |

| Neuroendocrine diseases | Hypothalamic obesity: trauma, tumor, infective disorder, neurosurgery, elevated intracranial pressure |

| Cushing's syndrome | |

| Insulinoma | |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | |

| Growth hormone deficiency in adults | |

| Hypothyroidism | |

| Psychiatric disorders | Affective disorder: major depression, bipolar disorder, seasonal affective disorder |

| Anxiety disorder: panic disorder, agoraphobia | |

| Binge eating disorder | |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | |

| Alcohol dependency |

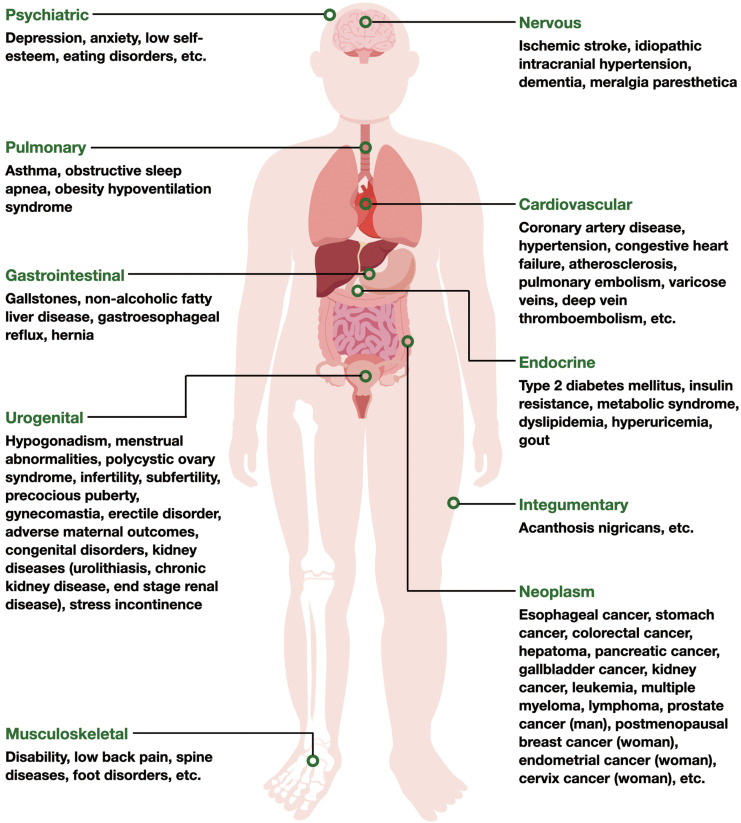

People with obesity are at an increased risk for comorbidities stemming from metabolic abnormalities, such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, gallbladder disease, gout, and some types of cancer. They also are at higher risk of developing weight-related conditions such as arthritis, low back pain, and obstructive sleep apnea compared to normal weight individuals. These obesity-related comorbidities are illustrated according to body system in Fig. 1. Refer to Table 4 for a list of tests used to evaluate obesity and its associated comorbidities.

Figure 1.

Comorbidities of obesity by body system.

Table 4.

Evaluation of obesity and its related comorbidities

| Obesity | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. BMI should be measured regularly at least once a year in all adults. People with a BMI between 23 and 24.9 kg/m2 are classified as with pre-obesity, while those with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or above are classified as with obesity. | ||

| 2. WC should be measured to assess abdominal obesity. Individuals with abdominal obesity are considered at elevated risk for obesity-related comorbidities. | ||

| 3. Evaluate comorbidities in people with pre-obesity or obesity | ||

| History taking | Obtain a comprehensive history, including past medical history, family history, current medications, smoking and alcohol use, social history, previous weight loss attempts, history of weight change, reason for weight gain, dietary habits, eating disorders, physical activity level, exercise habits, mental health status including depression and stress, desired weight, and motivation for weight loss | |

| Physical examination | Measure height, weight, WC, vital signs, body composition (using BIA or DXA if necessary), and visceral fat amount (using CT or MRI if necessary) and conduct a systemic physical examination to assess comorbidities | |

| Laboratory evaluation | Measure fasting blood glucose, serum lipid profile, uric acid, thyroid-stimulating hormone, liver function tests, complete blood count, renal function tests, and inflammatory markers and conduct tests for evaluation of secondary obesity (if necessary) | |

| Obesity-related comorbidities | ||

| System | Comorbidities | Suggested tests |

| Cardio-cerebrovascular | Coronary artery disease, hypertension, ischemic stroke, congestive heart failure, atherosclerosis, pulmonary embolism, varicose veins, deep vein thromboembolism, etc. | Blood pressure, pulse rate, electrocardiography. Conduct a thorough examination for suspected diseases if necessary. |

| Gastrointestinal | Gallstone, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, gastroesophageal reflux, hernia | Liver function tests. Conduct abdominal ultrasound and/or upper endoscopy if necessary. |

| Pulmonary | Asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity hypoventilation syndrome | Chest X-ray, pulmonary function tests, measurement of neck circumference, polysomnography if necessary. |

| Endocrine | Type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, gout | Fasting blood glucose, serum lipid profile, uric acid. Glycated hemoglobin and/or fasting insulin if necessary. |

| Tumor | Esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, colorectal cancer, hepatoma, pancreatic cancer, gallbladder cancer, kidney cancer, leukemia, multiple myeloma, lymphoma, prostate cancer (man), postmenopausal breast cancer (woman), endometrial cancer (woman), cervix cancer (woman) | Conduct a thorough examination for suspected diseases if necessary. |

| Urogenital | Hypogonadism, menstrual abnormalities, polycystic ovary syndrome, infertility, subfertility, precocious puberty, gynecomastia, erectile disorder, adverse maternal outcomes (gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, eclampsia, miscarriage, dystocia, elevated risk of cesarean sections), congenital disorders (neural tube defects, cleft lip and cleft palate, hydrocephalus, congenital heart diseases), stress incontinence | Conduct a thorough examination for suspected diseases if necessary. |

| Musculoskeletal | Disability, low back pain, osteoarthritis, spine diseases, foot disorders | Conduct a thorough examination for suspected diseases if necessary. |

| Nervous | Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, dementia, meralgia paresthetica | Conduct a thorough examination for suspected diseases if necessary. |

| Psychiatric | Depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, eating disorder, decreased work performance, low quality of life, body dissatisfaction | Conduct a thorough examination for suspected diseases if necessary. |

| Other | Acanthosis nigricans, skin infections, periodontal disease, increased risk of anesthesia complications, lymphedema | Conduct a thorough examination for suspected diseases if necessary. |

The goal of obesity treatment is not exclusively centered on achieving weight loss, but rather a reduction in the risk of obesity-related diseases and an increase in overall health. A weight loss of 5% to 10%, along with improvements in lifestyle, have been shown to have clinically significant benefits. We recommend losing 5% to 10% of initial body weight within 6 months (I, A).18-20

Obesity in the elderly increases the risk of various diseases and medical costs, but there is insufficient evidence to show that weight loss can effectively prevent or treat obesity-related complications. Additionally, elderly individuals have a high incidence of osteopenia and osteoporosis, which increases the risk of fractures. Weight loss in this population may also be associated with decreased bone density and muscle mass. When treating obesity in older adults, evaluation of osteoporosis should be considered in high-risk groups, and weight loss should be considered when the benefits outweigh the risks (IIa, B).21-34 Compared to the previous version of these guidelines, the current version recommends evaluation of osteoporosis and sarcopenia when treating obesity in the elderly (IIb, B).21,35-37

LIFESTYLE-RELATED THERAPY

Diet, exercise, and behavioral therapy that induce lifestyle improvements are the mainstays of obesity treatment. General principles in this field remain unchanged from the previous edition of the guidelines. See Table 1 for detailed recommendations.

This edition of the guidelines recommends individualizing the amount of energy restriction and the composition of macronutrients (carbohydrates, fats, proteins) for weight loss. Adequate protein intake is important to prevent sarcopenic obesity in the treatment of elderly obesity. A very low energy diet (VLED) that severely restricts calorie intake to 800 kcal or less per day can result in significant short-term weight loss; however, this rapid weight loss method can cause various medical problems. Therefore, VLED should only be performed under the supervision of trained professionals under limited circumstances. In the 8th edition guidelines, we recommend a nutritionally appropriate diet and reduction of energy intake as was recommended in the previous edition of the guidelines and additionally emphasize “healthy eating habits” (I, A).38-40 Refer to Table 5 for the diverse types of diets that can be implemented.

Table 5.

Summary of the characteristics of diverse diet therapies

| Diet therapy | Characteristic |

|---|---|

| Low energy diet | Energy intake reduction by 500-1,000 kcal per day |

| This enables the consumption of a nutritionally appropriate meal. | |

| 0.5−1.0 kg/week of weight loss is expected. | |

| A maximum effect on weight loss may be attained within 6 months, with a gradual decrease thereafter. | |

| Very low energy diet | Energy restriction to 800 kcal/day or less |

| Rapid weight loss is possible in a short period of time, but there is no significant difference in the long-term compared to a low energy diet. | |

| Medical supervision is necessary to prevent serious medical outcomes. | |

| Should be accompanied by interventions for long-term lifestyle improvements. | |

| Very low carbohydrate diet | Limit carbohydrate consumption to less than 130 g/day or 30% of total energy (restrict to less than 50 g or 10% of total energy at start and increase gradually) |

| Initial weight loss effect is greater than with a low energy diet, but the long-term effect is either similar or minimally better. | |

| This may improve serum triglyceride level but also increase the risk of cardiovascular disease due to elevation of LDL cholesterol. | |

| Low carbohydrate diet | Limit carbohydrate consumption to 40%−45% of total energy typically |

| Initial weight loss effect is greater than the low energy diet, but the long-term effect is either similar or minimally better. | |

| This may improve serum triglyceride level but also increase the risk of cardiovascular disease due to elevation of LDL cholesterol. | |

| High protein diet | Usual protein intake of 25%−30% of total energy |

| Helpful to prevent excessive carbohydrate intake, loss of lean mass, and maintain an appropriate protein nutrition status | |

| Effective for weight loss/maintenance compared to a low energy diet but not to a large extent | |

| Intermittent energy restriction | Alternative dietary approach to the conventional continuous energy-restricted diet |

| - Intermittent fasting: an eating pattern that alternates between periods of fasting and non-fasting days | |

| - Time-restricted diet: a type of eating pattern that allows eating within a particular window of time each day | |

| There is no significant or minimal difference in the degree of weight loss compared to continuous energy restriction methods. | |

| There is limited evidence on the long-term effects of this diet type on obesity. |

With regard to exercise therapy, individuals with symptoms of cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal diseases or those with a history of these diseases but who do not regularly exercise should consult a doctor before starting. In other cases, it is safe to start a low to moderate intensity exercise regimen without obtaining medical clearance. This edition of the guidelines recommends aerobic exercise for at least 150 minutes per week, 3 to 5 times a week, and resistance exercise using large muscle groups 2 to 3 times per week for weight loss. Furthermore, increasing aerobic exercise to 250 to 300 minutes per week is suggested for more meaningful weight loss. Compared to exercise therapy alone, it has been shown that body weight, BMI, and WC are more improved when exercise therapy is combined with dietary therapy.

Comprehensive lifestyle improvement such as reducing energy intake and increasing physical activity based on behavioral therapy are recommended for weight loss in this edition of the guidelines, similar to the previous edition. Additionally, third-wave cognitive behavioral therapy, such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy, is newly introduced in this edition of the guidelines.41-45 Compared with the previous version of the guidelines, this edition recommends intensifying lifestyle interventions based on behavioral therapy if weight loss of 2.5% is not achieved within 1 month of starting therapy and highlights the roles of alcohol consumption and smoking during behavioral therapy for weight loss and maintenance.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Despite the development of many new peptide anti-obesity medications, with some of these currently under consideration for approval by the Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, there have been no new approvals of anti-obesity medications for adults with obesity since the 7th edition of the guidelines (up to February 2023). However, liraglutide was newly approved during that period for patients with obesity aged 12 years or older. Therefore, currently available anti-obesity medications for children and adolescents in Korea are phentermine (for those aged 16 or older) for short-term treatment and orlistat (for those aged 12 or older) and liraglutide (for those aged 12 or older) for long-term treatment (Table 6).46 In adults with obesity, orlistat, naltrexone/bupropion extended release (ER), liraglutide, and phentermine/topiramate ER are available for long-term weight loss, while phentermine, diethylpropion, phendimetrazine, and mazindol are available for short-term treatment in Korea.

Table 6.

Anti-obesity medications for the pediatric population

| Drug name | Mechanism of action | Indication | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orlistat | Pancreatic and gastric lipase inhibitor | Obesity ≥ 12 years old | Flatulence, oily spotty stools, diarrhea, vitamin/mineral deficiencies |

| Phentermine | Sympathomimetic amine | Obesity > 16 years old Short-term use | Increases heart rate and blood pressure and causes dry mouth, insomnia, constipation, anxiety, irritability |

| Liraglutide 3.0 mg | GLP-1 receptor agonist | Adolescents (12−17-year-old) with a BMI corresponding to ≥ 30 kg/m2 for adults and body weight > 60 kg | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, potential hypoglycemia; contraindicated with history or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma, MEN type 2, ESRD |

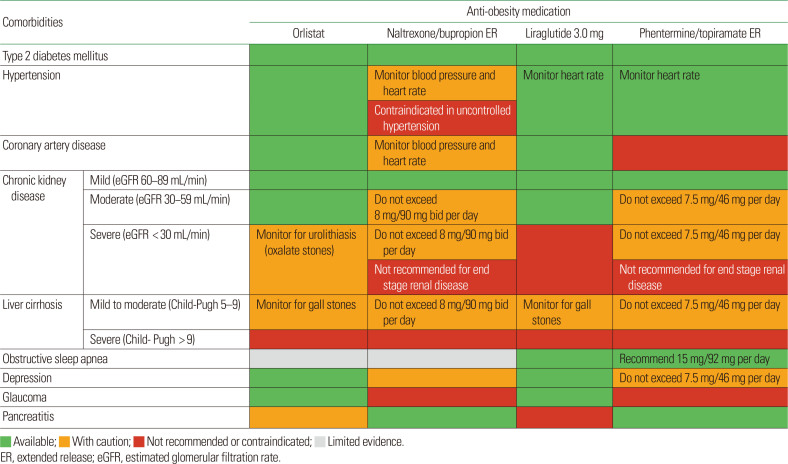

Obesity pharmacotherapy is recommended as an additional treatment method for Korean adults with a BMI of 25 kg/m² or higher after failure of non-pharmacological methods. Medication selection should consider accompanying diseases (Table 7). Given the diverse responses of individuals to these medications and the potential for adverse events, it is recommended to discontinue the medication in the event of a lack of response. In adults, if greater than 5% weight loss is not achieved within 3 months of maintenance dosage, the medication should be discontinued or changed. In children and adolescents, if there is less than a 4% decrease in BMI or BMI z-score despite 12 weeks of medication, the medication should be considered ineffective and changed or discontinued.

Table 7.

Selection of anti-obesity medication according to comorbidities

BARIATRIC AND METABOLIC SURGERY

The indications for bariatric/metabolic surgery for obesity are the same as in the previous version of the guidelines and are shown in Table 1. A standard procedure that has been proven to be effective and safe, such as sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding, or biliopancreatic diversion/duodenal switch, is recommended based on patient condition (I, A).40,47 After bariatric/metabolic surgery, multidisciplinary follow-up management should be scheduled for all patients (I, B).47-50 In addition, micronutrient supplementation should be initiated, and regular follow- up examinations should be conducted according to the surgical procedure (I, B).47,48,51 For children and adolescents with obesity, in cases where weight gain and obesity-related comorbidities remain despite intensive multidisciplinary treatment and pharmacotherapy for obesity, surgical therapy may be considered in limited cases, only after completion of growth and puberty (IIb, C).52-55 In pediatric and adolescent cases, surgery may be considered if the BMI is 35 kg/m2 or higher, the BMI is higher than 120% of the 95th percentile, and there are obesity-related comorbidities or if BMI is 40 kg/m2 or higher or exceeds 140% of the 95th percentile. Bariatric surgery in the elderly is considered safe and effective; however, indications for bariatric surgery in obese elderly people in Asia, including Korea, have not been established. Age does not seem to increase the risk of complications after bariatric surgery. Therefore, if the risk of complications after surgery is not greater than the impact of obesity-related disabilities, surgical treatment for elderly people with obesity may be considered, taking into account accompanying diseases, medications, and safety (IIb, B).21,40,56-59

NEW TOPICS INCLUDED IN THIS EDITION OF THE GUIDELINES

To stay current with the constantly evolving field of obesity, new main topics such as obesity in women, obesity in patients with mental illness, weight maintenance after weight loss, and the use of ICT-based interventions for obesity treatment are included in the 8th edition guidelines.

Women should maintain a normal weight before pregnancy due to the higher obstetric and perinatal risks associated with obesity. However, there is limited evidence to support the obstetric and perinatal benefits of non-pharmacological and pharmacological weight loss methods in women with obesity. Although a metaanalysis has shown positive impacts of bariatric surgery on spontaneous pregnancy in infertile women, these findings should be approached with caution due to the quality of the included data.

The current guidelines also address pregnancy-related weight gain and the relationship between obesity and menopause. During pregnancy, women with obesity should maintain a balanced diet and engage in regular physical activity to achieve appropriate weight gain. After delivery, active lifestyle interventions are recommended for weight management. Appropriate weight management is also recommended for women who are obese and in the menopausal period due to the increased risk of obesity-related comorbidities. Hormone therapy should not be used solely for the purpose of weight loss in menopausal women.

Severe mental illness has been linked to obesity and its comorbidities. Additionally, depression may also contribute to the development of obesity and an unhealthy metabolic state. Another important factor to consider in the clinical context is that many medications used to treat severe mental illness can cause weight gain. In light of this, the guidelines include key questions about screening tests for obesity and metabolic diseases and comprehensive lifestyle interventions for weight loss in patients with severe mental illness who are taking medications; recommendations are shown in Table 1.

Long-term maintenance after weight loss is more beneficial for overall health and well-being than is short-term weight loss. One of the most significant benefits of weight maintenance is prevention of diabetes. Additionally, it can improve the apnea-hypopnea index in individuals with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea, improve cerebral blood flow, and lower blood pressure. Furthermore, weight maintenance has been found to be associated with a lower mortality rate in individuals with obesity. The importance of long-term maintenance of weight loss and maintenance methods are highlighted in Table 1.

Another new area addressed in this edition of the guidelines is the use of ICT-based interventions for obesity. ICT-based interventions can supplement the lack of psychological and behavioral counseling provided by healthcare professionals and can facilitate achievement and maintenance of lifestyle modifications. Based on available evidence, technology-based interventions are recommended for obesity treatment (Table 1).

CONCLUSION

The 8th edition of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity of KSSO was developed after reviewing all relevant scientific evidence and is intended for use by medical professionals, nutritionists, physical educators, and other related professionals in actual practice.

Methodologically, this edition of the guidelines features better links key questions in PICO format to recommendations and key references as answers to each key questions, increasing organization (Table 1). When developing clinical practice guidelines, it is important to involve stakeholders in the process, and our guideline development group included members from all relevant expert groups. However, a limitation of our work is the lack of investigation into the perspectives and preferences of the target population (patients, the general public, etc.) to whom the guidelines will be applied. Additional limitations include insufficient description of barriers and facilitators to executing the guidelines and lack of consideration of potential resources that may be required for application of the guidelines. In the future, clinical practice guidelines should address these methodological limitations.

The 8th edition of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity has incorporated several new topics to keep up with the constantly evolving field of obesity. One of the new topics, ‘obesity in women,’ will be of great benefit to medical professionals treating women during their reproductive years, pregnancy, and postmenopausal stages. Additionally, two important topics, ‘obesity in patients with mental illness’ and ‘weight maintenance after weight loss,’ were added to provide strategies to address the most challenging issues faced by medical professionals treating obesity. The use of ICT is becoming increasingly important in medical fields, and the new topic ‘obesity treatment using ICT-based interventions’ will provide a foundation for further knowledge development in this area.

We are confident that the 8th edition of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity will be a useful tool for all healthcare professionals treating patients with obesity and will play a crucial role in improving the health of the Korean population.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials can be found online at https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes23016.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support was received from Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. However, the financial supporter did not directly or indirectly influence the content or development process of these guidelines.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

In order to confirm the presence or absence of conflicts of interest among all members involved in the development of these guidelines, a survey was conducted on whether they had received more than 10 million Korean won in sponsorship or consulting fees over the past 2 years on topics related to the development of these guidelines, whether they have rights to economic benefits such as stock options from specific institutions or pharmaceutical companies, and whether they hold official/unofficial positions in pharmaceutical companies. The survey results indicated no conflicting or potential conflicts of interest.

Ga Eun Nam has worked as an Associate Editor of the Journal of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome since 2020. However, she was not involved in peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or the decision process for this article. There are no other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article to report.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: KKK, JHH, BTK, EMK, JHP, SYR, JHK, and CBL; acquisition of data: all authors; analysis and interpretation of data: all authors; drafting of the manuscript: KKK, JHK, and JHH; critical revision of the manuscript: KKK and JHK; obtained funding: CBL; administrative, technical, or material support: KKK, JHK, and JHH; and study supervision: JHK.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yang YS, Han BD, Han K, Jung JH, Son JW Taskforce Team of the Obesity Fact Sheet of the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity, author. Obesity fact sheet in Korea, 2021: trends in obesity prevalence and obesity-related comorbidity incidence stratified by age from 2009 to 2019. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2022;31:169–77. doi: 10.7570/jomes22024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schienkiewitz A, Mensink GB, Scheidt-Nave C. Comorbidity of overweight and obesity in a nationally representative sample of German adults aged 18-79 years. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:658. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haase CL, Lopes S, Olsen AH, Satylganova A, Schnecke V, McEwan P. Weight loss and risk reduction of obesity-related outcomes in 0.5 million people: evidence from a UK primary care database. Int J Obes (Lond) 2021;45:1249–58. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00788-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thavorncharoensap M. ADBI Working Paper 654: Effectiveness of obesity prevention and control [Internet] SSRN; 2017. [cited 2023 Mar 21]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3016129 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korean Ministry of Health & Welfare, author; Korean Academy of Medical Sciences, author. Adaptation process for developing Korean clinical practice guidelines. KAMS; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Brozek J, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, Mustafa RA, Manja V, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;81:101–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graf CE, Herrmann FR, Spoerri A, Makhlouf AM, Sørensen TI, Ho S, et al. Impact of body composition changes on risk of all-cause mortality in older adults. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:1499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamboni M, Mazzali G, Zoico E, Harris TB, Meigs JB, Di Francesco V, et al. Health consequences of obesity in the elderly: a review of four unresolved questions. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:1011–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaslavsky O, Rillamas-Sun E, LaCroix AZ, Woods NF, Tinker LF, Zisberg A, et al. Association between anthropometric measures and long-term survival in frail older women: observations from the women's health initiative study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:277–84. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Committee of Childhood and Adolescence of the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity, author. Obesity in children and adolescents. 3rd ed. The Korean Society for the Study of Obesity; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim BY, Kang SM, Kang JH, Kang SY, Kim KK, Kim KB, et al. 2020 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity guidelines for the management of obesity in Korea. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2021;30:81–92. doi: 10.7570/jomes21022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly AS, Barlow SE, Rao G, Inge TH, Hayman LL, Steinberger J, et al. Severe obesity in children and adolescents: identification, associated health risks, and treatment approaches: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:1689–712. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182a5cfb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossman DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, Curry SJ, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force, author. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317:2417–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bays HE, Chapman RH, Grandy S SHIELD Investigators' Group, author. The relationship of body mass index to diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: comparison of data from two national surveys. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:737–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodarzi MO. Genetics of obesity: what genetic association studies have taught us about the biology of obesity and its complications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:223–36. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qasim A, Turcotte M, de Souza RJ, Samaan MC, Champredon D, Dushoff J, et al. On the origin of obesity: identifying the biological, environmental and cultural drivers of genetic risk among human populations. Obes Rev. 2018;19:121–49. doi: 10.1111/obr.12625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyznicki JM, Young DC, Riggs JA, Davis RM Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association, author. Obesity: assessment and management in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:2185–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bray GA, Heisel WE, Afshin A, Jensen MD, Dietz WH, Long M, et al. The science of obesity management: an endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2018;39:79–132. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force, author. Behavioral weight loss interventions to prevent obesity-related morbidity and mortality in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1163–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, Garber AJ, Hurley DL, Jastreboff AM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22 Suppl 3:1–203. doi: 10.4158/EP161365.GL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez-Santos MT, Judge A, Gulati M, Spector TD, Hart DJ, Newton JL, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with knee and hand osteoarthritis: a community-based study of women. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48:791–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie L, Chen Y, Tan A, Gao Y, Yang X, Mo Z, et al. Central obesity indicating a higher prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms: a case-control matching analysis from a Chinese cross-sectional study in males. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2019;11:O135–40. doi: 10.1111/luts.12231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell T, Duntley S. Sleep disordered breathing in the elderly. Am J Med. 2011;124:1123–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim S, Kwon SY, Yoon JW, Kim SY, Choi SH, Park YJ, et al. Association between body composition and pulmonary function in elderly people: the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:631–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnold M, Freisling H, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Kee F, O'Doherty MG, Ordóñez-Mena JM, et al. Overweight duration in older adults and cancer risk: a study of cohorts in Europe and the United States. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:893–904. doi: 10.1007/s10654-016-0169-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KR, Hwang IC, Han KD, Jung J, Seo MH. Waist circumference and risk of breast cancer in Korean women: a nationwide cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2018;142:1554–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoo S, Oh S, Park J, Cho SY, Cho MC, Son H, et al. Effects of metabolic syndrome on the prevalence of prostate cancer: historical cohort study using the National Health Insurance Service Database. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:775–80. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-02842-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villareal DT, Apovian CM, Kushner RF, Klein S American Society for Nutrition; NAASO, The Obesity Society, author. Obesity in older adults: technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:923–34. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.5.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park S, Joo YH, McIntyre RS, Kim B. Metabolic syndrome and elevated C-reactive protein levels in elderly patients with newly diagnosed depression. Psychosomatics. 2014;55:640–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danat IM, Clifford A, Partridge M, Zhou W, Bakre AT, Chen A, et al. Impacts of overweight and obesity in older age on the risk of dementia: a systematic literature review and a meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70(s1):S87–99. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jee SH, Sull JW, Park J, Lee SY, Ohrr H, Guallar E, et al. Bodymass index and mortality in Korean men and women. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:779–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amiri S, Behnezhad S, Hasani J. Body mass index and risk of frailty in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Medicine. 2020;18:100196. doi: 10.1016/j.obmed.2020.100196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neri SG, Oliveira JS, Dario AB, Lima RM, Tiedemann A. Does obesity increase the risk and severity of falls in people aged 60 years and older? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75:952–60. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seimon RV, Wild-Taylor AL, Keating SE, McClintock S, Harper C, Gibson AA, et al. Effect of weight loss via severe vs moderate energy restriction on lean mass and body composition among postmenopausal women with obesity: the TEMPO diet randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1913733. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim S, Kim M, Won CW. Validation of the Korean version of the SARC-F Questionnaire to assess sarcopenia: Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:40–5.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang X, Xie X, Dou Q, Liu C, Zhang W, Yang Y, et al. Association of sarcopenic obesity with the risk of all-cause mortality among adults over a broad range of different settings: a updated meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:183. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1195-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S102–38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yumuk V, Tsigos C, Fried M, Schindler K, Busetto L, Micic D, et al. European guidelines for obesity management in adults. Obes Facts. 2015;8:402–24. doi: 10.1159/000442721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wharton S, Lau DC, Vallis M, Sharma AM, Biertho L, Campbell-Scherer D, et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. CMAJ. 2020;192:E875–91. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.191707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bays JC. Mindful eating: a guide to rediscovering a healthy and joyful relationship with food. Shambhala; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alberts HJ, Thewissen R, Raes L. Dealing with problematic eating behaviour: the effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on eating behaviour, food cravings, dichotomous thinking and body image concern. Appetite. 2012;58:847–51. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mason AE, Lustig RH, Brown RR, Acree M, Bacchetti P, Moran PJ, et al. Acute responses to opioidergic blockade as a biomarker of hedonic eating among obese women enrolled in a mindfulness-based weight loss intervention trial. Appetite. 2015;91:311–20. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rogers JM, Ferrari M, Mosely K, Lang CP, Brennan L. Mindfulness-based interventions for adults who are overweight or obese: a meta-analysis of physical and psychological health outcomes. Obes Rev. 2017;18:51–67. doi: 10.1111/obr.12461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braden A, Ferrell E, Anderson LN, Grant J, Watford T, Barnhart W. Adapted dialectical behavioral therapy for overweight/obese emotional eaters. Obesity. 2020;28:46. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chung YL, Rhie YJ. Severe obesity in children and adolescents: metabolic effects, assessment, and treatment. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2021;30:326–35. doi: 10.7570/jomes21063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haskins IN, Amdur R, Vaziri K. The effect of smoking on bariatric surgical outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:3074–80. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3581-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di Lorenzo N, Antoniou SA, Batterham RL, Busetto L, Godoroja D, Iossa A, et al. Clinical practice guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) on bariatric surgery: update 2020 endorsed by IFSO-EC, EASO and ESPCOP. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:2332–58. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-07555-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudolph A, Hilbert A. Post-operative behavioural management in bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2013;14:292–302. doi: 10.1111/obr.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stewart F, Avenell A. Behavioural interventions for severe obesity before and/or after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2016;26:1203–14. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1873-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Z, Zhou X, Fu W. Vitamin D supplementation for the prevention of vitamin D deficiency after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:1061–70. doi: 10.1038/s41430-017-0059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Styne DM, Arslanian SA, Connor EL, Farooqi IS, Murad MH, Silverstein JH, et al. Pediatric obesity-assessment, treatment, and prevention: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:709–57. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bolling CF, Armstrong SC, Reichard KW, Michalsky MP Section on Obesity, Section on Surgery, author. Metabolic and bariatric surgery for pediatric patients with severe obesity. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20193224. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Armstrong SC, Bolling CF, Michalsky MP, Reichard KW Section on Obesity, Section on Surgery, author. Pediatric metabolic and bariatric surgery: evidence, barriers, and best practices. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20193223. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pratt JS, Browne A, Browne NT, Bruzoni M, Cohen M, Desai A, et al. ASMBS pediatric metabolic and bariatric surgery guidelines, 2018. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:882–901. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nabuco HC, Tomeleri CM, Fernandes RR, Sugihara Junior P, Cavalcante EF, Cunha PM, et al. Effect of whey protein supplementation combined with resistance training on body composition, muscular strength, functional capacity, and plasma-metabolism biomarkers in older women with sarcopenic obesity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2019;32:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Han TS, Wu FC, Lean ME. Obesity and weight management in the elderly: a focus on men. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27:509–25. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daigle CR, Andalib A, Corcelles R, Cetin D, Schauer PR, Brethauer SA. Bariatric and metabolic outcomes in the super-obese elderly. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haywood C, Sumithran P. Treatment of obesity in older persons: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2019;20:588–98. doi: 10.1111/obr.12815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heymsfield SB, Peterson CM, Thomas DM, Heo M, Schuna JM, Hong S, et al. Scaling of adult body weight to height across sex and race/ethnic groups: relevance to BMI. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:1455–61. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.088831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.World Health Organization, author. The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. WHO; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seo MH, Kim YH, Han K, Lee WY, Yoo SJ. Prevalence of obesity and incidence of obesity-related comorbidities in Koreans based on National Health Insurance Service Health Checkup Data 2006-2015 (J Obes Metab Syndr 2018;27: 46-52) J Obes Metab Syndr. 2018;27:198–9. doi: 10.7570/jomes.2018.27.3.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tobias DK, Pan A, Jackson CL, O'Reilly EJ, Ding EL, Willett WC, et al. Body-mass index and mortality among adults with incident type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:233–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Twig G, Afek A, Derazne E, Tzur D, Cukierman-Yaffe T, Gerstein HC, et al. Diabetes risk among overweight and obese metabolically healthy young adults. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2989–95. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abdullah A, Peeters A, de Courten M, Stoelwinder J. The magnitude of association between overweight and obesity and the risk of diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89:309–19. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schienkiewitz A, Schulze MB, Hoffmann K, Kroke A, Boeing H. Body mass index history and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:427–33. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Strazzullo P, D'Elia L, Cairella G, Garbagnati F, Cappuccio FP, Scalfi L. Excess body weight and incidence of stroke: meta-analysis of prospective studies with 2 million participants. Stroke. 2010;41:e418–26. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.576967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rea TD, Heckbert SR, Kaplan RC, Psaty BM, Smith NL, Lemaitre RN, et al. Body mass index and the risk of recurrent coronary events following acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:467–72. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)01720-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, et al. Prospective Studies Collaboration, author. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1083–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee SY, Park HS, Kim DJ, Han JH, Kim SM, Cho GJ, et al. Appropriate waist circumference cutoff points for central obesity in Korean adults. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2985–3023. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Muscogiuri G, El Ghoch M, Colao A, Hassapidou M, Yumuk V, Busetto L, et al. European guidelines for obesity management in adults with a very low-calorie ketogenic diet: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Facts. 2021;14:222–45. doi: 10.1159/000515381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.American College of Sports Medicine, author. ACSM's exercise testing and prescription. 11th ed. Wolter Kluwer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Go G. Physical activity status and task. Health Welf Policy Forum. 2013;198:38–47. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK, et al. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:459–71. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim KB, Kim K, Kim C, Kang SJ, Kim HJ, Yoon S, et al. Effects of exercise on the body composition and lipid profile of individuals with obesity: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2019;28:278–94. doi: 10.7570/jomes.2019.28.4.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.González-Nóvoa JA, Campanioni S, Busto L, Fariña J, Rodríguez-Andina JJ, Vila D, et al. Improving intensive care unit early readmission prediction using optimized and explainable machine learning. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:3455. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liguori G American College of Sports Medicine, author. ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 10th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morze J, Rücker G, Danielewicz A, Przybyłowicz K, Neuenschwander M, Schlesinger S, et al. Impact of different training modalities on anthropometric outcomes in patients with obesity: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22:e13218. doi: 10.1111/obr.13218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oppert JM, Bellicha A, van Baak MA, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, et al. Exercise training in the management of overweight and obesity in adults: synthesis of the evidence and recommendations from the European Association for the Study of Obesity Physical Activity Working Group. Obes Rev. 2021;22 Suppl 4:e13273. doi: 10.1111/obr.13273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]