Clinical and Other Risk Indicators for Early Periodontitis in Adults (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2005 Sep 21.

Published in final edited form as: J Periodontol. 2005 Apr;76(4):573–581. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.4.573

Abstract

Background

Periodontal diseases affect over half the adults in the U.S., disproportionately affecting minority populations. Periodontitis can be treated in early stages, but it is not clear what features indicate, or could be risk factors for, early stages of periodontal attachment loss. This study aimed to evaluate associations between clinical and other risk indicators of early periodontitis.

Methods

A cross-sectional evaluation of 225 healthy and early periodontitis adults aged 20 to 40 years was performed. Clinical measurements, demographic information, and smoking histories were recorded. Analyses evaluated demographic and clinical associations with health and early periodontitis disease categories and periodontal attachment loss. Patterns of attachment loss at interproximal and buccal/lingual sites were evaluated.

Results

Subject age, plaque, and measures of gingivitis exhibited associations with attachment loss and probing depth. More periodontal attachment loss was detected in African-American and Hispanic subjects compared to Asian and Caucasian subjects. Smoking history was associated with attachment loss. At interproximal sites, lower molars most frequently had attachment loss, whereas at buccal/lingual sites, higher proportions of lower bicuspid teeth demonstrated attachment loss compared with other sites.

Conclusions

In this study of subjects with minimal attachment loss, gingival inflammation was associated with early periodontitis. Lower molar interproximal sites were frequently associated with interproximal attachment loss, whereas lower bicuspid teeth were at risk for gingival recession on buccal surfaces.

Keywords: Bicuspid, gingival recession/etiology, molar, periodontal attachment loss/etiology, periodontitis/etiology, risk factors

Periodontitis affects over half of the adults in the United States1 and can lead to discomfort, reduced masticatory ability, and in severe cases oral abscesses and tooth loss. Furthermore, periodontal disease has been implicated as a possible risk factor for several systemic conditions including cardiovascular diseases,2,3 and low birth weight and premature infants.4–6 In the United States, periodontal diseases disproportionately affect people of lower socioeconomic groups, with above average levels of disease reported in Hispanic and African American populations.1 In its early stages, however, it is possible to treat periodontitis successfully and prevent or control disease progression. Thus, it would be better to detect and treat this infection early, rather than face oral and possible systemic problems associated with moderate or severe periodontal loss.

Periodontal status has been classified in different ways. A classification based on infection as the principal etiology of periodontal diseases divides categories based on gingival inflammation and periodontal attachment loss and recognizes health, gingivitis, and periodontitis as separate entities.7 Separation of gingivitis from periodontitis suggests that there are differences in these conditions that might include type or severity of infection, and/or adequacy of host response. Clinical characteristics associated with periodontal loss in subjects with moderate to advanced periodontitis have included presence of plaque, gingival redness, bleeding on probing, periodontal pocketing, and periodontal attachment loss.1,8–10 The best indicator for future periodontal attachment loss in adult periodontitis was extent of existing attachment loss,8,10,11 whereas in early-onset periodontitis, presence of gingivitis was strongly associated with future periodontal attachment loss.12 Cigarette smoking is another important risk factor for moderate to advanced periodontitis.13–15

The aim of this study is to evaluate associations between clinical measures and other subject characteristics to determine risk indicators of early (or initial) periodontitis in adults. Characteristics that showed positive associations with early attachment loss would be of value in assessing periodontal risk. This study involves a cross-sectional design of healthy adults 20 to 40 years of age using baseline data from an ongoing longitudinal study that seeks progressing periodontal sites in periodontally healthy and early periodontitis subjects. Study findings indicate associations between early periodontal loss and measures of inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject Recruitment

Periodontally healthy and early periodontitis subjects were recruited to three dental clinics in the Boston area: The Forsyth Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the Clinical Research Center at Boston University School of Dental Medicine. All clinics used several methods to recruit subjects including newspaper and radio advertisements, and e-mail to faculty and staff in a large inter-institution network.

Volunteers underwent a clinical screening examination to evaluate eligibility for the study. General entry requirements were that subjects be between 20 and 40 years of age, be medically healthy, not pregnant or lactating, had not taken antibiotics or had a dental cleaning in the previous 6-month period, and had no previous periodontal therapy other than routine cleaning appointments. Periodontal entry requirements were that subjects should have at least 24 teeth not including third molars; a mean periodontal attachment level of less than 2.0 mm; and should not have generalized recession. Thus, subjects with moderate or advanced periodontitis were excluded. Subjects had to be willing to undergo periodontal and microbial monitoring at 6 monthly intervals for 2 years, although this report is restricted to the baseline data. The study design was explained to all subjects and those willing to sign an informed consent approved by the Institutional Review Boards of participating clinics were accepted into the study. Subjects were offered $50 for their participation in the clinical measurement visit.

Clinical Measurements

On entry into the study, subjects completed a medical and dental history and a questionnaire that included racial and ethnic background, and a history of cigarette smoking or other tobacco use.

Clinical measurements at each visit included: duplicate measurements of probing depth (PD) and periodontal attachment level (AL),16 and single assessments of plaque index,17 gingival index,18 and bleeding on probing recorded after the first set of probing depth measurements. Measurements were made at six sites on all teeth, except third molars, at the mesio-buccal, buccal, disto-buccal, disto-lingual, lingual, and mesio-lingual positions using a PCP-UNC-15 probe and measured to the nearest 0.5 mm.19 Radiographs were not taken. Subjects were offered a professional periodontal cleaning at the completion of clinical measurements.

Clinicians underwent training and calibration to promote uniformity of methods and to maximize within examiner reproducibility and between examiner agreement.20 Clinicians were trained by the clinician at the Forsyth Institute (the primary examiner) who had monitored a similar population of healthy and early periodontitis subjects.19 The reproducibility of the primary examiner was evaluated by comparing single sets of PD and AL measurements on eight subjects made on two occasions one week apart. Intraclass correlations of 0.77 for PD and 0.74 for AL were obtained. The intraclass correlations for duplicate measurements were then estimated from these values according to the formula of Fleiss21 to be 0.87 for PD and 0.85 for AL. The averages of week 1 and week 2 measurements were then used to establish interclass correlations between the primary examiner and the examiners at the two other clinics. These values were 0.81 for PD and 0.67 for AL. While the calibration exercise used a single measure of each site at two separate visits, the clinical protocols used duplicate PD and AL measures at each visit.

Statistical Analyses

Subjects were divided into three disease groups according to the following criteria. Healthy subjects had no sites with >2 mm periodontal attachment loss, and had a mean attachment level of ≤1.5 mm. Early periodontitis subjects had one or more sites with >2 mm periodontal attachment loss. Early periodontitis subjects were further divided into subjects with mean attachment level ≤1.5 mm (early periodontitis 1) and those with mean attachment level ≥1.5 mm (early periodontitis 2). Means of clinical measurements, number of sites with PD >3 mm, and number of sites with periodontal attachment loss >2 mm were calculated for each subject.

Non-parametric analysis of variance was used to evaluate associations between subject disease category and age and clinical measurements. Contingency tables were used to evaluate associations between disease category, gender, smoking history, and race-ethnicity. The significance of the associations was evaluated by chi square analyses. Trends in clinical measurements with increasing periodontal attachment loss were evaluated by Mantel-Haenszel chi square tests. Means of clinical and other measures were examined in the four dominant racial or ethnic groups, Asian, African-American, Hispanic, and Caucasian.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients estimated associations between clinical measurements. Scatter plots illustrated associations between subjects’ mean periodontal attachment level, mean gingival index, and mean percent bleeding on probing. The distribution of percent of sites with interproximal and buccal/lingual probing depths >3 mm at maxillary and mandibular teeth were compared. The percent of sites affected was computed by tooth type for each subject and then averaged across subjects. Similar distributions were computed for attachment loss >2 mm for subjects grouped according to overall number of sites affected. The distribution of percent of sites with >2 mm attachment loss was examined by tooth type separately in subjects with one to two, three to six, seven to 15, or over 16 affected sites at interproximal sites and buccal or lingual sites in maxillary and mandibular teeth.

RESULTS

Two hundred and twenty-five healthy or early periodontitis subjects were enrolled into this study. The general and demographic characteristics of subject groups are in Table 1. Of the 225 subjects, 52 were considered to be periodontally healthy, 120 belonged in the early periodontitis 1 (EP1) category, and 53 subjects belonged in the early periodontitis 2 (EP2) category. Subject age was associated with increased periodontal loss. A higher proportion of healthy subjects was female, whereas a higher proportion of subjects with over 1.5 mm mean periodontal attachment loss (EP2) was male. There was a trend for healthy subjects to be never smokers, whereas a slightly higher proportion of former and current smokers were in the early periodontitis categories. There were significant differences in distribution of the four larger racial/ethnic groups across disease categories. A higher proportion of African-American and Hispanic subjects were found in the EP2 category relative to Caucasian and Asian subjects, whereas Caucasian and Asian subjects were higher in the EP1 category.

Table 1.

General Characteristics of Study Population

| All Subjects (N = 225) | Health (N = 52) | Early Periodontitis 1 (N = 120) | Early Periodontitis 2 (N = 53) | Significance (H, EP1, EP2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) ± SEM* | 29.3 ± 0.43 | 26.6 ± 0.70 | 29.3 ± 0.56 | 32.0 ± 0.96 | P <0.0001† | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female (N) | 127 (56%) | 37 (71%) | 65 (54%) | 25 (47%) | P = 0.0136‡ | |

| Male (N) | 98 (44%) | 15 (29%) | 55 (46%) | 28 (53%) | ||

| Smoke | ||||||

| Never (N) | 158 (70%) | 44 (84%) | 80 (67%) | 34 (64%) | ] | P = 0.0201‡ |

| Former (N) | 33 (15%) | 4 (8%) | 21 (18%) | 8 (15%) | ||

| Current (N) | 33 (15%) | 4 (8%) | 18 (15%) | 11 (21%) | ||

| Ethnicity/Race | ||||||

| Asian (N) | 19 (8%) | 4 (21%) | 12 (63%) | 3 (16%) | ] | _P_= 0.0020§ |

| African American (N) | 35 (16%) | 2 (6%) | 20 (57%) | 13 (37%) | ||

| Hispanic (N) | 16 (7%) | 6 (37%) | 2 (13%) | 8 (50%) | ||

| Caucasian (N) | 144 (64%) | 37 (26%) | 79 (55%) | 28 (19%) | ||

| Other (N) | 11 (5%) | 3 (27%) | 7 (63%) | 1 (10%) |

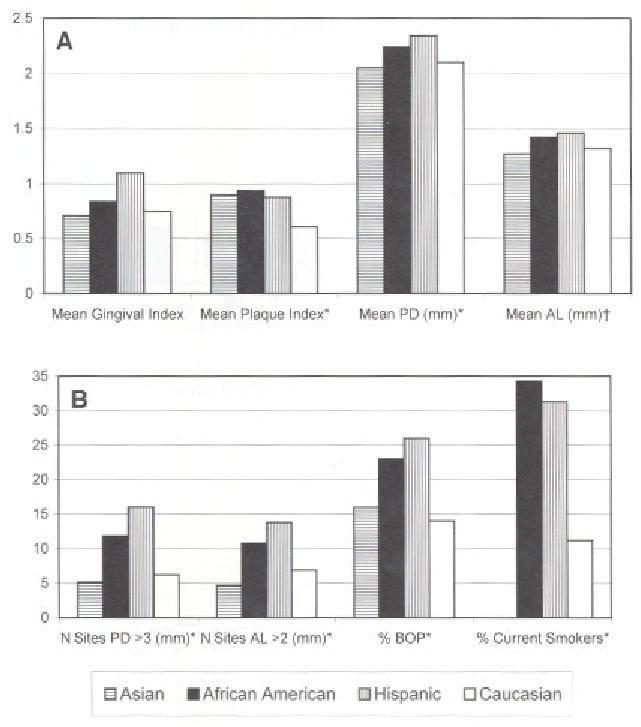

The clinical characteristics of subjects in disease categories are in Table 2. There were positive associations between gingival index, bleeding on probing, and plaque index, and the clinical groups. Measures of periodontal attachment level, which were used to define the clinical groups, and measures of probing depth showed the progression to be what would be expected. No significant associations by Kruskal-Wallis test were observed between tobacco smoking (never, former, and current smokers) and gingival index (P = 0.1726), percent sites bleeding on probing (P = 0.5362), plaque index (P = 0.1230), or subject age (P = 0.3828) (data not presented). There were differences in smoking history among racial/ethnic groups (P = 0.0059 chi square). Eighteen of 19 Asian subjects were non-smokers. While the majority of African-American and Hispanic subjects were non-smokers, (60% and 62% respectively), more were current smokers than in the other two ethnic/racial groups. Figure 1 illustrates that African-American and Hispanic subjects also showed higher levels of periodontal attachment loss and bleeding on probing than other study subjects.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Study Population

| Health (N = 52) | Early Periodontitis 1 (N = 120) | Early Periodontitis 2 (N = 53) | Significance* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gingival index ± SEM† | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.76 ± 0.04 | 1.18 ±0.08 | P <0.0001 |

| Plaque index ± SEM | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 0.86 ± 0.09 | P = 0.0002 |

| BOP (%) ± SEM | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 13.1 ± 1.2 | 36.0 ±3.6 | P <0.0001 |

| Probing depth (mm) ± SEM | 1.98 ±0.02 | 2.05 ±0.01 | 2.48 ± 0.04 | |

| Attachment level (mm) ± SEM | 1.13 ± 0.02 | 1.29 ± 0.01 | 1.68 ± 0.02 | |

| Sites PD >3 mm ± SEM | 0.29 ± 0.10 | 4.21 ± 0.46 | 23.26 ± 2.15 | |

| Sites AL >2 mm ± SEM | 0 | 5.28 ± 0.39 | 21.32 ± 1.46 |

Figure 1.

Clinical characteristics of subjects by ethnic and racial group A) shows deeper mean PD and periodontal AL in African-American and Hispanic subjects. B) African-American and Hispanic subjects had higher percent of sites BOP, sites with PD >3 mm and AL > 2 mm, and higher proportions of current smokers. *P >_0.001; †_P >0.02.

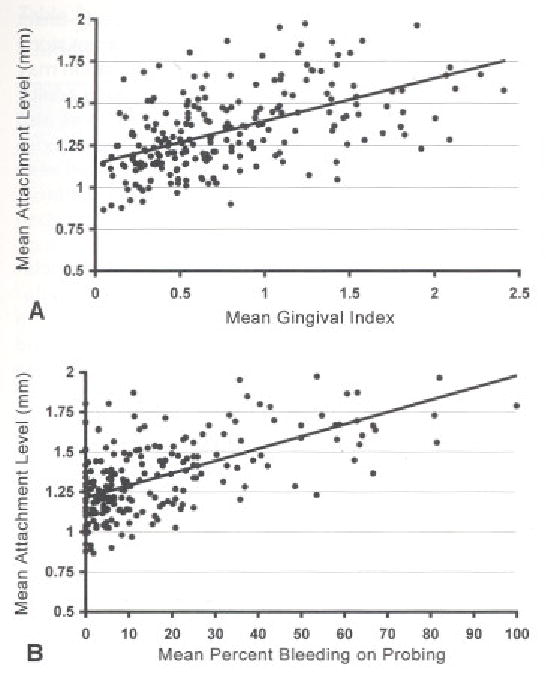

Pair-wise associations between clinical measures (Table 3) were quite high among plaque index, gingival index, and percent sites bleeding on probing (Spearman Rank coefficient 0.65 to 0.70). Correlations for plaque scores with measures of attachment level and probing depth were modest (coefficients 0.25 to 0.42) although statistically significant. Gingival index and percent sites bleeding on probing exhibited stronger associations with attachment level and probing depth (Spearman Rank coefficients 0.47 to 0.61 and 0.51 to 0.63, respectively). Not surprisingly, attachment level and probing depth were highly correlated. Scatter plots in Figure 2 illustrate strong associations of periodontal attachment level with gingival index (A) and with bleeding on probing (B).

Table 3.

Associations Between Clinical Measurements in Healthy and Early Periodontitis Adults*

| Coefficient | Plaque Index | Gingival Index | BOP (%) | PD (mm) | AL (mm) | Number Sites PD >3 mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gingival index † | 0.685 | |||||

| BOP (%)† | 0.651 | 0.699 | ||||

| PD† | 0.250 | 0.472 | 0.516 | |||

| AL† | 0.362 | 0.546 | 0.568 | 0.843 | ||

| N sites PD >3 mm† | 0.417 | 0.611 | 0.629 | 0.767 | 0.763 | |

| N sites AL >2 mm† | 0.352 | 0.592 | 0.586 | 0.666 | 0.837 | 0.809 |

Figure 2.

Subject mean periodontal attachment levels plotted against, mean gingival index (A) and mean percent bleeding on probing (B). Mean attachment levels ranged from 0.8 mm to 2 mm. There were significant positive associations (Table 3) between mean attachment levels and both these measures of gingival inflammation.

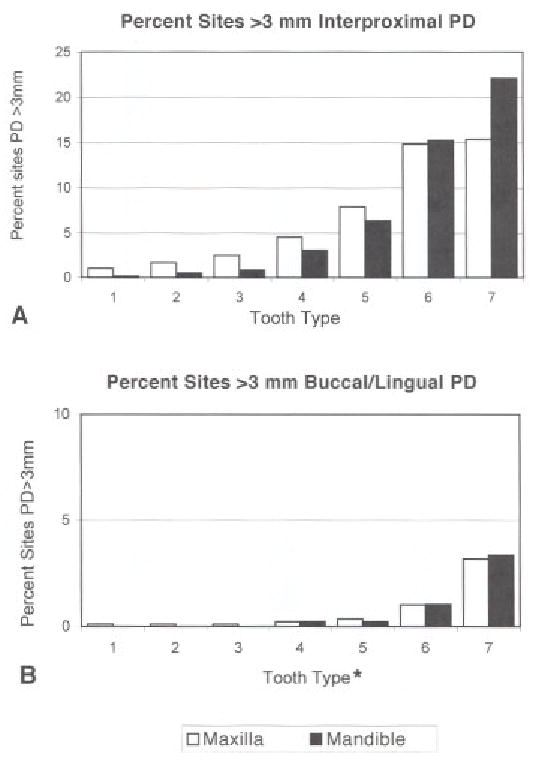

The prevalence of interproximal sites with probing depths >3 mm showed a marked anterior to posterior gradient in both maxillary and mandibular teeth (Fig. 3A). At buccal-lingual sites (Fig. 3B) the prevalence of probing depths >3 mm was notably lower at all tooth types, and almost completely confined to posterior teeth.

Figure 3.

Percents of sites by tooth type with PD >3 mm. A) Illustrates interproximal sites. B) Illustrates buccal and lingual sites, using a smaller scale than for interproximal sites. At interproximal sites, posterior teeth were more often affected than anterior teeth, with lower second molars showing more sites with loss than other teeth. There were fewer sites with periodontal pockets >3 mm loss at buccal and lingual sites compared with interproximal sites, although the distributionacross tooth types of buccal/lingual PD was similar to that of interproximal sites. *Tooth sites are ordered 1 = central incisor, to 7=second molar:

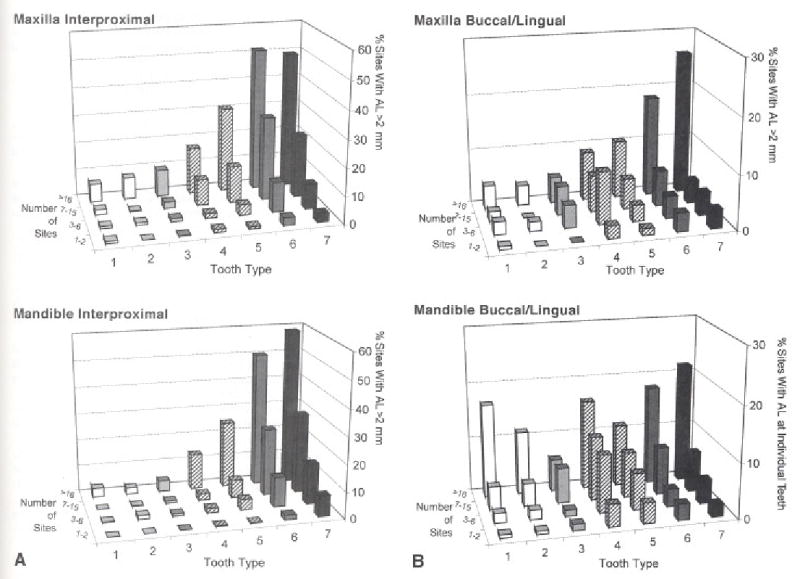

The prevalence of sites with attachment level >2 mm is given (Fig. 4) by tooth type for subjects grouped by the total number of sites with attachment level >2 mm, illustrating prevalence by tooth type in subjects with increasing levels of severity. In upper and lower (Fig. 4A) interproximal sites, attachment loss is predominantly located in the molars for subjects with only one or two affected sites. In subjects exhibiting larger numbers of involved sites, the prevalence of sites with loss steadily increases in the molars and also systematically progresses to adjacent teeth. In upper and lower buccal/lingual sites (Fig. 4B), prevalence was more diffuse, involving bicuspids, particularly in mandibular teeth in low severity subjects, and incisors and canines in subjects with higher numbers of affected sites.

Figure 4.

Teeth with periodontal attachment loss grouped by number of sites with AL > 2 mm (1–2, 3–6, 7–15 or >16 sites) to reflect subjects disease severity. Teeth are ordered 1=central incisor; to 7 = second molar. A) Mandibular lower molars were most frequently affected at all levels of subjects’ disease severity. B) There were generally fewer sites with loss at buccal and lingual sites compared by tooth type with interproximal sites. The distribution of maxillary buccal/lingual sites with attachment loss was similar to that of interproximal sites. The distribution of mandibular buccal/lingual sites with attachment loss showed a different pattern with the lower first bicuspid (tooth 4), as well as incisors and canines, exhibiting increased frequencies of periodontal attachment loss.

DISCUSSION

In this study we compared periodontally healthy adults with adults showing early signs of periodontal disease, which was defined as subjects with one or more sites with 2 mm of periodontal attachment loss, and a mean AL no more than 2 mm.19 This definition of early periodontitis included subjects who would probably be classified as periodontally healthy in other investigations.22–24 Despite the modest amount of periodontal loss, several risk indicators of moderate to advanced periodontitis were found associated with early attachment loss. Associations in this report were unadjusted for potential selection risk bias such as age, gender, and ethnicity. Attachment loss was associated with subject age, gingival index, and bleeding on probing. The association of increasing periodontal disease with subject age has been extensively documented, particularly in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHAMES III) that included subjects in the same age range25 as ours, also in the detailed analysis of survey subjects over 30 years of age with periodontal disease.1 The NHANES III used a cross-sectional design, as does the current investigation. Longitudinal studies have shown associations between subject age with progressing initial,19 moderate, and advanced periodontitis.8,26,27

Associations between measures of gingivitis and periodontitis have varied among populations examined. The association of percent of sites bleeding on probing with early periodontitis (EP1 and EP2 categories) was consistent with our previous report of initial periodontitis19 and with moderate to advanced periodontitis.8,9,26 We noted an association between gingival redness and progressing initial periodontitis,19 as was observed in minority populations with more advanced progressing disease,26 but this association was not significant in other studies of progressing adult periodontitis.8,10 Strong associations between gingivitis and increased, and increasing, attachment level were reported for subjects with early-onset periodontitis12,28 although the subjects were younger than those in the current study. In their early-onset periodontitis study,12,28 Albandar and coworkers suggested a significant association between gingival inflammation and development and progression of early-onset periodontitis. The data from the current study population suggest that this association may extend to early periodontitis in young adults. Amount of plaque (plaque index) was also associated with early periodontitis categories in the current study. Associations between amounts of plaque and periodontal attachment loss were also detected in an urban minority population of a similar age range to the current investigation.26 This association was not observed in other populations8,19 that included older subjects. In addition to associations of gingivitis and plaque with attachment loss, there were higher associations between measures of gingivitis and plaque than we had previously reported in a similar population with minimal periodontitis.29 While the populations were of similar age range, the population of the current study included more subjects with higher scores for plaque and gingival inflammation.

Other positive associations with the two early periodontitis categories were the race/ethnicity and, to a lesser extent, male gender and cigarette smoking. Differences in periodontal disease experience among differing racial/ethnic groups and genders were documented in the NHANES III data.1,15,25 The current study data, and that of the national surveys, detected higher measures of periodontitis among African-American and Hispanic subjects and in males. Comparisons between minority groups in the current study indicated that subjects of Asian heritage had a lower disease experience than African-American and Hispanic subjects, which is consistent with the report on a much larger urban population.26 In both latter reports,25,26 there were elevated proportions of current smokers in African-American and Hispanic subjects, compared to Asian and Caucasian subjects, as was observed in the current study population. Associations between increased plaque and periodontitis probably reflect the role of bacterial infection. Increased plaque could also reflect less access to dental care services as suggested for some minority subjects.26 Similarly in African-American and Hispanic subjects increased periodontitis may reflect socioeconomic factors that can be linked with poor access to dental care and general health care practices, including smoking.26,30 There was an association between early periodontitis and subject smoking, in particular a higher proportion of early periodontitis subjects were current or former smokers, whereas a higher proportion of healthy subjects were non-smokers. Thus the data are consistent with the associations of cigarette smoking with periodontitis.13–15,31

The prevalence of sites with PD >3 mm and sites with attachment level loss >2 mm was compiled by tooth type to identify sites more prone to early periodontal loss and thus likely sites of initiation of periodontitis. Periodontal pockets were most frequently detected at interproximal sites in molars, with lower frequencies going from posterior to anterior teeth. This pattern is similar to that reported for a cohort of 26 year-old New Zealand subjects,32 although there was more pocketing around lower cuspids than in the current study population. We detected lower frequencies of pockets at buccal/lingual sites than interproximally, also consistent with the New Zealand population,32 and other studies of more advanced periodontitis in older subjects.11,33 Sites with attachment loss >2 mm, in subjects grouped by number of affected sites, indicated that more sites showed attachment loss at interproximal sites compared with buccal/lingual sites. Furthermore, different patterns of sites with attachment loss were noted in interproximal compared with buccal and lingual sites. Mandibular second molar teeth at interproximal sites demonstrated attachment loss more frequently, and earlier in the disease process. As more interproximal sites were affected, the disease appeared to spread from molar, to bicuspid, to cuspid and incisor teeth. This pattern of loss is similar to that described in the NHANES III survey,1 and in the New Zealand study32 although the current study indicated proportionally more loss in mandibular molars than in the other reports.

Progressing attachment loss is manifested by increased periodontal pocketing, increased gingival recession, or both. Buccal and lingual sites were analysed separately from interproximal sites to evaluate the impact of gingival recession on periodontal loss. The pattern of probing depths at buccal/lingual sites was similar to, but lower than, that of interproximal sites. Attachment loss at buccal lingual sites in subjects with less than 16 affected sites was most frequently detected around bicuspids. As in the U.S. national survey data,9 first bicuspids showed more attachment loss than adjacent teeth, and mandibular incisors showed more loss than maxillary incisors. These data suggest that attachment loss at buccal/lingual sites starts with bicuspids, and then spreads to molar and incisor teeth in subjects with more than 16 affected sites. It is also possible that there is more than one pattern of periodontal disease progression.33 One disease pattern may start in the interproximal molars and spread to buccal/lingual sites on those and other teeth. A second disease pattern may initiate at bicuspid buccal/lingual sites and spread to other buccal/lingual sites to show attachment loss associated with gingival recession.19,33–35 The relative prevalence of sites with attachment loss over 2 mm suggests that periodontitis is initiated in molar teeth, and that lower bicuspids are more prone to gingival recession. Longitudinal evaluation of these subjects may confirm these patterns.

Summary and Conclusions

We performed a cross-sectional evaluation of healthy and early periodontitis adults aged 20 to 40 years. Periodontally healthy subjects had less than 1.5 mm mean periodontal attachment loss, and early periodontitis showed at least one site with over 2 mm attachment loss. Early periodontitis was associated with gingival inflammation, subject age, and cigarette smoking. More periodontal attachment loss was detected in African-American and Hispanic subjects compared with Asian and Caucasian subjects. We conclude that gingival inflammation may be associated with early periodontitis. Patterns of attachment loss by tooth type suggested that periodontitis is frequently initiated at interproximal molar sites. Ongoing follow-up of these subjects may help clarify how strongly gingival inflammation associates with detectable disease progression, whether additional factors may be important in progressive periodontitis, and which sites are most prone to disease initiation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Brian Thomas, Terry Jennings, and Kelly Willis at the Forsyth Institute; Nancy Mickels and Melissa Martins at the Clinical Research Center at Boston University School of Dental Medicine; and Manot Cyr and Lisa Newall at the Department of Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in assisting with subject recruitment and clinical measurements performed in this study, NIH grants DE09513 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and RR00533 from the National Center for Research Resources supported this study.

References

- 1.Albandar JM, Brunelle JA, Kingman A. Destructive periodontal disease in adults 30 years of age and older in the United States, 1988–1994. J Periodontol. 1999;70:13–29. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck JD, Slade G, Offenbacher S. Oral disease, cardiovascular disease and systemic inflammation. Periodontol 2000. 2000;23:110–120. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2230111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattila KJ, Asikainen S, Wolf J, Jousimies-Somer H, Valtonen V, Nieminen M. Age, dental infections, and coronary heart disease. J Dent Res. 2000;79:756–760. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790020901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeffcoat MK, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Goldenerg RL, Hauth JC. Periodontal infection and preterm birth: Results of a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:875–880. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeffcoat MK, Hauth JC, Geurs NC, et al. Periodontal disease and preterm birth: Results of a pilot intervention study. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1214–1218. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Offenbacher S, Lieff S, Boggess KA, et al. Maternal periodontitis and prematurity. Part I: Obstetric outcome of prematurity and growth restriction. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:164–174. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Lindhe J, Kent RL, Okamoto H, Yoneyama T. Clinical risk indicators for periodontal attachment loss. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:117–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb01700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albandar JM, Kingman A. Gingival recession, gingival bleeding, and dental calculus in adults 30 years of age and older in the United States, 1988–1994. J Periodontol. 1999;70:30–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy MS, Geurs NC, Jeffcoat RL, Proskin H, Jeffcoat MK. Periodontal disease progression. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1583–1590. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck JD, Cusmano L, Green-Helms W, Koch GG, Offenbacher S. A 5-year study of attachment loss in community-dwelling older adults: Incidence density. J Periodontal Res. 1997;32:506–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1997.tb00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albandar JM, Kingman A, Brown LJ, Löe H. Gingival inflammation and subgingival calculus as determinants of disease progression in early-onset periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:231–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calsina G, Ramon JM, Echeverria JJ. Effects of smoking on periodontal tissues. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:771–776. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haber J, Wattles J, Crowley M, Mandell R, Joshipura K, Kent RL. Evidence for cigarette smoking as a major risk factor for periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1993;64:16–23. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomar SL, Asma S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: Findings from NHANES III. J Periodontol. 2000;71:743–751. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Goodson JM. Subgingival temperature (I). Relation to baseline clinical parameters. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:401–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silness J, Löe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–135. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Löe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–551. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanner ACR, Maiden MF, Macuch PJ, Murray LL, Kent RL., Jr Microbiota of health, gingivitis, and initial periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:85–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polson AM. The research team, calibration, and quality assurance in clinical trials in periodontics. Ann Periodontol. 1997;2:75–82. doi: 10.1902/annals.1997.2.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleiss JL. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1986:15.

- 22.Haffajee AD, Cugini MA. Tanner A, et al. Subgingival microbiota in healthy, well-maintained elder and periodontitis subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomson WM, Edwards SJ, Dobson L, et al. IL-1 genotype and adult periodontitis among young New Zealanders. J Dent Res. 2001;80:1700–1703. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800080401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riviere GR, Smith KS, Tzagaroulaki E, et al. Periodontal status and detection frequency of bacteria at sites of periodontal health and gingivitis. J Periodontol. 1996;67:109–115. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown LJ, Brunelle JA, Kingman A. Periodontal status in the United States, 1988–1991: Prevalence, extent, and demographic variation. J Dent Res. 1996;75(Spec Issue):672–683. doi: 10.1177/002203459607502S07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craig RG, Yip JK, Mijares DQ, LeGeros RZ, Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Progression of destructive periodontal diseases in three urban minority populations: Role of clinical and demographic factors. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:1075–1083. doi: 10.1046/j.0303-6979.2003.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cullinan MP, Westerman B, Hamlet SM. et al. A longitudinal study of interleukin-1 gene polymorphisms and periodontal disease in a general adult population. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:1137–1144. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.281208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albandar JM, Brown LJ, Löe H. Clinical features of early-onset periodontitis. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:1393–1399. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanner A, Kent R, Maiden MF, Taubman MA. Clinical, microbiological and immunological profile of healthy, gingivitis and putative active periodontal subjects. J Periodontol Res. 1996;31:195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1996.tb00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolan TA, Gilbert CH, Ringelberg ML, et al. Behavioral risk indicators of attachment loss in adult Floridians. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:223–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albandar JM, Streckfus CF, Adesanya MR, Winn DM. Cigar, pipe, and cigarette smoking as risk factors for periodontal disease and tooth loss. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1874–1831. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.12.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomson WM, Hashim R, Pack AR. The prevalence and intraoral distribution of periodontal attachment loss in a birth cohort of 26-year-olds. J Periodontol. 2000;7l:1840–1345. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.12.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck JD, Koch GG. Characteristics of older adults experiencing periodontal attachment loss as gingival recession or probing depth. J Periodontal Res. 1994;29:290–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1994.tb01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page RC, Sturdivant EC. Noninflammatory destructive periodontal disease (NDPD) Periodontol 2000. 2002;30:24–39. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.03003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joshipura KJ, Kent RL, DePaola PF. Gingival recession: Intra-oral distribution and associated factors. J Periodontol. 1994;65:864–871. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.9.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]