Huntingtin and the molecular pathogenesis of Huntington's disease (original) (raw)

Summary

Fourth in Molecular Medicine Review Series

Keywords: Huntington's disease, huntingtin, polyglutamine, transcription, chaperones, proteasome

Huntington's disease (HD) is a late-onset neurodegenerative disorder that is caused by a CAG repeat expansion in the IT15 gene, which results in a long stretch of polyglutamine close to the amino-terminus of the HD protein huntingtin (htt). The normal function of htt, and the molecular mechanisms that contribute to the disease pathogenesis, are in the process of being elucidated. In this review, we outline the potential functions of htt as defined by the proteins with which it has been found to interact. We then focus on evidence that supports a role for transcriptional dysfunction and impaired protein folding and degradation as early events in disease pathogenesis.

Introduction

Huntington's disease (HD) is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by irrepressible motor dysfunction, cognitive decline and psychiatric disturbances, which lead to progressive dementia and death approximately 15–20 years after disease onset (Bates et al, 2002). It belongs to a family of neurodegenerative diseases caused by mutations in which an expanded CAG repeat tract results in long stretches of polyglutamine (polyQ) in the encoded protein. This family also includes dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA), spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA) and the spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) 1–3, 6, 7 and 17. Apart from their polyQ repeats, the proteins involved are unrelated, and although they are all widely expressed in the central nervous system and peripheral tissues, they lead to characteristic patterns of neurodegeneration. In HD, the selective neurodegeneration of the γ-aminobutyric acid-releasing spiny-projection neurons of the striatum is predominant, although loss of neurons in many other brain regions has also been reported. In the unaffected population, the number of CAG repeats in the IT15 gene that encodes the HD protein huntingtin (htt) varies from 6 to 35; repeats of 36 or more define an HD allele. The length of the CAG expansion is inversely correlated with age of disease onset, with cases of juvenile onset characterized by expansions of more than 60 repeats. HD has a prevalence of 5–10 cases per 100,000 worldwide, which makes it the most common inherited neurodegenerative disorder.

Huntingtin and Huntington's disease

The HD gene was cloned 11 years ago and since then an explosion of research has led to many insights into the normal function of htt and the molecular basis of the disease. htt is a 348-kDa multidomain protein that contains a polymorphic glutamine/proline-rich domain at its amino-terminus. The longer polyQ domain seems to induce conformational changes in the protein, which causes it to form intracellular aggregates that, in most cases, manifest as nuclear inclusions. However, aggregates can also form outside the nucleus. Despite its large size, the normal function of htt has been difficult to establish because it contains very little sequence homology to other known proteins, is ubiquitously expressed and is localized in many subcellular compartments (reviewed in Harjes & Wanker, 2003; Li & Li, 2004). htt is present in the nucleus, cell body, dendrites and nerve terminals of neurons, and is also associated with a number of organelles including the Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Various approaches have been used to determine the function of htt and its pathological effects, and it is becoming apparent that the role of htt is complex and that it operates at many different cellular levels (Harjes & Wanker, 2003; Li & Li, 2004). htt forms part of the dynactin complex, colocalizing with microtubules and interacting directly with β-tubulin, which suggests a role in vesicle transport and/or cytoskeletal anchoring. Interestingly, htt has also been shown to have a role in clathrin-mediated endocytosis, neuronal transport and postsynaptic signalling. Furthermore, htt can protect neuronal cells from apoptotic stress and therefore may have a prosurvival role (Rigamonti et al, 2000).

Recent studies suggest that neural degeneration in HD results from the combined effects of a gain of function in the mutated form of htt along with a loss of function in wild-type htt. Data from people with deletions in the HD allele argue against the idea that deficiencies in wild-type htt trigger neurodegeneration, as these patients do not develop HD. However, ablation of htt in mice results in death at embryonic day 7.5 owing to aberrant brain development, and its conditional deletion in the forebrain also leads to neurodegeneration. This suggests that htt is necessary for cell survival and that its loss of function can be involved in neurodegeneration (Bates & Murphy, 2002). Most efforts towards understanding the pathogenesis of HD have been driven by the gain-of-function hypothesis and by attempts to determine the mechanisms by which the polyQ tract causes neurodegeneration. Mutant htt and the other polyQ disease proteins form insoluble aggregates in neurons, although the role that aggregation has in the pathogenesis of polyQ diseases remains contentious (Bates, 2003). Whereas some researchers believe that polyQ aggregates are toxic, others suggest that they are a neutral by-product of the pathogenic process, and still others claim that the aggregates are neuroprotective.

A number of investigators have suggested that unusually long polyQ tracts induce disease because they interfere with the normal function of cellular proteins. Recent observations supporting this theory indicate that mutant htt impairs gene transcription, either by intranuclear aggregate formation or by sequestration of important transcription factors (for reviews, see Cha, 2000; Sugars & Rubinsztein, 2003). Numerous accounts have shown that transcription factors such as p53, CREB-binding protein (CBP), specificity protein 1 (SP1) and TATA-binding protein (TBP) can be recruited to intranuclear aggregates, thus reinforcing the hypothesis of a role for transcriptional deregulation in HD. Also, the accumulation of chaperones, proteasomes and ubiquitin in polyQ aggregates suggests that insufficient protein folding and degradation is implicated in the pathogenesis of polyQ disease (for reviews see Ciechanover & Brundin, 2003; Sakahira et al, 2002). Interestingly, the abnormal accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in the central nervous system is also involved in other neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's (Taylor et al, 2002). Therefore, it is possible that polyQ diseases arise from impaired folding or proteolysis, either as proteins become inherently difficult to refold or degrade, or by the impairment of the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS). Here, we review recent advances in determining the role of htt and its interacting proteins in transcriptional regulation, protein folding and protein degradation.

Transcriptional regulation

The transcription of DNA into messenger RNA is one of the most highly regulated processes in the cell. The expression of protein-encoding genes is regulated in an orchestrated and elaborate fashion, involving several transcription factors that must interact with each other and with the regulatory DNA elements that specify the activity of the gene. It is becoming increasingly evident that htt has an important role in transcription; a range of methods have shown that both wild-type and mutant htt interact with numerous transcription factors. Furthermore, microarray analysis has established that a number of transcriptional pathways are impaired in HD. However, the relevance of these interactions and how changes in transcription influence the disease pathogenesis remain unclear.

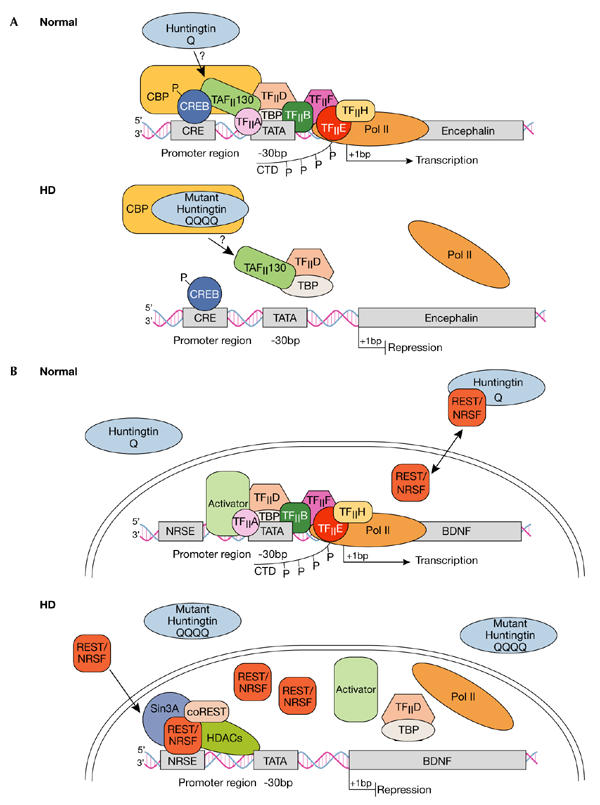

The cAMP-responsive element and SP1 pathways. Of the transcription pathways that are affected in HD, the cAMP-responsive element (CRE)- and the SP1-mediated pathways are the most extensively studied, owing to their involvement in the expression of genes needed for neuronal survival (see Fig 1A for a description of the CRE pathway). The ablation of CREB results in an HD-like phenotype in mice, in which there is progressive neurodegeneration in the hippocampus and striatum (Mantamadiotis et al, 2002), and the downregulation of CRE-regulated genes has also been detected in HD patients (Glass et al, 2000). Interest in the CRE pathway initially focused on CBP, which is sequestered into aggregates, and which led to the proposal that the availability of CBP for CRE-mediated transcription is disrupted (for reviews see Li & Li, 2004; Sugars & Rubinsztein, 2003). Interestingly, CBP can be sequestered into aggregates formed by several other polyQ proteins, including atrophin 1 (in DRPLA), the androgen receptor (in SBMA) and ataxin3 (in SCA-3). htt has been shown to interact with CBP through both its glutamine-rich and acetyltransferase domains; this may account for the observed decrease in CRE-mediated transcription and the loss of acetyltransferase activity seen in polyQ models of disease. Importantly, this reduction in acetyltransferase activity has been reversed by the administration of histone deacetylase enzyme inhibitors and, furthermore, this ameliorates neurodegeneration in cellular, fly and mouse models of HD, presumably by altering gene-expression patterns. However, a recent in vivo study reported that CRE-dependent transcription is upregulated in double-transgenic mice expressing mutant htt and a CRE-β-galactosidase reporter construct (Obrietan & Hoyt, 2004). Moreover, phosphorylated CREB levels were also elevated, as were the levels of the CREB-regulated gene product CCAAT-enhancer binding protein, which suggests that mutant htt facilitates CRE-dependent transcription. In addition to CBP, CRE-mediated transcription also appears to be affected by the coactivator TAFII130. This coactivator has also been found in aggregates and, on overexpression, inhibition of CREB-dependent transcription can be overcome (Shimohata et al, 2000).

Figure 1.

Dysregulation of cAMP-responsive-element- and NRSE-mediated transcription in Huntington's disease. (A) Normal: Huntingtin (htt) is predominantly located in the cytoplasm, although some reports indicate its presence in the nucleus. The transcription factor cAMP-responsive element (CRE)-binding protein (CREB) binds to DNA elements that contain CRE in cellular promoters such as in the encephalin gene, the activation of which is important in neuronal survival. Transcriptional activation is achieved by protein kinase A phosphorylation (P) of CREB, which allows for the subsequent recruitment of CREB-binding protein (CBP). CBP has intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity, which remodels chromatin into an open architecture, allowing for the subsequent recruitment of the TAFII130 subunit of TFIID by CREB, and after this, the general transcriptional machinery, which includes transcription factors TFIIA, B, D, E, F and H, and TATA-binding protein (TBP). Once correctly targeted, RNA polymerase II (Pol II) is phosphorylated in its carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) by TFIIH to initiate transcription. HD: Mutant htt disrupts CRE-mediated transcription by directly interacting with or sequestering CBP, and possibly TAFII130, in aggregates in the nucleus. Ultimately, CBP and TAFII130 are prevented from binding to CRE regions in cellular promoters, so the general transcription apparatus along with Pol II are not correctly targeted to the promoter, so transcriptional activation is impaired. (B) Normal: The transcription factor REST–NRSF binds to DNA elements called NRSEs in neuronal gene promoters such as in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene. Wild-type htt sustains the production of BDNF, which is an important survival factor for the striatal neurons that die in HD, by interacting with REST–NRSF in the cytoplasm, thereby reducing its availability in the nucleus to bind to NRSE sites. Under these conditions, transcription of BDNF is promoted as activators can bind to the BDNF promoter elements and subsequently recruit the general transcriptional machinery and Pol II. HD: Mutant htt fails to interact with REST–NRSF in the cytoplasm, which leads to increased levels of REST–NRSF in the nucleus. Under these conditions, REST–NRSF binds avidly to the NRSE and promotes the recruitment of Sin3A–histone-deacetylase complexes (HDACs) that have histone deacetylase activity for remodelling chromatin into a closed architecture, thereby suppressing the transcription of BDNF. NRSE, neuron-restrictive silencer element; NRSF, neuron-restrictive silencer factor, REST, repressor-element-1 transcription factor.

In a similar manner, mutant htt has been shown to disrupt SP1-mediated transcription by sequestering SP1 into aggregates, and also to disrupt the specific interaction of SP1 with the coactivator TAFII130. Dunah and colleagues showed that there is an enhanced association of mutant htt with SP1 in brain extracts from asymptomatic HD patients, and the association of SP1 with TAFII130 was reduced in HD brains compared with brains from healthy individuals (Dunah et al, 2002). Furthermore, the enhanced association of mutant htt with SP1 blocked the binding of SP1 to its promoter region, therefore impairing SP1-mediated transcription of genes—such as the dopamine-D2-receptor gene—that are known to be compromised in patients with HD. Strikingly, by overexpressing both SP1 and TAFII130, the inhibition of dopamine-D2-receptor gene expression by mutant htt was overcome, but when either was expressed alone, normal transcription was not restored.

Huntingtin and other transcriptional pathways. In addition to CBP and SP1, several other important transcription factors seem to interact with htt in the nucleus. Among them, the Gln-Ala repeat transcriptional coactivator CA150 has been found to associate with both normal and mutant htt (Holbert et al, 2001). Moreover, in HD brain samples, CA150 protein levels increase as the disease grade increases, which implies that CA150 accumulates in response to htt aggregation and that this interferes with gene transcription. Also, TBP might be involved in the pathology of HD as this general transcription factor has been localized to nuclear inclusions. Furthermore, an expansion in the polyQ region of TBP is known to induce SCA-17 disease, which shows overlapping features with HD (Stevanin et al, 2003). Interestingly, htt might also function as a transcriptional repressor. By yeast two-hybrid analysis, htt has been shown to interact directly with repressor complexes containing nuclear corepressor protein and Sin3A in a polyQ-dependent manner (Boutell et al, 1999). Nuclear corepressor protein and Sin3A act in concert with other transcriptional DNA-binding proteins to repress the transcriptional activation of nuclear receptors such as the thyroid and retinoic acid receptors. Therefore, mutant htt might interfere not only with nuclear corepressor protein and Sin3A function, but also with signalling pathways involving nuclear receptors.

NRSE-regulated pathways. It has been demonstrated recently that wild-type htt can also regulate the activity of genes that contain neuron-restrictive silencer elements (NRSEs) by modulating the cytoplasmic recruitment to the nucleus of NRSE-binding transcription factors (Zuccato et al, 2003; see Fig 1B for a description of the pathway). In this study, wild-type htt was shown to interact with the REST–NRSF (repressor-element-1 transcription factor–neuron-restrictive silencer factor) in the cytoplasm, reducing its availability for nuclear NRSE-binding sites and ultimately promoting the transcription of neuronal genes containing NRSEs. For example, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is regulated in this manner and is an important prosurvival factor for striatal neurons in the brain. However, in the presence of mutant htt, REST–NRSF fails to interact with wild-type htt in the cytoplasm, leading to pathological levels of REST–NRSF in the nucleus and the suppression of transcription of NRSE-regulated genes. This scenario leads to the loss of BDNF production and the subsequent death of striatal neurons as they no longer receive any trophic support. Also, as mutant htt could disrupt the beneficial activity of endogenous wild-type htt, it will be interesting to see how mutant htt abrogates the interaction of normal htt with REST–NRSF. It is possible that mutant htt directly affects the REST–NRSF system in the cytoplasm, or alternatively, a dominant-negative effect of mutant htt might take place by sequestering the wild-type protein into mutant htt aggregates.

Chaperones and the proteasome

Within cells, proteins are continually degraded into amino acids and are replaced by newly synthesized proteins. The folding of newly synthesized proteins into their correct conformation involves the sequential actions of several molecular chaperones, and this process can be unsuccessful (Fink, 1999). Thus, proteins must either be refolded into their correct conformation or be degraded by the UPS (Voges et al, 1999). Heatshock protein 70 (Hsp70) and Hsp40 are the two main classes of molecular chaperone that cooperate to facilitate the folding process and maintain polypeptides in a soluble conformation (Hartl & Hayer-Hartl, 2002). However, aggregation is a characteristic of abnormally folded proteins; thus, if the production of misfolded proteins exceeds the degradative capacity of the cell, these polypeptides can form insoluble intracellular aggregates. The UPS or molecular chaperones of the cell normally prevent aggregation—so only when they are unable to cope with the rate of misfolded protein production will these aggregates occur.

Impaired protein folding. htt, along with other polyQ proteins, has been shown to interact with the Hsp70 and Hsp40 family of chaperones, and also colocalizes with aggregates in both cellular and animal models of polyQ disease and patient tissue samples. This suggests that the impairment of protein folding gives rise to HD pathology (Sakahira et al, 2002; Fig 2). The sequestration of chaperones into aggregates decreases the amount of soluble chaperones that are available in the cell, and this presumably enhances abnormal protein folding (Hay et al, 2004). Indeed, the overexpression of Hsp70 and Hsp40 chaperones acts synergistically to rescue neurodegeneration in Drosophila (Bonini, 2002) and has been shown to alter the biochemical properties of fibrillar aggregates such that detergentsoluble amorphous structures are generated (Muchowski et al, 2000). Interestingly, it seems that only specific subclasses of molecular chaperones affect polyQ aggregation and toxicity. By RNA interference in various worm strains, Nollen and colleagues identified only two Hsp70s and one member of the DnaJ family of proteins that affected aggregation among all the chaperone genes analysed (Nollen et al, 2004). Also, this screen provides evidence that protein homeostasis requires a balance that extends well beyond the immediate involvement of chaperones. In addition to chaperones, other genes were identified that could affect polyQ-induced aggregation, including those that have roles in RNA synthesis, splicing and processing, and in protein synthesis, transport and degradation.

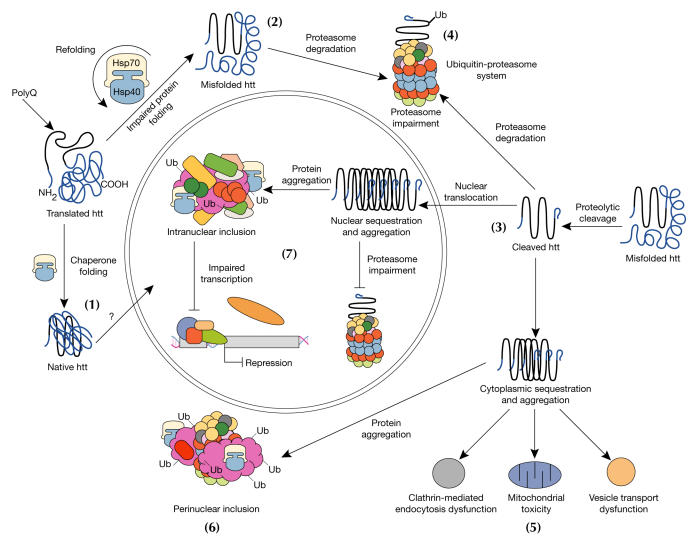

Figure 2.

Model for cellular pathogenesis in Huntington's disease. The molecular chaperones Hsp70 and Hsp40 promote the folding of newly synthesized huntingtin (htt) into a native structure. Wild-type htt is predominantly cytoplasmic and probably functions in vesicle transport, cytoskeletal anchoring, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, neuronal transport or postsynaptic signalling. htt may be transported into the nucleus and have a role in transcriptional regulation (1). Chaperones can facilitate the recognition of abnormal proteins, promoting either their refolding, or ubiquitination (Ub) and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome. The HD mutation induces conformational changes and is likely to cause the abnormal folding of htt, which, if not corrected by chaperones, leads to the accumulation of misfolded htt in the cytoplasm (2). Alternatively, mutant htt might also be proteolytically cleaved, giving rise to amino-terminal fragments that form β-sheet structures (3). Ultimately, toxicity might be elicited by mutant full-length htt or by cleaved N-terminal fragments, which may form soluble monomers, oligomers or large insoluble aggregates. In the cytoplasm, mutant forms of htt may impair the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS), leading to the accumulation of more proteins that are misfolded (4). These toxic proteins might also impair normal vesicle transport and clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Also, the presence of mutant htt could activate proapoptotic proteins directly or indirectly by mitochondrial damage, leading to greater cellular toxicity and other deleterious effects (5). In an effort to protect itself, the cell accumulates toxic fragments into ubiquitinated cytoplasmic perinuclear aggregates (6). In addition, mutant htt can be translocated into the nucleus to form nuclear inclusions, which may disrupt transcription and the UPS (7).

Failure of the ubiquitin–proteasome system. If chaperones cannot refold abnormal proteins correctly, they then promote their subsequent ubiquitination, which ultimately directs them to the proteasome for degradation. One feature of HD, along with other neurodegenerative diseases, is that inclusions have been found to be ubiquitinated and also associated with several proteasome subunits, which strongly suggests a failure in the degradative machinery of the cell (Ciechanover & Brundin, 2003; Fig 2). Several lines of evidence have indicated that impairment of the UPS is central to the pathogenesis of polyQ disease. The eukaryotic proteasome is incapable of digesting peptides containing stretches of 9–29Q residues, and these peptides must be released for further hydrolysis by unidentified peptidases (Venkatraman et al, 2004). Therefore, the attempted digestion of pathogenic polyQ tracts might result in aggregation-prone polyQ-containing fragments being released from the proteasome, or the failure of these tracts to exit might impair proteasome function. Consistent with this, transient transfection of htt fragments containing a pathogenic polyQ repeat caused almost complete inhibition of the UPS in a cell-based UPS reporter system, which implies that protein aggregation directly impairs the function of the UPS (Bence et al, 2001).

Induction of autophagy

During the final preparations of this review, a study identified the first protective role for cellular aggregates in polyQ disease. Ravikumar and colleagues report that the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is sequestered into htt aggregates, thereby decreasing its kinase activity in the cell. This ultimately leads to the induction of autophagy, which is a key clearance pathway for toxic htt fragments (Ravikumar et al, 2004). The autophagic pathway is an important cytoplasmic process responsible for the recycling of intracellular organelles and long-lived proteins, and also has an important role in cell death. Therefore, in polyQ disease, it appears that aggregates have a key role in inducing autophagy by sequestering and suppressing mTOR activity, which is a negative regulator of the autophagic pathway. Subsequently, by stimulating autophagy, the clearance of toxic cytosolic aggregate-prone proteins is enhanced and cellular toxicity is reduced.

Conclusion

htt is a multi-domain protein with many functions, including transcriptional regulation, intracellular transport and involvement in the endosome–lysosome pathway. The protein also has pro-survival properties. In this review, we have discussed two mechanisms that contribute to the early molecular pathogenesis of HD: transcriptional dysregulation and protein misfolding and degradation. In addition to these, HD pathogenesis is likely to involve impairment in intracellular transport, mitochondrial function and synaptic transmission. As our understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms that contribute to HD improves, existing therapeutic targets will become better defined and new targets will be uncovered. The resources to take therapeutics for HD into the clinic are in place and the next decade may see the development of the first effective treatments for HD.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to our colleagues whose work could not be cited, or was cited indirectly, due to space limitations. We thank members of the Neurogenetics Laboratory for advice and comments on the manuscript.

References

- Bates G (2003) Huntingtin aggregation and toxicity in Huntington's disease. Lancet 361: 1642–1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates GP, Murphy KP (2002) in Huntington's Disease (eds Bates GP, Harper PS, Jones AL) 387–426. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Bates GP, Harper PS, Jones AL (eds) (2002) Huntington's Disease. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bence NF, Sampat RM, Kopito RR (2001) Impairment of the ubiquitin–proteasome system by protein aggregation. Science 292: 1552–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonini NM (2002) Chaperoning brain degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99 (Suppl 4): 16407–16411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutell JM, Thomas P, Neal JW, Weston VJ, Duce J, Harper PS, Jones AL (1999) Aberrant interactions of transcriptional repressor proteins with the Huntington's disease gene product, huntingtin. Hum Mol Genet 8: 1647–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha JH (2000) Transcriptional dysregulation in Huntington's disease. Trends Neurosci 23: 387–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A, Brundin P (2003) The ubiquitin proteasome system in neurodegenerative diseases: sometimes the chicken, sometimes the egg. Neuron 40: 427–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunah AW, Jeong H, Griffin A, Kim YM, Standaert DG, Hersch SM, Maradian MM, Young AB, Tanese N, Krainc D (2002) Sp1 and TAFII130 transcriptional activity disrupted in early Huntington's disease. Science 296: 2238–2243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink AL (1999) Chaperone-mediated protein folding. Physiol Rev 79: 425–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass M, Dragunow M, Faull RL (2000) The pattern of neurodegeneration in Huntington's disease: a comparative study of cannabinoid, dopamine, adenosine and GABA(A) receptor alterations in the human basal ganglia in Huntington's disease. Neuroscience 97: 505–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harjes P, Wanker EE (2003) The hunt for huntingtin function: interaction partners tell many different stories. Trends Biochem Sci 28: 425–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU, Hayer-Hartl M (2002) Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: from nascent chain to folded protein. Science 295: 1852–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DG, Sathasivam K, Tobaben S, Stahl B, Marber M, Mestril R, Mahel A, Smith DL, Woodman B, Bates GP (2004) Progressive decrease in chaperone protein levels in a mouse model of Huntington's disease and induction of stress proteins as a therapeutic approach. Hum Mol Genet 13: 1389–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbert S et al. (2001) The Gln-Ala repeat transcriptional activator CA150 interacts with huntingtin: neuropathologic and genetic evidence for a role in Huntington's disease pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 1811–1816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SH, Li XJ (2004) Huntingtin-protein interactions and the pathogenesis of Huntington's disease. Trends Genet 20: 146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantamadiotis T et al. (2002) Disruption of CREB function in brain leads to neurodegeneration. Nat Genet 31: 47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchowski PJ, Schaffar G, Sittler A, Wanker EE, Hayer-Hartl MK, Hartl FU (2000) Hsp70 and hsp40 chaperones can inhibit self-assembly of polyglutamine proteins into amyloid-like fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 7841–7846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollen EA, Garcia SM, van Haaften G, Kim S, Chavez A, Morimoto RI, Plasterk RH (2004) Genome-wide RNA interference screen identifies previously undescribed regulators of polyglutamine aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 6403–6408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrietan K, Hoyt KR (2004) CRE-mediated transcription is increased in Huntington's disease transgenic mice. J Neurosci 24: 791–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B et al. (2004) Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat Genet 36: 585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigamonti D et al. (2000) Wild-type huntingtin protects from apoptosis upstream of caspase-3. J Neurosci 20: 3705–3713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakahira H, Breuer P, Hayer-Hartl MK, Hartl FU (2002) Molecular chaperones as modulators of polyglutamine protein aggregation and toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99 (Suppl 4): 16412–16418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimohata T et al. (2000) Expanded polyglutamine stretches interact with TAFII130, interfering with CREB-dependent transcription. Nat Genet 26: 29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevanin G et al. (2003) Huntington's disease-like phenotype due to trinucleotide repeat expansions in the TBP and JPH3 genes. Brain 126: 1599–1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugars KL, Rubinsztein DC (2003) Transcriptional abnormalities in Huntington disease. Trends Genet 19: 233–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JP, Hardy J, Fischbeck KH (2002) Toxic proteins in neurodegenerative disease. Science 296: 1991–1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman P, Wetzel R, Tanaka M, Nukina N, Goldberg AL (2004) Eukaryotic proteasomes cannot digest polyglutamine sequences and release them during degradation of polyglutamine-containing proteins. Mol Cell 14: 95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voges D, Zwickl P, Baumeister W (1999) The 26S proteasome: a molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annu Rev Biochem 68: 1015–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato C et al. (2003) Huntingtin interacts with REST/NRSF to modulate the transcription of NRSE-controlled neuronal genes. Nat Genet 35: 76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]