Influence of decision aids on patient preferences for anticoagulant therapy: a randomized trial (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

Decision aids have been shown to be useful in selected situations to assist patients in making treatment decisions. Important features such as the format of decision aids and their graphic presentation of data on benefits and harms of treatment options have not been well studied.

Methods

In a randomized trial with a 3 × 2 factorial design, we investigated the effects of decision aid format (decision board, decision booklet with audiotape, or interactive computer program) and graphic presentation of data (pie graph or pictogram) on patients' comprehension and choices of 3 treatments for anticoagulation, identified initially as “treatment A” (warfarin), “treatment B” (acetylsalicylic acid) and “treatment C” (no treatment). Patients aged 65 years or older without known atrial fibrillation and not currently taking warfarin were included. The effect of blinding to the treatment name was tested in a before–after comparison. The primary outcome was change in comprehension score, as assessed by the Atrial Fibrillation Information Questionnaire. Secondary outcomes were treatment choice, level of satisfaction with the decision aid, and decisional conflict.

Results

Of 102 eligible patients, 98 completed the study. Comprehension scores (maximum score 10) increased by an absolute mean of 3.1 (p < 0.01) after exposure to the decision aid regardless of the format or graphic presentation. Overall, 96% of the participants felt that the decision aid helped them make their treatment choice. Unblinding of the treatment name resulted in 36% of the participants changing their initial choice (p < 0.001).

Interpretation

The decision aid led to significant improvement in patients' knowledge regardless of the format or graphic representation of data. Revealing the name of the treatment options led to significant shifts in declared treatment preferences.

Warfarin therapy is strongly recommended for the prevention of stroke in moderate-and high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation.1–10 However, it is associated with a risk of major bleeding. The actual rate of serious bleeding in clinical practice varies widely and depends on the patient's risk category and the quality of monitoring of the international normalized ratio.11–14 Studies in clinical settings have shown that warfarin's effectiveness is similar to that measured in randomized trials, but its utilization in clinical practice is lower than expected.15–25 Acetylsalicylic acid is safer than warfarin, but less effective.26

Patient decision aids are designed to supplement clinician counselling on treatment options and outcomes so that patients can make specific, informed decisions about their care.27–30 It has been reported that they can improve knowledge, reduce decisional conflict and stimulate patients to be more active in decision-making.31–33 However, the jury is still out as to their appropriateness for all patients, their cost-effectiveness and their usability in busy clinical practices or when providers disagree with their advice.31–33 In addition, it is unknown whether the features of decision instruments in terms of their format and content may influence patient decisions.33–38

People with atrial fibrillation have been identified as patients who would benefit from a decision aid, since the benefits and harms of the treatment options (including “do nothing”) have an important impact on morbidity and mortality.39,40 Also, patients have expressed antipathy to anticoagulation with warfarin because the name “warfarin” is associated with rat poison. However, the effect of drug name on knowledge or decisions about therapy is unknown.

We conducted a randomized trial to test (a) whether the format of the decision aid (decision board, decision booklet with audiotape, or interactive computer program) and the graphic presentation of outcome probability data (pie chart or pictogram) would influence patients' comprehension of information about benefits and harms of treatment options, and (b) whether the names of the treatments themselves might influence patients' decisions.

Methods

Information on the anticoagulant treatment options for atrial fibrillation included in the decision aids was based on 3 premises: (a) the potential recipients were 65 years of age or older and had one or more risk factors for stroke; (b) the benefits of the treatment options included in the decision aids were taken from a meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials of anticoagulation;2 and (c) the probability of a major bleed from warfarin therapy was set between the bleeding rates determined in the meta-analysis and in nonrandomized trials involving outpatients in anticoagulation clinics.41–43

Identical information was included in each type of decision aid. The information was divided into 3 sections: description of outcomes, treatment choices and probability of outcomes. Outcomes were stroke and major bleeding, each explained in terms of severity and impact. The treatment choices of warfarin, acetylsalicylic acid and no treatment — initially blinded by labels as “treatment A,” “treatment B” and “treatment C” respectively — were described in terms of benefits, harms and impact on lifestyle (e.g., need for monitoring with blood tests with warfarin treatment). Information on the “no treatment” choice was based on data from placebo arms in clinical trials.

All outcomes were characterized as percentages using a 2-year timeline to avoid the need to display fractions. The chance of stroke or major bleeding and the chance of not having either complication were explained as probabilities in the form of pie graphs or pictograms as well as in the text as numbers (e.g., 2 in 100 patients). All descriptions were written at a grade 6 reading level. Reliability and validity of the content were tested beforehand with 8 elderly people who were not part of the subsequent study.

The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of St. Joseph's Healthcare, Hamilton, Ont. Participants were recruited from 4 family practices and a geriatric day clinical program, all in the Hamilton area. Eligible participants were at least 65 years of age, able to read and understand English and cognitively intact.44 Patients were excluded from the study if they had received a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or if they were currently taking warfarin. These eligibility criteria were chosen to select a cohort for which a decision regarding warfarin therapy would be believable but not necessitate a change in their current therapeutic management.

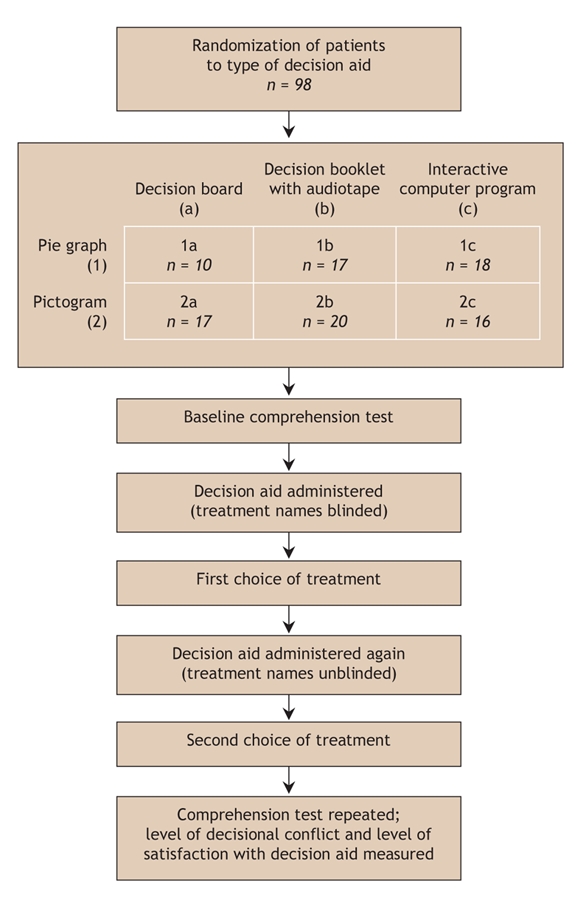

We used a 3 × 2 factorial design to investigate the effects of the following factors on patient comprehension: decision aid format (decision board, decision booklet with audiotape, or interactive computer program) and graphic presentation of the probability data for benefits and harms (pie graph or pictogram). Following informed consent, participants were randomly assigned to receive a decision aid in 1 of the 6 combinations of format type and graphic presentation (Fig. 1) with the use of a computer-generated randomization sequence. The research assistant conducting the patient interviews was informed of the patient's allocation immediately before the interview.

Fig. 1: Study design. Treatment names appeared as “treatment A,” “treatment B” and “treatment C” when blinded in the first administration of the decision aid, and as “warfarin,” “ASA” (acetylsalicylic acid) and “no treatment” when unblinded in the second administration.

Participants completed a baseline Atrial Fibrillation Information Questionnaire before receiving the decision aid. This short (10-item) questionnaire comprises true/ false statements designed to measure participants' comprehension of atrial fibrillation, treatment options and outcomes. The allocated decision aid was then administered with the treatment options blinded (presented as treatments A, B and C), after which participants were asked to make a treatment choice. The decision aid was administered again, exactly as before, but with the treatment names revealed as “warfarin” (treatment A), “ASA” (acetylsalicylic acid, treatment B) and “no treatment” (treatment C). Participants again were asked to make a treatment choice. They were also asked to provide written reasons for their choices (aided by a checklist), to complete the Atrial Fibrillation Information Questionnaire again, to indicate their satisfaction with the decision instrument on a 6-point scale and to complete the Decisional Conflict Questionnaire.31 The Decisional Conflict Questionnaire measures perceptions of personal uncertainty in making a treatment choice, with a lower score indicating more comfort with the decision made; scores higher than 2.5 are associated with decisional conflict.

The primary outcome was the change in comprehension, as assessed by the Atrial Fibrillation Information Questionnaire. Possible scores varied from 0 to 10, with a higher score indicating better knowledge. Secondary outcomes were treatment choices before and after unblinding to treatment name, level of satisfaction with the decision aid, and decisional conflict.

We calculated the sample size on the basis of a 2-factor analysis of variance using the primary outcome measure of change in comprehension scores. A difference in scores of 2 (20% change) between any 2 of the 3 methods of presentation was considered by consensus to be the minimal clinically important difference. Assuming a type I error rate of 5%, a type II error rate of 20%, an effect size of 0.40 and a uniform distribution of the 3 means, we calculated a sample size of 27 subjects per decision instrument group. To allow for a 20% dropout rate, we planned to enrol 100 patients.

We used a 2-factor analysis of variance with Tukey's pairwise comparison to evaluate changes in comprehension scores, patient satisfaction scores and decisional conflict scores according to group allocation. Linear and logistic regression were used to evaluate predictors of scores.

Results

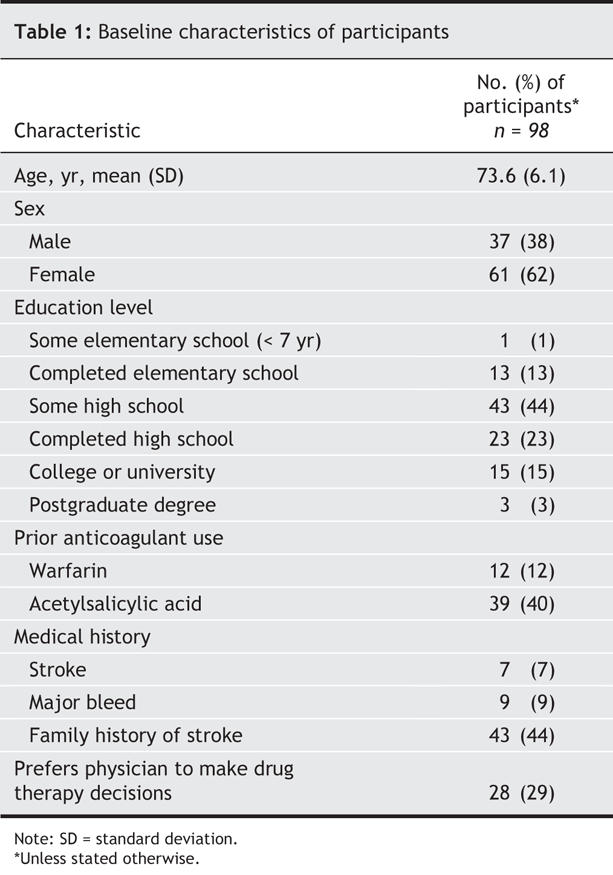

Of the 102 patients included in the study, 4 dropped out before their responses could be collected. Our analysis was based on the responses of the remaining 98 patients. The baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Patients took approximately 60 minutes to complete the questionnaires and the decision aid intervention.

Table 1

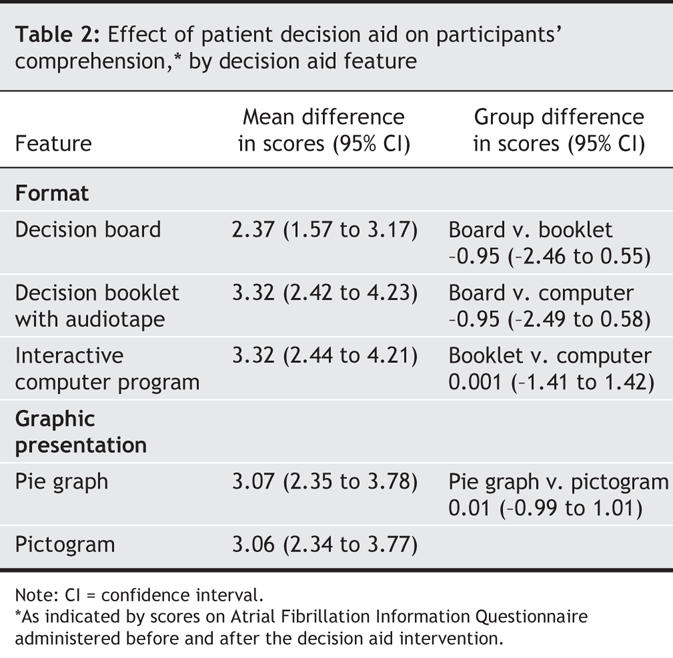

Knowledge of atrial fibrillation improved significantly (p < 0.01) after the decision aid intervention, as indicated by an increase in the mean comprehension score from 4.6 (standard deviation [SD] 2.2) to 7.7 (SD 1.8), regardless of the format or graphic presentation of the decision aid (Table 2). Age, sex, education level and medical history were not significantly associated with the final comprehension scores or with the change in scores.

Table 2

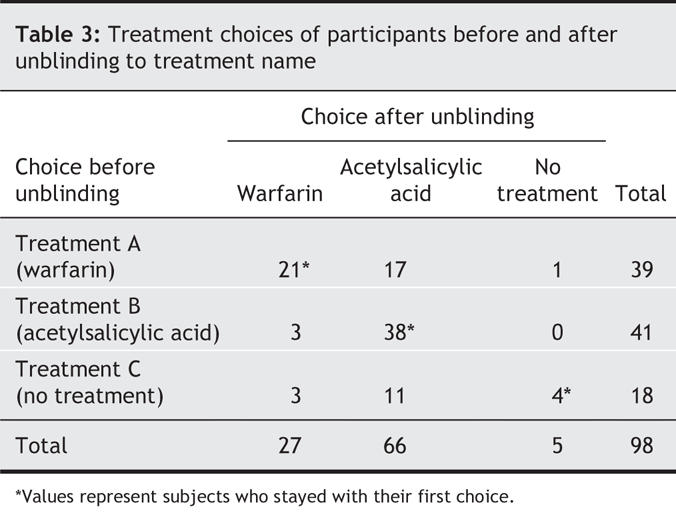

While blinded to the treatment names, 39 participants chose treatment A (warfarin), 41 chose treatment B (acetylsalicylic acid), and 18 selected treatment C (no treatment) (Table 3). When the decision aid was administered again with the treatment names revealed, the number of participants selecting warfarin decreased to 27 (p = 0.023), the number choosing no treatment decreased to 5 (p < 0.001), and the number selecting acetylsalicylic acid increased to 66 (p < 0.001) (Table 3). The unblinding resulted in 36% of the participants changing their initial treatment choice, including 46% of those who initially chose warfarin and 78% of those who initially chose no treatment. Eighty-eight percent of these switches were to acetylsalicylic acid.

Table 3

The top 2 reasons participants gave for choosing warfarin (after unblinding) were knowing someone who had had a stroke and fear of stroke. The main reasons given for choosing acetylsalicylic acid were knowing someone who had had a stroke, avoidance of regular blood tests and fear of stroke. The main reasons for choosing no treatment were avoidance of regular blood tests and unwillingness to add a medication.

The mean total score on the Decisional Conflict Questionnaire was 2.1 (SD 0.4), which suggests reasonable comfort with the treatment decisions. Factors significantly associated with a higher decisional conflict score were low education level (p < 0.001), low comprehension score at baseline (p < 0.001) and change of treatment choice after unblinding to treatment names (p < 0.05). Ninety-six percent of the participants felt that the information in the decision aids helped them make their treatment decision.

Interpretation

Our elderly participants' knowledge of the treatment benefits and harms associated with anticoagulant therapy for atrial fibrillation significantly improved after receiving the decision aid, and they were highly satisfied with the decision tool's ability to help them with their decision. The format of the decision aid did not matter. For example, there was no evidence of aversion to, or difficulty with, the interactive computer program. The decision booklet plus audiotape, which is likely the most feasible and affordable format for most research and clinical groups, performed equally well. Furthermore, the presentation of numerical data was equally effective, whether by pie chart or pictogram, in improving knowledge scores.

The most remarkable finding of this study was the influence that blinding to treatment names had on patients' stated treatment preferences. Despite identical presentations of information, 36% of the overall group changed their choice when the real treatment names were revealed. This reaction to warfarin, otherwise known to the lay public as rat poison, and to the “no treatment” placebo-arm results speaks to the many seemingly irrational influences on treatment behaviours. These influences may well outweigh strictly evidence-based data or detailed numerical benefit:harm analyses, even if the latter are fully understood. This is an important finding, since some of the participants in our study chose a less effective treatment simply because of its name.

Our study has several limitations. First, we included “surrogate” decision-makers — patients who were in the eligible demographic but were not actually facing the treatment decision. This was done to keep the study feasible in terms of acceptability to treating physicians while maximizing generalizability. Another limitation was the short study period, which prevented long-term follow-up of knowledge gains related to the decision instrument. Finally, although the allocation of the decision aids was random, the component of the study that tested whether the treatment names might influence patients' decisions was a before–after comparison.

Our results help explain the often low uptake of warfarin therapy even among patients for whom the benefits clearly outweigh the harms. The generalizability of these results to treatments other than warfarin or placebo or for treatment goals other than stroke prevention is unknown but worthy of exploration. For clinicians, this study illustrates well the importance of allowing patients time to express their preferences and rationale for treatment options at the time of prescribing, so that treatment compliance can be fully optimized.

Conclusion

We have shown that the use of a patient decision aid, regardless of its format or graphic presentation of data on treatment benefits and harms, significantly improved patients' knowledge of atrial fibrillation and anticoagulant treatment options. Despite demonstrating a high level of comprehension, however, many patients changed their treatment decisions simply in response to learning the true name of the treatment arm.

@ See related article page 1597

Acknowledgments

Anne Holbrook is a recipient of a Career Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Renée Labiris is a recipient of a Father Sean O'Sullivan Research Centre Career Award.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Anne Holbrook led the conception and design of the study, supervised the acquisition and analysis of data and wrote the paper. Renée Labiris assisted with all phases except the data analysis, which she led. Charles Goldsmith assisted with all phases and was instrumental in providing statistical advice regarding the study design and data analysis. Kaede Ota and Sandra Harb were students who assisted with all phases of the study. Rolf Sebaldt assisted with the study design, created the computer-based patient-preference interfaces and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All of the authors approved the version submitted for publication.

Funding for the study was provided by the Father Sean O'Sullivan Research Centre, St. Joseph's Healthcare, Hamilton, Ont. The centre was not involved in the design or completion of the study or in the analysis of the data.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Anne Holbrook, Director, Division of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, McMaster University, c/o Centre for Evaluation of Medicines, St. Joseph's Healthcare, 105 Main St. E, Level P1, Hamilton ON L8N 1G6; fax 905 528-7386; holbrook@mcmaster.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Albers GW, Dalen JE, Laupacis A, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Chest 2001;119(1 Suppl):194S-206S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:1449-57. [PubMed]

- 3.Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Preliminary report of the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study. N Engl J Med 1990;322:863-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Peterson P, Gunrun B, Godtfredson J. Warfarin therapy and stroke prevention in patients with nonvaluvular atrial fibrillation. Geriatr Med Today 1990;8:61-73.

- 5.Petersen P, Boysen G, Godtfredsen J, et al. Placebo-controlled, randomised trial of warfarin and aspirin for prevention of thromboembolic complications in chronic atrial fibrillation. The Copenhagen AFASAK study. Lancet 1989;1:175-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study. Final results. Circulation 1991;84:527-39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Boston Area Anticoagulation Trial for Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. The effect of low-dose warfarin on the risk of stroke in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1505-11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Connolly SJ, Laupacis A, Gent M, et al. Canadian Atrial Fibrillation Anticoagulation (CAFA) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;18:349-55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ezekowitz MD, Bridgers SL, James KE, et al. Warfarin in the prevention of stroke associated with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1406-12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hart R, Benavent O, McBride R, et al. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:492-501. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Beyth RJ, Quinn LM, Landefeld CS. Prospective evaluation of an index for predicting the risk of major bleeding in outpatients treated with warfarin. Am J Med 1998;105:91-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Fihn SD, Callahan CM, Martin DC, et al. The risk for and severity of bleeding complications in elderly patients treated with warfarin. The National Consortium of Anticoagulation Clinics. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:970-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Petty GW, Brown RD Jr, Whisnant JP, et al. Frequency of major complications of aspirin, warfarin, and intravenous heparin for secondary stroke prevention. A population-based study. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:14-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.White RH, Beyth RJ, Zhou H, et al. Major bleeding after hospitalization for deep-venous thrombosis. Am J Med 1999;107:414-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Dow L, Bertagne B. Anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Underuse of warfarin is multifactorial. BMJ 1993;307:1492-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Taylor F, Ramsay M, Voke J, et al. Anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. GPs not prepared for monitoring anticoagulation. BMJ 1993;307:1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.King D, Davies KN. Anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Doctors reluctant despite evidence. BMJ 1993;307:1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Bath PMW, Prased A, Brown MM. Survey of the use of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. BMJ 1993;307:1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Howitt A, Armstrong D. Implementing evidence based medicine in general practice: audit and qualitative study of antithrombotic treatment for atrial fibrillation. BMJ 1999;318:1324-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Clinical Quality Improvement Network (CQIN) Investigators. Thromboembolic prophylaxis in 3575 hospitalized patients with atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 1998;14:695-702. [PubMed]

- 21.Leckey R, Aguilar EG, Phillips SJ. Atrial fibrillation and the use of warfarin in patients admitted to an acute stroke unit. Can J Cardiol 2000;16:481-5. [PubMed]

- 22.Samsa GP, Matchar DB, Goldstein LB, et al. Quality of anticoagulation management among patients with atrial fibrillation: results of a review of medical records from 2 communities. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:967-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Antani MR, Beyth RJ, Covinsky KE, et al. Failure to prescribe warfarin to patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:713-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kellen JC, Russell ML. Physician specialty is associated with differences in warfarin use for atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 1998;14:365-8. [PubMed]

- 25.Bungard TJ, Ghali WA, McAlister FA, et al. Physicians' perceptions of the benefits and risks of warfarin for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. CMAJ 2001;165:301-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. The efficacy of aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from 3 randomized trials. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1237-40. [PubMed]

- 27.Deber RB. Physicians in health care management: 8. The patient–physician partnership: decision making, problem solving and the desire to participate. CMAJ 1994;151:423-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Bungard TJ, Ghali WA, McAlister FA, et al. The relative importance of barriers to the prescription of warfarin for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 2003;19:280-4. [PubMed]

- 29.Ubel PA. Is information always a good thing? Helping patients make “good” decisions. Med Care 2002;40(9 Suppl):V39-44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Barry MJ. Health decision aids to facilitate shared decision making in office practice. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:127-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A, O'Connor AM, et al. Development of a decision aid for atrial fibrillation who are considering antithrombotic therapy. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:723-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Deyo RA. A key medical decision maker: the patient. BMJ 2001;323:466-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.O'Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions [update of Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(3):CD001431]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(2):CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Robinson A, Thomason R. Variability in patient preferences for participating in medical decision making: implication for the use of decision support tools. Qual Health Care 2001;10(Suppl 1):i34-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Légaré F, O'Connor AM, Graham ID, et al. The effect of decision aids on the agreement between women's and physicians' decisional conflict about hormone replacement therapy. Patient Educ Couns 2003;50:211-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Levine MN, Gafni A, Markham B, et al. A bedside decision instrument to elicit a patient's preference concerning adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:53-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Whelan T, Levine M, Willan A, et al. Effect of a decision aid on knowledge and treatment decision making for breast cancer surgery: a randomized trial. JAMA 2004;292:435-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Barry MJ, Cherkin DC, YuChiao D, et al. A randomized trial of a multimedia shared decision-making program for men facing a treatment decision for benign prostatic hyperplas. Dis Manag Clin Outcomes 1997;1:5-14.

- 39.Murray E, Davis H, Tai SS, et al. Randomised controlled trial of an interactive multimedia decision aid on benign prostatic hypertrophy in primary care. BMJ 2001;323:493-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Murray E, Davis H, Tai SS, et al. Randomised controlled trial of an interactive multimedia decision aid on hormone replacement therapy in primary care. BMJ 2001;323:490-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Van der Meer FJ, Rosendaal FR, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Bleeding complications in oral anticoagulant therapy. An analysis of risk factors. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:1557-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Fihn SD, McDonell M, Martin D, et al. Risk factors for complications of chronic anticoagulation. A multicenter study. Warfarin Optimized Outpatient Follow-up Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:511-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Gitter MJ, Jaeger TM, Petterson TM, et al. Bleeding and thromboembolism during anticoagulant therapy: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc 1995;70:725-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-98. [DOI] [PubMed]