Activation-induced Deaminase (AID)-directed Hypermutation in the Immunoglobulin Sμ Region: Implication of AID Involvement in a Common Step of Class Switch Recombination and Somatic Hypermutation (original) (raw)

Abstract

Somatic hypermutation (SHM) and class switch recombination (CSR) cause distinct genetic alterations at different regions of immunoglobulin genes in B lymphocytes: point mutations in variable regions and large deletions in S regions, respectively. Yet both depend on activation-induced deaminase (AID), the function of which in the two reactions has been an enigma. Here we report that B cell stimulation which induces CSR but not SHM, leads to AID-dependent accumulation of SHM-like point mutations in the switch μ region, uncoupled with CSR. These findings strongly suggest that AID itself or a single molecule generated by RNA editing function of AID may mediate a common step of SHM and CSR, which is likely to be involved in DNA cleavage.

Keywords: B lymphocyte, immunoglobulin gene, heavy chain, DNA cleavage, error-prone repair

Introduction

Ig genes in B lymphocytes undergo three types of genetic alterations during their development, i.e., V(D)J recombination, somatic hypermutation (SHM), and class switch recombination (CSR). V(D)J recombination takes place in developing B lymphocyte precursors and its biochemical mechanism is well characterized (1). In contrast, little is known about the molecular mechanisms of SHM and CSR. Both events occur in activated mature B lymphocytes such as germinal center cells, but outcomes of the events are apparently very different. In SHM, mostly point mutations are introduced in Ig variable (V) region genes, giving rise to Ig with high affinity (2). DNA cleavages are shown to be introduced in the V region during SHM (3–6). On the other hand, in CSR, two switch (S) regions located 5′ to heavy-chain constant (CH) region genes are cleaved and a large DNA fragment between the cleavages is excised out from the chromosome to bring in a downstream Ig CH region gene to the proximity of a rearranged V gene (7). In addition, neither SHM nor CSR is prerequisite of the other (8, 9). Therefore, it is striking that a defect of AID, a putative RNA editing enzyme, virtually abolishes both SHM and CSR without affecting germinal center formation (10, 11).

To explain this unexpected finding, we have proposed a model that AID edits a precursor mRNA to synthesize an endonuclease essential for generating DNA cleavages in both SHM and CSR reactions (12). However, it remains to be tested whether AID edits separate pre-mRNAs for CSR and SHM, and thus is involved in different steps in the two genetic events. In the present study we provide the evidence that hypermutation takes place in the unrearranged Ig Sμ region under the condition that induces CSR but not SHM in the V region gene. The results imply that CSR and hypermutation may be mediated, at least in part, by the same molecular machinery.

Materials and Methods

Mice and B Cell Culture.

Wild-type (wt) and AID −/− mice on (CBA × C57BL/6) × C57BL/6 back ground were maintained in our animal facility and used 2–8 mo of age. Spleen B cells were purified by depleting CD43+ cells with the magnetic cell sorting system (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec). The purity checked by B220 staining was 87–95%. Purified B cells were cultured as described (10). After 5–8 d cultivation, live cells were harvested and high molecular weight nuclear DNA was extracted with SDS/proteinase K lysis, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction. In some experiments, switched IgG+ cells were enriched (68–90%) or depleted (1.5–6%) by MACS with combination of biotinylated anti-IgG1 and anti–IgG3 antibodies (BD PharMingen) and Streptavidin Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). IgG1 + and IgG3 + cells constitute the majority of switched population in the culture. Mutation frequencies in each population were determined by sequencing 10,391 and 10,328 bp, respectively, as described in Table I.

Table I.

Induction of Hypermutation in the Sμ Region upon CSR Stimulation

| Mutations in Sμ region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B cells | Stimulation withLPS/IL-4 | 5′ subregion | 3′ subregion[NS allele] | V region |

| wt | − | 2/22,723 (2/48)a | 1/27,071 (1/47)b | 4/13,499 (1/27)e |

| [0/12,718 (0/21)]d | ||||

| + | 6/40,571 (5/87)a | 21/47,191 (17/81)b , c | 11/18,500 (3/37)e | |

| [10/21,111 (8/35)]d | ||||

| AID −/− | − | 0/21,244 (0/45) | 0/26,542 (0/46) | 0/3,500 (0/7) |

| + | 0/27,760 (0/58) | 0/34,036 (0/59)c | 0/5,000 (0/10) |

PCR and Sequencing.

PCR were performed with the primers shown below using Pyrobest DNA polymerase (TaKaRa) that has the 3′ exonuclease activity and high fidelity. After purification, the PCR fragments were digested with EcoRI or SpeI and ligated into pBluescript vector. The ligation mixture was used for transformation and the library was plated without preculturing to avoid amplification of sister clones. No more than 21 clones were sequenced from a single PCR reaction for the Sμ. Clonality of the V region clones were checked by their CDR3 sequences. Nucleotide sequences were determined with ABI PRISM 3100 genetic analyser (PerkinElmer). The Sμ region germline sequence of CBA and C57BL/6 were determined and compared. 6 and 5 bp polymorphic differences were found in the Sμ and JH4 downstream regions of our interest, respectively, and excluded from mutations. Primers used for Sμ PCR are: 5′-GGAATTCATTCCACACAAAGACTCTGGACC-3′; 5′-GGAATTCCAGTCCAGTGTAGGCAGTAGA-3′ (A and D in Fig. 1 A, respectively) with 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min. Primers used for sequencing in addition to common primers for pBluescript are: 5′-GGAATTCGTAAGGAGGGACCCAGGCTAAG-3′; 5′-GGAATTCTTCCAGAATCCCAGGATTGCC-3′ (B and C in Fig. 1 A, respectively). The 3′ subregions of nonswitched alleles were amplified by nested PCR as follows: the first step, 20 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 68°C for 7 min, with the primer A and 3′-AGCCCATGCTAGCTCAGCCTCACATAA-5′ (3′ of the Sμ core); the second step, 15 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 68°C for 80 s, with the B and D primers. For VJ558-JH4 downstream region PCR, primers described (13) were used with 35 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 68°C for 80 s.

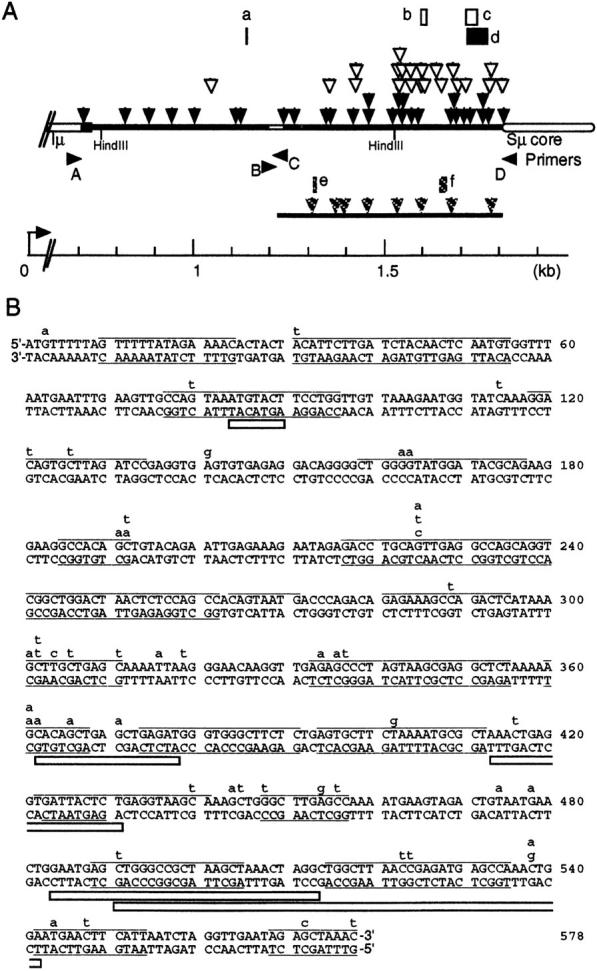

Figure 1.

Distribution of mutations in the Sμ region. (A) A total of 58 point mutations and 6 deletions shown in Table I (closed and hatched symbols) and Table II (open symbols) are mapped by triangles and rectangles, respectively, on the Sμ region (bar). Hatched symbols represent mutations on the non-switched allele. Nucleotide sequences were determined for closed regions. _I_μ exon and the Sμ core region are indicated by thicker bars. Position from the transcription start site (arrow) is indicated by a scale below. Primers A–D were used for PCR or sequencing of the Sμ region. Lengths (bp) of deletions (a–f) are: a, one; b, 17; c, 30; d, 52; e, 7; f, 19. (B) Mutations in the 3′ subregion. The Sμ nucleotide sequence of the C57BL/6 mouse tail DNA is shown by upper case letters. 51 point mutations are indicated in lower case letters. The position of five deletions are shown by open bars. Sequences that are predicted to form S/L structures are underlined (references 12 and 34). Conditions used for the S/L prediction were: the ionic conditions (mM), [Na+] = 150, [Mg2+] = 0.5; the folding temperature, 37°C; the maximum distance between paired bases, 25.

Retrovirus Infection.

Recombinant retrovirus constructs (_pMX-AID-IRES_-GFP) to express AID or AIDm-1, inactive mutant of AID, and preparation and infection of retroviruses were described before (14). GFP+ cells were sorted by FACSVantage™ (Becton Dickinson).

Results and Discussion

We reasoned that CSR target S regions might receive extensive sequence alterations like SHM even without actual CSR upon stimulation of B cells if SHM and CSR share a common mechanism for DNA cleavage. To assess this possibility, we examined DNA sequences of the Sμ region in splenic B lymphocytes stimulated with LPS and IL-4. To avoid PCR artifacts due to highly G rich repetitive sequences in the Sμ core region (15), we chose to analyze the upstream flanking region to the Sμ core sequence (hereafter called the Sμ region), in which practically frequent CSR can take place (16, 17). We also analyzed such Sμ regions that are located on nonswitched alleles, using nested PCR. We found a significant number of mutations accumulating in the Sμ region of spleen B cells stimulated with LPS and IL-4 but not of unstimulated B cells (Table I). The mutations are located mainly in the 3′ subregion of the Sμ region (Fig. 1 A) in agreement with distribution of CSR junctions (17). The mutation frequency observed was 4.5 × 10−4/bp and the fraction of mutated clones reached 21.6% of sequenced clones. These mutations in the Sμ region are independent of CSR because (a) the mutation frequency in Sμ regions on nonswitched alleles is as high as that of total Sμ (Table I), (b) the mutation frequency was not significantly changed between switched and unswitched B cells (4.8 × 10−4/bp and 2.9 × 10−4/bp, respectively; P = 0.58, Fisher's exact test), and (c) no CSR junctions were included in the Sμ region sequenced although frequent mutations are found in the proximity (most often within 10 bp) of CSR junctions (18, 19). Furthermore, no mutations were found in a non-Ig gene, c-myc (total 9,430 bp sequences of 26 clones), excluding the possibility of nonspecific genomewide hypermutation due to DNA damage and repair.

Most importantly, these mutations are not a part of SHM in the V region because LPS and IL-4 stimulation could not induce hypermutation in VJ558-JH4 downstream regions (Table I). The VJ558 family is shown to constitute the major VH population in C57BL mice and VJ558-JH4 downstream regions are known to accumulate mutations in in vivo activated B cells (13). The absence of SHM induction by LPS and IL-4 stimulation in vitro is consistent with the previous reports (20–22). A few heavily mutated clones exist in both before and after the stimulation in wt samples, which are likely due to memory cells. Direct comparison of the mutation rate in the Sμ region to that in the V region is not straightforward because unlike SHM this mutation frequency represents unselected clones in in vitro primary cultures. Nonetheless, the V region of a human B lymphoma cell line, Ramos spontaneously accumulates 2.3 × 10−3/bp mutations during 2 wk (3), the frequency of which is slightly higher than but comparable to the present data. Occasionally we identified small deletions (Fig. 1 A), which is in agreement with previous reports that internal deletions of S (Sμ and Sγ1) regions can occur upon CSR induction (23, 24). These data indicate that CSR stimulation of B cells induces wide spread cleavage in Sμ DNA, which can cause point mutations as well as deletions.

To determine if the hypermutation in the Sμ region also depends on AID, we analyzed spleen B cells from AID −/− mice (10) in parallel with those of wt mice. Strikingly, no mutations were found in both unstimulated and stimulated AID −/− B cells. Altogether the 109.5 kb sequences of the Sμ region were mutation free in AID −/− B cells (Table I). We conclude that the recombination-uncoupled hypermutation in the Sμ region is mediated by the function of AID.

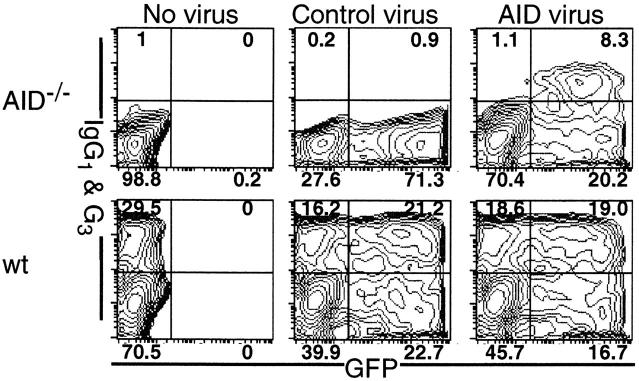

To exclude the possibility that an apparent induction of the hypermutation in the Sμ region represents the outgrowth of the population already with mutations, most likely memory B cells, we transfected AID −/− primary B cells with AID-expressing retroviruses. As AID −/− B cells have no background mutations, population changes in the cell culture would not affect the result. Splenic B cells that had been stimulated with LPS and IL-4 1 d before virus infection were harvested for analysis 5 d after infection. 29% of infected AID −/− cells, which were distinguished by green fluorescent protein (GFP) coexpressed bicistronically with AID, switched to IgG+ whereas only a background level of IgG+ cells was found in uninfected cells (Fig. 2). The switch efficiency of rescued AID −/− cells is comparable to that (29.5%) of wt cells without AID virus infection. By contrast, a control virus carrying a deletion mutant AID (AIDm-1) did not rescue CSR ability of AID −/− cells. Thus, the exogenous AID almost completely rescued CSR ability of AID −/− B cells.

Figure 2.

Rescue of CSR ability in AID_−/_ − B cells by retrovirus-mediated AID transfection. Purified spleen B cells from AID −/− (reference 10) and wt mice were stimulated with LPS (25 μg/ml) and IL-4 (75 μ/ml). On day 1, the culture were split into three, and two of them were infected with either AIDm-1 or AID expressing virus. On day 6, cells were harvested and stained with anti-B220, anti-IgG1, anti-IgG3 (BD PharMingen), and propidium iodide (PI). Data were acquired by FACSCalibur™ and analyzed by CELLQuest™ software (Becton Dickinson). B220+ and PI-negative cells were electronically gated and their IgG and GFP expressions are shown. Percentages of the cells in each quadrant are indicated for each panel.

We then analyzed the sequence of the Sμ region in AID −/− B cells infected with AID virus. Virus-uninfected cells were removed by enrichment of IgG+ cells or GFP+ cells by cell sorting. Clearly, only _AID_-virus transfected cells mutated their Sμ region while AIDm-1-virus infected cells did not (Table II). The mutation frequencies of IgG+ and GFP+ cells were 1.2 × 10−3 and 1.3 × 10−3 per bp, respectively, which are almost the same as the frequency in wt cells infected with AID virus (1.2 × 10−3/bp). Almost all mutations are found in the 3′ subregion in consistence with virus non-infected wt cells (Table I, Fig. 1 A). Again, practically no mutations were observed in VJ558-JH4 downstream regions in AID −/− or wt B cells infected with AID virus (Table II). These results indicate that the mutations of the Sμ region are introduced de novo upon CSR stimulation without SHM in the V region, and absolutely dependent on AID, implicating that both recombination and hypermutation in S regions may be catalyzed by a certain common reaction regulated by AID.

Table II.

Retrovirus-mediated AID Transfection Rescues the Hypermutation Phenotype in AID−/− B Cells

| Mutation in the Sμ region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell/virus | Infected cell(%) | 5′ subregion | 3′ subregion | V region |

| AID−/−/AID | ||||

| IgG enriched | 76 | 1/3,843 (1/8) | 6/4,624 (3/8)a | 1/9,500 (1/19)c |

| GFP+ sorted | 91 | 0/7,954 (0/16) | 11/9,206 (6/16)b | 0/9,500 (0/19) |

| AID−/−/AID m− 1 | ||||

| Total | 72 | 0/3,828 (0/8) | 0/4,624 (0/8)a | 0/12,500 (0/25)c |

| GFP+ sorted | 92 | 0/6,366 (0/13) | 0/7,514 (0/13)b | 0/4,000 (0/8) |

| wt/AID | ||||

| GFP+ sorted | 88 | 0/3,493 (0/7) | 5/4,046 (3/7) | 2/3,500 (1/7) |

If so, the Sμ hypermutation may be biased to stem and loop (S/L) structures as shown for CSR cleavage sites (12, 18, 25). Therefore, we mapped the hypermutation sites to the predicted S/L structures on both strands of the Sμ region, and found significant bias of the mutation to the S/L structures (Table III, Fig. 1 B). Note that the majority of mutations coupled with CSR are located in the proximity (within 10 bp) of the CSR junctions but do not necessarily coincide with cleavage sites (18). This is because mutations are probably introduced during error prone DNA synthesis to repair cleavages. Accordingly, the present level of the coincidence between Sμ mutations and S/L structures well supports the assumption that both CSR and Sμ mutations may be mediated by an enzyme recognizing S/L structures.

Table III.

Mutation Bias to RGYW/WRCY and S/L Structure

| Association with | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGYW/WRCY | Stem and loopa | |||

| + | − | + | − | |

| Mutated sequences | 32b | 19b | 73c | 29c |

| Total sequences | 212 | 366 | 618 | 538 |

Sμ region hypermutation shares important features with V region SHM: AID dependency, high frequency point mutations with occasional deletions, and mutations biased to transition (64%) and to the RGYW/WRCY motif (R, purine; Y, pyrimidine; W, A/T; Table III) (2). It is therefore reasonable to assume that either a similar mechanism activated by AID or AID itself is responsible for hypermutations in the Sμ as well as V region. It has been shown that the defect in the non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) system affects CSR but not SHM (26–29), and that AID −/− mice show no obvious abnormality in the NHEJ system (10), indicating that CSR and SHM differ in the repair mechanism. These results taken together suggest that a common step of CSR and SHM, most likely at DNA cleavage rather than DNA repair, may be regulated by AID. It is well established that CSR and SHM are independent events in B cells (8, 9). In fact, under the present conditions both CSR and hypermutation in S regions occur concurrently without SHM in the V region. There must be another level of regulation to distinguish the targets of the AID-activated system.

As AID deficiency does not affect germline transcription and NHEJ repair, AID is likely to be involved in cleavage of the S region during CSR (10). This conclusion is confirmed by the recent finding that accumulation of γH2AX and Nbs1 at double strand breakages in the IgH locus during CSR is dependent on AID (30). The present finding suggests that CSR and SHM are likely to be mediated by the same enzyme. It is therefore less likely that AID edits separate pre-mRNAs for CSR and SHM. These results taken together argue for, but do not prove, the hypothesis that AID edits a precursor mRNA to synthesize an endonuclease essential for generating DNA cleavage in both SHM and CSR reactions (12). Alternatively, AID itself may have DNA attaching activity although we consider it less likely because (a) AID does not bind to double-stranded or single-stranded Sμ sequences (data not shown) and (b) AID is not associated with the Sμ core region by chromatin immunoprecipitation assay of CSR-induced B cell chromatin (data not shown).

We have further proposed that the endonuclease introduces nicks by recognizing secondary structures such as stem and S/L in S and V regions, which are formed transiently by transcription-promoted strand separation (12). Nicking in the V region will be repaired by exonuclease and error-prone DNA synthesis (31–33), followed by mismatch repair and ligation. By contrast, in S regions frequent nicking generates staggered cleavages (18) which are also repaired by exonuclease and error-prone DNA synthesis, followed by the NHEJ repair system (26–28). Identification of AID target will be able to discriminate these possibilities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. S. Sakakibara and S. Fagarasan for critical reading of the manuscript, Dr. A. Koizumi for advice on statistical analysis, Dr. S.K. Ye for sharing his unpublished information, Ms. M. Nakata for excellent technical assistance, Ms. E. Inoue for cell sorting, and Ms. Nishikawa for the preparation of the manuscript.

Supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (C.O.E.).

References

- 1.Ramsden, D.A., D.C. van Gent, and M. Gellert. 1997. Specificity in V(D)J recombination: new lessons from biochemistry and genetics. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 9:114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuberger, M.S., and C. Milstein. 1995. Somatic hypermutation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 7:248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sale, J.E., and M.S. Neuberger. 1998. TdT-accessible breaks are scattered over the immunoglobulin V domain in a constitutively hypermutating B cell line. Immunity. 9:859–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papavasiliou, F.N., and D.G. Schatz. 2000. Cell-cycle-regulated DNA double-stranded breaks in somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes. Nature. 408:216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kong, Q., and N. Maizels. 2001. DNA breaks in hypermutating immunoglobulin genes: evidence for a break- and -repair pathway of somatic hypermutation. Genetics. 158:369–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bross, L., Y. Fukita, F. McBlane, C. Demolliere, K. Rajewsky, and H. Jacobs. 2000. DNA double-strand breaks in immunoglobulin genes undergoing somatic hypermutation. Immunity. 13:589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honjo, T., K. Kinoshita, and M. Muramatsu. 2002. Molecular mechanism of class switch recombination: linkage with somatic hypermutation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:165–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudikoff, S., M. Pawlita, J. Pumphrey, and M. Heller. 1984. Somatic diversification of immunoglobulins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 81:2162–2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siekevitz, M., C. Kocks, K. Rajewsky, and R. Dildrop. 1987. Analysis of somatic mutation and class switching in naive and memory B cells generating adoptive primary and secondary responses. Cell. 48:757–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muramatsu, M., K. Kinoshita, S. Fagarasan, S. Yamada, Y. Shinkai, and T. Honjo. 2000. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 102:553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Revy, P., T. Muto, Y. Levy, F. Geissmann, A. Plebani, O. Sanal, N. Catalan, M. Forveille, R. Dufourcq-Labelouse, A. Gennery, et al. 2000. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the Hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2). Cell. 102:565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinoshita, K., and T. Honjo. 2001. Linking class-switch recombination with somatic hypermutation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jolly, C.J., N. Klix, and M.S. Neuberger. 1997. Rapid methods for the analysis of immunoglobulin gene hypermutation: application to transgenic and gene targeted mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:1913–1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagarasan, S., K. Kinoshita, M. Muramatsu, K. Ikuta, and T. Honjo. 2001. In situ class switching and differentiation to IgA producing cells in the gut lamina propria. Nature. 413:639–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikaido, T., S. Nakai, and T. Honjo. 1981. Switch region of immunoglobulin Cmu gene is composed of simple tandem repetitive sequences. Nature. 292:845–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, C.G., S. Kondo, and T. Honjo. 1998. Frequent but biased class switch recombination in the S mu flanking regions. Curr. Biol. 8:227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luby, T.M., C.E. Schrader, J. Stavnezer, and E. Selsing. 2001. The mu switch region tandem repeats are important, but not required, for antibody class switch recombination. J. Exp. Med. 193:159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen, X., K. Kinoshita, and T. Honjo. 2001. Variable deletion and duplication at recombination junction ends: Implication for staggered double-strand cleavage in class-switch recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:13860–13865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunnick, W., G.Z. Hertz, L. Scappino, and C. Gritzmacher. 1993. DNA sequences at immunoglobulin switch region recombination sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:365–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McHeyzer-Williams, M.G., G.J. Nossal, and P.A. Lalor. 1991. Molecular characterization of single memory B cells. Nature. 350:502–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manser, T. 1987. Mitogen-driven B cell proliferation and differentiation are not accompanied by hypermutation of immunoglobulin variable region genes. J. Immunol. 139:234–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergthorsdottir, S., A. Gallagher, S. Jainandunsing, D. Cockayne, J. Sutton, T. Leanderson, and D. Gray. 2001. Signals that initiate somatic hypermutation of B cells in vitro. J. Immunol. 166:2228–2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winter, E., U. Krawinkel, and A. Radbruch. 1987. Directed Ig class switch recombination in activated murine B cells. EMBO J. 6:1663–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu, H., Y.R. Zou, and K. Rajewsky. 1993. Independent control of immunoglobulin switch recombination at individual switch regions evidenced through Cre-loxP-mediated gene targeting. Cell. 73:1155–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tashiro, J., K. Kinoshita, and T. Honjo. 2001. Palindromic but not G-rich sequences are targets of class switch recombination. Int. Immunol. 13:495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rolink, A., F. Melchers, and J. Andersson. 1996. The SCID but not the RAG-2 gene product is required for S mu-S epsilon heavy chain class switching. Immunity. 5:319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casellas, R., A. Nussenzweig, R. Wuerffel, R. Pelanda, A. Reichlin, H. Suh, X.F. Qin, E. Besmer, A. Kenter, K. Rajewsky, and M.C. Nussenzweig. 1998. Ku80 is required for immunoglobulin isotype switching. EMBO J. 17:2404–2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manis, J.P., Y. Gu, R. Lansford, E. Sonoda, R. Ferrini, L. Davidson, K. Rajewsky, and F.W. Alt. 1998. Ku70 is required for late B cell development and immunoglobulin heavy chain class switching. J. Exp. Med. 187:2081–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bemark, M., J.E. Sale, H.J. Kim, C. Berek, R.A. Cosgrove, and M.S. Neuberger. 2000. Somatic hypermutation in the absence of DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PK(cs)) or recombination-activating gene (RAG)1 activity. J. Exp. Med. 192:1509–1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen, S., R. Casellas, B. Reina-San-Martin, H.T. Chen, M.J. Difilippantonio, P.C. Wilson, L. Hanitsch, A. Celeste, M. Muramatsu, D.R. Pilch, et al. 2001. AID is required to initiate Nbs1/gamma-H2AX focus formation and mutations at sites of class switching. Nature. 414:660–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogozin, I.B., Y.I. Pavlov, K. Bebenek, T. Matsuda, and T.A. Kunkel. 2001. Somatic mutation hotspots correlate with DNA polymerase eta error spectrum. Nat. Immunol. 2:530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zan, H., A. Komori, Z. Li, A. Cerutti, A. Schaffer, M.F. Flajnik, M. Diaz, and P. Casali. 2001. The translesion DNA polymerase zeta plays a major role in Ig and bcl-6 somatic hypermutation. Immunity. 14:643–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeng, X., D.B. Winter, C. Kasmer, K.H. Kraemer, A.R. Lehmann, and P.J. Gearhart. 2001. DNA polymerase eta is an A-T mutator in somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin variable genes. Nat. Immunol. 2:537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.SantaLucia, J., Jr. 1998. A unified view of polymer, dumbbell, and oligonucleotide DNA nearest-neighbor thermodynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:1460–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]