Deficiency of the Stress Kinase P38α Results in Embryonic Lethality: Characterization of the Kinase Dependence of Stress Responses of Enzyme-Deficient Embryonic Stem Cells (original) (raw)

Abstract

The mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase p38 is a key component of stress response pathways and the target of cytokine-suppressing antiinflammatory drugs (CSAIDs). A genetic approach was employed to inactivate the gene encoding one p38 isoform, p38α. Mice null for the p38α allele die during embryonic development. p38α1/− embryonic stem (ES) cells grown in the presence of high neomycin concentrations demonstrated conversion of the wild-type allele to a targeted allele. p38α−/− ES cells lacked p38α protein and failed to activate MAP kinase–activated protein (MAPKAP) kinase 2 in response to chemical stress inducers. In contrast, p38α1/+ ES cells and primary embryonic fibroblasts responded to stress stimuli and phosphorylated p38α, and activated MAPKAP kinase 2. After in vitro differentiation, both wild-type and p38α−/− ES cells yielded cells that expressed the interleukin 1 receptor (IL-1R). p38α1/+ but not p38α−/− IL-1R–positive cells responded to IL-1 activation to produce IL-6. Comparison of chemical-induced apoptosis processes revealed no significant difference between the p38α1/+ and p38α−/− ES cells. Therefore, these studies demonstrate that p38α is a major upstream activator of MAPKAP kinase 2 and a key component of the IL-1 signaling pathway. However, p38α does not serve an indispensable role in apoptosis.

Keywords: inflammation, cytokines, mitogen-activated protein kinase, signaling, cytokine-suppressing antiinflammatory drug

Introduction

After binding of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1 and TNF-α to their specific receptors on target cells, complex kinase-mediated signaling cascades are initiated that lead to specific changes in transcriptional and translational activities 1 2. Many of these same signaling pathways can be engaged by chemical stress stimuli such as sodium arsenite or anisomycin 3 4, by UV irradiation, 5, and by LPS 6. Several members of the family of mitogen-activated protein (MAP)1 kinases are components of the stress response, including p38 and c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinases 7 8. These MAP kinases regulate activity of key transcription factors including ATF2, Elk, CHOP, MEF2C, and CREB 7 9 10 11 12; this regulation is achieved, in part, by control of downstream kinases such as MAP kinase–activating protein (MAPKAP) kinase 2 and 3 and p38-regulated/activated protein kinase (PRAK; 13 14 15). Stress-activated MAP kinases, therefore, serve as key coordinators and/or regulators of a cell's stress responsiveness.

p38 MAP kinase was first identified as an LPS-inducible activity in murine peritoneal macrophages 6. Like other members of the MAP kinase superfamily, p38 phosphorylates its substrates on serine/threonine residues, and itself requires dual phosphorylation on both a threonine and tyrosine residue for activity 16. Several upstream MAP kinase kinases (MKKs) have been reported to phosphorylate p38 in vitro, including MKK3, MKK4, and MKK6 17 18. Four human p38 isoforms have been identified (α, β, γ, and δ), each containing the conserved dual phosphorylation sequence threonine-glycine-tyrosine 19 20 21 22 23 24 25. The different isoforms display distinct expression patterns 23 26, and data suggesting isoform-specific activities have been reported 27. However, the precise biochemical function that each isoform serves in vivo remains unclear.

Studies aimed at identification of the function of p38 were aided by realization that a novel class of cytokine-suppressing antiinflammatory drugs (CSAIDs) achieved their activity in part via inhibition of this kinase 19. Both the α and β forms of p38 are reported to be CSAID sensitive 19 20 21; in contrast, p38γ and p38δ appear to be insensitive to these agents 23 24 25. Moreover, a panel of 12 other kinases was shown to be insensitive to CSAID inhibition 28, indicating that these agents are selective kinase inhibitors; structural and site-directed mutagenesis studies have recently provided a basis for this selectivity 29 30 31 32. Mechanism of action studies have demonstrated that CSAIDs prevent IL-1β and TNF-α production by LPS-stimulated monocytes and/or macrophages by affecting a posttransciptional process 33 34. In addition, CSAIDs have been shown to inhibit synthesis of a wide variety of IL-1– or TNF-inducible polypeptides, including IL-6 by fibroblasts 35, cyclooxygenase-2 by monocytes 36, and IFN-γ by T cells 37. In these systems, the CSAID effect is manifested, in part, as inhibition of target-gene transcription. Moreover, CSAIDs can suppress nuclear factor (NF)-κB–dependent transcriptional events 38. These agents do not inhibit NF-κB activation per se, but may block activation of accessory factors necessary for NF-κB–dependent transcription. Finally, CSAIDs are reported to alter apoptosis, in some cases promoting 39 and in others inhibiting 40, and to impair posttranslational processing of IL-1β 41. Whether all reported CSAID effects are attributable to p38 inhibition, and to what extent the various p38 isoforms participate in separate biological processes, are important issues that remain to be clarified. Recent studies demonstrating that CSAIDs can also block cyclooxygenase activity 42 and increase Raf-1 activity 43 highlight the potential for CSAID-mediated cellular effects occurring independently of p38.

To better understand the biological function of p38α, a genetic approach was used to inactivate the gene encoding this kinase by homologous recombination in embryonic stem (ES) cells. Inbred DBA/1 lacJ mice that are p38α null die during early embryonic development. However, growth of p38α1/− ES cells in the presence of increased concentrations of neomycin led to isolation of a p38α−/− ES cell line. These enzyme-deficient cells were used to investigate the role of p38α in stress activation pathways. Results derived from this analysis confirm that p38α is a major upstream activator of MAPKAP kinase 2 and an important component of the IL-1 signaling pathway. On the other hand, the results provide no indication that p38α is a necessary component of the chemical-induced apoptotic response mechanism of ES cells. Therefore, these studies help to clarify the role of p38α in stress response pathways.

Materials and Methods

Construction of the p38α Targeting Vector.

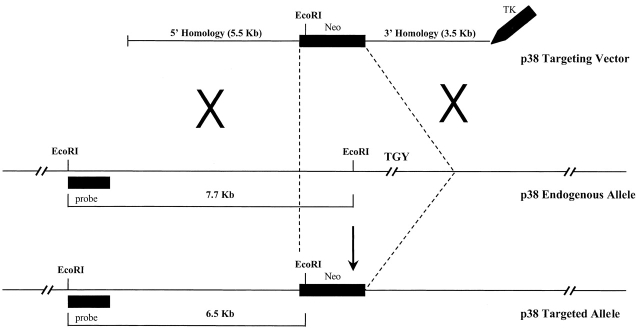

A 759-bp murine p38α partial genomic PCR fragment was used as a probe to identify genomic clones from a DBA/1 lacJ genomic phage library (Stratagene). The p38α targeting vector (Fig. 1) was constructed by cloning 5.5 kb of 5′ homology and 3.5 kb of 3′ homology into a pJNS2 (PGK-NEO/PGK-Tk) backbone vector. The targeting vector replaced ∼8–10 kb of genomic locus, containing the TGY dual phosphorylation site required for kinase activation, with PGK-NEO.

Figure 1.

Scheme employed to achieve homologous recombination of the murine p38α locus. Approximately 8–10 kb of endogenous genomic sequence, including regions necessary for p38α enzymatic activity, was replaced by the neomycin gene; this creates a deletion from phenylalanine 129 to aspartic acid 283 within the native protein. Hybridization of ES cell DNA with an external probe identified a predicted RFLP of 6.5 kb, created as a result of the introduction of a novel EcoRI restriction site in the targeting vector.

Generation of p38α-deficient ES Cells.

DBA/252 ES cells 44 45 were cultured on primary embryonic fibroblasts (PEFs) in DMEM containing high glucose, 15% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 0.2 mM l-glutamine, 0.1 mM 2-ME, 0.1 mM MEM nonessential amino acids, penicillin-streptomycin, and 400 U/ml recombinant murine leukemia inhibitory factor (SCML). The p38α targeting vector (25 μg) was electroporated at 1.0 × 108 ES cells/ml (0.4 ml total volume), and the electroporation was achieved with a BTX Electrocell Manipulator 600 (200 V, 50 μF, 360 Ω). Cells were subsequently subjected to positive/negative selection with 200 μg/ml G418 (geneticin; Life Technologies) and 2 μM gancyclovir (Syntex Laboratories) as described 46. Gene targeting by homologous recombination was determined by Southern analysis using a 5′ 361-bp external PCR probe in conjunction with EcoRI-digested ES cell DNA. As depicted in Fig. 1, the endogenous wild-type allele yielded a band hybridizing at 7.7 kb, whereas the targeted allele revealed a predicted RFLP at 6.5 kb due to the introduction of a novel EcoRI site from the p38α targeting vector. The parental heterozygous p38α ES cell line was subsequently cultured in vitro in SCML supplemented with 2 mg/ml G418, according to published methods, to generate p38α−/− cells 47.

Differentiation of ES Cells.

Cultures of wild-type and p38α−/− ES cells were maintained in the absence of SCML for 16 d to promote formation of embryoid bodies. These structures were dissociated by trypsin digestion to generate single cell suspensions, and the cells were seeded into IMDM containing 4.5 × 10−4 M monothiolglycerol, 15% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 1% methylcellulose, 0.1 ng/ml IL-3, 10 ng/ml IL-6, and 3 ng/ml GM-CSF to promote differentiation to a myeloid-like phenotype. Recombinant murine IL-3, IL-6, and GM-CSF were obtained from Life Technologies. The cultures were maintained for 12 d, then were harvested and stained with PE-labeled anti–murine type 1 IL-1R antibody (PharMingen) or with a control PE-labeled IgG (Caltag). The antibody-stained cells were analyzed by FACS®, and IL-1R–positive cells were collected.

Generation of PEFs.

PEFs were isolated from day 12 DBA/1 lacJ embryos by established methods 48. In contrast, p38α−/− embryos were not viable at 12 d postcoitum. Therefore, to derive p38α−/− PEF cell lines, attempts were made to rescue the early embryonic lethality in chimeric embryos. p38α−/− ES cells were microinjected into day 2.5 C57BL/6 blastocysts, and embryos were recovered at 12 d after transfer to pseudopregnant females. To isolate the p38α−/− PEFs from the pooled chimeric cell population, the primary cell cultures were maintained in the presence of 200 μg/ml G418. The G418 selection killed all C57BL/6 wild-type cells, and the p38α2/− cells survived selection because of the insertion of the neomycin resistance gene in the original targeting vector. However, attempts to expand this p38α−/− PEF population failed within 24 h of passage of original selected cultures.

Reverse Transcription PCR Analysis of p38 Kinase Expression.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed on 1 μg of total ES cell or liver RNA in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 1× PCR buffer (Life Technologies) supplemented with 500 μM each dNTP, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.01 M DTT, and 200 U SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). The RT reaction was carried out for 1 h at 42°C, followed by denaturation at 70°C for 15 min. Aliquots (2 μl) of each RT reaction mixture were then amplified in a 50-μl reaction volume containing 1× PCR buffer, 1.4 mM MgCl2, 200 μM each dNTP, 0.4 μM each primer, and 1 U Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim). PCR cycling conditions were 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. In addition to using liver as a positive tissue control for p38 isoform expression, amplification of the housekeeping gene β-actin was carried out as a positive control for the RT reaction. RT-PCR was also performed on all RNA samples in the absence of the reverse transcriptase to eliminate the possibility that contaminating DNA contributed to the PCR amplification; no transcripts corresponding to the p38 species were detected (data not shown). Primers employed in the RT-PCR analysis consisted of the following: p38α, 5′-GATTCTGGATTTTGGGCTGGCTCG-3′ and 5′-ATCTTCTCCAGTAGGTCGACAGCC-3′; p38β, 5′-ATCCATCGAGGATTTCAGCG-3′ and 5′-CCTCCATGATTCGCTTCAGC-3′; p38δ, 5′-ATTCAGCGAGGATAAGGTCC-3′ and 5′-AGTCACTTTCAGGATCTGGG-3′; p38γ, 5′-ACTTCACAGACTTCTACCTGG-3′ and 5′-CAAAGTATGGATGGGTTAACG-3′; β-actin, 5′-GTGGGCCGCTCTAGGCACCAA-3′ and 5′-CTCTTTGATGTCACGCACGATTTC-3′. To ensure that no other murine genes would cross-hybridize to these specific primer nucleotide sequences, they were prescreened against the BLASTN sequence similarity database (available at newblast@ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). PCR products were size separated by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel, and were visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

IL-6 ELISA.

Wild-type and p38α−/− ES cells and PEFs were cultured overnight in 1 ml SCML containing no effector, human TNF-α (10–20 ng/ml), or human IL-1β (10–20 ng/ml); the recombinant cytokines were obtained from Upstate Biotechnology. Where indicated, the CSAID SB-203,580 (Calbiochem) was added to the culture medium. Media were harvested, clarified by centrifugation, and analyzed in an IL-6 ELISA (Endogen). The assay was performed as instructed by the manufacturer.

Western Blot Analysis.

Cell monolayers (3.5-cm dishes) were washed with PBS, after which 0.1 ml of 2× concentrated Laemmli sample buffer 49 was added, and cells were dislodged by scraping. Cell lysates were transferred to Eppendorf centrifuge tubes and subjected to several bursts of a microtip sonicator to reduce viscosity. These same samples were subsequently boiled for 3 min, and 20 μl of each extract was subjected to SDS-PAGE using 12% Novex minigels. When completed, gels were blotted onto Trans-Blot transfer medium (0.45 μm nitrocellulose; Bio-Rad Laboratories). The resulting blots were blocked by immersion in TBST (10 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20) containing 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were rinsed with TBST, then incubated overnight at 4°C in TBST containing 5% BSA and a 1:1,000 dilution of the appropriate primary antibody. For detection of total and phosphorylated p38, a rabbit polyclonal anti-p38 MAP kinase antibody (New England Biolabs) and a rabbit polyclonal antiphospho-p38 MAP kinase antibody (New England Biolabs) were used. After treatment with the primary antibodies, blots were washed with three changes of TBST, then immersed in TBST containing 5% nonfat dry milk with a 1:2,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG. After a 60-min incubation, blots were washed three times with TBST, then placed in LumiGlo™ (New England Biolabs). Immune complexes were visualized by exposure to X-ray film.

MAPKAP Kinase 2 Assay.

ES cells were seeded (4 × 106 cells) into 6-well cluster dishes and maintained in SCML medium. The growth medium was removed and replaced with 1 ml of medium containing, where indicated, 50 ng/ml anisomycin or 0.5 mM sodium arsenite, and the cultures were incubated for 15 min at 37°C. Monolayers were then rinsed with PBS and treated with 1 ml PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 to promote cell lysis. After a 10-min incubation on ice, extracts were clarified by centrifugation for 20 min at 50,000 rpm in a TLA-100.3 ultracentrifuge rotor (Beckman Instruments). MAPKAP kinase 2 activity within the resulting supernatants was determined using a peptide-based substrate obtained from Upstate Biotechnology. In brief, 5 μg sheep anti–rabbit MAPKAP kinase 2 antibody was incubated with 1 ml of a 5% suspension of protein G–sepharose in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and Complete® protease inhibitor (Boehringer Mannheim). After a 60-min incubation, beads were recovered by centrifugation and washed twice with 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mM sodium glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 ug/ml leupeptin, 1 ug/ml pepstatin, and 50 mM sodium fluoride (buffer A). Individual bead pellets were suspended in 1 ml of the clarified cell extracts, incubated at 4°C for 2 h with gentle rocking, and collected by centrifugation. The beads were washed once with 0.5 ml of buffer A containing 0.5 M sodium chloride, once with 0.5 ml of buffer A, and once with 0.1 ml of 20 mM 4-morpholine propanesulfonic acid, pH 7.2, containing 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 1 mM DTT (kinase buffer). Final bead pellets were suspended in 40 μl of an assay mixture composed of kinase buffer supplemented with 125 μM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 μM MAPKAP kinase 2 substrate peptide, and 250 μCi/ml [γ-32P]ATP (DuPont). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 min, after which 25 μl of each was spotted onto individual p81 phosphocellulose squares (Whatman). These filters were washed with four changes of 0.75% phosphoric acid, once with acetone, then air dried and placed in 4 ml of liquid scintillation fluid for radioactivity determination.

Animal Handling.

All procedures involving mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Pfizer Central Research.

Results

Embryonic Lethality Associated with p38_α_ Deficiency.

Mouse ES cells in which the p38α gene was disrupted by homologous recombination were generated using the scheme shown in Fig. 1. The targeted ES cells successfully contributed to the germline of resulting chimeric mice. F1 generation +/− animals were grossly normal, fertile, and displayed no discernible phenotype. Contrary to expected Mendelian segregation, offspring from the F2 generation demonstrated the +/+ and +/− genotypes at frequencies of 38% (n = 21) and 62% (n = 34), respectively. No p38α−/− animals were obtained, indicating that the p38α-deficient phenotype is an embryonic lethal. We conclude that p38α must serve an essential role in murine development.

Generation of p38α−/− ES Cells.

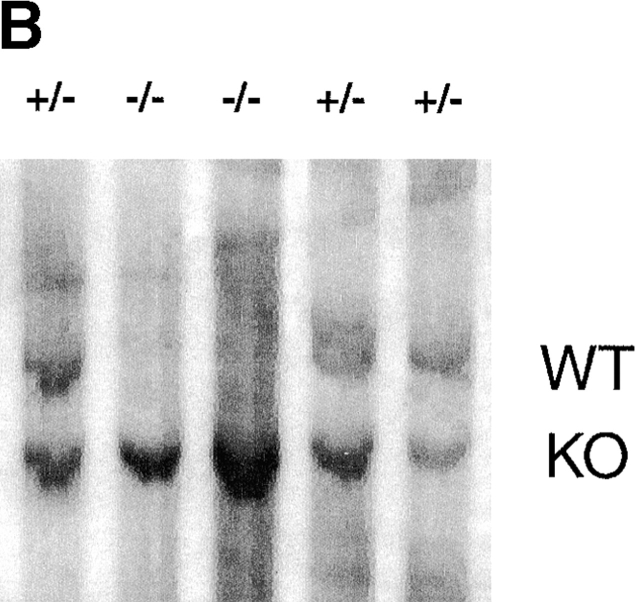

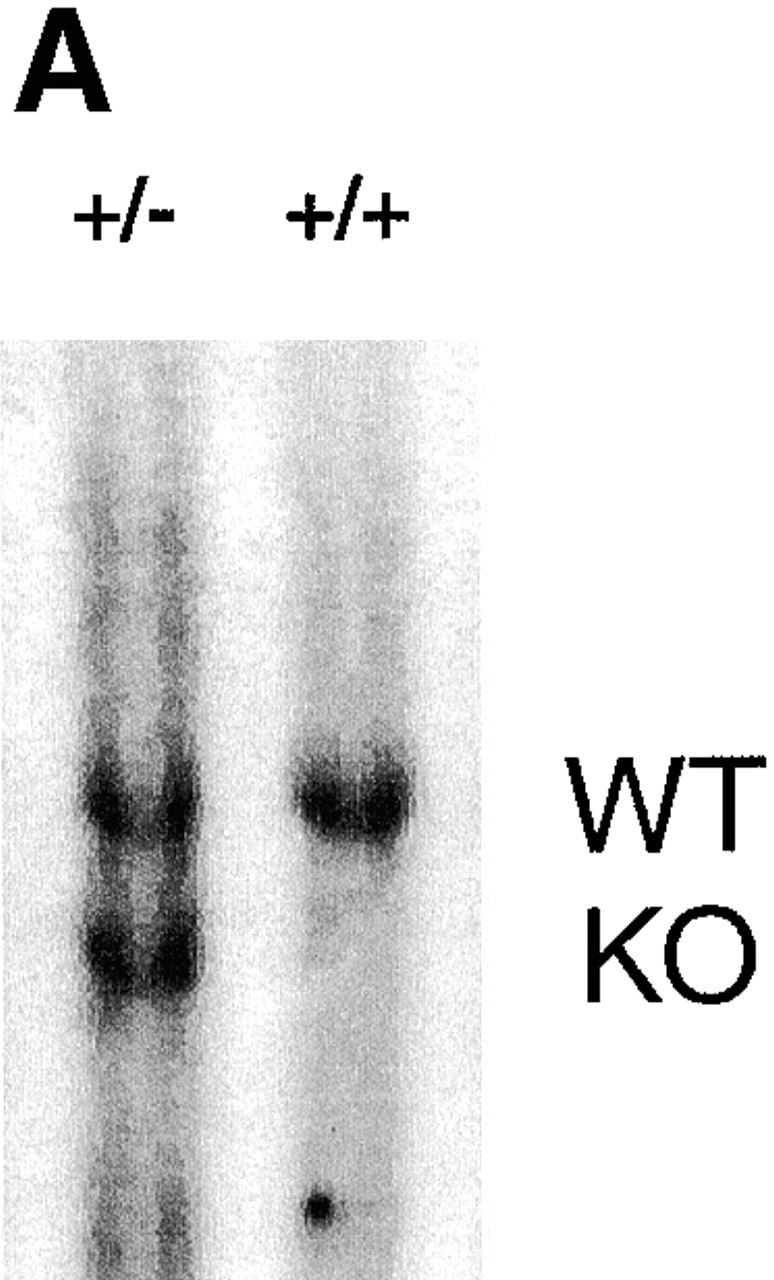

ES cells heterozygous for the p38α MAP kinase locus were subjected to growth in the presence of 2 mg/ml G418 to increase selective pressure for neomycin resistance and convert the wild-type allele to a targeted allele 47. After 23 d of selection, 64 independent clonal isolates were recovered. After Southern blot analysis, 17 (25%) of these clones were shown to be null for the p38α allele (Fig. 2). One of the p38α−/− cell lines was expanded and used in the biochemical analysis described below.

Figure 2.

Southern analysis of ES cell clones. EcoRI restriction enzyme–digested ES cell genomic DNA was electrophoresed, transferred to nitrocellulose, and hybridized to the 5′ external probe of the p38α locus. (A) A blot showing wild-type (+/+) and the parental heterozygous (+/−) ES cell clones. (B) A blot showing examples of G418-surviving ES cell clones; this blot is representative of 64 surviving clones. The positions of the wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) alleles are indicated.

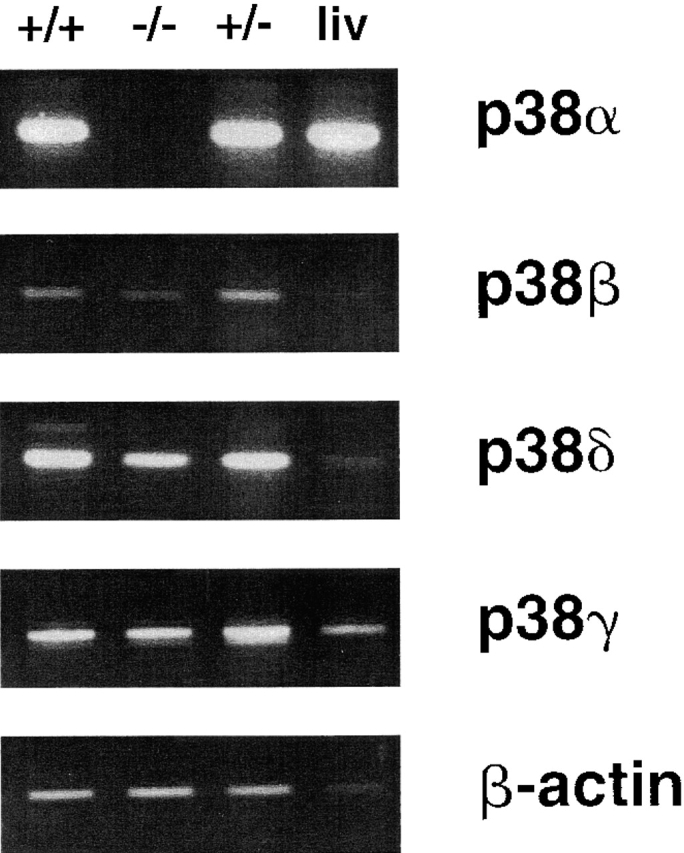

To assess whether ES cells express all known p38 family members, RT-PCR was performed on total RNA prepared from wild-type (+/+) DBA/252 ES cells and from two cell lines that demonstrated either heterozygosity (+/−) or the complete absence (−/−) of the p38α allele by Southern blotting. This analysis indicated that wild-type ES cells express mRNA for p38α, β, γ, and δ (Fig. 3). Likewise, total RNA prepared from liver of an adult DBA wild-type mouse contained transcripts encoding each of the four p38 kinases, although the β species appeared to be in low abundance (Fig. 3). In contrast, total RNA isolated from p38α−/− ES cells showed no evidence of the p38α transcript, but these cells maintained expression of p38β, γ, and δ (Fig. 3). p38α1/− ES cells, on the other hand, yielded RNA transcripts corresponding to each of the four p38 kinases. Within the limits of the RT-PCR approach, no obvious change in the relative expression levels of the p38β, γ, and δ species was observed between the +/+ and −/− ES cell lines.

Figure 3.

Expression of the four murine p38 isoforms and β-actin in wild-type (+/+) ES cells, wild-type liver (liv), p38α-deficient (−/−) ES cells, and p38α heterozygous (+/−) ES cells. The observed RT-PCR product sizes agreed with the predicted values and are as follows: p38α, 368 bp; p38β, 430 bp; p38δ, 354 bp; p38γ, 632 bp; and β-actin, 540 bp.

Comparison of the IL-1 Responsiveness of PEF and ES Cells.

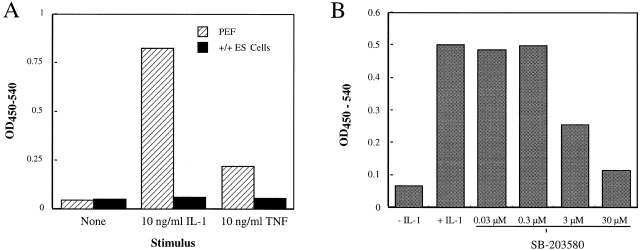

Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 can promote IL-6 production by cell types that express the appropriate signaling receptors 35 36. To determine whether inflammatory cytokine signaling cascades were operative in PEF and ES cells, individual cultures were treated with IL-1 or TNF-α, after which IL-6 released into the medium was determined by ELISA. In the absence of a cytokine effector, PEFs isolated from wild-type embryos produced minimal quantities of IL-6 (Fig. 4 A). However, in response to IL-1 stimulation, these fibroblasts generated large quantities of extracellular IL-6 (Fig. 4 A). Likewise, PEFs responded to TNF-α and generated IL-6, but cytokine levels produced in response to TNF-α were less than those elicited by an equivalent concentration of IL-1 (Fig. 4 A). Attempts to isolate p38α−/− PEFs from day 12 chimeric embryos were unsuccessful; fibroblast-like cells were recovered after G418 selection, but these did not survive during culture. Unstimulated ES cells did not produce IL-6, and addition of IL-1 or TNF-α to their medium did not result in an increase in IL-6 production (Fig. 4 A). This lack of responsiveness suggests that DBA/1 lacJ ES cells lack signaling receptors for IL-1 and TNF, as has previously been noted for ES cells derived from other mice strains 50.

Figure 4.

PEFs, but not ES cells, produce IL-6 in response to inflammatory cytokine stimuli. (A) Cultures of PEFs or wild-type ES cells were incubated overnight in medium containing no effector (None) or 10 ng/ml of IL-1β or TNF-α, after which IL-6 released to the medium was measured by ELISA. The ELISA signal is indicated as a function of treatment (average of duplicate determinations). This experiment was repeated twice with comparable results. (B) PEFs were stimulated overnight with 10 ng/ml of IL-1 in the absence or presence of the indicated concentration of SB-203,580. IL-6 released to the medium was determined by ELISA (average of duplicate determinations). These data are representative of three separate experiments.

IL-1–induced IL-6 production by PEFs appeared to be dependent on p38. Stimulation of these fibroblasts with IL-1 in the presence of the CSAID SB-203,580 inhibited production of IL-6 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4 B); a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 3 μM was estimated for the inhibitory effect (Fig. 4 B).

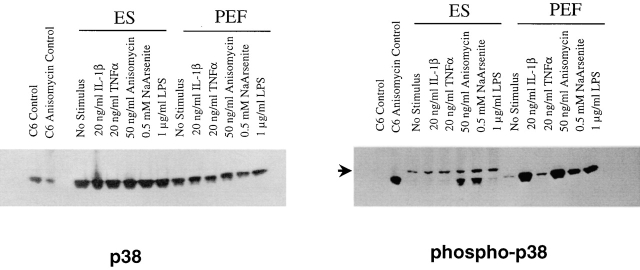

ES Cells and PEFs Respond to Stress Stimuli and Activate p38_α_.

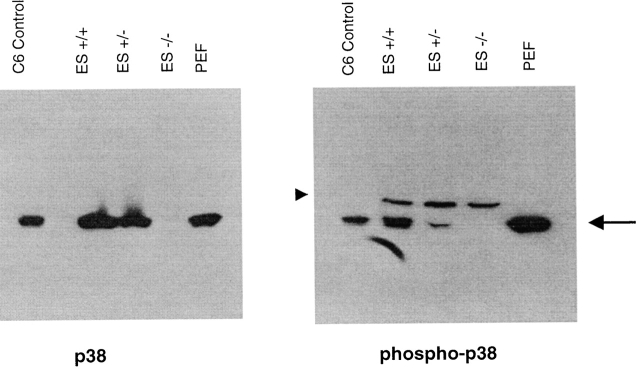

In addition to cytokines, chemical stress stimuli can activate p38 3 4. Therefore, ES cells and PEFs were treated with two agents previously demonstrated to activate p38, anisomycin and sodium arsenite. To assess p38 activation, cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting both for total p38α content and the presence of phosphorylated p38α. The absolute amount of p38α recovered in extracts of ES cells and PEFs did not change in response to the various activation stimuli (Fig. 5). In contrast, quantities of phosphorylated p38α were not equivalent, and were dependent on the activation stimulus (Fig. 5). ES cells that were pretreated with anisomycin (50 ng/ml) or sodium arsenite (0.5 mM) yielded phosphorylated p38α (Fig. 5). On the other hand, stimulation of the ES cells with IL-1 or TNF-α did not promote p38α phosphorylation (Fig. 5); this lack of cytokine responsiveness again suggests that ES cells do not possess the corresponding cytokine receptors. In addition, LPS did not promote phosphorylation of ES cell p38α. Therefore, ES cells possess p38α, and this enzyme can be activated by chemical inducers of stress such as anisomycin and sodium arsenite, but not by inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 or TNF-α) or by LPS.

Figure 5.

Identification of stimuli that promote p38α phosphorylation in PEFs and wild-type ES cells. Cells were stimulated for 15 min in the presence of the indicated effector, and then were solubilized by detergent extraction. Equal quantities of these extracts were fractionated on two separate gels, and the separated polypeptides were transferred to nitrocellulose for Western blot analysis. One blot was treated with an antibody that detects total p38α (p38), and the other with an antibody that detects phosphorylated p38α (phospho-p38). Extracts derived from control and anisomycin-treated C6 cells are included as standards. Identity of the slightly slower migrating antigenic species detected in the ES cell extracts with the phosphospecific antibody (arrow) is unknown.

PEFs also responded to the chemical stress stimuli to generate phosphorylated p38α. Nonstimulated PEFs possessed a low level of phosphorylated p38α, and treatment with either anisomycin or sodium arsenite elevated levels of the phosphorylated enzyme (Fig. 5). Levels of total p38α in the fibroblasts were not affected by the various stimuli (Fig. 5). In addition, PEFs stimulated with IL-1, and to a lesser degree with TNF-α, yielded elevated levels of phosphorylated p38α (Fig. 5); similarly, LPS treatment yielded elevated levels of the phosphorylated enzyme. Therefore, PEFs differ from ES cells in that they generate phosphorylated p38α in response to chemical stress inducers and selective cytokine activators.

p38α-deficient ES cells were subjected to a similar analysis. Extracts derived from anisomycin-treated p38α1/− and p38α1/+ ES cells contained p38α, and this enzyme was phosphorylated in response to the chemical stress inducer (Fig. 6). In contrast, extracts derived from aniosomycin-treated p38α−/− ES cells did not contain p38α or the phosphorylated p38α polypeptide species (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Demonstration that p38α−/− ES cells lack immunodetectable p38α. Wild-type (ES+/+) and p38α-deficient ES cells were stimulated with sodium arsenite for 15 min and then solubilized by detergent extraction. Duplicate samples of each extract were loaded onto separate gels and processed for Western blotting. Antigen detected after staining these blots with an antibody against total (p38) or one selective for phosphospecific (phospho-p38) forms are indicated. Extracts of IL-1–stimulated PEFs and C6 cells are included as standards. Arrow indicates the migration of p38α, and the arrowhead marks the antigen detected by the phospho-specific antiserum in the ES cell samples that is not p38 dependent.

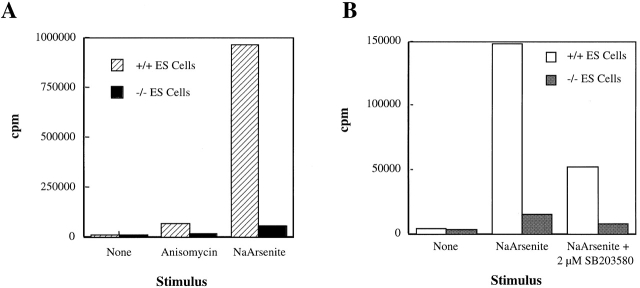

MAPKAP Kinase 2 Activation Is Dependent on p38_α_.

Previous studies established that MAPKAP kinase 2 is a substrate of p38α 4. However, the extent to which other kinases may participate in vivo in the activation of MAPKAP kinase 2 remains unclear. To determine whether stress activation of MAPKAP kinase 2 in ES cells is p38α dependent, +/+ and −/− ES cells were stimulated with anisomycin or sodium arsenite, and cell extracts were isolated. MAPKAP kinase 2 was subsequently recovered by immunoprecipitation, and kinase activity associated with the immunoprecipitates was assessed. In the absence of a stimulus, both p38α1/+ and p38α2/− ES cells yielded low levels of immunoprecipitable MAPKAP kinase 2 activity (Fig. 7 A). Pretreatment with anisomycin or sodium arsenite stimulated MAPKAP kinase 2 activity in extracts derived from p38+/+ ES cells. Sodium arsenite–stimulated cells achieved a greater level of activity than did the anisomycin-treated cells (Fig. 7 A). In contrast to this large increase in MAPKAP kinase 2 activity, p38α−/− cells stimulated with anisomycin or sodium arsenite demonstrated greatly attenuated responses (Fig. 7 A). No significant increase in MAPKAP kinase 2 activity was observed when p38α−/− cells were stimulated with anisomycin, and sodium arsenite treatment yielded only a fourfold increase in activity (Fig. 7 A). Sodium arsenite treatment of p38α1/+ ES cells, on the other hand, yielded >800-fold increase in MAPKAP kinase 2 activity relative to the nonstimulated level (Fig. 7 A).

Figure 7.

MAPKAP kinase 2 activation in wild-type and p38α−/− ES cells. Cultures of p38α1/+ and p38α−/− ES cells were incubated with the indicated effector for 15 min, after which the cells were solubilized by detergent extraction, and MAPKAP kinase 2 was recovered by immunoprecipitation. The resulting immunoprecipitates were then assayed for kinase activity using a peptide substrate and [γ-32P]ATP. Radioactivity (in cpm) incorporated into the peptide substrate is indicated as a function of treatment; a background (no enzyme control) was subtracted to correct for non–peptide-associated radioactivity sticking to the filter. This experiment was repeated twice with comparable results. Each value is the average of duplicate determinations.

Sodium arsenite–induced MAPKAP kinase 2 activation was inhibited by the CSAID SB-203,580. p38α1/+ ES cells treated with sodium arsenite in the presence of 2 μM SB-203,580 yielded 67% less MAPKAP kinase 2 activity than did their counterparts activated in the absence of the CSAID (Fig. 7 B). Likewise, the modest increase in MAPKAP kinase 2 activity observed when p38α−/− ES cells were stimulated with sodium arsenite was inhibited by 63% in the presence of SB-203,580 (Fig. 7 B). Therefore, absence of p38α greatly impaired the ability of stress stimuli to promote MAPKAP kinase 2 activation, but a small CSAID-sensitive component remained in the p38α-deficient cells.

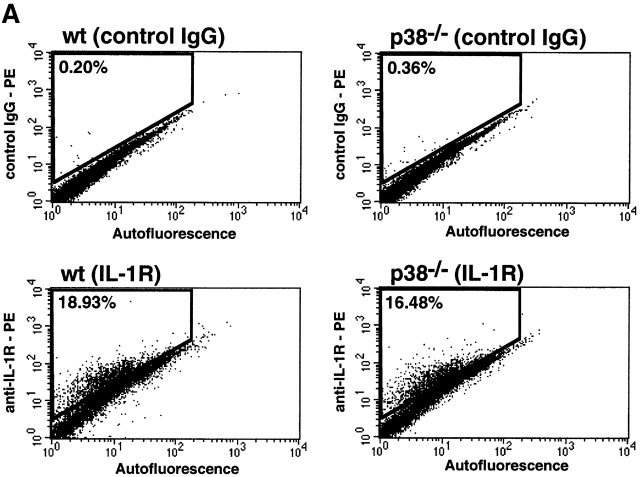

ES Cells Differentiated In Vitro to IL-1R–positive Fibroblast-like Cells Demonstrate an Impaired Response to IL-1 in the Absence of p38α.

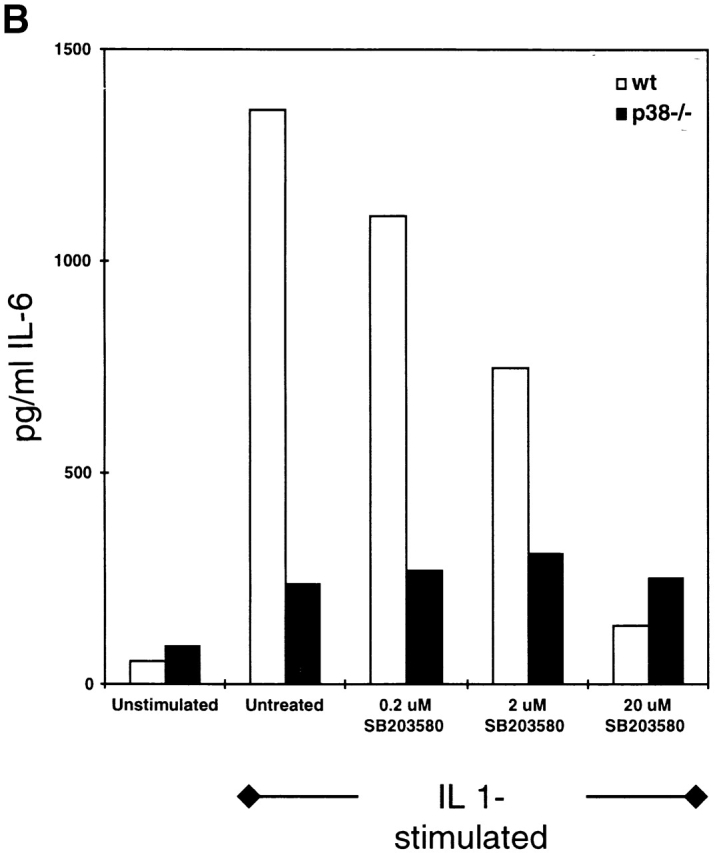

ES cells can undergo differentiation-type processes when maintained under appropriate culture conditions 51. In an attempt to derive cells expressing IL-1R, p38α1/+ and p38α−/− ES cells were allowed to form embryoid bodies. These structures then were dissociated, and the resulting individual cells were cultured for an additional 12 d in the presence of a cytokine mixture composed of IL-3, IL-6, and GM-CSF. The resulting cell populations were separated by FACS® on the basis of binding of murine anti–IL-1R antibodies. The percentage of cells staining positive for IL-1R was comparable in both the p38α1/+ and p38α−/− cultures, representing 19 and 16%, respectively (Fig. 8 A). Staining above a nonimmune IgG control was used as a specificity control. Before the in vitro differentiation process, neither ES cell population stained positive for type 1 IL-1R (data not shown).

Figure 8.

IL-1–induced IL-6 production by in vitro–differentiated ES cells. Wild-type and p38α−/− ES cells were subjected to in vitro differentiation. (A) Cells recovered from each culture were stained with a PE-labeled control IgG or PE-labeled anti–IL-1R IgG, and the cell mixtures were analyzed by FACS®. Cells were gated by autofluorescence, an indicator of size (x-axis), and by PE fluorescence intensity (y-axis). The percentage of cells demonstrating a PE fluorescence intensity above the background level is indicated in each panel. (B) IL-1R–positive cells recovered by sorting were plated into culture wells and stimulated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of SB-203,580. After an overnight stimulation, media were harvested and assayed for IL-6 by ELISA. The amount of IL-6 produced is indicated as a function of treatment. These results are representative of four separate experiments. wt, wild-type.

FACS®-sorted IL-1R–positive cells were cultured in the presence of IL-1. Cytokine stimulation of the IL-1R–positive p38α1/+ cells resulted in expression of IL-6 (Fig. 8 B); in the absence of IL-1, little IL-6 was generated (Fig. 8 B). Coincubation with SB-203,580 during the IL-1 activation period led to a dose-dependent decrease in IL-6 production (Fig. 8 B). The IC50 for this response was estimated to be 2 μM, a value consistent with the IC50 observed in PEFs (Fig. 1). In contrast, cultures of IL-1R–positive p38α−/− cells generated much less IL-6 in response to IL-1 stimulation, and this increase was not reduced by the CSAID (Fig. 8).

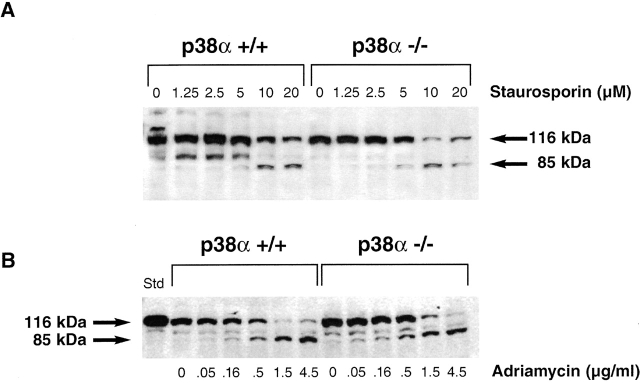

Absence of p38_α_ Does Not Alter ES Cell Apoptosis.

p38α has been implicated as an important regulator of apoptotic processes 52 53, and we considered the possibility that a defect in apoptosis contributed to the embryonic lethality observed with the knockout animals. To assess the apoptotic responsiveness of the p38α1/+ and p38α−/− ES cells, they were initially treated with anti-Fas, a well-characterized inducer of apoptosis 53. However, DBA ES cells failed to bind fluorescently labeled anti-Fas antibody (as detected by FACS®; data not shown), negating use of the Fas-induced apoptotic mechanism. Therefore, chemical stimuli were used to promote apoptosis of p38α1/+ and p38α−/− ES cells. Staurosporin induces apoptosis in many cell systems, and this process is accompanied by caspase-dependent cleavage of the cytoplasmic protein poly(ADP) ribose polymerase (PARP 54). p38α1/+ ES cells treated overnight with increasing concentrations of staurosporin demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in levels of the 85-kD PARP cleavage product as assessed by Western analysis (Fig. 9 A). Extracts prepared from cells treated with concentrations of staurosporin <5 μM did not contain the 85-kD cleavage fragment (Fig. 9 A). At these lower staurosporin concentrations, wild-type cells yielded full-length 116-kD PARP and a slightly faster migrating antigenic species; presence of this latter species was not staurosporin dependent. However, as the concentration of staurosporin was increased to >10 μm, levels of the 85-kD PARP cleavage product increased in the p38+/+ ES cell extracts (Fig. 9 A). Appearance of the PARP cleavage fragment within extracts of p38α−/− ES cells demonstrated a similar dependence on staurosporin concentration (Fig. 9 A). No significant difference in the responsiveness of the two cell types was noted in multiple experiments.

Figure 9.

Deletion of p38α does not inhibit ES cell apoptosis in response to chemical stimuli. p38α1/+ and p38α−/− ES cells were treated with the indicated concentration of staurosporin (A) or adriamycin (B) for 16 h, and then were disaggregated with SDS sample buffer. Samples of the resulting lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with an anti-PARP antibody. Regions of the blots corresponding to full-length 116-kD PARP and its 85-kD cleavage fragment are shown as a function of the effector concentration.

Adriamycin was recently reported to induce caspase-dependent apoptosis of murine ES cells 55, and sensitivity to this agent was also characterized. Extracts prepared from both p38+/+ and p38−/− ES cells yielded the 85-kD PARP cleavage fragment in response to adriamycin treatment (Fig. 9 B), and concentrations of this agent required to generate the cleavage fragment again were similar between the two cell lines (Fig. 9 B).

Apoptosis was also assessed by flow cytometry using the annexin V/propidium iodide staining procedure 56. Adriamycin concentrations between 0.05 and 4.5 μg/ml led to a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability (Table ). Comparison of the sensitivity of p38α1/+ and p38α−/− ES cells revealed a similar concentration dependence in the annexin V/propidium iodide staining profiles (Table ). Moreover, addition of 10 μM SB-203,580 to the culture medium did not significantly alter the percentages of viable cells detected in the adriamycin-treated p38α1/+ and p38α−/− ES cell populations (Table ).

Table 1.

ES Cell Viability after Adriamycin-induced Apoptosis

| Viability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adriamycin | p38α+/+ | p38α+/+ + SB-203,580 | p38α−/− | p38α−/− + SB-203,580 |

| μg/ml | % | % | % | % |

| 0 | 72 | 64 | 68 | 66 |

| 0.05 | 51 | 48 | 43 | 36 |

| 0.16 | 44 | 37 | 30 | 29 |

| 0.50 | 28 | 27 | 22 | 21 |

| 1.50 | 21 | 19 | 17 | 24 |

| 4.50 | 23 | 20 | 17 | 19 |

Discussion

p38 is activated by a variety of extracellular stimuli, including inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF, growth factors such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and CSF, osmolarity changes, UV light, and chemical agents that promote a stress response 7. The diverse nature of these activators suggests that p38 serves as a point of convergence for a variety of extracellular effectors. Based on this multiplicity of activators, it is perhaps not surprising that deletion of p38α led to embryonic lethality. A similar fate has been observed for mice engineered to lack other signaling kinases including MKK4 50 57; function of these signaling kinases must be essential to normal development. Several CSAIDs recently were reported to inhibit FGF-induced proliferation of Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts 58. Perhaps a p38α dependence in a growth factor–induced proliferative response contributes to the lethal phenotype of the p38α−/− embyros, and to our inability to maintain p38α−/− PEFs isolated from chimeric embryos in culture. Since mice, like humans, appear to express multiple p38 kinase family members 59, the developmental arrest suggests that the different enzymes do not perform redundant activities, at least during embryonic development. Deletion of p38α also has been associated with murine embryonic lethality in a 129SvEv × C57BL/6 genetic background, where the arrest was attributed to a defect in placental development 60.

The four human p38 kinases display distinct expression patterns 23 24. By Northern blot analysis, transcripts for 38α, p38β, and p38δ were found in many human tissues, but the relative abundance of an individual species varied widely from tissue to tissue 23. In contrast, p38γ transcripts were abundantly expressed only in skeletal muscle, with minimal expression in most other tissues 23. Not only is expression regulated, but also within the same cell type two forms of the enzyme may demonstrate differential activation requirements. For example, human macrophages express both p38α and p38δ, but p38α was activated to a greater extent than was p38δ after LPS stimulation 26. This differential activation may be achieved through the use of distinct upstream activators 20 61 62. For example, p38α was efficiently activated by MKK3, MKK4, or MKK6 in transfected COS-7 cells, whereas p38β was phosphorylated only by MKK6 20. Finally, forced activation of overexpressed p38α and p38β was reported to promote cardiomyocyte apoptosis and hypertrophy, respectively, suggesting that the individual p38 kinases initiate separate cellular processes 27.

Generation of cells deficient in p38α allowed us to explore this enzyme's role in several stress response pathways. Chemical agents such as anisomycin and sodium arsenite promote activation of p38 in a variety of cell types 3 4. Indeed, p38α1/+ ES cells and PEFs treated with these agents demonstrated increased phosphorylation of p38α and an increased level of MAPKAP kinase 2 activity. In contrast, p38α-deficient ES cells failed to efficiently activate MAPKAP kinase 2 in response to anisomycin or sodium arsenite exposure. Therefore, p38α appears to be a critical component of the MAPKAP kinase 2 activation cascade in response to chemical stress inducers. Interestingly, a small increase in MAPKAP kinase 2 activity persisted after sodium arsenite treatment of p38α−/− ES cells and, as in wild-type ES cells, this increase was blocked by SB-203,580. The magnitude of the CSAID effect against the residual activity was similar to that observed in wild-type cells. Since human p38β, in contrast to the γ and δ isoforms, is CSAID sensitive 20 21 23 24 25, perhaps the mouse equivalent is responsible for the attenuated response.

Mouse PEFs treated with IL-1, and to a lesser degree with TNF-α, responded by phosphorylating p38α and producing and/or secreting IL-6. Fibroblast IL-6 production was inhibited by SB-203,580. ES cells, on the other hand, lacked receptors for IL-1 and TNF-α; IL-1 (or TNF) failed to promote p38α phosphorylation and to stimulate IL-6 production. However, after wild-type ES cells were subjected to an in vitro differentiation process, a percentage of the population expressed the type 1 IL-1R. These receptor-positive cells responded to IL-1 and generated IL-6 via an SB-203,580–inhibitable process.

p38α−/− ES cells also gave rise to a population of IL-1R–positive cells after the in vitro differentiation process. Based on the percentage of cells that expressed this receptor, no difference in the efficiency of the differentiation response to an IL-1R–positive state was observed between p38α1/+ and p38α−/− cell types. A large number of cytokine and/or growth factor signaling cascades have been reported to involve p38 7; for example, SB-203,580 is reported to inhibit GM-CSF–induced cell proliferation 63. Moreover, p38 has been implicated as an important element in cellular differentiation processes. For example, the terminal differentiation of L8 muscle cells is blocked by SB-203,580 64. Therefore, the similar efficiency at which wild-type and p38α−/− ES cells differentiated to an IL-1R–positive phenotype was somewhat of a surprise. However, the IL-1R–positive p38α−/− cells were greatly impaired in their IL-1 responsiveness as judged by a reduction in IL-6 production relative to wild-type cells.

RT-PCR indicated that wild-type ES cells express all four p38 kinase family members. Knockout of the p38α allele eliminated expression of p38α mRNA without altering expression of the other three kinases. Therefore, the gene-targeting strategy successfully eliminated expression of p38α individually. Despite loss of just one of the four p38 kinases, p38α−/− ES cells, in contrast to their wild-type counterparts, did not respond to anisomycin or sodium arsenite to activate MAPKAP kinase 2, and they did not generate IL-6 in response to IL-1 stimulation after in vitro differentiation. With respect to these activities (and within the context of the ES cell), therefore, p38α does not serve a redundant role to its relatives. The markedly reduced responsiveness of p38α−/− ES cells is surprising based on literature reports indicating that MAPKAP kinase 2 is an in vitro substrate for both p38α and p38β family members 25, and evidence that IL-1 treatment can promote activation of all p38 paralogs 23 25 26 59.

p38 kinases have also been implicated as regulators of apoptosis. For example, activation of p38 is reported to be required for apoptosis of PC-12 cells after nerve growth factor withdrawal 52. Likewise, serum removal from rat-1 fibroblasts led to p38 activation and to apoptosis 40. In contrast, an inhibitor of p38, SB-202,190, is reported to promote apoptosis of Jurkat cells 39; overexpression of p38β, but not p38α, attenuated the SB-202,190 effect, suggesting that the response was isoform dependent. ES cells demonstrated an apoptotic response when treated with the chemical inducers of apoptosis, staurosporin or adriamycin. Two separate indicators of apoptosis, PARP cleavage and annexin V binding, were observed in ES cells treated with the chemical inducers. Importantly, p38α1/+ and p38α−/− ES cells were equally sensitive to the chemical-induced apoptotic response. This suggests that p38α does not play a dominant role in this form of ES cell apoptosis. Moreover, the ES cell apoptotic response was not affected by SB-203,580, suggesting that other CSAID-sensitive proteins also were not involved in the death response.

The ability of CSAIDs to modulate inflammatory cytokine production by monocytes and macrophages highlights p38 as an attractive pharmaceutical target. Human monocytes were recently reported to express both p38α and p38δ, and macrophages derived from in vitro differentiation of blood monocytes continued to express both of these kinases 26. In contrast, p38β and p38γ were not expressed in the monocytes and/or macrophages 26. When macrophages were stimulated with LPS, a large increase in p38α activity was observed, with only a modest activation of p38δ 26. Therefore, from the standpoint of regulating monocyte and/or macrophage inflammatory function, it appears that p38α is the key p38 kinase. The data presented in this report using in vitro–differentiated ES cells clearly support p38α serving as a key mediator of IL-1 signal transduction. IL-1R–positive p38α1/+ cells responded to IL-1 and generated IL-6. In contrast, p38−/− IL-1R–positive cells generated minimal quantities of IL-6. IL-1, therefore, appears similar to LPS in its utilization of p38α to achieve target cell activation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jeff Stock for his assistance in the generation of the knockout construct.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: CSAID, cytokine-suppressing antiinflammatory drug; ES, embryonic stem; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; MAP, mitogen-activated protein; MAPKAP, MAP kinase–activated protein; MKK, MAP kinase kinase; NF, nuclear factor; PARP, poly(ADP) ribose polymerase; PEF, primary embryonic fibroblast; RT, reverse transcription; SCML, recombinant murine leukemia inhibitory factor.

References

- Karin M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades as regulators of stress responses. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1998;851:139–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis J.M., Auruch J. Sounding the alarmprotein kinase cascades activated by stress and inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:24313–24316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig S., Hoffmeyer A., Goebeler M., Kilian K., Hafner H., Neufeld B., Han J., Rap U.R. The stress inducer arsenite activates mitogen-activated protein kinases extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 via a MAPK kinase 6/p38-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:1917–1922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse J., Cohen P., Trigon S., Morange M., Alonso-Liamazares A., Zamanillo D., Hunt T., Nebreda A.R. A novel kinase cascade triggered by stress and heat shock that stimulates MAPKAP kinase-2 and phosphorylation of the small heat shock proteins. Cell. 1994;78:1027–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raingeaud J., Gupta S., Rogers J. S., Dickens M., Han J., Ulevitch R.J., Davis R.J. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and environmental stress cause p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by dual phosphorylation on tyrosine and threonine. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:7420–7426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Lee J.-D., Bibbs L., Ulevitch R.J. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science. 1994;265:808–811. doi: 10.1126/science.7914033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New L., Han J. The p38 MAP kinase pathway and its biological function. Trends Cardiovascular Medicine. 1998;8:220–229. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(98)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis J.M., Banerjee P., Nikolakaki E., Dai T., Rubie E.A., Ahmad M.F., Avruch J., Woodgett J.R. The stress-activated protein kinase subfamily of c-Jun kinases. Nature. 1994;369:156–160. doi: 10.1038/369156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh A.J., Yang S.H., Su M.S., Sharrocks A.D., Davis R.J. Role of p38 and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases in the activation of ternary complex factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:2360–2371. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Ron D. Stress-induced phosphorylation and activation of the transcriptional factor CHOP (GADD153) by p38 MAP kinase. Science. 1996;272:1347–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iordanov M., Bender K., Ade T., Schmid W., Sachsenmaier C., Engel K., Gaestel M., Rahmsdorf H.J., Herrlich P. CREB is activated by UVC through a p38/HOG-1-dependent protein kinase. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1997;16:1009–1022. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Jiang Y., Li Z., Kravchenko V.V., Ulevitch R.J. Activation of the transcription factor MEF2C by the MAP kinase p38 in inflammation. Nature. 1997;386:296–299. doi: 10.1038/386296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokoe D., Campbell D.G., Nakielny S., Hidaka H., Leevers S.J., Marshall C., Cohen P. MAPKAP kinase-2; a novel protein kinase activated by mitogen-activated protein kinase. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1992;11:3985–3994. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05492.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin M.M., Kumar S., McDonnell P.C., Van Horn S., Lee J.C., Livi G.P., Young P.R. Identification of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase-activated protein kinase-3, a novel substrate of CSBP p38 MAP kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:8488–8492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New L., Jiang Y., Zhao M., Liu K., Zhu W., Flood L.J., Kato Y., Parry G.C., Han J. PRAK, a novel protein kinase regulated by the p38 MAP kinase. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1998;17:3372–3384. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb M.H., Goldsmith E.J. How MAP kinases are regulated. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:14843–14846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derijard B., Raingeaud J., Barrett T., Wu I.-H., Han J., Ulevitch R.J., Davis R.J. Independent human MAP kinase signal transduction pathways defined by MEK and MKK isoforms. Science. 1995;267:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.7839144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Lee J.-D., Jiang Y., Li Z., Feng L., Ulevitch R.J. Characterization of the structure and function of a novel MAP kinase kinase (MKK6) J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:2886–2891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.C., Laydon J.T., McDonnell P.C., Gallagher T.F., Kumar S., Green D., McNulty D., Blumenthal M.J., Heys J.R., Landvatter S.W. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739–746. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Chen C., Li Z., Gu W., Gegner J.A., Lin S., Han J. Characterization of the structure and function of a new mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38β) J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:17920–17926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein B., Yang M.X., Young D.B., Janknecht R., Hunter T., Murray B.W., Barbosa M.S. p38-2, a novel mitogen-activated protein kinase with distinct properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:19509–19517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Jiang Y., Ulevitch R.J., Han J. The primary structure of p38γa new member of the p38 group of MAP kinases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;228:334–340. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.S., Diener K., Manthey C.L., Wang S.-W., Rosenzweig B., Bray J., Delaney J., Cole C.N., Chan-Hui P.-Y., Mantlo N. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:23668–23674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Gram H., Zhao M., New L., Gu J., Feng L., Di Padova F., Ulevitch R.J., Han J. Characterization of the structure and function of the fourth member of p38 group mitogen-activated protein kinases, p38d. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30122–30128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., McDonnell P.C., Gum R.J., Hand A.T., Lee J.C., Young P.R. Novel homologues of CSBP/p38 MAP kinaseactivation, substrate specificity and sensitivity to inhibition by pyridinyl imidazoles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;235:533–538. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale K.K., Trollinger D., Rihanek M., Manthey C.L. Differential expression and activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase α, β, γ, δ in inflammatory cell lineages. J. Immunol. 1999;162:4246–4252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Huang S., Sah V.P., Ross J., Jr., Brown J.H., Han J., Chien K.R. Cardiac muscle cell hypertrophy and apoptosis induced by distinct members of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase family. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:2161–2168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenda A., Rouse J., Doza Y.N., Meier R., Cohen P., Gallagher T.F., Young P.R., Lee J.C. SB 203580 is a specific inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:229–233. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00357-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young P.R., McLaughlin M.M., Kumar S., Kassis S., Doyle M.L., McNulty D., Gallagher F.F., Fisher S., McDonnell P.C., Carr S.A. Pyridinyl imidazole inhibitors of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase bind in the ATP site. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:12116–12121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K.P., McCaffrey P.G., Hsiao K., Pazhanisamy S., Galullo V., Bemis G.W., Fitzgibbon M.J., Caron P.R., Murcko M.A., Su M.S. The structural basis for the specificity of pyridinylimidazole inhibitors of p38 MAP kinase. Chem. Biol. 1997;4:423–431. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Canagarajah B.J., Boehm J.C., Kassisa S., Cobb M.H., Young P.R., Abdel-Meguid S., Adams J.L., Goldsmith E.J. Structural basis of inhibitor selectivity in MAP kinases. Structure. 1998;6:1117–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisnock J.-M., Tebben A., Frantz B., O'Neill E.A., Croft G., O'Keefe S.J., Li B., Hacker C., de Laszlo S., Smith A. Molecular basis for p38 protein kinase inhibitor specificity. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16573–16581. doi: 10.1021/bi981591x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.C., Young P.R. Role of CSBP/p38/RK stress response kinase in LPS and cytokine signaling mechanisms. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1996;59:152–157. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perregaux D.G., Dean D., Cronan M., Connelly P., Gabel C.A. Inhibition of interleukin-1b production by SKF86002evidence of two sites of in vitro activity and of a time and system dependence. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48:433–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyaert R., Cuenda A., Vanden Berghe W., Plaisance S., Lee J.C., Haegeman G., Cohen P., Fiers W. The p38/RK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway regulates interleukin-6 synthesis in response to tumor necrosis factor. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1996;15:1914–1923. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouliot M., Baillargeon J., Lee J.C., Cleland L.G., James M.J. Inhibition of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2 expression in stimulated human monocytes by inhibitors of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Immunol. 1997;158:4930–4937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincon M., Enslen H., Raingeaud J., Recht M., Zapton T., Su M.S., Penix L.A., Davis R.J., Flavell R.A. Interferon-gamma expression by Th1 effector T cells mediated by the p38 MAP kinase signaling pathway. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1998;17:2817–2829. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Berghe W., Plaisance S., Boone E., De Bosscher K., Schmitz M.L., Fiers W., Haegeman G. p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways are required for nuclear factor-kB p65 transactivation mediated by tumor necrosis factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:3285–3290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto S., Xiang J., Huang S., Lin A. Induction of apoptosis by SB202190 though inhibition of p38b mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:16415–16420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer J.L., Rao P.K., Heidenreich K.A. Apoptosis induced by withdrawal of trophic factors is mediated by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:20490–20494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J., Kostura M.J. Dissociation of IL-1β synthesis and secretion in human blood monocytes stimulated with bacterial cell wall products. J. Immunol. 1993;151:5574–5585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsch-Haubold A.G., Pasquet S., Watson S.P. Direct inhibition of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 by the kinase inhibitors SB203580 and PD98059. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:28766–28772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmes A., Deou J., Clowes A.W., Daum G. Raf-1 is activated by the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor, SB203580. FEBS Lett. 1999;444:71–74. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach M.L., Stock J.L., Byrum R., Koller B.H., McNeish J.D. A new embryonic stem cell line from DBA/1lacJ mice allows genetic modification in a murine model of human inflammation. Exp. Cell Res. 1995;221:520–525. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths R.J., Smith M.A., Roach M.L., Stock J.L., Stam E.J., Milici A.J., Scampoli D.N., Eskra J.D., Byrum R.S., Koller B.H., McNeish J.D. Collagen-induced arthritis is reduced in 5-lipoxygenase–activating protein–deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:1123–1129. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.6.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour S.L., Thomas K.R., Capecchi M.R. Disruption of the proto-oncogene int-2 in mouse embryo-derived stem cellsa general strategy for targeting mutations to non-selectable genes. Nature. 1988;236:348–352. doi: 10.1038/336348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen R.M., Conner D.A., Chao S., Geisterfer-Lowrance A.A., Seidman J.G. Production of homozygous mutant ES cells with a single targeting construct. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:2391–2395. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan B., Beddington R., Costantini F., Lacy E. Manipulating the Mouse EmbryoA Laboratory Manual 1994. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, ; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: pp. 487 pp [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganiatsas S., Kwee L., Fujiwara Y., Perkins A., Ikeda T., Labow M.A., Zon L.I. SEK1 deficiency reveals mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade crossregulation and leads to abnormal hepatogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:6881–6886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles M.V., Keller G. Multiple hematopoietic linages develop from embryonic stem (ES) cells in culture. Development. 1991;111:259–267. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z., Dickens M., Raingeaud J., Davis R.J., Greenberg M.E. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B., Koppenhoefer U., Weinstock C., Linderkamp O., Lang F., Gulbins E. Fas- or ceramide-induced apoptosis is mediated by a Rac1-regulated activation of Jun N-terminal kinase/p38 kinases and GADD153. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:22173–22181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson M.D., Weil M., Raff M.C. Role of Ced-3/ICE-family proteases in staurosporine-induced programmed cell death. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:1041–1051. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.5.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aladjem M.I., Spike B.T., Rodewald L.W., Hope T.J., Klemm M., Jaenisch R., Wahl G.M. ES cells do not activate p53-dependent stress responses and undergo p53-independent apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermes I., Haanen C., Steffens-Nakken J., Reutelingsperger C. A novel assay for apoptosis flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on early apoptotic cells using fluorescein labelled Annexin V. J. Immunol. Methods. 1995;184:39–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00072-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D., Tournier C., Wysk M., Lu H.-T., Xu J., Davis R.J., Flavell R.A. Targeted disruption of the MKK4 gene causes embryonic death, inhibition of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation, and defects in AP-1 transcriptional activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:3004–3009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher P. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation is required for fibroblast growth factor-2-stimulated cell proliferation but not differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:17491–17498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M.C., Wang Y.P., Mikhail A., Qiu W.R., Tan T.-H. Murine p38-δ mitogen-activated protein kinase, a developmentally regulated protein kinase that is activated by stress and proinflammatory cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7095–7102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudgett, J.S., L. Guh-Siesel, N.A. Chartrain, L. Yang, and M. Shen. 1998. Targeted inactivation of the p38α gene results in midgestation embryonic lethality_._ 9th International Conference of the Inflammation Research Association. P8 (Abstr.)

- Enslen H., Raingeaud J., Davis R.J. Selective activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase isoforms by the MAP kinase kinases MKK3 and MKK6. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:1741–1748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nick J.A., Avdi N.J., Young S.K., Lehman L.A., McDonald P.P., Frasch S.C., Billstrom M.A., Henson P.M., Johnson G.L., Worthen G.S. Selective activation and functional significance of p38a mitogen-activated protein kinase in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated neutrophils. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:851–858. doi: 10.1172/JCI5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch O., Marshall C.J. Cooperation of p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways during granulocyte-stimulated factor-induced hemopoietic cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:4096–4105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zester A., Gredinger E., Bengal E. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway promotes skeletal muscle differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:5193–5200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]