Polyparasitism (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2008 Aug 8.

Published in final edited form as: Int J Epidemiol. 2005 Jan 19;34(1):221–223. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh399

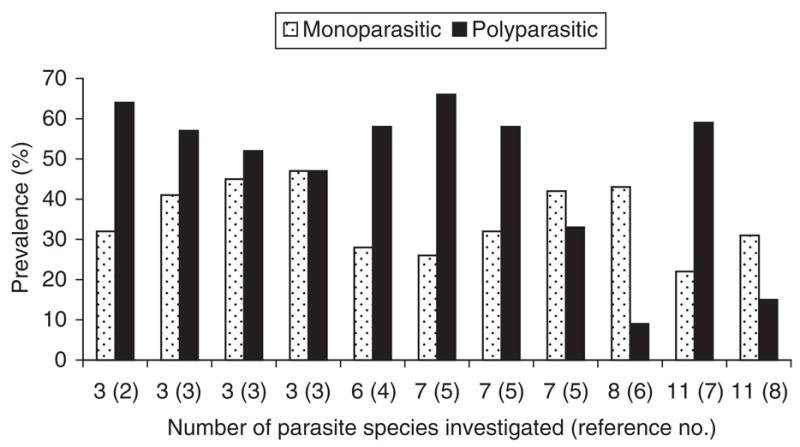

Sirs—The recent Raso et al. paper1 addresses a phenomenon that is important, familiar, but neglected. Explicit studies of polyparasitism should be common: polyparasitism is common in the world, though seldom acknowledged. Figure 1 summarizes seven reports published in 1991–96 that include data on polyparasitism.2–8 At 7 of the 11 study sites, more than half the sample population harboured a polyparasitic infection.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of mono- and polyparasitic infections at 11 sites

Even these sparse results point to deeper questions, e.g. why those seven sites include three of the four at which three parasite species were investigated, but only one of the two at which eleven were investigated. Studies that simply compare the observed with the expected prevalence of a specific polyparasitic infection—or present data that allow others to do so—can provide insights to guide intervention, e.g. for geohelminth infections,9–10 or malaria.11–12 But such studies are still rare.

It may be that only a few parasite species interact, in epidemiological or clinical terms, and that in most circumstances it is wise to focus on one infection and ignore the others. Differential diagnosis has proven an enormously valuable principle, and the postulates Koch developed—after concluding that ‘work with impure cultures yields nothing but nonsense’13—remain the standard for demonstrating a causal relationship between a microbe and a disease. But it was impure cultures—thanks to Fleming’s sloppiness, luck, and sharp eye—that led to penicillin. Wagner-Jauregg’s observation that syphilis patients were sometimes ‘healed through intercurrent infectious diseases,’ led him to ‘imitate this experiment of nature’14—which led to a Nobel Prize, and the treatment of thousands in malariatherapy clinics.15 Certainly Jenner could not have known that he was taking advantage of microbial interactions when he used the virus of cowpox as ‘vaccinia’ to protect against the virus of smallpox. In recent times, analysis of the accelerating co-incidence of familiar STDs might have helped us recognize more promptly that HIV was emerging, facilitating, and exacerbating other infections.16

Polyparasitism is widespread. Its combinatorics and complexity are daunting, but, for parasite species interconnected through immunity or transmission, likely to confound routine approaches to research. Raso et al. remind us that ‘multiple species parasitic infections are the norm rather than the exception,’ and therefore that polyparasitism deserves much more attention.

References

- 1.Raso G, Luginbühl A, Adjoua CA, et al. Multiple parasite infections and their relationship to self-reported morbidity in a community of rural Côte d’Ivoire. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:1092–102. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kightlinger LK, Seed JR, Kightlinger MB. The epidemiology of Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, and hookworm in children in the Ranomafana rainforest, Madagascar. J Parasitol. 1995;81:159–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Booth M, Yuesheng L, Tanner M. Helminth infections, morbidity indicators and schistosomiasis treatment history in three villages, Dongting Lake region, PR China. Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1:464–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1996.d01-93.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashford RW, Craig PS, Oppenheimer SJ. Polyparasitism on the Kenya coast. I Prevalence and association between parasitic infections. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;86:671–79. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1992.11812724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tshikuka J-G, Scott ME, Gray-Donald K, Kalumba O-N. Multiple infection with Plasmodium and helminths in communities of low and relatively high socio-economic status. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1996;90:277–93. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1996.11813053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alonzo E, Alonzo V, Forino D, Iloi A. Recherche parasitologique conduite entre 1982 et 1991 chez un echantillon de sujets residents a Zinvie (Benin) Med Trop. 1993;53:331–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chunge RN, Karumba PN, Nagelkerke N, et al. Intestinal parasites in a rural community in Kenya: cross-sectional surveys with emphasis on prevalence, incidence, duration of infection, and polyparasitism. East Afr Med J. 1991;68:112–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira CS, Ferreira MU, Nogueira MR. The prevalence of infection by intestinal parasites in an urban slum in Sao Paulo, Brazil. J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;97:121–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bundy DA, Cooper ES, Thompson DE, Didier JM, Simmons I. Epidemiology and population dynamics of Ascaris lumbricoides and Trichuris trichiura infection in the same community. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81:987–93. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Booth M, Bundy DA. Comparative prevalences of Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura and hookworm infection and the prospects for combined control. Parasitology. 1992;105:151–57. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000073807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenzie FE, Bossert WH. Mixed-species Plasmodium infections of humans. J Parasitol. 1997;83:593–600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mason DP, McKenzie FE. Blood-stage dynamics and clinical implications of mixed Plasmodium vivax–Plasmodium falciparum infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:367–74. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atlas RM, Bartha R. Microbial Ecology. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner-Jauregg J. The treatment of general paresis by inoculation of malaria. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1922;55:369–75. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chernin E. The malariatherapy of neurosyphilis. J Parasitol. 1984;70:611–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petridou E, Dafni U, Freeman J, Trichopoulos D. Routinely reported sexually transmitted diseases presage the evolution of the AIDS epidemic. Epidemiology. 1997;8:449–52. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199707000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]