Notch and Kras reprogram pancreatic acinar cells to ductal intraepithelial neoplasia (original) (raw)

Abstract

Efforts to model pancreatic cancer in mice have focused on mimicking genetic changes found in the human disease, particularly the activating KRAS mutations that occur in pancreatic tumors and their putative precursors, pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN). Although activated mouse Kras mutations induce PanIN lesions similar to those of human, only a small minority of cells that express mutant Kras go on to form PanINs. The basis for this selective response is unknown, and it is similarly unknown what cell types in the mature pancreas actually contribute to PanINs. One clue comes from the fact that PanINs, unlike most cells in the adult pancreas, exhibit active Notch signaling. We hypothesize that Notch, which inhibits differentiation in the embryonic pancreas, contributes to PanIN formation by abrogating the normal differentiation program of tumor-initiating cells. Through conditional expression in the mouse pancreas, we find dramatic synergy between activated Notch and Kras in inducing PanIN formation. Furthermore, we find that Kras activation in mature acinar cells induces PanIN lesions identical to those seen upon ubiquitous Kras activation, and that Notch promotes both initiation and dysplastic progression of these acinar-derived PanINs, albeit short of invasive adenocarcinoma. At the cellular level, Notch/Kras coactivation promotes rapid reprogramming of acinar cells to a duct-like phenotype, providing an explanation for how a characteristically ductal tumor can arise from nonductal acinar cells.

Keywords: cancer, pancreas, Ras, PanlN, metaplasia

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States, proving fatal to nearly all who are diagnosed (1). PDA is thought to arise from ductal precursor lesions termed pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), which accumulate mutations and become progressively dysplastic, finally forming metastatic tumors. Activation of the KRAS proto-oncogene, which is seen in almost all PDA cases, occurs in many early PanINs and may represent an initiating event (1).

PDA has been modeled in mouse by use of a Cre-dependent activated Kras allele, KrasloxP-STOP-loxP-G12D (henceforth, KrasG12D), which induces mouse PanIN lesions (mPanINs) similar to those seen in humans (2–4). Interestingly, although previous studies used Pdx1Cre or Ptf1aCre drivers to activate KrasG12D throughout the pancreas, mPanINs formed only focally, and most of the organ appeared normal (2, 3). This suggests that only a subset of cells in the pancreas can be transformed by activated Kras, although the basis of this specificity remains unknown. Additional signaling pathways that may promote Kras-mediated transformation are active in human and mouse PanINs, including the Notch pathway (1, 2). Notch is of particular interest given its importance to embryonic pancreas development (5), and its involvement in phenotypic plasticity of adult exocrine cells (6, 7). In turn, exocrine cell plasticity is likely relevant to the long-standing question of where pancreatic cancer originates.

Under certain circumstances, including exposure to the EGF receptor ligand TGF-α, acinar cells can assume duct-like characteristics (6, 8, 9). Importantly, TGF-α-induced acinar-to-duct conversion requires Notch activity (6). Ras proteins are downstream effectors of the EGF receptor, and overexpressing activated Kras in acinar cells also causes ductal metaplasia and tumors of mixed acinar/ductal character (10, 11). Overexpression of activated Kras in duct cells, by contrast, does not produce PanINs or other dysplastic lesions (12). Conversion of acinar cells to a duct-like phenotype may therefore be an important first step in pancreatic tumorigenesis.

This hypothesis receives support from several recent studies, using Cre-dependent endogenous KrasG12D or KrasG12V alleles. First, mPanIN formation in young KrasG12D;Ptf1aCre mice is associated with acinar-ductal metaplasia, and similar metaplastic lesions can be found associated with human PanINs (13). Second, activation of KrasG12D specifically in acinar precursors, by using NestinCre, produces mPanINs identical to those seen with Pdx1Cre and Ptf1aCre (14). Finally, and most critically, activation of KrasG12V in adult acinar and centroacinar cells (CACs) leads to acinar-ductal metaplasia and mPanIN formation after experimentally induced pancreatitis (15). Experimental pancreatitis activates the Notch pathway (7, 16, 17), and this pathway also appears to be activated during metaplasia induced by KrasG12V (15). As this study involved activation in both acini and CACs, however, it remains unclear which cell type is the actual mPanIN cell of origin. Furthermore, although Notch promotes acinar-ductal metaplasia in vitro, its contribution to pancreatic cancer initiation remains unknown.

Here, we test the hypothesis that Notch activation confers sensitivity to KrasG12D, and that this cooperative interaction drives conversion of acinar cells to preinvasive PanIN lesions. We find that coactivation of Notch and Kras, by using a relatively nonspecific Pdx1CreERT driver, dramatically increases mPanIN formation compared with Kras activation alone. Furthermore, we find that fully differentiated adult acinar cells are able to form mPanIN lesions after KrasG12D activation, and that coactivation of Notch accelerates this process. Notch and Kras coactivation causes rapid reprogramming of acinar cells to a duct-like phenotype, suggesting an explanation for how precursors of a ductal cancer can originate from nonductal differentiated cells.

Results

Notch Promotes Kras-Induced mPanIN Formation.

To determine whether Kras and Notch cooperate to induce mPanIN formation, we crossed a Cre-dependent Notch1 gain-of-function transgene, _Rosa26Notch1IC-IRES-_GFP (18) (henceforth, Rosa26NIC), into the KrasG12D background. To avoid lethality caused by the absence of islet differentiation in Rosa26NIC;Pdx1Cre mice (18), we used a tamoxifen-inducible Pdx1CreERT transgene to generate mosaic pancreata (19). On tamoxifen (TM) administration in utero, a dose-dependent subset of Pdx1+ progenitor cells undergoes recombination, whereas nonrecombined cells contribute to normal pancreatic function. Pregnant females from crosses involving all three alleles (KrasG12D, Rosa26NIC, and Pdx1CreERT) were administered 1.5 mg TM at embryonic day 10.5, a dose producing recombination in 25–50% of duct, acinar and islet cells (data not shown).

The resulting offspring were killed at 1 month of age and subjected to histological analysis (Fig. 1 A–F). Rosa26NIC;Pdx1CreERT pancreata contained undifferentiated epithelia similar to those observed in Rosa26NIC;Pdx1Cre (18), albeit affecting much less of the organ (Fig. 1 A and D). As expected, pancreata of KrasG12D;Pdx1CreERT mice exhibited focal mPanIN formation (Fig. 1 B and E), similar to that seen in KrasG12D;Pdx1Cre (2, 3). When both Notch and Kras were activated (KrasG12D;Rosa26NIC;Pdx1CreERT), however, nearly the entire organ was overtaken by PanIN-like epithelium (Fig. 1 C and F). These results suggest that by blocking differentiation, activated Notch sensitizes pancreatic progenitor cells to Kras. The severity of the phenotype, however, precluded quantitative analysis.

Fig. 1.

Notch and Kras synergize to induce mPanIN initiation. (A–I) H&E-stained sections from mice of the indicated genotypes, administered TM in utero (A–F) or left untreated (G–I). Broad mosaic activation of Rosa26NIC, via in utero TM treatment, produces foci of convoluted, undifferentiated epithelium (D, bracket), whereas broad activation of KrasG12D produces isolated mPanIN lesions (E, arrow). Broad coactivation of both alleles results in almost complete replacement of normal exocrine tissue by mPanIN-like epithelium (C and F). Focal mosaic activation of NotchIC or Kras alone, in the absence of TM, produces no or few abnormalities (G and H), whereas focal coactivation of both alleles induces numerous mPanIN lesions (I, arrow). Also indicated are normal ducts (du) and islets (is). (Magnification: A–C 100×, D–F 400×, G–I 200×.) (J) Stripchart of mPanIN initiation indices for individual TM-untreated Pdx1CreERT mice, expressing activated Notch1 (Notch) and/or KrasG12D (Kras), at indicated ages. _P_-values (by t test): *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01.

When we analyzed offspring of mothers that did not receive TM, we found that a low level of TM-independent recombination induced numerous focal mPanIN lesions in KrasG12D; Rosa26NIC;Pdx1CreERT mice (Fig. 1I). By contrast, few or no abnormalities were found in untreated Kras-only or Notch-only pancreata (Fig. 1 G and H). We counted mPanIN lesions across random sections from each animal, to derive a PanIN initiation index (see Materials and Methods). At all ages (1–4 months), there were significantly more mPanIN lesions in KrasG12D;Rosa26NIC coexpressing mice than mice expressing KrasG12D alone, indicating that Notch activation sensitizes cells to transformation by Kras (Fig. 1J).

Like mPanINs described previously (2, 3), those found in both KrasG12D;Pdx1CreERT and KrasG12D;Rosa26NIC;Pdx1CreERT mice express the duct marker cytokeratin-19 (CK19) and produce periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-reactive mucins (see supporting information (SI) Fig. S1 A–F). Rosa26NIC drives coexpression of nuclear EGFP with Notch1IC (18), and we find that CK19+ mPanIN lesions in KrasG12D;Rosa26NIC;Pdx1CreERT mice express EGFP, indicating activation of Rosa26NIC (Fig. S1 G–I). Although KrasG12D;Rosa26NIC coexpressing mPanINs are often larger than those induced by KrasG12D alone, we find no consistent differences in proliferation or apoptosis (the latter of which is extremely rare) between the different classes of lesions (data not shown).

Mature Acinar Cells Represent a Cell of Origin for Kras-Induced mPanINs.

While analyzing KrasG12D;Pdx1CreERT and KrasG12D;Pdx1Cre pancreata, we noted frequent areas of apparent acinar-ductal metaplasia, including cells coexpressing acinar and duct markers, sometimes adjacent to mPanINs (Fig. S2). As with mPanINs themselves, these lesions occur more frequently when Rosa26NIC is coexpressed with KrasG12D (Fig. S3_A_). Similar findings in KrasG12D;Ptf1aCre mice, and in human specimens, suggest that metaplasia may be an early step in the conversion of acini to PanINs (13).

To determine whether PanINs can arise from differentiated acinar cells, we used transgenic mice in which the acinar-specific Elastase1 promoter drives expression of CreERT. This ElaCreERT line has been extensively documented to induce acinar-specific recombination, excluding duct or centroacinar cells (9, 20, 21). Adult (6-weeks-old) KrasG12D;ElaCreERT mice were given 5 mg TM, inducing recombination in ≈50% of acinar cells, and killed 1, 2, or 10 weeks thereafter (i.e., 7 weeks, 2 months, or 4 months of age). Like Pdx1CreERT, ElaCreERT confers a low level of TM-independent recombination (20); we therefore examined additional 2- and 4-month-old mice that did not receive TM. Although most mice did not exhibit gross pancreatic abnormalities, regardless of TM treatment, histological analysis revealed that they often contained mPanIN lesions identical to those observed with general pancreatic Cre drivers (Fig. 2, and see below). In total, at least one mPanIN was found in 12/33 KrasG12D;ElaCreERT pancreata examined, and the likelihood of finding mPanINs increased with the age of the mouse (P < 0.005 by χ2 test for trend). Whereas most mPanIN lesions found were low-grade (mPanIN-1), more advanced mPanIN-2 and mPanIN-3 lesions were found in 6/33 (18%) and 1/33 (3%) of KrasG12D;ElaCreERT pancreata, respectively. These results indicate that mature acinar cells are a potential source of PanINs, and possibly for “ductal” adenocarcinoma as well.

Fig. 2.

Acinar-specific activation of KrasG12D induces mPanIN lesions similar to those induced with general pancreatic Cre drivers. (A and B) H&E-staining of mPanIN lesions in KrasG12D;ElaCreERT mice. Both low-grade mPanIN-1 lesions are found, with columnar cytoplasm and basally located nuclei (A), as well as rarer high-grade lesions, including an mPanIN-3 lesion with nuclear atypia and luminal budding (B). (C) PAS staining (magenta) of acinar-derived mPanIN. (D) Cytokeratin-19 staining (brown) of acinar-derived mPanIN. (Magnification: 400×.)

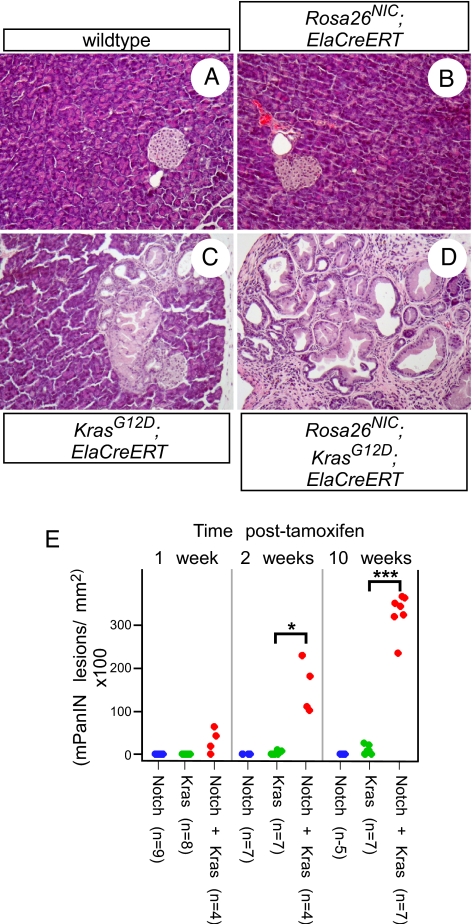

Notch Activation Sensitizes Acinar Cells to Kras-Driven mPanIN Formation and Progression.

Similar to KrasG12D;Pdx1Cre, the vast majority of acinar cells are unaffected in KrasG12D;ElaCreERT mice, with or without TM treatment. As Notch and Kras synergize after activation by PdxCreERT, we asked whether they also synergize in adult acinar cells. In parallel with the KrasG12D;ElaCreERT experiments described above, littermates also inheriting Rosa26NIC were administered 5 mg of TM at 6 weeks of age, and killed 1, 2, or 10 weeks later. Although activation of Rosa26NIC alone in acini had no visible effect (Fig. 3B and see below), it did induce robust expression of the Notch target genes Hes1 and HeyL (Fig. S4). By contrast, coactivation of Rosa26NIC and KrasG12D caused widespread mPanIN formation, exceeding that seen with KrasG12D alone (Fig. 3 C–E). Similar synergy was observed with respect to acinar-ductal metaplasia, for which Notch alone was also ineffective (Fig. S3_B_). Notch/Kras coactivation did not result in greater induction of Hes1 or HeyL than Notch alone (Fig. S4), suggesting that the synergy between these pathways is unlikely to occur at the level of immediate Notch target genes.

Fig. 3.

Notch and Kras synergize to induce mPanINs from acinar cells. (A–D) Representative H&E-stained sections from pancreata of the indicated genotypes, 10 weeks postTM administration. Acinar-specific NotchIC expression has no detectable effect (B), whereas acinar-specific KrasG12D activation induces focal mPanINs (C). Coactivation of the alleles induces many mPanIN lesions, replacing most of the normal exocrine tissue (D). (Magnification: 200×.) (E) Stripchart indicating mPanIN initiation indices of individual ElaCreERT mice, expressing NotchIC and/or KrasG12D, at indicated timepoints following tamoxifen treatment. _P_-values: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0005.

The same relationship was observed in TM-untreated mice (Fig. S5 A and B). For reasons as yet unknown, we found that untreated KrasG12D;ElaCreERT mice exhibited more mPanINs than TM-treated mice at the same age, although the synergy with Rosa26NIC remains dramatic and robust. By contrast, the apparently greater number of mPanINs seen in untreated KrasG12D;_Rosa26NIC_-expressing mice, compared to those receiving TM (Fig. 3E and Fig. S5_A_), likely reflects the fact that untreated pancreata retain more normal exocrine tissue (Fig. S5 C and D). Individual lesions are therefore more easily scored than in TM-treated mice, where the lack of normal tissue makes separate lesions hard to distinguish.

Previous studies of KrasG12D;Pdx1Cre mice indicate that higher-grade mPanIN-2 and mPanIN-3 lesions are much rarer than mPanIN-1, although they become more common as the overall lesion burden increases with age (2). To determine whether Notch affects this process, we developed an mPanIN progression metric based on observation by a blinded pathologist (L.E.), and weighted according to increasing lesion stage (see Materials and Methods). In every ElaCreERT experimental group (i.e., separated by age and TM treatment), the progression index was significantly higher with Notch and Kras together than with activated Kras alone (P < 0.05 by Wilcoxon test). Although this suggested that Notch promotes mPanIN progression, it was also possible that, by enhancing mPanIN initiation, Notch activation would make it likelier to encounter rare advanced lesions even if the progression rate were unchanged. This would predict that the progression index should correlate with overall mPanIN number, irregardless of Rosa26NIC status. As the individual experimental groups were too small to model separately the effects of lesion number and genotype, we pooled all ElaCreERT samples that contained at least one mPanIN and compared the effects of overall mPanIN number and genotype on progression index (Fig. S6). We developed a general linear model, in which progression index was influenced separately by mPanIN number and Rosa26NIC genotype (see Materials and Methods), and found that Rosa26NIC activation significantly correlated with increased progression (P < 5 × 10−6, by F-test). Similar results were obtained by analysis of our Pdx1CreERT samples, either separately or pooled with ElaCreERT, suggesting that Notch promotes both mPanIN initiation and progression.

Formation of PanINs from Acinar Cells via Reprogramming to a Ductal Phenotype.

PanIN and PDA, in humans and mice, typically look like ducts and express duct-specific markers. Nevertheless, our results indicate that mPanINs can arise from mature acinar cells, implying that their formation involves a switch from acinar to ductal differentiation programs. To follow this switch, we examined ElaCreERT mice two weeks following tamoxifen treatment, at which time Kras activation alone has had little or no detectable effect, whereas Notch/Kras coactivation has induced widespread metaplasia (Fig. 3E and Fig. S3_B_). As GFP expression marks cells that have undergone Rosa26NIC activation (18), we performed coimmunofluorescence to monitor expression of acinar and ductal markers in cells expressing activated Notch. As expected, Cre-negative pancreata exhibit no detectable GFP (Fig. 4 A–D and M–P). Also as expected, TM-treated Rosa26NIC;ElaCreERT pancreata exhibit widespread Rosa26NIC activation, indicated by GFP expression (Fig. 4 E and Q). Nonetheless, these cells retain a normal acinar differentiation program: they express the digestive enzyme amylase and the transcription factor Ptf1a (Figs. 4 F and R), a regulator of acinar gene expression (5), and they are negative for the duct marker CK19 (Fig. 4 G and S). Therefore, Notch activation alone does not detectably perturb the differentiation state of mature acinar cells. Following coactivation of Notch and Kras, however, nearly all GFP-expressing cells undergo reprogramming to a duct-like phenotype, including loss of amylase and Ptf1a expression (Fig. 4 J and V) and up-regulation of CK19 (Fig. 4 K and W). A similar reprogramming event must occur in KrasG12D;ElaCreERT mice, as the PanIN lesions that form in these pancreata are positive for CK19 (Fig. 2D) and negative for amylase and Ptf1a (data not shown), but the efficiency of conversion is much higher when Notch is activated together with Kras. These data implicate the reprogramming of acinar cells, including down-regulation of the acinar regulator Ptf1a, in the formation of ductal lesions and tumors from a nonductal cell type.

Fig. 4.

Notch and Kras synergize to induce rapid acinar-to-ductal reprogramming in vivo. Adult (6-week-old) mice of the indicated genotypes were treated with tamoxifen and analyzed two weeks later. (A–L) Immunofluorescence staining for GFP (green, indicating activation of Rosa26NIC), the acinar marker amylase (red) and the duct marker CK19 (white). Activation of Notch in acinar cells results in no detectable changes (E–H, note green nuclei in amylase+ acinar cells, negative for CK19), whereas Notch/Kras coactivation results in ductal reprogramming specifically of GFP-positive cells, as indicated by loss of amylase and up-regulation of CK19 (I–L). (M–X) Immunofluorescence staining for GFP (green), the acinar regulatory transcription factor Ptf1a (red) and CK19 (white) provides further evidence for Notch/Kras-driven reprogramming, as NotchIC expression alone does not result in loss of Ptf1a expression (Q–T), whereas NotchIC/KrasG12D coactivation down-regulates Ptf1a although inducing CK19 (U–X). (Magnification: 400×.)

Discussion

Notch is a critical negative regulator of progenitor cell differentiation in the embryonic pancreas, and its up-regulation in PanINs and pancreatic cancer suggests that it represses the differentiation of tumor-initiating cells (2, 6, 13). This possibility is particularly compelling given evidence that the ductal phenotype of PDA might not reflect a strictly ductal origin. For example, whereas overexpression of activated Kras in acinar cells leads to tumor formation, tumors are not observed on Kras overexpression in ducts (10–12). In addition, activation of endogenous KrasG12D in acinar-restricted precursor cells, via NestinCre, results in mPanIN formation similar to that observed with more widespread pancreatic Cre drivers such as Pdx1Cre and Ptf1aCre (14). These previous experiments, however, do not address the question of whether mature acinar cells can give rise to PanINs, as all of them involved KrasG12D activation in utero or shortly after birth. Here, we have addressed both the contribution of Notch signaling to the initiation of pancreatic tumorigenesis, and the possibility that the acinar cell represents a source for precancerous lesions in the adult.

By using Pdx1CreERT to activate recombination in progenitor cells, we find that Notch dramatically sensitizes cells to _KrasG12D_-driven mPanIN initiation. In addition to mPanINs, we find metaplastic lesions induced by KrasG12D that may represent initial stages of acinar reprogramming to a “pre-PanIN” state. Furthermore, activation of Kras alone in adult acinar cells induces both metaplastic lesions and mPanINs, including high-grade mPanIN-2 and mPanIN-3, suggesting that acini can serve as a cell of origin for PDA. This process is dramatically enhanced when Notch is coactivated with Kras, producing rapid and widespread reprogramming of acinar cells to a duct-like phenotype, and apparently increased progression to high-grade lesions. Together, these results suggest that the observed up-regulation of Notch components in pancreatic cancer is not an epiphenomenon, but reflects a supporting role for Notch in Kras-induced reprogramming and transformation. Both positive and negative interactions between Notch and Ras have been described in other systems, and Notch can promote or inhibit tumorigenesis depending on cellular context (22). In cultured human cells, Ras appears to activate Notch, and this activation is required for transformation (23). In our model, by contrast, we find that Kras activation alone does not induce Notch target genes in the pancreas (Fig. S4), suggesting that the pathways act convergently rather than linearly. Understanding the mechanism of this convergence may identify treatment targets for PDA.

Although several lines of evidence suggest that PanINs represent the early stages of human PDA (1), it remains a formal possibility that they instead represent “dead ends” in the genetic pathway that culminates in PDA. Similarly, although our data and those of others (13) suggest that metaplastic acini are the precursor to mPanIN lesions, we cannot yet rule out the possibility that overtly metaplastic structures, as described here, form independently of mPanINs. Further analysis of the kinetics of lesion formation, preferably by using a Cre driver that exhibits little or no TM-independent recombination, should indicate whether metaplasia clearly precedes mPanIN formation. Direct proofs of metaplasia-to-mPanIN and mPanIN-to-PDA progression will require more sophisticated lineage-tracing tools than currently exist.

Although our results suggest a model to unify diverse observations in the literature, we note some potential discrepancies. Although Rosa26NIC activation in utero blocks acinar differentiation (18), we find that activation in mature acini is not sufficient for ductal reprogramming. In culture, however, Notch activation is both necessary and sufficient for acinar-ductal reprogramming (6). These in vitro studies used adenoviral vectors to express activated Notch1, which may result in higher expression than our Rosa26 knock-in strategy; alternatively, placing acinar cells in culture may enhance endogenous Kras signaling. In addition, whereas we show that KrasG12D activation in acinar cells is sufficient for at least a small number of mPanINs to form, Guerra et al. (15) find that mPanINs do not form at all on acinar activation of an endogenous KrasG12V allele, unless the pancreas is subjected to caerulein-induced pancreatitis. This group used a tetracycline-regulated system to direct acinar-specific recombination, although ours is tamoxifen-regulated, but given that 6/11 TM-untreated KrasG12D;ElaCreERT mice developed at least one mPanIN lesion in our study (versus 6/14 of TM-treated mice at the same ages), the use of tamoxifen cannot explain the discrepancy. A more plausible explanation is that differences in the targeted Kras alleles affect their expression or function, as KrasG12D has been shown to induce transformation in lung under circumstances in which KrasG12V appears less active (24, 25).

Nonetheless, chronic pancreatitis is an important risk factor for human pancreatic cancer (1), and the fact that caerulein pancreatitis sensitizes the mouse pancreas to activated Kras is likely relevant to our model. Caerulein pancreatitis promotes acinar-ductal metaplasia, and is associated with Notch pathway up-regulation (7, 16, 17). As our study leaves open the question of how endogenous Notch becomes activated in mPanINs induced by Kras alone, further investigation of the links between pancreatitis, Notch activation and PanIN initiation are clearly warranted. Our work also leaves open the question of whether Notch signaling is necessary, as well as sufficient, for _KrasG12D_-induced mPanIN initiation and progression. Finally, as our study design focused on relatively short-term effects of Notch and Kras, we cannot determine whether the synergy between these pathways extends to the formation of fully invasive tumors. Aged KrasG12D;Pdx1Cre mice do exhibit rare PDA (2), and we hypothesize that studies of older mice in our cohorts will reveal a contribution of Rosa26NIC to invasive tumor formation.

A final issue left unresolved by our work is whether acinar cells represent the only cell of origin for mPanINs. In the uninjured pancreas, the Notch target gene Hes1 is expressed primarily by centroacinar cells (CACs), terminal cells of the duct network, and these have also been proposed as cells of origin for PanINs and PDA (1, 6). Evidence for this derives from pancreas-specific deletion of the Pten tumor suppressor, which causes expansion and transformation of Hes1-expressing CACs, without acinar-ductal reprogramming (21). Importantly, no ductal lesions formed when Pten was deleted exclusively in acinar cells (using the same ElaCreERT driver used here). Although PTEN loss-of-function mutations have not been reported in human pancreatic cancer, amplification of AKT2, encoding a kinase epistatic to PTEN, is found in a minority of PDAs (1). It is tempting to speculate that these tumors may arise from a different lineage, possibly through distinct mechanisms, than the acinar-to-ductal pathway identified here. Testing whether adult CAC or ductal cells are competent to form PanINs, on activation of Kras and/or Akt signaling, will require the development of temporally regulated Cre drivers specific to these compartments, an important priority for the field. In the meantime, our work allows us to conclude that acinar cells, via Notch-mediated ductal reprogramming, represent at least one potential major source for Kras-induced lesions. Future studies should elucidate the mechanism of, and requirement for, interaction between these critical signaling pathways.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Pdx1CreERT (19), ElaCreERT (9, 20, 21), KrasG12D (2), and Rosa26NIC (18) mice have been described previously, and were genotyped by PCR on tail biopsy DNA. As neither KrasG12D nor Rosa26NIC is expressed in the absence of Cre, Cre-negative littermates from these crosses served as wild-type controls. Tamoxifen (TM) was dissolved in corn oil and administered by oral gavage. All experiments were carried out according to institutional guidelines.

Tissue Processing and Histology.

After euthanasia, pancreata were dissected, cut into 5–6 fragments, and processed to frozen or paraffin sections as described (20). PAS staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma). Primary antibodies included rat anti-cytokeratin 19 1:50 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), sheep anti-amylase 1:2,500 (BioGenesis), rabbit anti-GFP 1:5,000 (Abcam), and guinea pig anti-Ptf1a 1:5,000 (gift of Dr. Jane Johnson, U.T. Southwestern), and secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch. Paraffin sections were subjected to high temperature antigen retrieval (Vector Unmasking Solution) before adding primary antibody. Vectastain reagents and Vector diaminobenzidine substrate were used for immunohistochemistry.

Lesion Scoring.

Paraffin sections were cut from two independent dorsal and one ventral fragment of each pancreas. After H&E staining of a single section from each fragment, and photomicrography/photomerging (Adobe Photoshop), the area of the section was determined with ImageJ software (NIH). mPanIN lesions were then tallied under the microscope, and the PanIN initiation index was defined as the number of lesions per mm2, multiplied by 100, and averaged across the three sections scored for each mouse. Metaplastic lesions were scored similarly. In severely affected areas, lesions were scored as separate only if they appeared in anatomically distinct lobules. The same slides were subsequently evaluated, blindly, by a surgical pathologist (L.E.), who scored mPanIN lesions as 1A, 1B, 2, or 3 (4), and recorded the five highest-grade lesions per animal. The PanIN progression index was derived from this data as: 1× (# mPanIN-1A/1B) + 2× (# mPanIN-2) + 3× (# mPanIN-3), resulting in scores from 0 (no mPanIN lesions at all) to 15 (five mPanIN-3 lesions found). Any score above 5 must reflect the presence of at least one high-grade mPanIN-2 or mPanIN-3 lesion.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR.

RT-PCR was performed on ElaCreERT mice 7 days after TM treatment, at which point minimal gross changes were evident (Fig. 3E and data not shown). RNA was isolated from approximately half of the dorsal pancreas by guanidinium isothiocyanate (26). Realtime RT-PCR was performed on an ABI 7900HT instrument (Applied Biosystems), by using SYBR Green. Quantification was done by ΔΔCt method, normalizing to the housekeeping gene Hprt1. Primers are listed in Table S1, and were selected from the PrimerBank database (27).

Statistics.

All statistical analysis was performed with the R software package (28). Comparisons of PanIN initiation indices were performed by Welch's t test (i.e., not assuming equal variances), with Holm's correction for multiple comparisons. Realtime PCR expression levels were compared to wildtype by ANOVA. PanIN progression indices were modeled as a function of PanIN initiation index (continuous) and Rosa26NIC genotype (categorical), by using a general linear model with quasipoisson error distribution, and the contributions of the variables were evaluated by F-test.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments.

We thank Doug Melton (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA), Tyler Jacks (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA), and Jane Johnson (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) for providing reagents, Steve Leach for helpful discussions, and Kristen Kwan and Daniel Kopinke for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants to L.C.M. from the Lustgarten Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research (RFP06-059), Searle Scholars Program (06-B-116), and National Cancer Institute (R21-CA123066), and by a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support grant (P30-CA042014) to the Huntsman Cancer Institute. J.-P.D.L.O. is supported by National Institutes of Health Developmental Biology Training Grant 5T32-HD07491.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Maitra A, Hruban RH. Pancreatic cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:157–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hingorani SR, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguirre AJ, et al. Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gene Dev. 2003;17:3112–3126. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hruban RH, et al. Pathology of genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic exocrine cancer: Consensus report and recommendations. Cancer Res. 2006;66:95–106. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen J. Gene regulatory factors in pancreatic development. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:176–200. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyamoto Y, et al. Notch mediates TGF alpha-induced changes in epithelial differentiation during pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siveke JT, et al. Notch signaling is required for exocrine regeneration after acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:544–555. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Means AL, et al. Pancreatic epithelial plasticity mediated by acinar cell transdifferentiation and generation of nestin-positive intermediates. Development. 2005;132:3767–3776. doi: 10.1242/dev.01925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strobel O, et al. In vivo lineage tracing defines the role of acinar-to-ductal transdifferentiation in inflammatory ductal metaplasia. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1999–2009. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grippo PJ, Nowlin PS, Demeure MJ, Longnecker DS, Sandgren EP. Preinvasive pancreatic neoplasia of ductal phenotype induced by acinar cell targeting of mutant Kras in transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2016–2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuveson DA, et al. Mist1-KrasG12D knock-in mice develop mixed differentiation metastatic exocrine pancreatic carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:242–247. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brembeck FH, et al. The mutant K-ras oncogene causes pancreatic periductal lymphocytic infiltration and gastric mucous neck cell hyperplasia in transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2005–2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu L, Shi G, Schmidt CM, Hruban RH, Konieczny SF. Acinar cells contribute to the molecular heterogeneity of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:263–273. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carriere C, Seeley ES, Goetze T, Longnecker DS, Korc M. The Nestin progenitor lineage is the compartment of origin for pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4437–4442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701117104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerra C, et al. Chronic pancreatitis is essential for induction of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by K-Ras oncogenes in adult mice. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez G, Englander EW, Wang G, Greeley GH., Jr Increased expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha, p48, and the Notch signaling cascade during acute pancreatitis in mice. Pancreas. 2004;28:58–64. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen JN, Cameron E, Garay MV, Starkey TW, Gianani R, Jensen J. Recapitulation of elements of embryonic development in adult mouse pancreatic regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:728–741. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murtaugh LC, Stanger BZ, Kwan KM, Melton DA. Notch signaling controls multiple steps of pancreatic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14920–14925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436557100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu G, Dubauskaite J, Melton DA. Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development. 2002;129:2447–2457. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murtaugh LC, Law AC, Dor Y, Melton DA. Beta-Catenin is essential for pancreatic acinar but not islet development. Development. 2005;132:4663–4674. doi: 10.1242/dev.02063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanger BZ, et al. Pten constrains centroacinar cell expansion and malignant transformation in the pancreas. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundaram MV. The love-hate relationship between Ras and Notch. Gene Dev. 2005;19:1825–1839. doi: 10.1101/gad.1330605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weijzen S, et al. Activation of Notch-1 signaling maintains the neoplastic phenotype in human Ras-transformed cells. Nat Med. 2002;8:979–986. doi: 10.1038/nm754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guerra C, et al. Tumor induction by an endogenous K-ras oncogene is highly dependent on cellular context. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:111–120. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson EL, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Gene Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacDonald RJ, Swift GH, Przybyla AE, Chirgwin JM. Isolation of RNA using guanidinium salts. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:219–227. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Seed B. A PCR primer bank for quantitative gene expression analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crawley MJ. The R Book. Chichester, England: Wiley; 2007. Hoboken, N.J. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information