Novel Mutations in the ZEB1 Gene Identified in Czech and British Patients With Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2009 Jun 16.

Published in final edited form as: Hum Mutat. 2007 Jun;28(6):638. doi: 10.1002/humu.9495

Abstract

We describe the search for mutations in six unrelated Czech and four unrelated British families with posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD); a relatively rare eye disorder. Coding exons and intron/exon boundaries of all three genes (VSX1, COL8A2, and ZEB1/TCF8) previously reported to be implicated in the pathogenesis of this disorder were screened by DNA sequencing. Four novel pathogenic mutations were identified in four families; two deletions, one nonsense, and one duplication within exon 7 in the ZEB1 gene located at 10p11.2. We also genotyped the Czech patients to test for a founder haplotype and lack of disease segregation with the 20p11.2 locus we previously described. Although a systematic clinical examination was not performed, our investigation does not support an association between ZEB1 changes and self reported non-ocular anomalies. In the remaining six families no disease causing mutations were identified thereby indicating that as yet unidentified gene(s) are likely to be responsible for PPCD.

Keywords: posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy, ZEB1, TCF8, VSX1, COL8A2, heterogeneity

INTRODUCTION

Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) is a relatively rare bilateral eye disorder that primarily affects the endothelium and Descemet’s membrane (Krachmer, 1985). It is usually transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait, although an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance has also been suggested in some pedigrees (Cibis, et al., 1977; Soukup, 1964). Clinically, PPCD is characterized by vesicles, bands and geographic opacities of the posterior corneal layers. In a minority of cases peripheral anterior iris adhesions, iris atrophy, corectopia, corneal edema, and glaucoma develop as secondary changes (Cibis, et al., 1977; Laganowski, et al., 1991). The disease shows significant intrafamilial phenotypic variability with incomplete penetrance (Cibis, et al., 1977; Krafchak, et al., 2005). Ultrastructure examination shows thickening of Descement’s membrane and fibroblastic and epithelial-like transformation of the endothelial cells, including an ability to divide (de Felice, et al., 1985; Polack, et al., 1980; Henriquez, et al., 1984).

Posterior polymorphous dystrophy is genetically a heterogeneous disease. PPCD1 (MIM# 122000) was mapped to chromosome 20 (Heon, et al., 1995). Mutations in a visual system homeobox gene 1 (VSX1; MIM# 605020) within the original linked interval were implicated as disease causing in some PPCD patients (Heon, et al., 2002; Valleix, et al., 2006). However, this finding was not confirmed by other reports which excluded VSX1 by linkage analysis and by direct sequencing (Gwilliam, et al., 2005; Aldave, et al., 2004). Linkage data indicates that there is another, as yet unidentified, PPCD1 gene on chromosome 20p11.2 (Gwilliam, et al., 2005). PPCD2 (MIM# 609140) is caused by the alpha-2 chain of type VIII collagen gene (COL8A2; MIM# 120252) located on 1p34.3-p32.3 with one disease causing mutation identified to date (Biswas, et al., 2001). Most recently, three frame shift and two nonsense mutations in five unrelated PPCD3 (MIM# 609141) families have been reported in a zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 gene (ZEB1; MIM# 189909), also known as human zinc finger transcription factor 8 (TCF8), mapped to chromosome 10p11.2. It was estimated that changes in this gene may account for about 50 % of all PPCD cases (Krafchak, et al., 2005).

We have screened the coding regions of three genes implicated in PPCD (ZEB1, COL8A2 and VSX1) in ten unrelated families, six of Czech origin and four of British origin. Four novel pathogenic mutations within the ZEB1 gene were detected in four families, supporting the importance of ZEB1 mutations in the pathogenesis of PPCD and lack of a founder ZEB1 mutation in the Czech PPCD population. We have also evaluated the potential association of non-ocular phenotypes with mutations in ZEB1.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Clinical Evaluation

The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and had local Ethics Committee approval. After obtaining signed informed consent, 36 individuals from six white Czech and four white British families underwent standard ophthalmologic examination including visual acuity, intraocular pressure measurement and biomicroscopy. Patients were diagnosed with PPCD if they exhibited the characteristic endothelial changes in both eyes (Krachmer, 1985; Cibis, et al., 1977). A detailed family and personal history was taken and pedigrees constructed. Patients were specifically asked about non-ocular anomalies that had previously been reported to be associated with changes in the ZEB1 gene; inguinal hernias, hydrocele, extra vertebrae, bone spurs on vertebrae, lumps on kneecaps, bony lumps on the palms and soles associated with Dupuytren’s contracture, kneecap dislocations, Osgood-Schlatter disease and otosclerosis (Krafchak, et al., 2005). The Czech families in this study did not come from the same region of the Czech Republic as the two large families with PPCD1 who were previously mapped to chromosome 20p11.2 and in which VSX1 was excluded as a candidate gene (Gwilliam, et al., 2005).

DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification

Blood samples (10 ml) were taken from participating family members. DNA was prepared from peripheral blood leucocytes using the Nucleon III BACC3 genomic DNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (GE Healthcare, UK). Each coding exon along with exon-intron junctions of the published reference sequences of ZEB1 (NCBI Accession NM_030751.2), COL8A2 (NCBI Accession NM_005202.1) and VSX1 (NCBI Accession NM_014588.4 and NM_199425.1) genes was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using forward and reverse pairs of primers. Amplification was carried out in a 25 μl mixture containing 12.5 μl of ReddyMix™ PCR master mix (ABgene, UK), with 50 pmoles gene-specific primers and approximately 50 ng of genomic DNA. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are available on request.

Haplotype Analysis

Polymorphic fluorescently-labeled microsatellite markers D20S98, D20S114, D20S48, D20S605, D20S182, M189K21, D20S139, D20S106 were amplified in patients from all six Czech families and analyzed using an ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA) as previously described (Gwilliam, et al., 2005).

Mutational Analysis

The PCR amplicons were purified with Montage PCR96 Cleanup Kit (Millipore, USA) and sequenced for both strands. Direct sequencing of all gene fragments was performed using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems) on a fluorescent sequencer (ABI 3100) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Nucleotide sequences were compared with the published reference sequences. Mutation nomenclature follows HGVS recommendations with +1 as A of ATG initiation codon (Antonarakis, 1998; den Dunnen and Antonarakis, 2000). One affected individual from each of the ten families was used for initial mutational screening. Where sequence changes were identified, other available affected and unaffected family members were sequenced to confirm segregation with disease, as well as 51 white Czech and 94 white British unrelated population control individuals to confirm potential pathogenicity.

RESULTS

Following detailed clinical examination, 24 family members (14 males, 10 females) from ten families were diagnosed with PPCD. Previously we described a haplotype consisting of alleles for eight microsatellite markers in two Czech families showing linkage to 20p11.2 (Gwilliam, et al., 2005). However, the six families in the current study do not exhibit a haplotype similar to the previously published families indicating a lack of founder effect and further genetic heterogeneity in the Czech population. All three previously reported PPCD genes were therefore analysed in these families.

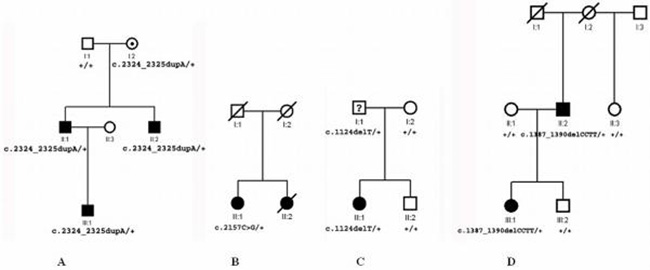

Sequence analysis of the ZEB1 gene revealed a heterozygous single-base duplication, c.2324_2325dupA, in exon 7 that co-segregated with all three affected members of family C1 of Czech origin (Fig. 1a) and was also found in the clinically unaffected mother. The mutation is predicted to result in a frame shift at codon 776 (p.E776fs) leading to a termination codon 43 residues downstream of the mutation site.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of PPCD families with novel mutations in the ZEB1 gene identified in this study. A: Czech family C1 showing a heterozygous single-base duplication c.2324_2325dupA resulting in a frame shift with glutamic acid at codon 776 (p.E776fs). B: Czech family C2 showing a heterozygous single-base pair transition c.2157C>G changing tyrosine at position 719 to a stop codon (p.Y719X). C: British family B1 showing a heterozygous single-base pair deletion c.1124delT resulting in a frame shift with phenylalanine at codon 375 (p.F375fs). D: British family B2 showing a heterozygous four-base pair deletion c.1387_1390delCCTT resulting in a frame shift with proline at codon 463 (p.P463fs).

A single-base pair transition, c.2157C>G, changing tyrosine to a stop codon at position 719 (p.Y719X) in exon 7, was identified in a member of family C2 of Czech origin (Fig. 1b). The stop codon is predicted to result in truncation of the ZEB1 protein by 406 amino acids. Only this affected individual from family C2 was available for clinical and molecular genetic analysis, however familial occurrence of the disease was demonstrated as clinical findings consistent with PPCD in this patient and her sister were reported in 1964 by Soukup (1964) who also examined 18 other family members including all first degree relatives, none of whom was clinically affected (Soukup, 1964).

A heterozygous single-base pair deletion, c.1124delT, predicted to lead to a frame shift at codon 375 (p.F375fs) and thus to an aberrant protein with 30 additional residues was found in two members from family B1of British origin and was absent in one unaffected first degree relative (Fig. 1c). Clinical records of individual I:1 were not available and therefore the phenotype could not be ascertained.

The fourth mutation identified was a heterozygous four-base pair deletion, c.1387_1390delCCTT, predicted to result in a frame shift at codon 463 (p.P463fs) with a stop codon 28 residues after this change in two subjects from family B2 of British origin. Two unaffected relatives and a spouse did not display this mutation (Fig. 1d).

None of the novel changes identified in this study was detected in the control population of the same ethnic origin, as determined by direct sequencing of 51 Czech (102 chromosomes) and 94 British individuals (188 chromosomes).

Nine individuals (five males and four females, aged 18 to 74 years) who carried the ZEB1 mutations were asked in detail about non-ocular features previously associated with changes in the ZEB1 gene (Krafchak, et al., 2005). Patient II:1 from family C1 aged 47 was diagnosed with hydrocele, patient II:1 from family C2 aged 74 complained about pain in her neck however its intensity did not require any further investigation, she could not comment if she had any bone spurs on her vertebrae. She had undergone surgery for inguinal hernia and also for repeating luxation of one of her fingers. Her sister and parents were dead and no detailed personal history on them was available. Patient II:2 aged 68 from family B1 is under investigation because of an acquired deafness. Its cause has not been established. There was no evidence of co-segregation of these abnormalities within the families. The remaining subjects were unaware of any non-ocular features, but a physical systematic examination was not performed.

Sequencing of the VSX1 and the COL8A2 gene did not reveal any pathogenic sequence variants. The remaining four Czech and two British pedigrees had no disease causing changes in any of the three PPCD genes.

DISCUSSION

PPCD is a genetically heterogeneous disease. It has recently been reported that changes within the ZEB1 gene are responsible for the pathogenesis in a large percentage of patients with this corneal disorder (Krafchak, et al., 2005). ZEB1 maps to chromosome 10p11.2, comprises 9 exons and encodes a transcription factor that is organized in multiple functional domains starting with N-terminal zinc finger clusters (172-292), followed by a homeodomain (581-640), repression domain (754-901), C-terminal zinc finger clusters (905-981) and acidic activation domain (1011-1124) (Ikeda, et al., 1998). We have identified four novel disease mutations within the ZEB1 gene in subjects with PPCD, in four of ten unrelated PPCD families. All of the mutations described in this report are in exon 7. The nature of these mutations, leading to frame shifts and a stop codon, and the absence of these changes in control populations confirms that they are likely to be pathogenic. Eight out of nine different mutations identified to date in the ZEB1 gene, including the four reported in this study, were in exon 7 (Krafchak, et al., 2005). It would therefore seem useful to start ZEB1 screening for sequence variants with this exon.

If protein were produced by these changed ZEB1 genes, and not eliminated due to nonsense-mediated decay of the mRNA, it would lack amino acid sequences of important functional domains. The c.1124delT and c.1387_1390delCCTT change would result in the elimination of the homeodomain, repression domain, the second cluster of zinc fingers and the acidic activation domain, while the c.2157C>G and c.2324_2325dupA mutations would result in the complete or partial elimination of the repression domain respectively, elimination of the second cluster of zinc fingers and the acidic activation domain. All mutations identified in the ZEB1 gene to date (Krafchak, et al., 2005; and this study) are nonsense or frame shift mutations predicted to lead to premature truncation of the ZEB1 protein. This suggests that haploinsufficiency is a potential disease mechanism.

Identification of ZEB1 mutations in PPCD families from two different European populations confirms that the ZEB1 gene plays an important role in the pathogenesis of this disorder worldwide. The finding in our study that in six of the ten families there were no pathogenic changes in the coding exons of ZEB1, COL8A2 or VSX1 suggests that PPCD in these patients might be caused by other unidentified mutations within the refined PPCD locus on 20p11.2 (Gwilliam, et al., 2005). The possibility also exists that more novel genes remain to be identified, or that large gene deletions and pathogenic changes in noncoding regions of the three PPCD genes may not have been detected.

PPCD caused by mutations in ZEB1 exhibits incomplete penetrance (Krafchak, et al., 2005). This feature can cause uncertainties in establishing the inheritance pattern, as in family C2 (Fig. 1b) examined by Soukup (1964) (Soukup, 1964) leading previously to speculation of a possible autosomal recessive inheritance (Tripathi, et al., 1974). In this study apparent non-penetrance was present in family C1 (Fig. 1a) in a 70 year old female. Although it cannot be excluded that disease will still develop later in her life we consider that this is unlikely given her age.

Six of the nine individuals carrying a ZEB1 change were unaware of having any of the non-ocular anomalies reported by Krafchak et al (2005), who observed inguinal hernia and/or hydrocele in 11 out of 14 males and various orthopedic abnormalities in other individuals with PPCD (Krafchak, et al., 2005). Although we could not perform detailed orthopedic examination including radiograph imaging, some of these conditions such as lumps on kneecaps or Dupuytren’s contractures are readily noticeable. One of the three remaining individuals had hearing loss, but it could not be confirmed that this was the result of otosclerosis.

Further investigation on genotype-phenotype correlation is needed to determine if PPCD subtypes caused by different genes and mutations can be distinguished based on clinical and ultrastructural ocular features.

In conclusion ZEB1 appears to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of PPCD. In this study four out of 10 families were found to carry mutations in ZEB1. Probands from the remaining six families screened for all three known genes implicated in PPCD did not carry any pathogenic coding sequence variant, implying that in a large proportion of patients, the disorder is probably caused by changes in as yet identified gene(s) and that VSX1 and COL8A2 are a rare cause of PPCD. Our work supports further genetic heterogeneity for PPCD.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsors: The Special Trustees of Moorfields Eye Hospital, Grant Agency of the Czech Republic and Ministry of Education of the Czech Republic; Grant numbers: 301/03/1040 and MSM 0021620806-VZ-206100-11.

REFERENCES

- Aldave AJ, Yellore VS, Principe AH, Abedi G, Merrill K, Raber I, Small KW, Udar N. Candidate Gene Screening for Posterior Polymorphous Dystrophy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45(5):1526. [Google Scholar]

- Antonarakis SE, Nomenclature Working Group Recommendations for a nomenclature system for human gene mutations. Hum Mutat. 1998;11(1):1–3. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)11:1<1::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Munier FL, Yardley J, Hart-Holden N, Perveen R, Cousin P, Sutphin JE, Noble B, Batterbury M, Kielty C. Missense mutations in COL8A2, the gene encoding the alpha2 chain of type VIII collagen, cause two forms of corneal endothelial dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(21):2415–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.21.2415. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibis GW, Krachmer JA, Phelps CD, Weingeist TA. The clinical spectrum of posterior polymorphous dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95(9):1529–37. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450090051002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Felice GP, Braidotti P, Viale G, Bergamini F, Vinciguerra P. Posterior polymorphous dystrophy of the cornea. An ultrastructural study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1985;223(5):265–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02153657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE. Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: a discussion. Hum Mutat. 2000;15(1):7–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<7::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwilliam R, Liskova P, Filipec M, Kmoch S, Jirsova K, Huckle EJ, Stables CL, Bhattacharya SS, Hardcastle AJ, Deloukas P. Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy in Czech families maps to chromosome 20 and excludes the VSX1 gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(12):4480–4. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0269. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriquez AS, Kenyon KR, Dohlman CH, Boruchoff SA, Forstot SL, Meyer RF, Hanninen LA. Morphologic characteristics of posterior polymorphous dystrophy. A study of nine corneas and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984;29(2):139–47. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(84)90171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heon E, Greenberg A, Kopp KK, Rootman D, Vincent AL, Billingsley G, Priston M, Dorval KM, Chow RL, McInnes RR. VSX1: A gene for posterior polymorphous dystrophy and keratoconus. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11(9):1029–1036. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1029. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heon E, Mathers WD, Alward WL, Weisenthal RW, Sunden SL, Fishbaugh JA, Taylor CM, Krachmer JH, Sheffield VC, Stone EM. Linkage of posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy to 20q11. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4(3):485–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Halle JP, Stelzer G, Meisterernst M, Kawakami K. Involvement of negative cofactor NC2 in active repression by zinc finger-homeodomain transcription factor AREB6. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(1):10–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krachmer JH. Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy: a disease characterized by epithelial-like endothelial cells which influence management and prognosis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1985;83:413–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krafchak CM, Pawar H, Moroi SE, Sugar A, Lichter PR, Mackey DA, Mian S, Nairus T, Elner V, Schteingart MT. Mutations in TCF8 cause posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy and ectopic expression of COL4A3 by corneal endothelial cells. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77(5):694–708. doi: 10.1086/497348. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganowski HC, Sherrard ES, Muir MG. The posterior corneal surface in posterior polymorphous dystrophy: a specular microscopical study. Cornea. 1991;10(3):224–32. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polack FM, Bourne WM, Forstot SL, Yamaguchi T. Scanning electron microscopy of posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;89(4):575–84. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(80)90070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukup F. Polymorphous Posterior Degeneration of the Cornea. Cesk Oftalmol. 1964;20:181–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi RC, Casey TA, Wise G. Hereditary posterior polymorphous dystrophy an ultrastructural and clinical report. Trans Ophthal Soc U.K. 1974;94:211–25. [Google Scholar]

- Valleix S, Nedelec B, Rigaudiere F, Dighiero P, Pouliquen Y, Renard G, Le Gargasson JF, Delpech M. H244R VSX1 is associated with selective cone ON bipolar cell dysfunction and macular degeneration in a PPCD family. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(1):48–54. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]