Mucosal Lipocalin 2 Has Pro-Inflammatory and Iron-Sequestering Effects in Response to Bacterial Enterobactin (original) (raw)

Abstract

Nasal colonization by both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens induces expression of the innate immune protein lipocalin 2 (Lcn2). Lcn2 binds and sequesters the iron-scavenging siderophore enterobactin (Ent), preventing bacterial iron acquisition. In addition, Lcn2 bound to Ent induces release of IL-8 from cultured respiratory cells. As a countermeasure, pathogens of the Enterobacteriaceae family such as Klebsiella pneumoniae produce additional siderophores such as yersiniabactin (Ybt) and contain the iroA locus encoding an Ent glycosylase that prevents Lcn2 binding. Whereas the ability of Lcn2 to sequester iron is well described, the ability of Lcn2 to induce inflammation during infection is unknown. To study each potential effect of Lcn2 on colonization, we exploited K. pneumoniae mutants that are predicted to be susceptible to Lcn2-mediated iron sequestration (iroA ybtS mutant) or inflammation (iroA mutant), or to not interact with Lcn2 (entB mutant). During murine nasal colonization, the iroA ybtS double mutant was inhibited in an Lcn2-dependent manner, indicating that the iroA locus protects against Lcn2-mediated growth inhibition. Since the iroA single mutant was not inhibited, production of Ybt circumvents the iron sequestration effect of Lcn2 binding to Ent. However, colonization with the iroA mutant induced an increased influx of neutrophils compared to the entB mutant. This enhanced neutrophil response to Ent-producing K. pneumoniae was Lcn2-dependent. These findings suggest that Lcn2 has both pro-inflammatory and iron-sequestering effects along the respiratory mucosa in response to bacterial Ent. Therefore, Lcn2 may represent a novel mechanism of sensing microbial metabolism to modulate the host response appropriately.

Author Summary

Bacterial pathogens such as Klebsiella pneumoniae require iron and use secreted molecules called siderophores to strip iron from mammalian proteins. When bacteria colonize the upper respiratory tract, the mucosa secretes the protein lipocalin 2 (Lcn2) that binds to the siderophore enterobactin (Ent) and disrupts bacterial iron acquisition. In addition, Lcn2 bound to Ent stimulates release of the neutrophil-recruitment signal IL-8 from cultured respiratory cells. Some pathogens avoid Lcn2 binding by attaching glucose to Ent (to make Gly-Ent) or by making alternative siderophores. To determine the effect of Lcn2 on bacterial colonization, we colonized mice that express or lack Lcn2 with K. pneumoniae mutants that express or lack Ent, Gly-Ent and the alternative siderophore Yersiniabactin (Ybt). Our results indicate that mucosal Lcn2 inhibits colonization through iron sequestration and increases the influx of neutrophils in response to K. pneumoniae producing Ent. Therefore, Lcn2 acts as a barrier to colonization that pathogens must overcome to persist in the upper respiratory tract.

Introduction

Bacteria utilize iron for electron transport, amino acid synthesis, DNA synthesis, and protection from superoxide radicals [1]. Under aerobic conditions, iron is primarily in the ferric (Fe (III)) oxidation state and readily forms insoluble complexes. Sequestration of the scarce quantities of soluble iron is a prototypical protective response against invading bacteria, mediated by the iron-binding proteins transferrin and lactoferrin and the storage protein ferritin. To acquire iron within the host, bacteria secrete siderophores such as enterobactin (Ent) that bind ferric iron with greater affinity than mammalian proteins.

In the thrust and parry between bacteria and their host to obtain iron, a new form of competition has been identified. Lipocalin 2 (Lcn2, also known as NGAL, siderocalin and 24p3) is a member of the lipocalin family of small-molecule transport proteins [2]. Lcn2 specifically binds Ent with an affinity similar to the Escherichia coli Ent receptor [2] and competes with bacteria for Ent binding.

Lcn2 is able to bind both ferric and aferric Ent, thereby depleting Ent from the microenvironment and inhibiting bacterial uptake of Ent-bound iron. As a result, Lcn2 is bacteriostatic. Bacterial growth can be restored by the addition of excess iron [2] or Ent [3]. In a murine sepsis model, serum Lcn2 is protective against an E. coli strain that requires Ent to obtain iron. Accordingly, Lcn2-deficient mice (Lcn2−/−) succumb to infection [3]. Conversely, co-injection of E. coli and a siderophore to which Lcn2 cannot bind causes lethal infection in Lcn2+/+ mice [3].

Originally isolated from the specific granules of neutrophils, Lcn2 is also found in mucus producing cells of the respiratory tract [4]–[6]. In mice, the nasal mucosa responds to Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization by increasing Lcn2 mRNA expression (65-fold) [6]. Consequently, protein levels increase in olfactory glands and respiratory and olfactory epithelial cells. Lcn2 is secreted into the nasal lumen and bathes the colonized mucosa. Lcn2 is also induced by Haemophilus influenzae colonization, suggesting its production is a general response to colonizing bacteria [6].

In addition to sequestering iron, Lcn2 can act as a signaling molecule. A murine Lcn2 receptor, 24p3R, has been identified and is widely expressed in tissues including the lung and in lymphoid and myeloid cells [7]. In lymphocytic cells, 24p3R is able to internalize Lcn2 alone or Lcn2 bound to a siderophore. Internalization of Lcn2 bound to an iron-loaded siderophore increases the intracellular iron concentration. However, internalization of Lcn2 bound to an iron-free siderophore depletes intracellular iron levels by binding to cellular iron followed by export from the cell through recycling endosomes. In respiratory epithelial cells, Lcn2 elicits chemokine release [8]. In A549 and other human respiratory epithelial cell lines, incubation with aferric Ent produces a dose-dependent increase in the secretion of the chemokine IL-8 [8]. This response is potentiated by the addition of Lcn2 to form aferric Ent-Lcn2. In contrast, ferric Ent (Fe-Ent) does not elicit significant IL-8 release. Whether Lcn2 induces chemokine release and neutrophil recruitment during bacterial infection is unknown.

Perhaps due to the actions of Lcn2, successful pathogens do not typically depend solely on Ent for iron [9]. Pathogens such as Klebsiella pneumoniae often produce additional siderophores [9],[10] that Lcn2 is not predicted to bind [11]. Salmonella enterica and certain K. pneumoniae and E. coli isolates also encode the iroA locus that can counteract Lcn2 [12]–[17]. This cluster encodes the Ent glycosylase IroB that prevents Lcn2 binding, and IroC to export, IroN to import, and IroD to linearize glycosylated Ent [18],[19]. Transformation of E. coli with the iroA locus is sufficient to cause lethal infection in Lcn2+/+ mice [19]. Conversely, disruption of either the iroC exporter or iroB glycoslyase attenuates virulence in a mouse model of systemic Salmonella infection [20]. In K. pneumoniae, this locus is associated with strains causing invasive disease (pyogenic liver abscesses) in patients [17].

Lcn2 could represent a new paradigm of mucosal immunity based on recognition of bacterial siderophores leading to direct iron sequestration and subsequent pro-inflammatory signaling. To test the antibacterial effects of mucosal Lcn2, a respiratory pathogen that produces Ent is required. A gram-negative, non-motile, encapsulated member of the family Enterobacteriaceae, K. pneumoniae colonizes both the nasopharynx and large intestine of humans [21], and is a common cause of bacterial pneumonia and sepsis. The wild-type K. pneumoniae strain ATCC 43816 produces Ent, contains the iroA locus, and produces a second siderophore, Yersiniabactin (Ybt) [22]. By exploiting defined K. pneumoniae siderophore mutants and Lcn2-deficient mice, we determined whether Lcn2 inhibits bacterial colonization by sequestering iron, promoting inflammation, or both.

Results

Establishment of a murine model of K. pneumoniae nasal colonization

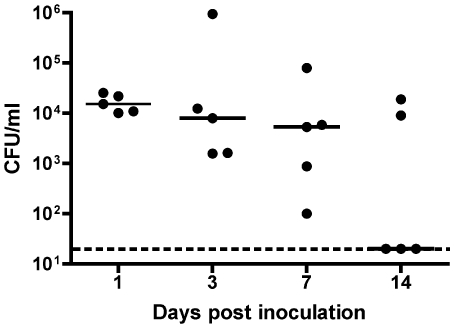

Previously a murine model of K. pneumoniae pneumonia was established and characterized [22],[23]. However, in order to test the role of Lcn2 in the upper respiratory tract we needed to develop a nasal colonization model. To do this, C57BL/6 mice were inoculated intranasally with increasing concentrations of K. pneumoniae in 10 µL of PBS. To facilitate recovery from the non-sterile nasopharynx, the strain KPPR1, a rifampin resistant-derivative of K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 was used. Mice were sacrificed at day 1, 3, 7, or 14 and colonization was measured by tracheal cannulation and quantitative culture of nasopharyngeal lavage, as previously described [24]. Using 2×106 cfu as the inoculum, sustained colonization at >5×103 cfu/ml was observed for at least 7 days (Figure 1). Whereas instillation under anesthesia causes pneumonia [22],[23], inoculation of awake mice caused nasal carriage without systemic disease. K. pneumoniae was recovered only sporadically and at low density (<7×102 cfu/organ) from the lungs and spleen (data not shown). Furthermore, all mice appeared healthy throughout the course of the experiment despite a 1000× larger inoculum compared to the pneumonia model.

Figure 1. K. pneumoniae colonizes the nasopharynx of C57BL/6 mice.

C57BL/6 mice were inoculated intranasally with 2×106 cfu of an overnight LB culture of KPPR1 in 10 µL PBS. At each time point, 5 mice were sacrificed, nasopharyngeal lavage was performed, and lavage fluid was plated for quantitative culture. Colony forming unit (cfu) counts are shown as a scatter plot where the bar represents the median; the dashed line is the lower limit of detection (20 cfu/ml).

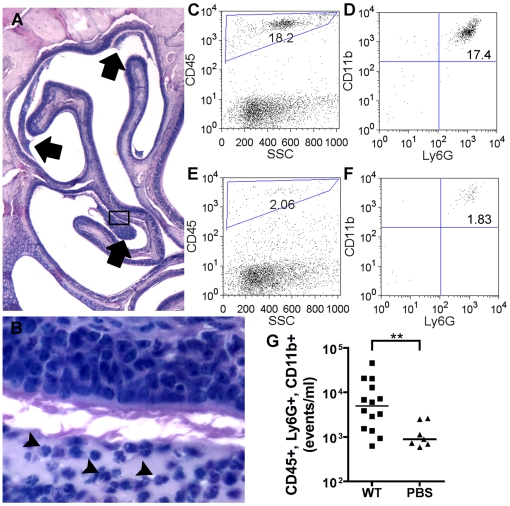

To characterize the cellular response to K. pneumoniae nasal colonization, mice were inoculated as above and sacrificed at day 1 and day 3, skulls were dissected and decalcified, and saggital sections of the nasopharynx were examined by histology. On day 1, an acute inflammatory infiltrate in the paranasal airspaces was apparent in hematoxylin-eosin stained sections (Figure 2A). The lumen of the nasopharynx harbored dense clusters of neutrophils, as judged morphologically by high power light microscopy (Figure 2B). On day 3, an infiltrate of similar density and location was seen. No neutrophils were seen in the lumens of unchallenged mice (data not shown).

Figure 2. K. pneumoniae colonization elicits an acute inflammatory infiltrate.

Mice colonized with wild-type K. pneumoniae KPPR1 were sacrificed at day 1 post-inoculation. Inflammatory infiltrates are seen adjacent to the turbinates of the nasopharynx (A, 20×, arrows) containing neutrophils (B, 600×, arrowheads). To enumerate the neutrophil influx, mice were sacrificed at day 3 post-inoculation for nasopharyngeal lavage, and 100 µL of lavage fluid was analyzed by flow cytometry. Neutrophils (CD45+, Ly6G+ and CD11b+) from a representative KPPR1 (C, D) or PBS mock-colonized (E, F) mouse lavage sample are shown. Compiled neutrophil counts are shown as a scatter plot; the bars represent median numbers of CD45+, Ly6G+, CD11b+ events/ml for each animal (G). p<0.01 by Mann-Whitney test.

To directly quantify the neutrophil influx in response to K. pneumoniae, flow cytometry was performed on nasal washes of KPPR1-colonized and PBS mock-colonized mice. Activated neutrophils were identified by the following markers: CD45 (pan-hematopoietic marker), Ly6G (Granulocyte receptor-1) and CD11b (Mac-1). Aliquots of 100 µL/animal were stained with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies, and total numbers of neutrophils were compared (Figure 2C–F). On day 3, a marked increase in the percentage of total events that were CD45+, CD11b+, Ly6G+ neutrophils was seen in colonized versus uncolonized mice (Figure 2G, p<0.01).

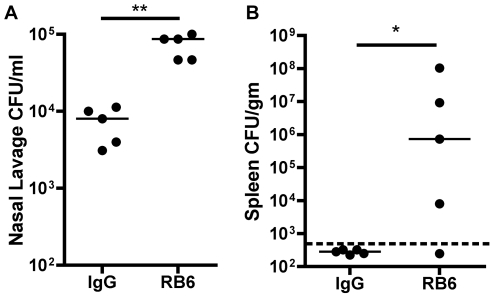

Neutrophils inhibit colonization and prevent bacteremia by wild-type K. pneumoniae

To determine if neutrophils are protective during K. pneumoniae colonization, mice were depleted of neutrophils by the Ly6G-specific antibody RB6-8C5. One day prior to K. pneumoniae inoculation, mice were injected intraperitoneally with RB6-8C5 or control Rat IgG. Mice were inoculated intranasally with KPPR1 and subsequently sacrificed for nasopharyngeal lavage and quantitative spleen culture. At day 1 post-inoculation, RB6-8C5-treated mice had significantly greater colonization density compared to control-treated mice (p<0.01, Figure 3A). Four out of five RB6-8C5-treated mice were bacteremic, as judged by recovery of K. pneumoniae from the spleen, compared to none (0/5) of the control-treated mice (p<0.05, Figure 3B). By day 2, RB6-8C5-treated mice colonized with K. pneumoniae became moribund (data not shown). These data indicate that neutrophils control intranasal density of colonizing K. pneumoniae and prevent bacteremia and sepsis.

Figure 3. Neutrophils inhibit K. pneumoniae colonization and prevent bacteremia.

Mice were treated with RB6-8C5 rat mAb to murine Ly6G or control rat IgG one day prior to inoculation with 2×106 cfu of wild-type K. pneumoniae KPPR1 were sacrificed at day 1 post-inoculation. Nasopharyngeal lavage cfu/ml (A) and spleen cfu/gm (B) are shown as a scatter plot with the bar at the median; dashed line represents lower limit of detection. ** p<0.01 by Mann-Whitney test; * p<0.05 by Fisher's Exact Test for presence of detectable bacteria in the spleen.

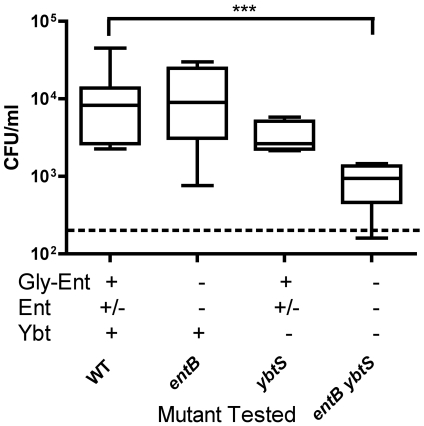

Glycosylated-enterobactin or yersiniabactin are sufficient to support K. pneumoniae colonization

By exploiting isogenic siderophore mutants, K. pneumoniae can be used to evaluate two non-mutually exclusive functions of Lcn2: iron sequestration and pro-inflammatory activation. K. pneumoniae KPPR1 makes glycosylated Ent (Gly-Ent) and Ybt, neither of which Lcn2 is predicted to bind [11]. Constructing mutants in the iroA locus will allow study of the effects of Lcn2 binding to non-glycosylated Ent (Ent). However, whether Ybt can compensate for the loss of Ent bound by Lcn2 is unknown.

The role of Ybt and Gly-Ent in a mouse model of K. pneumoniae pneumonia was tested previously [22]. To determine the requirement of each siderophore during nasal colonization, cfu recovery of single and double mutants was compared to wild-type K. pneumoniae on day 3 post-inoculation (Figure 4). As determined by the density of ybtS and entB mutants, Gly-Ent or Ybt were sufficient to support K. pneumoniae nasal colonization. In contrast, the entB ybtS mutant strain lacking both siderophores was deficient in colonization (p<0.001 at day 3). These data indicate that siderophores are required for persistence on the nasal mucosa, but either Gly-Ent or Ybt is sufficient to scavenge the necessary iron. This is in contrast to the pneumonia model where the ybtS mutant had a distinct disadvantage compared to the entB mutant at later stages of infection [22].

Figure 4. K. pneumoniae requires enterobactin or yersiniabactin, but not both, to colonize the nasopharynx efficiently.

Colonization density was determined in C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 per group) at day 3 after intranasal inoculation with 2×106 cfu of the K. pneumoniae mutants indicated. Box and whiskers graph shows the median and interquartile ranges; the dashed line is the lower limit of detection (20 cfu/ml). Siderophores encoded by each mutant are indicated by a plus (+). *** p<0.001 by Mann-Whitney test.

The iroA locus protects against lipocalin 2-mediated growth inhibition

To generate K. pneumoniae producing unmodified Ent that can be bound by Lcn2, the iroA locus was disrupted in the wild type and the ybtS mutant. The resulting iroA ybtS mutant is predicted to depend on unmodified Ent to acquire iron and therefore to be susceptible to Lcn2-mediated interference with iron acquisition. In contrast, the iroA mutant is predicted to make unmodified Ent, which may initiate Lcn2-mediated inflammation, but to be able to acquire iron using Ybt.

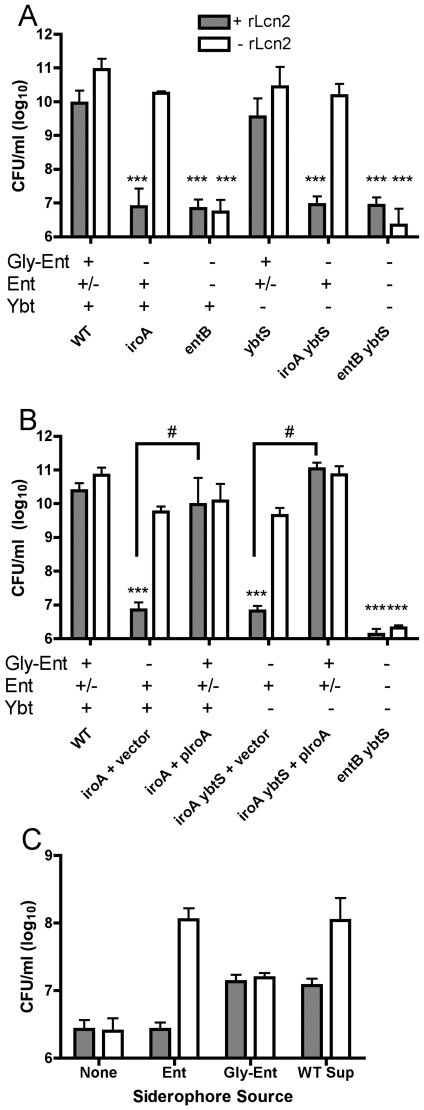

To test the requirement of the iroA locus for growth in the presence of Lcn2, wild-type and siderophore mutant K. pneumoniae were grown in serum from Lcn2−/− mice with or without recombinant murine Lcn2 (rLcn2, 1.6 µM). Serum was chosen as a growth medium where Ent is required to obtain iron from transferrin [25],[26]. Production of either Ent or Gly-Ent was sufficient for maximal growth in Lcn2−/− serum (Figure 5, white bars). In contrast to colonization, Ybt was unable to support growth in mouse serum in vitro (see entB mutant). Addition of rLcn2 (shaded bars) inhibited Ent-producing K. pneumoniae (iroA, iroA ybtS mutants) by approximately 1000-fold compared to Gly-Ent-producing K. pneumoniae (wild type, ybtS mutant).

Figure 5. The iroA locus protects against growth inhibition by lipocalin 2.

Overnight growth in Lcn2-deficient mouse serum with or without 1.6 µM recombinant Lcn2 was determined for the K. pneumoniae mutants indicated (A). For complementation studies, growth in serum was determined for the iroA and iroA ybtS mutant transformed with the vector control (pACYC184) or pIroA (pACYC184::iroBCDN) (B). Mean±SEM for at least three independent experiments is shown as log10 CFU/ml. Siderophores encoded by each mutant are indicated by a plus (+). *** p<0.001 comparing each condition to WT plus rLcn2, and # p<0.001 comparing pIroA to vector control, as determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test. To determine if wild-type K. pneumoniae produces Lcn2-resistant and sensitive Ent, growth of the entB mutant in serum with or without 5 µM recombinant Lcn2 was compared between vehicle control, 16 nM of purified Ent or Gly-Ent (Salmochelin S4), or wild-type culture supernatant (1∶640 dilution) (C). Mean ± standard deviation for two independent experiments is shown as log10 CFU/ml.

To confirm that Lcn2-sensitivity of the iroA and iroA ybtS mutants is attributable to disruption of the iroA locus, complementation studies were performed. The mutants contain a disruption in the initial gene iroB that may have polar effects on the rest of the operon. Transformation with plasmids containing iroB from K. pneumoniae KPPR1 or _E. coli χ_7122 was toxic and inhibited growth even in the absence of Lcn2 (data not shown). Therefore polar effects could not be ruled out. Instead, the mutants were transformed with a plasmid pIroA (pIJ137) encoding iroBCDN from _E. coli χ_7122. In E. coli, this construct confers the ability to produce Gly-Ent as determined by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry [27]. Transformation with pIroA, but not the control plasmid, rescued growth of the iroA and iroA ybtS mutants in Lcn2-containing serum (Figure 5B). This indicates that the iroA locus is required to prevent Lcn2-dependent growth inhibition.

In E. coli and Salmonella strains encoding iroA, only a subset of enterobactin is glycosylated [20],[27]. Comparison of wild-type K. pneumoniae growth in the presence or absence of Lcn2 suggested that it produces a mixture of Lcn2-resistant and sensitive Ent (Figure 5A). To examine this possibility in more detail, culture supernatants from the wild type grown in iron-limited M9 broth were used to stimulate growth of the entB mutant in Lcn2-containing serum. As controls, purified Ent and Gly-Ent (Salmochelin S4) were used to stimulate growth. Gly-Ent supported identical levels of growth in the presence and absence of Lcn2, whereas Ent only stimulated growth in the absence of Lcn2. Culture supernatant from the wild type was partially sensitive to Lcn2, indicating that K. pneumoniae secretes a mixture of Lcn2-sensitive and resistant Ent (Figure 5C).

The iroA locus is required for colonization by enterobactin-dependent K. pneumoniae

To test whether the iroA locus is required for bacterial colonization, C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with 2×106 cfu of K. pneumoniae producing different combinations of Gly-Ent, Ent and Ybt. To enhance siderophore expression prior to inoculation, K. pneumoniae was grown in the presence of the iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl (200 µM). At this concentration of chelator, transcription of Ent-synthesis enzymes is increased ∼8 fold compared to rich media, based on a transcriptional GFP fusion to entC (data not shown).

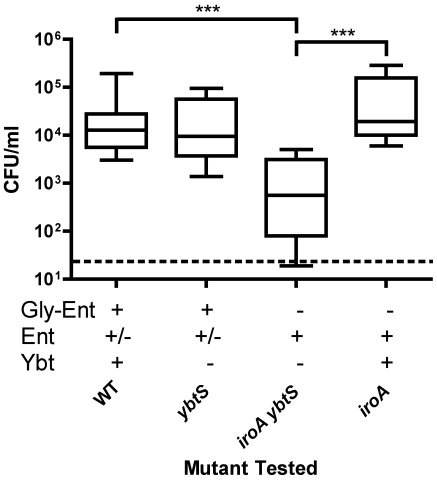

Gly-Ent-producing K. pneumoniae colonized efficiently with or without producing Ybt (Figure 6, compare wild type and ybtS). In contrast, K. pneumoniae producing only Ent (iroA ybtS mutant) was deficient for colonization (p<0.001 at day 3). This defect in colonization could be due to a defect in iron acquisition, or through additional host defenses including pro-inflammatory responses triggered by Ent-Lcn2 signaling. As shown above, Ybt is able to support colonization in the absence of Ent (Figure 4). To test for defects in colonization independent from iron acquisition, carriage of K. pneumoniae making Ent plus Ybt (iroA mutant) was examined. The ability of the iroA mutant to produce Ybt restored maximal colonization. These data indicate that iron sequestration is an important host mechanism for inhibiting colonization of Ent-dependent K. pneumoniae.

Figure 6. Enterobactin-dependent K. pneumoniae is defective in colonization.

Colonization density at day 3 after intranasal inoculation with 2×106 cfu of the K. pneumoniae mutants indicated was determined in C57BL/6 mice (n≥5 mice per group). Box and whiskers graph shows the median and interquartile ranges; the dashed line is the lower limit of detection (20 cfu/ml). Siderophores encoded by each mutant are indicated by a plus (+). *** p<0.001 as determined by Kruskall-Wallis Test with Dunn's post test.

Mucosal lipocalin 2 inhibits colonization of K. pneumoniae dependent on unmodified enterobactin

To determine whether Lcn2 is required to inhibit Ent-dependent bacteria, colonization of Lcn2-producing (Lcn2+/+) and Lcn2-deficient littermate mice (Lcn2−/−) was compared (Figure 7A). Wild-type K. pneumoniae producing Gly-Ent and Ybt maximally colonized both Lcn2+/+ and Lcn2−/− mice. Conversely, the iroA ybtS mutant K. pneumoniae dependent on Ent was significantly inhibited in Lcn2+/+ mice (p<0.01). This inhibition was absent in Lcn2−/− mice and was similar to the defect seen in the entB ybtS mutant. Therefore, Lcn2 is required to inhibit Ent-dependent strains and acts predominantly by interfering with iron acquisition.

Figure 7. Mucosal lipocalin 2 is required to inhibit colonization by enterobactin-dependent K. pneumoniae.

Colonization density of Lcn2+/+ (shaded symbols) and Lcn2−/− mice (open symbols) on day 3 after intranasal inoculation with 2×106 cfu of the K. pneumoniae mutants indicated (A). Box and whiskers graph shows the median and interquartile ranges for ≥10 mice per group; the dashed line is the lower limit of detection (20 cfu/ml). Siderophores encoded by each mutant are indicated by a plus (+). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, ns p>0.05 as determined by Kruskall-Wallis Test with Dunn's post test. To remove the contribution of neutrophil-produced Lcn2, colonization density on day 1 was determined in Lcn2+/+ (n = 6) and Lcn2−/− mice (n = 8) treated with RB6-8C5 rat mAb to murine Ly6G one day prior to inoculation with 2×106 cfu of iroA ybtS mutant K. pneumoniae (B). * p<0.05 as determined by Mann-Whitney Test.

Two potential sources of Lcn2 in the nasal lumen are the mucosa and infiltrating neutrophils. To determine whether mucosal Lcn2 is able to inhibit Ent-dependent K. pneumoniae colonization, mice were depleted of neutrophils using the RB6-8C5 antibody one day prior to inoculation. Despite RB6-8C5 treatment, colonization was significantly inhibited in Lcn2+/+ compared to Lcn2−/− mice at day 1 (p<0.05, Figure 7B). These data indicate that mucosal sources of Lcn2 are sufficient to provide its antibacterial effects during colonization.

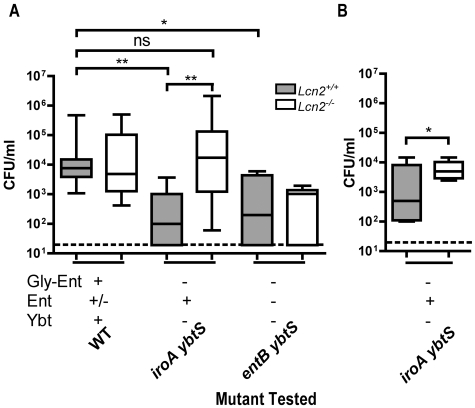

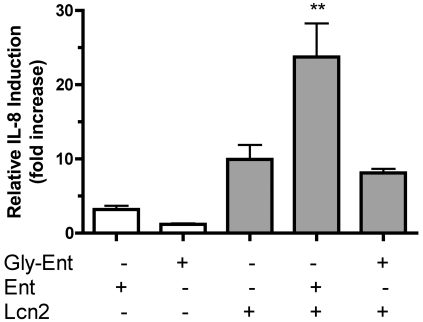

Lipocalin 2 induces IL-8 release from cultured respiratory cells in response to unmodified but not glycosylated enterobactin

Although iron sequestration is the predominant effect observed during colonization, Lcn2 may have additional pro-inflammatory effects that are blocked by glycosylation of Ent. In cultured respiratory cells, the combination of Lcn2 and aferric Ent induces synergistic IL-8 release [8]. To determine whether glycosylation of Ent prevents this synergistic activation of chemokine release, A549 human respiratory cells were incubated with combinations of purified Ent, Gly-Ent, or rLcn2. Whereas co-incubation of Ent with Lcn2 induced IL-8 release greater than 20-fold, co-incubation of Gly-Ent and Lcn2 did not stimulate IL-8 release above the level induced by Lcn2 alone (Figure 8). No significant cellular cytotoxicity, as measured by LDH release, was detected for any combination of stimuli (data not shown). Consistent with the observation that expression of the iroA locus prevents Lcn2 binding, Lcn2 does not stimulate IL-8 release from cultured respiratory cells in response to Gly-Ent.

Figure 8. Lipocalin 2 does not stimulate IL-8 release from A549 respiratory cells in response to glycosylated enterobactin.

IL-8 release from cultured A549 respiratory cells was measured by ELISA after overnight stimulation with 50 µM Ent or Gly-Ent (Salmochelin S4) and/or 25 µM recombinant Lcn2 (shaded bars). Mean±SEM of fold-increase above vehicle control from at least three independent experiments is shown. ** p<0.01 comparing Ent-Lcn2 to all other stimuli as determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test.

Enterobactin-producing K. pneumoniae elicit a lipocalin 2-dependent increase in neutrophil influx

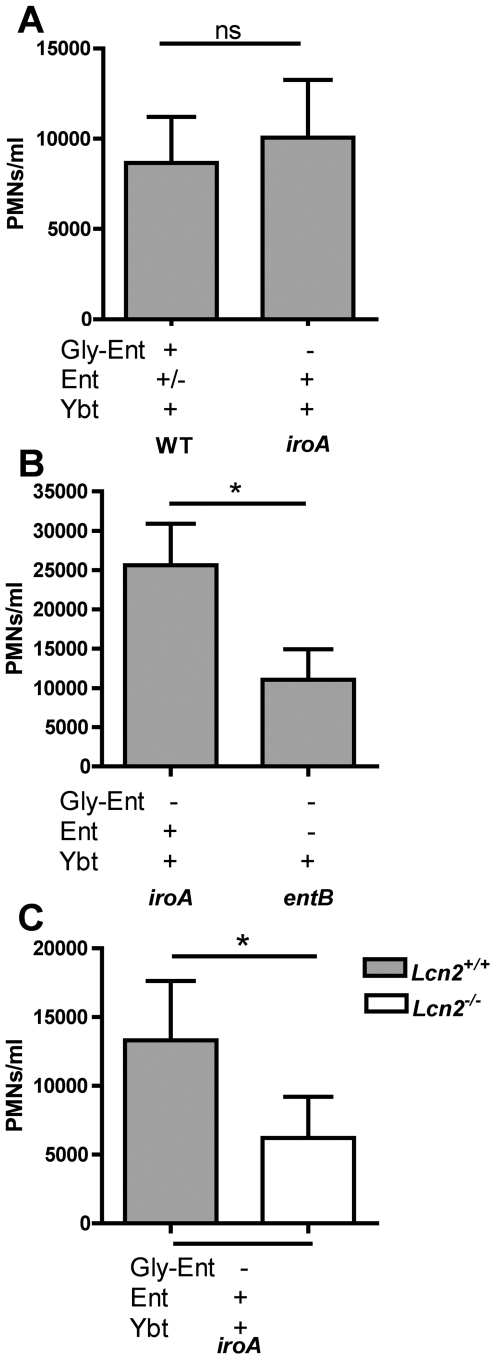

The induction of the neutrophil chemoattractant IL-8 in vitro suggests that Ent release by colonizing bacteria may stimulate neutrophil recruitment during infection. To measure the effect of Ent on neutrophil influx, flow cytometry was performed on nasal lavage fluid from mice colonized with wild type, iroA and entB mutants. The iroA mutant is predicted to produce Ent that interacts with Lcn2, is not predicted to be susceptible to iron sequestration since it makes Ybt, and colonizes similarly to the wild type (Figure 7). In contrast, the entB mutant produces no Ent but also colonizes similarly to the wild type (Figure 4). Comparison of the wild type and iroA mutant demonstrated no difference in neutrophil influx (Figure 9A). This suggests that the subset of unmodified Ent produced by the wild type is sufficient to induce a robust inflammatory response. To measure cellular inflammation directly attributable to unmodified Ent, neutrophil counts were compared between iroA and _entB_-colonized mice. The iroA and entB mutants achieved a similar level of colonization (data not shown), but the iroA mutant elicited significantly more neutrophils (Figure 9B). To determine if the neutrophil influx in response to Ent-producing Klebsiella is Lcn2-dependent, Lcn2+/+ and Lcn2−/− littermates were colonized with iroA mutant K. pneumoniae. Lcn2+/+ mice had a significantly greater neutrophil influx than Lcn2−/− littermates in response to the Ent-producing iroA mutant (Figure 9C, p<0.05 Wilcoxon matched pair test). The lower number of neutrophils in Lcn2−/− mice could not be attributed to decreased colonization density (data not shown). Concurrent with its predominant iron sequestration effect, Lcn2 also appears to induce greater neutrophil influx in response to bacteria producing unmodified Ent.

Figure 9. Lipocalin 2 promotes increased neutrophil influx in response to enterobactin-producing K. pneumoniae.

Intraluminal neutrophil counts (PMNs) were measured by flow cytometry of 100 µL nasopharyngeal lavage fluid on day 3 after intranasal inoculation of C57BL/6 mice with 2×106 cfu of the following combinations of K. pneumoniae: wild-type KPPR1 vs. iroA mutant (A), or iroA mutant vs. entB mutant (B). *p<0.05 by the Mann-Whitney test. To determine if neutrophil influx to Ent-producing strains is Lcn2-dependent, Lcn2+/+ and Lcn2−/− littermates were colonized with 2×106 cfu of iroA mutant K. pneumoniae (C). * p<0.05 as determined by the Wilcoxon matched pair test. Data points represent CD45+, Ly6G+, CD11b+ events and dotted lines connect littermates (n≥5 per group). Siderophores encoded by each mutant are indicated by a plus (+).

Discussion

This work establishes an animal model to study the function of Lcn2 in the upper respiratory tract. As well as being an important human pathogen, K. pneumoniae is a tractable model organism that colonizes the nasopharynx and can be genetically manipulated to produce siderophore mutants that do or do not interact with Lcn2. Colonization with wild-type K. pneumoniae persists for at least seven days, and induces a robust acute inflammatory response. The fact that intranasal inoculation of awake mice produces colonization, and not pneumonia, is likely because the mice do not aspirate nasopharyngeal contents into their lungs [28].

Similarly to pneumonia, persistence of K. pneumoniae in the upper respiratory tract requires ongoing iron acquisition [22]. Either Gly-Ent or Ybt are required for maximal colonization. This confirms that the nasal mucosa is an iron-limited environment for bacteria, presumably due to the high lactoferrin concentration in nasal secretions [29],[30]. Furthermore, this suggests that colonization by K. pneumoniae requires bacterial replication, and not simply persistence of the originally inoculated organisms. Having established the need for K. pneumoniae to acquire iron in the nasopharynx, this model can be exploited to examine how host Lcn2 and the bacterial iroA locus affect the level of colonization.

By using Lcn2−/− mice and K. pneumoniae siderophore mutants, this study demonstrates that Lcn2 inhibits nasopharyngeal colonization by bacteria producing unmodified Ent. Although a seemingly narrow target for antimicrobial activity, Ent is produced by many members of the gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae family [1]. Therefore, Lcn2 may contribute to the tropism of enteric commensals for the gut rather than the respiratory tract. The respiratory tract secretes Lcn2 at basal levels and rapidly upregulates Lcn2 expression during colonization [4],[6]. In contrast, the large intestine does not express basal Lcn2 despite the presence of huge numbers of colonizing bacteria [4]. However, Salmonella infection induces Lcn2 production in the intestine, and the ability to utilize Gly-Ent confers a competitive advantage over an iroN mutant during intestinal inflammation [31]. Therefore, pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae such as Salmonella and K. pneumoniae can use Gly-Ent to obtain iron in an otherwise restricted environment.

In the respiratory tract, Lcn2 may provide selective pressure for Ent-independent methods of iron acquisition. Many clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae produce either aerobactin or Ybt [9],[10] in addition to Ent. Lcn2 binds bacillibactin of Bacillus anthracis, but B. anthracis also produces the unusual siderophore petrobactin that Lcn2 cannot bind [32]. Likewise, pathogens such as S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae appear to acquire iron in the respiratory tract without producing siderophores [33],[34].

In the pathogenic K. pneumoniae strain used here, either Gly-Ent or Ybt can support colonization of the nasopharynx. However, Ybt cannot support growth in serum. This defect could be due to an inability of Ybt to strip iron off of transferrin, or a serum component other than Lcn2 that inhibits Ybt-mediated iron acquisition. In contrast, the iroA locus supports robust growth in the presence of Lcn2. Therefore, Ybt and Gly-Ent are not functionally redundant in K. pneumoniae, and likely reflect adaptation to growth in the disparate environments of the respiratory, urinary, and intestinal tracts and the bloodstream.

K. pneumoniae nasal colonization induces a robust inflammatory response characterized by a rapid influx of neutrophils. Neutrophils limit colonization of wild-type K. pneumoniae and prevent hematogenous spread to the spleen. Despite producing Lcn2, neutrophils likely inhibit K. pneumoniae by predominantly Lcn2-independent mechanisms based on the following observations. In the presence of neutrophils, colonization by wild-type K. pneumoniae is the same in Lcn2+/+ and Lcn2−/− mice. In contrast, depletion of neutrophils causes a 10-fold increase in wild-type colonization. Finally, mucosal Lcn2 is able to inhibit colonization of iroA ybtS K. pneumoniae despite depletion of neutrophils. Together, these data indicate that iron sequestration by mucosal Lcn2 is complementary to the antimicrobial actions of neutrophils.

Lcn2 also appears to induce a pro-inflammatory response from respiratory cells when bound to Ent. In vitro, Ent combined with Lcn2 causes a synergistic release of IL-8 from human respiratory cells, but Gly-Ent combined with Lcn2 does not. IL-8 is a neutrophil attracting chemokine, suggesting that signaling by Ent-Lcn2 leads to the recruitment of neutrophils. Accordingly, Ent-producing K. pneumoniae induce nasopharyngeal neutrophil influx in an Lcn2-dependent manner.

The potential signaling pathway between Lcn2, Ent and neutrophil recruitment is unknown. There is no direct IL-8 (CXCL-8) homologue in the mouse [35],[36], although there are several CXC chemokines such as Mip-2, KC, and LIX that have been shown to be induced by K. pneumoniae respiratory infections [37]. Studies to determine the effects of Ent and Lcn2 on murine CXC chemokine production from the murine respiratory mucosa are underway.

The data from this study suggest the following model in which Lcn2 monitors iron utilization by bacteria and activates the immune response when iron stores become depleted: At low bacterial density, secreted Ent binds Fe and Lcn2 in turn binds Fe-Ent to prevent delivery of iron to bacteria. The Fe-Ent-Lcn2 complex is internalized by respiratory epithelial cells [8], and could serve as both a signal of controlled colonization and a mechanism of iron recycling. We hypothesize that as bacterial density increases Lcn2 becomes a pro-inflammatory signal. When bacterial growth outpaces Fe availability, an increased proportion of Ent will be aferric. This aferric Ent-Lcn2 complex could be internalized and serve as a signal of uncontrolled bacterial replication to the respiratory epithelium. In vitro, respiratory cells respond to Ent-Lcn2 by induction of chemokines, an effect that could explain the increased neutrophil influx seen in response to Ent-producing K. pneumoniae in vivo.

The combined data from neutrophil and bacterial counts are consistent with the hypothesis that Lcn2 has a continuum of iron-sequestering and pro-inflammatory activities. Specifically, Ent-producing K. pneumoniae elicit neutrophils in Lcn2+/+ mice without showing a defect in colonization. The bacterial density of colonization by K. pneumoniae is relatively low (∼1e4 CFU/ml) compared to counts from the pneumonia model [23]. If Fe is not depleted during colonization, then Lcn2 may bind primarily Fe-Ent. The small percentage of aferric Ent-Lcn2 could be sufficient to produce a modest increase in the number of neutrophils elicited by K. pneumoniae colonization. Whereas total depletion of neutrophils leads to increased bacterial numbers (Figure 3), this incremental increase in neutrophils is not sufficient to affect the density of colonizing organisms. If a perturbance in the microenvironment caused a large increase in bacterial levels, we would predict a greater pro-inflammatory response elicited by Ent-Lcn2. Alternatively, if K. pneumoniae reaches the lower respiratory tract where it can replicate to high numbers (>109 CFU/gm) [22], there may be a dramatic increase in Ent-Lcn2 formation with a more significant effect of Lcn2 on the immune response. Consistent with this model, Chan and colleagues report that Lcn2 limits growth of K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 (the parent strain of our wild type KPPR1) during pneumonia [38]. Since Ent is dispensable for growth during pneumonia from KPPR1 [22], iron sequestration by Lcn2 cannot account for the observed growth inhibition. This suggests that Lcn2 controls bacterial growth by an additional mechanism such as neutrophil recruitment. Whether Ent production stimulates Lcn2-dependent inflammation during pneumonia remains to be determined. Studying the pro-inflammatory effects of Lcn2 on the mucosal surface could reveal a new paradigm of innate immune signaling in response to bacterial metabolism.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and media

KPPR1, a rifampin-resistant derivative of K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae (ATCC 43816), with a type 1 O antigen and type 2 capsule was used as the wild-type strain in these studies [23]. Measurement of entC expression was performed using KPPR1 harboring the entC promoter-GFP reporter plasmid pE2 (VK096) [22]. Siderophore mutant strains of KPPR1 contain in-frame deletions of the enterobactin synthesis gene entB encoding 2,3-dihydro-2,3 dihydroxybenzoate synthase (VK087), the yersiniabactin synthesis gene ybtS encoding salicylate synthase (VK088) or both (VK089) [22]. Unless otherwise noted, strains were grown overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) media, either at 30°C on agar or at 37°C shaking in broth. Media was supplemented with rifampin (30 µg/ml) or kanamycin (50 µg/ml) as needed. To stimulate siderophore production strains were grown overnight in LB broth supplemented with 200 µM 2,2′-dipyridyl (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium), back diluted to OD600 0.1, and grown an additional two hours to mid-logarithmic phase.

iroA mutant construction

PCR primers specific for conserved regions of the iroB glycosylase gene (iroBfor 5′-GTGATGCAAACCGTCGGCTTC, iroBrev 5′-ACCATCGGTTTGACGGTGCCGAG) were constructed by comparing DNA sequences from Salmonella typhimurium LT2, E. coli CFT073, E. coli UT189, and K. pneumoniae virulence plasmid pLVPK. An internal 0.3 kb iroB PCR fragment was amplified, sequenced, and found to be 96% identical to iroB from pLVPK. This fragment was then cloned into the TA-based PCR cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to a kanamycin-resistant derivative of the λ_pir_-dependent suicide vector pGP704 [39]. This iroB suicide vector was transformed into E. coli strain BW20767 (ATCC 47084, RP4-2tet::Mu-1kan::Tn7-integrant uidA(ΔMlu1)::pir+ recA1 creB510 leu-63 hsdR17 endA1 zbf-5 thi) and subsequently conjugated into wild-type (KPPRI) and ybtS mutant (VK088) K. pneumoniae to generate iroA and iroA ybtS mutants. Integration of the suicide vector into the iroB gene was confirmed by generation of a novel PCR product using one primer on the vector (pGP704 MCS Pst>Xba 5′-GGTCGACGGATCCCAAG) and an iroB primer 5′ of the insertion site (iroBORF for 5′ ATGCGTATTTTATTTATAGGTCC). For complementation studies, each mutant was transformed by electroporation with either pACYC184::iroB (pIJ53) or pACYC184::iroBCDN (pIJ137, referred to as pIroA in this study) containing iroA genes from E. coli χ7122 [27]. The vector pACYC184 was transformed as a negative control.

Nasal colonization model

All animals were handled in strict accordance with good animal practice as defined by the relevant national and/or local animal welfare bodies, and all animal work was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Assurance # A3079-01). For nasal colonization experiments, six to eight week-old C57BL/6 (Jackson Labs, Jackson, ME) mice were atraumatically inoculated intranasally without anesthesia with 2×106 cfu of K. pneumoniae. LB broth grown cultures were centrifuged, resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and 10 µL of the suspension was applied equally to both nares. To determine colonization density, mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation, the trachea was exposed and cannulated, 200 µL PBS was instilled, and lavage fluid was collected from the nares. Aliquots of lavage fluid were plated on LB agar supplemented with rifampin with a lower limit of detection of 20 cfu/ml. To measure lung or spleen infection, the organ was removed, weighed, homogenized in 500 µL PBS, plated on LB agar supplemented with rifampin, and quantified as cfu/gm. To examine the infection by histology, skulls were removed by decapitation, fixed by 48 h incubation in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and decalcified for 48 h in Cal-EX decalcifying solution (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). Saggital sections of the nasal cavity were paraffin embedded and processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

To deplete neutrophils, 145 µg of the rat anti-mouse IgG2B mAb RB6-BC5 directed against Ly-6G on the surface of mouse granulocytes was injected intraperitoneally 24 h prior to intranasal bacterial inoculation. This dose has been shown previously to result in peripheral blood neutropenia for at least 96 h (<50 granulocytes/ml, [6]). Intraperitoneal injection of 145 µg of rat total IgG was used as a control.

Lipocalin 2-deficient mice

To ensure similar endogenous nasal flora, Lcn2−/− mice [3] (provided by Shizuo Akira via Alan Aderem) and Lcn2+/+ littermates were compared. Offspring from heterozygous breeding pairs were genotyped using DNA extracted from tail samples with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). For each mouse, paired PCR amplifications were performed with a common primer (common 5′-CACATCTCATGCTGCTGAGATAGCCAC) and a primer specific for either the intact Lcn2 locus (wild-type 5′-GTCCCTCTCACTTTGACAGAAGTCAGG) or the neomycin-cassette disrupted Lcn2 locus (neo1500 5′-ATCGCCTTCTATCGCCTTCTTGACGAG).

Recombinant lipocalin 2 production

Recombinant mouse lipocalin 2 (rLcn2) was purified as previously described [40]. Briefly, E. coli strain BL-21 expressing plasmid-encoded mouse lipocalin 2 as a glutathione _S_-transferase fusion protein (a gift from J. Barasch) was grown to mid-logarithmic phase in Terrific Broth supplemented with 50 µM ferrous sulfate and induced with 0.2 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested and lysed by sonication, and rLcn2 was purified on a Glutathione Sepharose 4B bead column (GE Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) followed by digestion with human thrombin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and elution in PBS. Purified rLcn2 was quantified using the Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and siderophore-binding activity was confirmed by incubation with Fe-Ent followed by measurement of absorbance at 340 nm.

Serum growth assay

Bacterial growth using mouse serum as an iron source was assayed as previously described [3]. RPMI supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated Lcn2−/− -mouse serum was inoculated with 1×103 cfu/ml of an overnight culture of K. pneumoniae and incubated an additional 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO2 in 96-well plates. Bacterial growth was quantified by plating serial dilutions on LB agar. Where indicated, RPMI was supplemented with 1.6 µM recombinant Lcn2. To determine if the wild type produces Lcn2-resistant and sensitive Ent, sterile-filtered culture supernatants were collected from wild-type KPPR1 grown overnight in iron-limited M9 minimal media. RPMI supplemented with 3% heat-inactivated mouse serum was inoculated with 5×103 cfu/ml of an overnight culture of entB mutant K. pneumoniae, supplemented with 4-fold serial dilutions of purified Ent or Gly-Ent (Salmochelin S4; EMC microcollections, Tuebingen, Germany) or culture supernatant, incubated overnight and plated for bacterial cfu. The dilution of culture supernatant (1∶640) where Lcn2-resistant growth matched that of Gly-Ent was used for comparisons.

Quantification of neutrophils by flow cytometry

Antibody staining was performed at 4°C in 96-well plates using cells from 100 µL of nasal lavage fluid resuspended in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). For each mouse, cells were spun at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes, washed once with 200 µL PBS+BSA, centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 2 minutes, resuspended in the same volume and blocked for 10 minutes. Cells were spun as above, resuspended in 25 µL of a 1∶200 dilution of Fc Block (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and incubated an additional 10 minutes. Then, four-color staining was performed for 30 minutes by addition of 25 µL of an antibody mixture of fluorophore-conjugated Ly6G, CD11b, CD4, and CD45 antibodies (BD Pharmingen) at the following final concentrations: FITC 1∶200, PE 1∶300, PerCP 1∶100, APC 1∶300. Cells were washed twice, centrifuged and fixed by resuspension in 300 µL PBS+BSA with 0.5% paraformaldehyde.

For fluorophore compensation, mouse splenocytes were harvested. Spleens were homogenized by passage through a sterile screen, washed in 15 ml RPMI, and red blood cells were lysed by resuspension in 2 ml 0.83% ammonium chloride and incubation at room temp for 2 minutes. The suspension was neutralized by addition of RPMI, incubated an additional 3 minutes, and the supernatant was removed, centrifuged, washed in RPMI and resuspended in PBS+BSA. 200 µL aliquots were blocked for 10 minutes with PBS+BSA, and individually stained with FITC, PE, PerCP, or APC-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody. Flow cytometry data was collected using a BD FACSCaliber and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). For nasal lavage fluid, the entire sample was analyzed and normalized to events per ml. Lcn2+/+ and Lcn2−/− littermates were compared pair-wise to account for potential variation in baseline neutrophil counts that may be caused by differences in the endogenous nasal flora.

Cell culture and IL-8 release assay

The human type II pneumocyte A549 cell line (ATCC CCL-185) was propagated in minimal essential medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum as described previously [8]. Near-confluent monolayers in 24-well plates were weaned from serum and antibiotics overnight. Then, A549 cells were stimulated with combinations of 50 µM purified siderophores (EMC microcollections, Tuebingen, Germany) or 25 µM lipocalin 2 overnight as indicated. Purified diglycosylated Ent (Salmochelin S4), which is the major product of IroB [41], or purified Ent was used. The next day, culture supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C or used immediately for IL-8 ELISA.

The BD OptEIA IL-8 ELISA assay (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) was performed according to the manufacturers instructions and detected using TMB substrate (Zymed/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and a Bio-Rad Model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). As a positive control for IL-8 release, cells were stimulated with 100 pg/ml of IL-1β (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ). A vehicle control was included containing the solvents for each reagent used. Cytotoxicity was evaluated by LDH measurement of supernatants using the Cytotoxicity Detection Kit Plus (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturers directions.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed and graphs were generated using Prism 4 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, Inc). For colonization data, non-parametric analysis of two groups was performed using the Mann-Whitney test and analysis of multiple groups was performed using the Kruskall-Wallis Test with Dunn's post-test. The presence or absence of splenic bacteria was analyzed by Fisher's Exact test. IL-8 ELISA data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test. Cytotoxicity data was analyzed by one-sample t-test for significant increase above the control and one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test for differences between samples. For neutrophil quantification, non-parametric analysis of mouse pairs was performed using the Wilcoxon matched pair test.

Nucleotide and protein accession numbers

Genbank nucleotide accession numbers for the iroA loci used for iroB sequence comparisons are NC_005249 (K. pneumoniae CG43 pLVPK), NC_003197 (Salmonella Typhimurium LT2), NC_004431 (E. coli CFT073), and NC_007946 (E. coli UTI89). Genbank accession number for the iroBCDN genes from χ7122 used for complementation is AF449498. The Genbank protein accession number for Lcn2 is NP_032517 for 24p3R is NP_067526.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank S. Akira for providing the Lcn2-deficient mice, J. Barasch for providing the rLcn2 GST-fusion protein construct, and C. Dozois for providing complementation plasmids. We also thank S. Dawid for fruitful scientific discussions and A. Roche for help with animal husbandry. H&E staining was performed by the Morphology Core of the Center for the Molecular Studies of Liver and Digestive Disease (Center Grant P30 DK50306).

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

This work was supported by NIH grants R01AI038446, R01AI044231 (JNW), and K08GM085612 (MAB). MAB also received support from the Postdoctoral Training Grant in Infectious Diseases (5-T32-AI007634), and the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Earhart CF. Uptake and Metabolism of Iron and Molybdenum. In: Neidhart F, editor. E coli and Salmonella: ASM Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goetz DH, Holmes MA, Borregaard N, Bluhm ME, Raymond KN, et al. The neutrophil lipocalin NGAL is a bacteriostatic agent that interferes with siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1033–1043. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, Rodriguez DJ, Holmes MA, et al. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature. 2004;432:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedl A, Stoesz SP, Buckley P, Gould MN. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in normal and neoplastic human tissues. Cell type-specific pattern of expression. Histochem J. 1999;31:433–441. doi: 10.1023/a:1003708808934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kjeldsen L, Bainton DF, Sengelov H, Borregaard N. Identification of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a novel matrix protein of specific granules in human neutrophils. Blood. 1994;83:799–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson AL, Barasch JM, Bunte RM, Weiser JN. Bacterial colonization of nasal mucosa induces expression of siderocalin, an iron-sequestering component of innate immunity. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1404–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devireddy LR, Gazin C, Zhu X, Green MR. A cell-surface receptor for lipocalin 24p3 selectively mediates apoptosis and iron uptake. Cell. 2005;123:1293–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson AL, Ratner AJ, Barasch J, Weiser JN. Interleukin-8 secretion in response to aferric enterobactin is potentiated by siderocalin. Infect Immun. 2007;75:3160–3168. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01719-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koczura R, Kaznowski A. Occurrence of the Yersinia high-pathogenicity island and iron uptake systems in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb Pathog. 2003;35:197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(03)00125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubert S, Cuenca S, Fischer D, Heesemann J. High-pathogenicity island of Yersinia pestis in Enterobacteriaceae isolated from blood cultures and urine samples: prevalence and functional expression. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1268–1271. doi: 10.1086/315831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strong R. Siderocalins. In: Akerstrom B, Borregaard N, Flower DR, Salier J, editors. Lipocalins. Austin: Landes Bioscience; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baumler AJ, Norris TL, Lasco T, Voight W, Reissbrodt R, et al. IroN, a novel outer membrane siderophore receptor characteristic of Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1446–1453. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1446-1453.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumler AJ, Tsolis RM, van der Velden AW, Stojiljkovic I, Anic S, et al. Identification of a new iron regulated locus of Salmonella typhi. Gene. 1996;183:207–213. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00560-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen YT, Chang HY, Lai YC, Pan CC, Tsai SF, et al. Sequencing and analysis of the large virulence plasmid pLVPK of Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. Gene. 2004;337:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobrindt U, Blum-Oehler G, Hartsch T, Gottschalk G, Ron EZ, et al. S-Fimbria-encoding determinant sfa(I) is located on pathogenicity island III(536) of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain 536. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4248–4256. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4248-4256.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster JW, Hall HK. Effect of Salmonella typhimurium ferric uptake regulator (fur) mutations on iron- and pH-regulated protein synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4317–4323. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4317-4323.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh PF, Lin TL, Lee CZ, Tsai SF, Wang JT. Serum-induced iron-acquisition systems and TonB contribute to virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae causing primary pyogenic liver abscess. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1717–1727. doi: 10.1086/588383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischbach MA, Lin H, Liu DR, Walsh CT. How pathogenic bacteria evade mammalian sabotage in the battle for iron. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:132–138. doi: 10.1038/nchembio771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischbach MA, Lin H, Zhou L, Yu Y, Abergel RJ, et al. The pathogen-associated iroA gene cluster mediates bacterial evasion of lipocalin 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16502–16507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604636103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crouch ML, Castor M, Karlinsey JE, Kalhorn T, Fang FC. Biosynthesis and IroC-dependent export of the siderophore salmochelin are essential for virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:971–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podschun R, Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:589–603. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawlor MS, O'Connor C, Miller VL. Yersiniabactin is a virulence factor for Klebsiella pneumoniae during pulmonary infection. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1463–1472. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00372-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawlor MS, Hsu J, Rick PD, Miller VL. Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae virulence determinants using an intranasal infection model. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:1054–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCool TL, Weiser JN. Limited role of antibody in clearance of Streptococcus pneumoniae in a murine model of colonization. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5807–5813. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5807-5813.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Relman DA, Falkow S. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. In: Mandell GL, editor. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yancey RJ, Breeding SA, Lankford CE. Enterochelin (enterobactin): virulence factor for Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1979;24:174–180. doi: 10.1128/iai.24.1.174-180.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caza M, Lepine F, Milot S, Dozois CM. Specific roles of the iroBCDEN genes in virulence of an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli O78 strain and in production of salmochelins. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3539–3549. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00455-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elidemir O, Fan LL, Colasurdo GN. A novel diagnostic method for pulmonary aspiration in a murine model. Immunocytochemical staining of milk proteins in alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:622–626. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9906036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raphael GD, Jeney EV, Baraniuk JN, Kim I, Meredith SD, et al. Pathophysiology of rhinitis. Lactoferrin and lysozyme in nasal secretions. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1528–1535. doi: 10.1172/JCI114329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wooldridge KG, Williams PH. Iron uptake mechanisms of pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12:325–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1993.tb00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raffatellu M, George MD, Akiyama Y, Hornsby MJ, Nuccio SP, et al. Lipocalin-2 resistance confers an advantage to Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium for growth and survival in the inflamed intestine. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:476–486. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abergel RJ, Wilson MK, Arceneaux JE, Hoette TM, Strong RK, et al. Anthrax pathogen evades the mammalian immune system through stealth siderophore production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18499–18503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607055103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao VK, Krasan GP, Hendrixson DR, Dawid S, St Geme JW., 3rd Molecular determinants of the pathogenesis of disease due to non-typable Haemophilus influenzae. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;23:99–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tai SS, Lee CJ, Winter RE. Hemin utilization is related to virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5401–5405. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5401-5405.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeyaseelan S, Manzer R, Young SK, Yamamoto M, Akira S, et al. Induction of CXCL5 during inflammation in the rodent lung involves activation of alveolar epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:531–539. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0063OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi Y. Neutrophil infiltration and chemokines. Crit Rev Immunol. 2006;26:307–316. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v26.i4.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Standiford TJ, Tsai WC, Mehrad B, Moore TA. Cytokines as targets of immunotherapy in bacterial pneumonia. J Lab Clin Med. 2000;135:129–138. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2000.103196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan YR, Liu JS, Pociask DA, Zheng M, Mietzner TA, et al. Lipocalin 2 is required for pulmonary host defense against Klebsiella infection. J Immunol. 2009;182:4947–4956. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller VL, Mekalanos JJ. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2575-2583.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J, Goetz D, Li JY, Wang W, Mori K, et al. An iron delivery pathway mediated by a lipocalin. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1045–1056. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00710-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischbach MA, Lin H, Liu DR, Walsh CT. In vitro characterization of IroB, a pathogen-associated C-glycosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:571–576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408463102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]