Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance (original) (raw)

Abstract

Evaluating complex interventions is complicated. The Medical Research Council's evaluation framework (2000) brought welcome clarity to the task. Now the council has updated its guidance

Complex interventions are widely used in the health service, in public health practice, and in areas of social policy that have important health consequences, such as education, transport, and housing. They present various problems for evaluators, in addition to the practical and methodological difficulties that any successful evaluation must overcome. In 2000, the Medical Research Council (MRC) published a framework1 to help researchers and research funders to recognise and adopt appropriate methods. The framework has been highly influential, and the accompanying BMJ paper is widely cited.2 However, much valuable experience has since accumulated of both conventional and more innovative methods. This has now been incorporated in comprehensively revised and updated guidance recently released by the MRC (www.mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance). In this article we summarise the issues that prompted the revision and the key messages of the new guidance.

Summary points

- The Medical Research Council guidance for the evaluation of complex interventions has been revised and updated

- The process of developing and evaluating a complex intervention has several phases, although they may not follow a linear sequence

- Experimental designs are preferred to observational designs in most circumstances, but are not always practicable

- Understanding processes is important but does not replace evaluation of outcomes

- Complex interventions may work best if tailored to local circumstances rather than being completely standardised

- Reports of studies should include a detailed description of the intervention to enable replication, evidence synthesis, and wider implementation

Revisiting the 2000 MRC framework

As experience of evaluating complex interventions has accumulated since the 2000 framework was published, interest in the methodology has also grown. Several recent papers have identified limitations in the framework, recommending, for example, greater attention to early phase piloting and development work,3 a less linear model of evaluation process,4 integration of process and outcome evaluation,5 recognition that complex interventions may work best if they are tailored to local contexts rather than completely standardised,6 and greater use of the insights provided by the theory of complex adaptive systems.7

A workshop held by the MRC Population Health Sciences Research Network to consider whether and how the framework should be updated likewise recommended the inclusion of a model of the evaluation process less closely to tied to the phases of drug development; more guidance on how to approach the development, reporting, and implementation of complex interventions; and greater attention to the contexts in which interventions take place. It further recommended consideration of alternatives to randomised trials, and of highly complex or non-health sector interventions to which biomedical methods may not be applicable, and more evidence and examples to back up and illustrate the recommendations. The new guidance addresses these issues in depth, and here we set out the key messages.

What are complex interventions?

Complex interventions are usually described as interventions that contain several interacting components, but they have other characteristics that evaluators should take into account (box 1). There is no sharp boundary between simple and complex interventions. Few interventions are truly simple, but the number of components and range of effects may vary widely. Some highly complex interventions, such as the Sure Start intervention to support families with young children in deprived communities,8 may comprise a set of individually complex interventions.

Box 1 What makes an intervention complex?

- Number of interacting components within the experimental and control interventions

- Number and difficulty of behaviours required by those delivering or receiving the intervention

- Number of groups or organisational levels targeted by the intervention

- Number and variability of outcomes

- Degree of flexibility or tailoring of the intervention permitted

How these characteristics are dealt with will depend on the aims of the evaluation. A key question in evaluating complex interventions is whether they are effective in everyday practice (box 2).9 It is therefore important to understand the whole range of effects and how they vary, for example, among recipients or between sites. A second key question in evaluating complex interventions is how the intervention works: what are the active ingredients and how are they exerting their effect? Answers to this kind of question are needed to design more effective interventions and apply them appropriately across group and setting.10

Box 2 Developing and evaluating complex studies

- A good theoretical understanding is needed of how the intervention causes change, so that weak links in the causal chain can be identified and strengthened

- Lack of effect may reflect implementation failure (or teething problems) rather than genuine ineffectiveness; a thorough process evaluation is needed to identify implementation problems

- Variability in individual level outcomes may reflect higher level processes; sample sizes may need to be larger to take account of the extra variability and cluster randomised designs considered

- A single primary outcome may not make best use of the data; a range of measures will be needed and unintended consequences picked up where possible

- Ensuring strict standardisation may be inappropriate; the intervention may work better if a specified degree of adaptation to local settings is allowed for in the protocol

Development, evaluation, and implementation

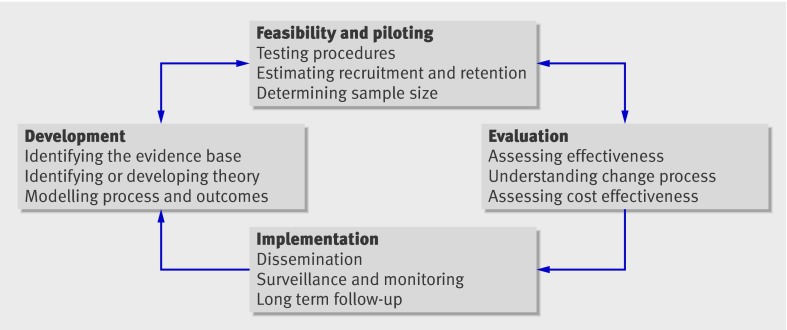

The 2000 framework characterised the process of development through to implementation of a complex intervention in terms of the phases of drug development. Although it is useful to think in terms of phases, in practice these may not follow a linear or even a cyclical sequence (figure).4

Fig 1 Key elements of the development and evaluation process

Best practice is to develop interventions systematically, using the best available evidence and appropriate theory, then to test them using a carefully phased approach, starting with a series of pilot studies targeted at each of the key uncertainties in the design, and moving on to an exploratory and then a definitive evaluation. The results should be disseminated as widely and persuasively as possible, with further research to assist and monitor the process of implementation.

In practice, evaluation takes place in a wide range of settings that constrain researchers’ choice of interventions to evaluate and their choice of evaluation methods. Ideas for complex interventions emerge from various sources, which may greatly affect how much leeway the researcher has to modify the intervention, to influence the way it is implemented, or to adopt an ideal evaluation design.8 Evaluation may take place alongside large scale implementation, rather than starting beforehand. Strong evidence may be ignored or weak evidence taken up, depending on its political acceptability or fit with other ideas about what works.11

Researchers need to consider carefully the trade-off between the importance of the intervention and the value of the evidence that can be gathered given these constraints. In an evaluation of the health impact of a social intervention, such as a programme of housing improvement, the researcher may have no say in what the intervention consists of and little influence over how or when the programme is implemented, limiting the scope to undertake development work or to determine allocation. Experimental methods are becoming more widely accepted as methods to evaluate policy,12 but there may be political or ethical objections to using them to assess health effects, especially if the intervention provides important non-health benefits.13 Given the cost of such interventions, evaluation should still be considered—the best available methods, even if they are not optimal in terms of internal validity, may yield useful results.14

If non-experimental methods are used, researchers should be aware of their limitations and interpret and present the findings with due caution. Wherever possible, evidence should be combined from different sources that do not share the same weaknesses.15 Researchers should be prepared to explain to decision makers the need for adequate development work, the pros and cons of experimental and non-experimental approaches, and the trade-offs involved in settling for weaker methods. They should be prepared to challenge decision makers when interventions of uncertain effectiveness are being implemented in a way that would make strengthening the evidence through a rigorous evaluation difficult, or when a modification of the implementation strategy would open up the possibility of a much more informative evaluation.

Developing a complex intervention

_Identifying existing evidence—_Before a substantial evaluation is undertaken, the intervention must be developed to the point where it can reasonably be expected to have a worthwhile effect. The first step is to identify what is already known about similar interventions and the methods that have been used to evaluate them. If there is no recent, high quality systematic review of the relevant evidence, one should be conducted and updated as the evaluation proceeds.

_Identifying and developing theory—_The rationale for a complex intervention, the changes that are expected, and how change is to be achieved may not be clear at the outset. A key early task is to develop a theoretical understanding of the likely process of change by drawing on existing evidence and theory, supplemented if necessary by new primary research. This should be done whether the researcher is developing the intervention or evaluating one that has already been developed.

_Modelling process and outcomes—_Modelling a complex intervention before a full scale evaluation can provide important information about the design of both the intervention and the evaluation. A series of studies may be required to progressively refine the design before embarking on a full scale evaluation. Developers of a trial of physical activity to prevent type 2 diabetes adopted a causal modelling approach that included a range of primary and desk based studies to design the intervention, identify suitable measures, and predict long term outcomes.3 Another useful approach is a prior economic evaluation.16 This may identify weaknesses and lead to refinements, or even show that a full scale evaluation is unwarranted. A modelling exercise to prepare for a trial of falls prevention in elderly people showed that the proposed system of screening and referral was highly unlikely to be cost effective and informed the decision not to proceed with the trial.17

Assessing feasibility

Evaluations are often undermined by problems of acceptability, compliance, delivery of the intervention, recruitment and retention, and smaller than expected effect sizes that could have been predicted by thorough piloting.18 A feasibility study for an evaluation of an adolescent sexual health intervention in rural Zimbabwe found that the planned classroom based programme was inappropriate, given cultural norms, teaching styles, and relationships between teachers and pupils in the country, and it was replaced by a community based programme.19 As well as illustrating the value of feasibility testing, the example shows the importance of understanding the context in which interventions take place.

A pilot study need not be a scale model of the planned evaluation but should examine the key uncertainties that have been identified during development. Pilot studies for a trial of free home insulation suggested that attrition might be high, so the design was amended such that participants in the control group received the intervention after the study.20 Pilot study results should be interpreted cautiously when making assumptions about the numbers required when the evaluation is scaled up. Effects may be smaller or more variable and response rates lower when the intervention is rolled out across a wider range of settings.

Evaluating a complex intervention

There are many study designs to choose from, and different designs suit different questions and circumstances. Researchers should beware of blanket statements about what designs are suitable for what kind of intervention and choose on the basis of specific characteristics of the study, such as expected effect size and likelihood of selection or allocation bias. Awareness of the whole range of experimental and non-experimental approaches should lead to more appropriate methodological choices.

Assessing effectiveness

Randomisation should always be considered because it is the most robust method of preventing selection bias. If a conventional parallel group randomised trial is not appropriate, other randomised designs should be considered (box 3).

Box 3 Experimental designs for evaluating complex interventions

_Individually randomised trials—_Individuals are randomly allocated to receive either an experimental intervention or an alternative such as standard treatment, a placebo, or remaining on a waiting list. Such trials are sometimes dismissed as inapplicable to complex interventions, but there are many variants, and often solutions can be found to the technical and ethical problems associated with randomisation

Cluster randomised trials are one solution to the problem of contamination of the control group, leading to biased estimates of effect size, in trials of population level interventions. Groups such as patients in a general practice or tenants in a housing scheme are randomly allocated to the experimental or control intervention

Stepped wedge designs may be used to overcome practical or ethical objections to experimentally evaluating an intervention for which there is some evidence of effectiveness or which cannot be made available to the whole population at once. It allows a trial to be conducted without delaying roll-out of the intervention. Eventually, the whole population receives the intervention, but with randomisation built into the phasing of implementation

_Preference trials and randomised consent designs—_Practical or ethical obstacles to randomisation can sometimes be overcome by using non-standard designs. When patients have strong preferences among treatments, basing treatment allocation on patients’ preferences or randomising patients before seeking consent may be appropriate.

_N of 1 designs—_Conventional trials aim to estimate the average effect of an intervention in a population. N of 1 trials, in which individuals undergo interventions with the order or scheduling decided at random, can be used to assess between and within person change and to investigate theoretically predicted mediators of that change

If an experimental approach is not feasible, because the intervention is irreversible, necessarily applies to the whole population, or because large scale implementation is already under way, a quasi-experimental or an observational design may be considered. In some circumstances, randomisation may be unnecessary and other designs preferable,21 22 but the conditions under which observational methods can yield reliable estimates of effect are limited (box 4).23 Successful examples, such as the evaluation of legislation to restrict access to means of suicide,24 reduce air pollution,25 or ban smoking in public places,26 tend to occur where interventions have rapid, large effects.

Box 4 Choosing between randomised and non-randomised designs

_Size and timing of effects—_Randomisation may be unnecessary if the effects of the intervention are so large or immediate that confounding or underlying trends are unlikely to explain differences in outcomes before and after exposure. It may be inappropriate—for example, on grounds of cost or delay—if the changes are very small or take a long time to appear. In these circumstances a non-randomised design may be the only feasible option, in which case firm conclusions about the impact of the intervention may be unattainable

_Likelihood of selection bias—_Randomisation is needed if exposure to the intervention is likely to be associated with other factors that influence outcomes. Post-hoc adjustment is a second best solution; its effectiveness is limited by errors in the measurement of the confounding variables and the difficulty of dealing with unknown or unmeasured confounders

_Feasibility and acceptability of experimentation—_Randomisation may be impractical if the intervention is already in widespread use, or if key decisions about how it will be implemented have already been taken, as is often the case with policy changes and interventions whose effect on health is secondary to their main purpose

_Cost—_If an experimental study is feasible and would provide more reliable information than an observational study but would also cost more, the additional cost should be weighed against the value of having better information

Measuring outcomes

Researchers need to decide which outcomes are most important, which are secondary, and how they will deal with multiple outcomes in the analysis. A single primary outcome and a small number of secondary outcomes are the most straightforward for statistical analysis but may not represent the best use of the data or provide an adequate assessment of the success or otherwise of an intervention that has effects across a range of domains. It is important also to consider which sources of variation in outcomes matter and to plan appropriate subgroup analyses.

Long term follow-up may be needed to determine whether outcomes predicted by interim or surrogate measures do occur or whether short term changes persist. Although uncommon, such studies can be highly informative. Evaluation of a preschool programme for disadvantaged children showed that, as well as improved educational attainment, there was a range of economic and social benefits at ages 27 and 40.27

Understanding processes

Process evaluations, which explore the way in which the intervention under study is implemented, can provide valuable insight into why an intervention fails or has unexpected consequences, or why a successful intervention works and how it can be optimised. A process evaluation nested inside a trial can be used to assess fidelity and quality of implementation, clarify causal mechanisms, and identify contextual factors associated with variation in outcomes.5 However, it is not a substitute for evaluation of outcomes. A process evaluation28 carried out in connection with a trial of educational visits to encourage general practitioners to follow prescribing guidelines29 found that the visits were well received and recall of the guidelines was good, yet there was little change in prescribing behaviour, which was constrained by other factors such as patients’ preferences and local hospital policy.

Fidelity is not straightforward in relation to complex interventions.30 In some evaluations, such as those seeking to identify active ingredients within a complex intervention, strict standardisation may be required and controls put in place to limit variation in implementation.31 But some interventions are designed to be adapted to local circumstances. In a trial of a school based intervention to promote health and wellbeing, schools were encouraged to use a standardised process to develop strategies which suited them rather than adopt a fixed curriculum, resulting in widely varied practice between schools.32 The key is to be clear about how much change or adaptation is permissible and to record variations in implementation so that fidelity can be assessed in relation the degree of standardisation required by the study protocol.

Variability in implementation, preplanned or otherwise, makes it important that both process and outcome evaluations are reported fully and that a clear description of the intervention is provided to enable replication and synthesis of evidence.33 This has been a weakness of the reporting of complex intervention studies in the past,34 but the availability of a comprehensive range of reporting guidelines, now covering non-drug trials35 and observational studies36 and accessible through a single website (www.equator-network.org) should lead to improvement.

Conclusions

We recognise that many issues surrounding evaluation of complex interventions are still debated, that methods will continue to develop, and that practical applications will be found for some of the newer theories. We do not intend the revised guidance to be prescriptive but to help researchers, funders, and other decision makers to make appropriate methodological and practical choices. We have primarily aimed our messages at researchers, but publishers, funders, and commissioners of research also have an important part to play. Journal editors should insist on high and consistent standards of reporting. Research funders should be prepared to support developmental studies before large scale evaluations. The key message for policy makers is the need to consider evaluation requirements in the planning of new initiatives, and wherever possible to allow for an experimental or a high quality non-experimental approach to the evaluation of initiatives when there is uncertainty about their effectiveness.

Contributors: PD had the idea of revising and updating the MRC framework. It was further developed at a workshop co-convened with Sally Macintyre and Janet Darbyshire, and organised with the help of Linda Morris on 15-16 May 2006. Workshop participants and others with an interest in the evaluation of complex interventions were invited to comment on a draft of the revised guidance, which was also reviewed by members of the MRC Health Services and Public Health Research Board and MRC Methodology Research Panel. A full list of all those who contributed suggestions is provided in the full guidance document.

Funding: MRC Health Services and Public Health Research Board and the MRC Population Health Sciences Research Network.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2008;337:a1655

References

- 1.Medical Research Council. A framework for the development and evaluation of RCTs for complex interventions to improve health. London: MRC, 2000.

- 2.Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth AL, Sandercock P, Spiegelhalter D, et al. Framework for the design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ 2000;321:694-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardeman W, Sutton S, Griffin S, Johnston M, White A, Wareham NJ, et al. A causal modelling approach to the development of theory-based behaviour change programmes for trial evaluation. Health Educ Res 2005;20:676-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J, Emery J, Farmer A, Griffiths F, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ 2007;334:455-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oakley A, Strange V, Bonell C, Allen E, Stephenson J, Ripple Study Team. Process evaluation in randomised controlled trials of complex interventions. BMJ 2006;332:413-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell M, Donner A, Klar N. Developments in cluster randomised trials and Statistics in Medicine. Stat Med 2007;26:2-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiell A, Hawe P, Gold L. Complex interventions or complex systems? Implications for health economic evaluation. BMJ 2008;336:1281-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belsky J, Melhuish E, Barnes J, Leyland AH, Romaniuk H, National Evaluation of Sure Start Research Team. Effects of Sure Start local programmes on children and families: early findings from a quasi-experimental, cross sectional study. BMJ 2006;332:1476-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haynes B. Can it work? Does it work? Is it worth it? The testing of healthcare interventions is evolving. BMJ 1999;319:652-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michie S, Abraham C. Interventions to change health behaviours: evidence-based or evidence-inspired? Psychol Health 2004;19:29-49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muir H. Let science rule: the rational way to run societies. New Scientist 2008;198:40-3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creegan C, Hedges A. Towards a policy evaluation service: developing infrastructure to support the use of experimental and quasi-experimental methods. London: Ministry of Justice, 2007.

- 13.Thomson H, Hoskins R, Petticrew M, Ogilvie D, Craig N, Quinn T, et al. Evaluating the health effects of social interventions. BMJ 2004;328:282-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogilvie D, Mitchell R, Mutrie N, Petticrew M, Platt S. Evaluating health effects of transport interventions: methodologic case study. Am J Prev Med 2006;31:118-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Academy of Medical Sciences. Identifying the environmental causes of disease: how should we decide what to believe and when to take action? London: Academy of Medical Sciences, 2007.

- 16.Torgerson D, Byford S. Economic modelling before clinical trials. BMJ 2002;325:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eldridge S, Spencer A, Cryer C, Pearsons S, Underwood M, Feder G. Why modelling a complex intervention is an important precursor to trial design: lessons from studying an intervention to reduce falls-related injuries in elderly people. J Health Services Res Policy 2005;10:133-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eldridge S, Ashby D, Feder G, Rudnicka AR, Ukoumunne OC. Lessons for cluster randomized trials in the twenty-first century: a systematic review of trials in primary care. Clin Trials 2004;1:80-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Power R, Langhaug L, Nyamurera T, Wilson D, Bassett M, Cowan F. Developing complex interventions for rigorous evaluation—a case study from rural Zimbabwe. Health Educ Res 2004;19:570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howden-Chapman P, Crane J, Matheson A, Viggers H, Cunningham M, Blakely T, et al. Retrofitting houses with insulation to reduce health inequalities: aims and methods of a clustered community-based trial. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:2600-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. BMJ 1996;312:1215-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Rawlins M, McCulloch P. When are randomised trials unnecessary? Picking signal from noise. BMJ 2007;334:349-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacMahon S, Collins R. Reliable assessment of the effects of treatment on mortality and major morbidity. II. observational studies. Lancet 2001;357:455-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunnell D, Fernando R, Hewagama M, Priyangika W, Konradsen F, Eddleston M. The impact of pesticide regulations on suicide in Sri Lanka. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:1235-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clancy L, Goodman P, Sinclair H, Dockery DW. Effect of air pollution control on death rates in Dublin, Ireland: an intervention study. Lancet 2002;360:1210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haw SJ, Gruer L. Changes in exposure of adult non-smokers to secondhand smoke after implementation of smoke-free legislation in Scotland: national cross sectional survey. BMJ 2007;335:549-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wortman PM. An exemplary evaluation of a program that worked: the High/Scope Perry preschool project. Am J Eval 1995;16:257-65. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nazareth I, Freemantle N, Duggan C, Mason J, Haines A. Evaluation of a complex intervention for changing professional behaviour: the evidence based out reach (EBOR) trial. J Health Services Res Policy 2002;7:230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freemantle N, Nazareth I, Eccles M, Wood J, Haines A, EBOR Triallists. A randomised controlled trial of the effect of educational outreach by community pharmacists on prescribing in UK general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2002;52:290-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how “out of control” can a randomised trial be? BMJ 2004;328:1561-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farmer A, Wade A, Goyder E, Yudkin P, French D, Craven A, et al. Impact of self-monitoring of blood glucose in the management of patients with non-insulin treated diabetes: open parallel group randomised trial. BMJ 2007;335:132-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patton G, Bond L, Butler H, Glover S. Changing schools, changing health? Design and implementation of the Gatehouse Project. J Adolesc Health 2003;33:231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008;27:379-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasziou P, Meats E, Heneghan C, Shepperd S. What is missing from descriptions of treatments in trials and reviews? BMJ 2008;336:1472-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman D, Scultz K, Ravaud P. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of non-pharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Int Med 2008;148:295-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Von Elm E, Altman D, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche P, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]