Scavenging of the cofactor lipoate is essential for the survival of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2009 Dec 21.

Summary

Lipoate is an essential cofactor for key enzymes of oxidative metabolism. Plasmodium falciparum possesses genes for lipoate biosynthesis and scavenging, but it is not known if these pathways are functional, nor what their relative contribution to the survival of intraerythrocytic parasites might be. We detected in parasite extracts four lipoylated proteins, one of which cross-reacted with antibodies against the E2 subunit of apicoplast-localized pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). Two highly divergent parasite lipoate ligase A homologues (LplA), LipL1 (previously identified as LplA) and LipL2, restored lipoate scavenging in lipoylation-deficient bacteria, indicating that Plasmodium has functional lipoate-scavenging enzymes. Accordingly, intraerythrocytic parasites scavenged radiolabelled lipoate and incorporated it into three proteins likely to be mitochondrial. Scavenged lipoate was not attached to the PDH E2 subunit, implying that lipoate scavenging drives mitochondrial lipoylation, while apicoplast lipoylation relies on biosynthesis. The lipoate analogue 8-bromo-octanoate inhibited LipL1 activity and arrested P. falciparum in vitro growth, decreasing the incorporation of radiolabelled lipoate into parasite proteins. Furthermore, growth inhibition was prevented by lipoate addition in the medium. These results are consistent with 8-bromo-octanoate specifically interfering with lipoate scavenging. Our study suggests that lipoate metabolic pathways are not redundant, and that lipoate scavenging is critical for Plasmodium intraerythrocytic survival.

Introduction

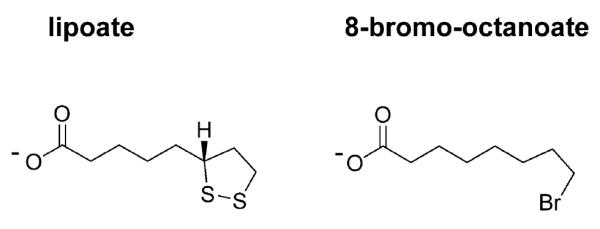

Lipoate (6,8-thiooctanoic acid, Fig. 1) is a cofactor required for the function of key enzyme complexes involved in oxidative metabolism: pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGDH), branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCDH), and the glycine cleavage system (Fujiwara et al., 1986; Reed and Hackert, 1990; Perham, 2000; Douce et al., 2001). Recent studies have highlighted the importance of lipoate for the intracellular growth and virulence of bacterial pathogens (O’Riordan et al., 2003; Pilatz et al., 2006). Moreover, lipoate is involved in the defence against immune response-induced oxidative and nitrosative stress in mycobacteria (Bryk et al., 2002), consistent with a growing body of evidence that lipoylated proteins have an important antioxidant role in addition to their enzymatic activities (reviewed in Bunik, 2003).

Fig. 1.

The structures of _R_-lipoate and BrO.

Lipoate-requiring complexes typically contain three protein subunits, E1, E2 and E3. Lipoate is linked through an amide bond to lysine residues in the E2 subunits (Nawa et al., 1960; Reche and Perham, 1999) and acts as a swinging arm transferring covalently attached reaction intermediates among the active sites of the enzyme complex (Reed, 1966; Perham, 2000). Two lipoate metabolic pathways have been characterized in E. coli – a synthesis pathway and a scavenging pathway (Morris et al., 1995). Lipoate scavenging relies on the ATP-dependent lipoate ligase LplA, which catalyses the covalent attachment of free lipoate to non-lipoylated E2 subunits (apo-E2) (Morris et al., 1994; Jordan and Cronan, 2003; Fujiwara et al., 2005). In the absence of exogenous lipoate, two enzymes synthesize lipoate from octanoyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP), an intermediate of fatty acid biosynthesis (Vanden Boom et al., 1991; Morris et al., 1995; Miller et al., 2000). LipB (octanoyl-ACP:protein N-octanoyltransferase) transfers the octanoyl group from octanoyl-ACP to apo-E2. LipA (lipoate synthase) catalyses the insertion of two sulphur atoms into octanoyl-E2 to form lipoyl-E2 (Jordan and Cronan, 2003; Zhao et al., 2003; Booker, 2004).

The P. falciparum genome, available through the PlasmoDB genomic resource (Bahl et al., 2003), encodes the proteins constituting the four known lipoate-requiring complexes, as well as enzymes of the lipoate biosynthetic and scavenging pathways. Several observations suggest that lipoylation may occur in the apicoplast and in the mitochondrion. On one hand, the E1α and E2 subunits of the parasite PDH are situated in the apicoplast, a relic plastid organelle (Foth et al., 2005). Functional P. falciparum homologues for LipB (MAL8P1.37) and LipA (MAL13P1.220) with apicoplast-targeting peptides have been described, and the N-terminal end of the malaria LipA homologue targets the green fluorescent protein (GFP) to a compartment distinct from the mitochondrion, believed to be the apicoplast (Wrenger and Muller, 2004). In addition, fatty acid biosynthesis, which produces the lipoate precursor octanoyl-ACP, takes place in the apicoplast (reviewed in Lu et al., 2005). This suggests that a lipoate biosynthesis pathway occurs in this organelle, enabling in situ lipoylation of PDH.

On the other hand, P. falciparum KGDH, BCDH and the glycine cleavage system are predicted to be mitochondrial, as in other eukaryotes. This prediction is supported by the mitochondrial localization of the E1β subunit of BCDH (Gunther et al., 2005) and of an E3 subunit common to BCDH and KGDH (McMillan et al., 2005). A P. falciparum LplA homologue (named LipL1 in this study) was localized to the mitochondrion using an N-terminal construct fused to GFP (Wrenger and Muller, 2004). It was shown to substitute for LipB activity in E. coli, demonstrating that LipL1 can transfer octanoyl moieties from octanoyl-ACP to apo-E2 subunits. As ACP is not found in the malaria mitochondrion (Waller et al., 2000), it is more likely that LipL1 has typical LplA activity, catalysing the attachment of preformed lipoate to acceptor proteins. The LplA activity of LipL1 has not been demonstrated and there is no known source of lipoate in the mitochondrion. One possibility is that lipoate synthesized in the apicoplast would also be utilized in the mitochondrion. Alternatively, the parasite could acquire lipoate from the host, as is the case for other essential nutrients (Saliba and Kirk, 2001a), because both human serum (Teichert and Preiss, 1992; Packer et al., 1995) and the red blood cell (Constantinescu et al., 1995) contain lipoate.

In this study, we establish the existence of lipoylation in P. falciparum and present the first evidence that P. falciparum erythrocytic stages scavenge lipoate from the medium. We show that the parasite possesses two functional LplA homologues, LipL1 and a newly identified paralogue, LipL2, which could be involved in lipoate scavenging. Importantly, disruption of this pathway by a lipoate analogue is lethal to the parasite in vitro. Hence, despite the probable existence of a biosynthetic pathway in the apicoplast, P. falciparum intraerythrocytic parasites appear to be auxotrophic for lipoate. This study exposes a new vulnerability that may be exploited to kill the malaria parasite.

Results

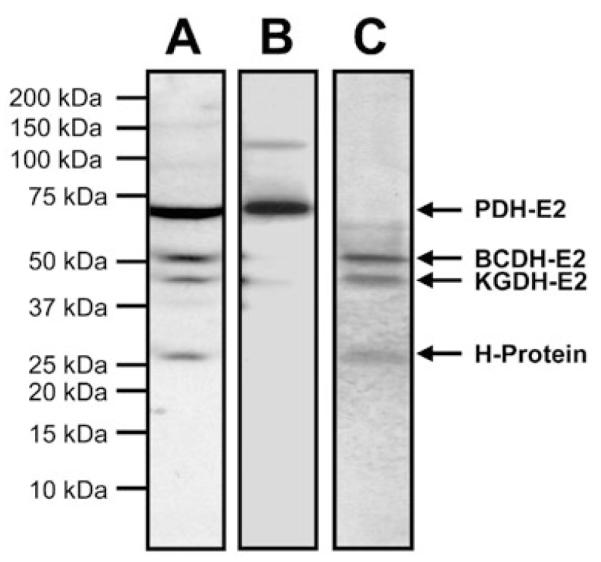

Evidence of lipoylation in P. falciparum erythrocytic stages

The P. falciparum genome encodes four proteins that are known to be lipoylated in other organisms: the E2 subunits of PDH, KGDH and BCDH, and the H-protein of the glycine cleavage system (Table 1). To determine if lipoylation indeed occurs in the parasite, we analysed extracts from P. falciparum erythrocytic stages using antiserum specific for lipoylated proteins (Humphries and Szweda, 1998; Sasaki et al., 2000). By Western blot, four major bands with apparent masses of 73 kDa, 53 kDa, 46 kDa and 26 kDa were recognized (Fig. 2A). The predicted masses of these four proteins are close to those of the four malaria lipoate acceptor proteins (Table 1), suggesting that all four parasite proteins were labelled in the Western blot. We positively identified the 73 kDa band using antibodies specific for P. falciparum apicoplast-localized PDH E2 subunit (Fig. 2B). As the other three lipoate acceptor proteins are thought to be mitochondrial (Table 1), these results provide further support for the existence of lipoylation pathways in both the apicoplast and the mitochondrion.

Table 1.

Predicted lipoate-requiring enzyme complexes in P. falciparum.

| Lipoate-requiringenzyme complexes | Lipoateacceptora | Mwb | Predicted localization | Experimentally determinedlocalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDH | E2 subunit (2) | 73 kDa | Apicoplast (all subunits) | Apicoplast (E1α and E2 subunits) |

| BCDH | E2 subunit (1) | 51 kDa | Mitochondrion (all subunits) | Mitochondrion (E1β and E3 subunitsc) |

| KGDH | E2 subunit (1) | 48 kDa | Mitochondrion (all subunits) | Mitochondrion (E3 subunitc) |

| Glycine cleavage system | H-protein (1) | 23 kDa | Mitochondrion (all components) | ND |

Fig. 2.

Evidence of lipoylation and lipoate scavenging in P. falciparum.

A. Western blot analysis of a lysate from asynchronous erythrocytic stage parasites probed with antiserum specific for lipoylated proteins (1:10 000).

B. Western blot analysis of a lysate from asynchronous erythrocytic stage parasites probed with antibodies specific for the E2 subunit of P. falciparum PDH (1:500).

C. Incorporation of radiolabelled lipoate into proteins. Erythrocytic stage parasites were cultured for 2 days in the presence of [35S]-lipoate (0.3 μCi ml−1). Protein extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and analysed by autoradiography. The putative assignment of protein bands is indicated.

Identification of LipL2, a new P. falciparum LplA homologue

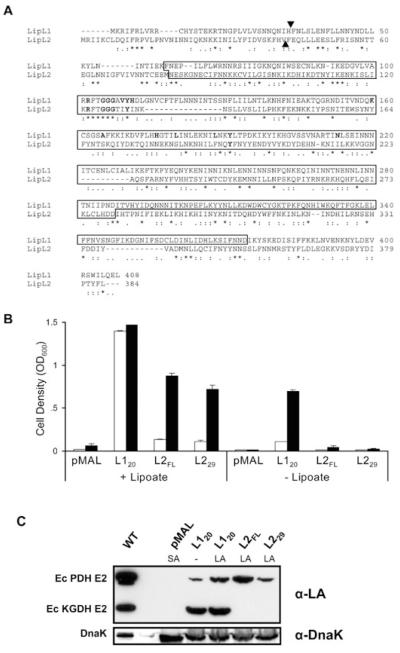

Using the PlasmoDB genomic database, we identified a hypothetical protein (PFI1160w) with 12% sequence identity to E. coli LplA. We designated this protein as lipoate ligase 2 (LipL2) and cloned the LipL2 gene from mixed erythrocytic stage P. falciparum cDNA. The LipL2 gene (this sequence has been submitted in GenBank under accession number DQ400341) encodes a polypeptide of 384 amino acids with a calculated mass of 46 059 Da (Fig. 3A). The typical Pfam domain BPL_LiplA_LipB, which defines a family including biotin protein ligases, LplA enzymes and LipB enzymes, is present in region 110–246 of the protein. The conserved lipoate ligase domain KOG3159 is situated in region 79–280. In addition, many of the important residues involved in substrate binding in Thermoplasma acidophilum LplA homologue (Kim et al., 2005) are conserved in LipL2 sequence (Fig. 3A). The N-terminal end of the protein is predicted to be a mitochondrial transit peptide by MITOPROT, with a probability of export to the mitochondria of 0.93, but this algorithm fails to identify a likely cleavage site. In contrast, PLASMIT, a prediction tool designed to identify malaria mitochondrial proteins, predicts cytosolic localization with 99% confidence.

Fig. 3.

P. falciparum possesses two functional LplA homologues.

A. CLUSTALW alignment of P. falciparum LipL1 and LipL2 amino acid sequences. Boxed residues correspond to the conserved lipoate ligase region (KOG3159). The amino acids involved in the interaction with the lipoyl-AMP intermediate in the crystal structure of Thermoplasma acidophilum LplA (Kim et al., 2005) are highlighted in bold. Triangles mark the first amino acids in the LipL120 and LipL229 constructs.

B. Functional complementation of lipoylation-deficient E. coli strain TM136. TM136 cells transformed with mature LipL1 (L120), full-length LipL2 (L2FL), a putative mature LipL2 (L229), or the pMAL vector alone were incubated at 37°C in non-permissive minimal E medium containing 0.1 mM IPTG, in the presence or in the absence of 10 ng ml−1 lipoate. The starting optical density (OD600) for each culture was 0.01. Cell growth was assessed by measuring the OD600 of the cultures after 48 h (open bars) and 72 h (closed bars). Experiments were conducted in triplicate and error bars indicate the standard deviation.

C. LipL1 and LipL2 specificity for E. coli lipoate acceptor proteins. After functional complementation, lysates from equivalent amounts of cells expressing LipL120, LipL2FL and LipL229 were analysed by Western blot using antiserum specific for lipoylated proteins (α-LA). The absence (−) or presence (LA) of lipoate in the complementation medium is indicated. Loading was normalized to the optical density. The lipoylation pattern of the BL21 strain, which is wild-type for lipoylation (WT, about five times less cells), and of the TM136 cells expressing the pMAL vector alone [pMAL, requiring succinate and acetate (SA) for growth] are also shown. The same blot was stripped and reprobed with antiserum specific for E. coli DnaK as a loading control (α-DnaK).

LipL2 is homologous with lipoate ligases from both eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms (not shown). However, it has only 21% identity with LipL1 (Fig. 3A). We identified orthologues of LipL1 and LipL2 in the human parasite Plasmodium vivax, and in the murine parasites Plasmodium yoelii, Plasmodium berghei and Plasmodium chabaudi (Table 2). Amino acid sequence comparison indicates that LipL1 orthologues are well conserved and share higher sequence identity with E. coli LplA than do LipL2 orthologues (Table 2). Thus, LipL1 and LipL2 appear to define two distinct families of lipoate ligases whose existence is conserved within the Plasmodium genus.

Table 2.

Pairwise amino acid sequence identity between EcLplA and malaria homologues of PfLipL1 and PfLipL2a.

| LipL1 homologues(% identity) | LipL2 homologues(% identity) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PfLipL1CAD52290PF13_0083 | P. yoeliiEAA16231PY00475 | P. bergheiCAH97438PB000283.02.0 | P. chabaudi CAH75491b | P. vivax402129.phat_113270182 | PfLipL2CAD51918PF1160W | P. yoeliiEAA21837 | P. bergheiCAH95194Pb0011.58.00.0 | P. chabaudiCAH79244 | P. vivax402151.phat_213270304c | |

| EcLplAAAC77339 | 29 | 29 | 27 | 19_[28]_ | 26 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 14 |

| PfLipL1CAD52290PF13_0083 | 100 | 71 | 71 | 47_[71]_ | 54 | 21 | 19 | 21 | 21 | 15 |

| PfLipL2CAD51918PFI1160W | 21 | 19 | 20 | 17_[21]_ | 16 | 100 | 46 | 45 | 46 | 32 |

P. falciparum LipL1 and LipL2 restore LplA activity in an E. coli (LipB−, LplA−) mutant

A previous report indicated that LipL1 can substitute for E. coli LipB (Wrenger and Muller, 2004), demonstrating that LipL1 can transfer the octanoyl group from octanoyl-ACP to acceptor proteins. However, an involvement of LipL1 in the lipoate biosynthetic pathway is improbable, because this pathway and the production of the precursor octanoyl-ACP occur in the apicoplast, while LipL1 is located in the mitochondrion (Wrenger and Muller, 2004). To assess the lipoate ligase activity sensu stricto of LipL1 and of the newly identified LipL2, we investigated their ability to substitute for E. coli LplA. Functional complementation experiments were performed in the lipoylation-deficient E. coli strain TM136 (Fig. 3B), where both the octanoyltransferase activity (LipB−) from the biosynthetic pathway and the lipoate ligase activity (LplA−) from the scavenging pathway are disrupted. The constructs used were LipL1 lacking its mitochondrial transit peptide (LipL120), the full-length LipL2 protein (LipL2FL) and LipL2 lacking a putative mitochondrial transit peptide (LipL229). The lipoate ligase activity was tested by growing TM136 cells transformed with these constructs in a minimal medium with or without lipoate (Fig. 3B). The strains expressing LipL120 grew slowly in the absence of lipoate, indicating some LipB activity, as suggested previously (Wrenger and Muller, 2004). However, they grew much faster in the presence of lipoate, demonstrating that LipL1 primarily possesses a lipoate ligase (LplA) activity, using free lipoate scavenged from the medium. The strains expressing LipL2FL and LipL229 only grew in the presence of lipoate, indicating that LipL2 indeed possesses LplA activity, but no detectable LipB activity. In all conditions tested, the absence of growth of the strain expressing the empty vector confirmed that the phenotypes observed were specific to the LipL1 and LipL2 genes.

The lipoylation activity of LipL1 and LipL2 was further analysed by Western blot of TM136 cell lysates following functional complementation, using antiserum specific for lipoylated proteins (Fig. 3C). The presence of lipoylated PDH, and, more prominently, of lipoylated KGDH, was detected in the TM136 cells expressing LipL1 (grown both in the absence or in the presence of lipoate). In contrast, lipoylated PDH alone was detected in the TM136 cells expressing either of the LipL2 constructs, suggesting differences in substrate specificity between LipL1 and LipL2.

Together, these results demonstrate that LipL1 and LipL2 are functional lipoate ligases, which could both participate in lipoate scavenging in P. falciparum by using free lipoate as a substrate.

P. falciparum erythrocytic stages take up exogenous lipoate and incorporate it into specific parasite proteins

To investigate whether P. falciparum is indeed able to scavenge lipoate from the medium, we developed a novel method to prepare _R_-[6,8-35S]-lipoate (see Appendix S1). P. falciparum erythrocytic stages were then cultured in the presence of [35S]-lipoate and parasite protein extracts were analysed for the incorporation of radiolabel. Autoradiography revealed the incorporation of [35S]-lipoate into three proteins of 53 kDa, 46 kDa and 26 kDa (Fig. 2C). This result demonstrates the existence of a functional lipoate-scavenging pathway in P. falciparum erythrocytic stages. Notably, the radiolabelled proteins only correspond to three of the four parasite proteins identified by Western blot using antiserum specific for lipoylated proteins. The 73 kDa band recognized by antiserum specific for lipoylated proteins and by antibodies specific for the E2 subunit of PDH was not labelled (Fig. 2C). As this protein is exclusively localized to the apicoplast (Foth et al., 2005), these results also provide compelling evidence that scavenged lipoate is not a significant source of apicoplast lipoate in P. falciparum erythrocytic stages.

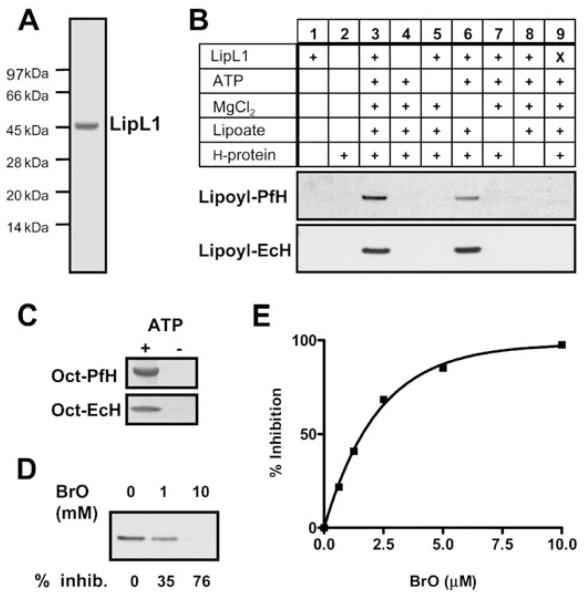

The lipoate analogue 8-bromo-octanoate inhibits lipoate ligase activity

In order to determine the importance of lipoate scavenging in P. falciparum, we aimed to identify a compound able to interfere with lipoate ligase activity. Previous studies in E. coli showed that a lipoate analogue was used as a substrate by E. coli LplA, resulting in the in vivo accumulation of non-functional α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes and inhibition of bacterial growth (Morris et al., 1994; Reed et al., 1994). We assessed the effects of a different lipoate analogue, 8-bromo-octanoate (BrO, Fig. 1), on lipoate ligase activity. Our in vitro assays used purified P. falciparum recombinant LipL1 (Fig. 4A) and, as lipoate acceptor proteins, the H-protein from P. falciparum (Table 1) and from E. coli. The P. falciparum H-protein gene, which was cloned from erythrocytic stages cDNA, encodes a 200-amino-acid protein with a putative mitochondrial targeting peptide and one lipoylation domain (Table 1). Both H-proteins were overexpressed in lipoylation-deficient E. coli strain TM136 to obtain apo-proteins. Pure recombinant LipL120 (Fig. 4A) has a typical ATP-dependent lipoate ligase activity, and appears to be stimulated by magnesium when P. falciparum H-protein is used as a substrate (Fig. 4B). Additionally, similar to E. coli LplA (Morris et al., 1994; Zhao et al., 2003), it also displays ATP-dependent octanoate ligase activity (Fig. 4C). In the presence of BrO, a dose-dependent inhibition of both lipoylation (Fig. 4D) and octanoylation (Fig. 4E) activities was observed. Mass spectrometry analysis showed that BrO is a LipL1 substrate and is covalently attached to the H-protein (not shown). Interestingly, the BrO concentrations necessary to obtain significant inhibition in both assays suggest that BrO is a better substrate than octanoate, but a worse substrate than lipoate.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition by BrO of pure recombinant LipL1 enzymatic activity.

A. Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel showing purified LipL120.

B. LipL1 lipoylation activity. Purified LipL120 (0.3 μM) was assayed for lipoate ligase activity in the presence (+) or the absence of several reaction components as indicated, using 1.8 μM apo-PfH-protein (upper panel) or 2 μM apo-EcH-protein (lower panel). The lipoate concentration was 180 μM. The reactions were analysed by SDS-PAGE, and lipoylated proteins were detected by Western blot analysis using antiserum specific for lipoylated proteins. X, heat-killed LipL120.

C. LipL1 octanoylation activity. Purified LipL120 (3 μM) was assayed for octanoate ligase activity in the presence (+) or the absence (−) of 1.8 mM ATP using 10 μM apo-PfH-protein (upper panel) or apo-EcH-protein (lower panel). The [1-14C]-octanoate concentration was 72 μM. The reactions were analysed by SDS-PAGE, and octanoylated proteins were detected by autoradiography.

D. Inhibition of LipL1 lipoylation activity by BrO. LipL120 was assayed as described in B with apo-PfH-protein as substrate in the presence of 180 μM lipoate and 0, 1 and 10 mM BrO. The percentage of inhibition as compared with the control reaction without BrO is indicated below the figure.

E. Inhibition of LipL1 octanoylation activity by BrO. LipL120 was assayed as described in C with apo-PfH-protein as substrate in the presence of 72 μM [1-14C]-octanoate and of various concentrations of BrO. Octanoylated H-protein was TCA-precipitated and quantified by scintillation counting. The graph shows the percentage inhibition versus BrO concentration.

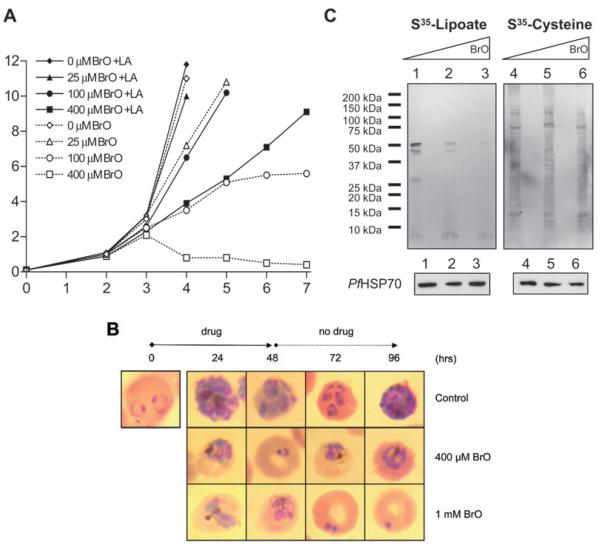

8-bromo-octanoate arrests P. falciparum in vitro growth and disrupts lipoate scavenging

Having established that BrO interferes with lipoate ligase activity, we next examined its effects on P. falciparum erythrocytic stages in vitro. Asynchronous cultures were maintained in 0, 25, 100 and 400 μM of BrO. For each BrO concentration, culture media contained either no additional lipoate (thus containing an expected lipoate concentration of 16–70 nM from the serum, see Discussion) or 2 μM additional lipoate. For the first 2 days, no difference was observed between the BrO-treated and the control cultures. However, by the third day, the 100 μM and 400 μM BrO-treated cultures maintained without additional lipoate primarily contained condensed parasite forms characteristic of growth arrest (not shown), and a dose-dependent inhibition of parasite proliferation was observed (Fig. 5A). The addition of 2 μM lipoate to the medium rescued growth inhibition in the 25 μM BrO-treated culture and largely overcame growth inhibition in the 100 μM and 400 μM BrO-treated cultures. This result demonstrated that BrO specifically interferes with a lipoate-related process in P. falciparum parasites.

Fig. 5.

Effects of BrO on P. falciparum cultures.

A. Effect of BrO on P. falciparum proliferation. Asynchronous parasites were cultured for 7 days in the presence of 0, 25, 100 and 400 μM BrO, with or without additional 2 μM lipoate (LA) in the growth medium. Cultures were monitored and their parasitaemia assessed with daily Giemsa-stained smears.

B. Effect of BrO on synchronized parasites. P. falciparum cultures at the ring stage were incubated with 400 μM and 1 mM BrO for 48 h with daily medium change, then subsequently maintained without the lipoate analogue. Images of Giemsa-stained parasites from the different cultures analysed every 24 h are shown.

C. Effect of BrO on parasite incorporation of exogenous lipoate. Asynchronous cultures were grown for 2 days in the absence (lanes 1 and 4) or in the presence of 100 μM (lanes 2 and 5) and 400 μM (lanes 3 and 6) BrO. The culture media also contained [35S]-lipoate (0.9 μCi ml−1) or as a control, [35S]-cysteine (20 μCi ml−1), as indicated. Parasite extracts were analysed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography (upper panels) or by Western blot using anti-PfHSP70 antibodies (lower panels).

Although BrO inhibits parasite growth in the experiment shown in Fig. 5A, there appears to be a delayed effect. Mixed stage parasites were used for this experiment and it is likely that certain stages harbour significant populations of lipoylated proteins, delaying the effect of the inhibitor. A similar phenomenon was shown to mask a growth defect in mutant Listeria (O’Riordan et al., 2003). To address this possibility, the effects of BrO (400 μM and 1 mM) were analysed on synchronized cultures treated from the ring stage for 48 h. In the culture incubated with 400 μM BrO, a delay in parasite maturation was observed after 24 h (young trophozoites versus early and late schizonts in the control) and 48 h (early rings versus late rings and trophozoites in the control) incubation (Fig. 5B). At the 48 h time point, BrO was removed from the medium; however, parasites with abnormal morphology were observed at the 72 h and 96 h time points, suggesting that BrO effects are irreversible. At a higher concentration (1 mM), BrO induced the formation of aberrant parasites at 24 h, with an accumulation of abnormal schizonts and no newly reinvaded forms at 48 h (Fig. 5B). Residual dead parasites were visible after BrO removal (Fig. 5B), but no live parasites could be detected in the culture even after three full cycles without the inhibitor (not shown).

To confirm that BrO disrupts the lipoate-scavenging pathway, we analysed the incorporation of exogenously supplied [35S]-lipoate into P. falciparum proteins in BrO-treated cultures. Asynchronous parasites were cultured for 2 days in a medium containing the radiolabelled lipoate, in the absence or in the presence of 100 μM and 400 μM BrO, and parasite extracts were analysed by autoradiography. BrO treatment reduced the incorporation of [35S]-lipoate into parasite proteins in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5C, upper left panel, lanes 1–3). In contrast, it did not affect the incorporation of [35S]-cysteine in parallel cultures (Fig. 5C, upper right panel, lanes 4–6), demonstrating that the lipoate analogue does not significantly interfere with nutrient uptake and protein synthesis in general. In addition, Western blot analysis using antibodies that recognize P. falciparum heat shock protein 70 (_Pf_HSP70) confirmed that the reduction in [35S]-lipoate-labelled proteins does not reflect a general decrease in protein content due to parasite death (Fig. 5C, lower panels).

Collectively, these results strongly suggest that disruption of the lipoate-scavenging pathway is lethal to P. falciparum erythrocytic stages in vitro.

Discussion

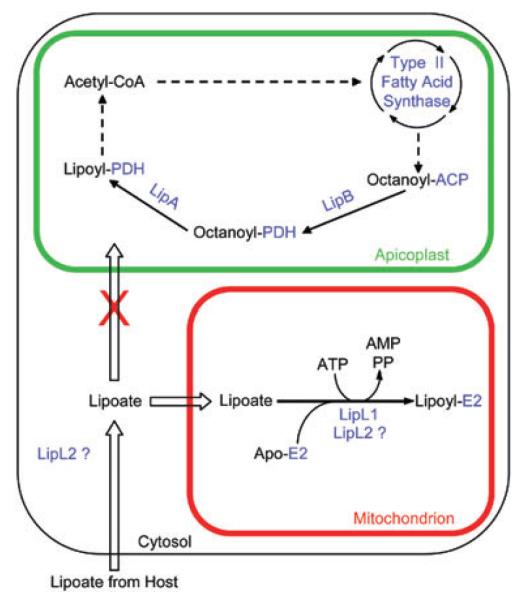

Protein lipoylation is a ubiquitous phenomenon and may proceed from biosynthesis and/or scavenging. P. falciparum possesses four known lipoate acceptor proteins, the E2 subunits of PDH, KGDH and BCDH, and the H-protein of the glycine cleavage system. Using antiserum specific for lipoylated proteins, we identified in erythrocytic parasite extracts four labelled bands of the expected sizes, which suggests that all four parasite lipoate acceptor proteins are lipoylated. Western blot analysis confirmed that the larger band is the E2 subunit of PDH. The localization of P. falciparum PDH to the apicoplast (Foth et al., 2005) and the likely mitochondrial location of the three other proteins (Gunther et al., 2005; McMillan et al., 2005) predicts a requirement for lipoate in both organelles (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Model of lipoate metabolism in P. falciparum erythrocytic parasites. The scheme describes lipoate synthesis in the apicoplast and lipoate scavenging in the mitochondrion. Proteins are coloured blue. In the mitochondrion, ‘E2′ could represent the H-protein or the E2 subunits of BCDH or KGDH. The two putative locations of LipL2 are shown.

Plasmodium falciparum possesses genes for both lipoate biosynthesis and lipoate-scavenging pathways (Wrenger and Muller, 2004, and this study). In this report, we show that intraerythrocytic parasites can take up and incorporate radiolabelled lipoate from the external environment. This is the first direct demonstration of lipoate scavenging in P. falciparum. Lipoate is naturally present in the red blood cells (Constantinescu et al., 1995) and human serum, where lipoate is found at concentrations of 33–145 ng ml−1 (i.e. 160–700 nM) bound non-covalently to serum albumin, with a stoichiometry as high as 10:1 (Teichert and Preiss, 1992; Kawabata and Packer, 1994; Schepkin et al., 1994; Packer et al., 1995). Human serum albumin was shown to be imported directly into the parasite cytosol, bypassing the erythrocyte cytosol (El Tahir et al., 2003), which may provide a route for lipoate import. Alternatively, lipoate may enter the parasite through small molecule nutrient uptake mechanisms induced in the infected red blood cell (reviewed in Saliba and Kirk, 2001a). P. falciparum imports the essential nutrient pantothenate (Divo et al., 1985) using a H+-coupled transporter located on the parasite plasma membrane (Saliba and Kirk, 2001b). This transporter may also import lipoate, as is the case for the mammalian Na+-coupled multivitamin transporter, known to import biotin, lipoate and pantothenate (Prasad et al., 1998; Wang et al., 1999; Prasad and Ganapathy, 2000). Moreover, experiments using isolated mitochondria demonstrated the ability of this organelle to import lipoate (Tirosh et al., 2003).

Scavenged radiolabelled lipoate appears to be the substrate for lipoylation in the mitochondrion, but not the apicoplast. This implies that an independent pathway must exist in the apicoplast for the lipoylation of PDH. This conclusion is consistent with the demonstration that P. falciparum contains functional LipB and LipA homologues likely to be localized in the apicoplast (Wrenger and Muller, 2004). These enzymes could function as a lipoate synthesis pathway using octanoyl-ACP produced by fatty acid biosynthesis. This is reminiscent of lipoate metabolism in plants, where fatty acid biosynthesis provides substrate for PDH lipoylation in the chloroplast. However, unlike P. falciparum, plants also have lipoate biosynthesis and a PDH in the mitochondrion (Lernmark and Gardestrom, 1994; Mooney et al., 1999; Gueguen et al., 2000; Wada et al., 2001). In Toxoplasma gondii, two recent studies show that disruption of fatty acid synthesis either using the inhibitor triclosan (Crawford et al., 2006), or a knock-out of ACP (Mazumdar et al., 2006), results in the loss of lipoylation of PDH, highlighting the existence of a lipoate synthesis pathway in the apicoplast of this organism.

The genomes of P. falciparum and T. gondii have been reported to encode a protein with homology to the E. coli lipoate ligase LplA (Thomsen-Zieger et al., 2003; Wrenger and Muller, 2004). In this report, we identify a second P. falciparum LplA homologue, which is distantly related to the E. coli enzyme (12% sequence identity), but more closely related to LplA proteins from other bacteria (28% identity with Chlamydophila abortus LplA homologue). We designated the LplA orthologue lipoate ligase 1 (LipL1), and the newly identified gene LipL2. All available genomes of Plasmodium species contain genes encoding LipL1 and LipL2 proteins (Table 2). This phenomenon is not limited to Plasmodium, because LipL1 and LipL2 orthologues are also present in the genomes of the apicomplexan parasites Theileria parva, Theileria annulata and Toxoplasma gondii. LipL1 and LipL2 appear to define two families of lipoate ligase enzymes that may have a conserved role across these parasite species. This trend has not been described elsewhere. Some bacteria, such as Listeria monocytogenes (O’Riordan et al., 2003), also harbour two LplA enzymes, but in this case the two ligases are closely related paralogues with clear homology to E. coli LplA.

Why would the parasite need two lipoate ligases? Functional complementation in the lipoylation-deficient E. coli strain TM136 (LipB−, LplA−) show that both LipL1 and LipL2 are functional lipoate ligases capable of using free lipoate scavenged from the environment. LipL1 enzymatic activity was further confirmed in vitro using one of its potential biological substrates. As LipL1 is mitochondrial (Wrenger and Muller, 2004), it is a good candidate for lipoylating the KGDH, BCDH, and H-protein of the glycine cleavage system. The precise function of LipL2 in lipoate scavenging still needs to be established. Attempts to localize this protein by immunofluorescence using our polyclonal antibodies were so far unsuccessful. Interestingly, substrate specificity may explain the existence of two lipoate ligase enzymes in P. falciparum. The analysis of the TM136 E. coli complemented with LipL1 and LipL2 constructs shows that the two ligases have different substrate specificities, with LipL1 preferentially lipoylating E. coli KGDH, and LipL2 preferentially lipoylating E. coli PDH. Thus, it is possible that LipL1 and LipL2 also differ in their specificity towards P. falciparum lipoate acceptor substrates.

The lipoate analogue diselenolipoic acid (1,2-diselenolane-3-pentanoic acid) has been shown to inhibit the growth of E. coli by serving as a substrate for lipoate ligase LplA (Morris et al., 1994; Reed et al., 1994). Comparison of the effects of diselenolipoic acid with the lipoic acid analogues in which only one of the sulphur atoms was replaced by a selenium atom (6-seleno-8-thiooctanoic acid and 6-thio-8-selenooctanoic acid) suggested that the inability of the analogue to be reduced was essential for the production of non-functional α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes. Here, we show that the lipoate analogue BrO interferes with the lipoate ligase activity (and the octanoate ligase activity) of LipL1 in vitro. We also show that BrO inhibits parasite growth, as well as the incorporation of radiolabelled lipoate from the medium into P. falciparum proteins. Growth inhibition is counteracted by the addition of lipoate in the culture medium, suggesting that the mechanism of BrO inhibition is competitive versus exogenous lipoate. Based on our radiolabel incorporation studies, we have shown that exogenous lipoate is not trafficked to the apicoplast and attached to apicoplast proteins, and thus, exogenous lipoate would not rescue inhibition of lipoate biosynthesis. Taken together, these results show that BrO interferes with lipoate scavenging and that lipoate scavenging is essential for the survival of intraerythrocytic P. falciparum parasites.

Little effect on P. falciparum growth is observed during the first 48 h (about one life cycle) of incubation with 400 μM BrO (Fig. 5A). During this time, BrO may interfere with several steps of lipoate scavenging, such as lipoate uptake into the parasite, trafficking to the mitochondrion, and incorporation into mitochondrial proteins. Indeed, it is likely that BrO is actively transported into the parasite (perhaps by the same transporter as lipoate) because a similar compound, octanoate, is not able to enter malaria parasites (Krishnegowda and Gowda, 2003). Once inside the parasite, BrO may compete with a pool of free lipoate. Analysis of radiolabelled parasites shows that, although the majority of intracellular lipoate is protein-bound, a small pool of free lipoate could exist (data not shown). While BrO may compete with lipoate for uptake and intracellular trafficking, it is likely that the ultimate mechanism of BrO toxicity is similar to that observed in E. coli – lipoate ligase enzymes attach BrO to lipoate acceptor proteins, irreversibly poisoning one or more essential enzyme complexes. Indeed, mass analysis of LipL1 reaction products shows that LipL1 is able to attach BrO to the H-protein in vitro. This mechanism is consistent with the slow onset of growth inhibition in asynchronous BrO-treated cultures, and with the irreversible nature of growth inhibition observed with synchronized cultures. The rate of accumulation of BrO-modified parasite proteins would be affected by such factors as: competition for uptake and trafficking, competition as a lipoate ligase substrate, and the turnover of lipoylated proteins. After 48 h of incubation with 400 μM BrO, these factors combine to reduce the incorporation of scavenged lipoate into acceptor proteins to significantly lower levels (Fig. 5C).

Despite the fundamental role that lipoate plays in the biology of most organisms, there appears to be a surprising diversity of strategies for lipoylating proteins (Yasuno and Wada, 2002; O’Riordan et al., 2003; Gardner et al., 2005; Pain et al., 2005). Here, we provide evidence supporting a novel arrangement in Plasmodium species, which contain an essential lipoate-scavenging pathway, with two lipoate ligase paralogues LipL1 and LipL2, but also retain a lipoate biosynthesis pathway in the apicoplast. The fact that lipoate scavenging is vital to the parasite implies that lipoate synthesized in the apicoplast is not used in the mitochondrion, or in any case, not at levels high enough to sustain parasite growth when the scavenging pathway is inhibited. In T. gondii, inhibition of apicoplast fatty acid synthesis does not visibly affect the lipoylation of mitochondrial proteins (Crawford et al., 2006; Mazumdar et al., 2006). However, T. gondii parasites are able to grow in lipoate-deficient medium, and it is not known if small amounts of synthesized lipoate (from the apicoplast) are used in the mitochondrion or if lipoate can be scavenged directly from the host cell (Crawford et al., 2006). Our study demonstrates that in P. falciparum lipoate biosynthesis and scavenging are independent from each other. The compartmentalization, both physical and functional, of these lipoylation pathways appears to have significant consequences on the parasite’s requirements for lipoate. Indeed, our results support the conclusion that, while possessing a lipoate biosynthesis pathway, P. falciparum is auxotrophic for lipoate.

The importance of lipoate scavenging for parasite survival highlights the major role of lipoylated α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes. Non-lipoylated and diselenolipoylated complexes are inactive, and it is very likely that complexes modified with BrO are similarly unable to perform vital metabolic functions. A potential antioxidant role of these enzymatic complexes (Muller, 2004), as demonstrated for the E2 and E3 subunits of the pathogenic bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Bryk et al., 2002), would similarly be affected. It will be of great interest to identify which of these lipoylated dehydrogenase complexes are required for parasite survival.

Experimental procedures

Data base searches and sequence analysis

The malaria genome resource PlasmoDB (Bahl et al., 2003) was used for BLAST homology searches to identify malaria lipoate ligase homologues and lipoate acceptor proteins. The possibility of a mitochondrial transit peptide in LipL2 was analysed using the PLASMIT (Bender et al., 2003) and MITOPROT (Claros and Vincens, 1996) prediction programs. Lipoate ligase signature domains were identified from the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2005). Amino acid sequence alignments were performed using the programs STRETCHER (Myers and Miller, 1988), SSEARCH 3.4 (Lipman and Pearson, 1985; Pearson and Lipman, 1988), or CLUSTALW 1.83 (Thompson et al., 1994) as indicated. For the P. vivax LipL2 homologue, the pairwise alignment was performed using a portion of the annotated sequence, deduced from CLUSTALW multiple alignment of P. falciparum, P. yoelii, P. berghei, P. chabaudi and P. vivax LipL1 and LipL2 homologues.

Western blotting

Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate poly-acrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 4–12% acrylamide gels. The gels were blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher and Schuell Bioscience) and further incubated with rabbit antiserum (Humphries and Szweda, 1998; Sasaki et al., 2000) specific for lipoylated proteins (1:10 000, EMD Biosciences), rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for the E2 subunit of the P. falciparum PDH (1:500, a kind gift from Geoff McFadden), or mouse polyclonal antibodies specific for _Pf_HSP70 (1:2000, a kind gift from Nirbhay Kumar). Donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin or sheep anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:5000, Amersham Biosciences) were used for detection with the Supersignal® West Pico chemiluminescence kit (Pierce).

Cloning of parasite genes and construction of expression plasmids

The genes encoding LipL1, LipL2 and the H-protein were amplified by PCR from cDNA of a mixed population of strain 3D7 Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages. PCR products of the LipL1 and LipL2 genes were ligated into the pET100-TOPOD vector (Invitrogen), generating plasmids pMA005 and pMA002 respectively. The amplicon encoding the H-protein was ligated into pBluescript SK+ (Stratagene) digested with EcoRI and HindIII, to generate plasmid pMA007. Expression plasmids encoding the LipL1, LipL2 and H-protein constructs were generated from plasmids pMA005, pMA002 and pMA007. Nucleotides encoding amino acids 20–408 of LipL1 (LipL120) were amplified and the resulting amplicon was digested with MunI and PstI, followed by ligation into the pMAL_cHT vector (Muench et al., 2003) digested with EcoRI and PstI, generating pMA006. Nucleotides encoding full-length LipL2 (LipL2FL) and a putative mitochondrial product (LipL229, residues 29–356) were amplified and the resulting amplicons were digested with EcoRI and PstI, followed by ligation into pMAL_cHT digested with the same endonucleases, generating plasmids pMA003 and pMA004 respectively. Plasmid pMA007 was digested with EcoRI and HindIII to obtain the PfH-protein insert, which was then ligated into pMAL_cHT digested with the corresponding restriction enzymes, generating pMA008. Nucleotides encoding the E. coli H-protein (amino acids 2–130) were amplified from plasmid pNMN108 (Cicchillo et al., 2004) and the resulting amplicon was digested with EcoRI and HindIII, followed by ligation into pLZ_cH (MalE gene of pMAL_cHT replaced with the amino acids MRGS) digested with the same endonucleases, generating plasmid pLZ002.

TM136 bacterial strain, culture media and functional complementation

The E. coli null mutant strain TM136, deficient in lipoylation activity (Morris et al., 1994), was grown in YT medium containing 50 μgml−1 kanamycin and 15 μg ml−1 tetracycline, and supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) glucose as a carbon source. Sodium succinate (10 mM) and sodium acetate (10 mM) were added to bypass the requirement for KGDH activity and PDH activity respectively. For complementation studies, TM136 cells were transformed with pMA006, pMA003, pMA004 or empty pMAL_cHT vector as control. Transformants were selected using 50 μg ml−1 ampicillin and further grown in E minimal medium (Davis et al., 1980) supplemented with 0.4% glucose, 7.5 μg ml−1 FeSO4, 1 mg ml−1 vitamin-free casein hydrolysate, 2 μg ml−1 thiamine, 10 mM sodium succinate and 10 mM sodium acetate (TM136 medium), containing the three antibiotics above. After cultures reached an OD600 between 0.7 and 1.3, cells were pelleted and washed twice in medium free of succinate and acetate. After equilibration in this medium for 1 h, cells were inoculated at a starting OD600 of 0.01 in fresh medium in the presence or in the absence of 10 ng ml−1 lipoate. Culture growth at 37°C was assessed by measuring the OD600 after 48 h and 72 h.

Preparation of [35S]-lipoate

Biologically active _R_-[6,8-35S]-lipoate was prepared from E. coli overexpressing the E. coli H-protein as described in Appendix S1. The lipoate used in this report contained 0.4 ng μl−1 of _R_-lipoate with a specific activity of 34.2 Ci mmol−1.

Parasite culture and lipoate incorporation

Plasmodium falciparum (strain 3D7) asexual blood stages were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) containing human erythrocytes at 2% haematocrit, and supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 12.5 μg ml−1 hypoxanthine, 0.24% NaHCO3 and 10% human serum (Trager and Jensen, 1997). When indicated, parasites were synchronized by Sorbitol treatment (Lambros and Vanderberg, 1979). For lipoate incorporation experiments, 5 ml of cultures was maintained in the medium described above with a 5% haematocrit and a starting parasitaemia of 0.5%. Culture medium was changed daily and included 0.3 μCi ml−1 of [35S]-lipoate (2 ng ml−1 of bioactive _R_-lipoate). Thin blood smears of cultures were made daily and were Giemsa-stained to assess culture status and parasitaemia. Labelled parasites were harvested after 72 h as follows. Red blood cells were harvested by centrifugation at 445 g for 5 min, washed three times with ice-cold PBS, and lysed with 0.2% saponin for 3 min on ice. Red blood cell membranes and parasites were then pelleted at 5000 g for 5 min. Pellets were then washed two times with PBS, resuspended in gel loading buffer, and the equivalent of 700 μl of culture was analysed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

Plasmid pMA006 (encoding LipL120) was transformed into BL21-Star(DE3) cells (Invitrogen) cotransformed with the pRIL plasmid isolated from BL21-CodonPlus(DE3) cells (Stratagene) and a plasmid encoding the Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease (Kapust and Waugh, 2000). These cells produce LipL120 fused to an amino-terminal maltose binding protein (MBP). Constitutively expressed TEV protease catalyses in vivo cleavage of MBP, liberating the malaria protein with an amino-terminal six-histidine tag (Muench et al., 2003). Transformed cells were grown to mid-log phase and the expression of recombinant proteins was induced by the addition of 0.4 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested after growth for 10 h at 20°C. LipL120 was purified by metal chelate chromatography followed by cation exchange chromatography and gel filtration. Plasmid pMA008 encoding PfH-protein and plasmid pLZ002 encoding EcH-protein were transformed into E. coli strain TM136. These cells were grown in TM136 medium described above with 25 μg ml−1 (for pMA008) or 50 μg ml−1 (for pLZ003) ampicillin. Transformed cells were grown to mid-log phase and the expression of recombinant H-proteins was induced by the addition of 0.1 mM (for pMA008) or 0.4 mM (for pLZ002) IPTG. Cells were harvested after growth for 10 h at 20°C. Apo-PfH-protein was purified by amylose affinity chromatography and apo-EcH-protein was purified by metal chelate chromatography, followed by anion exchange chromatography.

Enzymatic assays and inhibition by BrO

For lipoate ligase activity, purified LipL120 (0.3 μM) was incubated in 100 mM Na/K Phosphate buffer (pH 7) containing 1.8 mM ATP, 1.8 mM MgCl2 and 120 μM DTT, in the presence of 180 μM lipoate and H-protein substrates: PfH-protein (1.8 μM) or EcH-protein (2 μM). After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the reactions were analysed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using antiserum specific for lipoylated proteins. For octanoate ligase activity, purified LipL120 (3 μM) was assayed as above with 72 μM [1-14C]-octanoate as a fatty acid substrate (American Radiolabeled Chemical, specific activity 53 mCi mmol−1) and 10 μM Pf or Ec H-protein, at 30°C for 20 min. The reactions were then analysed by SDS-PAGE, and octanoylated proteins were detected by autoradiography. The effect of BrO on LipL1 lipoylation and octanoylation activity was assessed by adding the inhibitor, dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) at the concentrations indicated, in the conditions described above using apo-PfH-protein as a substrate. For the lipoylation activity, the intensity of the chemiluminescence signal was measured by densitometry and expressed as percentage inhibition as compared with the activity of the control reaction containing the solvent only. For the octanoylation activity, after the reaction, proteins were precipitated with 10% tricarboxylic acid (TCA), washed twice in 10% TCA, and then resuspended in scintillation fluid. The radioactivity associated with protein-bound octanoate was determined by scintillation counting.

Inhibition of parasite growth by BrO

Eight parallel 5 ml P. falciparum cultures of asynchronous parasites were maintained in the culture medium described above. The cultures were initiated with a starting parasitaemia of 0.09%. Each culture contained 5 μl of DMSO or BrO-dissolved DMSO. In addition, each culture contained 5 μl of ethanol or _R,S_-lipoate (Sigma) dissolved in ethanol. The medium was changed daily, maintaining the concentrations of BrO (0, 25, 100 or 400 μM) and additional lipoate (0 or 2 μM) in each culture. On a daily basis, thin blood smears of cultures were Giemsa-stained to assess culture status and parasitaemia. Synchronized cultures were also grown in the presence of 0 μM, 400 μM and 1 mM BrO for 48 h starting at the ring stage, with daily medium change, then maintained in the absence of BrO for several days as indicated. Cultures morphology and parasitaemia were assessed on Giemsa-stained blood smears. To examine the effects of BrO on exogenous lipoate incorporation, asynchronous parasites were cultured for 48 h with 0, 100 and 400 μM BrO in the medium, in the presence of 35S-lipoate (0.9 μCi ml−1) or, as a control, 35S-cysteine (20 μCi ml−1, American Radiolabeled Chemicals). Cultures were harvested and parasite protein extracts analysed for incorporation by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. Parasite samples were also analysed by Western blotting and probed with the anti-_Pf_HSP70 antibody.

Supplementary Material

S1

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to John Cronan for lipoylation-deficient E. coli strains and helpful discussions, Luke Szweda for antiserum specific for lipoylated proteins, Lucy Stimmler and Geoff McFadden for the anti-Pf PDH E2 antibodies, Nirbhay Kumar for the anti-PfHSP70 antibodies, and Squire Booker for plasmid pNMN108. We also thank Drs Mae Huynh and Isabelle Coppens for critical reading of an early version of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute and the NIH (AI065853).

Footnotes

Re-use of this article is permitted in accordance with the Creative Commons Deed, Attribution 2.5, which does not permit commercial exploitation.

Supplementary material The following supplementary material is available for this article online: Appendix S1. Supplementary experimental procedures. This material is available as part of the online article from http://www.blackwell-synergy.com

References

- Bahl A, Brunk B, Crabtree J, Fraunholz MJ, Gajria B, Grant GR, et al. PlasmoDB: the Plasmodium genome resource. A database integrating experimental and computational data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:212–215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A, van Dooren GG, Ralph SA, McFadden GI, Schneider G. Properties and prediction of mitochondrial transit peptides from Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;132:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker SJ. Unraveling the pathway of lipoic acid biosynthesis. Chem Biol. 2004;11:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk R, Lima CD, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Nathan C. Metabolic enzymes of mycobacteria linked to antioxidant defense by a thioredoxin-like protein. Science. 2002;295:1073–1077. doi: 10.1126/science.1067798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunik VI. 2-Oxo acid dehydrogenase complexes in redox regulation. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:1036–1042. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchillo RM, Iwig DF, Jones AD, Nesbitt NM, Baleanu-Gogonea C, Souder MG, et al. Lipoyl synthase requires two equivalents of S-adenosyl-L-methionine to synthesize one equivalent of lipoic acid. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6378–6386. doi: 10.1021/bi049528x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claros MG, Vincens P. Computational method to predict mitochondrially imported proteins and their targeting sequences. Eur J Biochem. 1996;241:779–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu A, Pick U, Handelman GJ, Haramaki N, Han D, Podda M, et al. Reduction and transport of lipoic acid by human erythrocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:253–261. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00084-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford MJ, Thomsen-Zieger N, Ray M, Schachtner J, Roos DS, Seeber F. Toxoplasma gondii scavenges host-derived lipoic acid despite its de novo synthesis in the apicoplast. EMBO J. 2006;25:3214–3222. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RW, Botstein D, Roth JR. Advanced Bacterial Genetics: A Manual for Genetic Engineering. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Divo AA, Geary TG, Davis NL, Jensen JB. Nutritional requirements of Plasmodium falciparum in culture. I. Exogenously supplied dialyzable components necessary for continuous growth. J Protozool. 1985;32:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1985.tb03013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douce R, Bourguignon J, Neuburger M, Rebeille F. The glycine decarboxylase system: a fascinating complex. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01892-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Tahir A, Malhotra P, Chauhan VS. Uptake of proteins and degradation of human serum albumin by Plasmodium falciparum-infected human erythrocytes. Malar J. 2003;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foth BJ, Stimmler LM, Handman E, Crabb BS, Hodder AN, McFadden GI. The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum has only one pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, which is located in the apicoplast. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:39–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara K, Okamura-Ikeda K, Motokawa Y. Chicken liver H-protein, a component of the glycine cleavage system. Amino acid sequence and identification of the N epsilon-lipoyllysine residue. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:8836–8841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara K, Toma S, Okamura-Ikeda K, Motokawa Y, Nakagawa A, Taniguchi H. Crystal structure of lipoate-protein ligase A from Escherichia coli. Determination of the lipoic acid-binding site. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33645–33651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner MJ, Bishop R, Shah T, de Villiers EP, Carlton JM, Hall N, et al. Genome sequence of Theileria parva, a bovine pathogen that transforms lymphocytes. Science. 2005;309:134–137. doi: 10.1126/science.1110439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueguen V, Macherel D, Jaquinod M, Douce R, Bourguignon J. Fatty acid and lipoic acid biosyn-thesis in higher plant mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5016–5025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.5016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther S, McMillan PJ, Wallace LJ, Muller S. Plasmodium falciparum possesses organelle-specific alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes and lipoylation pathways. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:977–980. doi: 10.1042/BST20050977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries KM, Szweda LI. Selective inactivation of alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase: reaction of lipoic acid with 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15835–15841. doi: 10.1021/bi981512h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan SW, Cronan JE., Jr The Escherichia coli lipB gene encodes lipoyl (octanoyl)-acyl carrier protein: protein transferase. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1582–1589. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.5.1582-1589.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapust RB, Waugh DS. Controlled intracellular processing of fusion proteins by TEV protease. Protein Expr Purif. 2000;19:312–318. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata T, Packer L. Alpha-lipoate can protect against glycation of serum albumin, but not low density lipoprotein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:99–104. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DJ, Kim KH, Lee HH, Lee SJ, Ha JY, Yoon HJ, Suh SW. Crystal structure of lipoate-protein ligase A bound with the activated intermediate: insights into interaction with lipoyl domains. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38081–38089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnegowda G, Gowda DC. Intraerythrocytic Plasmodium falciparum incorporates extraneous fatty acids to its lipids without any structural modification. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;132:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambros C, Vanderberg JP. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J Parasitol. 1979;65:418–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lernmark U, Gardestrom P. Distribution of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activities between chloroplasts and mitochondria from leaves of different species. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1633–1638. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman DJ, Pearson WR. Rapid and sensitive protein similarity searches. Science. 1985;227:1435–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.2983426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu JZ, Lee PJ, Waters NC, Prigge ST. Fatty acid synthesis as a target for antimalarial drug discovery. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2005;8:15–26. doi: 10.2174/1386207053328192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan PJ, Stimmler LM, Foth BJ, McFadden GI, Muller S. The human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum possesses two distinct dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenases. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Cherukuri PF, DeWeese-Scott C, Geer LY, Gwadz M, et al. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for protein classification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D192–D196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar J, Wilson EH, Masek K, Hunter CA, Striepen B. Apicoplast fatty acid synthesis is essential for organelle biogenesis and parasite survival in Toxoplasma gondii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13192–13197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603391103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JR, Busby RW, Jordan SW, Cheek J, Henshaw TF, Ashley GW, et al. Escherichia coli LipA is a lipoyl synthase: in vitro biosynthesis of lipoylated pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from octanoyl-acyl carrier protein. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15166–15178. doi: 10.1021/bi002060n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney BP, Miernyk JA, Randall DD. Cloning and characterization of the dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase subunit of the plastid pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (E2) from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:443–452. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris TW, Reed KE, Cronan JE., Jr Identification of the gene encoding lipoate-protein ligase A of Escherichia coli. Molecular cloning and characterization of the lplA gene and gene product. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16091–16100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris TW, Reed KE, Cronan JE., Jr Lipoic acid metabolism in Escherichia coli: the lplA and lipB genes define redundant pathways for ligation of lipoyl groups to apoprotein. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1–10. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.1-10.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muench SP, Rafferty JB, McLeod R, Rice DW, Prigge ST. Expression, purification and crystallization of the Plasmodium falciparum enoyl reductase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:1246–1248. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903008813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S. Redox and antioxidant systems of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1291–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers EW, Miller W. Optimal alignments in linear space. Comput Appl Biosci. 1988;4:11–17. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/4.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawa H, Brady WT, Koike M, Reed LJ. Studies on the nature of protein bound lipoic acid. J Am Chem Soc. 1960;82:896–903. [Google Scholar]

- O’Riordan M, Moors MA, Portnoy DA. Listeria intracellular growth and virulence require host-derived lipoic acid. Science. 2003;302:462–464. doi: 10.1126/science.1088170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer L, Witt EH, Tritschler HJ. Alpha-lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19:227–250. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00017-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pain A, Renauld H, Berriman M, Murphy L, Yeats CA, Weir W, et al. Genome of the host-cell transforming parasite Theileria annulata compared with T. parva. Science. 2005;309:131–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1110418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson WR, Lipman DJ. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perham RN. Swinging arms and swinging domains in multifunctional enzymes: catalytic machines for multi-step reactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:961–1004. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilatz S, Breitbach K, Hein N, Fehlhaber B, Schulze J, Brenneke B, et al. Identification of Burkholderia pseudomallei genes required for the intracellular life cycle and in vivo virulence. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3576–3586. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01262-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad PD, Ganapathy V. Structure and function of mammalian sodium-dependent multivitamin transporter. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2000;3:263–266. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad PD, Wang H, Kekuda R, Fujita T, Fei YJ, Devoe LD, et al. Cloning and functional expression of a cDNA encoding a mammalian sodium-dependent vitamin transporter mediating the uptake of pantothenate, biotin, and lipoate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7501–7506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reche P, Perham RN. Structure and selectivity in post-translational modification: attaching the biotinyllysine and lipoyl-lysine swinging arms in multifunctional enzymes. EMBO J. 1999;18:2673–2682. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.10.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ. Chemistry and function of lipoic acid. In: Florkin M, Stotz EH, editors. Comprehensive Biochemistry. vol. 14. Elsevier; New York: 1966. pp. 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ, Hackert ML. Structure-function relationships in dihydrolipoamide acyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:8971–8974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed KE, Morris TW, Cronan JE., Jr Mutants of Escherichia coli K-12 that are resistant to a selenium analog of lipoic acid identify unknown genes in lipoate metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3720–3724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliba KJ, Kirk K. Nutrient acquisition by intracellular apicomplexan parasites: staying in for dinner. Int J Parasitol. 2001a;31:1321–1330. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliba KJ, Kirk K. H+-coupled pantothenate transport in the intracellular malaria parasite. J Biol Chem. 2001b;276:18115–18121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki M, Ansari A, Pumford N, van de Water J, Leung PS, Humphries KM, et al. Comparative immunoreactivity of anti-trifluoroacetyl (TFA) antibody and anti-lipoic acid antibody in primary biliary cirrhosis: searching for a mimic. J Autoimmun. 2000;15:51–60. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2000.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepkin V, Kawabata T, Packer L. NMR study of lipoic acid binding to bovine serum albumin. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1994;33:879–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichert J, Preiss R. HPLC-methods for determination of lipoic acid and its reduced form in human plasma. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1992;30:511–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen-Zieger N, Schachtner J, Seeber F. Apicomplexan parasites contain a single lipoic acid synthase located in the plastid. FEBS Lett. 2003;547:80–86. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00673-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirosh O, Shilo S, Aronis A, Sen CK. Redox regulation of mitochondrial permeability transition: effects of uncoupler, lipoic acid and its positively charged analog LA-plus and selenium. Biofactors. 2003;17:297–306. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520170129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trager W, Jensen JB. Continuous culture of Plasmodium falciparum: its impact on malaria research. Int J Parasitol. 1997;27:989–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Boom TJ, Reed KE, Cronan JE., Jr Lipoic acid metabolism in Escherichia coli: isolation of null mutants defective in lipoic acid biosynthesis, molecular cloning and characterization of the E. coli lip locus, and identification of the lipoylated protein of the glycine cleavage system. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6411–6420. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6411-6420.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada M, Yasuno R, Jordan SW, Cronan JE, Jr, Wada H. Lipoic acid metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana: cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding lipoyltransferase. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:650–656. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller RF, Reed MB, Cowman AF, McFadden GI. Protein trafficking to the plastid of Plasmodium falciparum is via the secretory pathway. EMBO J. 2000;19:1794–1802. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Huang W, Fei YJ, Xia H, Yang-Feng TL, Leibach FH, et al. Human placental Na+-dependent multivitamin transporter. Cloning, functional expression, gene structure, and chromosomal localization. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14875–14883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrenger C, Muller S. The human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum has distinct organelle-specific lipoylation pathways. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:103–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuno R, Wada H. The biosynthetic pathway for lipoic acid is present in plastids and mitochondria in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2002;517:110–114. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Miller JR, Jiang Y, Marletta MA, Cronan JE. Assembly of the covalent linkage between lipoic acid and its cognate enzymes. Chem Biol. 2003;10:1293–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

S1