A p53-dependent mechanism underlies macrocytic anemia in a mouse model of human 5q− syndrome (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Jul 1.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Med. 2009 Nov 22;16(1):59–66. doi: 10.1038/nm.2063

Abstract

The identification of the genes associated with chromosomal translocation breakpoints has fundamentally changed our understanding of the molecular basis of hematological malignancies. By contrast, the study of chromosomal deletions has been hampered by the large number of genes deleted and the complexity of their analysis. We report the generation of a mouse model for the human 5q− syndrome using large-scale chromosomal engineering. Haploinsufficiency of the Cd74 – Nid67 interval (containing the Ribosomal protein S14 gene – Rps14) causes macrocytic anemia, prominent erythroid dysplasia and monolobulated megakaryocytes in the bone marrow. This is associated with defective bone marrow progenitor development, increased apoptosis and the appearance of bone marrow cells expressing high levels of p53. Notably, intercrossing with p53-deficient mice, completely rescues the progenitor cell defect, restoring CMP/MEP, GMP and HSC bone marrow populations. This novel mouse model suggests that a p53-dependent mechanism underlies the pathophysiology of the 5q− syndrome.

5q− syndrome was first described in 1974 by Van den Berghe who reported the consistent association of the deletion of the long arm of chromosome 5 [del(5q)] with hematological abnormalities: macrocytosis, anemia, normal or high platelet count and hypolobulated megakaryocytes in the bone marrow1. The disease has a female preponderance and a low rate of transformation to acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) although most patients become transfusion dependent resulting in significant morbidity2. Recently, the immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide has been shown to induce cytogenetic remission3, though its mode of action remains to be fully determined.

The 5q− syndrome is recognized as a distinct clinical entity according to the WHO classification and is defined by a medullary blast count of < 5% and the presence of the del(5q) as the sole karyotypic abnormality4. The deletion involved in 5q− syndrome is typically a large interstitial deletion and contains a number of genes involved in hematopoiesis5. The del(5q) is also commonly found in other myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and AML (10-15% of all patients) although it is cytogenetically indistinguishable across these disorders. The del(5q) in the 5q− syndrome is widely believed to mark the location for a tumour suppressor gene(s), the loss of which may affect important processes such as growth control and normal hematopoiesis5,6.

Boultwood et al., first identified the commonly deleted region (CDR) in 5q− syndrome, based on fine mapping of patients with cytogenetically small deletions7, and subsequently narrowed the CDR to approximately 1.5 Mb between 5q31 and 5q32, flanked by D5S413 and the GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR ALPHA-1 (GLRA1) gene8. The CDR contains 24 known and 16 predicted genes, 33 of which were found to be expressed in CD34+ cells, and represent potential candidate genes8. The 5q− syndrome CDR is distinct from a more proximal 5q− CDR which has been associated with more advanced MDS and AML9.

To date, studies have failed to identify mutations within the retained alleles, or potential submicroscopic homozygous deletions in the CDR10. This suggests that either haploinsufficiency promotes the 5q− syndrome, or that a retained tumour suppressor allele has undergone epigenetic inactivation11,12.

Several potential candidate genes for the 5q− syndrome map within the CDR including: FAT TUMOUR SUPPRESSOR HOMOLOG 2 (FAT2), a homologue of the Drosophila fat tumour suppressor protein8; SECRETED PROTEIN ACIDIC AND RICH IN CYSTEINE (SPARC), a matricellular glycoprotein that is expressed primarily in tissues that undergo consistent turnover, or at sites of injury and disease13,14; and RIBOSOMAL PROTEIN 14 (RPS14)a component of the 40S ribosomal subunit. Haploinsufficiency of RPS14 has been described in CD34+ cells of patients with the 5q− syndrome10. Indeed, an RNA interference screen in CD34+ human hematopoietic progenitor cells identified RPS14 as a key factor in erythroid development _in vitro_15. These results suggested that 5q− syndrome might have an aetiology related to the RPS19-dependent pathology of Diamond Blackfan anemia (DBA)16.

Recently, Bagchi et al have demonstrated the use of chromosome engineering to identify the tumour suppressor gene CHROMODOMAIN HELICASE DNA BINDING PROTEIN 5 at human 1p3617, however, the only reported large-scale analysis of a targeted deletion of genes syntenic to human 5q− was a 450 kb region on mouse chromosome 11 (outside of the CDR of the 5q− syndrome), and this showed that the genes between Interferon regulatory factor 1 (Irf1) and Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (Csfgm) were not involved in 5q− syndrome18. To enable progress towards understanding the 5q− syndrome we applied our determination of the minimal CDR to the generation of a mouse model for human 5q− syndrome. This was achieved by a comprehensive chromosomal engineering approach to explore the region syntenic to the 5q− syndrome CDR for the presence of genes that alter normal hematopoiesis due to haploinsufficiency. Using Cre-loxP recombination to delete the syntenic regions in the mouse equivalent to the 5q− CDR we have generated a mouse model, with a deletion on chromosome 18 flanked by the Cd74 antigen (Cd74) gene and Nerve growth factor-induced differentiation clone 67 (Nid67) gene, that displays a macrocytic anemia, with dysplastic features in the bone marrow. Mechanistically, we found that these changes correlated with an increase in a population of highly p53 positive cells in the bone marrow and elevated apoptosis. Intercrossing of Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, LIM domain only 2 (Lmo2)Cre+ mice with Transformation related protein 53 (Trp53)−/− mice resulted in a reversal of the observed deficit in hematopoietic progenitor cell development, thereby demonstrating for the first time the mechanistic involvement of p53 in 5q− syndrome.

RESULTS

Cd74 - Nid67 interval deletion results in a 5q− syndrome-like phenotype

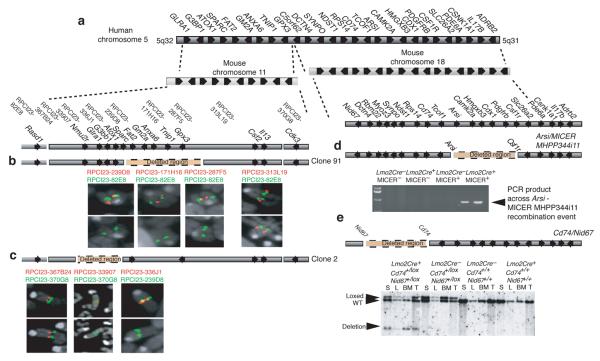

The CDR on the long arm of human chromosome 5 is divided into two regions of synteny on mouse chromosomes 11 and 18, with complete conservation of gene order and orientation (Fig. 1a). To narrow the CDR we generated a series of nested random deletions on chromosome 1119, from the Sparc gene, and ranging from a few kilobases to over 5 megabases (Supplementary Fig. 1a-c). Two deletions were selected for further analysis. Clone 91 contained a deletion extending from Sparc to beyond Glutathione peroxidase 3 (Gpx3), a deletion of at least 0.7 Mb, but less than 1.5 Mb (Fig. 1b). Clone 2 contained a deletion extending from Sparc to Neuromedin U 2 receptor (Nmu2r), a deletion of approximately 0.5 Mb (Fig. 1c). In combination these deletions removed all of the genes mapping to the syntenic region on mouse chromosome 11 that are commonly deleted in 5q− syndrome8. However, we observed no appreciable changes in the hematopoietic system (Supplementary Fig. 1d,e and data not shown) in heterozygote mice carrying these deletions even at 12 – 14 months of age. We were unable to generate homozygous mice for either deletion (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Representation of human 5q− syndrome CDR in humans and alignment with mouse regions of synteny. (a) The human 5q− syndrome CDR aligned with mouse chromosomes 11 and 18. (b) Confirmation of Clone 91 using FISH. (c) Confirmation of Clone 2 using FISH. (d) Confirmation of the Arsi – micerMHPP344i11 deletion by PCR analysis (see also Supplementary Fig. 3). (e) Confirmation of the Cd74 – Nid67 deletion by Southern analysis (see also Supplementary Fig. 4). S, spleen; L, liver; BM, bone marrow; T, tail. WT, wildtype. Arrows indicate the transcriptional orientation of the genes. The BAC clones and dye colours (red or green) used for FISH are marked in their relative positions.

Within this region both Sparc and Fat2 have been proposed as candidate genes for 5q− syndrome8,14. To assess their role in hematopoiesis we generated both _Sparc_−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a-c) and _Fat2_−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 2a-c). We found no evidence for Sparc or Fat2 playing roles in the development of red blood cells (RBC) or platelets (Supplementary Fig. 1f and data not shown).

The syntenic region on mouse chromosome 18 corresponding to the CDR defined in 5q− syndrome extends from Nid67 to Adrenergic beta-2-receptor (Adrb2) (Fig. 1a). We subdivided this region for the creation of deletions to avoid the Treacher Collins-Franceschetti syndrome 1 (Tcof1) gene, deletion of which has been reported to result in haplolethality 20. The deletion of the interval extending from Arylsulfatase i (Arsi) to MICER clone MHPP344i11 located in the Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (Csf1r) gene was achieved by targeting both genes in cis and intercrossing with Lmo2Cre knock-in mice21 (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3a-c), but failed to cause substantial changes in RBC numbers and hemoglobin levels (Supplementary Fig. 3d,e). By contrast deletion of the interval extending from Cd74 to Nid67, achieved by targeting loxP sites to both genes in cis (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 4a-c), and intercrossing with the Lmo2Cre knock-in mice resulted in striking perturbations to the hematopoietic system.

Deletion of the Cd74 – Nid67 interval causes macrocytic anemia

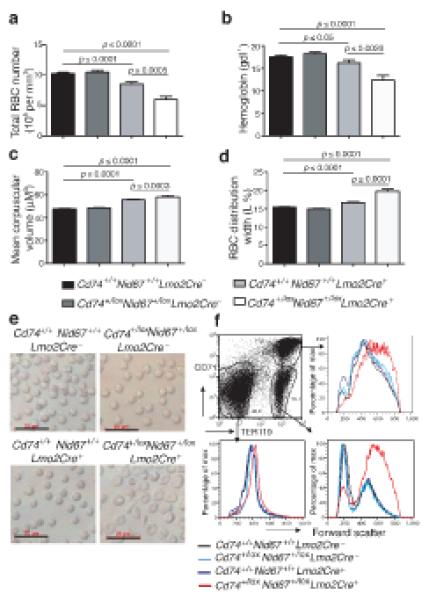

Blood parameters were analysed from cohorts of the four genotypes (Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice; Cd74+/+Nid67+/+, Lmo2Cre+ mice; Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, _Lmo2Cre_− mice; Cd74+/+Nid67+/+, _Lmo2Cre_− mice). We observed a striking 40 - 50% reduction in the numbers of circulating RBC in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice when compared to controls (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, hemoglobin levels were also significantly decreased (p ≤ 0.0020) in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice (Fig. 2b). This correlated with the appearance of pencil-shaped cells in the blood of the anaemic mice (Supplementary Fig. 5a).

Figure 2.

Deletion of the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox interval leads to macrocytic anemia. Blood from the specific genotypes was analysed (n = 28 – 52). (a) Red blood cell numbers. (b) Hemoglobin levels. (c) Mean corpuscular volume (MCV). (d) Red cell distribution width (RDW) (n = 28 – 52). (e) Live RBC imaged using light microscopy. Scale bar, 20 μm. (f) Bone marrow cells gated on CD71 and TER119 expression and analysed for forward scatter as a measure of cell size. Data are representative of two experiments with five mice per group.

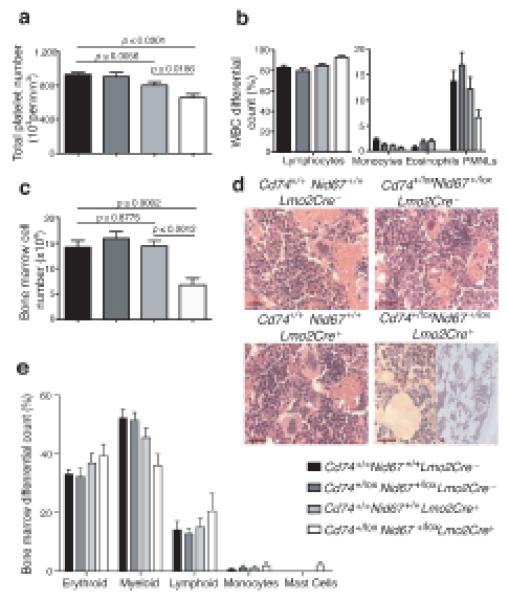

Mean corpuscular volume (Fig. 2c), mean RBC distribution width (Fig. 2d) and microscopy (Fig. 2e) showed RBC to have an increased size in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice. Flow cytometric analysis supported the development of macrocytes in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice, with cells in the TER119+ RBC populations in the bone marrow displaying increased cell size (Fig. 2f). These data indicate that the deletion of the Cd74 – Nid67 interval leads to macrocytic anemia, a key characteristic of 5q− syndrome. In addition we also observed modest thrombocytopenia in the blood of Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice (Fig. 3a), though a reduction in platelets was also observed in the Cd74+/+Nid67+/+, Lmo2Cre+ control mice (Fig. 3a) and statistical significance was not always attained (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Although blood lymphocyte and monocyte numbers were not reduced appreciably (Supplementary Fig. 5b,c), total granulocyte numbers were decreased in the blood of the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 5d), probably due to a deficit in eosinophils and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Blood and bone marrow cell proportions vary following deletion of the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox interval. (a) Platelet numbers in blood (n = 28 – 52). (b) Differential white blood cell counts (n = 5 per group). (c) Bone marrow cell numbers (n = 5 per group). Data are representative of at least two experiments. (d) Hematoxylin and eosin stained bone marrow sections. Scale bar, 20 μm. Representative of five mice per group all of similar age. (e) Bone marrow differential cell counts from cytospins (n = 8 - 10 per group).

Cd74 – Nid67 interval deletion impairs progenitor cell production

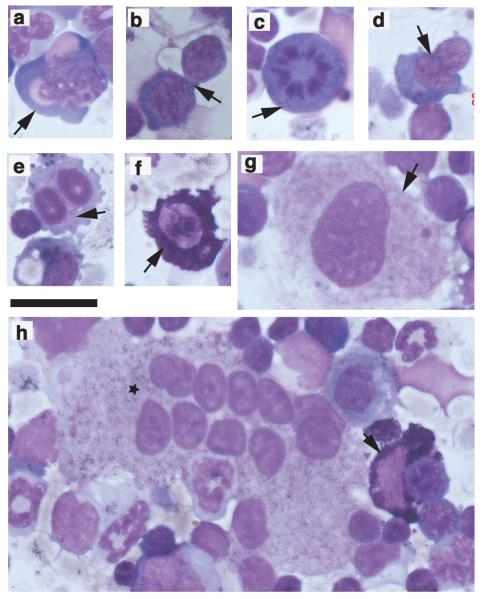

We observed a reproducible 50 – 60% reduction in the numbers of cells flushed from the femurs of the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice as compared to the controls (Fig. 3c), and the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ bone marrow sections ranged from mildly to highly hypocellular (Fig. 3d). Hypocellularity was due to decreases across the hematopoietic cell lineages, since the relative proportions of these cell types remained relatively similar for all genotypes (Fig. 3e). One notable exception to this was the elevation of mast cells in the bone marrow of Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice (Fig. 3e and 4f,h). The reason for the increased presence of these cells is unclear. However, the principle abnormalities observed were prominent dyserythropoiesis and monolobulation of the megakaryocytes in cytospins (Fig. 4a - h) and sections (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Giemsa-stained bone marrow cytospins following deletion of the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox interval to show prominent dyserythropoiesis, megakaryocytes with monolobulated nuclei and mast cells. Scale bar 40 μm. (a) dysplastic erythroblast (arrow); (b) inter-cytoplasmic bridging (arrow); (c) mitotic figure (arrow); (d) inter-nuclear bridging (arrow); (e) binucleate erythroid precursors (arrow); (f) mast cell (arrow); (g) megakaryocyte with monolobulated nucleus (arrow); (h) megakaryocyte with multiple monolobulated nuclei (star). Also includes a mast cell (arrow).

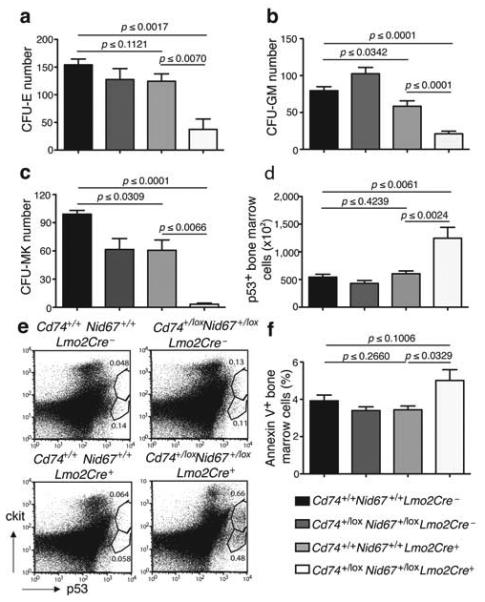

To ascertain if the reduction in peripheral RBC resulted from a deficit in the proliferation and differentiation of erythroid and myeloid progenitors we performed assays for colony forming unit-erythroid (CFU-E), CFU-granulocyte/macrophage (GM) and CFU-megakaryocyte (CFU-MK). The numbers of CFU-E (Fig. 5a), CFU-GM (Fig. 5b) and CFU-MK (Fig. 5c) were considerably depressed in the bone marrow of the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice. These data indicate that there is a deficit in the hematopoietic progenitor population following the deletion of the Cd74 – Nid67 interval. However, those progenitors that do differentiate, although greatly reduced, remain capable of populating the hematopoietic lineages in proportions similar to those in the control mice (Fig. 3e).

Figure 5.

Hematopoietic cell progenitors and p53 positive and apoptotic cells in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice. (a) Number of colony forming units – erythroid in bone marrow cultures (n = 5 per group). Data are representative of two experiments. (b) Number of colony forming units – granulocyte/macrophage in bone marrow cultures (n = 7 per group). (c) Number of colony forming units – megakaryocyte in bone marrow cultures (n = 3 per group). (d) Numbers of p53+ bone marrow cells (n = 5 per group). Representative of two similar experiments. (e) Intracellular staining for p53 in cKit+ cell surface stained cells. Example is of a highly p53-positive Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+, sample to show cKit+ cell involvement. (f) Annexin V staining of bone marrow cells (n = 5 per group).

Candidate genes in the Cd74 – Nid67 interval

The deleted Cd74 – Nid67 interval contains eight known genes encoding: CD74 (Cd74) an immunoregulatory protein; Rps14; N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase 1 (Ndst1) a heparin sulphate modifying enzyme; synaptopodin (Synpo) an actin-binding protein; myozenin 3 (Myoz3) a cytoskeletal component; RNA binding motif protein 22 (Rbm22) an RNA-binding protein; dynactin 4 (Dctn4) a cytoskeletal component; and Nid67.

We found no evidence for anemia or thrombocytopenia in blood samples from mice with heterozygous or homozygous deficiencies for _Ndst1_ 22 or _Cd74_ 23 (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). Of the remaining six genes Rps14, encoding a component of the 40S ribosome, has recently been reported to play a key role in 5q− syndrome _in vitro_ 15.

Cd74 – Nid67 interval deletion induces p53 expression and apoptosis

Dysregulation of ribosome biogenesis through insufficiency of ribosomal subunits has been demonstrated to activate a p53 checkpoint and regulate developmental pathways24-26. To determine if the haploinsufficiency of Rps14 (or its flanking neighbours) within the Cd74 – Nid67 interval could lead to the induction of p53 we assessed intracellular p53 levels in bone marrow cells. Significantly, a greater number of bone marrow cells (p ≤ 0.0024) from the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice stained for elevated p53, as compared to controls (Fig. 5d,e). In Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ samples that demonstrated elevated p53 expression, co-staining for cKit demonstrated that the p53-positive cells were predominantly cKitint suggesting that they may represent immature progenitor cells (Fig. 5e).

The stabilisation of p53 leads to cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis 27,28. To assess the levels of apoptosis in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice and their controls, bone marrow cells were stained with Annexin V. Annexin V staining was generally elevated amongst the bone marrow cells isolated from the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice as compared to the controls (Fig. 5f), though variation in staining due to the spectrum of disease, and very low frequency of the progenitor cells within the bone marrow, was observed.

These data suggest that elevated p53 in the hematopoietic progenitors of the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice induces cell death resulting in a deficit in the erythroid lineage.

Cd74 – Nid67 interval deletion causes progenitor cell deficiencies

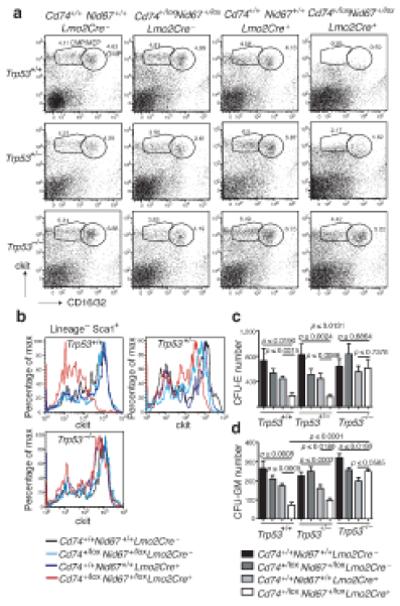

To assess the effect of deletion of the Cd74 - Nid67 interval on the development of specific hematopoietic progenitor populations we stained bone marrow for markers of common myeloid progenitors (CMP) and megakaryocytic-erythroid progenitors (MEP) (both lin−cKithighSca1−CD16/CD32low), and granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMP, lin−cKithighSca1−CD16/CD32high). Bone marrow from the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice had a striking deficit in the CMP/MEP and GMP lineages when compared to controls (Fig. 6a, top panels).

Figure 6.

Deletion of p53 reverses the progenitor cell deficits that result from the deletion of the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox interval. (a) Bone marrow cells stained for CMP, MEP and GMP cell surface markers (representative of five mice per group). (b) Bone marrow cells stained for HSC cell surface markers. Cells initially gated on Lin−Sca1+ (representative of five mice per group). (c) Number of colony forming units – erythroid in bone marrow cultures (n = 6 per group). (d) Number of colony forming units – granulocyte/macrophage in bone marrow cultures (n = 6 per group).

Analysis of the IL-7Rα−lin−cKithighSca1+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) also showed a notable scarcity of these cells in the bone marrow from the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice (Fig. 6b). Similar results were also observed in the spleen, though the proportion of progenitors was considerably lower (Supplementary Fig. 7a). The use of SLAM markers29 confirmed the reduction of HSC (CD150+CD48−CD244−) and more committed CD150−CD48− lineages (data not shown).

Inhibition of p53 rescues the deletion-induced progenitor deficit

To test whether inhibiting the p53 pathway would ameliorate the anemia and dysplasia observed in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice we intercrossed the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice with _Trp53_−/− mice. Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+, Trp53+/− mice were then crossed with Cd74+/+Nid67+/+ Trp53+/− mice to generate the twelve genotypes displayed in Figure 6. Absence of p53 from the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice completely reversed the deficit in the CMP/MEP and GMP populations that was observed in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+, Trp53+/+ mice (Fig. 6a lower panels), with heterozygous expression of p53 having an intermediate phenotype (Fig. 6a middle panels). Similarly, absence of p53 also resulted in complete rescue of HSC development in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice, again with heterozygous expression of p53 having an intermediate phenotype (Fig. 6b). Similar progenitor cell results were also observed in the spleen (Supplementary Fig. 7a).

CFU-E and CFU-GM assays were also undertaken with bone marrow from the twelve genotypes. Deletion of Trp53 completely rescued the CFU-E (Fig. 6c) and CFU-GM (Fig. 6d) activity in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ bone marrow. Similar results were also observed in the spleen (Supplementary Fig. 7b,c).

Due to a combined effect of the Lmo2Cre and Trp53 genotypes we were unable to determine a positive role for the inhibition of p53 in the reversal of RBC levels in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+, _Trp53_−/− mice (Supplementary Fig 8a). Similar results were also obtained for HGB (data not shown). However, we did find that ablation of p53 reversed the increased MCV observed in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+, _Trp53_−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Deletion of Trp53 also resulted in an increase in platelet levels, reversing the thrombocytopenia observed in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Moreover, the bone marrow dysplasia observed in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice was also reversed by the absence of p53 (data not shown). Thus modulation of p53 plays a critical role in maintaining the hematopoietic progenitor cells following deletion of the Cd74 – Nid67 interval, and that concurrent inhibition of p53 reverses many of the features induced by deletion of the Cd74 – Nid67 interval.

Discussion

We report for the first time the generation of a mouse model for a human myelodysplasia involving a large-scale chromosomal deletion: a mouse model for human 5q− syndrome. We have shown that segmental haploidy (generated using Cre-_loxP_-mediated chromosomal engineering) of a locus (or loci) residing in the interval between Cd74 and Nid67, syntenic with a region contained within the 5q− syndrome CDR, results in macrocytic anemia, a key feature of 5q− syndrome. Bone marrow cell morphology revealed prominent dysplasia within the erythroid lineage and monolobulated megakaryocytes. Bone marrow analysis demonstrated a marked reduction in erythroid and myeloid progenitors that correlated with the appearance of highly p53-positive bone marrow cells and elevated apoptosis, correlating with reduced cellularity. The results from a large study of patients with the 5q− syndrome by Giagounidis et al has shown that the cellularity of the marrow of patients with the 5q− syndrome is variable with 40% of patients showing a hypercellular marrow, 40% showing a normocellular marrow and 20% of patients showing a hypocellular marrow. Thus a proportion of patients with 5q− syndrome have a hypocellular marrow in accord with the hypocellular marrow observed in the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice2. Thus our mouse model exhibits important features of 5q− syndrome including macrocytic anemia, prominent dyserythropoiesis and monolobulated megakaryocytes.

To achieve deletion of the Cd74 – Nid67 interval in the hematopoietic lineage we used an Lmo2Cre mouse line as the Cre driver, since this is expressed in HSC (M. Metzler, R. Codrington, K. Akashi and T. H. Rabbitts, personal communication). Although we noted a mild, but reproducible, reduction of myeloid lineages in Lmo2Cre mice, probably due to offsite effects due to persistent high-level expression of Cre recombinase30, the phenotype of the deletion of the Cd74 – Nid67 interval was more profound than that of the Lmo2Cre controls.

Clearly haploinsufficiency of a gene(s) (or non-coding sequences) in this region underlies the macrocytic anemia and megakaryocyte dysplasia characteristic of 5q− syndrome. The Cd74 – Nid67 interval harbours eight known genes and we have excluded the individual involvement of Nsdt1 and Cd74, leaving Rps14, Synpo, Myoz3, Dctn4, Rbm22 and Nid67. Of these, the Rps14 gene is a strong candidate since it has been proposed, following an in vitro RNAi-screening approach, to play a role in 5q− syndrome15. Moreover, we have shown that haploinsufficiency of RPS14 in the hematopoietic stem cells of patients with the 5q− syndrome is associated with deregulated expression of multiple ribosomal- and translation-related genes31, further supporting the proposal that the 5q− syndrome represents a disorder of defective ribosome biogenesis.

The yeast Rps14 homologue is essential for the assembly of 40S ribosomal subunits32,33, although its specific function in the human remains largely unknown. Recent evidence has implicated aberrant ribosomal biogenesis in a number of diseases, including the bone marrow failure syndromes34. Mutation and resultant haploinsufficiency of a number of ribosomal genes, including those encoding structural components of both the large and small ribosomal subunits have been identified to underlie Diamond Blackfan anemia (DBA)16,35, a congenital disease characterised by macrocytic anemia36. Furthermore, it has also been suggested that defective ribosomal 60S subunit maturation caused by mutations in the Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome (SBDS) gene may underlie the hematological dysfunction characteristic of this disease37.

We observed that a population of bone marrow cells from the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice expressed higher levels of p53 than controls. The stabilisation of p53 is known to lead to apoptosis27 and we found that increased bone marrow cell apoptosis was also apparent in these mice. Our finding that introduction of the p53-deficient background into the Cd74+/loxNid67+/lox, Lmo2Cre+ mice completely reverses the observed deficit in bone marrow progenitors and ameliorates the thrombocytopenia in this model is important given the emerging evidence that ribosomal stress leads to activation of the p53 pathway25,26,38. For example, it has been shown that RPS19 deficiency in the zebrafish leads to developmental abnormalities and defective erythropoiesis through activation of the p53 protein family39. Recently, two mouse dark skin (Dsk) loci with mutations in Rps19 and Rps20 have been reported25. The underlying pathophysiology was shown to involve stabilization of p53 leading to cKit ligand expression and epidermal melanocytosis, indicating that p53 regulation may induce discrete phenotypes dependent on the cell type in which expression occurs. Another disorder involving ribosome biogenesis and p53 stabilisation is Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS). Haploinsufficiency of TCOF1 (encoding TREACLE, the protein mutated in TCS)40,41 perturbs mature ribosome biogenesis42, and this has been shown recently to result in the stabilization of p5324. Inhibition of p53 prevented apoptosis of neuroepithelial cells and rescued the cranioskeletal abnormalities associated with mutations in _Tcof1_ 24.

Our genetic data now implicate p53 in the molecular mechanism underlying 5q− syndrome. Interestingly, we have previously reported the up-regulation of multiple transcriptional targets of p53 in the hematopoietic stem cells of patients with the human 5q− syndrome, including WILD TYPE P53-INDUCED GENE 1 (WIG1), PLECKSTRIN HOMOLOGY-LIKE DOMAIN, FAMILY A, MEMBER 3 (PHLDA3), TNF RECEPTOR SUPERFAMILY, MEMBER 6 (FAS), BCL2-ASSOCIATED X PROTEIN (BAX), B-CELL LYMPHOMA/LEUKAEMIA 11B (BCL11B) and FERREDOXIN REDUCTASE (FDXR)10,31. Moreover, our pathway analysis using the DAVID gene ontology application (http://niaid.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) and these gene expression profiling data sets10,31 have shown that the p53 pathway is significantly up-regulated (p ≤ 0.024) in patients with the 5q− syndrome. As postulated for TCS, the ribosome biogenesis checkpoint that leads to activation of p53 function may also provide a therapeutic avenue for the treatment of the human 5q− syndrome, though this will only be possible if the pathway does not influence the key tumour suppressor role played by p53. It has been reported recently that disruption of 40S ribosome biogenesis leads to p53 induction through a ribosomal protein L11-translation-dependent mechanism that might be targeted therapeutically43.

Our data clearly identify an important chromosomal region for the development of macrocytic anemia, and would support a role for Rps14. Typically human MDS are associated with thrombocytopenia as in the mouse model presented here, although at diagnosis many patients with the human 5q− syndrome have normal or slightly elevated platelet counts. The explanation for this apparent difference is not known; it may be due to a human/mouse species difference or due to additional genetic abnormalities in the human. However, it is also possible that other genes in the Cd74 – Nid67 interval may play an additional role. For example Dctn4 encodes Dynactin 4, a subunit of the Dynactin complex that binds Dynein allowing the motor to migrate on the microtubule lattice. It has been reported that disruption of Dynactin/Dynein function can inhibit proplatelet elongation and this may reduce platelet formation44. However, our CFU-MK data suggest that it is a primary defect in megakaryocyte progenitor production that leads to thrombocytopenia. Rbm22 is highly conserved from yeast to human and has been proposed to be involved in RNA splicing45; aberrations in which have been linked to cancer46. Moreover, we have recently shown that patients with the 5q− syndrome show a marked reduction in the expression of RNA BINDING MOTIF PROTEIN 22 (RBM22)10. By contrast Synaptopodin, Myozenin 3 and Nid67 appear unlikely candidates47,48.

It is possible that additional genes within the CDR could have additive roles to those identified herein. Future studies using competitive cell transfers will help to clarify whether cells carrying the Cd74 – Nid67 deletion interval have a competitive survival advantage or whether other genes/mutations are responsible for clonal survival and outgrowth in 5q− syndrome.

We report the generation of the first mouse model of the human 5q− syndrome and the demonstration that a p53-dependent mechanism underlies this disorder. This animal model will enable the analysis of both emerging therapeutic compounds and the assessment of the mode of action of existing drugs such as lenalidomide. This study shows the feasibility of generating large-scale chromosomal deletions in mice for the genetic analysis of haploinsufficiency in myelodysplasia.

METHODS

Mouse strains

We obtained Cd74−/− mice23 from Jackson Labs. Trp53−/− mice were as described 49. Lmo2Cre knock-in mice were as described previously21. Mice were on a mixed 129 x C57BL/6 background. The methods for the generation of all the other mouse strains used in this study can be found in Supplementary Methods.

The mice analysed within each experiment were of similar age, genetic background and gender where possible. All animal experiments outlined in this report were undertaken with the approval of the UK Home Office.

Flow cytometry

We stained bone marrow cell suspensions for cell surface markers. Antibodies to mouse TER119, conjugated to FITC, (clone TER-119) and to mouse CD71, conjugated to PE, (clone C2) were used for the analysis of erythroid cells. For lineage markers antibodies against the following molecules were used all conjugated to FITC: mouse CD4 (clone H129.19), mouse CD3e (clone 145-2C11), mouse Ly-6G and Ly-6C (Gr-1) (clone RB6-8C5), mouse CD11b (Mac-1) (clone M1/70), mouse CD45R/B220 (clone RA3-6B2), mouse FcεR1 alpha (clone MAR-1), mouse CD8a (clone 53-6.7), mouse TER119/Erythroid cells (clone Ter119). For HSC markers antibodies to mouse Sca-1, conjugated to PE Cy7, (clone D7) and to mouse CD117 (cKit), conjugated to APC, (clone 2B8) were used. HSCs were defined as lineage−Sca-1+cKithigh. For the CMP population the following antibodies were used: mouse Sca-1 conjugated to PE-Cy7 (clone as above); mouse IL-7Rα conjugated to biotin (clone SB/199, subsequently stained with streptavidin PE Cy7); mouse CD117 (cKit) conjugated to APC (clone as above); mouse CD16/32 PE (clone 93). CMP/MEPs were defined as lineage−Sca-1/IL-7Rα−CD16/32lowcKithigh. GMPs were defined as lineage−Sca1/IL-7Rα−CD16/32highcKithigh.

For intracellular staining the cells were fixed and permeabilised, following manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences) and stained for p53 or an IgG1 isotype control (anti-p53 or IgG1 isotype conjugated to PE, BD Biosciences). Cells were stained at 1 × 106 cells per well and intracellular antibodies were added at 20 μl per well.

For Annexin V staining 1 × 106 bone marrow cells were analysed using the Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit 1 according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Pharmingen).

Colony forming cell assays

We collected femurs and flushed them using IMDM with 2% FBS (StemCell Technologies) to obtain bone marrow cells. Spleens were isolated and disrupted through a cell strainer, before red cells were lysed using ammonium chloride lysis. Bone marrow cells and splenocytes (2 × 105 cells per 35 mm dish) were plated in Methocult®-GF M3434 for CFU-GM assays and Methocult® M3334 for CFU-E assays (StemCell Technologies). For CFU-MK, 1 × 105 or 5 × 105 bone marrow cells were plated in Megacult®-C in the presence of recombinant human (rh) thrombopoietin, rm IL-3, rh IL-6, rh IL-11 following the protocol from StemCell Technologies. After six days in culture the CFU-MK colonies were stained for acetylcholinesterase as described in the instructions from StemCell Technologies.

Blood cell counts

We measured blood parameters such as RBC, mean corpuscular volume, red distribution width, hemoglobin concentration, platelet number and WBC using a Sci1 Vet abc Animal Blood Counter.

Differential cell counts

We collected blood samples into EDTA coated tubes. In some cases spiculation of the red cells was observed, but this did not correlate with specific genotypes. Blood smears or bone marrow cell (from flushed femurs) cytospin slides were stained with Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich), following the manufacturer's instructions. Differential cell counts were made blind on 100 cells per slide under oil and at a 63x magnification.

FISH

We treated ES cells with 0.1 μg/ml colcemid (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) for 90 minutes, trypsinised and resuspended in 75 mM KCl for 30 minutes. Cells were then washed four times in ice-cold fixative (3 parts methanol, 1 part acetic acid). Cell suspensions were dropped onto slides then put through an ethanol dilution series. FISH probes were produced from BAC DNA using a Roche DIG or BIOTIN nick translation kit (Roche Diagnostics, East Sussex, UK) as detailed in the manufacturer's instructions. Slides were denatured in 70% formamide at 65 °C, quenched in ice cold 70% ethanol, then dehydrated through an ethanol dilution series and air dried. The denatured probe mix (biotin-labelled BAC-1 DNA and DIG-labelled BAC-2 DNA, cot1 DNA and hybridisation buffer (Cambio, Cambridge, UK)) was added and hybridised at 42 °C for at least 16 hours. The slides were washed then incubated with either anti-digoxigenin or avidin, conjugated to fluorescein or rhodamine Fab fragments, dictated by the template for detection (Roche Diagnostics, East Sussex, UK). Slides were air dried and analyzed at 1,000X. Image analysis was performed using Smart Capture 2.1 software (Digital Scientific, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

Statistics

Student's _t_-test was used to determine statistical significance and two-tail p values are shown. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Supplementary Material

1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks go to members of the McKenzie lab for their comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to MRC-SABU staff especially Vernon Smith. We are also grateful to Kay Grobe (Munster, Germany) for providing blood from the Ndst1+/− mice, and Terry Rabbitts (Leeds Institute of Molecular Medicine, UK) for providing Lmo2Cre mice. A.N.J.M., D.R.H., S.L.A., A.L.L., J.S.W., J.B and A.J.W. were funded by Leukaemia Research UK.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Van den Berghe H, et al. Distinct hematological disorder with deletion of long arm of no. 5 chromosome. Nature. 1974;251:437–438. doi: 10.1038/251437a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giagounidis AA, Germing U, Wainscoat JS, Boultwood J, Aul C. The 5q- syndrome. Hematology. 2004;9:271–277. doi: 10.1080/10245330410001723824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.List A, et al. Lenalidomide in the myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1456–1465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002;100:2292–2302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boultwood J, Lewis S, Wainscoat JS. The 5q-syndrome. Blood. 1994;84:3253–3260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Beau MM, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular delineation of the smallest commonly deleted region of chromosome 5 in malignant myeloid diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5484–5488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boultwood J, et al. Molecular mapping of uncharacteristically small 5q deletions in two patients with the 5q- syndrome: delineation of the critical region on 5q and identification of a 5q- breakpoint. Genomics. 1994;19:425–432. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boultwood J, et al. Narrowing and genomic annotation of the commonly deleted region of the 5q- syndrome. Blood. 2002;99:4638–4641. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai F, et al. Transcript map and comparative analysis of the 1.5-Mb commonly deleted segment of human 5q31 in malignant myeloid diseases with a del(5q) Genomics. 2001;71:235–245. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boultwood J, et al. Gene expression profiling of CD34+ cells in patients with the 5q- syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:578–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soengas MS, et al. Inactivation of the apoptosis effector Apaf-1 in malignant melanoma. Nature. 2001;409:207–211. doi: 10.1038/35051606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teitz T, et al. Caspase 8 is deleted or silenced preferentially in childhood neuroblastomas with amplification of MYCN. Nat Med. 2000;6:529–535. doi: 10.1038/75007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brekken RA, Sage EH. SPARC, a matricellular protein: at the crossroads of cell-matrix. Matrix Biol. 2000;19:569–580. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehmann S, et al. Common deleted genes in the 5q- syndrome: thrombocytopenia and reduced erythroid colony formation in SPARC null mice. Leukemia. 2007;21:1931–1936. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebert BL, et al. Identification of RPS14 as a 5q- syndrome gene by RNA interference screen. Nature. 2008;451:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature06494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Draptchinskaia N, et al. The gene encoding ribosomal protein S19 is mutated in Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Nat Genet. 1999;21:169–175. doi: 10.1038/5951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagchi A, et al. CHD5 is a tumor suppressor at human 1p36. Cell. 2007;128:459–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Y, et al. Genomic interval engineering of mice identifies a novel modulator of triglyceride production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1137–1142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LePage DF, Church DM, Millie E, Hassold TJ, Conlon RA. Rapid generation of nested chromosomal deletions on mouse chromosome 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10471–10476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixon J, Brakebusch C, Fassler R, Dixon MJ. Increased levels of apoptosis in the prefusion neural folds underlie the craniofacial disorder, Treacher Collins syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1473–1480. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.10.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forster A, et al. Engineering de novo reciprocal chromosomal translocations associated with Mll to replicate primary events of human cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:449–458. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grobe K, et al. Cerebral hypoplasia and craniofacial defects in mice lacking heparan sulfate Ndst1 gene function. Development. 2005;132:3777–3786. doi: 10.1242/dev.01935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bikoff EK, et al. Defective major histocompatibility complex class II assembly, transport, peptide acquisition, and CD4+ T cell selection in mice lacking invariant chain expression. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1699–1712. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones NC, et al. Prevention of the neurocristopathy Treacher Collins syndrome through inhibition of p53 function. Nat Med. 2008;14:125–133. doi: 10.1038/nm1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGowan KA, et al. Ribosomal mutations cause p53-mediated dark skin and pleiotropic effects. Nat Genet. 2008;40:963–970. doi: 10.1038/ng.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panic L, et al. Ribosomal protein S6 gene haploinsufficiency is associated with activation of a p53-dependent checkpoint during gastrulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8880–8891. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00751-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warner JR, McIntosh KB. How common are extraribosomal functions of ribosomal proteins? Mol Cell. 2009;34:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danilova N, Sakamoto KM, Lin S. p53 family in development. Mech Dev. 2008;125:919–931. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiel MJ, et al. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loonstra A, et al. Growth inhibition and DNA damage induced by Cre recombinase in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9209–9214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161269798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pellagatti A, et al. Haploinsufficiency of RPS14 in 5q- syndrome is associated with deregulation of ribosomal- and translation-related genes. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferreira-Cerca S, Poll G, Gleizes PE, Tschochner H, Milkereit P. Roles of eukaryotic ribosomal proteins in maturation and transport of pre-18S rRNA and ribosome function. Mol Cell. 2005;20:263–275. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jakovljevic J, et al. The carboxy-terminal extension of yeast ribosomal protein S14 is necessary for maturation of 43S preribosomes. Mol Cell. 2004;14:331–342. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dokal I, Vulliamy T. Inherited aplastic anemias/bone marrow failure syndromes. Blood Rev. 2008;22:141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gazda HT, et al. Ribosomal protein S24 gene is mutated in Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:1110–1118. doi: 10.1086/510020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janov AJ, Leong T, Nathan DG, Guinan EC. Medicine. Vol. 75. Baltimore: 1996. Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Natural history and sequelae of treatment; pp. 77–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menne TF, et al. The Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome protein mediates translational activation of ribosomes in yeast. Nat Genet. 2007;39:486–495. doi: 10.1038/ng1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sulic S, et al. Inactivation of S6 ribosomal protein gene in T lymphocytes activates a p53-dependent checkpoint response. Genes Dev. 2005;19:3070–3082. doi: 10.1101/gad.359305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danilova N, Sakamoto KM, Lin S. Ribosomal protein S19 deficiency in zebrafish leads to developmental abnormalities and defective erythropoiesis through activation of p53 protein family. Blood. 2008;112:5228–5237. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valdez BC, Henning D, So RB, Dixon J, Dixon MJ. The Treacher Collins syndrome (TCOF1) gene product is involved in ribosomal DNA gene transcription by interacting with upstream binding factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10709–10714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402492101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonzales B, et al. The Treacher Collins syndrome (TCOF1) gene product is involved in pre-rRNA methylation. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2035–2043. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dixon J, et al. Tcof1/Treacle is required for neural crest cell formation and proliferation deficiencies that cause craniofacial abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13403–13408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603730103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fumagalli S, et al. Absence of nucleolar disruption after impairment of 40S ribosome biogenesis reveals an rpL11-translation-dependent mechanism of p53 induction. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:501–508. doi: 10.1038/ncb1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel SR, et al. Differential roles of microtubule assembly and sliding in proplatelet formation by megakaryocytes. Blood. 2005;106:4076–4085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montaville P, et al. Nuclear translocation of the calcium-binding protein ALG-2 induced by the RNA-binding protein RBM22. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1335–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venables JP. Aberrant and alternative splicing in cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7647–7654. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deller T, et al. Synaptopodin-deficient mice lack a spine apparatus and show deficits in synaptic plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10494–10499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832384100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vician L, Silver AL, Farias-Eisner R, Herschman HR. NID67, a small putative membrane protein, is preferentially induced by NGF in PC12 pheochromocytoma cells. J Neurosci Res. 2001;64:108–120. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donehower LA, et al. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poustka A, Rackwitz HR, Frischauf AM, Hohn B, Lehrach H. Selective isolation of cosmid clones by homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:4129–4133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.13.4129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adams DJ, et al. Mutagenic insertion and chromosome engineering resource (MICER) Nat Genet. 2004;36:867–871. doi: 10.1038/ng1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1