Randomised controlled trial of integrated care to reduce disability from chronic low back pain in working and private life (original) (raw)

Abstract

Objective To evaluate the effectiveness of an integrated care programme, combining a patient directed and a workplace directed intervention, for patients with chronic low back pain.

Design Population based randomised controlled trial.

Setting Primary care (10 physiotherapy practices, one occupational health service, one occupational therapy practice) and secondary care (five hospitals).

Participants 134 adults aged 18-65 sick listed for at least 12 weeks owing to low back pain.

Intervention Patients were randomly assigned to usual care (n=68) or integrated care (n=66). Integrated care consisted of a workplace intervention based on participatory ergonomics, involving a supervisor, and a graded activity programme based on cognitive behavioural principles.

Main outcome measures The primary outcome was the duration of time off work (work disability) due to low back pain until full sustainable return to work. Secondary outcome measures were intensity of pain and functional status.

Results The median duration until sustainable return to work was 88 days in the integrated care group compared with 208 days in the usual care group (P=0.003). Integrated care was effective on return to work (hazard ratio 1.9, 95% confidence interval 1.2 to 2.8, P=0.004). After 12 months, patients in the integrated care group improved significantly more on functional status compared with patients in the usual care group (P=0.01). Improvement of pain between the groups did not differ significantly.

Conclusion The integrated care programme substantially reduced disability due to chronic low back pain in private and working life.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN28478651.

Introduction

Back pain is a common problem in Western societies. Although the prognosis for return to work is generally good, about 10-25% of patients with low back pain remain absent from work in the long term, risking social and financial deprivation and being responsible for 75% of the costs due to sickness leave and disability.1 2 Many of these patients have a long history of medicalisation, including various types of treatments, mostly aimed at alleviating the pain. These patients often end up receiving the usual treatment for pain, with poor results for pain reduction, and little attention is paid to reducing disability in private and working life.

Although current clinical guidelines for low back pain pay more attention to prevention of work disability,3 4 the usual treatment for pain is still not aimed at preventing disability.5 For this reason we developed an integrated care programme in the outpatient curative care setting by combining the prevention of work disability with a programme for the treatment of pain in patients with chronic low back pain. The biopsychosocial model of pain and disability provided the theoretical framework for this study.6 Within this framework, work disability due to low back pain is a result of human functioning by biomedical factors (red flags), psychological factors (yellow flags), workplace factors (blue flags), and healthcare and compensation system factors (black flags).6 7 8 Integrated care for patients with chronic low back pain consists of clinical interventions if needed (red flags), graded activity as a cognitive behavioural intervention (yellow flags), a workplace intervention encouraging the stakeholders to reduce barriers in the workplace (blue flags) and, occupational health care integrated into mainstream health care to reduce system barriers (black flags). The main aim of the treatment is to restore human functioning in private and working life and not to reduce the pain.9

Comparable occupational interventions have proved to be cost effective for the return to work of patients with subacute and non-specific low back pain in primary care,10 11 12 but the effectiveness of such an intervention has not been established yet for patients with chronic non-specific and specific low back pain in an outpatient curative care setting. We compared the effectiveness of integrated care with usual care on return to work after 12 months in patients in such a setting who were sick listed because of chronic low back pain.

Methods

The population in this randomised controlled trial comprised adults aged 18-65 with low back pain who had visited an outpatient clinic (mainly orthopaedics and neurology, but also rheumatology and neurosurgery) in one of the participating hospitals, had had low back pain for more than 12 weeks, were in paid work (paid employment or self employed) for at least eight hours a week, and were absent or partially absent from work. We excluded patients who had been absent from work for more than two years; had worked temporarily for an employment agency without detachment; had specific low back pain due to infection, tumour, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, fracture, or inflammatory process; had undergone lumbar spine surgery in the past six weeks or had to undergo surgery or invasive examinations within three months; had a serious psychiatric or cardiovascular illness; were pregnant; or were engaged in a lawsuit against their employer.

Patients with low back pain who had visited one of the participating hospitals received a letter from their medical specialist within one week of their visit informing them about the trial. A prepaid envelope was included for them to indicate their interest and check their eligibility for the study. A research assistant contacted potential participants by telephone. Those who met the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate were asked to give written informed consent. A detailed description of the design of this trial can be found elsewhere.13

Interventions

Usual care

Patients allocated to the usual care group received the usual treatment from their medical specialist, occupational physician, general practitioner, and/or allied health professionals.

Integrated care

The overall aim of the integrated care was to restore occupational functioning and achieve lasting return to work for patients in their own job or similar work, and not to reduce pain. The integrated care was coordinated by a clinical occupational physician and consisted of a workplace intervention based on participatory ergonomics10 11 14 and a graded activity programme, which is a time contingent programme based on cognitive behavioural principles.15 16 17

The integrated care was provided by a team consisting of a clinical occupational physician, a medical specialist, an occupational therapist, and a physiotherapist. The clinical occupational physician, who was responsible for the planning and the coordination of the care and for communication with the other healthcare professionals in the team, set a proposed date for full return to work in mutual agreement with the patient and the patient’s occupational physician. Communication between the team members consisted of telephone calls, letters, coded email, and a conference call every three weeks to discuss the progress of the patient regarding return to work. The box gives an overview of the integrated care protocol (see web extra on bmj.com for more details).

Overview of integrated care protocol

Integrated care management by clinical occupational physician

- _Aim—_To plan and coordinate care and communicate with other involved healthcare professionals

- _Period—_From week 1 to full sustainable return to work, or week 12

- _Content—_Formulate treatment plan (week 1), monitor treatment plan (week 6), and, when necessary, communicate with other healthcare professionals

Workplace intervention

- _Aim—_To achieve consensus of all stakeholders about adjustments to the workplace to facilitate return to work

- _Period—_From week 3 to week 12

- _Content—_Observation of patient’s workplace; obstacles on return to work ranked independently by supervisor and patient; patient, supervisor, and occupational therapist brainstorm and discuss possible solutions for obstacles until reaching consensus

Graded activity

- _Aim—_To restore patient’s occupational function and supervise return to work

- _Period—_From week 2 to full sustainable return to work, or after receipt of 26 sessions of graded activity (within maximum of 12 weeks)

- _Content—_Baseline (consisting of three sessions) to test patient’s functional capacity; individually graded exercise programme, teaching patients that, despite pain, moving is safe while increasing activity level

Outcome measures

Questionnaires were administered to the patients at baseline and after 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. Patient reported data on sick leave were collected every month by means of a diary and after 12 months from the database of the occupational health services.

The primary outcome was return to work, defined as duration of sick leave due to low back pain in calendar days from the day of randomisation until full return to work in own or other work with equal earnings for at least four weeks without recurrence, partial or full. We censored patients in case of losses to follow-up. For the entire follow-up period we calculated the total duration of sick leave due to low back pain (including recurrences of absenteeism from work caused by low back pain). Secondary outcomes were pain intensity, scored on a visual analogue scale,18 and functional status, assessed with the Roland disability questionnaire.19 Prognostic factors for the duration of sick leave (for adjustment in case of dissimilarities between the treatment groups) were potential work related psychosocial factors, measured with the job content questionnaire,20 and data on workload, measured with the Dutch musculoskeletal questionnaire.21

Sample size

We assumed a hazard ratio of 2.0 to indicate a relevant difference between the integrated care group and the usual care group. This value was based on hazard ratios reported in comparable studies in primary care.11 22 Another assumption, based on a similar cohort, was that 40% of patients with chronic low back pain would not return to work during the follow-up period (12 months after randomisation).23 We also expected a dropout rate of 10%. To obtain a complete dataset for 115 patients, we included 130 patients sick listed as a result of chronic low back pain (hazard ratio 2.0, with a power of 80% and a significance level of 5%).24

Randomisation

The patients were assigned to either integrated care or usual care after the baseline data had been collected. We applied prestratification for two important prognostic factors: duration of sick leave (<3 months or >3 months) and characteristics of the job (mainly physically demanding or mentally demanding).25 This led to a total of four strata. For every stratum, an independent statistician carried out block randomisation of four allocations, using a computer generated random sequence table. A research assistant prepared opaque, sequentially numbered and sealed coded envelopes for each stratum, containing a referral for either the integrated care group or the usual care group.

Blinding

It was not possible to blind the patients for treatment allocation. The care providers were also not blinded, but they were not involved in measuring the outcomes. However, since all the questionnaires were posted to the patients, it was not likely that the researcher and care providers would influence how the patients completed the questionnaires. In addition, all patients received a code according to which a research assistant entered all data in the computer. This ensured blinded analysis of the data by the researcher.

Statistical analyses

To assess the success of the randomisation we used descriptive statistics to compare the baseline measurements of the groups.

The primary independent variable in the analyses was the treatment to which the patient was allocated, and the primary dependent variable was the duration of absence from work in days until full sustainable return to work in own or similar work. We used Kaplan-Meier analysis (including the log rank test) to describe the univariate association between group allocation and the duration of absence from work until the first continuous period of full sustainable return to work. To estimate hazard ratios for return to work and the corresponding 95% confidence interval we used the Cox proportional hazard model. An assumption of this model is that the hazard ratio should remain constant over time. We checked this assumption.

We used the Mann-Whitney U test to compare the total number of days of sick leave due to low back pain (including recurrences) during the 12 months of follow-up between the groups. Longitudinal mixed models were applied to assess the differences between the two groups in improvement on all secondary outcome measures. In the analyses we adjusted for type of hospital and strata. All analyses were done according to the intention to treat principle. To assess whether protocol deviations had caused bias, we compared the results of the intention to treat analyses with those of the per protocol analyses. P values were two tailed. We considered a P value of 0.05 to be significant. The data were analysed with SPSS statistical software, version 15.0.

Results

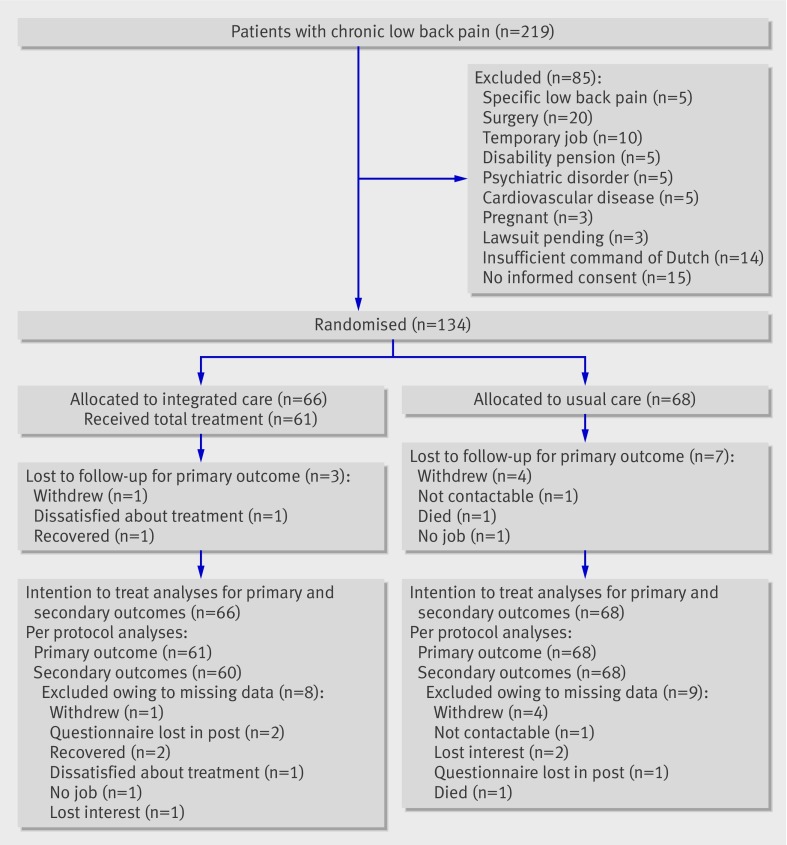

Between November 2005 and April 2007, 219 patients who had visited a medical specialist because of low back pain were eligible for participation. Overall, 85 patients were excluded and the remaining 134 were randomised: 68 to usual care and 66 to integrated care. Figure 1 shows the flow of patients through the study.

Fig 1 Patient flow through study

Loss to follow-up

Data on sick leave were complete for all patients at baseline, and for 93% of the patients during the 12 months of follow-up. Follow-up data on secondary outcomes after 12 months were incomplete for 17 patients (13%).

Non-compliance

One patient in the integrated care group and four in the usual care group withdrew from the study immediately after randomisation. Five patients did not participate in the integrated care intervention for various reasons: no job (n=1), quit job (n=1), no approval from employer (n=1), recovered (n=1), and withdrew (n=1). Twelve patients received only two elements of the integrated care (clinical occupational management and graded activity or workplace intervention). The reasons for this were no cooperation from employer (n=2) or patient (n=1), company bankrupt (n=1), adaptations already carried out (n=1), full return to work (n=1), continued with therapy from own therapist (n=4), distance too far (n=1), and symptoms other than low back pain (n=1).

Patient characteristics

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the outcome measures and the prognostic factors for the two groups. Median values (interquartile ranges) were calculated if data were skewed. Differences in baseline characteristics between the groups were non-significant.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and prognostic factors of outcome measures. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Variables | Integrated care (n=66) | Usual care (n=68) |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 37 (56) | 41 (60) |

| Women | 29 (44) | 27 (40) |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 45.5 (8.9) | 46.8 (9.2) |

| Level of education*: | ||

| Low | 14 (21) | 23 (34) |

| Intermediate | 34 (52) | 32 (47) |

| High | 18 (27) | 13 (19) |

| Mean (SD) job content questionnaire†: | ||

| Job control | 74.3 (10.3) | 72.5 (10.5) |

| Job demands | 33.2 (4.7) | 33.0 (4.4) |

| Social support | 23.5 (4.2) | 23.3 (3.6) |

| Demands of work: | ||

| Physical | 42 (64) | 42 (62) |

| Mental | 24 (36) | 26 (38) |

| Absence from work: | ||

| Partial | 34 (52) | 36 (53) |

| Full | 32 (49) | 32 (47) |

| Mean (SD) patients’ expectation of return to work (score 1-5)‡ | 2.9 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.2) |

| Prognostic factors: | ||

| Median (interquartile range) days off work before inclusion | 142 (54-173) | 163 (64-240) |

| Mean (SD) functional status (score 0-23)§ | 14.7 (5.0) | 15.0 (3.6) |

| Mean (SD) pain intensity (score 0-10)¶ | 5.7 (2.2) | 6.3 (2.1) |

Interventions

Usual care

Healthcare use of all the patients was monitored during the 12 months of follow-up (table 2). In most cases usual care consisted of treatment by a physiotherapist (n=42, 1473 consultations) or manual therapist (n=20, 367). Only a few patients visited their occupational physician (n=16, 38) or general practitioner (n=10, 47). Compared with integrated care, patients in the usual care group received more diagnostic tests and had more consultations for manual therapy, Cesar therapy, medical specialist, and psychological care. Analgesics were also used more often in the usual care group than integrated care group.

Table 3.

Mean (standard error) improvements in functional status and pain after 3, 6, and 12 months of follow-up, by intention to treat analysis

| Outcome | Mean (SE) improvement | Between group difference* (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated care | Usual care | |||

| Functional status†: | ||||

| 3 months (n=121) | 3.76 (0.86) | 3. 82 (0.85) | 0.11 (−2.4 to 2.6) | 0.93 |

| 6 months (n=118) | 4.81 (0.89) | 4.97 (0.88) | 0.06 (−2.3 to 2.5) | 0.96 |

| 12 months (n=121) | 7.16 (0.71) | 4.43 (0.72) | −2.86 (−4.9 to −0.9) | 0.01 |

| Pain‡: | ||||

| 3 months (n=123) | 1.11 (0.39) | 1.59 (0.38) | 0.99 (−1.3 to 2.1) | 0.08 |

| 6 months (n=123) | 1.26 (0.40) | 2.26 (0.40) | 0.49 (−0.6 to 1.6) | 0.37 |

| 12 months (n=121) | 1.64 (0.35) | 1.85 (0.36) | 0.21 (−0.8 to 1.2) | 0.67 |

Table 2.

Healthcare utilisation of study population during 12 months’ follow-up. Values are number of patients (number of consultations) unless stated otherwise

| Variables | Integrated care | Usual care |

|---|---|---|

| Primary care: | ||

| Occupational physician | 10 (47) | 16 (38) |

| General practitioner | 10 (24) | 11 (43) |

| Physiotherapist | 23 (508) | 42 (1473) |

| Graded activity therapist | 55 (980) | 0 |

| Manual therapist | 6 (80) | 20 (367) |

| Cesar therapist | 3 (22) | 5 (156) |

| Other physiotherapist | 2 (14) | 5 (23) |

| Psychologist | 2 (16) | 5 (59) |

| Alternative therapist | 12 (147) | 16 (190) |

| Secondary care: | ||

| Medical specialist | 13 (59) | 29 (117) |

| Diagnostic tests | 21 (156) | 44 (211) |

| Inpatient visit or surgery (days) | 3 (10) | 8 (30) |

| Drugs for back pain | 27 (76) | 40 (119) |

Integrated care

The average duration of integrated care (maximum three months) from randomisation was 67 days (SD 32 days). The median frequency of consultations with members of the multidisciplinary team from randomisation until sustainable return to work was 2.2 with the clinical occupational physician, 2.4 with the occupational therapist for the workplace intervention, and 6.5 individual sessions and 11.6 groups sessions with the physiotherapist during the graded activity protocol. No adverse events or side effects were reported.

Additional treatment in this group applied by caregivers other than the multidisciplinary team during the 12 months of follow-up consisted mostly of physiotherapy (n=23, 508 consultations). Patients had also visited their occupational physician (n=10, 47) and general practitioner (n=10, 24) and had used a diversity of alternative care (n=12, 147; table 2).

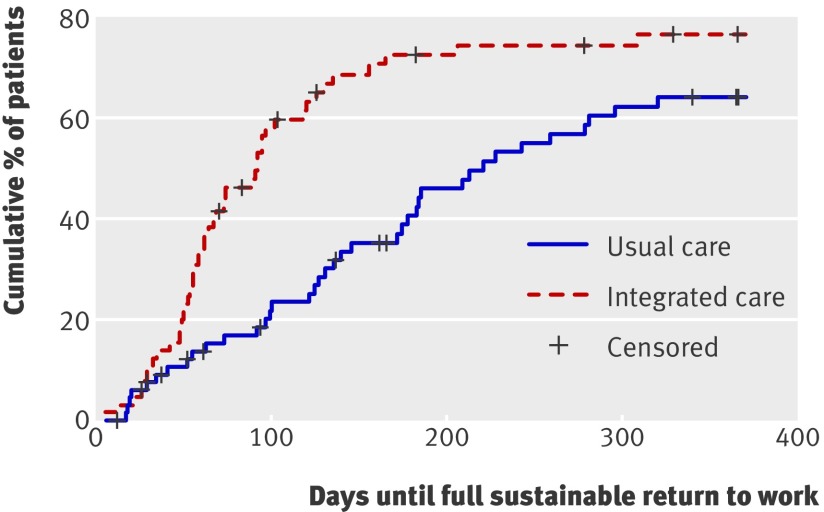

Primary outcome measure

The median duration of the first continuous period of sick leave after randomisation was 88 days (interquartile range 52-164 days) in the integrated care group and 208 (99-366) days in the usual care group (log rank test; P=0.003). Figure 2 presents the Kaplan-Meier curves for the two groups. The difference between these curves was significant (log rank test; P=0.004). The hazard ratio was 1.90 (95% confidence interval 1.18 to 2.76, P=0.004). The per protocol analysis results did not differ (hazard ratio 1.83, 1.24 to 2.93, P=0.007). During the 12 months of follow-up the median number of days of sick leave (including recurrences) in the integrated care group was 82 (interquartile range 51 to 164 days) compared with 175 (91 to 365) in the usual care group. This difference was significant (Mann-Whitney U test; P=0.003).

Fig 2 Kaplan-Meier survival curves of absence from regular or similar work for integrated care group and usual care group

Secondary outcome measures

Table 3[t3] presents the mean improvements in functional status and pain intensity from baseline to 12 month follow-up. The effects of integrated care compared with usual care, adjusted for stratum and type of hospital, were obtained from the longitudinal mixed model. Functional status and pain improved over time in both groups. No statistically significant differences in pain improvement were found between the two groups. The differences in functional status between the groups at 12 months were significant (P=0.01) and in favour of the integrated care group.

Discussion

Integrated care, directed at patients with chronic low back pain as well as their workplace, had a beneficial effect on disability. The median duration from randomisation until sustainable return to work was 88 days in the integrated care group compared with 208 days in the usual care group. Functional status after 12 months differed significantly between the groups and in favour of the integrated care group (P=0.01). Severity of pain did not differ significantly between the groups.

Limitations and strengths of the study

Firstly, we cannot exclude a placebo or Hawthorne effect as it was not possible to blind the patients or therapists owing to the nature of the integrated care. Secondly, our primary outcome might be prone to information bias because sick leave was self reported by the patients. These data were, however, checked with the data on sick leave obtained from the database of the occupational health services. Finally, the study design was not suitable for assessing the effectiveness of the individual components of the integrated care intervention (integrated care management, workplace intervention, graded activity). To explore which components had the most effect, future research could use a factorial design. In addition, qualitative research, focusing on the experience of the healthcare professionals and patients, could give more insight into the effective components of the intervention.

The strength of this study is the unique system approach, in which a patient directed intervention and a workplace directed intervention were combined. Moreover, this randomised controlled trial is of high quality, owing to high compliance (>92%) with the integrated care intervention and low loss to follow-up (<13%).

Comparison with other studies

Several earlier randomised controlled trials evaluated a similar intervention in patients with subacute low back pain and at an early stage of sick leave.11 22 Most of these studies showed that interventions with a workplace component are effective on work related outcomes at an early stage of back pain. The effectiveness of graded activity as a cognitive behavioural intervention at an early stage of sick leave was, however, conflicting.12 16 22 26 27 This study showed that in an advanced phase of work disability (>20 weeks of sick leave) due to chronic low back pain, integrated care (cognitive behavioural combined with a workplace intervention) is effective on disability outcomes in both working and private life.

The results of the secondary outcomes in our study are in line with those of a systematic review.28 The researchers of that review reported strong evidence that intensive multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation in patients with chronic low back pain improves function, and there is moderate evidence that it reduces pain.28 The lack of effectiveness on pain confirms our opinion on the validity of the work disability paradigm: chronic low back pain is not only a clinical problem but also a psychosocial and work related problem. This explains the finding of several earlier studies that resumption of work activities has no beneficial or adverse effect on pain intensity9 28 and that pain relief is not necessary to resume work.9 29

Policy implications

It is known that the longer the absence from work the greater the chances of permanent disability. With the current systems approach, in which the patient and the workplace both had a central role, patients with chronic low back pain and a history of long sick leave (>20 weeks) returned to their work earlier (median of 120 days during 12 months’ follow-up) than patients who received usual pain treatment with no involvement of the workplace. This integrated pain management approach is a promising way in which to reduce work disability and the burden of disease for patients with chronic low back pain without any undesirable significant or clinically relevant adverse effects on clinical outcomes. Implementation should not be difficult because in our study the costs of both interventions (graded activity programme and workplace intervention) were covered by the patient’s health insurance.

The findings of our study indicate that it is important to take all elements of the biopsychosocial model into account when treating a patient who resumes work after an absence caused by chronic low back pain. This means that, besides cognitive behavioural treatment for patients sick listed in the long term as a result of chronic low back pain, a visit to the workplace and adaptations at work are essential for return to work. Occupational physicians are best equipped to manage these patients,30 so doctors should refer these patients to occupational physicians for targeted work related interventions.31 This study and recent other studies show that sick leave as a result of work related physical problems can be managed effectively.32

Conclusions

Chronic low back pain is not just a clinical problem but also a psychosocial and work related problem. Integrated graded activity with a workplace intervention reduced disability in both working and private life because of chronic low back pain by a median of 120 days during a follow-up period of 12 months. This applies to a selected group of patients with chronic low back pain, all of whom were judged appropriate for this kind of psychosocial treatment. The lack of effectiveness on pain confirms the validity of the work disability paradigm. This promising systems approach, directed to both the patient and the work environment, could have a great impact on the individual burden of low back pain.

What is already known on this topic

- As well as a clinical problem, chronic low back pain is a psychosocial and work related problem

- Clinical guidelines for low back pain focus on prevention of work disability, but usual treatment for pain is still not aimed at preventing disability

- Although interventions including a workplace component have been shown to be effective on return to work for patients sick listed due to subacute back pain, no studies exist on their effects on chronic back pain

What this study adds

- An integrated care approach substantially reduced disability in private and working life for a small but relevant group of patients with chronic low back pain

- This study showed that pain and (work) disability are different treatment goals

- Earlier resumption of work activities had no beneficial or adverse effect on pain intensity

We thank the clinical occupational physicians, occupational therapists, and physiotherapists for administering the intervention, the occupational physicians for providing data, the medical specialists for supporting this research project, and Sjennie Daelmans for her help with recruiting patients and data entry.

Contributors: LCL and JRA were responsible for the general coordination of the study, implemented the integrated care programme. LCL collected the data. WvM is guarantor. All authors designed the study, helped write the manuscript, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by VU University Medical Center, TNO Work & Employment, Dutch Health Insurance Executive Council, Stichting Instituut GAK, and the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. This research was carried out within the framework of the Work Disability Prevention Canadian Institutes of Health Research strategic training programme, which supported LCL (grant FRN: 53909). The authors were independent of the funders and the funders had no role in the project.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the medical ethics committees of the participating hospitals (VU University Medical Centre, Slotervaart Hospital, Amstelland Hospital, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, based in Amsterdam, and Spaarne Hospital based in Hoofddorp).

Data sharing: Details of the integrated care protocol are in the web extra.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;340:c1035

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Integrated care protocol

References

- 1.Cats-Baril WL, Frymoyer JW. The economics of spinal disorders. In: Frymoyer JW, ed. The adult spine: principles of practice. Raven Press, 1991.

- 2.Van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM. A cost-of-illness study of back pain in the Netherlands. Pain 1995;62:233-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Low back pain. Early management for persistent non-specific low back pain. 2009. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG88NICEGuideline.pdf.

- 4.Verbeek JH, Anema JR, Everaert CPJ, Foppen GM, Heymans M, Hloblil H, et al. NVAB-Richtlijn Handelen van de bedrijfsarts bij werknemers met Lage-Rugklachten. 2006. http://nvab.artsennet.nl/Nieuws/Rugklachten-2.htm.

- 5.Engers AJ, Wensing M, van Tulder MW, Timmermans A, Oostendorp RA, Koes BW, et al. Implementation of the Dutch low back pain guideline for general practitioners: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Spine 2005;30:559-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waddell G, Burton AK, Aylward M. A biopsychosocial model of sickness and disability. AMA Guides Newsletter. May/June ed. American Medical Association, 2008:1-13.

- 7.Main CJ, Williams AC. Musculoskeletal pain. BMJ 2002;325:534-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. WHO, 2001. www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/.

- 9.Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain 2000;85:317-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anema JR, Steenstra IA, Urlings IJ, Bongers PM, de Vroome EM, van Mechelen W. Participatory ergonomics as a return-to-work intervention: a future challenge? Am J Ind Med 2003;44:273-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loisel P, Abenhaim L, Durand P, Esdaile JM, Suissa S, Gosselin L, et al. A population-based, randomized clinical trial on back pain management. Spine 1997;22:2911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staal JB, Hlobil H, Twisk JW, Smid T, Koke AJ, van Mechelen W. Graded activity for low back pain in occupational health care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambeek LC, Anema JR, van Royen BJ, Buijs PC, Wuisman PI, van Tulder MW, et al. Multidisciplinary outpatient care program for patients with chronic low back pain: design of a randomized controlled trial and cost-effectiveness study [ISRCTN28478651]. BMC Public Health 2007;7:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Jong AM, Vink P. Participatory ergonomics applied in installation work. Appl Ergon 2002;33:439-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fordyce WE. Behavioral methods for chronic pain and illness. Mosby, 1976.

- 16.Lindstrom I, Ohlund C, Nachemson AL. Physical performance, pain, pain behavior and subjective disability in patients with subacute low back pain. Scand J Rehabil Med 1995;27:153-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindstrom I, Ohlund C, Eek C, Wallin L, Peterson LE, Fordyce WE, et al. The effect of graded activity on patients with subacute low back pain: a randomized prospective clinical study with an operant-conditioning behavioral approach. Phys Ther 1992;72:279-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlsson AM. Assessment of chronic pain. I: aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale. Pain 1983;16:87-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine 1983;8:141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The job content questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol 1998;3:322-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hildebrandt VH, Bongers PM, van Dijk JH, Kemper HCG, Dul J. Dutch musculoskeletal questionnaire: description and basic qualities. Ergonomics 2001;44:1038-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anema JR, Steenstra IA, Bongers PM, de Vet HC, Knol DL, Loisel P, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for subacute low back pain: graded activity or workplace intervention or both? A randomized controlled trial. Spine 2007;32:291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anema JR, Cuelenaere B, van der Beek AJ, Knol DL, de Vet HC, Van MW. The effectiveness of ergonomic interventions on return-to-work after low back pain; a prospective two year cohort study in six countries on low back pain patients sicklisted for 3-4 months. Occup Environ Med 2004;61:289-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collet D. Modelling survival data in medical research. Chapman & Hall, 1994.

- 25.De Zwart BC, Broersen JP, van der Beek AJ, Frings-Dresen MH, van Dijk FJ. Occupational classification according to work demands: an evaluation study. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 1997;10:283-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steenstra IA, Anema JR, Bongers PM, De Vet HCW, Knol DL, van Mechelen W. The effectiveness of graded activity for low back pain in occupational healthcare. Occup Environ Med 2006;63:718-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heymans MW, de Vet HC, Bongers PM, Koes BW, van Mechelen W. Back schools in occupational health care: design of a randomized controlled trial and cost-effectiveness study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004;27:457-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guzman J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Irvin E, Bombardier C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ 2001;322:1511-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crombez G, Vlaeyen JW, Heuts PH, Lysens R. Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain 1999;80:329-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henderson M, Glozier N, Holland EK. Long term sickness absence. BMJ 2005;330:802-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anema JR, van der Beek AJ. Medically certified sickness absence. BMJ 2008;337:a1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Oostrom SH, Driessen MT, de Vet HC, Franche RL, Schonstein E, Loisel P, et al. Workplace interventions for preventing work disability. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD006955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Integrated care protocol