Gene Variants of Brain Dopamine Pathways and Smoking-Induced Dopamine Release in the Ventral Caudate/Nucleus Accumbens (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 May 20.

Published in final edited form as: Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Jul;63(7):808–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.808

Abstract

Context

Preclinical studies demonstrate that nicotine administration leads to dopamine release in the ventral striatum. However, human studies reveal considerable interindividual variability in the extent of smoking-induced dopamine release.

Objective

To determine whether common gene variants of the brain dopamine pathway explain this observed phenotypic variability in humans.

Design

Blood samples were drawn to determine gene variants of dopamine system components, and positron emission tomography scanning with the radiotracer raclopride labeled with radioactive carbon (11C) was performed to measure smoking-induced dopamine release.

Setting

Academic brain imaging center.

Participants

Forty-five tobacco-dependent smokers.

Interventions

Subjects either smoked a cigarette (n=35) or did not smoke (n=10) during positron emission tomography scanning.

Main Outcome Measures

Gene variants of dopamine system components (the dopamine transporter variable nucleotide tandem repeat, D2 receptor Taq A1/A2, D4 receptor variable nucleotide tandem repeat, and catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met polymorphisms) and change in [11C]raclopride binding potential in the ventral caudate/nucleus accumbens on positron emission tomography scans.

Results

For subjects who smoked during scanning, those with at least one 9 allele of the dopamine transporter variable nucleotide tandem repeat, fewer than 7 repeats of the D4 variable nucleotide tandem repeat, and the Val/Val catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype had greater decreases in binding potential (an indirect measure of dopamine release) with smoking than those with the alternate genotypes. An overall decrease in ventral caudate/nucleus accumbens binding potential in those who smoked compared with those who did not smoke was also found but was smaller in magnitude than previously reported.

Conclusions

Smokers with genes associated with low resting dopamine tone have greater smoking-induced (phasic) dopamine release than those with alternate genotypes. These findings suggest that dopamine system genotype variabilities explain a significant proportion of the interindividual variability in smoking-induced dopamine release and indicate that smoking-induced dopamine release has a genetic predisposition.

ACOMMON PATHWAY FOR the reinforcing properties of most, if not all, addictive drugs is the mesolimbic brain dopamine (DA) system.1-4 In laboratory animal studies, the reinforcing property of nicotine has repeatedly been linked to DA release in the nucleus accumbens (NAc).5-14 Recent small studies of human smokers have used raclopride labeled with radioactive carbon (11C) with positron emission tomography (PET) to assess change in DA concentration in response to smoking. These studies have generally supported the association between smoking and DA release, especially the relief from craving15 and hedonic responses16 that smokers experience when smoking. However, considerable unexplained interindividual variability in smoking-induced DA release was reported in these studies.

The high heritability of nicotine dependence17 and differences in individual sensitivity to the reinforcing properties of smoking implicate the influence of genetic differences on positive reinforcement from smoking.18 In the primary analysis of the present study, we sought to determine if known genetic variability in components of the brain DA pathway would help explain observed phenotypic variability in smoking-induced DA release found among human smokers. Although others have associated genetic variability with overall D2 dopamine receptor densities,19-22 we are aware of no prior studies that examined the link between DA genetic variability and DA release in humans. For this initial study, we restricted our examination to those well-characterized gene variants with reported functional effects while recognizing that many other genes could contribute to variation in smoking-induced DA release.

Within the mesolimbic DA pathway, nicotine stimulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on neurons of the ventral tegmental area that project to the NAc and release DA, resulting in positive reinforcement.9,23,24 Genotypic (and associated phenotypic) variation of any of the components of this pathway could affect the degree of smoking-induced DA release in individual smokers. From a large number of potential genes of interest, specific gene variants were chosen for analysis from well-studied parts of brain DA pathways, namely (1) the DA transporter (DAT),25 (2) the D2 dopamine receptor (DRD2) (a presynaptic and postsynaptic receptor26 that is activated indirectly by even low concentrations of nicotine27), (3) the D4 dopamine receptor (DRD4) (a receptor that is expressed in low levels in the basal ganglia but may modulate excitatory neurotransmission28), and (4) the enzyme catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT).29

Four genetic variants were chosen from these DA system components based on substantial evidence of functional consequences of these variants, possible association with risk for nicotine dependence, and/or influence on brain DA system regulation. For DAT, the variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR) polymorphism of the 3′ untranslated region (SLC6A3)30 was selected because of reports linking the 10-repeat allele with risk for conditions associated with smoking behavior, namely attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,31 hyperactivity,32 and reward dependence.33 Studies using single photon emission computed tomography have demonstrated associations between the 10-repeat allele and increased,34 decreased,35,36 or unaltered37-39 DAT density (compared to alternate genotypes) with the larger (sample-size) studies demonstrating decreased or unaltered DAT density. If subjects with the 10-repeat allele indeed have decreased DAT density, we hypothesize that such subjects would have higher tonic levels of intrasynaptic DA and less phasic DA release in response to smoking.

For DRD2, A1/A2 allelic variation of Taq1 was selected because the A1 allele is associated with low DRD2 density,19,20,40-42 increased likelihood of smoking behavior overall,43 progression to higher levels of smoking by adolescents,44 less positive responsiveness to bupropion hydrochloride45,46 (a medication with dopaminergic properties) or other treatments47 in smokers attempting to quit, and greater feelings of food reward following smoking cessation.48 Because the A1 allele is associated with decreased DRD2 density and function, and the DRD2 receptor is associated with inhibition of DA release,49,50 we hypothesized that subjects with the A1 allele would have greater DA release (due to less inhibition) than those with the alternate genotype.

For DRD4, variation in the 48–base pair (bp) VNTR in exon 3 was chosen based on the association of the 7-repeat allele with a reduced ability of DA to inhibit cAMP formation,51 reduced effectiveness of DA-releasing medications,52 and links with smoking behavior.53 Because DRD4 stimulation results in sensitization to a DA-releasing drug54 and blockade in the NAc results in diminished DA release,55 we hypothesized that subjects with the 7-repeat allele of DRD4 (having less DRD4 function) would have less smoking-induced DA release than subjects with the alternate genotype.

For COMT, we chose the 1947A>G (Val158Met) polymorphism because the Val substitution is associated with 3-fold to 4-fold higher enzyme activity56 as well as substance abuse57 and the personality traits novelty seeking and reward dependence.58 Additionally, a recent review of the functional effects of the COMT polymorphism59 concluded that the Met allele (low enzyme activity) results in increased levels of tonic DA and reciprocal reductions in phasic DA released in subcortical regions. Based on these reports, we hypothesized that subjects with the Met allele would have less smoking-induced DA release than subjects with the alternate genotype.

The 4 gene variants were studied with the recognition that research linking genetic variants with smoking and/or the brain DA system is an evolving field, and only modest links exist in the scientific literature between genotype and smoking.60,61 Other genotypes (such as α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor,62 dopamine β hydroxylase,63 and 5-HTT60 functional polymorphisms) are certainly candidates for associations with smoking-12induced DA release; however, we felt that evidence for including these genotypes was not as strong as for the ones selected. We also recognize that some of the DA genotypes chosen here have had negative reports for associations with smoking,64-67 and some have had conflicting results regarding which allelic variants (if any) are associated with smoking.68-71

In addition to the primary analysis of this study (genotype/PET associations), we also tested for evidence of smoking-induced DA release as we have in the past15 with the present study having a larger sample of smokers and subjects being scanned on a newer PET scanner with improved sensitivity.

METHODS

SUBJECTS AND STUDY OVERVIEW

Forty-five otherwise healthy adult (21-65 years old) cigarette smokers (15-40 cigarettes per day) were interviewed with standardized questions; filled out rating scales related to cigarette usage, mood, and personality; had blood drawn for genetic testing; underwent [11C]raclopride PET scanning and either smoked a cigarette (n=35) or did not smoke (n=10) during the scan; and underwent structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (to aid in interpretation of the PET scans). Subjects completed genetic testing, PET scanning, and administration of rating scales on a single afternoon and underwent structural MRI on a separate morning within 1 week of PET scanning. The present study represents a new group of subjects that have no overlap with those in our previous report.15

Subjects were screened initially during a telephone interview in which medical, psychiatric, and substance abuse histories were obtained without personal identifiers. All subjects who qualified were assessed in person using screening questions from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID).72 Inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as in our previous report with the central inclusion criterion being DSM-IV nicotine dependence and subjects being excluded for any history of an Axis I psychiatric or substance abuse/dependence diagnosis other than nicotine dependence. After a complete description of the study was provided to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained using forms approved by the local institutional review board.

GENETIC TESTING

Blood samples were collected and genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood with the Qiagen Kit using the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif).

The DAT1 (SLC6A3) 40-bp repeat polymorphism was genotyped as described elsewhere.48 The DRD2 TaqA1 polymorphism and the COMT Val108/158Met polymorphism were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction, restriction digest, and electrophoresis according to published methods.19,56 The DRD4 48 bp repeat polymorphism was genotyped as follows, based on a modification of published methods. Polymerase chain reaction amplification of 50 ng of genomic DNA was performed in 20 μL reactions containing 6pM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 8 nmol of forward and reverse primers, 0.2 μM Tris (8.4 pH), 1 μM potassium chloride, 30 pmol of magnesium, 1× Q solution, and 1 U of HotStar Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen). The primer sequences used were DRD4F, 5′-CTA CCC TGC CCG CTC ATG-3′; DRD4R, 5′-CCG GTG ATC TTG GCA CGC-3′. Using the MJ Research Tetrad thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif), DNA was denatured at 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 10 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 66°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 90 seconds and 25 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 90 seconds, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. Ten μL of polymerase chain reaction products were electrophoresed in 3.5% Nusieve Agarose (Cambrex, Baltimore, Md) in 1X TBE (Tris/borate/EDTA) buffer for approximately 4 hours at 70 V. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide, and alleles were determined by comparison with molecular weight standards and with control individuals with previously determined genotypes.

PET (AND MRI) SCANNING AND IMAGE ANALYSIS

Scanning sessions with PET and MRI followed the same protocol as in our previous report15 with the exception that scans for the current group were performed on a newer PET scanner (described later in this section). Positron emission tomography scanning consisted of a single [11C]raclopride bolus-plus-continuous-infusion PET session. Subjects were instructed to smoke per their usual habit on the morning of the PET session and to smoke a cigarette immediately prior to the test session, which began at noon. Between noon and 1:45 pm, subjects were interviewed and they filled out rating scale questionnaires and other measures. The rating scales included screening questions from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV,72 the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence,73,74 the Urge to Smoke (UTS) scale,75 the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Index,76 and the Hamilton Depression77 and Anxiety78 rating scales. Exhaled carbon monoxide levels were measured prior to [11C]raclopride injection using a MicroSmokerlyzer (Bedfont Scientific Ltd, Kent, United Kingdom) to make a rough estimate of recent smoking level. In addition to these prescanning ratings, cigarette craving (UTS) and state anxiety (Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Index) levels were monitored at 3 other points during PET scanning. Only the UTS scores were analyzed with the PET data (as discussed later in this section) while other rating scales were administered to ensure low levels of psychiatric symptoms in the study sample.

At 1:45 pm, subjects had a 20-gauge intravenous catheter placed and were positioned on the PET scanner (for acquisition of planes parallel to the orbital-meatal line) at 2 pm. Scanning was initiated at 2:10 pm with a slow bolus injection of 185 MBq [11C]raclopride in 20 mL normal saline over a 60-second period followed by continuous infusion of the tracer (111 MBq/h) for the remainder of the testing session. This bolus-pluscontinuous-infusion method was performed as described in prior studies.79,80 Brain scans were acquired continuously for the next 50 minutes.

At 3 pm, subjects were taken off the scanner with the infusion still running and had a 10-minute break in an outdoor area adjacent to the PET scanning room. Thirty-five subjects smoked a regular cigarette (either their favorite brand or a standard study cigarette) during this period; the remaining subjects stood in the same outdoor area but did not smoke during scanning as a control condition (assignment to the smoking or no-smoking condition was random with a ratio of 4:1). The 3-hour period of abstinence prior to the break was chosen based on the finding that craving starts to peak at this time in nicotine-dependent smokers.81 A study investigator (A.L.B. or R.E.O.) monitored subjects continuously during the break. After the break, subjects were quickly repositioned (<1 minute) in the scanner using a preplaced mark on their forehead and a laser light from the scanner. Subjects were then scanned for 30 minutes longer.

Subjects were scanned on a GE Advance NXi scanner (General Electronic Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wis) with 35 slices in 3-dimensional mode. We prepared [11C]raclopride using an established procedure.82,83 Positron emission tomography scans were acquired as 10 prebreak and 6 postbreak 5-minute frames. Attenuation correction scanning was performed with the germanium rotating rod source built into the GE scanner for 5 minutes following the postbreak scan, and this attenuation correction was applied to both prebreak and postbreak scans.

An MRI scan of the brain was obtained with the following specifications: 3-dimensional Fourier-transform spoiled-gradient-recalled acquisition; repetition time, 30 ms; echo time, ms; 30° angle; 2 acquisitions; 256×192 view matrix. The acquired volume was reconstructed as 90 contiguous 1.5-mm-thick transaxial slices.

Coregistration of PET scans to MRI scans was performed using the automated image registration method84 within MEDx 3.3 (Sensor Systems Inc, Sterling, Va). The prebreak (0- to 50-minute) and postbreak (60- to 90-minute) scans were coregistered to the MRI separately. Individual 5-minute time frames were then coregistered to MRI scans using the transformation matrix parameters from the coregistration of the summed images.

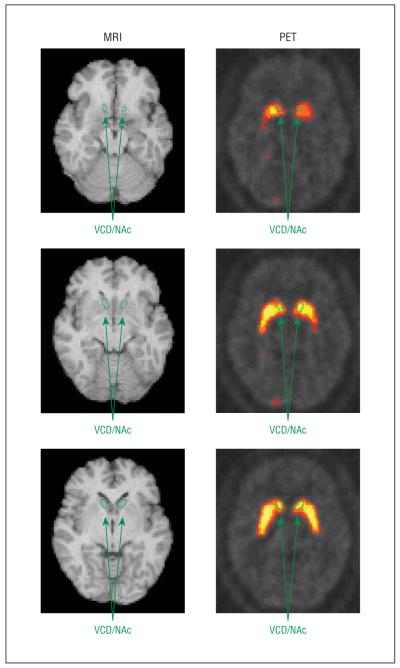

Regions of interest were drawn on MRI and transferred onto the coregistered PET scan frames. Region-of-interest placement on each frame was verified by visual inspection by the region drawers (D.S. and E.H.) and the principal investigator. For this study, the volume-of-interest (VOI) value used for statistical analysis was the volume-weighted mean of left and right ventral caudate (VCD) regions of interest (including the NAc) (Figure 1), consisting of 3 slices each, resulting in a single VOI value for each 5-minute frame of PET scanning. Volume-weighted means of left and right dorsal caudates and putamen were drawn as additional regions as in our prior report.15 The entire cerebellum was drawn as a reference region. Binding potential (BP) for the VCD/NAc (and other striatal regions) was calculated using the simplified reference tissue model85 with BP=B’max/Kd=CVCD/NAc/Ccerebellum−1, where C is radioligand concentration. Binding potential was determined for each 5-minutePET frame, and mean BP values were compared between the frames before (40-50 minutes) and after (60-90 minutes corrected for radiotracer physical decay) the break in scanning. These time frames are almost identical to those recommended and used as optimal for maximizing the signal-to-noise ratio in studies of the [11C]raclopride bolus-plus-continuousinfusion method.86,87 This method assumes 40 minutes for the bolus plus infusion to reach a near steady state.80,86,87 It also assumes that DA concentration will remain elevated throughout the 30-minute postsmoking scan as indicated by animal microdialysis5,88-90 and imaging91 studies of nicotine administration. A single primary ventral striatum VOI was used to avoid multiple comparison corrections, which would reduce the power of this analysis.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance image (MRI)/positron emission tomography (PET) coregistration, showing regions of interest drawn on MRI and transferred to a coregistered PET image with raclopride labeled with radioactive carbon (11C). VCD/NAc indicates ventral caudate/nucleus accumbens.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

General

Because of the possibility of type I statistical error in a large data set such as this one (which includes gene variant data for many genes, PET data for multiple regions, and rating scale and demographic data), we limited statistical tests to the fewest possible relevant variables based on prior research. For genetic variant data, 4 gene variants were studied, and each was used to divide the study group into 2 subgroups. The 4 genetic variants (described earlier in the article) and the subgroups based on these variants were the DAT VNTR (9/9 and 9/10 vs 10/10), DRD2 Taq1 (A1/A1 and A1/A2 vs A2/A2), DRD4 VNTR (less than 7 repeats vs 7 or more repeats), and COMT (Met/Met and Met/Val vs Val/Val) polymorphisms. For PET data, the only variable used was percentage change in BP for the average of left and right VCD/NAc VOIs from the 10-minute period before to the 30-minute period after the break. A single VOI BP value was felt to be sufficient based on our prior report that demonstrated nearly identical BP changes for the left and right VCD/NAc15 and similar changes across all striatal regions. Statistical tests described in the following sections were performed with SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS, Chicago, Ill).

Associations Between Genetic Variants and Smoking-Induced DA Release

For the primary analysis here, an overall univariate analysis of variance was performed for the 35 subjects who smoked during scanning with percentage change in VCD/NAc BP as the dependent variable and the 4 genetic variants as between-subject factors without interactions. Each genetic variant subgroup’s VCD/NAc BP percentage change was examined to assess which genetic variants had greater and lesser degrees of smoking-induced DA release. To further characterize results of this primary analysis, t tests (2-tailed) were performed comparing the subgroups of the genotypes found significant in the preceding analysis to determine if they differed significantly in levels of smoking (cigarettes per day), number of years smoking, or change in craving (UTS score) from before to after smoking.

Study of Smoking-Induced DA Release

In our previous study,15 an unexpectedly large percentage change in ventral striatal BP with smoking was found in a small sample of subjects who smoked during scanning (n=10). Here, we studied a larger group of subjects using a newer PET scanner and attempted to again test the hypothesis that smoking would result in greater reductions in VOI BP than a nonsmoking control. For this analysis, a t test (2-tailed) was performed for percentage change in VCD/NAc BP in the group that smoked (n=35) vs the control group that did not smoke (n=10). Correlation coefficients were also determined between percentage change in VCD/NAc BP and change in UTS (craving) score for the group that smoked to seek to again demonstrate an association between change in the indirect measure of DA release (change in VCD/NAc BP) and change in craving (UTS score).15

RESULTS

GENERAL SUBJECT CHARACTERISTICS

The study population consisted of adults (mean±SD age, 36.6±10.6 years), who smoked a mean±SD of 23.9±6.0 cigarettes per day, were mostly male (32 men, 13 women), and had been smoking for an average±SD of 17.9±10.2 years. Subjects had a mean±SD exhaled carbon monoxide of 19.0±10.9 parts per million after 1 to 2 hours of abstinence, were moderately nicotine dependent (Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence mean±SD score, 5.5±2.0), and had minimal depression (mean±SD total Hamilton Depression 17-item score, 1.8±1.9) or anxiety (mean±SD total Hamilton Anxiety score, 2.3±2.5). There were no significant differences between the groups that did and did not smoke during scanning in any of the preceding variables (t tests; range of P values, .20 to .88).

GENETIC VARIANTS AND SMOKING-INDUCED DA RELEASE

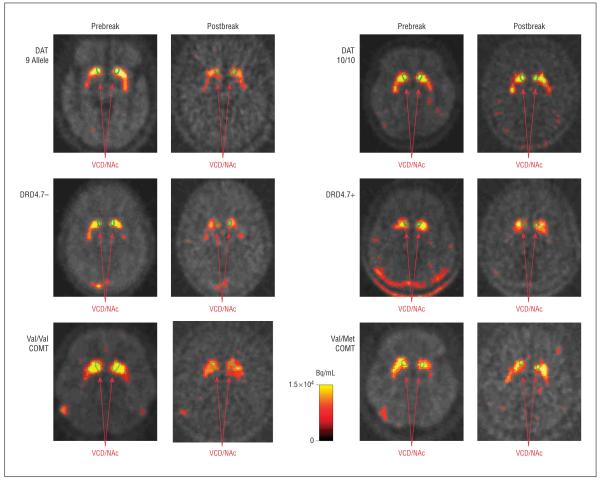

The overall analysis of variance revealed a significant effect of genotype on percentage change in VCD/NAc BP (F4,30=6.5, _P_=.001). In examining the main effects of the 4 genotypes, subgroups based on the DAT (F1,30=4.9, _P_=.03) and DRD4 (F1,30=4.4, _P_=.04) VNTRs and the COMT (F1,30=10.2, _P_=.003) polymorphism differed in VCD/NAc BP percentage change in subjects who smoked during scanning, indicating that these genotypes are linked with the magnitude of smoking-induced DA release. In examining percentage change in VCD/NAc BP (Table and Figure 2), subgroups with the 9/9 or 9/10 genotype of the DAT VNTR, those with fewer than 7 repeats of the DRD4 VNTR (DRD4.7–), and those with the Val/Val COMT genotype (rapid metabolizers) had greater changes in VCD/NAc BP than those with the alternate genotypes, indicating that these genotypes are linked with greater smoking-induced DA release. No differences between subgroups based on the Taq1 polymorphism were found (Table), and no significant differences between subgroups based on any of the 4 genotypes were found in baseline (prebreak) BP values (all P values >.25).

Table. Smoking-Induced Changes in Ventral Caudate/Nucleus Accumbens Raclopride Labeled With Radioactive Carbon (11C) Binding Potential for Subgroups of Smokers Based on Genotype.

| Genetic Variant | Change in VCD/NAc BPWith Smoking, Mean ± SD, % | Absolute VCD/NAc BP ChangeWith Smoking, Mean ± SD | F (ANOVA, df = 1,30) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAT | ||||

| 9 allele (n = 15) | −14.8 ± 14.7 | −0.37 ± 0.36 | 4.9 | .03 |

| 10/10 (n = 20) | −3.6 ± 11.0 | −0.09 ± 0.26 | ||

| DRD2 | ||||

| A1 allele (n = 14) | −6.6 ± 12.1 | −0.17 ± 0.31 | 0.3 | .86 |

| A2/A2 (n = 21) | −9.6 ± 14.9 | −0.23 ± 0.35 | ||

| DRD4 | ||||

| >7 (n = 24) | −11.3 ± 13.2 | −0.29 ± 0.33 | 4.4 | .04 |

| ≥7 (n = 11) | −2.0 ± 13.3 | −0.04 ± 0.27 | ||

| COMT | ||||

| Val/Val (n = 8) | −21.7 ± 15.5 | −0.48 ± 0.35 | 10.2 | .003 |

| Met allele (n = 27) | −4.5 ± 10.6 | −0.13 ± 0.28 |

Figure 2.

Sample images from positron emission tomography with raclopride labeled with radioactive carbon (11C) for genotypes found to differentiate subjects with high vs low dopamine (DA) release. The 2 left columns demonstrate decreases in [11C]raclopride binding (a marker for DA release) with smoking (postbreak scans are decay corrected) for subjects with the 9-allele repeat of the dopamine transporter (DAT) gene, less than 7 repeats (DRD4.7–) for the DRD4 genotype, or the Val/Val genotype of the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphism. The 2 right columns demonstrate little change in [11C]raclopride binding in subjects with the alternate genotypes. VCD/NAc indicates ventral caudate/nucleus accumbens.

In examining the effect of the polymorphisms on clinical variables, subjects who were DRD4.7– smoked significantly fewer cigarettes per day than those who were DRD4.7+ (22.0±4.1 vs 26.6±4.9 cigarettes per day, respectively; _t_=2.8, _P_=.01) (although the 2 subgroups did not have significantly different exhaled carbon monoxide levels at the time of scanning: 21.5±10.7 vs 19.5±11.9, t test, _P_=.60). Subjects who were DRD4.7– also had a greater reduction in mean UTS (craving) score from before to after smoking than DRD4.7+ subjects (−3.7±1.6 vs −2.5±2.2, respectively; _t_=2.0, _P_=.05). No significant differences were found between subgroups based on the DRD4 genotype for number of years smoking or in the subgroups based on the other polymorphisms for the 3 clinical variables. Controlling for smoking habits (number of cigarettes per day) did not change the central results of the study with an overall significant analysis of covariance (F5,29=4.0, _P_=.007) and 3 genotype main effects (DRD4, F1,29=7.9, _P_=.009; DAT, F1,29=5.8, _P_=.02; and COMT, F1,29=5.0, _P_=.03) still being found.

STUDY OF SMOKING-INDUCED DA RELEASE

Subjects in this study who smoked during the break in scanning (n=35) had a greater reduction in mean VCD/NAc BP than those who did not smoke (n = 10) (−8.4±13.8% vs +1.8±12.5%, _t_=2.1, _P_=.04), indicating that smoking during scanning results in greater VCD/NAc DA release than taking a break in scanning without smoking. Results were similar for the left (−8.0±14.8% vs +0.7±13.9%, t test, _P_=.11) and right (−8.9±14.5% vs +2.9±11.5%, t test, _P_=.02) VCD/NAc. The exploratory VOIs had slightly weaker group differences that did not reach significance (−8.7±12.6% vs −2.2±15.7%, _t_=1.4, P = .18, for the dorsal caudate and −7.9±11.0% vs −1.5±15.9%, t = 1.5, P = .15 for the dorsal putamen). Presmoking to postsmoking findings were larger than the frame-to-frame variability for the 2 prebreak (2.2%) and postbreak (1.8%) PET scans. Changes in cerebellar radioactivity from before to after the break were similar for the smoking and nonsmoking groups (−3.3±14.0% vs −2.3±8.8%, respectively, t test, _P_=.83).

There was a positive correlation between percentage change in VCD/NAc BP and change in UTS (craving) scores from before to after the break (_r_=0.33, _P_=.05), indicating that greater smoking-induced DA release was associated with greater alleviation of craving. Correlations between change in VOI BP and change in UTS scores for the exploratory VOIs were not significant (_r_=0.10, _P_=.55, for the dorsal caudate and _r_=0.15, _P_=.39, for the dorsal putamen).

COMMENT

In this study, known genetic variants of the DA system were associated with varying levels of smoking-induced DA release in the VCD/NAc of tobacco-dependent smokers. Specifically, smokers with the 9-repeat allele of the DAT 3′ VNTR, DRD4.7–, or the Val/Val genotype of the COMT polymorphism had more smoking-induced DA release (measured indirectly) than those with the 10/10 DAT, DRD4.7+, or the Met COMT genotypes. Also, subjects with the DRD4.7– genotype smoked fewer cigarettes per day and had a greater reduction in craving from before to after smoking than DRD4.7+ subjects. As noted earlier in the article, the 10/10 genotype of DAT is potentially linked with decreased DAT density35,36 while the DRD4.7+ VNTR has been associated with reduced ability of DA to inhibit cAMP formation,51 reduced effectiveness of DA releasing medications,52 and smoking behavior53 and the Met allele of COMT is associated with slow DA catabolism,56 thereby indicating potential mechanisms for these genotypes to alter smoking-induced DA release.

Results of this study might be best understood from the perspective of the tonic-phasic model of DA function, with a recent study demonstrating that nicotine amplifies DA release during phasic activity in the striatum.92 The strongest associations observed with our paradigm are consistent with genetic effects on phasic DA regulation. Subjects with greater DAT densities (9 allele) and those with higher COMT activity (Val/Val) may have decreased tonic intrasynaptic DA levels, leading to increased smoking-induced phasic DA release. Autoinhibitory control (through DRD4) may also be important during phasic DA release. A recent literature review supports this theory by suggesting that subjects with the Val/Val genotype of COMT (rapid catabolizers) have lower tonic extraneuronal DA and higher phasic DA subcortically compared with subjects with the Met allele.59

In the present study, evidence was again found for human smoking-induced DA release; however, the magnitude of change in VCD/NAc BP was smaller in this larger subject sample (n=35) scanned on a newer scanner than in our previous study15 (−8.4% for the new group compared with −25.9% to −36.6% for the ventral striatal regions of interest in the previous study15). While the new data call into question the magnitude of DA release with human smoking, they reaffirm the presence of smoking-induced DA release because 2 separate samples (using methodology blinded to subject condition) have now shown significant group differences between those who did and did not smoke during a 10-minute break in scanning in the hypothesized direction. The association between decreased craving and increased DA release was also found again, and all of these findings were more robust for the VCD/NAc than for dorsal basal ganglia VOIs.

This study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. A first potential confound is that subjects were removed from the scanner and repositioned after smoking, which could potentially lead to differences in region placement on prebreak and postbreak scans because of imperfect repositioning. Although efforts were made to reposition the subjects precisely and regions were drawn on coregistered MRI images, it is possible that movement or imperfect alignment of scans led to slight differences in regions for the prebreak and postbreak scans. A second potential confound is that smoking might alter [11C]raclopride BP by effects on blood flow93,94 rather than DA release. In our previous15 and present studies, cerebellar activity (a measure of nonspecific binding) showed little change from before to after the break in either the nonsmoking or the smoking groups, indicating that our results were not strongly influenced by blood flow changes from smoking. Third, although subjects were monitored continuously during the break while they were standing in the outdoor area, subtle movements of hands or feet were not systematically examined. Rapid repetitive movements, such as finger tapping95 and foot extension/flexion96 (but not vigorous exercise97), have been shown to decrease [11C]raclopride BP and may present a confound if those who smoked differed from those who did not smoke in their movements. Studies comparing regular cigarette smoking with smoking of denicotinized cigarettes and/or nicotine administration would help clarify the role of movement in the present findings. And fourth, there is inherent variability in [11C]raclopride PET scanning due to technical issues in scanning and scan analysis87,98 and subject differences in radiotracer clearance,80 which may have increased variability for the BP measures found here.

In summary, this study demonstrates that genotypic differences may account for interindividual differences in smoking-induced DA release. In addition, the present study also demonstrates (indirectly) cigarette smoking-induced striatal DA release in humans. An association between decreased craving and increased DA concentration with smoking was also found. These results may have future implications for subtyping smokers based on clinical characteristics and possibly for identifying smokers who would be more likely to respond to dopaminergic pharmacotherapies or those therapies that affect the brain DA system.

Acknowledgment

We thank Josephine Ribe and Michael Clark for technical assistance in performing positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans, respectively.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants R01 DA15059, DA20872, and DA14093 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (A.L.B. and E.D.L.), a Veterans Affairs Type I Merit Review Award (A.L.B.), grants 11RT-0024 and 10RT-0091 from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (A.L.B. and E.D.L.), an Independent Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (A.L.B.), grant K24 MH01805 from the National Institute of Mental Health (J.T.M.), and contract DABT63-00-C-1003 from the Office of National Drug Control Policy (E.D.L.).

Footnotes

Previous Presentations: This study was presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 12-16, 2004; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and the 11th Annual Duke Nicotine Research Conference; November 10, 2005; Durham, NC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leshner AI, Koob GF. Drugs of abuse and the brain. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1999;111:99–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1381.1999.09218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koob GF. Drugs of abuse: anatomy, pharmacology and function of reward pathways. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90060-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner EL. Brain reward mechanisms. In: Lowinson JH, Ruiz P, Millman RB, editors. Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. 2nd ed. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore, Md: 1992. pp. 70–99. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayfield RD, Popp RL, Machu TK, London ED, Grant SJ, Morgan MJ, Zukin SR. Neurobiology of drug abuse. In: Fogel BS, Schiffer RB, Rao SM, editors. Neuropsychiatry. 2nd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, Pa: 2003. pp. 840–892. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5274–5278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pontieri FE, Tanda G, Orzi F, Di Chiara G. Effects of nicotine on the nucleus accumbens and similarity to those of addictive drugs. Nature. 1996;382:255–257. doi: 10.1038/382255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sziraki I, Lipovac MN, Hashim A, Sershen H, Allen D, Cooper T, Czobor P, Lajtha A. Differences in nicotine-induced dopamine release and nicotine pharmacokinetics between Lewis and Fischer 344 rats. Neurochem Res. 2001;26:609–617. doi: 10.1023/a:1010979018217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damsma G, Day J, Fibiger HC. Lack of tolerance to nicotine-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;168:363–368. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90798-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corrigall WA, Franklin KB, Coen KM, Clarke PB. The mesolimbic dopaminergic system is implicated in the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107:285–289. doi: 10.1007/BF02245149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowell PP, Carr LA, Garner AC. Stimulation of [3H]dopamine release by nicotine in rat nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem. 1987;49:1449–1454. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakurai Y, Takano Y, Kohjimoto Y, Honda K, Kamiya HO. Enhancement of [3H]dopamine release and its [3H]metabolites in rat striatum by nicotinic drugs. Brain Res. 1982;242:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90499-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connelly MS, Littleton JM. Lack of stereoselectivity in ability of nicotine to release dopamine from rat synaptosomal preparations. J Neurochem. 1983;41:1297–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marien M, Brien J, Jhamandas K. Regional release of [3H]dopamine from rat brain in vitro: effects of opioids on release induced by potassium, nicotine, and L-glutamic acid. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1983;61:43–60. doi: 10.1139/y83-005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westfall TC, Grant H, Perry H. Release of dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine from rat striatal slices following activation of nicotinic cholinergic receptors. Gen Pharmacol. 1983;14:321–325. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(83)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brody AL, Olmstead RE, London ED, Farahi J, Meyer JH, Grossman P, Lee GS, Huang J, Hahn EL, Mandelkern MA. Smoking-induced ventral striatum dopamine release. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1211–1218. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrett SP, Boileau I, Okker J, Pihl RO, Dagher A. The hedonic response to cigarette smoking is proportional to dopamine release in the human striatum as measured by positron emission tomography and [(11)C]raclopride. Synapse. 2004;54:65–71. doi: 10.1002/syn.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batra V, Patkar AA, Berrettini WH, Weinstein SP, Leone FT. The genetic determinants of smoking. Chest. 2003;123:1730–1739. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.5.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pomerleau OF. Individual differences in sensitivity to nicotine: implications for genetic research on nicotine dependence. Behav Genet. 1995;25:161–177. doi: 10.1007/BF02196925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pohjalainen T, Rinne JO, Nagren K, Lehikoinen P, Anttila K, Syvalahti EK, Hietala J. The A1 allele of the human D2 dopamine receptor gene predicts low D2 receptor availability in healthy volunteers. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3:256–260. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonsson EG, Nothen MM, Grunhage F, Farde L, Nakashima Y, Propping P, Sedvall GC. Polymorphisms in the dopamine D2 receptor gene and their relationships to striatal dopamine receptor density of healthy volunteers. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4:290–296. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pohjalainen T, Nagren K, Syvalahti EK, Hietala J. The dopamine D2 receptor 5′-flanking variant, −141C Ins/Del, is not associated with reduced dopamine D2 receptor density in vivo. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:505–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laruelle M, Gelernter J, Innis RB. D2 receptors binding potential is not affected by Taq1 polymorphism at the D2 receptor gene. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3:261–265. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nisell M, Nomikos GG, Svensson TH. Systemic nicotine-induced dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens is regulated by nicotinic receptors in the ventral tegmental area. Synapse. 1994;16:36–44. doi: 10.1002/syn.890160105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanca AJ, Adamson KL, Coen KM, Chow BL, Corrigall WA. The pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus and the role of cholinergic neurons in nicotine self-administration in the rat: a correlative neuroanatomical and behavioral study. Neuroscience. 2000;96:735–742. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00607-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uhl GR, Lin Z. The top 20 dopamine transporter mutants: structure-function relationships and cocaine actions. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;479:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergson C, Levenson R, Goldman-Rakic PS, Lidow MS. Dopamine receptor-interacting proteins: the Ca(2+) connection in dopamine signaling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:486–492. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamada M, Higashi H, Nairn AC, Greengard P, Nishi A. Differential regulation of dopamine D1 and D2 signaling by nicotine in neostriatal neurons. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1094–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong AHC, Van Tol HHM. The dopamine D-4 receptors and mechanisms of antipsychotic atypicality. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kopin IJ. Monoamine oxidase and catecholamine metabolism. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1994;41:57–67. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9324-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vandenbergh DJ, Persico AM, Hawkins AL, Griffin CA, Li X, Jabs EW, Uhl GR. Human dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) maps to chromosome 5p15.3 and displays a VNTR. Genomics. 1992;14:1104–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Comings DE, Wu S, Chiu C, Ring RH, Gade R, Ahn C, MacMurray JP, Dietz G, Muhleman D. Polygenic inheritance of Tourette syndrome, stuttering, attention deficit hyperactivity, conduct, and oppositional defiant disorder: the additive and subtractive effect of the three dopaminergic genes, DRD2, D beta H, and DAT1. Am J Med Genet. 1996;67:264–288. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960531)67:3<264::AID-AJMG4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahn RS, Khoury J, Nichols WC, Lanphear BP. Role of dopamine transporter genotype and maternal prenatal smoking in childhood hyperactive-impulsive, inattentive, and oppositional behaviors. J Pediatr. 2003;143:104–110. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(03)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samochowiec J, Rybakowski F, Czerski P, Zakrzewska M, Stepien G, Pelka-Wysiecka J, Horodnicki J, Rybakowski JK, Hauser J. Polymorphisms in the dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine transporter genes and their relationship to temperamental dimensions measured by the Temperament and Character Inventory in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychobiology. 2001;43:248–253. doi: 10.1159/000054898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heinz A, Goldman D, Jones DW, Palmour R, Hommer D, Gorey JG, Lee KS, Linnoila M, Weinberger DR. Genotype influences in vivo dopamine transporter availability in human striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:133–139. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobsen LK, Staley JK, Zoghbi SS, Seibyl JP, Kosten TR, Innis RB, Gelernter J. Prediction of dopamine transporter binding availability by genotype: a preliminary report. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1700–1703. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Dyck CH, Malison RT, Jacobsen LK, Seibyl JP, Staley JK, Laruelle M, Baldwin RM, Innis RB, Gelernter J. Increased dopamine transporter availability associated with the 9-repeat allele of the SLC6A3 gene. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:745–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez D, Gelernter J, Abi-Dargham A, van Dyck CH, Kegeles L, Innis RB, Laruelle M. The variable number of tandem repeats polymorphism of the dopamine transporter gene is not associated with significant change in dopamine transporter phenotype in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:553–560. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynch DR, Mozley PD, Sokol S, Maas NM, Balcer LJ, Siderowf AD. Lack of effect of polymorphisms in dopamine metabolism related genes on imaging of TRO-DAT-1 in striatum of asymptomatic volunteers and patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2003;18:804–812. doi: 10.1002/mds.10430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Contin M, Martinelli P, Mochi M, Albani F, Riva R, Scaglione C, Dondi M, Fanti S, Pettinato C, Baruzzi A. Dopamine transporter gene polymorphism, spect imaging, and levodopa response in patients with Parkinson disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27:111–115. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson J, Thomas N, Singleton A, Piggott M, Lloyd S, Perry EK, Morris CM, Perry RH, Ferrier IN, Court JA. D2 dopamine receptor gene (DRD2) Taq1 A polymorphism: reduced dopamine D2 receptor binding in the human striatum associated with the A1 allele. Pharmacogenetics. 1997;7:479–484. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199712000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noble EP, Blum K, Ritchie T, Montgomery A, Sheridan PJ. Allelic association of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with receptor-binding characteristics in alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:648–654. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ritchie T, Noble EP. Association of seven polymorphisms of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with brain receptor-binding characteristics. Neurochem Res. 2003;28:73–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1021648128758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Comings DE, Ferry L, Bradshaw-Robinson S, Burchette R, Chiu C, Muhleman D. The dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) gene: a genetic risk factor in smoking. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:73–79. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199602000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Audrain-McGovern J, Lerman C, Wileyto EP, Rodriguez D, Shields PG. Interacting effects of genetic predisposition and depression on adolescent smoking progression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1224–1230. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.David SP, Niaura R, Papandonatos GD, Shadel WG, Burkholder GJ, Britt DM, Day A, Stumpff J, Hutchison K, Murphy M, Johnstone E, Griffiths SE, Walton RT. Does the DRD2-Taq1 A polymorphism influence treatment response to bupropion hydrochloride for reduction of the nicotine withdrawal syndrome? Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:935–942. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001615295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swan GE, Valdes AM, Ring HZ, Khroyan TV, Jack LM, Ton CC, Curry SJ, McAfee T. Dopamine receptor DRD2 genotype and smoking cessation outcome following treatment with bupropion SR. Pharmacogenomics J. 2005;5:21–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cinciripini P, Wetter D, Tomlinson G, Tsoh J, De Moor C, Cinciripini L, Minna J. The effects of the DRD2 polymorphism on smoking cessation and negative affect: evidence for a pharmacogenetic effect on mood. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:229–239. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001676396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lerman C, Berrettini W, Pinto A, Patterson F, Crystal-Mansour S, Wileyto EP, Restine SL, Leonard DG, Shields PG, Epstein LH. Changes in food reward following smoking cessation: a pharmacogenetic investigation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:571–577. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1823-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang L, Todd RD, O’Malley KL. Dopamine D2 and D3 receptors inhibit dopamine release. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:475–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pothos EN, Przedborski S, Davila V, Schmitz Y, Sulzer D. D2-Like dopamine autoreceptor activation reduces quantal size in PC12 cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5575–5585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-15-05575.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asghari V, Sanyal S, Buchwaldt S, Paterson A, Jovanovic V, Van Tol HH. Modulation of intracellular cyclic AMP levels by different human dopamine D4 receptor variants. J Neurochem. 1995;65:1157–1165. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65031157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seeger G, Schloss P, Schmidt MH. Marker gene polymorphisms in hyperkinetic disorder: predictors of clinical response to treatment with methylphenidate? Neurosci Lett. 2001;313:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shields PG, Lerman C, Audrain J, Bowman ED, Main D, Boyd NR, Caporaso NE. Dopamine D4 receptors and the risk of cigarette smoking in African-Americans and Caucasians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feldpausch DL, Needham LM, Stone MP, Althaus JS, Yamamoto BK, Svensson KA, Merchant KM. The role of dopamine D4 receptor in the induction of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine and accompanying biochemical and molecular adaptations. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:497–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Broderick PA, Piercey MF. Clozapine, haloperidol, and the D4 antagonist PNU-101387G: in vivo effects on mesocortical, mesolimbic, and nigrostriatal dopamine and serotonin release. J Neural Transm. 1998;105:749–767. doi: 10.1007/s007020050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lachman HM, Papolos DF, Saito T, Yu YM, Szumlanski CL, Weinshilboum RM. Human catechol-O-methyltransferase pharmacogenetics: description of a functional polymorphism and its potential application to neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:243–250. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199606000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vandenbergh DJ, Rodriguez LA, Miller IT, Uhl GR, Lachman HM. High-activity catechol-O-methyltransferase allele is more prevalent in polysubstance abusers. Am J Med Genet. 1997;74:439–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsai SJ, Hong CJ, Yu YW, Chen TJ. Association study of catechol-O-methyltransferase gene and dopamine D4 receptor gene polymorphisms and personality traits in healthy young Chinese females. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;50:153–156. doi: 10.1159/000079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bilder RM, Volavka J, Lachman HM, Grace AA. The catechol-o-methyltransferase polymorphism: relations to the tonic-phasic dopamine hypothesis and neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1943–1961. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Munafo M, Clark T, Johnstone E, Murphy M, Walton R. The genetic basis forsmoking behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:583–597. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001734030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li MD, Ma JZ, Beuten J. Progress in searching for susceptibility loci and genes for smoking-related behaviour. Clin Genet. 2004;66:382–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feng Y, Niu T, Xing H, Xu X, Chen C, Peng S, Wang L, Laird N, Xu X. A common haplotype of the nicotine acetylcholine receptor alpha 4 subunit gene is associated with vulnerability to nicotine addiction in men. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:112–121. doi: 10.1086/422194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnstone EC, Yudkin PL, Hey K, Roberts SJ, Welch SJ, Murphy MF, Griffiths SE, Walton RT. Genetic variation in dopaminergic pathways and short-term effectiveness of the nicotine patch. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:83–90. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singleton AB, Thomson JH, Morris CM, Court JA, Lloyd S, Cholerton S. Lack of association between the dopamine D2 receptor gene allele DRD2*A1 and cigarette smoking in a United Kingdom population. Pharmacogenetics. 1998;8:125–128. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199804000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bierut LJ, Rice JP, Edenberg HJ, Goate A, Foroud T, Cloninger CR, Begleiter H, Conneally PM, Crowe RR, Hesselbrock V, Li TK, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Porjesz B, Schuckit MA, Reich T. Family-based study of the association of the dopamine D2 receptor gene (DRD2) with habitual smoking. Am J Med Genet. 2000;90:299–302. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000214)90:4<299::aid-ajmg7>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jorm AF, Henderson AS, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Korten AE, Rodgers B, Tan X, Easteal S. Association of smoking and personality with a polymorphism of the dopamine transporter gene: results from a community survey. Am J Med Genet. 2000;96:331–334. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20000612)96:3<331::aid-ajmg19>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.David SP, Johnstone E, Griffiths SE, Murphy M, Yudkin P, Mant D, Walton R. No association between functional catechol O-methyl transferase 1947A>G polymorphism and smoking initiation, persistent smoking or smoking cessation. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:265–268. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200204000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lerman C, Caporaso NE, Audrain J, Main D, Bowman ED, Lockshin B, Boyd NR, Shields PG. Evidence suggesting the role of specific genetic factors in cigarette smoking. Health Psychol. 1999;18:14–20. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vandenbergh DJ, Bennett CJ, Grant MD, Strasser AA, O’Connor R, Stauffer RL, Vogler GP, Kozlowski LT. Smoking status and the human dopamine transporter variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) polymorphism: failure to replicate and finding that never-smokers may be different. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:333–340. doi: 10.1080/14622200210142689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lerman C, Swan GE. Non-replication of genetic association studies: is DAT all, folks? Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:247–249. doi: 10.1080/14622200210141220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sabol SZ, Nelson ML, Fisher C, Gunzerath L, Brody CL, Hu S, Sirota LA, Marcus SE, Greenberg BD, Lucas FR, Benjamin J, Murphy DL, Hamer DH. A genetic association for cigarette smoking behavior. Health Psychol. 1999;18:7–13. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 1995. Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, version 2.0) [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fagerström KO. Measuring the degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 1978;3:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jarvik ME, Madsen DC, Olmstead RE, Iwamoto-Schaap PN, Elins JL, Benowitz NL. Nicotine blood levels and subjective craving for cigarettes. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:553–558. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, Calif: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hamilton M. Diagnosis and rating of anxiety. Br J Psychiatry. 1969;3:76–79. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carson RE, Breier A, de Bartolomeis A, Saunders RC, Su TP, Schmall B, Der MG, Pickar D, Eckelman WC. Quantification of amphetamine-induced changes in [11C]raclopride binding with continuous infusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:437–447. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ito H, Hietala J, Blomqvist G, Halldin C, Farde L. Comparison of the transient equilibrium and continuous infusion method for quantitative PET analysis of [11C]raclopride binding. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:941–950. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199809000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schuh KJ, Stitzer ML. Desire to smoke during spaced smoking intervals. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120:289–295. doi: 10.1007/BF02311176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Farde L, Hall H, Ehrin E, Sedvall G. Quantitative analysis of D2 dopamine receptor binding in the living human brain by PET. Science. 1986;231:258–261. doi: 10.1126/science.2867601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ehrin E, Gawell L, Hogberg T, Depaulis T, Strom P. Synthesis of [methoxy-H-3]- and [methoxy-C-11]-labeled raclopride: specific dopamine-D2 receptor ligands. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 1987;24:931–940. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Woods RP, Mazziotta JC, Cherry SR. MRI-PET registration with automated algorithm. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17:536–546. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage. 1996;4:153–158. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Watabe H, Endres CJ, Breier A, Schmall B, Eckelman WC, Carson RE. Measurement of dopamine release with continuous infusion of [11C]raclopride: optimization and signal-to-noise considerations. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mawlawi O, Martinez D, Slifstein M, Broft A, Chatterjee R, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Simpson N, Ngo K, Van Heertum R, Laruelle M. Imaging human mesolimbic dopamine transmission with positron emission tomography: I. Accuracy and precision of D(2) receptor parameter measurements in ventral striatum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1034–1057. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Imperato A, Mulas A, Di Chiara G. Nicotine preferentially stimulates dopamine release in the limbic system of freely moving rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;132:337–338. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90629-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Benwell ME, Balfour DJ. Regional variation in the effects of nicotine on catecholamine overflow in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;325:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Janhunen S, Ahtee L. Comparison of the effects of nicotine and epibatidine on the striatal extracellular dopamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;494:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marenco S, Carson RE, Berman KF, Herscovitch P, Weinberger DR. Nicotineinduced dopamine release in primates measured with [C-11]raclopride PET. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:259–268. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rice ME, Cragg SJ. Nicotine amplifies reward-related dopamine signals in striatum. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:583–584. doi: 10.1038/nn1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mathew RJ, Wilson WH. Substance abuse and cerebral blood flow. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:292–305. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Boyajian RA, Otis SM. Acute effects of smoking on human cerebral blood flow: a transcranial Doppler ultrasonography study. J Neuroimaging. 2000;10:204–208. doi: 10.1111/jon2000104204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Goerendt IK, Messa C, Lawrence AD, Grasby PM, Piccini P, Brooks DJ. Dopamine release during sequential finger movements in health and Parkinson’s disease: a PET study. Brain. 2003;126:312–325. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ouchi Y, Yoshikawa E, Futatsubashi M, Okada H, Torizuka T, Sakamoto M. Effect of simple motor performance on regional dopamine release in the striatum in Parkinson disease patients and healthy subjects: a positron emission to-mography study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:746–752. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200206000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Franceschi D, Logan J, Pappas NR, Wong CT, Netusil N. PET studies of the effects of aerobic exercise on human striatal dopamine release. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1352–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Dewey SL, Schlyer D, MacGregor R, Logan J, Alexoff D, Shea C, Hitzemann R. Reproducibility of repeated measures of carbon-11-raclopride binding in the human brain. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:609–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]