The hazards of blood transfusion in historical perspective (original) (raw)

Abstract

The beginning of the modern era of blood transfusion coincided with World War II and the resultant need for massive blood replacement. Soon thereafter, the hazards of transfusion, particularly hepatitis and hemolytic transfusion reactions, became increasingly evident. The past half century has seen the near eradication of transfusion-associated hepatitis as well as the emergence of multiple new pathogens, most notably HIV. Specific donor screening assays and other interventions have minimized, but not eliminated, infectious disease transmission. Other transfusion hazards persist, including human error resulting in the inadvertent transfusion of incompatible blood, acute and delayed transfusion reactions, transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease (TA-GVHD), and transfusion-induced immunomodulation. These infectious and noninfectious hazards are reviewed briefly in the context of their historical evolution.

Introduction

“Blood transfusion is like marriage: it should not be entered upon lightly, unadvisedly or wantonly or more often than is absolutely necessary.” This tongue-in-cheek simile from Robert Beal has an inherent truth that serves as the foundation for this historical review. Although blood transfusion is increasingly safe, it remains hazardous in many respects, and its history is replete with severe, sometimes fatal, complications that are both infectious and noninfectious in origin. Only the highlights can be chronicled in this brief overview.

Infectious hazards

Transfusion-associated hepatitis

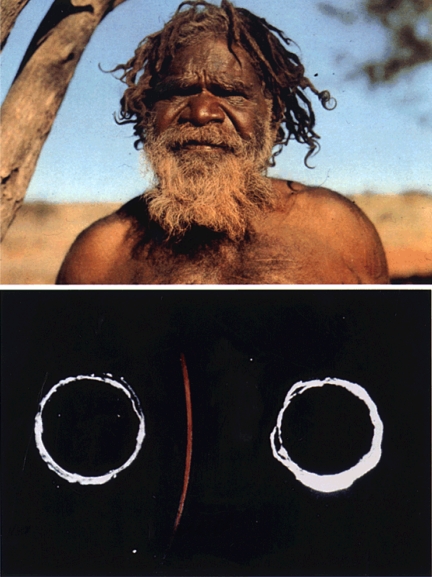

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) was just a gleam in William Dameshek's eye when serum hepatitis emerged as a major hazard of blood transfusion among surviving battlefield casualties of World War II. Whereas ASH was rapidly organized in the aftermath of the war, it took nearly 3 decades before the hepatitis B virus, then termed the serum hepatitis virus, was identified and a blood screening test developed. This arduous path from observation to discovery culminated in the serendipitous finding of the Australia antigen in 1963.1 In the early 1960s, Baruch Blumberg, a geneticist then at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), discovered polymorphisms in human β-lipoproteins using the technique of Ouchterlony immuodiffusion.2 Harvey Alter, then a clinical fellow in transfusion medicine at NIH, was using the same technique to investigate whether antibodies to human protein variants might cause transfusion reactions. The similarity of approaches, albeit to different ends, led to a collaboration that screened the serum of multiply transfused patients against the serum of diverse global populations for evidence of antibodies to polymorphic proteins. A characteristic of lipoprotein immunoprecipitates was that they stained blue when a lipid stain was applied. In 1963, a precipitin was observed that stained only weakly for lipid, but intensely red when counterstained for protein. It was this “thin red line,” the result of the interaction between the serum of a multiply transfused hemophiliac patient from Brooklyn and the serum of an Australian aborigine, that ultimately became the breakthrough finding in the then semidormant field of hepatitis research (Figure 1). Initially called the “red antigen,” it was subsequently termed the Australia antigen (Au) and, later, the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).

Figure 1.

Au antigen discovery. An Australian aborigine (top) and the precipitin line formed between the aboriginal serum and that of a multiply transfused patient with hemophilia (bottom). The precipitin failed to stain for lipid, but stained red with the azocarmine counterstain for protein. Reprinted with permission of Nature Publishing Group from Alter HJ and Houghton M, Hepatitis C virus and eliminating posttransfusion hepatitis (Nat Med. 2000;6:1082-1086).

Early investigations of Au sought prevalence and disease associations. Interestingly, the antigen was found in 0.1% of the normal donor population but in 10% of patients with leukemia. Thus, when the first paper to describe Au was published in 1965,1 it made note of the association with leukemia and even speculated that this antigen might be part of the then postulated leukemia virus. At the time of discovery, there was no sense that this cryptic red antigen would unravel a hepatitis mystery that dates to early descriptions by Hippocrates.

In 1964, Blumberg moved to the Institute for Cancer Research in Philadelphia, where he continued to unravel the Au conundrum. He believed at the time that Au was a genetically determined human protein that possibly enhanced susceptibility to leukemia, and thus elected to study patients with Down syndrome, who had an inherited predisposition to leukemia. Although initiated on a faulty premise, study findings were definitive and highly relevant: Down patients who resided in large institutions had an Au prevalence of 30%, whereas those in smaller institutions had a prevalence of 10%, and those living at home only 3%; the antigen was absent in newborn Down cases.3 This observation suggested that Au was not inherited, but rather a manifestation of crowded living conditions and thus possibly related to an unidentified infectious agent. This background was prelude to a serendipitous event. A technologist in the Blumberg lab who had long served as an Au-negative control retested her blood at the time she was feeling ill and turning icteric. Her previously Au-negative blood tested strongly positive, coincident with the onset of classic acute hepatitis. This initial link to a hepatitis virus was confirmed in expanded studies4 and subsequently shown to be specific for the hepatitis B virus.5 In retrospect, these findings nicely explained the association with institutionalized patients and the high prevalence in patients with leukemia, who were both highly exposed by transfusion and immunosuppressed with a proclivity to the HBV carrier state.

Thus, through observation, serendipity, and perseverance, a unique antigen was found that proved to be an integral part of the hepatitis B virus envelope protein and then served as the foundation for (1) the first donor screening and diagnostic assay for human hepatitis; (2) a highly effective hepatitis B vaccine that not only prevents hepatitis B, but also prevents HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma; and (3) the recognition of non-A, non-B (NANB) hepatitis by serologic exclusion and hence, ultimately set the stage for the discovery of the hepatitis C virus. This is a heady outcome for a single precipitin line that stained the wrong way.

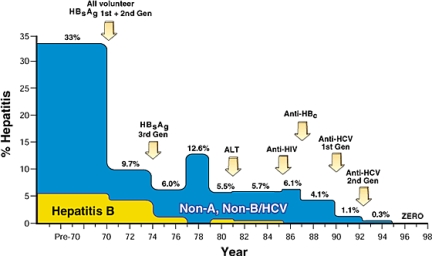

In 1967, prospective studies of posttransfusion hepatitis were initiated at NIH by Bob Purcell, Paul Holland, Paul Schmidt, and John Walsh and then continued over the course of almost 3 decades by this author (H.J.A.). The earliest study in this seriesshowed that the incidence of TAH in multiply transfused cardiac surgery patients astonishingly exceeded 30% and that much of that risk was due to the use of paid donor blood.6 In 1970, the NIH Blood Bank simultaneously adopted an all-volunteer donor system and introduced a first-generation agar gel assay to screen for HBsAg. The outcome of this dual intervention was dramatic—hepatitis rates fell by 70% to a new baseline level of approximately 10%7 (Figure 2). Retrospective testing showed that only 25% of TAH was hepatitis B–related, leaving 75% of cases tentatively classified as non-B hepatitis. By 1973, the development of more sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) screening assays for the detection of HBsAg led to the near eradication of hepatitis B cases within our study population (Figure 2). In 1975, Feinstone, Kapikian, and Purcell8 at NIH discovered the hepatitis A virus (HAV), and we immediately tested stored sera from our non-B hepatitis cases. Surprisingly, not a single case was due to HAV, the only other known hepatitis virus at that time. Hence, the origin of the designation “non-A, non-B hepatitis,”9 a descriptive term that we thought would be short-lived, but the agent defied serologic definition for almost 15 years. However, in the interim, the infectious nature of the NANB agent was proved in a series of chimpanzee transmission studies,10,11 and its physical characteristics were partially defined by testing the effects of in vitro manipulations on subsequent infectivity in the chimp. In this way it was shown that the NANB agent was lipid-encapsidated12 and 30 nm to 60 nm in diameter.13 These experiments narrowed the taxonomic range of viral agents to be considered and raised the possibility that the NANB agent might be a flavivirus, as first suggested by Bradley14 and as eventually proved true. Of most significance, prospective follow-up showed that NANB hepatitis was generally a persistent infection and that it evolved to cirrhosis in approximately 20% of cases,15 an incidence that is still valid today.

Figure 2.

The decreasing incidence of transfusion-associated hepatitis in blood recipients monitored prospectively. Incidence, traced from 1969 to 1998, demonstrates a decrease in risk from 33% to nearly zero. Arrows indicate main interventions in donor screening and selection that effected this change. Reprinted with permission of Nature Publishing Group from Alter HJ and Houghton M, Hepatitis C virus and eliminating post-transfusion hepatitis (Nat Med. 2000;6:1082-1086).

In the 1980s, we attempted various surrogate interventions to prevent TAH, particularly alanine amino-transferase (ALT) and anti-hepatitis B core (anti-HBc) testing of donor blood. Both these interventions were predicted to have 30% to 40% efficacy in retrospective analyses of stored donor and recipient samples.16,17 However, their impact in prospective follow-up was marginal. Nonetheless, as the cumulative result of surrogate testing, anti-HIV testing, and the more judicious use of blood in the wake of the AIDS epidemic, hepatitis incidence had fallen to 4% by 1989 (Figure 2). At that time, Houghton and associates at Chiron Corporation cloned the NANB agent and called it hepatitis C virus (HCV).18 To validate their discovery, Chiron requested a coded NANB panel that we had constructed from pedigreed sera proven to transmit NANB infection to humans or chimpanzees. Although multiple other claims of NANB discovery had failed this panel, Chiron broke the code flawlessly. We then selected 15 characteristic NANB hepatitis cases from the NIH prospective study and showed that each patient developed anti-HCV antibody in temporal relation to their acute TAH, and that a positive donor could be identified in 80% to 88% of cases.19 Hence, NANB metamorphosed seamlessly into HCV. Houghton and coworkers' unique application of the then emerging field of molecular biology was a monumental effort extending over 6 years that culminated in the first donor screening test for antibody to HCV in 1990. Hepatitis incidence then fell from 4% to 1.5% and a second-generation anti-HCV assay introduced in 1992 achieved virtual zero incidence (Figure 2). At present, TAH incidence is so low that it has to be mathematically modeled, and the risk of hepatitis C is calculated to be 1 case in every 1.5 million to 2 million exposures, a remarkable incidence compared with the 30% rate that prevailed in 1970 and the 10% rate in 1980.

Transfusion-transmitted HIV

As the hepatitis story was evolving slowly through the 1970s and early 1980s, a new disease exploded into recognition and struck terror into both blood recipients and those responsible for the blood supply. In 1981, unusual opportunistic infections and cancers, particularly Pneumocystis carinii and Kaposi sarcoma (KS), were reported for the first time among men who have sex with men (MSMs).20 Originally localized to New York and California, this acquired immunodeficiency disease spread rapidly; by May 1982, 1 year after the first case report, 355 cases had been recognized in the United States,21 primarily in MSMs, injection drug users (IDU), and persons immigrating from Haiti. Concern for transmission by transfusion was aroused in late 1982 when 3 cases were observed in patients with hemophilia A in whom clotting factor concentrates were the only probable source.22 Further evidence for transfusion transmission came in 1983, when a multiply transfused infant developed immunodeficiency and opportunistic infections posttransfusion, and 1 platelet donor to this infant was found to have developed AIDS 10 months after the index donation.23 In the absence of an identified agent and an appropriate screening test, transfusion-associated AIDS cases continued to accrue at alarming rates. By 1992 there were 9261 cases of AIDS attributed to blood transfusion administered before the introduction of anti-HIV screening assays in 1985. The total number of transfusion-related HIV infections has been estimated at 12 000.24 Of the 37 019 AIDS cases identified by 1987, 741 (2%) were in transfused adults, 61 (0.2%) in transfused children, and 364 (1%) in recipients of clotting factor concentrates.25 Among all AIDS cases in children, transfusion accounted for 12%. Tragically, based on surveys in 1982-1984, 74% of persons with factor VIII deficiency and 39% of those with factor IX deficiency were anti–HIV-positive.26 Approximately 90% of severe hemophiliacs were HIV-infected before the first case of AIDS was recognized in 1981.

A dramatic and remarkable decrease in the incidence of transfusion-transmitted AIDS followed the groundbreaking discovery of HIV in late 1983 and 1984 by investigative groups led by Luc Montaigne27 and Robert Gallo.28 Within a year of these discoveries, an assay for anti-HIV was licensed and used to test all transfused products; HIV prevalence in volunteer donors at that time was 0.04%. Since the implementation of donor screening, only 49 transfusion-associated cases have been identified, primarily from window period donations before the introduction of nucleic acid screening tests for HIV RNA in 2000. No cases have been attributed to clotting factor concentrates after the introduction of virocidal treatments in the early 1980s. The current risk of transfusion-transmitted HIV is estimated to be 1 case per 2 million transfusions.

The blood bank community has been chastised for its perceived failure to act during the early years of the AIDS epidemic, and many lawsuits were brought based on the failure to introduce anti–hepatitis B core testing as a surrogate marker for HIV and for being late to introduce inactivation measures for clotting factor concentrates. In retrospect, both of these measures would have been highly effective, but the decisions were not easy when viewed in real time. It is hard to convey the pressures existing in 1982 to 1984 in the face of an exploding epidemic of a fatal disease whose etiology was unknown, whose link to transfusion was initially tenuous, whose prevention by direct blood screening was impossible, whose prevention by indirect means would significantly diminish the blood supply, and whose primary risk groups brought pressure not to be excluded as blood donors by virtue of lifestyle. We write this not as apologists for early inaction, but to portray the immense, seemingly insurmountable dilemmas that existed at the time.

One positive outcome of the AIDS tragedy was adoption of a new paradigm in blood transfusion, the precautionary principle, which states that “for situations of scientific uncertainty, the possibility of risk should be taken into account in the absence of proof to the contrary” and that “measures need to be taken to face potential serious risks.”29 This paradigm for action has served well to protect against emerging infections that followed in the wake of HIV. Nonetheless, in the absence of preemptive pathogen inactivation, the blood supply remains vulnerable to an emerging, potentially lethal agent that, like HIV, has a long asymptomatic viremic phase before disease recognition.

Zoonotic infections that threaten the blood supply

The most recent threats to the blood supply have been agents that primarily affect animals but, through efficient mosquito or tick vectors or the food supply, have adapted to humans as secondary hosts and have spread by transfusion because of an ensuing circulatory phase. These vector-borne agents include Plasmodium spp (malaria), dengue fever virus, West Nile virus (WNV), Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas disease), Babesia spp (babesiosis), human herpesvirus-8 (KS virus), and others. These are not newly emergent viruses, as was HIV, but rather have emerged as new threats due to changing population dynamics or altered migration patterns of intermediate hosts and vectors.

WNV is a case in point. Previously confined to Africa, India, and the Middle East, in 1999 it suddenly appeared in the New York City borough of Queens, perhaps transported by a single infected bird or a mosquito hitching a ride on a 747. Fifty-nine clinical cases of WNV infection were identified in the 1999 New York outbreak.30 By 2002 to 2003, nearly 14 000 symptomatic cases of WNV fever or meningoencephalitis had been identified across the entire continent, including Canada and Mexico; it is estimated that several hundred thousand individuals were infected. From this reservoir, 4 transplant-associated cases31 and 23 transfusion-transmitted symptomatic cases32 were identified by 2002, and it is estimated that at least 100 times that number of asymptomatic infections also occurred. A nucleic acid test for WNV was developed very rapidly and implemented in time for the mosquito season of 2003. Testing has identified and interdicted more than 2000 potentially infectious blood components during the test's first 3 years of use.33 Residual transfusion cases are now exceedingly rare.

Variant Creutzfeld-Jakob disease (vCJD) exemplifies a truly emergent disease passed through the food chain to humans and from them to other humans through blood transfusion. vCJD is not strictly an infectious disease, but it behaves as such because of transmissible, abnormally folded prions that cause the human equivalent of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, or “mad cow disease”). Cows were infected by feed (offal) contaminated by prion-contaminated neurologic tissue from sheep with scrapie. The BSE epidemic spread rapidly in the United Kingdom until controlled by cattle slaughter and bans on offal production. Approximately 8 years after the beginning of the BSE epidemic, unusual cases of a neurologic disease, primarily in young adults, began to appear in the United Kingdom and were shown to be due to a BSE-like variant that was designated vCJD. This added to the growing list of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs). Approximately 160 cases of human vCJD disease have been recognized in the United Kingdom and 30 elsewhere in the world34 and have been attributed to ground beef products that contained neurologic tissue from BSE-infected cattle. Four transfusion-transmitted cases have been traced to 3 donors who became symptomatic with vCJD 3 or more years after the index donation.35,36 Thus, there is a long asymptomatic carrier state for vCJD that currently defies detection. Furthermore, these abnormally folded prions are highly resistant to inactivation procedures. The primary intervention at present is to indefinitely defer donors who have a history of visiting BSE-affected European countries, particularly Great Britain, during the years of likely exposure. This policy has had substantial impact on blood availability. Considerable efforts are in place to develop assays to detect abnormal prions or filters that would remove them from blood products. Fortunately, as the result of comprehensive public health measures, both BSE and vCJD are on the wane, though neither has been eradicated.

Bacterial contamination

The earliest efforts to interdict a transfusion-transmitted infection involved syphilis. Kilduffe and DeBakey identified more than 100 cases that had been published after 1915, all from direct transfusion.37 Some 138 cases had been reported by 1941. Screening began in 1938 and all blood collections are still tested for the presence of T pallidum. However, spirochetes do not survive well in citrated blood stored for more than 72 hours, so few transmissions have been documented in the developed world since the 1940s. The last case published in the United States was reported from the Clinical Center at the National Institutes of Health in 1969.38

Bacterial contamination of stored blood components originally collected in reusable glass bottles was among the earliest recognized risks of transfusion.39 The introduction of sterile interconnected plastic container systems and controlled refrigeration of blood components seemed to eliminate this risk by the 1960s; however, this proved not to be the case. The risk for RBC transfusion remains very low, estimated at 0.21 infections per million units.40 However, platelet components remain particularly vulnerable to bacterial contamination because their storage temperature (20°-24°C) facilitates microbial growth. For more than 25 years the risk of contamination by bacteria and bacterial pyrogens was largely ignored. Few components were cultured for bacteria and even fewer reports were published. Contamination of platelets is now recognized to have occurred in 1 of every 2000 to 5000 collections before the recent implementation of bacterial testing, and bacterial sepsis from apheresis platelets had been measured at 1 in 15 000 infusions.41,42 Introduction of routine culture within the last 5 years has reduced the risk by approximately 50%. The residual risk of a septic transfusion reaction from a culture-negative single-donor unit has been calculated at 1 in 50 200.43 Approximately half the contaminations come from skin flora, and probably derive from cored skin at the venipuncture site, whereas the remainder probably represent organisms that circulate transiently in the asymptomatic blood donor. Strategies such as improving the venipuncture site skin preparation, diverting and discarding the initial few milliliters of collected blood, and introducing point-of-issue rapid bacterial screening will likely reduce the risk; however the most effective strategy would be introduction of preemptive pathogen reduction that would inactivate bacteria as well as viruses.44

Noninfectious hazards

Hemolytic transfusion reactions

The first clinical transfusions, almost 200 years ago and almost a century before the discovery of blood groups, were associated with a 50% mortality.45 Because the deaths occurred during or shortly after transfusion and because the blood was freshly collected, it is unlikely that infectious agents played any role in these deaths (Figure 3). How many of these deaths were attributable to blood group incompatibility and how many to the severity of the underlying illness remain unknown. Landsteiner's discovery of the major blood groups, although not intended to improve transfusion safety, permitted the first pretransfusion compatibility testing and prevented at least some of the deaths related to ABO incompatibility.46 During the ensuing 50 years, evolving serologic techniques including the direct antiglobulin (Coombs) test led to the discovery of numerous new red-cell antigens and antibodies. Nevertheless, mortality related to acute hemolytic transfusion reactions remained disturbingly frequent well into the 20th century with rates approaching 1 in every 1000 transfusions.37,47 Improved compatibility testing and technology that identifies and links donated blood with laboratory test results and the intended recipient have dramatically reduced the risk, but hardly eliminated it. Acute hemolytic transfusion reactions and related mortality are now estimated at approximately 1 in 76 000 and 1 in 1.8 million units transfused, respectively.48 In the most recent analysis of transfusion-related deaths reported by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 7% were attributed to ABO-associated hemolytic reactions and an additional 20% to non-ABO antibodies.49

Figure 3.

Sketch of Blundell's gravitator. Blood from the donor dripped into a cup fixed several feet above the arm of the recipient and was directed through tubing into the recipient's vein. Adapted from Blundell J, Observations on transfusion (Lancet. 1828;2:321) with permission from Elsevier. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Most deaths from acute hemolysis are still caused by mistakes in identifying blood samples, blood components, and blood recipients. In a recent 10-year period, 1 in every 38 000 red cell units (RBC) transfused in New York state resulted in an error-related ABO-incompatible transfusion.48 Half of these errors occurred outside of the blood bank. A large international survey of 62 hospitals reported, based on 690,000 samples, that 1 in every 165 blood specimens is mislabeled or miscollected.50 In contrast, the use of national patient identification systems in Sweden and Finland has reduced the rates of miscollected samples to levels too low to measure directly. In the United States, the rate of mislabeled samples and miscollected samples is 1000- to 10 000-fold greater than the risk of clinically significant transfusion-transmitted viral infection. We have room for improvement.

In the era of whole blood transfusion, acute hemolysis followed infusion of plasma containing antibodies to red-cell antigens (passively acquired antibody). Today, acute hemolysis resulting from passive antibody is uncommon, because RBCs contain only small amounts of plasma, fresh frozen plasma infusions are restricted to ABO-compatible donors, and acute hemolysis caused by transfused antibodies other than those in the ABO system is unusual. However, severe reactions still occur when mismatched plasma is infused with apheresis platelets.51 A report in Blood underscores the risk of infusing anti-D to treat immune thrombocytopenia.52 In the latter case, the incidence of acute hemolysis is estimated at 1 in 1115 patients treated, and the mechanism of intravascular hemolysis remains unexplained.

Delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions (DHTR) are more common but usually less severe than acute hemolysis. Delayed reactions occur when a patient previously sensitized by pregnancy or transfusion receives “incompatible red cells,” because the low titer of circulating alloantibody escapes detection by pretransfusion testing. Over the years, DHTR have led to the identification of previously undescribed red-cell antigens. Studies from our institution more than 40 years ago determined that red cell alloimmunization occurs at a frequency of approximately 1% per unit transfused, and in up to 36% of transfused patients with sickle cell disease.53,54 We know now that the rate of sensitization is affected by both genetic factors and the patient's immune status. DHTR commonly go unrecognized because they occur several days after transfusion, which today means often after hospital discharge, The low-grade fever, a decline in hemoglobin concentration, fatigue, and mild jaundice commonly go unrecognized.55 However, we and others have noted that DHTR can be severe, even fatal, particularly in patients with sickle cell disease.56 The incidence of DHTR is now estimated at approximately 1 in 6000 units transfused, it but may be decreasing as a result of more effective pretransfusion screening.57 To further reduce the risk of alloimmunization and DHTR, extended red-cell phenotyping using a combination of serology and newly introduced molecular techniques can provide matched red cells to chronically transfused patients, particularly those who are “immune responders” and those with sickle cell disease.58

Reactions associated with leukocytes and leukocyte antibodies

The possibility that leukocyte antibodies might cause transfusion reactions arose from the discovery more than 50 years ago of potent leukoagglutinins in the serum of patients who developed fever repeatedly after transfusions. Transfusion of the leukocyte-rich fraction of blood produced a severe febrile reaction, whereas transfusion from the same unit with less than 10% of the buffy coat caused none.59 In a confirmatory study, the minimal number of leukocytes required to produce a reaction varied from 0.25 × 109 to more than 25 × 109, and the degree of temperature elevation corresponded to the number of incompatible leukocytes transfused and the rate of transfusion.60 These early studies suggested that leukocyte-poor blood prepared for patients who have febrile reactions due to leukoagglutinins should contain fewer than 0.5 × 109 leukocytes, or approximately 10% of the number in a unit of fresh blood. Such levels were difficult to achieve consistently and economically with early centrifugal component preparation methods. After the development of efficient leukoreduction filters, most blood components in the developed world are now processed to achieve leukocyte levels that are lower by several orders of magnitude.

Transfusion reactions related to leukocyte antibodies are now recognized to include a range of signs and symptoms in addition to fever, including dyspnea, hypotension, hypertension, and rigors. As the pathophysiology of these reactions has become better understood, some puzzling aspects have been explained. Antibodies bind to the transfused leukocytes and the resulting complexes activate monocytes, which release cytokines with pyrogenic properties.61 We have come to appreciate that the frequency of febrile reactions depends on the type of blood component, its storage conditions, and a variety of factors specific to the recipient. For RBC transfusion, reported frequency ranges from less than 1% to more than 16%.62,63 In contrast to RBC, fever occurs in as many as 30% of platelet transfusions, a striking disparity that may reflect platelet-specific factors as well as the effects of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and bacterial pyrogens that accumulate in platelet concentrates during several days of storage at room temperature. A series of seminal studies indicated that pyrogens in these concentrates reside in the plasma and increase over time.64 In a large randomized study,65 only 2.2% of platelet transfusions resulted in a moderate or severe reaction, and prestorage removal of white cells by filtration significantly decreased the reaction rate. For immunized patients, HLA-matched platelets also result in lower reaction rates.

Graft-versus-host disease

Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease (TA-GVHD) occurs when immunocompetent allogeneic lymphocytes in transfused blood engraft in the recipient, proliferate, and mount an attack against the host tissues. The earliest reports of what was once considered a rare and invariably fatal disease involved fetuses receiving intrauterine exchange transfusion and children with impaired immunity such as the Wiskott-Aldridge syndrome and thymic aplasia.66,67 The clinical picture of fever, rash, diarrhea, hepatitis, lymphadenopathy, and pancytopenia drew comparison with the runt syndrome developed by newborn mice that were challenged with adult splenocyte infusion.68 Over the years, recipient risk factors have been found to include a wide range of immune defects, lymphoid malignancies, and certain solid tumors, immunosuppressive medications (most recently purine analogues such as fludarabine), and even advanced age in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.69–72 However, no cases of TA-GVHD have been reported in patients with AIDS, despite other evidence of profound immunodeficiency.73

TA-GVHD occurs between 4 and 30 days after transfusion of any cellular blood component. Whereas cases have been seen when fresh plasma was transfused, no well-documented cases have been associated with fresh-frozen plasma or cryoprecipitate. Fresh blood may predispose to lymphocyte engraftment, although “freshness” may be no more than a surrogate marker for the number of immunocompetent lymphocytes. For many years, the diagnosis was based strictly on clinical findings. Molecular diagnosis is now widely available. The histologic features, although not pathognomonic, are sufficiently typical that once the diagnosis is considered, skin biopsy proves an easy, sensitive, and relatively benign diagnostic procedure. Diagnosis can be predicted reliably by finding circulating donor lymphocytes in an afflicted patient and confirmed by detecting donor DNA in the biopsy specimen.74

TA-GVHD appears to be increasing as a result of increases in the surgical procedures, immunosuppressive therapies and transfusion strategies (blood from matched or related donors) that predispose to allogeneic cell engraftment. The risk of TA-GVHD may be reduced by leukoreduction, but this is not standard of care to prevent the disease. TA-GVHD can be eliminated only by irradiating blood components with at least 25 Gy or by chemophototherapy to inactivate donor T lymphocytes.75,76 Treatment of TA-GVHD still ranges from difficult to futile. When the full-blown syndrome occurs, mortality approaches 90%.77 Should evolving pathogen reduction technologies that disrupt nucleic acid be applied to most cellular blood components in the future, TA-GVHD may become little more than a historical footnote.

Transfusion-related acute lung injury

One severe transfusion reaction, originally termed noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, has been associated with leukocyte antibodies in donor plasma. The earliest clinical description may well have been published in Blood by National Cancer Institute investigators, although the reaction they detailed after a rapid infusion of malignant mononuclear cells does not meet the current strict definition of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI).78,79 In 1957, Brittingham first reported the classic syndrome and the ability to provoke it by injecting blood containing leukoagglutinins into a research subject.80 During the next 25 years, occasional reports appeared in the general medical literature. The entity TRALI with its characteristic clinical and radiographic findings was defined in the 1980s.81 TRALI is now the most frequent cause transfusion-related mortality reported to the FDA.49

TRALI has been estimated to occur after approximately 1 in every 5000 blood component transfusions.82 Mortality has been reported as high as 15%. A record review of recipients of blood from an implicated donor indicates that TRALI remains underdiagnosed, especially in the intensive care setting. Of 36 recipients of plasma from 1 donor whose plasma contained a neutrophil antibody that caused a fatal pulmonary reaction, 7 sustained mild to moderate and 8 sustained severe pulmonary reactions.83 Only 2 of the 8 severe reactions were reported to the hospital transfusion service, and only 2 of the 15 reactions were reported to the blood collector. We have had a similar experience.84

TRALI has been observed after transfusion of most plasma-containing blood components. The single exception appears to be pooled solvent detergent-treated plasma, in which the manufacturing process may dilute even high-titer antibodies present in any single unit. As few as 2 mL of plasma seems to be sufficient to cause respiratory distress. In most cases the responsible antibodies are found in the donor. Antibodies directed against numerous leukocyte antigens have been implicated in TRALI, including HLA antibodies, granulocyte-specific antibodies, and even monocyte-specific IgG.85 In 20% to 30% of TRALI cases, no leukocyte antibody is detected, and leukocyte antibodies may not precipitate TRALI even when the recipient expresses the cognate antigen. These puzzling findings may mean that (1) the syndrome has an alternative cause, (2) the culprit is an antibody not detected by current methods, or (3) “2 hits” are required, as has been reported in Blood.86

Several strategies have been proposed to prevent TRALI. For many years, the sole intervention was to deter blood donors associated with a case of TRALI from further donation. In the Netherlands, plasma that tests positive for HLA antibodies is discarded; few cases of TRALI have been reported since this policy was begun. Most centers in the United Kingdom and the United States now avoid transfusing plasma from female donors to reduce the chances of exposing a patient to HLA and other leukocyte antibodies that may have been elicited through pregnancy.

Summation and glimpse toward the future

Although blood transfusion will never be absolutely safe, tremendous progress has been made and promising new approaches are on the horizon. For infectious diseases, there are limits to increasing test sensitivity and resistance to adding new screening assays for every emerging agent. The optimal approach is preemptive pathogen reduction (PR). Current technologies require the addition of either psoralens or riboflavin to blood, followed by exposure to UV light.44 These methods are being applied to platelets in Europe and will compete with methylene blue and solvent detergent for treatment of plasma. They are not currently licensed in the United States. Both methods disrupt nucleic acid and fully inactivate or significantly reduce replication of all known viral, bacterial, and protozoal pathogens. The main impediment to universal usage of this technology is the ineffectiveness of light to sufficiently penetrate red blood cells. Alternatives that work independent of light activation are required and are currently being studied.44 PR techniques will likely be adopted for platelets and plasma even before a complete inactivation scheme is fully implemented.

To prevent hemolytic reactions, several advanced identification systems link donor and recipient with greater precision so as to thwart human error. In addition, rapid, automated, economical genetic typing of red cells is being developed to insure compatibility across a broader range of antigens. TA-GVHD, currently prevented by selective irradiation, will be supplanted once universal PR technology becomes available. The likelihood of TRALI from plasma or apheresis platelets can be reduced by using a preponderance of male or nulliparous female donors or by typing for leukocyte antibodies. Bacterial infections have been reduced but not eradicated by culturing apheresis-derived platelets early in storage. PR of platelets will be highly effective once introduced. In the interim, a rapid and sensitive point-of-release bacterial detection system should supplement culture techniques.

Blood transfusion has reached levels of safety that could not have been imagined a decade ago, and future innovations that are both plausible and in progress will diminish the residual risk further. Nonetheless, the relative calm could be perturbed again by an emerging pathogen with lethal potential. In addition, concerns about transfusion-related immunomodulation87 and the safety of blood that ages during prolonged storage need to be resolved.88 So, Dr Beal, we have a good but not perfect marriage, and we anticipate that continued counseling will further improve the relationship.

Biographies

As a Jewish boy growing up in New York City, it was predetermined that I would become a doctor. It was a rite of passage: bar mitzvah and then on to medical school. Although my occupational goal was established early, I never considered medicine as a path to research. My goal was always to enter clinical practice, but events small and large conspired otherwise. As a senior at Rochester Medical School and an intern at Strong Memorial Hospital, I attended the now historic Atlantic City ASCI/ACRF meetings in 1961, and over a 3-inch pastrami sandwich I decided to keep my academic options open and apply to the National Institutes of Health. However, before I was commissioned in the Public Health Service, a crisis in Berlin prompted a letter to me that began “Greetings” and contained a subway token to get me to the army base at Fort Dix, NJ. It took many frantic phone calls and, particularly, enormous support from Scott Swisher, then Chief of Hematology at Strong Memorial, to get me to NIH before my draft report date. Thus, I became a member of the “yellow berets,” a fierce cadre of draft-dodging incipient scientists who joined forces in the 1960s to protect NIH from imminent attack by Johns Hopkins. Those first years at NIH affected my life profoundly; there I met my career and my wife, one of which had permanency. I also met Richard Aster, who was just beginning his illustrious career studying platelet immunology. It was Aster who heard a lecture on protein polymorphisms by Baruch Blumberg and suggested that I see Blumberg because of the similarity of our technical approaches. I did, and we entered into a collaboration that soon led to the discovery of the Australia antigen. My first important publication was on this discovery, and my first first-author publication was the biophysical characterization of Au. I was excited to have it published in Blood. My life changed as the result of that “thin red line,” but the change was not immediate because I was still determined to enter clinical practice. Thus, I went to the University of Washington to complete my residency training, then returned to the east coast to enter a hematology fellowship under Charlie Rath at Georgetown University. At the end of my fellowship, I applied to the best group practice in Washington, DC, which rejected me in favor of a cardiologist. I do not take rejection well, but Charlie Rath consoled me by offering a faculty position at Georgetown (and a $12 000 salary). That was the turning point. After a taste of academia and hospital-based medicine, I lost my desire for private practice. Charlie Rath was the consummate physician who taught me the art of medicine as well as the principles of hematology, and I will always be indebted to him. Teaching and clinical service at Georgetown University Hospital (GUH) was all-consuming, and I had very little time for research. However, I completed a study of the interrelationships between folic acid, aspirin, and rheumatoid arthritis that was published in Blood in 1971. After 4 years at GUH, I became discouraged by the lack of dedicated research time. Just then, the relationship of Au to hepatitis was unfolding and the opportunity to return to NIH presented itself. I jumped at this chance and began the prospective studies that are described in this review. These led to the finding and clinical characterization of non-A, non-B (NANB) hepatitis and a series of studies that culminated in the near eradication of posttransfusion hepatitis. During the early NANB days, I was extremely fortunate to enter into a lifelong collaboration and friendship with Robert Purcell, who added a basic science dimension to my clinical studies. I owe much of my success to this collaboration. Together with Purcell and Steve Feinstone, we used the chimpanzee to establish the infectivity of NANB and to define many of its physical characteristics. Simultaneously, working with Jay Hoofnagel and Adrian DiBisceglie of National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, we were able to demonstrate the serious nature of chronic NANB hepatitis and its progression to cirrhosis in 20% of cases. However, despite more than a decade of intensive effort, we were unable to identify the NANB agent or its serologic markers. The molecular age and its vastly superior technology came just too late for us, and we were beaten by the brilliant blind cloning and immunoscreening approach performed by Michael Houghton and colleagues at Chiron Corp. I wrote a poem at that time about coming in second that I titled, “There's No Sense Chiron Over Spilt Milk.” Nonetheless, using our pedigreed samples, I was privileged to prove that the NANB agent and the Chiron hepatitis C agent were one and the same. This closed the final door on posttransfusion hepatitis and brought me some honors that I never imagined possible. In the final analysis, I am indebted to the Public Health Service, for offering me a home at NIH instead of Fort Dix; to an aborigine and a hemophiliac, whose plasma precipitated in agar; to serendipity; to my primary mentors, Swisher, Rath, Blumberg, and Purcell; to a long series of industrious and brilliant Fogarty Fellows; to NIH itself, for funding long-term observational studies with uncertain payoffs; and to my 3 NIH bosses, Paul Schmidt, Paul Holland, and Harvey Klein, each of whom allowed me great freedom and fought to obtain whatever was needed to keep these difficult studies going. As people now clamor for my retirement, I think I may someday accede to their wishes, but it is hard to give this up. My life just fell into the right place at the right time and after 40 years it is still rewarding and exciting. And who knows, maybe there's a non-A, non-B, non-C, non-D, non-E still lurking out there to occupy my remaining days.

I planned to become a doctor from a very early age. My earliest role model was Abraham Small, my great-uncle and family pediatrician. Uncle Abe, whose promising academic career was interrupted by the Great Depression, had studied blood cell morphology with Kenneth D. Blackfan at Boston Children's Hospital and advised me that whereas medical practice could provide great satisfaction—observing Koplick spots could predict that a sick child would develop measles—a career in research could lead to better treatments and even prevention. My early education was heavy on the arts and light on the sciences. At Boston Latin School I studied Latin, French, and German, but little chemistry and no biology. As a Harvard undergraduate, I fell under the spell of the noted classicist John H. Finley, who maintained that modern physicians (and lawyers, bankers, and politicians) desperately need grounding in the humanities. In my case he was right. I attribute my acceptance at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in part to one of Finley's famous recommendation letters. At Hopkins I discovered the intellectual attraction of internal medicine, which led to 3 years of medical residency. I was heavily influenced by Philip Tumulty, an outstanding diagnostician and humanitarian, and C. Lockard Conley, a superb clinician and scientist. I was fortunate to be accepted into Conley's hematology training program. Whereas Hopkins emphasized the preeminence of a research career, I almost certainly would have entered practice were it not for the draft and the war in Vietnam. I declined my invitation to relocate to Saigon by enrolling in the Commissioned Corps of the Public Health Service, the notorious “yellow berets.” I was assigned to the Centers for Disease Control (Venereal Disease Branch), but became one of the few to benefit from the Tuskegee Syphilis Study when, in 1972, before my entry date, the Branch leadership was disbanded. The incoming leadership, recognizing that a newly minted hematologist might not be the ideal epidemic intelligence officer, allowed me to seek employment elsewhere. Conley's recommendation landed me a position in the recently established Blood Division of the National Heart and Lung Institute as special assistant to its new director, Ernst R. Simon. Ironically, the draft ended a few days before my entry date, but I determined that 2 years in Bethesda was scarcely hardship duty and would be fair payment for my previous military exemption. Ernie Simon, who had performed some of the seminal studies on red-cell preservation, suggested that there was both opportunity and need for research in blood transfusion. In 1975 I moved to the then Clinical Center Blood Bank. For more than 30 years at NIH I have been fortunate to participate in some of the most stimulating clinical research, including the first trial of cellular gene therapy, transfusion transmission of HIV, therapeutic apheresis, and the evolution of component therapy. With the support of several Clinical Center directors I have been privileged to help develop the Department of Transfusion Medicine and to work with numerous outstanding clinical scientists, foremost of whom is Harvey J. Alter, with whom I coauthored this review.

Authorship

Contribution: H.J.A. and H.G.K. equally planned, wrote, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Harvey J. Alter, Department of Transfusion Medicine, Building 10, Room 1C711, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: halter@dtm.cc.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Blumberg BS, Alter HJ, Visnich S. A “new” antigen in leukemia sera. JAMA. 1965;191:541–546. doi: 10.1001/jama.1965.03080070025007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumberg BS, Dray S, Robinson JC. Antigen polymorphism of a low-density beta lipoprotein. Allotypy in human serum. Nature. 1962;194:656–658. doi: 10.1038/194656a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutnick AI, London WT, Gerstley BJS, Cronlund MM, Blumberg BS. Anicteric hepatitis associated with Australia antigen: occurrence in patients with Down's syndrome. JAMA. 1968;205:670–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.London WT, Sutnick AI, Blumberg BS. Australia antigen and acute viral hepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1969;70:55–59. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-70-1-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prince AM, Hargrove RL, Szmuness W, Cherubin CE, Fontana VJ, Jeffries MB. Immunologic distinction between infectious and serum hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1970;282:987–991. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197004302821801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh JH, Purcell RH, Morrow AG, Chanock RM, Schmidt Post-transfusion hepatitis after open heart operations: incidence after the administration of blood from commercial and volunteer donor populations. JAMA. 1970;211:261–265. doi: 10.1001/jama.211.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alter HJ, Holland PV, Purcell RH, et al. Postransfusion hepatitis after exclusion of the commercial and hepatitis B antigen positive donor. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:691–699. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-5-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feinstone SM, Kapikian AZ, Purcell RH. Hepatitis A detection by immune electron microscopy of a virus-like antigen associated with acute illness. Science. 1973;182:1026–1028. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feinstone SM, Kapikian AZ, Purcell RH, Alter HJ, Holland PV. Transfusion-associated hepatitis not due to viral hepatitis type A or B. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:767–770. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197504102921502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alter HJ, Purcell RH, Holland PV, Popper H. Transmissible agent in “non-A, non-B” hepatitis. Lancet. 1978;1:459–463. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tabor E, Gerety RJ, Drucker JA, et al. Transmission of non-A, non-B hepatitis from man to chimpanzee. Lancet. 1978;1:463–465. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feinstone JM, Mihalik KB, Kamimura J, Alter HJ, London WT, Purcell RH. Inactivation of hepatitis B virus and non-A, non-B virus by chloroform. Infect Immun. 1983;4:816–821. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.816-821.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He L-F, Alling DW, Popkin TJ, Shapiro M, Alter HJ, Purcell RH. Determining the size of non-A, non-B hepatitis virus by filtration. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:636–640. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley DW, McCaustland KA, Cook EH, Schable CA, Ebert JM, Maynard JE. Posttransfusion non-A, non-B hepatitis in chimpanzees. Physicochemical evidence that the tubule forming agent is a small enveloped virus. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:773–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berman MD, Alter HJ, Ishak KG, Purcell RH, Jones EA. The chronic sequelae of non-A, non-B hepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:1–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alter HJ, Purcell RH, Holland PV, Alling DW, Koziol DE. The relationship of donor transaminase (ALT) to recipient hepatitis: Impact on blood transfusion services. JAMA. 1981;246:630–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koziol DE, Holland PV, Alling DW, et al. Antibody to hepatitis B core antigen as a paradoxical marker for non-A, non-B hepatitis agents in donated blood. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:488–495. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-4-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alter HJ, Purcell RH, Shih JW, et al. Detection of antibody to hepatitis C virus in prospectively followed transfusion recipients with acute and chronic non-A, non-B hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1494–1500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911303212202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control. Pneumocystis pneumonia – Los Angeles. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1981;30:250–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control. Update on Kaposi's sarcoma and opportunistic infections in previously healthy persons – United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982;31:294–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia among persons with hemophilia A. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982;31:365–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ammann AJ, Cowan MJ, Wara DW, et al. Acquired immunodeficiency in an infant: possible transmission by means of blood products. Lancet. 1983;1:956–958. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterman TA, Lui K-J, Lawrence DN, Allen JR. Estimating the risks of transfusion-associated acquired immune deficiency syndrome and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Transfusion. 1987;27:371–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1987.27587320525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen JR. Transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) by blood and blood components. In: Moore SB, editor. Transfusion-Transmitted Viral Diseases. Arlington, VA: American Association of Blood Banks; 1987. pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jason J, McDougal JS, Holman RC, et al. Human T-lymphotropic retrovirus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus antibody:association with hemophiliac's immune status and blood component usage. JAMA. 1985;252:3409–3415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barre-Sinoussi F, Chermann JC, Rey F, et al. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science. 1983;220:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.6189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallo RC, Salahuddin SZ, Popovic M, et al. Frequent detection and isolation of a cytopathic retroviris (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and at risk for AIDS. Science. 1984;224:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.6200936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoto MA. The precautionary principle and emerging biologic risks: lessons from human immunodeficiency virus in blood products. Semin Hematol. 2006;43(2) suppl 3:S10–S12. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mostashari F, Bunnin ML, Kitsutani PT, et al. Epidemic West Nile encephalitis, New York, 1999: Results of a household-based seroepidemiologic survey. Lancet. 2001;358:261–264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwamoto M, Jernigan DB, Guasch A, et al. Transmission of west Nile virus from an organ donor to four transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2196–2203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pealer LN, Marfin AA, Petersen LR, et al. Transmission of west Nile virus through blood transfusion in the United States in 2002. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1236–1245. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stramer SL, Fang CT, Foster GA, Wagner AG, Brodsky JP, Dodd RY. West Nile virus among blood donors in the United States, 2003 and 2004. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:451–459. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alter HJ, Stramer SL, Dodd RY. Emerging infectious diseases that threaten the blood supply. Semin Hematol. 2007;44:32–41. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown P. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: reflections on risk from blood product therapy. Haemophilia. 2007;13(suppl. 5):32–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou S, Fang CT, Schonberger LB. Transfusion transmission of human prion diseases. Transfus Med Rev. 2008;22:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kilduffe RA, DeBakey M. St Louis. MO: Mosby; 1942. The blood bank and the techniques and therapeutics of transfusion. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chambers RW, Foley HT, Schmidt PJ. Transmission of syphilis by fresh blood components. Transfusion. 1969;9:32–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.1969.tb04909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pittman M. A study of bacteria implicated in transfusion reactions and of bacteria isolated from blood products. J Lab Clin Med. 1953;42:273–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuehnert MJ, Roth VR, Haley NR, et al. Transfusion-transmitted bacterial infection in the United States, 1998 through 2000. Transfusion. 2001;41:1493–1499. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41121493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yomtovian RA, Palavecino EL, Dysktra AH, et al. Evolution of surveillance methods for detection of bacterial contamination of platelets in a university hospital, 1991 through 2004. Transfusion. 2006;46:719–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ness P, Braine H, King K, et al. Single-donor platelets reduce the risk of septic platelet transfusion reactions. Transfusion. 2001;41:857–861. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41070857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eder AF, Kennedy JM, Dy BA, et al. Bacterial screening of apheresis platelets and the residual risk of septic transfusion reactions: the American Red Cross experience (2004-2006). Transfusion. 2007;47:1134–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bryant BJ, Klein HG. Pathogen inactivation: the definitive safeguard for the blood supply. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:719–733. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-719-PITDSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blundell J. Experiments on the transfusion of blood by the syringe. Med-Chir Trans. 1818;9:56. doi: 10.1177/09595287180090p107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ottenberg R, Kaliski DJ. Accidents in transfusion. Their prevention by preliminary blood examination: based on experience of one hundred and twenty-eight transfusions. JAMA. 1913;61:2138. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiener AS, Maloney WC. Hemolytic transfusion reactions. IV. Differential diagnosis: “dangerous universal donor” or intragroup incompatibility. Am J Clin Pathol. 1943;13:74. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Linden JV, Wagner K, Voytovich AE, Sheehan J. Transfusion errors in New York State: an analysis of 10 years' experience. Transfusion. 2000;40:1207–1213. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40101207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration; 2008. Fatalities reported to FDA following blood collection and transfusion: annual summary for fiscal years 2005 and 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dzik WH, Murphy MF, Andreu G, et al. An international study of the performance of sample collection from patients. Vox Sang. 2003;85:40–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.2003.00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Larsson LG, Welsh VJ, Ladd DJ. Acute intravascular hemolysis secondary to out-of-group platelet transfusion. Transfusion. 2000;40:902–906. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40080902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaines AR. Acute onset hemoglobinemia and/or hemoglobinuria and sequelae following Rh(o)(D) immune globulin intravenous administration in immune thrombocytopenic purpura patients. Blood. 2000;95:2523–2529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Talano JA, Hillery CA, Gottschall JL, Baylerian DM, Scott JP. Delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction/hyperhemolysis syndrome in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics. 2003;111:661–665. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.e661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lostumbo MM, Holland PV, Schmidt PJ. Isoimmunization after multiple transfusions. N Engl J Med. 1966;275:141–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196607212750305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pineda AA, Brzica SM, Jr, Taswell HF. Hemolytic transfusion reaction: recent experience in a large blood bank. Mayo Clin Proc. 1978;53:378–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Diamond WJ, Brown FL, Jr, Bitterman P, et al. Delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction presenting as sickle-cell crisis. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:231–234. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-2-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pineda AA, Vamvakas EC, Gorden LD, Winters JL, Moore SB. Trends in the incidence of delayed hemolytic and delayed serologic transfusion reactions. Transfusion. 1999;39:1097–1103. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39101097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosse WF, Gallagher D, Kinney TR, et al. Transfusion and alloimmunization in sickle cell disease: The Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 1990;76:1431–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brittingham TE, Chaplin H., Jr Febrile transfusion reactions caused by sensitivity to donor leukocytes and platelets. JAMA. 1957;165:819–825. doi: 10.1001/jama.1957.02980250053013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perkins HA, Payne R, Ferguson J, Wood M. Nonhemolytic febrile transfusion reactions. Quantitative effects of blood components with emphasis on isoantigenic incompatibility of leukocytes. Vox Sang. 1966;11:578–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1966.tb04256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dzik WH. Is the febrile response to transfusion due to donor or recipient cytokine? Transfusion. 1992;32:594. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1992.32692367210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Menitove JE, McElligott MC, Aster RH. Febrile transfusion reaction: what blood component should be given next? Vox Sang. 1982;42:318–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1982.tb01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lane TA, Gernsheimer T, Mohandas K, Assmann SF. Signs and symptoms associated with the transfusion of WBC-reduced RBCs and non-WBC-reduced RBCs in patients with anemia and HIV infection: results from the Viral Activation Transfusion Study. Transfusion. 2002;42:265–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heddle NM, Klama L, Meyer R, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing plasma removal with white cell reduction to prevent reactions to platelets. Transfusion. 1999;39:231–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39399219278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Enright H, Davis K, Gernsheimer T, et al. Factors influencing moderate to severe reactions to PLT transfusions: experience of the TRAP multicenter clinical trial. Transfusion. 2003;43:1545–1552. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seemayer TA, Bolande RP. Thymic involution mimicking thymic dysplasia: a consequence of transfusion-induced graft versus host disease in a premature infant. Arch. Pathol Lab Med. 1980;104:141–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ohto H, Anderson KC. Posttransfusion graft-versus-host disease in Japanese newborns. Transfusion. 1996;36:117–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.36296181922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hathaway WE, Githens JH, Blackburn WR, Fulginiti V, Kempe CH. Aplastic anemia, histiocytosis and erythrodermia in immunologically deficient children:. probable human runt disease. N Engl J Med. 1965;273:953–958. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196510282731803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leitman SF, Tisdale JF, Bolan CD, et al. Transfusion-associated GVHD after fludarabine therapy in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Transfusion. 2003;43:1667–1671. doi: 10.1046/j.0041-1132.2003.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ohto H, Anderson KC. Survey of transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease in immunocompetent recipients. Transfus Med Rev. 1996;10:31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(96)80121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maung ZT, Wood AC, Jackson GH, et al. Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease in fludarabine-treated B-chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1994;88:649–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb05093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klein HG. Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease: less fresh blood and more gray (Gy) for an aging population. Transfusion. 2006;46:878–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ammann AJ. Hypothesis: absence of graft-versus-host disease in AIDS is a consequence of HIV-1 infection of CD4+ T cells. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:1224–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang L, Juji T, Tokunaga K, et al. Brief report: polymorphic microsatellite markers for the diagnosis of graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:398–401. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402103300605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grass JA, Wafa T, Reames A, et al. Prevention of transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease by photochemical treatment. Blood. 1999;93:3140–3147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pelszynski MM, Moroff G, Luban NL, Taylor BJ, Quinones RR. Effect of gamma irradiation of red blood cell units on T-cell inactivation as assessed by limiting dilution analysis: implications for preventing transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1994;83:1683–1689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anderson KC, Weinstein HJ. Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:315–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199008023230506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lanman JT, Bierman HR, Byron RL., Jr Transfusion of leukemic leukocytes in man; hematologic and physiologic changes. Blood. 1950;5:1099–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Toy P, Popovsky MA, Abraham E, et al. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: definition and review. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:721–726. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000159849.94750.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brittingham TE. Immunologic studies on leukocytes. Vox Sang. 1957;2:242–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1957.tb03699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Popovsky MA, Moore SB. Diagnostic and pathogenetic considerations in transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfusion. 1985;25:573–577. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1985.25686071434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ward HN. Pulmonary infiltrates associated with leukoagglutinin transfusion reactions. Ann Intern Med. 1970;73:689–694. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-73-5-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kopko PM, Marshall CS, MacKenzie MR, Holland PV, Popovsky MA. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: report of a clinical look-back investigation. JAMA. 2002;287:1968–1971. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.15.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fadeyi EA, De Los Angeles MM, Wayne AS, et al. The transfusion of neutrophil-specific antibodies causes leukopenia and a broad spectrum of pulmonary reactions. Transfusion. 2007;47:545–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dooren MC, Ouwehand WH, Verhoeven AJ, von dem Borne AE, Kuijpers RW. Adult respiratory distress syndrome after experimental intravenous gamma-globulin concentrate and monocyte-reactive IgG antibodies. Lancet. 1998;352:1601–1602. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)61049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Silliman CC, Curtis BR, Kopko PM, et al. Donor antibodies to HNA-3a implicated in TRALI reactions prime neutrophils and cause PMN-mediated damage to human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells in a two-event in vitro model. Blood. 2007;109:1752–1755. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Klein HG. The immunomodulatory effects of blood transfusion. Tumori. 2001;87:S17–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DL, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1229–1239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]