A decision aid to support informed choices about bowel cancer screening among adults with low education: randomised controlled trial (original) (raw)

Abstract

Objective To determine whether a decision aid designed for adults with low education and literacy can support informed choice and involvement in decisions about screening for bowel cancer.

Design Randomised controlled trial.

Setting Areas in New South Wales, Australia identified as socioeconomically disadvantaged (low education attainment, high unemployment, and unskilled occupations).

Participants 572 adults aged between 55 and 64 with low educational attainment, eligible for bowel cancer screening.

Intervention Patient decision aid comprising a paper based interactive booklet (with and without a question prompt list) and a DVD, presenting quantitative risk information on the possible outcomes of screening using faecal occult blood testing compared with no testing. The control group received standard information developed for the Australian national bowel screening programme. All materials and a faecal occult blood test kit were posted directly to people’s homes.

Main outcome measures Informed choice (adequate knowledge and consistency between attitudes and screening behaviour) and preferences for involvement in screening decisions.

Results Participants who received the decision aid showed higher levels of knowledge than the controls; the mean score (maximum score 12) for the decision aid group was 6.50 (95% confidence interval 6.15 to 6.84) and for the control group was 4.10 (3.85 to 4.36; P<0.001). Attitudes towards screening were less positive in the decision aid group, with 51% of the participants expressing favourable attitudes compared with 65% of participants in the control group (14% difference, 95% confidence interval 5% to 23%; P=0.002). The participation rate for screening was reduced in the decision aid group: completion of faecal occult blood testing was 59% v 75% in the control group (16% difference, 8% to 24%; P=0.001). The decision aid increased the proportion of participants who made an informed choice, from 12% in the control group to 34% in the decision aid group (22% difference, 15% to 29%; P<0.001). More participants in the decision aid group had no decisional conflict about the screening decision compared with the controls (51% v 38%; P=0.02). The groups did not differ for general anxiety or worry about bowel cancer.

Conclusions Tailored decision support information can be effective in supporting informed choices and greater involvement in decisions about faecal occult blood testing among adults with low levels of education, without increasing anxiety or worry about developing bowel cancer. Using a decision aid to make an informed choice may, however, lead to lower uptake of screening.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00765869 and Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry 12608000011381.

Introduction

Engaging patients in decisions about their health care is promoted by leading health organisations,1 2 3 with growing importance placed on providing patients with the best available evidence and encouraging them to express their preferences in the decision making process.4 5 This has led to a demand for tools to facilitate patients’ involvement in decision making about their health care. Patient decision aids are interventions designed to help people make informed decisions about their health by providing information on the options and possible outcomes relevant to their own health. Typically decision aids contain numerical and graphical risk information about the possible outcomes of each choice, and exercises to help people arrive at decisions that reflect their personal values and preferences.6 Cochrane reviews suggest that, compared with usual care, decision aids improve knowledge about clinical options, create more realistic expectations about outcomes, and increase active involvement in the decision making process.7

However, despite a substantial increase in the availability of decision aids (over 270 are currently listed on the Cochrane decision aid registry at www.decisionaid.ca/AZlist.html), few attempts have been made to evaluate their effectiveness with socioeconomically disadvantaged populations and those with low literacy. These groups may be in greatest need of information to support their understanding and involvement in decision making, as limited literacy is adversely associated with a range of health related outcomes. These include poor knowledge about disease and methods of early disease prevention, high rates of emergency admission to hospital, poor self care management of chronic conditions, and low satisfaction with doctor-patient communication.8

We tested the effectiveness of a decision aid in facilitating understanding, involvement, and informed choice about participation in screening for bowel cancer among a sample of participants with low education. Current guidelines from the UK General Medical Council state clearly that the decision to screen for cancer should be based on an informed choice, in which people are given clear and balanced information about the benefits and harms of screening (including the option of no screening).9 10 Despite this, concern remains about informed choice in screening, centring on the conflict between two ethical principles: autonomy and utilitarianism. The first principle concerns respecting patient autonomy and agency, whereby people are free to choose whether or not they undergo screening and are provided with information (on the harms as well as the benefits) to make an informed choice. The second principle, utilitarianism, views participation in screening as being in the public interest, and high rates of uptake are seen as paramount for improving population health. However, a strong case has been made for greater honesty about the harms of screening and for potential participants of screening programmes to be given the opportunity to make an informed choice.11 12

In the United Kingdom, Australia, and several European countries, faecal occult blood testing is currently offered through national government funded programmes, with test kits posted directly to people’s homes.13 Compared with other national screening programmes (for example, screening for breast and cervical cancer), the actual test and the decision to participate are usually done at home, with minimal interaction with a healthcare provider, and supported mainly by written information.

We evaluated a decision aid for screening using faecal occult blood testing developed for groups with low education and literacy. Our primary interest was whether the decision aid could support informed choice and increase involvement in decisions about screening among a community sample with low education. We further evaluated whether a question prompt list—a structured list of questions about the benefits and harms of bowel cancer screening that people may want to ask their doctor—in addition to a decision aid, enhanced decision making. Systematic reviews have shown that question prompt lists may empower patients to ask questions, but they have not been tested in a sample of people with low education.14

Methods

We carried out a randomised trial comprising three arms, with participants randomised to either a decision aid booklet with accompanying DVD, a decision aid and DVD along with a question prompt list, or a standard consumer information booklet, developed as part of the Australian national bowel cancer screening programme (control group). All participants received a faecal occult blood test kit for self sampling.

Participants and recruitment

Potential participants were randomly drawn from the New South Wales electoral register, using the Australian Bureau of Statistics SEIFA (Socio-Economic Index for Area) codes to target areas identified as socioeconomically disadvantaged (low educational attainment, high unemployment, and unskilled occupations).15 The Australian Electoral Commission randomly extracted a total of 8400 records from the register. A database containing names and phone numbers was then provided to Hunter Valley Research Foundation, which administered the recruitment and follow-up interview surveys using a computer assisted telephone interviewing system. The foundation is an independent non-profit organisation, experienced in running community surveys and recruiting participants into health and social research studies. It is listed by the New South Wales Department of Health as an approved provider of research services, and regularly carries out telephone and face to face surveys for State and Commonwealth health departments and academic institutions. Its interviewers are routinely trained to ensure bias is not introduced into their interviews. In the current study interviewers followed a standardised interview script and their performance was monitored as part of standard quality assurance processes by Hunter Valley Research Foundation. The Foundation randomly selected potential respondents from the database and contacted them by telephone to determine their eligibility and to invite them to take part in the study.

Men and women were eligible for the trial if they were aged 55-64 (selected to match the target age group for the national programme), spoke mainly English at home, had an average or slightly above average risk of bowel cancer (family history risk, category 1 under existing guidelines),16 and had a low educational attainment—that is, no formal educational qualifications, intermediate school certificate (awarded for completion of four years of high school or secondary school), or trade certificate (roughly equivalent to UK adults with a national vocational qualification or an apprenticeship). The selection of these specific educational qualifications as eligibility criteria was based on the results from the Australian Bureau of Statistics adult literacy and life skills survey.17 This national survey of adult literacy indicated these specific levels of education were more likely to achieve lower literacy scores for the prose and document literacy scales compared with adults of higher education.

We excluded people if they had a personal or strong family history of bowel cancer, had completed a bowel cancer screening test or examination (including faecal occult blood testing, flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy) in the past two years, or had already been invited to participate in the national programme or any other bowel cancer screening scheme.

Once eligibility was confirmed, we administered a baseline telephone questionnaire to record personal characteristics, self reported health status, and self reported functional health literacy, and to measure knowledge of and interest in screening using faecal occult blood testing. Participants who verbally consented to take part were then randomised to one of the three groups using random permuted blocks of size 6 and 9 for each sex stratum. A statistician (JMS) who had no contact with participants generated this randomisation list. Interviewers responsible for recruiting participants were not aware of the randomisation sequence or allocation and therefore did not know which intervention respondents would receive. On completion of the baseline interview, the appropriate intervention (decision aids or government screening booklet) and corresponding study materials (faecal occult blood test kit and instructions) were posted to participants. Participants were recruited between July and November 2008.

Interventions

Decision aid groups

Participants in the two decision aid groups received a paper based booklet and DVD (with or without a question prompt list) that had been specifically designed for adults with low education and literacy skills. To develop a decision aid that was more sensitive to the needs of adults with low literacy, principles of plain language and basic design were applied, together with simple techniques to reduce cognitive effort for the reader.18 19 Such strategies included reducing the amount of text, replacing technical language with lay language, creating a glossary of medical terms that were highlighted throughout the text, simplifying medical diagrams, using the active voice for communication, and providing contextual information before factual information. Illustrations were also integrated into the revised decision aid, based on research suggesting that combining well designed pictures with text enhances attention, recall, and understanding among groups with lower literacy.20 A combination of cartoon-style images and anatomical diagrams of the bowel were incorporated. A detailed description of the development of the decision aid has been published.21 22

The tool was designed to comply with the International Patient Decision Aid Standard23 and presented tailored risk information for different sex and family history groups about the cumulative outcomes of biennial screening with faecal occult blood testing. This included mortality from bowel cancer (with and without screening), the risk of false positives and false negatives, interval cancers, removal of polyps detected by colonoscopy, and bowel cancer detected by screening. A full version of the decision aids aimed at the different sexes can be found at http://sydney.edu.au/medicine/public-health/step/publications/decisionaids.php. The chance of each outcome was expressed as an event rate per 1000 men or 1000 women screened every two years over 10 years, using diagrams with ovals to represent a population of 1000 (see web extra appendix 1). One member of the research team (LT) calculated the probabilities of these outcomes from Australian national data (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the Cancer Council of Australia) to reflect the best available evidence at the time.24 The aid also contained an interactive exercise for the reader to identify their risk of bowel cancer (based on their family history) and a personal worksheet to help them clarify their values (see web extra appendix 2). The content, design, and layout of the tool was informed by in-depth qualitative interviews with adults of varying levels of education and literacy skill. We also consulted an expert panel comprising experts in bowel cancer screening, general practitioners, experts in adult literacy, and linguists.

Control group

Participants in the control group received the consumer information booklet developed for people invited to take part in the Australian national bowel cancer screening programme. This booklet contained written and numerical information about bowel cancer and screening for bowel cancer. A bar chart was used to present data on the most common causes of cancer related deaths for men and women in Australia, and a relative risk statement (“If you do a FOBT [faecal occult blood test] every two years, you can reduce your risk of dying from bowel cancer by up to one third”) was used to state the efficacy of faecal occult blood testing. Table 1 compares the key content and design features of the booklets.

Table 1.

Comparison between decision aid and government booklet

| Component/feature | Decision aid booklet | Government booklet |

|---|---|---|

| General description | Paper based, interactive (33 page) booklet (and accompanying DVD) containing written and quantitative information about bowel cancer and bowel cancer screening. Flesch-Kincaid readability score=grade 7 | Paper based, 20 page booklet with written and quantitative information about bowel cancer and bowel cancer screening. Flesch-Kincaid readability score=grade 9 |

| Visual aspects | Use of simplified text and bullet points. Glossary of medical terms. Visual illustrations and cues. Medical diagram of bowel | Use of plain language. Large amounts of text on each page. Photographs of adults within target age range. Medical diagram of digestive system |

| Key factual content | Purpose of cancer screening—that is, to detect bowel cancer at an early stage. Bowel cancer and its risk factors. Risk of bowel cancer based on family history. Faecal occult blood testing procedure. Colonoscopy procedure as follow-up investigation and associated risks | Purpose of cancer screening—that is, to detect bowel cancer at an early stage. Bowel cancer and its risk factors. Faecal occult blood testing procedure. Colonoscopy procedure as follow-up investigation and associated risks |

| Use of tailored information | Tailored risk information for age, sex, and family history groups about cumulative outcomes of biennial screening using faecal occult blood testing | None |

| Presentation of quantitative information | Systematic 1000 oval diagrams (see web extra appendix 1) using natural frequencies, time frames, and consistent denominators used to convey: absolute risk reduction in mortality from bowel cancer with (and without) biennial screening using faecal occult blood testing over 10 years; and probability of cumulative outcomes of screening using faecal occult blood testing (including risk of false positives, false negatives, interval cancers, removal of polyps detected by colonoscopy, and detection of bowel cancer) | Bar chart displaying prevalence of mortality from bowel cancer in Australia for men and women, comparison with other types of cancers. Relative risk reduction statement about the efficacy of faecal occult blood testing: “[FOBT] can reduce your risk of dying from bowel cancer by up to one third” |

| Values clarification exercise | Interactive personal worksheet tailored for sex and family history groups (see web extra appendix 2) | None |

Outcome measures

Two weeks after the package had been posted to participants they were telephoned to complete a follow-up interview. It was not possible for the interviewers to be blinded to the group allocation. However, all questions used standardised wording with pre-coded responses and were asked within a supervised environment, where interviewer performance was regularly monitored to ensure scripts were read as written. Before the main trial a pilot study was carried out with 36 respondents. Participants were recruited using the same procedures described for the main trial, with the objective of testing this recruitment strategy and examining the wording and suitability of the baseline and follow-up telephone interview surveys.

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcomes were informed choice and preferences for involvement in the screening decision.

Informed choice

Informed choice was assessed using the multidimensional model of informed choice, a measure that has been developed and validated in the context of antenatal screening for Down’s syndrome.25 26 In the current study we applied this measure to assess the extent to which people made an informed choice about participating in screening using faecal occult blood testing. To determine whether a participant had made an informed (or uninformed) choice about such screening, we individually assessed, and then combined, three constructs: knowledge about the possible outcomes of screening, attitudes towards doing the screening test, and screening behaviour. Participants were grouped into one of eight classifications according to their knowledge about the outcomes of faecal occult blood testing (adequate v inadequate), attitudes (positive v negative), screening behaviour (completed the screening test v did not complete the screening test). Participants were considered to have made an informed choice to complete the screening test if they had adequate knowledge and positive attitudes towards the test. An informed choice to decline the screening test occurred when a participant had a negative attitude towards the test, had adequate knowledge about the outcomes, and did not complete the test. We considered participants who had inadequate knowledge or their attitudes did not reflect their actual screening behaviour to have made an uninformed choice about screening. This method of classification is consistent with that applied by the researchers in the original use of this measurement instrument.25 26

Knowledge

Development of the knowledge measure was informed by the UK General Medical Council guidelines relating to screening, which recommend that people should be aware of the potential for screening to prevent death from bowel cancer, but also understand the potential risks (including the possibility of false positive and false negative results).9 We assessed participants’ conceptual knowledge to examine whether they understood the underlying concept (for example, of experiencing a false positive result as an outcome of screening), and numerical knowledge to determine whether they were aware of the approximate numbers of people affected (for example, the likelihood of experiencing a false positive result). Questions to assess knowledge were asked using simple, jargon-free language and were piloted with participants with low educational attainment before the main trial. The knowledge measure uses a similar approach to assessing knowledge as used in previous research on screening decision aids by our group.27 The aim of this measure was to assess both gist (conceptual) and detailed numerical (verbatim) understanding of the decision, both of which are required to gain an overall understanding to inform decision making. The measure assessed understanding of five core concepts relating to bowel cancer screening. These concepts were that the number of asymptomatic men and women who die from bowel cancer over the next 10 years is relatively small; deaths from bowel cancer are reduced by screening, but the absolute reduction in deaths attributable to screening is small (a few per 1000 screened over 10 years); bowel cancer screening may lead to false positive results; the number of men and women who experience a false positive result is relatively large (a few hundred out of 1000 screened over 10 years) compared with the number of lives saved by screening; and bowel cancer screening sometimes misses cancers.

We developed a marking scheme using an approach similar to that of previous researchers.27 It provided a maximum score of 12 (4 marks for conceptual understanding and 8 for numerical knowledge; see web extra appendix 3). We decided a priori that a pass mark of 50% or above (score ≥6 out of 12) would be considered as informed. The outcome was dichotomised to classify those with “adequate” and those with “inadequate” knowledge for the informed choice measure.

Screening attitudes and behaviour

Attitudes towards completing the faecal occult blood test were measured using a six item scale (with response categories adapted from seven to five categories).25 Scores ranged from 6 to 30, with higher scores denoting more positive attitudes towards doing the test. The median value of the sample was used to classify participants’ attitudes as positive or negative.

We assessed screening behaviour (completed test v did not complete the test) three months post-intervention from test completion records supplied by the laboratory. The Australian government’s report on its national bowel cancer screening programme showed that most people complete the test within three months of the first invitation.13

Involvement preferences in screening decision

We used the control preferences scale to determine the part that participants played or wanted to play in their decision about screening. This scale requires people to choose from one of five statements that best describes how they (and their doctors) participated in the decision making process.28

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes were decisional conflict (10 item low literacy version of the decisional conflict scale29), decision satisfaction (10 item decision attitude scale30), confidence in decision making (three items adapted from the decision self efficacy scale31), general anxiety (state trait anxiety inventory32), interest in screening, worry about developing bowel cancer,33 and acceptability of materials.34

Sample size

One of the primary outcomes of this study was knowledge about the outcomes of screening using faecal occult blood testing. To estimate the required sample size for the current trial we used results from a previous general practice based trial on a decision aid for screening using faecal occult blood testing.24 Knowledge scores in the general practice based trial were normally distributed, with a mean of 2.72 (range −3 to 10) and standard deviation of 2.35. We calculated that to detect an improvement of 1 (that is, one extra knowledge question answered correctly), with 90% power at the 1% significance level, required 165 participants in each group. Allowing for 10% loss to follow-up after randomisation, we aimed to recruit a total of 185 participants in each group (555 in total).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were by intention to treat and carried out blinded to intervention. We used a paired sample t test and Wilcoxon signed rank test to assess differences in knowledge scores and decision making preferences, respectively, within each group (pre-intervention v post-intervention). Post-intervention comparisons between the decision aid and control groups were done using the independent sample t test for continuous variables, χ2 test for categorical variables, and non-parametric Mann-Whitney test for ordinal variables. We used the χ2 test to compare between the groups the proportion of people classified as making an informed choice about screening. To examine the relation between risk of bowel cancer (based on family history) and screening behaviour, we used the Mantel-Haenszel test. All reported P values are two sided, with P<0.05 considered as significant. Analyses were carried out using SPSS version 17.0.

Results

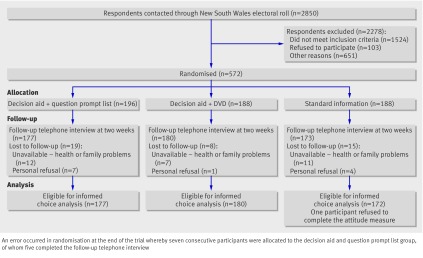

Of the 2850 potential participants contacted, 675 were eligible, of whom 572 (85%) consented to participate and were randomised and interviewed at baseline. Of these, 42 did not complete the follow-up telephone interview because they either no longer wanted to participate in the study (n=12) or were unavailable because of family and other health concerns (n=30), leaving a total of 530 (figure).

Flow of participants through trial

Baseline characteristics

Intervention and control groups had similar baseline characteristics (table 2). Overall, 11% of participants (62/572) reported a family history of bowel cancer and 70% (402/572) were interested in doing the screening test. Participants’ conceptual understanding of the faecal occult blood test (at baseline) was similar across all three groups. Those lost to follow-up had significantly poorer self reported health at baseline, which corresponded with their reasons for not completing the follow-up interview.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants (n=572) allocated to decision aid intervention (with and without question prompt list) and standard information (control group)

| Characteristics | No (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision aid+question prompt list (n=196) | Decision aid+DVD (n=188) | Standard information (n=188) | |

| Women | 97 (50) | 93 (50) | 94 (50) |

| Men | 99 (51) | 95 (51) | 94 (50) |

| Education: | |||

| No formal qualifications | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 6 (3) |

| Intermediate school certificate* | 132 (67) | 129 (69) | 131 (70) |

| Technical or trade certificate† | 64 (33) | 59 (31) | 57 (30) |

| Years in full time education: | |||

| 0-10 | 116 (59) | 106 (56) | 107 (57) |

| 11-20 | 78 (40) | 81 (43) | 79 (42) |

| Country of birth: | |||

| Australia or New Zealand | 177 (90) | 162 (86) | 158 (84) |

| United Kingdom | 11 (6) | 16 (9) | 9 (5) |

| Other | 8 (4) | 10 (5) | 21 (11) |

| Difficulties understanding written health information: | |||

| Never | 64 (33) | 62 (33) | 56 (30) |

| Occasionally or sometimes | 102 (52) | 113 (60) | 118 (63) |

| Often or always | 29 (15) | 11 (6) | 12 (6) |

| Confidence filling in medical forms: | |||

| None | 38 (19) | 35 (19) | 24 (13) |

| Some or quite a bit | 108 (55) | 99 (53) | 114 (61) |

| Very | 50 (26) | 54 (29) | 49 (26) |

| Help with reading hospital forms: | |||

| Never | 103 (53) | 100 (53) | 115 (61) |

| Occasionally or sometimes | 57 (29) | 56 (30) | 44 (23) |

| Often or always | 23 (12) | 14 (7) | 15 (8) |

| Not applicable | 13 (7) | 18 (10) | 14 (7) |

| Self reported health: | |||

| Excellent or very good | 98 (50) | 80 (43) | 93 (50) |

| Good | 71 (36) | 69 (37) | 54 (29) |

| Fair or poor | 35 (18) | 39 (21) | 41 (22) |

| Family history of bowel cancer: | |||

| Yes | 25 (13) | 16 (9) | 21 (11) |

| No | 167 (85) | 167 (89) | 164 (87) |

| Worry about developing bowel cancer: | |||

| None or a bit | 170 (91) | 184 (94) | 172 (92) |

| Quite or very | 17 (9) | 11 (6) | 16 (9) |

| Interest in screening using faecal occult blood test: | |||

| Very or fairly | 136 (69) | 135 (72) | 131 (70) |

| A bit or not very | 57 (29) | 49 (26) | 51 (27) |

| Preferences for involvement in screening decision: | |||

| Patient decides alone | 68 (35) | 75 (40) | 78 (41) |

| Patient decides after consulting | 41 (21) | 28 (15) | 39 (21) |

| Share decision equally | 72 (37) | 70 (37) | 54 (29) |

| Doctor decides after consulting or alone | 13 (7) | 14 (8) | 21 (7) |

| Knowledge scores (maximum 4)‡: | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.37 (1.62) | 2.32 (1.53) | 2.23 (1.64) |

Primary analyses

As the two decision aid groups (with and without question prompt list) did not differ significantly, the two groups were combined and compared with the control group.

Knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviour

Conceptual knowledge improved significantly in both groups before and after the intervention, with a mean increase of 1.20 in the decision aid groups and 1.26 in the control group (P<0.001). The proportion of participants with adequate total knowledge (score ≥6 out of 12 on the full knowledge scale), however, was higher in the decision aid groups than in the control group (56% (200/357) v 19% (33/173); P<0.001). In particular, the decision aid increased participants’ numerical understanding of their baseline risk of bowel cancer and the absolute reduction in deaths attributable to screening: the mean scores (maximum score 8) were 2.93 for the decision aid groups and 0.58 for the control group, an increase of 2.36 (P<0.001; table 3).

Table 3.

Primary outcomes for decision aid intervention groups combined and standard information (control) group. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome* | Decision aid groups combined (n=357) | Standard information group (n=173) | Difference (decision aid−control) (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge scores (mean, SD)†: | ||||

| Concept (maximum score 4) | 3.57 (1.0) | 3.53 (0.96) | 0.04 (−0.14 to 0.22) | 0.64 |

| Numerical (maximum score 8) | 2.93 (2.91) | 0.58 (1.28) | 2.35 (1.89 to 2.80) | <0.001 |

| Total knowledge score (maximum score 12) | 6.50 (3.34) | 4.10 (1.71) | 2.39 (1.86 to 2.92) | <0.001 |

| Adequate knowledge (total score ≥50%) | 200 (56) | 32 (19) | 37.5 (30.0 to 45.0) | <0.001 |

| Attitudes‡: | ||||

| Mean (SD) score | 26.4 (3.6) | 27.3 (2.7) | −0.91 (−1.51 to −0.31) | 0.003 |

| Positive attitudes towards screening | 182 (51) | 112 (65) | −14.1 (−23.0 to −5.0) | 0.002 |

| Completed screening test§ | 211 (59) | 130 (75) | −16.0 (−24.0 to −8.0) | <0.001 |

| Informed choice | 121 (34) | 21 (12) | 22.0 (15.0 to 29.0) | <0.001 |

| Involvement preferences in screening decision¶: | ||||

| Participant decides alone | 321 (90) | 164 (96) | −5.5 | 0.04** |

| Participant decides after consulting doctor | 14 (4) | 2 (1) | 2.7 | |

| Share decision equally | 17 (5) | 5 (3) | 1.9 | |

| Doctor decides after consulting or alone | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.9 |

Participants in the decision aid groups were slightly less positive than controls about screening using faecal occult blood testing; the mean scores were 26.4 for the decision aid groups and 27.3 for the control group (P=0.003). At three months, the difference in screening behaviour was statistically significant. The proportion of participants who had completed and returned the screening test was 75% (130/173) in the control group and 59% (211/357) in the decision aid groups (P<0.001). The tailored information showed no effect, with similar uptake rates in higher risk groups due to positive family history. Overall, 68% (232/341) of participants had completed the screening test by the time they were interviewed at the two week follow-up telephone call. This is similar to patterns of participation in screening reported in the Australian national bowel cancer screening programme, which indicates that most screening participants who return a completed faecal occult blood test kit do so within two to four weeks of it being sent.13

Informed choice

Participants’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour were categorised according to Marteau’s multidimensional model of informed choice (table 4).25 The proportion of participants making an informed choice was 22% higher in the decision aid groups than in the control group (34% (121/357) v 12% (21/172); P<0.001). Furthermore, a higher proportion of participants who received the government information (41% (71/172)) compared with the decision aid (15% (52/357)) made a “partly uninformed choice” about screening, completing the test with positive attitudes but inadequate knowledge. There was, however, little difference between the decision aid and control groups in the percentage of participants making a “completely uninformed choice” (having inadequate knowledge and inconsistent attitudes and behaviour). Decreasing and increasing the pass mark or threshold for adequate knowledge had little effect on this difference between groups in the percentage of participants making an informed choice. For example, by increasing the knowledge pass mark to 75% (≥9 out of 12), the difference remained about the same, at 20%.

Table 4.

Distribution of informed or uninformed choices for decision aid and control groups. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Choices and preferences for screening | Adequate knowledge | Positive attitudes | Uptake | Decision aid groups combined (n=357) | Standard information group (n=172) | % Difference (decision aid−control) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informed choice: | 120 (34) | 20 (12) | 22 (15 to 29) | |||

| Accept | Yes | Yes | Yes | 72 (20) | 18 (11) | 11 (4 to 16) |

| Decline | Yes | No | No | 48 (13) | 2 (1) | 12 (8 to 13) |

| Partly uninformed choice*: | ||||||

| Accept | Yes | No | Yes | 51 (14) | 9 (5) | 9 (2 to 16) |

| Decline | Yes | Yes | No | 29 (8) | 3 (2) | 6 (3 to 10) |

| Accept | No | Yes | Yes | 52 (15) | 71 (41) | −26 (−35 to −19) |

| Decline | No | No | No | 40 (11) | 17 (10) | 1 (−4 to 7) |

| Completely uninformed choice†: | ||||||

| Accept | No | No | Yes | 36 (10) | 32 (19) | −9 (−15 to 2) |

| Decline | No | Yes | No | 29 (8) | 20 (12) | −4 (−6 to 2) |

Involvement preferences in screening decision

After the intervention both groups showed a significant shift towards more active involvement in decision making (P<0.001). Most participants reported making the decision on their own (decision aid 90% (320/355) v control 96% (164/171)) compared with their stated pre-intervention preference for involvement in decision making (37% (143/384) and 41% (78/188)). Compared with the control group, however, participants in the decision aid groups showed a significant trend towards sharing or preferring to share the decision with the clinician (trend, P=0.04). From a proportional odds model it was estimated that participants in the decision aid groups were 2.5 times more likely to share or prefer to share the decision with the clinician (odds ratio 2.47, 95% confidence interval 1.07 to 5.69).

Secondary analyses

Decision quality and psychosocial outcomes

Table 5 presents the impact of the booklets on decisional quality and psychosocial outcomes.

Table 5.

Secondary outcomes for decision aid intervention groups combined and control group. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome* | Decision aid groups combined (n=357) | Standard information group (n=173) | Difference (decision aid−control) (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) decision satisfaction† | 4.21 (0.44) | 4.21 (0.43) | 0.00 (−0.09 to 0.08) | 0.91 |

| Mean (SD) confidence in decision making‡ | 4.67 (0.54) | 4.61 (0.62) | 0.06 (−0.04 to 0.16) | 0.26 |

| Mean (SD) anxiety§ | 28.20 (9.75) | 28.43 (10.56) | −0.23 (−0.62 to 0.45) | 0.80 |

| Decisional conflict¶ | ||||

| Total score: | 0.02** | |||

| 0 | 181 (51) | 65 (38) | 13 | |

| 1-25 | 101 (28) | 73 (42) | −14 | |

| >25 | 75 (21) | 35 (20) | 1 | |

| Informed subscale: | 0.03** | |||

| 0 | 233 (65) | 90 (52) | 13 | |

| 1-25 | 22 (6) | 13 (8) | −2 | |

| >25 | 102 (29) | 70 (41) | −12 | |

| Uncertainty subscale: | 0.89** | |||

| 0 | 275 (77) | 134 (78) | −1 | |

| 1-25 | 15 (4) | 5 (3) | 1 | |

| >25 | 67 (19) | 34 (20) | −1 | |

| Values clarity subscale: | 0.99** | |||

| 0 | 276 (78) | 134 (78) | 0 | |

| 1-25 | 22 (6) | 8 (5) | 1 | |

| >25 | 59 (17) | 31 (18) | −1 | |

| Support subscale: | 0.38** | |||

| 0 | 280 (78) | 130 (75) | 3 | |

| 1-25 | 13 (4) | 7 (4) | 0 | |

| >25 | 64 (18) | 36 (21) | −3 | |

| Worry about developing bowel cancer: | 0.78†† | |||

| None or a bit | 335 (94) | 159 (92) | 2 | |

| Quite or very | 22 (6) | 14 (8) | −2 | |

| Change in worry: | 0.89†† | |||

| Less worried | 50 (14) | 24 (14) | 0 | |

| No change | 252 (71) | 121 (70) | 1 | |

| More worried | 54 (15) | 27 (16) | −0.5 |

The total decisional conflict scores (maximum score 100) were significantly lower (P=0.02) in the decision aid groups (median 0, no decisional conflict) than in the control group (median 10); the means were 13.63 (SD 20.55) and 14.91 (SD 18.34), respectively. More participants in the decision aid groups than in the control group had low decisional conflict overall about the screening decision (total scale) than participants in the control group (51% (181/357) v 38% (65/173); table 5). This was primarily due to more participants in the decision aid groups (65% (233/357)) feeling informed about the decision and the potential benefits and harms of screening (informed subscale) than participants in the control group (52% (90/173); P=0.03).

The groups did not differ significantly in how satisfied (P=0.49) or confident (P=0.91) they were in their decision making. The decision aid did not increase general anxiety or worry about developing bowel cancer. The groups did not differ significantly in ratings of clarity (P=0.10) and helpfulness of the information (P=0.87). Most of the participants in each group reported reading all of the booklet (decision aid 78% (263/337) v control 75% (125/167)), and thought the information was clear (decision aid 98% (330/336) v control 100% (167/167)) and helpful (decision aid 96% (324/336) v control 97% (162/167)) in their decision making. A few more participants in the decision aid groups perceived the information as being balanced and fair compared with participants in the control group, but this was not significant (48% (160/334) v 41% (67/164); P=0.22). Only one participant used the question prompt list to talk to their doctor about the screening test. Nearly half (47% (166/357)) of participants in the decision aid group said they viewed the DVD. Of these, most (72% (119/166)) watched it after reading the booklet, found it clear and easy to follow (97% (161/166)) and helpful in making a decision about screening (96% (160/166)). Overall, there was no evidence of an interactive effect between risk of bowel cancer (based on family history) and completion of the test (Mantel-Haenszel P=0.99).

Discussion

A tailored decision aid can be effective in supporting adults with low education to make an informed choice about screening using faecal occult blood testing. The decision aid significantly increased participants’ knowledge about the cumulative outcomes of such screening, with over half showing sufficient knowledge for making an informed decision. In particular, the decision aid improved understanding about the number of people who die naturally from bowel cancer without screening (baseline risk) and the number of lives saved by screening (absolute risk reduction). Importantly, the proportion of participants in the decision aid groups who made an informed choice about screening increased by 22%, from 12% in the control group to 34% in the decision aid group. This was confirmed by significantly lower levels of decisional conflict in the decision aid group than among controls, which was primarily due to them feeling more informed about their decision and the potential benefits and harms of screening.

Although the decision aid did not make people more worried about developing bowel cancer, it did make them feel less positive about screening, and reduced uptake of the screening test by 16% (75% in the control group v 59% in the decision aid groups). It seems that this may have resulted from increasing their knowledge about the low personal benefit of screening. Overall, most participants reported making the screening decision on their own (without consulting a health professional), irrespective of which intervention they had read. However, the results indicated that clarifying to the reader that they have a choice about screening, making them aware of the possible limitations and downsides of screening, and advising them to consider how they value each outcome, did encourage some participants in the decision aid groups compared with the control group to share or prefer to share the decision with their doctor.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strengths of the study include its design (a randomised controlled trial), similar baseline characteristics across groups, and good recruitment (consent) and follow-up rates (84% and 98%, respectively). The high recruitment rates may have been because we were permitted (by the university research ethics committee) to telephone respondents directly, rather than recruiting by written communication. Opt-in methods (through written correspondence) have been shown to deter groups with low education and literacy from participating in research.35 36 Given the high recruitment and follow-up rates, we are confident that our sample is representative of the target audience and that the results are generalisable to adults with low education in the wider community. However, it is important to note that it was not specifically tested among a sample with measured levels of low literacy, which means the results may be an overestimate of the effect when generalised to adults with basic levels of literacy.

The trial also did not test the impact of the decision aid among socially advantaged groups and therefore it is unclear how the decision aid would have influenced informed choice and involvement in a sample with higher education. We know from trials of health literacy interventions that in some circumstances interventions have been effective in higher education and literacy groups but not in lower education and literacy groups.37 We think it is likely the decision aid will be understood by a better educated group and will support informed choice. However, we cannot predict the effect on screening behaviour or attitudes among a better educated population. Some researchers have suggested that information about harms may differentially dissuade lower education groups compared with their higher educated counterparts from carrying out preventive health behaviour since it encourages a focus on immediate harmful consequences and may bias participants with lower education away from valuing future benefits.38 If this proposition stands we may not observe the same attitude and behaviour effect of the decision aid in a better educated sample. However, this currently remains unknown.

Telephone interviews were considered the most appropriate strategy to recruit and interview a low education and literacy sample, since this group may experience difficulties completing written questionnaires. Although this data collection method is highly suitable for adults with low literacy, the personal telephone call may have encouraged participants to feel obliged to read and process the decision aid or control material. This is different from typical invitations organised by bowel cancer screening programmes outside of a research setting. This feature of the data collection process potentially reduces the extent to which the results can be generalised to how people may behave if they were sent the decision aid within the context of an organised screening programme without a telephone interview.

One of the strengths of this study is its strong internal validity, which is important for an efficacy (phase III) trial of this nature. A different design would be required for an implementation (phase IV) trial. It would be useful to carry out a further trial in which only participation in screening is measured from laboratory records as a result of the decision aid, and participants are not followed-up personally after they receive the intervention. However, since this was the first randomised trial to assess the effect of a decision aid in a low education sample, we considered it essential to measure a range of primary and secondary outcomes, including informed choice, using a method that was understandable and assured a reasonable response rate from the target sample. This meant that participants were telephoned for a follow-up interview and asked a battery of questions. We note that most published trials on decision aids use designs that personally follow-up participants to assess the impact of the decision aid, and that if we had not done this we would not have known whether the decision aid supported informed choice, which was a fundamental objective of this trial.

Another strength of this research is that we developed and evaluated the decision aid intervention in accordance with the International Patient Decision Aid Standards, which are designed to ensure a minimal level of quality for decision aids and are currently under revision.23 39 Although this approach is widely used by developers of decision aids, we recognise that the role of using criteria set out in the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (or checklists) to evaluate decision aids has been questioned, especially since it is unclear whether decision aids that comply with these criteria are more effective than those that do not.40

Although the current trial generates evidence that the decision aid was effective in helping adults with low education to make an informed choice about screening, it only provides a partial picture of the capacity of the intervention. Other issues are important, such as how the intervention was used and why it affected decision making.41 To tackle this we carried out a qualitative interview study with a subsample of participants to explore in-depth how they used the decision aid and made their decision about screening. This has enabled us to explore in more detail which specific elements of the interventions (for example, risk information and exercises to clarify patient values) were used and how they influenced participants’ decision making and screening behaviour. This is to be reported later.

Comparison with other studies

It is difficult to compare our results with those of previous trials on decision aids as most provide limited details on how they assessed knowledge or did not measure informed choice. In terms of knowledge, one study found that the provision of absolute and relative risk information (compared with no risk information) increased understanding about the positive predictive value of screening for bowel cancer by 17%.42 Other similar work has shown improvements in the proportion of participants (receiving a decision aid) having adequate knowledge about screening outcomes, by 15%24 and 20%.27 In the current trial, adequate knowledge increased by 38%, twice the amount shown in previous studies.

With regard to informed choice, a general practice based trial of a decision aid for faecal occult blood testing increased the proportion who made an informed decision by 8%, from 2% to 10%.24 A mammography screening decision tool for women aged 70 years also enabled 25% more women to make an informed choice about whether to continue screening (49% in control group v 74% in decision aid group).27 Similarly, in the current study, the absolute difference in the proportion who made an informed choice was 22% (12% in control group and 34% in decision aid group).

In this study, the decision aid resulted in a significant reduction in the number of people completing the screening test. Previous work has found that decision aids do not affect screening intentions or participation,24 27 42 43 44 although one decision aid trial found a 14% increase (from 23% to 37%) in screening participation in patients who received a video based decision aid.45 The tool, however, offered patients a choice between screening tests (for example, faecal occult blood testing, flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy), and did not seem to present the option of no screening. Furthermore, healthcare staff were not blinded to the group allocation and may have potentially tried to encourage more patients in the decision aid group to screen.

Several possible reasons may have resulted in the reduced uptake of faecal occult blood testing. Unlike existing national programmes for breast and cervical cancer screening, screening programmes using faecal occult blood testing are relatively new in Australia (and in the United Kingdom) and have not attracted the same amount of media coverage or widespread professional and public support. It is likely that most people have not been as exposed to traditional information designed to encourage screening using faecal occult blood testing, suggesting that public awareness and attitudes towards screening for bowel cancer are not as well established as other cancer screening programmes. In these circumstances it may not be surprising that presenting unbiased information on screening and explaining that a choice exists, affected attitudes and behaviour towards screening using faecal occult blood testing.

Most trials on decision aids for bowel cancer screening have been done in general practice settings where interventions are typically delivered to patients attending prescheduled consultations. Patients may therefore only have a short period to process the information and may have some difficulty declining the test that is being offered, without considering how they feel about it in relation to their values. Self administered (take home) decision aids may therefore be an effective strategy to help patients fully understand their options and make informed decisions in line with their preferences, with additional time and away from influence.

Another possible explanation for differences in screening uptake relates to the presentation of the risk information. We paid careful attention to the representation of population risks and benefits of screening (see web extra appendix 1) following our qualitative research with low literacy groups, which indicated that population diagrams were difficult to understand.22 This may have enhanced understanding of these elements of the decision aid compared with other trials. The government screening booklet contained information about the effectiveness of screening using faecal occult blood testing presented in relative risk format: “[FOBT] can reduce your risk of dying from bowel cancer by up to one third,” whereas the decision aid included personalised, absolute risk information, comparing the outcomes of screening with no screening. Communicating screening outcomes using relative risk format is well recognised as inappropriate to support understanding of information on the risks and benefits of screening, as it is associated with overestimating the benefits.46 47 Indeed, qualitative interviews with our trial participants were consistent with previous findings that the relative risk format was more persuasive than the absolute risk format. Relative risk information may create unrealistic expectations about the effectiveness of screening using the faecal occult blood test on mortality from bowel cancer, and influence screening decisions in favour of participation. In establishing population screening programmes careful consideration needs to be given to the possible implications of framing information in this way, as it may reinforce public misconceptions about screening.12

Almost all trials on decision aids (including the current one) focus on the short term impact of the decision aid on decision making, rather than the effect on health and quality of life outcomes over a longer period. Debate is ongoing about the appropriateness of decision quality measures such as decisional conflict and satisfaction, which have typically been used to assess the effectiveness of decision aids. In the current trial we measured decisional conflict as a secondary outcome. Participants obtained low scores on the decision conflict scale (which has traditionally been considered to be a “good” indicator of quality in the decision process) and the intervention groups did not differ. However, it is currently unknown whether low decisional conflict scores correspond with “better” decision making, and it has been suggested that higher scores may mean that people deliberate more carefully about their options.48 At present we have no data to indicate whether low or high decisional conflict is optimal.

Similarly, participants’ anxiety scores (as measured by the state trait anxiety inventory) were also low and no differences were observed between the decision aid and control groups. Our motivation to include this measure was to ensure that we did not, by the use of the decision aid and offer of choice, cause undue anxiety to participants at the time of decision making. Our results show that we did not. However, it should be noted that although short term anxiety was low, we do not know the effect on anxiety in the long term.49 Future research should investigate the extent to which decision aids influence both the decision making process and longer term outcomes in relation to patients’ quality of life, wellbeing, survival, and function.50

Policy implications and future research

This study shows that the decision aid may be an effective way to support a screening policy that values informed choice and equity in access to informed choice, as opposed to policy focused on achieving high uptake. These results present an important dilemma for policy makers and healthcare providers on how to communicate to the public about screening. Governments in Australia, the United Kingdom, and many other countries have advocated patient engagement in decision making and informed choice.51 52 Traditionally, governments have encouraged the uptake of screening for the public good, placing a greater emphasis on the benefits of participating, such as reduced mortality and morbidity.53 This is also underpinned by a belief that greater uptake leads to more cost effective screening programmes and consequently high uptake rates remain an important target for such screening providers. Studies have now shown that high participation does not necessarily guarantee cost effectiveness in screening programmes, especially if the programme does not have large set-up costs.54 Indeed, supporting informed choice in bowel cancer screening is unlikely to reduce cost effectiveness and in some circumstances may actually increase it.55 Furthermore, if informed choice, as set out by the General Medical Council, is to be adopted and promoted as a goal of high quality health care, it must be available to a broad spectrum of the community so they may equally exercise informed choice.

One study has put forward an alternative approach (as “consider an offer”) to communicating about screening.56 Within this approach, providers help people to carefully consider a screening recommendation or offer. This involves the provider clearly explaining to the individual why screening is being offered or recommended to them; encouraging people to make judgments about the trustworthiness of the recommendation or offer; providing further information, if that is desired, about the outcomes or other people’s preferences (for example, evidence based information about the benefits and harms of a screening intervention); and recognising that people might want to decline the recommendation or offer. This flexible approach allows people to respond to the screening invitation in a way that suits them best. For example, some may want to access more detailed information about the various outcomes of screening (as typically presented in a decision aid), whereas others may simply prefer to follow the recommendations of trusted healthcare providers. Thus this approach does not expect people to assess the credibility of research evidence by themselves nor does it restrict decision making to simply adhering to professional guidelines. This may provide a third way for screening providers seeking to reconcile informed choice with traditional approaches to screening participation.

Despite growing evidence that decision aids are effective in supporting decision making, their use in everyday clinical practice is limited.57 Although healthcare practitioners may support the notion of using decision aids, they often report that they do not have enough time to administer the tool during consultations and express concerns that it may adversely affect the doctor-patient relationship.58 Investigating possible ways in which the decision aid could be delivered into the wider community to people from a range of different education and literacy backgrounds is a priority for future research. We believe the decision aid could be made available to participants through general practitioners or national screening providers as a web or paper based tool. In our trial the paper based decision aid was sent with the faecal occult blood test kit to participants eligible for screening at home to read and complete as they wished. In this way, we reflected the current screening programme practice. Both the United Kingdom and Australia have mail based bowel screening programmes, with test kits sent to eligible participants’ homes. Further testing of alternative implementation strategies for a decision aid such as this one would be useful in a future pragmatic trial.

What is already known on this topic

- Patient decision aids increase knowledge and involvement in decision making, without increasing decisional conflict or anxiety

- Research has not examined the impact of decision aids among adults with low education and literacy—a group with poor knowledge about health, limited involvement in health decisions, and poor health outcomes

What this study adds

- A decision aid for bowel cancer screening helped adults with lower education to make an informed choice about screening

- Providing balanced, evidence based information about the benefits and harms of screening for bowel cancer may reduce participation in screening among adults with low education

We thank Les Irwig (Screening and Test Evaluation Program, University of Sydney) for invaluable advice and support to the study; the Hunter Valley Research Foundation for their computer assisted telephone interviewing services, in particular Caroline Veldhuizen (research fellow), who provided a highly efficient and enthusiastic service; Betty Lui (client services coordinator at Insure Bowel Cancer Screening Service, Enterix Australia) for clarifying queries and compiling the data from the faecal occult blood testing results; and all the participants. AB is now based at the Centre for Medical Psychology and Evidence-Based Decision-Making, Sydney School of Public Health, University of Sydney.

Contributors: KM conceived the study. KM, LT, AB, JS, and DN designed the study and obtained funding. SS contributed to the study design, coordinated the running of the study and the data collection. SS carried out the statistical analysis with advice from JS. SS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the analysis and the writing of the manuscript. All authors are guarantors.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (No 457381). The funder had no role in the design or conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in the preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that all authors had: no financial support for the submitted work from anyone other than their employer; no financial relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; and no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the University of Sydney human research ethics committee and the Australian national bowel cancer screening programme.

Data sharing: The dataset is available from Kirsten McCaffery at kirsten.mccaffery@sydney.edu.au. Consent was not obtained but the presented data are anonymised and risk of identification is low.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c5370

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Extract from decision aid aimed at males

Values clarification exercise for women with no family history of bowel cancer

Marking scheme for knowledge questions

References

- 1.Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. How we work—consumer engagement. 2009. www.safetyandquality.gov.au/internet/safety/publishing.nsf/Content/CES-consult.

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mission statement and budget. 2009. www.ahrq.gov/.

- 3.Department of Health (UK). National Health Service constitution. 2009. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_085814.

- 4.Haynes R, Devereaux P, Guyatt C. Clinical expertise in the era of evidence-based medicine and patient choice. Evid Based Med 2002;7:36-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montori VM, Guyatt GH. Progress in evidence-based medicine. JAMA 2008;300:1814-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V, Tetroe J, Entwistle V, Llewellyn-Thomas H, et al. Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic review. BMJ 1999;319:731-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, Barry M, Col Nananda F, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;3:CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeWalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes. A systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:1228-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.General Medical Council (UK). Consent guidance: patients and doctors making decisions together. 2008. www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/consent_guidance_index.asp.

- 10.Sense about science. Making sense of screening. 2009. www.senseaboutscience.org.uk/index.php/site/project/415/.

- 11.Irwig L, McCaffery K, Salkeld G, Bossuyt P. Informed choice for screening: implications for evaluation. BMJ 2006;332:1148-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gotzsche PC, Hartling OJ, Nielsen M, Brodersen J, Jorgensen KJ. Breast screening: the facts—or maybe not. BMJ 2009;338:b86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Bowel Cancer Screening Program monitoring report. AIHW, 2007.

- 14.Kinnersley P, Edwards A, Hood K, Ryan R, Prout H, Cadbury N, et al. Interventions before consultations to help patients address their information needs by encouraging question asking: systematic review. BMJ 2008;337:a485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Information paper: census of population and housing—socio-economic indexes for areas, Australia 2001. Australian Government Publishing Service, 2003.

- 16.National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia). Guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer. A guide for general practitioners. NHMRC, 2000.

- 17.Austalian Bureau of Statistics. Adult literacy and life skills survey, summary results. ABS, 2006.

- 18.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. 2nd ed. Lippincott, 1996.

- 19.Hibbard JH, Peters E. Supporting informed consumer health care decisions: data presentation approaches that facilitate the use of information in choice. Annu Rev Public Health 2003;24:413-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houts PS, Doak CC, Doak LG, Loscalzo MJ. The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:173-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith SK, Trevena L, Barratt A, Dixon A, Nutbeam D, Simpson JM, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a bowel cancer screening decision aid for adults with lower literacy. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:358-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith SK, Trevena L, Nutbeam D, Barratt A, McCaffery KJ. Information needs and preferences of low and high literacy consumers for decisions about colorectal cancer screening: utilizing a linguistic model. Health Expect 2008;11:123-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, Volk R, Edwards A, Coulter A, et al. The International Patient Decision Aids Standards Collaboration. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ 2006;333:417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trevena L, Irwig L, Barratt A. Randomized trial of a self-administered decision aid for colorectal cancer screening. J Med Screen 2008;15:76-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marteau T, Dormandy E, Michie S. A measure of informed choice. Health Expect 2001;4:99-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michie S, Dormandy E, Marteau TM. The multi-dimensional measure of informed choice: a validation study. Patient Educ Couns 2002;48:87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathieu E, Barratt A, Davey H, McGeechan K, Howard K, Houssami N. Informed choice in mammography screening: a randomized trial of a decision aid for 70-year-old women. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2039-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The Control Preferences Scale. Can J Nurs Res 1997;29:21-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connor AM. Decisional conflict scale—user manual. 2008. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/eval.html.

- 30.Sainfort F, Booske BC. Measuring post-decision satisfaction. Med Decis Making 2000;20:51-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Connor AM. Decision self efficacy scale—user manual.1995. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/eval.html.

- 32.Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br J Clin Psychol 1992;31:301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutton S, Bickler G, Sancho-Aldridge J, Saidi G. Prospective study of predictors of attendance for breast screening in inner London. J Epidemiol Community Health 1994;48:65-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Connor AM. Acceptability tool—user manual.1996. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/eval.html.

- 35.Young AF, Dobson AJ, Byles JE. Health services research using linked records: who consents and what is the gain? Aust N Z J Public Health 2001;25:417-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang N, Shih S-F, Chang H-Y, Chou Y-J. Record linkage research and informed consent: who consents? BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clement S, Ibrahim S, Crichton N, Wolf M, Rowlands G. Complex interventions to improve the health of people with limited literacy: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:340-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crockett R, Wilkinson TM, Marteau TM. Social patterning of screening uptake and the impact of facilitating informed choices: psychological and ethical analyses. Health Care Anal 2008;16:17-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Bennett C, Newcombe R, Politi M, Durand M, et al. Assessing the quality of decision support technologies using the International Patient Decision Aid Standards instrument (IPDASi). PLoS One 2009;4:e4705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bekker HL. The loss of reason in patient decision aid research: do checklists damage the quality of informed choice interventions? Patient Educ Couns 2010;78:357-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell N, Murray E, Darbyshire J, Emery J, Farmer A, Griffiths F, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ 2007;334:455-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf AM, Schorling JB. Does informed consent alter elderly patients’ preferences for colorectal cancer screening? Results of a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:24-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dolan JG, Frisina S. Randomized controlled trial of a patient decision aid for colorectal cancer screening. Med Decis Making 2002;22:125-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griffith J, Fichter M, Fowler F, Lewis C, Pignone M. Should a colon cancer screening decision aid include the option of no testing? A comparative trial of two decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2008;8:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pignone M, Harris R, Kinsinger L. Videotape-based decision aid for colon cancer screening. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:761-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malenka DJ, Baron JA, Johansen S. The framing effect of relative and absolute risk. J Gen Intern Med 1993;8:543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gigerenzer G, Edwards A. Simple tools for understanding risks: from innumeracy to insight. BMJ 2003;327:741-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson WL, Han PKJ, Fagerlin A, Stefanek M, Ubel PA. Rethinking the objectives of decision aids: a call for conceptual clarity. Med Decis Making 2007;27:609-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bekker HL, Legare F, Stacey D, O’Connor A, Lemyre L. Is anxiety a suitable measure of decision aid effectiveness: a systematic review? Patient Educ Couns 2003;50:255-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCaffery K, Irwig L, Bossuyt P. Patient decision aids to support clinical decision making: evaluating the decision or the outcomes of the decision. Med Decis Making 2007;27:619-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission (Australia). A healthier future for all Australians—final report of the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. 2009. www.health.gov.au/internet/nhhrc/publishing.nsf/Content/nhhrc-report. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Department of Health (UK). NHS constitution: the NHS belongs to us all. 2009. www.nhs.uk/choiceintheNHS/Rightsandpledges/NHSConstitution/Pages/Overview.aspx.

- 53.Raffle A. Information about screening—is it to achieve high uptake or to ensure informed choice? Health Expect 2001;4:92-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torgerson DJ, Donaldson C. An economic view of high compliance as a screening objective. BMJ 1994;308:117-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Howard K, Salkeld G, Irwig L, Adelstein BA. High participation rates are not necessary for cost-effective colorectal cancer screening. J Med Screen 2005;12:96-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Entwistle VA, Carter SM, Trevena L, Flitcroft K, Irwig L, McCaffery K, et al. Communicating about screening. BMJ 2008;337:a1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barnato AE, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Peters EM, Siminoff L, Collins ED, Barry MJ. Communication and decision making in cancer care: setting research priorities for decision support/patients’ decision aids. Med Decis Making 2007;27:626-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harrison JD, Masya L, Butow P, Solomon M, Young J, Salkeld G, et al. Implementing patient decision support tools: moving beyond academia? Patient Educ Couns 2009;76:120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Extract from decision aid aimed at males

Values clarification exercise for women with no family history of bowel cancer

Marking scheme for knowledge questions