Estimation of the serial interval of influenza (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Mar 15.

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Estimates of the clinical-onset serial interval of human influenza infection (time between onset of symptoms in an index case and a secondary case) are used to inform public health policy and to construct mathematical models of influenza transmission. We estimate the serial interval of laboratory-confirmed influenza transmission in households.

METHODS

Index cases were recruited after reporting to a primary healthcare center with symptoms. Members of their households were followed up with repeated home visits.

RESULTS

Assuming a Weibull model and accounting for selection bias inherent in our field study design, we used symptom-onset times from 14 pairs of infector/infectee to estimate a mean serial interval of 3.6 days (95% confidence interval = 2.9–4.3 days), with standard deviation 1.6 days.

CONCLUSION

The household serial interval of influenza may be longer than previously estimated. Studies of the complete serial interval, based on transmission in all community contexts, are a priority.

The clinical-onset serial interval of an infectious disease is defined as the duration of time between onset of symptoms in an index case and a secondary case.1,2 Estimates of the serial interval of human influenza are incorporated into models of interpandemic and pandemic influenza as the generation time, which is formally defined as the average time between the infection of an infector and the infection of their infectees, calculated on a per infector basis.3 Current estimates of the mean serial interval from empirical data include 1–2 days,4 2–3 days5,6 and 3–4 days.7,8

Many studies of influenza transmission are based on recruitment of index cases after onset of symptoms, also known as a case-ascertained design.9 We used self-reported symptoms and signs and laboratory data from a recent study10 to estimate the serial interval for interpandemic influenza during the 2007 season in Hong Kong.

METHODS

In a recent household transmission study,10 122 index cases with laboratory-confirmed influenza and their 350 household contacts were followed. Index cases were eligible to participate if they presented to a primary care provider and met the following conditions: at least 2 symptoms or signs associated with influenza-like illness, initial symptoms within the previous 48 hours, and an absence of influenza-like illness among household members within the previous 2 weeks. Households were followed up with 4 home visits during the following 10 days. Nose and throat swabs were collected from all household members at each home visit for laboratory confirmation of infection by viral culture or reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). 10 We investigated the serial interval by examining the time from symptom onset in laboratory-confirmed index cases (reported at recruitment as the date of first symptoms of influenza-like illness) to symptom onset in corresponding household contacts. Symptom onset was defined as the first day when the subject reported at least 1 of 5 symptoms and signs: fever (37.8°C or higher) cough, headache, sore throat, or aches or pains in muscles or joints.

Any analysis of serial intervals in studies that uses symptom-based recruitment must allow for selection bias due to study design. For example, any subjects recruited into our study 2 days after symptom onset would not contribute information about serial intervals shorter than 48 hours because a secondary case in the household would not meet our inclusion criteria. Similarly, data from subjects recruited 1 day after symptom onset would be “left-truncated” at 1 day. Truncation would not be a problem for subjects recruited on the day of symptom onset.

Statistical methods for the analysis of time-to-event data can accommodate censoring and truncation.11–14 To estimate the serial interval we fitted parametric models including the Weibull, lognormal, and gamma distributions and compared these with nonparametric estimates, allowing for left truncation due to the study design. We compared parametric models by using the Akaike information criterion (AIC).15 In sensitivity analyses we used mixture models to incorporate risk of community transmission in estimates of the serial interval. In the eAppendix we provide further details of the statistical methods used here (available with the online version of this article). Analyses were performed using R version 2.6.1.16 Further information about the study design, raw data from the study, and R code to permit reproducible statistical analyses are available on the authors’ website http://www.hku.hk/bcowling/influenza/HK_NPI_study.htm.

RESULTS

Laboratory testing of household specimens by viral culture and reverse-transcriptionase- PCR identified infections in 21 of the 350 household contacts during the study period.10 We cleaned the raw data17 to ensure agreement between symptom-onset data and available laboratory data (eFig. 1, http://links.lww.com). Only 14 (67%) household contacts with laboratory-confirmed influenza experienced any of the 5 symptoms or signs (eTable 1, http://links.lww.com).

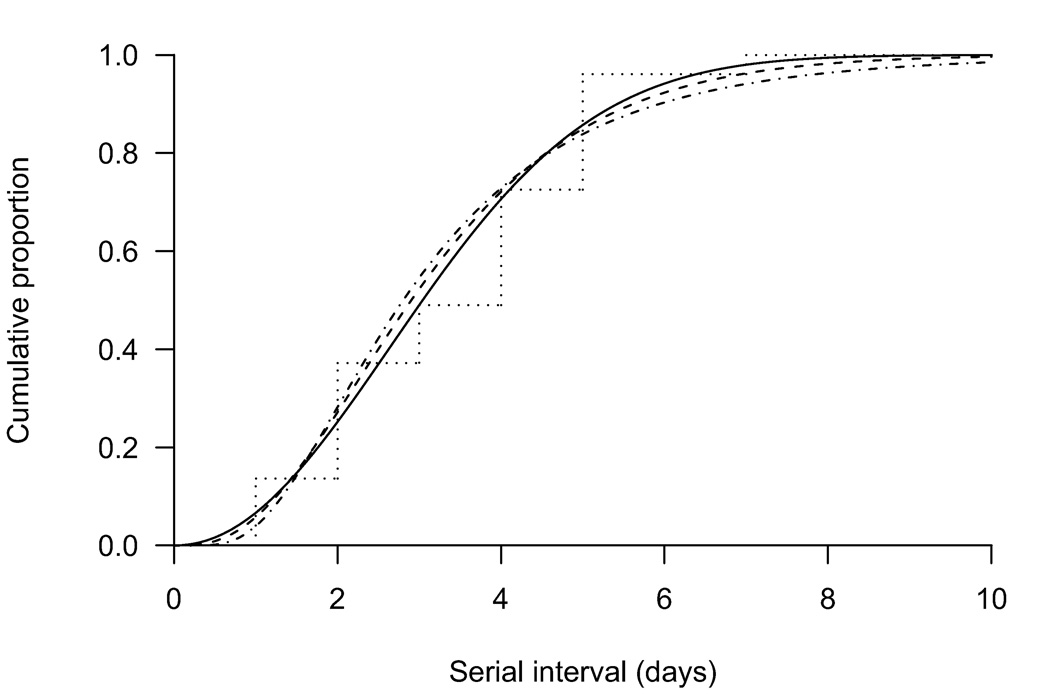

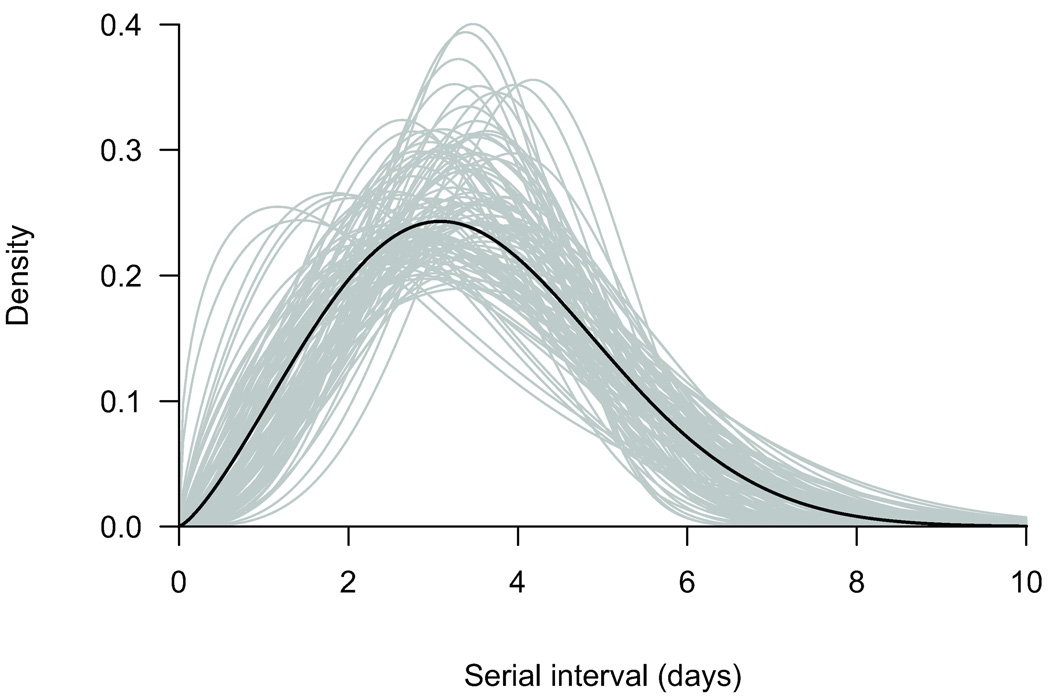

Weibull, gamma, and lognormal parametric models for the serial interval agreed with nonparametric estimates (Fig. 1) whereas the AICs slightly favored the Weibull model (eTable 2, http://links.lww.com) with a mean serial interval of 3.6 days (95% CI = 2.9–4.3 days). A parametric bootstrap approach with 1000 resamples was used to calculate confidence intervals,18 and 100 simulations are shown in Figure 2 to illustrate the uncertainty. In sensitivity analyses we investigated mixture models to incorporate risk of community transmission (eAppendix, http://links.lww.com), but there was little information in the data on this risk and estimates of the serial interval were unchanged (eTable 3 http:/links.lww.com, eFig. 2, http://links.lww.com).

Figure 1.

Estimated serial interval of influenza (cumulative distributions) using Weibull (solid), gamma (dashed), and lognormal (dot-dashed) parametric models compared with a nonparametric estimate (dotted).

Figure 2.

Estimated serial interval of influenza (density function) assuming a Weibull distribution (black line) and the associated uncertainty (gray lines) from 100 parametric bootstrap resamples.

DISCUSSION

We estimated the household serial interval of influenza to be between 3 and 4 days, which is longer than previous estimates based on similar study designs.5,6 A strength of our study is that secondary cases were confirmed by laboratory testing. We adjusted for potential bias from truncation by study design (eAppendix, http://links.lww.com). This was necessary because index cases were not recruited if secondary cases had already appeared. Our resulting estimate for the serial interval is longer than the generation time used in some transmission models.3–6

The serial interval is the sum of 2 distinct phases of the natural history of influenza infection, namely, the infectious period (from exposure to infection) and the incubation period (from infection to symptoms). An often-used estimate of the incubation distribution is based on 36 laboratory-confirmed secondary cases from a single infector on an airplane where symptom onset mostly appeared within 1–2 days of infection (median 1.5 days).19 Even less is known about the duration of infectiousness and its variability over time. Experimental infections suggest that viral shedding peaks around the time of symptom onset and declines with time; viral shedding can persist for up to 1 week after infection20 (perhaps longer in children). Our finding of a mean serial interval of 3.6 days suggests that the average time from symptom onset in the index case to secondary infection in the household setting may be around 2 days, assuming that time from secondary infection to secondary onset is 1.5 days (based on the airplane data19).

Studies currently in progress are using case-ascertainment recruitment designs to evaluate the efficacy of interventions to reduce influenza transmission in households.10 Given that index cases in these studies are often not recruited until at least 1 day after symptom onset, our findings suggest that these designs may underestimate the true effectiveness of the interventions because some infections may have occurred prior to recruitment and intervention. Nevertheless, provided that interventions can be applied soon after symptom onset, it is likely that such studies would be able to observe attenuated efficacies, and this should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results.

Our study had some limitations. First, our results are based on a small number of transmission events. Second, our data correspond only to transmission of interpandemic influenza within the household; the serial interval of transmission in other settings or in a pandemic may be different. Third, we may have misinterpreted some coprimary cases as secondary cases, leading us to underestimate the serial interval. With a small sample size and no obvious bimodality in the distribution of onset times, it is difficult to separate possible coprimary cases from the left-hand tail of the distribution. However, most coprimary cases would be excluded by our study design.

Some secondary cases may be wrongly attributed to the household index where infection of the household contact actually occurred outside the home from another infected person. Our main analysis does not explicitly allow for community transmission. However, the external force of infection is thought to be orders of magnitude lower than the force of infection within the household.21 Incorporating this in sensitivity analyses did not change our estimates of the serial interval (eTable 3, http://links.lww.com).

It is unlikely that we have confused secondary and tertiary cases in our analysis, because in households with multiple apparent secondary infections, symptoms appeared at the same time (in 1 household 2 asymptomatic secondary cases appeared at different times) (eTable 1, http://links.lww.com). In datasets in which there is the possibility of coprimary or tertiary cases, the methods presented here would need to be modified.

We may have missed some secondary cases due to errors in the laboratory data, or for example if the period of viral shedding fell entirely within the home visits, which on average took place at 3-day intervals. It is known from experimental infections that viral shedding typically begins around the same time as symptom onset,20 Therefore we felt justified in incorporating laboratory data when determining the true date of symptom onset (eTable 1, http://links.lww.com). Finally, our case-ascertainment study design naturally excluded household index cases with asymptomatic or subclinical infections. It would be challenging to collect longitudinal data on a cohort large enough to detect asymptomatic index cases and subsequent secondary cases.

There is a well-known relationship between the basic reproductive number, R0, and the serial interval, and modeling results can be sensitive to the choice of serial interval.22,23 If and when larger datasets become available, it would be interesting to compare estimates of the serial interval for transmission in different settings and to investigate heterogeneities in the serial interval due to infector characteristics (eg, viral shedding), infectee characteristics (eg, antibody titers) or virus type or subtype.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

Acknowledgments

We thank all the doctors, nurses, and staff of participating centers for facilitating recruitment; Kwok-Hung Chan for laboratory assistance; and Calvin Cheng, Rita Fung, Lai-Ming Ho, Yolanda Yan, and Eileen Yeung for research support. We thank the two referees for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Funding:

Support by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant no. 1 U01 CI000439-01), the Research Fund for the Control of Infectious Disease, Food and Health Bureau, Government of the Hong Kong SAR (grant no. HKU-AA-23), US National Institutes of Health cooperative agreement 5 U01 GM076497 (Models of Infectious Disease Agent Study, ML), and the Area of Excellence Scheme of the Hong Kong University Grants Committee (grant no. AoE/M-12/06).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fine PEM. The interval between successive cases of an infectious disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(11):1039–1047. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipsitch M, Cohen T, Cooper B, et al. Transmission dynamics and control of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300(5627):1966–1970. doi: 10.1126/science.1086616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu JT, Riley S, Fraser C, Leung GM. Reducing the impact of the next influenza pandemic using household-based public health interventions. PLoS Med. 2006;3(9):e361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sertsou G, Wilson N, Baker M, Nelson P, Roberts MG. Key transmission parameters of an institutional outbreak during the 1918 influenza pandemic estimated by mathematical modelling. Theor Biol Med Model. 2006;3:38. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-3-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferguson NM, Cummings DA, Cauchemez S, et al. Strategies for containing an emerging influenza pandemic in Southeast Asia. Nature. 2005;437(7056):209–214. doi: 10.1038/nature04017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferguson NM, Cummings DA, Fraser C, et al. Strategies for mitigating an influenza pandemic. Nature. 2006;442:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature04795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viboud C, Boelle PY, Cauchemez S, et al. Risk factors of influenza transmission in households. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(506):684–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirotsu N, Ikematsu H, Iwaki N, et al. Effects of antiviral drugs on viral detection in influenza patients and on the sequential infection to their family members - serial examination by rapid diagnosis (Capilia) and virus culture. Int Congress Ser. 2004;1263:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y, Longini IM, Jr, Halloran ME. Design and evaluation of prophylactic interventions using infectious disease incidence data from close contact groups. App Stat. 2006;55(3):317–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9876.2006.00539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowling BJ, Fung ROP, Cheng CKY, et al. Preliminary findings of a randomized trial of non-pharmaceutical interventions to prevent influenza transmission in households. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(5):e2101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Statistics for biology and health. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2003. Survival analysis : techniques for censored and truncated data. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turnbull BW. The empirical distribution function with arbitrarily grouped, censored and truncated data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B. 1976;38:290–295. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindsey JC, Ryan LM. Tutorial in biostatistics: methods for interval-censored data. Stat Med. 1998;17(2):219–238. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980130)17:2<219::aid-sim735>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowling BJ, Muller MP, Wong IO, et al. Alternative methods of estimating an incubation distribution: examples from severe acute respiratory syndrome. Epidemiology. 2007;18(2):253–259. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000254660.07942.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: Petrov BN, Csaki F, editors. Second international symposium on information theory. Budapest: Academiai Kiado; 1973. pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 16.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van den Broeck J, Cunningham SA, Eeckels R, Herbst K. Data cleaning: detecting, diagnosing, and editing data abnormalities. PLoS Med. 2005;2(10):e267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shao J, Tu D. The jackknife and bootstrap. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moser MR, Bender TR, Margolis HS, et al. An outbreak of influenza aboard a commercial airliner. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110(1):1–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrat F, Vergu E, Ferguson NM, et al. Time lines of infection and disease in human influenza: a review of volunteer challenge studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(7):775–785. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cauchemez S, Carrat F, Viboud C, Valleron AJ, Boelle PY. A Bayesian MCMC approach to study transmission of influenza: application to household longitudinal data. Stat Med. 2004;23(22):3469–3487. doi: 10.1002/sim.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishiura H. Time variations in the transmissibility of pandemic influenza in Prussia, Germany, from 1918–19. Theor Biol Med Model. 2007;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallinga J, Lipsitch M. How generation intervals shape the relationship between growth rates and reproductive numbers. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;274(1609):599–604. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix