The Interplay Between Mitochondrial Dynamics and Mitophagy (original) (raw)

Abstract

Mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy are recognized as two critical processes underlying mitochondrial homeostasis. Morphological and bioenergetic characterization of the life cycle of an individual mitochondrion reveals several points where fusion, fission, and mitophagy interact. Mitochondrial fission can produce an impaired daughter unit that will be targeted by the autophagic machinery. Mitochondrial fusion, on the other hand, may serve to dilute impaired respiratory components and thereby prevent their removal. The inverse dependency of fusion and mitophagy on membrane potential allows them to act as complementary rather than competitive fates of the daughter mitochondrion after a fission event. We discuss the interplay between mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy in different tissues and in different disease models under both stress-induced and steady-state conditions. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 1939–1951.

Introduction

During the past decade, mitochondrial dysfunction has been demonstrated to be a central characteristic of several metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity as well as heart failure, Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, and aging. Under these conditions, accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria leads to oxidative stress and impairs cell function (21, 63, 99, 107). This phenomenon drew attention to two processes, mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy, identified as key determinants of mitochondrial quality control.

Mitophagy refers to the selective removal of mitochondria by the autophagic machinery. Mitophagy appears to be a universal route for the degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria. Under certain physiological settings, mitophagy can also eliminate functional mitochondria as seen during erythroid differentiation (106), oocyte fertilization (98), or during starvation (27). Although there is evidence that other organelles and cellular compartments, such as endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (104), perixosomes (24, 92), and ribosomes (6), also undergo selective autophagy, mitophagy seems to be of special importance for two reasons: (i) mitochondria are one of the main sources of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (therefore, they are also the immediate targets of ROS damage). (ii) Dysfunctional mitochondria that are not degraded can produce higher amounts of ROS, be more susceptible to the release of cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor, and thereby, amplify ROS damage (15, 34).

Mitochondrial dynamics refers to repetitive cycles of fusion and fission between mitochondria (56, 97, 119). These opposing processes determine the architecture of the entire mitochondrial population of the cell and influence nearly every aspect of mitochondrial functions, including respiration, calcium buffering, and apoptosis (1, 2, 28, 51, 100). In addition, fusion and fission events per se (and not only the resultant effect on architecture) are suggested to impact mitochondrial homeostasis. Fission events were demonstrated to play a role in segregating dysfunctional mitochondria from the entire mitochondrial web (5, 30, 112) and to sort out mutant mtDNA copies (61, 103). Fusion events were suggested as a complementary route by which mitochondria quickly equilibrate matrix metabolites (43, 44, 47, 86, 111), intact mtDNA copies (3, 73, 80, 95), and mitochondrial membrane components (10, 122).

The simplistic view of a slowly metabolically deteriorating mitochondrion is complicated, given the high rate of mitochondrial content exchange permitted by fusion and fission events. When a small fraction of mitochondria within a cell are tagged by matrix-targeted photoactivatable (PA) GFP, the latter can reach equilibration in some cells within ∼1 h (47, 48, 70, 110). Given that the turnover of mitochondrial proteins is in the range of hours to days (69), it is predicted that the mitochondrial population within a cell will be homogenous in protein content and, consequently, in function. This contradiction was addressed by the understanding that fusion is a selective process and that mitochondria that are destined to mitophagy exist in a preautophagic pool. The preautophagic pool is characterized by mitochondria that are relatively depolarized and are fusion deficient.

During the last 4 years, numerous studies reported on the interaction between mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy in neurons, skeletal and cardiac myocytes, and pancreatic β-cells. We focus this review on aspects that concern mitochondrial dynamics.

Depolarized Mitochondria Are the Substrate for Mitophagy

Mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) is the driving force for mitochondrial ATP synthesis. Depolarization below a certain Δψm may indicate impaired mitochondrial function and is a prerequisite for mitophagy (27, 90, 110). Mitochondrial depolarization appears to precede the translocation of the proteins that tag mitochondria for mitophagy such as Parkin and PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (Pink1) (75, 76). Yet, although an essential condition depolarization alone is insufficient to trigger mitophagy.

Mitochondrial depolarization may be the result of a gradual or spontaneous deterioration or, alternatively, may occur as a result of a regulated event. To understand the events leading to appearance of depolarized mitochondria and the subsequent mechanism(s) that target them to mitophagy or metabolic rescue, one must characterize the bioenergetic and biochemical properties of the life cycle of mitochondria.

Spontaneous Generation of Depolarized Mitochondria Is Not a Frequent Event (Fission-Independent Pathway)

In both plants and mammalian cells, mitochondria go through continuous cycles of fusion and fission events in a kiss-and-run pattern, that is, a brief fusion event (∼tens of seconds) that is followed by fission (3, 57, 110, 113). As a result, mitochondria spend most of their time in their postfission state as solitary units before entering a subsequent fusion phase. It is therefore suggested that the life cycle of mitochondria can be divided into two periods, the prefusion period (solitary period) and the postfusion period when the mitochondrion is connected to another (networked period).

Depolarized mitochondria may therefore be the result of a spontaneous depolarization during the solitary or networked period or during the transition between them. A number of studies have reported on the monitoring of individual mitochondria over time and the observation of a specific depolarization event. Loew et al. provided one of the earliest quantitative measurements of individual mitochondria (using the Δψm-dependent dye TMRE) that were tracked in the z-stack with high temporal resolution. They reported stable Δψm for a period of 40–80 s that could be followed by a drop of >15 mV (58). This pioneering study was, however, limited by the lack of technology to assure that the detected mitochondrion did not go through fusion and/or fission events during the recording time. As fission can occur without movement of the two daughter mitochondria or involve only the inner (but not the outer) mitochondrial membrane (62, 111), it cannot be reliably identified by observation of separation of a mitochondrion into two organelles.

In COS7, INS1, and primary β-cells, prolonged tracking (up to 2 h) revealed that mitochondria retain a stable Δψm during the solitary period (110, 121). During most of the time (95% of the recording period), Δψm of the mitochondrion was within ±2.7 mV of its average baseline. This observation indicates that continuous deterioration in Δψm during the solitary phase is an unlikely (or infrequent) route for the generation of depolarized mitochondria under normal conditions.

Fission-Induced Mitochondrial Depolarization

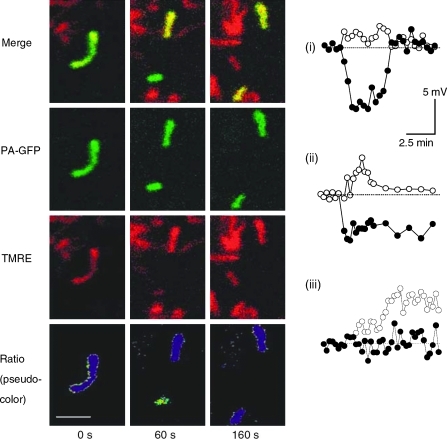

In contrast to the remarkable stability of Δψm under control conditions during the solitary period, fission events are associated with large changes in Δψm. Interestingly, electron microscope tomography shows that fission events can yield asymmetric daughter mitochondria (5, 64) and unequal nucleoid distribution (3). Direct measurements of Δψm in INS1 cells and COS7 cells show that in the majority of the fission events one of the two daughter mitochondria will leave the fission event with some level of depolarization (Δψm difference >5 mV) (110) (Fig. 1). The depolarization phase is often transient (Fig. 1i, iii), and in only ∼5% of events it is of sustained nature (Fig. 1ii). Given the high frequency of mitochondrial fission in these and other cell lines (47, 113) (a fission event occuring every 22 min or less), mitochondrial fission constitutes a principal route for generating (depolarized) mitochondria that are later targeted by the mitophagy machinery.

FIG. 1.

An example of a fission event that yields an ∼9 mV difference between the two daughter mitochondria. The pseudocolor represents the membrane potential and is derived from a ratio image of TMRE and matrix-targeted photoactivatable (mtPA) GFP. The pseudocolored image depicts two time spots, 60 s before fission and 160 s after fission. Scale bar: 2 μm. Charts of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) over time under control conditions are shown to the right. Numbers (i)–(iii) depict the three most common changes to membrane during a fission events as observed in INS1 cells. (see text for further details). Data are modified from Twig et al. (110). (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

Altered Expression of Fusion and Fission Proteins Modify Mitophagy

Table 1 summarizes studies that linked mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. The view of mitochondrial fission as a prerequisite for mitophagy is supported by genetic manipulation of the pro-fission proteins Fis1 and Drp1 (Table 1). Knockdown of FIS1 (by siRNA) or overexpression of a dominant negative isoform of DRP1 (DRP1K38A) reduces mitochondrial autophagy exclusively, as confirmed by the lack of an increase in ER mass inside the autophagosomes (APs) (4, 110). Overexpression of hFis1 reduces the mitochondrial (but not ER) mass in HeLa (28, 30) and INS1 cells (83), consistent with the notion that stimulation of fission facilitates mitochondrial autophagy under some circumstances. Arnoult et al. showed that overexpression of Drp1 facilitates mitochondrial elimination under various proapoptotic stimuli (4). Endophilin B1 (also known as Bif-1), a Drp1-dependent mediator of mitochondrial fission (48), interacts with Beclin 1 and colocalizes with AP markers LC3, Atg5, and Atg9 in response to nutrient starvation (105). Its loss is associated with tubulation of mitochondria (48) and suppression of autophagy (105).

Table 1.

Effect of Manipulations in Mitochondrial Proteins Opa1, Mfn1/2, Drp1, and Fis1 on Autophagy and Mitophagy

| Manipulation | Cell type | Effect on mitophagy | Reference | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fis1 RNAi | INS1 β-cells | Reduction of 70% in APs containing mitochondria | (110) | No change in the mass of APs containing ER |

| Fis1 Overexpression | HeLa cells, INS1 β-cells | Reduces total mitochondrial volume by ∼50% | (28, 83) | No change in ER morphology or total ER area |

| HeLa cells | 50% increase in total APs mass. No direct assessment of mitophagy | (30) | Qualitative analysis suggests medium-high correlation between LC3 and mitochondrial markers | |

| Drp1K38A | INS1 β-cells | Reduction of 75% in APs containing mitochondria | (110) | No change in the mass of APs containing ER |

| Drp1 RNAi | HeLa cells | Decrease in mitophagy (qualitative) | (85) | A general increase in autophagy. |

| Drp1 overexpression | HeLa cells | 70% decrease in mitochondrial mass | (4) | No specific tests for mitophagy |

| Opa1 Overexpression | INS1 β-cells | Reduction of 63% in APs containing mitochondria | (110) | No change in the mass of APs containing ER |

| Opa1 heterozygous mutant mice | Retinal Ganglion cells | An increase in general autophagy | (120) | No specific tests for mitophagy |

| Mfn1 overexpression | INS1 β-cells | 40% decrease in mitochondrial volume | (83) | No specific tests for mitophagy |

| Mfn1 loss of function (overexpression of Mfn1 DN) | INS1 β-cells | Unchanged mitochondrial mass | (83) | Insignificant slight decrease in mitochondrial volume. No specific tests for mitophagy. |

| Mfn2 KO | MEFs | Inhibition of autophagy | (36) | No specific tests for mitophagy |

Recently, Hailey et al. suggested that under starvation conditions the mitochondrial outer membrane contributes components of the AP (36). In this process, mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) (18) was found to be essential (36). These findings indicate that the proteins that are generally classified as “profusion proteins” have additional roles that affect autophagy. Future studies need to test whether the findings of Hailey et al. can be generalized to other conditions where damaged mitochondria (with potentially damaged components in their membrane) need to be removed by autophagy.

Mitochondrial Fission, Organelle Length, and Mitophagy—Size Does Not Matter

Several studies have linked mitochondrial size to the rate of mitophagy. Studies that visualize mitochondria within APs reported that the organelles' size was small (<1 μm in most cases) in a variety of cell types (27, 31, 37, 75, 77, 112). Yet, reduction of organelle size independently of its energetic status does not trigger mitophagy. Mitophagy rate in INS1 cells is reduced by ∼65%–75% by Opa1 overexpression or by the inhibition of fission (110). The latter is associated with highly ramified architecture, whereas high levels of Opa1 overexpression in these mitochondria are associated with fragmented architecture with an intact fusion capacity and Δψm cellular heterogeneity (70, 110).

Mitochondrial Fragmentation as a Universal Stress Response

The above observations indicate that fission is an event that can alter the energetic state of the mitochondrion and thereby the organelle fate. Although under some conditions, mitochondria hyperfuse as a first line of defense to nonmitochondrial metabolic insults (109), other insults that directly affect mitochondrial metabolism are associated with significant unbalanced fission mainly because of a decreased fusion rate (also referred to as mitochondrial fragmentation). Depletion of ATP either by inhibiting ATP synthase (22, 87), collapsing Δψm (41, 50, 52, 62), or inhibiting the Na+/K+ ATPase (87) triggers general fragmentation of the mitochondrial web due to cleavage of Opa1 (see below). Oxidative stress induced by hyperglycemia (25–50 m_M_) fragments the mitochondria in cardiac cells (124, 125) and pancreatic β-cells (9). Direct application of hydrogen peroxide is associated with a similar architecture phenotype (60). In an animal model of Alzheimer disease (116, 117) and a culture model of Parkinson disease (17), mitochondrial architecture was fragmented and the relative mitochondrial mass in APs was shown to be selectively increased (71).

Common to the above observations is a stress-induced mitochondrial damage, parallel to fragmentation, and a selective increase of mitochondrial localization in APs. This raises the possibility that mitochondrial fragmentation, which can be induced by various insults, is a common stress response that is principally required to segregate and eliminate dysfunctional mitochondria from the web.

The Dark Side of Excessive and Unbalanced Fission

The above view of fission as a critical process to mitochondrial homeostasis is in accordance with clinical and experimental data testing the role of fission under control conditions. Drp1, a profission protein, is essential for dendritic spine formation during the embryonic period (42). Its mutated form causes fatal encephalopathy in the newborn (118). In neural cultures, Drp1 loss-of-function is associated with reduction in spine mass and altered neural activity (8, 53, 55). Altered respiration was reported in HeLa cells transfected with Drp1 shRNA (7). Altered glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, which is dependent on increased respiration, was reported in pancreatic β cells treated with Drp1 shRNA (110).

On the other hand, excessive and unbalanced fission under a variety of metabolic insults has deleterious effects in a variety of tissues:

Cardiac and skeletal myocytes

Knockdown of Drp1 reduces significantly hyperglycemia-induced apoptosis in H2c9 (124) and HL-1 cardiac cells (125) and prevents ROS formation under increased glucose levels. Knockdown of Drp1 (79) prevents ischemia/reperfusion-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and is associated with reduced cell death in HL-1 cells following ischemia/reperfusion insult. In HL-1 cells, enhancement of autophagy by overexpressing ATG5 protects against Bnip3-mediated cell death, whereas inhibition of autophagy by ATG5K130R enhances cell death (37). These findings suggest a case wherein forcing mitochondria to the fusion state or eliminating mitochondria by autophagy, both have protective effects.

Treatment of adult murine cardiomyocytes with mitochondrial division inhibitor-1 (mdivi1), a pharmacological inhibitor of Drp1, reduces cell death and inhibits mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening after simulated ischemia/reperfusion injury. In vivo treatment with mdivi1 reduces myocardial infarct size in mice subject to coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion (79).

Inhibition of mitochondrial fission during myoblast differentiation is critical for the development of the ramified mitochondrial reticulum in adult myocytes (20). Romanello et al recently suggested that fragmentation of the mitochondrial network triggers the activation of the proteasome-ubiquitin system and the autophagy-lysosome axis, two key players in muscle atrophy (91). In starved mice, knockdown of Fis1 inhibits the activation of MuRF-1 and Atrogin-1 [key genes related to muscle atrophy (94)], results in retained muscle and mitochondrial mass, prevents mitochondrial fragmentation, and decreases autophagy (91). Overexpression of the dominant negative form of Drp1 (Drp1K38A) causes a similar phenotype in muscle with reduced levels of Fis1, even when it is cotransfected with FoxO3, a transcription factor that stimulates mitophagy and remodels the mitochondrial network in atrophying fibers. These results suggest that prevention of fragmentation plays a key role in starvation-induced muscle atrophy. It would be of interest to determine whether overexpression of Opa1 is equivalent to the protective effect of fission inhibition, given its inhibitory effect on autophagy (110), increased fusion rate (57), and its ambiguous effect on mitochondrial architecture as described earlier. In skeletal myocytes, both fusion and fission proteins are induced following exercise. This induction is blunted in type 2 diabetic patients, which makes this experiment physiologically relevant (11, 23, 38).

Pancreatic β-cells

In pancreatic β-cells, exposure to high glucose and fatty acids (also termed glucolipotoxicity) leads to fragmentation of mitochondrial architecture (70). In a type 2 diabetes animal model (ZDF rats), this sequence of events preceded the onset of diabetes (9). We recently showed that knockdown of Fis1 in β-cells prevents the glucolipotoxicity-induced recruitment of Drp1 to mitochondria and restores the ramified mitochondrial architecture as well as the exchange of mitochondrial contents through fusion events. Fis1 knockdown also reduced the level of cell death that is associated with glucolipotoxicity (70). In INS1 and primary β-cells, overexpression of hFis1 or dominant-negative Drp1 reduces both mitochondrial mass and cellular ATP levels by ∼25% and, as a consequence, impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (83). Although ATP is a critical signal for insulin secretion in β-cells, the excessive mitophagy seems to be protective, despite the decrease in mitochondrial mass and overall potential for ATP production. AP formation is increased in β-cells under high-fat diet and prediabetic conditions (26). Mice lacking Atg7 in β-cells show decreased insulin secretion, morphological and functional abnormalities, and faster onset of diabetes under high-fat diet (26, 46).

Neurons

Excessive fragmentation is associated with several chronic and acute neuropathological conditions. In Alzheimer disease, immunoblot analysis of brain tissue reveals that levels of Opa1, Mfn1, and Mfn2 are significantly reduced, whereas levels of Fis1 are significantly increased. Oligomeric amyloid-beta–derived diffusible ligands induce mitochondrial fragmentation as well as mitophagy-mediated reduction in mitochondrial density in the neuronal processes, subsequently leading to loss of dendritic spines (12, 116). In a culture model of Huntington disease, cytotoxicity induced by expanded polyglutamine tracts is mediated, at least in part, by excessive mitochondrial fission (115). Mutations in PINK1 cause autosomal recessive Parkinson disease. These pathogenic mutations also cause a defect in mitochondrial dynamics that can be reversed by the mitochondrial fission inhibitor, mdivi-1 (16), or by overexpressing the dominant negative form of Drp1 (17). In a different model of neuronal cell death, mitochondrial fission was shown to be an early event in ischemic stroke in vivo and in nitric oxide-induced oxidative stress, two conditions that are associated with neural death. In these models, inhibition of fission is associated with neural protection (5, 74). In a glaucoma model, exposure of differentiated retinal ganglion cells (RGC5) to elevated hydrostatic pressure results in mitochondrial fragmentation and decreased ATP (45).

Stem cells

Todd et al. reported recently a novel connection between mitochondrial morphology and homeostasis of mouse embryonic stem cells (108). Knockdown of growth factor erv1-like (Gfer) in embryonic stem cells leads to decreased embryoid body formation, elevated Drp1 levels, and increased mitochondrial fragmentation and mitophagy.

Mitochondrial Fusion—A Selective Rescue Mechanism

As stated earlier, mitochondrial fusion allows diffusion of matrix and membrane components between the two fusion mates (matrix components at a faster rate than the membrane ones). This may serve as a complementary “rescue” mechanism or a first line of defense from autophagy for damaged mitochondria. Thus, fusion may recruit dysfunctional mitochondria into the active pool, whereas autophagy targets depolarized mitochondria for digestion and elimination. This theoretically places mitophagy and fusion as competing fates of the depolarized mitochondria. The principal question is, therefore, what is the selective barrier that prevents any exchange between dysfunctional mitochondria and the intact ones in a manner that would otherwise diminish the efficient segregation of dysfunctional material by mitophagy.

Mitochondria fail to fuse when the Δψm is dissipated by a mitochondrial membrane uncoupler (41, 52, 62, 66–68). By labeling a group of mitochondria through laser photoconversion of matrix-targeted PAGFP and observing them over time, one can identify nonfusing mitochondria as those that do not share their photocoverted PAGFP. These mitochondria do not dilute the fluorescent signal and can be identified as the brightest mitochondria within the population. Nonfusing mitochondria are found even when numerous mitochondria with intact potential are in their close vicinity (110). Costaining with TMRE or with an anti-Opa1 antibody reveals that nonfusing mitochondria are relatively depolarized compared to average Δψm and their OPA1 content is reduced by ∼50% (110).

Opa1 is a protein with multiple isoforms that is localized in the inner membrane and in the intermembrane space of mitochondria (33, 78). However, it is also involved in outer mitochondrial membrane fusion, as Mfn1 is required for Opa1-mediated fusion (13, 35, 96). The biochemical mechanisms that link Opa1 processing to bioenergetic parameters have been described in different studies. In mammalian cells, the long isoforms (high molecular weight) of Opa1 undergo cleavage (or degradation) when depolarization is induced or ATP is depleted (25, 32, 40, 57, 101). As both long and short isoforms of Opa1 are required for mitochondrial fusion (101), a decrease in the driving force for ATP synthesis (i.e., Δψm depolarization) triggers mitochondrial fragmentation by processing and complete degradation of Opa1 isoforms. Taken together, these findings suggest that mitochondrial fusion is selective for polarized, active mitochondria and that this selectivity, in parallel with asymmetric fission events, determines the fate of the single mitochondrion (survival or degradation).

Selectivity of Mitochondrial Fusion Indirectly Supplies Mitochondria to the Mitophagic Pool

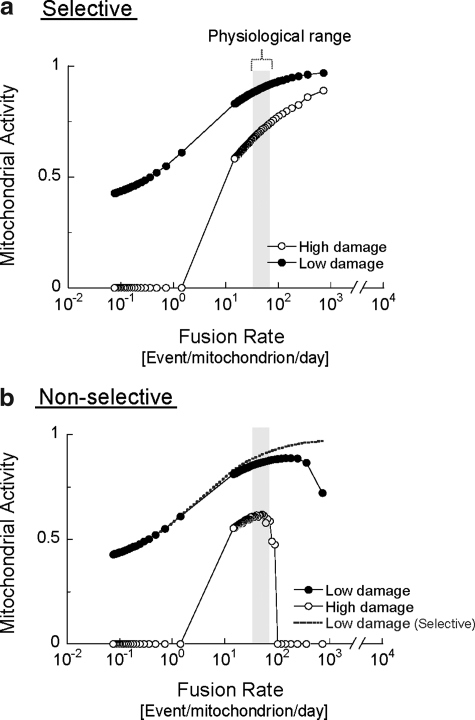

The selectivity of the fusion machinery makes fusion and mitophagy complementary processes, rather than competing ones. There are currently no experimental means to modify the degree of fusion selectivity or to accurately and stably change the rate of dynamic events over time. Recently, the contribution of selectivity and frequency of mitochondrial fusion to mitochondrial function was dissected by an analytical simulation (72) based on the kinetics of mitochondrial dynamics in INS1 β-cells (39, 110, 113). The computer-based simulation predicted mitochondrial activity under changing rates of mitochondrial dynamics and selectivity of the fusion machinery. The program simulated repetitive cycles of fusion and fission events in which intact and damaged mitochondrial contents were redistributed between fusion mates (see Fig. 2 legend for a more detailed description of the model). Redistribution had an impact upon mitochondrial function, thereby influencing the fate of each mitochondrion, that is, to be either destined for subsequent fusion or elimination by autophagy.

FIG. 2.

The in-silico model simulated a population of mitochondria, each containing 10 copies of mitochondrial functional components (representing the mitochondrial DNA, protein, and lipids required to maintain mitochondrial respiratory function). Each copy was classified as either ‘‘intact’’ or ‘‘damaged’’ (nonfunctional). Mitochondria were subjected to a steady rate of random damage that irreversibly converted random copies from intact to damaged. Accordingly, the number of nondamaged copies was used to deduct the level of mitochondrial activity (Δψm equivalent) on a 0–1 scale for each mitochondrion in the cell. The plotted cellular mitochondrial activity is generated by summing the activity of 300 mitochondria in each individual cell and then averaging the 100 different cells that are simulated in parallel. Autophagy targets mitochondria with activity level below 0.3, which was found in the solitary phase, as giant mitochondria fail to fuse (14, 77). Selective (a) and nonselective (b) fusion are compared under low and high (fourfold higher) damage rates. Note that, under increased rates of damage, mitochondrial activity is severely reduced if fusion is nonselective. Dotted line in (b) indicates the “selective” case of fusion under low-damage rate shown in (a). Gray bars indicate the physiological range of mitochondrial fusion in INS1 mitochondria under normal conditions. Data are modified from Mouli et al. (72).

Figure 2 shows the effect of changing the rates of fusion–fission frequency on mitochondrial activity under low- or high-damage rates. The illustration depicts the case of selective fusion (i.e., a mitochondrion can fuse only if its activity is above a certain threshold) and the case of nonselective fusion (fusion occurs independently of mitochondrial activity). Increasing the frequency of either selective or nonselective fusion results in improved mitochondrial activity. This positive relationship, however, is limited to a gap of fusion frequencies for the nonselective case and the gap narrows as the rate of damage increases.

In the case of selective fusion, segregation of the damaged mitochondrion from the fusing population prevents the migration of damaged components into more active mitochondria, but also, and equally important, leaves them available for autophagy. The simulation suggests that the beneficial value of this behavior becomes more apparent under high fusion rates. If fusion is nonselective at high rate of fusion, the duration spent in the solitary state is shortened and, thereby, the probability of autophagy of depolarized mitochondria is reduced (see figure legends) (14, 77, 102–107). Thus, autophagy is indirectly inhibited when most units are in the fused state, which results in the accumulation of mitochondria containing damaged content (hence reducing the overall activity score of the population). In the case wherein fusion is selective, high fusion frequencies do not prevent the removal of damaged mitochondria, because these mitochondria avoid fusion and are, therefore, constantly accessible to the autophagic machinery.

These findings emphasize the importance of selectivity of mitochondrial fusion not only as an intramitochondrial complementary route, but also as an isolation step preceding autophagy. This property could be viewed as a mechanism that allows the cell to compensate for high rates of mitochondrial damage by increasing fusion frequency without compromising the mitophagy of dysfunctional mitochondria.

Fusion, Fission, and Autophagy as a Bioenergetic Quality Control Mechanism

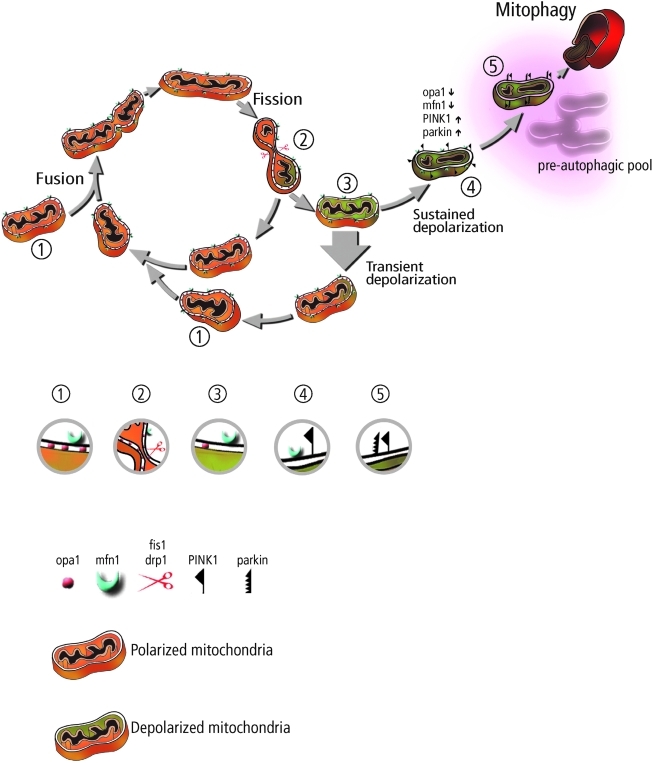

The observation that mitochondrial fusion is a Δψm-dependent process ensures that potentially dysfunctional organelles will avoid fusion, whereas intact mitochondria will benefit from sharing metabolites. Segregation of dysfunctional mitochondria from the fusing population results in the generation of small and depolarized mitochondria. The finding that autophagy targets depolarized mitochondria places autophagy at the end of the axis of quality control as a receiver of the segregation output. Figure 3 summarizes schematically how the combination of fusion, fission, and mitophagy act as a quality control mechanism. Importantly, this view suggests that the absolute rate of fusion and fission events per se (and not merely the balance between fusion and fission) determines the efficiency of the proposed quality control axis (in accordance with the data presented in Fig. 2). As fission frequency increases, the cumulative probability for the generation of dysfunctional units with sustained depolarization also increases. Under these circumstances, it is expected that the mass of damaged mitochondria that have been segregated from the fusing population and eliminated by mitophagy will be increased.

FIG. 3.

A schematic illustration of the mitochondrion's life cycle and the roles of mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy in the segregation of dysfunctional mitochondria. The mitochondrion cyclically shifts between a postfusion state (networked) that lasts tens of seconds and a postfission state (solitary) that can last tens of minutes. Following a fission event, the mitochondrion can depolarize and restore an intact potential (thick arrow) or remain in a depolarized level. Sustained Δψm depolarization triggers cleavage of Opa1, accumulation of PINK1/Parkin, and reduction in mitofusin capacity. The mitochondrion may spend several hours in this preautophagic state before targeted by the autophagic machinery. Protein compositions during various steps along these pathways are indicated by a relevant close-up, which are also labeled with numbers, corresponding to their location in the scheme. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

Mitochondrial Ubiquitin Ligase (PINK1/Parkin, MARCH5, and MULAN) as Molecular Regulators of Selective Fusion

Recent studies of the substrates of mitochondrial ubiquitin ligases, including MULAN, MARCH5, and Parkin, identify them as potential critical mediators that govern selective fusion and mitophagy. Parkin was shown to translocate selectively to energetically impaired mitochondria that were destined to autophagy independent of ROS production and morphology (75, 114). The translocation of Parkin is induced by PINK1 (29, 82). The latter undergoes voltage-dependent proteolysis in polarized mitochondria, but accumulates on depolarized mitochondria overtime (65, 76). This cascade of events accounts for the direct relationship between the level of Parkin on mitochondria and their membrane potential (75).

Studies in Drosophila report that upon recruitment to depolarized mitochondria, Parkin ubiquitinates Mfn (126). In mammalian cells, additional E3 ligases as MULAN and MARCH5 modify mitochondrial dynamics, and in the case of the latter, ubiquitinates Mfn1 (54, 84). Knockout of Parkin or MARCH5 leads to accumulation of Mfn or Mfn1 and to mitochondrial elongation (49, 84, 89, 123, 126). These results suggest that in the absence of PINK1/Parkin or MARCH5, damaged mitochondria are “rescued” by fusion instead of being removed by mitophagy. This compromises mitochondrial quality maintenance. In support of this view, knockdown of Mfn in Drosophila or Mfn1 in HeLa cells was protective from the knockdown of Parkin or MARCH5, respectively (84, 88, 89).

It should be mentioned that the effects of manipulations on PINK1/Parkin system had ambiguous effects on mitochondrial morphology. In Drosophila and COS7 cells, mutants for PINK1 and Parkin had elongated mitochondria (19, 81, 88, 123), whereas in other mammalian systems this manipulation resulted in fragmented phenotypes (17, 59, 93). In these studies, the compromised energetic state induced by PINK1/Parkin mutants could be rescued by preventing mitochondrial fragmentation, for example, by inhibition of fission. (16, 59, 81, 88, 93). The reasons for these conflicting reports remain to be fully elucidated, but, thus far, both technical factors (59) and tissue-specific differences may contribute.

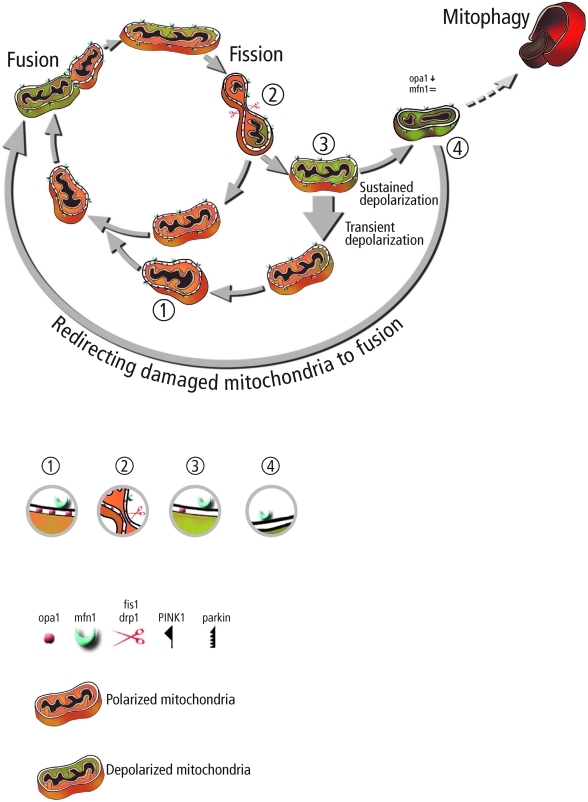

We hypothesize that the reduction in the rate of ubiquitination is finally associated with decreased mitophagy and an increase in unselective fusion (fusion between damaged and metabolically intact mitochondria). Figure 4 illustrates schematically this hypothesis under PINK1/Parkin KO. Under these conditions, mitophagy rate is decreased and damaged mitochondria can reengage (at least to some extent) in fusion events. In a very recent study, Tanaka et al. showed that upon membrane depolarization Parkin mediates selectively the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of Mfn1 and Mfn2 by the AAA+ ATPase, p97 (106a). This may provide a mechanism for selective fusion and the segregation of depolarized mitochondria prior to autophagy. Following fission, Parkin prevents or delays refusion of depolarized mitochondria by the elimination of mitofusins and in parallel triggers the accumulation of proteins that facilitate mitophagy. This study also finds that in the absence of fission, Parkin accumulation and mitofusin degradation alone are insufficient to induce mitophagy.

FIG. 4.

Potential consequences of reduction in the content of PINK1/Parkin accumulation. Reduction in PINK1/Parkin results in decreased product for mitophagy (dashed arrow) and accumulation of mitofusin on damaged mitochondria. The accumulation of mitofusin on damaged mitochondria allows them to reengage in fusion events despite their deprived energetic state, leading to incorporation of potentially toxic material into the mitochondrial pool. Protein composition at selected steps along the path is illustrated beneath in corresponding numbers 1–4. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

Abbreviations Used

AP

autophagosome

ATG

autophagy-related genes

Bnip3

member of the BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kd-interacting protein (BNIP) family

COS7

cell line derived from kidney cells of the African green monkey

DRP1

dynamin-related protein 1

EM

electron microscope

ER

endoplasmic reticulum

FIS1

fission protein 1

FoxO3

a transcription factor-stimulating mitophagy

Gfer

growth factor erv-like

GFP

green fluorescent protein

H2c9

cardiac cell line

HeLa

cell line derived from human cervical cancer

HL-1

cardiac cell line

INS1

cell line derived from rat β-cells insulinoma

KO

knockout

LC3

light chain 3

MARCH5

mitochondrial ubiquitin ligase

mdivi1

mitochondrial division inhibitor-1

Mfn

mitofusin

mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

mtPA-GFP

matrix-targeted photoactivatable GFP

MULAN

mitochondrial ubiquitin ligase

MuRF-1

muscle RING-finger protein-1

OPA1

gene encoding a dynamin-related mitochondrial protein causing autosomal dominant optic atrophy

Pink1

PTEN-induced Kinase 1, a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein that tags mitochondria for mitophagy

RGC5

retinal ganglion cell line

ROS

reactive oxygen species

shRNA

small-hairpin RNA

siRNA

small-interfering RNA

TMRE

tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester perchlorate, a mitochondrial-specific membrane potential-dependent dye

ZDF

Zucker diabetic fatty

Δψm

mitochondrial membrane potential

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Drs. Marc Liesa, Linsey Stiles, and Dani Dagan for helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. The authors thank Mrs. Erga Rivis for excellent technical support in producing the schematic illustrations.

References

- 1.Amchenkova AA, et al. Coupling membranes as energy-transmitting cables. I. Filamentous mitochondria in fibroblasts and mitochondrial clusters in cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:481–495. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aon MA. Cortassa S. O'Rourke B. Percolation and criticality in a mitochondrial network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4447–4452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307156101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arimura S. Yamamoto J. Aida GP. Nakazono M. Tsutsumi N. Frequent fusion and fission of plant mitochondria with unequal nucleoid distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7805–7808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401077101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnoult D. Rismanchi N. Grodet A. Roberts RG. Seeburg DP. Estaquier J. Sheng M. Blackstone C. Bax/Bak-dependent release of DDP/TIMM8a promotes Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission and mitoptosis during programmed cell death. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2112–2118. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barsoum MJ. Yuan H. Gerencser AA. Liot G. Kushnareva Y. Graber S. Kovacs I. Lee WD. Waggoner J. Cui J. White AD. Bossy B. Martinou JC. Youle RJ. Lipton SA. Ellisman MH. Perkins GA. Bossy-Wetzel E. Nitric oxide-induced mitochondrial fission is regulated by dynamin-related GTPases in neurons. EMBO J. 2006;25:3900–3911. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beau I. Esclatine A. Codogno P. Lost to translation: when autophagy targets mature ribosomes. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benard G. Bellance N. James D. Parrone P. Fernandez H. Letellier T. Rossignol R. Mitochondrial bioenergetics and structural network organization. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:838–848. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berman SB. Chen YB. Qi B. McCaffery JM. Rucker EB., 3rd Goebbels S. Nave KA. Arnold BA. Jonas EA. Pineda FJ. Hardwick JM. Bcl-x L increases mitochondrial fission, fusion, and biomass in neurons. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:707–719. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bindokas VP. Kuznetsov A. Sreenan S. Polonsky KS. Roe MW. Philipson LH. Visualizing superoxide production in normal and diabetic rat islets of Langerhans. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9796–9801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206913200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busch KB. Bereiter-Hahn J. Wittig I. Schagger H. Jendrach M. Mitochondrial dynamics generate equal distribution but patchwork localization of respiratory Complex I. Mol Membr Biol. 2006;23:509–520. doi: 10.1080/09687860600877292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cartoni R. Leger B. Hock MB. Praz M. Crettenand A. Pich S. Ziltener JL. Luthi F. Deriaz O. Zorzano A. Gobelet C. Kralli A. Russell AP. Mitofusins 1/2 and ERRalpha expression are increased in human skeletal muscle after physical exercise. J Physiol. 2005;567:349–358. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho DH. Nakamura T. Fang J. Cieplak P. Godzik A. Gu Z. Lipton SA. S-nitrosylation of Drp1 mediates beta-amyloid-related mitochondrial fission and neuronal injury. Science. 2009;324:102–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1171091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cipolat S. Martins de Brito O. Dal Zilio B. Scorrano L. OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15927–15932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407043101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman R. Silbermann M. Gershon D. Reznick AZ. Giant mitochondria in the myocardium of aging and endurance-trained mice. Gerontology. 1987;33:34–39. doi: 10.1159/000212851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crompton M. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem J. 1999;341(Pt 2):233–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui M. Tang X. Christian WV. Yoon Y. Tieu K. Perturbations in mitochondrial dynamics induced by human mutant PINK1 can be rescued by the mitochondrial division inhibitor mdivi-1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11740–11752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dagda RK. Cherra SJ., 3rd Kulich SM. Tandon A. Park D. Chu CT. Loss of PINK1 function promotes mitophagy through effects on oxidative stress and mitochondrial fission. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13843–13855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808515200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Brito OM. Scorrano L. An intimate liaison: spatial organization of the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria relationship. EMBO J. 2010;29:2715–2723. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng H. Dodson MW. Huang H. Guo M. The Parkinson's disease genes pink1 and Parkin promote mitochondrial fission and/or inhibit fusion in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14503–14508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803998105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Palma C. Falcone S. Pisoni S. Cipolat S. Panzeri C. Pambianco S. Pisconti A. Allevi R. Bassi MT. Cossu G. Pozzan T. Moncada S. Scorrano L. Brunelli S. Clementi E. Nitric oxide inhibition of Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission is critical for myogenic differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1684–1696. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devi L. Prabhu BM. Galati DF. Avadhani NG. Anandatheerthavarada HK. Accumulation of amyloid precursor protein in the mitochondrial import channels of human Alzheimer's disease brain is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9057–9068. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1469-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Vos KJ. Allan VJ. Grierson AJ. Sheetz MP. Mitochondrial function and actin regulate dynamin-related protein 1-dependent mitochondrial fission. Curr Biol. 2005;15:678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding H. Jiang N. Liu H. Liu X. Liu D. Zhao F. Wen L. Liu S. Ji LL. Zhang Y. Response of mitochondrial fusion and fission protein gene expression to exercise in rat skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn WA., Jr. Cregg JM. Kiel JA. van der Klei IJ. Oku M. Sakai Y. Sibirny AA. Stasyk OV. Veenhuis M. Pexophagy: the selective autophagy of peroxisomes. Autophagy. 2005;1:75–83. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duvezin-Caubet S. Jagasia R. Wagener J. Hofmann S. Trifunovic A. Hansson A. Chomyn A. Bauer MF. Attardi G. Larsson NG. Neupert W. Reichert AS. Proteolytic processing of OPA1 links mitochondrial dysfunction to alterations in mitochondrial morphology. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37972–37979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebato C. Uchida T. Arakawa M. Komatsu M. Ueno T. Komiya K. Azuma K. Hirose T. Tanaka K. Kominami E. Kawamori R. Fujitani Y. Watada H. Autophagy is important in islet homeostasis and compensatory increase of beta cell mass in response to high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 2008;8:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elmore SP. Qian T. Grissom SF. Lemasters JJ. The mitochondrial permeability transition initiates autophagy in rat hepatocytes. FASEB J. 2001;15:2286–2287. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0206fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frieden M. James D. Castelbou C. Danckaert A. Martinou JC. Demaurex N. Ca(2+) homeostasis during mitochondrial fragmentation and perinuclear clustering induced by hFis1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22704–22714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geisler S. Holmstrom KM. Skujat D. Fiesel FC. Rothfuss OC. Kahle PJ. Springer W. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:119–131. doi: 10.1038/ncb2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomes LC. Scorrano L. High levels of Fis1, a pro-fission mitochondrial protein, trigger autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:860–866. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.05.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottlieb RA. Carreira RS. Autophagy in health and disease: V. Mitophagy as a way of life. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C203–C210. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00097.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griparic L. Kanazawa T. van der Bliek AM. Regulation of the mitochondrial dynamin-like protein Opa1 by proteolytic cleavage. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:757–764. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griparic L. van der Wel NN. Orozco IJ. Peters PJ. van der Bliek AM. Loss of the intermembrane space protein Mgm1/OPA1 induces swelling and localized constrictions along the lengths of mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18792–18798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400920200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grivennikova VG. Kareyeva AV. Vinogradov AD. What are the sources of hydrogen peroxide production by heart mitochondria? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guillery O. Malka F. Frachon P. Milea D. Rojo M. Lombes A. Modulation of mitochondrial morphology by bioenergetics defects in primary human fibroblasts. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008;18:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hailey DW. Rambold AS. Satpute-Krishnan P. Mitra K. Sougrat R. Kim PK. Lippincott-Schwartz J. Mitochondria supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation. Cell. 2010;141:656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamacher-Brady A. Brady NR. Logue SE. Sayen MR. Jinno M. Kirshenbaum LA. Gottlieb RA. Gustafsson AB. Response to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury involves Bnip3 and autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:146–157. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernandez-Alvarez MI. Thabit H. Burns N. Shah S. Brema I. Hatunic M. Finucane F. Liesa M. Chiellini C. Naon D. Zorzano A. Nolan JJ. Subjects with early-onset type 2 diabetes show defective activation of the skeletal muscle PGC-1{alpha}/Mitofusin-2 regulatory pathway in response to physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:645–651. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hyde BB. Twig G. Shirihai OS. Organellar vs cellular control of mitochondrial dynamics. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishihara N. Fujita Y. Oka T. Mihara K. Regulation of mitochondrial morphology through proteolytic cleavage of OPA1. EMBO J. 2006;25:2966–2977. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishihara N. Jofuku A. Eura Y. Mihara K. Regulation of mitochondrial morphology by membrane potential, and DRP1-dependent division and FZO1-dependent fusion reaction in mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:891–898. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishihara N. Nomura M. Jofuku A. Kato H. Suzuki SO. Masuda K. Otera H. Nakanishi Y. Nonaka I. Goto Y. Taguchi N. Morinaga H. Maeda M. Takayanagi R. Yokota S. Mihara K. Mitochondrial fission factor Drp1 is essential for embryonic development and synapse formation in mice. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:958–966. doi: 10.1038/ncb1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jakobs S. High resolution imaging of live mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:561–575. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jakobs S. Schauss AC. Hell SW. Photoconversion of matrix targeted GFP enables analysis of continuity and intermixing of the mitochondrial lumen. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:194–200. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ju WK. Liu Q. Kim KY. Crowston JG. Lindsey JD. Agarwal N. Ellisman MH. Perkins GA. Weinreb RN. Elevated hydrostatic pressure triggers mitochondrial fission and decreases cellular ATP in differentiated RGC-5 cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2145–2151. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jung HS. Chung KW. Won Kim J. Kim J. Komatsu M. Tanaka K. Nguyen YH. Kang TM. Yoon KH. Kim JW. Jeong YT. Han MS. Lee MK. Kim KW. Shin J. Lee MS. Loss of autophagy diminishes pancreatic beta cell mass and function with resultant hyperglycemia. Cell Metab. 2008;8:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karbowski M. Arnoult D. Chen H. Chan DC. Smith CL. Youle RJ. Quantitation of mitochondrial dynamics by photolabeling of individual organelles shows that mitochondrial fusion is blocked during the Bax activation phase of apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:493–499. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karbowski M. Jeong SY. Youle RJ. Endophilin B1 is required for the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:1027–1039. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karbowski M. Neutzner A. Youle RJ. The mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH5 is required for Drp1 dependent mitochondrial division. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:71–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kennedy ED. Maechler P. Wollheim CB. Effects of depletion of mitochondrial DNA in metabolism secretion coupling in INS-1 cells. Diabetes. 1998;47:374–380. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee YJ. Jeong SY. Karbowski M. Smith CL. Youle RJ. Roles of the mammalian mitochondrial fission and fusion mediators Fis1, Drp1, and Opa1 in apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5001–5011. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Legros F. Lombes A. Frachon P. Rojo M. Mitochondrial fusion in human cells is efficient, requires the inner membrane potential, and is mediated by mitofusins. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4343–4354. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li H. Chen Y. Jones AF. Sanger RH. Collis LP. Flannery R. McNay EC. Yu T. Schwarzenbacher R. Bossy B. Bossy-Wetzel E. Bennett MV. Pypaert M. Hickman JA. Smith PJ. Hardwick JM. Jonas EA. Bcl-xL induces Drp1-dependent synapse formation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2169–2174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711647105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li W. Bengtson MH. Ulbrich A. Matsuda A. Reddy VA. Orth A. Chanda SK. Batalov S. Joazeiro CA. Genome-wide and functional annotation of human E3 ubiquitin ligases identifies MULAN, a mitochondrial E3 that regulates the organelle's dynamics and signaling. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Z. Okamoto K. Hayashi Y. Sheng M. The importance of dendritic mitochondria in the morphogenesis and plasticity of spines and synapses. Cell. 2004;119:873–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liesa M. Palacin M. Zorzano A. Mitochondrial dynamics in mammalian health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:799–845. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu X. Weaver D. Shirihai O. Hajnoczky G. Mitochondrial “kiss-and-run”: interplay between mitochondrial motility and fusion-fission dynamics. EMBO J. 2009;28:3074–3089. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Loew LM. Tuft RA. Carrington W. Fay FS. Imaging in five dimensions: time-dependent membrane potentials in individual mitochondria. Biophys J. 1993;65:2396–2407. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81318-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lutz AK. Exner N. Fett ME. Schlehe JS. Kloos K. Lammermann K. Brunner B. Kurz-Drexler A. Vogel F. Reichert AS. Bouman L. Vogt-Weisenhorn D. Wurst W. Tatzelt J. Haass C. Winklhofer KF. Loss of Parkin or PINK1 function increases Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22938–22951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maechler P. Jornot L. Wollheim CB. Hydrogen peroxide alters mitochondrial activation and insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27905–27913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malena A. Loro E. Di Re M. Holt IJ. Vergani L. Inhibition of mitochondrial fission favours mutant over wild-type mitochondrial DNA. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3407–3416. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malka F. Guillery O. Cifuentes-Diaz C. Guillou E. Belenguer P. Lombes A. Rojo M. Separate fusion of outer and inner mitochondrial membranes. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:853–859. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manczak M. Anekonda TS. Henson E. Park BS. Quinn J. Reddy PH. Mitochondria are a direct site of A beta accumulation in Alzheimer's disease neurons: implications for free radical generation and oxidative damage in disease progression. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1437–1449. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mannella CA. Structure and dynamics of the mitochondrial inner membrane cristae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matsuda N. Sato S. Shiba K. Okatsu K. Saisho K. Gautier CA. Sou YS. Saiki S. Kawajiri S. Sato F. Kimura M. Komatsu M. Hattori N. Tanaka K. PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:211–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mattenberger Y. James DI. Martinou JC. Fusion of mitochondria in mammalian cells is dependent on the mitochondrial inner membrane potential and independent of microtubules or actin. FEBS Lett. 2003;538:53–59. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meeusen S. DeVay R. Block J. Cassidy-Stone A. Wayson S. McCaffery JM. Nunnari J. Mitochondrial inner-membrane fusion and crista maintenance requires the dynamin-related GTPase Mgm1. Cell. 2006;127:383–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meeusen SL. Nunnari J. How mitochondria fuse. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Menzies RA. Gold PH. The turnover of mitochondria in a variety of tissues of young adult and aged rats. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:2425–2429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Molina AJ. Wikstrom JD. Stiles L. Las G. Mohamed H. Elorza A. Walzer G. Twig G. Katz S. Corkey BE. Shirihai OS. Mitochondrial networking protects beta cells from nutrient induced apoptosis. Diabetes. 2009;58:2303–2315. doi: 10.2337/db07-1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moreira PI. Siedlak SL. Wang X. Santos MS. Oliveira CR. Tabaton M. Nunomura A. Szweda LI. Aliev G. Smith MA. Zhu X. Perry G. Increased autophagic degradation of mitochondria in Alzheimer disease. Autophagy. 2007;3:614–615. doi: 10.4161/auto.4872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mouli PK. Twig G. Shirihai OS. Frequency and selectivity of mitochondrial fusion are key to its quality maintenance function. Biophys J. 2009;96:3509–3518. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nakada K. Inoue K. Ono T. Isobe K. Ogura A. Goto YI. Nonaka I. Hayashi JI. Inter-mitochondrial complementation: mitochondria-specific system preventing mice from expression of disease phenotypes by mutant mtDNA. Nat Med. 2001;7:934–940. doi: 10.1038/90976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nakamura T. Cieplak P. Cho DH. Godzik A. Lipton SA. S-nitrosylation of Drp1 links excessive mitochondrial fission to neuronal injury in neurodegeneration. Mitochondrion. 2010;10:573–578. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Narendra D. Tanaka A. Suen DF. Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Narendra DP. Jin SM. Tanaka A. Suen DF. Gautier CA. Shen J. Cookson MR. Youle RJ. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Navratil M. Terman A. Arriaga EA. Giant mitochondria do not fuse and exchange their contents with normal mitochondria. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Olichon A. Baricault L. Gas N. Guillou E. Valette A. Belenguer P. Lenaers G. Loss of OPA1 perturbates the mitochondrial inner membrane structure and integrity, leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7743–7746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ong SB. Subrayan S. Lim SY. Yellon DM. Davidson SM. Hausenloy DJ. Inhibiting mitochondrial fission protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2010;121:2012–2022. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.906610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ono T. Isobe K. Nakada K. Hayashi JI. Human cells are protected from mitochondrial dysfunction by complementation of DNA products in fused mitochondria. Nat Genet. 2001;28:272–275. doi: 10.1038/90116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Park J. Lee G. Chung J. The PINK1-Parkin pathway is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial remodeling process. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Park J. Lee SB. Lee S. Kim Y. Song S. Kim S. Bae E. Kim J. Shong M. Kim JM. Chung J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Drosophila PINK1 mutants is complemented by Parkin. Nature. 2006;441:1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/nature04788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Park KS. Wiederkehr A. Kirkpatrick C. Mattenberger Y. Martinou JC. Marchetti P. Demaurex N. Wollheim CB. Selective actions of mitochondrial fission/fusion genes on metabolism-secretion coupling in insulin-releasing cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33347–33356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806251200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Park YY. Lee S. Karbowski M. Neutzner A. Youle RJ. Cho H. Loss of MARCH5 mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin ligase induces cellular senescence through dynamin-related protein 1 and mitofusin 1. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:619–626. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Parone PA. Da Cruz S. Tondera D. Mattenberger Y. James DI. Maechler P. Barja F. Martinou JC. Preventing mitochondrial fission impairs mitochondrial function and leads to loss of mitochondrial DNA. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Partikian A. Olveczky B. Swaminathan R. Li Y. Verkman AS. Rapid diffusion of green fluorescent protein in the mitochondrial matrix. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:821–829. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pletjushkina OY. Lyamzaev KG. Popova EN. Nepryakhina OK. Ivanova OY. Domnina LV. Chernyak BV. Skulachev VP. Effect of oxidative stress on dynamics of mitochondrial reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Poole AC. Thomas RE. Andrews LA. McBride HM. Whitworth AJ. Pallanck LJ. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1638–1643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709336105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Poole AC. Thomas RE. Yu S. Vincow ES. Pallanck L. The mitochondrial fusion-promoting factor mitofusin is a substrate of the PINK1/Parkin pathway. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Priault M. Salin B. Schaeffer J. Vallette FM. di Rago JP. Martinou JC. Impairing the bioenergetic status and the biogenesis of mitochondria triggers mitophagy in yeast. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1613–1621. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Romanello V. Guadagnin E. Gomes L. Roder I. Sandri C. Petersen Y. Milan G. Masiero E. Del Piccolo P. Foretz M. Scorrano L. Rudolf R. Sandri M. Mitochondrial fission and remodelling contributes to muscle atrophy. EMBO J. 2010;29:1774–1785. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sakai Y. Oku M. van der Klei IJ. Kiel JA. Pexophagy: autophagic degradation of peroxisomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1767–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sandebring A. Thomas KJ. Beilina A. van der Brug M. Cleland MM. Ahmad R. Miller DW. Zambrano I. Cowburn RF. Behbahani H. Cedazo-Minguez A. Cookson MR. Mitochondrial alterations in PINK1 deficient cells are influenced by calcineurin-dependent dephosphorylation of dynamin-related protein 1. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sandri M. Sandri C. Gilbert A. Skurk C. Calabria E. Picard A. Walsh K. Schiaffino S. Lecker SH. Goldberg AL. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell. 2004;117:399–412. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00400-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schon EA. Gilkerson RW. Functional complementation of mitochondrial DNAs: mobilizing mitochondrial genetics against dysfunction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:245–249. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sesaki H. Southard SM. Yaffe MP. Jensen RE. Mgm1p, a dynamin-related GTPase, is essential for fusion of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2342–2356. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shaw JM. Nunnari J. Mitochondrial dynamics and division in budding yeast. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:178–184. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02246-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shitara H. Kaneda H. Sato A. Inoue K. Ogura A. Yonekawa H. Hayashi JI. Selective and continuous elimination of mitochondria microinjected into mouse eggs from spermatids, but not from liver cells, occurs throughout embryogenesis. Genetics. 2000;156:1277–1284. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.3.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Simmons RA. Suponitsky-Kroyter I. Selak MA. Progressive accumulation of mitochondrial DNA mutations and decline in mitochondrial function lead to beta-cell failure. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28785–28791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Skulachev VP. Mitochondrial filaments and clusters as intracellular power-transmitting cables. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Song Z. Chen H. Fiket M. Alexander C. Chan DC. OPA1 processing controls mitochondrial fusion and is regulated by mRNA splicing, membrane potential, and Yme1L. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:749–755. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stroikin Y. Dalen H. Loof S. Terman A. Inhibition of autophagy with 3-methyladenine results in impaired turnover of lysosomes and accumulation of lipofuscin-like material. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83:583–590. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Suen DF. Narendra DP. Tanaka A. Manfredi G. Youle RJ. Parkin overexpression selects against a deleterious mtDNA mutation in heteroplasmic cybrid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11835–11840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914569107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Szegezdi E. Macdonald DC. Ni Chonghaile T. Gupta S. Samali A. Bcl-2 family on guard at the ER. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C941–C953. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00612.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Takahashi Y. Coppola D. Matsushita N. Cualing HD. Sun M. Sato Y. Liang C. Jung JU. Cheng JQ. Mule JJ. Pledger WJ. Wang HG. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ncb1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Takano-Ohmuro H. Mukaida M. Kominami E. Morioka K. Autophagy in embryonic erythroid cells: its role in maturation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79:759–764. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106a.Tanaka A. Cleland MM. Xu S. Narendra DP. Suen DF. Karbowski M. Youle RJ. Proteasome and p97 mediate mitophagy and degradation of mitofusins induced by Parkin. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1367–1380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tanaka M. Kovalenko SA. Gong JS. Borgeld HJ. Katsumata K. Hayakawa M. Yoneda M. Ozawa T. Accumulation of deletions and point mutations in mitochondrial genome in degenerative diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;786:102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb39055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Todd LR. Damin MN. Gomathinayagam R. Horn SR. Means AR. Sankar U. Growth factor erv1-like modulates Drp1 to preserve mitochondrial dynamics and function in mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1225–1236. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-11-0937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tondera D. Grandemange S. Jourdain A. Karbowski M. Mattenberger Y. Herzig S. Da Cruz S. Clerc P. Raschke I. Merkwirth C. Ehses S. Krause F. Chan DC. Alexander C. Bauer C. Youle R. Langer T. Martinou JC. SLP-2 is required for stress-induced mitochondrial hyperfusion. EMBO J. 2009;28:1589–1600. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Twig G. Elorza A. Molina AJ. Mohamed H. Wikstrom JD. Walzer G. Stiles L. Haigh SE. Katz S. Las G. Alroy J. Wu M. Py BF. Yuan J. Deeney JT. Corkey BE. Shirihai OS. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. 2008;27:433–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Twig G. Graf SA. Wikstrom JD. Mohamed H. Haigh SE. Elorza A. Deutsch M. Zurgil N. Reynolds N. Shirihai OS. Tagging and tracking individual networks within a complex mitochondrial web with photoactivatable GFP. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C176–C184. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00348.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Twig G. Hyde B. Shirihai OS. Mitochondrial fusion, fission and autophagy as a quality control axis: the bioenergetic view. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:1092–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Twig G. Liu X. Liesa M. Wikstrom JD. Molina AJ. Las G. Yaniv G. Hajnoczky G. Shirihai OS. Biophysical properties of mitochondrial fusion events in pancreatic {beta}-cells and cardiomyocytes unravel potential control mechanisms of its selectivity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C477–C487. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00427.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vives-Bauza C. Zhou C. Huang Y. Cui M. de Vries RL. Kim J. May J. Tocilescu MA. Liu W. Ko HS. Magrane J. Moore DJ. Dawson VL. Grailhe R. Dawson TM. Li C. Tieu K. Przedborski S. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:378–383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911187107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang H. Lim PJ. Karbowski M. Monteiro MJ. Effects of overexpression of huntingtin proteins on mitochondrial integrity. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:737–752. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang X. Su B. Lee HG. Li X. Perry G. Smith MA. Zhu X. Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9090–9103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang X. Su B. Siedlak SL. Moreira PI. Fujioka H. Wang Y. Casadesus G. Zhu X. Amyloid-beta overproduction causes abnormal mitochondrial dynamics via differential modulation of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19318–19323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804871105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Waterham HR. Koster J. van Roermund CW. Mooyer PA. Wanders RJ. Leonard JV. A lethal defect of mitochondrial and peroxisomal fission. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1736–1741. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Westermann B. Merging mitochondria matters: cellular role and molecular machinery of mitochondrial fusion. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:527–531. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.White KE. Davies VJ. Hogan VE. Piechota MJ. Nichols PP. Turnbull DM. Votruba M. OPA1 deficiency associated with increased autophagy in retinal ganglion cells in a murine model of dominant optic atrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2567–2571. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wikstrom JD. Katzman SM. Mohamed H. Twig G. Graf SA. Heart E. Molina AJ. Corkey BE. de Vargas LM. Danial NN. Collins S. Shirihai OS. Beta-cell mitochondria exhibit membrane potential heterogeneity that can be altered by stimulatory or toxic fuel levels. Diabetes. 2007;56:2569–2578. doi: 10.2337/db06-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wikstrom JD. Twig G. Shirihai OS. What can mitochondrial heterogeneity tell us about mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1914–1927. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yang Y. Ouyang Y. Yang L. Beal MF. McQuibban A. Vogel H. Lu B. Pink1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics through interaction with the fission/fusion machinery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7070–7075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711845105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yu T. Robotham JL. Yoon Y. Increased production of reactive oxygen species in hyperglycemic conditions requires dynamic change of mitochondrial morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2653–2658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511154103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yu T. Sheu SS. Robotham JL. Yoon Y. Mitochondrial fission mediates high glucose-induced cell death through elevated production of reactive oxygen species. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:341–351. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ziviani E. Tao RN. Whitworth AJ. Drosophila Parkin requires PINK1 for mitochondrial translocation and ubiquitinates mitofusin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5018–5023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913485107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]