FGF signaling in the developing endochondral skeleton (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Apr 27.

Published in final edited form as: Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005 Apr 1;16(2):205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.02.003

Abstract

Mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptors (Fgfrs) are the etiology of many craniosynostosis and chondrodysplasia syndromes in humans. The phenotypes associated with these human syndromes and the phenotypes resulting from targeted mutagenesis in the mouse have defined essential roles for FGF signaling in both endochondral and intramembranous bone development. In this review, I will focus on the role of FGF signaling in chondrocytes and osteoblasts and how FGFs regulate the growth and development of endochondral bone.

Keywords: FGF, Skeletal development, Craniosynostosis, Achondroplasia, Receptor tyrosine kinase

1. Human skeletal disease syndromes: the FGF connection

Fgfrs were known to be expressed in the developing skeleton. However, a functional link between FGF signaling and skeletal development was not appreciated until the discovery that achondroplasia (ACH), the most common form of skeletal dwarfism in humans, was caused by a missense mutation in Fgfr3 [1–5]. Following this initial discovery, a milder form of dwarfism, hypochondroplasia (HCH) [6,7], and a more severe form of dwarfism, thanatophoric dysplasia (TD) [3,8–10], were also found to result from mutations in Fgfr3.

In addition to the chondrodysplasia syndromes, many other human skeletal dysplasias have been attributed to mutations in Fgfrs 1, 2 and 3 [11–17]. These disorders have in common craniosynostosis (premature fusion of the cranial sutures) and variably other phenotypes that affect the appendicular skeleton and other organ systems. The craniosynostosis syndromes involving Fgfr2 include Apert syndrome (AS) [18], Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata [19], Crouzon syndrome (CS) [20–32], Pfeiffer syndrome (PS) [33–37,23,28,29], Jackson-Weiss syndrome (JWS) [22,23, 26] and a non-syndromic craniosynostosis (NSC) [38]. Recently a family has been described with a double mutation in Fgfr2 (S2521, A315S) that is associated with syndactyly but not craniosynostosis [39]. However, individually, these mutations are associated with low-penetrance craniosynostosis.

In addition to the single mutation in Fgfr1 (P252R) that causes Pfeiffer syndrome [40–42,29], a rare mutation has been identified that causes osteoglophonic dysplasia (OD), a disease characterized by craniosynostosis, prominent supraorbital ridge, and depressed nasal bridge, as well as the rhizomelic dwarfism and nonossifying bone lesions [43]. One patient has also been described with Jackson-Weiss syndrome and a P252R mutation in Fgfr1 (P252R) [44]. Loss of function mutations in Fgfr1 are associated with one form of Kalmann syndrome (KS), a disease that does not directly affect skeletal development [45].

Recently, a mutation in Fgfr3 (P250R) has been described that causes Muenke syndrome (MS), which is characterized by craniosynostosis and variably other skeletal and neurological phenotypes [38,46,47]. Another mutation in Fgfr3 (A391E) causes Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans, now referred to as crouzonodermoskeletal syndrome [48–52,24].

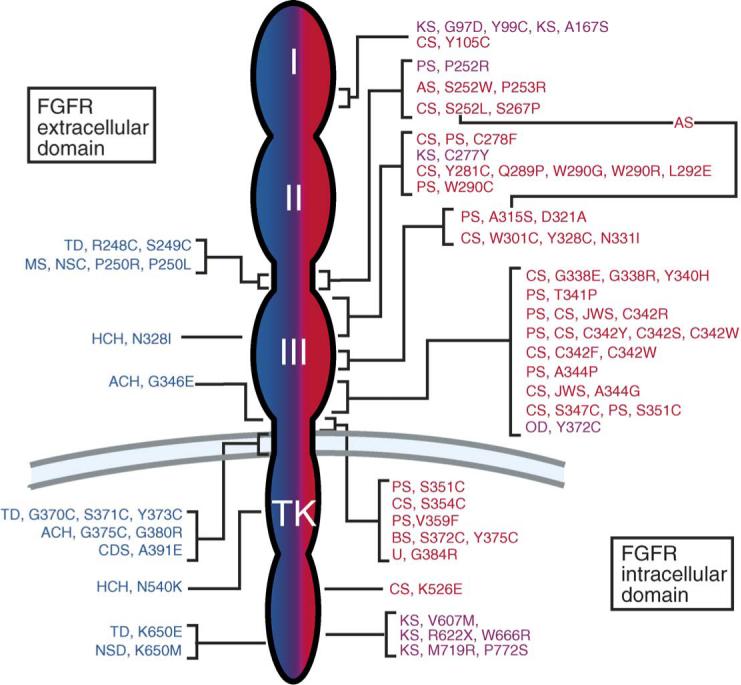

All of the skeletal disease syndromes are caused by autosomal dominant mutations and frequently arise sporadically. The mutations in Fgfrs are shown in Fig. 1. The genetics and pathophysiology of these diseases are discussed in the need to refer to article by Andrew Wilkie.

Fig. 1.

FGF receptor mutations in humans. Left (Blue): Mutations in FGFR3 – achondroplasia (ACH), thanatophoric dysplasia (TD), hypochondroplasia (HCH), crouzonodermoskeletal syndrome syndrome (Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans) (CDS), non-syndromic craniosynostosis (NSC), Muenke syndrome (MS). Right (Red): Mutations in FGFR2 – Crouzon syndrome (CS), Jackson-Weiss syndrome (JWS), Pfeiffer syndrome (PS), Apert syndrome (AS), Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata (BS), unclassified (U). The line connecting S252L and A315S indicates the double mutation found in patients with Apert syndrome-like syndactyly without craniosynostosis. Right (Pink): A single mutation in FGFR1 causes Pfeiffer syndrome (PS) and osteoglophonic dysplasia (OD). Multiple mutations in FGFR1 cause Kallmann syndrome (KS). The numbers represent the position of the mutant amino acid in the human coding sequence. Amino acids are abbreviated using standard single letter abbreviations (adapted from [16]).

2. Endochondral bone development

Endochondral ossification is responsible for the formation of the appendicular skeleton, facial bones, vertebrae and the medial clavicles. Appendicular skeletal development initiates shortly after the formation of the limb bud with the formation of a histologically identifiable mesenchymal condensation, marked by the expression of type II collagen and Sox9 [53–56]. This condensing mesenchyme forms an anlage for the endochondral skeleton and can either branch or segment to form individual skeletal elements [57,58].

Condensing mesenchyme gives rise to a highly proliferative population of cells. The centrally localized cells express type II collagen and will give rise to chondrocytes. The more peripherally localized cells transiently express type II collagen and then adopt an osteoblast fate characterized by the expression of alkaline phosphatase and eventually type I collagen [53].

As development progresses, the condensation elongates. Medially localized cells proliferate, while more distal cells form a slowly growing pool of reserve chondrocytes. Midway between the ends of this elongated cartilaginous template, chondrocytes exit the cell cycle, downregulate type II collagen expression and begin to differentiate into hypertrophic chondrocytes, characterized by the synthesis of high levels of type X collagen [59]. The process of chondrocyte hypertrophy is thought to contribute to the force driving bone elongation [60].

Developing and mature bone is highly vascularized, whereas cartilage is an avascular structure. The conversion of the cartilaginous template into bone involves several developmental events. An early and essential step in the formation of bone requires neovascularization of the avascular hypertrophic zone chondrocytes. Vascular invasion allows the influx of periosteal-derived osteoblast precursors and hematopoietic derived osteo(chondro)clasts. At this stage of development, distal hypertrophic chondrocytes begin to ossify while the extracellular cartilaginous matrix is degraded by matrix metalloproteases produced by the osteoclasts. Osteoblasts, osteoclasts and the newly developed vasculature form a center of ossification that propagates toward the distal ends of the nascent bone. This process converts cartilaginous matrix into trabecular bone. The trabecular ossification region (primary and secondary spongiosa) and chondrocytes at various stages of differentiation constitute a developmental structure called the epiphyseal growth plate. These well-demarcated zones of cells follow an elegant developmental program that extends through puberty and the closure of the growth plate [57,61–65].

Surrounding the growth plate is the perichondrium, a fibrous structure containing osteoprogenitor cells. Centrally, the perichondrium forms a structure called the bone collar (periosteum), the precursor of cortical bone [61]. The periosteum is a well-vascularized structure and contains precursor pools of cells that give rise to the mature osteoblasts that line the endosteal (inner) surface of cortical bone. As mineralization proceeds, osteoblasts become postmitotic (osteocytes) as they become embedded within cortical bone. A large number of signaling pathways are required to coordinate chondrogenesis and osteogenesis. This review will focus on the role of FGF signaling pathways in this process.

3. FGF and FGF receptor expression and signaling in condensing mesenchyme

The formation of the mesenchymal condensation is associated with changes in gene expression. Fgfr2, type II collagen and Sox9 are among the earliest genes upregulated in condensing mesenchyme [53–56,66]. Fgfr1 continues to be expressed in surrounding loose mesenchyme and is also expressed along with Fgfr2 in the periphery of the condensation [66–69].

The physiologic ligands that activate FGFRs in the mesenchymal condensation have been difficult to identify. Fgf9 is expressed within condensing mesenchyme early in development [70]. Fgf2, Fgf5, Fgf6 and Fgf7 expression has been observed in mesenchyme surrounding the condensation [71–75]. However, knockout mice lacking these FGFs have no apparent defects in skeletal development [76–78]. It is possible that a combination of these and other FGFs may constitute the complete FGF signal to the developing condensation.

The role of FGF signaling in condensing mesenchyme is poorly understood. In primary chondrocytes and in undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, FGF signaling pathways induce the expression of Sox9, an essential transcription factor for chondrocyte differentiation [79,55]. Additionally, FGFR3 signaling may enhance chondrocyte proliferation in the mesenchymal condensation, even though it is well established that FGFR3 limits chondrocyte proliferation in the mature growth plate [80,81]. Consistent with this, FGF2 and to a greater extent, FGF9 can stimulate proliferation of chondrocytes [82]. Defects in FGF signaling in the mesenchymal condensation can result in skeletal abnormalities. For example, in the case of Apert Syndrome, mutations in FGFR2 allow for inappropriate activation of FGFR2 in the mesenchymal condensation by mesenchymally expressed ligands, such as FGF7 and FGF10, that normally do not signal to this receptor [83,84]. Although ligand-binding specificity is also lost for epithelial forms of FGFR2, the recent identification of mutations within the mesenchymal-specific c exon of Fgfr2 (A315S) that allow binding to FGF10, suggests that the primary etiology of Apert syndrome results from inappropriate activation of the mesenchymal receptor [85,39]. The soft tissue and bony syndactyly characteristic of Apert syndrome suggests that the phenotype may originate at the mesenchymal condensation stage of development.

4. FGF and FGF receptor expression and signaling in endochondral bone

4.1. Fgf receptors expressed in developing bone

Shortly after formation of a mesenchymal condensation, Fgfr3 expression is activated in chondrocytes located in the central core of the mesenchymal condensation (Fig. 2) [86]. At this stage of development, overlap in expression may exist with Fgfr2 and Fgfr3. As the epiphyseal growth plate develops, Fgfr1 expression is upregulated as chondrocytes hypertrophy. Fgfr1 and Fgfr3 have very distinct domains of expression with little overlap; Fgfr3 is expressed in proliferating chondrocytes, whereas Fgfr1 is expressed in prehypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes [87,88,66]. This juxtaposition of FGFR1 and FGFR3 expression domains suggests unique functions. Expression of Fgfr3 in the reserve and proliferating zone suggests a direct role for FGFR3 in regulating chondrocyte proliferation and possibly differentiation [67,89,88]. In contrast, the expression of Fgfr1 in hypertrophic chondrocytes [67,66] suggests a role for FGFR1 in regulating cell survival, cell differentiation, extracellular matrix production and cell death. Interestingly, immunohistochemical localization of FGFR3 in costal cartilage identifies FGFR3 extracellular domains within the extracellular matrix of hypertrophic chondrocytes. This suggests that proteolytic processing could regulate the activity of FGFR3 and that the FGFR3 ectodomain could compete with FGFR1 for ligand-binding [90]. In mature bone, Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 continue to be expressed in osteoblasts. Interestingly, immunohistochemistry has also identified FGFR3 expression in mature osteoblasts and in osteocytes [86].

Fig. 2.

FGF and FGFR expression patterns in the growth plate. Chondrocytes progress through reserve (R), proliferating (P), prehypertrophic (PH) and hypertrophic (H) stages. Hypertrophic chondrocytes are then replaced by trabecular bone (T). FGF 18 is expressed in the perichondrium and may signal to FGFRs in both osteoblasts and chondrocytes.

4.2. Fgf ligands expressed in developing bone

Several FGFs are expressed in developing endochondral bone [16]. FGF2 (basic FGF) was first isolated from growth plate chondrocytes [91]. Subsequently, Fgf2 expression has also been observed in periosteal cells and in osteoblasts [92–95]. Targeted deletion of FGF2 caused a relatively subtle defect in osteoblastogenesis leading to decreased bone growth and bone density. However, no defects in chondrogenesis were observed [94]. Further analysis of _Fgf2_−/− mice revealed decreased osteoclastogenesis [96], which may in part compensate for the observed mild phenotype in _Fgf2_−/− bones. Fgf9 is also expressed in immature chondrocytes in condensing mesenchyme [70,97].

In the perichondrium, expression of Fgf7, Fgf8, Fgf9, Fgf17 and Fgf18 has been observed ([72,74,98–100] I. Hung and DMO, unpublished data), suggesting a possible paracrine signal to the growth plate. Recent genetic studies have identified a defect in chondrogenesis and osteogenesis in mice lacking FGF 18 [98,99]. Mice lacking FGF7, FGF8 and FGF17 have apparently normal chondrogenesis, or in the case of FGF8, die prior to skeletal development [77,101,102]. The skeletons of newborn _Fgf9_−/− mice are slightly smaller than of wild type littermates and their proximal skeletal elements are disproportionately short (I. Hung and DMO, unpublished observation). Issues of functional redundancy among these and other FGFs will need to be addressed in the future.

4.3. FGF signaling pathways in the growth plate

Mice either lacking Fgfr3 or expressing an activated form of Fgfr3 develop skeletal pathology in the perinatal and young adult stages of development. Mice lacking Fgfr3 develop skeletal overgrowth, while mice overexpressing an activated form of Fgfr3 develop skeletal dwarfism. These phenotypes demonstrate that the primary effect of signaling through FGFR3 is to negatively regulate chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation [103–106,81,89,14,15]. This effect is mediated in part by direct signaling in chondrocytes [107–109] and in part indirectly, by regulating the expression of the IHH/PTHrP/BMP signaling pathways [107,63,110,89]. Mice harboring an activating mutation in FGFR3 have decreased expression of Ihh, Ptc and Bmp4 [104,105,89], whereas in mice lacking FGFR3, Ihh, Ptc and Bmp4 expression are upregulated ([89] and data not shown). The overall function of FGFR3 is consistent with a direct action of FGFR3 on proliferating chondrocytes (see below) and an indirect consequence of modulating Hedgehog and BMP signaling.

Ligands that signal to FGFR3 during skeletal development should fit the criteria of expression proximal to zones of proliferating chondrocytes (but not within proliferating chondrocytes) and should produce a phenotype similar to that of _Fgfr3_−/− mice when knocked out. Fgf18, and more recently, Fgf9 expression has been observed in the perichondrium and periosteum of developing bone ([98,99] and I. Hung, unpublished data). Growth plate histology of mice lacking Fgf18 is similar to that of mice lacking Fgfr3. Both knockout mice show an upregulation of Ihh and Ptc expression and increased chondrocyte proliferation. These phenotypic similarities strongly suggest that FGF18 is a physiological ligand for FGFR3 in chondrocytes [98,99]. In vitro studies show that FGF18 can activate FGFR3c [102] and stimulate the proliferation of cultured articular chondrocytes [111]. However, mice lacking Fgf18 have a more severe phenotype than mice lacking Fgfr3 [98]. Unlike _Fgfr3_−/− mice, _Fgf18_−/− mice exhibit delayed ossification which may be due to direct signaling to osteoblasts or hypertrophic chondrocytes or to a delay in vascular invasion of the growth plate. The simplest explanation is that FGF18 is signaling bi-directionally to osteoblasts in the endosteum and primary spongiosa, and to periosteal mesenchyme. Signals to periosteal mesenchyme could either directly or indirectly regulate vasculogenesis. With the recent observation that Fgfr3 is expressed in mature osteoblasts [86], it is not clear which FGFR (FGFR1, FGFR2 or FGFR3) is actually responding to FGF 18 in osteoblasts.

4.4. Signaling pathways regulating chondrocyte and osteoblast proliferation and differentiation

During early embryonic development, constitutive FGFR3 activation enhances proliferation of immature chondrocytes [80,81]. However, as chondrocytes mature, the primary role of FGFR3 is to restrain chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation [89]. The signaling pathways regulating chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation are not unique to FGFR3, even though FGFR1 and FGFR3 appear to have different signaling properties in some cell types in vitro [112–114]. Both FGFR1 and FGFR3 kinase domains appear to have similar activities when expressed in growth plate chondrocytes in vivo [115]. Therefore, observed differences between these receptors must be attributable to differences in the strength of the tyrosine kinase signal rather than the specific signaling pathway activated [116]. This property of FGF signaling in chondrocytes supports the hypothesis that the proliferating chondrocyte itself is uniquely responsive to an FGFR signal.

Endochondral bone growth requires regulated chondrocyte proliferation, differentiation to hypertrophic chondrocytes, and ossification. The signaling pathways mediating growth arrest in mature proliferating chondrocytes are thought to require activation of the MAP kinase pathway [117]. In vivo, activation of MEK1 in chondrocytes caused a dwarfism phenotype but did not affect chondrocyte proliferation [118]. A clue to the signaling mechanism downstream of FGFR3 comes from studies that show that activation of FGF signaling in chondrocytes can increase expression and induce nuclear translocation of STATs 1, 3 and 5 and induce the expression of the cell-cycle inhibitor p21 (WAF1/CIP1) in chondrocyte cell lines [119–122]. Furthermore, chondrocytes isolated from patients with Thanatophoric dysplasia (constitutive activation of FGFR3) exhibited nuclear localized STAT1 [123]. In vivo, the dwarfism phenotype observed in mice expressing activating mutations in FGFR3 correlated with the activation of STAT proteins and upregulation of cell-cycle inhibitors (pl6, pl8 and pl9) [103,105]. Additionally, mating FGF2-expressing transgenic mice into a Stat1 null background corrected the chondrodysplasia phenotype characteristic of this transgenic line [124]. These data support a model in which STAT1 activation acts either downstream or in parallel to the MAP kinase pathway in chondrocytes to mediate inhibition of endochondral growth by FGFR3.

Interestingly, in primary chondrocytes derived from mice lacking STAT1, FGF signaling failed to induce chondrocyte growth inhibition [121]. Furthermore, constitutive activation of MEK1 in chondrocytes resulted in a dwarfism phenotype in mice without affecting chondrocyte proliferation [118]. Mating MEK1 mice to Achondroplasia mice or to mice lacking FGFR3 suggests a model in which FGFR3 signaling inhibits bone growth by inhibiting chondrocyte differentiation through the MAPK pathway and by inhibiting chondrocyte proliferation through a STAT1 pathway [118].

In a chondrocyte cell line, FGF signaling induces differentiation and inhibits proliferation, as demonstrated by inhibition of growth promoting molecules, such as Rb and p107, and up-regulation of genes associated with hypertrophic differentiation, such as MMP13, osteopontin and FGFR1 [107]. The relationship between STAT1 and the regulation of these molecules remains to be determined.

Another role for FGF signaling in chondrocytes may be to promote cell death. Overexpression of Fgf2 or activating mutations in Fgfr3 in chondrocytes promoted apoptosis [124,125]. This is consistent with the observed decrease in AKT phosphorylation in chondrocytes in response to FGF [117,124]. Also consistent with this signaling pathway, treatment of Fgfr3(ACH) cells with growth hormone or IGF-1, which activates PI3 kinase, or with PTHrP, which induces Bcl-2, blocked the apoptosis [125]. Furthermore, in patients with thanatophoric dysplasia, there is an increased expression of Bax, decreased expression of Bcl2 and an increase in the number of apoptotic chondrocytes [123]. In achondroplasia mice, however, no increase in chondrocyte cell death was observed during embryonic development [14].

FGF signaling is also an important regulator of osteoblast function. Mice conditionally lacking FGFR2 or harboring a mutation in the mesenchymal splice form of FGFR2 develop skeletal dwarfism and decreased bone mineral density [126,127]. Examination of the bones of these mice revealed decreased osteoblast proliferation and quiescent osteoblast morphology but otherwise normal differentiation. Thus in osteoblasts, FGFR2 signaling positively regulates bone growth. Interestingly, mice lacking FGF2 also show osteopenia, though much later in development than in FGFR2-deficient mice [94]. This suggests that FGF2 may be a homeostatic factor that replaces the developmental growth factor, FGF18, in adult bones. Osteoblasts also express FGFR3, and mice lacking FGFR3, have decreased bone mineral density and osteopenia [128,86]. In osteoblasts lacking STAT1, FGFR3 and the cell cycle inhibitor, p21WAF/CIP, expression are down regulated and FGF18 expression is increased [86]. Thus STAT1 may regulate the balance between osteoblast proliferation and differentiation by modulating an FGF2/FGF18 to FGFR3 autocrine signal in osteoblasts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant HD39952 and a gift from the Virginia Friedhofer Charitable Trust.

References

- 1.Horton WA, Lunstrum GP. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations in achondroplasia and related forms of dwarfism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2002;3:381–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1020914026829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikegawa S, Fukushima Y, Isomura M, Takada F, Nakamura Y. Mutations of the fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 gene in one familial and six sporadic cases of achondroplasia in Japanese patients. Hum Genet. 1995;96:309–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00210413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rousseau F, Bonaventure J, Legeal-Mallet L, Pelet A, Rozet J-M, Maroteaux P, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in achondroplasia. Nature. 1994;371:252–4. doi: 10.1038/371252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiang R, Thompson LM, Zhu Y-Z, Church DM, Fielder TJ, Bocian M, et al. Mutations in the transmembrane domain of FGFR3 cause the most common genetic form of dwarfism, achondroplasia. Cell. 1994;78:335–42. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Superti-Furga A, Eich G, Bucher HU, Wisser J, Giedion A, Gitzelmann R, et al. A glycine 375-to-cysteine substitution in the transmembrane domain of the fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in a newborn with achondroplasia. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:215–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01954274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellus GA, Mclntosh I, Smith EA, Aylesworth AS, Kaitila I, Horton WA, et al. A recurrent mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 causes hypochondroplasia. Nat Genet. 1995;10:357–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0795-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winterpacht A, Hilbert K, Stelzer C, Schweikardt T, Decker H, Segerer H, et al. A novel mutation in FGFR-3 disrupts a putative N-glycosylation site and results in hypochondroplasia. Physiol Genom. 2000;2:9–12. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2000.2.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rousseau F, el Ghouzzi V, Delezoide AL, Legeai-Mallet L, Le Merrer M, Munnich A, et al. Missense FGFR3 mutations create cysteine residues in thanatophoric dwarfism type I (TD1). Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:509–12. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tavormina PL, Rimoin DL, Cohn DH, Zhu YZ, Shiang R, Wasmuth JJ. Another mutation that results in the substitution of an unpaired cysteine residue in the extracellular domain of FGFR3 in thanatophoric dysplasia type I. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:2175–7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tavormina PL, Shiang R, Thompson LM, Zhu Y, Wilkin DJ, Lachman RS, et al. Thanatophoric dysplasia (types I and II) caused by distinct mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Nat Genet. 1995;9:321–8. doi: 10.1038/ng0395-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Britto JA, Evans RD, Hayward RD, Jones BM. From genotype to phenotype: the differential expression of FGF, FGFR, and TGFbeta genes characterizes human cranioskeletal development and reflects clinical presentation in FGFR syndromes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:2026–39. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200112000-00030. discussion 2040–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen MMJ. Fibroblast growth factor receptor mutations. In: Cohen MMJ, MacLean RE, editors. Craniosynostosis, diagnosis, evaluation and management. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muenke M, Schell U. Fibroblast-growth-factor receptor mutations in human skeletal disorders. Trends Genet. 1995;11:308–13. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naski MC, Ornitz DM. FGF signaling in skeletal development. Front Biosci. 1998;3:D781–94. doi: 10.2741/a321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ornitz DM. Regulation of chondrocyte growth and differentiation by fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Novartis Found Symp. 2001;232:63–76. doi: 10.1002/0470846658.ch6. discussion 76−80, 272−282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ornitz DM, Marie PJ. FGF signaling pathways in endochondral and intramembranous bone development and human genetic disease. Genes Develop. 2002;16:1446–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.990702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkie AOM. Craniosynostosis – genes and mechanisms. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1647–56. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.10.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkie AOM, Slaney SF, Oldridge M, Poole MD, Ashworth GJ, Hockley AD, et al. Apert syndrome results from localized mutations of FGFR2 and is allelic with Crouzon syndrome. Nat Genet. 1995;9:165–72. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Przylepa KA, Paznekas W, Zhang M, Golabi M, Bias W, Bamshad MJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 mutations in Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata syndrome. Nat Genet. 1996;13:492–4. doi: 10.1038/ng0896-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Ravel TJ, Taylor IB, Van Oostveldt AJ, Fryns JP, Wilkie AO. A further mutation of the FGFR2 tyrosine kinase domain in mild Crouzon syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004 doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorry MC, Preston RA, White GJ, Zhang Y, Singhal VK, Losken HW, et al. Crouzon syndrome: mutations in two spliceoforms of FGFR2 and a common point mutation shared with Jackson-Weiss syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1387–90. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.8.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jabs EW, Li X, Scott AF, Meyers G, Chen W, Eccles M, et al. Jackson-Weiss and Crouzon syndromes are allelic with mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 2. Nat Genet. 1994;8:275–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1194-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyers GA, Day D, Goldberg R, Daentl DL, Przylepa KA, Abrams LJ, et al. FGFR2 exon IIIa and IIIc mutations in Crouzon, Jackson-Weiss, and Pfeiffer syndromes: evidence for missense changes, insertions, and a deletion due to alternative RNA splicing. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:491–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyers GA, Orlow SJ, Munro IR, Przylepa KA, Jabs EW. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) transmembrane mutation in Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans. Nat Genet. 1995;11:462–4. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oldridge M, Wilkie AO, Slaney SF, Poole MD, Pulleyn LJ, Rutland P, et al. Mutations in the third immunoglobulin domain of the fibroblast growth factor receptor-2 gene in Crouzon syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1077–82. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.6.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park WJ, Meyers GA, Li X, Theda C, Day D, Orlow SJ, et al. Novel FGFR2 mutations in Crouzon and Jackson-Weiss syndromes show allelic heterogeneity and phenotypic variability. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1229–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.7.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reardon W, Winter RM, Rutland P, Pulleyn LJ, Jones BM, Malcolm S. Mutations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 gene cause Crouzon syndrome. Nat Genet. 1994;8:98–103. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutland P, Pulleyn LJ, Reardon W, Baraitser M, Hayward R, Jones B, et al. Identical mutations in the FGFR2 gene cause both Pfeiffer and Crouzon syndrome phenotypes. Nat Genet. 1995;9:173–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schell U, Hehr A, Feldman GJ, Robin NH, Zackai EH, de Die-Smulders C, et al. Mutations in FGFR1 and FGFR2 cause familial and sporadic Pfeiffer syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:323–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinberger D, Mulliken JB, Muller U. Predisposition for cysteine substitutions in the immunoglobulin-like chain of FGFR2 in Crouzon syndrome. Hum Genet. 1995;96:113–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00214198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinberger D, Mulliken JB, Muller U. Crouzon syndrome: previously unrecognized deletion, duplication, and point mutation within FGFR2 gene. Hum Mutat. 1996;8:386–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)8:4<386::AID-HUMU18>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkie AOM, Morriss-Kay GM, Jones EY, Heath JK. Functions of fibroblast growth factors and their receptors. Curr Biol. 1995;5:500–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Addor MC, Gudinchet F, Laurini RN, Pescia G, Schorderet DF. A new case of Pfeiffer syndrome with mutation in FGFR2. Genet Counsel. 1997;8:303–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cornejo-Roldan LR, Roessler E, Muenke M. Analysis of the mutational spectrum of the FGFR2 gene in Pfeiffer syndrome. Hum Genet. 1999;104:425–31. doi: 10.1007/s004390050979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gripp KW, Stolle CA, McDonald-McGinn DM, Markowitz RI, Bartlett SP, Katowitz JA, et al. Phenotype of the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 Ser351Cys mutation: Pfeiffer syndrome type III. Am J Med Genet. 1998;78:356–60. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980724)78:4<356::aid-ajmg10>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lajeunie E, Ma HW, Bonaventure J, Munnich A, LeMerrer M. FGFR2 mutations in Pfeiffer syndrome. Nat Genet. 1995;9:108. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathijssen IMJ, Vaandrager JM, Hoogeboom AJM, Hesselingjanssen ALW, Vandenouweland AMW. Pfeiffers-syndrome resulting from an S351c mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor-2 gene. J Craniofacial Surgery. 1998;9:207–9. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199805000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellus GA, Gaudenz K, Zackai EH, Clarke LA, Szabo J, Francomano CA, et al. Identical mutations in three different fibroblast growth factor receptor genes in autosomal dominant craniosynostosis syndromes. Nat Genet. 1996;14:174–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilkie AO, Patey SJ, Kan SH, van den Ouweland AM, Hamel BC. FGFs, their receptors, and human limb malformations: clinical and molecular correlations. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:266–78. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ibrahimi OA, Zhang F, Eliseenkova AV, Linhardt RJ, Mohammadi M. Proline to arginine mutations in FGF receptors 1 and 3 result in Pfeiffer and Muenke craniosynostosis syndromes through enhancement of FGF binding affinity. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:69–78. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muenke M, Schell U, Hehr A, Robin NH, Losken HW, Schinzel A, et al. A common mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 gene in Pfeiffer syndrome. Nat Genet. 1994;8:269–74. doi: 10.1038/ng1194-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rossi M, Jones RL, Norbury G, Bloch-Zupan A, Winter RM. The appearance of the feet in Pfeiffer syndrome caused by FGFR1 P252R mutation. Clin Dysmorphol. 2003;12:269–74. doi: 10.1097/00019605-200310000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White KE, Cabral JM, Davis SI, Fishburn T, Evans WE, Ichikawa S, et al. Mutations that cause osteoglophonic dysplasia define novel roles for FGFR1 in bone elongation. Am J Hum Genet. 2004:76. doi: 10.1086/427956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roscioli T, Flanagan S, Kumar P, Masel J, Gattas M, Hyland VJ, et al. Clinical findings in a patient with FGFR1 P252R mutation and comparison with the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2000;93:22–8. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20000703)93:1<22::aid-ajmg5>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dode C, Levilliers J, Dupont JM, De Paepe A, Le Du N, Soussi-Yanicostas N, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in FGFR1 cause autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:463–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muenke M, Gripp KW, McDonald-McGinn DM, Gaudenz K, Whitaker LA, Bartlett SP, et al. A unique point mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 gene (FGFR3) defines a new craniosynostosis syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:555–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sabatino G, Di Rocco F, Zampino G, Tamburrini G, Caldarelli M, Di Rocco C. Muenke syndrome. ChildsNerv Syst. 2004;20:297–301. doi: 10.1007/s00381-003-0906-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bellus GA, Bamshad MJ, Przylepa KA, Dorst J, Lee RR, Hurko O, et al. Severe achondroplasia with developmental delay and acanthosis nigricans (SADDAN): phenotypic analysis of a new skeletal dysplasia caused by a Lys650Met mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Am J Med Genet. 1999;85:53–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen MM., Jr Let's call it “Crouzonodermoskeletal syndrome” so we won't be prisoners of our own conventional terminology. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84:74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeftha A, Stephen L, Morkel JA, Beighton P. Crouzonodermoskeletal syndrome. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2004;28:173–6. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.28.2.72m01l5g50448548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagase T, Nagase M, Hirose S, Ohmori K. Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans: case report and mutational analysis. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 2000;37:78–82. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_2000_037_0078_cswanc_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilkes D, Rutland P, Pulleyn LJ, Reardon W, Moss C, Ellis JP, et al. A recurrent mutation, ala391glu, in the transmembrane region of FGFR3 causes Crouzon syndrome and acanthosis nigricans. J Med Genet. 1996;33:744–8. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.9.744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kosher RA, Kulyk WM, Gay SW. Collagen gene expression during limb cartilage differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1151–6. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.4.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nah HD, Rodgers BJ, Kulyk WM, Kream BE, Kosher RA, Upholt WB. In situ hybridization analysis of the expression of the type II collagen gene in the developing chicken limb bud. Coll Relat Res. 1988;8:277–94. doi: 10.1016/s0174-173x(88)80001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shum L, Coleman CM, Hatakeyama Y, Tuan RS. Morphogenesis and dysmorphogenesis of the appendicular skeleton. Birth Defects Res Part C Embryo Today Rev. 2003;69:102–22. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wright E, Hargrave MR, Christiansen J, Cooper L, Kun J, Evans T, et al. The Sry-related gene Sox9 is expressed during chondrogenesis in mouse embryos. Nat Genet. 1995;9:15–20. doi: 10.1038/ng0195-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hall BK, Miyake T. The membranous skeleton: the role of cell condensations invertebrate skeletogenesis. AnatEmbryol (Berl) 1992;186:107–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00174948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hall BK, Miyake T. All for one and one for all: condensations and the initiation of skeletal development. Bioessays. 2000;22:138–47. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200002)22:2<138::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmid TM, Linsenmayer TF. Immunohistochemical localization of short chain cartilage collagen (type X) in avian tissues. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:598–605. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.2.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Noonan KJ, Hunziker EB, Nessler J, Buckwalter JA. Changes in cell, matrix compartment, and fibrillar collagen volumes between growth-plate zones. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:500–8. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caplan AI, Pechak DG. The cellular and molecular embryology of bone formation. In: Peck WA, editor. Bone and mineral research. Elsevier; New York: 1987. pp. 117–83. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karsenty G, Wagner EF. Reaching a genetic and molecular understanding of skeletal development. Develop Cell. 2002;2:389–406. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kronenberg HM. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature. 2003;423:332–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olsen BR, Reginato AM, Wang W. Bone development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:191–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wagner EF, Karsenty G. Genetic control of skeletal development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:527–32. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peters KG, Werner S, Chen G, Williams LT. Two FGF receptor genes are differentially expressed in epithelial and mesenchymal tissues during limb formation and organogenesis in the mouse. Development. 1992;114:233–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Delezoide AL, Benoistlasselin C, Legeaimallet L, Lemerrer M, Munnich A, Vekemans M, et al. Spatio-temporal expression of Fgfr 1, 2 and 3 genes during human embryo-fetal ossification. Mech Dev. 1998;77:19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Orr-Urtreger A, Givol D, Yayon A, Yarden Y, Lonai P. Developmental expression of two murine fibroblast growth factor receptors, flg and bek. Development. 1991;773:1419–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Szebenyi G, Savage MP, Olwin BB, Fallon JF. Changes in the expression of fibroblast growth factor receptors mark distinct stages of chondrogenesis in vitro and during chick limb skeletal patterning. Dev Dyn. 1995;204:446–56. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Colvin JS, Feldman B, Nadeau JH, Goldfarb M, Ornitz DM. Genomic organization and embryonic expression of the mouse fibroblast growth factor 9 gene. Dev Dyn. 1999;216:72–88. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199909)216:1<72::AID-DVDY9>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.deLapeyriere O, Ollendorff V, Planche J, Ott MO, Pizette S, Coulier F, et al. Expression of the Fgf6 gene is restricted to developing skeletal muscle in the mouse embryo. Development. 1993;118:601–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Finch PW, Cunha GR, Rubin JS, Wong J, Ron D. Pattern of keratinocyte growth factor and keratinocyte growth factor receptor expression during mouse fetal development suggests a role in mediating morphogenetic mesenchymal-epithelial interactions. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:223–40. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haub O, Goldfarb M. Expression of the fibroblast growth factor-5 gene in the mouse embryo. Development. 1991;112:397–406. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.2.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mason IJ, Fuller-Pace F, Smith R, Dickson C. FGF-7 (keratinocyte growth factor) expression during mouse development suggests roles in myogenesis, forebrain regionalisation and epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Mech Dev. 1994;45:15–30. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Savage MP, Fallon JF. FGF-2 mRNA and its antisense message are expressed in a developmentally specific manner in the chick limb bud and mesonephros. Dev Dyn. 1995;202:343–53. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002020404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fiore F, Planche J, Gibier P, Sebille A, Delapeyriere O, Birnbaum D. Apparent normal phenotype of Fgf6−/− mice. Int J Devel Biol. 1997;41:639–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guo L, Degenstein L, Fuchs E. Keratinocyte growth factor is required for hair development but not for wound healing. Genes Dev. 1996;10:165–75. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hebert JM, Rosenquist T, Gotz J, Martin GR. FGF5 as a regulator of the hair growth cycle: evidence from targeted and spontaneous mutations. Cell. 1994;78:1017–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Murakami S, Kan M, McKeehan WL, de Crombrugghe B. Up-regulation of the chondrogenic Sox9 gene by fibroblast growth factors is mediated by the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1113–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iwata T, Chen L, Li C, Ovchinnikov DA, Behringer RR, Francomano CA, et al. A neonatal lethal mutation in FGFR3 uncouples proliferation and differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes in embryos. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1603–13. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.11.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Iwata T, Li CL, Deng CX, Francomano CA. Highly activated Fgfr3 with the K644M mutation causes prolonged survival in severe dwarf mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1255–64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.12.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weksler NB, Lunstrum GP, Reid ES, Horton WA. Differential effects of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 9 and FGF2 on proliferation, differentiation and terminal differentiation of chondrocytic cells in vitro. Biochem J. 1999;342:677–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yu K, Herr AB, Waksman G, Ornitz DM. Loss of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 ligand-binding specificity in Apert syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14536–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yu K, Ornitz DM. Uncoupling fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 ligand binding specificity leads to Apert syndrome-like phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3641–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081082498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ibrahimi OA, Zhang F, Eliseenkova AV, Itoh N, Linhardt RJ, Mohammadi M. Biochemical analysis of pathogenic ligand-dependent FGFR2 mutations suggests distinct pathophysiological mechanisms for craniofacial and limb abnormalities. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2313–24. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xiao L, Naganawa T, Obugunde E, Gronowicz G, Ornitz DM, Coffin JD, et al. Statl controls postnatal bone formation by regulating fibroblast growth factor signaling in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21143–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Deng C, Wynshaw-Boris A, Zhou F, Kuo A, Leder P. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is a negative regulator of bone growth. Cell. 1996;84:911–21. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peters K, Ornitz DM, Werner S, Williams L. Unique expression pattern of the FGF receptor 3 gene during mouse organogenesis. Dev Biol. 1993;155:423–30. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Naski MC, Colvin JS, Coffin JD, Ornitz DM. Repression of hedgehog signaling and BMP4 expression in growth plate cartilage by fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Development. 1998;125:4977–88. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.4977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pandit SG, Govindraj P, Sasse J, Neame PJ, Hassell JR. The fibroblast growth factor receptor, FGFR3, forms gradients of intact and degraded protein across the growth plate of developing bovine ribs. Biochem J. 2002;361:231–41. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3610231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sullivan R, Klagsbrun M. Purification of cartilage-derived growth factor by heparin affinity chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:2399–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hurley MM, Abreu C, Gronowicz G, Kawaguchi H, Lorenzo J. Expression and regulation of basic fibroblast growth factor mRNA levels in mouse osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9392–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hurley MM, Tetradis S, Huang YF, Hock J, Kream BE, Raisz LG, et al. Parathyroid hormone regulates the expression of fibroblast growth factor-2 mRNA and fibroblast growth factor receptor mRNA in osteoblastic cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:776–83. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.5.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Montero A, Okada Y, Tomita M, Ito M, Tsurukami H, Nakamura T, et al. Disruption of the fibroblast growth factor-2 gene results in decreased bone mass and bone formation. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1085–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI8641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sabbieti MG, Marchetti L, Abreu C, Montero A, Hand AR, Raisz LG, et al. Prostaglandins regulate the expression of fibroblast growth factor-2 in bone. Endocrinology. 1999;140:434–44. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.1.6442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Okada Y, Montero A, Zhang X, Sobue T, Lorenzo J, Doetschman T, et al. Impaired osteoclast formation in bone marrow cultures of Fgf2 null mice in response to parathyroid hormone. J Biol Chem. 2003 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Garofalo S, Kliger-Spatz M, Cooke JL, Wolstin O, Lunstrum GP, Moshkovitz SM, et al. Skeletal dysplasia and defective chondrocyte differentiation by targeted overexpression of fibroblast growth factor 9 in transgenic mice. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1909–15. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.11.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu Z, Xu J, Colvin JS, Ornitz DM. Coordination of chondrogenesis and osteogenesis by fibroblast growth factor 18. Genes Develop. 2002;16:859–69. doi: 10.1101/gad.965602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ohbayashi N, Shibayama M, Kurotaki Y, Imanishi M, Fujimori T, Itoh N, et al. FGF 18 is required for normal cell proliferation and differentiation during osteogenesis and chondrogenesis. Genes Develop. 2002;16:870–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.965702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xu J, Lawshe A, Mac Arthur CA, Ornitz DM. Genomic structure, mapping, activity and expression of fibroblast growth factor 17. Mech Dev. 1999;83:165–78. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Meyers EN, Lewandoski M, Martin GR. An Fgf8 mutant allelic series generated by Cre- and Flp-mediated recombination. Nat Genet. 1998;18:136–41. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xu JS, Liu ZH, Ornitz DM. Temporal and spatial gradients of Fgf8 and Fgfl7 regulate proliferation and differentiation of midline cerebellar structures. Development. 2000;127:1833–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.9.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chen L, Adar R, Yang X, Monsonego EO, Li C, Hauschka PV, et al. Gly369Cys mutation in mouse FGFR3 causes achondroplasia by affecting both chondrogenesis and osteogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1517–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI6690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen L, Li C, Qiao W, Xu X, Deng C. A Ser(365)->Cys mutation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 in mouse downregulates Ihh/PTHrP signals and causes severe achondroplasia. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:457–65. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.5.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li C, Chen L, Iwata T, Kitagawa M, Fu XY, Deng CX. A Lys644Glu substitution in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) causes dwarfism in mice by activation of STATs and ink4 cell cycle inhibitors. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:35–44. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang YC, Spatz MK, Kannan K, Hayk H, Avivi A, Gorivodsky M, et al. A mouse model for achondroplasia produced by targeting fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4455–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dailey L, Laplantine E, Priore R, Basilico C. A network of transcriptional and signaling events is activated by FGF to induce chondrocyte growth arrest and differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:1053–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Henderson JE, Naski MC, Aarts MM, Wang D, Cheng L, Goltzman D, et al. Expression of FGFR3 with the G380R achondroplasia mutation inhibits proliferation and maturation of CFK2 chondrocytic cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:155–65. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Mosonego-Ornan E, Sadot E, Madar-Shapiro L, Sheinin Y, Ginsberg D, A., Y Induction of chondrocyte growth arrest by FGF: transcriptional and cytoskeletal alterations. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:553–62. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Minina E, Kreschel C, Naski MC, Ornitz DM, Vortkamp A. Interaction of FGF, Ihh/Pthlh, and BMP signaling integrates chondrocyte proliferation and hypertrophic differentiation. Dev Cell. 2002;3:439–49. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ellsworth JL, Berry J, Bukowski T, Claus J, Feldhaus A, Holderman S, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-18 is a trophic factor for mature chondrocytes and their progenitors. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2002;10:308–20. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lin HY, Xu JS, Ornitz DM, Halegoua S, Hayman MJ. The fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 is necessary for the induction of neurite outgrowth in PC 12 cells by aFGF. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4579–87. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-15-04579.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Naski MC, Wang Q, Xu J, Ornitz DM. Graded activation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 by mutations causing achondroplasia and thanatophoric dysplasia. Nat Genet. 1996;13:233–7. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang JK, Gao G, Goldfarb M. Fibroblast growth factor receptors have different signaling and mitogenic potentials. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:181–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang Q, Green RP, Zhao G, Ornitz DM. Differential regulation of endochondral bone growth and joint development by FGFR1 and FGFR3 tyrosine kinase domains. Development. 2001;128:3867–76. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Raffioni S, Thomas D, Foehr ED, Thompson LM, Bradshaw RA. Comparison of the intracellular signaling responses by three chimeric fibroblast growth factor receptors in PC 12 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7178–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Raucci A, Laplantine E, Mansukhani A, Basilico C. Activation of the ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediates fibroblast growth factor-induced growth arrest of chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1747–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Murakami S, Balmes G, McKinney S, Zhang Z, Givol D, De Crombrugghe B. Constitutive activation of MEK1 in chondrocytes causes Stat1-independent achondroplasia-like dwarfism and rescues the Fgfr3-deficient mouse phenotype. Genes Dev. 2004;18:290–305. doi: 10.1101/gad.1179104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hart KC, Robertson SC, Kanemitsu MY, Meyer AN, Tynan JA, Donoghue DJ. Transformation and Stat activation by derivatives of FGFR1, FGFR3, and FGFR4. Oncogene. 2000;19:3309–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Legeai-Mallet L, Benoist-Lasselin C, Munnich A, Bonaventure J. Overexpression of FGFR3, Statl, Stat5 and p21Cipl correlates with phenotypic severity and defective chondrocyte differentiation in FGFR3-related chondrodysplasias. Bone. 2004;34:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sahni M, Ambrosetti DC, Mansukhani A, Gertner R, Levy D, Basilico C. FGF signaling inhibits chondrocyte proliferation and regulates bone development through the STAT-1 pathway. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1361–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Su WCS, Kitagawa M, Xue NR, Xie B, Garofalo S, Cho J, et al. Activation of Statl by mutant fibroblast growth-factor receptor in thanatophoric dysplasia type II dwarfism. Nature. 1997;386:288–92. doi: 10.1038/386288a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Legeai-Mallet L, Benoist-Lasselin C, Delezoide AL, Munnich A, Bonaventure J. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations promote apoptosis but do not alter chondrocyte proliferation in thanatophoric dysplasia. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13007–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sahni M, Raz R, Coffin JD, Levy D, Basilico C. STAT1 mediates the increased apoptosis and reduced chondrocyte proliferation in mice overexpressing FGF2. Development. 2001;128:2119–29. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.11.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yamanaka Y, Ueda K, Seino Y, Tanaka H. Molecular basis for the treatment of achondroplasia. Horm Res. 2003;60(3):60–4. doi: 10.1159/000074503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Eswarakumar VP, Monsonego-Ornan E, Pines M, Antonopoulou I, Morriss-Kay GM, Lonai P. The IIIc alternative of Fgfr2 is a positive regulator of bone formation. Development. 2002;129:3783–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.16.3783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yu K, Xu J, Liu Z, Sosic D, Shao J, Olson EN, et al. Conditional inactivation of FGF receptor 2 reveals an essential role for FGF signaling in the regulation of osteoblast function and bone growth. Development. 2003;130:3063–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Valverde-Franco G, Liu H, Davidson D, Chai S, Valderrama-Carvajal H, Goltzman D, et al. Defective bone mineralization and osteopenia in young adult FGFR3−/− mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:271–84. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]