Interaction of Salmonella spp. with the Intestinal Microbiota (original) (raw)

Abstract

Salmonella spp. are major cause of human morbidity and mortality worldwide. Upon entry into the human host, Salmonella spp. must overcome the resistance to colonization mediated by the gut microbiota and the innate immune system. They successfully accomplish this by inducing inflammation and mechanisms of innate immune defense. Many models have been developed to study Salmonella spp. interaction with the microbiota that have helped to identify factors necessary to overcome colonization resistance and to mediate disease. Here we review the current state of studies into this important pathogen/microbiota/host interaction in the mammalian gastrointestinal tract.

Keywords: Salmonella, microbiome, microbiota, colonization resistance

Introduction

Humans are colonized by trillions of bacteria that primarily reside on mucosal and epithelial surfaces (Costello et al., 2009). These microbes exist principally in a balanced symbiotic relationship with the host, thus resulting in little or no pathogenic outcome unless the host or the colonized mucosa becomes compromised (Lee and Mazmanian, 2010). The anatomic location for most of these microbes is the gut, which contains an estimated 10–100 trillion microbes representing at least 160 bacterial species per person (>1000 bacterial species can be found among different humans; Hooper and Gordon, 2001; Eckburg et al., 2005; Turnbaugh and Gordon, 2009; Lee and Mazmanian, 2010; Qin et al., 2010). The majority of these bacteria belong to one of two major phyla: Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (Ley et al., 2006, 2008). These intestinal microbes provide many benefits for the host, including proper development of the immune system, the digestion of food and absorption of nutrients, the production of key vitamins (e.g., vitamin K and biotin), and protection against invading pathogenic organisms (Backhed et al., 2005; Lee and Mazmanian, 2010). Such protection against the colonization by pathogens has been called colonization resistance (van der Waaij et al., 1971; Stecher et al., 2008). In the literature, there is copious data to support the contention that the normal intestinal flora, or microbiota, protects against these invading microbes. For example, germ-free or abiotic mice possess increased susceptibility to enteric pathogens as well as abnormal intestinal mucosal immune system development (Bohnhoff et al., 1954; Miller and Bohnhoff, 1963; Gustafsson, 1982; Que and Hentges, 1985; Nardi et al., 1989; Lee and Mazmanian, 2010).

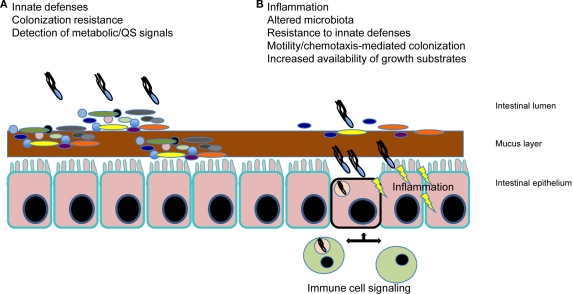

Salmonella species (spp.) are a significant group of intestinal pathogens with primary clinical manifestations of gastroenteritis and typhoid fever. Non-typhoidal Salmonella spp. (e.g., S. enterica serovar Typhimurium; S. Typhimurium) result in much of the food-borne disease diagnosed worldwide, while the primary cause of typhoid fever, the human specific pathogen (S. enterica serovar Typhi; S. Typhi) causes significant morbidity and mortality worldwide (Rabsch et al., 2001; Crump and Mintz, 2010; Graham, 2010). Salmonella spp. have been studied quite extensively with regard to their pathogenic properties including their ability to penetrate the intestinal barrier, and for typhoidal species, to replicate within host macrophages. However, only recently have studies begun to intensify with regard to the interaction of Salmonella spp. with the gastrointestinal microbiota. In this review, we will summarize the literature with regard to the role that the microbiota plays in colonization resistance against Salmonella spp., how salmonellae are able to overcome this colonization resistance, other factors that influence the survival of Salmonella spp. in the gut, and the methods that have been used to study _Salmonella_–microbiota interactions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Salmonella spp. interaction with the intestinal microbiota. (A) The gut microbiota (illustrated by the multiple colored bacteria) mediates “colonization resistance” by outcompeting invading pathogens such as Salmonella. In addition, innate immune defenses (e.g., antimicrobial molecules, mucus, sIgA, etc.) help to prevent pathogen colonization. At the time of this initial interaction of Salmonella with the microbiota, signals produced by the host and the gut microbes are being sensed by Salmonella, which influences the pathogenic outcome. (B) Salmonella spp. are able to overcome colonization resistance and initiate localized inflammation, which is key to disease manifestation. This inflammation is a result of motile Salmonella and SPI-1-mediated invasion of M-cells in Peyer's patches and enterocytes, as well as PAMP signaling. Phagocytic cell uptake and subsequent host cell signaling results in alteration of the microbiota, further induction of host innate resistance mechanisms (to which the bacteria respond with their own induced resistance), and the increased availability of growth substrates, some which specifically allow Salmonella to outcompete the microbiota. Perturbation of the microflora (e.g., antibiotic/probiotics) also creates an altered gut environment that can affect Salmonella spp. colonization.

Methods to Study Salmonella spp. Interactions with the Gut Microbiota

Several methods have been developed that could be used to study Salmonella spp. interactions with the gastrointestinal microbial community. We will briefly review methods to study Salmonella spp. gene expression and to screen for mutant phenotypes in vivo. Conversely, metagenomic and next generation sequencing methods can be used to study the effect of Salmonella spp. on the rest of the microbiota or the host.

The original genetic method to study gene expression in vivo was called in vivo expression technology (IVET; Mahan et al., 1993; Slauch et al., 1994). This is a promoter trapping strategy that can identify genes that are expressed in vivo but not in vitro. Essentially, a library of random purA–lacZ fusions is created in a purA deletion background. The purA gene is an essential metabolic gene so only those library members that contain fusions expressed in vivo can survive in the mouse. The survivors are recovered from the mouse and plated on X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside), a colorimetric indicator of LacZ activity, to identify those fusions that are not expressed in vitro. This method was successful in identifying numerous metabolic and virulence genes that are expressed in vivo (Heithoff et al., 1997). One disadvantage of the method is that purA is essential throughout infection and may be too stringent. Other variations that used antibiotic resistance genes in place of purA were developed so that a pulse of antibiotic could be administered to the mouse to provide shorter periods of selection (Mahan et al., 1995; Young and Miller, 1997).

A variation of the IVET method is RIVET (Recombination-based IVET; Camilli et al., 1994; Camilli and Mekalanos, 1995), which utilizes tnpR fusions. The readout for tnpR is the site-specific recombination of a pair of target sites (res sites) placed elsewhere in the chromosome. DNA between the target sites is deleted, leaving a single res site. A variety of marker genes can be placed between these res sites. The first variant used a res-tetRA-res cassette so that the readout for tnpR expression is a change from tetracycline resistant to tetracycline sensitive. The advantage of RIVET is that the gene expression event is recorded permanently in the genome. RIVET has been used extensively to study Vibrio cholerae (Osorio et al., 2005; Lombardo et al., 2007). This method has also worked well for studying S. Typhimurium phoPQ and pmrAB expression in the gastrointestinal tract and for determining that the S. Typhimurium AHL detector, SdiA, becomes active in _Yersinia_-infected mice (Merighi et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2008; Dyszel et al., 2010; Noel et al., 2010).

GFP is another reporter that can be used to study single genes or entire libraries. A method termed differential fluorescence induction (DFI) can be used to sort bacteria that have high fluorescence in vivo from those that have low fluorescence in vitro (Valdivia and Falkow, 1996, 1997; Valdivia et al., 1996; Bumann and Valdivia, 2007). Though powerful, this method has not yet been used to study Salmonella spp. interactions specifically with the intestinal microbiota.

Phenotypic methods for studying Salmonella spp. interactions with the microbiota are advancing rapidly. For screening hundreds or thousands of Salmonella spp. mutants simultaneously there are now two different approaches. The first approach is to use microarrays to monitor the populations of individual mutants in a library, before and after a selective event, such as transit through an animal (Badarinarayana et al., 2001; Sassetti et al., 2001). All mutants that increase or decrease in proportion to the remainder of the library are readily identified. The microarray methodologies are primarily called transposon site hybridization (TraSH; Sassetti et al., 2001; Murry et al., 2008). Several TraSH variants have been successful in identifying Salmonella spp. genes required for host colonization (Lawley et al., 2006; Chaudhuri et al., 2009; Santiviago et al., 2009). The second approach uses next generation sequencing technology to measure the proportion of mutants in a library before and after the selective event. This method is primarily referred to as Tn-seq (van Opijnen et al., 2009; Opijnen and Camilli, 2010; Gallagher et al., 2011) or INSeq (Goodman et al., 2009). By barcoding each experiment, one can put up to 96 Tn-seq experiments into a single sequencing run. This has been termed Bar-seq (Smith et al., 2010). Though clearly applicable and achievable, to date, no research groups have used any of these methods to study how Salmonella spp. interact specifically with other members of the intestinal microbiota.

Genomic DNA libraries, or cDNA libraries, of entire microbial communities can be constructed and screened for the presence of individual DNA sequences of interest, or the libraries can be sequenced in their entirety. Alternatively, the library can be screened for function in a heterologous host, typically E. coli. This is called metagenomics and has been used to identify the entire “metagenome” of gut microbial communities from several animal and human subjects (Handelsman, 2004). Newer deep sequencing methods are being used to sequence the entire gut community or “microbiome.” This is a powerful technique for predicting the type and abundance of microbes present as well as metabolic pathways and function of the community as a whole (Booijink et al., 2007; Frank and Pace, 2008; Ventura et al., 2009; Qin et al., 2010; Vacharaksa and Finlay, 2010; Wang et al., 2010). The type and quantity of community variation can be characterized between healthy individuals, diseased individuals, and individuals after perturbations such as antibiotics or changes in diet (Turnbaugh and Gordon, 2009; Neu et al., 2010; Willing et al., 2010). In addition, quantitation of 16S rDNA has been used to study the effects of Salmonella and other pathogens on the gut microbial community (Lupp et al., 2007; Stecher et al., 2007; Barman et al., 2008; Sekirov et al., 2010). Using this technology, it was found that _Salmonella_-induced inflammation both decreased the population and altered the composition of the microbiota in a manner that was dependent upon Salmonella SPI1 and SPI2 and upon reactive oxygen and nitrogen species of the host (Stecher et al., 2007; Ackermann et al., 2008).

Animal Models for Studying Salmonella spp. Interactions with the Microbiota

Conventional mice

The most commonly used animal model for S. Typhimurium infection is the BALB/c or C57BL/6 mouse. These mice have a mutation in the Slc11a1 gene (previously known as Nramp1) that leaves them susceptible to systemic infection by S. Typhimurium. The Slc11A1 mutation causes a defect in ion transport in phagocytic vesicles allowing S. Typhimurium to survive in macrophages (Blackwell et al., 2001). This model serves as a surrogate for the infection of humans by the host-restricted serovar Typhi that causes Typhoid fever, though new humanized mouse models for S. Typhi have recently been developed (Firoz Mian et al., 2010; Libby et al., 2010; Song et al., 2010). Typhimurium is an extremely important human and animal pathogen in its own right, being one of the most common and most serious, causes of human food-borne gastroenteritis (Scallan et al., 2011). Additionally, in Africa, non-typhoidal serovars (NTS) including Typhimurium have become a major cause of systemic disease in immunocompromised patients (Kingsley et al., 2009; Gordon et al., 2010; Graham, 2010). One drawback of Slc11A1 mouse strains is that they succumb to even low dose infection fairly rapidly, within 10 days. To study persistence, some researchers are using 129/SvJ or CBA mice that bear a functional Slc11A1 allele (Lawley et al., 2006; Tsolis et al., 2011). S. Typhimurium persists in the GI tract for greater than 30 days in these mice and has been found to persist in the mesenteric lymph nodes and gallbladder as well (Monack et al., 2004; Lawley et al., 2006; Crawford et al., 2010).

Streptomycin-treated and gnotobiotic mice

While S. Typhimurium infection of susceptible mice has been used to model human typhoid fever, there are two problems with using conventional mice as a model for S. Typhimurium gastroenteritis. The first problem is that the mice do not get diarrhea as in the human infection. The second problem is that the normal microbiota causes bottlenecks in Salmonella spp. populations during phenotypic screening experiments. This is an issue for any method that requires large numbers of library members to undergo selection in the animal (IVET, TraSH, Tn-seq, etc.). Bottlenecks are the stochastic loss of library members, rendering the TraSH or Tn-seq results unreliable. Mice treated with antibiotics to disrupt their normal flora (most commonly streptomycin) do not cause Salmonella spp. populations to bottleneck (Hapfelmeier and Hardt, 2005; Stecher and Hardt, 2011). These mice also get symptoms that are closer to human gastroenteritis, allowing this human disease to be modeled. Gnotobiotic mice have the same advantages as streptomycin-treated mice but have the additional advantage that the composition of the microbial community can be controlled. Gnotobiotic simply means “known flora” and this can range from abiotic mice that have no flora (also known as germ-free or axenic), to mono-associated mice that are colonized with a single known microbial species, to poly-associated mice that are colonized with multiple species (Falk et al., 1998). The combination of gnotobiotic mice with TraSH, Tn-seq, and deep sequencing methods should revolutionize the study of how Salmonella spp. interact with the intestinal microbiota (Goodman et al., 2009; Faith et al., 2010).

Antimicrobial Mechanisms of the Human Gut and Gut Microflora

The human gut contains an arsenal of barriers to incoming pathogenic organisms. These barriers can come in many forms, including physical, chemical, enzymatic, or immune. Salmonella spp., which primarily colonize the distal ileum/cecum, first must overcome physical barriers in this environment. Although not always considered, a thick mucous layer covers the intestinal epithelium and presents a significant challenge to microbes that must traverse this layer to come into direct contact with the intestinal epithelium. Though the mucus provides an environment for attachment and nutrition, it both prevents epithelial cell engagement and harbors other antimicrobial substances such as IgA and cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs; Lievin-Le Moal and Servin, 2006; Macpherson and Slack, 2007; Meyer-Hoffert et al., 2008). The CAMPs found in the gut are primarily either defensins or cathelicidins (Zasloff, 2002; Iimura et al., 2005; Ouellette, 2010; Salzman et al., 2010). CAMPs typically kill bacteria by forming pores in the membrane, but these peptides have also been shown to have immunomodulatory activities, primarily resulting in the recruitment of neutrophils to sites of infection (Yang et al., 2001; Bowdish et al., 2006; Hazlett and Wu, 2011). Mucins (e.g., MUC4), IgA, and antimicrobial peptides can be regulated by bacterial colonization and thus represent an inducible mechanism of resistance (Salzman et al., 2003; Macpherson and Uhr, 2004; Raffatellu et al., 2009; Veldhuizen et al., 2009).

As well as traversing the mucous layer, colonizing pathogenic microbes must compete effectively with the existing microbiota. This microbiota provides a crucial line of defense as they can both compete for nutritional resources and for attachment sites to the intestinal epithelium. In addition, some microflora can produce bacteriocins, which are toxins that act in a similar manner to CAMPs but are produced by the microbiota instead of the host (Sanchez et al., 2010). If invading microbes are able to overcome the mucous layer and compete effectively against the microflora, other antimicrobial molecules must also be successfully overcome. Interleukin signaling from the mucosa results in the host production of lipocalin-2, which binds to the siderophore enterobactin/enterochelin in an attempt to withhold iron from bacteria (Raffatellu et al., 2009; Blaschitz and Raffatellu, 2010; Raffatellu and Bäumler, 2010). However, Salmonella also produces a second siderophore, salmochelin, which is not bound by lipocalin-2, thus enabling Salmonella spp. to compete for iron necessary for growth (Raffatellu et al., 2009). The Paneth cells found at the base of the intestinal crypts produce, in addition to the aforementioned CAMPs, antimicrobial products including angiogenins and the C-type lectin, RegIIIγ (regenerating gene; mouse)/HIP-PAP (hepatocarcinoma-intestine-pancreas/pancreas-associated protein; Human); Hooper et al., 2003; Cash et al., 2006). Although RegIIIγ is induced by mucosal damage and inflammatory stimuli, it is primarily effective against Gram-positive bacteria and thus would play a limited direct role against Salmonella spp. (Brandl et al., 2008; Godinez et al., 2009; Lehotzky et al., 2010).

The intestinal microbes themselves, in addition to producing bacteriocins, produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) as a consequence of their metabolic activity (Cummings and Macfarlane, 1991, 1997). Microbiota-produced butyrate and acetate can have dramatic effects on both the host and on Salmonella spp. during infection (Garner et al., 2009). Acetate and formate in the small intestine were found to have a positive effect on Salmonella Pathogenicity Island I-mediated invasion (Huang et al., 2008; Chavez et al., 2010) while propionate and butyrate, present in high concentrations in the cecum and colon, had the opposite effect (Gantois et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2006). These metabolic byproducts thus may represent environmental signals that direct Salmonella spp. to the distal ileum for invasion. Additionally, butyrate is known to induce expression of the human cathelicidin LL-37 (mouse: CRAMP), which could clearly affect invading pathogens (Raqib et al., 2006).

Given the antimicrobial environment of the human gut, how can pathogens such as Salmonella spp. overcome the intestinal flora and antimicrobial onslaught? It is likely a multifactorial response, both inherent and induced. Salmonella spp. have evolved numerous countermeasures to the antimicrobials present in the gut. Such mechanisms include resistance to both oxidative and non-oxidative host killing. Resistance to reactive oxygen and nitrogen compounds include such enzymes as superoxide dismutase and catalase (Vazquez-Torres and Fang, 2001; Prost et al., 2007; Ackermann et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2010). A well-studied resistance mechanism to non-oxidative killing includes the in vivo regulated modifications of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a glycolipid that constitutes the majority of the outer leaflet of the outer membrane of Salmonella spp. (Guo et al., 1997; Gunn, 2008; Richards et al., 2010). These modifications, mediated primarily by environmental sensing via the two-component regulatory systems PhoP–PhoQ and PmrA–PmrB, result in resistance to CAMPs either by lack of CAMP binding to the bacterium or poor penetration of the CAMPs to the inner membrane, the site of lethal action (Guo et al., 1998; Richards et al., 2010). Thus, it can be hypothesized that upon Salmonella spp. entry into the intestinal environment and subsequent CAMP induction (CAMPs can activate the PhoP–PhoQ and PmrA–PmrB regulatory systems), these CAMPs may differentially affect the microbiota (reduce it) while allowing CAMP resistant Salmonella spp. to flourish.

Inflammation as a Mechanism to Overcome Gut Colonization Resistance

While the human intestine is always in a mild state of inflammation, invading pathogens trigger an induction of innate and adaptive immune responses. The inflammatory response of the host is triggered by effector molecules secreted by Type III secretion systems of Salmonella pathogenicity Islands I and II as well as extracellular and intracellular detection of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPS) of the bacteria, which include LPS, peptidoglycan, and flagellin (Zhou and Galan, 2001; Abrahams and Hensel, 2006). LPS is detected through the combinatorial efforts of LPS-binding protein, CD14, MD-2, and toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 (Abreu, 2010). Peptidoglycan is detected by TLR-2 as well and intracellularly by proteins of the nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs; Abreu, 2010). Flagellin is detected by TLR-5 as well as NLRP3 (NLR family pyrin domain containing; previously NALP3) and NLRC4 (NLR family CARD domain containing; previously IPAF [IL-1β-converting enzyme protease activating factor]), both of which activate caspase-1 in response to S. Typhimurium (Grassl and Finlay, 2008; Broz et al., 2010). Such NLR signaling induces the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 (Tam et al., 2008). These cytokines, along with IL-23, result in an immune cascade of activation involving T-cell induced IL-17 and IFN-γ, ultimately resulting in the induction of host-derived intestinal defense mechanisms discussed earlier (Stecher et al., 2007; Santos et al., 2009).

Salmonella Typhimurium has been shown to be unable to colonize the mouse intestine in the absence of inflammation, as the normal flora in the non-inflamed state is able to effectively outcompete an avirulent (lacking inflammatory capacity) Salmonella intruder (Stecher et al., 2007; Santos et al., 2009; Winter et al., 2010). This phenomenon can be reversed by either mixing the avirulent S. Typhimurium with wildtype strains capable of inducing inflammation or in mice lacking the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Additionally, _Salmonella_-induced inflammation results in an altered microbiota, which may also favor growth of the pathogen (Lupp et al., 2007; Barman et al., 2008).

The Link between the Host, Microbial Metabolism, and Salmonella spp. Intestinal Colonization

As discussed above, nutrient availability can be increased upon Salmonella spp. induction of inflammation. Also discussed above, SCFA synthesis by the microbiota can be used both by the host to induce defense mechanisms and by the bacterium to enhance invasion of the intestinal epithelium. Recently, direct links have arisen between S. Typhimurium, intestinal inflammation, and metabolic properties. Winter et al. (2010) demonstrated that reactive oxygen species released as a result of _Salmonella_-induced inflammation react with luminal thiosulfate to produce tetrathionate. Tetrathionate can then be used as a terminal electron acceptor for Salmonella spp. respiration, allowing for more efficient energy production relative to competing, fermenting microflora. Tetrathionate has been used since the early 1920s as an enrichment for Salmonella spp. in mixed microbial samples. Thus, the ability to overcome colonization resistance may reside in its ability to utilize inflammation-induced compounds to enhance growth.

In a similar vein, inflammation also releases or induces the expression of high-energy nutrients such as mucin and galactose-containing molecules found in the cecum and elsewhere in the gut (Stecher et al., 2008). It was shown that S. Typhimurium flagellar and chemotaxis mutants had reduced fitness in the inflamed but not the non-inflamed gut. It was reasoned that motility and the ability to chemotax allowed S. Typhimurium to utilize specific carbohydrates to both help continue the inflammation and to outgrow the microbiota. Thus, inflammation can result in the release of carbohydrates, which Salmonella spp. can use to aid growth if it possesses intact chemotactic and motility properties.

In a move away from the gut bacterial metabolic capabilities, a recent study has looked at host metabolic changes during Salmonella spp. intestinal infection (Antunes et al., 2011). Using sophisticated mass spectrometry methods, they determined that numerous metabolic pathways were affected, most prominently hormonal pathways such as those affecting steroid and eicosanoid synthesis. Such hormonal pathways have dramatic effects on the host, including wound healing, sugar metabolism, and immune system regulation. It is likely that some of these changes are a direct result of _Salmonella_-induced inflammation while others may be a result of the altered microbiota.

Antibiotics, Normal Flora, and Salmonella spp. Infection

Antibiotics target certain classes of microbes, with many antibiotics having dramatic effects on the intestinal microbiota after administration to a host. Several studies (examples outlined below) have been completed examining the effect of antibiotics on the intestinal flora, and the effect that this flora disruption has on Salmonella spp. colonization and disease as well as the host intestinal metabolome (Antunes et al., 2011). Recently, clinically relevant doses of antibiotics were shown to affect the ratio of microbial phyla in the intestine but not the overall bacterial load (Lupp et al., 2007; Sekirov et al., 2008). Other studies have found that different antibiotics have variable effects on the total number and distribution of gut bacteria, but that each antibiotic tested enhanced _Salmonella_-induced epithelial cell invasion and inflammation (Croswell et al., 2009). After antibiotic removal and some recovery of the microbiota, mice were still susceptible to _Salmonella_-induced enteritis, suggesting that the correct balance of microbial diversity and numbers are required for effective colonization resistance. Furthermore, it was recently demonstrated that growth and dissemination of S. Typhimurium DT104 during antibiotic (fosfomycin) treatment could be abrogated by continuous feeding of some, but not all, Lactobacillus species (a probiotic approach; Asahara et al., 2011). This protective capacity was found to be associated primarily with increased organic acid production and maintenance of a decreased intestinal pH. Thus, alteration of the microbiota by the administration of antibiotics or probiotics can have dramatic effects on _Salmonella-_associated disease.

Salmonella spp. Can Detect Other Microbes to Affect Pathogenesis

Salmonella Typhimurium has the ability to detect the _N_-acyl-l-homoserine lactone (AHL) signaling molecules of other microbes using SdiA, a LuxR homolog (Michael et al., 2001; Smith and Ahmer, 2003; Soares and Ahmer, 2011). Salmonella spp. cannot synthesize AHLs so this system is exclusively for detecting other microbes. Surprisingly, AHLs have not been found in the GI tract of healthy mammals, with the exception of the bovine rumen (Erickson et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2008; Edrington et al., 2009; Hughes et al., 2010). However, SdiA activity was detected in turtles colonized by Aeromonas hydrophila and in mice colonized by Yersinia enterocolitica (Smith et al., 2008; Dyszel et al., 2010). Both of these organisms are AHL-producing pathogens. In _Yersinia_-infected mice, the SdiA activity was primarily observed in the Peyer's patches (Dyszel et al., 2010). In competition with wildtype, an sdiA mutant had no apparent fitness defect, but this may have been due to the small percentage of S. Typhimurium detecting AHLs at any given time. When S. Typhimurium was engineered to produce AHLs, the wildtype was much more fit than the sdiA mutant. All members of the SdiA regulon were required for the fitness phenotype indicating that all of the regulon members are functional in mice (Dyszel et al., 2010). To date, the SdiA regulon consists of only two loci the rck operon, which contains six genes, and srgE (Ahmer et al., 1998; Smith and Ahmer, 2003). Rck is an outer membrane protein that confers resistance to complement killing, adhesion, and invasion of host cells (Ho et al., 2010; Rosselin et al., 2010). The SrgE protein is predicted to be a T3SS secreted effector protein with a coiled-coil domain (Samudrala et al., 2009). Why these genes are important to Salmonella spp. in the presence of AHLs is not known. It is also not known if this system is used to detect a specific AHL-producing pathogen, such as Y. enterocolitica, in a specific host, or if the system is more general and fitness benefits are achieved from detecting any of a number of AHL-producing pathogens in a variety of hosts.

As described above, the normal microbiota produces high concentrations of SCFAs as a byproduct of metabolism (Cummings et al., 1987). These SCFAs are a significant nutrient source for the host and other members of the microbiota and S. Typhimurium regulates virulence genes in response to these SCFAs (Lawhon et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2008; Sartor, 2008). It appears that the two-component regulatory system SirA/BarA may be responsible for the detection of SCFAs (Chavez et al., 2010). BarA is a histidine sensor kinase that phosphorylates the response regulator SirA (Pernestig et al., 2001). SirA then regulates the transcription of two small RNAs that function to bind and prevent the function of the RNA binding protein CsrA (Suzuki et al., 2002). CsrA regulates numerous genes involved in metabolism, virulence, and biofilm formation (Babitzke and Romeo, 2007; Babitzke et al., 2009). SirA also directly regulates the fim operon that encodes Type 1 fimbriae (Teplitski et al., 2006). Because S. Typhimurium produces SCFAs during growth in vitro, the BarA/SirA system is active in pure culture in late exponential phase. The detection of SCFAs by S. Typhimurium in vitro could be considered quorum sensing while its detection of SCFAs in the GI tract could be considered interspecies signaling. However, acetate is also a metabolic byproduct and a carbon source, depending on the circumstances (Wolfe, 2005), so it is probably more accurate to think about the detection of SCFAs by S. Typhimurium as metabolic regulation rather than communication.

Concluding Thoughts

As a GI pathogen, ingested Salmonella spp. must overcome a gauntlet of host defenses in order to colonize and result in human disease. The intestinal microbiota, by a variety of different means, is at the root of this colonization resistance. Future research directed at in depth studies of the Salmonella/microbiota/metabolome/innate defense interaction with cutting edge methods, as well as directing approaches to use the microbiota as tool to inhibit Salmonella spp. colonization, are keys to limiting salmonellosis and typhoid fever worldwide.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding by the NIH to John S. Gunn (AI043521, AI066208) and Brian M. M. Ahmer (AI073971).

References

- Abrahams G. L., Hensel M. (2006). Manipulating cellular transport and immune responses: dynamic interactions between intracellular Salmonella enterica and its host cells. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 728–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abreu M. T. (2010). Toll-like receptor signalling in the intestinal epithelium: how bacterial recognition shapes intestinal function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 131–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann M., Stecher B., Freed N. E., Songhet P., Hardt W. D., Doebeli M. (2008). Self-destructive cooperation mediated by phenotypic noise. Nature 454, 987–990 10.1038/nature07067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmer B. M. M., Reeuwijk J. V., Timmers C. D., Valentine P. J., Heffron F. (1998). Salmonella typhimurium encodes an SdiA homolog, a putative quorum sensor of the LuxR family, that regulates genes on the virulence plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 180, 1185–1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes L. C., Arena E. T., Menendez A., Han J., Ferreira R. B., Buckner M. M., Lolic P., Madilao L. L., Bohlmann J., Borchers C. H., Finlay B. B. (2011). The impact of Salmonella infection on host hormone metabolism revealed by metabolomics. Infect. Immun. 79, 1759–1769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes L. C., Han J., Ferreira R. B., Lolic P., Borchers C. H., Finlay B. B. (2011). The effect of antibiotic treatment on the intestinal metabolome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 1494–1503 10.1128/AAC.01664-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T., Shimizu K., Takada T., Kado S., Yuki N., Morotomi M., Tanaka R., Nomoto K. (2011). Protective effect of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota against lethal infection with multi-drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 in mice. J. Appl. Microbiol. 110, 163–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitzke P., Baker C. S., Romeo T. (2009). Regulation of translation initiation by RNA binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63, 27–44 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitzke P., Romeo T. (2007). CsrB sRNA family: sequestration of RNA-binding regulatory proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 156–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F., Ley R. E., Sonnenburg J. L., Peterson D. A., Gordon J. I. (2005). Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science 307, 1915–1920 10.1126/science.1104816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badarinarayana V., Estep P. W., III, Shendure J., Edwards J., Tavazoie S., Lam F., Church G. M. (2001). Selection analyses of insertional mutants using subgenic-resolution arrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 1060–1065 10.1038/nbt1101-1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barman M., Unold D., Shifley K., Amir E., Hung K., Bos N., Salzman N. (2008). Enteric salmonellosis disrupts the microbial ecology of the murine gastrointestinal tract. Infect. Immun. 76, 907–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell J. M., Goswami T., Evans C. A., Sibthorpe D., Papo N., White J. K., Searle S., Miller E. N., Peacock C. S., Mohammed H., Ibrahim M. (2001). SLC11A1 (formerly NRAMP1) and disease resistance. Cell. Microbiol. 3, 773–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschitz C., Raffatellu M. (2010). Th17 cytokines and the gut mucosal barrier. J. Clin. Immunol. 30, 196–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnhoff M., Drake B. L., Miller C. P. (1954). Effect of streptomycin on susceptibility of intestinal tract to experimental Salmonella infection. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 86, 132–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booijink C. C., Zoetendal E. G., Kleerebezem M., de Vos W. M. (2007). Microbial communities in the human small intestine: coupling diversity to metagenomics. Future Microbiol. 2, 285–295 10.2217/17460913.2.3.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowdish D. M., Davidson D. J., Hancock R. E. (2006). Immunomodulatory properties of defensins and cathelicidins. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 306, 27–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandl K., Plitas G., Mihu C. N., Ubeda C., Jia T., Fleisher M., Schnabl B., DeMatteo R. P., Pamer E. G. (2008). Vancomycin-resistant enterococci exploit antibiotic-induced innate immune deficits. Nature 455, 804–807 10.1038/nature07250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P., Newton K., Lamkanfi M., Mariathasan S., Dixit V. M., Monack D. M. (2010). Redundant roles for inflammasome receptors NLRP3 and NLRC4 in host defense against Salmonella. J. Exp. Med. 207, 1745–1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumann D., Valdivia R. H. (2007). Identification of host-induced pathogen genes by differential fluorescence induction reporter systems. Nat. Protoc. 2, 770–777 10.1038/nprot.2007.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilli A., Beattie D. T., Mekalanos J. J. (1994). Use of genetic recombination as a reporter of gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 2634–2638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilli A., Mekalanos J. J. (1995). Use of recombinase gene fusions to identify Vibrio cholerae genes induced during infection. Mol. Microbiol. 18, 671–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash H. L., Whitham C. V., Behrendt C. L., Hooper L. V. (2006). Symbiotic bacteria direct expression of an intestinal bactericidal lectin. Science 313, 1126–1130 10.1126/science.1127119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri R. R., Peters S. E., Pleasance S. J., Northen H., Willers C., Paterson G. K., Cone D. B., Allen A. G., Owen P. J., Shalom G., Stekel D. J., Charles I. G., Maskell D. J. (2009). Comprehensive identification of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium genes required for infection of BALB/c mice. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000529. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez R. G., Alvarez A. F., Romeo T., Georgellis D. (2010). The physiological stimulus for the BarA sensor kinase. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2009–2012 10.1128/JB.01685-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E. K., Lauber C. L., Hamady M., Fierer N., Gordon J. I., Knight R. (2009). Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 326, 1694–1697 10.1126/science.1177486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford R. W., Rosales-Reyes R., Ramírez-Aguilar M. de L., Chapa-Azuela O., Alpuche-Aranda C., Gunn J. S. (2010). Gallstones play a significant role in Salmonella spp. gallbladder colonization and carriage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4353–4358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croswell A., Amir E., Teggatz P., Barman M., Salzman N. H. (2009). Prolonged impact of antibiotics on intestinal microbial ecology and susceptibility to enteric Salmonella infection. Infect. Immun. 77, 2741–2753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump J. A., Mintz E. D. (2010). Global trends in typhoid and paratyphoid fever. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50, 241–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. H., Macfarlane G. T. (1991). The control and consequences of bacterial fermentation in the human colon. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 70, 443–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. H., Macfarlane G. T. (1997). Role of intestinal bacteria in nutrient metabolism. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral. Nutr. 21, 357–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. H., Pomare E. W., Branch W. J., Naylor C. P., Macfarlane G. T. (1987). Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 28, 1221–1227 10.1136/gut.28.10.1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyszel J. L., Smith J. N., Lucas D. E., Soares J. A., Swearingen M. C., Vross M. A., Young G. M., Ahmer B. M. (2010). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium can detect acyl homoserine lactone production by Yersinia enterocolitica in mice. J. Bacteriol. 192, 29–37 10.1128/JB.01139-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckburg P. B., Bik E. M., Bernstein C. N., Purdom E., Dethlefsen L., Sargent M., Gill S. R., Nelson K. E., Relman D. A. (2005). Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 308, 1635–1638 10.1126/science.1110591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edrington T. S., Farrow R. L., Sperandio V., Hughes D. T., Lawrence T. E., Callaway T. R., Anderson R. C., Nisbet D. J. (2009). Acyl-homoserine-lactone autoinducer in the gastrointestinal [corrected] tract of feedlot cattle and correlation to season, E. coli O157:H7 prevalence, and diet. Curr. Microbiol. 58, 227–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson D. L., Nsereko V. L., Morgavi D. P., Selinger L. B., Rode L. M., Beauchemin K. A. (2002). Evidence of quorum sensing in the rumen ecosystem: detection of _N_-acyl homoserine lactone autoinducers in ruminal contents. Can. J. Microbiol. 48, 374–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith J. J., Rey F. E., O'Donnell D., Karlsson M., McNulty N. P., Kallstrom G., Goodman A. L., Gordon J. I. (2010). Creating and characterizing communities of human gut microbes in gnotobiotic mice. ISME J. 4, 1094–1098 10.1038/ismej.2010.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk P. G., Hooper L. V., Midtvedt T., Gordon J. I. (1998). Creating and maintaining the gastrointestinal ecosystem: what we know and need to know from gnotobiology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 1157–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firoz Mian M., Pek E. A., Chenoweth M. J., Ashkar A. A. (2010). Humanized mice are susceptible to Salmonella typhi infection. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 8, 83–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank D. N., Pace N. R. (2008). Gastrointestinal microbiology enters the metagenomics era. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 24, 4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher L. A., Shendure J., Manoil C. (2011). Genome-scale identification of resistance functions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa using Tn-seq. MBio 2, e00315–e00310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantois I., Ducatelle R., Pasmans F., Haesebrouck F., Hautefort I., Thompson A., Hinton J. C., Van Immerseel F. (2006). Butyrate specifically down-regulates Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 gene expression. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 946–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner C. D., Antonopoulos D. A., Wagner B., Duhamel G. E., Keresztes I., Ross D. A., Young V. B., Altier C. (2009). Perturbation of the small intestine microbial ecology by streptomycin alters pathology in a Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium murine model of infection. Infect. Immun. 77, 2691–2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godinez I., Raffatellu M., Chu H., Paixao T. A., Haneda T., Santos R. L., Bevins C. L., Tsolis R. M., Baumler A. J. (2009). Interleukin-23 orchestrates mucosal responses to Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium in the intestine. Infect. Immun. 77, 387–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. L., McNulty N. P., Zhao Y., Leip D., Mitra R. D., Lozupone C. A., Knight R., Gordon J. I. (2009). Identifying genetic determinants needed to establish a human gut symbiont in its habitat. Cell Host Microbe 6, 279–289 10.1016/j.chom.2009.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M. A., Kankwatira A. M., Mwafulirwa G., Walsh A. L., Hopkins M. J., Parry C. M., Faragher E. B., Zijlstra E. E., Heyderman R. S., Molyneux M. E. (2010). Invasive non-typhoid Salmonellae establish systemic intracellular infection in HIV-infected adults: an emerging disease pathogenesis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50, 953–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S. M. (2010). Nontyphoidal salmonellosis in Africa. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23, 409–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassl G. A., Finlay B. B. (2008). Pathogenesis of enteric Salmonella infections. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 24, 22–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn J. S. (2008). The Salmonella PmrAB regulon: lipopolysaccharide modifications, antimicrobial peptide resistance and more. Trends Microbiol. 16, 284–290 10.1016/j.tim.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Lim K. B., Gunn J. S., Bainbridge B., Darveau R. P., Hackett M., Miller S. I. (1997). Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science 276, 250–253 10.1126/science.276.5310.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Lim K. B., Poduje C. M., Daniel M., Gunn J. S., Hackett M., Miller S. I. (1998). Lipid A acylation and bacterial resistance against vertebrate antimicrobial peptides. Cell 95, 189–198 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81750-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson B. E. (1982). The physiological importance of the colonic microflora. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 77, 117–131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handelsman J. (2004). Metagenomics: application of genomics to uncultured microorganisms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 669–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapfelmeier S., Hardt W. D. (2005). A mouse model for _S. typhimurium_-induced enterocolitis. Trends Microbiol. 13, 497–503 10.1016/j.tim.2005.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett L., Wu M. (2011). Defensins in innate immunity. Cell Tissue Res. 343, 175–188 10.1007/s00441-010-1022-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heithoff D. M., Conner C. P., Hanna P. C., Julio S. M., Hentschel U., Mahan M. J. (1997). Bacterial infection as assessed by in vivo gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 934–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho D. K., Jarva H., Meri S. (2010). Human complement factor H binds to outer membrane protein Rck of Salmonella. J. Immunol. 185, 1763–1769 10.4049/jimmunol.1001244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper L. V., Gordon J. I. (2001). Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science 292, 1115–1118 10.1126/science.1058709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper L. V., Stappenbeck T. S., Hong C. V., Gordon J. I. (2003). Angiogenins: a new class of microbicidal proteins involved in innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 4, 269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Suyemoto M., Garner C. D., Cicconi K. M., Altier C. (2008). Formate acts as a diffusible signal to induce Salmonella invasion. J. Bacteriol. 190, 4233–4241 10.1128/JB.00205-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. T., Terekhova D. A., Liou L., Hovde C. J., Sahl J. W., Patankar A. V., Gonzalez J. E., Edrington T. S., Rasko D. A., Sperandio V. (2010). Chemical sensing in mammalian host-bacterial commensal associations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 9831–9836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iimura M., Gallo R. L., Hase K., Miyamoto Y., Eckmann L., Kagnoff M. F. (2005). Cathelicidin mediates innate intestinal defense against colonization with epithelial adherent bacterial pathogens. J. Immunol. 174, 4901–4907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B., Richards S. M., Gunn J. S., Slauch J. M. (2010). Protecting against antimicrobial effectors in the phagosome allows SodCII to contribute to virulence in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2140–2149 10.1128/JB.00016-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley R. A., Msefula C. L., Thomson N. R., Kariuki S., Holt K. E., Gordon M. A., Harris D., Clarke L., Whitehead S., Sangal V., Marsh K., Achtman M., Molyneux M. E., Cormican M., Parkhill J., MacLennan C. A., Heyderman R. S., Dougan G. (2009). Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella Typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have a distinct genotype. Genome Res. 19, 2279–2287 10.1101/gr.091017.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawhon S. D., Maurer R., Suyemoto M., Altier C. (2002). Intestinal short-chain fatty acids alter Salmonella typhimurium invasion gene expression and virulence through BarA/SirA. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 1451–1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawley T. D., Chan K., Thompson L. J., Kim C. C., Govoni G. R., Monack D. M. (2006). Genome-wide screen for Salmonella genes required for long-term systemic infection of the mouse. PLoS Pathog. 2, e11. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. K., Mazmanian S. K. (2010). Has the microbiota played a critical role in the evolution of the adaptive immune system? Science 330, 1768–1773 10.1126/science.1195568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehotzky R. E., Partch C. L., Mukherjee S., Cash H. L., Goldman W. E., Gardner K. H., Hooper L. V. (2010). Molecular basis for peptidoglycan recognition by a bactericidal lectin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 7722–7727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R. E., Lozupone C. A., Hamady M., Knight R., Gordon J. I. (2008). Worlds within worlds: evolution of the vertebrate gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 776–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R. E., Peterson D. A., Gordon J. I. (2006). Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine. Cell 124, 837–848 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby S. J., Brehm M. A., Greiner D. L., Shultz L. D., McClelland M., Smith K. D., Cookson B. T., Karlinsey J. E., Kinkel T. L., Porwollik S., Canals R., Cummings L. A., Fang F. C. (2010). Humanized nonobese diabetic-scid IL2rgammanull mice are susceptible to lethal Salmonella Typhi infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15589–15594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievin-Le Moal V., Servin A. L. (2006). The front line of enteric host defense against unwelcome intrusion of harmful microorganisms: mucins, antimicrobial peptides, and microbiota. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19, 315–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo M. J., Michalski J., Martinez-Wilson H., Morin C., Hilton T., Osorio C. G., Nataro J. P., Tacket C. O., Camilli A., Kaper J. B. (2007). An in vivo expression technology screen for Vibrio cholerae genes expressed in human volunteers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18229–18234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupp C., Robertson M. L., Wickham M. E., Sekirov I., Champion O. L., Gaynor E. C., Finlay B. B. (2007). Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host Microbe 2, 119–129 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson A. J., Slack E. (2007). The functional interactions of commensal bacteria with intestinal secretory IgA. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 23, 673–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson A. J., Uhr T. (2004). Induction of protective IgA by intestinal dendritic cells carrying commensal bacteria. Science 303, 1662–1665 10.1126/science.1091334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahan M. J., Slauch J. M., Mekalanos J. J. (1993). Selection of bacterial virulence genes that are specifically induced in host tissues. Science 259, 686–688 10.1126/science.8430319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahan M. J., Tobias J. W., Slauch J. M., Hanna P. C., Collier R. J., Mekalanos J. J. (1995). Antibiotic-based selection for bacterial genes that are specifically induced during infection of a host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 669–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merighi M., Ellermeier C. D., Slauch J. M., Gunn J. S. (2005). Resolvase – in vivo expression technology analysis of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoP and PmrA regulons in BALB/c mice. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7407–7416 10.1128/JB.187.21.7407-7416.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Hoffert U., Hornef M. W., Henriques-Normark B., Axelsson L. G., Midtvedt T., Putsep K., Andersson M. (2008). Secreted enteric antimicrobial activity localises to the mucus surface layer. Gut 57, 764–771 10.1136/gut.2007.141481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael B., Smith J. N., Swift S., Heffron F., Ahmer B. M. (2001). SdiA of Salmonella enterica is a LuxR homolog that detects mixed microbial communities. J. Bacteriol. 183, 5733–5742 10.1128/JB.183.19.5733-5742.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. P., Bohnhoff M. (1963). Changes in the mouse's enteric microflora associated with enhanced susceptibility to Salmonella infection following streptomycin treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 113, 59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monack D. M., Bouley D. M., Falkow S. (2004). Salmonella typhimurium persists within macrophages in the mesenteric lymph nodes of chronically infected Nramp1+/+ mice and can be reactivated by IFNgamma neutralization. J. Exp. Med. 199, 231–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry J. P., Sassetti C. M., Lane J. M., Xie Z., Rubin E. J. (2008). Transposon site hybridization in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Methods Mol. Biol. 416, 45–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardi R. M., Silva M. E., Vieira E. C., Bambirra E. A., Nicoli J. R. (1989). Intragastric infection of germfree and conventional mice with Salmonella typhimurium. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 22, 1389–1392 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu J., Lorca G., Kingma S. D., Triplett E. W. (2010). The intestinal microbiome: relationship to type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 39, 563–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel J. T., Joy J., Smith J. N., Fatica M., Schneider K. R., Ahmer B. M., Teplitski M. (2010). Salmonella SdiA recognizes _N_-acyl homoserine lactone signals from Pectobacterium carotovorum in vitro, but not in a bacterial soft rot. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 273–282 10.1094/MPMI-23-3-0273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opijnen T., Camilli A. (2010). Genome-wide fitness and genetic interactions determined by Tn-seq, a high-throughput massively parallel sequencing method for microorganisms. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. Chapter 1, Unit1E.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio C. G., Crawford J. A., Michalski J., Martinez-Wilson H., Kaper J. B., Camilli A. (2005). Second-generation recombination-based in vivo expression technology for large-scale screening for Vibrio cholerae genes induced during infection of the mouse small intestine. Infect. Immun. 73, 972–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette A. J. (2010). Paneth cells and innate mucosal immunity. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 26, 547–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernestig A. K., Melefors O., Georgellis D. (2001). Identification of UvrY as the cognate response regulator for the BarA sensor kinase in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 225–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prost L. R., Sanowar S., Miller S. I. (2007). Salmonella sensing of anti-microbial mechanisms to promote survival within macrophages. Immunol. Rev. 219, 55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J., Li R., Raes J., Arumugam M., Burgdorf K. S., Manichanh C., Nielsen T., Pons N., Levenez F., Yamada T., Mende D. R., Li J., Xu J., Li S., Li D., Cao J., Wang B., Liang H., Zheng H., Xie Y., Tap J., Lepage P., Bertalan M., Batto J. M., Hansen T., Le Paslier D., Linneberg A., Nielsen H. B., Pelletier E., Renault P., Sicheritz-Ponten T., Turner K., Zhu H., Yu C., Li S., Jian M., Zhou Y., Li Y., Zhang X., Li S., Qin N., Yang H., Wang J., Brunak S., Doré J., Guarner F., Kristiansen K., Pedersen O., Parkhill J., Weissenbach J., MetaHIT Consortium. Bork P., Ehrlich S. D., Wang J. (2010). A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464, 59–65 10.1038/nature08821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que J. U., Hentges D. J. (1985). Effect of streptomycin administration on colonization resistance to Salmonella typhimurium in mice. Infect. Immun. 48, 169–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabsch W., Tschape H., Baumler A. J. (2001). Non-typhoidal salmonellosis: emerging problems. Microbes Infect. 3, 237–247 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01375-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffatellu M., Bäumler A. J. (2010). _Salmonella_’s iron armor for battling the host and its microbiota. Gut Microbes 1, 70–72 10.4161/gmic.1.1.10951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffatellu M., George M. D., Akiyama Y., Hornsby M. J., Nuccio S. P., Paixao T. A., Butler B. P., Chu H., Santos R. L., Berger T., Mak T. W., Tsolis R. M., Bevins C. L., Solnick J. V., Dandekar S., Bäumler A. J. (2009). Lipocalin-2 resistance confers an advantage to Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium for growth and survival in the inflamed intestine. Cell Host Microbe 5, 476–486 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raqib R., Sarker P., Bergman P., Ara G., Lindh M., Sack D. A., Nasirul Islam K. M., Gudmundsson G. H., Andersson J., Agerberth B. (2006). Improved outcome in shigellosis associated with butyrate induction of an endogenous peptide antibiotic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9178–9183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S. M., Strandberg K. L., Gunn J. S. (2010). _Salmonella_-regulated lipopolysaccharide modifications. Subcell. Biochem. 53, 101–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosselin M., Virlogeux-Payant I., Roy C., Bottreau E., Sizaret P. Y., Mijouin L., Germon P., Caron E., Velge P., Wiedemann A. (2010). Rck of Salmonella enterica, subspecies enterica serovar enteritidis, mediates zipper-like internalization. Cell Res. 20, 647–664 10.1038/cr.2010.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzman N. H., Chou M. M., de Jong H., Liu L., Porter E. M., Paterson Y. (2003). Enteric Salmonella infection inhibits Paneth cell antimicrobial peptide expression. Infect. Immun. 71, 1109–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzman N. H., Hung K., Haribhai D., Chu H., Karlsson-Sjoberg J., Amir E., Teggatz P., Barman M., Hayward M., Eastwood D., Stoel M., Zhou Y., Sodergren E., Weinstock G. M., Bevins C. L., Williams C. B., Bos N. A. (2010). Enteric defensins are essential regulators of intestinal microbial ecology. Nat. Immunol. 11, 76–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samudrala R., Heffron F., McDermott J. E. (2009). Accurate prediction of secreted substrates and identification of a conserved putative secretion signal for type III secretion systems. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000375. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez B., Urdaci M. C., Margolles A. (2010). Extracellular proteins secreted by probiotic bacteria as mediators of effects that promote mucosa-bacteria interactions. Microbiology 156, 3232–3242 10.1099/mic.0.044057-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiviago C. A., Reynolds M. M., Porwollik S., Choi S. H., Long F., Andrews-Polymenis H. L., McClelland M. (2009). Analysis of pools of targeted Salmonella deletion mutants identifies novel genes affecting fitness during competitive infection in mice. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000477. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos R. L., Raffatellu M., Bevins C. L., Adams L. G., Tukel C., Tsolis R. M., Baumler A. J. (2009). Life in the inflamed intestine, Salmonella style. Trends Microbiol. 17, 498–506 10.1016/j.tim.2009.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor R. B. (2008). Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 134, 577–594 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti C. M., Boyd D. H., Rubin E. J. (2001). Comprehensive identification of conditionally essential genes in mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12712–12717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E., Hoekstra R. M., Angulo F. J., Tauxe R. V., Widdowson M. A., Roy S. L., Jones J. L., Griffin P. M. (2011). Foodborne illness acquired in the United States – major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 7–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekirov I., Gill N., Jogova M., Tam N., Robertson M., de Llanos R., Li Y., Finlay B. B. (2010). Salmonella SPI-1-mediated neutrophil recruitment during enteric colitis is associated with reduction and alteration in intestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 1, 30–41 10.4161/gmic.1.1.10950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekirov I., Tam N. M., Jogova M., Robertson M. L., Li Y., Lupp C., Finlay B. B. (2008). Antibiotic-induced perturbations of the intestinal microbiota alter host susceptibility to enteric infection. Infect. Immun. 76, 4726–4736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slauch J. M., Mahan M. J., Mekalanos J. J. (1994). In vivo expression technology for selection of bacterial genes specifically induced in host tissues. Meth. Enzymol. 235, 481–492 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35164-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. M., Heisler L. E., St Onge R. P., Farias-Hesson E., Wallace I. M., Bodeau J., Harris A. N., Perry K. M., Giaever G., Pourmand N., Nislow C. (2010). Highly-multiplexed barcode sequencing: an efficient method for parallel analysis of pooled samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. N., Ahmer B. M. (2003). Detection of other microbial species by Salmonella: expression of the SdiA regulon. J. Bacteriol. 185, 1357–1366 10.1128/JB.185.4.1357-1366.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. N., Dyszel J. L., Soares J. A., Ellermeier C. D., Altier C., Lawhon S. D., Adams L. G., Konjufca V., Curtiss R., III, Slauch J. M., Ahmer B. M. (2008). SdiA, an _N_-acylhomoserine lactone receptor, becomes active during the transit of Salmonella enterica through the gastrointestinal tract of turtles. PLoS ONE 3, e2826. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares J. A., Ahmer B. M. (2011). Detection of acyl-homoserine lactones by Escherichia and Salmonella. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 188–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Willinger T., Rongvaux A., Eynon E. E., Stevens S., Manz M. G., Flavell R. A., Galán J. E. (2010). A mouse model for the human pathogen Salmonella typhi. Cell Host Microbe 8, 369–376 10.1016/j.chom.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B., Barthel M., Schlumberger M. C., Haberli L., Rabsch W., Kremer M., Hardt W. D. (2008). Motility allows S. Typhimurium to benefit from the mucosal defence. Cell. Microbiol. 10, 1166–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B., Hardt W. D. (2011). Mechanisms controlling pathogen colonization of the gut. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 82–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B., Robbiani R., Walker A. W., Westendorf A. M., Barthel M., Kremer M., Chaffron S., Macpherson A. J., Buer J., Parkhill J., Dougan G., von Mering C., Hardt W. D. (2007). Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium exploits inflammation to compete with the intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 5, 2177–2189 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K., Wang X., Weilbacher T., Pernestig A. K., Melefors O., Georgellis D., Babitzke P., Romeo T. (2002). Regulatory circuitry of the CsrA/CsrB and BarA/UvrY systems of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184, 5130–5140 10.1128/JB.184.18.5130-5140.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam M. A., Rydstrom A., Sundquist M., Wick M. J. (2008). Early cellular responses to Salmonella infection: dendritic cells, monocytes, and more. Immunol. Rev. 225, 140–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplitski M., Al-Agely A., Ahmer B. M. (2006). Contribution of the SirA regulon to biofilm formation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microbiology 152, 3411–3424 10.1099/mic.0.29118-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsolis R. M., Xavier M. N., Santos R. L., Bäumler A. J. (2011). How to become a top model: The impact of animal experimentation on human Salmonella disease research. Infect. Immun. 79, 1806–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Gordon J. I. (2009). The core gut microbiome, energy balance and obesity. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 587, 4153–4158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacharaksa A., Finlay B. B. (2010). Gut microbiota: metagenomics to study complex ecology. Curr. Biol. 20, R569–R571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia R. H., Falkow S. (1996). Bacterial genetics by flow cytometry: rapid isolation of Salmonella typhimurium acid-inducible promoters by differential fluorescence induction. Mol. Microbiol. 22, 367–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia R. H., Falkow S. (1997). Fluorescence-based isolation of bacterial genes expressed within host cells. Science 277, 2007–2011 10.1126/science.277.5334.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia R. H., Hromockyj A. E., Monack D., Ramakrishnan L., Falkow S. (1996). Applications for green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the study of host-pathogen interactions. Gene, 173, 47–52 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00706-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Waaij D., Berghuis-de Vries J. M., Lekkerkerk L.-V. (1971). Colonization resistance of the digestive tract in conventional and antibiotic-treated mice. J. Hyg. (Lond.) 69, 405–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Opijnen T., Bodi K. L., Camilli A. (2009). Tn-seq: high-throughput parallel sequencing for fitness and genetic interaction studies in microorganisms. Nat. Methods 6, 767–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Torres A., Fang F. C. (2001). Salmonella evasion of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase. Microbes Infect. 3, 1313–1320 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01492-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuizen E. J., Koomen I., Ultee T., van Dijk A., Haagsman H. P. (2009). Salmonella serovar specific upregulation of porcine defensins 1 and 2 in a jejunal epithelial cell line. Vet. Microbiol. 136, 69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura M., Turroni F., Canchaya C., Vaughan E. E., O'Toole P. W., van Sinderen D. (2009). Microbial diversity in the human intestine and novel insights from metagenomics. Front. Biosci. 14, 3214–3221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Antonopoulos D. A., Zhu X., Harrell L., Hanan I., Alverdy J. C., Meyer F., Musch M. W., Young V. B., Chang E. B. (2010). Laser capture microdissection and metagenomic analysis of intact mucosa-associated microbial communities of human colon. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 88, 1333–1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willing B. P., Dicksved J., Halfvarson J., Andersson A. F., Lucio M., Zheng Z., Järnerot G., Tysk C., Jansson J. K., Engstrand L. (2010). A pyrosequencing study in twins shows that gastrointestinal microbial profiles vary with inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes. Gastroenterology 139, 1844.e1–1854.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter S. E., Thiennimitr P., Winter M. G., Butler B. P., Huseby D. L., Crawford R. W., Russell J. M., Bevins C. L., Adams L. G., Tsolis R. M., Roth J. R., Bäumler A. J. (2010). Gut inflammation provides a respiratory electron acceptor for Salmonella. Nature 467, 426–429 10.1038/nature09415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe A. J. (2005). The acetate switch. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69, 12–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J. M., de Souza R., Kendall C. W., Emam A., Jenkins D. J. (2006). Colonic health: fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 40, 235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D., Chertov O., Oppenheim J. J. (2001). Participation of mammalian defensins and cathelicidins in anti-microbial immunity: receptors and activities of human defensins and cathelicidin (LL-37). J. Leukoc. Biol. 69, 691–697 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young G. M., Miller V. L. (1997). Identification of novel chromosomal loci affecting Yersinia enterocolitica pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 25, 319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff M. (2002). Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415, 389–395 10.1038/415389a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D., Galan J. (2001). Salmonella entry into host cells: the work in concert of type III secreted effector proteins. Microbes Infect. 3, 1293–1298 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01489-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]