GLUTATHIONYLATION OF PEROXIREDOXIN I INDUCES DECAMER TO DIMERS DISSOCIATION WITH CONCOMITANT LOSS OF CHAPERONE ACTIVITY (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2012 Apr 19.

Published in final edited form as: Biochemistry. 2011 Mar 25;50(15):3204–3210. doi: 10.1021/bi101373h

Abstract

Reversible protein glutathionylation, a redox-sensitive regulatory mechanism, plays a key role in cellular regulation and cell signaling. Peroxiredoxins (Prxs), a family of peroxidases that is involved in removing H2O2 and organic hydroperoxides, are known to undergo a functional change from peroxidase to molecular chaperone upon overoxidation of its catalytic cysteine. The functional change is caused by a structural change from low molecular weight oligomers to high molecular weight complexes that possess molecular chaperone activity. We reported earlier that Prx I can be glutathionylated at three of its cysteine residues, Cys52, 83, and 173 [JBC 284, 23364 (2009)]. In this study, using analytical ultracentrifugation analysis, we reveal that glutathionylation of Prx I, WT, or its C52S/C173S double mutant shifted its oligomeric status from decamers to a population consisting mainly of dimers. Cys83 is localized at the putative dimer-dimer interface, implying that the redox status of Cys83 may play an important role in stabilizing the oligomeric state of Prx I. Studies with the Prx I (C83S) mutant show that while Cys83 is not essential for the formation of high molecular weight complexes, it affects the dimer-decamer equilibrium. Glutathionylation of the C83S mutant leads to accumulation of dimers and monomers. In addition, glutathionylation of Prx I, both the WT and C52S/C173S mutants, greatly reduces their molecular chaperone activity in protecting citrate synthase from thermally induced aggregation. Together, these results reveal that glutathionylation of Prx I promotes changes in its quaternary structure from decamers to smaller oligomers, and concomitantly inactivates its molecular chaperone function.

Introduction

Glutathione, a major low molecular weight thiol in mammalian cells, has long been considered to be a major redox buffer in maintaining a reduced state of protein thiols in cells (1,2). Protein glutathionylation, greatly elevated under oxidative stress, is considered to be a protective mechanism to prevent protein thiols from being hyperoxidized to their irreversible derivatives, since glutathionylated proteins are readily deglutathionylated in the presence of deglutathionylating enzymes. In recent years, this redox-sensitive, reversible protein covalent modification has emerged as a major regulatory mechanism in cellular regulation and in cell signaling mediated by redox signals known to be generated in response to ligation of various cell surface receptors (3–6). In vitro studies revealed that glutathionylation leads either to inactivation or activation of dozens of enzymes (6–9). However, to date, only a few studies have revealed the glutathionylation-dependent changes in enzyme specific activity or protein cytoskeletal function in a physiological context (7). They include studies of the protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (5, 10), ras (11), mitochondrial complex II (12), and actin (13, 14). Nevertheless, given the fact that glutathione is present in cells in the millimolar range and enzymic activity of a given protein can be altered by its glutathionylation, reversible protein glutathionylation has emerged as a major cellular regulatory mechanism.

Peroxiredoxins (Prxs), a family of peroxidases, known to catalyze the removal of H2O2 and organic hydroperoxides, have the ability to reversibly assemble into a doughnut-shaped homodecamer or even higher-order oligomeric structures (15). Prx I to Prx IV belong to the 2-Cys Prx enzymes, which reduce H2O2 through the use of reducing equivalents provided by thioredoxin (Trx). The peroxidative cysteine, Cys52 for Prx I, is located in the NH2-terminal region. It is selectively oxidized by H2O2 to the cysteine-sulfenic derivative that in turn reacts with the thiol moiety of Cys173(for Prx I) in the COOH-terminal region of a different subunit to form an intersubunit disulfide. The disulfide is then reduced by Trx. During catalysis, the thiol group of the peroxidative cysteine is occasionally overoxidized to sulfinic acid, resulting in the inactivation of its peroxidase activity (16). Recently, it was reported that the formation of high molecular weight complexes is favored when the peroxidatic cysteine is in an overoxidized form due to oxidative stress or heat shock stress (17). The structural change from low molecular weight oligomers to high molecular weight complexes accompanies a functional change from peroxidase to molecular chaperone. The chaperone activity can protect a protein substrate from thermally induced aggregation, resembling the function of heat shock proteins that can also form well-ordered oligomers (17).

In addition, the peroxidase activity of the Prx I and Prx II isoforms is known to be regulated by phosphorylation. On one hand, Prx I is phosphorylated by cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk1 at Thr 90 and causes a greater than 80% decrease in its peroxidase activity (18). On the other hand, Prx II is known to bind Cdk5/p35, which in turn phosphorylates its Thr89 in cells treated with 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion (MPP+) (19). Like Prx I, this Thr phosphorylation also diminishes Prx II peroxidase activity. These observations can be attributed to the introduction of a negative charge by phosphorylation at the Thr residue. Moreover, Jang et al. showed that the mutation of Thr90 to Asp to mimic the phosphorylation status induced a significant increase in chaperone activity and an elevation of the population of high molecular weight oligomers (20).

Based on previous studies, the regulation and switching of the dual functions of Prxs appear to be mediated by posttranslational modifications, such as sulfinylation and phosphorylation. Recently, we showed that Prx I can be glutathionylated at three of its four cysteine residues (21). In this study, we reveal for the first time that glutathionylation can alter the activity a dual-function enzyme, Prx I, mediated through its ability to regulate the oligomeric status of the protein.

Experimental Procedures

Materials- Glutathione disulfide (GSSG) and citrate synthase (CS) from porcine heart were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Preparation of recombinant proteins

Escherichia coli expressing plasmids encoding wild type human Prx I or two mutants, C83S and C52S/C173S, were prepared as described (21). Briefly, cysteine mutants of Prx I were generated by standard PCR-mediated, site-directed mutagenesis using Prx I (WT) as the template. Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring each plasmid were cultured at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml). After the addition of isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (0.4 mM), the cultures were incubated for 3 h at 25°C, then cells were lysed. The recombinant proteins were purified as described (22). It should be pointed out that prior to the last step of the purification procedures, when the protein sample was fractionated with Superdex G200, the purified Prx I was subjected to a 20 min incubation with 10 mM DTT.

Preparation of glutathionylated proteins

Glutathionylation was performed by disulfide exchange with GSSG. Typically, 50 μM of recombinant protein was incubated for 18 hours with 10 mM GSSG at 4°C in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4) buffer containing 100 mM NaCl. It should be pointed out that when the unmodified Prx I was incubated in the same buffer without the presence of GSSG for the equivalent period of time, no spontaneous denaturation of Prx I was detected. After the reaction, excess GSSG was removed using either size exclusion chromatography (TSK-GEL G3000SW; TOSOH Corp., Tokyo, Japan) or strong anion exchange chromatography (TSK Super Q-5PW; TOSOH TOSOH). The glutathionylated proteins were identified using reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) mass spectrometric methods as previously described (21).

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation velocity experiments were conducted with a Beckman Optima XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman, Palo Alto, CA) equipped with a four-hole An60Ti rotor and cells with 12 mm double-sector epon centerpieces, and sapphire windows. Proteins were dialyzed overnight in the experimental buffer containing 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, with or without 10 mM GSSG. For all experiments, 0.4 ml of the protein sample and dialysate buffer were loaded into sample and reference centerpiece channels, respectively. The rotor was accelerated to 50,000 rpm after thermal equilibrium was reached at 20°C at rest (typically 1 h). Interference and absorbance scans were started immediately after the rotor reached the set speed and collected until no further sedimentation boundary movement was observed. To obtain optical density (OD) values within the recommended signal range of 0.05 OD to 1.5 OD (23), the absorption of low concentration samples was measured at 230 nm. For high concentration samples absorption at 280 nm and the interference signal was used. OD of the WT Prx I measured with the XL-I equipped with a 12 mm pathlength cell was 1.2 OD for the 50 μM sample at 280 nm and 0.05 OD for the 0.2 μM sample at 230 nm, respectively. Density and viscosity of the buffer was determined with the DMA-58 densitometer and AMVn viscometer (Anton-PAAR KG, Graz, Austria). Partial specific volumes were determined from amino acid composition using SEDNTERP program (24). Data analysis was conducted using the c(s)/c(M) or ls-g*(s) method in Peter Schuck’s software program SEDFIT (23, 25). The same program was used to calculate weight average sedimentation coefficients from distributions and to convert the sedimentation coefficients to values at standard conditions of 20°C in water, s20,w in Svedberg units. Menisci positions and frictional ratios were optimized during the fitting procedure. The final accepted fits had standard deviations of less than 0.009 units.

Glutathionylation of Prx I and Prx II in Hela cells induced by H2O2

HeLa (human cervical adenocarcinoma) cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassa, VA) (ATCC number CCL-2™) and maintained in Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Glutathionylation was monitored with the biotinylated glutathione using its membrane-permeable derivative, BioGEE (biotinylated glutathione ethyl ester), prepared as described previously (26). HeLa cells were incubated with 250 μM BioGEE for 1 h prior to H2O2 treatment. The soluble proteins covalently bound to biotin were extracted with streptavidin-agarose. The agarose beads were washed three times with radioimmune precipitated buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, and 50mM Tris, pH 8.0) and twice with phosphate-buffered saline containing 2 mM EDTA and 0.1% SDS. Proteins bound to streptavidin via a disulfide bond were then eluted from the beads by incubation for 30 min with phosphate-buffered saline/EDTA/SDS containing 10 mM DTT. Proteins in the eluent were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blotting.

Chaperone activity assay

Chaperone activity of Prx I was analyzed by measuring its ability to inhibit thermally induced aggregation of substrate protein, citrate synthase (CS) in a pH 7.4 buffer containing 50 mM Tris/HCl and 100 mM NaCl. The reaction was initiated by adding 0.1 ml of protein sample, containing CS in the presence or absence of Prx I WT or mutants, to a preheated (45°C) reaction cuvette containing 1.4 ml Tris buffer solution. Protein aggregation was monitored by measuring the light scattering using a spectrofluorometer, equipped with a thermostatic cell holder, at 360 nm (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ). In the case of the glutathionylated Prx I (WT) sample, it contains a residual GSSG due to technical difficulties in removing GSSG without affecting disulfide bond formation between cysteine residues in Prx I.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The effect of glutathionylation on the oligomeric state of WT Prx I and its (C52S/C173S) and (C83S) mutants

Human Prx I is known to reversibly assemble into homodecamers or even higher-order oligomeric structures (15). We showed that of the four cysteine residues, Cys52, 83, and 173 can be glutathionylated, and the deglutathionylation is catalyzed specifically by sulfiredoxin (21). To investigate the effect of protein glutathionylation on the oligomeric status of Prx I sedimentation velocity (SV) experiments were carried out with the glutathionylated and nonglutathionylated recombinant Prx I, WT as well as its C52S/C173S and C83S mutants. The purified recombinant Prx I, either the WT, C52S/C173S or C83S mutant, contains neither a glutathionylated nor an oxidized derivative based on the fact that the LC-MS analysis revealed only one peak with a molecular mass essentially identical to the theoretical mass of the non-modified WT Prx I and its mutants. The calculated mass are 21979.2, 21947.0 and 21963.1 Da for the WT, C52S/C173S, and C83S mutants, and the observed mass are 21978.4, 21947.1, and 21963.9 Da, respectively.

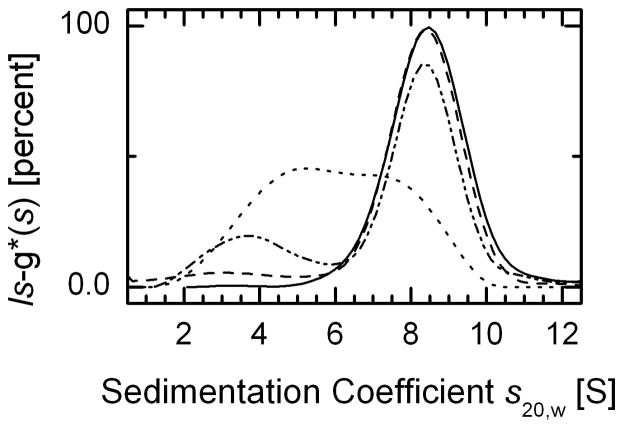

The amount of Prx I measured in 13 different mammalian cell lines is in the range of 1–4 μg per mg of soluble proteins (27), which translates to 15–60 μM. Thus, sedimentation velocity experiments were carried out primarily with 50 μM of Prx I. The solid line in Fig. 1 and in Fig. 2A shows that at 50 μM 97% of the WT Prx I sediments as a single species. The data can be described by a single peak in the c(s) sedimentation coefficient distribution analysis. The averaged _s_20,w of the peak is 8.5 S, taken together with the frictional ratio obtained from fitting the broadening of the sedimentation boundary, corresponds to a molar mass of 220.6 kDa, and compares well with the mass of Prx I decamer. The decamer has a molar mass of 221.1 kDa. Figure 1 also depicts the concentration dependence of the SV profiles for the WT Prx I. To compare both the shift and width of the decameric peaks, these data were analyzed in terms of the least squares sedimentation coefficient distribution (ls-g*(s)), since at lower protein concentrations the c(s) distribution peak may be broadened due to the decrease in signal to noise ratio. The data obtained with 5 μM WT Prx I show the position of the decameric peak to be identical to that obtained with 50 μM protein. When the concentration of Prx I was set at 2 μM, the main peak of the ls-g*(s) distribution shows a small shift to a lower S, with an averaged _s_20,w value of 8.38 S. At this concentration, the ls-g*(s) profile also shows a small second peak with an averaged _s_20,w value of 3.8 S, representing 23% of the loaded protein. This is reminiscent of the theoretical predictions from Gilbert-Jenkins theory of bimodal reaction boundaries of rapidly oligomerizing systems with n larger than 2. At 0.2 μM Prx I, the ls-g*(s) profile exhibits a very broad peak, further indicating a dynamic equilibrium between the decamer and smaller species. The profile indicates that relative to the time-scale of sedimentation, the oligomerization reaction is rapid, and at low concentrations the high S value peak represents the reaction boundary (28). To determine whether the 8.5 S peak obtained at 50 μM of Prx I represents a limiting size of the oligomer, the s20,w values of the peaks obtained at different protein concentrations were extrapolated to infinite concentration by plotting 1/s20,w versus 1/c, where c represents the protein concentration. The extrapolated value was 8.5 S within the uncertainty of the measurements. In parallel, it can be easily shown mathematically that, under conditions of virtual saturation, the broadening of reaction boundaries from rapid self-associating systems asymptotically approaches the diffusional broadening of the complex species, in a manner analogous to the reaction boundaries of a hetero-associating system (28). Thus, as one would expect, this saturation condition allows the complex molar mass to be determined with the c(M) model, which suggests that the largest oligomer is the decamer. Together, these data imply that the dissociation constant for the WT Prx I decamer is in the submicromolar range, two orders of magnitude lower than the cellular concentrations of Prx I. Thus, all consecutive SV measurements were performed at 50 μM protein concentration.

Fig. 1. Concentration dependence of sedimentation velocity profiles for purified WT Prx I.

The normalized ls-g*(s), obtained as described in Experimental Procedures, was plotted as a function of sedimentation coefficients corrected to s20,w values. The concentrations of WT Prx I used were: 50 μM (solid line), 5 μM (dashed line), 2 μM (dash-dot-dot-dashed line), and 0.2 μM (short dashed line)

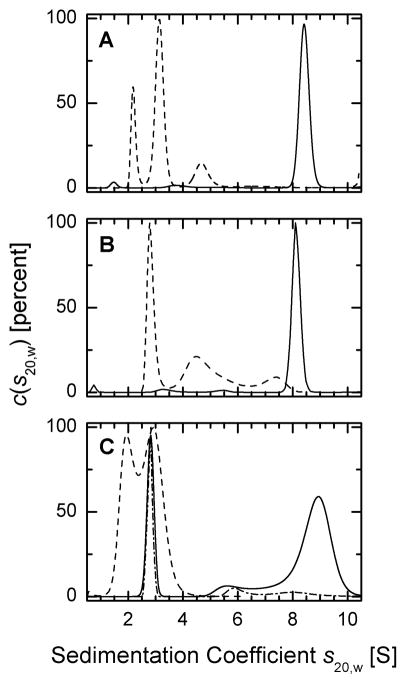

Fig. 2. Analysis of the oligomeric status of Prx I by sedimentation velocity methods.

Sedimentation coefficients distributions were corrected to standard conditions and the c(s20,w) profiles were plotted as a function of sedimentation coefficient. Experiments with glutathionylated proteins at 50 μM were carried out in a buffer containing 10 mM GSSG (see Experimental Procedures). (A) sedimentation coefficient distribution of reduced (solid line) and glutathionylated (dashed line) WT Prx I, (B) reduced (solid line) and glutathionylated (dashed line) Prx I (C52S/C173S) double mutant, (C) 50 μM reduced (solid line), 10 μM reduced (dash-dot-dashed line), and glutathionylated (dashed line) Prx I (C83S) mutant.

Unlike the reduced form of Prx I, the SV profile of the glutathionylated WT Prx I exhibits a distinctly different sedimentation coefficient distribution with three main peaks in the range of 2 to 5 S (Fig. 2A). The SV profile indicates that glutathionylation disrupts the oligomerization of Prx I in such a way that the decameric population, which represents 97% of the total reduced form of Prx I, was totally eliminated even at 50 μM protein concentration. Instead, the glutathionylated Prx I was converted mainly to small oligomeric species present in the state of dynamic equilibrium. The S-value of the second peak is similar to the value of 3.1 S observed with the oxidized cross-linked Prx I dimer (D. Y. Lee and G. Piszczek, data not shown). This corresponds well with the apparent molar mass estimates from c(M) for the first and second peaks of 21 and 38 kDa, respectively, suggesting that the interconversion of species under these conditions may be slow relative to the time-scale of sedimentation. This leads to estimated fractions of 22% monomers and 63% dimers with an average s20,w values of 2.3 and 3.2 S, respectively, with both molecules being fairly hydrodynamically compact. Interestingly, the percentage of the monomer so determined is in agreement with the 24% of triple glutathionylated Prx I monomers revealed by LC-MS analysis of the similarly glutathionylated WT Prx I (21).

Jang et. al. (17) reported that peroxidase activity is not required for cytosolic yeast Prx to function as a molecular chaperone, while its peroxidative cysteine, Cys47, serves as a H2O2-sensor in response to oxidative stress to induce a structural change from a low molecular weight form to a high molecular weight chaperone complex. We investigated the effect of glutathionylation on the oligomeric state of the human Prx I (C52S/C173S) double mutant which has neither the peroxidase activity nor peroxidative cysteine. Figure 2B shows that 94% of the reduced form of Prx I (C52S/C173S) sediments as a single peak with an average _s_20,w value of 8.2 S, consistent with a decamer with slightly higher hydrodynamic friction. However, the glutathionylated form of this double mutant shows a distinctly different sedimentation pattern (Fig. 2B). The decamers were converted to smaller oligomers with the major peak representing 46% of the protein consistent with dimers with a _s_20,w value of 3.0 S in the presence of at least two other boundary components at calculated average _s_20,w values ranging from 5.1 to 7.9 S. The elucidation of the detailed features of the self-association and apparent intermediates is beyond the scope of the present work. The main finding in the present context is that the data unambiguously demonstrate that mono-glutathionylation of the Prx I (C52S/C173S) mutant at Cys 83 also converts the decamer observed with the nonglutathionylated enzyme to a number of lower molecular weight species, with the smallest species being a dimer.

The Cys83 is localized at the putative dimer-dimer interface and its redox status may play a role in stabilizing the oligomeric state of Prx I. Lee et. al. (29) reported recently that a Cys83-Cys83 disulfide bond is formed at each of the five dimer-dimer interfaces of the decamer of Prx I. However, Matsumura et al. (30) had shown that the Cys83-Cys83 disulfide bond formation at the dimer-dimer interfaces is not essential for decamer formation. To address this issue, the Prx I (C83S) mutant was prepared, glutathionylated, and subjected to sedimentation velocity analysis. Figure 2C shows that at 50 μM C83S mutant, 50% of the loaded protein exists as decamers with a small amount of high molecular weight species as depicted by a broad shoulder of the decameric peak. This peak shows an average _s_20,w value of 9.1 S, significantly higher than the values found for the decamers of WT and C52S/C173S double mutant. This high value could be attributed to a more compact shape of the decamer formed by the Prx I(C83S) mutant. Another distinct peak, representing 25% of the loaded C83S mutant, and exhibiting an average _s_20,w value of 2.9 S, is attributed to the dimers. Independent of the details of the oligomerization process, these results clearly indicate that Cys83-Cys83 disulfide bonds are not essential for the formation of high molecular weight oligomer, although the SV profile implies that the dissociation constant for the high molecular weight oligomer of Prx I(C83S) mutant is significantly higher than that observed with either the WT or Prx I (C52S/C173S) double mutant. In addition, like the WT and (C52S/C173S) double mutant, glutathionylation of C83S mutant also induces a conversion of the decamer to a population consisting mainly of dimers and monomers (Fig. 2C).

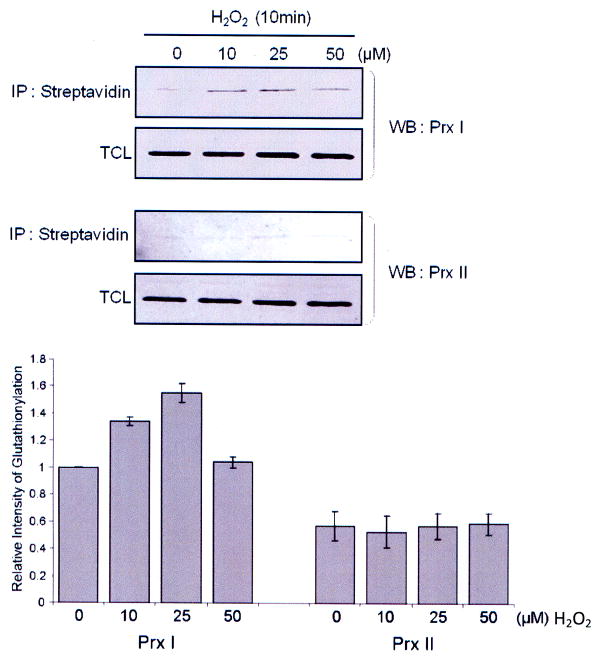

Preferential glutathionylation of Cys83 in cell

To assess the biological relevance of Cys83 glutathionylation in context to our observation showing that glutathionylation of Cys83 alone will lead to the conversion of the decameric Prx I to lower molecular weight species (Fig. 2B), a comparative study on the glutathionylation of Prx I and Prx II was carried out with HeLa cells, based on the fact that Prx I and Prx II show 78% identity in their amino acid sequences and share the same peroxidase catalytic mechanism (31, 32), except that Prx II does not contain Cys83. These conditions provide one a unique situation to investigate whether Cys83 can be glutathionylated selectively in living cells. To monitor glutathionylation of Prx I and II in cells, HeLa cells were pre-treated with a cell-permeable form of GSH, the biotinylated glutathione ethyl ester (BioGEE), followed by treatment with 10 to 50 μM of H2O2 for 10 min (21). The blot analysis of biotinylated proteins shows that relative to Prx I, the glutathionylated Prx II was hardly visible (Fig. 3). This implies that Cys83 is easily accessible for glutathionylation with biotinylated glutathione, but not the peroxidative and the resolving cysteine residues. This observation may explain why glutathione is a poor electron donor for Prx I- and Prx II-catalyzed peroxidation reactions, likely due to the inaccessibility of the catalytic cysteine to glutathione (27).

Fig. 3. Glutathionylation of Prx I and II in H2O2–treated HeLa cells.

To induce glutathionylation with biotinylated glutathione, cells were preincubated with 250 μM BioGEE for 1 h and subsequently exposed to indicated concentration of H2O2 for 10 min. Proteins covalently bound to biotin were extracted using streptavidin agarose then eluted with DTT and subjected to western blot analysis with anti-Prx I (upper panel) or anti-Prx II (middle panel) antibody. Histogram (lower panel) depicts as means +/− S.E. (n=3) from the densitometric analysis.

The effect of glutathionylation on the chaperone activity of Prx I

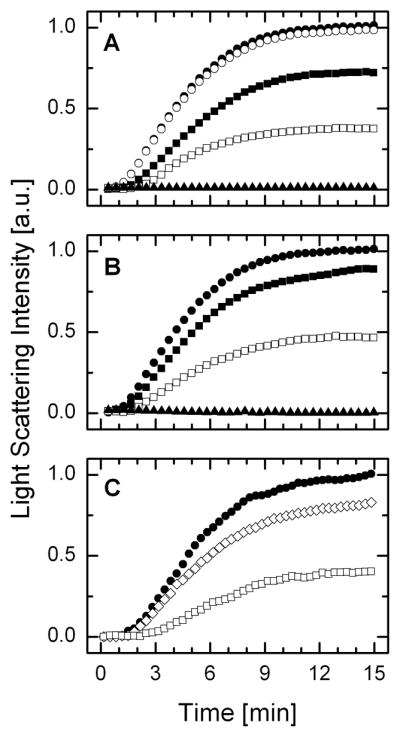

Yeast and human Prx I and Prx II have been shown to form homodecamer or higher oligomeric structures (15, 17). Jang et al (17) reported that the high molecular weight complexes exhibit molecular chaperone activity. These authors demonstrated that the peroxidase activity of yeast Prx I is correlated positively with the lowering of the size of its oligomer, with the dimeric form exhibiting the highest peroxidase activity. However, in the case of molecular chaperone activity, the opposite correlation was observed, in which the dimer fails to support the chaperone activity while the decameric Prx I or its higher molecular weight complexes generated under hyperoxidative conditions exhibit high chaperone activity. The chaperone activity of Prx isozymes might be important under oxidative stress or heat shock stress in protecting proteins from irreversible damage. Since at 50 μM of protein, glutathionylation of WT Prx I and its C52S/C173S mutant shifted Prx I structure from over 94% decamers to a population of low molecular weight oligomers, and in the case of C83S mutant, the observed 50% high molecular weight species was shifted to dimers and monomers, we assessed the effect of glutathionylation on the chaperone activity of Prx I. This was done by monitoring the thermally induced aggregation of a protein substrate, such as citrate synthase (CS), by light scattering measurement. Figure 4 shows the time courses, for the aggregation of 2 μM CS at 45°C in the presence of 10 μM deglutathionylated or glutathionylated Prx I. Figures 4A and 4B show that both the WT Prx I and its C52S/C173S mutant exhibit efficient chaperone activity. However, glutathionylation diminished their chaperone activity. In addition, the fact that the glutathionylated Prx I C52S/C173S mutant substantially inhibits its chaperone activity indicates that glutathionylation of Cys83 alone is sufficient to exert the functional effects of this covalent modification on Prx I. Interestingly, in the case of the C83S mutant, despite the fact that at 50 μM, 50% of the loaded C83S mutant was observed as decamers, at 10 μM C83S mutant fails to support chaperone activity (Fig. 4C). This observation could indicate that either the structure of the decameric C83S mutant fails to support its chaperone activity or at 10 μM the concentration is too low for forming a sufficiently high population of decamers due to a high dissociation constant for the decamers of this mutant, as indicated by the data shown in Fig. 2C. To differentiate these two possibilities, SV analysis was carried out with 10 μM C83S mutant and the results showed that at this concentration, there are no detectable decamers (see dash-dot-dashed line in Fig. 2C). Together, these results support the notion that while the Cys83-Cys83 disulfide bond is not essential for decamer formation, Cys83 indeed participates in stabilizing the decamer of Prx I.

Fig. 4. Glutathionylation induces a substantial reduction in chaperone activity of Prx I and its (C52/173S) mutant.

Chaperone activity of Prx I was monitored by its ability to protect citrate synthase (CS) from thermally induced aggregation. In these experiments, aggregation of 2 μM of CS at 45°C, pH 7.4, was monitored either alone or in the presence of 10 μM deglutathionylated or glutathionylated Prx I. (A) Effect of WT Prx I. Solid circle, 2 μM CS alone; open circle, 2 μM CS plus 10 mM GSSG; open square, 2 μM CS plus 10 μM WT Prx I; solid square, 2 μM CS plus 10 μM glutathionylated WT Prx I; solid triangle, 10 μM WT Prx I alone. (B) Effect of Prx I (C52S/C173S): Solid circle, 2 μM CS alone; open square, 2 μM CS plus 10 μM Prx I (C52S/C173S); solid square, 2 μM CS plus 10 μM glutathionylated Prx I (C52S/C173S); solid triangle, 10 μM Prx I (C52S/C173S) alone. (C) Effect of Prx I (C83S): Solid circle, 2 μM CS alone; open diamond, 2 μM CS plus 10 μM Prx I (C83S); open square, 2 μM CS plus 10 μM WT Prx I.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Our study reveals that glutathionylation of Prx I, an enzyme which possesses both peroxidase activity and molecular chaperone function, induces a structural change from decamer to a population of smaller oligomers, consisting mainly of dimers. This oligomeric structural change is accompanied by a loss of its molecular chaperone activity. Site directed mutagenesis study shows that among the three glutathionylation sites, Cys 52, 83 and 173, glutathionylation of Cys83 alone is sufficient to induce the dissociation of the Prx I decamer and inhibit its chaperone activity. Interestingly, comparative study on the glutathionylation of Prx I and Prx II in living cells induced by 10 to 50 μM of H2O2 revealed that Prx I, which contains Cys83, is preferentially glutathionylated. This observation suggests that glutathione may not be easily accessible to interact with the peroxidative Cys52 and the resolving Cys173 in the dimer, relative to Cys83. This notion is consistent with the finding that glutathione is a poor electron donor for the Prx I- and II-catalyzed peroxidation reactions (27). Together these results suggest that reversible glutathionylation of Cys83 regulates the oligomerization and chaperone activity of WT Prx I. Furthermore, it has been reported that in yeast Prx I, there is a correlation between the oligomeric structure of the enzyme and its dual functional activities, namely, the chaprone function is associated with the high molecular weight oligomers while the peroxidase is linked to the dimers (17). If this correlation between Prx I structure and the activity of this bifunctional enzyme also holds for mammalian Prx I, it implies that reversible glutathionylation can regulate the activity of a dual function enzyme.

It is intriguing that by incorporating a reversible glutathionylation regulatory mechanism, Prx I would gain a fine-tuned mechanism to regulate its dual functional activities in response to cell signaling and oxidative stress. Protein glutathionylation is a sensitive mechanism in responding to cell signaling including growth factor treatment (13, 14, 33) in the absence of any global increase in H2O2. The glutathionylation induced dissociation of the decameric Prx I to peroxidase active dimers would enhance its efficiency to remove the H2O2 locally generated during cell signaling process and allow a transient accumulation of H2O2 for cell signaling (34). On the other hand, when there is a global increase in H2O2, Prx I will be hyperoxidized to form higher order of aggregates due to oxidation of the peroxidative cysteine, Cys52, to its sulfinic or sulfonate derivative. The dissociation of the sulfinic derivative containing aggregates will require sulfiredoxin to catalyze its reduction, while the sulfonate containing aggregates are likely not dissociateable. In response to the emergency of global oxidative stress, the chaperone activity is needed to prevent global protein denaturation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NHLBI. This study was also supported in part by a Brain Korea 21 grant (to J.W.P.) and by BioR and D Program grants from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (to S.G.R.).

The abbreviations used are

Prx

peroxiredoxin

SV

sedimentation velocity

BioGEE

biotinylated glutathione ethyl ester

GSSG

oxidized glutathione

Trx

thioredoxin

TCL

total cell lysate

Footnotes

*

The authors wish to dedicate this work to the memory of Dr. Ann Ginsburg, a dedicated scientist and a devoted friend, who initiated the usage of ultracentrifugation methods to study protein conformation changes in the Laboratory of Biochemistry, NHLBI, more than four decades ago.

References

- 1.Hwang C, Sinskey AJ, Lodish HF. Oxidized redox state of glutathione in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 1992;257:1496–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1523409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert HF. Thiol/disulfide exchange equilibria and disulfide bond stability. Methods Enzymol. 1995;251:8–28. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)51107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sundaresan M, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Irani K, Finkel T. Requirement for generation of H2O2 for platelet-derived growth factor signal transduction. Science. 1995;270:296–299. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bae YS, Kang SW, Seo MS, Baines IC, Tekle E, Chock PB, Rhee SG. Epidermal growth factor (EGF)-induced generation of hydrogen peroxide. Role in EGF receptor-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett WC, DeGnore JP, Keng YF, Zhang ZY, Yim MB, Chock PB. Roles of superoxide radical anion in signal transduction mediated by reversible regulation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34543–34546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhee SG. Cell signaling. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science. 2006;312:1882–1883. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mieyal JJ, Gallogly MM, Qanungo S, Sabens EA, Shelton MD. Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications of reversible protein S-glutathionylation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1941–1988. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lillig CH, Berndt C, Holmgren A. Glutaredoxin systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:1304–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalle-Donne I, Rossi R, Colombo G, Giustarini D, Milzani A. Protein S-glutathionylation: a regulatory device from bacteria to humans. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanda M, Ihara Y, Murata H, Urata Y, Kono T, Yodoi J, Seto S, Yano K, Kondo T. Glutaredoxin modulates platelet-derived growth factor-dependent cell signaling by regulating the redox status of low molecular weight protein-tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28518–28528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604359200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adachi T, Pimentel DR, Heibeck T, Hou X, Lee YJ, Jiang B, Ido Y, Cohen RA. S-glutathiolation of Ras mediates redox-sensitive signaling by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29857–29862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen YR, Chen CL, Pfeiffer DR, Zweier JL. Mitochondrial complex II in the post-ischemic heart: oxidative injury and the role of protein S-glutathionylation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32640–32654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702294200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Boja ES, Tan W, Tekle E, Fales HM, English S, Mieyal JJ, Chock PB. Reversible glutathionylation regulates actin polymerization in A431 cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47763–47766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Tekle E, Oubrahim H, Mieyal JJ, Stadtman ER, Chock PB. Stable and controllable RNA interference: Investigating the physiological function of glutathionylated actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5103–5106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931345100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood ZA, Schroder E, Robin Harris J, Poole LB. Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang KS, Kang SW, Woo HA, Hwang SC, Chae HZ, Kim K, Rhee SG. Inactivation of human peroxiredoxin I during catalysis as the result of the oxidation of the catalytic site cysteine to cysteine-sulfinic acid. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38029–38036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang HH, Lee KO, Chi YH, Jung BG, Park SK, Park JH, Lee JR, Lee SS, Moon JC, Yun JW, Choi YO, Kim WY, Kang JS, Cheong GW, Yun DJ, Rhee SG, Cho MJ, Lee SY. Two enzymes in one; two yeast peroxiredoxins display oxidative stress-dependent switching from a peroxidase to a molecular chaperone function. Cell. 2004;117:625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang TS, Jeong W, Choi SY, Yu S, Kang SW, Rhee SG. Regulation of peroxiredoxin I activity by Cdc2-mediated phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25370–25376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qu D, Rashidian J, Mount MP, Aleyasin H, Parsanejad M, Lira A, Haque E, Zhang Y, Callaghan S, Daigle M, Rousseaux MW, Slack RS, Albert PR, Vincent I, Woulfe JM, Park DS. Role of Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of Prx2 in MPTP toxicity and Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2007;55:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jang HH, Kim SY, Park SK, Jeon HS, Lee YM, Jung JH, Lee SY, Chae HB, Jung YJ, Lee KO, Lim CO, Chung WS, Bahk JD, Yun DJ, Cho MJ. Phosphorylation and concomitant structural changes in human 2-Cys peroxiredoxin isotype I differentially regulate its peroxidase and molecular chaperone functions. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:351–355. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park JW, Mieyal JJ, Rhee SG, Chock PB. Deglutathionylation of 2-Cys peroxiredoxin is specifically catalyzed by sulfiredoxin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23364–23374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chae HZ, Kang SW, Rhee SG. Isoforms of mammalian peroxiredoxin that reduce peroxides in presence of thioredoxin. Methods Enzymol. 1999;300:219–226. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuck P. Analytical Ultrcentrifugation: Techniques and Methods. In: Scott DJ, Harding SE, Rowe AJ, editors. Analytical Ultrcentrifugation: Techniques and Methods. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge: 2005. pp. 26–50. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laue TM, Shah BD, Ridgeway TM, Pelletier SL. Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Sciences. In: Harding SE, Rowe AJ, Horton JC, editors. Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Sciences. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge: 1992. pp. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and lamm equation modeling. Biophys J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan DM, Wehr NB, Fergusson MM, Levine RL, Finkel T. Identification of oxidant-sensitive proteins: TNF-alpha induces protein glutathiolation. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11121–11128. doi: 10.1021/bi0007674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chae HZ, Kim HJ, Kang SW, Rhee SG. Characterization of three isoforms of mammalian peroxiredoxin that reduce peroxides in the presence of thioredoxin. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1999;45:101–112. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuck P. Diffusion of the reaction boundary of rapidly interacting macromolecules in sedimentation velocity. Biophys J. 2010;98:2741–2751. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee W, Choi KS, Riddell J, Ip C, Ghosh D, Park JH, Park YM. Human peroxiredoxin 1 and 2 are not duplicate proteins: the unique presence of CYS83 in Prx1 underscores the structural and functional differences between Prx1 and Prx2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22011–22022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610330200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumura T, Okamoto K, Iwahara S, Hori H, Takahashi Y, Nishino T, Abe Y. Dimer-oligomer interconversion of wild-type and mutant rat 2-Cys peroxiredoxin: disulfide formation at dimer-dimer interfaces is not essential for decamerization. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:284–293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhee SG, Chae HZ, Kim K. Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seo JH, Lim JC, Lee DY, Kim KS, Piszczek G, Nam HW, Kim YS, Ahn T, Yun CH, Kim K, Chock PB, Chae HZ. Novel protective mechanism against irreversible hyperoxidation of peroxiredoxin: Nalpha-terminal acetylation of human peroxiredoxin II. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13455–13465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900641200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hidalgo C, Sanchez G, Barrientos G, Aracena-Parks P. A transverse tubule NADPH oxidase activity stimulates calcium release from isolated triads via ryanodine receptor type 1 S-glutathionylation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26473–26482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woo HA, Yim SH, Shin DH, Kang D, Yu D-Y, Rhee SG. Inactivation of peroxiredoxin I by phosphorylation allows localized hydrogen peroxide accumulation for cell signaling. Cell. 2010;140:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]