The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials (original) (raw)

Abstract

To comprehend the results of a randomized controlled trial (RCT), readers must understand its design, conduct, analysis and interpretation. That goal can only be achieved through complete transparency from authors. Despite several decades of educational efforts, the reporting of RCTs needs improvement. Investigators and editors developed the original CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement to help authors improve reporting by using a checklist and flow diagram. The revised CONSORT statement presented in this paper incorporates new evidence and addresses some criticisms of the original statement.

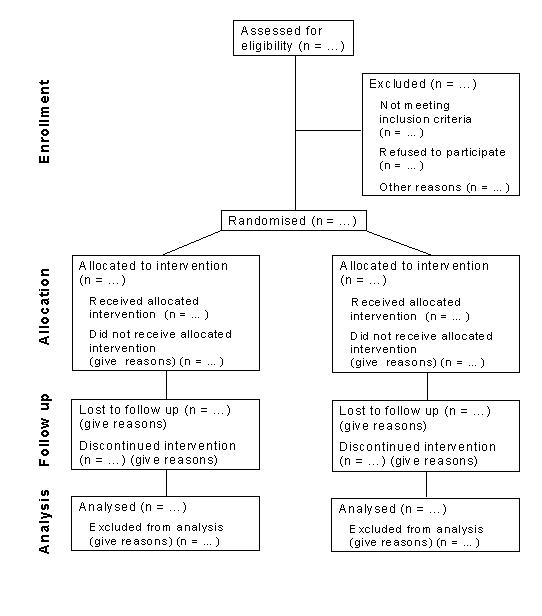

The checklist items pertain to the content of the Title, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion. The revised checklist includes 22-items selected because empirical evidence indicates that not reporting the information is associated with biasedestimates of treatment effect or the information is essential to judge the reliability or relevance of the findings. We intended the flow diagram to depict the passage of participants through an RCT. The revised flow diagram depicts information from four stages of a trial (enrolment, intervention allocation, follow-up, and analysis). The diagram explicitly includes the number of participants, for each intervention group, included in the primary data analysis. Inclusion of these numbers allows the reader to judge whether the authors have performed an intention-to-treat analysis.

In sum, the CONSORT statement is intended to improve the reporting of an RCT, enabling readers to understand a trial's conduct and to assess the validity of its results.

Contributors

Frank Davidoff, MD, Annals of Internal Medicine, (Philadelphia, PA); Susan Eastwood, ELS(D), University of California at San Francisco, (San Francisco, CA); Matthias Egger, MD, Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol, (Bristol, UK); Diana Elbourne, PhD, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, (London, UK); Peter Gøtzsche, MD, Nordic Cochrane Centre, (Copenhagen, Denmark); Sylvan B. Green, PhD, MD, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, (Cleveland, OH); Leni Grossman, BA, Merck & Co., Inc., (Whitehouse Station, NJ); Barbara S. Hawkins, MD, Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute, Johns Hopkins University, (Baltimore, MD); Richard Horton, MB, The Lancet, (London, UK); Wayne B. Jonas, MD, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, (Bethesda, MD); Terry Klassen, MD, Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta, (Edmonton, Alberta); Leah Lepage, PhD, Thomas C. Chalmers Centre for Systematic Reviews, (Ottawa, ON); Thomas Lang, MA, Tom Lang Communications, (Lakewood, OH); Jeroen Lijmer, MD, Dept. of Clinical Epidemiology, University of Amsterdam, (Amsterdam, The Netherlands); Rick Malone, BS, TAP Pharmaceuticals, (Lake Forest, IIL); Curtis L. Meinert, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, (Baltimore, MD); Mary Mosley, BS, Life Science Publishing, (Tokyo, Japan); Stuart Pocock, PhD, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, (London, UK); Drummond Rennie, JAMA, Chicago, IIL); David S. Riley, MD, University of New Mexico Medical School, (Santa Fe, NM); Roberta W. Scherer, MD, Epidemiology & Preventive Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, (Baltimore, MD); Ida Sim, MD, PhD, University of California at San Francisco, (San Francisco, CA); Donna Stroup, PhD, MSc, Epidemiology Program Office, Center for Disease Control & Prevention, (Atlanta, GA).

David Moher, Ken Schulz, and Doug Altman participated in regular conference calls, identified participants, contributed in the CONSORT meetings and drafted the manuscript. David Moher and Leah Lepage planned the CONSORT meetings, identified and secured funding, invited the participants and planned the meeting agenda. The members of the CONSORT group listed above attended the consort meetings and provided input in the revised checklist, flow diagram and/or text of this manuscript. David Moher is the Guarantor of the manuscript.

Introduction

A report of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) should convey to the reader, in a transparent manner, why the study was undertaken, and how it was conducted and analyzed. For example, a lack of adequately reported randomization has been associated with bias in estimating the effectiveness of interventions, [1,2]. To assess the strengths and limitations of an RCT, readers need and deserve to know the quality of its methodology.

Despite several decades of educational efforts, RCTs still are not being reported adequately, [3-6]. For example, a review, [5] of 122 recently published RCTs that evaluated the effectiveness of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) as first-line management strategy for depression found that only one (0.8%) paper described randomization adequately. Inadequate reporting makes the interpretation of RCTs difficult if not impossible. Moreover, inadequate reporting borders on unethical practice when biased results receive false credibility.

History of CONSORT

In the mid 1990s, two independent initiatives to improve the quality of reports of RCTs led to the publication of the CONSORT statement, [7] which was developed by an international group of clinical trialists, statisticians, epidemiologists and biomedical editors. CONSORT has been supported by a growing number of medical and health care journals, [8-11] and editorial groups, including the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, [12] (ICMJE, The Vancouver Group), the Council of Science Editors (CSE), and the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME). CONSORT is also published in Dutch, English, French, German, Japanese, and Spanish. It can be accessed together with other information about the CONSORT group on the Internet, [13].

The CONSORT statement comprises a checklist and flow diagram for reporting an RCT. For convenience, the checklist and diagram together are called simply CONSORT. They are primarily intended for use in writing, reviewing, or evaluating reports of simple two- group parallel RCTs.

Preliminary indications are that the use of CONSORT does indeed help to improve the quality of reports of RCTs, [14,15]. In an evaluation, [14] of 71 published RCTs, in three journals in 1994, allocation concealment was not clearly reported in 61% (n = 43) of the RCTs. Four years later, after these three journals required authors reporting an RCT to use CONSORT, the proportion of papers in which allocation concealment was not clearly reported had dropped to 39% (30 of 77, mean difference = -22%; 95% confidence interval of the difference: -38%, -6%).

The usefulness of CONSORT is enhanced by continuous monitoring of the biomedical literature that permits it to be modified depending on the merits of maintaining, or dropping current items and including new items. For example, when Meinert, [16] observed that the flow diagram did not provide important information about the number of participants who entered each phase of an RCT (i.e., enrollment, treatment allocation, follow-up, and data analysis), the diagram could be modified to accommodate the information. The checklist is similarly flexible.

This iterative process makes the CONSORT statement a continually evolving instrument. While participants in the CONSORT group and their degree of involvement vary over time, members meet regularly to review the need to refine CONSORT. At the 1999 meeting a decision was made to revise the original statement. This report reflects changes determined by consensus of the CONSORT group, partly in response to emerging evidence on the importance of various elements of RCTs.

Revision of the CONSORT statement

Thirteen members of the CONSORT group met in May 1999 with the primary objective of revising the original CONSORT checklist and flow diagram, as needed. The merits of including each item were discussed by the group in the light of current evidence. As in developing the original CONSORT statement, our intention was to keep only those items deemed fundamental to reporting standards for an RCT. Some items not considered essential may well be highly desirable and should still be included in an RCT report even though they are not included in CONSORT. Such items include institutional ethical review board approval, sources of funding for the trial, and a trial registry number (as, for example, the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) used to register the RCT at its inception [17].

Shortly after the meeting a revised version of the checklist was circulated to the group for additional comments and feedback. Revisions to the flow diagram similarly were made. All of these changes were discussed when CONSORT participants met in May 2000 and the revised statement finalized shortly afterwards.

The revised CONSORT statement includes a 22-item checklist (Table 1) and a flow diagram (Figure 1). Its primary aim is helping authors improve the quality of reports of simple two-group parallel RCTs. However, the basic philosophy underlying the development of the statement can be applied to any design. In this regard additional statements for other designs will be forthcoming from the group, [13]. CONSORT can also be used by peer reviewers and editors to identify reports with inadequate description of trials and those with potentially biased results, [1,2].

Table 1.

Checklist of items to include when reporting a randomized trial

| PAPER SECTION | Item | Descriptor | Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| And topic | # | on page # | |

| TITLE & ABSTRACT | 1 | How participants were allocated to interventions (e.g., random allocation", "randomized", or "randomly assigned"). | |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Background | 2 | Scientific background and explanation of rationale. | |

| METHODS | |||

| Participants | 3 | Eligibility criteria for participants and the settings and locations where the data were collected. | |

| Interventions | 4 | Precise details of the interventions intended for each group and how and when they were actually administered. | |

| Objectives | 5 | Specific objectives and hypotheses. | |

| Outcomes | 6 | Clearly defined primary and secondary outcome measures and, when applicable, | |

| any methods used to enhance the quality of measurements (e.g., multiple observations, training of assessors). | |||

| Sample size | 7 | How sample size was determined and, when applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping rules. | |

| Randomization: | |||

| Sequence generation | 8 | Method used to generate the random allocation sequence, including details of any restriction (e.g., blocking, stratification). | |

| Allocation concealment | 9 | Method used to implement the random allocation sequence (e.g., numbered | |

| containers or central telephone), clarifying whether the sequence was concealed until interventions were assigned. | |||

| Implementation | 10 | Who generated the allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to their groups. | |

| Blinding (Masking) | 11 | Whether or not participants, those administering the interventions, and those assessing the outcomes were blinded to group assignment. If done, how the success of blinding was evaluated. | |

| Statistical methods | 12 | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary outcome(s); Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses. | |

| RESULTS | |||

| Participant flow | 13 | Flow of participants through each stage (a diagram is strongly recommended). Specifically, for each group report the numbers of participants randomly assigned, receiving intended treatment, completing the study protocol, and analyzed for the primary outcome. Describe protocol deviations from study as planned, together with reasons. | |

| Recruitment | 14 | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up. | |

| Baseline data | 15 | Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of each group. | |

| Numbers analyzed | 16 | Number of participants (denominator) in each group included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by intention-to-treat". State the results in absolute numbers when feasible (e.g., 10/20, not 50%). | |

| Outcomes and Estimation | 17 | For each primary and secondary outcome, a summary of results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision (e.g., 95% confidence interval). | |

| Ancillary analyses | 18 | Address multiplicity by reporting any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, indicating those pre-specified and those exploratory. | |

| Adverse events | 19 | All important adverse events or side effects in each intervention group. | |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Interpretation | 20 | Interpretation of the results, taking into account study hypotheses, sources of potential bias or imprecision and the dangers associated with multiplicity of analyses and outcomes. | |

| Generalizability | 21 | Generalizability (external validity) of the trial findings. | |

| Overall evidence | 22 | General interpretation of the results in the context of current evidence. |

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of the progress through the phases of a randomized trial (i.e., enrollment, intervention allocation, follow-up, and data analysis)

During the 1999 meeting the group also discussed the benefits of developing an explanatory document to enhance the use and dissemination of CONSORT. The document is patterned on reporting of statistical aspects of clinical research, [18] which was developed to help facilitate the recommendations of the ICMJEs Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals. Three members of the CONSORT group (DGA, KFS, DM), with assistance from members on some checklist items, drafted an explanation and elaboration document. That document, [19] was circulated to the group for additions and revisions and was last revised after review at the latest CONSORT group meeting.

Changes to CONSORT

• In the revised checklist a new column for "paper section and topic" integrates information from the "subheading" column that was contained in the original statement.

• The "Was it reported?" column has been integrated into a "reported on page #" column, as requested by some journals.

• Each item of the checklist is now numbered and the syntax and order have been revised to improve the flow of information.

• The "Title" and "Abstract" are now combined in the first item.

• While the content of the revised checklist is similar to the original one some items that previously were combined are now separate. For example, previously authors were asked to describe "primary and secondary outcome(s) measure(s) and the minimum important difference(s), and indicate how the target sample size was projected". In the new version issues pertaining to outcomes (item 6) and sample size (item 7) are separate, enabling authors to be more explicit about each. Moreover, some items request additional information. For example, for outcomes (item 6) authors are asked to report any methods used to enhance the quality of measurements, such as multiple observations.

• The item asking for the unit of randomization (e.g., cluster) has been dropped because specific checklists have been developed for reporting cluster RCTs, [20] and other design types, [13] since publication of the original checklist.

• Whenever possible new evidence is incorporated into the revised checklist. For example, authors are asked to be explicit about whether the analysis reported is by intention-to-treat (item 16). This request is based in part on the observations, [21] that (a) authors do not adequately describe and apply intention-to-treat analysis and (b) reports that do not provide this information are less likely to report other relevant information, such as losses to follow-up, [22].

• The revised flow diagram depicts information from four stages of a trial (enrolment, intervention allocation, follow-up, and analysis). The revised diagram explicitly includes the number of participants, for each intervention group, included in the primary data analysis. Inclusion of these numbers lets the reader know whether the authors have performed an intention to treat analysis, [21-23]. Because some of the information may not always be known and to accommodate other information, the structure of the flow diagram may need to be modified for a particular trial. Inclusion of the participant flow diagram in the report is strongly recommended but may be unnecessary for simple trials, such as those without any participant withdrawals or dropouts.

Discussion

Specifically developed to provide guidance to authors about how to improve the quality of reporting of simple two-group parallel RCTs, CONSORT encourages transparency when reporting the methods and results so that reports of RCTs can be interpreted both readily and accurately. However, CONSORT does not address other facets of reporting that also require attention, such as scientific content and readability of RCT reports. Some authors in their enthusiasm to use CONSORT have modified the checklist, [24]. We recommend against such modifications because they may be based on a different process than the one used by the CONSORT group.

The use of CONSORT seems to reduce (if not eliminate) inadequate reporting of RCTs [14,15]. Potentially, the use of CONSORT should have a positive influence on how RCTs are conducted. Granting agencies have noted this potential relationship and in at least in one case, [25] have encouraged grantees to consider in their application how they have dealt with the CONSORT items.

The evidence-based approach used to develop CONSORT has also been used to develop standards for reporting meta-analyses of randomized trials, [26], meta-analyses of observational studies, [27] and diagnostic studies (personal communication - Jeroen Lijmer). Health economists have also started to develop reporting standards, [28] to help improve the quality of their reports, [29]. The intent of all of these initiatives is to improve the quality of reporting of biomedical research, [30] and by doing so to bring about more effective health care.

The revised CONSORT statement will replace the original one in those journals and groups that already support it. Journals that do not yet support CONSORT may do so by registering on the CONSORT Internet site, [13]. In order to convey to authors the importance of improved quality in the reporting of RCTs, we encourage supporting journals to reference the revised CONSORT statement and the CONSORT Internet address, [13] in their "Instructions to Contributors". As the journals publishing the revised CONSORT statement have waived copyright protection, CONSORT is now widely accessible to the biomedical community. The CONSORT checklist and flow diagram can also be accessed at the CONSORT Internet site, [13].

A lack of clarification of the meaning and rationale for each checklist item in the original CONSORT statement has been remedied with the development of the CONSORT explanation and elaboration document, [19] which can also be found on the CONSORT Internet site, [13]. This document includes reporting the evidence on which the checklist items are based, including the references, which annotated the checklist items in the previous version. We encourage journals to also include reference to this document also in their Instructions to Contributors.

Emphasizing the evolving nature of CONSORT, the CONSORT group invites readers to comment on the updated checklist and flow diagram through the CONSORT Internet site, [13]. Comments and suggestions will be collated and considered at the next meeting of the group in 2001.

Footnote

The revised CONSORT statement is also published in JAMA (Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, for the CONSORT group. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. JAMA 2001; 285:1987-1991), The Lancet (Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, for the CONSORT group. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials Lancet; 2001; 357:1191-1194), and Annals of Internal Medicine (Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, for the CONSORT group. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. Annals of Internal Medicine; 2001; 134:657-662). Authors can use any one of these references, as well as the reference in BMC Medical Research Methodology, when citing CONSORT.

Correspondence

Correspondence should be addressed to: Leah Lepage, Thomas C Chalmers Center for Systematic Reviews, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario research Institute, Room R235; 401 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Ontario, KIH 8LI, Canada. Email: llepage@ottawa.ca

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The effort to improve the reporting of randomized trials, from its beginnings with the Standards of Reporting Trials (SORT) group to the current activities of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) group, have involved a large number of people around the globe. We wish to thank Leah Lepage for keeping everybody all lined up and moving in the same direction.

Financial support to convene meetings of the CONSORT group was provided in part by Abbott Laboratories, American College of Physicians, GlaxoWellcome, The Lancet, Merck, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, National Library of Medicine, and TAP Pharmaceuticals.

Contributor Information

David Moher, Email: dmoher@uottawa.ca.

Kenneth F Schulz, Email: kschulz@fhi.org.

Douglas G Altman, Email: d.altman@icrf.icnet.uk.

References

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;273:408–412. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, Tugwell P. Does the quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet. 1998;352:609–613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad AR, Boyle M, Cunningham C, Kim M, Schachar R. Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No11 (Prepared by McMaster University under Contract No 290-97-0017), 2000.

- Thornley B, Adams CE. Content and quality of 2000 controlled trials in schizophrenia over 50 years. BMJ. 1998;317:1181–1184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotopf M, Lewis G, Normand C. Putting trials on trial- the costs and consequences of small trials in depression: a systematic review of methodology. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51:354–358. doi: 10.1136/jech.51.4.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson K, Bunn F, Wentz R, Edwards P, Roberts I. Size and quality of randomised controlled trials in head injury: review of published studies. BMJ. 2000;320:1308–1311. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7245.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB, Cho MK, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, Rennie D, Schulz KF, Simel DL, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276:637–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freemantle N, Mason JM, Haines A, Eccles MP. CONSORT: an important step toward evidence-based health care. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:81–83. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-1-199701010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG. Better reporting of randomized controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 1996;313:570–571. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7057.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF. The quest for unbiased research: randomized clinical trials and the CONSORT reporting guidelines. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:569–573. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston P, Hoey J. CMAJ endorses the CONSORT statement. CMAJ. 1996;155:1277–1279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff F. News from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:229–231. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-3-200008010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2000. http://www.consort-statement.org

- Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L, for the CONSORT Group Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: a comparative before and after evaluation? JAMA. 2001;285:1992–1995. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Jüni P, Bartlett C, for the CONSORT Group The value of patient flow charts in reports of randomized controlled trials: bibliographic study. JAMA. 2001;285:1996–1999. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinert CL. Beyond CONSORT: Need for improved reporting standards for clinical trials. JAMA. 1998;279:1487–1489. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.18.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers I. Current Controlled Trials: an opportunity to help improve the quality of clinical research. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2000;1:3–8. doi: 10.1186/CVM-1-1-003. http://cvm.controlled-trials.com/content/1/1/3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailer JC, III, Mosteller F. Guidelines for statistical reporting in articles for medical journals: amplifications and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:266–273. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-2-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gøtzsche PC, Lang T, for the CONSORT group The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:663–694. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbourne DR, Campbell MK. Extending the CONSORT statement to cluster randomised trials: for discussion. Stats Med. 2001;20:489–496. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20010215)20:3<489::AID-SIM806>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention-to-treat analysis? Survey of published randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 1999;319:670–674. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Canela M, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, de Irala-Estevez J. Intention-to-treat analysis is related to methodological quality. BMJ. 2000;320:1007. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7240.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Ellenberg JH, Hirtz DG, Nelson KB. Analysis of clinical trials by treatment actually is it really an option? Stat Med. 1991;10:1595–1605. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780101011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen SM. Towards evidence based radiation oncology: improving the design, analysis, and reporting of clinical outcome studies in radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 1998;46:5–18. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(97)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole LB. MRC uses checklist similar to CONSORTs. BMJ. 1997;314:1127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF, for the QUOROM group Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–1900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JE, Weinstein MC, Russell LB, Gold MR. Recommendations for reporting cost-effectiveness analysis. JAMA. 1996;276:1339–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.16.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann PJ, Stone PW, Chapman RH, Sandberg EA, Bell CM. The Quality of Reporting in Published Cost-Utility Analyses, 1976-1997. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:964–972. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-12-200006200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG. The scandal of poor medical research. BMJ. 1994;308:283–284. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6924.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]