Rorα is essential for nuocyte development (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2012 Sep 1.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Immunol. 2012 Jan 22;13(3):229–236. doi: 10.1038/ni.2208

Abstract

Nuocytes are essential in innate type-2 immunity and contribute to the exacerbation of asthma responses. Here we show that nuocytes arise in the bone marrow and differentiate from common lymphoid progenitors, which makes them distinct new members of the lymphoid lineage. Nuocytes required interleukin 7 (IL-7), IL-33 and Notch signalling for development in vitro. Double negative 1 (DN1) and DN2 pro-T-cell progenitors maintained nuocyte potential in vitro, although the thymus was not essential for nuocyte development. Notably, the transcription factor Rorα was critical for nuocyte development and their role in parasitic worm expulsion.

Nuocytes are innate type-2 cytokine-secreting cells that play critical roles in immune responses to parasitic worm infection1. These cells display a number of characteristics that suggest they may share a developmental lineage with natural helper cells (NHC) 2 and innate helper cells (IHC) 3,4. For example, nuocytes express the lymphoid growth factor receptor IL-7Rα, and NHC and IHC both require γc signalling for development. Attempts to differentiate nuocytes into other lymphoid or myeloid cells were unsuccessful 1, and similar to NHCs, nuocytes could not be induced to become T cells upon culture on stromal cells expressing Delta-like ligands (OP9-DL1)2.

Nuocytes represent a rare cell population in naïve mice, but their numbers increase dramatically in response to either IL-25, IL-33, helminth infection 1,5 and in asthma models 6,7, where these cells constitute a major early source of the type-2 immune cytokines IL-5 and IL-13. In addition to their roles in protective immunity against helminths, these cytokines initiate many of the responses characteristic of allergic asthma 8,9. Type-2 innate lymphoid cells have also been characterized in humans, with increased numbers in samples from individuals with chronic rhinosinusitis 10. Thus, nuocytes represent an important cell in type-2-mediated diseases such as asthma and allergy. Although nuocytes share a number of characteristics with lymphoid cells they do not express lineage markers (i.e. lineage negative, Lin−), their development is not impaired in B and T cell deficient _Rag2_−/− mice 1 and their origin is currently unknown. However, they do share phenotypic and functional similarities with TH2 cells, expressing ICOS, IL-17BR and T1/ST2 receptors and responding to IL-25 and IL-33 by secreting high levels of IL-5 and IL-13 1,11-13.

The innate lymphoid cell (ILC) family has grown recently, expanding from the prototypic members, natural killer (NK) cells and lymphoid-tissue inducer (LTi) cells, to encompass the closely related ILC22 and ILC17 cells 14-18. Notably, LTi, ILC17 and ILC22 are all dependent on the expression of the transcription factor retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor γ (Rorγt, encoded by Rorc) 14,19,20. However, Rorγt is not required for nuocyte or NHC development 1,2.

Although each immune cell type is phenotypically and functionally distinct from one another, they are all derived from a common ancestral hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) 21,22. Downstream of HSCs the developing progenitors display increasing lineage restriction. Common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) are Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3+ cells committed toward T cell, B cell, NK cell and plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC) lymphoid lineages. By contrast common myeloid progenitors (Lin−IL-7Rα−Sca1−c-kit+) give rise to granulocytes, macrophages and erythroid lineages. IL-7 signalling through IL-7 receptor α (IL-7Rα) is crucial for lymphopoiesis in vivo 23, but not NK cell development 24, and IL-7Rα is a principal molecular marker of lymphoid progenitors, but not myeloid lineages 25. Here we have examined the lineage specificity of nuocytes and the signals that induce their development. We report that nuocytes develop from CLPs, requiring IL-33, IL-7 and Notch signalling. We also demonstrate that the transcription factor Rorα (encoded by Rora) is critical for nuocyte development and their role in parasitic worm clearance.

RESULTS

Nuocytes in the bone marrow are distinct from CLPs

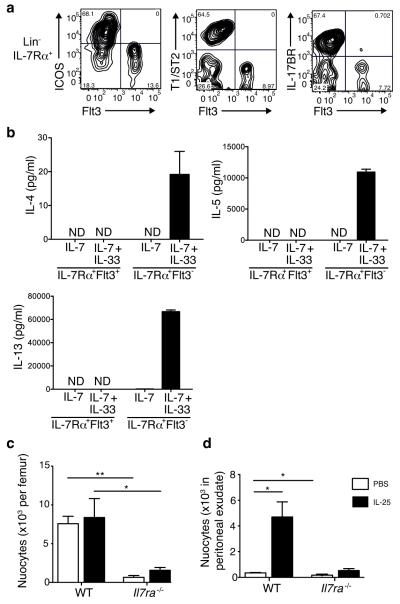

The presence of the leukocyte common antigen CD45 on nuocytes suggested they may have a hematopoietic origin 1. Apart from T cells, all leukocytes develop in the fetal liver or bone marrow and are released into the circulation either as mature or immature cells. Since a number of the markers found on nuocytes, for example c-kit and Sca1, mirror those on hematopoietic progenitor cells, we determined whether nuocytes were distinct from these progenitors. We used multicolour flow cytometry to determine the expression of various nuocyte (IL-17BR, ICOS or T1/ST2 1), and CLP (Flt3) 26, surface markers in the bone marrow (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a). All three nuocyte markers were restricted to the Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3− non-CLP population (Fig. 1a) and this nuocyte subset represented >60% of cells within the Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3− population.

Figure 1.

Nuocytes are distinct from CLPs. (a) Flow cytometry profiles for nuocyte (Lin−ICOS+T1/ST2+ Flt3−) and CLP (Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3+) in naïve Lin−IL-7Rα+ cells. Representative of three repeat experiments. (b) ELISA for IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 in supernatants from purified Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3− and Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3+ cells cultured at 1 × 105/ml for 72 hrs. Representative of two experiments with duplicate wells in each. (c, d) Nuocyte numbers from bone marrow (c) and peritoneum (d) in wild-type (WT) and _Il7ra_−/− mice treated with PBS or IL-25 intraperitoneally. * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01. Representative data from two independent experiments with 4 to 5 mice per group.

Another hallmark of nuocytes is secretion of IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-33. To confirm that the Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3− population was enriched with functional nuocytes, we purified both Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3+ (CLPs) and Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3− cells from the bone marrow of naïve mice and cultured them in the presence of IL-7 with or without IL-33. Only the Lin-IL-7Rα+Flt3− cells produced IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-7 and IL-33 (Fig. 1b). Thus, nuocytes are present in bone marrow (~ 0.015% of total non-red blood cells) and are distinct from CLPs.

Nuocyte development requires IL-7 signalling

The IL-7 signalling pathway is critical for early T and B cell development in vivo 24, and fate mapping using Il7r reporter mice has revealed that all T cells, but very few myeloid cells, are derived from an IL-7R+ lymphoid progenitor 25. We tested the functional importance of IL-7 signalling on nuocyte development in vivo using _Il7r_α−/− mice. _Il7ra_−/− mice had significantly fewer nuocytes (CD4−CD19−ICOS+IL-17BR+) in the bone marrow compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, IL-25 administration did not increase the number of nuocytes in the peritoneal cavity of _Il7ra_−/− mice compared to similarly treated wild-type controls (Fig. 1d). Thus, as with other lymphoid lineages, IL-7 signalling is required for nuocyte development.

Nuocyte development requires Notch signalling in vitro

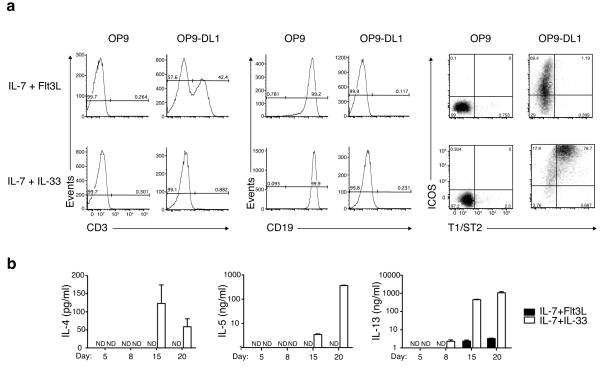

The OP9 stromal cell line supports early hematopoiesis 27 and, when expressing the Notch ligand Delta-like-1 (OP9-DL1), T cell development 28. We co-cultured purified bone marrow-derived CLPs with OP9 or OP9-DL1 in the presence of factors that either promote T cell (IL-7 and Flt3L) or nuocyte development (IL-7 and IL-33). As expected, CLPs cultured in the absence of Notch ligands in the presence of IL-7 and Flt3L developed into B cells (Fig. 2a), while CLPs grown on OP9-DL1 with IL-7 and Flt3L differentiated into T cells over a 20 – 26 day period (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a), by progressing through CD44+CD25+ and CD44loCD25− stages and expressing TCRαβ (Supplementary Fig. 2b,c). CLPs cultured on OP9-DL1 plus IL-7 and IL-33 did not give rise to T cells up to day 20 (at IL-7 concentrations >2.5 ng/ml) (Supplementary Fig. 3), and the majority of cells maintained expression of CD44 and CD25, and up-regulated ICOS (Supplementary Fig. 2c). These cells also upregulated the nuocyte markers ICOS and T1/ST2, and were lineage negative (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a), with more than 70% of the surviving cells expressing both ICOS and T1/ST2 by day 20. Notably, CLPs failed to differentiate into nuocytes on OP9 stromal cells even in the presence of IL-7 and IL-33, and instead developed into B cells (Fig. 2a). Transferring cells between OP9-DL1 and OP9 cultures suggested that developing nuocytes required a Notch signal to be present for the first 3 – 6 days of culture, after which time they were committed to nuocyte development (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, Notch signalling, which is critical for T cell development, is also essential for nuocyte differentiation from CLPs in vitro. Efforts to establish a role for Notch signalling in vivo have proved inconclusive (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Figure 2.

Notch signalling is essential for the in vitro generation of nuocytes from CLPs. (a) Flow cytometry profiles of CLPs cultured on OP9 or OP9-DL1 stromal cells and analysed for the expression of T (CD3+), B (CD19+) and nuocyte (ICOS+T1/ST2+) markers on day 20. (b) ELISA of culture supernatants collected from the above OP9-DL1 cultures on the days indicated. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Analysis of type-2 cytokine secretion in supernatants from the OP9-DL1 cultures demonstrated that CLPs cultured with IL-7 and IL-33 expressed elevated levels of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 compared to CLPs cultured in IL-7 and Flt3L (Fig. 2b). Intracellular cytokine staining confirmed that T1/ST2+ICOS+ cells produced both IL-13 and IL-5 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Thus, Notch signalling is critical for nuocyte development.

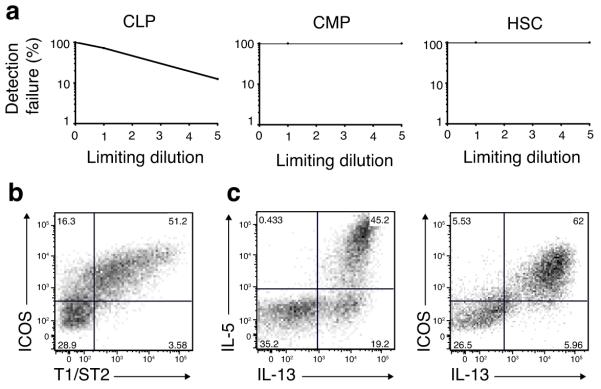

Clonal expansion of nuocytes from CLPs

We sought to determine the clonal frequency of CLPs with nuocyte progenitor potential in comparison to CMPs and HSCs. CLPs, CMPs or HSCs were sorted as 1 or 5 cells per well in wells containing OP9-DL1, IL-7 and IL-33. After 18 days of culture ~25% of the single cell sorted CLPs (21 out of 84 single clones) had expanded in the presence of IL-7 and IL-33 (Fig. 3a). No clonal expansion was detected from single or 5 cell cultures of CMPs or HSCs (i.e. 0 out of 60 wells each) (Fig. 3a). The CLP-derived clones were negative for the T, B and NK cell markers CD4, CD8, CD3, CD19 and NKp46 (data not shown), but expressed the nuocyte markers ICOS and T1/ST2 (Fig. 3b). Intracellular cytokine staining of the CLP-derived cells confirmed that they were dual IL-5 and IL-13-producing nuocytes (Fig. 3c). Therefore, nuocytes can be clonally expanded in vitro from CLPs, but cannot be derived directly from HSCs under Notch, IL-7 and IL-33 signalling conditions.

Figure 3.

Progenitor frequencies support nuocyte lymphoid origin. (a) Clonal expansion from single or 5 CLPs, CMPs or HSCs (means of 60 - 84 wells of each) sorted onto OP9-DL1 stromal cells and cultured in the presence of IL-7 and IL-33 for 18 days. (b) Flow cytometry analysis of ICOS and T1/ST2, and (c) intracellular cytokine expression by a representative CLP-derived clone at day 18.

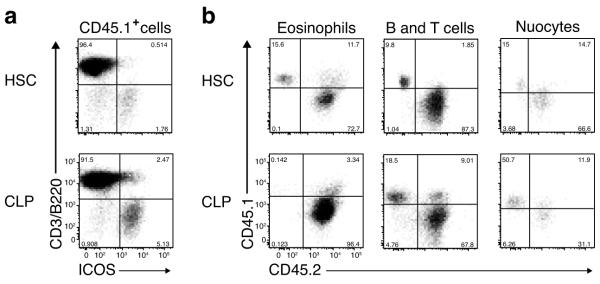

In vivo CLP reconstitution gives rise to nuocytes

To determine the cell fate choices of CLPs under more physiological conditions, we tested if CLPs could give rise to nuocytes in vivo in adoptive transfer experiments. Purified Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3+ CLPs 26 (Supplementary Fig. 1b), Lin−IL-7Rα−Sca-1+cKit+ HSCs or Lin−IL-7Rα−Sca-1−cKit+ CMPs (Supplementary Fig. 1c) from CD45.1 B6/SJL mice were each mixed with CD45.2 C57BL/6 total bone marrow cells and adoptively transferred into lethally irradiated CD45.2 C57BL/6 mice.

Three weeks after cell transfer, HSCs had reconstituted the recipient mice giving rise to B, T and CD11b+ myeloid cells in the blood (Supplementary Fig. 6a), whereas CLPs gave rise mostly (>97%) to cells of the lymphoid lineage: B and T cells (Supplementary Fig. 6b). No granulocytes were detected from the donor CLPs (data not shown). Although CMPs readily differentiated into myeloid cells in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 7) they failed to give rise to any myeloid cells in vivo at the time point analysed (data not shown). Furthermore, we were unable to detect successful CMP reconstitution even when analysis was performed between 2 and 4 weeks post implantation (data not shown). The failure of donor CMPs to reconstitute the recipient mice was most likely due to the poor self-renewing capacity of CMP in vivo 29.

Six weeks after the initial cell transfers, the recipient mice were administered IL-25 for four days to induce nuocyte expansion and analysed for the presence of CD45.1+ donor derived nuocytes in the mesenteric lymph nodes of mice that were reconstituted with HSCs or CLPs. Donor-derived CD45.1+ nuocytes were present in mice that received HSCs confirming their hematopoietic origin (Fig. 4a). More importantly, nuocytes were also detected in CLP-transplanted animals, confirming the lymphoid heritage of nuocytes in vivo (Fig. 4a). No donor-derived nuocytes were observed in the CMP-transplanted mice treated with IL-25 (data not shown). CD45.1+ nuocytes were also present in the peritoneal lavage of HSC and CLP-transplanted mice. To confirm the efficiency of the adoptive transfer we looked at other cell lineages in the peritoneum. Donor HSCs reconstituted both myeloid and lymphoid lineages, since CD45.1+ donor-derived eosinophils, B and T cells as well as nuocytes were found in the peritoneum (Fig. 4b). By contrast, donor CLPs only gave rise to lymphoid cells, such as B and T cells and nuocytes (Fig. 4b), but not to CD45.1+ eosinophils in the peritoneum of CLP recipient mice (Fig. 4b). Thus, CLPs represent the in vivo precursor of nuocytes.

Figure 4.

Adoptive transfer of CLPs gives rise to nuocytes. (a) Flow cytometric detection of nuocytes (B220−CD3−ICOS+) from donor HSCs or CLPs (CD45.1) in mesenteric lymph node following IL-25 treated mice ~6 weeks after reconstitution. (b) Flow cytometry of peritoneal cells for the presence of donor HSCs or CLPs CD45.1 cells within the eosinophil (SSChiSiglecF+), B/T cells (B220+/CD3+) and nuocyte (Lin−ICOS+) populations. Data are representative of three independent experiments with 5 to 6 mice per group.

DN1 and DN2 thymocytes retain nuocyte potential

Notch signalling plays an essential role in the development of T cells, by restricting the myeloid and B cell potential of developing T cells 30,31. Differentiation of progenitor cells into mature T cells involves several cellular stages that are defined by cell surface expression of markers including CD44 and CD25 on CD4−CD8− double negative (DN) early T cell subsets, with DN1, DN2, DN3 and DN4 cells becoming more T cell restricted as they progress from DN1 to DN4 31.

We sought to determine whether T cell progenitors in the thymus might also retain the plasticity to become nuocytes. We purified Lin−DN1 (CD44+CD25−), Lin−DN2 (CD44+CD25+) and Lin−DN3 (CD44−CD25+) thymic subsets and co-cultured them as either single or 100 cells on OP9 or OP9-DL1 monolayers in the presence of IL-7 and IL-33. Culture on OP9-DL1 plus IL-7 and IL-33 resulted in cell expansion in ~10% of cases for single sorted DN1 cells and 100% for 100 DN1 sorted cells (Fig. 5a). DN2 cell cultures expanded in ~50% of the 100 cell colonies, but failed to expand from the single cell colonies (Fig. 5a), while DN3 cells expanded in ~20% of the single cell colonies and ~50% of the 100 cell colonies (Fig. 5a).

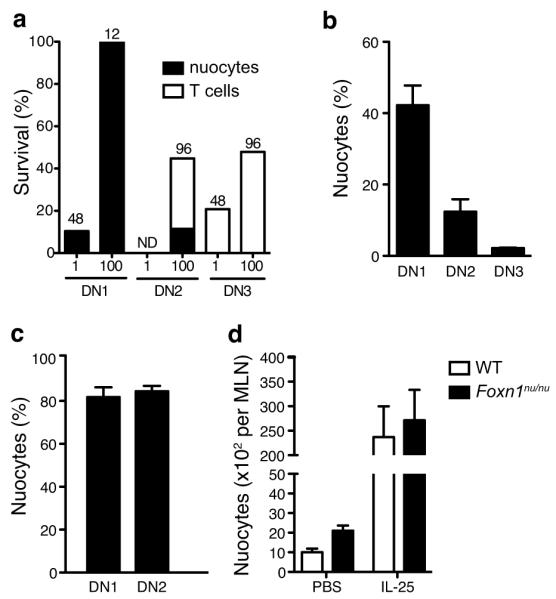

Figure 5.

DN1 and DN2 thymocytes retain the plasticity to differentiate into nuocytes. Thymocyte subsets were cultured on OP9-DL1 stromal cells at 1 or 100 cells per well in the presence of IL-7 and IL-33. (a) Clonal survival after 2 to 5 weeks. The numbers above the bars indicate the numbers of starting wells. ND, not detected. (b,c) Flow cytometry detection of nuocytes (Lin−ICOS+T1/ST2+) in IL-7 + IL-33 cultures after 24 days (b) and 38 days (c). (d) Flow cytometry analysis of nuocytes (Lin−ICOS+T1/ST2+) in nude mice following IL-25 administration for 3 days.

Analysis of the cell surface expression of ICOS and T1/ST2 showed that all DN1-starting colonies and 11-100% of DN2 clones (depending on the experiment), but not the DN3 clones, developed a Lin−T1/ST2+ICOS+ phenotype similar to nuocytes (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 8a). The variation in the proportion of DN2 clones developing into nuocytes was likely due to contamination with DN3 cells, because a more restricted gating to avoid DN3 cells resulted in 100% of the DN2 clones developing into nuocytes (data not shown). In DN1 and DN2 derived populations, nuocytes represented ~96% of cells and expressed IL-13 as measured by intracellular cytokine staining (Supplementary Fig. 8b). The small numbers of remaining cells were found to be NK cells or T cells (a proportion of which were IL-13+) (data not shown). DN3 cells all developed into T cells when cultured on OP9-DL1 monolayers in the presence of IL-7 and IL-33 indicating that cells at the DN3 stage have extinguished their nuocyte potential (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 8c). OP9 monolayers lacking Notch ligand provided extremely poor support for cell survival or growth from the DN cell stages cultured with IL-7 and IL-33 (data not shown). Thus, thymocytes at the DN1 and DN2 stages of development retain the capacity to develop into nuocytes.

However, these experiments did not address whether the same cell retained the potential to give rise to both T cells and nuocytes. To address this we sorted single DN1, DN2 or DN3 cells into individual wells containing OP9-DL1 monolayers in the presence of only IL-7 and expanded the clones for 10 – 12 days to generate sufficient cells for subsequent analysis. Surviving clones were then divided onto wells containing OP9-DL1 cells and either IL-7 alone, IL-7 plus IL-33 or IL-7 plus Flt3L. Even in the absence of Flt3L, IL-7 induced T cell development from DN1 and DN2 starting cells in a high proportion (70 – 85%), similar to IL-7 plus Flt3L cultures (data not shown). However, the addition of IL-33, even after prolonged IL-7 culture, resulted in nuocyte development from all surviving cultures (up to 80% by day 38) indicating that individual cells within the DN1 and DN2 population retain the plasticity to give rise to T cells or nuocyte progeny (Fig. 5b,c). By contrast, DN3 clones gave rise to T cells even in the presence of IL-33 (Fig. 5b).

In spite of the fact that DN1 and DN2 precursors retained nuocyte development potential, Foxn1nu/nu (nude) mice, which are athymic due to developmental failure of the thymic epithelium, showed normal nuocyte development (Fig. 5d). This indicates that signals for nuocyte development are available at extrathymic sites. Notch ligands are expressed by bone marrow stromal cells 30 and, using _il33_-citrine knock-in reporter mice, we detected IL-33 expression, in naïve CD45+ bone marrow cells (Supplementary Fig. 9), suggesting that bone marrow may represent an important niche for nuocyte development. Therefore, although DN1 and DN2 cells maintain nuocyte development capacity, the ability of nuocytes to develop independently of the thymus suggests that thymocytes do not represent the critical source of nuocytes.

Rorα is essential for efficient nuocyte development

To further characterise the developmental requirements of nuocytes, we used quantitative PCR to validate the expression of a subset of transcription factors and signalling molecules previously identified in a gene expression profiling in nuocytes 1. Amongst these genes, Notch1 was highly expressed, as were Notch2, Id2, Tcf7, and Bcl11b (Fig. 6a). Notably, although Rorγ expression was relatively low, Rorα expression was more abundant (Fig. 6a). Rorα is a member of the retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor family that includes Rorγ, but which plays only a minor role in Th17 development 32. Given the reported role of Rorγ in LTi and ILC development, we investigated whether Rorα plays a role in nuocyte development. We used Staggerer (_Rora_sg/sg) mice that carry a spontaneous deletion within the Rora gene that prevents translation of the ligand-binding homology domain and gives rise to a phenotype similar to Rorα deficiency33.

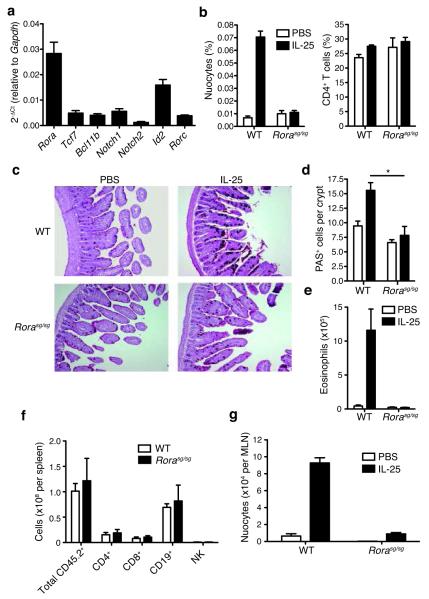

Figure 6.

Rorα is required for nuocyte development. (a) qPCR analysis of gene expression in ex vivo nuocytes. (b) Flow cytometric analysis of nuocytes and CD4+ T cells in _Rora_sg/sg and wildtype mice in mesenteric lymph node (MLN) after 4 daily doses of IL-25, or PBS. Combined data from two repeat experiments with 3 - 6 mice per group. (c) PAS stained histology sections of intestine following IL-25 treatment. (d) Enumeration of PAS+ (goblet) cells in intestine. (e) Flow cytometry analysis of eosinophils in peritoneal lavage after IL-25 treatment. (f) Flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes following IL-25 treatment ~six weeks after total bone marrow reconstitution. (g) Flow cytometry analysis of nuocyte (Lin−ICOS+T1/ST2+) development from _Rora_sg/sg bone marrow transfer. * = p < 0.05. Data are representative of two independent experiments with 2 - 4 mice per group.

IL-25 injection to expand nuocytes in vivo failed to induce nuocytes in _Rora_sg/sg mice when compared to nuocyte expansion in control wild-type littermates (Fig. 6b). The proportion of CD4+ T cells was not altered by the absence of Rorα (Fig. 6b). Nuocytes are critical for intestinal goblet cell hyperplasia and eosinophilia following IL-25 treatment 1. Histological examination demonstrated that _Rora_sg/sg mice failed to develop goblet cell hyperplasia (Fig. 6c,d) or eosinophilia (Fig. 6e) in response to IL-25, as compared to littermate controls.

_Rora_sg/sg mice have profound neurobiological defects that result in a failure to thrive and small size, although _Rora_sg/sg mice have no intrinsic defects in T and B cell development34. Therefore, we generated bone marrow chimeras by transferring CD45.2 _Rora_sg/sg or wild-type littermate bone marrow into CD45.1 irradiated recipients to circumvent the potential confounding effects of the neural abnormalities. Six – eight weeks after bone marrow transfer, reconstituted mice were administered IL-25 to induce nuocyte expansion. Despite equivalent hematological repopulation (Fig. 6f), animals receiving _Rora_sg/sg bone marrow had a major deficit in IL-25-driven nuocyte production as compared to recipients receiving wild-type bone marrow (Fig. 6g). Thus, the presence of Rorα is critical for normal nuocyte development.

Intrinsic Rorα expression is required for nuocyte development

To determine whether Rorα acts in a nuocyte intrinsic manner we purified CLPs from _Rora_sg/sg or wild-type littermate control bone marrow and assessed their ability to develop into nuocytes when plated onto OP9-DL1 stromal cells in the presence of IL-7 and IL-33, or IL-7 plus Flt3L. Both _Rora_sg/sg and wild-type CLPs gave rise to T cells (Fig. 7a). However, in contrast to the wild-type CLPs, _Rora_sg/sg CLPs failed to develop into nuocytes (Fig. 7a) following culture with IL-7 and IL-33, though a small proportion of nuocytes was detected in _Rora_sg/sg CLP cultures by day 28 (Supplementary Fig. 10).

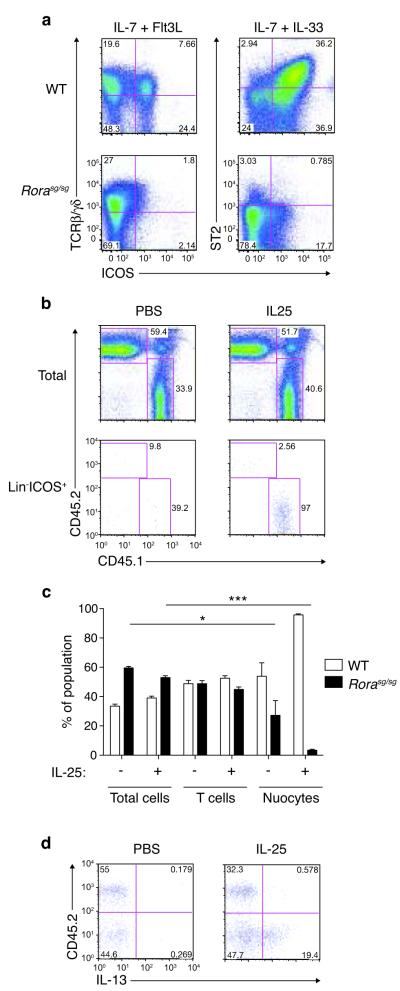

Figure 7.

Intrinsic Rorα is required for nuocyte development. (a) Flow cytometry analysis of T cells and nuocytes derived from _Rora_sg/sg or wildtype CLPs cultured in vitro for 16 days. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (b) Flow cytometry analysis of total cells (upper panel) and nuocytes (lower panel) in the CD45.1 and CD45.2 cell compartments of MLN following IL-25 treatment ~six weeks after mixed chimera bone marrow transfers. (c) Flow cytometry analysis of the CD45.1 and CD45.2 reconstituting cells following PBS or IL-25 treatment. (d) Intracellular IL-13 expression in the Lin−CD45.1 and Lin−CD45.2 cell compartments following PBS or IL-25 treatment ~six weeks after mixed chimera bone marrow transfers. * = p < 0.05; *** = p < 0.0001. Data are representative of two independent experiments with 3 - 5 mice per group.

To confirm the intrinsic role of Rorα for nuocyte development in vivo we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras. CD45.1 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with a one-to-one mixture of CD45.2 _Rora_sg/sg and CD45.1 wild-type total bone marrow. Six – eight weeks after bone marrow transfer, we administered intra-peritoneal IL-25 and looked for nuocytes. Despite equivalent hematological repopulation (Fig. 7b,c), _Rora_sg/sg bone marrow did not give rise to nuocytes, while control wild-type bone marrow did (Fig. 7b,c). These results were confirmed by intracellular IL-13 staining (Fig. 7d). T cell development was not altered appreciably by the absence of Rorα (Fig. 7c). Therefore, the role for Rorα in nuocyte development is cell autonomous.

_Ror_αsg/sg mice have impaired immunity to parasitic helminths

Adoptive transfer of nuocytes into recipients that are normally unable to expel the parasitic helminth Nippostrongylus brasiliensis results in rapid expulsion of worms from the intestine 1. Since _Rora_sg/sg mice have deficient numbers of nuocytes, we investigated their ability to expel parasitic worms. _Rora_sg/sg mice and wild-type littermates were infected with N. brasiliensis and worm burdens were assessed after 6 days. Analysis at longer time-points was hindered by the ill-health of the _Rora_sg/sg mice. However, even at the 6-day time point, Rorα–deficiency severely impaired worm clearance, as compared to wild-types (Fig. 8a). Nuocyte expansion was not induced in _Rora_sg/sg mice by the presence of the parasite (Fig. 8b).

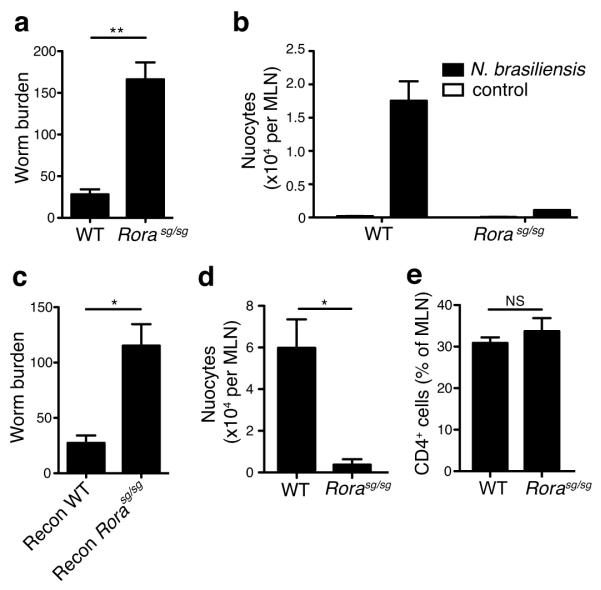

Figure 8.

_Rora_sg/sg mice fail to expel N. brasiliensis efficiently. (a) Worm burdens at day 6 post-infection. Data are combined from two independent experiments. WT n = 11, _Rora_sg/sg n = 4. (b) Flow cytometry analysis of nuocytes (Lin−ICOS+T1/ST2+) in MLN at day 6 post-infection. (c) Worm burdens at day 5 post-infection in irradiated WT recipients reconstituted with either WT or _Rora_sg/sg total bone marrow six weeks previously. Flow cytometry analysis of (d) nuocytes (Lin−ICOS+T1/ST2+) and (e) CD4+ T cells, in MLN at day 5 post-infection in irradiated WT recipients reconstituted with either WT or _Rora_sg/sg total bone marrow six weeks previously. NS = non-significant; * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01. Data are representative of two independent experiments with 4 - 5 mice per group

To confirm that the impaired worm-clearance of _Rora_sg/sg mice was due to defects in the hematopoietic system, we generated bone marrow chimeras in which irradiated wild-type CD45.1 mice received CD45.2 _Rora_sg/sg or wild-type total bone marrow. Six weeks after reconstitution the mice were infected with N. brasiliensis and analysed 5-11 days post-infection. Whilst mice reconstituted with wild-type bone marrow rapidly expelled their worm burden, those reconstituted with _Rora_sg/sg bone marrow had impaired worm expulsion and failed to induce nuocyte expansion (Fig. 8c,d). However, with the exception of a single _Rora_sg/sg bone marrow reconstituted mouse, both groups had expelled the worms by day 11 (data not shown). T cells were comparable between the two groups (Fig. 8e), indicating that although worm expulsion is delayed in _Rora_sg/sg bone marrow recipients, the ability to mount an adaptive immune response remains intact. Thus, in the absence of Rorα nuocytes fail to develop and parasitic worm clearance is impaired.

DISCUSSION

Despite the fact that nuocytes share surface markers with lymphoid progenitor cells, here we demonstrate that nuocytes are a distinct cell type that arise from lymphoid lineage restricted cells. Using in vitro OP9-DL1 assays, we show that CLPs differentiate into nuocytes in the presence of IL-7, IL-33 and Notch signalling. The lymphoid ancestry of nuocytes was further demonstrated by in vivo CLP reconstitution assays. Furthermore, we found that individual DN1 and DN2 T cell progenitors retained the plasticity to develop into nuocyte-like cells in vitro following culture with IL-7, IL-33 and Notch activation. However, continued nuocyte development in Foxn1nu/nu mice indicated that the thymic microenvironment is not essential for nuocyte development. We found no evidence for nuocytes arising from CMPs. The retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor family member Rorα was essential for efficient nuocyte development.

Il7r gene expression studies designed to map the fate of cells that have previously expressed Il7r have demonstrated that lymphoid restricted progenitors are the major route to T cells 25. Our results from in vivo and in vitro assays demonstrate that IL-7 signalling is also essential for nuocyte development from CLPs when in combination with IL-33, and confirm the lymphoid origin of these cells.

We show that in vitro nuocyte development from CLPs depends on Notch signalling. Notch signalling plays many roles in hematopoiesis and the immune system. Notch1, Rbpjκ and Jagged1 deletions in embryos demonstrated that Notch signalling plays an essential role in definitive hematopoiesis, though it does not appear to be essential for the long-term expansion of HSCs in adult bone marrow 35,36. There is an essential role of Notch signalling during thymic T cell lineage commitment and maturation 35. Inducible ablation of Notch1 or Rbpjκ resulted in a block in T cell development and a concurrent outgrowth of B cells in the thymus 37,38. It is now evident that Notch1 maintains T cell potential whilst inhibiting a number of alternative cell fate potentials, including B, NK and myeloid cells 39,40 through its interaction with Dll4 41,42. Our data indicate that Notch signaling is also crucial for the development of nuocytes in vitro. These findings suggest that nuocytes may be more closely related to T cells than to B cells or NK cells, which do not require Notch signalling for their development. Notch signalling has been linked with TH2 cell differentiation 43,44, and inhibition of Notch signalling reduces allergic airway responses 45. Recent reports demonstrated a critical role for Notch signalling in ILC22 development in vitro 46. However, the physiological role of Notch in the development of either of these cells types in vivo remains to be established conclusively.

Rorγ has been shown recently to be essential for the development ILC17 and ILC22 from fetal liver precursors in a manner similar to LTi cells 47. However, Rorγ is not required for nuocyte development 1. Our data now demonstrate that nuocytes, by contrast, rely upon Rorα for their development. Although the role of Rorα in neuronal cell development has long been appreciated, its importance in the immune system has only recently surfaced 32. Following the finding that TH17 differentiation requires Rorγ, it was shown that a residual level of TH17 activity could be ascribed to Rorα, indicating that a low level of redundancy may exist between Rorα and Rorγ bioactivity. Rorα was recently associated with asthma in a genome-wide association study (GWAS) comparing individuals with diagnosed asthma and unaffected individuals 48. The same study also highlighted the asthma association of IL-33 and its receptor T1/ST2 (encoded by il1lr1), which are required for nuocyte development 1. The link between Rorα and asthma is also supported by lung function studies undertaken using Staggerer mice, which display a deficit in type-2 cytokine production and are partially protected from airways hyperreactivity 49. Nuocytes are up-regulated in mouse models of asthma and act as a major innate source of IL-13 6. Thus, Rorα expression in T1/ST2-positive nuocytes may underlie the association and role of Rorα in asthma in humans.

Collectively, our findings provide new insights into the lymphoid ancestry of nuocytes and demonstrate that nuocytes require the IL-7, IL-33, Notch and Rorα pathways for their development. Although the underlying molecular events leading to the differentiation of CLPs into nuocytes are still unclear, we have now identified Rorα as a critical transcription factor in nuocyte development. Our study shows a further, previously unrecognised, developmental pathway for CLPs and indicates an additional level of complexity in lymphoid cell development, with IL-33 and IL-25 signalling leading to the diversion of CLPs toward the nuocyte pathway for the provision of a rapid source of IL-13 and IL-5.

Supplementary Material

1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Bell for critical reading of the manuscript, A. Corcoran for providing IL-7Rα-deficient mice, M. Turner and E. Vigorito for providing B6/SJL mice, J.C. Zuniga-Pflucker for the use of OP9-DL1 cells, T. Honjo for access to Rbpjk conditional mice, M. Daly for flow cytometry and James Cruickshank and the Ares staff for experimental support. SHW and JLB were supported by a grant from Centocor Inc. JAW was supported by a grant from the American Asthma Foundation. PGF is supported by Science Foundation Ireland and National Children’s Research Centre. ANJM was supported by funding from the MRC, the American Asthma Foundation and Centocor Inc.

APPENDIX

METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice, B6/SJL (CD45.1 congenics) mice, _il33_-citrine mice (on BALB/c background, unpublished), _Il7ra_−/− mice 24 (on a C57BL/6 background), _Rag2_−/− mice 50 (backcrossed to BALB/c), Mx-Cre Rbpjκlox/lox mice and _Rora_sg/sg mice (Jackson Labs, on a C57BL/6 background) were bred in a specific-pathogen-free facility. Nude mice (Balb/cOlaHsd-_Foxn1_nu) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories. All animal experiments were undertaken with the approval of the UK Home Office.

Antibodies and reagents

For flow cytometry analysis: primary antibodies anti-CD3e (145-2C11) Pacific Blue/PE; anti-CD4 (GK1.5) FITC/PE; anti-CD8a (53-6.7) FITC/PE; anti-CD11b (M1/70) Pacific Blue/FITC/PECy7; anti-CD19 (1D3) Pacific Blue/PE; anti-B220 (RA3-6B2) Pacific Blue/PE; anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5) FITC; anti-CD11c (N418) FITC; anti-TER119 (TER-119) Pacific Blue; anti-Sca-1 (D7) FITC; anti-cKit (2B8) PE; anti-IL-7Ra (A7R34) biotin/PE; anti-CD45.1 (A20) eFluor™ 450; anti-CD45.2 (104) APC; anti-Flt-3 (A2F10) PE; anti-NKp46 (29A1.4) PE; anti-TCRγδ (eBioGL3) APC; anti-IL-5 (TRFK5) PE; anti-IL-13 (eBio13A) AF647 and unconjugated anti-CD16/32 (93) were from eBioscience, UK. Streptavidin conjugated to PE-Cy5, PE-Cy7 or AF647 were from eBioscience. Anti-ICOS (C398.4A) AF647 was purchased from Biolegend. Anti-IL17BR (D9.2) conjugated to biotin was as previously described 1. Anti-CD5 (53-7.3) FITC and anti-TCRβ (H57-597) PE were purchased from BD Bioscience. Anti-T1/ST2 (DJ8) conjugated to biotin was from mdbiosciences. All isotype control antibodies, rat anti-mouse IgG1 FITC/PE/biotin, IgG2a Pacific Blue/FITC/PE, IgG2b FITC/PE/APC and Armenian hamster anti-mouse IgG FITC/PE/AF647 were from eBioscience. For ELISA analysis: IL-4 (11B11 and BVD6-24G2) and IL-5 (TRFK5 and TRFK4) were from BD Bioscience. Anti-IL-13 (eBio13A) was from eBioscience. Recombinant mouse IL-4, IL-7 and Flt3 ligand (Flt3L) were from R&D system. Recombinant mouse IL-33 was from Biolegend. Recombinant mouse IL-5 and IL-13 were from eBioscience. Recombinant IL-25 was produced in-house by Centocor.

Flow cytometry analysis and cell sorting

Cells in PBS 2% FBS at 4°C were blocked with anti-CD16/32 antibody washed and incubated with biotinylated or fluorochrome conjugated antibodies. When necessary, the cells were incubated with fluorochrome conjugated streptavidin. Cells were analysed on FACS Calibur (BD Bioscience) or LSRII (BD Bioscience) or purified using a Mo-Flo cell sorter (Beckman Coulter) following manufacturer standard operating procedures. The data were analysed using FlowJo software version 9.1.

Bone marrow transplant

Donor cells were prepared from CD45.1+ B6/SJL mice. 200 HSCs (Lin−IL-7Rα−Sca-1+cKit+) or 2000 CLPs (Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3+) along with 1 × 106 C57BL/6 bone marrow carrier cells were resuspended in 100 μl of PBS and injected intravenously into lethally irradiated (450 rad × 2) C57BL/6 recipients. 6 - 7 weeks after reconstitution the mice were given three doses of recombinant mouse IL-25 (0.5 μg per dose) and cells analysed by flow cytometry analysis.

For Rorα experiments, lethally irradiated CD45.1+ B6/SJL mice were reconstituted with 2 × 106 bone marrow cells from either CD45.2+ _Rora_sg/sg mice or CD45.2+ wildtype littermate controls. After six weeks the mice were administered with either three daily doses of recombinant mouse IL-25 (0.4 μg per dose) or PBS. To produce mixed chimeras, CD45.1+ B6/SJL mice were reconstituted with a 1:1 mixture of CD45.1+ B6/SJL and CD45.2+ _Rora_sg/sg bone marrow cells. Six weeks later mice were administered with four daily doses of IL-25 (0.4 μg per dose).

In vitro nuocyte generation using OP9/OP9-DL1 co-culture

CMPs (Lin−IL-7Rα− Sca-1−cKit+) or CLPs (Lin−IL-7Rα+Flt3+) were sorted into 96 well plates containing OP9 or OP9 DL cells from bone marrow using a Mo-Flo cell sorter. 1500 - 2000 cells were co-cultured with OP9 stromal cells or OP9 cells expressing delta-like 1 ligand (OP9-DL1) with IMDM media in the presence of IL-7 (10 ng/ml) and Flt3 ligand (5 ng/ml) or IL-7 (10 ng/ml) and IL-33 (10 ng/ml). The cells were passaged into wells with freshly plated OP9 or OP9-DL1 cell monolayers at least once every 5 - 6 days or whenever necessary. In the case of single cell or 5 cells culture for CLP, CMP and HSC, the cells were sorted directly into a 96 well plate seeded with OP9 or OP9-DL1 cells with cytokines as described above.

For thymocytes, single cell suspensions were prepared from thymus and depleted magnetically of CD4+ (clone Gk1.5) and CD8+ (clone CD8b) cells using streptavidin Dynabeads (Invitrogen). The remaining cells were stained for CD4 (clone H129.19), CD8 (clone CD8a), CD11b, CD19, NK1.1, Ter119, Gr1, TCRγδ, CD3, ICOS (all FITC), CD44-PE, CD25-APC. Double negative thymocytes DN1 (CD25−CD44+), DN2 (CD25+CD44+) and DN3 (CD25+CD44−) were purified by flow cytometry as single cells or 100 cells per well of a 96 well plate pre-seeded with OP9 or OP9-DL1 stromal cells with cytokines as described above.

ELISA

Performed following standard manufacturer recommendations and analysed using a microplate reader (sunrise™, TECAN).

Intracellular cytokine staining

Intracellular cytokine staining was performed using the Fix/Perm kit (BD biosciences) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

In vitro differentiation of CMP

CMPs (Lin−IL-7Rα−Sca1−cKit+) were FACS sorted from the bone marrow of naïve mice and cultured with stem cell factor (1 ng/ml), IL-3 (10 ng/ml), IL-11 (10 ng/ml), GM-CSF (10 ng/ml), erythropoietin (5 ng/ml) and thrombopoietin (5 ng/ml). Cytospin slides were prepared on day 5 and stained with Giemsa.

RBPJκ deletion protocol and PCR

Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I)-poly(C)) (Invitrogen) was administered intraperitoneally to Mx-Cre Rbpjklox/lox mice every other day for 10 days (5 × 50 μg doses). Deletion of the floxed allele was assessed by PCR using the following primers: RBP_WT_sense 5′-CTTGATAATTCTGTAAAGAGA-3′, RBP_WT_anti-sense 5′-ACATTGCATTTTCACATAAAAAAGC-3′ and Rv_RBP_lox_del 5′-CCACAGGCAACAATTGAG-3′. Expected band sizes were as follows: wild type allele (720 bp), floxed allele (880 bp) and deleted allele (680 bp).

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR

Nuocytes (lineage− ICOS+) were FACS purified from the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes of mice challenged with three daily intraperitoneal injections of 2 μg rmIL-25. RNA was purified and reverse transcribed. Pre-designed Taqman™ primer and probe sets (Applied Biosystems) were used to quantify expression of Rora (Mm00443103_m1), Tcf7 (Mm00493445_m1), Bcl11b (Mm00480516_m1), Notch1 (Mm00435249_m1), Notch2 (Mm00803077_m1), Id2 (Mm00711781_m1) and Rorc (Mm01261022_m1). Expression of each gene was quantified relative to that of Gapdh.

Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection

Mice were injected subcutaneously with 300 live third stage N. brasiliensis larvae per mouse.

Histology

Tissues were taken and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin then embedded in paraffin and sectioned. Slides were stained with Periodic Acid Schiff’s reagent.

Reference

- 50.Shinkai Y, et al. RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Neill DR, et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–1370. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moro K, et al. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neill DR, McKenzie AN. Nuocytes and beyond: new insights into helminth expulsion. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price AE, et al. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11489–11494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003988107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallon PG, et al. Identification of an interleukin (IL)-25-dependent cell population that provides IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 at the onset of helminth expulsion. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1105–1116. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barlow JL, et al. Innate IL-13-producing nuocytes arise during allergic lung inflammation and contribute to airways hyperreactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang YJ, et al. Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:631–638. doi: 10.1038/ni.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fallon PG, et al. IL-4 induces characteristic Th2 responses even in the absence of IL-5, IL-9 and IL-13: analysis of functional redundancy using a novel panel of compound cytokine-deficient mice. Immunity. 2002;17:7–17. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00332-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grunig G, et al. Requirement for IL-13 independently of IL-4 in experimental asthma. Science. 1998;282:2261–2263. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mjosberg JM, et al. Human IL-25- and IL-33-responsive type 2 innate lymphoid cells are defined by expression of CRTH2 and CD161. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1055–1062. doi: 10.1038/ni.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angkasekwinai P, et al. Interleukin 25 promotes the initiation of proallergic type 2 responses. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1509–1517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang YH, et al. IL-25 augments type 2 immune responses by enhancing the expansion and functions of TSLP-DC-activated Th2 memory cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1837–1847. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmitz J, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buonocore S, et al. Innate lymphoid cells drive interleukin-23-dependent innate intestinal pathology. Nature. 2010;464:1371–1375. doi: 10.1038/nature08949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cella M, et al. A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature. 2009;457:722–725. doi: 10.1038/nature07537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cupedo T, et al. Human fetal lymphoid tissue-inducer cells are interleukin 17-producing precursors to RORC+ CD127+ natural killer-like cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:66–74. doi: 10.1038/ni.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luci C, et al. Influence of the transcription factor RORgammat on the development of NKp46+ cell populations in gut and skin. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:75–82. doi: 10.1038/ni.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanos SL, et al. RORgammat and commensal microflora are required for the differentiation of mucosal interleukin 22-producing NKp46+ cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:83–91. doi: 10.1038/ni.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Z, et al. Requirement for RORgamma in thymocyte survival and lymphoid organ development. Science. 2000;288:2369–2373. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vonarbourg C, et al. Regulated expression of nuclear receptor RORgammat confers distinct functional fates to NK cell receptor-expressing RORgammat(+) innate lymphocytes. Immunity. 2010;33:736–751. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison SJ, Weissman IL. The long-term repopulating subset of hematopoietic stem cells is deterministic and isolatable by phenotype. Immunity. 1994;1:661–673. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osawa M, Hanada K, Hamada H, Nakauchi H. Long-term lymphohematopoietic reconstitution by a single CD34-low/negative hematopoietic stem cell. Science. 1996;273:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He YW, Malek TR. Interleukin-7 receptor alpha is essential for the development of gamma delta + T cells, but not natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:289–293. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peschon JJ, et al. Early lymphocyte expansion is severely impaired in interleukin 7 receptor-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1955–1960. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlenner SM, et al. Fate mapping reveals separate origins of T cells and myeloid lineages in the thymus. Immunity. 2010;32:426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karsunky H, Inlay MA, Serwold T, Bhattacharya D, Weissman IL. Flk2+ common lymphoid progenitors possess equivalent differentiation potential for the B and T lineages. Blood. 2008;111:5562–5570. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-126219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakano T, Kodama H, Honjo T. Generation of lymphohematopoietic cells from embryonic stem cells in culture. Science. 1994;265:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.8066449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt TM, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Induction of T cell development from hematopoietic progenitor cells by delta-like-1 in vitro. Immunity. 2002;17:749–756. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franco CB, Chen CC, Drukker M, Weissman IL, Galli SJ. Distinguishing mast cell and granulocyte differentiation at the single-cell level. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radtke F, Wilson A, Mancini SJ, MacDonald HR. Notch regulation of lymphocyte development and function. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:247–253. doi: 10.1038/ni1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothenberg EV, Moore JE, Yui MA. Launching the T-cell-lineage developmental programme. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:9–21. doi: 10.1038/nri2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang XO, et al. T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors ROR alpha and ROR gamma. Immunity. 2008;28:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton BA, et al. Disruption of the nuclear hormone receptor RORalpha in staggerer mice. Nature. 1996;379:736–739. doi: 10.1038/379736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dzhagalov I, Giguere V, He YW. Lymphocyte development and function in the absence of retinoic acid-related orphan receptor alpha. J Immunol. 2004;173:2952–2959. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radtke F, Fasnacht N, Macdonald HR. Notch signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2010;32:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maillard I, et al. Canonical notch signaling is dispensable for the maintenance of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:356–366. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han H, et al. Inducible gene knockout of transcription factor recombination signal binding protein-J reveals its essential role in T versus B lineage decision. Int Immunol. 2002;14:637–645. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radtke F, et al. Deficient T cell fate specification in mice with an induced inactivation of Notch1. Immunity. 1999;10:547–558. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feyerabend TB, et al. Deletion of Notch1 converts pro-T cells to dendritic cells and promotes thymic B cells by cell-extrinsic and cell-intrinsic mechanisms. Immunity. 2009;30:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wada H, et al. Adult T-cell progenitors retain myeloid potential. Nature. 2008;452:768–772. doi: 10.1038/nature06839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hozumi K, et al. Delta-like 4 is indispensable in thymic environment specific for T cell development. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2507–2513. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koch U, et al. Delta-like 4 is the essential, nonredundant ligand for Notch1 during thymic T cell lineage commitment. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2515–2523. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amsen D, et al. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell. 2004;117:515–526. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanigaki K, et al. Regulation of alphabeta/gammadelta T cell lineage commitment and peripheral T cell responses by Notch/RBP-J signaling. Immunity. 2004;20:611–622. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okamoto M, et al. Jagged1 on dendritic cells and Notch on CD4+ T cells initiate lung allergic responsiveness by inducing IL-4 production. J Immunol. 2009;183:2995–3003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Possot C, et al. Notch signaling is necessary for adult, but not fetal, development of RORgammat(+) innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:949–958. doi: 10.1038/ni.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spits H, Di Santo JP. The expanding family of innate lymphoid cells: regulators and effectors of immunity and tissue remodeling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:21–27. doi: 10.1038/ni.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moffatt MF, et al. A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1211–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jaradat M, et al. Modulatory role for retinoid-related orphan receptor alpha in allergen-induced lung inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1299–1309. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1672OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1