Fresh Red Blood Cell Transfusion and Short-Term Pulmonary, Immunologic, and Coagulation Status: A Randomized Clinical Trial (original) (raw)

Abstract

Rationale: Transfusion-related pulmonary complications are leading causes of morbidity and mortality attributed to transfusion. Observational studies suggest an important role for red blood cell (RBC) storage duration in these adverse outcomes.

Objectives: To evaluate the impact of RBC storage duration on short-term pulmonary function as well as immunologic and coagulation status in mechanically ventilated patients receiving RBC transfusion.

Methods: This is a double-blind, randomized, clinical trial comparing fresh (≤5 d of storage) versus standard issue single-unit RBC transfusion in adult intubated and mechanically ventilated patients. The primary outcome is the change in pulmonary gas exchange as assessed by the partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen concentration ratio (ΔPaO2/FiO2). Secondary outcomes include changes in immune and coagulation status.

Measurements and Main Results: Fifty patients were randomized to receive fresh RBCs and an additional 50 patients to standard issue RBCs. Median storage age was 4.0 days (interquartile range, 3.0–5.0) and 26.5 days (interquartile range, 21.0–36.0) in the fresh RBC group and standard issue RBC group, respectively. No differences were noted in the primary outcome of ΔPaO2/FiO2 (difference between the mean ΔPaO2/FiO2 in the standard issue RBC group vs. the fresh RBC group, –11.5; 95% confidence interval, −35.3 to 12.3; P = 0.22). Similarly, no significant differences were noted in markers of immunologic or coagulation status.

Conclusions: In this randomized clinical trial, no differences were noted in early measures of pulmonary function or in immunologic or coagulation status when comparing fresh versus standard issue single-unit RBC transfusion.

Clinical trial registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00751322).

Keywords: critical care, transfusion, respiratory system, immunomodulation, clinical trial

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

A longer duration of red blood cell storage has been suggested to increase the risk of transfusion-related pulmonary complications. If confirmed, fresh red blood cell transfusion would be preferred in patients with or at risk for respiratory complications.

What This Study Adds to the Field

In this investigation, the impact of a single unit of fresh red blood cell transfusion on markers of pulmonary, inflammatory, and coagulation status was similar to the impact seen with the transfusion of a single unit of standard issue red blood cells.

Since the first successful attempt at blood storage almost a century ago, advances in extracorporeal red blood cell (RBC) preservation have incrementally prolonged the viability of stored RBCs. With contemporary preservative solutions, the accepted duration of RBC storage has now been extended to 42 days (1). In the past two decades, there has been increased interest in the time-dependent changes in RBC quantity and quality during this storage period. The various changes that occur within both the RBC and storage media during ex vivo preservation have been collectively termed the RBC “storage lesion.”

Importantly, alterations that occur during the RBC storage process are believed potentially responsible for many of the adverse effects associated with blood product administration (2). Among these concerns is a potentially increased risk of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) (3–6) as well as risk-adjusted mortality (7–10). Multiple publications have suggested that these associations become more significant with increased duration of RBC storage (8, 11–13). In a database analysis, Koch and colleagues found an association of RBC storage duration with mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery (8). This association was largely driven by an increased rate of respiratory complications. However, the observational nature of this investigation and concerns over residual confounding preclude definitive statements regarding causality. Moreover, evidence to the contrary exists as well (14–17), and the impact of RBC storage duration on development of transfusion-related complications remains a matter of debate (18, 19).

While the majority of TRALI cases are believed to be the result of an interaction between donor anti-HLA or anti-leukocyte antibodies and the cognate antigen on recipient leukocytes (20), a second “two-hit” model for TRALI has also been described (21). This model suggests that in a “primed” host, infusion of biologically active mediators activates sensitized neutrophils leading to endothelial damage, capillary leak, and clinical TRALI (6, 22). These biological response modifiers are believed to accumulate during storage of cellular blood products. However, the direct clinical impact of RBC storage duration on recipient immune status and pulmonary function remains poorly defined.

The objective of this investigation was to evaluate the impact of RBC storage duration on early pulmonary function as well as the immunologic and coagulation status of mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients in a double-blind, randomized clinical trial study design. We hypothesized that the transfusion of a single unit of RBCs with a short duration of storage would have less impact on early markers of pulmonary function than a single-unit of RBCs which had undergone storage of conventional duration. Similarly, we hypothesized that the affect of RBC transfusion on markers of immunologic and coagulation status would be attenuated in those who received fresh RBCs.

Methods

Study Design

This is a single-center, double-blind, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN) Institutional Review Board before initiating patient enrollment. The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines for reporting the results of a randomized clinical trial were used to guide the preparation of this article (23). This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov with the study identifier NCT00751322.

Study Population

Eligible patients were adults, aged 18 years or older, who were admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) at the Mayo Clinic. Both medical and surgical patients (including cardiac and neurologic surgery) were eligible for enrollment. The average annual ICU census at this institution is 14,800 patient visits. To be included, participants needed to be endotracheally intubated, mechanically ventilated, and have arterial access in situ. An order for RBC transfusion by the study participant's health care team was required before randomization. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) concurrent transfusion with another blood product, (2) emergency transfusion, and/or (3) hemodynamic instability as defined by the upward titration of vasoactive medications in the 2-hour interval before RBC transfusion.

Study Procedures

Patient identification.

To increase the feasibility of patient enrollment in this time-sensitive study, an automated electronic alert system continually assessed the electronic medical record of all mechanically ventilated adult ICU patients with an arterial catheter in situ. If a hemoglobin level below 9.5 g/dl was identified, an electronic message was sent to the participating study coordinator via e-mail/pager, indicating the identification of a potential study participant. Potential participants and/or their designated legally authorized representatives were then approached for informed consent. The objectives of the investigation as well as the potential risks and benefits of being included in the study protocol were described. Consenting participants’ names and clinic identification numbers were provided to the institutional blood bank and their electronic medical record was flagged to denote study participation. For each potential study participant, if an order for allogeneic RBC transfusion was subsequently placed by a member of the responsible health care team, this triggered a call to a study coordinator for full evaluation of inclusion and exclusion criteria. If all inclusion criteria were met and no exclusion criteria were present, study participants were allocated a treatment assignment (fresh vs. standard issue) for the first ordered RBC unit.

Intervention.

The intervention of interest in this investigation was the transfusion of a single unit of fresh (storage duration, ≤5 d) RBCs. The comparison group received a single unit of standard issue RBCs (historic median storage duration, 21 d; range, 7–42 d). The intervention (fresh vs. standard issue storage duration) was only for the first RBC unit administered after randomization. All subsequent RBC transfusions were standard issue. All RBC units administered (in both treatment arms) underwent prestorage leukocyte reduction. All transfusion decisions (study and nonstudy) were at the discretion of the responsible health care team with no involvement or influence by any member of the study team.

Additional study procedures.

After participant enrollment, providers were encouraged to use standardized ventilator settings. Specifically, it was recommended that all study participant lungs be mechanically ventilated with full ventilator support in a volume-controlled mode (assist-control or intermittent mandatory ventilation with pressure support) to guarantee consistent delivery of a tidal volume of 6–8 ml/kg (predicted body weight) with a frequency adjusted to ensure adequate minute ventilation. Systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressure were measured continuously and recorded at baseline (before RBC transfusion) and at the end of the intervention RBC unit transfusion. When central venous and/or pulmonary artery catheters were present, additional hemodynamic measurements (e.g., central venous pressure, pulmonary artery systolic pressure, and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure) were recorded at these time intervals as well. The fraction of inspired oxygen concentration (FiO2) was kept constant throughout the procedure, with titration allowed only to maintain arterial oxygen saturation, as determined by pulse oximetry, at 90% or more. The ventilator settings and FiO2 were not altered during the study unless clinically necessary. In the presence of patient–ventilator asynchrony and/or agitation, the following steps were encouraged in the following order: (1) adjust the peak inspiratory flow rate to at least 75 L/minute and trigger sensitivity to −1 cm H2O (or flow trigger, ∼1–2 L/min); (2) increase the tidal volume by 1 ml/kg to a maximum of 10 ml/kg predicted body weight; and (3) additional sedation and/or neuromuscular blockade should be administered per standard clinical practice, preferably using short-acting agents such as propofol.

Measurements and outcome assessments.

The primary outcome measure was the change in pulmonary gas exchange as assessed by the ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen concentration (ΔPaO2/FiO2 ratio). FiO2 was recorded into the case report forms by a study coordinator at the time of arterial blood gas acquisition. Secondary assessments of changes in pulmonary function included post-transfusion changes in peak and plateau airway pressures, static and dynamic respiratory system compliance, and fraction of dead space ventilation (Vd/Vt). Dynamic respiratory system compliance and Vd/Vt were measured with the NICO cardiopulmonary management system (Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA). Additional secondary outcome measures included changes in markers of immune status including tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-8, and C-reactive protein. Coagulation status was assessed by platelet count, fibrinogen concentration, and antithrombin consumption. Baseline measurements were obtained in the 2-hour interval before transfusion. Post-transfusion measurements were obtained on completion of the intervention RBC transfusion and within 2 hours of initiation of the intervention RBC transfusion. All cardiopulmonary measurements were performed by licensed respiratory therapists who were blinded to treatment assignment and were trained in the use of the NICO cardiopulmonary management system. Standard operating procedures were developed before study initiation for all bedside and laboratory measurements as well as for all outcome assessments. Patient-important outcomes included new or worsening acute lung injury (ALI), changes in organ failures (assessed on the basis of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [SOFA] score), and mortality. ALI and SOFA scores were assessed over a 48-hour interval after the intervention RBC transfusion. Mortality was assessed at hospital discharge. Standard definitions were used for ALI (24) and the SOFA score (25). ALI diagnoses were adjudicated by two members of the study team (G.A.W. and D.J.K.), both of whom were blinded to intervention allocation status. Disagreements were handled by a third reviewer who was also blinded to the intervention status (O.G.).

Sample Size

The study size of 100 patients was determined a priori on the basis of a desire to detect a 5% difference in PaO2/FiO2 between treatment groups. Assuming a control group PaO2/FiO2 value of 200 with a standard deviation of 17 (noted in our preliminary data), we determined the need to obtain a sample size of 46 patients per group (two-sided α of 0.05 and a power of 0.80). To account for potential unexpected loss of patient data (e.g., no transfusion in a randomized patient), we added an additional four patients to each group.

Randomization and Blinding

Randomization was performed using a simple computer-generated list, known only to the statistician who generated the coded list, with a block size of four. Participants were randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio. Treatment allocation was determined by personnel within the blood bank at the time of RBC issue by opening sealed opaque envelopes containing the randomization codes. Per hospital practice, a designated transfusion nurse is responsible for checking the compatibility of the planned RBC unit with the recipient's blood type and antibody status within the blood bank. The RBC product outdate is also assessed by the responsible transfusion nurse. On confirming an appropriate RBC product, the transfusion nurse transports the ordered RBCs to the patient's bedside, reconfirms a correct patient and blood product match, and initiates the transfusion. The clinical service responsible for ordering the blood product is not involved in this process and was not made aware of the patient's randomization status. The product expiration date was not concealed during the transfusion process. However, study participants and all study investigators remained blinded to treatment allocation status for the duration of the study procedures.

Statistical Analysis

The null hypothesis for this investigation was that the transfusion of a single unit of fresh RBCs (storage duration, ≤5 d) would produce the same change in PaO2/FiO2 as would the transfusion of a single standard issue unit of RBCs. Participant outcomes were analyzed according to the treatment group to which they were assigned (intention-to-treat). Normally distributed continuous data are summarized using means ± standard deviations; whereby, skewed continuous data are summarized using median values with 25–75% interquartile ranges. Categorical variables are presented as counts with percentages. For univariate analyses, comparisons of continuous outcomes between the two groups were performed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables.

To more fully assess the impact of RBC storage duration on acute and subacute organ function, SOFA scores were evaluated in two complementary ways. In the first analysis, differences in the mean change in SOFA scores (ΔSOFA score = SOFA score at 48 h − SOFA score at baseline) for the fresh RBC and standard issue RBC cohorts were compared. In the second analysis, baseline SOFA scores and the serial changes in SOFA scores measured at 6-hour intervals from transfusion end to 48 hours after transfusion were compared. For this later analysis, a random coefficients model (26) was used to compare (1) the population SOFA score at baseline between the study arms and (2) the population SOFA score change rate between the study arms. In this study, the random coefficient model predicted the SOFA score time series for a given patient. The fixed component of the model included (1) a dummy variable for the study arm, (2) a continuous variable for hours when the SOFA score was measured, and (3) their interaction. The random component of the model included the patient's intercept and slope terms. The covariance between the random intercept and slope was specified as unstructured. The coefficient for the dummy variable estimated the difference in SOFA score at baseline between the two study arms. The P value associated with this coefficient tested whether the coefficient was significantly different from zero. Similarly, the coefficient for the interaction term estimated the difference in SOFA score trajectory between the study arms with a similar interpretation for the P value. The random coefficient model was implemented in SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), using the PROC MIXED procedure.

Results

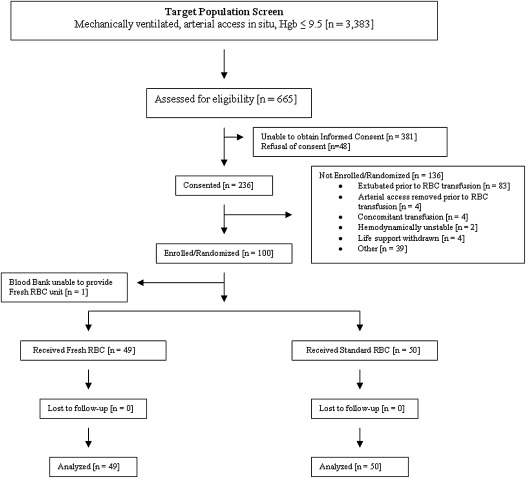

Between June 2008 and May 2010, a total of 3,383 adult intensive care unit patients were mechanically ventilated, had an arterial catheter in situ, and had a hemoglobin value not exceeding 9.5 g/dl. A total of 665 of these were approached for informed consent and potential inclusion in this trial. Of these 665 potential study participants, 100 were prospectively enrolled. Fifty patients were randomized to transfusion of fresh RBCs with an additional 50 patients randomized to standard-issue RBC transfusion. The study population flow is shown in Figure 1. One recipient randomized to receive fresh RBCs was noted to have a positive antibody screen and an appropriately cross-matched fresh RBC unit was not available. This participant was excluded from the study after randomization, but before the administration of an RBC transfusion. As post-transfusion data were not obtained, this study participant was not included in the intention-to-treat analyses. The remaining members of the study population received their study RBC transfusion and were included in the analyses.

Figure 1.

Study participation flow diagram. Hgb = hemoglobin; RBC = red blood cells.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The randomization procedures were effective, with relatively equal distributions of most baseline variables. Specifically, baseline demographics and ICU admission characteristics were similar, as were most ALI risk modifiers. Baseline cardiopulmonary parameters and markers of immune and coagulation status were also balanced. The median baseline tidal volumes were slightly higher, and the proportion of patients who were receiving low-tidal volume ventilation (<8 ml/kg predicted body weight) was slightly lower in the fresh RBC group (Table 1). However, neither of these differences was statistically significant.

TABLE 1.

DEMOGRAPHICS AND BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

| Parameter | Fresh RBCs (n = 50) | Standard Issue RBCs (n = 50) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, yr* | 65 (47–73) | 65 (52–72) |

| Sex, female† | 22 (44) | 21 (42) |

| ICU admission characteristics | ||

| ICU admission indication† | ||

| Medical | ||

| CNS | 2 (4) | 4 (8) |

| Cardiac | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Pulmonary | 20 (40) | 27 (54) |

| Renal | 1 (2) | 1(2) |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (8) | 4 (8) |

| Hematologic | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

| Sepsis | 4 (8) | 2 (4) |

| Trauma (nonoperative) | 4 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Postoperative | ||

| Cardiac | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Noncardiac | 12 (24) | 8 (16) |

| APACHE III score* | 82 (64–108) | 82 (71–112) |

| Pretransfusion SOFA score* | 10 (7–14) | 10 (8–13) |

| Acute lung injury risk modifiers | ||

| Diabetes mellitus† | 9 (18) | 14 (28) |

| Cirrhosis† | 1 (2) | 3 (6) |

| COPD† | 7 (14) | 6 (12) |

| Restrictive lung disease† | 5 (10) | 6 (12) |

| BMI, kg/m2* | 28.3 (25.1–32.1) | 30.8 (26.2–35.2) |

| Smoking† | ||

| Never | 22 (44) | 21 (42) |

| Former | 22 (44) | 25 (50) |

| Active | 6 (12) | 4 (8) |

| Alcohol use† | 6 (12) | 5 (10) |

| Chemotherapy† | 17 (34) | 18 (36) |

| Immunosuppression† | 10 (20) | 9 (18) |

| RBC units before study transfusion*‡ | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| FFP units before study transfusion*‡ | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| Platelet units before study transfusion*‡ | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| Fluid balance in prior 24 h, L* | 1.5 (0.5–4.5) | 1.7 (−0.1 to 3.6) |

| Ventilator settings | ||

| Tidal volume, ml/kg PBW* | 7.4 (6.5–9.2) | 7.0 (6.1–8.4) |

| Tidal volume < 8 ml/kg PBW† | 31 (62) | 34 (69) |

| PEEP, cm H2O* | 5 (5–10) | 7.5 (5–10.5) |

| FiO2* | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) |

| Cardiopulmonary status | ||

| CV SOFA score* | 3 (1–4) | 3 (1–3) |

| Mean arterial blood pressure, mm Hg* | 71 (65–86) | 69 (62–80) |

| Cardiac index, L/min/m2* | 2.4 (2.0–3.6) | 2.4 (1.8–3.1) |

| Central venous pressure, mm Hg (n = 48)* | 13 (7–17) | 10 (6–15) |

| Prevalent acute lung injury† | 23 (46) | 30 (60) |

| PaO2/FiO2, mm Hg* | 275 (183–333) | 264 (160–334) |

| PaCO2, mm Hg* | 39.5 (35.0–45.0) | 42.5 (37.0–50.0) |

| Vd/Vt, ml (n = 93)* | 0.5 (0.5–0.6) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) |

| Static respiratory system compliance, ml/cm H2O (n = 52)* | 33.0 (26.9–46.7) | 30.8 (23.6–40.8) |

| Dynamic respiratory system compliance, ml/cm H2O (n = 66)* | 29.6 (22.3–37.5) | 26.7 (18.8–35.0) |

| Baseline markers of immunologic status | ||

| Leukocyte count, ×109/L* | 9.7 (5.8–16.5) | 9.3 (6.1–13.1) |

| TNF-α, pg/ml* | 3.4 (1.9–5.2) | 3.1 (1.7–4.3) |

| IL-8, pg/ml* | 46.6 (23.3–95.8) | 43.8 (24.6–99.8) |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dl* | 11.5 (6.9–17.3) | 14.5 (8.4–20.3) |

| Baseline markers of hematologic and coagulation status | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dl* | 7.8 (7.1–8.8) | 7.9 (7.5–8.4) |

| Platelet count, ×109/L* | 109 (54–189) | 119 (51–195) |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dl* | 435 (295–576) | 474 (285–705) |

| Antithrombin consumption* | 37 (22–51) | 39 (22–51) |

The median duration of RBC storage was 4.0 days (25–75% interquartile range, 3.0–5.0 d) in the fresh RBC cohort and 26.5 days (25–75% interquartile range, 21.0–36.0 d) in the standard issue arm. In the standard issue group, four patients received an RBC unit that had been stored for 14 days or less, nine received an RBC unit that had been stored between 15 and 21 days, and the remainder received an RBC unit that had been stored for more than 21 days. Eighty-eight participants (89%) received an ABO- and Rh-identical RBC unit, with the remaining 11 participants (11%) receiving an ABO- and Rh-compatible unit. When comparing the fresh and the standard issue cohorts, there was no difference in the proportion of study participants who received nonidentical, ABO-compatible RBCs (16.3 vs. 6.0%, respectively; P = 0.12). Similarly, the proportion of non–group O recipients who received group O RBC units was similar in the two groups (21.9 vs. 12.0%; P = 0.49). RBC donor and recipient blood types are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

RED BLOOD CELL DONOR AND RECIPIENT BLOOD TYPE

| Blood Type* | Fresh RBCs (n = 49) | Standard Issue RBCs (n = 50) |

|---|---|---|

| Donor blood type | ||

| A positive | 20 (41) | 17 (34) |

| A negative | 4 (8) | 4 (8) |

| B positive | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| B negative | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| AB positive | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| AB negative | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| O positive | 21 (43) | 26 (52) |

| O negative | 3 (6) | 2 (4) |

| Recipient blood type | ||

| A positive | 20 (41) | 18 (36) |

| A negative | 4 (8) | 4 (8) |

| B positive | 7 (14) | 2 (4) |

| B negative | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| AB positive | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| AB negative | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| O positive | 14 (29) | 23 (46) |

| O negative | 3 (6) | 2 (4) |

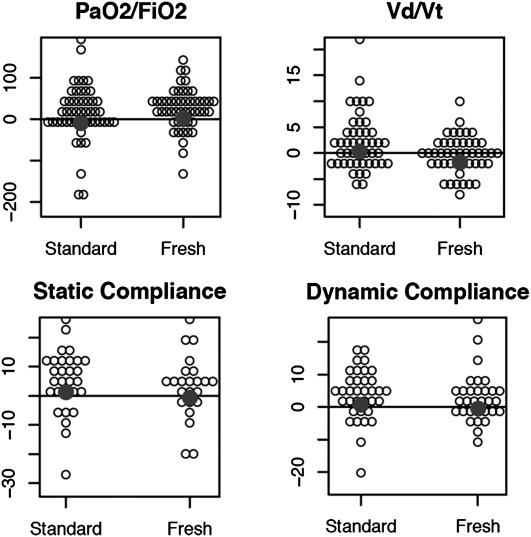

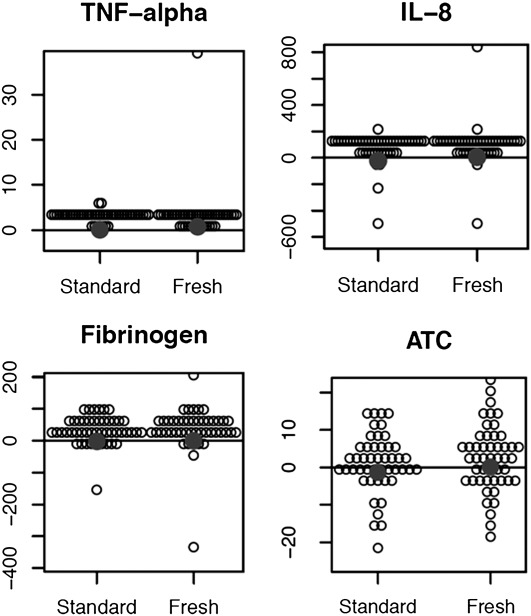

The mean ± standard deviation time from initiation of the intervention RBC transfusion to the post-transfusion measurements was 1.8 ± 0.46 hours for the fresh RBC cohort and 1.9 ± 0.63 hours for those receiving standard issue RBCs (P = 0.59). Univariate analyses of pulmonary function, immunologic, and coagulation status in those receiving fresh RBC transfusion compared with standard issue RBCs can be seen in Table 3. No significant differences were noted in the primary outcome of change in PaO2/FiO2 ratio (2.5 ± 49.3 vs. −9.0 ± 69.8; fresh RBCs vs. standard issue RBCs; P = 0.22). No significant differences were identified in any of the other a priori intermediate outcome measures of pulmonary function (Vd/Vt, dynamic and static pulmonary compliance), immunologic status (tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-8, C-reactive protein), or coagulation status (fibrinogen concentration, antithrombin consumption). Between-group changes in measures of pulmonary status are displayed in Figure 2. Between-group changes in measures of immune and coagulation status can be seen in Figure 3. Of note, the median tidal volumes at time point 2 (after RBC transfusion) were similar in the fresh RBC cohort when compared with the standard issue group (7.7 [6.9–9.2] vs. 7.5 [6.3–8.4] ml/kg predicted body weight; P = 0.23). The proportion of patients receiving low tidal volume ventilation (<8 ml/kg predicted body weight) was also similar in the two groups (58.0 vs. 66.7%, fresh RBCs vs. standard-issue RBCs, respectively; P = 0.38). In addition to the intermediate outcomes, no significant differences were noted in patient-important outcomes such as new or progressive ALI (fresh vs. standard issue RBCs, 2% vs. 6%; odds ratio [95% confidence interval], 0.33 [0.01 to 4.28]; P = 0.62), organ failures (ΔSOFA score in fresh vs. standard issue RBCs, −0.7 vs. −1.0; difference of the means for standard issue and fresh RBCs, −0.3 [−1.6 to 1.0]; P = 0.80), or mortality (fresh vs. standard issue RBCs, 35 vs. 44%; 0.68 [0.28–1.64]; P = 0.41). The temporal changes in each component of the SOFA score as well as the total SOFA score during the 48-hour interval after study RBC transfusion can be seen in Table 4.

TABLE 3.

STUDY PARTICIPANT OUTCOMES

| Outcomes*† | Fresh RBC Cohort (n = 49) | Standard Issue RBCs (n = 50) | Difference of the Means for Standard Issue and Fresh RBCs (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary | ||||

| ΔPaO2/FiO2, mm Hg | 2.5 (49.3) | −9.0 (69.8) | −11.5 (−35.3, 12.3) | 0.22 |

| ΔVd/Vt, % | −1.8 (3.7) | 0.3 (5.4) | 2.1 (0.2, 4.0) | 0.10 |

| ΔStatic compliance, ml/cm H2O (n = 52) | −0.5 (11.0) | 1.3 (10.9) | 1.8 (−4.2, 7.8) | 0.34 |

| ΔDynamic compliance, ml/cm H2O (n = 66) | −0.4 (7.8) | 0.7 (7.8) | 1.1 (−2.7, 4.9) | 0.16 |

| Immunologic | ||||

| ΔTNF-α, pg/ml | 0.7 (5.8) | 0.1 (1.1) | −0.6 (−2.3, 1.1) | >0.99 |

| ΔIL-8, pg/ml | 5.3 (153.7) | −23.2 (100.3) | −28.5 (−80.6, 23.6) | 0.50 |

| ΔCRP, mg/dl | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.7 (2.2) | 0.3 (−0.4, 1.0) | 0.88 |

| Coagulation | ||||

| ΔFibrinogen, mg/dl | 0.9 (71.4) | −2.2 (42.1) | −3.1 (−27.0, 20.8) | 0.36 |

| ΔATC | 0.1 (8.7) | −1.2 (8.1) | −1.3 (−4.7, 2.1) | 0.59 |

Figure 2.

Changes in markers of pulmonary function among those receiving fresh versus standard issue RBC transfusion. PaO2/FiO2 = ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen; RBC = red blood cells; Vd/Vt = ratio of dead space volume to tidal volume. Summary statistics and P values for the hypothesis tests performed are presented in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Changes in markers of immune and coagulation status among those receiving fresh versus standard issue RBC transfusion. ATC = antithrombin consumption; RBC = red blood cell; TNF = tumor necrosis factor. Summary statistics and P values for the hypothesis tests performed are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 4.

COMPARISONS OF CHANGES IN SEQUENTIAL ORGAN FAILURE ASSESSMENT SCORE FROM END OF STUDY RED BLOOD CELL TRANSFUSION TO 48 HOURS AFTER TRANSFUSION IN THOSE WHO RECEIVED FRESH VERSUS STANDARD ISSUE RED BLOOD CELLS

| Time | Neurologic | Cardiovascular | Respiratory | Renal | Hepatic | Hematologic | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh (n = 49) | |||||||

| End transfusion* | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.6) | 1.9 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.6) | 0.7 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.5) | 8.9 (3.7) |

| 6 h* | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.6) | 2.0 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.6) | 0.7 (2.3) | 1.5 (1.3) | 8.9 (3.7) |

| 12 h* | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.6) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.6) | 0.8 (1.3) | 1.5 (1.3) | 8.8 (4.0) |

| 18 h* | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.6) | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.5) | 0.8 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.3) | 8.8 (3.9) |

| 24 h* | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.3 (1.5) | 2.1 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.5) | 0.8 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.3) | 8.5 (4.5) |

| 30 h* | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.6) | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.0 (1.5) | 0.9 (1.5) | 1.5 (1.3) | 8.4 (4.6) |

| 36 h* | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.5) | 2.2 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.5) | 0.8 (1.5) | 1.4 (1.4) | 8.3 (4.6) |

| 42 h* | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.5) | 2.1 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.6) | 0.8 (1.5) | 1.5 (1.4) | 8.4 (4.8) |

| 48 h* | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.5) | 2.1 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.5) | 0.8 (1.5) | 1.6 (1.4) | 8.4 (4.7) |

| Standard issue (n = 50) | |||||||

| End transfusion* | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.7) | 0.9 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.4) | 9.3 (4.0) |

| 6 h* | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.4 (1.5) | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.4 (1.7) | 0.9 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.4) | 9.0 (3.9) |

| 12 h* | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.3 (1.5) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.7) | 1.0 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.5) | 9.1 (4.3) |

| 18 h* | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.2 (1.5) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.8) | 1.0 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.4) | 9.0 (4.4) |

| 24 h* | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.4 (1.6) | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.7) | 1.0 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.4) | 9.3 (4.7) |

| 30 h* | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.3 (1.5) | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.7) | 1.0 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.4) | 9.0 (4.4) |

| 36 h* | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.3 (1.4) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.7) | 1.0 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.4) | 8.9 (4.3) |

| 42 h* | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.7) | 1.0 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.4) | 8.5 (4.4) |

| 48 h* | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.1 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.7) | 0.9 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.4) | 8.5 (4.3) |

| Comparison of intercept P value | 0.900 | 0.416 | 0.861 | 0.424 | 0.463 | 0.511 | 0.670 |

| Comparison of slope P value | 0.865 | 0.168 | 0.271 | 0.485 | 0.870 | 0.412 | 0.861 |

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial, transfusion of a single unit of fresh RBCs to hemodynamically stable ICU patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation had no significant influence on early markers of pulmonary function, immunologic status, or coagulation status when compared with single-unit RBC transfusion of conventional storage duration. Similarly, no differences were noted in patient-important outcomes such as new or progressive ALI, number of organ failures during the 48-hour interval after study RBC transfusion, or in hospital mortality.

The findings of this investigation arise in the midst of a growing body of mechanistic data describing alterations in both the RBCs and their medium during the storage process. Increasingly, these alterations have been purported to potentially influence the recipient's respiratory and immunologic response to the transfused blood product. An example of such a change includes the depletion of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate with a resultant leftward shift in the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve. This has been postulated to lead to reduced oxygen delivery (27, 28). In addition, ATP depletion (29, 30) and reductions in _S_-nitrosothiol bioactivity (31, 32) are believed to potentially impact the vasodilatory response to regional hypoxia and reduce RBC deformability, which may impede RBC transit through the microcirculation (33–35). In addition, immunologically active biologic response modifiers within the RBC storage medium such as soluble CD40 ligand (6, 36) and lysophosphatidylcholines (22, 37) have been associated with the development of ALI. A number of observational clinical studies also suggest an association between RBC transfusion and respiratory complications such as transfusion-related acute lung injury (38, 39), transfusion-associated circulatory overload (40), and respiratory insufficiency with the need for prolonged mechanical ventilation (8). It has been suggested that the duration of RBC storage may be an important contributing factor in these associations (6, 8, 22, 41, 42). An important limitation with the majority of these studies has been their observational study design, with the unavoidable potential for bias and residual confounding.

In contrast, numerous additional studies have failed to support the potential association between RBC storage duration and adverse clinical outcomes. Weiskopf and colleagues have reported similar efficacy in reversing anemia-induced neurocognitive deficits with both fresh (storage, 3.5 h) and stored (storage, 3 wk) RBCs (43). Similarly, Walsh and colleagues noted similar effects of RBC transfusion on both regional and global markers of oxygenation when comparing fresh RBCs (stored ≤5 d) with RBCs that had undergone more prolonged storage (stored ≥20 d) (44). Regarding the effect of storage duration on transfusion-related pulmonary complications, Vamvakas and Carven found no association between storage age and the probability of intubation or the duration of mechanical ventilation in patients receiving blood transfusion for coronary artery bypass surgery (45). Numerous other investigators have also failed to associate duration of RBC storage with adverse respiratory outcomes (46–49).

The present investigation provides data from the first randomized clinical trial addressing the potential influence of RBC storage duration on post-transfusion pulmonary function, immunologic status, and coagulation status. In contrast to much of the mechanistic and observational data described previously, our results do not support a significant relationship between RBC storage duration and altered respiratory, immunologic, or coagulation parameters in the early phases after RBC transfusion. Although the discrepancies between the current work and previous observational studies cannot be fully explained, they may in part be the result of differing study designs. More specifically, the double-blind randomized clinical trial design of the present investigation is expected to have more fully addressed concerns related to bias and unmeasured confounding. These concerns are a pervasive challenge in observational studies. In addition, the present study design mandated that all patients receive a similar RBC dose (a single unit). Importantly, many previous investigations have failed to adequately adjust for RBC dose. Indeed, concerns regarding the unequal distribution of RBC dose when comparing fresh with “older” RBC units has been discussed (50). Third, the use of prestorage leukocyte reduction for all transfusions administered in this study may also partially explain our novel findings. Previous work has suggested that leukocytes carried over during the processing of the RBC fraction can accelerate the RBC storage lesion (51, 52), and others have shown that leukocyte burden increases the adhesion of stored RBCs to the vascular endothelium (53, 54). Prestorage leukoreduction has been shown to attenuate the accumulation of bioactive substances in stored RBC units (55–57) as well as the adhesiveness of stored RBCs (58).

The major strengths of this investigation include the double-blind, randomized trial design and the innovative near–real time identification of the study population with highly granular data acquisition after RBC administration. In contrast to the existing observational studies, the experimental design of the present investigation allows the first formal assessment of the potential cause–effect relationship between transfusion of RBCs of differing storage age and altered pulmonary, immunologic, and coagulation function. The novel techniques used to identify critically ill patients undergoing RBC transfusion allowed for a unique, detailed analysis of the early changes in respiratory physiology as well as immunologic and coagulation status in mechanically ventilated ICU patients. This detailed assessment of cardiopulmonary status was further strengthened by the use of the NICO cardiopulmonary management system. The completeness of follow-up and short evaluation interval also limit the potential for bias as well as confounding cointerventions such as ventilator management, hemodynamic resuscitation, fluid therapy, concomitant transfusions, and other health care delivery factors.

Importantly, a number of potential limitations with the current investigation deserve note as well. Although the short duration of follow-up for the primary outcome (median, 1.9 hours for the fresh RBC group and 1.8 hours for the standard issue RBC cohort) allowed a detailed assessment of the early changes associated with RBC transfusion, mitigating many of the important confounding cointerventions that occur in clinical practice, delayed responses to the transfused RBC units would not have been identified in this investigation. As such, we are unable to comment on the impact of RBC storage duration on more delayed alterations in lung function, immunologic status, or the coagulation cascade. Moreover, as the response of IL-8 to the transfusion episode may have been slightly more delayed, it is possible that our second measurement missed the peak value for this specific inflammatory marker. An additional limitation is this study's limited sample size. The a priori sample size was calculated to assess between-group differences in post-transfusion PaO2/FiO2 ratio. It is clearly possible that more subtle associations were missed because of type II error (false negative findings). In addition, the standard deviation for the primary outcome (PaO2/FiO2) was larger than planned (117 vs. 17 mm Hg). As such, the sample size of the enrolled population may not have been sufficient to capture the intended 5% difference in PaO2/FiO2 between the fresh RBC and standard-issue RBC groups. However, our post-hoc power analysis indicates that the sample size achieved (n = 100) provided 80% power to detect a 39.6–mm Hg or greater difference in the mean value of ΔPaO2/FiO2 between the two groups (two-sided α of 0.05). Therefore, although not sufficiently powered to detect minor differences in oxygenation, adequate power was present for detecting more clinically significant differences. Importantly, the design of this investigation also restricted the transfusion episode to a single unit of RBCs. Although improving our ability to limit confounding cointerventions and to gather detailed information on the impact of the storage age of a single unit of RBC on recipient respiratory function, immunologic status, and coagulation status, this design precludes comment on either safety or risk with longer RBC storage durations in larger volume RBC transfusion episodes. We also recognize that although we did not identify associations between RBC storage duration and patient important outcomes such as new or worsening ALI, number of organ failures, or mortality, these results must be interpreted with caution as the study was not sufficiently powered to adequately assess these clinical end points. Nonetheless, the lack of evidence for an impact of RBC storage duration on the intermediate outcomes evaluated supports the findings of no meaningful impact on the clinically important outcomes assessed. Finally, we must also acknowledge the single-center, tertiary care setting in which the study procedures were performed. Specifically, unique aspects of the environment in which the study was performed may limit the external validity of the study's findings and the generalizability of the study results.

Conclusions

In this double-blind, randomized clinical trial evaluating the safety of fresh versus standard issue single-unit RBC transfusion in hemodynamically stable patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, no differences were noted in early measures of pulmonary function, immunologic status, or coagulation status. Specifically, these data exclude a 39.6–mm Hg or greater difference in the mean value of ΔPaO2/FiO2 at the 2-hour time point after a single unit of fresh RBC versus standard issue RBC transfusion with a power of 0.8 and a two-sided α of 0.05. Similarly, no differences were noted in patient-important outcomes such as mortality or organ failures. The results of this trial do not support a significant role for RBC storage duration in the development of transfusion-related pulmonary complications. Moreover, these results would suggest that well-designed clinical trials randomizing patients to “fresh-only” RBCs versus “prolonged storage–only” RBCs can be performed ethically. Additional ongoing clinical trials will further define the impact of RBC storage duration on other patient-oriented transfusion-related outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Heath (grant P50HL 81027-3) and the Department of Critical Care Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine (Rochester, MN).

Author Contributions: D.J.K. contributed to the acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of the study results. R.K. contributed to the study design and procedures and the acquisition of the data. R.B.W. contributed to the study conception and design as well as the interpretation of the data. G.A.W. contributed to the study procedures and acquisition of the study data. C.M.v.B. contributed to the study conception and design as well as the study procedures. J.L.W. contributed to the study procedures as well as the interpretation of the study results. M.M. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data and study results R.D.H. contributed to the study conception and design as well as the interpretation of the study results. O.G. contributed to the study conception and design as well as the analysis and interpretation of the study results. All of the listed authors contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript and all have provided approval to the final version of the submitted manuscript.

References

- 1.American Association of Blood Banks. Standards for blood bank transfusion services. Washington, DC: American Association of Blood Banks; 1997.

- 2.Karam O, Tucci M, Bateman ST, Ducruet T, Spinella PC, Randolph AG, Lacroix J. Association between length of storage of red blood cell units and outcome of critically ill children: a prospective observational study. Crit Care 2010;14:R57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardo LJ, Wilder D, Salata J. Neutrophil priming, caused by cell membranes and microvesicles in packed red blood cell units, is abrogated by leukocyte depletion at collection. Transfus Apheresis Sci 2008;38:117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watkins TR, Rubenfeld GD, Martin TR, Nester TA, Caldwell E, Billgren J, Ruzinski J, Nathens AB. Effects of leukoreduced blood on acute lung injury after trauma: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2008;36:1493–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao RS, Howard CA, Teague TK. Pulmonary endothelial permeability is increased by fluid from packed red blood cell units but not by fluid from clinically-available washed units. J Trauma 2006;60:851–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan SY, Kelher MR, Heal JM, Blumberg N, Boshkov LK, Phipps R, Gettings KF, McLaughlin NJ, Silliman CC. Soluble CD40 ligand accumulates in stored blood components, primes neutrophils through CD40, and is a potential cofactor in the development of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Blood 2006;108:2455–2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koch CG, Li L, Duncan AI, Mihaljevic T, Cosgrove DM, Loop FD, Starr NJ, Blackstone EH. Morbidity and mortality risk associated with red blood cell and blood-component transfusion in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1608–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, Figueroa P, Hoeltge GA, Mihaljevic T, Blackstone EH. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1229–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marik PE, Corwin HL. Efficacy of red blood cell transfusion in the critically ill: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med 2008;36:2667–2674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy GJ, Reeves BC, Rogers CA, Rizvi SI, Culliford L, Angelini GD. Increased mortality, postoperative morbidity, and cost after red blood cell transfusion in patients having cardiac surgery. Circulation 2007;116:2544–2552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purdy FR, Tweeddale MG, Merrick PM. Association of mortality with age of blood transfused in septic ICU patients. Can J Anaesth 1997;44:1256–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zallen G, Offner PJ, Moore EE, Blackwell J, Ciesla DJ, Gabriel J, Denny C, Silliman CC. Age of transfused blood is an independent risk factor for postinjury multiple organ failure. Am J Surg 1999;178:570–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Offner PJ, Moore EE, Biffl WL, Johnson JL, Silliman CC. Increased rate of infection associated with transfusion of old blood after severe injury. Arch Surg 2002;137:711–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van de Watering L, Lorinser J, Versteegh M, Westendord R, Brand A. Effects of storage time of red blood cell transfusions on the prognosis of coronary artery bypass graft patients. Transfusion 2006;46:1712–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vamvakas EC, Carven JH. Transfusion and postoperative pneumonia in coronary artery bypass graft surgery: effect of the length of storage of transfused red cells. Transfusion 1999;39:701–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor RW, O'Brien J, Trottier SJ, Manganaro L, Cytron M, Lesko MF, Arnzen K, Cappadoro C, Fu M, Plisco MS, et al. Red blood cell transfusions and nosocomial infections in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2006;34:2302–2308, quiz 2309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yap CH, Lau L, Krishnaswamy M, Gaskell M, Yii M. Age of transfused red cells and early outcomes after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;86:554–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steiner ME, Assmann SF, Levy JH, Marshall J, Pulkrabek S, Sloan SR, Triulzi D, Stowell CP. Addressing the question of the effect of RBC storage on clinical outcomes: the Red Cell Storage Duration Study (RECESS) (section 7). Transfus Apheresis Sci 2010;43:107–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Triulzi DJ, Yazer MH. Clinical studies of the effect of blood storage on patient outcomes. Transfus Apheresis Sci 2010;43:95–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saidenberg E, Petraszko T, Semple E, Branch DR. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI): a Canadian blood services research and development symposium. Transfus Med Rev 2010;24:305–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silliman CC. The two-event model of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2006;34:S124–S131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silliman CC, Elzi DJ, Ambruso DR, Musters RJ, Hamiel C, Harbeck RJ, Paterson AJ, Bjornsen AJ, Wyman TH, Kelher M, et al. Lysophosphatidylcholines prime the NADPH oxidase and stimulate multiple neutrophil functions through changes in cytosolic calcium. J Leukoc Biol 2003;73:511–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, Elbourne D, Egger M, Altman DG. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS: definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149:818–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:707–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 1982;38:963–974 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valeri CR, Hirsch NM. Restoration in vivo of erythrocyte adenosine triphosphate, 2,3-diphosphoglycerate, potassium ion, and sodium ion concentrations following the transfusion of acid–citrate–dextrose-stored human red blood cells. J Lab Clin Med 1969;73:722–733 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valtis DJ. Defective gas-transport function of stored red blood-cells. Lancet 1954;266:119–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dern RJ, Brewer GJ, Wiorkowski JJ. Studies on the preservation of human blood. II. The relationship of erythrocyte adenosine triphosphate levels and other in vitro measures to red cell storageability. J Lab Clin Med 1967;69:968–978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raat NJ, Verhoeven AJ, Mik EG, Gouwerok CW, Verhaar R, Goedhart PT, de Korte D, Ince C. The effect of storage time of human red cells on intestinal microcirculatory oxygenation in a rat isovolemic exchange model. Crit Care Med 2005;33:39–45, discussion 238–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett-Guerrero E, Veldman TH, Doctor A, Telen MJ, Ortel TL, Reid TS, Mulherin MA, Zhu H, Buck RD, Califf RM, et al. Evolution of adverse changes in stored RBCs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:17063–17068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds JD, Ahearn GS, Angelo M, Zhang J, Cobb F, Stamler JS._S_-Nitrosohemoglobin deficiency: a mechanism for loss of physiological activity in banked blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:17058–17062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simchon S, Jan KM, Chien S. Influence of reduced red cell deformability on regional blood flow. Am J Physiol 1987;253:H898–H903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marik PE, Sibbald WJ. Effect of stored-blood transfusion on oxygen delivery in patients with sepsis. JAMA 1993;269:3024–3029 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai AG, Cabrales P, Intaglietta M. Microvascular perfusion upon exchange transfusion with stored red blood cells in normovolemic anemic conditions. Transfusion 2004;44:1626–1634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashimoto N, Kawabe T, Imaizumi K, Hara T, Okamoto M, Kojima K, Shimokata K, Hasegawa Y. CD40 plays a crucial role in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;30:808–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gajic O, Rana R, Winters JL, Yilmaz M, Mendez JL, Rickman OB, O'Byrne MM, Evenson LK, Malinchoc M, Degoey SR, et al. Transfusion related acute lung injury in the critically ill: prospective nested case–control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:886–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldman M, Webert KE, Arnold DM, Freedman J, Hannon J, Blajchman MA. Proceedings of a consensus conference: towards an understanding of TRALI. Transfus Med Rev 2005;19:2–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Triulzi DJ. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: current concepts for the clinician. Anesth Analg 2009;108:770–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li G, Rachmale S, Kojicic M, Shahjehan K, Malinchoc M, Kor DJ, Gajic O. Incidence and transfusion risk factors for transfusion-associated circulatory overload among medical intensive care unit patients. Transfusion 2011;51:338–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chin-Yee I, Keeney M, Krueger L, Dietz G, Moses G. Supernatant from stored red cells activates neutrophils. Transfus Med 1998;8:49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silliman CC, Voelkel NF, Allard JD, Elzi DJ, Tuder RM, Johnson JL, Ambruso DR. Plasma and lipids from stored packed red blood cells cause acute lung injury in an animal model. J Clin Invest 1998;101:1458–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiskopf RB, Feiner J, Hopf H, Lieberman J, Finlay HE, Quah C, Kramer JH, Bostrom A, Toy P. Fresh blood and aged stored blood are equally efficacious in immediately reversing anemia-induced brain oxygenation deficits in humans. Anesthesiology 2006;104:911–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walsh TS, McArdle F, McLellan SA, Maciver C, Maginnis M, Prescott RJ, McClelland DB. Does the storage time of transfused red blood cells influence regional or global indexes of tissue oxygenation in anemic critically ill patients? Crit Care Med 2004;32:364–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vamvakas EC, Carven JH. Length of storage of transfused red cells and postoperative morbidity in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Transfusion 2000;40:101–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keller ME, Jean R, LaMorte WW, Millham F, Hirsch E. Effects of age of transfused blood on length of stay in trauma patients: a preliminary report. J Trauma 2002;53:1023–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leal-Noval SR, Jara-Lopez I, Garcia-Garmendia JL, Marin-Niebla A, Herruzo-Aviles A, Camacho-Larana P, Loscertales J. Influence of erythrocyte concentrate storage time on postsurgical morbidity in cardiac surgery patients. Anesthesiology 2003;98:815–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gajic O, Rana R, Mendez JL, Rickman OB, Lymp JF, Hubmayr RD, Moore SB. Acute lung injury after blood transfusion in mechanically ventilated patients. Transfusion 2004;44:1468–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hebert PC, Chin-Yee I, Fergusson D, Blajchman M, Martineau R, Clinch J, Olberg B. A pilot trial evaluating the clinical effects of prolonged storage of red cells. Anesth Analg 2005;100:1433–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van de Watering L; for the Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) Collaborative Pitfalls in the current published observational literature on the effects of red blood cell storage. Transfusion 2011;51:1847–1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hogman CF, Meryman HT. Storage parameters affecting red blood cell survival and function after transfusion. Transfus Med Rev 1999;13:275–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tinmouth A, Chin-Yee I. The clinical consequences of the red cell storage lesion. Transfus Med Rev 2001;15:91–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anniss AM, Sparrow RL. Storage duration and white blood cell content of red blood cell (RBC) products increases adhesion of stored RBCs to endothelium under flow conditions. Transfusion 2006;46:1561–1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luk CS, Gray-Statchuk LA, Cepinkas G, Chin-Yee IH. WBC reduction reduces storage-associated RBC adhesion to human vascular endothelial cells under conditions of continuous flow in vitro. Transfusion 2003;43:151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wadhwa M, Seghatchian MJ, Dilger P, Contreras M, Thorpe R. Cytokine accumulation in stored red cell concentrates: effect of buffy-coat removal and leucoreduction. Transfus Sci 2000;23:7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hogman CF. Storage of blood components. Curr Opin Hematol 1999;6:427–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sparrow RL, Patton KA. Supernatant from stored red blood cell primes inflammatory cells: influence of prestorage white cell reduction. Transfusion 2004;44:722–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chin-Yee IH, Gray-Statchuk L, Milkovich S, Ellis CG. Transfusion of stored red blood cells adhere in the rat microvasculature. Transfusion 2009;49:2304–2310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Disclosures