Mutant TP53 in Duodenal Samples of Pancreatic Juice from Patients with Pancreatic Cancer or High-Grade Dysplasia (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2014 Jun 1.

Published in final edited form as: Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Nov 28;11(6):719–730.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.016

Abstract

Background & Aims

Imaging tests can identify patients with pancreatic neoplastic cysts but not microscopic dysplasia. We investigated wither mutant TP53 can be detected in duodenal samples of secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice, and whether this assay can be used to screen for high-grade dysplasia and invasive pancreatic cancer.

Methods

We determined the prevalence of mutant TP53 in microdissected pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias (PanINs), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), and invasive adenocarcinomas. TP53 mutations were quantified by digital high-resolution melt-curve analysis and sequencing of secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice samples, collected from duodena of 180 subjects enrolled in Cancer of the Pancreas Screening trials; patients were enrolled because of familial and/or inherited predisposition to pancreatic cancer, or as controls.

Results

TP53 mutations were identified in 9.1% of intermediate-grade IPMNs (2/22), 17.8% of PanIN-2 (8/45), 38.1% of high-grade IPMNs (8/21), 47.6% of PanIN-3(10/21), and 75% of invasive pancreatic adenocarcinomas (15/20); no TP53 mutations were found in PanIN-1 lesions or low-grade IPMNs. TP53 mutations were detected in duodenal samples of pancreatic juice from 29/43 patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (67.4% sensitivity; 95% confidence interval, 0.52−0.80) and 4/8 patients with high-grade lesions (PanIN-3 and high-grade IPMN). No TP53 mutations were identified in samples from 58 controls or 55 screened individuals without evidence of advanced lesions.

Conclusion

We detected mutant TP53 in secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice samples collected from duodena of patients with high-grade dysplasia or invasive pancreatic cancer. Tests for mutant TP53 might be developed to improve the diagnosis of and screening for pancreatic cancer and high-grade dyplasia.

clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00438906, NCT00714701)

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasm, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, pancreatic juice, TP53, mutation, secretin, tumor, biomarker, diagnostic, early detection

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States1. Most patients with pancreatic ductal carcinoma are diagnosed with advanced disease. Patients who present with early-stage disease have the best outcome, but surgery is only an option for ~15% of patients with pancreatic cancer1. Early detection is considered potentially one of the most effective approaches to improving the prognosis of this dismal disease.

Effective early detection necessitates detecting potentially curable lesions before they become symptomatic such as subcentimeter invasive cancers and precursors with high-grade dysplasia2. The commonest precursors to pancreatic adenocarcinoma are PanINs. PanINs are microscopic lesions (by definition <5mm diameter); IPMNs are larger cystic pancreatic precursor neoplasms3 with an estimated prevalence of ~2% of older adults4. PanINs and IPMNs are generally asymptomatic and are only identified incidentally or by screening.

Screening is justifiable only when offered to individuals at sufficient risk of developing pancreatic cancer and when the screening test is safe and effective. An ideal screening test would be a highly accurate blood test; however, no blood test has been shown to be as accurate as pancreatic imaging tests (CT, EUS) for diagnosing symptomatic pancreatic cancers, never mind small asymptomatic cancers and precursor neoplasms.

Screening protocols for individuals with a strong family history of pancreatic cancer utilize pancreatic imaging tests (usually EUS and/or MRI/MRCP)5–12. Individuals at significantly increased risk can be identified based on their family history of the disease, but we still lack an effective screening test to offer these individuals13. EUS and MRI/MRCP are very effective for identifying small pancreatic cysts5, but PanINs are generally too small to be identified by these tests14; they are only identified after histological examination of resected pancreata. Low-grade PanIN-1 lesions are prevalent in older adults but PanIN-3 lesions (high-grade dysplasia) are usually found in pancreata of patients with invasive pancreatic cancer and in subjects undergoing pancreatic screening15, 16. The inability to identify PanINs preoperatively highlights the need for novel diagnostic approaches to identify PanINs. One promising approach is to analyze pancreatic juice for mutations arising from pancreatic neoplasms. Markers of pancreatic cancer in ductal pancreatic juice collected during ERCP has been studied17, 18 , but ERCP is too invasive to employ for pancreatic screening. We recently reported on the diagnostic potential of secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice samples collected from the duodenum during upper endoscopy19. We found that GNAS mutations, a highly specific marker of IPMNs, were reliably detected in these samples in subjects with IPMNs and diminutive cysts (<5mm), suggesting that pancreatic juice is a reliable sample for detecting molecular alterations in the pancreatic ductal system19.

Useful markers of pancreatic neoplasia need to accurately distinguish early invasive pancreatic cancers and high-grade dysplasia (PanIN-3 and IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia) from lesions with low-grade dysplasia. Mutant TP53 may be one such marker. It is mutated in ~75% of invasive pancreatic cancers20, 21, with a similar prevalence in familial and sporadic pancreatic cancers21, 22, and immunohistochemical studies suggest TP53 mutations occur late in the progression of PanIN lesions23. In contrast, other genes commonly mutated in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, KRAS, p16 and SMAD4, do not have these diagnostic characteristics: KRAS mutations are present in >90% of PanIN-1 lesions24, and are commonly detected in the pancreatic juice of controls18,24. P16 mutations are thought to also arise throughout PanIN development so these mutations may not distinguish low-grade from high-grade PanINs. Genetic inactivation of SMAD4 is thought to be specific for PanIN-3 and invasive cancer25, but SMAD4 is commonly inactivated by homozygous deletion and such alterations have only been detected in secondary fluids when the deletion has been first characterized in the primary cancer26.

In this study, we determined the prevalence of TP53 mutations in PanIN and IPMNs, and used digital high-resolution melt-curve analysis (digital-HRM) and sequencing to measure TP53 mutation concentrations in duodenal collections of pancreatic juice of individuals undergoing pancreatic evaluation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All elements of this investigation have been approved by The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All authors had access to the study data and had reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Patients and specimens

Pancreatic juice samples and subject data for this study were obtained from 180 participants enrolled in the CAPS2, CAPS3 and CAPS4 clinical trials5, 9 (clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00438906, NCT00714701). Subjects enrolled for screening were asymptomatic with either (i) a strong family history of pancreatic cancer (at least 2 affected blood relatives with pancreatic cancer related by first-degree); the eligibility age in CAPS4 was 50–80 years or 10 years younger than the youngest pancreatic cancer in the kindred, (ii) germline mutation carriers (BRCA2, p16, BRCA1, HNPCC genes) with a family history of pancreatic cancer or (iii) Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Disease controls undergoing pancreatic evaluation were also enrolled to evaluate pancreatic juice markers, and we included subjects from CAPS2–4 to have sufficient disease controls and adequate follow-up subsequent to pancreatic juice collections to identify prospective cancers. See Supplemental Methods for further details.

Pancreatic juice secretion was stimulated by infusing intravenous human synthetic secretin (0.2 ug/kg over one minute): 10–20mls of juice was then collected from the duodenal lumen for ~5 minutes by suctioning fluid through the echoendoscope channel. Secretin was provided for CAPS3 and CAPS4 (ChiRhoClin Inc, Burtonsville, Maryland), and CAPS2 (Repligen Corp., Mass). Juice aliquots (10–20) were stored without additional processing at −80°C prior to use. Extracted DNA was quantified by real-time PCR19.

Laser capture microdissection

PanINs, IPMNs and normal duct samples identified during intra-operative frozen section analysis of resected pancreata by RHH (from 2007–2010) were selected for TP53 analysis as previously described24. For comparison, we analyzed frozen sections of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (see table 1 and Supplemental Methods).

Table 1.

Prevalence of TP53 mutations in resected fresh-frozen tissue samples of PanINs, IPMNs and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas

| Patient# | Pathological grade | N | TP53 mutation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exon 5 | Exon 6 | Exon 7 | Exon 8 | Overall | |||||||

| Normal duct | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | ||||

| IPMN | Low grade dysplasia | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | ||||

| 47 | Intermediate gradedysplasia | 22 | 1 | 12419 G>C; K164N | 1 | 12669 A>G; E221G | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.1%) | ||

| High grade dysplasia | 21 | 3 | 12430 A>C; H169P12451 G>A; R175H12463 A>C; H179P | 2 | 12607 T>A; N200K12617 G>A; E204K | 1 | 13251 G>T; G226C | 2 | 13765 C>T; R283C13787 G>C; R290P | 8 (38.1%) | |

| PanIN | PanIN-1A | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | ||||

| PanIN-1B | 52 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | |||||

| 89 | PanIN-2 | 45 | 2 | 12390 A>C; T155P12463 A>C; H179P | 2 | 12633 G deletion12614 G>A; V203M | 1 | 13317 C>T; R248W | 3 | 13735 C>T; R273C13738 G>T; V274F13779 T deletion | 8 (17.8%) |

| PanIN-3 | 21 | 3 | 12375 A>T; T144S12390 A>C; T155P12453 T>A; C176S | 3 | 12633 G deletion12586 T>A; H193Q12593 C>T;R196stop | 2 | 13286 G>A; M237I13320 A>G; R249G | 2 | 13736 G>A; R273H13779 T deletion | 10 (47.6%) | |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | 20 | 20 | 5 | 12337 T>C; L137P12375 A>T; T144S12402 G>A; A159T12451 G>A; R175H12463 A>G; H179R | 3 | 12591 C>T;I195T12614 G>A; V203M12639 C>T; T211I | 3 | 13257 G deletion13273 A>C; H233P13317 C>T; R248W | 5 | 13721 A>T; N268I13726 T>A; A270I13735 C>T; R273C13762 C>T; R282W13777 G>T;E295stop | 15 (75.0%) |

High-resolution melt-curve analysis

To evaluate DNA from PanIN, IPMN and ductal adenocarcinoma tissues for mutations, HRM was performed in triplicate as previously described24. We evaluated the limit of detection and accuracy of digital-HRM (Figure S1).

For juice analysis, digital-HRM analysis was employed and assays were almost always performed blinded to the final diagnosis. In each 96-well plate, 900 genome equivalents of pancreatic juice DNA were dispensed into 90 wells (10 genome equivalents per well); five wells had wild-type DNA, one had water. Juice DNA was consistently amplified (88–90 wells); no juice samples were excluded for poor DNA quality. Primers and PCR conditions are listed in Table S1. TP53 exons 5–8 were analyzed (almost all TP53 mutations occur in these exons). Melt-curve analysis was performed as described24.

Sanger sequencing and pyrosequencing

PCR products were used as templates for Sanger sequencing and mutations identified in PCR products by digital-HRM and Sanger were confirmed by pyrosequencing24. Sequencing was performed on at least three representative digital-HRM-positive wells per juice sample, and one HRM-wild-type and HRM-negative control well. To ensure assay specificity, a juice sample was only deemed as having a mutation when the same mutation was identified in two or more PCRs by both Sanger and pyrosequencing. The number of mutation-positive PCR products confirmed by sequencing was defined as “the mutation score” for a juice sample.

We next analyzed pancreatic juice samples collected from the operating room of five patients with known TP53 mutations in the primary pancreatic cancer. In all cases, the same TP53 mutations of the cancer were detected in the juice samples by Sanger sequencing of HRM-positive wells (Figure S2, Table S2).

Statistical analysis

Median mutation scores between patient groups were compared by Mann-Whitney’s U test. Chisquare was used to compare associations between TP53 mutational status and clinical factors. ANOVA was used to evaluate associations between clinical factors and positive mutation scores. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS, IL). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Prevalence of TP53 mutations in PanINs, IPMNs and ductal adenocarcinomas

TP53 mutations were detected in 9.1% of intermediate-grade IPMNs, 17.8% of intermediate-grade PanINs (PanIN-2), 38.1% of high-grade IPMNs, 47.6% of PanIN-3, and 75% of 20 invasive ductal adenocarcinomas (one cancer had two mutations)(Table 1). No TP53 mutations were detected in low-grade PanINs (PanIN-1) or IPMNs.

Detection of mutant TP53 in duodenal collections of pancreatic juice

We first evaluated the limit-of-detection of our digital-HRM assay. Mutant TP53 could reliably detect 0.1–10% concentrations of mutant-to-wild-type DNA (Figure S1).

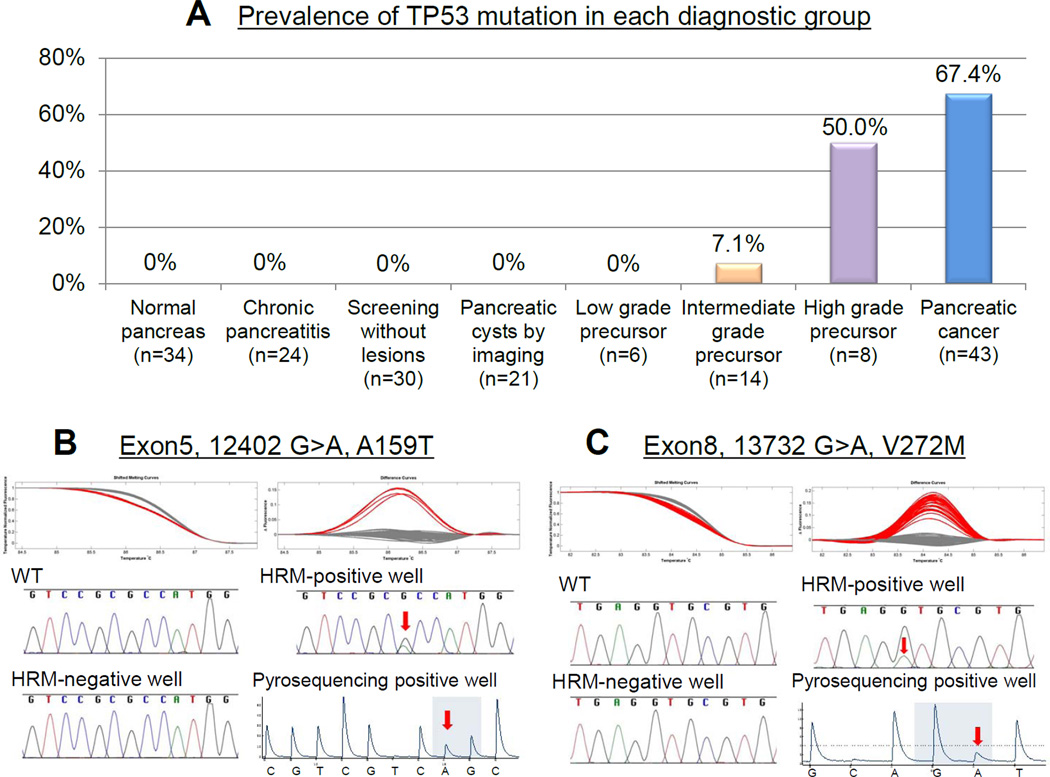

We next employed digital-HRM to detect TP53 mutations in duodenal collections of secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice samples during EUS from CAPS study subjects. TP53 mutations were detected by digital-HRM in secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice samples of 29/43 patients with pancreatic cancer (sensitivity 67.4%, Figure 1A). For all juice samples, TP53 mutations identified in HRM-positive PCR wells were confirmed by both Sanger and pyrosequencing. Two individuals with pancreatic cancer had 2 different TP53 mutations identified in their juice sample (see Figure 1 for representative results). There was no significant association between TP53 status and clinicopathological factors or outcome. Larger tumor size (≥3cm vs. <3cm) was associated with higher juice mutation score (_P_=0.0354, Table S3), but there was no significant correlation overall between tumor size and mutation score (r=0.16, p=0.065).

Figure 1.

(A) Prevalence of TP53 mutation by diagnostic group. (B, C) Shifted melt curves, difference curves, and Sanger sequencing of digital-HRM-positive PCRs from juice samples from subjects with pancreatic cancer; Arrows indicate mutations. (B) Case 40 (C) Case 29 (Table 2).

No TP53 mutations were detected in juice samples of any subjects with normal pancreata (including subjects undergoing screening) (n=64), or with chronic pancreatitis (n=24)(Figure 1A).

Detection of mutant TP53 in pancreatic juice prior to a pancreatic cancer diagnosis

One individual with pancreatic cancer had been enrolled in CAPS4 for screening purposes. He had undergone baseline screening 13 months prior to his pancreatic cancer diagnosis. At baseline screening, he was asymptomatic with no mass either by EUS or MRI/MRCP. The only detected abnormalities were two subcentimeter cysts in the pancreatic head and body. There was no change found at follow-up EUS 6 months prior to diagnosis. At his next surveillance visit, EUS and MRI/MRCP again found the cysts were stable, but a new mass lesion was identified in the pancreatic tail and FNA confirmed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. A distal pancreatectomy was performed. His pancreatic juice collected from the duodenum during baseline EUS (analyzed after the cancer diagnosis) contained a TP53 mutation (exon 7 13318G>A, R248Q, mutation score 4). This TP53 mutation was also present in his endoscopic juice sample obtained at his diagnostic EUS (mutation score 17), and in his primary pancreatic cancer. He did not have juice collected 6 months prior to diagnosis.

We know of no other pancreatic cancers that have developed in the screening group since their juice analysis (median follow-up, 36.4/15 months, range, 6.2–49.3 months).

Pancreatic juice TP53 mutations in subjects with precursor lesions

We next examined secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice samples from 49 individuals with evidence of pancreatic precursor neoplasms. These individuals had undergone pancreatic evaluation either for screening (n=25), or for suspected IPMN identified incidentally (n=24) and included subjects who underwent pancreatic resection after pancreatic evaluation (n=28)(see Table 3) to enable us to compare pancreatic juice results to the pathology of the resected pancreata. TP53 mutations were detected in endoscopic duodenal collections of pancreatic juice of four (50%) of 8 individuals whose most advanced pathology was high-grade dysplasia (PanIN-3 and/or high-grade IPMN) and in one (6.7%) of 15 individuals whose highest grade pathology was intermediate-grade dysplasia (PanIN-2 or in IPMN), and in none of 5 individuals with only low-grade dysplasia, or in any of 21 subjects undergoing surveillance for suspected IPMNs (Figure 1A)(median (largest) cyst size, 14.0 (5–28 mm), median number, 2.8 (range 1–8).

Table 3.

TP53 mutation analysis of duodenal collections of pancreatic juice of 28 subjects with resected pancreatic precursor neoplasms (IPMNs and PanINs)

| Gender / Age, Risk | Preoperative imaging | Surgery | Final pathologic diagnois | TP53 in pancreatic juice | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPS | Contrast MRI or CT | EUS | Procedure /Year | Indication forsurgery | Highestgrade | Additional information | Status | Mutscore | Exon | Mut | |

| 1 | Female / 77,2 FDR, CAPS2 | CT;No evidence of pancreaticmass | Communicating cyst (head, 9mm), focal echogenicthickened wall (6mm) Dilated MPD; head, 4.7mm,Dx; BD-IPMN | Whipple/ 2005 | Pancreatic cyst | PanIN3 | Multifocal PanIN1–3,BD-IPMN low grade; 6mm | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 2 | Female / 72,1 FDR, 2 SDR,CAPS 2 | MRI; Dilated tail MPD | Focally dilated MPD cystic appearing (tail,11mm), focal hypoechoic thickened wall (4mm),Dx; IPMN | Distal panc/ 2004 | IPMN MPD | PanIN3 | 2 BD-IPMN 6, 4mmMultifocal PanINs includingseveral foci of PanIN3 | Mutant | 4 | 7 | 13357G>AS261N |

| 3 | Female / 66,2 FDR, CAPS3 | MRI;2 communicatingcysts (body 1.1–1.4cm)Dx: BD-IPMN | 6 communicating cysts (5–12mm head, body, tail),1 cyst with mural nodule, 1 solid mass 7mm, Dx:BD-IPMNs, PNET | Total panc/ 2007 | Pancreatic cyst | PanIN3 | 3 BD-IPMN int-grade; 6mm – 10mm,multifocal PanIN1–3, 5 well differentiatedPNET; 2–15mm | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 4 | Female / 58,BRCA2 mutant,CAPS3 | MRI; 2 communicatingcysts(tail -8mm) | 2 communicating cysts (body, tail, 2–8mm),Dilated MPD; body, tailDx; BD-IPMN | Distal panc/ 2009 | Pancreatic cyst | PanIN3 | Multifocal PanIN1–3,IPMN low grade; 6mm | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 5 | Female / 75,1 FDR,2SDR,CAPS4 | MRI;2 communicatingcysts (body 3–5mm)Dx: BD-IPMN | 2 cysts (head, 3–5mm), Dilated MPD; echogenic,body, 3.7mmDx; BD-IPMN, MPD stricture | Whipple/ 2009 | MPD stricture | PanIN3 | Multifocal PanINs; PanIN1–3,PanIN3 involving MPD adjacent to MPDstricture | Mutant | 6 | 5 | 12450C>T,R175C |

| 6 | Female / 46,PJS, CAPS2 | MRI; Cystic dilation ofbranch ducts | 3 communicating cysts (body, tail, 4–7mm),Dilated MPD; body, tail, 5mmDx; BD-IPMN | Distal panc/ 2007 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN; | IPMN high grade; 10mm, IPMN lowgrade; 5mm,6 PanINs; PanIN1–2 | Mutant | 3 | 6 | 12569C>A,L188M |

| 7 | Male / 74,Control, CAPS3 | CT;Cystic mass (head 53mm) | Cystic mass (head, 50mm) polypoid echogenicthickened wall (21mm) + septae Sub cm cysts(body), Dx; IPMN | Whipple/ 2009 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN; | IPMN high grade; 50mm,PanIN2 | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 8 | Male / 49,Control, CAPS4 | CT; Pancreatic cyst(uncinate 17mm)Dx: BD-IPMN | Pancreatic cyst (uncinate, 15mm) micromacrocystic, Dx; BD-IPMN | Whipple/ 2010 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN; | MPD-IPMN high grade; 15mm | Mutant | 3 | 6 | 12671C>A,P222T |

| 9 | Male / 57,Control, CAPS3 | CT;Cystic mass (body 17mm) | Complex septated cyst (body, 16mm) 8mm muralnodule, 6mm cyst (head),Dilated MPD; body,3.8mm Dx; BD-IPMN | Distal panc/ 2009 | Pancreatic cyst | PanIN2 | Focal PanIN2,Serous cystadenoma | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 10 | Male / 63,2 FDR, CAPS3 | MRI; No evidenceof pancreatic mass | Hypoechoic mass (tail, 12mm),Dx; pancreatic mass | Distal panc/ 2010 | Pancreaticmass | PanIN2 | Multifocal PanIN;PanIN1-2,lobulocentric atrophy | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 11 | Female / 57,Control, CAPS3 | CT;Cystic mass (body 24mm) | 2 cysts (head, body, 8–20mm)with thick septa, Dx;BD-IPMN or MCN | Distal panc./ 2007 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN; | BD-IPMN int-grade; 16mm,PanIN1 | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 12 | Male / 65Control, CAPS3 | MRI; Multiple cysts(largest head, 27mm)Dx: BD-IPMN | 12 cysts (head, body, tail, largest 27mm,communicating) Dilated MPDDx; multiple BD-IPMN | Whipple/ 2008 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN;PanIN-2 | Multiple BD-IPMN int-grade; largest size30mm,PanIN1–2 | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 13 | Female / 66Control, CAPS3 | MRI; Multiple commun-icating cysts (largest20mm) Dx: BD-IPMN | 8 communicating cysts (head, body, -31mm) withmultiple septa,Dx; multiple BD-IPMN | Whipple/ 2009 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN; | BD-IPMN int-grade; 60mm | Mutant | 2 | 8 | 13741T>C,C275R |

| 14 | Female / 66Control, CAPS3 | CT; Dilated CBD | CBD dilation (13mm) with polypoid, hypoechoictissue, Mildly dilated MPD | Whipple/ 2009 | CBD dilation | IPMN;PanIN2 | BD-IPMN int-grade; 6mm,Multifocal PanIN2 | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 15 | Female / 62Control, CAPS4 | CT; 4 Cysts (head, body,-10mm), Dx: IPMN | 6 cysts (body, tail) largest (body) 13mm,irregular, septated. Dx; IPMNs | Distal panc/ 2003 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN;PanIN2 | MPD-IPMN int-grade; 15mm, MultifocalPanIN1–2 | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 16 | Male / 65,2 FDR CAPS4 | MRI; Multiple cysts(largest body, 28mm)Dx: IPMN | Multiple cysts throughout pancreas(largest 28mmbody), Dx; IPMNs | Distal panc/ 2010 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN;PanIN2 | BD-IPMN int-grade; 15mm, MultifocalPanIN2 | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 17 | Male / 65,1 FDR,2 SDR,CAPS4 | MRI; 2 communicatingcysts, head 14–17mm,Dx; IPMN | 2 cysts (head 19mm septated with 5mm muralnodule, head 10mm) Dx; IPMNs | Whipple/ 2008 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN; | BD-IPMN int-grade; 15mm | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 18 | Male / 51,1 FDR,2 SDR,CAPS 2 | MRI; Solid pancreatic mass(tail, 5mm) | Chronic pancreatitis,no pancreatic mass | Distal panc/ 2006 | Pancreaticmass | PanIN2 | , Multifocal PanIN2,PNET 5mm | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 19 | Male / 77,1 FDR,2 SDR,CAPS 2 | CT; | Cystic dilation of MPD (head, 11mm)Dx; IPMN | Whipple/ 2004 | Pancreatic cyst | PanIN2 | Multifocal PanIN1–2 | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 20 | Male / 60,1 FDR,2 SDR,CAPS 4 | MRI; Pancreatic cyst (head,4mm) Dx; IPMN | Periampullary hypoechoic mass 13mmDx; PNET | Whipple/ 2010 | Periampu-llary mass | PanIN2 | , Multifocal PanIN2,2 islet cell tumors; 15mm, 12mm | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 21 | Female / 78,1 FDR,2 SDR,CAPS 4 | MRI; 3 communicatingcysts (head, body, tail 4–10mm) | Multiple cysts (body, tail, largest 6mm)Dx; IPMNs | Distal panc/ 2010 | Pancreatic cyst | PanIN2 | Multifocal PanIN-2 associatedlobulocentric atrophy,4 incipient IPMNs low-grade; 4mm | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 22 | Female / 61,2 FDR, CAPS4 | MRI; Communicating cyst(tail, 4mm)Dx; IPMN | Hypoechoic solid mass (tail, 8mm)Dx; PNET | Distal panc/ 2010 | Pancreaticmass | PanIN2 | Multifocal PanIN-2 associatedlobulocentric atrophy | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 23 | Male / 48Control, CAPS2 | CT; Pancreatic cyst 15mm(uncinate) Dx: BD-IPMN | 2 cysts (head) largest 18mm increasing size. MPDdilated, echogenic, Dx; BD-IPMN | Whipple/ 2004 | Pancreatic cyst | PanIN2 | Multifocal PanIN1–2, 2 BD-IPMN lowgrade; 10mm 15mm | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 24 | Male / 48,1 FDR,2 SDR,CAPS 2 | MRI, CT; No pancreaticmass | Cystic dilation of MPD (head, 14mm)Dx; IPMN | Whipple/ 2004 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN;low-gradePanIN1B | BD-IPMN low-grade; 12mm,Focal PanIN1B | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 25 | Male / 65,1 FDR,2 SDR,CAPS 4 | MRI; 2 communicatingcyst (head 24mm, tail18mm) Dx; BD-IPMN | 2 cysts (head 28mm septated, body 9mm)Dx; BD-IPMNs | Distal panc/ 2009 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN;low-grade | BD-IPMN low-grade; 20mm | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 26 | Female / 78Control, CAPS3 | MRI; Communicating cyst(head,13mm)Dx: BD-IPMN | A communicating cyst (head, 8mm)Dx; BD-IPMN | Whipple/ 2008 | Pancreatic cyst | IPMN; | BD-IPMN low grade; 5mm | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 27 | Male / 56,Control, CAPS4 | CT;Dilated CBD (17mm) | CBD dilation, no massDx; Dilated CBD | Whipple/ 2010 | CBD dilation | PanIN1B | Pancreas with duct ectasia and focalPanIN1B | Wildtype | 0 | ||

| 28 | Male / 45Control, CAPS4 | MRI; Multilocular mass(tail, 57mm)Dx; serous cystadenoma | A cystic mass (tail, 50mm) consisted of soft tissueand tiny cystic compartmentsDx; serous cystadenoma | Distal panc/ 2009 | Pancreatic cyst | PanIN1A | Focal PanIN1A,Serous cystadenoma; 50mm | Wildtype | 0 |

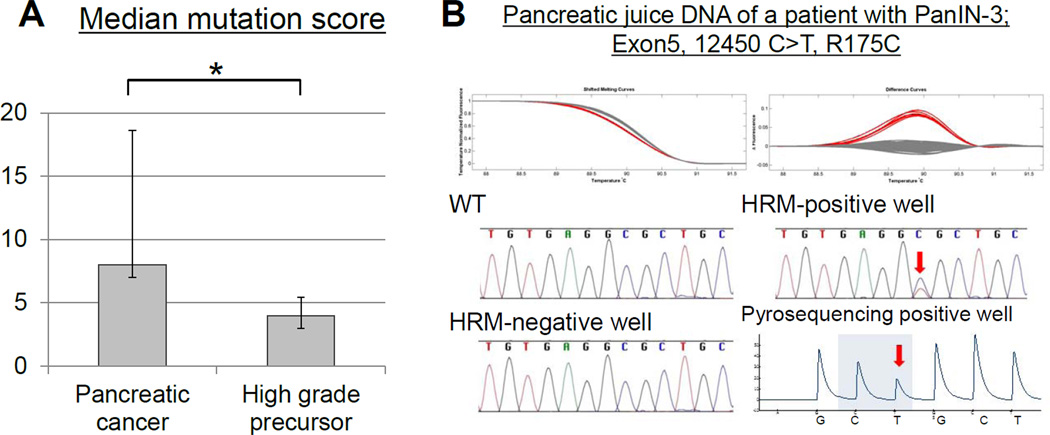

The mutant TP53 mutation score in pancreatic juice was significantly lower in subjects without invasive cancer than in those who had invasive pancreatic cancer (P=0.0191, Figure 2A). Representative examples of melt-curves and sequencing are shown in Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Mutant TP53 juice concentrations (mean mutation score) (Y-axis) from subjects with pancreatic cancer and high-grade precursor lesions (x-axis) *_P_=0.0191. (B) TP53 mutation detected in a pancreatic juice sample from a subject with PanIN-3(Case 4, Table 3). Shifted melt curves, difference curves and sequencing of digital-HRM-PCRs. Arrows indicate mutations.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that mutant TP53 detected in duodenal collections of secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice may provide evidence that the pancreas contains either microscopic PanIN-3 IPMN with high-grade dysplasia, or invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mutant TP53 was detected in the pancreatic juice of only 1 of 102 individuals not known to have high-grade dysplasia, and that was a patient with a 6cm IPMN with intermediate-grade dysplasia. The prevalence of mutant TP53 detected in the duodenal juice collections of patients with pancreatic cancers (67.4%) is similar to its prevalence in primary resected pancreatic cancers (~75%)24, 25 which suggests that mutant DNA arising from a patient’s pancreatic cancer can generally be measured in their duodenal collections of pancreatic juice.

Although TP53 mutation concentrations were significantly higher in subjects with larger compared to smaller cancers and in those with PanIN-3/IPMN with high-grade dysplasia, there was no correlation between tumor size and juice mutation concentrations. This is not surprising. Juice mutation concentrations are based on normal DNA concentrations which probably vary considerably in juice. Pancreatic cancer tumor cellularity also varies considerably; hence tumor size provides only approximate estimates of cancer cell numbers (and DNA). Finally, ductal obstruction may influence tumor DNA amounts released into pancreatic juice.

Importantly, TP53 mutations were not detected in the juice samples of any of the patients in the disease control groups (n=54), screened individuals with normal pancreata (n=30) or in individuals who were undergoing surveillance for small pancreatic cysts identified incidentally or through screening (n=21). Patient samples analyzed in this study were representative of our CAPS study population and included subjects who had subtle EUS changes suggestive of PanIN16. Although we did not identify TP53 mutations in subjects with chronic pancreatitis, prior studies using older technologies have reported finding TP53 mutations in ERCP-collected juice samples of a small percentage (<10%) of individuals with chronic pancreatitis18,19,31–33. These older studies did not employ the more accurate DNA sequencing methods used in this study to identify mutations, therefore additional studies are needed in order to have better estimates of the prevalence of TP53 mutations in juice samples from patients with chronic pancreatitis17, 18, 27–29.

Since an important goal of pancreatic juice research is to determine if biomarkers could be used to accurately find high-grade dysplasia or small invasive cancers not visible by pancreatic imaging tests, the results in patients with evidence of high-grade dysplasia are informative. In our study, mutant TP53 was detected in the juice samples of 4 of 8 individuals whose highest grade lesion was high-grade dysplasia, including 2 of 5 individuals whose highest lesion was a PanIN-3. One of these two individuals also had an IPMN with low-grade dysplasia. Since we did not detect mutant TP53 in any IPMNs with low-grade dysplasia, the pancreatic juice TP53 mutation detected in this patient likely arose from their PanIN-3 lesion. Since PanINs are not typically detectable by pancreatic imaging tests, the ability of TP53 measurements to find evidence of microscopic high-grade dysplasia highlights the potential of pancreatic juice analysis to complement pancreatic imaging for individuals undergoing screening.

Our study also showed that the detection rate of mutant TP53 in the pancreatic juice of patients with precursor neoplasms is concordant with the presence of mutant TP53 we identified in resected PanIN and IPMN specimens. TP53 mutations were only detected in PanINs and IPMNs with intermediate-grade (15%) and high-grade dysplasia (43%), not in any low-grade IPMNs or PanIN-1. These figures are consistent with prior estimates of TP53 mutation in these lesions determined from immunohistochemical analysis (reviewed in3).

Mutant TP53 was also detected in the juice of 2 of 3 individuals whose highest grade lesion was an IPMN with high-grade dysplasia. This indicates that pancreatic juice analysis has the potential to be useful for identifying high-grade dysplasia within IPMNs. Although clinical guidelines for resecting IPMNs are very helpful for managing asymptomatic patients with pancreatic cysts30, there is a need to determine if molecular markers can be used along with current clinical guidelines to improve the selection of patients needing resection of their IPMN.

A suspected IPMN is the most common indication for pancreatic resection among high-risk individuals undergoing pancreatic screening5–11. In our cohort, concern for undetected PanIN-3 lesions and early invasive cancer was an important consideration when surgery was recommended for patients with lesions identified by screening. Hence, lesions identified in high-risk individuals are often resected before they reach the modified Tanaka criteria used as resection criteria for sporadic IPMNs30.

The limitations of current pancreatic imaging tests were highlighted in the one patient in this study who was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer 13 months after his baseline pancreatic screening. Based on our current understanding of the natural history of early invasive pancreatic cancer31, it is likely this patient had a high-grade precursor or an invasive pancreatic cancer at the time he was initially screened that was below the limit of detection of his baseline and follow-up EUS and MRI. This is not surprising. An early pancreatic cancer may not become visible until it forms a solid 5+ mm diameter mass. At this size, a pancreatic cancer can grow and spread rapidly as evidenced by the presence of this patient’s lymph node metastases at diagnosis. This case highlights the potential of pancreatic juice TP53 measurements to herald the subsequent detection of invasive pancreatic cancer.

Until further evidence is available about its diagnostic utility, it is premature to recommend surgical resection based solely on the detection of mutant TP53 in pancreatic juice. Additional information is needed about the diagnostic accuracy of mutant TP53 in patients undergoing pancreatic evaluation. If additional investigations confirm that mutant TP53 detected in pancreatic juice is an accurate predictor of higher-grade dysplasia or invasive pancreatic cancers such a test would likely have clinical utility, particularly in the high-risk population where the prevalence of precursor neoplasms is high5.

Future research using markers such as TP53 may also shed light on the natural history of precursor lesions with high-grade dysplasia in high-risk individuals. Since the detection of pancreatic juice mutant TP53 could indicate either invasive cancer or intermediate/high-grade dysplasia, particularly for individuals without a suspicious lesion detected by imaging, an important question is whether they should continue to undergo surveillance or be considered for pancreatic resection.

The absence of TP53 mutations does not mean a patient does not have high-grade dysplasia or invasive pancreatic cancer. Therefore, an ideal pancreatic juice test would include markers capable of identifying _TP53_-wild-type lesions, and like mutant TP53, are highly specific for high-grade neoplasia (PanIN-3 and IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia) and early invasive pancreatic cancer.

Some strengths of this study are the large sample size, the multicenter population, including subjects undergoing pancreatic screening, long-term follow-up of patients after screening, and the demonstration that TP53 mutations can be detected in the duodenal collections of pancreatic juice in individuals with PanIN-3 lesions. One limitation of this study is the difficulty identifying specific PanINs as the source of mutations. Since most patients undergoing screening do not undergo resection, we do not have a comprehensive pathological evaluation of their pancreata to identify all their PanIN lesions. Indeed, even when a patient undergoes partial pancreatectomy, PanIN lesions may be present in their remnant pancreata. This is a challenge for all studies evaluating pancreatic juice markers of PanINs.

In conclusion, we find that TP53 mutations detected in secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice are a highly specific indicator of the presence of high-grade dysplasia (in IPMNs and/or PanIN-3) or invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas.

Supplementary Material

01

02

03

Table 2.

TP53 analysis of endoscopic duodenal collections of pancreatic juice from 43 subjects with pancreatic cancer

| Gender | Age | Diagnosticmethod | Tumorlocation | Tumorsize (cm) | Differentiation | UICCstage | TP53 in pancreatic juice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status | Mutationscore | Exon | Mutation | ||||||||

| 1 | Female | 77 | Surgery | Head | 4 | Moderate | T3N1 | Mutant | 8 | 6 | 12628 T>A, D207E |

| 2 | Male | 72 | FNA | Body | 4 | Moderate | T3N0 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 3 | Male | 40 | Surgery | Head | 3 | Poor | T3N1 | Mutant | 36 | 5 | 12451 G>A, R175H |

| 4 | Female | 55 | FNA | Head | 3 | Not recorded | T4N1 | Mutant | 6 | 8 | 13792 A>G, K292E |

| 5 | Female | 79 | FNA | Body | 2.5 | Well | T4N0 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 6 | Female | 65 | FNA | Head | 6 | Not recorded | T3N0 | Mutant | 9 | 8 | 13792 C>T, R282W |

| 7 | Male | 68 | Surgery | Head | 10 | Not recorded | T4N1 | Mutant | 26 | 6 | 12588 T>G. L194R |

| 8 | Female | 55 | Surgery | Head | 2 | Poor | T3N1 | Mutant | 5 | 7 | 13317 C>T, R248W |

| 9 | Male | 72 | FNA | Uncinate | 3.8 | Well | T3N0 | Mutant | 10 | 5 | 12390 A>C, T155P |

| 10 | Male | 55 | Surgery | Head | 2 | Moderate | T3N1 | Mutant | 5 | 6 | 12666 A>G, Y220C |

| 11 | Male | 58 | Surgery | Head | 3 | Not recorded | T3N0 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 12 | Female | 68 | FNA | Body | 1.8 | Poor | T1N0 | Mutant | 3 | 5 | 12449 G>T, R174S |

| 13 | Female | 57 | FNA | Tail | 6.5 | Not recorded | T4N0 | Mutant | 334 | 68 | 12647 C>G, H214D13812 G>T, E298D |

| 14 | Female | 64 | FNA | Head | 4.1 | Not recorded | T3N1 | Mutant | 7 | 7 | 13317 C>T, R248W |

| 15 | Female | 68 | Surgery | Head | 2 | Moderate | T3N1 | Mutant | 5 | 5 | 12399 C>T, R158C |

| 16 | Female | 69 | Surgery | Body | 1.5 | Not recorded | T1N0 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 17 | Female | 63 | FNA | Head | 2.3 | Not recorded | T3N0 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 18 | Male | 75 | FNA | Head | 4.5 | Not recorded | T3N1 | Mutant | 4 | 8 | 13786 C>T, R290C |

| 19 | Female | 69 | FNA | Tail | 3.5 | Well | T4N1 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 20 | Female | 56 | FNA | Head | 3.5 | Not recorded | T3N0 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 21 | Male | 52 | FNA | Head | 1.7 | Not recorded | T3N0 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 22 | Male | 67 | FNA | Head | 3.3 | Not recorded | T3N1 | Mutant | 6 | 6 | 12609 T deletion |

| 23 | Female | 61 | Surgery | Head | 3 | Poor | T2N0 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 24 | Female | 56 | FNA | Body | 4.5 | Not recorded | T4N1 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 25 | Female | 55 | Surgery | Uncinate | 3 | Poor | T3N1 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 26 | Male | 70 | FNA | Head | 3.1 | Not recorded | T2N0 | Mutant | 5 | 8 | 13735 C>T R273C |

| 27 | Male | 61 | Surgery | Head | 4 | Moderate | T3N0 | Mutant | 86 | 78 | 13299 T>A, C242S13792 C>T, R282W |

| 28 | Female | 74 | Surgery | Head | 3.5 | Moderate | T3N1 | Mutant | 19 | 5 | 12417 A deletion |

| 29 | Male | 75 | Surgery | Head | 3.5 | Moderate | T3N1 | Mutant | 43 | 8 | 13732 G>A, V272M |

| 30 | Female | 61 | FNA | Body | 2.4 | Not recorded | T2N0 | Mutant | 12 | 6 | 12645 G>T, R213L |

| 31 | Male | 71 | Surgery | Head | 2.1 | Not recorded | T3N0 | Mutant | 12 | 5 | 12436 C>T, T170M |

| 32 | Male | 76 | FNA | Uncinate | 4.4 | Not recorded | T2N0 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 33 | Male | 64 | FNA | Tail | 2.1 | Not recorded | T2N0 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 34 | Male | 64 | FNA | Tail | 1.8 | Not recorded | T1N0 | Mutant | 7 | 7 | 13300 G>A, C242Y |

| 35 | Male | 80 | Surgery | Head | 2.5 | Poor | T4N1 | Mutant | 18 | 7 | 13276 A>G, Y234C |

| 36 | Female | 78 | Surgery | Head | 3.5 | Moderate | T2N1 | Mutant | 25 | 7 | 13300 G>A, C242Y |

| 37 | Female | 59 | Surgery | Body | 2.5 | Moderate | T2N0 | Mutant | 8 | 5 | 12393 C>T, R156C |

| 38 | Male | 57 | Surgery | Tail | 2.8 | Poor | T2N1 | Mutant | 4 | 7 | 13318 G>A, R248Q |

| 39 | Male | 53 | FNA | Head | 3.5 | Moderate | T3N0 | Mutant | 9 | 6 | 12662 C>T, P219S |

| 40 | Female | 73 | Surgery | Head | 2.5 | Not recorded | T2N1 | Mutant | 5 | 5 | 12402 G>A, A159T |

| 41 | Female | 79 | Surgery | Body | 2.5 | Moderate | T2N0 | Mutant | 5 | 7 | 13312 T>C, M246T |

| 42 | Male | 73 | FNA | Head | 2.9 | Not recorded | T4N1 | Wild type | 0 | ||

| 43 | Male | 62 | FNA | Head | 2.5 | Not recorded | T2N1 | Mutant | 11 | 5 | 12424 C>T, S166L |

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported by NIH grants (CA62924, R01CA120432, and RC2CA148376), the Lustgarten Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research, the Jimmy V Foundation, Susan Wojcicki and Dennis Troper, the Michael Rolfe Foundation, the Alan Graff Foundation, Karp Family H.H. Metals, Inc. Fund for Cancer Research, Michael Hooven and Susan Spies, Hugh and Rachel Victor.

Material Support: ChiRhoClin, Repligen (secretin).

Abbreviations

IPMN

intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

PanIN

pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia

GNAS

Guanine Nucleotide-Binding Protein, Alpha-Stimulating

EUS

endoscopic ultrasonography

CT

computed tomography

MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

MRCP

magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

ERCP

endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

FNA

fine-needle aspiration

HRM

high-resolution melt-curve analysis

PCR

polymerase chain reaction

CAPS

Cancer of the Pancreas Screening

LCM

Laser Capture Microdissection

FDR

first-degree relative

s.d

standard deviation

HNPCC

hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Drs. Goggins and Hruban have a licensing agreement with Myriad Genetics for the discovery of PALB2 as a pancreatic cancer susceptibility gene. There are no other conflicts of interest for any of the authors. Recombinant secretin was provided for this study by ChiRhoClin, Inc and Repligen. None of companies involved had any part in the design of this study, analysis or interpretation of data or in the writing of this manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data and takes full responsibility for the veracity of the data and statistical analysis.

Author contributions:

Mitsuro Kanda; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript. Yoshihiko Sadakari, Spencer Knight; Michael Borges; Sho Fujiwara; acquisition of data

Mark Topazian, Sapna Syngal, James Farrell, Jeffrey Lee, Ihab Kamel, Anne Marie Lennon; generation of data, revision of the manuscript

Ralph H. Hruban; material support; acquisition and interpretation of data; revision of the manuscript

Marcia Irene Canto; material support; acquisition and interpretation of data; study supervision; revision of the manuscript, obtained funding

Michael Goggins; study concept and design; study supervision; interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; obtained funding

REFERENCES

- 1.Raimondi S, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: an overview. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:699–708. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goggins M. Markers of Pancreatic Cancer: Working Toward Early Detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:635–637. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi C, Hruban RH. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Jong K, Nio CY, Hermans JJ, et al. High Prevalence of Pancreatic Cysts Detected by Screening Magnetic Resonance Imaging Examinations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:806–811. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canto MI, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, et al. Frequent detection of pancreatic lesions in asymptomatic high-risk individuals. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:796–804. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ludwig E, Olson SH, Bayuga S, et al. Feasibility and yield of screening in relatives from familial pancreatic cancer families. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:946–954. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verna EC, Hwang C, Stevens PD, et al. Pancreatic cancer screening in a prospective cohort of high-risk patients: a comprehensive strategy of imaging and genetics. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5028–5037. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langer P, Kann PH, Fendrich V, et al. Five years of prospective screening of high-risk individuals from families with familial pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2009;58:1410–1418. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.171611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canto MI, Goggins M, Hruban RH, et al. Screening for early pancreatic neoplasia in high-risk individuals: a prospective controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:766–781. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canto MI, Goggins M, Yeo CJ, et al. Screening for pancreatic neoplasia in high-risk individuals: an EUS-based approach. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:606–621. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poley JW, Kluijt I, Gouma DJ, et al. The yield of first-time endoscopic ultrasonography in screening individuals at a high risk of developing pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2175–2181. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brentnall T, Bronner M, Byrd D, et al. Early diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic dysplasia in patients with a family history of pancreatic cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:247–255. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-4-199908170-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein AP, Brune KA, Petersen GM, et al. Prospective risk of pancreatic cancer in familial pancreatic cancer kindreds. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2634–2638. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hruban RH, Maitra A, Goggins M. Update on pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2008;1:306–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi C, Klein AP, Goggins M, et al. Increased Prevalence of Precursor Lesions in Familial Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7737–7743. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brune K, Abe T, Canto M, et al. Multifocal neoplastic precursor lesions associated with lobular atrophy of the pancreas in patients having a strong family history of pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1067–1076. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan L, McFaul C, Howes N, et al. Molecular analysis to detect pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in high-risk groups. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:2124–2130. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohr M, Muller P, Mora J, et al. p53 and K-ras mutations in pancreatic juice samples from patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:734–743. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.112711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanda M, Knight S, Topazian M, et al. Mutant GNAS detected in duodenal collections of secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice indicates the presence or emergence of pancreatic cysts. Gut. 2012 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302823. published online Aug 2,2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redston MS, Caldas C, Seymour AB, et al. p53 mutations in pancreatic carcinoma and evidence of common involvement of homocopolymer tracts in DNA microdeletions. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3025–3033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321:1801–1806. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. Epub 2008 Sep 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brune K, Hong SM, Li A, et al. Genetic and epigenetic alterations of familial pancreatic cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3536–3542. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hruban RH, Goggins M, Parsons J, et al. Progression model for pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2969–2972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanda M, Matthaei H, Wu J, et al. Presence of Somatic Mutations in Most Early-Stage Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:730–733. e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.042. Epub 2012 Jan 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilentz RE, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Argani P, et al. Loss of expression of Dpc4 in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: evidence that DPC4 inactivation occurs late in neoplastic progression. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2002–2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leary RJ, Kinde I, Diehl F, et al. Development of personalized tumor biomarkers using massively parallel sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:20ra14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamaguchi Y, Watanabe H, Yrdiran S, et al. Detection of mutations of p53 tumor suppressor gene in pancreatic juice and its application to diagnosis of patients with pancreatic cancer: comparison with K-ras mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1147–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaino M, Kondoh S, Okita S, et al. Detection of K-ras and p53 gene mutations in pancreatic juice for the diagnosis of intraductal papillary mucinous tumors. Pancreas. 1999;18:294–299. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199904000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohtsubo K, Watanabe H, Yao F, et al. Preproenkephalin hypermethylation in the pure pancreatic juice compared with p53 mutation in the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:791–797. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1857-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka M, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haeno H, Gonen M, Davis MB, et al. Computational modeling of pancreatic cancer reveals kinetics of metastasis suggesting optimum treatment strategies. Cell. 2012;148:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

01

02

03