Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity/Expression Related Peer Victimization in Adolescence: A Systematic Review of Associated Psychosocial and Health Outcomes (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2014 Apr 1.

Abstract

This article reviews research on psychosocial and health outcomes associated with peer victimization related to adolescent sexual orientation and gender identity or expression. Using four electronic databases and supplementary methods, we identified 39 relevant studies. These studies were published between 1995 and 2012 and conducted in 12 different countries. The studies were diverse in terms of their approaches to sampling participants, assessing participants’ sexual orientation, operationalizing peer victimization, and with regard to the psychosocial and health outcomes studied in relation to peer victimization. Despite the methodological diversity across studies, there is fairly strong evidence that peer victimization related to sexual orientation and gender identity or expression is associated with a diminished sense of school belonging and higher levels of depressive symptoms; findings regarding the relationship between peer victimization and suicidality have been more mixed. Peer victimization related to sexual orientation and gender identity or expression is also associated with disruptions in educational trajectories, traumatic stress, and alcohol and substance use. Recommendations for future research and interventions are discussed.

Keywords: Sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, peer victimization, adolescence

As bullying has been implicated in several reports about adolescent suicides in the U.S., experiences of sexual minority adolescents at school have received high-profile media attention (Erdely, 2012; Gaga dedicates song to bullied fan, 2011; Glaister, 2010; Henetz, 2012; Iowa paper devotes Page 1 to fight bullying, 2012; Weise, 2010). Schools and other stakeholders are increasingly taking action to enhance safety for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) students (Dooley, 2011; Fletcher & Brody, 2012; Polsky, 2010; Sebelius & Duncan, 2010). It thus seems an appropriate moment to review and integrate the accumulated research literature on peer victimization affecting sexual and gender minority youth.

Peer victimization in general encompasses a variety of negative, aggressive behaviors among children and adolescents; it can take both direct (e.g., insults, hitting or pushing) and indirect forms (e.g., spreading rumors). Bullying is a specific form of peer victimization, occurring repeatedly over time and involving an imbalance of power between bully and victim (Olweus, 2010). Youth victimized by their peers are at risk for poorer psychosocial adjustment (Nansel, Craig, Overpeck, Saluja, & Ruan, 2004; Nansel et al., 2001).

Peer victimization affecting sexual and gender minority youth more specifically has received a good deal of research attention; as noted in a recent report by the U.S. Institute of Medicine, it is the most common topic in the literature on these populations (IOM, 2011). Literature on the peer victimization experiences of sexual and gender minority youth dates back to the late 1980s, and in the intervening years a wide variety of psychosocial and health outcomes related to victimization have been studied (Martin & Hetrick, 1988; Savin-Williams, 1994). In an earlier review, Savin-Williams (1994) examined peer victimization (along with victimization by adults) among LGB adolescents and its relationship to school-related problems, substance use, suicide, and other problems, and concluded that there was strong “suggestive evidence” of an association between victimization and such outcomes despite the lack of social science research addressing causal mechanisms (p. 261).

In this paper, we review the research that has been completed in the two decades since Savin-Williams’ review. We aim to answer the following question: what psychosocial and health outcomes are associated with peer victimization that is a) based on (actual or perceived) sexual orientation or gender identity or expression, or b) directed toward sexual and gender minority adolescents? To address the first part of our question, we reviewed studies that looked at exposure to sexually prejudiced language or victimization based on perceived sexual orientation or gender identity/expression in adolescents; to address the second part of our question, we reviewed studies that focused on peer victimization in samples of sexual and gender minority youth, although not all of these studies specifically assessed peer victimization related to sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. Our goals are to describe, summarize, and evaluate the literature in this area and in so doing, develop informed recommendations for future research and intervention development. We have structured this paper as a narrative review because this approach is best suited to addressing the diversity of psychosocial and health outcomes that have been studied in relation to peer victimization, which has itself been operationalized in a variety of ways. Indeed, the results of the literature review are presented with attention to the methodological diversity of the studies included; implications of this methodological diversity are then discussed.

We have chosen not to focus on the prevalence of peer victimization among sexual minority youth or disparities in their exposure to victimization. Prevalence of peer victimization has been well documented in samples of sexual minority youth, and also in representative samples of adolescents, indicating disproportionate exposures among sexual minorities (e.g., Faulkner & Cranston, 1998; Kosciw, Greytak, Diaz, & Bartkiewicz, 2010). Prevalence has also been the subject of recent meta-analyses. Across 31 studies, the rate of school victimization for LGB individuals was 33% (95% CI: 26–39%; Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012). Results of 26 school-based studies indicated that sexual minority adolescents were, on average, 1.7 times more likely than heterosexual peers to report assault by peers at school (Friedman et al., 2011). Despite these findings and despite the focus of the present review, peer victimization should not be thought of as a normative part of adolescence for sexual and gender minority youth. Some research has actually shown that same-sex- and bisexually-attracted youth are as likely to report low levels of peer victimization as are their heterosexually-attracted counterparts (Busseri, Willoughby, Chalmers, & Bogaert, 2006).

In this manuscript, we will use peer victimization as an umbrella term to encompass the variety of negative behaviors directed toward participants in the reviewed studies by other adolescents. These behaviors primarily included physical, verbal, and sexual victimization and sexual harassment, but also indirect and relational victimization. Because the studies included in our review were diverse with respect to the assessment of participants’ sexual identities, we use the term sexual minority broadly to denote adolescents who may have same-sex attractions, engage in same-sex sexual behaviors, or identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, or questioning. The term gender minority is also used broadly in reference to transgender individuals and to gender non-conforming individuals who do not self-identify as transgender but whose gender identity or expression does not conform to cultural norms for their birth sex. To avoid obscuring important differences between sub-populations (e.g., gay-identified and sexually questioning adolescents) that may have been studied, we will use more precise terms where possible when referring to specific studies. This will also be our practice when referring to those studies that included transgender or gender non-conforming participants. Abbreviations are used as follows: L = lesbian, G = gay, B = bisexual, T = transgender, Q = questioning.

Methods

Search Strategy

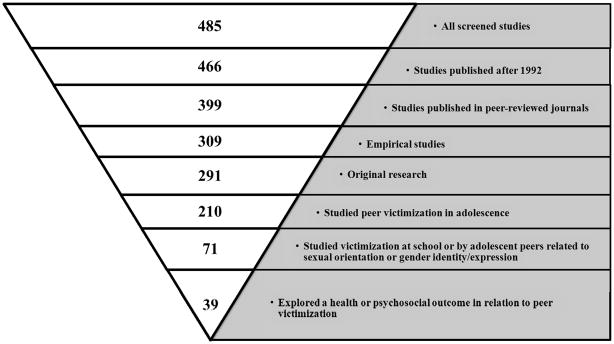

To identify studies for inclusion in this review, we searched the electronic databases ERIC, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science. We used numerous search terms related to peer victimization in combination with terms related to sexual orientation or gender identity/expression and the target population or setting. Additional details regarding the search strategy, including a complete list of search terms, are included in the Appendix. The search was limited to the English-language literature and captured articles published through the first half of 2012. We supplemented the list of articles yielded by the database searches with articles from our own files and those that were referenced by other studies. These efforts produced a list of 485 unique citations.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The first author reviewed the abstracts of all 485 citations to determine which studies met the review’s inclusion criteria. To be included, studies must have 1) been published after 1992; 2) been published in a peer-reviewed journal; 3) been empirically-based; 4) reported original research findings; 5) been conducted among adolescents or focused on adolescent experiences (studies in which adults retrospectively reported on adolescent experiences were included); 6) been concerned with victimization perpetrated by adolescent peers or in school settings; and 7) explored a psychosocial or health outcome in relation to peer victimization. We focused on studies published after 1992 because Savin-Williams (1994) summarized earlier work in this area. We excluded studies that either 1) did not assess the sexual or gender minority status of participants or 2) were not focused on victimization that was related to gender identity/expression or actual or perceived sexual orientation. Fifty articles needed review of the full text before a decision about inclusion or exclusion could be made; these decisions were made by the first author in consultation with a co-author.

Data Extraction

All studies were independently reviewed by two authors and abstracted using a standardized form. The first author reconciled the work of the two reviewers and organized the abstractions into one database that allowed aspects of all included studies to be compared and summarized.

Literature Search Results

Outcomes of applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria to the 485 retrieved articles are presented in Figure 1. In the end, 39 studies were included in the review. These studies were diverse in their research foci and approaches, and key aspects of each study are summarized in Table 1. The majority of reviewed studies were conducted in the U.S. (n = 25); three were conducted in Canada, two in the U.K., and one each was done in Austria, Belgium, Israel, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, and South Africa. A final two studies recruited participants from multiple countries: Canada, New Zealand, and the U.S. (D’Augelli, Pilkington, & Hershberger, 2002) and Australia, Canada, and the U.S. (Josephson & Whiffen, 2007), respectively. As shown in Table 2, several articles were based on common data sources.

Figure 1.

Process of excluding studies from the literature review.

Table 1.

Descriptive Summary of 39 Reviewed Articles

| Study First Author and Publication Date | Year(s) of Data Collection | Countrya | Sample Sizeb | Sexual Minorityc Representation | Sampling Approach | Type(s) of Victimization Assessedd | Attribution for Victimizatione | Outcome(s) Studied in Relation to Peer Victimization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerts (2012) | 2007 | Belgium | 1,745 | 9.6% | Community venues, web-based | V P | SO | Sense of school belonging |

| Birkett (2009) | 2004–2005 | U.S. (MW) | 6,667 | 15.1% | School-based | V P G | SO | Drug use, truancy, depression/suicidality |

| Bontempo (2002) | 1995 | U.S. (NE) | 9,188 | 3.4% | Two-stage cluster | P | Cigarette smoking, alcohol and drug use, sexual risk behavior, suicide attempts | |

| Bos (2008) | 2004 | Netherlands | 866 | 8.5% | School-based | V P G R | Depression, self-esteem, school identification, GPA | |

| Busseri (2008) | N.S. | Canada | 3,876 | 4%f | School-based | P R | Cigarette smoking, alcohol and drug use, sexual activity, delinquent activity, aggression, gambling | |

| Butler (2003) | 1997–2000 | South Africa | 18 | 100% | Snowball with purposive selection | Qualitative study; standard assessments were not used but reports of physical and verbal victimization were elicited. | Impact on coming out process | |

| D’Augelli (2006) | N.S. | U.S. (NE) | 528 | 100% | Community venues, snowball | V P S | SO | PTSD |

| D’Augelli (2002) | N.S. | Canada, U.S., New Zealand | 350 | 100% | Community venues, web-based | V P S | SO | General mental health, traumatic stress, alcohol/drug use, suicidality, internalized homophobia |

| Elze (2002) | 1998 | U.S. (NE) | 169 | 100% | Community venues, snowball | V P S | SO | Internalizing and externalizing problems |

| Espelage (2008) | 2004–2005 | U.S. (MW) | 13,921 | 14.4% | School-based | V P G | SO | Alcohol and marijuana use, depressive and suicidal feelings, perceptions of school climate |

| Felix (2009) | 2002–2003 | U.S. (W) | 70,600 | Sexual minority status not assessed | School-based | V P SH I | SO | Depression, perceptions of school safety, internal assets, grades, truancy |

| Friedman (2006) | N.S. | U.S. | 96 | 100% | Community venues | P | Suicidality | |

| Grossman (2006) | 2000 | U.S. (NE) | 24 | 100% transgender or gender atypical | Community venues | Qualitative study; standard assessments were not used but reports of physical and verbal victimization were elicited. | Mental and physical health risks | |

| Gruber (2007) | N.S. | U.S. (NE) | 235 | 5%g | School-based | V P G R SH | SPL | Self-esteem, mental health, physical health, trauma symptoms, life satisfaction, substance abuse |

| Gruber (2008) | N.S. | U.S. (NE) | 522 | 9% | School-based | V P G R SH | SPL | Self-esteem, mental health, physical health, trauma symptoms, substance abuse |

| Hegna (2007) | N.S. | Norway | 407 | 100% | Community venues, web-based, snowball | Not provided | SO | Lifetime history of suicide attempt |

| Hidaka (2006) | 1999 | Japan | 1025 | 100% | Web-based | G | SO | Lifetime history of suicide attempt |

| Jordan (1997) | N.S. | U.S. (MW) | 34 | 100% | Community venues | P V | SPL | Negative emotional experiences |

| Josephson (2007) | N.S. | Australia, Canada, U.S. | 470 | 100% | Web-based | V P I | Depressive symptoms in adulthood | |

| Kerr (2011) | N.S. | U.S. (S) | 1,252 | Sexual minority status not assessed | School-based | G | SO | Life satisfaction |

| Landolt (2004) | N.S. | Canada | 191 | 100% | Community- based | V G R | Adult attachment anxiety and avoidance | |

| McGuire (2010) | 2003–2005 | U.S. (W) | Study 1: 2,260 | Study 1: 34% (3% transgender) | Gay-Straight Alliance members | Study 1: V | Study 1: GIE | Study 1: Perceived safety at school |

| N.S. | U.S. (W) | Study 2: 36 | Study 2: 100% transgender | Community venues | Study 2: Qualitative study; standard assessments were not used but reports of physical and verbal victimization were elicited. | Study 2: Individual responses to victimization | ||

| Murdock (2005) | N.S. | U.S. (MW) | 101 | 100% (3% transgender) | Community venues, snowball | V P | SO | GPA, school belonging, school discipline problems |

| Pilkington (1995) | N.S. | U.S. | 194 | 100% | Community venues | V P S | SO | Safety fears; other modifications of behavior in response to victimization |

| Pizmony-Levy (2008) | 2004–2005 | Israel | 298 | 100% (2% transsexual) | Community venues, snowball, web-based | V P | SOSPL | Sense of respect from peers, sense of school belonging |

| Plöderl (2010) | 2005 | Austria | 468 | 100% | Web-based | V | SPLGIE | Lifetime history of suicide attempt related to school experience, acceptance at school |

| Poteat (2007) | N.S. | U.S. (MW) | 143 | Sexual minority status not assessed | School-based | V | SPL | Anxiety, depression, sense of school belonging, distress, withdrawal |

| Poteat (2011) | 2008–2009 | U.S. (MW) | 15,923 | 5.8% (includes transgender participants) | School-based | V P G | SO | School belonging, suicidality, grades, truancy, and graduation perceptions |

| Rivers (2001) | 1995–1997 | U.K. | Survey 1: 190Survey 2: 119Interviews: 16 | 100% | Community venues | V P R S I | SPL | Self-harming behavior, depressive/anxious symptoms, self-esteem, internalized homonegativity, possessiveness within relationships |

| Rivers (2004) | N.S. | U.K. | 119 | 100% | Community venues | Not specified | SO | Posttraumatic stress, negative affect, internalized homophobia, sexual behavior |

| Russell (2011) | 2005 | U.S. (W) | 245 | 100% (8.6% transgender) | Community venues | P I | SO | In young adulthood: Depression, suicidal ideation and behavior, life satisfaction, self-esteem, social integration, heavy drinking, substance abuse, sexual risk |

| Schneider (2012) | 2008 | U.S. (NE) | 20,406 | 6% | School-based | G C | Depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, self-injury, suicide attempt, suicide attempt requiring medical treatment | |

| Sinclair (2012) | 2008–2009 | U.S. (MW) | 17,366 | 5.4% (includes transgender participants) | School-based | G C | SO | Panic and depressive symptoms, self-injury, long-term mental health problems (i.e., requiring medical treatment), suicidal ideation |

| Swearer (2008) | 2005 | U.S. (MW) | 251 | Sexual minority status not assessed | School-based | V P I R | SO | Aggression, anxiety, depression, hopelessness, internal-external locus of control, perceptions of school climate |

| Toomey (2012) | 2003–2005 | U.S. (W) | 1,415 | 19.1% (1.7% transgender) | Gay-Straight Alliances | P G | GIE | Perceptions of safety for gender nonconforming peers |

| Toomey (2010) | N.S. | U.S. (W) | 245 | 100% (8.6% transgender) | Community venues | P I | SO | In young adulthood: depression and life satisfaction |

| Walls (2010) | 2006 | U.S. | 265 | 100% (4.9% transgender) | Community venues, web-based | G | SOGIE | Cutting behavior (self-injury) |

| Williams (2005) | N.S. | Canada | 194 | 50% | School-based | V P SH | SPL | Depression, externalizing symptoms |

| Wyss (2004) | N.S. | U.S. | 7 | 100% transgender or gender-variant | Web-based | V P R S I | GIE | Emotional and behavioral responses to victimization |

Table 2.

Linked Publications included in the Review

| Data Source | Publications |

|---|---|

| Dane County Youth Assessment (Wisconsin, U.S.), 2005 | Birkett, Espelage, & Koenig, 2009Espelage, Aragon, Birkett, & Koenig, 2008 |

| Dane County Youth Assessment (Wisconsin, U.S.), 2009 | Poteat, Mereish, DiGiovanni, & Koenig, 2011Sinclair, Bauman, Poteat, Koenig, & Russell, 2012 |

| Family Acceptance Project young adult survey (California, U.S.) | Russell, Ryan, Toomey, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2011Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, Card, & Russell, 2010 |

| The Luton Study (U.K.) | Rivers, 2001, 2004 |

| Preventing School Harassment Survey (California, U.S.) | McGuire, Anderson, Roomey, & Russell, 2010Toomey, McGuire, & Russell, 2012 |

Study Designs and Participants

Most studies that we reviewed were quantitative (n = 31); three were qualitative only and five studies reported a mix of quantitative and qualitative findings. With only one exception, the studies were based on cross-sectional data collected from participants at one point in time. In the one study with a longitudinal design, Poteat and Espelage (2007) collected data from middle school students twice over a one-year period. In a few cases, authors reported that their analyses were based on data from one wave of a longitudinal study (D’Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006; Swearer, Turner, Givens, & Pollack, 2008). Thus, while we can hope to see more findings from longitudinal studies published in the future, for now the cross-sectional nature of the study designs is an overarching limitation, even for those studies that utilized more complex causal modeling data analytic techniques.

An additional limitation common to most of the reviewed studies is the use of non-probability sampling techniques. For studies that included sexual and gender minority participants only, participants were typically recruited via community venues (e.g., LGBT service providers), online, or using snowball sampling methods; methods were often used in combination to buffer against each method’s limitations. For studies that included both LGBT and other adolescents, school-based sampling techniques were most common, although they varied in their application. Data used in several of these studies were from large-scale surveys undertaken to assess the health of adolescents in a specified geographic area (i.e., metropolitan area, county or state); methods to select participating schools or students within schools in some cases, however, were not well described.

Notably, a few studies did use some probability sampling techniques. In one study, all the LGBQ students recruited in a survey conducted at five high schools in one Canadian city were matched with randomly selected heterosexual controls that were similar in terms of gender, grade, and school (Williams, Connolly, Pepler, & Craig, 2005). Participants in another study were drawn from a larger sample that had been previously recruited by means of a random telephone survey of men in one Vancouver city district (Landolt, Bartholomew, Saffrey, Oram, & Perlman, 2004). The most sophisticated example was the Youth Risk Behavior Survey in two U.S. states on which Bontempo and D’Augelli’s (2002) study was based; a two-stage cluster design was used to sample schools and classes within schools for survey participation.

Participants in the majority of studies (n = 23) were current adolescents only, ranging in age from 10 to 19. Seven studies included both adolescents and young adults (up to age 25); three focused on young adults only (ages 18–25); four focused on adults; and two studies, based on the same dataset, surveyed participants ranging in age from 16 to 54 (Rivers, 2001, 2004). Given the diversity of study settings, it is not surprising that the racial/ethnic makeup of the samples varied greatly from study to study. Racial/ethnic minorities comprised 25–50% of the sample in seven studies; in an additional nine studies, racial/ethnic minorities comprised more than 50% of the sample. Most studies included both male and female participants (n = 32), but six studies included males only and one included females only. Data on gender minority youth were relatively scarce within the 39 studies. Of the twelve studies that included transgender participants, only four addressed their experiences independently of sexual minority participants, and another three studies focused on transgender or gender-variant youth specifically. Nine studies assessed participants’ gender expression; among those that assessed gender expression with formal scales, Hockenberry and Billingham’s (1987) Boyhood Gender Conformity Scale was most commonly used.

Another important way in which the reviewed studies differed from one another was in their approaches to assessing the sexual orientation of participants. In most studies, participants were asked whether they self-identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, and some also included “questioning” as an option. A small number of studies assessed romantic/sexual attractions (without assessing sexual orientation identity) or used multiple measures of sexual orientation (i.e., self-identification and same-sex sexual behavior). The researchers’ selection of sexual orientation measures may have been related to the age of participants in their sample, as was the case with the two studies that assessed sexual attractions, which included participants as young as 13 (Bos, Sandfort, De Bruyn, & Hakvoort, 2008; Busseri, Willoughby, Chalmers, & Bogaert, 2008). A few studies did assess sexual orientation identity in participants as young as 10 or 11; in one case this was a general school-based survey (Poteat, Mereish, Digiovanni, & Koenig, 2011) but in the others recruitment was facilitated by LGB organizations or school Gay-Straight Alliances (McGuire, Anderson, Toomey, & Russell, 2010; Pizmony-Levy, Kama, Shilo, & Lavee, 2008; Toomey, McGuire, & Russell, 2012). Four studies did not assess participants’ sexual orientation, but were included in our review because they assessed bias-based peer victimization (Felix, Furlong, & Austin, 2009; Kerr, Valois, Huebner, & Drane, 2011; Poteat & Espelage, 2007; Swearer et al., 2008).

Approaches to Measuring Peer Victimization

The reviewed studies were diverse in their approaches to measuring peer victimization. We have provided an overview of this diversity in Table 1. Experiences of peer victimization were typically measured with multi-item scales or with sub-scales that assessed different types of victimization, such as the University of Illinois Victimization Scale (Espelage & Holt, 2001) or the American Association of University Women’s Sexual Harassment Scale (AAUW, 1993). All measures of peer victimization used in these studies were based on participant self-report.

For purposes of comparison, we have used the available descriptions of study measures to categorize the types of victimization studied. We should stress that, although we have applied a common typology in summarizing the types of victimization assessed in each study, we do not mean to imply that each individual type of victimization was assessed in the same way across studies. The typology used is consistent with that used by Hawker and Boulton (2000) in their meta-analysis of the relationship between peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment, but includes the additional categories sexual victimization and sexual harassment. Verbal victimization, which was most commonly studied, included being called names, teased, insulted, or threatened to be hurt or beat up. Physical victimization included the following types of experiences: being threatened or injured with a weapon, punched, kicked, hit, beaten, pushed, chased or followed, spit on, having objects thrown at you, and having property damaged or stolen. Sexual victimization included rape and sexual abuse or assault. A small number of studies assessed sexual harassment, which encompassed being the target of sexual jokes, comments, or gestures, being touched or grabbed in a sexual way, being flashed or mooned, and being pressured for a date.

We also note studies that assessed indirect forms of peer victimization alongside more direct behaviors. Relational victimization involved being purposefully excluded by peers from activities. Indirect victimization refers to behaviors such as having rumors or lies spread about oneself. Two studies assessed cyberbullying, operationalized as being bullied, teased, or threatened by means of the internet, a phone/text messaging, or other electronic communications (Schneider, O’Donnell, Stueve, & Coulter, 2012; Sinclair, Bauman, Poteat, Koenig, & Russell, 2012). Several studies did not assess specific forms of victimization or assessed both specific and general types of peer victimization. We have categorized these studies, which measured how often participants were “harassed,” “bullied,” or “picked on,” for example, as addressing general victimization. We should note that some studies also assessed victimization that occurred in settings outside the school, but that we have limited our analysis only to victimization that occurred at school or was perpetrated by adolescent peers.

The reviewed studies furthermore varied in terms of whether and how they assessed participants’ attributions for victimization. In Table 1, we have noted whether the study authors assessed any attributions for victimization related to sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. D’Augelli, Grossman, and Starks (2006), for example, asked participants in their study if they had “ever been called names, teased, or threatened with being hurt or beat up because you’re lesbian (or gay or bisexual, depending on the interviewee’s self-identification), or someone thought you were” (p. 1465). This would be an example of peer victimization related to sexual orientation. Other studies assessed peer victimization related to gender identity and expression; Toomey, McGuire, and Russell (2012), for example, asked participants to indicate how often they had been bullied or harassed “because you aren’t as ‘masculine’ as other guys” or “aren’t as ‘feminine’ as other girls” (p. 190). Participants in some studies were asked not whether they were harassed because of actual or perceived LGB status, but whether they had experienced “anti-gay verbal abuse” (Plöderl, Faistauer, & Fartacek, 2010) or had been harassed using slurs such as “fag” or “dyke” (Gruber & Fineran, 2008), or “homo” or “lesbo” (Poteat & Espelage, 2007). In Table 1, we refer to such studies as assessing peer victimization that involved sexually prejudiced language. Some studies that did assess attributions for victimization only did so in relation to specific victimization subtypes and not all the subtypes assessed in those studies.

Represented in the collection of 39 reviewed papers are studies of varying levels of complexity that address our research question about outcomes associated with peer victimization related to sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. A diverse range of psychosocial and health outcomes were assessed in relation to peer victimization, as shown in the right-most column in Table 1. Most studies utilized structured survey research methods, with relatively few using qualitative research methods such as focus groups and interviews. Findings of specific studies are discussed below.

Qualitative Studies

Among the studies included in our review, three were strictly qualitative (Butler, Alpaslan, Strümpher, & Astbury, 2003; Grossman & D’Augelli, 2006; Wyss, 2004); one paper reported on related, but independent, quantitative and qualitative studies (McGuire et al., 2010); and four studies used methods (interviews and surveys with open-ended questions) that allowed for the collection of some qualitative data from participants (D’Augelli et al., 2006; Jordan, Vaughan, & Woodworth, 1997; Pilkington & D’Augelli, 1995; Rivers, 2001). All of the qualitative studies addressed the experiences of sexual and gender minority youth. Even though the qualitative studies included in our review were based on small samples and it is unclear to what extent those sampled are representative of sexual and gender minority youth in general, they do offer some valuable information about the breadth of outcomes potentially associated with peer victimization. These studies also allowed the participants to communicate about their victimization experiences in their own voices.

Despite the diverse settings and populations, there were common themes related to school difficulties that emerged from the qualitative studies. In semi-structured interviews, gay and lesbian adolescents and young adults in South Africa (N = 18) linked their experiences of victimization by both peers and teachers to feelings of fear, anxiety/nervousness, and embarrassment, as well as academic difficulties and injury resulting from physical victimization (Butler et al., 2003). In a survey of U.S. LGB adolescents and young adults, Pilkington and D’Augelli (1995) asked participants to describe how they changed their behavior as a result of victimization. Almost half (46%) of the participants reported modifying their behavior in school or other community settings for this reason. The researchers organized reported behavior changes into four categories: “act[ing] straight in public” (reported by 73% of females and 55% of males); avoiding certain places and situations (e.g., changing schools; reported by 20% of females and 31% of males); avoiding gay or lesbian people (reported by nearly 10%); and self-defense (reported by 5% of males; Pilkington & D’Augelli, 1995, p. 45).

The qualitative studies also provided some of the best available data on the experiences of transgender and gender non-conforming youth. In the quantitative studies, these youth were typically not studied separately from their LGB peers, as their numbers were usually very small. Reporting on a handful of interviews (N = 7) conducted face-to-face or over email with people who were out as transgender or self-labeled as genderqueer in high school and were recruited using web-based methods, Wyss (2004) identified the following outcomes associated with peer victimization: academic difficulties; school drop-out; feelings of fearfulness, powerlessness, anxiety, and anger; lowered self-esteem; self-injury; and suicidal feelings and attempts. Participants in this study also reported coping with peer victimization through the use of avoidance strategies (such as cutting class), self-defense strategies (weight-training, vigilance), and drug and alcohol use, and adopting gender conforming behaviors in an effort to prevent future attacks. Similar responses to peer victimization have been reported by transgender participants in subsequent qualitative studies with larger samples.

For example, transgender participants (N = 24) reported in focus group discussions that most people in their lives reacted negatively to their gender non-conforming behavior and that school was a site for experiences such as verbal harassment, assault, being propositioned for sex, or being called by their birth name after indicating that a chosen name was preferable (Grossman & D’Augelli, 2006). Although some transgender participants said they received support from LGB people at their schools, rejection by classmates and teachers and victimization at school was associated with feelings of shame, academic difficulties, and dropping out. They reported transferring schools as a result of the victimization they experienced, either to a dedicated school for LGBT students or schools known to have large LGBT populations (Grossman & D’Augelli, 2006). Transferring schools, sometimes to charter or alternative schools and sometimes more than once, was also reported by participants (N = 36) in another focus group study with transgender adolescents and young adults (McGuire et al., 2010). Participants described responses to victimization that included aggressive responses (i.e., fighting back) and deflecting harassment with humor or through social connections (McGuire et al., 2010). The fact that participants in both of these focus group studies were recruited through community-based organizations serving LGBT youth might limit the generalizability of the findings, as these participants’ access to and utilization of services may distinguish them from other gender minority youth.

Quantitative Studies with Adolescent Samples

School-related outcomes

School-related outcomes (e.g., sense of school belonging, truancy) associated with peer victimization were assessed in quantitative studies of varying designs. Some were studies of bias-based victimization in which the actual sexual orientation of participants was not assessed. For example, in a U.S. study of adolescent males (ages 14–18), it was found that those who were bullied by being called gay had more negative perceptions of school climate in comparison to their peers who were bullied for other reasons (Swearer et al., 2008). In a study with a large (N = 70,600) sample of California middle and high school students, Felix, Furlong and Austin (2009) used cluster analytic techniques to empirically sort adolescents into subgroups according to their victimization experiences and examine how perceptions of being victimized due to bias (including sexual orientation-related bias) related to the primary type of victimization that was experienced, i.e., sexual harassment, and verbal and physical victimization. Those who were targeted due to their sexual orientation were more than nine times more likely to be polyvictims (reporting moderate to high levels of all types of peer victimization) than to belong to another victimization cluster (e.g., nonvictims, predominantly sexually harassed, predominantly physically victimized, predominantly teased), and polyvictims were in turn more likely to feel unsafe at school and have poorer grades than nonvictims and other victimized clusters.

Poteat and Espelage (2007) studied outcomes associated with homophobic name-calling in a sample of middle school students, assessing their sense of school belonging and other outcomes at two points over a one-year period (homophobic name-calling was only assessed at the second time point). After controlling for Time 1 levels of the outcome variables, the authors found that homophobic victimization was significantly associated with a lower sense of school belonging in males, but not females. School belonging refers to “the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included and supported by others” at school (Aerts, Van Houtte, Dewaele, Cox, & Vincke, 2012, p. 92), and was measured with a revised version of the Psychological Sense of School Membership scale, which was used in several reviewed studies (Bosworth, Espelage, & Simon, 1999; Goodenow, 1993).

School-related outcomes have also been assessed in samples of LGBT youth. In a sample of LGBT youth from the Midwestern U.S., sexual orientation-related peer victimization was found to be independently associated with discipline problems (e.g., being sent to the principal’s office, being expelled from school) but not with sense of school belonging or achievement (i.e., GPA; Murdock & Bolch, 2005). Among LGBQ adolescents in Israel, verbal, but not physical, victimization related to sexual orientation was independently associated with a lower sense of belonging to one’s school; both types of victimization were associated with a diminished sense of respect by peers (Pizmony-Levy et al., 2008). McGuire et al. (2010), examining transgender middle and high school students’ perceptions of school safety in a quantitative survey, showed that, even after accounting for protective school factors, hearing peers make negative comments or use slurs based on gender identity and expression was correlated with lower perceptions of school safety. A separate study based on the same dataset, but incorporating responses from non-transgender students, showed that participants’ personal experiences with general victimization at school were significantly associated with perceptions of school as less safe for gender non-conforming male and female peers (defined as “guys who aren’t as masculine as other guys and girls who aren’t as feminine as other girls”; Toomey et al., 2012, p. 190). Personal experiences with gender non-conformity-based victimization were associated with perceptions of school as less safe for gender non-conforming females only (Toomey et al., 2012).

More complex studies have compared school-related outcomes associated with peer victimization in LGBT and heterosexual students. Findings from the U.S. suggest that homophobic peer victimization is negatively associated with school belonging in all youth, whether LGBTQ or heterosexual, with the strength of the association being greater in LGBTQ youth (Poteat et al., 2011). In studies from the Netherlands and Belgium, respectively, peer victimization has been found to mediate associations between sexual orientation and identification with one’s school (Bos et al., 2008) or sense of school belonging (Aerts et al., 2012); in the latter case, this relationship was found for girls only (LGB and heterosexual males did not differ in terms of sense of school belonging). In other words, peer victimization partially accounted for the lower levels of school identification or belonging seen in sexual minority youth. Other research offers evidence that peer victimization moderates the relationship between sexual orientation and school-related outcomes. Among younger adolescents (U.S. seventh and eighth graders), LGB and questioning youth experiencing high levels of homophobic teasing reported more truancy than their heterosexual peers who were teased at similarly high levels (Birkett, Espelage, & Koenig, 2009). Of the older adolescents (high schoolers) who participated in the same study, those who were sexually questioning and experiencing the most homophobic victimization reported significantly more negative perceptions of school climate than did their LGB and heterosexual peers who were victimized just as often; interaction effects were, however, small (Espelage, Aragon, Birkett, & Koenig, 2008).

Alcohol/drug use and other risk behaviors

Several papers examined the relationship between peer victimization and risk behaviors such as alcohol and drug use and sexual activity. Operationalizations of risk behavior varied from study to study. In a sample of LGB adolescents and young adults (21 years or younger), frequency of sexual orientation-related victimization in high school was not related to reported levels of substance use in the past year (D’Augelli et al., 2002). Participants were surveyed about their use of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and various other drugs, and levels of substance use did not differ between the high school and college students that were in the sample. Somewhat contrasting findings come from a study by Gruber and Fineran (2008), who surveyed middle and high school students about how often they “drank alcohol or used drugs because of things that happened at school” during the current school year. The experience of sexual harassment was associated with alcohol/drug use in LGBQ adolescents, and also (but not as strongly) in heterosexual females. Given the differing measures of substance use (one being linked to school, the other more general) and of peer victimization, as well as differing approaches to sampling in these two studies (one drawing from LGB youth groups, the other from a middle and high school in one community), perhaps it is not surprising that the findings of these two studies were not more consistent (D’Augelli et al., 2002; Gruber & Fineran, 2008).

Comparing heterosexual and LGBTQ youth with regard to risk behavior outcomes has been the focus of other research. Among a sample of Canadian adolescents, peer victimization partially accounted for the higher level of risk behavior involvement seen in adolescents with same-sex and bisexual attractions, as compared to peers with heterosexual attractions (Busseri et al., 2008). This study used an index measure of risk behavior involvement that addressed alcohol and tobacco use, drug use, sexual activity, delinquency (e.g., shoplifting, sneaking out, carrying a weapon), aggression toward others, and gambling (Busseri et al., 2008). Peer victimization together with other significant mediators (e.g., attitudes toward risk, parental relationships, academic orientation) attenuated 66% of the difference in risk behavior involvement between heterosexually and bisexually attracted youth, and 50% of the difference in risk behavior involvement between heterosexually and same-sex attracted youth. Peer victimization has also been found to moderate the relationship between sexual orientation and risk behavior. In one of the only reviewed studies that used data collected via a probability sampling method -- Youth Risk Behavior Surveys in two U.S. states – Bontempo and D’Augelli (2002) demonstrated that, while LGB adolescents experiencing low levels of physical victimization were similar to their heterosexual peers in terms of risk behavior (smoking, alcohol and drug use, and sexual risks), those LGB adolescents experiencing high levels of victimization reported more smoking and more alcohol and drug use than did heterosexual adolescents who also experienced high levels of victimization. Effect sizes were moderate to large, particularly with regard to the interaction between victimization and sexual orientation in males. The interaction of sexual orientation and peer victimization on sexual risk was only significant in males (d = 0.8; Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002). As with the school-related outcomes already reviewed, studies by Birkett (2002) and Espelage (2008) and their colleagues found that homophobic peer victimization moderated the relationship between sexual orientation and substance use (though again, in the latter study for which effect size calculations were provided, interaction effects were small). LGB and questioning adolescents who experienced high levels of homophobic victimization reported more frequent alcohol and marijuana use than did heterosexual peers who experienced homophobic victimization at similar levels (Birkett et al., 2009; Espelage et al., 2008).

Mental health outcomes

Mental health outcomes were by far those most commonly studied in relation to peer victimization. Various mental health outcomes were studied – such as depression, suicidality, and traumatic stress – and diverse measures were used to assess the same constructs across studies. The use of measures that assess multiple dimensions of mental health at once (e.g., depression and suicidality together, measures of externalizing and internalizing symptoms) further complicates interpretation of findings across multiple studies. While many of the studies provide evidence for an empirical association between peer victimization related to sexual orientation or gender identity/expression and negative mental health outcomes, findings varied and surely are related to overall study design, the participants involved, and the ways that peer victimization and mental health status were assessed.

Experiences with peer victimization have been associated with negative emotional experiences and traumatic stress symptoms in sexual minority youth, though the strength of these associations was generally modest (D’Augelli et al., 2006; D’Augelli et al., 2002; Jordan, Vaughan, & Woodworth, 1997). In some studies that assessed a broader range of factors potentially contributing to mental health outcomes in sexual minority youth, peer victimization did not emerge as a factor independently related to mental health. In these cases, family mental health problems, family functioning, and stressful life events (Elze, 2002) or identity disclosure and involvement in heterosexual relationships (Hegna & Wichstrøm, 2007) emerged as more strongly related to mental health.

Studies with both sexual minority and heterosexual participants examined peer victimization as a factor explaining mental health disparities between the two groups. In a study that compared Canadian LGBQ adolescents to age-, gender-, and school-matched heterosexual controls, the LGBQ participants reported significantly more peer victimization, and depressive and externalizing symptoms (Williams et al., 2005). Peer victimization mediated the relationship between sexual orientation and externalizing, but not depressive, symptoms. Bos et al. (2008), however, found that peer role strain (a measure of relational, verbal, physical, and other general forms of peer victimization) partially explained why depressive symptoms were higher in same-sex attracted Dutch youth, compared to their peers without same-sex attractions.

As with school-related and risk behavior outcomes, other research has indicated that peer victimization moderates the relationship between sexual orientation and depression and suicidal behavior, with the result being that outcomes for victimized sexual minority youth are worse than for similarly victimized heterosexual youth (Birkett et al., 2009; Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002; Espelage et al., 2008). Although the effect sizes for the interaction between sexual orientation and peer victimization on depression/suicidality were moderate to large in Bontempo and D’Augelli’s (2002) study, they were small in the study by Espelage et al. (2008). In one of the few studies to assess racial/ethnic differences, homophobic victimization was found to be associated with suicidal ideation and attempts in white and minority LGBTQ adolescents and white heterosexual adolescents, but not in minority heterosexual adolescents (Poteat et al., 2011).

Some studies, including two concerned with cyberbullying, did not directly explore the role of peer victimization in explaining mental health disparities between heterosexual and sexual minority youth (Schneider et al., 2012; Sinclair et al., 2012). Schneider et al. (2012) sought to examine the overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying, as well as the prevalence of the former and its correlated psychological outcomes. Data were collected from more than 20,000 U.S. high school students in the Boston metropolitan area as part of a regional adolescent health census, and participants were asked about both cyberbullying and traditional bullying (being repeatedly teased, physically victimized, or excluded by other students). The findings showed that LGBQ participants were much more likely than heterosexual-identified peers to report being bullied (42.3% vs. 24.8%) or cyberbullied (33.1% vs. 14.5%). Participants who were victims of both traditional and cyberbullying reported the most psychological distress, with four- or five-fold greater odds of having depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, self-injury, and suicide attempts. Participants who were cyberbullied only were at a somewhat heightened risk of psychological distress in comparison to those who were bullied only. The relative correlation between cyberbullying and psychological distress in heterosexual and sexual minority youth was not assessed. Sinclair et al. (2012) examined the bias component in cyber-harassment using survey data from more than 17,000 Wisconsin adolescents. In comparison to non-harassed participants, those who experienced cyber- and bias-related harassment in combination (12% of the total participants) were significantly more likely to be LGBTQ and reported the highest levels of panic symptoms, depression, mental health problems requiring medical intervention, and suicidal ideation and attempts. Both studies of cyberbullying indicate that sexual minority youth may be particularly vulnerable to this type of peer victimization, and that this type of peer victimization is associated with several negative health outcomes.

Finally, two studies found correlations between peer victimization involving sexually prejudiced language and mental health outcomes, although the sexual orientation of participants was not assessed. Poteat and Espelage (2007) found that homophobic name-calling predicted different mental health outcomes in middle school boys and girls: anxiety, depression, and distress in boys and withdrawal in girls. Swearer et al. (2008) found that male adolescents who were bullied by being called gay reported higher depression and anxiety than did peers who were bullied for other reasons.

Other psychosocial and health outcomes

Other psychosocial and health outcomes, assessed in relation to peer victimization in a smaller number of studies, include life satisfaction, self-esteem, internalized homophobia, and self-injury (Bos et al., 2008; D’Augelli et al., 2002; Gruber & Fineran, 2007, 2008; Kerr et al., 2011; Schneider et al., 2012; Sinclair et al., 2012; Walls, Laser, Nickels, & Wisneski, 2010). Peer victimization was found to be modestly but significantly correlated with internalized homophobia in LGB adolescents and young adults (D’Augelli et al., 2002). Another study found that LGBT adolescents and young adults who had been harassed at school due to their sexual orientation or gender identity had more than twice the odds of engaging in cutting behavior than did their peers without such experiences (Walls et al., 2010). Kerr et al. (2011) found that bullying related to sexual orientation was associated with decreased life satisfaction in male, but not female, adolescents. Peer victimization has also been found to partially explain lower self-esteem in same-sex attracted adolescents in comparison to peers without same-sex attractions (Bos et al., 2008).

Quantitative Studies with LGBT Adult Samples

Several studies included in our review made use of retrospective reports of peer victimization provided by adult study participants. With the exception of one study that utilized retrospective reports of both peer victimization and suicidal behavior (Friedman, Koeske, Silvestre, Korr, & Sites, 2006), the focus of these studies was on the relationship between peer victimization in adolescence and psychosocial and health outcomes in adulthood. To date, these studies provide the best available data on possible long-term outcomes associated with sexual orientation and gender identity/expression-related peer victimization. Although these studies varied in their focus on peer victimization – with some focusing on it specifically and others considering it as one of many possible predictors of the outcome studied – for our purposes they can be thought of as case-control style studies, with peer victimization as the exposure of interest. These studies share a common limitation in their dependence on participants’ recall of their victimization experiences, which is especially pronounced in studies that contained a heterogeneous group of participants with respect to age. Asking participants who are aged 21–25 to recall adolescent experiences may be an entirely different matter than asking participants between the ages of 20 and 70 to do the same. Aside from recall bias, there may be important generational differences with regard to school experiences, which could imply differing long-term outcomes across age cohorts (Plöderl et al., 2010).

One study involving gay men from a broad range of ages (18 to 65 years) found that peer victimization in adolescence was correlated with depressive symptoms in adulthood (Josephson & Whiffen, 2007). The direct relationship between past peer victimization and current depressive symptoms was mediated by unassured-submissive interpersonal behavior (i.e., tendency to behave in unassertive ways in relationships with others). The authors suggest that peer victimization may “predispose gay men to interact in ways that set them up for further harassment,” or that unassured-submissive behaviors may reflect shame resulting from past victimization (Josephson & Whiffen, 2007, p. 69). Peer victimization has also been studied in relation to childhood gender non-conformity and adult attachment style. In a study of adult gay and bisexual men (ranging in age from 20 to 70, M = 38.6, SD = 9.4), recalled peer rejection was found to be independently associated with adult attachment anxiety and to mediate the association between childhood gender non-conformity and attachment anxiety (Landolt et al., 2004).

In a pair of studies based on the same dataset, Rivers (2001, 2004) explored a range of possible health outcomes associated with peer victimization over the long term by surveying119 LGB individuals in the United Kingdom (ages 16–54) who reported peer victimization related to their sexual orientation. In the 2001 study, Rivers compared this sample to a sample of non-bullied LGB adults; the bullied LGB participants were more likely to exhibit symptoms of depression, but were not more anxious, more possessive in relationships, and were no different in terms of willingness to disclose their sexual orientation to others. The bullied LGB adults had significantly more positive attitudes toward homosexuality than did their non-bullied counterparts (Rivers, 2001). Rivers reported in his 2004 paper that 26% of study participants said they had been or continued to be regularly distressed by their past victimization experiences. Similarly, Rivers reported in his 2004 paper that those study participants who were suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (17% of the sample) were relatively more accepting of their own sexual orientation. The author’s interpretation is that reinforcement of LGB identity by peers through bullying might push some individuals toward greater self-acceptance (Rivers, 2004).

Two studies, both of which were conducted online, explored the association between peer victimization and self-reported suicide attempts (Hidaka & Operario, 2006; Plöderl et al., 2010). Among Japanese gay and bisexual men (mean age 26 years; range not specified), having been bullied at school because of being perceived as gay or homosexual was not independently associated with a lifetime history of suicide attempts, although verbal harassment with sexually prejudiced language (not necessarily at school) was. Showing consistency with what was found among Norwegian LGB adolescents and young adults, findings from this study in Japan indicate that factors such as identity disclosure and involvement in heterosexual relationships are more strongly associated with suicide attempts (Hegna & Wichstrøm, 2007; Hidaka & Operario, 2006). Among Austrian gay and bisexual men (ranging in age from 18 to 45), however, odds of ever making a suicide attempt “because your homosexuality caused such a hard time at school” were significantly higher among those who reported homophobic peer victimization (OR = 4.04, 95% CI: 2.02–8.46) or peer victimization related to gender non-conformity (for those frequently victimized this way compared to those who were not, OR = 5.86, 95% CI: 1.84–17.1; Plöderl et al., 2010, pp. 822–823). Given the difference in the way the two studies (Hidaka & Operario, 2006; Plöderl et al., 2010) operationalized their outcome measures – suicide attempts in general vs. school-related suicide attempts – perhaps it is not surprising that their findings differed. In the Austrian study, those gay and bisexual men who had experienced peer victimization were also more likely to say they did not feel accepted at school.

Other studies that we reviewed limited participation to LGBT young adults (age 25 and under). Russell, Ryan, Toomey, Diaz, and Sanchez (2011) assessed depression, suicidal ideation and behavior, life satisfaction, self-esteem, social integration, alcohol and substance use, and sexual risk in LGBT participants ranging from 21 to 25 years of age. Past peer victimization related to sexual orientation was independently associated with higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation, lower levels of life satisfaction, self-esteem, and social integration in young adulthood, and having experienced a high level of victimization increased one’s odds of experiencing depression (OR = 2.6, 95% CI: 1.29–5.25), attempting suicide (OR = 5.62, 95% CI: 2.65–11.94) and making a suicide attempt that required medical attention (OR = 5.60, 95% CI: 2.26–13.87), having ever been diagnosed with an STD (OR = 2.53, 95% CI: 1.17–5.47), and believing oneself to be at risk for HIV infection (OR = 2.28, 95% CI: 1.09–4.76). Peer victimization did not predict heavy drinking or substance abuse in young adulthood (Russell et al., 2011). In a separate study based on the same dataset, Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, Card and Russell (2010) examined whether adolescent peer victimization based on actual or perceived LGBT identity explained the relationship between adolescent gender non-conformity and young adult depression and life satisfaction. Greater gender non-conformity in adolescence was associated with more victimization, which in turn was associated with higher levels of depression and lower levels of life satisfaction in young adulthood; direct relationships between adolescent gender non-conformity and young adult life satisfaction and depression were not significant (Toomey et al., 2010).

Discussion and Conclusions

Although research on peer victimization related to sexual orientation and gender identity or expression provides insight into only one aspect of the lives of sexual and gender minority adolescents, this literature nonetheless offers important lessons for public health practitioners, health and sexuality educators, researchers, and those who work with adolescents or in school settings. The studies we have reviewed here, which included participants from 12 countries, suggest that peer victimization is correlated with a variety of negative psychosocial and health outcomes. At this time, however, evidence for correlation between sexual orientation and gender identity/expression-related peer victimization and some psychosocial and health outcomes is stronger than others, and remains evidence of association only. The outcomes best characterized are sense of school belonging, depression, and suicidality. Overall there is strong evidence that those who are victimized by peers exhibit a lower sense of belonging to their schools and higher levels of depressive symptoms (Pizmony-Levy et al., 2008; Poteat & Espelage, 2007; Poteat et al., 2011). Furthermore, peer victimization mediates or moderates the relationship between sexual orientation and these outcomes (Aerts et al., 2012; Birkett et al., 2009; Bos et al., 2008; Espelage et al., 2008).

Evidence regarding the relationship between peer victimization and suicidal ideation or actual attempts is mixed. In studies surveying large, school-based samples of adolescents, peer victimization has been shown to moderate the relationship between sexual orientation and suicidality: LGBQ adolescents who experience peer victimization report more suicidal ideation and attempts than heterosexual peers who are victimized just as often (Birkett et al., 2009; Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002; Espelage et al., 2008). Alternatively, studies with LGB-only samples have found that peer victimization was not independently associated with history of suicide attempts. Discrepancies likely arise from the operationalization of peer victimization in those studies, the age range of participants (adults were included), and the wide variety of predictors assessed in relation to suicide attempts (Hegna & Wichstrøm, 2007; Hidaka & Operario, 2006). We should also note that some of the most oft-cited studies that have examined victimization as a risk factor for suicidality among sexual minority youth were excluded from this review because they used broader measures of victimization, and did not focus on peer victimization specifically (e.g., Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995; Hershberger, Pilkington, & D’Augelli, 1997; Russell & Joyner, 2001).

Methods by which the strength of the relationships between peer victimization and given outcomes were calculated and reported varied from study to study, with few studies reporting effect size information in relation to specific outcomes. The available information suggests that relationships with most outcomes are modest, which is not surprising given the range of possible determinants of psychosocial adjustment and health. Addressing sexual and gender minority youths’ greater exposure to peer victimization will not be sufficient to attenuate the observed health disparities among these youth in comparison to their majority counterparts. The overall findings with regard to peer victimization, school belonging, depression, and suicidality, suggest, however, that adolescents who are exhibiting academic or other persistent difficulties at school might benefit from screening for peer victimization, and those who are known to be experiencing peer victimization might benefit from screening for depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation (Felix et al., 2009; Friedman et al., 2006).

Since Savin-Williams published his review in 1994, we have learned considerably more about both the types of outcomes that are associated with peer victimization and about the hypothesized causal pathways between peer victimization and psychosocial and health outcomes. That the reviewed studies vary in both their methods and their time/place contextual parameters constitutes both an asset and a limitation. The differing study designs and operationalizations of relevant constructs present a challenge to the synthesis of research findings. At the same time, support for one’s conclusions is bolstered when findings are repeated across diverse types of studies and samples.

Even still, this more recent literature remains limited in several critical ways. It is striking that mental health outcomes have received the most research attention, with less emphasis on outcomes such as injury and educational disruptions that might be more proximal to peer victimization experiences. The most important limitation of the literature, which must guide interpretation of all findings, is the dominance of cross-sectional study designs. There is a clear need for longitudinal data that can better speak to causal relationships between peer victimization related to sexual orientation and gender identity or expression and the outcomes that have been studied. It seems widely assumed that peer victimization precedes negative psychosocial and health outcomes. While findings from longitudinal studies in the general bullying literature give some support to this assumption (e.g., Bond, Carlin, Thomas, Rubin, & Patton, 2001), it is worth noting that alternate patterns, suggesting that adjustment problems precede victimization and that victimization and poor adjustment then mutually reinforce one another, have also been observed (Hodges & Perry, 1999).

There has also been a noticeable lack of theory-guided work in this area. A few authors referred to Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological model of human development, generally in building a rationale for studying the relation of contextual factors such as peer victimization to adolescent health (Birkett et al., 2009; Bos et al., 2008; Murdock & Bolch, 2005). Research grounded in theories that are “integrated sets of propositions that are empirically testable”--what Reiss (1999) calls substantive or middle-range theory (p. 246) – was very rare. Toomey et al. (2010) and Poteat et al. (2011) both utilized concepts from Meyer’s (2003) minority stress model, conceptualizing peer victimization related to sexual orientation or gender identity/expression as a distal minority stressor that contributes to mental health outcomes (in Meyer’s model, proximal minority stressors are internal, e.g., internalized homophobia). However, neither study represents a full test of the minority stress model. The studies that most closely approximate tests of the minority stress model are those by Bos et al. (2008), Busseri (2008), and Williams et al. (2005), all of which included mediational analyses and involved mixed samples of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents that allowed for comparisons; none of these studies were designed to test the minority stress model, however. Busseri et al. (2008) instead summarize the argument that factors such as peer victimization explain the higher levels of risk behavior observed in sexual minority youth – i.e., that the relationship between sexual orientation and risk behavior is indirect – as the “mediator hypothesis” (p. 69). These authors’ contributions lay some foundation for the further work that must be done to develop and empirically test theoretical propositions.

We also note that the literature on peer victimization related to sexual orientation and gender identity/expression is limited in its overall ability to speak to differences within sexual and gender minority populations. Gender differences were accounted for in several studies, though we have been unable to give a full accounting of those analyses here. However, we have much less information about how racial/ethnic differences may affect the relationship between peer victimization and health; these were addressed in only a small number of studies (Pilkington & D’Augelli, 1995; Poteat et al., 2011). Felix et al. (2008) have noted that, with respect to samples in U.S.-based studies, some minority groups are particularly underrepresented, namely Native American and Asian American youth. In addition, the experiences of bisexual, questioning, and transgender adolescents were considered distinctly from those of their lesbian and gay peers in only a handful of studies. Adolescents are furthermore developmentally diverse, and their exposure to peer victimization and ability to access resources and support may vary accordingly, but we as yet know little about differences across early, middle, and late adolescence. While the lack of clarity on within-group differences is an understandable limitation given the difficulty of recruiting sexual and gender minority adolescents to participate in research, it is one that must be addressed if we are to meaningfully expand the knowledge base in this area. Although recruiting adolescent study participants through their schools may produce the least biased samples, there may be research questions for which samples drawn from LGBT community venues (which could facilitate easier access to the target population) are appropriate.

Methodological Implications and Recommendations

Our review highlights the different approaches that researchers have used to assess sexual and gender identity among adolescent populations and to assess adolescents’ exposure to peer victimization. We can offer several recommendations to enhance comparability and precision in future studies.

With regard to the assessment of sexual identity in adolescents: It is clear that distinguishing only between self-identified heterosexual, gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents is not sufficient to identify those at risk for peer victimization and its associated psychosocial and health outcomes; questioning adolescents seem to be particularly vulnerable (Birkett et al., 2009; Espelage et al., 2008). Youth with same-sex or bisexual attractions are also more likely to experience peer victimization than are those without such attractions (Bos et al., 2008; Busseri et al., 2008). For some samples, particularly of young adolescents, it may be more developmentally appropriate to assess romantic and/or sexual attractions, as indicated by a study of LGB adults’ sexual orientation identity development; among those who experienced their sexual orientation developmental milestones early in life (i.e., before age 20), self-identification as LGB came approximately four years after their first experience of same-sex attractions (Calzo, Antonucci, Mays, & Cochran, 2011). Some research also indicates that adolescents find questions about sexual attractions easiest to interpret and that some have difficulty choosing a sexual identity option on close-ended survey questions (Austin, Conron, Patel, Freedner, 2006).

In addition to assessing adolescents’ sexual attractions and/or orientation, it would be worthwhile to assess their disclosure of their same-sex attractions or LGBTQ identity. Although few studies included in our review assessed disclosure specifically, those that did indicated that more openness about one’s LGB identity in school settings, along with increased gender nonconformity, may be important risk factors for peer victimization in sexual minority youth (D’Augelli et al., 2006; D’Augelli et al., 2002; Pilkington & D’Augelli, 1995). We recommend systematically assessing gender non-conformity as a risk factor for peer victimization, not only among sexual minority adolescents, but in all adolescents. In some adolescents who have not self-labeled as LGB or disclosed any same-sex attractions to peers, it may in fact be their gender non-conformity that is putting them at risk for victimization.

We support recommendations by Katz-Wise and Hyde (2012) that advise researchers to assess perceived reasons for victimization, or whether individuals believe they were victimized due to their sexual orientation, gender identity/expression, or other reasons. As Bontempo and D’Augelli (2002) have noted, issues of construct validity arise when using more general measures of peer victimization in samples of LGBT youth and assuming that the victimization is related to their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. Measures sensitive enough to assess bias-related cases of victimization, and yet specific enough to differentiate between casual (however unacceptable) uses of sexually prejudiced language that are not meant to intimidate a single individual, are needed. Qualitative research is well suited to address research questions about how adolescents understand the motivations of those who victimize them. Meyer’s (2012) qualitative study demonstrates, for example, that some LGBT adults of color interpret victimization not only as homophobic but as “attempts to punish them for not appropriately representing their racial communities” (p. 858).

In order to understand the potential impact of peer victimization, it is important to know how sexual and gender minority youth interpret the meaning of the victimization experience. It is possible that psychosocial and health outcomes are dependent upon specific attributions that victimized youth make. For example, sexual minority youth who believe they are victimized because of their sexual orientation may experience internalized homophobia; this may not be the case, however, if they feel targeted for other (e.g., appearance, race, school performance) or non-specific reasons. Part of adolescents’ interpretation of their experience includes why they believe they were victimized as a result of their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. In the studies we reviewed, we found related questions asked with varying levels of precision; survey questions that asked whether adolescents were victimized by peers because they were LGB or because of their actual or perceived sexual orientation, for example, generally did not address why those victimized would believe that to be the case. Measures that assessed the use of sexually prejudiced language in acts of victimization (e.g., insults, graffiti) offered more detail about what was actually experienced by the victim. This type of information could help us to disentangle peer victimization related to gender expression or perceived sexual orientation. Clarification regarding victimizing behaviors would also be useful to school staff and other adults who are responsible for identifying and stopping such behaviors. More ambiguous or less readily observable behaviors, such a social exclusion or rumor spreading, might require different responses.

Finally, because all the studies reviewed here relied on self-report measures of peer victimization, triangulating these measures with peer or teacher reports, as has been done in the broader literature on bullying in children and adolescents (Arseneault, 2010), would represent a methodological expansion of this literature. As has been observed with regard to the literature on peer victimization in general, there is the problem of “shared method variance” – effect sizes between peer victimization and maladjustment are larger when informants are the same (i.e., victimization and adjustment are both assessed via self-report) as opposed to different (Hawker & Boulton, 2000). Assessing victimization and outcome variables from different or multiple perspectives is recommended to avoid potential bias (Hawker & Boulton, 2000).

Limitations of the Review

Our conclusions are based on a select set of research publications: those we were able to identify for inclusion in our review and those that met our inclusion criteria. We used four electronic databases to conduct our literature search and it is possible that we overlooked some relevant studies. Studies published in languages other than English are not represented here, nor are those that were not published in peer-reviewed journals. As with any literature review, the pool of available studies from which we drew may have been limited by publication bias, or the more frequent reporting and publication of statistically significant results in comparison to null results (Dwan et al., 2008). In drawing conclusions based on this review, we are furthermore subject to the limitations of the studies contained within it. Finally, given social changes in both the acceptance of homosexuality and the increased attention to violence and bullying in schools, the extent to which findings of older studies would apply today is unclear, nor is it possible to construct a clear historical narrative given the different settings in which these studies were conducted and the different methods they utilized.

Future Directions

We hope to see future studies address gaps in the literature on peer victimization related to sexual orientation and gender identity/expression, while also attending to some of the methodological issues we have already discussed. Additional studies from settings outside the U.S., especially those in the Global South or where LGBT communities are just emerging, would expand the literature in critical ways. We also know relatively little about indirect and relational victimization and cyberbullying among sexual and gender minority youth: how might they be marginalized in their schools by these types of victimization, and with what consequences? How do sexual and gender minority youth cope and seek help when they are targeted in ways that may be less observable to the adults around them?

We also need further clarification regarding how peer victimization affects identity development in sexual and gender minority youth. How do victimized youth feel about their sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression? How is peer victimization related to the timing of adolescents’ recognition of their sexual attractions and their labeling of their sexual identity? Such research questions should be addressed with longitudinal research designs that will follow participants from young adolescence into adulthood, and with special attention to the experiences of transgender and gender non-conforming youth, the intersections of racial/ethnic and sexual/gender minority identity, and the experiences of LGB-identified versus same-sex-attracted or questioning adolescents.

Although we did not address these findings in our review, it is notable that several studies have examined factors that might protect adolescents from outcomes associated with peer victimization, such as parent and teacher support and institutional supports at school (e.g., Bos et al., 2008; Poteat et al., 2011; Sandfort, Bos, Collier, & Metselaar, 2010; Toomey et al., 2012). This type of research represents an important step toward understanding why some sexual and gender minority youth are negatively affected by peer victimization, while others may not be. Further research with regard to protective factors is needed.