Effect of culture conditions on the phenotype of THP-1 monocyte cell line (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2014 Jul 1.

Published in final edited form as: Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013 Apr 29;70(1):80–86. doi: 10.1111/aji.12129

Abstract

Problem

Macrophage function has many implications in a variety of diseases. Understanding their biology becomes imperative when trying to elucidate immune cell interactions with their environment and in vitro cell lines allow researchers to manipulate these interactions. A common cell line used is THP-1, a promyeloid cell line suggestive to outside factors, and therefore sensitive to culture conditions. In this study we describe how culture conditions can alter THP-1 morphology and in turn affect their response to differentiation stimuli.

Method of Study

THP-1 cells were cultured in two conditions and treated with PMA or MCSF. CD14 surface expression was determined by flow cytometry and cytokine/chemokine production determined by multiplex analysis.

Results

Culture conditions of THP-1 affect their response to PMA. Highly confluent THP-1 cells differentiate into a heterogeneous population responsive to PMA as seen by an increase in CD14 expression. However, these cells, cultured in low confluence, remain as a homogenous population and do not gain CD14. Additionally, there are major differences in the constitutive cytokine profile.

Conclusion

We demonstrate that the culture conditions of THP-1 cells can alter their response PMA. This suggests that culture techniques may account for the discrepancy in the literature of both basal THP-1 phenotype and their response to PMA.

Keywords: differentiation, monocytes, macrophages, PMA, THP-1

INTRODUCTION

Macrophages originate from circulating monocytes and are recruited from the blood to the tissues 1 by specific signals originating from the local microenvironment. 2-4. Macrophages become highly specialized in response to local factors, which, in turn, determine their phenotype and function 5, 6. Macrophage function is important in many aspects of tissue homeostasis, including repair and cleanup, as well as mounting an efficient immune response that can effect the innate response and also the resulting adaptive response 7-11. Since macrophages mediate innate immune responses and contribute to the adaptive immune response through their antigen presenting capacity it is relevant to understand their biology.

Tissue macrophage function and phenotypes have been studied extensively and it is well established that these cells have a high level of plasticity. Pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory macrophages induced from peripheral monocytes by different stimuli have been named M1 or M2 macrophages to parallel the Th1/Th2 paradigm. More recent data suggests that even this classification is an oversimplification as phenotypes are very specific to their microenvironment 12.

There are several methods used to study macrophages in vitro; most commonly used are primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and monocyte cell lines of varying degrees of differentiation. These populations are frequently used to model macrophage function since primary tissue macrophages are difficult to grow and expand in vitro. Peripheral blood monocytes can be used in culture to characterize macrophage function; unfortunately, they can be difficult to work with due to lack of purity, variability, and availability of samples. It is therefore beneficial to use cell lines, which eliminate these issues and can be maintained as a homogeneous ongoing population 13.

There are several examples of monocytic cell lines, such as U937, HL-6p or THP-1. The human acute monocytic leukemia THP-1 is the most common cell line utilized to study monocyte/macrophage differentiation and function 13 14. They are highly plastic, sensitive to many stimuli, and therefore can be polarized into multiple lineages 9, 15, 16. Early studies indicate that THP-1 cells resemble primary monocytes and macrophages in morphology and differentiation property 17. PMA treatment of THP-1 cells leads to a more mature phenotype with a lower rate of proliferation, higher levels of adherence, higher rate of phagocytosis and increased cell-surface expression of CD11b and CD14 13, 18-20. Interestingly, following these early studies, the THP-1 response to PMA and their differentiation phenotype has been found to be highly variable between researchers and publications. For example, CD14 is a common marker used to show differentiation of monocytes to macrophages 20, 21. In general, macrophages gain CD14 while loss of CD14 is associated with a dendritic cell phenotype 22. However, we found significant inconsistencies in numerous reports in terms of CD14 expression by THP-1 cells at basal levels as well as using the same stimuli.

In the present study we evaluate the effect of culture techniques on the phenotype of THP-1 cells and the resulting effect on THP-1 response to differentiation stimuli. We demonstrate that the basal line status of the culture, prior to any stimuli, is a critical determining factor for the type of differentiation response.

Material and Methods

Cell culture

THP-1 cells, a pro-monocytic cell line, were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA), 10 mM Hepes, 0.1 mM MEM non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 100 nM penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies). Two subtypes, Condition I and Condition II, of THP-1 cells were determined. Condition I was cultured at a high density (2.0 × 106/ml) with media being refreshed every 5-7 days for a period of 1 month. Condition II was cultured at a lower density (2.5 × 105/ml) with media being refreshed every three days for one week; both conditions were maintained at 5% CO2, 37°C.

Reagents

THP-1 cells were differentiated with PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or MCSF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) at a concentration of 10ng/ml in RPMI 1640 + 1% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products). Treatments were refreshed every three days through day six. Cell-free conditioned media was collected at day 0 and day six, and stored at −40°C until further analysis. Basal THP-1 cells were plated and collected after 24hrs, spun and washed in FACS buffer (1X PBS, 0.05% BSA, and 1% sodium azide) prior to flow analysis.

Luminex

Cell free supernatant cytokine and chemokine secretion was determined by multiplex analysis using the BioPLex assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with detection and analysis using the Luminex 100 IS system (Luminex, Austin, TX).

Flow cytometry

The expression of CD14 was evaluated by flow cytometry using anti-human CD14 phycoerythrin-conjugated antibody (1:20) (Ebioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). FSC/SSC in both conditions were acquired with identical settings using a BD FACS Calibur. All groups were compared to an isotype control, mouse IgG1 K isotype Control (Ebioscience) and experiments were performed at least in triplicate.

Results

Differential response of THP-1 cells

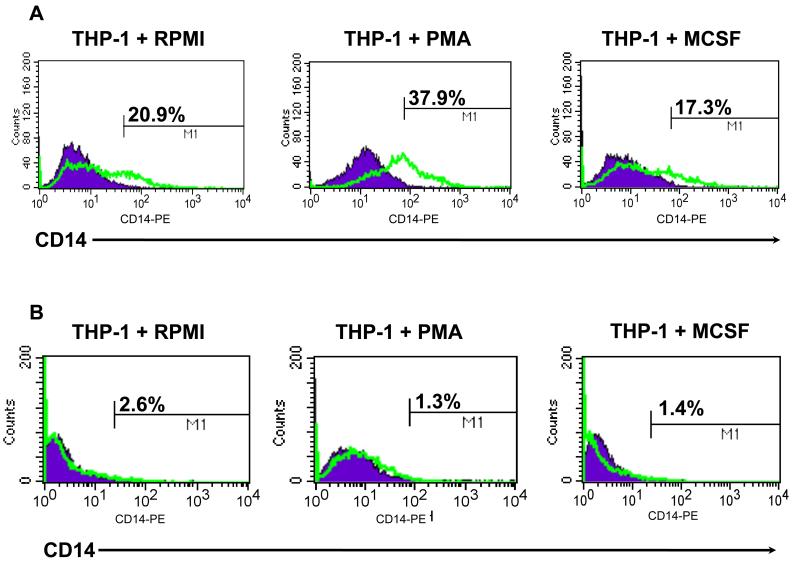

We tested the response of THP-1 cells to the common macrophage differentiation factors PMA and M-CSF as described in materials and methods to evaluate whether PMA or M-CSF was able to induce expression of CD14, a marker of monocyte lineage. Initial studies were done utilizing a long-term THP-1 culture, grown at a higher density (Condition I). As shown in figure 1A, this THP-1 culture was characterized having 20.9% CD14+ cells without any stimulation. Upon treatment with PMA, we observed a significant increase in the number of CD14+ cells (37.9%), while treatment with M-CSF showed no significant change (17.3%) (Fig.1A). A second study was done using a new culture at a lower density (Condition II). THP-1 cells were treated with the same stimuli, concentrations and time and evaluated for CD14 expression. Unexpectedly, the percentage of CD14+ cells in the control group was almost undetectable (2.6%). Moreover, upon treatment with PMA no change in CD14 expression was seen (Fig.1B).

Figure 1.

Differential response to PMA by THP-1. THP-1 cells were treated with 10ng/ml PMA or MCSF as described in materials and methods and CD14 expression determined by flow cytometry. In Condition I (A), CD14 expression increased after treatment with PMA as compared to NT, however, in Condition II (B) there was no change; MCSF had little effect on CD14; data are representative of at least three experiments.

We then evaluated whether any of the stimuli would change the morphologic characteristics of the THP-1 cells by evaluating their size (FSC) and density (SSC) by flow cytometry. In Condition I, 58% of cells cultured in RPMI were large and had low complexity; in response to PMA 33% became more granular, while 16% of those lost their size. In response to M-CSF 39% remained large with low complexity while 11% became more granular, but most maintained their size. (Fig.2A). However, for Condition II the cells cultured in RPMI were all small with low complexity and in response to PMA 56% of the cells increased complexity, but all maintained the same size. In contrast, treatment of Condition II with M-CSF maintained nearly similar characteristics as the RPMI control (Fig.2B).

Figure 2.

THP-1 cells differentially change morphology in response to PMA. THP-1 cells were treated with 10ng/ml PMA or MCSF as described in materials and methods and size (FSC) and complexity (SSC) determined by flow cytometry. In Condition I (A), PMA treatment creates a more macrophage phenotype characterized by larger cells that gain complexity. In Condition II (B) PMA pushes THP-1 cells to a more granular phenotype as seen by an increase in complexity but not size; data are representative of at least three experiments.

To understand the differential response from the two cultures we compared the morphology of the cell cultures prior to any treatment. As shown in figure 3, the morphological characteristics of the two cultures were remarkably different. The culture which was responsive to PMA (Condition I), was a heterogeneous culture formed by a high percentage of big cells with low density. However, the culture that did not respond to PMA (Condition II) was much more homogeneous, composed of only small cells.

Figure 3.

THP-1 morphology under basal conditions. THP-1 cells were collected after 48hrs in culture, and analyzed for size (FSC) and complexity (SSC) determined by flow cytometry size. Condition I THP-1 cells, without any stimulant, are heterogeneous in size while the cells cultured in Condition II are a more compact and homogeneous population; data are representative of at least three experiments.

Cytokine profile

Next we analyzed supernatants from cultures using both conditions, with and without PMA, and determined the cytokine profiles. Cytokines produced by the two cultures without stimulation were similar, however, the concentrations of IL-8, MIP-1a and MIP-1b were significantly enhanced in Condition I, while VEGF and IL-12p70 were higher in Condition II (Fig.4). In response to PMA we observed a much higher response of many proinflammatory cytokines in Condition I compared to Condition II, while MCP-1, MIP-1β, GROα, and RANTES had a similar response in both conditions. Also, the decreased levels of VEGF and IL-12p70 were more striking in Condition I compared to Condition II (Table I).

Figure 4.

THP-1 cytokine secretion under basal conditions. THP-1 cells were collected after 48hrs in culture, and cell-free supernatants analyzed for cytokine and chemokine secretion by multiplex. Condition 1 THP-1 cells constitutively secrete higher levels of cytokines as compared to condition II, with exception of IL-12 and VEGF.

Table I. Differential Cytokine response of THP-1 cells to PMA.

THP-1 cells cytokine secretion after stimulation with PMA. THP-1 cells were treated with 10ng/ml PMA or MCSF as described in materials and methods and cell-free supernatants analyzed for cytokine and chemokine secretion by multiplex; data is represented as fold change compared to the NT.

| cytokine/chemokine | Condition I | Condition II |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1b | 109.7F↑ | 6.9F↑ |

| IL-6 | 285F↑ | 224F↑ |

| IL-8 | 331F↑ | 90.5F↑ |

| IL-12p70 | 18.9F↓ | 1.6F↓ |

| G-CSF | 321.2F↑ | 825F↑ |

| MCP-1 | 3.1F↑ | 3.2F↑ |

| MIP-1α | 2.2F↑ | 1.1F↑ |

| MIP-1β | 2.1F↑ | 2.9F↑ |

| RANTES | 1.2F↑ | 1.3F↑ |

| TNFα | 5491F↑ | 1737F↑ |

| VEGF | 580F↓ | 2F↓ |

| GROα | 113F↑ | 200F↑ |

Discussion

We report the effect of culture conditions on THP-1 cells response to differentiation stimuli. We demonstrate that the expression of CD14, a widely used marker for monocyte-macrophage differentiation, reflects the conditions of the culture and will vary as a marker for response to PMA.

Macrophage differentiation and polarization occur in vivo under the influence of the localized cytokine milieu 23-26. In vitro studies for the purpose of studying macrophage differentiation and function rely on cellular differentiation in culture using cytokines or pharmacologic agents. The cellular models used in these studies include monocytes isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) or leukemic cell lines of which HL-60, U937 and THP-1 cells are the most commonly used.

THP-1 cells are a leukemic cell line derived from a patient with acute monocytic leukemia 17. Since its original description in 1980, THP-1 cells have been used as a model for monocyte-macrophage differentiation in numerous studies, indicative of the relevance of these cells for our understanding macrophage biology 27,13.

PMA is one of the most common reagents used to induce THP-1 differentiation into macrophage-like cells. The phenotype of the cells following PMA stimulation varies between studies, with some of the differences attributed to the time of incubation or concentration used in the study.

The use of cell lines, such as THP-1, has numerous advantages compared to primary cultures. First, homogeneous genetic background minimizes the degree of variability in the cell phenotype; second, it allows for genetic modification by transfection of genes; and third, cell lines standardize protocols for differentiation into various macrophage subtypes. A disadvantage of cell lines is their sensitivity to good culture conditions. Either monolayers or cells in suspension can undergo differentiation as result of inconsistent culture conditions and consequently affect the outcome of the study.

Looking at CD14 as one of the markers for the response of THP-1 cells to PMA it is surprising to find that some of the differences between studies are already present at controls, not in the treatment. Some studies have reported almost 90% CD14 expression in unstimulated THP-1 cells 28 29 while others have reported lower or no expression 20 30. Similarly, reports describing THP-1 CD14 levels in response to PMA varies from poor or no response 31, 32 to increased levels 33 34 20.

In this study we evaluated the effect of culture conditions on the heterogeneity of the THP-1 cell line. In low-density cultures (Condition II), we found, as reported in initial studies, these cells are homogeneous, characterized by small cells with low density 35, 36 are CD14- and differentiation with PMA does not increase CD14 expression. However, cells kept for an extended period of time at high cell density (Condition I), the culture becomes heterogeneous with a high number of big cells, increased density, and high percentage of CD14+ cells. This culture is highly sensitive to PMA and CD14 expression increases significantly.

All these changes are reflected in the cytokine profile. The levels of cytokines produced in response to PMA are not the same in the two culture conditions. The culture with a heterogeneous cell population (Condition I) has a stronger response to PMA as demonstrated by higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

In summary, culture conditions of THP-1 such as concentration and time is extremely important to take into consideration before starting differentiation studies using THP-1 cells. The heterogeneity of the culture can affect the expression levels of CD14 and may potentially be used as a marker for the quality of the culture. This data also indicates the need to be cautious when interpreting data where conditions of the basal cell culture are not described or presented.

Acknowledgment

This study is funded in part by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services P01HD054713.

References

- 1.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2005;5:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor PR, Gordon S. Monocyte heterogeneity and innate immunity. Immunity. 2003;19:2–4. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yona S, Gordon S. Inflammation: Glucocorticoids turn the monocyte switch. Immunology and cell biology. 2007;85:81–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murao S, Gemmell MA, Callaham MF, Anderson NL, Huberman E. Control of macrophage cell differentiation in human promyelocytic HL-60 leukemia cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate. Cancer Res. 1983;43:4989–4996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavaillon JM. Cytokines and macrophages. Biomed Pharmacother. 1994;48:445–453. doi: 10.1016/0753-3322(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavaillon JM, Fitting C, Haeffner-Cavaillon N, Kirsch SJ, Warren HS. Cytokine response by monocytes and macrophages to free and lipoprotein-bound lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2375–2382. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2375-2382.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, Mantovani A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J Immunol. 2006;177:7303–7311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geske FJ, Monks J, Lehman L, Fadok VA. The role of the macrophage in apoptosis: hunter, gatherer, and regulator. Int J Hematol. 2002;76:16–26. doi: 10.1007/BF02982714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruck W, Porada P, Poser S, Rieckmann P, Hanefeld F, Kretzschmar HA, Lassmann H. Monocyte/macrophage differentiation in early multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:788–796. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruckmeier M, Kuehnl A, Culmes M, Pelisek J, Eckstein HH. Impact of oxLDL and LPS on C-type Natriuretic Peptide System is Different between THP-1 Cells and Human Peripheral Blood Monocytic Cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;30:199–209. doi: 10.1159/000339044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duffield JS, Erwig LP, Wei X, Liew FY, Rees AJ, Savill JS. Activated macrophages direct apoptosis and suppress mitosis of mesangial cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:2110–2119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvero AB, Montagna MK, Craveiro V, Liu L, Mor G. Distinct Subpopulations of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cells Can Differentially Induce Macrophages and T Regulatory Cells Toward a Pro-Tumor Phenotype. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qin Z. The use of THP-1 cells as a model for mimicking the function and regulation of monocytes and macrophages in the vasculature. Atherosclerosis. 2012;221:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuchiya S, Kobayashi Y, Goto Y, Okumura H, Nakae S, Konno T, Tada K. Induction of maturation in cultured human monocytic leukemia cells by a phorbol diester. Cancer Res. 1982;42:1530–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berges C, Naujokat C, Tinapp S, Wieczorek H, Hoh A, Sadeghi M, Opelz G, Daniel V. A cell line model for the differentiation of human dendritic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:896–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bremner TA, Chatterjee D, Han Z, Tsan MF, Wyche JH. THP-1 monocytic leukemia cells express Fas ligand constitutively and kill Fas-positive Jurkat cells. Leuk Res. 1999;23:865–870. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(99)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuchiya S, Yamabe M, Yamaguchi Y, Kobayashi Y, Konno T, Tada K. Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1) International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 1980;26:171–176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910260208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abrahams VM, Kim YM, Straszewski SL, Romero R, Mor G. Macrophages and apoptotic cell clearance during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;51:275–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mor G, Straszewski-Chavez SL, Abrahams VM. Macrophage-trophoblast interactions. Methods Mol Med. 2006;122:149–163. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-989-3:149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwende H, Fitzke E, Ambs P, Dieter P. Differences in the state of differentiation of THP-1 cells induced by phorbol ester and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Leuk Biol. 1996;59:555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dobrovolskaia MA, Vogel SN. Toll receptors, CD14, and macrophage activation and deactivation by LPS. Microbes and infection / Institut Pasteur. 2002;4:903–914. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01613-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gersuk GM, Razai LW, Marr KA. Methods of in vitro macrophage maturation confer variable inflammatory responses in association with altered expression of cell surface dectin-1. J Immunol Meth. 2008;329:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollard JW. Trophic macrophages in development and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:259–270. doi: 10.1038/nri2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mantovani A, Sica A, Locati M. Macrophage polarization comes of age. Immunity. 2005;23:344–346. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagamatsu T, Schust DJ. The contribution of macrophages to normal and pathological pregnancies. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:460–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auwerx J. The human leukemia cell line, THP-1: a multifacetted model for the study of monocyte-macrophage differentiation. Experientia. 1991;47:22–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02041244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster N, Cheetham J, Taylor JJ, Preshaw PM. VIP Inhibits Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS-induced immune responses in human monocytes. J Dent Res. 2005;84:999–1004. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ciabattini A, Cuppone AM, Pulimeno R, Iannelli F, Pozzi G, Medaglini D. Stimulation of human monocytes with the gram-positive vaccine vector Streptococcus gordonii. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:1037–1043. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00110-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tobias PS, Soldau K, Kline L, Lee JD, Kato K, Martin TP, Ulevitch RJ. Cross-linking of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to CD14 on THP-1 cells mediated by LPS-binding protein. J Immunol. 1993;150:3011–3021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleit HB. Monoclonal antibodies to human neutrophil Fc gamma RIII (CD16) identify polypeptide epitopes. Clinical immunology and immunopathology. 1991;59:222–235. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(91)90020-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fleit HB, Kobasiuk CD. The human monocyte-like cell line THP-1 expresses Fc gamma RI and Fc gamma RII. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;49:556–565. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park EK, Jung HS, Yang HI, Yoo MC, Kim C, Kim KS. Optimized THP-1 differentiation is required for the detection of responses to weak stimuli. Inflamm Res. 2007;56:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s00011-007-6115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding J, Lin L, Hang W, Yan X. Beryllium uptake and related biological effects studied in THP-1 differentiated macrophages. Metallomics. 2009;1:471–478. doi: 10.1039/b913265a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hassall DG. Three probe flow cytometry of a human foam-cell forming macrophage. Cytometry. 1992;13:381–388. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990130408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daigneault M, Preston JA, Marriott HM, Whyte MK, Dockrell DH. The identification of markers of macrophage differentiation in PMA-stimulated THP-1 cells and monocyte-derived macrophages. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]