Targeting the tumor microenvironment: JAK-STAT3 signaling (original) (raw)

Abstract

Persistent JAK-STAT3 signaling is implicated in many aspects of tumorigenesis. Apart from its tumor-intrinsic effects, STAT3 also exerts tumor-extrinsic effects, supporting tumor survival and metastasis. These involve the regulation of paracrine cytokine signaling, alterations in metastatic sites rendering these permissive for the growth of cancer cells and subversion of host immune responses to create an immunosuppressive environment. Targeting this signaling pathway is considered a novel promising therapeutic approach, especially in the context of tumor immunity. In this article, we will review to what extent JAK-STAT3-targeted therapies affect the tumor microenvironment and whether the observed effects underlie responsiveness to therapy.

Keywords: IL-6, JAK-STAT3 signaling, tumor microenvironment, targeted therapies

Introduction: Aberrant JAK-STAT Signaling in Tumors

The JAK-STAT pathway is an important oncogenic signaling cascade that consists of the Janus kinase (JAK) family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases and the signal transducer of activator of transcription (STAT) family of transcription factors.1 Under physiological conditions, the ligand-dependent activation of the JAK-STAT pathway is transient and tightly regulated. However, in most malignancies, STAT proteins and particularly STAT3, is aberrantly activated (tyrosine phosphorylation) in the majority of cancers.2,3

A number of malignancies have been associated with genetic abnormalities that lead to increased STAT3 expression/activation (epithelial and hematopoietic). For example, somatic gain-of-function mutations within the extracellular domain (D2) of the gp130 receptor chain resulted in the hyperactivation of the receptor, the consequent phosphorylation of STAT3 and the development of inflammatory hepatocellular adenoma.4 Other cancers display somatic mutations in the STAT3-inactivating phosphatases T and δ, whereas the epigenetic silencing of SOCS3—a negative regulator of STAT3—is observed in many epithelial cancers.5,6 Constitutively activating mutations within the STAT3 gene (exon 21; SH2 domain) have also been identified in large granular lymphocytic leukemias,7 whereas aberrant activation of the JAK2 kinase—an upstream activator of STAT3—has also been directly implicated in several hematopoietic malignancies and myeloproliferative disorders, primarily due to genetic abnormalities (somatic activating mutation) in the JAK2 kinase (V617F exon 12) or in the thrombopoietin receptor (MPL) resulting in STAT3/5 hyperactivation.8

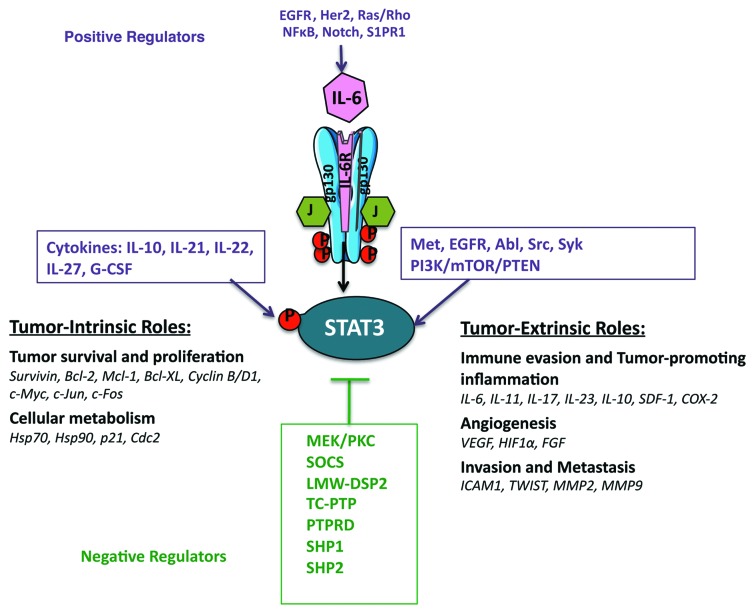

However, the most common mechanism mediating STAT3 tyrosine phosphorylation in malignancies of epithelial origin is via increased/sustained IL-6 (family)/gp130 signaling.9,10 Indeed, the induction of IL-6 expression is positively regulated in a feed-forward loop resulting in the amplification of this pathway.10 NFκB, Notch and S1PR1 signaling are also positive regulators of IL-6 expression and are frequently co-expressed with activated STAT3 in cancers,11,12 whereas the aberrant signaling of other “oncogenic” pathways, such as EGFR, HER2, Ras and Rho can also result in increased IL-6 production and subsequent STAT3 activation.13-15

Other positive regulators of the JAK-STAT3 pathway within the tumor stroma include IL-10, IL-21, IL-22, IL-27, IL-1β, TNFα, CCL2 (which also promote a pro-inflammatory microenvironment), G-CSF, leptin, the PI3K/mTOR/PTEN pathway, the receptor tyrosine kinases MET and EGFR and the non-receptor tyrosine kinases Abl, Src and Syk.16,17 In addition to tyrosine phosphorylation, STAT3 can also be serine phosphorylated within its transcriptional activation domain, acetylated, methylated, sumoylated and ubiquitylated, which alters its stability, transcriptional activation and nuclear localization.18 Negative regulators of the JAK-STAT pathway comprise the SOCS proteins, the protein tyrosine phosphatases LMW-DSP2, TC-PTP, PTPRD, SHP1 and SHP2.6,19,20 Thus, the regulation of STAT3 activation in cancer is the result of the crosstalk between oncogenic signaling pathways, and redundancies in these give rise to persistent STAT3 activation.

Role of JAK-STAT3 Signaling in Tumorigenesis

The JAK-STAT3 signaling has been regarded as a critical regulator of tumorigenesis. Indeed, the strength and duration of STAT3 activation and the formation of feed-forward signaling loops within the tumor stroma are major determinants of cytokine responses and the arising cellular functions that promote tumor growth.21,22 Some of the tumor-intrinsic functions of activated STAT3 include: differentiation, cancer stem cell expansion/survival (WNT5A, CD44 and jagged), proliferation (stimulates transcription of cyclin D1, cdc2, c-myc, cyclinB1, c-jun, c-fos and greb1), apoptosis (upregulates the expression of the pro-survival Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, Bcl-w and Survivin transcripts) and response to hypoxia and cellular metabolism (HIF1α, Glut1, Hsp70, Hsp90, p21 and Cdc2).3,16,23 The JAK-STAT3 pathway also regulates tumor-extrinsic aspects of tumorigenesis including: angiogenesis (regulates transcription of VEGF and HIF1α), endothelial cell survival and neo-vascularization, immune cell infiltration, mesenchymal cell activation and finally progression to metastasis24,25 (Fig. 1). Activated STAT3 has also been recently found to regulate the expression of miRNAs (e.g., miR-200c, Let-7, miR-21, miR-181b-1 and others), which globally regulate the expression of numerous transcripts involved in inflammation and tumorigenesis.26-28

Figure 1. The role of activated STAT3 and its molecular targets in tumorigenesis.

Much of the evidence supporting the pivotal role of activated STAT3 in tumorigenesis arises from studies involving the overexpression of activated STAT3 or its specific deletion. For example, inducible expression of a constitutively activated form of STAT3 (STAT3C) in the lungs resulted in chronic inflammation, increased cytokine production and eventually to de novo tumorigenesis29 or targeted expression in the bladder or skin leading to mutagen induced invasive cancer.30,31 Additionally, STAT3C expression in conjunction with the Her2-neu oncogene enhanced metastasis.32 Mice expressing mutant forms of the gp130 receptor (gp130Y757F) resulting in STAT3 hyperactivation, developed gastric adenomas and lymphopoiesis.33 In contrast, mice deficient for STAT3 in specific cell types do not develop oncogene- or mutagen-induced cancers and/or develop less aggressive cancers.34,35 Furthermore, in studies using KRAS-driven mouse models of PDAC (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma), it was revealed that STAT3 inactivation suppressed PDAC formation via multiple mechanisms affecting both the tumor cells and the tumor stroma, such as inhibition of macrophage recruitment, a decrease in inflammatory infiltrates and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and LIF.36,37 The observation that silencing of STAT3 in many cancer-derived cell lines had marginal effects on in vitro cellular growth, but a significant reduction on in vivo tumor growth38,39 suggest a dominant tumor-extrinsic role for STAT3. Indeed, STAT3 serves as a principal mediator of the crosstalk between tumor cells and the cells that constitute the tumor microenvironment, promoting an immunosuppressive microenvironment with tumor-enhancing properties.

JAK-STAT3 Signaling in the Tumor Microenvironment

pSTAT3 expression and paracrine cytokine expression

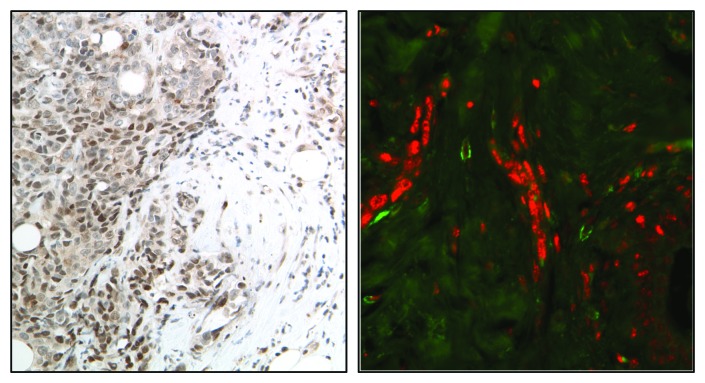

There is growing evidence supporting the role of STAT3 in the regulation of the molecular processes shaping the tumor microenvironment as well as the function of the cells that constitute it. Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent approaches used to examine the intensity, distribution and number of cells expressing activated STAT3 have revealed significant heterogeneity within the tumor stroma, as the highest pSTAT3 levels are primarily located on the leading edge of tumors in association with stromal, immune and endothelial cells40 (Fig. 2). Phosphorylated STAT3 expression in cells that constitute the tumor stroma is now recognized as a critical contributor to cancer pathogenesis and response to therapy.

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical (A) and immunofluorescent (B) images showing localization of activated STAT3 (red) on the edge of human breast tumors in association with myeloid (CD33+, green) cells.

It has been hypothesized that the observed heterogeneity in pSTAT3 expression results from paracrine sources of IL-6 from cancer-associated fibroblasts, adipocytes or myeloid cells on the edge of the tumors and in metastatic sites.41-43 Significantly, IL-6 is a central regulator of a network of autocrine and paracrine cytokines and growth factors such as IL-8, CCL5, CCL2, CCL3, IL1-β, GM-CSF, VEGF and MCP-1 that are overexpressed in the tumor microenvironment promoting malignant growth and metastasis.44,45 Furthermore, the paracrine expression of IL-6 by tumor-associated cells can also induce the autocrine production of IL-6 and thus increased pSTAT3 expression by tumor and stromal cells, suggesting the presence of autocrine-paracrine amplification loops, as IL-6 promotes STAT3 phosphorylation, which in turn can transcriptionally regulate IL-6 expression.12,42 Additionally, targeting other oncogenic pathways may effectively reduce IL-6 levels, which in turn can modify the tumor microenvironment. For example, the Ido1 gene was disrupted in mouse models of lung and breast cancer, revealing a reduction in tumor burden that was associated with decreased IL-6 levels and an impairment of MDSC function.46

pSTAT3 expression and other cell types in tumor microenvironment

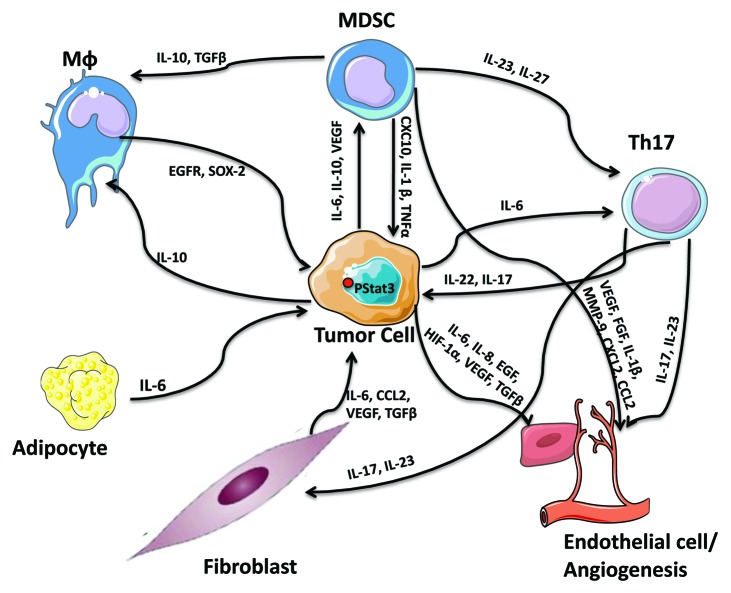

There is increasing evidence that links IL-6/STAT3 to the functional properties of the cells that form the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 3). For example, contrary to normal fibroblasts, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) released high levels of IL-6 and CCL2 upon STAT3 activation in co-cultured breast cancer cells, promoting cancer stem cell renewal and mammosphere forming capacity.47 Cancer-associated adipocytes were also found to promote breast tumor radioresistance via an increase in IL-6 expression,48 while aggressive breast tumors (correlating with the number of lymph nodes involved) expressed higher IL-6 levels in tumor-surrounding adipocytes, which in turn modified the cancer cell characteristics/phenotype to a more aggressive behavior with a greater migratory and invasive potential.43 Tumor-associated endothelial cells were also found to regulate STAT3 tumor-promoting responses. For example, soluble mediators from primary human dermal microvascular endothelial cells promoted phosphorylation of STAT3, Akt and ERK in a panel of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells; via an increase in IL-6, IL-8 and EGF expression in endothelial cells.49

Figure 3. The STAT3-dependent cytokine network as a regulator of cellular interactions with the tumor stroma.

In addition to the prominent role of activated STAT3 in the function of tumor-associated mesenchymal cells (fibroblasts, adipocytes and endothelial cells) in tumorigenesis and metastatic progression, emphasis should also be placed on the tumor-extrinsic role of STAT3 in promoting the creation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment and abrogating anti-tumor responses. The quality and quantity of immune-cell infiltrates within the tumor stroma has been described to determine the clinical course and response to therapy. Indeed, aberrant STAT3 expression in cancers has been associated with both the quantity and quality of immunosuppressive tumor-promoting myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and Th17 cells, while reducing DCs and minimizing anti-tumor responses.16 For example, IL-6, IL-10 and VEGF activate STAT3 and STAT3 hyperactivation conversely enhances myeloid-derived suppressor cell numbers and activity in tumor bearing hosts and blocks the differentiation and expansion of functional dendritic cells.50 IL-6 and STAT3 are also required for Th17 cell differentiation, which in turn sustains inflammation via the secretion of the IL-17 and IL-23 cytokines and are responsible for the secretion of the angiogenic factors VEGF and TGFβ in fibroblasts and endothelial cells. The secreted IL-17 and IL-23, in turn, stabilize the Th17 phenotype, demonstrating the presence of STAT3-dependent feed-forward loops within the microenvironment of the tumor stroma.51,52 STAT3-mediated IL-23 production (IL-23α/IL-23β heterodimers) promotes the inhibition of effector T-cell proliferation,53 while IL-27, a member of the IL-6/IL-12 family of cytokines was found to activate STAT3 stimulating the generation of the tumor-promoting IL-10-producing type 1 regulatory T cells via the suppression of RANKL expression.54 STAT3 was also recently demonstrated to positively regulate PD-L1 expression on tolerogenic antigen-presenting cells (PD-L1 is an inducer of tolerance and a negative regulator of anti-tumor immunity).55 STAT3-mediated IL-10 secretion was found to promote the formation of M2-macrophages. It has also been demonstrated that M2 macrophages regulate breast cancer stem cell function, via a novel EGFR/STAT3/Sox-2 paracrine signaling pathway, further supporting STAT3′s participation in regulation of the tumor microenvironment.56

STAT3 activation prevents anti-tumor immunity

STAT3’s role in preventing the initiation of anti-tumor responses is most evident from STAT3-deletion studies. Specifically, inactivation of STAT3 in hematopoietic cells revealed an anti-tumor response, which involved the activation of dendritic cells, T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, resulting in the suppression of tumor growth and metastasis in multiple syngeneic tumor models.57 Analogous studies of STAT3 inactivation in myeloid or T cells potently augmented effector functions of adoptively transferred T cells,58 while the prophylactic administration of breast cancer cells transfected with STAT3Y705 (a dominant-negative STAT3 vector) inhibited primary tumor growth in vivo by triggering an anti-tumor immune response that involved the participation of CD4+ T cells and cytotoxic NK cells.59 The therapeutic immunization of these cells resulted in the inhibition of tumor growth, promotion of tumor cell differentiation and decreased metastasis. The genetic or pharmacologic disruption of STAT3 in malignant B cells (MCL-bearing mice) augmented their immunogenicity, leading to increased activation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells and activation of anti-lymphoma immunity in vivo,60 whereas the deletion of STAT3 in myeloid cells or in vivo targeting of STAT3 in tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells and B cells resulted in enhanced CD8+ T cell responses, activation of tumor-associated monocytes and dendritic cells, with tumor regression.61 Moreover, deletion of STAT3 in myeloid cells or in vivo targeting of STAT3 in TLR9+ cells, such as DCs, MDSCs and B cells, by synthetically linking a STAT3 siRNA to a CpG oligonucleotide agonist of TLR9, resulted in enhanced CD8+ cell-mediated responses and an anti-tumor response.62 STAT3-deficient myeloid derived suppressor cells also failed to promote the formation of vessel-like structures in vitro, due to the reduction in the levels of the STAT3-dependent pro-angiogenic factors VEGF, bFGF, IL-1β, MMP-9, CXCL2 and CCL2,25 suggesting that the tumor immune microenvironment also regulates tumor angiogenesis with STAT3 playing a key role in this process.

Therapeutic Targeting of the JAK-STAT3 Pathway

Given the importance of the JAK-STAT3 pathway in the promotion of tumorigenesis via tumor-intrinsic and -extrinsic effects, many attempts are currently under development in order to target this pathway therapeutically (Table 1). It is hypothesized that targeting STAT3 will significantly reduce the immunosuppressive nature of the stroma and thus, may complement the existing forms of cancer therapy. Current attempts to target the IL-6/JAK-STAT3 pathway include the clinical use of IL-6 and IL-6 receptor blocking antibodies, the use of specific STAT3 inhibitors and JAK inhibitors.

Table 1. IL-6/JAK-STAT3 inhibitors.

| Inhibitor/drug | Target | Indication | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNTO-136, CNTO-328 | IL-6 | Myeloma, lupus, prostate cancer | Phase II |

| REGN-88 | IL-6 receptor | Rheumatoid arthritis | Phase I |

| Tocilizumab | IL-6 receptor | Rheumatoid arthritis | FDA approved |

| TG101348 | Pan JAK | Myeloproliferative neoplasms | Phase II |

| INCB18424 (Ruxolitinib) | JAK1/2 and Tyk2 | Myeloproliferative neoplasms | FDA approved |

| AZD1480 | JAK1/2 | Solid tumors; hematologic malignancies | Phase II |

| INCB28050 | JAK1/2 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Phase II |

| CYT387 | JAK1/2 | Myeloproliferative neoplasms | Phase II |

| SB1518, SB1578 | JAK1/2 | Myeloid/lymphoid malignancies | Phase II |

| AEG41174 | JAK2/BCR-ABL | Hematologic malignancies | Phase I |

| LY2784544 | JAK2 | Myeloproliferative neoplasms | Phase I |

| AC-430 | JAK2 | Myeloproliferative disorders | Phase I |

| BMS-911543 | JAK2 | Myeloproliferative disorders | Phase II |

| CP690550 | JAK3 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Phase III |

| AT-9283 | JAK2/3Aurora kinase A/B, ABL | Solid tumorMyeloid malignancies | Phases I–II |

| CEP-701 (lestaurtinib) | JAK2, FLT3, TrkA/B | Myeloproliferative malignancies | Phases I–II |

| STAT3 decoy | STAT3 DNA competitor | Head and neck cancer | Phase 0 |

IL-6 blockade

IL-6 is considered as a therapeutic target in several types of cancer.63 Pre-clinical testing of IL-6 ligand-binding antibodies and IL-6R blocking antibodies resulted in significant tumor growth inhibition either alone or in combination to chemotherapy.45 Clinically the IL-6 ligand-blocking antibody CNTO-328 is currently tested in phase I/II clinical trials in transplant-refractory myeloma and castrate-resistant prostate cancer.64,65

STAT3 inhibitors

Attempts to find direct inhibitors of STAT3 have focused on the development of agents that target the SH2 domain in order to prevent STAT3 phosphorylation and/or dimerization. For example, targeting the SH2 domain of STAT3 with a novel small molecule decreased the percentage of breast cancer tumor-initiating cells (CD44+/CD24−/low and ALDH+) as well as mammosphere formation.66 Similarly, the STAT3 SH2-binding proteins LLL12, 31 and 32, inhibit STAT3 phosphorylation and induce apoptosis in medulloblastoma and glioblastoma cells, human hepatocellular as well as pancreatic and breast cancer cells.67,68 Other direct inhibitors of STAT3 include peptidomimetics, designed small molecules that target STAT3 dimerization, as well as antisense oligonucleotides and small inhibitory RNAs that inhibit STAT3 transcription and translation.69 Although many of these compounds have shown reasonable specificity to disrupting STAT3 function, few of them have been developed clinically because of the high concentrations required to impart their effects. A promising direction may be in the development of double-stranded decoy oligonucleotides that act as STAT3-competitors to binding to target genes which have been developed clinically for head and neck cancers.70 Moreover, there are clinically tested and available molecules described to act as inhibitors of STAT3-dependent transcription. For example, nifuroxazide, a drug used for the treatment of diarrhea, was found to reduce pSTAT3 levels in multiple myeloma via inhibition of JAK2 and Tyk2.71 Similarly, pyrimethamine, which is used for the treament of malaria, was described to inhibit STAT3 activity and myeloma growth and is presently in clinical trials for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic leukemia.72

JAK inhibitors

The use of JAK inhibitors has been shown to be clinically effective in the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders.73 Additionally, JAK inhibitors (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 and combinations) are currently in clinical trials (phases I and II) for the treatment of solid tumors (clinicaltrials.gov). Pre-clinical studies have shown that inhibitors specific to JAKs decreased the in vivo growth of a number of different cancer models including pancreatic, brain, colorectal, gastric, liver, lung, ovarian and breast cancer.39,74 These studies revealed a critical role of JAK1/2 and STAT3 activation in shaping the tumor-promoting microenvironment, including a reduction in tumor angiogenesis, reduced recruitment of tumor-promoting myeloid cells and a reduced metastatic potential.38 These findings further underscore the notion that the contribution of the JAK-STAT3 pathway in tumorigenesis extends beyond its documented effects on tumor cell proliferation and survival. Its implication in shaping the tumor microenvironment and the underlying tumor-promoting inflammatory responses suggest the potential application of JAK inhibitors as a therapeutic approach in virtually all cancers that are driven by a pro-inflammatory microenvironment. As the therapeutic use of JAK inhibitors is still under investigation, their exact molecular mode of activity remains to be thoroughly investigated. It is still unclear whether inhibition of JAK proteins can trigger the initiation/presence of an active anti-tumor response (activation of dendritic cells, M1 monocytes, or anti-tumor effector T cell subtypes). Moreover, as no noted tumor regression was evident after JAK inhibitor administration in solid tumors, the presence of complementary mechanisms cannot be excluded.

Combinatorial therapies

Considering the pivotal role of the immune microenvironment of the tumor in disease promotion, the simultaneous targeting of key pathways, such as STAT3 and NFκB in immune cells may hold therapeutic potential. Efforts are made toward using inhibitors of the JAK-STAT3 pathway—particularly JAK inhibitors—as a therapeutic approach in combination with standard forms of cytotoxic chemotherapies. Although many in vitro studies have demonstrated that concomitant inhibition of the JAK-STAT3 pathway with cytotoxic chemotherapies can promote apoptosis in a variety of cancer-derived cell lines, few in vivo studies have been performed supporting these in vitro findings. As a consequence, combinatorial therapies involving the use of JAK inhibitors are currently under development.75,76 For instance, in gliomas, the percentage of pSTAT3-expressing cells resistant to anti-angiogenic therapy was found to be elevated. The concomitant administration of the JAK inhibitor, ADZ1480 with cediranib (a VEGFR inhibitor) was demonstrated to significantly reduce tumor volume and microvascular density via reduced tumor hypoxia and infiltration of VEGF inhibitor-induced pSTAT3-macrophages.77 Treatment of tumors with cytotoxic drugs (doxorubicin, paclitaxel) and radiation therapy induce necrosis, production of inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-6) and the recruitment of immune cell infiltrates potentially attenuating their therapeutic efficacy.78 Thus, the use of JAK inhibitors is hypothesized to mitigate the inflammatory response and thus increase the overall efficacy of these therapies.

Future Perspectives

We propose that the therapeutic use of IL-6/JAK-STAT3 inhibitors in cancers holds significant promise through the induction of tumor cell death, inhibition of crosstalk between tumor cells and stroma with a reduction in angiogenesis, suppression of tumor-promoting and therapy-induced inflammation. We consider that the simultaneous targeting of several “hallmarks” of cancer and the optimization of relevant combination therapies will lead to improved clinical responses.

Acknowledgments

Our work was supported by grants from the NIH U54: CA148967 (J.B. and G.A.-B.), R01: CA87637 (J.B.), Charles and Marjorie Holloway Foundation (J.B.), Sussman Family Fund (J.B.), Lerner Foundation (J.B.), Astra Zeneca (J.B.), Breast Cancer Alliance (J.B.), Manhasset Women’s Coalition Against Breast Cancer (J.B.), American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association 5th District (E.B.) and The Beth C. Tortolani Foundation (J.B.). We thank the members of our laboratory for helpful discussions and the members of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Molecular Cytology core facilities for the immunofluorescence staining.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Darnell JE., Jr. STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277:1630–5. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bromberg J. Stat proteins and oncogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1139–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI15617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu H, Jove R. The STATs of cancer--new molecular targets come of age. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:97–105. doi: 10.1038/nrc1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sommer J, Effenberger T, Volpi E, Waetzig GH, Bernhardt M, Suthaus J, et al. Constitutively active mutant gp130 receptor protein from inflammatory hepatocellular adenoma is inhibited by an anti-gp130 antibody that specifically neutralizes interleukin 11 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:13743–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.349167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Guo A, Yu J, Possemato A, Chen Y, Zheng W, et al. Identification of STAT3 as a substrate of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase T. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4060–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611665104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He B, You L, Uematsu K, Zang K, Xu Z, Lee AY, et al. SOCS-3 is frequently silenced by hypermethylation and suppresses cell growth in human lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14133–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232790100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koskela HL, Eldfors S, Ellonen P, van Adrichem AJ, Kuusanmäki H, Andersson EI, et al. Somatic STAT3 mutations in large granular lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1905–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine RL, Pardanani A, Tefferi A, Gilliland DG. Role of JAK2 in the pathogenesis and therapy of myeloproliferative disorders. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:673–83. doi: 10.1038/nrc2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berishaj M, Gao SP, Ahmed S, Leslie K, Al-Ahmadie H, Gerald WL, et al. Stat3 is tyrosine-phosphorylated through the interleukin-6/glycoprotein 130/Janus kinase pathway in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R32. doi: 10.1186/bcr1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schafer ZT, Brugge JS. IL-6 involvement in epithelial cancers. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3660–3. doi: 10.1172/JCI34237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grivennikov S, Karin E, Terzic J, Mucida D, Yu GY, Vallabhapurapu S, et al. IL-6 and Stat3 are required for survival of intestinal epithelial cells and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:103–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H, Deng J, Kujawski M, Yang C, Liu Y, Herrmann A, et al. STAT3-induced S1PR1 expression is crucial for persistent STAT3 activation in tumors. Nat Med. 2010;16:1421–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ancrile B, Lim KH, Counter CM. Oncogenic Ras-induced secretion of IL6 is required for tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1714–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.1549407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao SP, Mark KG, Leslie K, Pao W, Motoi N, Gerald WL, et al. Mutations in the EGFR kinase domain mediate STAT3 activation via IL-6 production in human lung adenocarcinomas. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3846–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI31871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sriuranpong V, Park JI, Amornphimoltham P, Patel V, Nelkin BD, Gutkind JS. Epidermal growth factor receptor-independent constitutive activation of STAT3 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is mediated by the autocrine/paracrine stimulation of the interleukin 6/gp130 cytokine system. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2948–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuai K, Liu B. Regulation of JAK-STAT signalling in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:900–11. doi: 10.1038/nri1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stark GR, Darnell JE., Jr. The JAK-STAT pathway at twenty. Immunity. 2012;36:503–14. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DJ, Tremblay ML, Digiovanni J. Protein tyrosine phosphatases, TC-PTP, SHP1, and SHP2, cooperate in rapid dephosphorylation of Stat3 in keratinocytes following UVB irradiation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sekine Y, Tsuji S, Ikeda O, Sato N, Aoki N, Aoyama K, et al. Regulation of STAT3-mediated signaling by LMW-DSP2. Oncogene. 2006;25:5801–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarnicki A, Putoczki T, Ernst M. Stat3: linking inflammation to epithelial cancer - more than a “gut” feeling? Cell Div. 2010;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun DA, Fribourg M, Sealfon SC. Cytokine response is determined by duration of receptor and STAT3 activation. J Biol Chem. 2012;288:2986–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.386573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bromberg JF, Wrzeszczynska MH, Devgan G, Zhao Y, Pestell RG, Albanese C, et al. Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell. 1999;98:295–303. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kujawski M, Kortylewski M, Lee H, Herrmann A, Kay H, Yu H. Stat3 mediates myeloid cell-dependent tumor angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3367–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI35213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K. An epigenetic switch involving NF-kappaB, Lin28, Let-7 MicroRNA, and IL6 links inflammation to cell transformation. Cell. 2009;139:693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iliopoulos D, Jaeger SA, Hirsch HA, Bulyk ML, Struhl K. STAT3 activation of miR-21 and miR-181b-1 via PTEN and CYLD are part of the epigenetic switch linking inflammation to cancer. Mol Cell. 2010;39:493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rokavec M, Wu W, Luo JL. IL6-mediated suppression of miR-200c directs constitutive activation of inflammatory signaling circuit driving transformation and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell. 2012;45:777–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Du H, Qin Y, Roberts J, Cummings OW, Yan C. Activation of the signal transducers and activators of the transcription 3 pathway in alveolar epithelial cells induces inflammation and adenocarcinomas in mouse lung. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8494–503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho PL, Lay EJ, Jian W, Parra D, Chan KS. Stat3 activation in urothelial stem cells leads to direct progression to invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3135–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim DJ, Angel JM, Sano S, DiGiovanni J. Constitutive activation and targeted disruption of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) in mouse epidermis reveal its critical role in UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2009;28:950–60. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barbieri I, Pensa S, Pannellini T, Quaglino E, Maritano D, Demaria M, et al. Constitutively active Stat3 enhances neu-mediated migration and metastasis in mammary tumors via upregulation of Cten. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2558–67. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tebbutt NC, Giraud AS, Inglese M, Jenkins B, Waring P, Clay FJ, et al. Reciprocal regulation of gastrointestinal homeostasis by SHP2 and STAT-mediated trefoil gene activation in gp130 mutant mice. Nat Med. 2002;8:1089–97. doi: 10.1038/nm763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranger JJ, Levy DE, Shahalizadeh S, Hallett M, Muller WJ. Identification of a Stat3-dependent transcription regulatory network involved in metastatic progression. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6823–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bromberg J, Wang TC. Inflammation and cancer: IL-6 and STAT3 complete the link. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:79–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corcoran RB, Contino G, Deshpande V, Tzatsos A, Conrad C, Benes CH, et al. STAT3 plays a critical role in KRAS-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5020–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fukuda A, Wang SC, Morris JP, 4th, Folias AE, Liou A, Kim GE, et al. Stat3 and MMP7 contribute to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma initiation and progression. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:441–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xin H, Herrmann A, Reckamp K, Zhang W, Pal S, Hedvat M, et al. Antiangiogenic and antimetastatic activity of JAK inhibitor AZD1480. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6601–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hedvat M, Huszar D, Herrmann A, Gozgit JM, Schroeder A, Sheehy A, et al. The JAK2 inhibitor AZD1480 potently blocks Stat3 signaling and oncogenesis in solid tumors. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:487–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Azare J, Doane A, Leslie K, Chang Q, Berishaj M, Nnoli J, et al. Stat3 mediates expression of autotaxin in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Studebaker AW, Storci G, Werbeck JL, Sansone P, Sasser AK, Tavolari S, et al. Fibroblasts isolated from common sites of breast cancer metastasis enhance cancer cell growth rates and invasiveness in an interleukin-6-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9087–95. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sansone P, Storci G, Tavolari S, Guarnieri T, Giovannini C, Taffurelli M, et al. IL-6 triggers malignant features in mammospheres from human ductal breast carcinoma and normal mammary gland. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3988–4002. doi: 10.1172/JCI32533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walter M, Liang S, Ghosh S, Hornsby PJ, Li R. Interleukin 6 secreted from adipose stromal cells promotes migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:2745–55. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lederle W, Depner S, Schnur S, Obermueller E, Catone N, Just A, et al. IL-6 promotes malignant growth of skin SCCs by regulating a network of autocrine and paracrine cytokines. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2803–14. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo Y, Xu F, Lu T, Duan Z, Zhang Z. Interleukin-6 signaling pathway in targeted therapy for cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:904–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith C, Chang MY, Parker KH, Beury DW, DuHadaway JB, Flick HE, et al. IDO is a nodal pathogenic driver of lung cancer and metastasis development. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:722–35. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsuyada A, Chow A, Wu J, Somlo G, Chu P, Loera S, et al. CCL2 mediates cross-talk between cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts that regulates breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2768–79. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bochet L, Meulle A, Imbert S, Salles B, Valet P, Muller C. Cancer-associated adipocytes promotes breast tumor radioresistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;411:102–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neiva KG, Zhang Z, Miyazawa M, Warner KA, Karl E, Nör JE. Cross talk initiated by endothelial cells enhances migration and inhibits anoikis of squamous cell carcinoma cells through STAT3/Akt/ERK signaling. Neoplasia. 2009;11:583–93. doi: 10.1593/neo.09266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nefedova Y, Cheng P, Gilkes D, Blaskovich M, Beg AA, Sebti SM, et al. Activation of dendritic cells via inhibition of Jak2/STAT3 signaling. J Immunol. 2005;175:4338–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L, Yi T, Kortylewski M, Pardoll DM, Zeng D, Yu H. IL-17 can promote tumor growth through an IL-6-Stat3 signaling pathway. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1457–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Langowski JL, Zhang X, Wu L, Mattson JD, Chen T, Smith K, et al. IL-23 promotes tumour incidence and growth. Nature. 2006;442:461–5. doi: 10.1038/nature04808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kortylewski M, Xin H, Kujawski M, Lee H, Liu Y, Harris T, et al. Regulation of the IL-23 and IL-12 balance by Stat3 signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:114–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kamiya S, Okumura M, Chiba Y, Fukawa T, Nakamura C, Nimura N, et al. IL-27 suppresses RANKL expression in CD4+ T cells in part through STAT3. Immunol Lett. 2011;138:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wölfle SJ, Strebovsky J, Bartz H, Sähr A, Arnold C, Kaiser C, et al. PD-L1 expression on tolerogenic APCs is controlled by STAT-3. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:413–24. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang J, Liao D, Chen C, Liu Y, Chuang TH, Xiang R, et al. Tumor associated macrophages regulate murine breast cancer stem cells through a novel paracrine EGFR/Stat3/Sox-2 signaling pathway. Stem Cells. 2012;31:248–58. doi: 10.1002/stem.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kortylewski M, Kujawski M, Wang T, Wei S, Zhang S, Pilon-Thomas S, et al. Inhibiting Stat3 signaling in the hematopoietic system elicits multicomponent antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2005;11:1314–21. doi: 10.1038/nm1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kujawski M, Zhang C, Herrmann A, Reckamp K, Scuto A, Jensen M, et al. Targeting STAT3 in adoptively transferred T cells promotes their in vivo expansion and antitumor effects. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9599–610. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tkach M, Coria L, Rosemblit C, Rivas MA, Proietti CJ, Díaz Flaqué MC, et al. Targeting Stat3 induces senescence in tumor cells and elicits prophylactic and therapeutic immune responses against breast cancer growth mediated by NK cells and CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2012;189:1162–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheng F, Wang H, Horna P, Wang Z, Shah B, Sahakian E, et al. Stat3 inhibition augments the immunogenicity of B-cell lymphoma cells, leading to effective antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4440–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herrmann A, Kortylewski M, Kujawski M, Zhang C, Reckamp K, Armstrong B, et al. Targeting Stat3 in the myeloid compartment drastically improves the in vivo antitumor functions of adoptively transferred T cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7455–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kortylewski M, Swiderski P, Herrmann A, Wang L, Kowolik C, Kujawski M, et al. In vivo delivery of siRNA to immune cells by conjugation to a TLR9 agonist enhances antitumor immune responses. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:925–32. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nishimoto N, Kishimoto T. Interleukin 6: from bench to bedside. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:619–26. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wallner L, Dai J, Escara-Wilke J, Zhang J, Yao Z, Lu Y, et al. Inhibition of interleukin-6 with CNTO328, an anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody, inhibits conversion of androgen-dependent prostate cancer to an androgen-independent phenotype in orchiectomized mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3087–95. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dorff TB, Goldman B, Pinski JK, Mack PC, Lara PN, Jr., Van Veldhuizen PJ, Jr., et al. Clinical and correlative results of SWOG S0354: a phase II trial of CNTO328 (siltuximab), a monoclonal antibody against interleukin-6, in chemotherapy-pretreated patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3028–34. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dave B, Landis MD, Dobrolecki LE, Wu MF, Zhang X, Westbrook TF, et al. Selective small molecule Stat3 inhibitor reduces breast cancer tumor-initiating cells and improves recurrence free survival in a human-xenograft model. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ball S, Li C, Li PK, Lin J. The small molecule, LLL12, inhibits STAT3 phosphorylation and induces apoptosis in medulloblastoma and glioblastoma cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu Y, Fuchs J, Li C, Lin J. IL-6, a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma: FLLL32 inhibits IL-6-induced STAT3 phosphorylation in human hepatocellular cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3423–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Turkson J, Jove R. STAT proteins: novel molecular targets for cancer drug discovery. Oncogene. 2000;19:6613–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sen M, Thomas SM, Kim S, Yeh JI, Ferris RL, Johnson JT, et al. First-in-human trial of a STAT3 decoy oligonucleotide in head and neck tumors: implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:694–705. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nelson EA, Walker SR, Kepich A, Gashin LB, Hideshima T, Ikeda H, et al. Nifuroxazide inhibits survival of multiple myeloma cells by directly inhibiting STAT3. Blood. 2008;112:5095–102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-129718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takakura A, Nelson EA, Haque N, Humphreys BD, Zandi-Nejad K, Frank DA, et al. Pyrimethamine inhibits adult polycystic kidney disease by modulating STAT signaling pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4143–54. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quintás-Cardama A, Vaddi K, Liu P, Manshouri T, Li J, Scherle PA, et al. Preclinical characterization of the selective JAK1/2 inhibitor INCB018424: therapeutic implications for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;115:3109–17. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-214957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sun Y, Moretti L, Giacalone NJ, Schleicher S, Speirs CK, Carbone DP, et al. Inhibition of JAK2 signaling by TG101209 enhances radiotherapy in lung cancer models. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:699–706. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820d9d11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Seavey MM, Dobrzanski P. The many faces of Janus kinase. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Greten FR, Karin M. Peering into the aftermath: JAKi rips STAT3 in cancer. Nat Med. 2010;16:1085–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1010-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.de Groot J, Liang J, Kong LY, Wei J, Piao Y, Fuller G, et al. Modulating Antiangiogenic Resistance by Inhibiting the Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 Pathway in Glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1038–46. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fox BA, Schendel DJ, Butterfield LH, Aamdal S, Allison JP, Ascierto PA, et al. Defining the critical hurdles in cancer immunotherapy. J Transl Med. 2011;9:214. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]