Tachykinins and Their Receptors: Contributions to Physiological Control and the Mechanisms of Disease (original) (raw)

Abstract

The tachykinins, exemplified by substance P, are one of the most intensively studied neuropeptide families. They comprise a series of structurally related peptides that derive from alternate processing of three Tac genes and are expressed throughout the nervous and immune systems. Tachykinins interact with three neurokinin G protein-coupled receptors. The signaling, trafficking, and regulation of neurokinin receptors have also been topics of intense study. Tachykinins participate in important physiological processes in the nervous, immune, gastrointestinal, respiratory, urogenital, and dermal systems, including inflammation, nociception, smooth muscle contractility, epithelial secretion, and proliferation. They contribute to multiple diseases processes, including acute and chronic inflammation and pain, fibrosis, affective and addictive disorders, functional disorders of the intestine and urinary bladder, infection, and cancer. Neurokinin receptor antagonists are selective, potent, and show efficacy in models of disease. In clinical trials there is a singular success: neurokinin 1 receptor antagonists to treat nausea and vomiting. New information about the involvement of tachykinins in infection, fibrosis, and pruritus justifies further trials. A deeper understanding of disease mechanisms is required for the development of more predictive experimental models, and for the design and interpretation of clinical trials. Knowledge of neurokinin receptor structure, and the development of targeting strategies to disrupt disease-relevant subcellular signaling of neurokinin receptors, may refine the next generation of neurokinin receptor antagonists.

I. INTRODUCTION

Substance P (SP), the first member of the tachykinin family of peptides, has been called a “pioneering neuropeptide,” since knowledge gained from studies of tachykinins has informed our understanding of many neuropeptides. Indeed, the discovery of SP as an activity in extracts of horse brain and intestine with effects on intestinal contractility and blood pressure marked the identification of the first of many “brain-gut neuropeptides,” which are present in enteric neurons and enteroendocrine cells as well as in neurons of the brain (341). SP belongs to a large family of structurally related peptides, the tachykinins, that derive from alternative processing of three Tac genes. The tachykinins interact with three neurokinin receptors (NKRs) encoded by three Tacr genes. Knowledge of the structure, function, signaling, and trafficking of these receptors has guided studies of other GPCRs and, in this sense, the NKRs may be considered “pioneering receptors.”

The tachykinins are expressed throughout the nervous and immune systems, regulate an extraordinarily diverse range of physiological processes, and have been implicated in important pathological conditions. The realization that tachykinins mediate pathological processes that underlie important human disorders spurred enormous efforts by the pharmaceutical industry to develop NKR antagonists. These efforts have been highly successful. There are multiple NKR antagonists, with varying degrees of selectivity. Many antagonists are effective in preclinical studies of disease in experimental animals. Some have progressed to clinical trials, where the results have been generally disappointing. At present, there is but a single success: the approval of NK1R antagonists to treat nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy or surgery. However, there are many plausible explanations for these failures, including an inadequate understanding of disease mechanisms, the poor predictive value of animal models, and the inherent redundancy of the tachykinin system. Moreover, new information about the participation of tachykinins in disease processes, and a deeper understanding of the NKRs, has served to maintain interest in this field, and multiple clinical trials are still in progress.

In this review, we discuss the contributions of tachykinins and NKRs to pathophysiological control. We summarize the discovery, structure, and function of tachykinins and their receptors, review their roles in major organ systems (gastrointestinal, respiratory, urogenital, dermal, nervous, immune) and pathological processes (inflammation, pain, cancer), and discuss the successes and failures of NKR antagonists in clinical trials. Throughout, we highlight the challenges of defining functions of tachykinins in health and disease and identify key gaps in our understanding of this system. However, the tachykinin literature is vast, and some aspects are not discussed, including the development of antagonists and an in-depth discussion of tachykinins in the central nervous system (reviewed in Ref. 127).

II. TACHYKININ PEPTIDES AND GENES

A. Overview

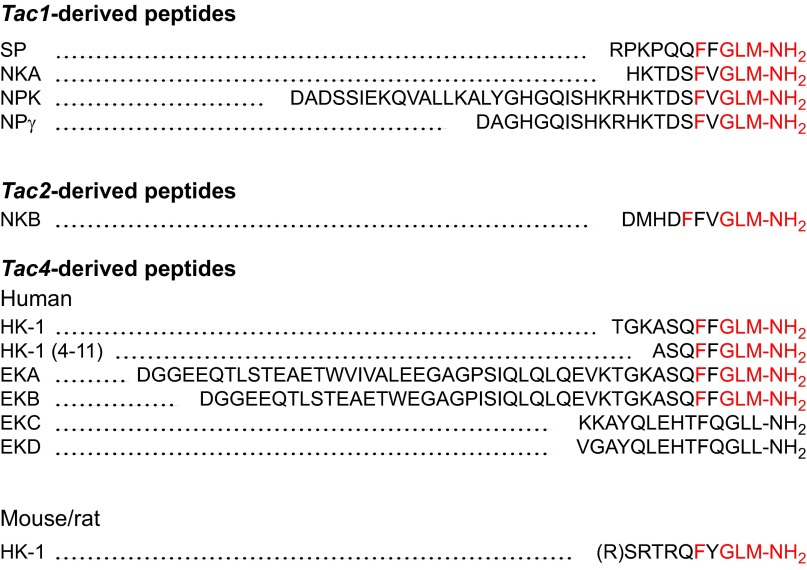

The tachykinins are named for their ability to rapidly stimulate contraction of intestinal muscle, in contrast to the slower acting bradykinins. They possess a conserved COOH-terminal sequence (-Phe-X-Gly-Leu-Met-NH2, X hydrophobic), which is required for receptor activation. The major mammalian tachykinins are SP, neurokinin A (NKA), and neurokinin B (NKB), together with NH2-terminally extended forms of NKA, including neuropeptide K (NPK) and neuropeptide γ (NPγ) (Figure 1). SP, NKA, NKB, and NPK were discovered as biological activities in tissue extracts and were subsequently identified by isolation, sequence, synthesis, and analysis of the Tac genes. Other tachykinins were first identified in the Tac genes, and were subsequently purified from tissues. These include NPγ, hemokinin-1 (HK-1) and the NH2-terminally extended forms of HK-1, endokinin A (EKA), and EKB (Figure 1). Three genes encode the tachykinins: Tac1 (pre-pro-tachykinin-A, Ppt-a), Tac3 (Ppt-b), and Tac4 (Ppt-c) (Figure 2). Tac1 encodes SP, NKA, NPK, and NPγ; Tac3 encodes only NKB; and Tac4 encodes HK-1 and EKA, EKB, EKC, and EKD. Although Tac2 was initially assigned to the gene encoding the NKA precursor, it was subsequently found to be identical to Tac1.

FIGURE 1.

The amino acid sequences of the tachykinins and tachykinin gene-related peptides. Note the presence of the signature tachykinin sequence X-Phe-X-Gly-Leu-Met-NH2 (red) in all of the tachykinins. This sequence is lacking in EKC and EKD, which are not tachykinins although they derive from the Tac4 gene. HK-1 peptides are unique since they differ between mammalian species, whereas other tachykinins are conserved. The existence of an NH2-terminal Arg residue of rat/mouse HK-1 is debatable.

FIGURE 2.

Structures of the human (h) Tac genes and the existence of mRNA splice variants. The peptide products are indicated by the horizontal black bars beneath the mRNA structures. [Adapted from Shimizu et al. (305).]

B. _Tac1-_Derived Tachykinins

1. SP

In the course of investigating the tissue distribution of acetylcholine, von Euler and Gaddum (341) reported the discovery of an activity in extracts of horse intestine and brain that induced atropine-resistant contraction of isolated rabbit jejunum and fall in blood pressure of anesthetized rabbits (Figure 3A). Extraction of tissues with acid and alcohol allowed the preparation of a water-soluble powder that retained high activity and was called “preparation P” and later “substance P.” Activity was highest in intestinal muscle, which contains enteric nerves, and in the brain, suggesting a neuronal origin. Incubation of extracts with trypsin destroyed biological activity, leading von Euler to conclude that “the active principal is of protein nature.”

FIGURE 3.

Landmark events in the history of tachykinins and neurokinin receptors. A: the discovery of substance P (SP). The kymograph tracings show contractions of the rabbit jejunum in response to acetylcholine (a.c.) (A, C) and SP (P) (B, D). The addition of atropine abolished the effects of acetylcholine (C) but not SP (D). [From von Euler and Gaddum (341). Copyright Wiley, Inc.] B: the isolation of SP. The trace of optical density (O.D.) shows the elution profile of extracts of bovine hypothalami, previously fractionated by gel filtration, from a column of carboxy-methyl cellulose. Fractions were assayed for their ability to stimulate salivary secretion in rats (dashed line). [From Chang and Leeman (60). Copyright American Society of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.] C: a snake diagram of the human NK1R. D: the structure of aprepitant, the first NK1R antagonist to be approved for treatment of a human disorder (CINV).

Thirty years after its discovery, SP was identified as peptide from an unrelated line of investigation. While purifying corticotrophin-releasing factor from bovine hypothalamus, Leeman (180) identified fractions that stimulated atropine-resistant salivation in rats. This activity, named sialogen, was destroyed by proteases and had an estimated mass of 8,000–10,000 Da. Shortly thereafter, Lembeck (181) reported that preparations of SP also stimulated salivary secretion and suggested that sialogen and SP were the same. Starting with 20 kg of bovine hypothalami, Chang and Leeman isolated 0.15 mg of pure SP and determined its amino acid composition (Figure 3B) (60) and sequence (61), enabling synthesis of SP with the expected biological activity (337).

2. NKA

NKA (substance K, neurokinin α, neuromedin L), which is highly homologous to SP, was identified as an activity in extracts of porcine spinal cord that stimulated contraction of guinea pig ileum (151) (Figure 1). The existence of NKA was predicted from the Tac1 gene structure (233).

3. NPK

NPK, a 36-amino acid peptide with the COOH-terminal sequence of NKA (Figure 1), was isolated from the porcine brain using methods for detecting COOH-terminal amides of bioactive peptides (332). NPK stimulated gall bladder contraction, plasma extravasation, hypotension, and bronchial smooth muscle spasm. The existence of NPK was predicted from the Tac1 gene (233).

4. NPγ

NPγ, a 21-amino acid peptide, was predicted from the rat Tac1 gene (168) (Figure 1). NPγ was subsequently isolated from the rabbit intestine (142). Like NPK, NPγ is an NH2-terminally extended form of NKA, but NPγ lacks residues 3–17 of NPK (Figure 1).

5. Tac1

Two splice variants of Tac1 (αTac1, βTac1) were first cloned from bovine striatum (233) (Figure 2). Both mRNAs encoded SP. The COOH terminus of SP was followed by Gly, which donates the amide group of the COOH-terminal Met, and Gly was followed by a dibasic Lys-Arg processing site. An Arg-Arg sequence formed the NH2-terminal processing site. Whereas αTac1 encoded SP alone, βTac1 encoded an additional peptide with the tachykinin signature sequence (-Phe-X-Gly-Leu-Met-NH2) and appropriate residues for processing. The peptide was named substance K (NKA) due to homology with amphibian kassinin. Tac1 has been cloned from several species, which confirmed existence of αTac1 and βTac1, and identified the γTac1 and δTac1 splice variants (51, 168). These splice variants lack various exons; encode a combination of SP, NKA, NPK, and NPγ (Figure 2); and are differentially expressed in various tissues.

C. _Tac3_-Derived Tachykinins

1. NKB

NKB (neurokinin β, neuromedin K), which resembles SP and NKA, was isolated from porcine spinal cord as an activity that stimulates contraction of the guinea pig ileum (143) (Figure 1).

2. Tac3

Tac3 was first identified in the bovine as a gene that encoded neuromedin K (NKB) (164). There are two forms of Tac3, both of which encode a single tachykinin, NKB (Figure 2).

D. _Tac4_-Derived Tachykinins

1. HK and EK

The HKs and EKs were discovered by analysis of the Tac4 gene rather than by extraction and bioassays of tissue extracts (Figure 1) (248, 362).

2. Tac4

The appreciation that tachykinins control the myeloid lineage and regulate lymphoid differentiation led to the search for tachykinins in the hematopoietic system (362). A cDNA was identified that encoded an open reading frame of 128 amino acids, including a stretch of 11 amino acids with tachykinin signature sequence flanked by dibasic processing sites and with a Gly adjacent to the COOH-terminal Met. The gene was designated Ppt-c (Tac4), and the peptide named HK-1 to reflect its presence in hematopoietic cells (Figure 1). Although mouse and rat Tac4 are homologous, the human precursor is truncated to 68 amino acids, and human HK-1 differs from the mouse/rat form within the NH2-terminal region. Thus HK-1 differs from the other tachykinins, which are conserved across mammals. Moreover, the human precursor contains two monobasic cleavage sites and has the potential to generate truncated HK-1(4–11) as well as full-length HK-1. Four splice variants of human Tac4 have been identified (α, β, γ, δ), which are generated from a combination of five exons (Figure 2) (248). These splice variants are capable of encoding other peptides, named endokinins in view of their proposed role in endocrine tissues. EKA and EKB are NH2-terminally extended forms of HK-1 and are true tachykinins. As expected, HK-1, EKA, and EKB have SP-like biological actions and can interact with NKRs (248, 362). EKC and EKD lack the tachykinin sequence, have minimal tachykinin-like actions, and show negligible affinity for the NKRs. They are tachykinin gene-related peptides, not tachykinins.

III. NEUROKININ RECEPTORS AND GENES

A. Overview

The first suggestion of multiple receptors for tachykinins came from comparisons of the potencies of mammalian and nonmammalian tachykinins in bioassays. Cloning of three NKRs (NK1R, Tacr1; NK2R, Tacr2; NK3R, Tacr3) confirmed this proposal, representing a major advance in this field. The Tacr genes possess five exons and four introns, which interrupt the protein coding sequences. They encode GPCRs with seven membrane-spanning domains, three extracellular and intracellular loops, and extracellular NH2 and intracellular COOH termini. The availability of the cloned receptors enabled studies of receptor structure, function, and regulation and facilitated the identification of selective antagonists. However, there is still much to learn about this family of receptors, especially the NK2R and NK3R, which have been less thoroughly studied. Importantly, to our knowledge, the crystal structures of the NKRs have not been reported, which would provide key information about receptor activation and signaling.

B. NKR Structure

1. NK1R

The NK1R (SP receptor) was cloned from a rat brain cDNA library by electrophysiological assessment of receptor expression in Xenopus oocytes and cross-hybridization to bovine NK2R (substance K receptor) (355), which had been cloned earlier (203). A clone of 3,408 nucleotides was identified encoding a GPCR of 407 residues (Figures 3C and 4A). When expressed in monkey kidney COS cells, the clone conferred high-affinity binding for SP, that was displaced by SP, NKA, and NKB (IC50 SP > NKA > NKB). Although there is a high degree of similarity of NK1Rs between different species (94.5% identity between rat and human), differences at key residues can affect interaction with antagonists.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of regulation and signaling of the full-length and truncated human NK1R. A: the full-length NK1R is phosphorylated by GRKs and PKC within the COOH terminus and interacts with β-arrestins, which mediate desensitization, endocytosis, and endosomal signaling (75). The receptor activates Ca2+, ERK1/2, NF-κB, and PKC-δ and stimulates IL-8 secretion (175). B: the truncated NK1R lacks most of the COOH terminus, is not phosphorylated, and does not interact with β-arrestins. As a result, it is defective in desensitization and endocytosis and does not assemble β-arrestin signalosomes (75, 183). The truncated receptor does not couple robustly to Ca2+ and NF-κB and inhibits PKCδ phosphorylation and IL-8 secretion (175).

A splice variant of the human and guinea pig NK1R missing exon five encodes a COOH-terminally truncated NK1R of 311 residues that lacks most of the intracellular C-tail (Figure 4B) (19, 98). The truncated human receptor has been detected in monocytes and macrophages (173), discrete brain regions (cortex, cerebellum) (172), and colonic epithelial cells of patients with colitis-associated cancer, where the short form is preferentially upregulated (108). Since the truncated receptor signals differently from the full-length NK1R (see sect. III_C_), this differential expression is of probable functional importance.

2. NK2R

The NK2R (substance K receptor) was the first tachykinin receptor to be cloned. Nakanishi's group used the new approach of expression cloning, in which mRNAs from a bovine stomach cDNA library were expressed in Xenopus oocytes (203). From ∼3 × 105 clones, a single clone was identified that conferred an electrophysiological response to NKA. The 2,458-nucleotide sequence encoded a GPCR of 384 residues. Oocytes expressing this clone responded to tachykinins with a potency ranking of NKA>NKB>SP.

3. NK3R

The NK3R (NMB receptor) cDNA was cloned from rat brain by hybridization with bovine NK2R cDNA, and predicted to encode a GPCR of 452 residues (304). When expressed in Xenopus oocytes, the clone conferred electrophysiological responses to tachykinins, and ligand-binding experiments on membranes from NK3R-expressing COS cells revealed the rank order of potency of NKB > NKA > SP.

C. NKR Signaling

Although NKR signaling has been thoroughly studied, many aspects warrant further attention. First, NKR signaling has been studied mostly in cell lines rather than primary cells, where the intricacies of signaling depend on the level of NKR expression, the compliment of signaling proteins, and the cellular environment. Second, most information derives from studies of high-affinity ligands (SP for NK1R). Since agonists can stabilize distinct GPCR conformations that transmit unique signals (biased agonism, reviewed in Ref. 281), individual tachykinins may signal differently via the same NKR, with diverse outcomes. Third, NKR signaling is usually studied by measuring total cellular levels of second messengers, rather than second messenger generation in subcellular compartments. Compartmentalized signaling can also lead to divergent outcomes, which explains how GPCRs that couple to the same G proteins can transduce specific signals (223). Finally, most studies have examined signaling by full-length unmodified receptors. Variants of the same receptor, which can be generated by alternative splicing or by posttranslational mechanisms, can signal by distinctly different mechanisms. This differential signaling may be important in pathophysiological situations where alternative receptor processing can occur.

1. Initiation of NKR signaling

The major proximal pathways that are activated by tachykinins in NKR-transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) and rat kidney epithelial (KNRK) cells include the following: 1) activation of phospholipase C, leading to formation of inositol triphosphate, which mobilizes intracellular stores of Ca2+, and diacylglycerol, which activates protein kinase C (PKC); 2) activation of adenylate cyclase, resulting in accumulation of cAMP and stimulation of protein kinase A (PKA); and 3) activation of phospholipase A2 and generation of arachidonic acid, a precursor of lipid inflammatory mediators (Figure 5). SP-induced activation of the NK1R in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells also causes a rapid change in morphology, including the formation of blebs in the plasma membrane, which involves the Rho-associated ROCK system and phosphorylation of the myosin regulatory light chain (212). SP-evoked blebbing is not related to apoptosis, which often accompanies blebbing, but rather to formation of microparticles, a mechanism of intercellular communication that has been implicated in disease (63).

FIGURE 5.

Mechanisms of neurokinin receptor signaling from the plasma membrane. 1: SP activation of the NK1R at the plasma membrane initiates G protein-mediated signaling events that include activation of phospholipase C (PLC), formation of inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG), mobilization of intracellular stores of Ca2+, and activation of PKC; activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC), formation of cAMP, and activation of PKA; activation of phospholipase A2 (PLA2), formation of arachidonic acid (AA), and generation of PGs, leukotrienes (LX), and thromboxane A2 (TXA2); and activation of ROCK and phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain (MLC). 2: the NK1R also transactivates the EGFR by a mechanism that involves G protein-dependent activation of members of the a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) domain-containing proteases that cleave and liberate membrane-tethered EGFR agonists. The EGFR dimerizes, phosphorylates (P), and assembles a SHC/Grb2 complex that leads to activation of ERK1/2. There are many interactions between these pathways, and the precise details of activation vary between cell types. 3: NK1R signaling leads to diverse and sometimes cell type-specific effects that include inflammation, proliferation, anti-apoptosis, neuronal excitation, and migration.

SP signaling has been extensively studied in U373MG human astrocytoma cells, which express endogenous NK1R, and in NK1R-transfected NCM460 human colonocytes. In both cell types, SP and the NK1R transactivate the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which leads to activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERK) 1 and 2, DNA synthesis, and proliferation (Figure 5) (54, 158). This mechanism partially mediates the ability of the NK1R to promote healing of the inflamed colonic epithelium (52). Mucosal healing also depends on the anti-apoptotic effect of SP, which involves Janus kinase 2 (JAK-2) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-mediated activation of the anti-apoptotic molecule Akt (protein kinase B) (159). SP also activates Akt in glioblastoma cells (3).

In view of the proinflammatory actions of SP (see sect. IV), NK1R inflammatory signaling has been extensively studied. In U373MG cells, SP and the NK1R activate p38 and generate proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 (79, 94). SP activates the master proinflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) in NCM460 cells by mechanisms that involve activation of Rho family kinases and PKCδ, leading to formation of IL-6, IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (161, 363). SP induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression and prostaglandin (PG) E2 production in these cells via PKC-θ and JAK3/STAT3/5 pathways (160).

In addition to their role in GPCR desensitization and endocytosis, β-arrestins recruit signaling proteins to internalized GPCRs and mediate sustained signaling from endosomes (223). In NK1R-transfected KNRK cells and dermal endothelial cells that naturally express the NK1R, SP induces the assembly of an endosomal signaling complex (signalosome) comprising NK1R, β-arrestin, Src, MEKK, and ERK1/2 (Figure 6) (75). This complex promotes the nuclear translocation of activated ERK1/2, which is necessary for the proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects of SP. The truncated NK1R lacks phosphorylation sites that are necessary for high-affinity β-arrestin interactions, and thus cannot assemble the complex (Figure 4B). Although protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) also assembles β-arrestin-dependent signalosomes, activated ERK1/2 is retained in the cytosol (75). This difference in the subcellular fate of ERK1/2 depends on the affinities of the NK1R and PAR2 for β-arrestins, with PAR2 exhibiting a higher affinity and assembling a more stable complex that retains activated ERK1/2 in the cytosol (251).

FIGURE 6.

Compartmentalized signaling of the NK1R from endosomal membranes. 1: β-Arrestins (β-arrs) recruit the NK1R, Src, MEKK, and ERK1/2 to endosomes and thereby assemble a signalosome that mediates ERK1/2 phosphorylation and activation. β-Arrestin-activated ERK1/2 translocate to the nucleus. 2: Under normal circumstances, ERK1/2 mediate the proliferative and anti-apoptotic actions of SP. 3: When ERK1/2 activation is abnormally sustained, as occurs in cells that lack active ECE-1, ERK1/2 phosphorylate and induce Nur77, which induces cell death.

There are other differences in signaling of the full-length and truncated NK1R. Whereas SP stimulates NF-κB activity and IL-8 expression in cells expressing full-length NK1R, SP stimulation of the truncated receptor inhibits IL-8 expression (Figure 4B) (175). These differences may have implications for tachykinin signaling under pathological conditions where selective upregulation of the truncated receptor is observed (108).

Posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation (see below) and glycosylation, can influence NK1R signaling. The NK1R has two potential sites for _N_-linked glycosylation: Asn-14 and Asn-18. The importance of glycosylation has been examined by expressing a mutated human NK1R lacking these sites in NCM460 colonocytes (331). Mutation prevented NK1R glycosylation, accelerated SP-induced NK1R endocytosis, and suppresses SP-stimulated IL-8 secretion (331). Thus glycosylation stabilizes the NK1R in the plasma membrane and controls proinflammatory signaling. Whether NK1R glycosylation is regulated under pathophysiological conditions is unknown.

The endogenous NK1R signals differently in primary neurons (190). Nociceptive dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons release SP, which mediates neurogenic inflammation and pain (see sect. IV_F_). However, SP can also act in a poorly understood autocrine fashion to activate the NK1R on DRG neurons and sensitize transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), leading to hyperalgesia but not spontaneous pain. Although SP activates PLC in DRG neurons, resulting in PKC-mediated sensitization of TRPV1, it does not robustly elevate intracellular Ca2+. Instead, the NK1R induces a Gi/o-dependent release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidation and activation of M-type K+ channels and consequent neuronal hyperpolarization, which explains why SP does not cause spontaneous pain. Importantly, when overexpressed in neurons, the NK1R induces a robust Ca2+ signal and inhibits M-currents. These results highlight the importance of understanding signaling by endogenous receptors in primary cells.

2. Termination of NKR signaling

GPCR signaling is terminated by mechanisms that remove agonists from the extracellular fluid (reuptake, degradation) and that restrict the capacity of the receptor to couple to signaling machinery (uncoupling, desensitization) (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

The regulation and NK1R signaling and trafficking. 1: The cell-surface peptidase neprilysin (NEP) degrades and inactivates SP in the extracellular fluid and thereby limits NK1R activation. 2: The SP-occupied NK1R is a substrate for GRK 2, 3, and 5, which phosphorylate Ser and Thr residues in intracellular loop 3 and the COOH-terminal tail. Phosphorylation increases affinity of the NK1R for β-arrestins (βarrs), which translocate to the plasma membrane, interact with the NK1R, and mediate G protein uncoupling and receptor desensitization. β-Arrestins also recruit protein phosphate 2A (PP2A), which can dephosphorylate and thereby resensitize the cell-surface receptor. 3: β-Arrestins are adaptor proteins for clathrin and AP2 and thereby promote dynamin-dependent endocytosis of the SP and the NK1R. 4: By recruiting the NK1R together with Src, MEKK, and ERK1/2 to endosomes, β-arrestins assemble signalosomes that allow the endocytosed NK1R to continue to signal. Rab5a mediates trafficking to early endosomes. 5: The NK1R can rapidly recycle from superficially located endosomes by rab4a- and rab11a-dependent mechanisms. 6: Alternatively, the NK1R traffics to endosomes in a perinuclear location that contain ECE-1. ECE-1 degrades SP in acidified endosomes and thereby destabilizes the SP/NK1R/β-arrestin/Src/MEKK and ERK1/2 signaling complex. 7: The NK1R then slowly recycles, which also mediate resensitization (8). 9: After sustained stimulation with high concentrations of SP, the NK1R is ubiquitinated and traffics to lysosomes, where degradation downregulates SP signaling.

Neprilysin is a cell-surface metalloendopeptidase that degrades SP in the extracellular fluid and thereby terminates NK1R activation. Neprilysin disruption suppresses SP degradation and causes widespread NK1R-dependent plasma extravasation (195). Neprilysin-deficient mice are more susceptible to SP-dependent inflammation of the intestine (24, 325) and skin (296), which illustrates the importance of this mechanism of restricting SP signaling.

After stimulation with SP, subsequent responses usually fade (desensitize) and then recover (resensitize). G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) and β-arrestins mediate desensitization of the NK1R (Figure 7). GRK2, GRK3, and GRK5 interact with and can phosphorylate the NK1R (23, 141, 170). The NK1R is extensively phosphorylated, which promotes high-affinity interactions with β-arrestins at the plasma membrane and in endosomes. β-Arrestins sterically uncouple the NK1R from G proteins and desensitize G protein-mediated signaling. The truncated NK1R is resistant to desensitization because it lacks GRK phosphorylation sites and does not interact with β-arrestins (183).

Mechanisms that control NK1R signaling from plasma membranes (SP degradation, NK1R interaction with β-arrestins) similarly control NK1R signaling from endosomal membranes (Figure 7). Endothelin-converting enzyme-1 (ECE-1) is a membrane metalloendopeptidase that degrades SP in endosomes and thereby disassembles the SP/NK1R/β-arrestin/Src signalosome, which attenuates ERK1/2 signaling (68, 259, 285). The importance of this mechanism is illustrated by the finding that ECE-1 inhibition causes sustained SP-induced ERK1/2 activation, leading to activation of the death receptor Nur77 and neurotoxicity (Figure 6) (68).

Resensitization of SP responses requires NK1R endocytosis, dissociation of β-arrestins, and NK1R recycling (see sect. III_D_). However, after stimulation with SP, a substantial proportion of desensitized NK1Rs remain at the plasma membrane, where they resensitize by a mechanism that involves recruitment of protein phosphatase 2A, a β-arrestin binding partner that can dephosphorylate and resensitize the NK1R (Figure 7) (224).

D. NKR Trafficking

NK1R endocytosis is widely used to detect sites of SP release and receptor activation in the nervous system. Although endocytosis is also a key component of signal transduction (223, 342), the importance of NK1R trafficking for signaling in the nervous system is not fully understood.

1. Pathways of NKR trafficking

In NK1R-transfected KNRK and HEK293 cells, SP stimulates rapid NK1R endocytosis (Figure 7) (103, 110, 210). However, the fate of the internalized NK1R depends on the stimulation conditions (286). After brief exposure to low concentrations of SP, the NK1R traffics to rab5a-positive endosomes. Endosomal acidification dissociates SP from the NK1R, SP is degraded in endosomes by ECE-1, and the NK1R recycles (259, 285). After sustained incubation with high SP concentrations, as may occur during inflammation, the NK1R is ubiquitinated and degraded (67). Brief stimulation with SP evokes NK1R endocytosis and recycling in myenteric (109, 316) and spinal (202) neurons.

SP also stimulates NK1R trafficking in vivo. In rats, SP stimulates endocytosis and recycling of the NK1R in endothelial cells of tracheal postcapillary venules, which coincides with desensitization and resensitization of plasma extravasation (41). Stimuli that promote SP release from the central projections of DRG neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, including electrical stimulation of dorsal roots and intraplantar injection of the TRPV1 agonist capsaicin, trigger NK1R endocytosis in neurons in superficial laminae of the dorsal horn (199, 202). Stroking of the mucosa of the guinea pig ileum evokes NK1R endocytosis in myenteric neurons, which suggests that stimulation of enteric afferent mechanoreceptors promotes SP release and NK1R activation (317). Intestinal inflammation causes NK1R endocytosis in myenteric and spinal neurons, which reflects sustained release of SP from primary spinal afferent neurons in the inflamed intestine and dorsal horn (198, 361). Thus NK1R endocytosis occurs under pathophysiological conditions associated with SP release. The endocytosed NK1R has been used to deliver toxins, allowing ablation of NK1R-expressing spinal neurons and determination of their contribution to nociception (200). However, despite the extensive studies of NK1R endocytosis in the nervous system, the functional importance of this trafficking is unknown.

Like the NK1R, the NK2R internalizes and recycles (102). However, in neurons of the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus, endogenous NKB stimulates internalization and trafficking of the NK3R to the nucleus (136). Importins mediate nuclear trafficking of the NK3R, which then associates with transcriptionally active chromatin and thereby controls gene transcription (97, 137).

2. Mechanism and function of NKR trafficking

The NK1R internalizes in cell lines and neurons by a clathrin-dependent mechanism that requires dynamin, rab5a, and β-arrestins (Figure 7) (109, 110, 210, 259, 294). Rab5a also mediates NK1R trafficking to endosomes in a perinuclear location, and rab4a and rab11a mediate NK1R recycling (286, 294). The NK1R has also been detected in lipid rafts of HEK293 cells, suggesting the existence of non-clathrin-dependent trafficking mechanisms (169).

Endocytosis does not mediate NK1R or NK2R desensitization (102), which instead depends on β-arrestins. However, NK1R resensitization requires endocytosis, intracellular processing, and recycling. Thus disruption of the mechanisms of NK1R endocytosis (294) or recycling (286) blocks the resensitization of SP-induced Ca2+ signals. By degrading SP in endosomes, ECE-1 disassembles the NK1R/β-arrestin signalosome, which allows the receptor, freed from β-arrestins, to recycle and resensitize (259, 285). By preventing the NK1R resensitization, ECE-1 inhibitors attenuate SP-stimulated plasma extravasation, which illustrates the importance of NK1R recycling for sustained inflammatory signaling of SP (55).

The NK1R can regulate trafficking and signaling of other GPCRs by mechanisms that include competition of receptors for β-arrestins and physical interactions between receptors. In KNRK cells and enteric neurons, the activated NK1R sequesters β-arrestins in endosomes and thereby impedes β-arrestin-dependent endocytosis and desensitization of the NK3R, which has a low affinity for β-arrestins (293). The activated NK1R similarly blocks agonist-stimulated trafficking of the μ-opioid receptor (356). The NK1R and μ-opioid receptor can also form heterodimers in HEK293 cells, where NK1R activation promotes μ-opioid receptor endocytosis, and delays μ-opioid receptor resensitization, presumably by causing its prolonged retention in endosomes with β-arrestins (261). Whether these complexes assemble in primary neurons is unclear. However, studies in living cells exclude the existence of NK1R homodimers or oligomers of the NK1R and suggest that NK1Rs concentrate in microdomains at the plasma membrane (213).

Conversely, other receptors can control NK1R trafficking. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) delays SP-stimulated endocytosis of the NK1R in T cells of the inflamed intestine (30). Although the mechanism of this effect is unknown, it may be relevant to inflammation because TGF-β amplifies SP-induced inflammatory signaling, and the combination of TGF-β and SP stimulates release of interferon-γ and IL-17 from intestinal inflammatory T cells, whereas either agonist alone has no effect.

E. NKR Expression

The NKR system is remarkably plastic. Alterations in receptor expression influence responses to tachykinins and contribute to pathology, with implications for therapy with antagonists.

1. NK1R

The NK1R is upregulated in the inflamed organs, including in the intestine of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (282), in the pancreas of mice with acute pancreatitis (33), and in mesenteric fat of mice with colitis (144), which may exacerbate the inflammatory effects of SP. However, the NK1R is also upregulated in noninflammatory states, including in spinal neurons of rats during chronic stress (43) and the cingulate cortex of HIV-positive patients (84).

NF-κB is a major regulator of NK1R expression during inflammation. A putative NF-κB binding site was noted in the promoter of the human NK1R gene (327) and was subsequently confirmed experimentally (307). NF-κB mediates IL-12- and IL-18-induced NK1R transcription in splenic T cells (347), IL-1β-stimulated NK1R expression in astrocytes (117), and expression of the truncated NK1R in breast cancer cells (275). SP and the NK1R can in turn activate NF-κB, leading to transcription of proinflammatory genes (26, 161).

The NK1R gene promoter contains putative binding sites for additional transcription factors, including AP-1, Sp1, and Oct-2, which regulate many inflammatory genes (327). Leukemia inhibitory factor, a cytokine of the IL-6 family, promotes NK1R expression in airway epithelial cells by JAK/STAT and MAPK/ERK pathways (128), and JNK upregulates the NK1R in acinar cells during pancreatitis (154). Notably, SP activates the JAK/STAT pathway in colonic epithelial cells leading to PGE2 secretion (160).

2. NK2R

The NK2R is upregulated in the ileum of rats with acute necrotizing enterocolitis (303), and in inflammatory cells in the colon of patients with IBD (282), which may explain the anti-inflammatory effects of NK2R antagonists. In fibroblasts, TGF-β1 and IL-1α stimulate NK2R expression, whereas IL-3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) have the opposite effect (21). Two p53 consensus sequences in the NK2R promoter are critical for the suppressive effects of NKA on the proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells (340).

3. NK3R

There is a complex pattern of NK3R regulation during inflammation. Whereas carrageenan-induced peripheral inflammation reduces responsiveness of spinal dorsal horn neurons to a NK3R agonist (2), intraplantar injection of Formalin or adjuvant upregulates NK3R mRNA expression in the spinal dorsal horn (209).

Alterations in the expression of the NK3R and NKB in the uterus during pregnancy point to important roles in reproduction and reproductive disorders. In the rat placenta, normal late pregnancy is associated with downregulation of NKB and NK3R (249). However, there are marked increases in the circulating concentrations of NKB in individuals with pre-eclampsia, NKB and NK3R levels in the placentas of women with pre-eclampsia are elevated, and NK3R expression in umbilical vein endothelial cells is upregulated in severe pre-eclampsia (193, 250). These results point to a major role of NKB and the NK3R in hypertension and pre-eclampsia, where NK3R blockade is a possible therapy.

Genetic studies suggest an important role for NKB and the NK3R in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in humans. A search for genetic associations that may cause isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism identified four pedigrees of Turkish descent with severe congenital gonadotropin deficiency and pubertal failure, with all affected subjects homozygous for loss-of-function mutations in the NKB or NK3R genes (335). A study of a larger and more ethnically diverse population revealed that mutations of NKB and NK3R occur in ∼5% of a normosmic isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism population (107). Thus NKB and NK3R may be critical regulators of gonadal function.

IV. PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS OF TACHYKININS

A. Overview

Although knowledge of the localization of tachykinins and NKRs and the availability of selective antagonists and mice lacking Tac and Tacr genes have contributed enormously to our understanding, there are formidable challenges to defining the pathophysiological functions of tachykinins. The observation that exogenous tachykinins exert an effect does not imply that endogenous tachykinins have the same actions. Altered tachykinin and NKR expression in disease, and the inherent redundancy of the tachykinin system, with multiple peptides and receptors, can complicate interpretations. There are obvious limitations in extrapolating findings from inbred rodents under controlled conditions to diverse human subjects, and experimental animal models rarely recapitulate human diseases, especially those of unknown etiology. Despite these caveats, there is a wealth of information about the pathophysiological functions of tachykinins. This section discusses the functions of tachykinins in major organs systems (gastrointestinal, respiratory, urogenital, dermal, nervous, immune) and in important pathological processes (inflammation, pain, cancer).

B. Gastrointestinal Tract

The localization and function of tachykinins in the gastrointestinal tract have been reviewed (305). Although tachykinins are found in intestinal immune and enterochromaffin cells, the major sources in the gut are enteric neurons, followed by nerve fibers from dorsal root and vagal ganglia. Tachykinin-containing fibers surround enteric ganglia, ramify through muscle, form a perivascular mesh around submucosal arteries, and supply the mucosa. These fibers are in close proximity to cells expressing NKRs. The NK1R is expressed by enteric neurons, interstitial cells of Cajal, epithelial cells, and lymphocytes and macrophages of the lamina propria; the NK2R is expressed by myocytes, neuronal varicosities, and epithelial cells; and the NK3R is mostly neuronal. The locations of tachykinins and NKRs are consistent with the regulation of neuro-neuronal transmission, motility, secretion, inflammation, and pain.

1. Neuro-neuronal transmission

Evidence for neuro-neuronal transmission, whereby neuronal tachykinins activate NKRs on enteric neurons, derives from studies of receptor trafficking and synaptic transmission. Stimulation of enteric nerves induces endocytosis of the NK1R in myenteric neurons, which requires neuronal conduction, SP and NKA release, and NK1R activation (109, 316). Tachykinins generate slow excitatory postsynaptic potentials in enteric neurons by activating NK1R and NK3R (5).

2. Motility

SP and NKA mediate excitatory transmission via NK1Rs on interstitial cells of Cajal and NK2Rs on smooth muscle (305). In interstitial cells of Cajal, SP activates a nonselective cation channel that controls pacemaker functions (69) and a Na+-leak channel that mediates depolarization (149). Given the importance of interstitial cells of Cajal in motility, targeting these mechanisms could be treatment of motility disorders. HK-1, which is produced by immune cells, contracts circular muscle of mouse colon primarily by activating the neuronal NK1R, with a minor contribution of NK2Rs on myocytes (155). However, in segments of human colon, SP, NKA, and NKB all stimulate contraction of circular muscle by activating the NK2R on colonic myocytes (228).

Mechanical stimulation of the mucosa evokes release of SP and NKA, which partly mediate ascending contraction of peristalsis by NK1R- and NK2R-dependent mechanisms (76). Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor augments SP release to enhances its contractile actions (114). Given the role of SP in peristalsis, defects in tachykinin innervation could contribute to abnormal motility. There is a reduced density of SP-positive fibers in colonic circular muscle of children with slow transit constipation, which could explain the dysmotility (152). Conversely, the density of tachykinin-positive nerve fibers is increased in ileal myenteric ganglia of diabetic guinea pigs, which correlates with enhanced release of acetylcholine and tachykinins, and increased sensitivity of smooth muscle (58).

3. Secretion

Tachykinins stimulate electrolyte and fluid secretion from the intestinal epithelium by activating NKRs on epithelial cells, enteric neurons, or immune cells. This mechanism facilitates propulsion and mediates protective secretory responses to infection. Cryptosporidiosis is a diarrheal disorder caused by the protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum. Although self-limiting in healthy subjects, diarrhea can be severe in immunocompromised patients. SP and the NK1R are upregulated in the jejunal mucosa of macaques infected with C. parvum and mediate increased Cl− secretion and glucose malabsorption (124). Thus NK1R antagonists may be useful to treat the symptoms of cryptosporidiosis and other infections of the intestine.

4. Inflammation

A wealth of evidence implicates tachykinins in intestinal inflammation, including plasma extravasation, granulocyte influx, generation of proinflammatory cytokines, and tissue damage (Figure 8). Inflammation correlates with NK1R activation (see sect. III_D_) and upregulation (see sect. III_E_), and SP and the NK1R activate proinflammatory signaling pathways in colonocytes (see sect. III_C_). NK1R blockade or deletion abrogates intestinal inflammation induced by Clostridium difficile toxin A (53), TNBS (80), and piroxicam in IL-10 knockout mice (348). Tachykinins also participate in the inflammatory responses to infection, including formation of granulomas, sites of chronic inflammation that prevent spread of infectious agents (346). Together, these findings suggest a role of NKR antagonists in intestinal inflammatory diseases (see sect. V_D_).

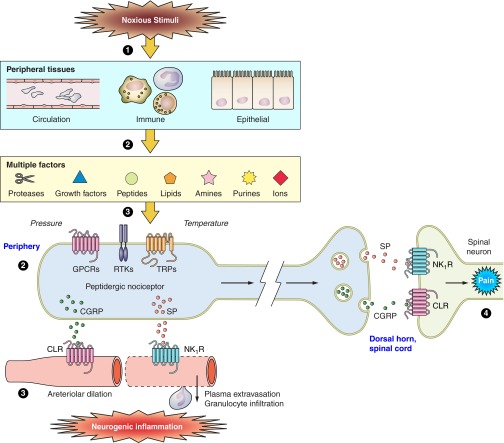

FIGURE 8.

Contributions of tachykinins and neurokinin receptors to neurogenic inflammation and pain. 1: Noxious stimulation of peripheral tissues leads to the release or generation of multiple factors that derive from the circulation, immune cells, and epithelial tissues. These can include proteases (e.g., mast cell tryptase), growth factors (NGF), peptides (bradykinin), lipids (prostaglandins), amines (5-hydroxytryptamine), purines (ATP), ions (protons), pressure, and elevated temperature. 2: These factors can activate several classes of receptors and channels expressed by peptidergic nociceptors, including GPCRs, TRP channels, and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). 3: Activated nociceptors release neuropeptides in peripheral tissues, including SP and NKA, which stimulate NK1Rs on endothelial cells of postcapillary venules and cause plasma extravasation and granulocyte infiltration, and CGRP, which stimulates the calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CLR) on arterioles to cause hyperemia. Together, these changes constitute neurogenic inflammation. 4: If the factors excite nociceptors and generate action potentials, SP and CGRP are also released from the central projections of nociceptors in superficial laminae of the spinal cord dorsal horn, where neuropeptides activate receptors on spinal neurons to transmit painful stimuli centrally.

SP and the NK1R also contribute to the aftermath of inflammation, including fibrosis and healing. The NK1R is expressed by fibroblasts in the chronically inflamed mouse colon and in tissues from patients with Crohn's disease, where SP stimulates collagen synthesis (156). SP also protects colonocytes from apoptosis (159) and promotes expression of cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 in the colonic epithelium, which contributes to healing (157). Consistent with these effects, NK1R deletion hampers healing of the mucosa after chronic colitis (52). Thus SP and the NK1R have dual roles in intestinal inflammation, orchestrating inflammation yet mediating repair. The potential beneficial effects of NK1R antagonists in IBD could, therefore, be offset by disrupted healing of inflamed tissues.

Tachykinins mediate intestinal inflammation induced by activation of TRP channels of primary spinal afferent neurons. The TRPV1 agonist capsaicin induces SP release and NK1R-mediated plasma extravasation in the mouse intestine (96). Components of the inflammatory soup that activate TRP ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) include 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, formed when ROS peroxidate membrane phospholipids (338), and cyclopentenone metabolites of PGD and PGE (204). TRPA1 is expressed by primary sensory nerves innervating the intestine and pancreas, where activation promotes the release of SP and inflammation (56, 59). TNBS, commonly used to evoke inflammation, covalently binds to and activates TRPA1, which stimulates SP release and neurogenic inflammation in the colon (88). Thus TRPA1 antagonists could be a new therapy for colitis.

Mesenteric fat accumulates at sites of intestinal inflammation. In human mesenteric preadipocytes, SP induces NK1R-dependent proinflammatory signals and has proliferative and anti-apoptotic actions that could contribute to development of the mesenteric fat that is characteristic of Crohn's disease (144, 146). SP activation of the NK1R in adipose tissues may mediate pathologies that are associated with obesity, including glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, and NK1R antagonism has anti-obesity effects in mice (145).

Fibrous adhesions within the abdominal cavity invariably occur after surgical manipulation of the intestine. Although usually benign, adhesions can impede transit, lead to visceral pain and female infertility, and complicate further surgery. In line with the proinflammatory actions of SP, NK1R activation during surgical manipulation of the abdominal contents promotes formation of adhesions by limiting fibrinolytic activity, which allows fibrinous adhesions to persist (279). The NK1R antagonist aprepitant reduces adhesion formation in rats, supporting its therapeutic potential (188).

5. Pain

Colitis induces NK1R endocytosis in spinal neurons and nocifensive behavior that are blocked by intrathecal NK1R antagonist, consistent with SP release in the dorsal horn and NK1R activation on spinal neurons that transmit pain (361) (Figure 8) (see sect. III_D_). The NK1R may also be activated in pain-processing areas of the brain of patients with IBD and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (135). A PET analysis of binding of the NK1R-selective ligand [18F]SPA-RQ revealed reduced NK1R binding in cortical and subcortical regions in patients with IBD and IBS. Several processes may account for decreased binding of the NK1R ligand, including release of endogenous SP and activation of the NK1R, displacement of the ligand by endogenous SP, or reduced expression of the receptor. Whatever the mechanism, the results suggest a role for the NK1R in the human brain during pain.

Stress-evoked activation of the NK1R in the spinal cord and intestine contribute to hyperalgesia and motility disorders. The chronic psychological stress of water avoidance in rats upregulates NK1R expression in neurons of superficial laminae in the spinal cord, and induces an NK1R-dependent visceromotor reflex to colorectal distention (42). Spinal microglial cells, p38 MAPK, and NF-κB contribute to these stress-induced changes. Thus water avoidance stress in rats activates spinal microglial cells, as determined by phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in microglial cells in laminae I and II of the spinal cord (43). Intrathecal administration of minocycline (inhibitor of microglial cell activation) suppressed stress-evoked p38 phosphorylation, NF-κB activation, and NK1R upregulation, whereas intrathecal SB203580 (inhibitor of p38 MAPK) blocked stress-evoked NF-κB activation but not NK1R upregulation. Notably, both minocycline and SB203580 suppressed the visceral hyperalgesia in stressed rats. Considered together, these results support a major role for spinal microglial cells and p38 MAPK in NK1R-dependent visceral hyperalgesia (43). Whether activated microglial cells release cytokines that upregulate the NK1R on spinal neurons and cause central sensitization requires further investigation.

C. Respiratory Tract

The contributions of tachykinins to inflammation, hyperreactivity, and secretion of the respiratory system have been reviewed (231). This section reviews recent insights into the debatable importance of tachykinins in the airways.

1. Neurogenic inflammation and airway hyperreactivity

There is a sparse innervation of the airways by peptidergic C- and Aδ-fibers, although nerve terminals containing SP and NKA supply the vasculature, smooth muscle, epithelium, and secretory glands. Although neuropeptide-containing sensory neurons innervating the nose and larynx contribute to sneezing and cough, it is the proinflammatory actions of SP and NKA that provided a major impetus for the development of NKR antagonists to treat inflammatory diseases of the airways.

As in many tissues, SP/NKA stimulate plasma extravasation and granulocyte infiltration in the airways by activating the NK1R in endothelial cells of postcapillary venules. Tachykinins also stimulate secretion from airway seromucous glands (283). Although these neurogenic inflammatory effects of tachykinins occur in the airways of most species, there are marked interspecies differences in the ability of tachykinins to alter tracheo-bronchial smooth muscle tone. In the isolated guinea pig and human bronchus, exogenous SP and NKA produce contraction that is mostly mediated by the NK2R and partly by NK1R, which are coexpressed by myocytes (7, 95). In guinea pigs, SP and NKA also induce relaxation due to activation of epithelial NK1R and release of nitric oxide and prostaglandins, although this effect is masked by the contractile component (95). However, in rats and mice, where the contractile response is absent because NKRs are not expressed by airway smooth muscle, NK1R-mediated epithelium-dependent relaxation prevails (201). After two decades of intense study, a role for endogenous tachykinins and the NK1R in airway hyperresponsiveness in allergen-stimulated mice has been proposed, providing evidence for a major role of SP and the NK1R in allergic hyperreactivity of the airways (123).

In the isolated guinea pig bronchus, electrical field stimulation (EFS) or capsaicin causes nonadrenergic and noncholinergic (NANC) bronchoconstriction that is mediated by tachykinins from sensory nerve endings. However, the situation is completely different in mice and rats, where EFS or capsaicin provoke an epithelium- and tachykinin-dependent bronchodilatation (106). Moreover, in the isolated human bronchus, there is no evidence that capsaicin affects motor functions or that EFS stimulates a NANC contractile and tachykinin-mediated effect. Although inhaled capsaicin causes cough in healthy human subjects that is exaggerated in asthmatic patients (318), there is no evidence that endogenous tachykinins cause bronchoconstriction in humans.

Despite this lack of evidence, the robust observation that exogenous SP and NKA constrict the isolated human bronchus has strengthened the proposal that NKR antagonists are a therapy for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) (see sect. V_E_). However, the finding that exogenous tachykinins cause bronchoconstriction does not imply that endogenous tachykinins have the same effect. The failure of endogenous tachykinins to increase bronchomotor tone in humans may be due to inadequate release of tachykinins, release from nerve fibers supplying cells that are distant from myocytes, or release from immune cells that are resistant to EFS and capsaicin. Whatever the explanation, the findings obtained by using exogenous tachykinins continue to confound our comprehension of the role of endogenous tachykinins in airway diseases.

2. TRP channels

A major advance in our understanding of neurogenic mechanisms of acute inflammation was provided by the report that α,β-unsaturated aldehydes, which are found in cigarette smoke, can activate TRPA1 on peptidergic primary sensory neurons of rodent airways (11). Activated TRPA1 triggers the release of SP and NKA that mediate neurogenic inflammation in response to inhaled cigarette smoke. These results are corroborated by the observations that other components of cigarette smoke, including acetaldehyde and nicotine, can also stimulate TRPA1 (22, 330). Indeed, TRPA1 is a major target of reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and carbonyl species. This unique sensitivity, coupled to the selective expression of TRPA1 by peptidergic nociceptors, suggests that TRPA1 is a neuronal sensor of oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is not only increased in the respiratory tract by environmental agents, such as cigarette smoke, but also occurs at sites of inflammation during the development of asthma (38) and COPD (273). In ovalbumin-sensitized mice, ovalbumin challenge induces airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation that is blunted by deletion of TRPA1 (48). Thus TRPA1 is a neuronal sensor for factors that contribute to asthma and COPD, where activation triggers the release of neuropeptides, including tachykinins, that mediate neurogenic inflammation.

When inhaled, certain volatile anesthetics, including isoflurane and desflurane, induce airway irritation, inflammation and cough that can precipitate laryngospasm during anesthesia. TRPA1 has been implicated in these life-threatening adverse reactions, as it mediates the irritant and inflammatory effects of isoflurane and desflurane (87, 207, 292). NK1R and NK2R antagonists block these inflammatory effects, which depend on TRPA1-dependent release of tachykinins from primary afferent neurons in the airways (87, 207, 292).

The increased prevalence of asthma in infants and children in the last 50 years is a mystery that cannot be explained by the hygiene hypothesis. However, large epidemiological studies have identified an association between the increased prevalence of asthma with the growing use of acetaminophen in pregnant women, infants, and children (28). Although the pathway that links acetaminophen use with asthma is unknown, the _N_-acetyl-_p_-benzo-quinoneimine metabolite of acetaminophen can activate TRPA1 by virtue of its electrophilic nature, thereby provoking neurogenic inflammation of the airways (230). Although clinical doses of acetaminophen may promote moderate and reversible neurogenic inflammation of the airways, repeated use, especially in susceptible individuals with reduced levels of the endogenous ROS scavenger glutathione, may favor the development of the asthmatic phenotype (230). Of relevance for this hypothesis is the suggestion that the ability of _N_-acetyl-_p_-benzo-quinoneimine to stimulate and desensitize TRPA1 is the major mechanism for the analgesic action of acetaminophen (10).

In addition to the established pathway by which reactive molecules initiate tachykinin-mediated neurogenic inflammation in the airways via TRPA1, SP released from sensory nerve terminals increases ROS generation by a NK1R-dependent mechanism. Thus NK1R antagonism reduces ROS formation, epithelial damage, and subsequent remodeling in allergen-challenged guinea pigs (319), and SP induces NK1R-dependent neurogenic inflammation, oxidative stress, and proinflammatory responses in rats (185). Given the role of oxidative stress in thermal injury (221), it is of interest that an NK1R antagonist prevents pulmonary inflammation evoked by local burn injury (311).

Tachykinins may also participate in abnormalities of cough. Coughing subjects have elevated levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and SP in nasal secretions (187). TRPA1 may contribute to abnormal cough since agonists cause cough in guinea pigs and humans (12, 36), and TRPA1 mediates the cough response to cigarette smoke (11). In common with other TRP channels, TRPA1 desensitizes after activation (290). The observations that smoking cessation leads to prompt enhancement of cough sensitivity, even after many years of smoking, and that suppression of cough reflex sensitivity is caused by resumption of cigarette smoking (312), may relate to the ability of cigarette smoke to activate and desensitize TRPA1. Although the role of tachykinins in these phenomena remains to be determined, an enhanced secretion of SP mediated by increased nitrosative stress could contribute to chronic cough hypersensitivity (18).

In addition to neurons, TRPA1 is expressed by airway epithelium, smooth muscle, and fibroblasts, which can contribute to inflammation by releasing cytokines (232). The possibility that tachykinins, which can also release cytokines from airway epithelial cells (165), synergize with TRPA1 to control cytokine production remains to be studied. Moreover, SP expression may not be restricted to sensory nerves, since airway epithelial cells express Tac1 (323), and cells of the hematopoietic lineage can secrete tachykinins. Indirect evidence of this possibility derives from the observation that immune complex-mediated and stretch-induced lung injury are enhanced by the presence of the Tac1 gene in hemopoietic-derived cells (62). Whatever their origin, tachykinins, acting on the NK2R, can activate dendritic cell-mediated type 1 immune responses, thereby increasing the production of IFN-γ and IL-2 production by CD4(+) T cells (153). Overdistension of lung tissue during mechanical ventilation can also evoke cytokine release, and neuronal and nonneuronal SP contributes to ventilator-induced lung inflammation and injury by an NK1R-mediated mechanism (45). In this context, it is not surprising that corticosteroids, the mainstream therapy of asthma, downregulate NK1R expression in airway myocytes of asthmatic rats (184). Remodeling of the sensory innervation of the airways may also contribute to inflammatory diseases. A TNF-α-mediated increase in the levels of nerve growth factor (NGF) results in the proliferation of tachykinin-containing sensory nerve endings (329). NGF also contributes to the tachykinin-mediated responses in rodent airways after ozone inhalation (246), including during early life (131). Finally, in a mouse model of allergic asthma induced by house-dust mite antigen, NGF, primarily expressed in the bronchial and alveolar epithelium, mediates the enhanced release of SP, sensory innervation, and airway hyperresponsiveness (240).

3. Fluid secretion

The mortality of patients with cystic fibrosis is mainly due to chronic bacterial infections of the airway that are favored by the impaired reflex stimulation of mucus secretion from submucosal glands. SP mediates the local responses to capsaicinoids through a mechanism involving coordinated activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator and K+ channels, which eventually results in secretion of fluid from seromucous glands (132). While seromucous glands from noncystic fibrosis patients respond to SP with increased secretion, glands from cystic fibrosis patients are unresponsive to SP (65). Similar findings were obtained in a pig model of cystic fibrosis, where SP was unable to cause glandular secretion (140). Thus defective secretory responses to SP may contribute to the abnormalities in airway secretion that underlie the pathology of cystic fibrosis.

D. Urogenital Tract

The role of tachykinins in urinary and reproductive tracts and the therapeutic potential of NKR antagonists have been reviewed (49, 247).

1. Urinary tract

Primary spinal afferent nerves containing SP and NKA innervate the renal pelvic wall, ureter, and urinary bladder, including the urothelium, muscle, and blood vessels (49). In the wall of the renal pelvis, endothelin 1 (350) and PGE2 (163) stimulate SP release from sensory nerves, whereas angiotensin counteracts the effects of PGE2 (162).

Tachykinins stimulate smooth muscle contraction of the human ureter, mostly by activating the NK2R (138, 227, 255), suggesting the potential use of NK2R antagonists for ureteral disease. In the urinary bladder, the NK1R is found in blood vessels, the urothelium and muscle layers, with some inter-species differences, and the NK2R is expressed by detrusor muscle of all mammalian species studied, including humans (49). In the rat, the NK1R couples to Rho kinase, linking this receptor to smooth muscle contraction (349). Patients with multiple sclerosis have increased density of SP-containing fibers in the urinary bladder, which may contribute to detrusor overactivity in these patients (271). NK1R antagonists are a potential therapy for overactive bladder syndrome in postmenopausal women (299) (see sect. V_F_), whereas NK2R blockade controls neurogenic detrusor overactivity in rats with a spinal cord injury (1).

SP and NK1R have proinflammatory effects in the bladder. In rats, bladder inflammation during early life induces an upregulation of SP that persists into adulthood and is associated with elevated micturition frequency, decreased micturition volume, and enhanced vascular permeability (74, 300). Other proinflammatory actions of SP in the bladder include stimulation of plasma extravasation and leukocyte infiltration, mast cell degranulation, generation of ROS, and expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and cyclooxygenase-2 (49). SP stimulates expression of glucose-regulated protein 78, a receptor for activated α2-macroglobulin, and blockade of this receptor prevents SP-mediated bladder and urothelial inflammation (339). The NK1R mediates the proinflammatory effects of tachykinins in the mouse urinary bladder, since NK1R blockade or deletion attenuates antigen-induced cystitis (291). NK1R antagonists also prevent stress-induced urothelial degeneration and mast cell degranulation in the urinary bladder (89). Thus tachykinins contribute to the clinical manifestations of interstitial cystitis, and NK1R antagonists may be a treatment for inflammatory disorders of the bladder.

There is a high degree of comorbidity between genitourinary and gastrointestinal disorders that are characterized by chronic pelvic pain. For example, colitis in rats is associated with increased expression and release of SP and CGRP in the urinary bladder that requires activation of TRPV1 pathways (253).

2. Female reproductive system

Tachykinins and all NKRs are present in the uterus (57, 256). Their prevalence changes during pregnancy (256) and is regulated by ovarian steroids (263). The NK2R is the predominant tachykinin receptor involved in uterine contraction, and its activation is under tight regulation during pregnancy (260). However, the NK1R in the uterus can mediate inflammatory responses that may lead to abortion (93).

NKB is present in the human placenta, and increased placental levels of NKB and Tac3 could contribute to preeclampsia and hypertension during late pregnancy (249, 250). Although placental levels of NKB increase during normal pregnancy and decline after delivery, they increase even more after preterm labor (336), suggesting that regulation of NKB during pregnancy is important for normal gestation. NKB may induce NK1R-mediated vasodilation of the placenta during pregnancy and cause systemic NK3R-mediated vasoconstriction that leads to hypertension. Elevated NKB levels may be a diagnostic marker for preeclampsia, and NK3R antagonists could be a therapy for this common condition (247).

Within the ovary, tachykinins control steroid secretion and may have an ancient role in stimulating oocyte growth (14). Although tachykinins have been implicated in age-related decline in reproductive function (357), their contribution to control of reproductive capability remains to be fully defined.

3. Male reproductive system

Tac1, Tac3, and Tac4 are expressed by human sperm, and tachykinins increase sperm motility by NK1R- and NK2R-dependent mechanisms (264). Sperm also express the SP-degrading enzyme neprilysin, and neprilysin inhibition promotes motility by inhibiting degradation of endogenous tachykinins (264). The epididymis produces SP, which stimulates sperm motility, and tachykinins potentiate contractility of the vas deferens (49). The importance of tachykinins in testes development is illustrated by the finding of severe testicular atrophy in dogs treated with a mixed NKR antagonist at a young age (194).

The seminal vesicles are innervated by SP-containing fibers, and SP induces contractions and facilitates neurally mediated responses in this system (49). SP and NKA are present at low levels in the rat and guinea pig prostate, abundant in the dog prostate, but absent in humans (49). However, Tac1, Tac3, and Tac4 mRNAs have been detected in human prostate. The effects of tachykinins on prostate contraction involve the NK1R in all species, but NK2R is dominant in human (49).

SP is present in human erectile tissue and penile vessels and can contract human erectile tissue (49). However, its role in erection is unclear, since it has no effects in the cavernous artery and relaxes norepinephrine-induced contractions of corpus cavernosum and corpus spongiosum. NK1R antagonism suppresses ejaculation in rats in response to intraventricular administration of a dopamine D3 receptor agonist (66).

E. Skin

The contribution of tachykinins to homeostasis and diseases of the skin have been reviewed (Figure 9) (287).

FIGURE 9.

Functions of tachykinins in the skin. SP and NKA are released from the peripheral endings of primary sensory nerves in the skin. They act on keratinocytes via NK1R and NK2R to activate NF-κB and promote release of cytokines and chemokines. SP and NKA act within the vasculature to induce plasma extravasation and to upregulate adhesion factors that stimulate neutrophil adhesion and infiltration. During inflammation, SP and NKA activate mast cells, neutrophils, and Langerhans cells, which amplifies the inflammatory response. Centrally released tachykinins contribute to pain and itch transmission.

1. Neuronal tachykinins

SP and NKA are present in primary sensory nerves in the skin (70). Tachykinin-positive nerve fibers supply the dermis and epidermis as well as innervate dermal blood vessels, keratinocytes, mast cells, dendritic cells, and hair follicles. Many exogenous and endogenous factors can stimulate the release of tachykinins from peripheral nerves in the skin, including physical stimuli (heat, ultraviolet radiation, scratching), allergens, and inflammatory mediators (bradykinin, prostaglandins, proteases, cytokines). Other factors, for example, pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide-38, inhibit tachykinin release from cutaneous sensory nerves, in line with their anti-inflammatory effects (236).

2. Keratinocytes

Mouse and human keratinocytes express NK1R and NK2R (Figure 9) (315). The consensus of multiple studies is that SP and NKA control the capacity of keratinocytes to serve as cytokine factories by regulating production of proinflammatory cytokines (315). SP also upregulates NGF production by keratinocytes and may thereby control the regeneration of cutaneous nerves under normal conditions and during wound healing (47). In contrast to CGRP, SP has only a moderate effect on keratinocyte proliferation (284). Neprilysin is expressed by keratinocytes and endothelial cells, where it dampens the actions of tachykinins (245).

3. Cutaneous blood vessels

SP and NKA-positive nerve fibers innervate the vasculature of the superficial dermis, where tachykinins activate the NK1R on endothelial cells of postcapillary venules to stimulate plasma extravasation, granulocyte infiltration, and release of proinflammatory mediators (neurogenic inflammation) (Figure 8). However, endothelial cells can also produce tachykinins, and NGF upregulates SP expression and release from human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (215). Although SP and NKA promote plasma extravasation from postcapillary venules, resulting in edema, recent evidence suggests that while tachykinins maintain basal cutaneous microcirculation, pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide-38 mediates neurogenic inflammatory vasodilation of arterioles and neuropathic mechanical hyperalgesia (40). In human dermal microvascular endothelial cells, SP induces an NK1R-dependent upregulation of adhesion molecules through activation of the transcription factors NF-AT and NF-κB, which leads to the influx of inflammatory cells (269, 270).

4. Fibroblasts

Compared with other tissues, such as the airways, the role of tachykinins in dermal fibroblasts is poorly understood. Human dermal fibroblasts in culture express Tac1, which is upregulated by exogenous SP (17), as well as the NK1R, which is upregulated by interferon-γ (192). Thus tachykinins may regulate fibroblasts by autocrine and neuronal mechanisms to regulate proliferation and wound healing. Indeed, SP induces an NK1R-dependent proliferation of human dermal fibroblasts (129). Human dermal fibroblasts express neprilysin, which is augmented by IL-1β and IL-22 (351). Notably, neprilysin is upregulated in the skin and in ulcers of patients with diabetes, which, combined with the peripheral neuropathy, could contribute to impaired wound healing (13).

5. Dermatitis and pruritus

The peripheral nervous system has long been implicated in the pathophysiology of inflammation and itch in dermatitis. Tachykinins are upregulated in the lesional skin of humans and mice with atopic dermatitis (242). Studies in mice implicate tachykinins and NKRs in the sensitization and inflammatory phases of allergic contact dermatitis. In a model of allergic contact dermatitis in mice, NK1R deletion or antagonism attenuates the sensitization and inflammatory responses to dinitrofluorobenzene (297). SP acting within lymph nodes mediates the sensitization phase (302). Surprisingly, NK2R antagonists enhanced the inflammatory response, whereas NK2R agonists had the opposite effect, suggesting a protective role of for the NK2R. Similarly, repeated SP challenge resulted in an anti-inflammatory response by modulating T cell and dendritic cell function in a chronic stress-induced model of allergic contact dermatitis (258). Whereas neprilysin disruption exacerbates allergic contact dermatitis, it has no effect on irritant dermatitis in mice (296). In summary, the contributions of tachykinins to allergic contact dermatitis are not fully understood, with evidence for pro- and anti-inflammatory functions.

SP is a major mediator of pruritus of atopic dermatitis, and NKR antagonists have been proposed as a therapy for itch (see sect. V_G_). SP induces expression of artemin, a member of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factors, by human dermal fibroblasts, and artemin evokes warmth-evoked scratching and thermal hyperalgesia in mice (222). As a novel therapeutic strategy, ointment containing the nerve repulsion factor semaphorin 3A reduces the density of innervation of mouse skin with SP-containing nerve fibers, attenuates inflammation, and suppresses pruritus in a mouse model of allergic dermatitis (234).

TRP channels of sensory neurons innervating the skin also contribute to inflammation and pruritus of contact dermatitis. Notably, TRPA1 mediates the inflammation and scratching behavior of mice exposed to haptens (oxazolone, urushiol) and the allergen of poison ivy, and SP-induced scratching behavior is not observed in Trpa1 knockout mice (191).

6. Wound healing

Tachykinins have been implicated in wound healing, and deficits in tachykinin innervation (266) and upregulation of neprilysin (13) may contribute to the abnormal wound healing that occurs in patients and animals with diabetes. In a laser-induced wound healing model in rats, exogenous SP was found to promote neurite outgrowth and wound healing (77), and capsaicin also causes a NK1R-dependent increase in NGF biosynthesis in the rat skin (8).

7. Stress-induced hair loss

The hair follicle apparatus expresses tachykinins, NKRs, and endopeptidases, and tachykinins have been implicated in stress- and autoimmune-evoked hair loss. Stress-induced premature induction of catagen and hair follicle apoptosis in mice requires expression of the NK1R and the presence of mast cells (15). Observations of human skin biopsies and hair follicles in culture indicate that SP downregulates production of prolactin, which is important for hair growth (178). SP, NK1R, and neprilysin regulate the inflammatory response in a murine model of alopecia areata, an autoimmune disorder of the hair follicle associated with inflammatory cell influx around growing hair follicles (306).

F. Neurogenic Inflammation and Nociceptive Transmission

Primary sensory neurons innervate most tissues and can release tachykinins from peripheral and central endings to induce neurogenic inflammation and pain transmission. This section discusses the mechanisms and importance of tachykinins in these processes.

1. Tachykinins in primary sensory neurons

The localization of tachykinins in a subset of primary sensory neurons of the trigeminal, dorsal root, and vagal ganglia has been a topic of great interest for the past 60 years since SP and NKA have been proposed to play a major role in transmission at the level of the first synapse in the nociceptive pathway. Tachykinin-containing neurons in sensory ganglia have small cell bodies with unmyelinated C-fibers or thinly myelinated Aδ-fibers and slow conduction velocities. These neurons mediate nociceptive responses to physical (thermal, mechanical) and chemical stimuli. In addition, by releasing neuropeptides from peripheral endings, they generate “neurogenic inflammation,” which includes arteriolar dilatation and plasma extravasation and granulocyte infiltration from postcapillary venules (Figure 8). SP- and NKA-expressing neurons, representing 30–50% of neurons of the rat DRG, coexpress multiple neuropeptides that have been detected by immunochemical techniques. However, convincing evidence for neuropeptide release from the central or peripheral nerve terminals, a prerequisite for physiological function, is available for only a limited number of neuropeptides, notably SP and CGRP (44).

Peptidergic sensory neurons express TRP ion channels, including the thermosensors TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPV3, and TRPV4, the menthol sensor TRPM8, and the irritant sensor TRPA1. Once activated, TRP channels induce release of neuropeptides, including tachykinins. The observation that chronic treatment with the TRPV1 agonist capsaicin depletes neuropeptide from sensory nerve terminals implies that all peptidergic neurons express TRPV1. Moreover, TRPA1-positive neurons are a component of the TRPV1 neuronal population (324), with TRPA1 localized to peptidergic neurons (34). However, a proportion of nonpeptidergic neurons express TRPA1 (150). Mature sensory neuropeptides are produced from pre-pro-hormones synthesized in the neuronal cell body to be transported by active mechanisms to both central and peripheral nerve endings, where they are stored in dense-core vesicles. Neurotrophins, including NGF, regulate the expression of neuropeptides by sensory neurons, as well as the development of the neurons themselves (314).