Long-term seizure remission in childhood absence epilepsy: might initial treatment matter? (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2015 Apr 1.

Published in final edited form as: Epilepsia. 2014 Feb 11;55(4):551–557. doi: 10.1111/epi.12551

Abstract

Objectives:

Examine the possible association between long-term seizure outcome in childhood absence epilepsy (CAE) and the initial treatment choice.

Methods:

Children with CAE were prospectively recruited at initial diagnosis and followed in a community-based cohort study. Children presenting with convulsive seizures, significant imaging abnormalities or who were followed <5 years were excluded. Early outcomes included success of initial medication, early remission, and pharmacoresistance. The primary long-term outcome was complete remission, ≥5 years both seizure and medication-free. Survival methods were used for analyses.

Results:

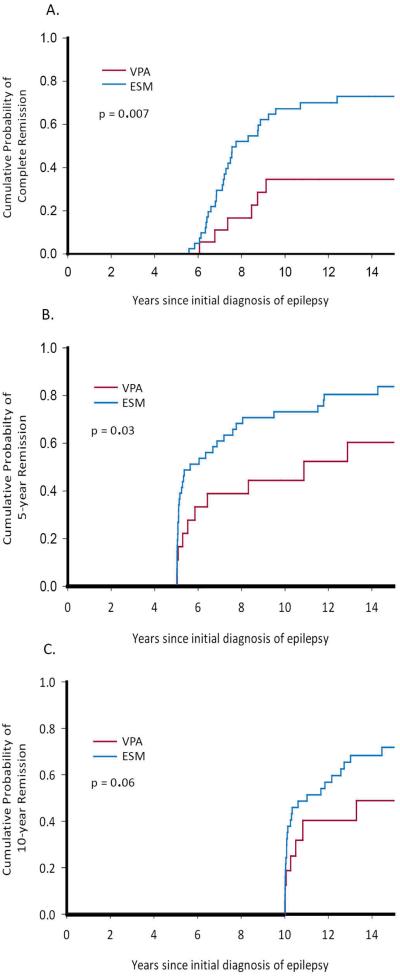

The first medication was Ethosuximde (ESM ) in 41 (69%) and Valproic acid (VPA) in 18 (31%). Initial success rates were 59% (ESM) and 56% (VPA). Early remission and pharmacoresistance were similar in each group. Apart from atypical EEG features (61% (VPA), 17% (ESM )), no clinical features varied substantially between the treatment groups. Complete remission occurred in 31 (76%) children treated with ESM and 7 (39%) who received VPA (p=0.007). Children with versus without atypical EEG features were less likely to enter complete remission (50% vs. 71%, p=0.03). In a Cox regression, ESM was associated with a higher rate of complete remission than VPA (Hazards ration (HR)=2.5, 95% CI 1.1-6.0, p=0.03). Atypical EEG features did not independently predict outcome (p=0.15). Five- and 10-year remission, regardless of continued treatment, occurred more often in children initially treated with ESM versus VPA .

Significance:

These findings are congruent with results of studies in genetic absence models in rats and provide preliminary evidence motivating a hypothesis regarding potential disease modifying effects of ESM in childhood absence epilepsy.

Keywords: Cohort studies, [80] Absence seizures, Anitepileptic drugs, Comparative effectiveness, Disease modification

Childhood absence epilepsy (CAE) is a common form of childhood-onset epilepsy and accounts for approximately 10% of all epilepsies in children 15 years and younger. 1-3 It is generally considered a pharmacologically responsive form of epilepsy, although some children do experience difficulty with seizure control. 4 In about two-thirds, CAE completely remits; 5,6 children can discontinue treatment, and remain seizure-free essentially indefinitely. Because CAE is typically limited to absence seizures, therapy is selected among drugs with known efficacy for that seizure type. In the past, the first line therapies were ethosuximide (ESM), a drug with a narrow spectrum of efficacy almost entirely limited to absence seizures and valproic acid (VPA), a broad spectrum drug which is effective in controlling a large number of different seizure types. 7,8 A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated highly comparable efficacy of ESM and VPA in the short term (3 months, 1 year) for control of absence seizures in children with CAE. 9,10 Animal studies, however, suggested that ESM might have disease modifying properties in two different genetic models of absence epilepsy in rats. 11,12 We hypothesized that a truly “disease modifying” impact of ESM (versus simply seizure suppression), would be seen in long-term epilepsy remission rather than short-term response to medication in children with CAE. To test this hypothesis, we examined complete remission (five years both seizure and drug-free) and other secondary seizure outcomes in children with CAE who were enrolled in a community-based prospective study of epilepsy. The cohort has been followed into adolescence and early adulthood.

Methods

Sample: Study participants were recruited as part of the Connecticut study of epilepsy. This study recruited newly diagnosed patients throughout the State of Connecticut from 1993-1997. Children were identified through the offices of 16 of the 17 practicing child neurologists in the state. All clinical data were initially reviewed by a panel of three pediatric epileptologists as well.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Criteria for diagnosis of CAE were consistent with those published in the standard reference at the time 4 and used in a recent RCT 10 and another recent study. 13 These criteria include ~3hz generalized spike-wave discharges on an EEG with an otherwise normal background, age at onset generally 4-8 years (age is not an absolute criterion and there is variation across studies), and frequent (multiple daily) absence seizures. For this analysis, children who experienced generalized convulsions prior to initial diagnosis of epilepsy, who were treated with a medication other than ESM or VPA, and who had other significant neurological conditions were excluded. Only those followed at least 5 years from date of initial diagnosis, who received either VPA or ESM as their first medication, and who initiated treatment within one month of diagnosis were included in the analysis.

Clinical features

Baseline characteristics that were examined included age at onset, age at diagnosis, gender, and receipt of early special education services prior to diagnosis, which was used as a marker of developmental or cognitive difficulties. Information concerning cognitive function was gathered several years after initial diagnosis of epilepsy.14 We used this as supplemental information regarding whether IQ was 80< or ≥80 further to probe for similarities or differences between the two treatment groups.

Neuroimaging was performed either for clinical purposes or as part an assessment done 8-9 years after study entry. For these analyses, all information was used in determining whether a child had a significant neuroanatomical abnormality or not, and any with such an abnormality, regardless of when found, were excluded. We also used the physician’s order for neuroimaging at initial evaluation as a marker of potential concern on the part of the treating neurologist about atypical presentation.

Atypical features from the initial, diagnostic EEG were obtained from reports and, when feasible, review of original tracings. The reports were specifically reviewed for this analysis (by SRL and FMT) for the presence of any atypical features that might influence choice of treatment or be related to long-term prognosis. This review was performed blinded to initial treatment decision and seizure outcomes. Atypical features included photo-paroxysmal response, polyspike- or irregular spike-wave, unilateral focal findings, and occipital spike wave on eye closure. Atypical features have been proposed to be prognostic of poorer outcome in children with CAE.15-17 Occipital inter-rhythmic delta activity (OIRDA), sometimes considered predictive of better long-term prognosis, 18 was separately identified.

Baseline characteristics were compared to treatment choice to determine if there might be any indication of preferential drug selection based on clinical features. They were also compared to the primary seizure outcome (complete remission) to determine if they were prognostic of long-term remission.

Definitions of seizure and treatment outcomes

All information about seizures and treatments was collected and explicitly recorded prospectively based upon information collected during follow-up calls made every three to four months and from medical records that were reviewed twice a year while the child was under neurological care. When exact dates for seizures or medication changes were not available, we estimated as closely as possible based on the date of last call and any other information the parent provided. For example “in January” was coded as January 15th to minimize errors.

Early seizure outcomes

We studied early remission (achieving and being in ≥1 year remission by 2 years after diagnosis), relapse after entering a one year remission, and pharmacoresistance (failure of informative trials of two different medications, see below). 19

Long-term seizure outcomes

The primary long-term outcome was “complete remission,” both seizure-free and medication-free for at least five years. We also examined 5-year remission at last contact regardless of medication and ten-year remission at last contact in those followed ≥10 years.

Treatment response

The definition of an informative trial of medication was essentially that recently adopted by the ILAE,19 a trial in which the drug is titrated to an intended dose and at least two adjustments upward are made in an effort to achieve control if the targeted dose was inadequate. If the failure to control seizures was due to nonadherence, discontinuation because of idiosyncratic side-effects, or other reasons that precluded an adequate assessment of the seizure control efficacy the trial was considered noninformative, neither a clear failure or a success. Successful initial response to medication required that all seizures have stopped after a reasonable titration period and any needed further adjustments and that seizures remained under full control for at least 1 year. Factors associated with seizure relapse after attaining initial remission were coded as spontaneous (for no apparent cause and with apparently good medication adherence) or as occurring in association with tapering of medication, after tapering was complete, illness, or nonadherence.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted in SAS (SAS 9.3). For simple bivariate associations, chi-square and t-test were used. For seizure outcomes, the log-rank method with associated Kaplan-Meier curves was used for bivariate associations. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to perform multivariable analyses. We specifically tested the association between the initial treatment selected and each of the seizure outcomes defined above. For seizure outcomes, we adjusted for potential confounders. i.e., factors that may determine the outcome and also influence treatment selection.

Ethics

All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of all involved institutions. Parents provided written informed consent and children provided verbal or written assent at study entry. Children who reached the age of majority during the course of follow-up were invited to continue as adults and were asked to provide written consent.

Results

Seventy-three children were initially diagnosed with CAE of whom 68 were followed at least 5 years. We further excluded four children with convulsive seizures by the time of diagnosis, three children who delayed initiating treatment for >1 month after initial diagnosis, one child initially treated with CBZ and one with evidence of an intraventricular hemorrhage on a later research scan. Neuroimaging was available, either from clinical or research imaging, for 49 (83%) of the remaining 59 children included in the analysis and was normal.

Initial treatment choice and seizure outcomes

In the 59 children included in these analyses, ESM was used as the initial treatment in 41 (69%) and VPA in 18 (31%). There were no significant differences between the two treatment groups with respect to most baseline clinical factors or later cognition with the exception that children with atypical EEG features were more likely to receive valproate (p=0.007) (Table 1). None of the baseline characteristics examined in table 1 was significantly associated with complete remission (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical factors in ESM and VPA initial treatment groups.

| ESM (N=41) Mean (SD) or N (%) | VPA (N=18) Mean (SD) or N (%) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset (y) | 5.9 (1.8) | 6.4 (1.8) | 0.40 |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | 6.6 (1.6) | 7.5 (1.6) | 0.05 |

| Age at last contact | 22.1 (3.3) | 21.2 (3.8) | 0.35 |

| Male | 19 (46%) | 8 (44%) | 0.89 |

| IQ ≥80 | 35 (85%) | 15 (83%) | 0.84 |

| Services prior to diagnosis** | 9 (23%) | 5 (28%) | 0.70 |

| No baseline imaging performed | 25 (61%) | 9 (50%) | 0.43 |

| Inter-rhythmic delta activity | 6 (15%) | 5 (28%) | 0.23 |

| Atypical EEG features*** | 7 (17%) | 11 (61%) | 0.0007 |

Table 2.

Baseline clinical factors in relation to complete remission at last contact

| Not in complete remission (N=21) Mean (SD) or N (%) | In complete remission (N=38) Mean (SD) or N (%) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset (y) | 6.2 (2.0) | 6.0 (1.7) | 0.68 |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | 7.0 (1.8) | 6.8 (1.5) | 0.54 |

| Age at last contact | 20.4 (3.9) | 22.7 (2.9) | 0.01 |

| Male | 7 (33%) | 20 (53%) | 0.15 |

| IQ ≥80 | 16 (76%) | 34 (89%) | 0.17 |

| Services prior to diagnosis** | 5 (26%) | 9 (24%) | 0.83 |

| No baseline imaging performed | 14 (67%) | 20 (53%) | 0.30 |

| Inter-rhythmic delta activity | 4 (19%) | 7 (18%) | 0.95 |

| Atypical EEG features*** | 9 (43%) | 9 (24%) | 0.13 |

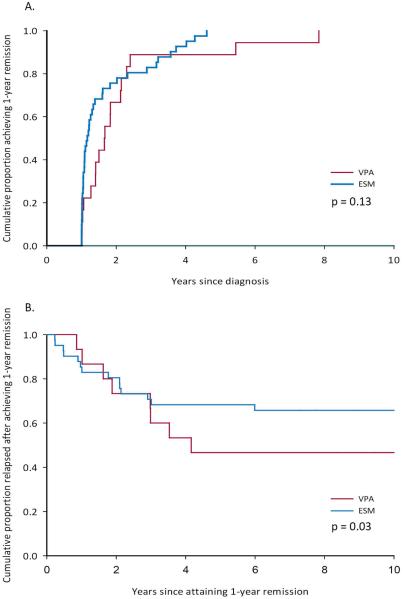

Early outcomes and responses to treatment were similar in the two treatment groups (Table 3). All children experienced ≥1 year remission (figure 1a). Remission by two years after diagnosis and the occurrence of pharmacoresistance were comparable in the two treatment groups. There was a tendency for more children in the VPA (61%) than ESM (34%) group to experience relapse however (p=0.05, Figure 1b). Reasons associated with relapse did not appear to differ greatly based on initial treatment (Table 3). During the course of follow-up, two children developed juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, one in each initial treatment group.

Table 3.

Response to initial treatment and seizure outcomes

| ESM (N=41) Mean (SD) or N (%) | VPA (N=18) Mean (SD) or N (%) | p-value+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Success with first AED | 24 (59%) | 10 (56%) | 0.83 |

| Years to 1 year remission (yrs) | 1.7 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.7) | 0.31 |

| Years to 1 year remission if first drug was successful | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.5) | 0.57 |

| In 1 year remission by 2 years | 28 (68%) | 10 (56%) | 0.35 |

| Pharmacoresistance | 3 (7%) | 4 (22%) | 0.10 |

| Relapse after 1st ≥1 year remission | 14 (34%) | 11 (61%) | 0.05** |

| Reasons associated with relapse | ns | ||

| Spontaneous | 2 (14%) | 6 (56%) | |

| Tapering | 0 | 1 (9%) | |

| Medication completely stopped | 8 (57%) | 3 (27%) | |

| Illness/nonadherence/other | 4 (29%) | 1 (9%) | |

| Complete remission | 31 (76%) | 7 (39%) | 0.007** |

| 5 year remission +/− AEDs | 35 (85%) | 10 (56%) | 0.03** |

| 10-year remission* | 28 (76%) | 7 (44%) | 0.06** |

Figure 1.

A. Time to 1-year remission and B. Time to subsequent relapse after 1-year remission for children whose initial treatment was ESM versus VPA.

At the time of last follow-up contact 38/59 (64%) of participants were in complete remission (5 years seizure free and 5 years off medication), 31 (76%) of those first treated with ESM and 7 (39%) of those treated with VPA (p=0.007, Figure 2a). Five-year remission at last contact (regardless of medication) also differed between ESM and VPA groups (85% vs 56%, p=0.03, Figure 2b). In 53 children followed ≥10 years, ten-year remission was also higher in the ESM (76%) versus VPA (44%) group (p=0.06, Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Long-term seizure outcomes at last contact in children with CAE initially treated with ESM and VPA. A. Complete remission (five years seizure and medication-free. B. Five-year remission regardless of treatment at last contact. C. Ten-year remission at last contact.

Atypical EEG features

Complete remission occurred in 29 (71%) of children without atypical EEG features and 9 (50%) of those with atypical features (p=0.03, log rank test). Stratification of the data by the presence of atypical EEG features revealed a consistent association between outcome and initial treatment separately in those with and without atypical features (Table 4a); there was a trend for a higher proportion of patients to achieve complete remission if first treated with ESM versus VPA regardless of the presence or absence of atypical EEG features. Stratification by initial treatment, however, revealed no independent association between the outcome and presence of atypical features (Table 4b); presence of atypical EEG features had no association with outcome when separately considering those patients initially treated with ESM and those initially treated with VPA.

Table 4.

A. Association of initial treatment choice and complete remission stratified on the presence of atypical EEG features and B. Association of atypical features with outcome stratified on initial treatment choice

| A. Atypical EEG features absent | Not in Complete remission | Complete remission | p-value (based on chi- square) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM | 8 (24%) | 26 (76%) | 0.08 |

| VPA | 4 (57%) | 3 (43%) | |

| Atypical EEG features present | |||

| ESM | 2 (29%) | 5 (71%) | 0.15 |

| VPA | 7 (64%) | 4 (36%) | |

| B. Initially treated with ESM | |||

| Atypical features absent | 8 (24%) | 26 (76%) | 0.78 |

| Atypical feature present | 2 (29%) | 5 (71%) | |

| Initially treated with VPA | |||

| Atypical features absent | 4 (57%) | 3 (43%) | 0.78 |

| Atypical feature present | 7 (64%) | 4 (36%) |

Multivariable Analysis

In a multivariable proportional hazards regression which takes into account length of follow-up and time to event, use of ESM as the first medication was associated with a higher rate of complete remission relative to VPA (Hazard ratio (HR) = 2.5, 95% CI 1.1 to 6.0, p=0.03) after adjustment for atypical EEG features (HR=0.6, 95% CI 0.2, 1.3, p=0.15). Removal of atypical EEG features, which was not statistically significant, did not substantially change the results for treatment choice (HR for ESM = 3.0, 95% CI 1.3, 6.9, p=0.01). When tested in a multivariable model, no other baseline clinical factors were associated with complete remission or could explain the difference in long-term outcome between children initially treated with VPA and ESM.

Discussion

Our observational results regarding early response to ESM and VPA are entirely consistent with the findings of a definitive head-to-head RCT that concluded ESM and VPA to be comparably effective for seizure control in CAE at 3 months and 1 year. 9,10 They further strengthen and complement the trial findings as our study represents the results of community practice and not the highly selected patient groups who generally enter randomized trials. Our findings also suggest, however, that the long-term seizure outcomes may differ as a function of the initial treatment used. Children who initially received ESM were less likely to experience subsequent relapses for any reasons compared to children who received VPA. After ≥5 years of follow-up, children initially treated with ESM were more likely to be at least 5-years seizure free at last follow-up. Specifically, they were much more likely to be in complete remission (both 5-years seizure-free and medication-free). The difference appeared present even for ten-year remission.

In a non-randomized study such as ours, there are bound to be concerns over confounding by indication: i.e., patients with a known poor prognosis are preferentially given one treatment whereas patients with a better prognosis are preferentially given a different treatment. Any differences in outcomes between the two treatment groups could thus be attributable to baseline differences between the patients in those groups.20 For these reasons, we a priori excluded children with convulsive seizures for whom the preferred drug would have been VPA. We also considered evidence of school difficulties (special education prior to diagnosis), low IQ, and ordering of neuroimaging at initial diagnosis (as indications of heighted concerns), family history of epilepsy, age at onset, and age at diagnosis. None of these factors was associated with treatment selection or seizure outcome. The only factor associated with treatment selection was atypical EEG features.

Atypical features have been discussed by experts in the field as important prognostic factors in CAE with some suggesting that they be considered exclusion criteria. 15,16 One study reported atypical features to predict poorer outcomes in a large, heterogeneous range of epilepsies in which absence seizure occurred with age at onset from 0-15 years. The series also included individuals with convulsive seizures.21 Thus, while in a broader sample of all children with any kind of absence seizure, atypical features may be common in subgroups with poorer outcomes, these other subgroups do not meet criteria for children with the electro-clinical syndrome of CAE. A second study reported atypical features (as we have also defined them) to be associated with a poorer outcome.17 This study targeted a clinical group that more closely resembled CAE but still included patients whom we would have excluded. It was not clear whether atypical features were prognostic factors within subgroups of patients already excluded from our series (e.g. with other seizure types) or whether they did in fact predict long-term prognosis in children otherwise meeting criteria for CAE. The authors also indicated a strong preference for the use of VPA in that series. Overall, there is little evidence that “atypical” features are prognostic of long-term outcome in CAE, as defined by commonly accepted criteria. A recent series of articles demonstrated that these features occur frequently in CAE but do not meaningfully help define the syndrome itself. 13,22,23 In the end, we found, in our fairly “pure” series that, while atypical EEG features were strongly associated with the choice of the initial drug, they were only modestly associated with long-term seizure outcomes and no longer associated after adjustment for initial treatment.

At the time these children were recruited, there was no literature on the comparative effectiveness of these two drugs so other than the potential concern regarding progression to JME with multiple seizure types not controlled by ESM, it is unclear what other subtle biases would exist that we have not already addressed as there were, at the time, and still are no data to guide treatment decisions in this regard.

Our findings suggest a hypothesis, that ESM might have disease modifying properties and may have an impact on the long-term course of CAE. Recent experiments in two different genetic rat models of absence epilepsy provide support for this hypothesis. 11,12 In these absence models, early treatment with ESM during development reduced the incidence of spike-wave seizures even long after the medication was discontinued. Because the treatment also prevented activity-dependent dysregulation of ion channels and epigenetic changes in DNA-methylation it was proposed that ESM may suppress epileptogenesis in this form of epilepsy. Beyond improvement of seizure outcome, disease-modifying treatment has the potential to improve known absence epilepsy co-morbidities such as impaired attention and emotional function. 10,24-26 Indeed, at least in the animal models, early intervention with ESM was shown to prevent anxiety and depressive behaviors associated with this form of epilepsy. 12,27

As acknowledged, the study was not randomized. Randomized controlled trials have severe limitations, however. For example, they rarely are representative of the target population or the large population to which the results maybe be applied. Further, they are often limited to studying short term, surrogate outcomes. Complete remission after 10-15 years would be a difficult a priori outcome for a RCT. Information RCTs can be and often is complemented by data from multiple sources. The term “comparative effectiveness” encompasses a range of clinical research endeavors that include but are not limited to RCTs.28 These different approaches, including observational and qualitative studies, can help fill in gaps left by many RCTs. Further, comparison of well-controlled observational studies to RCTs has shown that observational studies, when carefully considered, yield answers that are comparable to those obtained in randomized trials. 29 Although we would like to see our findings tested independently by others, they represent an initial first step toward examining the potential disease modifying effect of ESM in this setting. We note that that short-term outcomes, the typical target of RCTs, may not be adequate for studying this phenomenon.

EEG tracings, while often centrally read, were not always. Most were recorded on paper and can no longer be retrieved. Regardless, what was written in the reports is what was available to the treating clinicians and was the information that they used when making medications decisions.

VPA is clearly an excellent drug for the treatment of many seizure types and forms of epilepsy and is a drug of choice in many patients with multiple seizure types. By contrast, ESM’s use is narrowly restricted to treatment of absence seizures. 7,8 Children with CAE usually have only absence seizures. ESM, in the short term, now has class I evidence supporting its use over LTG for seizure efficacy and over valproate due to its cognitive profile but not seizure efficacy. 9,10 Whether benefits extend to the long-term is an important question raised by our findings. A definitive study would take years to perform. Our findings, which fall into the growing tradition of comparative effectiveness research28, provide clinical evidence to support the novel hypothesis suggested in laboratory studies that there may be disease modifying properties specific to ESM in the treatment of CAE.

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Acknowledgments

Study Funding: supported by NINDS R37-NS31146

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Dr. Berg performed all analyses, drafted the original manuscript, and participated in revising the manuscript and producing the final draft.

Dr. Levy participated in the review of EEG and characterization of electrographic features, and in critically reviewing and revising the manuscript and in producing the final draft.

Dr. Testa participated in the review of EEG and characterization of electrographic features, and in critically reviewing and revising the manuscript and in producing the final draft.

Dr. Blumenfeld participated in drafting sections of the manuscript and in critically reviewing, revising, and producing the final manuscript.

Disclosures:

Dr. Berg has received speaker honoraria and travel support from BIAL and MUSC, travel support from the ILAE, an authorship honorarium from CONTINUUM, serves on advisory boards for CURE and Eisai, serves on the editorial boards of Epilepsy & Behavior and Neurology, and is supported by funding from the NINDS (Grant R37-NS31146) and the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation.

Dr. Levy reports no disclosures.

Dr. Testa reports no disclosures.

Dr. Blumenfeld reports no disclosures.

References

- 1.Berg AT, Mathern GW, Bronen RA, et al. Frequency, prognosis and surgical treatment of structural abnormalities seen with magnetic resonance imaging in childhood epilepsy. Brain. 2009;132:2785–97. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callenbach PMC, Geerts AT, Arts WFM, et al. Familial Occurrence of Epilepsy in Children with Newly Diagnosed Multiple Seizures: Dutch Study of Epilepsy in Childhood. Epilepsia. 1998;39:331–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camfield P, Camfield C. Nova Scotia pediatric epilepsy study. In: Jallon P, Berg A, Dulac O, Hauser A, editors. Prognosis of epilepsies. John Libbey; Montrouge France: 2003. pp. 113–26. Eurotext. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roger J, Bureau M, Dravet C, Dreifuss FE, Perret A, Wolf P. Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood, and adolescence. 2nd John Libbey; London: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouma PAD, Westendorp RGJ, van Dijk JG, Peters ACB, Brouwer OFM. The outcome of absence epilepsy: A meta-analysis. Neurology. 1996;47:802–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.3.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loiseau P, Pestre M, Datigues JF, Commenges D, Barberger-Gateau C, Cohadon S. Long-term prognosis in two forms of childhood epilepsy: Typical absence seizures and epilepsy with rolandic (centrotemporal) EEG foci. Annals of Neurology. 1983;13:642–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glauser T, Ben-Menachem E, Bourgeois B, et al. Updated ILAE evidence review of antiepileptic drug efficacy and effectiveness as initial monotherapy for epileptic seizures and syndromes. Epilepsia. 2013;54:551–63. doi: 10.1111/epi.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glauser TA, Loddenkemper T. Management of Childhood Epilepsy. Contunuum. 2013;19:656–81. doi: 10.1212/01.CON.0000431381.29308.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glauser TA, Cnaan A, Shinnar S, et al. Ethosuximide, valproic acid, and lamotrigine in childhood absence epilepsy: Initial monotherapy outcomes at 12 months. Epilepsia. 2013;54:141–55. doi: 10.1111/epi.12028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glauser TA, Cnaan A, Shinnar S, et al. Ethosuximide, Valproic Acid, and Lamotrigine in Childhood Absence Epilepsy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362:790–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumenfeld H, Klein JP, Schridde U, et al. Early treatment suppresses the development of spike-wave epilepsy in a rat model. Epilepsia. 2008;49:400–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dezsi G, Ozturk E, Stanic D, et al. Ethosuximide reduces epileptogenesis and behavioral comorbidity in the GAERS model of genetic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2013;54:635–43. doi: 10.1111/epi.12118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadleir LG, Farrell K, Smith S, Connolly MB, Scheffer IE. Electroclinical features of absence seizures in childhood absence epilepsy. Neurology. 2006;67:413–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228257.60184.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg AT, Langfitt JT, Testa FM, et al. Global cognitive function in children with epilepsy: A community-based study. Epilepsia. 2008;49:608–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loiseau P, Panayiotopoulos C. Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood and adolescence. 3rd John Libbey & Co; Eastleigh: 2002. Childhood absence epilepsy and related syndromes; pp. 285–303. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panayiotopoulos C, Obeid T, Waheed G. Differentiation of typical absence seizures in epileptic syndromes. Brain. 1989;112:1039–56. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.4.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grosso S, Galimbert D, Vezzosi P, et al. Childhood absence epilepsy: evolution and prognostic factors. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1796–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomez MR, Westmoreland BF. Absence seizures. In: Luders H, Lesser RP, editors. Epilepsy: electroclinical syndromes. Springer-Verlag; London: 1987. pp. 105–29. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: Consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1069–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sackett DL. Bias in analytic research. J Chron Dis. 1979;32:51–63. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(79)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedström A, Olsson I. Epidemiology of absence epilepsy: EEG findings and their predictive value. Pediatric Neurology. 1991;7:100–4. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(91)90004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadleir LG, Scheffer IE, Smith S, et al. Factors influencing clinical features of absence seizures. Epilepsia. 2008;49:2100–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadleir LG, Scheffer IE, Smith S, Carstensen B, Farrell K, Connolly MB. EEG features of absence seizures in idiopathic generalized epilepsy: Impact of syndrome, age, and state. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1572–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Killory BD, Bai X, Negishi M, et al. Impaired attention and network connectivity in childhood absence epilepsy. NeuroImage. 2011;56:2209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vega C, Guo J, Killory B, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in childhood absence epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011;52:e70–e4. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wirrell EC, Camfield CS, Camfield PR, Dooley JM, Gordon KE, Smith B. Long-term psychosocial outcome in typical absence epilepsy: Sometimes a wolf in sheeps' clothing. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1997;151:152–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170390042008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarkisova KY, Kuznetsova GD, Kulikov MA, Van Luijtelaar G. Spike–wave discharges are necessary for the expression of behavioral depression-like symptoms. Epilepsia. 2010;51:146–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vickrey BG, Hirtz D, Waddy S, Cheng EM, Johnston SC. Comparative effectiveness and implementation research: Directions for Neurology. Annals of Neurology. 2012;71:732–42. doi: 10.1002/ana.22672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Eng J Med. 2000;342:1887–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]