E-cigarettes and conventional cigarette use among US adolescents: A cross-sectional study (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2014 Aug 23.

Abstract

Importance

E-cigarette use is increasing rapidly among adolescents and e-cigarettes are currently unregulated.

Objective

Examine e-cigarette use and conventional cigarette smoking.

Design

Cross-sectional analyses of survey data.

Setting

2011 and 2012 National Youth Tobacco Surveys (NYTS)

Participants

Representative sample of US middle and high school students in 2011 (n=17,353) and 2012 (n=22,529)

Exposures

Ever and current e-cigarette use

Main outcome measures

Experimentation with, ever, and current smoking; smoking abstinence

Results

In pooled analyses, among cigarette experimenters (≥1 puff), ever e-cigarette use was associated with higher odds of ever smoking cigarettes (≥100 cigarettes; OR= 6.31, 95% CI [5.39-7.39) and current cigarette smoking (OR=5.96 [5.67-6.27]). Current e-cigarette use was positively associated with ever smoking cigarettes (OR=7.42 [5.63-9.79]) and current cigarette smoking (OR= 7.88 [6.01-10.32]. In 2011, current cigarette smokers who had ever used e-cigarettes were more likely to intend to quit smoking within the next year (OR=1.53 [1.03-2.28]). Among experimenters with conventional cigarettes, ever use of e-cigarettes was also associated with lower 30-day (OR=0.24 [0.21-0.28]), 6-month (OR=0.24 [0.21-0.28]), and 1-year (OR=0.25 [0.21-0.30]) abstinence from cigarettes. Current e-cigarette use was also associated with lower 30-day (OR=0.11 [0.08-0.15]), 6-month (OR=0.11 [0.08-0.15]), and 1-year (OR=0.12 [0.07-0.18]) abstinence. Among ever smokers of cigarettes (≥100 cigarettes), ever e-cigarette use was negatively associated with 30-day (OR=0.61, [0.42-0.89]), 6-month (OR=0.53, [0.33-0.83]) and one-year (OR=0.32 [0.18-0.56) abstinence from conventional cigarettes. Current e-cigarette use was also negatively associated with 30-day (OR=0.35 [0.18-0.69]), 6-month (OR=0.30 [0.13-0.68]), and one-year (OR=0.34 [0.13-0.87]) abstinence.

Conclusions

E-cigarette use was associated with higher odds of ever or current cigarette smoking, higher odds of established smoking, higher odds of planning to quit smoking among current smokers, and, among experimenters, lower odds of abstinence from conventional cigarettes.

Relevance

Results suggest e-cigarette use does not discourage, and may encourage, conventional cigarette use among US adolescents.

INTRODUCTION

E-cigarettes are devices that deliver a heated aerosol of nicotine in a fashion that mimics conventional cigarettes, while delivering lower levels of toxins than a conventional combusted cigarette.1-4 E-cigarettes are being aggressively marketed using the same messages and media channels (plus the internet) that cigarette companies used to market conventional cigarettes in the 1950s and 1960s,5 including on television and radio where cigarette advertising has been prohibited for more than 40 years.

In addition to these traditional media, e-cigarettes have established a strong advertising presence on the internet, and e-cigarette companies heavily advertise their products through electronic communication. Studies have demonstrated for decades that youth exposure to cigarette advertising causes youth smoking.6 E-cigarettes are also sold using characterizing flavors (e.g., strawberry, licorice, chocolate) that are banned in cigarettes in the United States because they appeal to youth. The 2011 and 2012 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) revealed that e-cigarette use among youth in grades 6 through 12 doubled between 2011 and 2012 from 3.3% to 6.8%.7 As with adults,7-10 concurrent dual use of e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes was also high, with 76.3% of current e-cigarette users reporting concurrent use of conventional cigarettes in 2012.7 Likewise, e-cigarettes were introduced to Korea in 2007 using similar marketing techniques as those used in the US, and use among adolescents rapidly increased: in 2011, 4.7% of Korean adolescents were using e-cigarettes, 76.7% of whom were dual users.3

The prevalence of e-cigarette use is also rising among adults in the US. In a web-based survey,11 3.3% of adults in 2010 and 6.2% in 2011 had ever used an e-cigarette. In addition, awareness of these products among adults increased from 40.9% in 2010 to 57.9% in 2011. Current cigarette smokers had significantly higher levels of ever e-cigarette use than former and never cigarette smokers in both years.

E-cigarettes are marketed as smoking cessation aids5, 12-14 and many adult e-cigarette users cite the desire to stop smoking conventional cigarettes as their reason for using them.8, 15-17 However, the value of e-cigarettes as a cigarette substitute has been questioned because of high levels of dual use with conventional cigarettes.3, 8, 11, 18-21 In addition, two longitudinal population studies of adult smokers contradict claims that e-cigarettes are effective cessation aids: one (in the US, UK, Canada and Australia) found that e-cigarette use is not associated with quitting conventional cigarettes22 and the other (in the US) found significantly less quitting.17 (A randomized clinical trial23 found that e-cigarettes were not superior to nicotine patches for smoking cessation, but both interventions showed low quit rates and there was not a control group of spontaneous quitters.) A cross-sectional US study also24 found that unsuccessful cigarette quitters were significantly more likely to have ever tried e-cigarettes in comparison to individuals who had never tried to quit. Likewise, a cross-sectional study of Korean adolescents3 found that they were using e-cigarettes as smoking cessation aids (OR= 1.58 [95% CI 1.39-1.79] for e-cigarette use among students who had made a quit attempt compared to those who had not) but were less likely to have quit smoking (OR= 0.10 [0.09-0.12]).

To further understand the relationship between e-cigarette use with conventional cigarette use and quitting, this study used data from the 2011 and 2012 National Youth Tobacco Surveys (NYTS) to examine the relationship between e-cigarette use and conventional cigarette smoking and smoking cessation among US adolescents.

METHODS

Data source

The NYTS is a nationally representative cross-sectional sample of students from US middle and high (grades 6-12) schools located in all 50 states and the District of Columbia that was developed to inform national and state tobacco prevention and control programs.25 The 2011 sample included 18,866 students (response rate 88%) from 178 schools (83.2% response rate), and the 2012 sample included 24,658 students (91.7% response rate) from 228 schools (80.3% response rate). The NYTS is an anonymous, self-administered 81-item pencil-and-paper questionnaire that includes indicators of tobacco use (including cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, kreteks, pipes, and emerging tobacco products), tobacco-related beliefs, attitudes about tobacco products, smoking cessation, exposure to secondhand smoke, ability to purchase tobacco products, and exposure to pro- and anti-tobacco influences.26 It uses a three-stage clustered probability sampling design without replacement to select Primary Sampling Units (county, several small counties, portion of large county), schools within each PSU, and students within each school. Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic students are oversampled. Permission to participate is obtained from legal guardians.25

Variables

Conventional cigarette “experimenters” were adolescents who responded “yes” to the question “Have you ever tried cigarette smoking, even one or two puffs?” “Ever smokers” of conventional cigarettes were those who replied “100 or more cigarettes (5 or more packs)” to the question “About how many cigarettes have you smoked in your entire life?” “Current smokers” of conventional cigarettes were those who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes and smoked in the past 30 days.

Intention to quit smoking within the next year in 2011 was measured among current cigarette smokers using the question “I plan to stop smoking cigarettes for good within the next…” Respondents who chose any time within the next year (7 days, 30 days, 6 months, or 1 year) were classified as “intending to quit;” those who responded “I do not plan to stop smoking cigarettes within the next year” were classified as “not intending to quit.” This question was not asked in 2012. We measured quit attempts with the question “During the past 12 months, how many times did you stop smoking for one day or longer because you were trying to quit smoking cigarettes for good?” Those who responded one or more times were considered having made an attempt; those who responded “I did not try to quit during the past 12 months” were considered not having made a quit attempt.

Thirty-day, 6-month and 1-year abstinence from conventional cigarettes was based on responses to the question “When was the last time you smoked a cigarette, even one or two puffs?” “Not in the past 30 days but in the past 6 months” was coded as 30-day abstinence, “not in the past 6 months but in the past year” as 6-month abstinence, and “1 to 4 year ago” or “5 or more years ago” as 1-year abstinence.

“Ever e-cigarette users” were adolescents who responded “Electronic Cigarettes or E-cigarettes, such as Ruyan or NJOY” to the question “Which of the following tobacco products have you ever tried, even just one time?” “Current e-cigarette users” were those who responded e-cigarettes to the question “During the past 30 days, which of the following tobacco products did you use on at least one day?”

Covariates included race, gender, and age (in years, continuous)Race and ethnicity were coded based on answers to the question, “Are you Hispanic or Latino?” and “What race or races do you consider yourself to be?” (White, Black, Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander). Responses were collapsed into non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and other to obtain at least 20 ever e-cigarette users in each category.

Analysis

The 92.0% of respondents (17,353/18,866) in 2011 and 91.4% (22,529/24,658) of respondents in 2012 with complete data on conventional cigarette use, e-cigarette use, and covariates were included in this analysis using SAS-callable SUDAAN (SAS version 9.3, SUDAAN version 11.0.0), which accounted for the stratified clustered sampling design of the NYTS, and STATA 12.1, which was used to pool the data from both years. Sampling weights were used in all analyses to adjust for nonresponse, the probability of selection, and to match the sample's sociodemographic characteristics with those of US middle and high school students in 2011.25-26

PROC CROSSTAB was used for chi-square analyses of categorical demographic variables by e-cigarette use. PROC DESCRIPT and PROC REGRESS (generalized linear model) provided means and p-values for bivariate analyses of continuous and ordinal variables. All descriptive statistics and odds ratios were adjusted for stratification variables and weights. PROC RLOGIST was used to obtain odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from multivariable logistic regression models of e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking, intention to quit, quit attempts, and abstinence from cigarettes, adjusting for demographic covariates. Because the NYTS study designs in 2011 and 2012 were essentially identical, we pooled adjusted odds ratios for e-cigarette use in 2011 and 2012 (Table 2) using a fixed effects meta-analysis with STATA metan. As expected, there was no evidence of heterogeneity between the two years (median p-values for heterogeneity = .303, .341; range .088 to .984).

Table 2.

Pooled analysis of ever e-cigarette usea and currentb e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking for 2011 and 2012 surveysc

| Cigarette smoking status | Abstinence from cigarettes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Ever Smoking (≥100 cigs) | Current Smoking (≥100 cigs, ≥1 cig past 30 days) | 30-day abstinenced,e | 6-month abstinencec,g | 1-year abstinencec,h |

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Cigarette experimenters (≥1 puff of a cigarette, n=10,850) | |||||

| Ever e-cig usea | 6.31 (5.39-7.39) | 5.96 (5.67-6.27) | 0.24 (0.21-0.28) | 0.24 (0.21-0.28) | 0.25 (0.21-0.30) |

| Current e-cig useb | 7.42 (5.63-9.79) | 7.88 (6.01-10.32) | 0.11 (0.08-0.15) | 0.11 (0.08-0.15) | 0.12 (0.07-0.18) |

| Ever cigarette smokers (≥100 cigs, n=1,832) | |||||

| Ever e-cig usea | - | - | 0.61 (0.42-0.89) | 0.53 (0.33-0.83) | 0.32 (0.18-0.56) |

| Current e-cig useb | - | - | 0.35 (0.18-0.69) | 0.30 (0.13-0.68) | 0.34 (0.13-0.87) |

RESULTS

In 2011, 3.1% of the study sample had ever tried e-cigarettes (1.7% dual ever use, 1.5% only e-cigs), and 1.1% were current e-cigarette users (0.5% dual use, 0.6% only e-cigs). In 2012, 6.5% of the sample had tried e-cigarettes (2.6% dual use, 4.1% e-cigarettes only) and 2.0% were current e-cigarette users (1.0% dual use, 1.0% only e-cigs). Ever and current e-cigarette use varied significantly by sociodemographic characteristics (Table 1). Ever e-cigarette users were significantly more likely to be male (p<.01), white (p<.01), and older (p<.01). Ever conventional cigarette smokers (≥100 cigarettes in lifetime) were significantly more likely than never smokers to have tried e-cigarettes (p<.01) and be current e-cigarette users (p<.01). Compared to nonsmokers (never and former smokers), current cigarette smokers were significantly more likely to have used e-cigarettes (p<.01) and to be current e-cigarette users (p<.01). Among ever e-cigarette users, in 2011, 45.4% had never been established smokers of conventional cigarettes, and, among current e-cigarette users, 49.7% were current smokers of conventional cigarettes. In 2012, 61.2% of ever e-cigarette users had never been established smokers and 49.8% of current e-cigarette users were current cigarette smokers.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents in the 2011 and 2012 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) by evera and currentb use of e-cigarettes in 2011 (n=17,353) and 2012 (n=22,529)c

| 2011 | 2012 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette use | Alld % (n) | Ever usea,e % (n) | Current useb,e % (n) | Alld % (n) | Ever usea,e % (n) | Current useb,e % (n) |

| All | 3.1% (511) | 1.1% (174) | 6.5% (1450) | 2.0% (462) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 50.6% (8544) | 3.9% (296)** | 1.6% (114)** | 50.1% (11093) | 7.7% (863)** | 2.7% (305)** |

| Female | 49.4% (8809) | 2.4% (215) | 0.6% (60) | 49.9% (11436) | 5.3% (587) | 1.4% (157) |

| Race | ||||||

| NH White | 56.6% (6731) | 3.8% (274)** | 1.2% (81)* | 54.7% (11311) | 7.8% (878)** | 2.2% (257)** |

| NH Black | 13.9% (3102) | 1.2% (28) | 0.6% (12) | 13.5% (2886) | 2.8% (79) | 1.1% (28) |

| Other | 29.5% (7520) | 2.8% (209) | 1.0% (80) | 31.8 (8332) | 5.7% (493) | 2.1% (177) |

| Ever cig. smokingf | ||||||

| Ever smokers | 5.6% (860) | 30.8% (234)** | 10.3% (80)** | 4.5% (972) | 57.1% (562)** | 23.5% (237)** |

| Never smokers | 94.4% (16493) | 1.5% (277) | 0.5% (94) | 95.5% (21557) | 4.1% (888) | 1.0% (225) |

| Dual ever useg | 1.7% (232) | 2.6% (562) | ||||

| Current cig. smokingh | ||||||

| Smoker | 5.0% (778) | 31.9% (219)** | 10.6% (76)** | 4.0% (869) | 57.2% (505)** | 25.7% (230)** |

| Nonsmoker | 95.0% (16575) | 1.6% (292) | 0.6% (98) | 96.0% (21660) | 4.4% (945) | 1.1% (232) |

| Dual current usei | 0.5% (75) | 1.0% (230) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 14.7 (0.1) | 15.8 (0.1)** | 15.3 (0.2)** | 14.6 (0.1) | 15.9 (0.1)** | 15.7 (0.1)** |

Reflecting high levels of dual use, ever and current e-cigarette use was associated with very high odds of experimentation with cigarettes, ever cigarette smoking, and current cigarette smoking (eTable 1, e-Table 2).

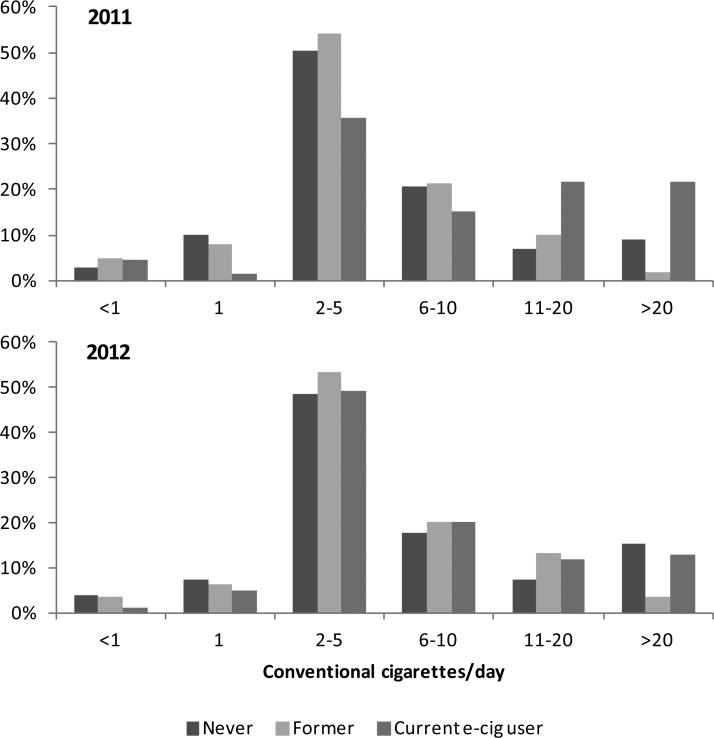

Among current smokers current e-cigarette use was associated with higher levels of cigarette consumption (p≤.003 for both years; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Current e-cigarette use was associated (p<.003 in both years) with heavier smoking among conventional smokers (≥100 cigarettes lifetime, smoked in past 30 days). Participants were a representative sample of U.S. middle and high school students in the National Youth Tobacco Survey. Current e-cigarette users had used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days. Former e-cigarette users had tried e-cigarettes but had not used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days. Never e-cigarette users had never tried an e-cigarette. Conventional cigarettes per day is the number of cigarettes smoked per day on the days smoked during the past 30 days.

In pooled analyses, among experimenters (ever smoked a puff), ever e-cigarette use was positively associated with odds of being an established smoker (≥100 cigarettes; OR=6.31 [5.39-7.39]) and current cigarette smoking (≥100 cigarettes and smoked in past 30 days; 5.96 [5.67-6.27]). Current e-cigarette use was also associated with ever cigarette smoking (7.42 [5.63-9.79]) and current cigarette smoking (7.88 [6.01-10.32] (Table 2). See Table 3 for separate analyses by year.

Table 3.

Association of e-cigarettes use with evera and currentb smoking among adolescents reporting experimentationc with cigarettes in the 2011 National Youth Tobacco Survey (2011: n=5,169, 2012: 5,681)d

| 2011 | 2012 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Ever smokinga OR (95%CI) | Current smokingb OR (95%CI) | Ever smokinga OR (95%CI) | Current smokingb OR (95%CI) |

| Ever e-cig use e | 7.66 (5.44-10.79) | 7.43 (5.39-10.22) | 5.99 (5.02-7.16) | 5.61 (4.66-6.76) |

| Age (years) | 1.33 (1.23-1.44) | 1.30 (1.20-1.41) | 1.24 (1.17-1.33) | 1.25 (1.16-1.35) |

| NH White | REF | REF | ||

| NH Black | 0.37 (0.23-0.57) | 0.43 (0.28-0.67) | 0.44 (0.29-0.69) | 0.47 (0.31-0.72) |

| NH Other | 0.72 (0.54-0.97) | 0.76 (0.57-1.01) | 0.73 (0.58-0.92) | 0.77 (0.60-0.99) |

| Male | 1.39 (1.13-1.70) | 1.44 (1.16-1.78) | 1.53 (1.26-1.86) | 1.44 (1.18-1.74) |

| Ever e-cig use (unadjusted) | 8.52 (6.06-11.98) | 8.31 (6.02-11.46) | 6.97 (5.76-8.44) | 6.52 (5.37-7.93) |

| Current e-cig use f | 7.46 (4.12-13.49) | 6.84 (3.95-11.84) | 7.41 (5.41-10.14) | 8.24 (6.04-11.23) |

| Age (years) | 1.35 (1.25-1.46) | 1.32 (1.23-1.43) | 1.29 (1.22-1.37) | 1.30 (1.22-1.39) |

| NH White | REF | REF | ||

| NH Black | 0.31 (0.20-0.47) | 0.36 (0.24-0.55) | 0.32 (0.21-0.50) | 0.35 (0.23-0.53) |

| NH Other | 0.67 (0.50-0.89) | 0.69 (0.52-0.92) | 0.61 (0.48-0.77) | 0.64 (0.49-0.84) |

| Male | 1.38 (1.13-1.70) | 1.44 (1.16-1.77) | 1.55 (1.27-1.90) | 1.45 (1.19-1.77) |

| Current e-cig use (unadjusted) | 6.84 (4.01-11.67) | 6.49 (3.92-10.76) | 7.52 (5.69-9.93) | 8.31 (6.28-11.00) |

E-cigarette use was also associated with lower odds of abstinence. Among experimenters, ever e-cigarette use associated with lower odds of 30-day (OR=0.24 [0.21-0.28]), 6-month (0.24 [0.21-0.28]), and 1-year abstinence (0.25 [0.21-0.30]) from conventional cigarettes. Current e-cigarette use was also associated with lower odds of 30-day (0.11 [0.08-0.15]), 6-month (0.11 [0.08-0.15]), and 1-year abstinence from conventional cigarettes (0.12 [0.07-0.18]). See Table 4 for analyses by year.

Table 4.

Ever e-cigarette usea and currentb e-cigarette use and abstinence from smokingc among experimentersd with conventional cigarettes in the 2011 National Youth Tobacco Survey (2011: n=5,169; 2012: 5,681)e

| 2011 | 2012 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | 30-day abstinencec,f OR (95%CI) | 6-month abstinencec,g OR (95%CI) | 1-year abstinencec,h OR (95%CI) | 30-day abstinencec,f OR (95%CI) | 6-month abstinencec,g OR (95%CI) | 1-year abstinencec,h OR (95%CI) |

| Ever e-cig usea | 0.22 (0.16-0.29) | 0.21 (0.16-0.28) | 0.21 (0.15-0.31) | 0.25 (0.21-0.29) | 0.25 (0.21-0.30) | 0.27 (0.22-0.33) |

| Age (years) | 0.91 (0.86-0.95) | 0.94 (0.90-0.98) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | 0.91 (0.87-0.96) | 0.94 (0.89-0.99) | 0.95 (0.91-1.00) |

| NH White | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| NH Black | 1.43 (1.04-1.96) | 1.91 (1.51-2.41) | 2.18 (1.72-2.75) | 1.33 (1.06-1.68) | 1.98 (1.54-2.54) | 2.07 (1.65-2.60) |

| NH Other | 1.20 (0.99-1.46) | 1.40 (1.21-1.61) | 1.53 (1.33-1.77) | 1.09 (0.94-1.26) | 1.25 (1.06-1.48) | 1.36 (1.13-1.65) |

| Male | 0.91 (0.78-1.07) | 0.90 (0.76-1.06) | 0.82 (0.67-1.00) | 0.83 (0.73-0.93) | 0.87 (0.76-1.00) | 0.90 (0.77-1.05) |

| Ever e-cig use (unadjusted) | 0.20 (0.15-0.27) | 0.19 (0.15-0.25) | 0.19 (0.13-0.28) | 0.23 (0.20-0.26) | 0.22 (0.19-0.27) | 0.24 (0.19-0.29) |

| Current e-cig useb | 0.15 (0.08-0.27) | 0.15 (0.07-0.32) | 0.17 (0.07-0.38) | 0.10 (0.07-0.14) | 0.10 (0.06-0.16) | 0.10 (0.06-0.17) |

| Age (years) | 0.89 (0.85-0.93) | 0.93 (0.89-0.97) | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | 0.88 (0.84-0.93) | 0.92 (0.87-0.96) | 0.93 (0.89-0.98) |

| NH White | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| NH Black | 1.57 (1.16-2.12) | 2.05 (1.63-2.57) | 2.32 (1.84-2.92) | 1.62 (1.27-2.06) | 2.33 (1.79-3.03) | 2.39 (1.88-3.03) |

| NH Other | 1.26 (1.04-1.51) | 1.45 (1.27-1.66) | 1.58 (1.38-1.82) | 1.23 (1.05-1.44) | 1.38 (1.17-1.64) | 1.49 (1.22-1.81) |

| Male | 0.91 (0.78-1.06) | 0.89 (0.76-1.06) | 0.81 (0.67-0.99) | 0.83 (0.74-0.93) | 0.87 (0.76-0.99) | 0.90 (0.78-1.03) |

| Current e-cig use (unadjusted) | 0.15 (0.08-0.27) | 0.14 (0.06-0.32) | 0.15 (0.07-0.35) | 0.09 (0.06-0.14) | 0.09 (0.06-0.15) | 0.10 (0.06-0.16) |

Among ever cigarette smokers (≥100 cigarettes), ever e-cigarette was negatively associated with 30-day (OR=0.61 [0.42-0.89] 6-month (OR=0.53, [0.33-0.83]), and one-year (OR=0.32 [0.18-0.56) abstinence from conventional cigarettes. Current e-cigarette use was also negatively associated with 30-day (OR=0.35, [0.18-0.69]), 6-month (OR=0.30, [0.13-0.68]), and 1-year (OR=0.34, [0.13- 0.87]) abstinence from conventional cigarettes See Table 5 for analyses by year.

Table 5.

Ever e-cigarette usea and currentb e-cigarette use and abstinencec from smoking conventional cigarettes among ever smokersd in the 2011 National Youth Tobacco Survey (2011: n=860, 2012: n=972)e

| 2011 | 2012 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | 30-day abstinencec,f OR (95%CI) | 6-month abstinencec,g OR (95%CI) | 1-year abstinencec,h OR (95%CI) | 30-day abstinencec,f OR (95%CI) | 6-month abstinencec,g OR (95%CI) | 1-year abstinencec,h OR (95%CI) |

| Ever e-cig usea | 0.57 (0.31-1.04) | 0.48 (0.18-1.23) | 0.40 (0.10-1.53) | 0.64 (0.40-1.03) | 0.54 (0.32-0.90) | 0.30 (0.16-0.56) |

| Age (years) | 1.09 (0.98-1.22) | 1.08 (0.93-1.26) | 0.99 (0.85-1.15) | 0.94 (0.80-1.10) | 0.94 (0.80-1.10) | 0.93 (0.77-1.12) |

| NH White | REF | REF | REF | |||

| NH Black | 0.81 (0.22-3.01) | 1.65 (0.38-7.07) | 2.55 (0.44-14.80) | 0.40 (0.16-0.99) | 0.52 (0.14-1.87) | 0.48 (0.10-2.23) |

| NH Other | 1.12 (0.72-1.74) | 1.30 (0.66-2.55) | 1.59 (0.60-4.19) | 1.08 (0.65-1.79) | 1.23 (0.62-2.45) | 1.22 (0.61-2.41) |

| Male | 0.87 (0.53-1.42) | 1.49 (0.67-3.34) | 1.97 (0.72-5.40) | 1.53 (0.98-2.38) | 1.55 (0.85-2.80) | 1.74 (0.82-3.69) |

| Ever e-cig use (unadjusted) | 0.56 (0.31-1.02) | 0.47 (0.19-1.18) | 0.38 (0.10-1.48) | 0.69 (0.44-1.09) | 0.57 (0.35-0.92) | 0.31 (0.17-0.58) |

| Current e-cig useb | 0.61 (0.23-1.64) | 0.73 (0.20-2.71) | 0.79 (0.14-4.42) | 0.22 (0.09-0.56) | 0.17 (0.06-0.49) | 0.24 (0.08-0.75) |

| Age (years) | 1.08 (0.97-1.21) | 1.07 (0.92-1.25) | 0.99 (0.85-1.15) | 0.92 (0.78-1.07) | 0.91 (0.78-1.08) | 0.90 (0.74-1.09) |

| NH White | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| NH Black | 0.91 (0.25-3.38) | 1.89 (0.46-7.84) | 2.96 (0.52-16.73) | 0.40 (0.17-0.94) | 0.56 (0.17-1.81) | 0.65 (0.16-2.58) |

| NH Other | 1.19 (0.77-1.85) | 1.40 (0.72-2.73) | 1.74 (0.65-4.65) | 1.16 (0.69-1.98) | 1.35 (0.67-2.73) | 1.38 (0.68-2.78) |

| Male | 0.85 (0.52-1.39) | 1.44 (0.65-3.15) | 1.86 (0.68-5.09) | 1.61 (1.04-2.49) | 1.60 (0.90-2.84) | 1.71 (0.82-3.57) |

| Current e-cig use (unadjusted) | 0.56 (0.22-1.47) | 0.75 (0.20-2.83) | 0.89 (0.16-4.95) | 0.25 (0.10-0.61) | 0.20 (0.07-0.53) | 0.27 (0.09-0.81) |

In adjusted analyses for 2011, among current smokers, ever e-cigarette use was associated with planning to stop smoking within the next year (OR=1.53, [1.03-2.28]), but current e-cigarette use was not (OR=1.34, [0.62-2.90]). In contrast, in pooled analyses, neither ever e-cigarette use (OR=1.01, [0.77-1.34]) nor current e-cigarette use (OR=0.89, [0.61-1.30]) was significantly associated with having made a quit attempt in the past 12 months after adjusting for covariates.

We also ran all analyses unadjusted by demographic variables, with little impact on the effects of e-cigarette use, indicating that the results were not due to confounding by demographic variables (Tables 3-5).

COMMENT

As with adults,8-10 dual use of e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes is high among adolescents and increasingly rapidly. Adolescents who had ever experimented with cigarettes (smoked at least a puff) and used e-cigarettes were more likely to report having smoked at least 100 cigarettes and to be current smokers than adolescents who never used e-cigarettes. Thus, in combination with the observations that e-cigarette users are heavier smokers and less likely to have stopped smoking cigarettes, these results suggest that e-cigarette use is aggravating rather than ameliorating the tobacco epidemic among youth. These results call into question claims15, 27-28 that e-cigarettes are effective as smoking cessation aids.

Our US results are consistent with those for Korean youth,3 with high levels of dual use in both populations. Current e-cigarette users (past 30 days) were much less likely to have abstained from smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days in both populations (≥1 puff but not in past 30 days, OR=0.10 [0.09-0.12] in Korean youth vs. OR=0.15 [0.08-0.28] for experimenters with cigarettes in US youth). Among current cigarette–smoking youth in Korea there was a significant association between current e-cigarette use and attempting to quit smoking in the past 12 months (OR=1.67, [1.48- 1.90]), but there was not a significant association for US youth (OR=1.20, [0.65-2.23]). This difference may reflect behavioral differences between the two countries, but may also reflect the lower power in our study. The Korean sample was much larger than ours (75,643 versus 17,320) with higher prevalence of current (12.1% versus 5.0%) and ever cigarette smoking (26.3% versus 5.6%) and current (4.7% versus 1.1%) and ever e-cigarette use (9.4% versus 3.1%).

Although e-cigarettes deliver many fewer toxins and at much lower levels than conventional cigarettes,29-31 they contain nicotine, a highly addictive substance,32 in doses designed to mimic cigarettes. Animal models suggest that, through its impact on cholinergic pathways, nicotine may have permanent effects on the brain and behavior,33-34 such as dysregulation of the limbic system, which can lead to long-term difficulties with behavioral regulation, attention, memory and motivation, among other functions. 34-35 The adolescent human brain may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of nicotine because it is still developing. 36-38

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional study, which only allows us to identify associations, not causal relationships. Our results are also limited by the lack of information about motivation for using e-cigarettes (e.g., popularity, trendy, smoking cessation) and the fact that they only apply to middle and high school students, not all US youth.

In comparison to the 8.0% and 8.6% of respondents who had missing data in 2011 and 2012, respectively, and were dropped, our analytical sample was slightly more female (2011: 49.4% versus 42.9%, p=.0074, 2012: 49.9% versus 38.3%, p<.0001) and less white (2011: 56.6% versus 39.5%, p=<.0001, 2012: 54.7% versus 39.8%, p<.0001); eTable 2). In 2012 only, our sample also had a lower prevalence of e-cigarette user (6.5% versus 10.2%, p=.0019) and was slightly younger (age 14.6 versus 14.2, p<.0001) than the students with missing data. There were no significant differences by any of the other demographic or e-cigarette or cigarette smoking variables.

Conclusion

While the cross-sectional nature of our study does not allow us to identify whether most youth are initiating smoking with conventional cigarettes and then moving on to (usually dual use of) e-cigarettes or vice versa, our results suggest that e-cigarettes are not discouraging use of conventional cigarettes. Among experimenters with conventional cigarettes, e-cigarette use is associated with established cigarette smoking and lower rates of abstinence from conventional cigarettes. The debate over e-cigarettes 2, 29, 32, 39-41 has centered on whether e-cigarettes could be useful as a harm reduction strategy in established adult cigarette smokers. The results in this paper, together with those from Korea,3 suggest that e-cigarettes may contribute to nicotine addiction and are unlikely to discourage conventional cigarette smoking among youth.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental tables

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This manuscript was funded by National Cancer Institute grants CA-113710 and CA-060121. The funding agencies played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. Both authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation: Report on the Scientific Basis of Tobacco Product Regulation: Third Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobb N, Byron M, Abrams D, Shields P. Novel Nicotine Delivery Systems and Public Health: The Rise of The “E-Cigarette”. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:2340. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.199281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee S, Grana R, Glantz S. Electronic-cigarette use among Korean adolescents: A cross-sectional study of market penetration, dual use, and relationship to quit attempts and former smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.003. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobb N, Abrams D. E-Cigarette or Drug-Delivery Device? Regulating Novel Nicotine Products. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:193–195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1105249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grana R, Ling P. Smoking Revolution? A content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.010. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corey C, Wang B, Johnson SE, et al. Electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students- United States, 2011-2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(35):729–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson JL, Richardson A, Niaura RS, Vallone DM, Abrams DB. e-Cigarette Awareness, Use, and Harm Perceptions in US Adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(9):1758–1766. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300526. 2012/09/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regan A, Promoff G, Dube S, Arrazola R. Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems: Adult Use and Awareness of the ‘E-Cigarette’ in the USA. Tobacco Control. 2011;22:19–23. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rath J, Villanti A, Abrams D, Vallone DM. Patterns of Tobacco Use and Dual Use in US Young Adults: The Missing Link between Youth Prevention and Adult Cessation. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2012/679134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King BA, Alam S, Promoff G, Arrazola R, Dube SR. Awareness and Ever Use of Electronic Cigarettes Among U.S. Adults, 2010–2011. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013 Feb 28; doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt013. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S, Kimm H, Yun JE, Jee SH. Public Health Challenges of Electronic Cigarettes in South Korea. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 2011;44:235–241. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2011.44.6.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Andrade M, Hastings G. The Marketing of E-Cigarettes: A UK Snapshot. BMJ Group Blogs. 2013 Apr 6; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamin C, Bitton A, Bates D. E-Cigarettes: A Rapidly Growing Internet Phenomenon. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;153:607–609. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-9-201011020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etter JF. Electronic cigarettes: a survey of users. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Little M, Kawamoto C, Herzog TA. Smokers who try e-cigarettes to quit smoking: Findings from a multiethnic study in Hawaii. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(9):e57–e62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vickerman KA, Carpenter KM, Altman T, Nash CM, Zbikowski SM. Use of electronic cigarettes among state tobacco cessation quitline callers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013 Oct;15(10):1787–1791. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMillen R, Maduka J. Use of emerging tobacco products in the United States. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2012;2012:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2012/989474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutfin EL, McCoy TP, Morrell HE, Hoeppner BB, Wolfson M. Electronic cigarette use by college students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013 Aug 1;131(3):214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regan A, Promoff G, Dube S, Arrazola R. Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems: Adult Use and Awareness of the ‘E-Cigarette’ in the USA. Tobacco Control. 2013;22:19–23. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dockrell M, Morison R, Bauld L, McNeill A. E-Cigarettes: Prevalence and Attitudes in Great Britain. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013 May 23; doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt057. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adkison SE, O'Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: International tobacco control four-country survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(3):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013 Sep 9; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61842-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popova L, Ling P. Alternative tobacco product use and smoking cessation: A national study. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):923–930. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control National Youth Tobacco Survey: Methodology Report. 2011.

- 26.National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) [9/15/2013];Smoking & Tobacco Use 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/. 2013.

- 27.Chan A. Electronic cigarettes help you quit smoking as well as nicotine patches: Study. The Huffington Post. 2013 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/p/huffington-post.html.

- 28.Durning MV. Electronic cigarettes may help you quit smoking, new study shows. 2013 Forbes.com.

- 29.Cahn Z, Siegel M. Electronic cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy for tobacco control: A step forward or a repeat of past mistakes? Journal of Public Health Policy. 2011;32:16–31. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laugesen M. Safety Report on the Ruyan e-Cigarette Cartridge and Inhaled Aerosol. [10/4/2013];Health New Zealand. 2008 http://www.healthnz.co.nz/DublinEcigBenchtopHandout.pdf.

- 31.Goniewicz ML, Knysak J, Gawron M, et al. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tobacco Control. 2013;0:1–7. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benowitz N, Goniewicz ML. The regulatory challenge of electronic cigarettes. JAMA. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.109501. Published online 7/15/2013: http://jama.jamanetwork.com. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Liao C-Y, Chen Y-J, Lee J-F, Lu C-L, Chen C-H. Cigarettes and the developing brain: Picturing nicotine as a neuroteratogen using clinical and preclinical studies. Tzu Chi Medical Journal. 2012;24(4):157–161. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dwyer JB, Broide RS, Leslie FM. Nicotine and brain development. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2008 Mar;84(1):30–44. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dwyer JB, McQuown SC, Leslie FM. The dynamic effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2009;122(2):125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slotkin TA. Cholinergic systems in brain development and disruption by neurotoxicants: nicotine, environmental tobacco smoke, organophosphates. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2004;198(2):132–151. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goriounova NA, Mansvelder HD. Short- and long-term consequences of nicotine exposure during adolescence for prefrontal cortex neuronal network function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Dec;2(12):a012120. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, et al. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004 May 25;101(21):8174–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101. 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Lancet Oncology Time for e-cigarette regulation. The Lancet Oncology. 2013;14(11):1027. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70468-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henningfield JE, Zaatari GS. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: emerging science foundation for policy. Tobacco Control. 2010 Apr 1;19(2):89–90. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.035279. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flouris AD, Oikonomou DN. Electronic cigarettes: miracle or menace? BMJ. 2010:340. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c311. 2010-01-20 00:06:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental tables