Internet and Telephone Treatment for Smoking Cessation: Mediators and Moderators of Short-Term Abstinence (original) (raw)

Abstract

Introduction:

This study examined mediators and moderators of short-term treatment effectiveness from the iQUITT Study (Quit Using Internet and Telephone Treatment), a 3-arm randomized trial that compared an interactive smoking cessation Web site with an online social network (enhanced Internet) alone and in conjunction with proactive telephone counseling (enhanced Internet plus phone) to a static Internet comparison condition (basic Internet).

Methods:

The analytic sample was N = 1,236 participants with complete 3-month data on all mediating variables. The primary outcome was 30-day point prevalence abstinence (ppa) at 3 months. Recognizing the importance of temporal precedence in mediation analyses, we also present findings for 6-month outcomes. Purported mediators were treatment utilization and changes in psychosocial constructs. Proposed moderators included baseline demographic, smoking, and psychosocial variables. Mediation analyses examined the extent to which between-arm differences in 30-day ppa could be attributed to differential Web site utilization, telephone counseling, and associated changes in smoking self-efficacy and social support for quitting. Effect modification analyses fitted interactions between treatment and prespecified moderators on abstinence.

Results:

Significant mediators of 30-day ppa were changes in smoking temptations, quitting confidence, and positive and negative partner support, which were strongly associated with increased Web site utilization. The addition of telephone counseling to an enhanced Web site further improved abstinence rates, partly via an association with increased quitting confidence. Baseline smoking rate was the only significant moderator.

Conclusions:

Increased treatment utilization and associated changes in several psychosocial measures yielded higher abstinence rates. Findings validate the importance of treatment utilization, smoking self-efficacy, and social support to promote abstinence.

Introduction

Identifying mediators and moderators of intervention effectiveness in randomized trials can help determine leverage points for improving effectiveness.1 Mediator analyses identify possible mechanisms or causal links through which an intervention achieved its effect. Measurement of mediators is critical for the systematic progression of intervention research because it allows researchers to determine which components of an intervention contribute to behavior change.2 Moderator analyses specify for whom or under what conditions an intervention is effective.

Internet interventions have the potential for large public health impact given their broad reach.3 Over the past 10 years, more than two dozen randomized or quasirandomized trials of Internet smoking cessation interventions have been conducted.4 However, there have been few investigations into the mediators and moderators of web-based interventions. Strecher and colleagues5 found that perceived program relevance at 6 weeks mediated cessation outcomes at 12 weeks. Increases in self-efficacy have been noted as a mediator in several web-based intervention trials,6–8 and one smokeless tobacco trial noted the important role of partner support in promoting abstinence.9 Few studies have explicitly examined socio-demographic moderators of treatment effectiveness.10 Smoking variables that have emerged as moderators in web-based studies include baseline smoking rate,11 the presence of a tobacco-related illness,5 nonsmoking children in the household,5 and intention to stop smoking.10 Psychosocial moderators that have emerged in other studies include depressive symptoms,12 a history of major depressive episodes,13 and frequent alcohol consumption.5

We sought to build on the limited evidence in this area by examining theory-driven mediators and moderators of treatment effectiveness in The iQUITT Study (Quit Using Internet and Telephone Treatment), a randomized controlled trial of Internet and telephone treatment for smoking cessation.14 The trial compared an interactive smoking cessation Web site with an online social network (enhanced Internet [EI]) alone and in conjunction with proactive telephone counseling (enhanced Internet plus phone [EI + P]) to a static Internet comparison condition (basic Internet [BI]). Previously reported trial outcomes15 showed an early advantage for EI + P: among participants reached at 3, 6, and 12 months, EI + P yielded higher 30-day point prevalence abstinence (ppa) rates than both EI and BI. There were no differences between study arms at 18 months, with BI and EI reaching the same level of abstinence that EI + P had maintained since early in the study (25%–29%). No differences between BI and EI were observed at any timepoint. Intent-to-treat analyses that coded nonresponders as smokers produced a similar pattern of between-group differences, albeit at lower abstinence rates.

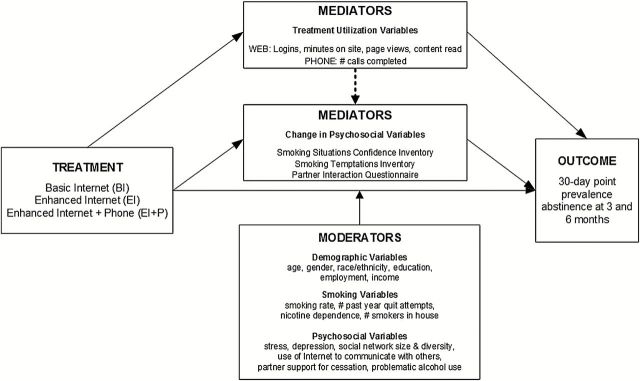

We aimed to address two primary questions from the parent trial: (a) Was the early advantage of EI + P explained by differential treatment utilization and associated changes in psychosocial constructs (mediator analyses)? and (b) Were there subgroups for whom direct intervention effects on abstinence rates were more or less effective (moderator analyses)? These analyses focus on 3-month outcomes because this was when the strongest intervention effects were observed.15 Recognizing the importance of temporal precedence in mediation analyses, we also present findings for 6-month outcomes. Analyses were guided by our theoretical model (Figure 1), derived primarily from Social Cognitive Theory,16 models of social support and social networks in cessation,17 and prior empirical findings.18,19

Figure 1.

Research model.

A priori mediator hypotheses were that Web site utilization would be higher in EI and EI + P compared with BI, and that Web site utilization would mediate the links between treatment and outcome. Similarly, we hypothesized that increases in smoking self-efficacy and positive support for quitting (i.e., encouraging, congratulating) and decreases in negative support for quitting (i.e., nagging, criticizing) would be greater in EI and EI + P compared with BI given the availability of more extensive information and support through the online social network and telephone counselors, and would reach their highest levels in EI + P given the combined intervention approach. We also hypothesized that these increases would, in turn, lead to even higher abstinence rates in EI + P than EI. A priori moderator hypotheses were that interventions would be effective across demographic subgroups, but that greater levels of addiction (e.g., smoking rate, nicotine dependence) or the presence of comorbid conditions (e.g., stress, depression, alcohol use) would moderate treatment effectiveness.

Methods

Recruitment and Eligibility Criteria

Study methods have been described elsewhere.15 Briefly, participants were adult current smokers in the United States who used the terms quit(ting) smoking, stop(ping) smoking, or smoking in a major Internet search engine, and who clicked on a link to the cessation Web site being evaluated (www.QuitNet.com).14 Eligibility screening and informed consent were conducted online, followed by the baseline telephone assessment. Randomization was stratified by gender and motivation to quit. Participants were e-mailed a link to their assigned Internet intervention and instructions about telephone counseling.

Interventions

Participants randomized to EI had 6-month free access to the premium service of QuitNet.18 QuitNet incorporates evidence-based elements of tobacco dependence treatment20 including practical counseling for cessation, pharmacotherapy information, and intratreatment social support through a large online social network.21 Participants randomized to EI + P also had 6-month free access to QuitNet plus five proactive telephone counseling calls provided by National Jewish Health. Participants randomized to BI had 6-month free access to an information-only comparison condition comprised of the major content on QuitNet: information about cessation (“Quitting Guide”) and pharmacotherapy (“Medication Guide”), a directory of national cessation programs, and a 10-year database of Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs).

Assessment Procedures

The baseline telephone assessment was administered following online eligibility screening and informed consent. Follow-up assessments were conducted by phone ($25 incentive) or online for telephone nonresponders ($15 incentive). The follow-up rate at 3 months was 76.4% (BI = 79.1%; EI = 76.7%; EI + P = 73.5%) and at 6 months was 74.7% (BI = 77.3%; EI = 74.0%; EI + P = 72.6%).

Measures

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was 30-day self-reported ppa, measured at both 3 and 6 months. Self-reported smoking status is a commonly accepted outcome measure in Internet cessation trials,12,22–27 where biochemical verification of abstinence is not feasible and misreporting of abstinence is expected to be minimal given low demand characteristics.28

Potential Treatment Mediators

We examined two categories of mediators: (a) 3-month treatment utilization metrics and (b) baseline to 3-month changes in psychosocial constructs. Web site utilization metrics common to all three arms included the number of logins, total number of minutes spent on the Web site, number of page views, and use of the major content elements (i.e., Quitting Guide, Medication Guide, National Directory of Cessation Programs, FAQs). Telephone counseling was only provided in EI + P and was measured by number of telephone contacts. Psychosocial measures administered at baseline and 3-month follow-up included the short-forms of the Smoking Situations Confidence Inventory and the Smoking Temptations Inventory29—both measures of self-efficacy—and a modified version of the Partner Interaction Questionnaire (PIQ)30,31 that assessed positive and negative behaviors from a friend or family member related to quitting.

Candidate Treatment Moderators

Demographic, smoking, and select psychosocial variables from the baseline assessment were examined as potential moderators. Age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment, and household income were assessed.32 Smoking variables included daily smoking rate, number of past year quit attempts, the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence,33 and number of household smokers. Psychosocial measures included the Perceived Stress Scale,34 the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale,35 social network size and diversity measured by the Social Network Index,36 use of the Internet to communicate with others (not including e-mail), baseline levels of the PIQ, and problematic alcohol use.37

Statistical Analyses

Sample Characteristics and Treatment Utilization

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize additional study characteristics not reported in the main outcome analysis, as well as 3-month treatment utilization metrics. Frequency tables summarize categorical data, and parametric and nonparametric tests were employed to determine statistical significance.

Mediation Analyses

Mediation analyses examined the extent to which between-arm differences in 30-day ppa rates could be attributed to between-arm differences in 3-month treatment utilization metrics, as well as to differential increases from baseline in self-efficacy and social support for quitting smoking.

In mediation analysis, it is important to distinguish Action Theory tests (intervention effects on putative mediators) from Conceptual Theory tests (effects of putative mediators on outcome) because results have differing implications.38Action Theory tests for treatment utilization metrics were based on Poisson regression models for counts and employed a logarithmic link for Web site logins. Action Theory tests for psychosocial mediators were based on normal linear regression models that evaluated between-arm differences in mediator change scores adjusted for baseline values. Two models were fit for each psychosocial mediator: one that controlled for treatment utilization and one that did not. They are distinguished in Figure 1 by whether the broken arrow connecting utilization metrics to psychosocial mediators is active or not.

Conceptual Theory tests evaluated whether observed changes in a proposed mediator were associated with statistically significant changes in the outcome, controlling for any intervention effects.39 Because mediator/outcome correlations at baseline can confound the mediator/outcome relationship at follow-up, Conceptual Theory tests were adjusted for baseline values of all putative mediators and outcome.40 In this case, outcome (i.e., smoking status) showed no variability at baseline and was omitted. Conceptual Theory tests were based upon three nested normal linear regression models, all of which controlled for direct intervention effects on 30-day ppa rates: Model A controlled for treatment utilization across study arms; Model B added baseline values and 3-month change in putative psychosocial mediators; Model C attempted to improve goodness of fit (GOF) of Model B by also controlling for baseline demographic, psychosocial, and smoking variables that were predictive of abstinence and their interactions with treatment assignment.

Model discrimination was assessed via the area under the curve (AUC) statistic,41 which measures the ability of a logistic regression model to correctly discriminate between a smoker and a nonsmoker based on their covariate profile (AUC = .50 corresponds to no better than chance). Model calibration (agreement between observed and fitted values) was assessed via the GOF statistic,42 with p values near 1.0 being desirable.

Moderation Analyses

Effect modification analyses were conducted by fitting interactions between treatment and prespecified moderators. The latter were examined in groups (demographic, smoking, and psychosocial) using forward selection. If a variable did not moderate the treatment-outcome relationship but appeared prognostic of outcome, it was retained in the model for its potential to improve calibration. We note that our analyses do not address moderated-mediation (i.e., moderation of intervention effects on the mediators by baseline characteristics, moderation of mediator effects on abstinence rates by study arm), which is beyond the scope of this article.

Covariate Standardization

In Tables 3 and 4, all variables appear in standardized form, centered by their mean, and scaled by their standard deviation (SD) reported in Table 1. For psychosocial mediators, a common standardization by the baseline SD was employed for both baseline values and 3-month change scores to allow us to compare the effect on abstinence of being 1 SD unit above the mediator mean at baseline, with the effect of a comparable 1 SD increase in the mediator from baseline to 3-month follow-up. Hence, all standardized mediator trajectories have a common starting point at the origin, with change measured in baseline SD units. Due to skewness, 3-month Web site utilization metrics in Table 4 were instead centered by the median and scaled by the distance from the median to the third quartile in the full sample, for example, from 2 to 6 logins across study arms. Telephone calls were left unstandardized.

Table 3.

Action Theory Mediation Tests: Logistic Regression Models for 3-Month Change in Putative Psychosocial Mediators (N = 1,236)

| Coefficient | Smoking Temptations Inventory | Smoking Temptations Inventory | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | LCL | UCL | p | Beta | LCL | UCL | p | |

| BI | −1.17 | −1.31 | −1.04 | <.001 | −1.21 | −1.34 | −1.08 | <.001 |

| EI vs. BI | −0.01 | −0.21 | 0.19 | .909 | 0.14 | −0.06 | 0.34 | .168 |

| EI+P vs BI | −0.54 | −0.74 | −0.35 | <.001 | −0.08 | −0.43 | 0.27 | .661 |

| EI+P vs EI | −0.53 | −0.74 | −0.33 | <.001 | −0.22 | −0.57 | 0.14 | .228 |

| Baseline tempt | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.68 | <.001 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.69 | <.001 |

| log (1+ logins) | −0.19 | −0.25 | −0.13 | <.001 | ||||

| Calls: linear | −0.11 | −0.30 | 0.07 | .229 | ||||

| Calls: quadratic | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | .532 | ||||

| Smoking Confidence Inventory | Smoking Confidence Inventory | |||||||

| Beta | LCL | UCL | p | Beta | LCL | UCL | p | |

| BI | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.47 | <.001 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.50 | <.001 |

| EI vs BI | −0.06 | −0.22 | 0.11 | .491 | −0.17 | −0.34 | 0.00 | .048 |

| EI + P vs BI | 0.36 | 0.20 | 0.53 | <.001 | −0.13 | −0.42 | 0.16 | .386 |

| EI + P vs EI | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.59 | <.001 | 0.04 | −0.26 | 0.34 | .802 |

| Baseline conf | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.59 | <.001 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.59 | <.001 |

| log (1+ logins) | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.19 | <.001 | ||||

| Calls: linear | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.35 | .015 | ||||

| Calls: quadratic | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.00 | .062 | ||||

| PIQ Positive Subscale | PIQ Positive Subscale | |||||||

| Beta | LCL | UCL | p | Beta | LCL | UCL | p | |

| BI | −1.10 | −1.21 | −0.98 | <.001 | −1.07 | −1.19 | −0.96 | <.001 |

| EI vs BI | 0.09 | −0.08 | 0.26 | .293 | 0.00 | −0.18 | 0.17 | .961 |

| EI + P vs BI | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.45 | .001 | 0.03 | −0.27 | 0.34 | .842 |

| EI + P vs EI | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.36 | .034 | 0.04 | −0.27 | 0.35 | .822 |

| Baseline PIQ-pos | 0.60 | 0.53 | 0.67 | <.001 | 0.60 | 0.53 | 0.67 | <.001 |

| log (1+ logins) | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.17 | <.001 | ||||

| Calls: linear | 0.10 | −0.06 | 0.26 | .228 | ||||

| Calls: quadratic | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 | .259 | ||||

| PIQ Negative Subscale | PIQ Negative Subscale | |||||||

| Beta | LCL | UCL | p | Beta | LCL | UCL | p | |

| BI | −0.28 | −0.35 | −0.20 | <.001 | −0.29 | −0.37 | −0.21 | <.001 |

| EI vs BI | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.10 | .917 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.16 | .380 |

| EI + P vs BI | −0.11 | −0.22 | 0.00 | .048 | 0.01 | −0.19 | 0.21 | .946 |

| EI + P vs EI | −0.10 | −0.22 | 0.01 | .068 | −0.04 | −0.25 | 0.16 | .671 |

| Baseline PIQ-neg | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.58 | <.001 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.57 | <.001 |

| log (1+ logins) | −0.07 | −0.10 | −0.04 | <.001 | ||||

| Calls: linear | −0.01 | −0.11 | 0.09 | .855 | ||||

| Calls: quadratic | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .939 |

Table 4.

Conceptual Theory Mediation Tests: Logistic Regression Models for 30-Day ppa at 3 Months (N = 1,236)

| | Model A | Model B | Model C | | | | | | | | | | | | ------------------------------ | ------- | ------- | ---- | ----- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ----- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ----- | | Coefficient | OR | LCL | UCL | p | OR | LCL | UCL | p | OR | LCL | UCL | p | | BI | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.20 | <.001 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.10 | <.001 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.09 | <.001 | | EI vs BI | 0.74 | 0.48 | 1.14 | .173 | 0.91 | 0.53 | 1.57 | .741 | 0.94 | 0.53 | 1.65 | .827 | | EI + P vs BI | 0.87 | 0.42 | 1.81 | .709 | 0.99 | 0.40 | 2.43 | .980 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 2.63 | .995 | | EI + P vs EI | 1.18 | 0.56 | 2.48 | .671 | 1.08 | 0.44 | 2.70 | .863 | 1.07 | 0.40 | 2.84 | .895 | | log (1+ logins) | 1.48 | 1.32 | 1.65 | <.001 | 1.23 | 1.06 | 1.41 | .005 | 1.22 | 1.05 | 1.41 | .009 | | Calls: linear | 1.50 | 1.06 | 2.13 | .022 | 1.35 | 0.88 | 2.09 | .173 | 1.42 | 0.89 | 2.26 | .146 | | Calls: quadratic | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.99 | .039 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 1.02 | .162 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 1.01 | .114 | | Baseline tempt | | | | | 0.74 | 0.58 | 0.94 | .016 | 0.72 | 0.56 | 0.94 | .014 | | Baseline conf | | | | | 1.68 | 1.25 | 2.27 | .001 | 1.87 | 1.38 | 2.54 | <.001 | | Baseline PIQ-pos | | | | | 1.12 | 0.90 | 1.40 | .297 | 1.06 | 0.85 | 1.33 | .604 | | Baseline PIQ-neg | | | | | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.84 | .001 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.92 | .011 | | Change in tempt | | | | | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.60 | <.001 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.60 | <.001 | | Change in conf | | | | | 2.01 | 1.58 | 2.56 | <.001 | 2.30 | 1.78 | 2.96 | <.001 | | Change in PIQ-pos | | | | | 1.25 | 1.04 | 1.50 | .018 | 1.26 | 1.04 | 1.52 | .018 | | Change in PIQ-neg | | | | | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.80 | <.001 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.82 | .001 | | Age | | | | | | | | | 1.23 | 1.01 | 1.51 | .044 | | Family income > $40,000 | | | | | | | | | 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.93 | .023 | | Employment (full time vs. not) | | | | | | | | | 1.94 | 1.18 | 3.16 | .008 | | Social network diversity | | | | | | | | | 1.38 | 1.10 | 1.73 | .005 | | Baseline CPD | | | | | | | | | 0.86 | 0.57 | 1.28 | .455 | | Baseline CPD: (EI vs BI) | | | | | | | | | 1.67 | 0.96 | 2.90 | .071 | | Baseline CPD: (EI + P vs BI) | | | | | | | | | 1.97 | 1.16 | 3.32 | .012 | | Baseline CPD: (EI + P vs EI) | | | | | | | | | 1.18 | 0.71 | 1.96 | .518 | | Goodness of fit | | | | .476 | | | | .108 | | | | .660 | | Area under the curve | | | | .700 | | | | .922 | | | | .924 |

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 1,236)

| Variable | Baseline | 3-month change |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, M (SD) | 36.2 (10.9) | |

| Gender, female N (%) | 680 (55.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | ||

| White | 1081 (87.5) | |

| Black | 98 (7.9) | |

| Asian | 35 (2.8) | |

| Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander | 5 (0.4) | |

| American Indian, Alaskan Native | 17 (1.4) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, N (%) | 45 (3.6) | |

| Education, N (%) | ||

| High school or less | 258 (20.9) | |

| Some college | 561 (45.4) | |

| College degree or higher | 417 (33.7) | |

| Full-time employment, N (%) | 877 (71.0) | |

| Family income < $40,000, N (%) | 544 (44.0) | |

| Married or cohabiting, N (%) | 727 (58.8) | |

| Smoking variables | ||

| Cigarettes per day, M (SD) | 19.7 (9.7) | |

| Past year quit attempts, M (SD) | 3.3 (8.5) | |

| Stage of change, N (%) | ||

| Precontemplation or contemplation | 147 (11.9) | |

| Preparation | 1089 (88.1) | |

| Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, M (SD) | 5.0 (2.4) | |

| Other smokers in house, N (%) | 242 (19.6) | |

| Health status variables | ||

| Smoking-related illness, N (%) | 736 (59.5) | |

| Body mass index, N (%) | ||

| Underweight or normal weight | 521 (42.2) | |

| Overweight or obese | 715 (57.8) | |

| Psychosocial variables | ||

| Social network diversity, M (SD) | 5.53 (1.81) | |

| Social network size, M (SD) | 23.0 (18.0) | |

| Partner Interaction Questionnaire, M (SD) | ||

| Positive subscale | 9.78 (2.29) | −2.24 (3.03) |

| Negative subscale | 5.95 (4.20) | −1.32 (3.93) |

| Smoking Temptations Inventory, M (SD) | 3.91 (0.49) | −0.66 (0.75) |

| Smoking Situations Confidence Inventory, M (SD) | 2.81 (0.58) | 0.26 (0.76) |

| Perceived Stress Scale, M (SD) | 6.16 (3.19) | −0.66 (3.18) |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale, M (SD) | 9.08 (5.67) | −0.98 (5.65) |

Results

Sample Description

The iQUITT Study randomized 2,005 participants: BI = 679, EI = 651, and EI + P = 675. To ensure that changes in the estimates of the treatment effects were solely due to the incorporation of additional variables in the model, and not due to different missing data patterns between models, a common analytic sample of 1,236 subjects (BI = 444, EI = 401, EI + P = 391) was employed in these analyses. The 769 missing observations (38.4% missing data) were due to either loss-to-follow-up (N = 475, 23.7% missing data) as reported in the parent study15 or additional missingness in the covariates of the most comprehensive Model C (N = 294, 14.7%), the latter driven primarily by missingness in PIQ change scores due to participants reporting that no one was involved in their efforts to quit. Despite the loss of an additional N = 294 observations, 30-day ppa rates at 3 months in the current sample compare well with those reported in Graham and colleagues15: 12.4%, 13.7%, and 27.2% for BI, EI, and EI + P, respectively, in the current sample versus 11.6%, 13.6%, and 25.9%, respectively, in the original responder-only sample.

As previously reported,15 participant characteristics at baseline associated with follow-up completion included older age, female sex, graduation from a 4-year college, and a high level of social network diversity. These characteristics were reflected in analyses comparing the 3-month analytic sample (N = 1,236) and excluded cases (N = 769). Participants included in these analyses were more likely to be female (55.0% vs. 44.7%, p < .001), to have graduated from a 4-year college (33.7% vs. 25.6%, p = .001), to have a higher level of social network diversity (5.5±1.8 vs. 5.2±1.9, p < .001), and to be married/cohabitating (58.8% vs. 51.5%, p < .001). There were no differences on age or any other baseline variables examined (Table 1). Examination of the 6-month follow-up completers reduced the available sample (N = 1,091). Compared with excluded cases (N = 914), participants were also more likely to be female (56.6% vs. 44.4%, p < .001), to have graduated from a 4-year college (34.4% vs. 26.1%, p < .001), to have a higher level of social network diversity (5.5±1.8 vs. 5.3±1.9, p < .001), and to be married/cohabitating (59.7% vs. 51.6%, p < .001). They were also more likely to be older (36.4±11.0 vs. 35.2±10.6, p < .01).

Action Theory Tests: Treatment Utilization at 3 Months

Web site utilization was higher in the EI and EI + P compared with BI for logins, time on site, and page views (all _p_s < .001), but no significant differences emerged between EI versus EI + P (p = .274). In particular, BI participants made 2.27 logins (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.67–3.09), whereas the number of logins for EI and EI + P over the same time period were 6–7 times higher (EI vs. BI: login ratio = 6.24, 95% CI = 4.47–8.71; EI + P vs. BI: login ratio = 6.90, 95% CI = 4.95–9.61). Of note, approximately 20% of participants in each arm never logged into their assigned Web site (Table 2). There were treatment group differences in most of the Content Read metrics, with BI participants more likely to have read the Medication and Quitting Guides, but less likely to have read FAQs. About quarter of EI + P participants did not complete any telephone counseling calls. The median number of phone calls completed was 3 (interquartile range = 0–5).

Table 2.

Common Web Site Utilization Metrics at 3 Months by Study Arm (N = 1,236)

| Web site utilization | BI (N = 444) | EI (N = 401) | EI + P (N = 391) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of logins, median (IQR) | 1 (1–3) | 3 (1–11) | 4 (1–13) | <.001 |

| 0 logins, N (%) | 73 (16.4) | 81 (20.2) | 72 (18.4) | <.001 |

| 1–2 logins, N (%) | 329 (74.1) | 150 (37.4) | 139 (35.5) | |

| 3+ logins, N (%) | 42 (9.5) | 170 (42.4) | 180 (46.0) | |

| Minutes on site, median (IQR) | 9.9 (2–23) | 29 (4–105) | 36 (6–151) | <.001 |

| Number of page views, median (IQR) | 18 (5–33) | 55 (9–176) | 61 (13–234) | <.001 |

| Content read (0–4 possible), M (SD) | 1.34 (1.20) | 1.03 (1.27) | 1.18 (1.26) | .001 |

| Read FAQ, N (%) | 114 (25.7) | 120 (29.9) | 138 (35.3) | .010 |

| Read medication guide, N (%) | 82 (18.5) | 54 (13.5) | 50 (12.8) | .041 |

| Read quitting guide, N (%) | 281 (63.3) | 161 (40.1) | 183 (46.8) | <.001 |

| Used national directory, N (%) | 119 (26.8) | 80 (20.0) | 92 (23.5) | .064 |

Action Theory Tests: Psychosocial Constructs at 3 Months

Action Theory tests (Table 3) examined the overall impact of each of the interventions on purported psychosocial mediators, and then decomposed it into direct effects and indirect effects through increased treatment utilization. In terms of modeling overall intervention effects (left column), all study arms experienced drops in Smoking Temptations from baseline to 3 months, but intervention effects only attained significance for EI + P versus BI (δ = −0.54, p < .001). This additional ½ SD drop among EI + P versus BI subjects corresponds to a moderate effect size.43 A similar picture emerged for Smoking Confidence, with all three arms experiencing increases over time. No significant EI versus BI difference in change scores was detected (δ = −0.06, p = .491), whereas EI + P registered higher increases in confidence than BI (δ = 0.36, p < .001), albeit ones in the small-to-moderate range. The PIQ positive subscale decreased in all three arms from baseline to 3 months. This drop was of similar magnitude in BI and EI (δ = 0.09, p = .293), but was attenuated in EI + P compared with BI (δ = 0.28, p < .001). In that sense, EI + P appeared to arrest the sharp drop in the values of this protective factor (0.82–1.10 SD) that occurred in the BI and EI arms. The PIQ negative subscale also decreased in all three arms, with no EI versus BI differences (δ = −0.01, p = .917), but a slightly sharper drop within EI + P versus BI (δ = −0.11, p = .048).

Decomposition of the overall treatment effects into direct and indirect components (right column) showed that differential EI + P versus BI changes in Smoking Temptations as well as in both PIQ positive and negative subscales could be fully accounted for via increased Web site utilization, with no additional benefit due to telephone support. In contrast, differential increases in Smoking Confidence in EI + P versus BI were associated with increased Web site utilization and the availability of telephone support. The benefit of telephone support plateaued at around five calls; for the quarter of EI + P participants that completed more than five calls, additional phone calls were associated with lower levels of Smoking Confidence.

Conceptual Theory Tests: 3-Month Analyses

Overall intervention effects on 30-day ppa at 3 months were not statistically significant for EI versus BI (odds ratio [_OR_] = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.75–1.68, p = .567), offering little scope for mediation analysis, whereas the EI + P versus BI difference was significant (OR = 2.66, 95% CI = 1.86–3.82, p < .001) and amenable to mediation testing. Conceptual Theory mediation tests are summarized in Table 4, which presents three distinct outcome models in increasing order of complexity.

Model A decomposes overall intervention effects into direct intervention effects as well as indirect effects due to increased treatment utilization. After accounting for treatment utilization, both the EI versus BI and EI + P versus BI _OR_s were no longer statistically significant, signaling complete mediation. Instead, statistically significant indirect effects were obtained for Web site utilization across all three study arms (p < .001), with increases in the number of logins from 2 to 6 (median third quartile) associated with higher abstinence rates (OR = 1.48; 95% CI = 1.32–1.65). Significant linear (OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.06–2.13) and quadratic (OR = 0.95, 95% = 0.91–0.99) effects were estimated for telephone counseling, consistent with large initial increases in abstinence rates that plateaued at five calls and then decreased.

Model B adds baseline values and 3-month changes in the four putative psychosocial mediators to the covariate set in Model A. Increases in Smoking Confidence and the PIQ positive subscale were both positively associated with smoking abstinence (_p_s < .02), as were decreases in Smoking Temptations (p < .001) and the PIQ negative subscale (p = .001). In particular, higher Smoking Temptations scores at baseline lowered the odds of abstinence at 3 months (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.58–0.94), as did increases in Smoking Temptations from baseline to follow-up (OR = 0.50, 95% CI = 0.41–0.60). Therefore, low but stable Smoking Temptation scores appeared to be less beneficial than average scores that declined over time. Higher Smoking Confidence scores at baseline were associated with greater odds of abstinence (OR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.25–2.27), whereas comparable increases from baseline to follow-up doubled the odds of abstinence (OR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.58–2.56). Higher baseline levels of the PIQ positive subscale were not associated with 3-month abstinence rates (OR = 1.12; 95% CI = 0.90–1.40) but increases from baseline to follow-up increased the odds of abstinence (OR = 1.25, 95% CI = 1.04–1.50). Low baseline levels of the PIQ negative subscale were associated with lower odds of abstinence (OR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.50–0.84) as were decreases from baseline to follow-up (OR = 0.61; 95% CI = 0.47–0.80).

The addition of these psychosocial mediators deflated the effects of both treatment utilization components, but did not fully attenuate the corresponding _OR_s, suggesting the existence of additional meditational processes beyond those included in Model B. In particular, one quartile increases above the median from 2 to 6 logins remained associated with direct increases in the odds of abstinence by a quarter (OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.06–1.41), over and above any indirect login effects via changes in psychosocial mediators.

Conceptual Theory Tests: 6-Month Analyses

Without any further model search, a sequence of models identical to those presented in Table 4 was fit to a subset of the previously analyzed N = 1,236 participants for whom 6-month abstinence outcomes were also available (Supplementary Table 1). Although the decrease in sample size to N = 1,091 should have adversely affected power to detect mediation of the intervention effects on outcome, both the effect of increased Web site utilization and the changes in confidence and temptations remained highly significant (all _p_s < .001), with _OR_s that were either very similar to those observed at 3 months (Web site utilization) or attenuated by about 1/4 to 1/3 (Smoking Confidence and Temptations). Results on social support were more equivocal, with positive partner support remaining equally influential (_p_ < .006), but the effect size of negative partner support deflating by about 1/2 (_p_ = .093). Phone call effects and moderation of the intervention effects by baseline smoking rate were also attenuated at 6 months, failing to reach even nominal statistical significance thresholds (all _p_s > .05).

Moderator Analyses

Model B showed excellent discrimination (AUC = 0.922), but was not well calibrated (GOF X2(2) = 4.44, p = .108). Interaction analyses identified daily smoking as the only moderator of direct intervention effects on abstinence (X2(2) = 7.22, p = .027), with 1 SD increases above the average smoking rate at baseline associated with increased odds of abstinence in EI (OR = 1.67, 95% CI = 0.96–2.90) and EI + P (OR = 1.97, 95% CI = 1.16–3.32), but not in BI (OR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.57–1.28). Further, four baseline variables were identified as having significant main effects on smoking outcome. Older age was associated with higher odds of abstinence (OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.01–1.51). Despite being positively correlated (biserial ρ = 0.365), both full-time employment status and family income emerged as independent predictors of outcome: full-time employment almost doubled the odds of abstinence (OR = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.18–3.16) across income levels, whereas high family income lowered the odds of abstinence across employment groups (OR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.36–0.93). A higher level of social network diversity also increased the odds of abstinence (OR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.10–1.73). The addition of these prognostic factors to Model C resulted in a final model that retained excellent discrimination (AUC = 0.924) while also demonstrating adequate calibration (GOFX2(2) = 0.84, p = .660).

Discussion

The iQUITT Study examined a comprehensive range of mediator and moderator variables to better understand previously reported main outcomes. A priori hypotheses about mediators of the EI + P treatment effect observed at 3 months were fully supported. Relative to BI, EI + P positively impacted both metrics of self-efficacy (decreasing smoking temptations and increasing confidence), slowed the decline of positive support for quitting, and decreased negative interactions, either directly or indirectly via increased Web site utilization. It was also hypothesized that individual support and coaching from a telephone counselor added to a web-based intervention would further boost psychosocial mediators compared with the Internet-only conditions, but this hypothesis was only supported for confidence. In addition to these successful manipulation checks (Action tests), we confirmed that change in all four mediators affected abstinence rates in expected directions (Theory tests).

The fact that the direct effects of Web site utilization remained significant, after accounting for their indirect effects through four prespecified mediational processes, suggests the existence of additional mediation paths not captured by our model. Indeed, the importance of logins is consistent with other trials that have identified Web site utilization as an independent predictor of abstinence.18,44–46 Increasing Web site utilization and improving adherence to the core components of web-based interventions are a priority not only for smoking cessation programs but also for eHealth interventions broadly.47–49

Hypotheses regarding moderator variables were only partially supported. Baseline smoking rate was the only moderator of treatment effectiveness at 3 months, suggesting that heavier smokers benefited from the more extensive resources in EI and EI + P. Further, its effects appeared deflated at 6 months. Given the large sample size, the fact that no other variables emerged as moderators suggests that interventions were equally effective across subgroups. Protective factors included older age, full-time employment, and high social network diversity. Regarding the latter, social network analyses of “real-world networks” have demonstrated herd behavior,50 which is presumed to be due to the reinforcing processes in homophilous networks, where smokers primarily know smokers. Higher social network diversity may mitigate the effects of homophily to promote cessation.

Leverage points for improving intervention design may include increasing a smoker’s confidence in coping with smoking triggers and reducing temptations, bolstering the availability of positive support for cessation, and encouraging sustained Web site engagement. Though these findings are consistent with research in other treatment settings,51 the online environment offers a conceptually different approach to their implementation. The availability of large, heterophilous online social networks may be effective in increasing confidence and reducing temptations by providing first-hand accounts and advice about quitting and providing positive support and encouragement throughout the cessation process.52 Research examining the role of online social networks alone and in conjunction with pharmacotherapy in improving abstinence rates through these mediating processes is currently underway.22 Our results suggest that greater treatment engagement may differentially benefit heavier smokers, younger adults, and those with less social network diversity.

Results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, though the trial involved a large sample with more than 2,000 participants randomized to treatment, the generalizability of the results presented herein is limited by the available samples at each timepoint. Participants available for analysis at 3 and 6 months differed from those excluded on several demographic and psychosocial characteristics. Also, although smokers were recruited nationally, the study is limited in generalizability to those seeking cessation treatments on the Internet. Second, we can only be confident of the directionality of effects when analyzing 6-month outcomes; at 3 months, it is assumed that abstinence occurred as a result of changes in psychosocial mediators, but it may have preceded them. Third, our approach is based on a sequential ignorability assumption that ignores the fact that change in mediator levels is not assigned randomly across study groups.53 Despite these limitations, this is one of only a few studies of mediation and moderation in web-based cessation trials. This study is unique with regard to the comprehensive set of measures that included demographic, smoking, and psychosocial variables and automated intervention tracking metrics. Other strengths include a clearly delineated theoretical model and the ability to compare and contrast short-term effects on abstinence with those observed over a longer timeframe.

There remains a fundamental lack of understanding of the mechanisms of effectiveness of successful programs despite nearly two decades of research in online cessation interventions.4,54 To advance the science of Internet interventions and leverage their potential for broad reach and population level impact, future research should explicitly address the questions of “how” and “for whom.” Intervention approaches that explicitly and intentionally target theory-driven mediators and moderators of treatment effectiveness and that maximize engagement may help realize the potential impact of web-based cessation programs.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1 can be found online at http://www.ntr.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA104836).

Declaration of Interests

ALG, COC, RSN, and DBA are employees of Legacy, a nonprofit public health foundation that runs BecomeAnEX.org, an online tobacco cessation intervention. COC is now at Virginia Commonwealth University. NKC is an employee of MeYou Health LLC, whose parent company owns and operates QuitNet. DGT is a medical director for Health Initiatives at National Jewish Health, which operates the tobacco quitline, QuitLogix™. The study is registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT00282009). The funding agency had no involvement in the conduct of the study or preparation of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Data

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank Ye Fang and Jose Moreno for their assistance on this project.

References

- 1.Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediating effects in prevention studies. Eval Rev. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox S. Health Topics. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2011. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/HealthTopics.aspx. Accessed August 5, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Civljak M, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, Sheikh A, Car J. Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD007078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strecher VJ, Shiffman S, West R. Moderators and mediators of a web-based computer-tailored smoking cessation program among nicotine patch users. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:S95–S101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brendryen H, Drozd F, Kraft P. A digital smoking cessation program delivered through internet and cell phone without nicotine replacement (happy ending): randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danaher BG, Smolkowski K, Seeley JR, Severson HH. Mediators of a successful web-based smokeless tobacco cessation program. Addiction. 2008;103:1706–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wangberg SC, Nilsen O, Antypas K, Gram IT. Effect of tailoring in an internet-based intervention for smoking cessation: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danaher BG, Lichtenstein E, Andrews JA, Severson HH, Akers L, Barckley M. Women helping chewers: effects of partner support on 12-month tobacco abstinence in a smokeless tobacco cessation trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:332–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shahab L, McEwen A. Online support for smoking cessation: a systematic review of the literature. Addiction. 2009;104:1792–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etter JF. Comparing the efficacy of two Internet-based, computer-tailored smoking cessation programs: a randomized trial. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabius V, Pike KJ, Wiatrek D, McAlister AL. Comparing internet assistance for smoking cessation: 13-month follow-up of a six-arm randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muñoz RF, Lenert LL, Delucchi K, et al. Toward evidence-based Internet interventions: a Spanish/English Web site for international smoking cessation trials. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham AL, Bock BC, Cobb NK, Niaura R, Abrams DB. Characteristics of smokers reached and recruited to an internet smoking cessation trial: a case of denominators. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:S43–S48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham AL, Cobb NK, Papandonatos GD, et al. A randomized trial of Internet and telephone treatment for smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: Freeman and Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen S. Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychol. 1988;7:269–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cobb NK, Graham AL, Bock BC, Papandonatos G, Abrams DB. Initial evaluation of a real-world Internet smoking cessation system. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7:207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham AL, Cobb N, Bock B, Abrams DB. Utilization and Short-term Smoking Outcomes Among Global Users of Quitnet.com. Paper presented at: 12th World Conference on Tobacco or Health, Helsinki, Finland; August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cobb NK, Graham AL, Abrams DB. Social network structure of a large online community for smoking cessation. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1282–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham AL, Cha S, Papandonatos GD, et al. Improving adherence to web-based cessation programs: a randomized controlled trial study protocol. Trials. 2013;14:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muñoz RF, Barrera AZ, Delucchi K, Penilla C, Torres LD, Pérez-Stable EJ. International Spanish/English Internet smoking cessation trial yields 20% abstinence rates at 1 year. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:1025–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pike KJ, Rabius V, McAlister A, Geiger A. American Cancer Society’s QuitLink: randomized trial of Internet assistance. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strecher VJ, McClure J, Alexander G, et al. The role of engagement in a tailored web-based smoking cessation program: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strecher VJ, Shiffman S, West R. Randomized controlled trial of a web-based computer-tailored smoking cessation program as a supplement to nicotine patch therapy. Addiction. 2005;100:682–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swartz LH, Noell JW, Schroeder SW, Ary DV. A randomised control study of a fully automated internet based smoking cessation programme. Tob Control. 2006;15:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velicer WF, Diclemente CC, Rossi JS, Prochaska JO. Relapse situations and self-efficacy: an integrative model. Addict Behav. 1990;15:271–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen S, Lichtenstein E. Partner behaviors that support quitting smoking. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham AL, Papandonatos GD. Reliability of internet- versus telephone-administered questionnaires in a diverse sample of smokers. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System - Survey Questions. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a new self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP, Rabin BS, Gwaltney JM., Jr Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;277:1940–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown RL, Leonard T, Saunders LA, Papasouliotis O. A two-item conjoint screen for alcohol and other drug problems. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cerin E, Mackinnon DP. A commentary on current practice in mediating variable analyses in behavioural nutrition and physical activity. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:1182–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papandonatos GD, Williams DM, Jennings EG, et al. Mediators of physical activity behavior change: findings from a 12-month randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2012;31:512–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Refining Inferences About Mediated Effects in Studies of Personality and Social Psychology Processes. Paper presented at: 11th Annual Meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Las Vegas, NV; January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15:361–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 44.An LC, Schillo BA, Saul JE, et al. Utilization of smoking cessation informational, interactive, and online community resources as predictors of abstinence: cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson A, Graham AL, Cobb N, et al. Engagement promotes abstinence in a web-based cessation intervention: cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15, e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saul JE, Schillo BA, Evered S, et al. Impact of a statewide Internet-based tobacco cessation intervention. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donkin L, Christensen H, Naismith SL, Neal B, Hickie IB, Glozier N. A systematic review of the impact of adherence on the effectiveness of e-therapies. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crutzen R, de Nooijer J, Brouwer W, Oenema A, Brug J, de Vries NK. Strategies to facilitate exposure to internet-delivered health behavior change interventions aimed at adolescents or young adults: a systematic review. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38:49–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HC, Van Gemert-Pijnen JE. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. The New Engl J Med. 2008;358:2249–2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abrams DB, Niaura R, Brown RA, Emmons KM, Goldstein MG, Monti PM. The Tobacco Dependence Treatment Handbook: A Guide to Best Practices. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cobb NK, Graham AL, Byron MJ, Niaura RS, Abrams DB. Online social networks and smoking cessation: a scientific research agenda. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychiatr Med. 2010;15:309–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mathieu E, McGeechan K, Barratt A, Herbert R. Internet-based randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc, 2013;20:568–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Data