Targeting HMGB1 in inflammation (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2015 Aug 12.

Published in final edited form as: Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 Dec 3;1799(0):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.11.019

Abstract

High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a highly conserved, ubiquitous protein present in the nuclei and cytoplasm of nearly all cell types, is a necessary and sufficient mediator of inflammation during sterile and infection-associated responses. Elevated levels of HMGB1 in serum and tissues occur during sterile tissue injury and during infection, and targeting HMGB1 with antibodies or specific antagonists is protective in established preclinical inflammatory disease models including lethal endotoxemia or sepsis, collagen-induced arthritis, and ischemia–reperfusion induced tissue injury. Future advances in this field will stem from understanding the biological basis for the success of targeting HMGB1 to therapeutic improvement in the treatment of inflammation, infection and ischemia–reperfusion induced injury.

Keywords: Cytokine, HMGB1, Inflammation, Immune response, Receptor

1. Introduction

Immunity, the ability to resist invasion, can be either inherited (innate) or acquired (adaptive). Cells of the innate immune system, including monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils are on the front line in the host response to infection, invasion, and injury. During infection, innate immunity is activated by foreign molecular products, termed pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) including lipopolysaccharide (LPS), double stranded RNA, CpG DNA, and enterotoxins. During sterile injury or ischemia, these same cells are activated by exposure to damage associated molecular pattern (DAMPs), including heat shock proteins, uric acid, annexins, and IL-1alpha. Activation of innate immunity initiates the production and release of cytokines, proteins that mediate diverse metabolic and immunological responses in other cells [1]. Cytokine release is necessary and sufficient to initiate inflammation, the syndrome of pain, swelling, hyperemia, and hyperthermia that heralds the onset of both infection and sterile injury. The magnitude of the cytokine response is tightly regulated, because the over-production of cytokines can directly mediate the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, and if severe enough, lethal shock and tissue injury [2]. The “cytokine theory of disease,” which is the paradigm that cytokines are both necessary and sufficient to cause disease, has been validated by the clinical success of selectively targeting individual cytokines to therapeutic advantage [3]. For example, anti-TNF antibodies are effective in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis, and strategies targeting IL-1 and Il-6 are also widely used [4,5].

Despite these advances, not all patients respond to currently available cytokine based therapeutics; and additional experimental therapeutic approaches are necessary, and being pursued. Accordingly, with our colleagues in the early 1990s, we initiated a search for previously unrecognized cytokine mediators of inflammation released by exposing macrophages to the prototypical PAMP, Gram-negative lipopolysaccharide. This effort culminated in the isolation and identification of HMGB1 as an inducible macrophage secreted protein that mediated endotoxin lethality and activated innate immune cells to produce cytokines [6,7]. The discovery that a ubiquitous, 30 KDa nuclear DNA-binding protein had roles not only in stabilizing DNA structure and mediating neurite outgrowth, but also in mediating and modulating the inflammatory response to invasion, enabled development of numerous strategies to selectively neutralize the activity of HMGB1 with antibodies or other agents which suppress inflammation in standardized preclinical studies. Not surprisingly, like other inducible inflammatory mediators, the activities of HMGB1 are synergistically increased by interaction with LPS, CpG DNA, IL-1, and other cytokines [8].

An important question in the biology of inflammation is how can infectious and sterile inflammation initiate nearly identical physiological responses? The answer came from the discovery by Billiar et al. that in addition to being a therapeutic target for diseases initiated by PAMPs, HMGB1 is also necessary for the pathogenesis of ischemia and sterile, non-invasive inflammation [9–11]. Ischemia and cell damage lead to the passive release of endogenous HMGB1, which in turn functions to mediate cytokine release, inflammation, and tissue injury by activating innate immunity through signal transduction in Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). HMGB1 thus mediates inflammation by activating innate immune receptors during sterile injury, which are comparable to activation by PAMPs. Here we focus on reviewing the pathogenic role of HMGB1 in sterile and infection-induced inflammation, its activities in preclinical disease models, and methods to modulate its activity to therapeutic advantage.

2. Cytokine activity of HMGB1

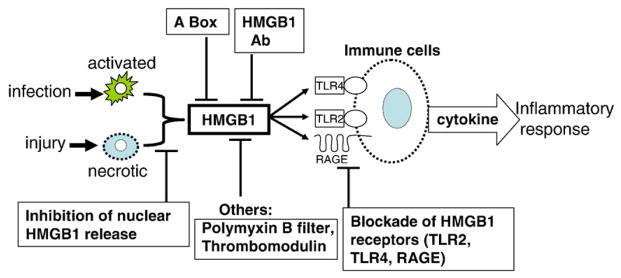

HMGB1 can be actively released from immune cells including macrophages, monocytes, NK cells, dendritic cells, endothelial cells, and platelets [6,7,12,13]. It is also passively released from necrotic or damaged cells [10,14–16]. Both mechanisms can produce the release of significant amounts of extracellular HMGB1. Although apoptotic cells release significantly less HMGB1 as compared to necrotic cells, macrophage engulfment of apoptotic cells leads to significant HMGB1 release [17–19]. Administration of HMGB1 to normal animals produces systemic inflammatory responses including fever, weight loss and anorexia, acute lung injury, epithelial barrier dysfunction, arthritis and death [16]. Anti-HMGB1 treatment, with either antibodies, specific antagonists or other pharmacological agents, is beneficial in many preclinical inflammatory diseases models, ameliorates severity of diseases and reduces mortality (summarized in Table 1 and illustrated in Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Therapies targeting HMGB1 in preclinical disease models.

| Mode of anti-HMGB1 | Disease model, effects, and species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-HMGB1 antibodies | Endotoxemia: polyclonal anti-HMGB1 antibodies (pAb) treatment improved survival in mice. | [6,47] |

| Sepsis induced by cecal perforation: both pAb and monoclonal antibody (mAb) treatment improved survival in mice. | [17,21,55] | |

| Gastro-intestinal disorders: pAb reversed LPS-induced gut barrier dysfunction in rats; reduced inflammation in murine colitis. | [69,70] | |

| Pancreatitis: pAb attenuated inflammation in acute pancreatitis in mice. | [74] | |

| Respiratory disorders: pAb ameliorated LPS-induced acute lung injury; ventilator-induced lung injury; pulmonary fibrosis in mice. | [79–83] | |

| Arthritis: pAb treatment attenuated arthritis and inflammation in collagen-induced arthritis in rodents. | [87–88] | |

| Hemorrhagic shock (HS): pAb improved survival and lung function after HS in mice. | [81,99] | |

| Stroke: MAb or pAb treatment ameliorated brain infarction in rats. | [110,111] | |

| Ischemia–reperfusion injury: pAb ameliorated hepatic ischemia–reperfusion injury in mice. | [10] | |

| HMGB1 A box | Endotoxemia and sepsis induced by cecal perforation in mice: A box treatment improved survival in these models. | [21] |

| Pancreatitis: A box protected organ damage caused by pancreatitis in mice. | [75] | |

| Respiratory disorders. A box reduced LPS-induced lung injury in mice. | [84] | |

| Arthritis. A box attenuated collagen-induced arthritis in rodents. | [87] | |

| Stroke: A box ameliorated ischemia brain damage. | [111] | |

| Ischemia–reperfusion injury: A box reduced damage in ischemia–reperfusion injury of heart in mice. | [15] | |

| Transplantation. A box prolonged cardiac allograft survival in rodents. | [113] | |

| Others: blockade of RAGE–HMGB1 signaling | Sepsis induced by cecal perforation: improved survival in mice. | [26,56] |

| Gastro-intestinal disorders: ameliorated intestinal barrier function after hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation in mice. | [71] | |

| Arthritis: reduced severity of arthritis in rodents. | [93] | |

| Reduce nuclear HMGB1 release | Endotoxemia: improved survival, reduced end organ damage in mice. | [51,52,114,115] |

| Sepsis induced by cecal perforation: improved survival in mice. | [51,52,57–63] | |

| Pancreatitis: attenuated organ damage in rodents. | [76–78] | |

| Arthritis: attenuated arthritis and inflammation in collagen-induced arthritis in rodents. | [94–96] | |

| Polymyxin B filter | Sepsis: improved outcome in sepsis patients and piglets by removing HMGB1 from circulation. | [65,66] |

| Respiratory disorder: reduced inflammation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. | [85] | |

| Thrombomodulin | Endotoxemia: improved survival in rodents. | [47] |

| Respiratory disorder: ameliorated injury-induced lung injury in mice. | [53,86] | |

| Arthritis: protected against arthritis in mice. | [97] |

Fig. 1.

Strategies targeting HMGB1 in inflammatory diseases. HMGB1 can be actively secreted by innate immune cells in response to exogenous microbial products from infection; or passively released from injured or necrotic cells. Exogenous HMGB1 can act via receptors (RAGE, TLR2, and TLR4) to stimulate the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and elicit injurious inflammatory responses. Anti-HMGB1 treatment is beneficial in many preclinical disease models as described in the text by using anti-HMGB1 antibodies, specific HMGB1 antagonist A box, blockade of HMGB1 receptors, or other pharmacological agents partially through targeting HMGB1.

The inflammatory activity of HMGB1 is dependent upon the oxidation status of cysteine 106 residing within the B box DNA-binding domain of HMGB1, a region that is critical for stimulating cytokine release and inflammation [20–22]. Recent studies have revealed that cysteine 106 is critically important for HMGB1 binding to TLR4/MD2, as revealed by using HMGB1 protein with a point mutation at 106 cysteine (replaced by alanine) and by using synthetic 20-mer peptide covering 106 cysteine (our unpublished data). Together, these results indicate that the cysteine 106 is required for HMGB1 signaling through TLR4 to stimulate cytokine release and inflammation.

3. Receptors mediating HMGB1 activity

Once released into the extracellular milieu, HMGB1 can bind to cell surface receptors including the RAGE, TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 [8,16,23]. HMGB1 interaction with these receptors transduces intracellular signals and mediates cellular responses including chemotactic cell movement and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF and IL-1) in vitro; and causes fever, epithelia barrier dysfunction, and acute inflammation in vivo.

3.1. In vivo

3.1.1. RAGE

RAGE is a transmembrane protein and a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. RAGE is expressed in endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, neurons and macrophages/monocytes [24]. In vivo experiments indicate that HMGB1/RAGE interaction may be important in tumor formation and proliferation, because blocking RAGE and HMGB1 can decrease tumor growth and metastasis in mice [25].

Anti-RAGE antibodies reduced HMGB1 expression in the diagram during sepsis induced by cecal perforation. Neutralizing RAGE and HMGB1 by antibodies attenuated diaphragm dysfunction in septic rats induced by cecal perforation [26].

3.1.2. TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) has been implicated as the critical receptor mediating the inflammatory activity of HMGB1. HMGB1 is a mediator in ischemia and reperfusion damage in liver, heart, and kidney [10,15,27,28]. Ischemia followed by reperfusion leads to severe organ injury and dysfunction. Reperfusion activates innate immune responses and induces cytokine release which mediates the development of systemic inflammatory responses and further tissue damage. Tsung et al. showed that hepatic HMGB1 levels are increased rapidly during ischemia–reperfusion injury, rise within 1 h after reperfusion, and remained elevated for up to 24 h in animal models [10]. Anti-HMGB1 antibodies failed to provide protection in TLR4 defective C3H/HeJ mice, but successfully reduced damage in C3H/OuJ mice, indicating that TLR4 is involved in this HMGB1 mediated hepatic injury [10]. Mechanistically, HMGB1 release during liver ischemia–reperfusion involves TLR4-dependent production of reactive oxygen species and calcium-mediated signaling [27]. In agreement with these observations, TLR4 is implicated as a receptor mediating ischemia–reperfusion disorders in the kidney and cold ischemia–reperfusion of the heart [28–30].

3.2. In vitro

3.2.1. RAGE

HMGB1 binds to RAGE in a concentration-dependent manner [31]. As a receptor of multiple ligands, RAGE has also been implicated as a receptor mediating the chemotaxis and cytokine activity of HMGB1 in macrophages and tumor cells [8,16,32,33]. A structure/functional analysis revealed that amino acids 150–183 in the C terminus of HMGB1 are responsible for RAGE binding [34]. Anti-RAGE antibodies partially inhibit HMGB1-induced chemokine and cytokine release in endothelial cells [35]. Hence, HMGB1 interacts with RAGE, but interaction with TLR2 and TLR4 are required for HMGB1 signaling in macrophages as described below.

3.2.2. TLR4

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are highly conserved proteins that activate innate immune cells in response to a variety of endogenous and exogenous stimuli. Two of the TLRs have been reported to be involved in HMGB1 signaling: TLR2 and TLR4. TLR4 is suggested as the primary receptor in mediating macrophage activation, cytokine release and tissue injury [10,27,36–38]. HMGB1 signals via TLR4 in human whole blood, and primary macrophages to induce cytokine release. HMGB1-stimulated TNF release is inhibited in macrophages obtained from MyD88 (a transducer for TLR protein signaling) or TLR4 knock out mice, but not from TLR2 knock out mice or wild type controls [39]. HMGB1 signals via TLR4 to activate tumor antigen-specific T cell immunity in both mice and humans [36]. In vivo studies of ischemia–reperfusion suggest a role of TLR4 in HMGB1 mediated tissue injury. In vitro, HMGB1 directs inflammatory responses mediated by dendritic cells in ischemia–reperfusion models by enhancing TLR4 expression [37].

3.2.3. TLR2

HMGB1 can also elicit cellular signaling through TLR2. Using dominant negative constructs to block MyD 88, TLR2 or TLR4 genes in macrophages in vitro, Park et al. observed that TLR2 and TLR4 are involved in cellular activation by HMGB1 [40]. In human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells transfected with TLR2, TLR4, or vector alone, HMGB1 effectively induces IL-8 release only from TLR2 over-expressing cells. Consistently, anti-TLR2 antibodies dose-dependently attenuate HMGB1-induced IL-8 release in HEK/TLR2-expressing cells and markedly reduce HMGB1 cell surface binding on murine macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells [39]. Fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) and immuno-precipitation analyses in macrophages showed that HMGB1 binds to TLR2 and TLR4 on cell surface, but not RAGE [41].

4. HMGB1 links sterile injury and infection-induced immunity

The discovery of the cytokine role of HMGB1 has led to a new understanding of sterile and infection-induced inflammation. HMGB1 produced by cell injury activates innate immunity, and this response is qualitatively indistinguishable from the response activated from infectious insult. HMGB1 activates these responses by signaling through the same receptor family that is activated by exogenous agents. Low levels of HMGB1 are present in the serum of healthy subjects (10–30 ng/ml) [42] and in unstimulated cell culture supernatant. These levels do not cause inflammation. Large amounts of HMGB1 produced during severe tissue injury or cell death (i.e. crush injury) are inflammatory and associated with fever, anorexia, epithelial leakage syndrome and organ failure [8,16]. HMGB1 derived from Chinese hamster ovary mammalian cells genetically engineered to continuously secrete HMGB1 stimulates cytokine release from human macrophages, and neutralizing monoclonal anti-HMGB1 antibodies inhibit this activity [43]. Further, small amounts of HMGB1 that are ubiquitously present in the extracellular milieu synergistically enhance the inflammatory response induced by bacterial products. For example, binding of HMGB1 to LPS, CpG DNA, viral RNA and IL-1 all significantly increase the inflammatory activity of HMGB1, which can be inhibited with anti-HMGB1 antibodies [8,44]. The release of large quantities of HMGB1 during endotoxemia or infection can be lethal [6,21].

5. HMGB1 in diseases and studies targeting HMGB1 in the treatment of preclinical diseases

Treatment with inhibitors of HMGB1 activity is beneficial and reduces inflammation in dozens of preclinical animal studies. Here we discuss the therapeutic strategies that have been proven effective by inhibiting HMGB1 activity in a wide range of preclinical disease models (Table 1 and Fig. 1). We focus on studies using anti-HMGB1 antibodies or specific HMGB1 antagonist A box. Other pharmacological agents that act by targeting HMGB1 are also discussed.

HMGB1 A box is one of the DNA-binding motifs of HMGB1. Originally, A box was described as participating in maintaining nucleosome structure and regulation of gene transcription [45]. We made several deletion mutants of HMGB1 and found that A box is a specific HMGB1 antagonist [21]. In vitro studies showed that A box competitively inhibits 125I-HMGB1 surface binding on macrophages and attenuates HMGB1-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine release in macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells [21]. Since this was first described in 2004, many articles have shown that treatment with HMGB1 antagonist A box inhibits HMGB1 activity and is beneficial in inflammatory disease models as listed below and in Table 1. Other pharmacological agents inhibit HMGB1 activities, as summarized below.

5.1. Endotoxemia

LPS administration is a well established shock model used to study cytokine responses in animals and humans [16,23]. In this model, serum cytokine levels such as TNF and IL-1 rise rapidly (within 2 h) after administration of LPS [23]. The kinetics of HMGB1 release is delayed compared to other early cytokines. This delayed HMGB1 response is different from TNF and distinguishes HMGB1 from other early-acting pro-inflammatory cytokines [16,46]. Serum HMGB1 levels remained unchanged during the first 8 h after injection of an LD50 dose of LPS in mice, increased significantly after 16 h and stayed at elevated plateau levels for at least 36 h [6]. Passive immunization with polyclonal anti-HMGB1 antibodies significantly protects against lethal endotoxemia in mice, even when treatment was delayed 2 h after LPS exposure [6,47]. The effects of anti-HMGB1 antibodies were dose-dependent and were effective even after the peak of circulating TNF was resolved [6]. Similar protective effects were observed with treatment of HMGB1 A box in endotoxemia model in mice [21].

One of the modes for active HMGB1 release is to migrate from nuclei to cytoplasm and then released into extracellular milieu [16,48,49]. A variety of pharmacological agents that inhibit the nuclear release of HMGB1 from macrophages have been used in the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Reduced nuclear export of HMGB1 release using vagus nerve stimulation through alpha-7 nicotinic improved survival and ameliorated end organ dysfunction in endotoxemia in mice [50–52].

Thrombomodulin is an endothelial anticoagulant cofactor that promotes thrombin-mediated formation of activated protein C. Thrombomodulin binds to HMGB1 via N terminal lectin domain of thrombomodulin [47]. Administration of recombinant soluble thrombomodulin neutralizes HMGB1 activity and improves survival in endotoxemia [47,53].

5.2. Sepsis induced by cecal perforation

Sepsis is a syndrome mediated by the systemic inflammatory responses to infection. Severe sepsis is sepsis with evidence of organ dysfunction, such as hypoxemia, oliguria, lactic acidosis, or altered cerebral function [54]. Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) is a standard model of murine sepsis in which the cecum is ligated and punctured to induce peritonitis and sepsis. Serum HMGB1 levels are elevated in this model of sepsis in a delayed pattern [21]. Serum HMGB1 levels are also significantly increased in sepsis patients, HMGB1 levels are higher in patients who succumbed to the disease than in survivors [6]. Sustained elevated serum HMGB1 levels are observed in patients with community-acquired pneumonia, the most common cause of severe sepsis; and higher levels of circulating HMGB1 are associated with mortality [42].

The protection conferred by anti-HMGB1 antibodies in endotoxemia is also observed in CLP sepsis [21,55]. Delayed treatment with either anti-HMGB1 antibodies or A box dose-dependently rescued mice from sepsis, and treatment was effective even when the first dose was given at 24 h after cecal ligation and puncture [21]. Recently developed anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibodies also confirmed these findings [17]. This effective treatment by delayed administration of HMGB1 antibodies or antagonist A box in sepsis demonstrates a wider window of opportunities as composed to early pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Blockade of RAGE–HMGB1 signaling by treatment with monoclonal anti-RAGE antibodies increases survival in septic rats [56]. Importantly, anti-TNF is ineffective in this model, indicating that HMGB1, not TNF is a necessary mediator of lethal sepsis.

Green tea extract, Chinese medicinal herbal Danshen, vagus nerve stimulation, cisplatin (an anti-tumor drug that induces DNA lesions) and ethyl pyruvate (a non-toxic food additive and an experimental anti-inflammatory agent) all inhibit HMGB1 release [51,52,57–63].

HMGB1 binds LPS in a dose-dependent manner as revealed by surface plasmon resonance (BiaCore) and this binding enhances LPS-mediated TNF production in human monocytes [64]. Polymyxin B, which binds LPS, also binds and removes HMGB1 from circulation. Hemoperfusion treatment with polymyxin B-immobilized filter column effectively removes HMGB1 from circulation in piglets subjected to cecal perforation and reduces serum HMGB1 levels in patients with septic shock [65,66].

5.3. Gastro-intestinal disorders

HMGB1 impairs intestinal barrier function by increasing both ileal mucosa permeability and bacterial translocation to mesenteric lymph nodes [67]. A fundamental mechanism of HMGB1-mediated toxicity and lethality in vivo is attributable to epithelial dysfunction and leakage [67,68]. In inflammatory bowel disease induced by dextran sulfate sodium salt, treatment with polyclonal anti-HMGB1 antibodies reduced inflammation and reduces tumor incidence in colitis-associated cancer [69]. Anti-HMGB1 antibodies also reversed LPS-induced gut barrier dysfunction (increased permeability and bacterial translocation) in rats [70]. Blockade of RAGE–HMGB1 signaling by treatment with monoclonal anti-RAGE antibodies ameliorates intestinal barrier function after hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation [71].

5.4. Pancreatitis

Serum HMGB1 levels are significantly elevated in patients with acute pancreatitis, and the levels correlate with severity. Similar findings have been observed in animal models of pancreatitis [72,73]. Treatment with anti-HMGB1 antibodies significantly reduced the incidence of multiple organ failure, and increased survival [74]. In severe acute pancreatitis, induced by 20% L-arginine injection, A box treatment lowered serum HMGB1 levels, had protective effects against organ injury, and improved survival [75]. Ethyl pyruvate, by reducing nuclear HMGB1 release, also showed protective effects against organ damage in severe acute pancreatitis in rodents [76–78].

5.5. Respiratory disorders

Elevated HMGB1 levels are observed in plasma and lung epithelial lining fluid of patients with acute lung injury and in mice instilled with LPS [79,80]. Addition of HMGB1 intra-tracheally in mice causes acute lung injury as manifested by neutrophil accumulation, lung edema and increased pulmonary cytokine levels including TNF, IL-1β and MIP-2 [79]. Blockade of HMGB1 by polyclonal anti-HMGB1 antibodies ameliorated LPS-induced acute lung injury and inflammation, reduced ventilator-induced lung injury, prevented hemorrhage-induced pulmonary levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and accumulation of neutrophils, and suppressed the development of pulmonary fibrosis in a mouse model of bleomycin-induced lung injury [79–83]. Treatment with A box conferred protection against lung injury in mice by reducing neutrophil filtration and decreasing the expression of chemokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines including HMGB1 [84]. Hemoperfusion treatment with polymyxin B-immobilized filter column effectively reduces serum HMGB1 levels in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome 9 characterized by inflammation and increased permeability edema in the lung [85]. Administration of recombinant soluble thrombomodulin neutralizes HMGB1 activity and ameliorates injury-induced lung thrombosis and inflammation [86].

5.6. Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, systemic, autoimmune and inflammatory disorder that affects the synovial lining of the joints. Inhibiting HMGB1 activity is therapeutic in arthritis, because administration of either anti-HMGB1 or A box in collagen type II-induced arthritis significantly attenuated the severity of disease [87,88]. HMGB1 levels in both serum and synovial fluid are significantly elevated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [88–91]. Recent studies suggest that tissue hypoxia and extracellular HMGB1 release play an important role in the pathogenesis of arthritis [88]. Immuno-staining of synovial tissues from collagen type II induced-induced arthritis showed that HMGB1 is abundantly expressed as a nuclear, cytoplasmic and extracellular component, compared with specimens from normal rats, in which HMGB1 is primarily confined to the nucleus [90]. Intra-articular administration of HMGB1 induces the onset of arthritis in mice suggesting the important role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of arthritis [87,92]. Blockade of RAGE–HMGB1 signaling by treatment with monoclonal anti-RAGE antibodies reduced the severity of arthritis [93]. Pharmacological agents that reduce nuclear export of HMGB1 release have been shown to attenuate arthritis and inflammation in collagen-induced arthritis, by using oxaliplatin (gold sodium thiomalate, a traditional therapy for arthritis) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and by stimulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor [94–96]. Also, administration of recombinant soluble thrombomodulin neutralizes HMGB1 activity and protected against arthritis [97].

5.7. Hemorrhagic shock

Hemorrhagic shock, in the absence of infection, induced an increase in serum HMGB1 levels within hours after aortic aneurysm rupture in a human patient [98]. In animal studies, HMGB1 is released early during the course of hemorrhagic shock, and HMGB1 plays a role in the pathogenesis of hemorrhagic shock-induced tissue damage [38,71,81,99]. Treatment with anti-HMGB1 antibodies improves survival and reduces hemorrhage-induced acute lung injury, gut barrier dysfunction [71,81,99]. Mechanistically, hemorrhagic shock-induced lung injury and NADPH oxidase activation in neutrophils are HMGB1-TLR4 mediated events [38,100].

5.8. Stroke

Ischemic injury in the central nervous system (stroke) is mediated by glutamate excitotoxicity-induced neuron death. In ischemic stroke, the necrotic core is surrounded by a zone of inflammation, in which delayed cell death aggravates the initial insult. HMGB1 has been shown as a mediator in both the initial and delayed injury processes [101]. Patients with stroke had elevated serum HMGB1 levels hours after the onset of symptoms [102]. Tissue ischemia in animal models causes HMGB1 release into the extracellular milieu [103–105]. Nuclear HMGB1 translocates into a cytoplasmic region of neurons within 1 h of cerebral artery occlusion and HMGB1 gets fully depleted during the excitotoxicity-induced acute process [106]. Within 2 days after reperfusion, HMGB1 is expressed in activated microglia cells, astrocytes, macrophages and endothelial cells in the penumbra [106]. Elevated extracellular HMGB1 levels stimulate transporter-mediated glutamate release and in turn mediate cytotoxicity [107,108]. HMGB1 release can activate astrocytes and microglia, which are the markers of brain inflammation. HMGB1 also activates macrophages/monocytes to release the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF and IL-6, and enhances pro-coagulant activity which contributes to tissue damage by clotting the micro-vasculature and worsening ischemia in the penumbra region [108,109]. Intra-cerebroventricular injection of recombinant HMGB1 worsens the severity of tissue damage induced by infarction. Administration of both polyclonal and monoclonal anti-HMGB1 antibodies to rats subjected to middle cerebra artery occlusion had significant protective effects and reduced cell death [110,111]. Administration of A box ameliorated brain damage in a similar pattern as treatment with anti-HMGB1 antibodies [111].

5.9. Ischemia–reperfusion injury

Ischemia–reperfusion induces cytokine-driven inflammatory responses and tissue injury. Treatment with polyclonal anti-HMGB1 antibodies attenuates hepatic injury during liver ischemia–reperfusion [10]. HMGB1 acts as an early mediator of inflammation and organ damage in ischemia–reperfusion injury of the heart [15]. Treatment with A box significantly reduced infarct size and markers of tissue damage whereas administration of HMGB1 worsens the injury [15].

5.10. Transplantation

HMGB1 levels are elevated and reflect the extent of hepatocellular injury in human liver transplantation [112]. In animal models, HMGB1 plays a pivotal role in acute allograft rejection in murine cardiac transplantation [113]. Therapeutic administration of A box significantly enhances cardiac allograft survival and is associated with reduced allograft expression of TNF, IFN-gamma and HMGB1 [113].

6. Conclusion: targeting HMGB1 in inflammatory diseases

The original suggestion to target the inflammatory activity of HMGB1 to confer protection against tissue injury has been validated in dozens of preclinical studies. As both a secreted effector molecule produced during PAMP-activation of innate immunity, and an inflammatory mediator produced during sterile injury as a DAMP-signal, HMGB1 occupies a crucial signaling role at the intersection of these pathways. Ongoing work into the nature of HMGB1-receptor signal transduction, and its interaction with other mediators associated with activation of cytokine networks, will continue to expand biological understanding. The discovery of the significant protection afforded by anti-HMGB1 antibodies in diverse preclinical studies of innate immunity provides a new paradigm for strategic development of experimental therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

This work is partially supported by grants from NIH NCRR M01 RR018535, and NIH NIGMS (to KJT).

References

- 1.Nathan CF. Secretory products of macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:319–326. doi: 10.1172/JCI112815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tracey KJ. Physiology and immunology of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:289–296. doi: 10.1172/JCI30555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas L. The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher. Penguin books; New York, NY USA: 1978. p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 family. In: Thomson AW, Lotze MT, editors. Cytokine Handbook. 4. Academic Press; 2003. pp. 643–662. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kishmoto T. Interleukin 6. In: Thomson AW, Lotze MT, editors. Cytokine Handbook. 4. Vol. 1. Academic Press; 2003. pp. 281–295. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue KR, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina PE, Abumrad NN, Sama A, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 1999;285:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson U, Wang H, Palmblad K, Aveberger AC, Bloom O, Harris HE, Janson A, Kokkola R, Zhang M, Yang H, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 stimulates proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in human monocytes. J Exp Med. 2000;192:565–570. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Ward MF, Sama AE. Novel HMGB1-inhibiting therapeutic agents for experimental sepsis. Shock. 2009;32:348–357. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181a551bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeyabalan G, Tsung A, Billiar TR. Linking proximal and downstream signalling events in hepatic ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34(Pt 5):957–959. doi: 10.1042/BST0340957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsung A, Sahai R, Tanaka H, Nakao A, Fink MP, Lotze MT, Yang H, Li J, Tracey KJ, Geller DA, Billiar TR. The nuclear factor HMGB1 mediates hepatic injury after murine liver ischemia–reperfusion. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1135–1143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lotze MT, Zeh HJ, Rubartelli A, Sparvero LJ, Amoscato AA, Washburn NR, Devera ME, Liang X, Tör M, Billiar TR. The grateful dead: damage-associated molecular pattern molecules and reduction/oxidation regulate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2007;220:60–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Vishnubhakat JM, Bloom O, Zhang M, Ombrellino M, Sama A, Tracey KJ. Proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1) stimulate release of high mobility group protein-1 by pituicytes. Surgery. 1999;126:389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sparatore B, Passalacqua M, Patrone M, Melloni E, Pontremoli S. Extracellular high-mobility group 1 protein is essential for murine erythroleukaemia cell differentiation. Biochem J. 1996;320(Pt. 1):253–256. doi: 10.1042/bj3200253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrassy M, Volz HC, Igwe JC, Funke B, Eichberger SN, Kaya Z, Buss S, Autschbach F, Pleger ST, Lukic IK, Bea F, Hardt SE, Humpert PM, Bianchi ME, Mairbäurl H, Nawroth PP, Remppis A, Katus HA, Bierhaus A. High-mobility group box-1 in ischemia–reperfusion injury of the heart. Circulation. 2008;117:3216–3226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang H, Wang H, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ. The cytokine activity of HMGB1. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1–6. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1104648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin S, Wang H, Yuan R, Li H, Ochani M, Ochani K, Rosas-Ballina M, Czura CJ, Huston JM, Miller E, Lin X, Sherry B, Kumar A, LaRosa G, Newman W, Tracey KJ, Yang H. Role of HMGB1 in apoptosis-mediated sepsis lethality. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1637–1642. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang W, Pisetsky DS. Mechanisms of disease: the role of high-mobility group protein 1 in the pathogenesis of inflammatory arthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:52–58. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell CW, Jiang W, Reich CF, Pisetsky DS. The extracellular release of HMGB1 during apoptotic cell death. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C1318–C1325. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00616.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kazama H, Ricci JE, Herndon JM, Hoppe G, Green DR, Ferguson TA. Induction of immunological tolerance by apoptotic cells requires caspase-dependent oxidation of high-mobility group box-1 protein. Immunity. 2008;29:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang H, Ochani M, Li JH, Qiang X, Tanovic M, Harris HE, Susarla SM, Ulloa L, Wang H, DiRaimo R, Czura CJ, Wang HC, Roth J, Warren HS, Fink MP, Fenton MJ, Andersson U, Tracey KJ. Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous HMGB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:296–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434651100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Kokkola R, Tabibzadeh S, Yang R, Ochani M, Qiang X, Harris HE, Czura CJ, Wang H, Ulloa L, Wang HC, Warren HS, Moldawer LL, Fink MP, Andersson U, Tracey KJ, Yang H. Structural basis for the proinflammatory cytokine activity of high mobility group box 1. Mol Med. 2003;9:37–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang HC, Yang H, Czura CJ, Sama AE, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 as a late mediator of lethal systemic inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1768–1773. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2106117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stern D, Yan SD, Yan SF, Schmidt AM. Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts: a multiligand receptor magnifying cell stress in diverse pathologic settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taguchi AD, Blood C, del Toro G, Canet A, Lee DC, Qu W, Tanji N, Lu Y, Lalla E, Fu C, Hofmann MA, Kislinger T, Ingram M, Lu A, Tanaka H, Hori O, Ogawa S, Stern DM, Schmidt AM. Blockade of RAGE-amphoterin signalling suppresses tumour growth and metastases. Nature. 2000;405:354–360. doi: 10.1038/35012626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Susa Y, Masuda Y, Imaizumi H, Namiki A. Neutralization of receptor for advanced glycation end-products and high mobility group box-1 attenuates septic diaphragm dysfunction in rats with peritonitis. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2619–2624. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a930f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsung A, Klune JR, Zhang X, Jeyabalan G, Cao Z, Peng X, Stolz DB, Geller DA, Rosengart MR, Billiar TR. HMGB1 release induced by liver ischemia involves Toll-like receptor 4 dependent reactive oxygen species production and calcium-mediated signaling. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2913–2923. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krüger B, Krick S, Dhillon N, Lerner SM, Ames S, Bromberg JS, Lin M, Walsh L, Vella J, Fischereder M, Krämer BK, Colvin RB, Heeger PS, Murphy BT, Schröppel B. Donor Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to ischemia and reperfusion injury following human kidney transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:3390–33495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810169106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaczorowski DJ, Nakao A, Vallabhaneni R, Mollen KP, Sugimoto R, Kohmoto J, Zuckerbraun BS, McCurry KR, Billiar TR. Mechanisms of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated inflammation after cold ischemia/reperfusion in the heart. Transplantation. 2009;87:1455–1463. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a36e5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaczorowski DJ, Tsung A, Billiar TR. Innate immune mechanisms in ischemia/reperfusion. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2009;1:91–98. doi: 10.2741/E10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hori O, Brett J, Slattery T, Cao R, Zhang J, Chen JX, Nagashima M, Lundh ER, Vijay S, Nitecki D, Morser J, Stern D, Schmidt AM. The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a cellular binding site for amphoterin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25752–25761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Degryse B, Bonaldi T, Scaffidi P, Muller S, Resnati M, Sanvito F, Arrigoni G, Bianchi ME. The high mobility group (HMG) boxes of the nuclear protein HMG1 induce chemotaxis and cytoskeleton reorganization in rat smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:1197–1206. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.6.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Zoelen MA, Yang H, Florquin S, Meijers JC, Akira S, Arnold B, Nawroth PP, Bierhaus A, Tracey KJ, van der Poll T. Role of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4, and the receptor for advanced glycation end products in high-mobility group box 1-induced inflammation in vivo. Shock. 2009;31:280–284. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318186262d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huttunen HJ, Fages C, Kuja-Panula J, Ridley AJ, Rauvala H. Receptor for advanced glycation end products-binding COOH-terminal motif of amphoterin inhibits invasive migration and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2003;62:4805–4811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiuza C, Bustin M, Talwar S, Tropea M, Gerstenberger E, Shelhamer JH, Suffredini AF. Inflammatory promoting activity of HMGB1 on human microvascular endothelial cells. Blood. 2003;101:2652–2660. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, Obeid M, Ortiz C, Criollo A, Mignot G, Maiuri MC, Ullrich E, Saulnier P, Yang H, Amigorena S, Ryffel B, Barrat FJ, Saftig P, Levi F, Lidereau R, Nogues C, Mira JP, Chompret A, Joulin V, Clavel-Chapelon F, Bourhis J, André F, Delaloge S, Tursz T, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med. 2007;13:1050–1059. doi: 10.1038/nm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsung A, Zheng N, Jeyabalan G, Izuishi KK, Jr, Geller DA, Lotze MT, Lu L, Billiar TR. Increasing numbers of hepatic dendritic cells promote HMGB1-mediated ischemia–reperfusion injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:119–128. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0706468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan J, Li Y, Levy RM, Fan JJ, Hackam DJ, Vodovotz Y, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Billiar TR, Wilson MA. Hemorrhagic shock induces NAD(P)H oxidase activation in neutrophils: role of HMGB1-TLR4 signaling. J Immunol. 2007;178:6573–6580. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu M, Wang H, Ding A, Golenbock DT, Latz E, Czura CJ, Fenton MJ, Tracey KJ, Yang H. HMGB1 signals through Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and TLR2. Shock. 2006;26:174–179. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000225404.51320.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park JS, Svetkauskaite D, He H, Kim J, Strassheim D, Ishizaka A, Abraham E. Involvement of TLR2 and TLR4 in cellular activation by high mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7370–7376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park JS, Gamboni-Robertson F, He Q, Svetkauskaite D, Kim J, Strassheim D, Sohn J, Yamada S, Maruyama I, Banerjee A, Ishizaka A, Abraham E. High mobility group box 1 protein interacts with multiple Toll-like receptors. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C917–C924. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00401.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angus DC, Yang L, Kong L, Kellum JA, Delude RL, Tracey KJ, Weissfeld L. GenIMS investigators circulating high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) concentrations are elevated in both uncomplicated pneumonia and pneumonia with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1061–1067. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259534.68873.2A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang H, Wang H, Ochani M, Ochani K, Rosas-Ballina M, Parrish WR, Tracey KJ. Endogenous mammalian HMGB1, devoid of any contaminants introduced by purification of recombinant proteins, mediates anorexia, weight loss, and increased TNF levels. 31st Annual Conference on Shock; Cologne, Germany, Shock. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sha Y, Zmijewski J, Xu Z, Abraham E. HMGB1 develops enhanced proin-flammatory activity by binding to cytokines. J Immunol. 2008;180:2531–2537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Landsman D, Bustin MA. Signature for the HMG-1 box DNA-binding proteins. BioEssays. 1993;15:539–546. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang HC, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ. Tumor necrosis factor. In: Thomson AW, Lotze MT, editors. Cytokine Handbook. 4. Academic Press; 2003. pp. 837–883. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abeyama K, Stern DM, Ito Y, Kawahara K, Yoshimoto Y, Tanaka M, Uchimura T, Ida N, Yamazaki Y, Yamada S, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H, Iino S, Taniguchi N, Maruyama I. The N-terminal domain of thrombomodulin sequesters high-mobility group-B1 protein, a novel anti-inflammatory mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1267–1274. doi: 10.1172/JCI22782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonaldi T, Talamo F, Scaffidi P, Ferrera D, Porto A, Bachi A, Rubartelli A, Agresti A, Bianchi ME. Monocytic cells hyperacetylate chromatin protein HMGB1 to redirect it towards secretion. EMBO J. 2003;22:5551–5560. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gardella S, Andrei C, Ferrera D, Lotti LV, Torrisi MR, Bianchi ME, Rubartelli A. The nuclear protein HMGB1 is secreted by monocytes via a non-classical, vesicle-mediated secretory pathway. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:995–1001. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tracey KJ. Reflex control of immunity. Nat Rev, Immunol. 2009;9:418–428. doi: 10.1038/nri2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Liao H, Ochani M, Justiniani M, Lin X, Yang L, Al-Abed Y, Wang H, Metz C, Miller EJ, Tracey KJ, Ulloa L. Cholinergic agonists inhibit HMGB1 release and improve survival in experimental sepsis. Nat Med. 2004;10:1216–1221. doi: 10.1038/nm1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pavlov VA, Ochani M, Yang L, Puerta MG, Ochani K, Lin X, Levi J, Parrish WR, Rosas-Ballina M, Czura CJ, Larosa GJ, Miller EJ, Tracey KJ, Al-Abed Y. Selective alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist GTS-21 improves survival in murine endotoxemia and severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1139–1144. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259381.56526.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nagato M, Okamoto K, Abe Y, Higure A, Yamaguchi K. Recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin decreases the plasma high-mobility group box-1 protein levels, whereas improving the acute liver injury and survival rates in experimental endotoxemia. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2181–2186. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a55184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matot I, Sprung CL. Definition of sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:S3–S9. doi: 10.1007/pl00003795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suda K, Kitagawa Y, Ozawa S, Saikawa Y, Ueda M, Ebina M, Yamada S, Hashimoto S, Fukata S, Abraham E, Maruyama I, Kitajima M, Ishizaka A. Anti-high-mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 antibodies improve survival of rats with sepsis. World J Surg. 2006;30:1755–1762. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0369-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lutterloh EC, Opal SM, Pittman DD, Keith JC, Jr, Tan XY, Clancy BM, Palmer H, Milarski K, Sun Y, Palardy JE, Parejo NA, Kessimian N. Inhibition of the RAGE products increases survival in experimental models of severe sepsis and systemic infection. Crit Care. 2007;11:R122. doi: 10.1186/cc6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li W, Ashok M, Li J, Yang H, Sama AE, Wang H. A major ingredient of green tea rescues mice from lethal sepsis partly by inhibiting HMGB1. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li W, Li J, Ashok M, Wu R, Chen D, Yang L, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Wang P, Sama AE, Wang H. A cardiovascular drug rescues mice from lethal sepsis by selectively attenuating a late-acting proinflammatory mediator, high mobility group box 1. J Immunol. 2007;178:3856–3864. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huston JM, Puerta MG, Ochani M, Ochani K, Yuan R, Rosas-Ballina M, Ashok M, Goldstein RS, Chavan S, Pavlov VA, Metz CN, Yang H, Czura CJ, Wang H, Tracey KJ. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation reduces serum high mobility group box 1 levels and improves survival in murine sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2762–2768. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000288102.15975.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pan P, Cardinal J, Dhupar R, Rosengart MR, Lotze MT, Geller DA, Billiar TR, Tsung A. Low-dose cisplatin administration in murine cecal ligation and puncture prevents the systemic release of HMGB1 and attenuates lethality. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:625–632. doi: 10.1189/JLB.1108713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ulloa L, Ochani M, Yang H, Tanovic M, Halperin D, Yang R, Czura CJ, Fink MP, Tracey KJ. Ethyl pyruvate prevents lethality in mice with established lethal sepsis and systemic inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12351–12356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192222999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miyaji T, Hu X, Yuen PS, Muramatsu Y, Iyer S, Hewitt SM, Star RA. Ethyl pyruvate decreases sepsis-induced acute renal failure and multiple organ damage in aged mice. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1620–1631. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leelahavanichkul A, Yasuda H, Doi K, Hu X, Zhou H, Yuen PST, Star RA. Methyl-2-acetamidoacrylate, an ethyl pyruvate analog, decreases sepsis-induced acute kidney injury in mice. Am J Physiol, Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1825–F1835. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90442.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Youn JH, Oh YJ, Kim ES, Choi JE, Shin JS. High mobility group box 1 protein binding to lipopolysaccharide facilitates transfer of lipopolysaccharide to CD14 and enhances lipopolysaccharide-mediated TNF-alpha production in human monocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:5067–5074. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.5067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sakamoto Y, Mashiko K, Matsumoto H, Hara Y, Kutsukata N, Yamamoto Y. Relationship between effect of polymyxin B-immobilized fiber and high-mobility group box-1 protein in septic shock patients. ASAIO J. 2007;53:324–328. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3180340301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hussein MH, Kato T, Sugiura T, Daoud GA, Suzuki S, Fukuda S, Sobajima H, Kato I, Togari H. Effect of hemoperfusion using polymyxin B-immobilized fiber on IL-6, HMGB-1, and IFN gamma in a neonatal sepsis model. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:309–314. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000169995.25333.F7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sappington PL, Yang R, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Delude RL, Fink MP. HMGB1 B Box Increases the permeability of Caco-2 enterocytic monolayers and impairs intestinal barrier function in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:790–802. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu S, Stolz DB, Sappington PL, Macias CA, Killeen ME, Tenhunen JJ, Delude RL, Fink MP. HMGB1 is secreted by immunostimulated enterocytes and contributes to cytomix-induced hyperpermeability of Caco-2 monolayers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C990–C999. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00308.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maeda S, Hikiba Y, Shibata W, Ohmae T, Yanai A, Ogura K, Yamada S, Omata M. Essential roles of high-mobility group box 1 in the development of murine colitis and colitis-associated cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang R, Miki K, Oksala N, Nakao A, Lindgren L, Killeen ME, Mennander A, Fink MP, Tenhunen J. Bile high-mobility group box 1 contributes to gut barrier dysfunction in experimental endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R362–R369. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00184.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Raman KG, Sappington PL, Yang R, Levy RM, Prince JM, Liu S, Watkins SK, Schmidt AM, Billiar TR, Fink MP. The role of RAGE in the pathogenesis of intestinal barrier dysfunction after hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol: Gasterointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G556–G565. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00055.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yasuda T, Ueda T, Shinzeki M, Sawa H, Nakajima T, Takeyama Y, Kuroda Y. Increase of high-mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 in blood and injured organs in experimental severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2007;34:487–488. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31804154e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kocsis AK, Szabolcs A, Hofner P, Takács T, Farkas G, Boda K, Mándi Y. Plasma concentrations of high-mobility group box protein 1, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products and circulating DNA in patients with acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2009;9:383–391. doi: 10.1159/000181172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sawa H, Ueda T, Takeyama Y, Yasuda T, Shinzeki M, Nakajima T, Kuroda Y. Blockade of high mobility group box-1 protein attenuates experimental severe acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;2:7666–7670. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i47.7666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yuan H, Jin X, Sun J, Li F, Feng Q, Zhang C, Cao Y, Wang Y. Protective effect of HMGB1 A box on organ injury of acute pancreatitis in mice. Pancreas. 2009;38:143–148. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31818166b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang R, Shaufl AL, Killeen ME, Fink MP. Ethyl pyruvate ameliorates liver injury secondary to severe acute pancreatitis. J Surg Res. 2009;53:302–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang ZY, Ling Y, Yin T, Tao J, Xiong JX, Wu HS, Wang CY. Delayed ethyl pyruvate therapy attenuates experimental severe acute pancreatitis via reduced serum high mobility group box 1 levels in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4546–4550. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cheng BQ, Liu CT, Li WJ, Fan W, Zhong N, Zhang Y, Jia XQ, Zhang SZ. Ethyl pyruvate improves survival and ameliorates distant organ injury in rats with severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2007;35:256–261. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318064678a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abraham E, Arcaroli J, Carmody A, Wang H, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 as a mediator of acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2000;165:2950–2954. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ueno HM, Hashimoto T, Amaya S, Kitamura F, Tanaka Y, Kobayashi M, Maruyama A, Yamada I, Hasegawa S, Soejima N, Koh J, Ishizaka H. Contributions of high mobility group box protein in experimental and clinical acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1310–1316. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-188OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim JY, Park JS, Strassheim D, Douglas I, Diaz del Valle F, Asehnoune K, Mitra S, Kwak SH, Yamada S, Maruyama I, Ishizaka A, Abraham E. HMGB1 contributes to the development of acute lung injury after hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L958–L965. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00359.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ogawa EN, Ishizaka A, Tasaka S, Koh H, Ueno H, Amaya F, Ebina M, Yamada S, Funakoshi Y, Soejima J, Moriyama K, Kotani T, Hashimoto S, Morisaki H, Abraham E, Takeda J. Contribution of high-mobility group box-1 to the development of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:400–407. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-699OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hamada N, Maeyama T, Kawaguchi T, Yoshimi M, Fukumoto J, Yamada M, Yamada S, Kuwano K, Nakanishi Y. The role of high mobility group box1 in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:440–447. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0330OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gong Q, Xu JF, Yin H, Liu SF, Duan LH, Bian ZL. Protective effect of antagonist of high-mobility group box 1 on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Scand J Immunol. 2009;69:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nakamura T, Fujiwara N, Sato E, Kawagoe Y, Ueda Y, Yamada S, Koide H. Effect of polymyxin B-immobilized fiber hemoperfusion on serum high mobility group box-1 protein levels and oxidative stress in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. ASAIO J. 2009;55:395–399. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3181a5290f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ding BS, Hong N, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Gottstein C, Albelda SM, Cines DB, Fisher AB, Muzykantov VR. Anchoring fusion thrombomodulin to the endothelial lumen protects against injury-induced lung thrombosis and inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:247–256. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1433OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kokkola R, Li J, Sundberg E, Aveberger AC, Palmblad K, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Andersson U, Harris HE. Successful treatment of collagen-induced arthritis in mice and rats by targeting extracellular high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2052–2058. doi: 10.1002/art.11161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hamada T, Torikai M, Kuwazuru A, Tanaka M, Horai N, Fukuda T, Yamada S, Nagayama S, Hashiguchi K, Sunahara N, Fukuzaki K, Nagata R, Komiya S, Maruyama I, Fukuda T, Abeyama K. Extracellular high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 is a coupling factor for hypoxia and inflammation in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2675–2685. doi: 10.1002/art.23729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Taniguchi N, Kawahara K, Yone K, Hashiguchi T, Yamakuchi M, Goto M, Inoue K, Yamada S, Ijiri K, Matsunaga S, Nakajima T, Komiya S, Maruyama I. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 plays a role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis as a novel cytokine. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:971–981. doi: 10.1002/art.10859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kokkola R, Sundberg E, Ulfgren AK, Palmblad K, Li J, Wang H, Ulloa L, Yang H, Yan XJ, Furie R, Chiorazzi N, Tracey KJ, Andersson U, Harris HE. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 (HMGB1)—a novel pro-inflammatory mediator in synovitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2598–2603. doi: 10.1002/art.10540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Goldstein RS, Bruchfeld A, Yang L, Qureshi AR, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Patel NB, Huston BJ, Chavan S, Rosas-Ballina M, Gregersen PK, Czura CJ, Sloan RP, Sama AE, Tracey KJ. Cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway activity and high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) serum levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Med. 2007;13:210–215. doi: 10.2119/2006-00108.Goldstein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pullerits R, Jonsson IM, Verdrengh M, Bokarewa M, Andersson U, Erlandsson-Harris H, Tarkowski A. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1, a DNA binding cytokine, induces arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1693–1700. doi: 10.1002/art.11028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hofmann MA, Drury S, Hudson BI, Gleason MR, Qu W, Lu Y, Lalla E, Chitnis S, Monteiro J, Stickland MH, Bucciarelli LG, Moser B, Moxley G, Itescu S, Grant PJ, Gregersen PK, Stern DM, Schmidt AM. RAGE and arthritis: the G82S polymorphism amplifies the inflammatory response. Genes Immun. 2002;3:123–135. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zetterstrom CK, Jiang W, Wahamaa H, Ostberg T, Aveberger AC, Schierbeck H, Lotze MT, Andersson U, Pisetsky DS, Harris HE. Pivotal advance: inhibition of HMGB1 nuclear translocation as a mechanism for the anti-rheumatic effects of gold sodium thiomalate. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:31–38. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0507323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Abad C, Martinez C, Leceta J, Gomariz RP, Delgado M. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibits collagen-induced arthritis: an experimental immunomodulatory therapy. J Immunol. 2001;167:3182–3189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.van Maanen MA, Lebre MC, van der Poll T, LaRosa GJ, Elbaum D, Vervoordeldonk MJ, Tak PP. Stimulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors attenuates collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:114–122. doi: 10.1002/art.24177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Van de WM, Wouwer VM, Plaisance S, De Vriese A, Waelkens E, Collen D, Persson J, Daha MR, Conway EM. The lectin-like domain of thrombomodulin interferes with complement activation and protects against arthritis. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1813–1824. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ombrellino M, Wang H, Ajemian MS, Talhouk A, Scher LA, Friedman SG, Tracey KJ. Increased serum concentrations of high-mobility-group protein 1 in hemorrhagic shock. Lancet. 2000;354:1446–1447. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02658-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yang R, Harada T, Mollen KP, Prince JM, Levy RM, Englert JA, Puerta MG, Yang L, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Harbrecht BG, Billiar TR, Fink MP. Anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody ameliorates gut barrier dysfunction and improves survival after hemorrhagic shock. Mol Med. 2006;12:105–114. doi: 10.2119/2006-00010.Yang. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barsness KA, Arcaroli J, Harken AH, Abraham E, Banerjee A, Reznikov L, McIntyre RC. Hemorrhage-induced acute lung injury is TLR-4 dependent. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R592–R599. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00412.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang Q, Wang J, Li J, Zhou Y, Zhong Q, Lu F, Xiang J. High-mobility group protein box-1 and its relevance to cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009:1–12. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Goldstein RS, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Yang L, Rosas-Ballina M, Huston JM, Czura CJ, Lee DC, Ward MF, Bruchfeld AN, Wang H, Lesser ML, Church AL, Litroff AH, Sama AE, Tracey KJ. Elevated high-mobility group box 1 levels in patients with cerebral and myocardial ischemia. Shock. 2006;25:571–574. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000209540.99176.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kim JB, Choi SJ, Yu YM, Nam K, Piao CS, Kim SW, Lee MH, Han PL, Park JS, Lee JK. HMGB1, a novel cytokine-like mediator linking acute neuronal death and delayed neuro-inflammation in the postischemic brain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6413–6421. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3815-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Faraco G, Fossati S, Bianchi ME, Patrone M, Pedrazzi M, Sparatore B, Moroni F, Chiarugi A. High mobility group box 1 protein is released by neural cells upon different stresses and worsens ischemic neurodegeneration in vitro and in vivo. J Neurochem. 2007;103:590–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Qiu J, Nishimura M, Wang Y, Sims JR, Qiu S, Savitz SI, Salomone S, Moskowitz MA. Early release of HMGB-1 from neurons after the onset of brain ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:927–938. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim J, Lim C, Yu Y, Lee J. Induction and subcellular localization of high-mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) in the postischemic rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1125–1131. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bonanno G, Raiteri L, Milanese M, Zappettini S, Melloni E, Pedrazzi M, Passalacqua M, Tacchetti C, Usai C, Sparatore B. The high-mobility group box 1 cytokine induces transporter-mediated release of glutamate from glial subcellular particles (gliosomes) prepared from in situ-matured astrocytes. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;82:73–93. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)82004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pedrazzi M, Raiteri L, Bonanno G, Patrone M, Ledda S, Passalacqua M, Milanese M, Melloni E, Raiteri M, Pontremoli S, Sparatore B. Stimulation of excitatory amino acid release from adult mouse brain glia subcellular particles by high mobility group box 1 protein. J Neurochem. 2006;99:827–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ito T, Kawahara K, Hashiguchi T, Maruyama M. High-mobility group box 1 protein promotes development of microvascular thrombosis in rats. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liu K, Mori S, Takahashi HK, Tomono Y, Wake H, Kanke T, Sato Y, Hiraga N, Adachi N, Yoshino T, Nishibori M. Anti-high mobility group box 1 monoclonal antibody ameliorates brain infarction induced by transient ischemia in rats. FASEB J. 2007;21:3904–3916. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8770com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Muhammad S, Barakat W, Stoyanov S, Murikinati S, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Bendszus M, Rossetti G, Nawroth PP, Bierhaus A, Schwaninger M. The HMGB1 receptor RAGE mediates ischemic brain damage. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12023–12120. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2435-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ilmakunnas, Tukiainen EM, Rouhiainen A, Rauvala H, Arola J, Nordin A, Mäkisalo H, Hockerstedt K, Isoniemi H. High mobility group box 1 protein as a marker of hepatocellular injury in human liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2008;14:1517–1525. doi: 10.1002/lt.21573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Huang Y, Yin H, Han J, Huang B, Xu J, Zheng F, Tan Z, Fang M, Rui L, Chen D, Wang S, Zheng X, Wang CY, Gong F. Extracellular HMGB1 functions as an innate immune-mediator implicated in murine cardiac allograft acute rejection. Am J Trans. 2007;7:799–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tsoyi K, Lee TY, Lee YS, Kim HJ, Seo HG, Lee JH, Chang KC. Heme-oxygenase-1 induction and carbon monoxide-releasing molecule inhibit lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced high-mobility group box 1 release in vitro and improve survival of mice in LPS-and cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis model in vivo. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:173–182. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.055137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tang Y, Ly B, Wang H, Zuo X, Xiao X. PACAP inhibit the release and cytokine activity of HMGB1 and improve the survival during lethal endotoxemia. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:1646–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]