Effects of Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase Subtypes, Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases, and Porin Mutations on the In Vitro Activity of Ceftazidime-Avibactam against Carbapenem-Resistant K. pneumoniae (original) (raw)

Abstract

Avibactam is a novel β-lactamase inhibitor with affinity for Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs). In combination with ceftazidime, the agent demonstrates activity against KPC-producing K. pneumoniae (KPC-Kp). KPC-Kp strains are genetically diverse and harbor multiple resistance determinants, including defects in outer membrane proteins and extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs). Mutations in porin gene ompK36 confer high-level carbapenem resistance to KPC-Kp strains. Whether specific mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance also influence the activity of ceftazidime-avibactam is unknown. We defined the effects of ceftazidime-avibactam against 72 KPC-Kp strains with diverse mechanisms of resistance, including various combinations of KPC subtypes and ESBL and ompK36 mutations. Ceftazidime MICs ranged from 64 to 4,096 μg/ml and were lowered by a median of 512-fold with the addition of avibactam. All strains exhibited ceftazidime-avibactam MICs at or below the CLSI breakpoint for ceftazidime (≤4 μg/ml; range, 0.25 to 4). However, the MICs were within two 2-fold dilutions of the CLSI breakpoint against 24% of the strains, and those strains would be classified as nonsusceptible to ceftazidime by EUCAST criteria (MIC > 1 μg/ml). Median ceftazidime-avibactam MICs were higher against KPC-3 than KPC-2 variants (P = 0.02). Among KPC-2-Kp strains, the presence of both ESBL and porin mutations was associated with higher drug MICs compared to those seen with either factor alone (P = 0.003 and P = 0.02, respectively). In conclusion, ceftazidime-avibactam displays activity against genetically diverse KPC-Kp strains. Strains with higher-level drug MICs provide a reason for caution. Judicious use of ceftazidime-avibactam alone or in combination with other agents will be important to prevent the emergence of resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Avibactam is a non-β-lactam, β-lactamase inhibitor with broad-spectrum activity against Ambler class A, class C, and some class D serine-based β-lactamases. Most notably, the agent inhibits class C Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs). The addition of avibactam to ceftazidime results in considerably lower ceftazidime MICs (1). As a result, ceftazidime-avibactam may prove to be a valuable addition to the limited antibiotic armamentarium against infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) (2, 3). At the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, sequence type 258 (ST258) international epidemic clone of KPC-producing K. pneumoniae (KPC-Kp) is the predominant CRE; however, outcomes among KPC-Kp-infected patients, and the constellation of resistant determinants among individual strains, are highly variable (2, 4). Carbapenem resistance is mediated through multiple mechanisms, including production of KPCs, defects in outer membrane proteins (OMPs), and expression of other extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) (2). Therefore, inhibition of β-lactamases may not provide a “one-size-fits-all” therapeutic option against CRE.

We have recently shown that specific mutations in the ompK36 porin gene confer high-level carbapenem resistance and attenuate responses to carbapenem-colistin therapy among KPC-Kp strains in vitro (5, 6) and during bloodstream infections (3). Such mutations are present in more than 50% of KPC-Kp strains at our center (2, 5). The impact of changes to outer membrane permeability on ceftazidime-avibactam susceptibility is unknown. We hypothesized that the specific resistance mechanisms manifested by KPC-Kp strains likely influence the activity of ceftazidime-avibactam. The objective of this study was to measure ceftazidime-avibactam activity against genetically diverse KPC-Kp strains harboring various combinations of ESBLs and porin mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical strains.

Seventy-two K. pneumoniae clinical strains from unique patients at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC; n = 68) and the University of Florida Health-Shands Hospital (n = 4) were selected from our biorepository for the study. Strains were all confirmed as KPC-Kp, for which we have established the β-lactamase profile and sequenced porin genes. To compare various subtypes, we included strains harboring KPC-2 and KPC-3, as well as those with and without porin mutations. All strains were stored at −80°C and subcultured twice on Mueller-Hinton agar prior to testing in the XDR Pathogen Laboratory at UPMC. PCR with and without DNA sequencing was used to detect resistant determinants and porin gene mutations as described previously (2, 6–8).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

MICs were determined for doripenem, ceftazidime, and ceftazidime-avibactam using the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) reference broth microdilution method with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (9). Ceftazidime over a range of concentrations was combined with avibactam at a fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml. Avibactam was supplied by AstraZeneca, while ceftazidime and doripenem were purchased from the UPMC pharmacy. Quality control (QC) was performed with Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853; all QC results were within the specified ranges (10).

Statistical analysis.

Graphical and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA). Comparisons between categorical or continuous variables were made by Fisher's exact and Mann-Whitney tests, respectively.

RESULTS

The doripenem MIC50 and MIC90 values against 72 KPC-Kp strains were 48 and 128 μg/ml, respectively. Eighty-six percent (62/72) and 14% (10/72) of the strains produced KPC-2 and KPC-3, respectively. All but two strains (both KPC-3 producers) were classified as ST258. Ninety-nine percent (71/72), 94% (68/72), and 8% (6/72) of the strains harbored SHV-, TEM-, and CTX-M-type beta-lactamases, respectively. ESBL enzymes were detected in 88% (63/72) of the strains and were more common among KPC-2-producing strains than KPC-3-producing strains (P = 0.02) (Table 1). No strains harbored IMP, NDM, VIM, AmpC, or OXA-48. A total of 97% (70/72) of the strains carried a mutant ompK35 porin gene (AA89 STOP), and 63% (45/72) had a mutant ompK36 gene. Sequence analysis revealed several ompK36 mutant genotypes, the most common of which were IS_5_ promoter insertions (n = 19) and insertions encoding glycine and aspartic acid at amino acid positions 134 and 135 (ins aa 134 and 135 GD; n = 21) (Table 1). The remaining ompK36 mutants (n = 5) had various other mutations (Table 1). Sixty-nine percent (43/62) and 20% (2/10) of KPC-2- and KPC-3-producing strains harbored mutant ompK36 genes, respectively (Table 1; P = 0.004). Only 2% (1/62) of KPC-2 strains carried wild-type ompK36 and lacked an ESBL, compared to 40% (4/10) of KPC-3 strains (P = 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Genetic characteristics of KPC-Kp strainsa

| Factor | Values | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KPC-2 (n = 62) | KPC-3 (n = 10) | ||

| β-Lactamases | |||

| SHV, n (%) of strains | 62 (100) | 9 (90) | 0.14 |

| TEM, n (%) of strains | 59 (95) | 9 (90) | 0.46 |

| CTX-M, n (%) of strains | 5 (8) | 1 (10) | 1.00 |

| Any ESBL, n (%) of strains | 57 (92) | 6 (60) | 0.02 |

| Porin mutations | |||

| OmpK35, n (%) of strains | 62 (100) | 8 (80) | 0.02 |

| OmpK36, n (%) of strains | 43 (69) | 2 (20) | 0.004 |

| ins aa 134 + 135 GD, n (%) of strains | 21 (34) | 0 (0) | 0.03 |

| IS_5_, n (%) of strains | 17 (27) | 2 (20) | 1.00 |

| Other, n (%) of strainsb | 5 (8) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Median MIC | |||

| Doripenem (μg/ml) (range) | 64 (4–256) | 12 (2–128) | 0.046 |

| Ceftazidime (μg/ml) (range) | 512 (64–1,024) | 512 (256–4,096) | 0.01 |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam (μg/ml) (range) | 1 (0.12–4) | 2 (0.5–4) | 0.02 |

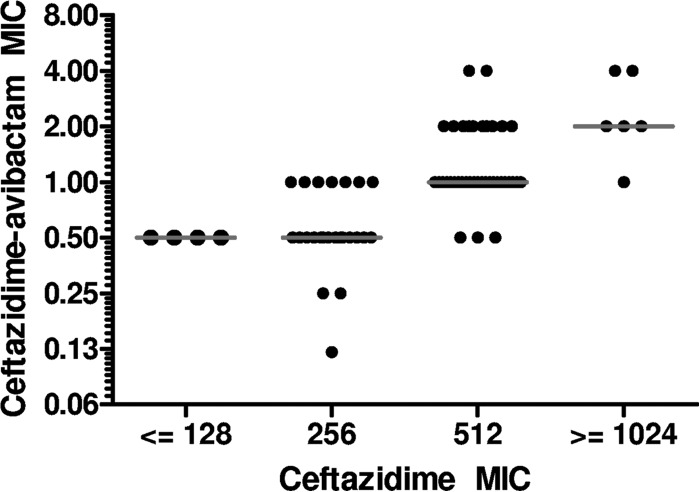

Ceftazidime MICs ranged from 64 to 4,096 μg/ml. The addition of avibactam lowered MICs by a median of 512-fold (range, 128 to 2,048). The resulting ceftazidime-avibactam MIC50 and MIC90 were 1 and 2 μg/ml, respectively. All ceftazidime-avibactam MICs were at or below the CLSI ceftazidime susceptibility breakpoint of ≤4 μg/ml (range, 0.12 to 4 μg/ml). Ceftazidime-avibactam MICs correlated with ceftazidime MICs (Fig. 1). Ceftazidime and ceftazidime-avibactam MICs were higher against KPC-3-producing strains than against KPC-2-producing strains (Table 1; P = 0.01 and P = 0.02, respectively). MICs against KPC-Kp did not vary with the presence of SHV, TEM, or CTX-M type beta-lactamases specifically.

FIG 1.

Correlation between ceftazidime and ceftazidime-avibactam MICs against KPC-Kp strains. Horizontal lines indicate median ceftazidime-avibactam MICs.

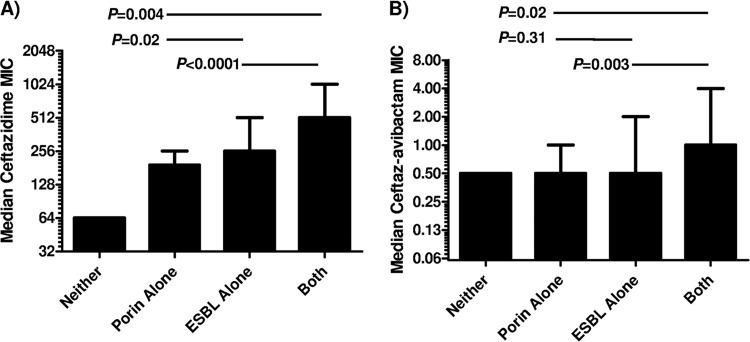

KPC-2-Kp strains exhibiting ceftazidime MICs of ≥512 (n = 36) were more likely to be ESBL positive (100%) and to harbor ompK36 porin mutations (89%, 32/36) than those with ceftazidime MICs of ≤256 μg/ml (81% [21/26] and 42% [11/26], respectively; P = 0.01 and 0.0002). Using a ceftazidime-avibactam MIC cutoff of ≥1 μg/ml (n = 40), strains were also more likely to be ESBL positive (98% versus 81%; P = 0.049) and to harbor ompK36 mutations (83% versus 45%; P = 0.004) than strains with MICs of ≤0.5 μg/ml. Ceftazidime and ceftazidime-avibactam MICs were significantly higher against KPC-2 strains with both an ESBL mutation and a ompK36 porin mutation than against strains with either resistance mechanism alone (Table 2). There was a stepwise increase in ceftazidime MICs against KPC-2 strains with ompK36 mutations alone (median MIC = 192 μg/ml), ESBL alone (median MIC = 256 μg/ml), and both ompK36 mutations and ESBL (median MIC = 512 μg/ml) (Fig. 2A). When avibactam was added to ceftazidime, differences in MICs against strains with ompK36 mutations alone and ESBL alone were no longer evident (Fig. 2B). Ceftazidime-avibactam MICs remained significantly elevated against KPC-2 strains with both ompK36 mutations and ESBL. The presence of an ESBL and/or ompK36 mutation did not impact median ceftazidime and ceftazidime-avibactam MICs against KPC-3-producing strains (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effects of ESBL and ompK36 porin mutations on ceftazidime and ceftazidime-avibactam MICsa

| KPC subtype | Resistance mechanism | Resistance mechanism | Median MIC (μg/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftazidime | Ceftazidime-avibactam | |||

| KPC-2 | Without ESBL | Wild-type porin (n = 1) | 64 | 0.5 |

| Mutant porin (n = 4) | 192 | 0.5 | ||

| P value | NA | NA | ||

| With ESBL | Wild-type porin (n = 18) | 256 | 0.5 | |

| Mutant porin (n = 39) | 512 | 1 | ||

| P value | <0.0001 | 0.003 | ||

| Wild-type porin | Without ESBL (n = 1) | 64 | 0.5 | |

| With ESBL (n = 18) | 256 | 0.5 | ||

| P value | NA | NA | ||

| Mutant porin | Without ESBL (n = 4) | 192 | 0.5 | |

| With ESBL (n = 39) | 512 | 1 | ||

| P value | 0.0004 | 0.02 | ||

| KPC-3 | Without ESBL | Wild-type porin (n = 4) | 512 | 3 |

| Mutant porin (n = 0) | NA | NA | ||

| P value | NA | NA | ||

| With ESBL | Wild-type porin (n = 4) | 768 | 1.5 | |

| Mutant porin (n = 2) | 2304 | 1.25 | ||

| P value | 0.23 | 0.71 | ||

| Wild-type porin | Without ESBL (n = 4) | 512 | 3 | |

| With ESBL (n = 4) | 768 | 1.5 | ||

| P value | 0.76 | 0.45 | ||

| Mutant porin | Without ESBL (n = 0) | NA | NA | |

| With ESBL (n = 2) | 2304 | 1.25 | ||

| P value | NA | NA |

FIG 2.

Stepwise increase in median MICs for ceftazidime (A) and ceftazidime-avibactam (B) against KPC-2-Kp strains by mechanisms of resistance. Median MICs are presented; error bars indicate ranges of values.

DISCUSSION

The most encouraging finding of this study is that ceftazidime-avibactam was active against highly resistant, genetically diverse KPC-Kp strains. Therefore, ceftazidime-avibactam provides a novel therapeutic option against strains that are refractory to most other antimicrobial agents. Indeed, our data show that avibactam potentiates ceftazidime activity, resulting in MICs that are at or below the CLSI ceftazidime susceptibility breakpoint (≤4 μg/ml) (10). At the same time, it is notable that 24% (17/72) of the strains exhibited MICs within two 2-fold dilutions of the CLSI breakpoint and would be classified as ceftazidime nonsusceptible by EUCAST criteria (susceptible MIC, ≤1 μg/ml) (11). Previous studies have demonstrated higher ceftazidime-avibactam MICs against CRE- and ESBL-expressing strains than against susceptible strains (1, 12). Taken together, those data and ours provide important cautionary notes as clinicians begin to integrate the use of ceftazidime-avibactam into clinical practice.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show an association between KPC subtypes and ceftazidime-avibactam MICs. Indeed, KPC-3-producing strains exhibited higher MICs than KPC-2 producers (Table 1). A total of 60% of KPC-3-Kp strains exhibited ceftazidime-avibactam MICs of >1 μg/ml compared to only 17% of KPC-2-Kp strains (P = 0.009). We have previously shown that the majority of KPC-Kp strains at our center belong to the epidemic ST258 clone (2–5). Interestingly, whole-genome sequencing data indicate that these ST258 strains, although clonal by conventional criteria, can be grouped into two distinct clusters that correlate with KPC-2 and KPC-3 variants (M. H. Nguyen and B. N. Kreiswirth, unpublished data). Furthermore, strains within each cluster are highly heterogeneous with respect to resistant determinants such as ompK36 genotypes and aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (2, 4). Along this line, the KPC-2-Kp strains in the current study were genetically and phenotypically distinct from KPC-3-Kp strains. For example, KPC-2-Kp strains were more likely to harbor ompK35 and ompK36 gene mutations and they exhibited higher median carbapenem MICs (Table 1).

The presence of an ESBL or ompK36 mutation(s) did not contribute to higher ceftazidime-avibactam MICs against KPC-3 strains (Table 2). KPC-3 has 30× greater hydrolytic activity against ceftazidime than KPC-2 (13). Given the correlation between ceftazidime and ceftazidime-avibactam MICs that we identified (Fig. 1), it is possible that higher ceftazidime-avibactam MICs against KPC-3-Kp are due to higher resistance to ceftazidime among these strains. It is also possible that avibactam covalently binds KPC-3 with less affinity than KPC-2. Alternatively, the KPC subtype carried by a particular strain may be a marker for an uncharacterized genetic factor that accounts for differences in MICs. Few studies of ceftazidime-avibactam activity have differentiated KPC subtypes, but a KPC-3-Kp strain exhibiting a ceftazidime-avibactam MIC of 8 μg/ml was recently reported (14). It will be important for future epidemiologic studies to differentiate KPC-3-Kp strains from strains carrying other KPC variants in order to best define the role of ceftazidime-avibactam in the clinic.

Only one KPC-2 strain did not have either an ESBL or a ompK36 mutation, and only 4 ompK36 mutant strains lacked ESBL. Therefore, our ability to assess the impact of these resistance mechanisms individually was limited, particularly for ompK36 mutations. Nevertheless, KPC-2 strains with an ESBL alone exhibited higher ceftazidime MICs than strains with an ompK36 mutation alone (Fig. 2A). The elimination of this difference upon addition of avibactam was consistent with avibactam's reported activity against ESBL-producing Gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 2B). KPC-2 strains with both ESBL and an ompK36 mutation were significantly less susceptible to ceftazidime and ceftazidime-avibactam than strains with either mechanism alone (Table 2 and Fig. 2). These data suggest that ompK36 mutations attenuate susceptibility to ceftazidime, albeit to a lesser extent than we previously reported for carbapenems (6). In this regard, entry of ceftazidime into the periplasmic space may be less dependent on the major OMPs, OmpK35 and OmpK36, than entry of carbapenems (15). The mechanisms by which an ompK36 mutation and ESBL synergize in diminishing susceptibility to ceftazidime and ceftazidime-avibactam are not immediately clear. As strains become increasingly resistant to ceftazidime, it is possible that they accumulate mechanisms of resistance, such as altered penicillin-binding proteins and efflux pump expression, that are not affected by avibactam. Alternatively, by restricting access to the active site within the periplasmic space, porin mutations may leave higher concentrations of drugs exposed to KPCs and ESBLs for longer periods. Under such conditions, hydrolytic effects that are not apparent in the absence of a porin mutation may be unmasked.

The discrepancy between the percentages of the strains defined as susceptible to ceftazidime-avibactam by CLSI and EUCAST ceftazidime criteria highlights the need to define conclusive breakpoint MICs. Existing breakpoints are based on a ceftazidime dosing regimen of 1 g every 8 h as a 30-min infusion (10). In completed and ongoing clinical trials, ceftazidime-avibactam has been administered as 2 g of ceftazidime and 500 mg of avibactam over the course of a 2-h infusion (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (12). The same dosing regimen modeled in a hollow-fiber pharmacodynamic model was effective in completely suppressing high-level-AmpC-producing Enterobacteriaceae (16). Moreover, in murine models of bacteremia due to ceftazidime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, a 4:1 ratio of ceftazidime to avibactam proved effective in treating strains producing AmpC or CTX-M (17). Despite limited pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic data, the available in vitro, in vivo, and clinical evidence seems to indicate that a ceftazidime-avibactam susceptibility breakpoint could be equal to or even higher than current ceftazidime breakpoints.

In conclusion, ceftazidime-avibactam was active against KPC-Kp strains that harbored diverse antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. On balance, our findings are consistent with previous studies that showed ceftazidime-avibactam to be highly active against Enterobacteriaceae that do not produce Ambler class B β-lactamases (1, 12, 14). However, concerning trends for higher MICs were identified, and as such, there is reason for judicious use of this agent. It is possible that strains carrying ESBLs and ompK36 porin mutations may present a platform upon which further resistance may emerge with widespread ceftazidime-avibactam usage. Future studies should evaluate the role of combining ceftazidime-avibactam with agents such as colistin or aminoglycosides to limit the development of resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by funding provided to the XDR Pathogen Laboratory by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and by the National Center for Advanced Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number KL2 RR024154 (awarded to R.K.S.).

The content is solely our responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flamm RK, Farrell DJ, Sader HS, Jones RN. 2014. Ceftazidime/avibactam activity tested against Gram-negative bacteria isolated from bloodstream, pneumonia, intra-abdominal and urinary tract infections in US medical centres (2012). J Antimicrob Chemother 69:1589–1598. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clancy CJ, Chen L, Shields RK, Zhao Y, Cheng S, Chavda KD, Hao B, Hong JH, Doi Y, Kwak EJ, Silveira FP, Abdel-Massih R, Bogdanovich T, Humar A, Perlin DS, Kreiswirth BN, Hong Nguyen M. 2013. Epidemiology and molecular characterization of bacteremia due to carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 13:2619–2633. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Potoski BA, Press EG, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Clarke LG, Eschenauer GA, Clancy CJ. 2015. Doripenem MICs and ompK36 porin genotypes of sequence type 258, KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae may predict responses to carbapenem-colistin combination therapy among patients with bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1797–1801. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03894-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almaghrabi R, Clancy CJ, Doi Y, Hao B, Chen L, Shields RK, Press EG, Iovine NM, Townsend BM, Wagener MM, Kreiswirth B, Nguyen MH. 27 May 2014. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains exhibit diversity in aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, which exert differing effects on plazomicin and other agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother doi: 10.1128/AAC.00099-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clancy CJ, Chen L, Hong JH, Cheng S, Hao B, Shields RK, Farrell AN, Doi Y, Zhao Y, Perlin DS, Kreiswirth BN, Nguyen MH. 2013. Mutations of the ompK36 porin gene and promoter impact responses of sequence type 258, KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains to doripenem and doripenem-colistin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5258–5265. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01069-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clancy CJ, Hao B, Shields RK, Chen L, Perlin DS, Kreiswirth BN, Nguyen MH. 2014. Doripenem, gentamicin, and colistin, alone and in combinations, against gentamicin-susceptible, KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains with various ompK36 genotypes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3521–3525. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01949-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Mediavilla JR, Endimiani A, Rosenthal ME, Zhao Y, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2011. Multiplex real-time PCR assay for detection and classification of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase gene (bla KPC) variants. J Clin Microbiol 49:579–585. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01588-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L, Chavda KD, Mediavilla JR, Zhao Y, Fraimow HS, Jenkins SG, Levi MH, Hong T, Rojtman AD, Ginocchio CC, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2012. Multiplex real-time PCR for detection of an epidemic KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 clone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3444–3447. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00316-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2009. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard—8th ed: approved standard M07-A8 CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute. 2014. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (M100-S24). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2015. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 5.0. http://www.eucast.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sader HS, Castanheira M, Flamm RK, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. 2014. Antimicrobial activity of ceftazidime-avibactam against Gram-negative organisms collected from U.S. medical centers in 2012. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:1684–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alba J, Ishii Y, Thomson K, Moland ES, Yamaguchi K. 2005. Kinetics study of KPC-3, a plasmid-encoded class A carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:4760–4762. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4760-4762.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levasseur P, Girard AM, Miossec C, Pace J, Coleman K. 12 January 2015. In vitro antibacterial activity of the ceftazidime-avibactam combination against enterobacteriaceae, including strains with well-characterized beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother doi: 10.1128/AAC.04218-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai YK, Fung CP, Lin JC, Chen JH, Chang FY, Chen TL, Siu LK. 2011. Klebsiella pneumoniae outer membrane porins OmpK35 and OmpK36 play roles in both antimicrobial resistance and virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1485–1493. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01275-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman K, Levasseur P, Girard AM, Borgonovi M, Miossec C, Merdjan H, Drusano G, Shlaes D, Nichols WW. 2014. Activities of ceftazidime and avibactam against beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a hollow-fiber pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3366–3372. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00080-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levasseur P, Girard AM, Lavallade L, Miossec C, Pace J, Coleman K. 2014. Efficacy of a ceftazidime-avibactam combination in a murine model of septicemia caused by Enterobacteriaceae species producing AmpC or extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:6490–6495. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03579-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]