Toll-Like Receptor 9 Promotes Steatohepatitis by Induction of Interleukin-1β in Mice (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2015 Nov 3.

Published in final edited form as: Gastroenterology. 2010 Mar 27;139(1):323–34.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.052

Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

Development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) involves the innate immune system and is mediated by Kupffer cells and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) is a pattern recognition receptor that recognizes bacteria-derived cytosine phosphate guanine (CpG)–containing DNA and activates innate immunity. We investigated the role of TLR9 signaling and the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1_β_ (IL-1_β_) in steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and insulin resistance.

METHODS

Wild-type (WT), TLR9−/−, IL-1 receptor (IL-1R)−/−, and MyD88−/− mice were fed a choline-deficient amino acid-defined (CDAA) diet for 22 weeks and then assessed for steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and insulin resistance. Lipid accumulation and cell death were assessed in isolated hepatocytes. Kupffer cells and HSCs were isolated to assess inflammatory and fibrogenic responses, respectively.

RESULTS

The CDAA diet induced NASH in WT mice, characterized by steatosis, inflammation, fibrosis, and insulin resistance. TLR9−/− mice showed less steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis than WT mice. Among inflammatory cytokines, IL-1_β_ production was suppressed in TLR9−/− mice. Kupffer cells produced IL-1_β_ in response to CpG oligodeoxynucleotide. IL-1_β_ but not CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides, increased lipid accumulation in hepatocytes. Lipid accumulation in hepatocytes led to nuclear factor-κ_B inactivation, resulting in cell death in response to IL-1_β. IL-1_β_ induced fibrogenic responses in HSCs, including secretion of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1. IL-1R−/− mice had reduced steatohepatitis and fibrosis, compared with WT mice. Mice deficient in MyD88, an adaptor molecule for TLR9 and IL-1R signaling, also had reduced steatohepatitis and fibrosis. TLR9−/−, IL-1R−/−, and MyD88−/− mice had less insulin resistance than WT mice on the CDAA diet.

CONCLUSIONS

In a mouse model of NASH, TLR9 signaling induces production of IL-1_β_ by Kupffer cells, leading to steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis.

Keywords: Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases, Toll-Like Receptors, Bacterial DNA, Bambi

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is one of the most common liver diseases in the United States and is becoming a significant public health concern worldwide. NAFLD is a hepatic component of the metabolic syndrome, which is characterized by visceral fat accumulation, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.1,2 Although NAFLD is generally a benign liver disease, a subset of NAFLD includes progressive liver disease designated nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). An emerging concept is that the innate immune system mediates the development of NASH.3 In NASH, Kupffer cells, hepatic resident macrophages, are the primary cells that produce various inflammatory and fibrogenic mediators, which involve the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs).4 Activated HSCs produce chemokines, cytokines, and excessive extracellular matrix, resulting in fibrosis.5,6

As a component of the innate immune system, Toll-like receptors (TLRs) recognize highly conserved microbial structures as pathogen-associated molecular patterns such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS).7 Thirteen TLRs have been identified in mammals for host defense against microorganisms. TLRs, except for TLR3, use MyD88, an essential adaptor molecule, to activate transcription factors, such as nuclear factor-_κ_B (NF-_κ_B), activator protein 1 (AP-1), and interferon regulatory factors that induce inflammatory cytokines and interferon-inducible genes.7 TLRs are associated with liver diseases, including alcoholic liver injury, ischemic-reperfusion injury, liver fibrosis, and liver cancer.8–10 Indeed, mice mutated in TLR4 and MyD88 are resistant to liver damage and fibrosis both in toxin-induced and cholestasis-induced liver injury.10,11 Thus, the TLR-MyD88 pathway plays an important role in liver injury and fibrosis as well as host defense.

TLR9 is a receptor for unmethylated cytosine phosphate guanine (CpG)–containing DNA, a major component of bacterial DNA.7,12 In chronic liver disease, bacterial DNA is often detected in blood and ascites in both rodents and human beings.13,14 Host-derived denatured DNA from apoptotic cells is also recognized by TLR9 as an endogenous ligand.15,16 Thus, liver cells might be exposed to high levels of TLR9 ligands after liver injury. Indeed, TLR9−/− mice exhibit reduced liver injury and fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride, acetaminophen, and bile duct ligation, indicating that TLR9 plays a crucial role in liver diseases.15–17 However, the role of TLR9 in the development of NASH is unknown.

The present study investigated the role of TLR9 and downstream signaling in the setting of steatohepatitis induced by a choline-deficient amino-acid defined (CDAA) diet. We show that TLR9 expression in Kupffer cells and subsequent interleukin-1_β_ (IL-1_β_) production are important for the development of NASH.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice and IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) −/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). TLR9−/− and MyD88−/− mice backcrossed at least 10 generations onto the C57BL/6 background were a gift from Dr Akira (Osaka University, Japan).12,18 These null mice exhibited similar hepatobiliary phenotypes and hepatic lipid contents when fed standard laboratory chow (Supplementary Table 1). Male mice were divided into 3 groups at 8 weeks old; standard chow group (PicoLab Rodent Diet 20 series, Catalog no. 5053; LabDiet, Framingham, MA); choline-supplemented L-amino acid defined diet (CSAA; catalog no. 518754; Dyets Inc, Bethlehem, PA); and choline-deficient L-amino acid defined diet (catalog no. 518753; Dyets Inc).19 Both CSAA and CDAA diets contain higher calories than standard chow (Supplementary Table 2). These diets were continued for 22 weeks. In some experiments, Kupffer cells were depleted by liposomal clodronate.11,20 Briefly, 200 _μ_L of liposomal clodronate was injected into the mice intravenously after 21 weeks of CDAA diet feeding, and then mice were killed 1 week later. The food intake on the CDAA diet was monitored for 1 month. The mice received humane care according to US National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommendations outlined in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.” All animal experiments were approved by the University of California San Diego Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Histologic Examination

H&E, Oil-Red O, TdT (terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase)–mediated dUTP (2′-deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate)–biotin neck end labeling (TUNEL), and Sirius red staining were performed.11,21 TUNEL-positive cells were counted on 10 high power (400×) fields/slide. The Sirius red–positive area was measured on 10 low power (40×) fields/slide and quantified with the use of NIH imaging software. NAFLD activity score was determined as described.22 Immunohistochemistry for F4/80, desmin, and CD31 was performed.11

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

Extracted RNA from livers and cells was subjected to reverse transcription and subsequent quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the use of ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems).11 PCR primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Genes were normalized to 18S RNA as an internal control.

Lipid Isolation and Measurement

Triglyceride, total cholesterol, and free fatty acid contents were measured with the use of Triglyceride Reagent Set (Pointe Scientific, Canton, MI), Cholesterol E (Wako, Richmond, VA), free fatty acid, and half micro test (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Assessment of Insulin Resistance

Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as [immunoreactive insulin (_μ_U/mL) × fasting blood sugar (mg/dL) ÷ 405].23

Cell Isolation and Treatment

Hepatocytes, HSCs, and Kupffer cells were isolated from mice as previously described.11,21 After cell attachment, hepatocytes were serum starved for 16 hours. The culture media for Kupffer cells and HSCs were changed to 1% serum for 16 hours followed by treatment with 10 ng/mL IL-1_β_, 5 _μ_g/mL CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN; ODN1826: 5′-tccatgacgttcctgacgtt-3′), and 5_μ_g/mL non–CpG-ODN (5′-tccatgagcttcctgagctt-3′). Liver cells were fractionated into 4 cell populations (hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, endothelial cells, and HSCs) as described.19

Assessment of Cell Death

Apoptosis and necrosis were determined with the use of Hoechst33342 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) and propidium iodide staining as described.21

Adenoviruses

For measurement of NF-_κ_B activation, a recombinant adenovirus expressing a luciferase reporter gene driven by NF-_κ_B activation was used.11,24 To inhibit NF-_κ_B activation, a recombinant adenovirus expressing inhibitor of NF-_κ_B (I_κ_B) super-repressor was used.11,21,24

Measurement for IL-1β

Enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used for measuring IL-1_β_ in serum and supernatant.

Western Blot Analysis

Supernatant or protein extracts (20 _μ_L) were electrophoresed and then blotted. Blots were incubated with antibody for tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP1; R&D Systems) or IL-1R–associated kinase M (IRAK-M; Cell Signaling Technology Inc, Danvers, MA).11,24

Statistical Analysis

Differences between the 2 groups were compared with Mann-Whitney U test. Differences between multiple groups were compared with 1-way analysis of variance (GraphPad Prism 4.02; GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). A P value of <.05 was considered significant.

Results

TLR9 Signaling Induces Steatohepatitis and Fibrosis

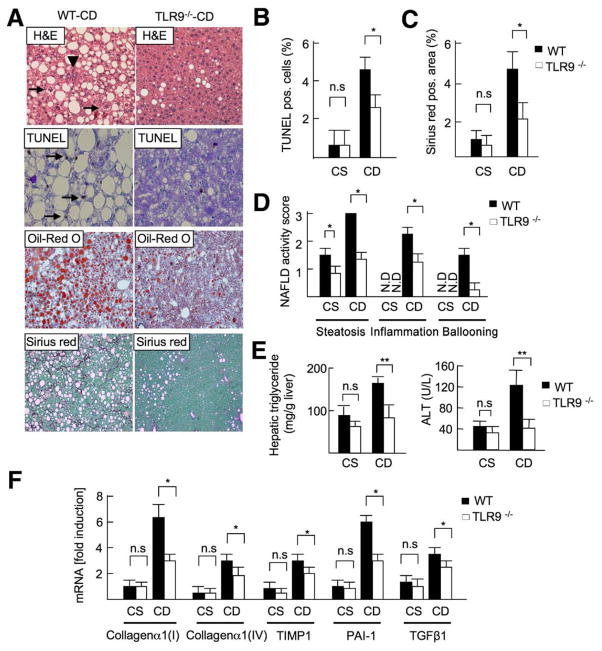

We investigated the contribution of TLR9 in a murine model of NASH. WT and TLR9−/− mice were fed a CDAA or control CSAA diet for 22 weeks. WT mice had marked lipid accumulation with inflammatory cell infiltration, hepatocyte death, and liver fibrosis (Figure 1A–C; Supplementary Figure 1) after CDAA diet feeding. In contrast, TLR9−/− mice had a significant reduction of steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis compared with WT mice (Figure 1_A–C_). No significant differences were observed in food intake between WT and TLR9−/− mice (Supplementary Figure 2). The NAFLD activity score, as determined by the degree of steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning, was significantly lower in TLR9−/− mice than in WT mice (total score, WT vs TLR9−/− mice = 6.5 vs 2.6; P < .01) (Figure 1_D_).22 Reduced steatosis and liver injury in TLR9−/− mice were confirmed by lower levels of hepatic triglyceride and serum alanine transaminase (ALT; Figure 1_E_). In accordance with reduced liver fibrosis examined by Sirius red staining, mRNA levels of collagen _α_1(I), collagen α_1(IV), TIMP1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), and transforming growth factor β (TGF_β) were markedly suppressed in TLR9−/− mice (Figure 1_F_). These results suggest that TLR9 signaling is required for the progression of NASH.

Figure 1.

TLR9 deficiency attenuates steatohepatitis. WT and TLR9−/− mice were fed a CSAA (CS; n = 4) or CDAA (CD; n = 8) diet for 22 weeks. Closed bar, WT mice; open bar, TLR9−/− mice. (A) Liver sections were stained with H&E (arrowheads, inflammatory cells; arrows, ballooning hepatocytes), Oil-Red O, TUNEL (arrows; apoptotic cells), and Sirius red. Original magnification, ×200 for H&E and TUNEL staining, ×100 for Oil-Red O and Sirius red stainings. (B) Number of TUNEL-positive cells, (C) Sirius red–positive area and (D) NAFLD activity score were calculated. N.D., not detected. (E) Hepatic triglyceride and serum ALT levels were measured. (F) Hepatic mRNA levels of fibrogenic markers were determined by quantitative real-time PCR. Data represent mean ± SD; *P < .05; n.s., not significant.

Kupffer Cell–Derived IL-1β Is Suppressed in TLR9−/− Mice

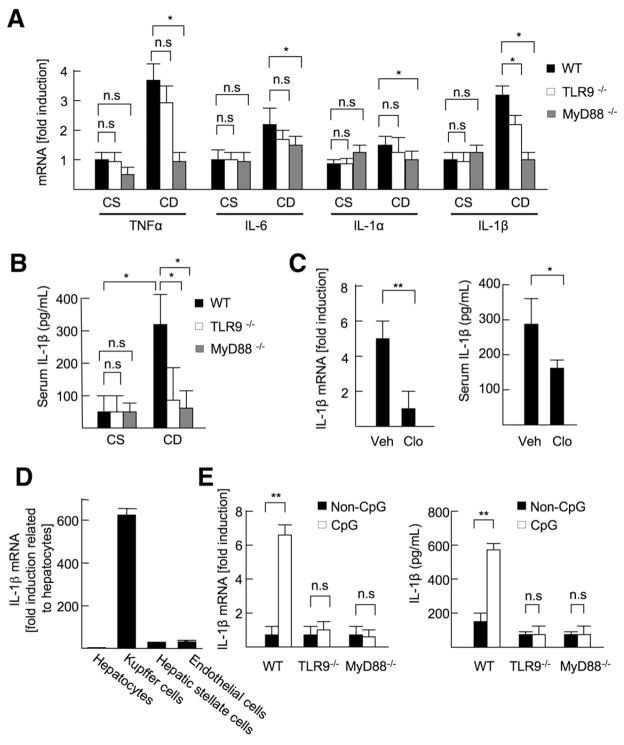

To determine the key molecules responsible for the attenuated steatohepatitis in TLR9−/− mice, we examined hepatic mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF_α_), IL-6, IL-1_α_ and IL-1_β_, mRNA levels of inflammatory cytokines in mice deficient in MyD88, an adaptor molecule for TLR9 signaling, were completely suppressed after CDAA diet feeding (Figure 2_A_). Among these inflammatory cytokines, the IL-1_β_ mRNA level was significantly suppressed in TLR9−/− mice (Figure 2_A_). TLR9−/− mice showed a similar reduction of the serum IL-1_β_ level of MyD88−/− mice (Figure 2_B_), suggesting that TLR9-dependent MyD88-mediated IL-1_β_ is an important factor in the progression of NASH.

Figure 2.

TLR9 induces IL-1_β_ production in Kupffer cells. (A and B) The livers and sera were harvested from 22-week-old CSAA (CS) or CDAA (CD) diet-fed WT, TLR9−/−, and MyD88−/− mice. (A) Hepatic mRNA levels of inflammatory cytokines were measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). (B) Serum IL-1_β_ levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA). (C) WT mice (21 weeks old) fed the CDAA diet were injected control (Veh; n = 6) or clodronate liposome (Clo; n = 6) to deplete Kupffer cells. The livers and sera were harvested 1 week after the liposome injection. Hepatic mRNA and serum protein levels of IL-1_β_ were measured by qPCR and ELISA, respectively. (D) IL-1_β_ mRNA expression in hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, HSCs, and sinusoidal endothelial cells was measured by qPCR. (E) WT, TLR9−/−, and MyD88−/− Kupffer cells were treated with 5 μ_g/mL CpG-ODN or non–CpG-ODN, and then IL-1_β mRNA levels were measured by qPCR. To convert active IL-1_β_ from proIL-1_β_, Kupffer cells were treated with 2 mmol/L ATP for 30 minutes after 24 hours of incubation with 5 μ_g/mL CpG-ODN (n = 4, each group), and then secreted IL-1_β levels were measured by ELISA. Data represent mean ± SD; *P < .05, **P < .01; n.s., not significant.

Because Kupffer cells are a primary source of IL-1_β_ in some models of liver injury,25,26 we determined the role of Kupffer cells in IL-1_β_ production. Intravenous injection of liposomal clodronate exclusively depleted Kupffer cells, but not HSCs or sinusoidal endothelial cells (Supplementary Figure 3). IL-1_β_ levels were significantly reduced at 1 week after the liposomal clodronate injection after 21 weeks on the CDAA diet (Figure 2_C_). In addition, we isolated hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, HSCs, and sinusoidal endothelial cells from WT mice after 22 weeks on the CDAA diet. High levels of IL-1_β_ mRNA expression were observed only in the Kupffer cell fraction (Figure 2_D_). These data indicate that Kupffer cells are the main source of IL-1_β_ in the CDAA diet.

Next, we tested whether a CpG-containing ODN, a synthetic TLR9 ligand, induces IL-1_β_ production in Kupffer cells. A CpG-ODN up-regulated IL-1_β_ mRNA in WT Kupffer cells but not in TLR9−/− or MyD88−/− Kupffer cells (Figure 2_E_). On activating caspase-1 with adenosine triphosphate (ATP),27 WT Kupffer cells secrete the active form of IL-1_β_ (Figure 2_E_). In contrast, CpG-ODN did not induce IL-1_β_ mRNA in either HSCs or hepatocytes isolated from WT mice, and the active form of IL-1_β_ was not detected in culture supernatant from HSCs and hepatocytes (data not shown). These results indicate that IL-1_β_ is primarily produced from Kupffer cells through TLR9 in NASH induced by the CDAA diet.

IL-1β Enhances Lipid Accumulation and Hepatocyte Injury

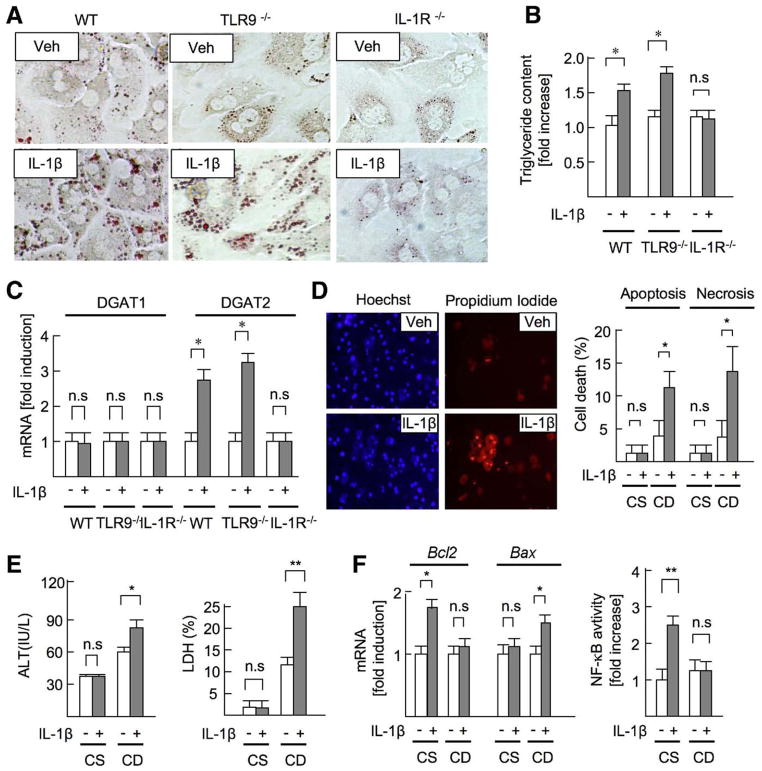

To determine the effect of IL-1_β_ on NASH, we examined whether IL-1_β_ affects lipid metabolism in hepatocytes. IL-1_β_ increased lipid droplet and triglyceride content in WT and TLR9−/− -cultured hepatocytes, but not IL-1R−/− hepatocytes (Figure 3_A_ and B). mRNA expression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 (DGAT2), an enzyme that converts diglyceride to triglyceride, was up-regulated in WT and TLR9−/− hepatocytes, but not in IL-1R−/− hepatocytes, after IL-1_β_ treatment (Figure 3_C_). These results indicate that IL-1_β_ induces lipid accumulation in hepatocytes.

Figure 3.

IL-1_β_ promotes lipid metabolism and cell death in hepatocytes. (A–C) WT, TLR9−/−, and IL-1R−/− hepatocytes were treated with 10 ng/mL IL-1_β_. Veh, vehicle. (A) Lipid accumulation (Oil-Red O staining) and (B) triglyceride content (normalized to protein concentration) were measured in WT, TLR9−/−, and IL-1R−/− hepatocytes treated with IL-1_β_ for 24 hours. (C) Hepatocytes were treated with IL-1_β_ for 8 hours. mRNA expression of DGATs in hepatocytes was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). (D–F) Hepatocytes were isolated from 22-week-old mice fed the CSAA (CS) or the CDAA (CD) diet. (D) Hepatocytes were treated with IL-1_β_ for 24 hours. Apoptosis and necrosis were determined by Hoechst33342 and propidium iodide, respectively. (E) ALT and LDH levels in supernatant were measured. (F, left) mRNA levels of Bcl2 and Bax were determined by qPCR. (F, right) NF-κ_B activity in response to IL-1_β was examined by NF-_κ_B–reporter assay. Data represent mean ± SD; *P < .05, **P < .01; n.s., not significant. Original magnification, ×400 (A), ×200 (C).

Next, we investigated the contribution of IL-1_β_ to hepatocyte death. In hepatocytes isolated from mice fed the CSAA diet, IL-1_β_ did not induce cell death (Figure 3_D_, right). However, IL-1_β_ increased apoptosis and necrosis in lipid-accumulated hepatocytes isolated from mice fed the CDAA diet (Figure 3_D_, left and right). In response to IL-1_β_, ALT and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels were elevated in supernatant from hepatocytes of mice fed the CDAA diet but not hepatocytes of mice fed the CSAA diet (Figure 3_E_). IL-1_β_ increased the expression of antiapoptotic gene Bcl2, but not proapoptotic gene Bax, in hepatocytes of mice fed the CSAA diet. Importantly, Bax, but not Bcl2, expression was up-regulated in hepatocytes of mice fed the CDAA diet after IL-1_β_ treatment (Figure 3_F_, left). NF-κ_B activation has an essential anti-apoptotic effect in hepatocytes.21 IL-1_β increased NF-κ_B activation in hepatocytes of mice fed the CSAA diet. Notably, NF-κ_B activation was blunted in hepatocytes of mice fed the CDAA diet after IL-1_β treatment (Figure 3_F_, right_). To determine the direct role of NF-κ_B in cell death induced by IL-1_β, NF-_κ_B activation was inhibited by an I_κ_B super-repressor in hepatocytes. With the inhibition of NF-κ_B activation, IL-1_β increased hepatocyte apoptosis and the levels of ALT and LDH (Supplementary Figure 4_A–C_), indicating that NF-_κ_B inactivation is crucial for determining the susceptibility of cell death in lipid-accumulated hepatocytes.

We also tested the direct effect of TLR9 signaling on hepatocytes. However, CpG-ODN had little effect on lipid accumulation and cell death in either normal hepatocytes or lipid-accumulated hepatocytes (Supplementary Figure 5_A–J_). These results indicate that IL-1_β_ mediates lipid accumulation and cell death in hepatocytes during NASH.

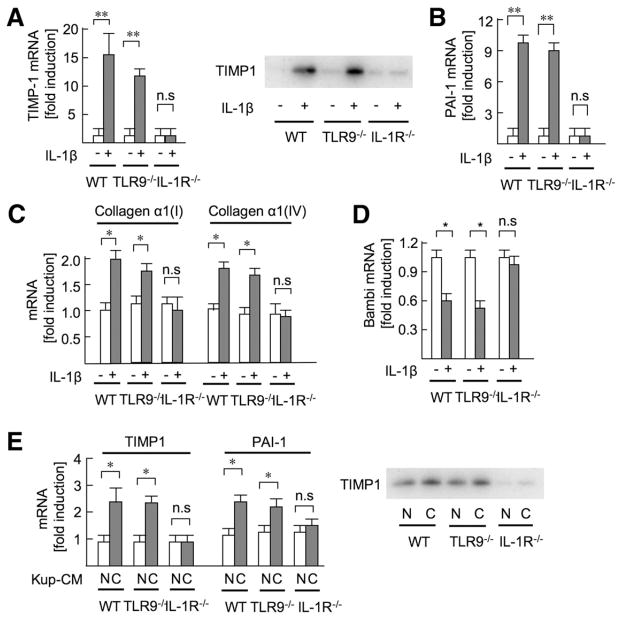

IL-1β Promotes the Activation of HSCs

Next, we examined whether IL-1_β_ mediates fibrogenic responses in HSCs, the main precursors of myofibroblasts in the liver. IL-1_β_ markedly elevated the mRNA and protein levels of TIMP1 in WT and TLR9−/− HSCs but not IL-1R−/− HSCs (Figure 4_A_). IL-1_β_ increased collagen α_1(I), collagen α_1(IV), and PAI-1 mRNA and suppressed mRNA expression of Bambi, a pseudoreceptor for TGF_β,11 that functions as a negative regulator of TGF_β signaling in hepatic fibrosis (Figure 4_B–D_). Although previous studies had reported that CpG-ODN induced fibrogenic responses in HSCs,15,17 our study shows that CpG-ODN has little effect on fibrogenic gene expression and NF-κ_B activation (Supplementary Figure 6). To determine the functional role of IL-1_β secreted from Kupffer cells, HSCs were incubated with conditioned medium derived from Kupffer cells treated with CpG- or non–CpG-ODN. Conditioned medium from cells treated with CpG-ODN, but not with non–CpG-ODN, increased TIMP1 and PAI-1 levels in WT and TLR9−/− HSCs. Notably, IL-1R−/− HSCs did not increase TIMP1 and PAI-1 levels in response to CpG-ODN–treated conditioned medium (Figure 4_E_). These results suggest that TLR9-mediated IL-1_β_ released from Kupffer cells is essential for HSC activation.

Figure 4.

Kupffer cell–derived IL-1_β_ promotes HSC activation. (A–D) HSCs isolated from WT, TLR9−/−, and IL-1R−/− mice were stimulated with 10 ng/mL IL-1_β_ for 8 hours to measure mRNA expression of TIMP1 (A), PAI-1 (B), collagen (C), and Bambi (D) by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), and for 24 hours to determine TIMP1 expression in the supernatant by Western blot (A). (E) Kupffer cell–conditioned medium (Kup-CM) was prepared by treating Kupffer cells with 5 _μ_g/mL CpG-ODN or non–CpG-ODN for 24 hours. Then, WT, TLR9−/−, and IL-1R−/− HSCs were treated with Kup-CM for 8 hours to determine mRNA expression of fibrogenic markers by qPCR (E, left) and for 24 hours to determine TIMP1 protein expression in the supernatant (E, right). Data represent mean ± SD; *P < .05, **P < .01; n.s., not significant.

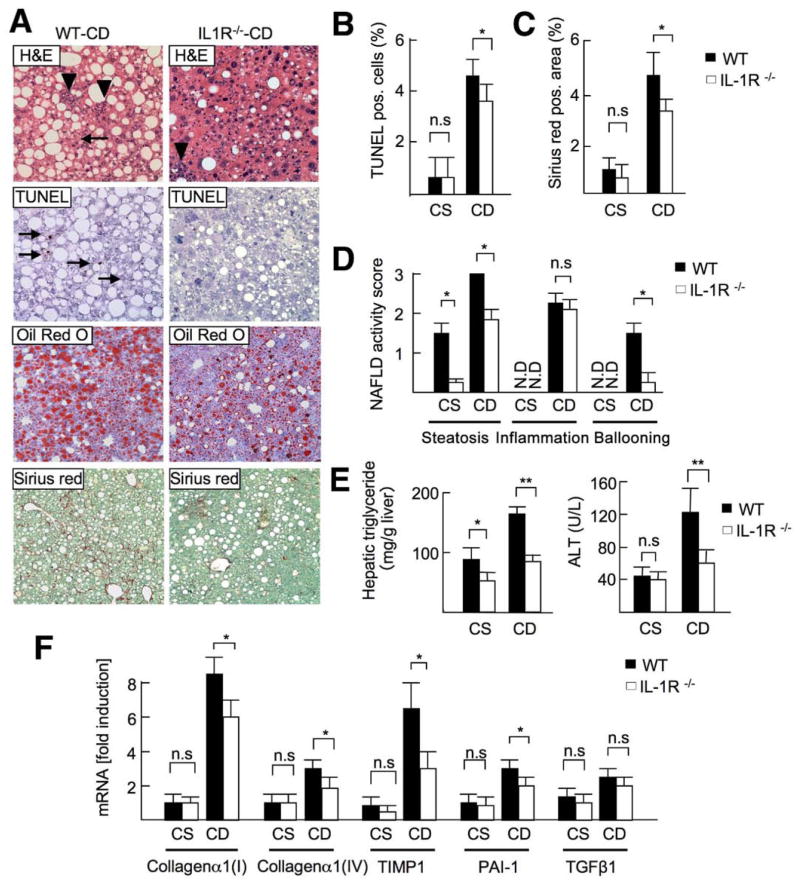

IL-1R−/− Mice Exhibit Reduced Steatosis, Hepatocyte Damage, and Fibrosis

To confirm the critical role of IL-1R signaling in NASH, IL-1R−/− mice were fed a CDAA diet for 22 weeks. IL-1R−/− mice exhibited less steatosis, apoptosis, and liver fibrosis (Figure 5_A–C_). The NAFLD activity score in IL-1R−/− mice was significantly lower than that in WT mice (total score, WT vs IL-1R−/− mice = 6.5 vs 4.6; P < .05); in particular, the scores for steatosis and hepatocyte ballooning but not inflammatory cell infiltration were smaller in IL-1R−/− mice (Figure 5_D_). Reduced steatosis was shown by decreased hepatic triglyceride content (Figure 5_E_). ALT levels were lower in IL-1R−/− mice (Figure 5_E_). Reduced liver fibrosis was confirmed by decreased mRNA levels of collagen _α_1(I), collagen _α_1(IV), TIMP1, and PAI-1 (Figure 5_F_). These findings indicate that IL-1R signaling contributes to steatosis, hepatocyte damage, and fibrosis.

Figure 5.

IL-1R−/− mice show attenuated steatosis and fibrosis. WT and IL-1R−/− mice were fed a CSAA diet (CS; n = 4) or CDAA diet (CD; n = 8) for 22 weeks. Closed bar, WT mice; open bar, IL-1R−/− mice. (A) H&E (arrowheads, inflammatory cells; arrows, ballooning hepatocytes), Oil-Red O, TUNEL (arrows; apoptotic cells), and Sirius red staining were performed. Original magnification, ×200 for H&E and TUNEL, ×100 for Oil-Red O and Sirius red. (B) Number of TUNEL-positive cells and (C) Sirius red–positive area were suppressed in IL-1R−/− mice. (D) NAFLD activity score, steatosis, and fibrosis were suppressed in IL-1R−/− mice. N.D., not detected. (E) Hepatic triglyceride and serum ALT levels were decreased in IL-1R−/− mice. (F) Hepatic mRNA levels of fibrogenic markers were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Data represent mean ± SD, *P < .05; n.s., not significant.

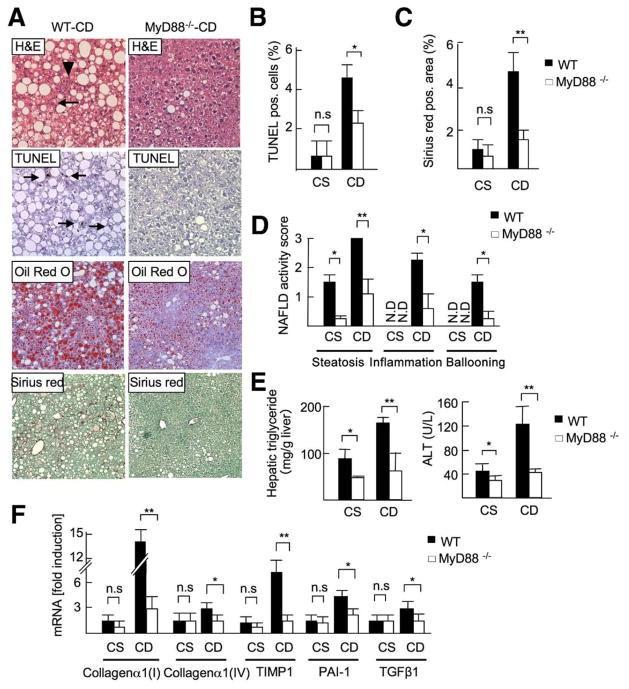

MyD88 Is a Critical Component for the Development of Steatohepatitis and Fibrosis

Because TLR9 and IL-1R signaling share the adaptor molecule MyD88, we investigated the role of MyD88 in NASH. Steatosis, inflammation, apoptosis, and fibrosis were remarkably inhibited in MyD88−/− mice fed a CDAA diet (Figure 6_A–C_). The NAFLD activity score was significantly lower in MyD88−/− mice (total score, WT vs MyD88−/− = 6.5 vs 2.0; P < .01), and every score was significantly less than that in WT mice (Figure 6_D_). Hepatic triglyceride and serum ALT levels were markedly reduced in MyD88−/− mice (Figure 6_E_). In addition, MyD88−/− mice had decreased mRNA levels of collagen _α_1(I), collagen _α_1(IV), TIMP-1, and PAI-1 (Figure 6_F_). These results implicate MyD88 as a crucial signaling molecule that promotes NASH and fibrosis.

Figure 6.

Gene deletion of MyD88 ameliorates steatohepatitis. WT and MyD88−/− mice were fed a CSAA (CS, n=4) or CDAA (WT-CD, n = 8; MyD88−/− -CD, n = 7) diet for 22 weeks. Closed bar, WT mice; open bar, MyD88−/− mice. (A) H&E (arrowheads, inflammatory cells; arrows, ballooning hepatocytes), Oil-Red O, TUNEL (arrows; apoptotic cells), and Sirius red staining show reduced steatosis, inflammatory cells, apoptosis, and fibrosis in MyD88−/− mice. Original magnification, ×200 for H&E and TUNEL staining, ×100 for Oil-Red O and Sirius red stainings. (B) TUNEL-positive cells, (C) Sirius red–positive area, and (D) NAFLD activity score were suppressed in MyD88−/− mice. N.D., not detected. (E) Hepatic triglyceride and serum ALT levels were suppressed in MyD88−/− mice. (F) Hepatic mRNA levels of fibrogenic markers were determined by quantitative real-time PCR. Data represent mean ± SD; *P < .05, **P < .01; n.s., not significant.

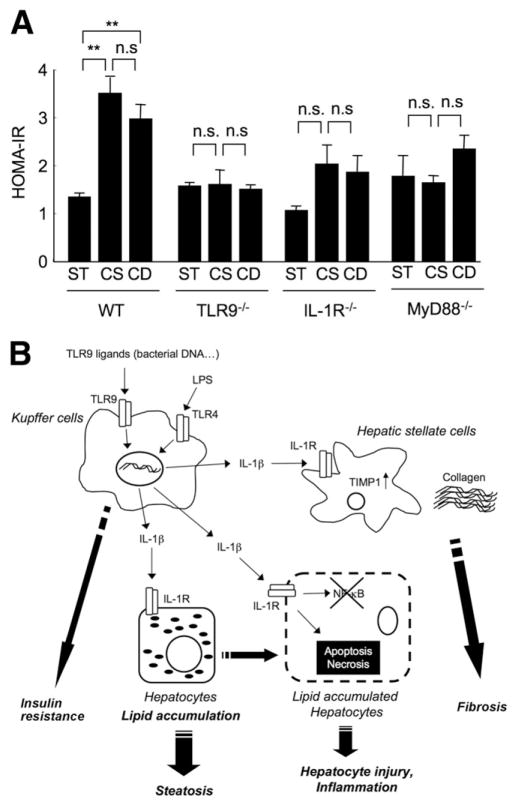

TLR9 Signaling Mediates Insulin Resistance Induced by CDAA Diet

Insulin resistance is observed in most patients with NASH.2 Therefore, we assessed HOMA-IR levels in TLR9−/−, IL-1R−/−, and MyD88−/− mice. A significant reduction of HOMA-IR was seen in TLR9−/− mice compared with that in WT mice receiving a CDAA diet (Figure 7). Furthermore, HOMA-IR was not increased in IL-1R−/− and MyD88−/− mice on a CDAA or CSAA diet compared with that in mice fed standard chow (Figure 7). These results indicate that TLR9, IL-1R, and MyD88 are crucial for the development of insulin resistance. However, both the CDAA and CSAA diets significantly increased the HOMA-IR level compared with standard chow in WT mice. The CDAA diet feeding resulted in NASH, whereas the CSAA diet feeding produced mild steatosis, indicating that insulin resistance is not correlated with the degree of NASH, which further suggests that insulin resistance may be associated with steatosis, but additional mediators through TLR9, IL-1R, and MyD88 are required for the development of NASH.

Figure 7.

(A) TLR9–MyD88–IL-1R axis promotes insulin resistance. Normal chow (N), CSAA (CS), and CDAA (CD) diets were fed to WT, TLR9−/−, IL-1R−/−, and MyD88−/− mice for 22 weeks (n = 6, each group). Insulin resistance was examined by HOMA-IR. Data represent mean ± SEM; **P < .01; n.s., not significant. (B) The proposed mechanism responsible for the development of NASH through TLR9 and IL-1_β_. TLR9 ligands, including bacterial DNA or other endogenous mediators, stimulate Kupffer cells to produce IL-1_β_. Secreted IL-1_β_ acts on hepatocytes to increase lipid accumulation and cell death, causing steatosis and inflammation. IL-1_β_ also stimulates HSCs to produce fibrogenic factors such as collagen and TIMP-1, resulting in fibrogenesis. Simultaneously, the TLR9-MyD88 axis promotes insulin resistance. TLR4 also contributes to this network in NASH as described previously.4

Discussion

The present study shows that steatohepatitis is diminished in TLR9−/−, IL-1R−/−, and MyD88−/− mice. Kupffer cells, but not hepatocytes and HSCs, respond to TLR9 ligands to produce IL-1_β_. This IL-1_β_ induces lipid accumulation and cell death in hepatocytes and the expression of fibrogenic mediators in HSCs, resulting in steatosis, hepatocyte injury, and fibrosis (Figure 7_B_).

Two possible mechanisms activate innate immune systems in NASH. First, translocated bacteria and their products activate the innate immune network as exogenous ligands in NASH.7–9,28 In chronic liver disease, including NASH, intestinal permeability is increased because of bacterial overgrowth or altered composition of bacterial microflora.29 Systemic inflammation related to NASH also injures epithelial tight junctions,30 resulting in deregulation of intestinal barrier functions. Indeed, plasma levels of LPS are elevated in patients with chronic liver diseases, including NASH.31 We and others have reported that TLR4, a receptor for LPS, promotes steatohepatitis and fibrosis.4,8 Bacterial DNA was also detected by PCR for bacterial 16S rRNA in the blood of mice fed a CDAA diet (data not shown), suggesting that translocated bacterial DNA could be an exogenous ligand in NASH. Second, dying hepatocytes in NASH supply denatured host DNA that may activate TLR9 as an endogenous ligand.16 Thus, exogenous and endogenous TLR9 ligands may activate the innate immune system through TLR9, which results in the development of steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and insulin resistance.

The prominent features of hepatocytes in NASH are excessive lipid accumulation and cell death. We determined that IL-1_β_ promotes lipid accumulation and triglyceride synthesis by up-regulating DGAT2 in hepatocytes. Increased triglyceride accumulation by IL-1_β_ was observed in TLR9−/− hepatocytes in vitro, indicating that lipid accumulation depends on IL-1_β_, but not TLR9, in hepatocytes. Our data suggest that a low level of IL-1_β_ is associated with reduced lipid accumulation in hepatocytes of TLR9−/− mice. We found that lipid-laden hepatocytes had blunted activation of NF-κ_B. Meanwhile, the expression of IRAK-M, a negative regulator of IL-1R signaling,7 was increased in lipid-laden hepatocytes (Supplementary Figure 7). As a result, lipid-laden hepatocytes are sensitive to IL-1_β_–induced cell death. Previous studies have shown that IL-1R antagonist–deficient mice on a high-fat diet have more severe steatohepatitis.32 In addition, an IL-1_β gene polymorphism is prevalently observed in patients with NASH.33 These studies are consistent with our conclusion that IL-1_β_ is important for the progression of NASH.

IL-1_β_ contributes to HSC activation by regulating fibrogenic factors. Among IL-1_β_–mediated profibrogenic factors, HSCs markedly increased the secretion of TIMP1, an inhibitor of matrix metalloproteases,34 which inhibits degradation of extracellular matrix to promote liver fibrosis. Indeed, transgenic mice overexpressing TIMP1 exhibit severe liver fibrosis induced by the treatment of carbon tetrachloride,35 and treatment with a neutralizing anti-TIMP1 antibody attenuates liver fibrosis.34 Moreover, TIMP1 inhibits HSC apoptosis.36 IL-1_β_ induced other fibrogenic factors, including PAI-1, collagen, and decreased the expression of Bambi, a pseudoreceptor for TGF_β_. Thus, IL-1_β_ plays an important role in fibrogenic responses in NASH. Although HSCs have been reported to be targets for TLR9 ligands,15,17 primary cultured HSCs barely responded to CpG-ODN in comparison to IL-1_β_ in our study (Supplementary Figure 6). However, conditioned medium derived from CpG-ODN–treated Kupffer cells strongly induced TIMP-1 expression in WT, but not IL-1R−/− HSCs (Figure 4_E_). These findings further confirmed our hypothesis that the critical mediator for HSC activation is IL-1 released from Kupffer cells.

Multiple TLRs and inflammatory cytokines mediate NASH. TLR4 promotes NASH by producing inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-1_β_.4 A synergistic interaction of TLR4 and TLR9 induces the highest expression of TNF-α,37,38 but it has not been reported in the IL-1_β_ production. Notably, TLR4 strongly activates caspase-1 that processes the proform of IL-1_β_ to active IL-1_β_ independently of ATP in Kupffer cells.39,40 We suggest that TLR4 activates caspase-1 that cooperates with TLR9 to induce the active IL-1_β_ in Kupffer cells. Then, IL-1_β_ promotes lipid accumulation and cell death in hepatocytes and fibrogenic responses in HSCs (Figures 3 and 4). However, IL-1R−/− mice had less of a reduction in liver injury, steatosis, and fibrosis than did MyD88−/− mice (Figures 5 and 6). TNF-α may also contribute to the development of NASH in IL-1R−/− mice, because TNF-α is increased to similar levels in IL-1R−/− and WT mice (data not shown) but lower in MyD88−/− mice. TNF-α is fibrogenic, by increasing TIMP-141 and decreasing Bambi expression in HSCs (data not shown).

Clinically, insulin resistance is strongly associated with the degree of NASH.42–47 However, recent studies have shown that an I148M mutation in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 protein (PNPLA3)/adiponutrin is associated with increased hepatic triglyceride content and ALT levels but independent of insulin resistance.48–51 In our study, both CSAA and CDAA diets induced a similar degree of insulin resistance as measured by HOMA-IR (Figure 7). The CDAA diet resulted in a significant steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis (Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1), whereas the CSAA control diet led to a more modest degree of steatosis without inflammation and fibrosis (Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1). These findings suggest that insulin resistance may be associated with some degree of steatosis but that the magnitude of the decreased insulin sensitivity in the current studies (Figure 7) is insufficient to cause NASH.

Overall, the CDAA diet is a useful model to investigate NASH. The CDAA diet induces fibrosis, systemic insulin resistance, and weight gain in addition to steatohepatitis (Figure 7; Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1). These findings are compatible to the pathophysiology of human NASH. So far, 2 diet models are widely used for the study of steatohepatitis in rodents: high-fat diet and methionine and choline deficient (MCD) diet. A high-fat diet induces weight gain and systemic insulin resistance as in most cases of human NASH. However, the high-fat diet induces steatosis, but not inflammation and fibrosis. The MCD diet is most widely used for studying NASH. However, mice fed the MCD diet have weight loss without insulin resistance.2,52

In summary, we demonstrate a novel role for the innate immune system in mediating NASH. TLR9-MyD88 signaling mediates IL-1_β_ production in Kupffer cells, which stimulates both hepatocytes and HSCs leading to the progression of NASH. Thus, the present study provides TLR9, MyD88, and IL-1_β_ as a potential target for the therapy of NASH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Shizuo Akira (Osaka University, Japan) for the generous gift of TLR9−/− and MyD88−/− mice and Dr Katsumi Miyai (Department of Pathology at UCSD), Dr Wuqiang Fan, Dr Saswata Talukdar, Rie Seki, and Karin Diggle (Department of Medicine at UCSD) for excellent technical assistance.

Funding

This study was supported by a Liver Scholar Award from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases/American Liver Foundation and by a pilot project from the Southern California Research Center for ALPD and Cirrhosis (P50 AA11999) funded by NIAAA (both to E.S.), NIH grants 5R01GM041804 and 5R01DK072237 (D.A.B.), and Takeda Science Foundation (K.M.).

Abbreviations used in this paper

ALT

alanine transaminase

ATP

adenosine triphosphate

CDAA

choline-deficient amino-acid defined

CpG

cytosine phosphate guanine

CSAA

choline-supplemented amino acid defined

DGAT2

diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2

HOMA-IR

homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

HSC

hepatic stellate cell

I_κ_B

inhibitor of NF-_κ_B

IL-1_β_

interleukin-1_β_

IL-1R

interleukin-1 receptor

IRAK-M

interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase M

LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

MCD

methionine and choline deficient

NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

NF-_κ_B

nuclear factor-_κ_B

NIH

National Institutes of Health

ODN

oligodeoxynucleotide

PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

PCR

polymerase chain reaction

TGF_β_

transforming growth factor β

TIMP1

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1

TLR

Toll-like receptor

TNF_α_

tumor necrosis factor α

TUNEL

TdT (terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase)–mediated dUTP (2-deoxyuridine 5-triphosphate)– biotin neck end labeling

WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.052.

References

- 1.Browning JD, Horton JD. Molecular mediators of hepatic steatosis and liver injury. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:147–152. doi: 10.1172/JCI22422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marra F, Gastaldelli A, Svegliati Baroni G, et al. Molecular basis and mechanisms of progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maher JJ, Leon P, Ryan JC. Beyond insulin resistance: innate immunity in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:670–678. doi: 10.1002/hep.22399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivera CA, Adegboyega P, van Rooijen N, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling and Kupffer cells play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2007;47:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawai T, Akira S. The roles of TLRs, RLRs and NLRs in pathogen recognition. Int Immunol. 2009;21:317–337. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seki E, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptors and adaptor molecules in liver disease: update. Hepatology. 2008;48:322–335. doi: 10.1002/hep.22306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szabo G, Dolganiuc A, Mandrekar P. Pattern recognition receptors: a contemporary view on liver diseases. Hepatology. 2006;44:287–298. doi: 10.1002/hep.21308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, et al. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science. 2007;317:121–124. doi: 10.1126/science.1140485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frances R, Zapater P, Gonzalez-Navajas JM, et al. Bacterial DNA in patients with cirrhosis and noninfected ascites mimics the soluble immune response established in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology. 2008;47:978–985. doi: 10.1002/hep.22083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guarner C, Gonzalez-Navajas JM, Sanchez E, et al. The detection of bacterial DNA in blood of rats with CCl4-induced cirrhosis with ascites represents episodes of bacterial translocation. Hepatology. 2006;44:633–639. doi: 10.1002/hep.21286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe A, Hashmi A, Gomes DA, et al. Apoptotic hepatocyte DNA inhibits hepatic stellate cell chemotaxis via toll-like receptor 9. Hepatology. 2007;46:1509–1518. doi: 10.1002/hep.21867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imaeda AB, Watanabe A, Sohail MA, et al. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice is dependent on Tlr9 and the Nalp3 inflammasome. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:305–314. doi: 10.1172/JCI35958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabele E, Muhlbauer M, Dorn C, et al. Role of TLR9 in hepatic stellate cells and experimental liver fibrosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, et al. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kodama Y, Kisseleva T, Iwaisako K, et al. c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1 from hematopoietic cells mediates progression from hepatic steatosis to steatohepatitis and fibrosis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1467–1477. e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kodama Y, Taura K, Miura K, et al. Antiapoptotic effect of c-Jun N-terminal Kinase-1 through Mcl-1 stabilization in TNF-induced hepatocyte apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1423–1434. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–4129. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miura K, Yoshino R, Hirai Y, et al. Epimorphin, a morphogenic protein, induces proteases in rodent hepatocytes through NF-kappaB. J Hepatol. 2007;47:834–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bilzer M, Roggel F, Gerbes AL. Role of Kupffer cells in host defense and liver disease. Liver Int. 2006;26:1175–1186. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramadori G, Armbrust T. Cytokines in the liver. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:777–784. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack DM, et al. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004;430:213–218. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brun P, Castagliuolo I, Di Leo V, et al. Increased intestinal permeability in obese mice: new evidence in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G518–G525. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00024.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu WC, Zhao W, Li S. Small intestinal bacteria overgrowth decreases small intestinal motility in the NASH rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:313–317. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miele L, Valenza V, La Torre G, et al. Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:1877–1887. doi: 10.1002/hep.22848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farhadi A, Gundlapalli S, Shaikh M, et al. Susceptibility to gut leakiness: a possible mechanism for endotoxaemia in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Int. 2008;28:1026–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isoda K, Sawada S, Ayaori M, et al. Deficiency of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist deteriorates fatty liver and cholesterol metabolism in hypercholesterolemic mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7002–7009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nozaki Y, Saibara T, Nemoto Y, et al. Polymorphisms of interleukin-1 beta and beta 3-adrenergic receptor in Japanese patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(8 suppl proc):106S–110S. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2004.tb03226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parsons CJ, Bradford BU, Pan CQ, et al. Antifibrotic effects of a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 antibody on established liver fibrosis in rats. Hepatology. 2004;40:1106–1115. doi: 10.1002/hep.20425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Miyamoto Y, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 promotes liver fibrosis development in a transgenic mouse model. Hepatology. 2000;32:1248–1254. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.20521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Yoshii J, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metal-loproteinases-1 attenuates spontaneous liver fibrosis resolution in the transgenic mouse. Hepatology. 2002;36:850–860. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.35625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dalpke AH, Lehner MD, Hartung T, et al. Differential effects of CpG-DNA in Toll-like receptor-2/-4/-9 tolerance and cross-tolerance. Immunology. 2005;116:203–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Nardo D, De Nardo CM, Nguyen T, et al. Signaling crosstalk during sequential TLR4 and TLR9 activation amplifies the inflammatory response of mouse macrophages. J Immunol. 2009;183:8110–8118. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seki E, Tsutsui H, Nakano H, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-18 secretion from murine Kupffer cells independently of myeloid differentiation factor 88 that is critically involved in induction of production of IL-12 and IL-1beta. J Immunol. 2001;166:2651–2657. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imamura M, Tsutsui H, Yasuda K, et al. Contribution of TIR domain-containing adapter inducing IFN-beta-mediated IL-18 release to LPS-induced liver injury in mice. J Hepatol. 2009;51:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inokuchi S, Aoyama T, Miura K, et al. Disruption of TAK1 in hepatocytes causes hepatic injury, inflammation, fibrosis, and carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:844–849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909781107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chitturi S, Abeygunasekera S, Farrell GC, et al. NASH and insulin resistance: insulin hypersecretion and specific association with the insulin resistance syndrome. Hepatology. 2002;35:373–379. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chitturi S, Farrell G, Frost L, et al. Serum leptin in NASH correlates with hepatic steatosis but not fibrosis: a manifestation of lipotoxicity? Hepatology. 2002;36:403–409. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fartoux L, Chazouilleres O, Wendum D, et al. Impact of steatosis on progression of fibrosis in patients with mild hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:82–87. doi: 10.1002/hep.20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camma C, Bruno S, Di Marco V, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with steatosis in nondiabetic patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2006;43:64–71. doi: 10.1002/hep.20983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ota T, Takamura T, Kurita S, et al. Insulin resistance accelerates a dietary rat model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:282–293. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakurai M, Takamura T, Ota T, et al. Liver steatosis, but not fibrosis, is associated with insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:312–317. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1948-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1461–1465. doi: 10.1038/ng.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kantartzis K, Peter A, Machicao F, et al. Dissociation between fatty liver and insulin resistance in humans carrying a variant of the patatin-like phospholipase 3 gene. Diabetes. 2009;58:2616–2623. doi: 10.2337/db09-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He S, McPhaul C, Li JZ, et al. A sequence variation (I148M) in PNPLA3 associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease disrupts triglyceride hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6706–6715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valenti L, Al-Serri A, Daly AK, et al. Homozygosity for the patatin-like phospholipase-3/adiponutrin I148M polymorphism influences liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:1209–1217. doi: 10.1002/hep.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anstee QM, Goldin RD. Mouse models in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and steatohepatitis research. Int J Exp Pathol. 2006;87:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2006.00465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.