Anal Intercourse among Young Heterosexuals in Three US STD Clinics (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2016 Sep 12.

Abstract

Background

To examine factors associated with heterosexual anal intercourse (AI).

Methods

Between 2001 and 2004, 890 heterosexual adults aged 18-26 attending public STD clinics in Seattle, New Orleans and St Louis were interviewed using CASI and tested for sexually transmitted infections (STI) Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Mycoplasma genitalium, Trichomonas vaginalis, and genital herpes (HSV-2). Characteristics associated with AI were identified using logistic regression.

Results

Overall 289 (32%) reported ever having had AI, 201 (26.5%) reported AI with at least one of their last three partners and 17% reported AI with their last partner. Fewer females than males reported condom use at last AI (24% vs. 47%, p<0.001). Ever having AI was associated with sex on the same day as meeting a partner (AOR 3.5 [95% CI 1.94-6.15]), receiving money for sex (AOR 3.3 [1.40-7.75]), and >3 lifetime sex partners (AOR 2.2 [1.17-4.26]) among women, and sex on the same day as meeting a partner (AOR 2.0 [1.28-3.14]) and paying for sex (AOR 1.8 [1.00-3.15]) among men. AI with the last partner was associated with sex toy use (AOR 5.3 [2.35-12.0]) and having concurrent partners (AOR 2.3 [1.18-4.26]) among men, and with sex within a week of meeting (AOR 2.7 [1.21-5.83]), believing the partner was concurrent (AOR 2.6 [1.38-4.83]), and partnership duration >3 months (AOR 3.2 [1.03-10.1]) among women. Prevalent STI was not associated with AI.

Conclusions

Many young heterosexuals attending STD clinics reported AI, which was associated with other sexual risk behaviors, suggesting a confluence of risks for HIV infection.

Keywords: Heterosexual Anal intercourse, STDs, Young Adults, Sexual Partnerships

INTRODUCTION

Men who have sex with men (MSM) represent a minority of the U.S. male population (estimated at 2.3%1 to 13%2) and most (95%) report having engaged in anal intercourse (AI)3. Less is known about this practice among heterosexuals,1, 4 although prevalence estimates range between 10% and 35% for heterosexual women in the US and UK1, 2, 5, 6 and as high as 40% of US males report AI with a female partner1. In absolute numbers, seven times more U.S. heterosexual women than homosexual men engage in AI4. In heterosexual samples, reported AI has ranged from 23% of “non-virgin” university students7 to 32% of sexually active women at high risk of HIV in the previous 6 months8 and as relatively frequent with 7% of sexually active respondents reporting AI at least once a month during the previous year in a household survey,.9

Heterosexual AI has been associated with increased HIV transmission within serodiscordant couples in the US10 and Brazil11 and with prevalent HIV infection among men and women attending STD clinics in India12. This increased risk is likely due to greater efficiency of transmission and low frequency of condom use during AI. The estimated unadjusted probability of transmitting HIV is 0.08 per contact for receptive anal intercourse13, as compared to 0.001 per coital act for vaginal intercourse14. Associations between AI and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) 11 other than HIV are less consistent. AI has been associated with gonorrhea in the general population but not in STD clinic patients15. Among women, AI has been significantly associated with abnormal anal cytology,16, 17 yet little data exist on rectal carriage of other STI pathogens, largely because female ano-rectal sites are rarely tested.

There are few data on factors that may influence the practice of AI among heterosexuals or whether AI places them at higher risk for STIs. Such data could help guide interventions to reduce heterosexual HIV transmission via AI, and perhaps clarify whether rectal microbicides for STI prevention among heterosexuals are needed. Therefore, we assessed individual and partnership characteristics associated with AI among young heterosexual individuals attending three geographically distinct US STD clinics.

METHODS

Study Population

Between November 2001 and May 2004, 1,220 adults ages 18-26 recruited from waiting rooms in public STD clinics in Seattle, WA, (n=605), New Orleans, LA (n=367) and St Louis, MO (n=248) were interviewed and tested for STIs in the Young Adults, Partnerships, and STD Study. Eligibility criteria included presenting with a “new problem” consisting of symptoms of STI, or sexual contact with someone with STI. IRBs at the University of Washington, Washington University at St. Louis, and Louisiana State University approved all study procedures and approval for data analysis was received from the University of California, Los Angeles IRB.

Survey Instrument

All study subjects participated in a combination of interviewer- and computer-assisted self interview (CASI) lasting approximately one hour, which included questions from Wave III of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Heath (Add Health)18 as well as more detailed sexual behavior questions. The CASI interview posed questions about the participant's three most recent romantic and sexual partners, characteristics of these partnerships, sexual experiences, history of and exposure to STI, involvement with the criminal justice system, and substance use. All participants also underwent routine clinical examination with STI screening. Analyses focus on ever having practiced AI and AI with each of the past three partners. Because few participants reported on more than one partner, our detailed analyses focused on AI reported with the most recent partnership.

Clinical and Laboratory Methods

Clinicians posed questions on sexual history and symptoms and performed an external genital (men and women) and speculum (women) exam. Men provided a urine specimen and/or urethral swab, while women provided a urine specimen and/or cervical swab, and a self-obtained vaginal swab for STI testing. Mycoplasma genitalium was detected by PCR and transcription mediated assay (TMA) and Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae were detected using culture or nucleic acid amplification tests, as previously described 19-21. Suspected genital herpes (HSV-2) infection was confirmed by viral culture and Trichomonas vaginalis was diagnosed by wet-mount microscopy. “Any STI” was defined as a positive test for any of these pathogens.

Statistical methods

In univariate analyses, categorical variables were assessed using Fisher's Exact or Pearson's chi squared test, while continuous variables were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify factors independently associated with the practice of AI, defined in one model as ever having engaged in the practice and in another as having practiced AI with the most recent sex partner. Variables that were associated with STI or AI at p≤0.05 in univariate analyses were selected for testing in multivariate models and retained if p≤0.05. All univariate and multivariate analyses were stratified by city using the svy function in Stata version 8.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and separate models were developed for men and women.

RESULTS

Demographic, sexual behavior, and partnership characteristics

Of the 1,220 young adults enrolled, we analyzed data from 890 individuals who self-identified as “100% heterosexual” with no reported same-sex partners, excluding 300 who reported they had any attraction to members of the same sex and 30 who reported a same sex partner as one of their previous three partners. Among these 890 heterosexuals, 34.5% were from New Orleans, 23.7% from St. Louis, and 41.8% from Seattle. Most were male (63.8%); 20.6% were non-Hispanic (NH) white, 67.8% NH black, and 5.3% Hispanic. The overall median lifetime number of partners was 8, but males reported significantly more partners than females (10 vs. 5, p<0.01). Similarly, the median number of partners during the past year was higher for males than for females (3 vs. 2, p<0.01). Participants reported a median of 4 sex acts during the past month. At least one STI (“any STI”) was detected in 289/890 (32%) persons.

Many participants reported a current partner (43.5%) and 758 provided detailed information on their most recent partner. Of these, 18% reported an age difference of 5 years or more; more common females (29.1%) than males (11.1%), (p<0.001). An exclusive partner was reported by 232 (60%), 68 (17.6%) reported a non-exclusive dating relationship, 40 (10.3%) characterized the partnership as dating infrequently, and 47 (12.1%) said the relationship was only for sex. Among females, 61% reported initiating sex equally, 11% said she initiated sex more; and 28% said the male partner initiated sex. A similar proportion of males (57%) reported initiating sex equally; 31% said that he initiated sex; and 12% said their female partner initiated sex. Overall, 103/480 (21.5%) reported having experienced physical abuse from their most recent partner (i.e., said ‘yes’ to the question “your partner slapped, hit, or kicked you”), and 57/479 (11.9%) reported being forced to have sex (i.e., said ‘yes’ to the question “your partner insisted on or made you have sex when you didn't want to”). More males reported physical abuse (26.8%, 73/272) than females (14.4%, 30/208, p<0.001). Similar percents of males reported being forced to have sex as females (13.2% vs. 10.2%, respectively). Physical abuse and forced sex in the last partnership were significantly associated with reported AI with last partner in men but not women.

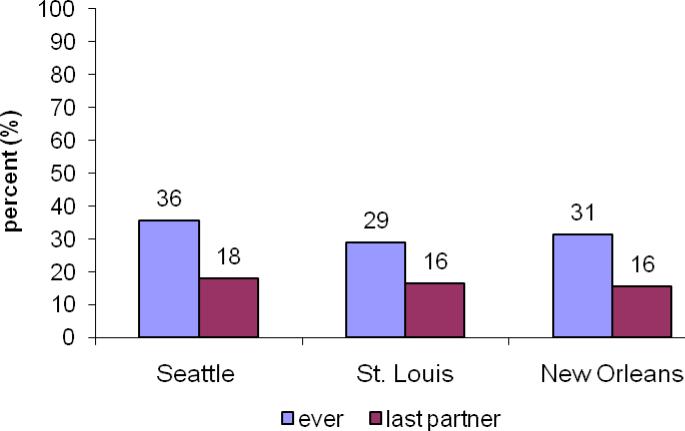

Prevalence of anal intercourse

Overall 289 (32%) reported ever practicing AI; this did not differ significantly by gender or city (Fig. 1). Of those who reported AI, 39% (n=111) reported condom use during last AI, but fewer females (24%) than males (47%) (p<0.001). AI with at least one of the last 3 partners was reported by 201 (26.5%); AI with the last partner was reported by 15.1% of males and 19.7% of females (p= 0.1). Overall, the proportion engaging in AI increased steadily with age, going from 22% among 18 year olds to 44% of 25 year olds (ptrend<0.001).

Figure 1.

Percent reporting anal sex intercourse ever and with last partner, by city

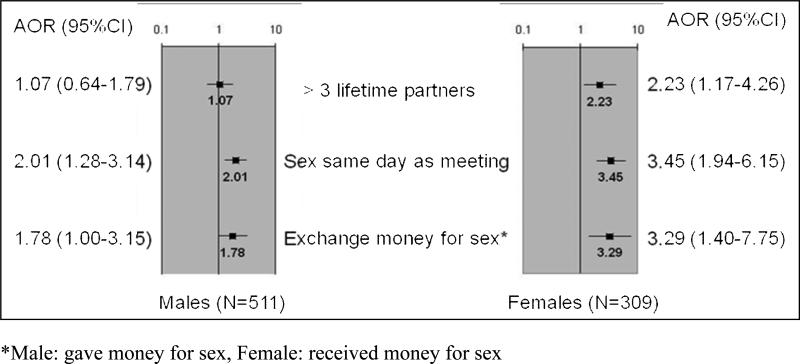

Factors associated with ever practicing anal intercourse

In univariate analyses, fewer who reported AI reported condom use at last vaginal sex than among those who did not practice AI (44.7% vs. 51.5%, p=0.09). Having more lifetime partners, sex the same day as meeting a partner, and ever exchanging sex for money were significantly more common among those who had ever practiced AI (Table 1). In separate unadjusted logistic regression models for males and females stratified by city, having had sex on the same day as meeting a partner was associated with ever engaging in AI both for men (Odds Ratio (OR) 2.2 [95% CI 1.48-3.32]) and women (OR 4.8 [2.83-8.05]). Ever having paid for sex was associated with ever engaging in AI for men (OR 1.9 [1.16-3.26]), while ever having received money for sex (OR 6.5 [2.96-14.1]) or having greater than 3 lifetime partners (OR 3.4 [1.82-6.23]) were associated with ever engaging in AI for women. Individuals who had ever engaged in AI were somewhat more likely, albeit not significantly, to report a history of any STI (62% vs. 57%), but not more likely to have laboratory-diagnosed STI at study enrollment. History of injection drug use was not associated with ever AI for men or women.

Separate multivariate analyses stratified by city were conducted for ever having practiced AI for men and women. Women who had sex on the same day they met a partner (AOR 3.5; 95% CI 1.94-6.15), ever received money for sex (AOR 3.3; 95% CI 1.40-7.75), and who reported greater than 3 lifetime sex partners (AOR 2.2; 95% CI 1.17-4.26) were significantly more likely to report ever engaging in AI (Figure 2). Men who reported having sex on the same day they met a partner (AOR 2.0; 95% CI 1.28-3.14) and ever having paid for sex (AOR 1.8, 95% CI 1.00-3.15) were significantly more likely to report ever having AI.

Figure 2.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses, stratified by city, of ever having anal intercourse by gender: associated characteristics and behaviors

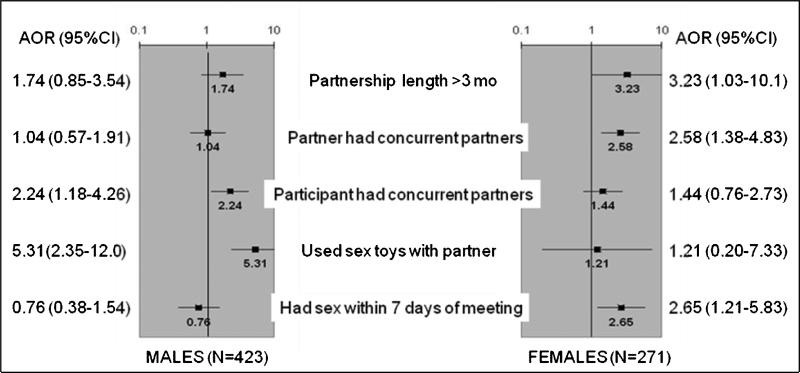

Factors associated with engaging in anal intercourse with the most recent partner

Of the 758 individuals who provided detailed information on their most recent partner, almost half reported having had AI more than one time with that partner. Among these, 40% (n=51) reported they had ever used a condom for AI (32% of females and 46% of males, p=0.09). In univariate logistic regression analysis stratified by city, men who reported having a partnership lasting longer than 3 months (OR 2.29 [1.18-4.41]), using sex toys (OR 6.33 [2.89-13.9]), and having concurrent partners (OR 2.73 [1.55-4.85]) were more likely to report AI with their most recent partner. Among women, AI with the most recent partner was associated with a partnership of longer than 3 months duration (OR 3.66 [1.26-10.7]), having vaginal sex within the first seven days of the partnership (OR 2.33 [1.12-4.81]), and believing that the partner had other concurrent partners (OR 3.07 [1.67-5.64]). Whether the last partnership was exclusive or casual was not associated with engaging in AI within that partnership, nor was laboratory diagnosed STI.

In multivariate logistic regression analysis stratified by site, men who reported sex toy use (AOR 5.3 [2.35-12.0]) and having concurrent partners (AOR 2.3 [1.18-4.26]) in the partnership were more likely to report AI with the most recent partner. For women, having sex within the first 7 days of meeting that partner (AOR 2.7 [1.21-5.83]), believing that partner had concurrent partners (AOR 2.6 [1.38-4.83]), and partnership duration longer than 3 months (AOR 3.2 [1.03-10.1]) were associated with AI in that partnership (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses, stratified by city, of having anal intercourse with last partner by gender: associated characteristics and behaviors

To consider whether these young adults were having AI instead of vaginal intercourse to preserve their “virginity” we examined AI among those who reported they had never had vaginal intercourse. Of the 11 women who reported never having had vaginal sex, two (18%) reported ever engaging in AI and three (27%) reported AI with at least one of the past 3 romantic partners. Of the 42 heterosexual men who reported never having vaginal intercourse, five (12%) reported ever having AI, and seven (17%) reported AI with at least one of the last three partners. Male “virgins” were significantly less likely to have had AI than men who had ever had vaginal intercourse (12% vs 34%, p=0.003). Similarly, women who were “virgins” were somewhat less likely to have had AI than women who reported having had vaginal intercourse (18% vs 33%, p=0.30).

DISCUSSION

Anal intercourse was common among these heterosexual young adults attending STD clinics in all three of the cities studied. Condom use during AI was low and less common than it was during vaginal intercourse. Moreover, the young adults who practiced AI had riskier sexual behavior in general than other young adults. AI was associated with selling/trading sex, having sex with new acquaintances, having concurrent partners, and engaging in other less traditional sexual behaviors such using sex toys. These associations suggest that those who practice AI have an expanded sexual repertoire.

While we did not see an association with drug use in our study, other studies suggest that drug users are more likely to practice AI than non drug users, particularly methamphetamine users**22, 23.** We did however; see an association of ever engaging in AI with exchange of sex for money. While it is not clear if AI is practiced itself for money, it is clearly associated with engagement in commercial sex during which women may engage in sexual practices in response to requests by others. Additionally, both men and women who practiced AI were more likely to have sex with partners they did not know well (i.e., within the same day or week of meeting). Other studies have noted similar associations of AI with trading sex for money as well as sex with an IDU among young women in non-STD clinic populations**24.** Finally, although other studies have noted differences by ethnicity,25 neither the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG)1 nor our study noted differences in this practice by ethnicity.

Almost one third of participants in our study reported ever engaging in AI and this was a young group, suggesting that lifetime rates will be higher among these STD clinic attendees as they age. Moreover, the high prevalence of this behavior among these young adults suggests an early initiation of this behavior. Our lifetime prevalence of ever practicing AI closely matches that reported in the NSFG (30% of women and 34% of men) which included a much wider age range of 18-44 years of age1. In contrast, AI was reported by only 11% of males 15-19 years old in the 1995 National Survey of Adolescent Males26, and by 21.7% of sexually active women 18-29 years in a population based study in low-income neighborhoods in Northern California24. Despite the different age ranges and sampling frames for these studies, the higher proportion of our young STD patients reporting AI relative to the general population samples of young adults is consistent with previous observations that STD clinic attendees engage in more high risk behaviors.

We found little evidence that AI was being used to maintain “virginity” as very few virgins reported AI. However, there were few “virgins” attending these STD clinics and there may more young adults in the general population who use AI to maintain virginity. Nevertheless, loss of virginity has been linked primarily with vaginal and anal intercourse27; thus, it is unlikely that AI is used as much as oral sex to maintain virginity. This suggests that reasons for engaging in AI are more likely social, partnership, and/or physical, rather than to maintain virginity.

Our analyses of AI with the last partner provide unique insight into how AI occurs in partnerships. Unlike other studies24 although AI was not associated with the type of partners (i.e., exclusive or casual) it occurred more often in partnerships of longer duration, suggesting that individuals may experiment more as trust and intimacy evolves in partnerships over time. However, AI was also more common in partnerships where there was concurrency. Thus AI may also be practiced in partnerships that are unstable; sexual experimentation may be used to sustain partnerships. The fact that AI was reported more by women who believed their partners had concurrent partnerships and more by males who themselves had concurrent partnerships, lends support to this possibility. Moreover, although the partnerships with AI were of longer duration, these were also partnerships in which sex was initiated quickly (within 7 days). Other studies have noted that AI was reported more often by those engaging in experimental sexual activities such as bisexuality28. Although our study population was restricted to heterosexuals, in exploratory analyses among the 127 excluded bisexual men, we found that they practiced AI more with their female partners (20%) and in more of their partnerships (42%) than did men who only had sex with women (13%). However, our numbers of bisexual men were too small for more detailed analyses of this issue, warranting further study.

The relatively high proportion of young adults reporting AI raises concerns about increased risk for acquisition and transmission of STIs including HIV among young adults. The practice itself appears to be increasing; the proportion of a random sample of Seattle residents who reported AI increased from 4.3% in 1995 to 8.3% in 2004.30 Although we found no association of AI with a combined indicator of having any of several STIs, we did not test participants for anorectal STI, thus we likely missed cases. The risk for HIV acquisition or transmission via AI is compounded by infrequent condom use during AI, exposure to many partners, exposure to risky partners (including commercial and concurrent partners), and quick initiation of sex after meeting a partner among those practicing AI. These observations suggest that individuals who practice AI may be bridging sexual networks and further increasing the likelihood they will be exposed to or will transmit HIV and highlights the need for broad behavioral counseling for young adults, particularly those seen in STD clinics, about the risks of HIV transmission/acquisition during AI. In our study, condom use with AI was reported by less than half of participants, and fewer women. HIV prevention programs should address the practice of anal intercourse with young heterosexuals and encourage condom use to reduce their risk of HIV infection, especially for women where AI has been associated with HIV infection29.

Table 1.

Characteristics & behaviors among young adults reporting AI

| AI Ever | AI with last partner | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YESNo. (%) | NONo. (%) | YESNo. (%) | NONo. (%) | |

| Males | N = 184 | N = 382 | N = 71 | N = 398 |

| Age (years)+ | 22 [18-26] | 21 [18-26] | 21 [18-25] | 21 [18-26] |

| Race/ethnicity: NH† White | 45 (24.6) | 75 (19.9) | 20 (28.2) | 94 (23.9) |

| NH† Black | 124 (67.8) | 268 (71.1) | 43 (60.6) | 263 (66.8) |

| NH† Other | 6 (3.3) | 15 (4.0) | 3 (4.2) | 16 (4.1) |

| Hispanic | 8 (4.4) | 19 (5.0) | 5 (7.0) | 21 (5.3) |

| Site: | ||||

| Seattle | 73 (39.7) | 144 (37.7) | 35 (49.3) | 163 (41.0) |

| St. Louis | 41 (22.3) | 104 (27.2) | 19 (26.8) | 104 (26.1) |

| New Orleans | 70 (38.0) | 134 (35.1) | 17 (23.9) | 131 (32.9) |

| Total number of sex partners+** | 13.5 [1-300] | 9 [1-185] | ||

| >3 lifetime partners** | 149 (85) | 267 (79) | ||

| Ever paid for sex** | 31 (16.9) | 36 (9.5) | ||

| Sex with partner same day met** | 143 (77.7) | 233 (61.2) | ||

| Reported a history of STI∥ | 109 (59.2) | 199 (52.1) | 44 (62.0) | 213 (53.5) |

| Current laboratory-diagnosed STI§ | 61 (33.2) | 130 (34.0) | 22 (31.0) | 126 (31.7) |

| Age discordant ≥5 years* | 14 (19.7) | 38 (9.6) | ||

| Partnership length >3 months* | 59 (83.1) | 271 (68.3) | ||

| Sex within first 7 days of meeting | 13 (18.8) | 94 (24.9) | ||

| Used sex toys with partner** | 14 (20.0) | 15 (3.8) | ||

| Believe partner has other partners | 22 (31.4) | 91 (24.0) | ||

| Have concurrent partners** | 52 (74.3) | 201 (51.4) |

| Females | N = 105 | N = 217 | N = 57 | N = 232 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)+ | 22 [18-25] | 21 [18-25] | 22 [18-25] | 21 [18-25] |

| Race/ethnicity: NH† White | 24 (23.1) | 38 (17.5) | 10 (17.4) | 52 (22.5) |

| NH† Black | 59 (56.7) | 146 (67.3) | 36 (63.2) | 140 (60.6) |

| NH† Other | 12 (11.5) | 22 (10.1) | 5 (8.8) | 28 (12.1) |

| Hispanic | 9 (8.7) | 11 (5.1) | 6 (10.5) | 11 (4.8) |

| Site: | ||||

| Seattle | 59 (56.2) | 94 (43.3) | 27 (47.4) | 117 (50.4) |

| St. Louis | 20 (19.1) | 46 (21.2) | 11 (19.3) | 49 (21.1) |

| New Orleans | 26 (24.8) | 77 (35.5) | 19 (33.3) | 66 (28.5) |

| Total number of sex partners+** | 10.5 [1-300] | 5 [1-750] | ||

| >3 lifetime partners** | 87 (85) | 131 (63) | ||

| Ever received money for sex** | 25 (23.8) | 10 (4.6) | ||

| Sex with partner same day met** | 52 (49.5) | 37 (17.1) | ||

| Reported a history of STI∥ | 71 (67.6) | 143 (65.9) | 37 (64.9) | 150 (64.7) |

| Current laboratory-diagnosed STI§ | 30 (28.6) | 67 (30.9) | 19 (33.3) | 71 (30.6) |

| Age discordant ≥5 years | 18 (32.1) | 66 (28.5) | ||

| Partnership length >3 months* | 53 (93.0) | 181 (78.4) | ||

| Sex within first 7 days of meeting* | 14 (24.6) | 28 (12.3) | ||

| Used sex toys with partner | 2 (3.5) | 6 (2.6) | ||

| Believe partner has other partners** | 34 (60.7) | 75 (33.5) | ||

| Have concurrent partners* | 33 (58.9) | 101 (44.1) |

SUMMARY.

Many young adult STD clinic patients in three US cities reported anal intercourse ever and in last partnership; this was associated with other high risk sexual behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the UW STD CRC (NIH/NIAID AI31448).

REFERENCES

- 1.Mosher WD, Chandra A, Jones J. Sexual behavior and selected health measures: men and women 15-44 years of age, United States. Adv Data. 2002;2005:1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Attar SM, Evans DV. Anal warts, sexually transmitted diseases, and anorectal conditions associated with human immunodeficiency virus. Prim Care. 1999;26:81–100. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross M, Buchbinder SP, Celum C, 3rd., et al. Rectal microbicides for U.S. gay men. Are clinical trials needed? Are they feasible? HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study Protocol Team. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:296–302. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halperin DT. Heterosexual anal intercourse: prevalence, cultural factors, and HIV infection and other health risks, Part I. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 1999;13:717–30. doi: 10.1089/apc.1999.13.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans BA, Bond RA, Macrae KD. Sexual behaviour in women attending a genitourinary medicine clinic. Genitourin Med. 1988;64:43–8. doi: 10.1136/sti.64.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strang J, Powis B, Griffiths P, et al. Heterosexual vaginal and anal intercourse amongst London heroin and cocaine users. Int J STD AIDS. 1994;5:133–6. doi: 10.1177/095646249400500211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin JI, Baldwin JD. Heterosexual anal intercourse: an understudied, high-risk sexual behavior. Arch Sex Behav. 2000;29:357–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1001918504344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross M, Holte SE, Marmor M, et al. Anal sex among HIV-seronegative women at high risk of HIV exposure. The HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study 2 Protocol Team. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:393–8. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200008010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson PI, Bastani R, Maxwell AE, et al. Prevalence of anal sex among heterosexuals in California and its relationship to other AIDS risk behaviors. AIDS Educ Prev. 1995;7:477–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skurnick JH, Kennedy CA, Perez G, et al. Behavioral and demographic risk factors for transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in heterosexual couples: report from the Heterosexual HIV Transmission Study. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:855–64. doi: 10.1086/513929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guimaraes MD, Munoz A, Boschi-Pinto C, et al. HIV infection among female partners of seropositive men in Brazil. Rio de Janeiro Heterosexual Study Group. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:538–47. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodrigues JJ, Mehendale SM, Shepherd ME, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection in people attending clinics for sexually transmitted diseases in India. Bmj. 1995;311:283–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vittinghoff E, Douglas J, Judson F, et al. Per-contact risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission between male sexual partners. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:306–11. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Brookmeyer R, et al. Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 2001;357:1149–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manhart LE, Aral SO, Holmes KK, et al. Influence of study population on the identification of risk factors for sexually transmitted diseases using a case-control design: the example of gonorrhea. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:393–402. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moscicki AB, Hills NK, Shiboski S, et al. Risk factors for abnormal anal cytology in young heterosexual women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:173–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holly EA, Ralston ML, Darragh TM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for anal squamous intraepithelial lesions in women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:843–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), Waves I & II, 1994–1996; Wave III, 2001–2002 [machine-readable data file and documentation] Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Chapel Hill, NC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutro SM, Hebb JK, Garin CA, et al. Development and performance of a microwell-plate-based polymerase chain reaction assay for Mycoplasma genitalium. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:756–63. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000078821.27933.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wroblewski JK, Manhart LE, Dickey KA, et al. Comparison of transcription-mediated amplification and PCR assay results for various genital specimen types for detection of Mycoplasma genitalium. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3306–12. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00553-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson SJ, Manhart LE, Gorbach PM, et al. Measuring sex partner concurrency: it's what's missing that counts. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:801–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318063c734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zule WA, Costenbader EC, Meyer WJ, et al. Methamphetamine use and risky sexual behaviors during heterosexual encounters. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:689–94. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000260949.35304.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(CDC) CfDCaP Methamphetamine use and HIV risk behaviors among heterosexual men - Preliminary results from five northern California counties, December 2001-November 2003. MMWR. 2006;55:273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misegades L, Page-Shafer K, Halperin D, et al. Anal intercourse among young low-income women in California: an overlooked risk factor for HIV? Aids. 2001;15:534–5. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200103090-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norris AE, Ford K, Shyr Y, et al. Heterosexual experiences and partnerships of urban, low-income African-American and Hispanic youth. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;11:288–300. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199603010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gates GJ, Sonenstein FL. Heterosexual genital sexual activity among adolescent males: 1988 and 1995. Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32:295–7. 304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bersamin MM, Fisher DA, Walker S, et al. Defining virginity and abstinence: adolescents' interpretations of sexual behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:182–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foxman B, Aral SO, Holmes KK. Heterosexual repertoire is associated with same-sex experience. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:232–6. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199805000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chirgwin KD, Feldman J, Dehovitz JA, et al. Incidence and risk factors for heterosexually acquired HIV in an inner-city cohort of women: temporal association with pregnancy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;20:295–9. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199903010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]