Informed choice in bowel cancer screening: a qualitative study to explore how adults with lower education use decision aids (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background Offering informed choice in screening is increasingly advocated, but little is known about how evidence‐based information about the benefits and harms of screening influences understanding and participation in screening.

Objective We aimed to explore how a bowel cancer screening decision aid influenced decision making and screening behaviour among adults with lower education and literacy.

Methods Twenty‐one men and women aged 55–64 years with lower education levels were interviewed about using a decision aid to make their screening decision. Participants were purposively selected to include those who had and had not made an informed choice.

Results Understanding the purpose of the decision aid was an important factor in whether participants made an informed choice about screening. Participants varied in how they understood and integrated quantitative risk information about the benefits and harms of screening into their decision making; some read it carefully and used it to justify their screening decision, whereas others dismissed it because they were sceptical of it or lacked confidence in their own numeracy ability. Participants’ prior knowledge and beliefs about screening influenced how they made sense of the information.

Discussion and conclusions Participants valued information that offered them a choice in a non‐directive way, but were concerned that it would deter people from screening. Healthcare providers need to be aware that people respond to screening information in diverse ways involving a range of literacy skills and cognitive processes.

Keywords: decision aid, decision‐making, bowel cancer screening, faecal occult blood test, health literacy, informed choice, qualitative study

Introduction

Patient decision aids have shown to be effective in helping people make informed choices about their health by incorporating balanced information on the benefits and the harms of healthcare options, together with methods to clarify preferences. 1 Despite the proliferation of decision aids, few attempts have been made to develop and evaluate their use among lower education and literacy groups. We developed a decision aid for adults with lower education and literacy that were considering bowel cancer screening using the faecal occult blood test (FOBT) and evaluated it in a randomized controlled trial (RCT). 2 , 3 , 4 The decision aid contained tailored risk information comparing the outcomes of screening and no screening for different gender and family history groups. Results from the trial showed that participants who received the decision aid were more likely to make an informed choice about screening compared to those in a control group who received the standard government screening information. However, decision aid participants were less positive about doing the test and less likely to complete it. 4 This is one of the first decision aid trials to show a reduction in bowel cancer screening participation. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10

The trial generated a debate about the use of decision aids in facilitating informed choice about screening. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 One editorial suggested that policy should be focused on supporting ‘informed uptake rather than informed decision‐making’. 12 Others argued for the provision of transparent screening information about the benefits and harms. It was apparent from these discussions that little was known about the process of making screening decisions with the use of a decision aid. Screening providers need to be aware of how people may respond to and act on information about the benefits and harms of participating in bowel screening.

Faecal occult blood testing is currently offered or will soon be introduced, through government funded programmes in several countries, with FOBT kits and written consumer information directly mailed to eligible participants. 15 , 16 , 17 FOBT screening may also be opportunistic where a person requests or is offered screening by a doctor; FOBT kits are also available in the community (e.g. from pharmacists) outside of clinical settings.

Deciding whether to participate in FOBT screening can be described as a preference sensitive decision. The likelihood of personally experiencing a benefit (reduced mortality) from participating in FOBT screening is relatively small compared with the likelihood of experiencing harms (false positives and false negatives). 18 Thus, the ‘best’ choice will depend on how patients value the benefits and harms of each option (screening versus no screening). However, public understanding about the benefits and harms of cancer screening is limited. 19 Supporting informed choices in screening using decision aids could help people understand the benefits and harms of participating. 20 This study provided an opportunity to understand how people with lower education use evidence‐based information to make screening decisions. It reports the findings from a qualitative follow‐up study with trial participants, to examine how the FOBT decision aid influenced decision making and screening behaviour.

Methods

Participant recruitment

Semi‐structured interviews were carried out with 21 participants from the decision aid arm of the RCT. Purposive sampling (a technique in which participants are selected because they have particular features or characteristics that will enable detailed exploration of the research aims) was used to ensure the sample included a mixture of men and women with limited and adequate functional health literacy, who had/had not made an informed choice, and had/had not completed the FOBT as determined from laboratory records (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of decision aid participants

| Decision aid participants (n = 21) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 12 |

| Female | 9 |

| Year of full‐time education | |

| 6–10 | 13 |

| 11–15 | 8 |

| Educational qualifications | |

| Intermediate school certificate* | 14 |

| Technical/trade certificate† | 8 |

| Functional health literacy‡,§ | |

| High likelihood of limited literacy | 4 |

| Possibility of limited literacy | 5 |

| Adequate literacy | 11 |

| Informed choice** | |

| To screen | |

| Male | 3 |

| Female | 3 |

| To not screen | |

| Male | 3 |

| Female | 2 |

| Uninformed choice†† | |

| To screen | |

| Male | 3 |

| Female | 1 |

| To not screen | |

| Male | 3 |

| Female | 3 |

We assessed participants’ functional health literacy using the Newest Vital Sign, a 6‐item measure that requires people to locate and extract information (reading and comprehension skills), calculate percentages (numeracy skills) and use abstract reasoning skills. 21 All participants were aged between 55 and 64 years, were living in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas in New South Wales, Australia, and had low educational attainment; 14 had an intermediate school certificate (awarded for completion of 4 years of high school or secondary school), and eight had a technical trade certificate (roughly equivalent to adults with a national vocational qualification or an apprenticeship). Participants were considered to have made an informed choice to complete the screening test if they had adequate knowledge, positive attitudes towards the test and completed it. An informed choice to decline the screening test occurred when a participant had a negative attitude towards the test, had adequate knowledge and did not complete it. Participants who had inadequate knowledge and/or their attitudes did not reflect their screening behaviour (positive attitudes but did not complete the test or vice versa) were considered to have made an uninformed choice about screening.

Interviews were conducted by two researchers (SS and PK) in participants’ homes between November 2008 and April 2009 and structured around a topic guide (Table 2). The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim using a professional transcription service. The University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee approved this study.

Table 2.

Topic guide

| Responses to the information |

|---|

| Initial impressions of the decision aid booklet |

| Clarity of information |

| Understanding and interpretations of risk information |

| Role/aim of the booklet |

| Making the screening decision |

| Decision about the test – use of information |

| Discussion with doctor about screening |

| Involvement of family or friends in decision making |

| Further information seeking |

| Individual decision making |

| Feelings about making a decision at home without a healthcare professional |

| Attitudes towards benefits and downsides/harms to screening |

| Preferences for more/less information |

| Being given a choice about screening |

Full details of the RCT are published. 4 Briefly, participants were randomly assigned to receive a decision aid (with or without a question prompt list) or standard information (national screening programme booklet). All participants received a FOBT kit. The decision aid can be found at http://sydney.edu.au/medicine/publichealth/step/publications/decisionaids.php.

Data analysis

Data were analysed by two health psychologists (SS and KM) and a social scientist with qualifications in education (PK) using ‘Framework’, a matrix‐based method to organize the data 22 This begins deductively using a priori questions drawn from the aims and then identifies themes in an inductive manner by maintaining close links with the data. 23 The process follows five stages;

- 1

Familiarization with the data: SS, PK and KM read a sample of transcripts to familiarize themselves with the data and generate discussion about the themes. - 2

Creating a thematic framework: SS, PK and KM developed a provisional coding framework to code and index the data, based on the recurrent themes (and subthemes) observed in the data and the research questions. - 3

Indexing: PK and SS independently coded a selection of transcripts to refine the coding index. Perceived discrepancies between the data and the index were discussed and negotiated between coders through ongoing discussion on a regular basis. - 4

Charting: PK synthesized all of the data within a set of thematic matrix charts using the final coding index. Within each matrix, each participant is assigned a row, while each subtheme is allocated a separate column. - 5

Mapping and interpretation: PK, SS and KM discussed the charted data to better understand the range and diversity of issues identified and develop a typology (as described in the results) to capture the different responses to the quantitative risk information about the outcomes of screening.

Results

The findings below are organized according to the identified themes. Selected quotations are used to illustrate the findings.

Factors influencing informed and uninformed choices

Understanding the role of the decision aid seemed to be an important prerequisite for making an informed choice. Those participants who had made an informed choice about screening seemed to have a greater understanding of the purpose of the decision aid, in making people aware that the decision to screen involves weighing up the benefits and harms of screening. By contrast, those who had made an uninformed choice had greater difficulties grasping this, and thought it was encouraging screening:

So people understand exactly what is happening… so they don’t think that just because they have it [the screening test] that they gonna be detected, because that may not necessarily happen. To inform them why they should have it, but it can’t be 100%, because not all things are 100%, because there are risks involved where you can stress because you can get a false reading. But just trying to be informative and tell people exactly what is happening and how it is going to happen, and how you do it, and there are for and against.

(Participant 693, female, technical/trade certificate, limited functional health literacy, informed choice to screen)

I think it is trying to get more men to notice that you should be going for tests. Put it up front in their face and say here you are over 55 so you had better have the test.

(Participant 781, male, technical/trade certificate, adequate functional health literacy, uninformed choice to screen)

The second important difference between informed and uninformed participants related to their understanding of the risk information. Participants who had made an informed choice appeared better able to describe their perceived understanding of the risk information.

I thought it [the decision aid] would be easy for a lot of people to read and it gave you the things, like if you don’t have it [screening], if you do have it and all those different things that you could compare. It just says [Participant describing the diagrams comparing the numbers of deaths avoided with and without screening] for instance that, no bowel cancer deaths are avoided by screening [for women with no family history]. So, they’re letting you know but I just thought it was worthwhile doing it [the test] you know.

(Participant 520, female, intermediate school certificate, adequate functional health literacy, informed choice to screen)

In the next section, we consider the different ways in which participants made sense of the risk information and how it influenced decision making.

Responses to the risk information and its affect on decision making

Most decision aid participants were generally unaware before they had read the booklet of the incidence of bowel cancer and screening outcomes, such as the number of lives saved by FOBT (absolute risk reduction in bowel cancer mortality by screening), and the risk of experiencing a false‐positive or false‐negative result. Not only was this information new, it was also thought to be more personalized than previous screening information:

I thought the stats in here were very good where they said, so many in 1000 would die you know without a screening test. I thought that was very important information, and I thought the way they did the graphs was very good too … We don’t really get that information. You hear that there’s so many cancer deaths a year but you don’t know what age groups.

(Participant 693, female, technical/trade certificate, limited functional health literacy, informed choice to screen)

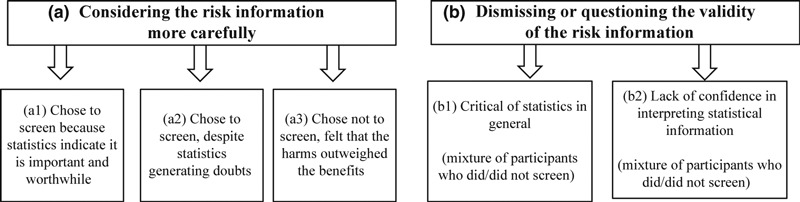

A typology was developed to capture the range of responses to the risk information (Fig. 1). We grouped participants into two broad groups: (i) those who considered the risk information more carefully, and (ii) those who dismissed or questioned the validity of the risk information. Each group is described below.

Figure 1.

Typology of responses to risk information presented in the decision aid and its affect on the screening decision.

Considering the risk information carefully

While participants in this broad category seemed to process the risk information in more detail, they varied in how they interpreted and used it in their decision making. The following subgroups explain how participants made sense of the information and justified their decision to screen or not screen.

Chose to screen because statistics indicate it is important and worthwhile: In the decision aid, the risk information shows that the absolute reduction in deaths attributable to screening is small – a few per 1000 regularly screened over 10 years (Table 3). Some participants explained that this information reinforced that screening was a ‘good thing’, even if it saves one life. One male participant described his interpretation of the risk information:

Table 3.

Summary of data presented in the decision aid: 10‐year risk of bowel cancer death for men and women aged 55–64 years

| Bowel cancer family history risk group | Without FOBT screening | With FOBT screening (every 2 years) | Bowel cancer deaths avoided |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men with no family history | 3/1000 | 2/1000 | 1/1000 |

| Men with a weak family history* | 5/1000 | 4/1000 | 1/1000 |

| Women with no family history | 2/1000 | 2/1000 | 0/1000 |

| Women with a weak family history | 4/1000 | 3/1000 | 1/1000 |

Yeah it’s quite simple, you know for every thousand men, three may die of bowel cancer – that’s without getting screened. Yeah, it just shows if you get screened, the odds of you not dying become better.

(Participant 2014, male, intermediate school certificate, adequate functional health literacy, informed choice to screen)

The same participant also reinterpreted the information in terms of relative risk rather than absolute risk: ‘if three people die without screening and two people die with screening, that’s third, you can save a third of people’.

Chose to screen, despite statistics generating doubts: For some participants, the risk information made them question whether screening was worthwhile and doubt their immediate conviction to do the test. This group integrated the new information in the context of their own beliefs that screening detects bowel cancer early and the test was relatively simple to do and non‐invasive compared with other bowel screening procedures. One male participant, who had decided to screen because he had seen others adversely affected by cancer thought he was ‘better off having it ... to get it over and find out what is going on’. At first, he ‘didn’t register with the statistics’, but later began to doubt why anyone would do the test, given that there could be so much ‘error’ with the accuracy of the result referring to the likelihood of missing bowel cancer because of a false‐negative test result.

The test is not perfect, you know, they might have missed something. And then you can turn around and say well if it is missed what is the good of having it?

(Participant 930, male, technical/trade certificate, limited functional health literacy, uninformed choice to screen)

Although the new knowledge about the fallibility of the test made him reconsider his positive views about screening and the accuracy of the test, he decided to screen anyway.

Another female participant felt that she ought to do the test, despite knowing that there was a chance that no bowel cancer deaths (in her age and family history group) would be avoided by screening. She seemed to have some difficulties reconciling her pre‐existing beliefs (in which she overestimated the mortality reduction associated with FOBT) with the new information, but eventually decided to screen on the basis that she had some bowel symptoms she was worried about. This quote illustrates how the risk information had made her question her initial decision to screen:

That was when I read that I had no family history [of bowel cancer]. That was when I thought ‘oh well maybe it’s a waste of time me doing it’, but I thought about myself and as I say the problems I’ve had since I was... and I thought, ‘No, I will do it’.

(Participant 520, female, intermediate school certificate, adequate functional health literacy, informed choice to screen)

Chose not to screen, felt that the harms outweighed the benefits: This group was similar to the previous group in that the quantitative information made them doubt their existing beliefs that screening saves many lives, however, they decided not to screen. The risk information seemed to play a pivotal role in their decision making and made them seriously consider whether screening was necessary, particularly because there was little difference in bowel cancer mortality between those who did and did not do the test:

Initially I would’ve been tempted to have the test, so I was 50/50 will I or won’t I ... So that’s the ones (participant describing risk information) who do not have screening and these are the ones who do have screening. So still the same, yeah, in other words no, there’s no difference is there? So why have the screening?

(Participant 2296, female, technical/trade certificate, adequate functional health literacy, informed choice, not screened)

Similarly, a male participant viewed the decision as weighing up the positives and negatives and did not feel that there was a sufficient reason to do the test because there was only a small reduction in the number of lives saved by screening especially for people with no family history. He described himself as an ‘educated and well read man’ and appeared confident considering the facts in detail:

I looked at it and thought that was one of the big decisions, three people out of a thousand die if you don’t have screening, two if you have screening. Genetically speaking I haven’t got a history [of bowel cancer] ... the odds of it happening to me is quite low.

(Participant 1289*, male, intermediate school certificate, informed choice, not screened)

Compared to other participants he seemed to have a better understanding of the purpose of the booklet in that it was presenting the benefits and harms of bowel screening. At the same time, however, he appeared surprised that the information was not encouraging screening, and suggested that we use a larger numerator and denominator (e.g. 20 of 10 000 rather than two of 1000) so that people will perceive the chances of developing bowel cancer as higher. He was also one of the few participants to make a GP appointment to discuss whether he should do the test. Although his GP recommended him to do the test, he decided not to because he did not envisage any personal benefit from doing it and did not have enough information. However, he had not sought additional information when we asked him.

Dismissing or questioning the validity of the risk information

Critical of statistics in general: Participants in this group were sceptical of statistical information generally, which in turn, made them question whether the risk information could provide them with a definitive answer. These participants often just wanted to know the ‘bottom line’ and were not swayed by the numeric information in their decision making; they believed there was a great deal of uncertainty in everyday life that could not be explained by statistics:

I mean it’s just the same as saying you know ‘do you think I’m going to have a fair chance of breaking my arm in the next 10 years?’ I mean okay there are statistics but, I don’t see how that can be answered by anyone. Can it? I mean you could go shopping this afternoon and get run over by a bus.

(Participant 293, female, intermediate school certificate, adequate functional health literacy, uninformed choice, not screened)

Some participants also questioned how they could apply the population‐based data (1000 oval diagrams) to their own situation. One male participant, who had made an uninformed choice not to screen, felt it was difficult to infer from the population diagrams where the individual person would ‘fit’ in. He felt there was a great deal of uncertainty in knowing whether he would be the ‘seventh or eighth one (out of 1000) ... so statistics they’re just numbers and as a human being, you might be the number, you might not be the number.’

It’s not for me’– lack of personal confidence in interpreting statistical information: This group skimmed or skipped the risk information because they either lacked confidence in their ability to understand the risk information or because they felt it was intended for people with a ‘high IQ’ compared to the ‘average person walking down the street’.

One female participant said that she had made up her mind to do the test before reading the decision aid booklet. On reading the booklet, she felt she had made the ‘right’ decision. Although she described feeling overloaded by the amount of risk diagrams and did not want to get ‘hung up’ on statistics, she did make an informed choice about screening suggesting that she had managed to understand the information.

The role of the decision aid in participants’ decision making

Some participants reported that they had made up their mind to do the test as soon as they had been recruited for the trial; consenting to participate in the trial presented an opportunity to do the test. For these participants, it seemed that the decision to screen did not require much deliberation. This view was expressed despite a clear assurance during the recruitment interview that participants were under no obligation to do the test. Other participants described having made their decision once they had received the information. Participants therefore varied in how they processed and used the information to make their decision. Some participants considered the information more carefully, helping them to justify their decision to screen or not, whereas others either questioned it or did not consciously engage with the information at all.

The decision aid was one component in participants’ decision making process; other factors influenced how participants made their decision. These included factors such as their: (i) approach to health in general (fatalistic, health conscious, importance placed on early detection), (ii) attitudes towards screening (positive/negative), (iii) own personal situation and prior experiences (e.g. family history, risk factors, presence of symptoms, normative behaviour), and (iv) prior knowledge, beliefs and (mis) understandings of cancer and screening.

Views on transparency and choice in cancer screening information

Participants often contradicted themselves when they were asked whether they had received enough information to make a decision. While they felt it was important to have all the information, hardly any participants sought additional information and some described the decision aid as too detailed. Similarly, while participants did not feel the decision to screen required much thought, they valued information that was impartial and offered them a choice, as one participant stated ‘there was never any hard sell’. On the other hand, participants were concerned that presenting information about the possible downsides of screening would ‘give them an excuse’ not to screen and appeared puzzled that the decision aid was not trying to convince people to screen:

I think it’s a good idea to even get a bit more forceful you know because the more that do it the better, just to like you know to win them over, just to get them to do it

(Participant 415, male, intermediate school certificate, limited functional health literacy, informed choice to screen)

Some participants recognized that healthcare providers were required to fully inform people about the harms of screening. Not only was information viewed as a way to inform people of the outcomes, it was also perceived as a way to protect professionals from the potential legal ramifications of not informing people adequately about the risks associated with screening/testing procedures:

I congratulate them for being honest. If you want to help people, be honest with people so they can at least make an informed decision. When you start coming in from grey areas or even untruths and something happens, they’re going to be after your blood. Now if you give them the truth and they decide not to do it, they can’t blame anybody, they can only blame themselves, that was their decision. But when you manipulate people in doing something that may not be in their best interests, but in the interests of whoever’s trying to do the manipulating, that’s not a good thing ... human beings have a right to make their own decisions – give them the truth, let them make an informed judgment and then there’s no problem afterwards.

(Participant 1289, male, intermediate school certificate, informed choice, not screened)

Discussion and conclusions

Participants varied in how they integrated the information presented in the decision aid to make their screening decision, particularly the risk information. Some processed it more carefully and made them reassess their positive attitudes about screening, creating doubts in their mind about whether they should do the test, especially when the benefits regarding reduced mortality were perceived to be so small and they had no family history. Others questioned the information because they were sceptical of it or lacked confidence in their own ability to understand it. While participants clearly appreciated honest information, they were concerned that offering people a choice and presenting the harms may reduce screening.

Using qualitative approaches alongside RCTs is increasingly recognized as a useful way to examine how interventions impact on social or behavioural processes 24 Currently, most qualitative work is carried out before the trial to develop interventions or to select outcome measures. 25 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study carried out after a trial to better understand the effects of a decision aid on decision making and behaviour among low education populations.

This study was conducted 6 months after the trial, to ensure that screening decisions were not inadvertently influenced by taking part in this interview. We observed that it took participants effort to think back to their decision making. The timing of this interview may have limited participants’ ability to recall how the information affected their decision making.

The benefits of including qualitative components in decision aid trials have been demonstrated. In one trial, interviews and non‐participant observation were used to monitor the progress of the trial and provide evidence to discontinue one trial arm because patients had difficulties completing a standard gamble values elicitation exercise to help them make decisions about treatment for atrial fibrillation. 26 Video‐ethnographic methods have also been used to better understand how decision aids influence how clinicians and patients communicate with each other. 27 In these trials, decision aids were delivered to patients directly prior to a medical consultation and were not designed for low literacy groups.

We observed that not all participants carefully considered and integrated the information about the benefits and harms of the bowel screening. This may have been because the content was too complex and overwhelming for some participants and their level of literacy was not sufficient to engage with the material. However, we note that although the decision aid was long, it was found to be highly acceptable to participants with different levels of education and functional health literacy. 4 , 28 Whether or not the length of decision aid could be reduced and remain effective is for further study. Other factors seemed to influence participants’ decision making, including their existing beliefs and experiences of cancer and screening. 29 This lends support to our previous work where we found it helpful to draw on a linguistic approach to understand how people make sense of information. 3 , 30 This approach highlights the importance of the cultural and social context and considers how prior knowledge and expectations influence text comprehension. Understanding the role of the decision aid seemed to influence whether participants grasped screening concepts and made an informed choice. 3 To improve understanding of the purpose, future decision aids could explicitly state at the outset that there is a choice to be made about screening and explain the reasons why a person may or may not choose to participate in screening.

While participants appreciated information that offered them a choice and presented unbiased information, they expressed concern that information about the harms would put people off screening. Other studies have reported similar results. A UK‐based study found that people invited to participate in screening questioned whether or not cancer incidence data and risk factor information should be removed from screening leaflets because it might deter people. 31

Similarly, interviews with stakeholders involved in the development of New Zealand’s cervical cancer prevention policy revealed that the association between sexual activity and cervical cancer was not widely publicized, through fear that linking cervical cancer to a potentially stigmatising sexually transmitted infection could reduce screening participation. 32 The authors identified two conflicting discourses –‘protectionism’ and ‘right to know’– in participants’ accounts of whether or not women should be given information about sexual risk factors for cervical cancer. The ‘protectionism’ discourse emphasizes the efficacy of screening in cancer prevention and that increasing participation in screening is in the best interests of most people. By contrast, the ‘right to know’ discourse holds that people have an absolute right to information to support informed choices about screening, even if that information discourages them from screening. The ‘right to know’ discourse reflects the key principles underpinning the goal of decision aids. In our study, participants implicitly drew on ‘protectionism’ and ‘right to know’ discourses in considering whether balanced screening information should be available.

Conclusions and implications

Despite the proliferation of decision aids in research, their use in clinical practice (e.g. community pharmacies and primary care settings) and national screening programmes is limited. 33 , 34 , 35 Nevertheless, cancer advocacy groups and medical organizations are campaigning for greater shared decision making in screening. 36 The current study, therefore, provides useful evidence on how people may respond to and act on screening information about the benefits and harms of undergoing FOBT outside of the clinical setting and has important implications for promoting patient engagement in decision making via resources such as decision aids.

Decision aid developers and healthcare providers need to be aware that some people may be sceptical of quantitative risk information presented in decision aids or have limited numeracy skills to understand it. A large proportion of the general public have limited understanding about the benefits and harms of cancer screening. 19 People with low numeracy skills are particularly vulnerable to misinterpreting statistical information, and as a result, they may find it meaningless. Previous work indicates that women with poorer numeracy skills (e.g. were unable to convert percentages to a proportion) may experience greater difficulties using risk information to estimate the benefits of mammography screening on breast cancer mortality, irrespective of whether it is framed in absolute or relative risk terms. 37 Previous efforts have been made to improve public understanding of health statistics and help people with both high and low levels of education to better interpret medical risk information. 38 However, further work is needed to examine how such educational/training resources influence decision making. It would also be useful to explore how adults with high and low numeracy skills use and understand risk information in other screening contexts.

Further research with lower education and literacy populations could also develop and test decision support tools in healthcare settings where people are generally more familiar with the idea of choosing between options and recognize that they have a choice (e.g. cancer treatment decisions). This work should seek to identify how patients with lower education and literacy skills respond to and use decision support information in other healthcare contexts, and the extent to which informed choice can be achieved in settings where the concept of informed choice is less novel or controversial.

In the current research, the ‘consider an offer’ approach to communicating about screening may have given more flexibility for participants who did not want to, or lacked confidence in their literacy and numeracy skills to engage with the information. 39 , 40 , 41 This approach allows people to respond to a screening invitation in a way that suits them best. For example, some may want to access more detailed information about the various outcomes of screening, whereas others may simply prefer to follow the recommendations of trusted healthcare providers. Further work is needed to evaluate alternative ways to support informed choice in screening among low education and literacy populations that go beyond tailoring decision aids for these groups. For example, interventions could be focused on improving gist understanding of the outcomes of participating in screening rather providing detailed statistical information. 42 This might involve developing and testing resources such as a Option Grids (one‐page sheets that present the benefits and harms of healthcare options) to help reduce the cognitive effort required to process decision aids. 43

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants who generously gave their time to be interviewed. This work was supported by a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (No 457381). The funder had no role in the design or conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in the preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

*

Functional health literacy not measured.

References

- 1.O’Connor A , Stacey D , Entwistle V et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions . Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) , 2003. ; 2 : CD001431 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith SK , Trevena L , Barratt A et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a bowel cancer screening decision aid for adults with lower literacy . Patient Education and Counseling , 2009. ; 75 : 358 – 367 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith SK , Trevena L , Nutbeam D , Barratt A , McCaffery KJ . Information needs and preferences of low and high literacy consumers for decisions about colorectal cancer screening: utilizing a linguistic model . Health Expectations , 2008. ; 11 : 123 – 136 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith SK , Trevena L , Simpson JM , Barratt A , Nutbeam D , McCaffery KJ . A decision aid to support informed choices about bowel cancer screening among adults with low education: randomised controlled trial . British Medical Journal , 2010. ; 341 : c5370 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trevena L , Irwig L , Barratt A . Randomized trial of a self‐administered decision aid for colorectal cancer screening . Journal of Medical Screening 2008. ; 15 : 76 – 82 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathieu E , Barratt A , Davey H , McGeechan K , Howard K , Houssami N . Informed choice in mammography screening: a randomized trial of a decision aid for 70‐year‐old women . Archives of Internal Medicine , 2007. ; 167 : 2039 – 2046 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf A , Schorling J . Does informed consent alter elderly patients’ preferences for colorectal cancer screening? Results of a randomized trial Journal of General Internal Medicine , 2000. ; 15 : 24 – 30 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pignone M , Harris R , Kinsinger L . Videotape‐based decision aid for colon cancer screening: a randomized, controlled trial . Annals of Internal Medicine , 2000. ; 133 : 761 – 769 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffith J , Fichter M , Fowler F , Lewis C , Pignone M . Should a colon cancer screening decision aid include the option of no testing? A comparative trial of two decision aids BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making , 2008. ; 8 : 10 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolan J , Frisina S . Randomized controlled trial of a patient decision aid for colorectal cancer screening . Medical Decision Making , 2002. ; 22 : 125 – 139 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith J . Decisions, decisions . British Medical Journal , 2010. ; 341 : c6236 . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bekker HL . Decision aids and uptake of screening . British Medical Journal , 2010. ; 341 : c5407 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thornton H . Shared decision‐making: personal, professional and political . International journal of surgery (London, England) , 2011. ; 9 : 195 – 197 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Wagner C . A decision aid to support informed choice about bowel cancer screening in people with low educational level improves knowledge but reduces screening uptake . Evidence Based Nursing , 2011. ; 14 : 36 – 37 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AIHW . National bowel cancer screening program monitoring report 2008 . Cancer series no. 44. Canberra. Cat No. 40: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing for the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program2008 .

- 16.UK Colorectal Cancer Screening Team . English Pilot of bowel cancer Screening: an evaluation of the second round . Final Report to the Department of Health. February 2006 (Revised August 2006). http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/bowel/pilot‐2nd‐round‐evaluation.pdf. Accessed 7 September 2009 [database on the Internet]2006 .

- 17.Goulard H , Boussac‐Zarebska M , Ancelle‐Park R , Bloch J . French colorectal cancer screening pilot programme: results of the first round . Journal of Medical Screening , 2008. ; 15 : 143 – 148 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewitson P , Glasziou P , Watson E , Towler B , Irwig L . Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (Hemoccult): an update . American Journal of Gastroenterology , 2008. ; 103 : 1541 – 1549 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gigerenzer G , Mata J , Frank R . Public knowledge of benefits of breast and prostate cancer screening in Europe . Journal of the National Cancer Institute , 2009. ; 101 : 1216 – 1220 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barratt A , Trevena L , Davey HM , McCaffery K . Use of decision aids to support informed choices about screening . British Medical Journal , 2004. ; 7464 : 507 – 510 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss BD , Mays MZ , Martz W et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign . Annals of Family Medicine , 2005. ; 3 : 514 – 522 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritchie J , Lewis J . Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers . London : Sage Publications; , 2003. . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pope C , Ziebland S , Mays N . Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data . British Medical Journal , 2000. ; 320 : 114 – 116 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell NC , Murray E , Darbyshire J et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care . British Medical Journal , 2007. ; 334 : 455 – 459 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewin S , Glenton C , Oxman A . Use of qualitative methods alongside randomised controlled trial of complex healthcare interventions: methodological study . British Medical Journal , 2010. ; 339 : b3496 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murtagh MJ , Thomson RG , May CR et al. Qualitative methods in a randomised controlled trial: the role of an integrated qualitative process evaluation in providing evidence to discontinue the intervention in one arm of a trial of a decision support tool . Quality and Safety in Health Care , 2007. ; 16 : 224 – 229 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rapley T , May C , Heaven B et al. Doctor‐patient interaction in a randomised controlled trial of decision‐support tools . Social Science & Medicine , 2006. ; 62 : 2267 – 2278 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith S , Trevena L , Barrat A et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a bowel cancer screening decision aid for adults with lower literacy . Patient Education and Counseling , 2009. ; 75 : 358 – 367 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dixon‐Woods M , Ashcroft RE , Jackson CJ et al. Beyond “misunderstanding”: written information and decisions about taking part in a genetic epidemiology study . Social Science & Medicine , 2007. ; 65 : 2212 – 2222 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clerehan R , Buchbinder R , Moodie J . A linguistic framework for assessing the quality of written patient information: its use in assessing methotrexate information for rheumatoid arthritis . Health Education Research , 2005. ; 20 : 334 – 344 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jepson RG , Hewison J , Thompson A , Weller D . Patient perspectives on information and choice in cancer screening: a qualitative study in the UK . Social Science & Medicine , 2007. ; 65 : 890 – 899 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun V , Gavey N . `With the best of reasons’: cervical cancer prevention policy and the suppression of sexual risk factor information . Social Science & Medicine , 1999. ; 48 : 1463 – 1474 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrison JD , Masya L , Butow P et al. Implementing patient decision support tools: moving beyond academia? Patient Education and Counseling , 2009. ; 76 : 120 – 125 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elwyn G , Legare F , Weijden T , Edwards A , May C . Arduous implementation: does the Normalisation Process Model explain why it’s so difficult to embed decision support technologies for patients in routine clinical practice . Implementation Science , 2008. ; 3 : 57 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jorgensen K , Gotzsche P . Content of invitations for publicly funded screening mammography . British Medical Journal , 2006. ; 332 : 538 – 541 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stefanek ME . Uninformed compliance or informed choice? a needed shift in our approach to cancer screening Journal of the National Cancer Institute , 2011. ; 103 : 1 – 6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz LM , Woloshin S , Black WC , Welch HG . The role of numeracy in understanding the benefit of screening mammography . Annals of Internal Medicine , 1997. ; 127 : 966 – 972 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woloshin S , Schwartz LM , H GW . The effectiveness of a primer to help people understand risk two randomized trials in distinct populations . Annals of Internal Medicine , 2007. ; 146 : 256 – 265 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irwig L , McCaffery K , Salkeld G , Bossuyt P . Informed choice for screening: implications for evaluation . British Medical Journal , 2006. ; 332 : 1148 – 1150 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Entwistle VA , Carter SM , Trevena L et al. Communicating about screening . British Medical Journal , 2008. ; 337 : a1591 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Entwistle VA , Carter S , Cribb A , Mccaffery KJ . Supporting patient autonomy: the importance of clinician‐patient relationships . Journal of General Internal Medicine , 2010. ; 25 : 741 – 745 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reyna VF . A theory of medical decision making and health: fuzzy Trace Theory . Medical Decision Making , 2008. ; 28 : 850 – 865 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elwyn G , Lloyd A , Cording E , Joseph‐Williams N , Edwards A , Thomson R . Option Grids: A Potential Solution to Over‐engineered Patient Decision Support . International Conference on Communication in Healthcare ; Chicago, U.S : Northwestern University; ., 2011. . Available at http://www.optiongrid.co.uk/ (accessed 1 December 2011) . [Google Scholar]