Photovoice Ethics: Critical Reflections From Men’s Mental Health Research (original) (raw)

Abstract

As photovoice continues to grow as a method for researching health and illness, there is a need for rigorous discussions about ethical considerations. In this article, we discuss three key ethical issues arising from a recent photovoice study investigating men’s depression and suicide. The first issue, indelible images, details the complexity of consent and copyright when participant-produced photographs are shown at exhibitions and online where they can be copied and disseminated beyond the original scope of the research. The second issue, representation, explores the ethical implications that can arise when participants and others have discordant views about the deceased. The third, vicarious trauma, offers insights into the potenial for triggering mental health issues among researchers and viewers of the participant-produced photographs. Through a discussion of these ethical issues, we offer suggestions to guide the work of health researchers who use, or are considering the use of, photovoice.

Keywords: research evaluation, methodology; ethics; moral perspectives; qualitative; Canada; North America; North Americans; qualitative methods; research design, photography, photovoice; research strategies

Developed by Wang and Burris (1997), photovoice methods draw on the principles of participatory action research (PAR) wherein community members are encouraged to document and share their experiences of health and illness through photographs and narratives. In providing a mechanism and platform for participants to convey their experiences of health and illness, and construct a visual ontology of illness, photovoice can garner rich and nuanced accounts, and challenge existing ontological assumptions around illness and wellness (Oliffe & Bottorff, 2007). Through the novel act of applying analytic strategies to interpret photographs, photovoice disrupts the primacy of oral traditions and allows researchers to access different spheres of illness experience. Photovoice can also challenge the production of knowing, empowering participants to actively construct and represent (and even start interpreting) what is important to them regarding particular health and illness phenomena (Catalani & Minkler, 2010; Clements, 2012; Creighton, Brussoni, Oliffe, & Han, 2017).

Although much has been written about the benefits of using photovoice, discussions about ethical considerations, especially in the context of researching health and illness, has received little attention (Brydon-Miller, Greenwood, & Eikeland, 2006; Clark, Prosser, & Wiles, 2010; Joanou, 2009; Lal, Jarus, & Suto, 2012). In part, this is due to a primary focus on methods and empirical findings (Warin, 2011). However, as the use of photovoice increases in qualitative health and illness research and, more specifically, in mental health and illness work, it is important to discuss ethical issues in more detail. The purpose of this article is to offer a critical reflection on emergent ethical issues in photovoice research arising from a recent photovoice study of men’s depression and suicide.

Photovoice Research

Although approaches to photovoice often vary (Catalani & Minkler, 2010), consistent is the goal to democratize the research process and drive social change (Hergenrather, Rhodes, Cowan, Bardhoshi, & Pula, 2009). In terms of the micro dynamics of democratization, and specifically in relation to the researcher, the act and practice of data being collected (initially and preinterview) beyond the researcher—out of the interview environment, with the participant driving the production of data—effectively “flattens” the power dynamics often present in the research process, elevating the voice and interpretation of the participant in unique and meaningful ways. This can be very important in the context of stories of illness and affliction whereby this elevation (of participant) is often necessary to foster expression and authentic storytelling. In terms of broader structures of knowledge production and engagement, photovoice participants can raise awareness and increase collective knowledge about an issue, both through participant discussion (Boxall & Ralph, 2009) and by sharing photographs in broader community forums (López, Eng, Randall-David, & Robinson, 2005; Moletsane et al., 2007; Wiersma, 2011). In the specific context of mental health and illness, exhibits of participant-produced photographs have been used to raise public awareness and destigmatize depression and suicide (Clements, 2012; Panazzola & Leipert, 2013; Sitvast, Abma, & Widdershoven, 2010; Thompson, Hunter, & Murray, 2008).

Photovoice has also been touted as aiding the feasability to qualitatively investigate sensitive and complex health issues (Catalani & Minkler, 2010). It does this by making available ways to engage participants who might be reluctant to participate in an interview (or less likely to be invited to participate in a research interview). Photographs in and of themselves can provide a buffer to the potential awkardness invoked by structured qualitative interviews (Oliffe & Bottorff, 2007). Because participant-produced photographs are shared on screen or in hard copy, the interview interactions can facilitate “freestyle” conversations between participants and researchers (Oliffe & Bottorff, 2007). Moreover, in contrast to structured interviews where a set of questions are asked of the participant, in a photovoice interview, the participant is in charge of the speed and topic of the conversation. With control over when to move from one photograph to the next, participants decide what to share, and when to elaborate or move on from specific content and topics. Others have noted that photovoice can help overcome some of the limitations of language (Affleck, Glass, & MacDonald, 2013) when participants are attempting to explain particularly emotional experiences (Jurkowski & Paul-Ward, 2007). Based on their photovoice study, Kantrowitz-Gordon and Vandermause (2015) suggested that photographs can afford distance from a painful experience as well as providing an avenue for metaphors and meaning that go beyond what might ordinarily be expressed through words alone. Metaphor, analogy, and other acts of (in this case visual) interpretation are powerful for not only emphasizing the voice of participants but also acting as a protective layer in allowing difficult and sensitive things to be talked about and represented.

Ethics Considerations in Photovoice Research

Although dated, the Wang and Redwood-Jones (2001) article is one of the few published works that explicitly discusses ethical considerations in photovoice methods, covering issues of privacy, safety, autonomy, representation, and recruitment. Using a case example of a large-scale photovoice project in Flint, Michigan, USA, they discussed youth’s, adults’, and policy-makers’ involvement in community representation, advocating for social and environmental change (Wang & Redwood-Jones, 2001). Reflecting on the ethical dilemmas that emerged through this project, Wang and Redwood-Jones (2001) highlighted the following needs:

- Careful deliberation about participant safety when taking photographs that could potentially cast a person or position an issue in a negative light.

- Gaining clear and explicit written consent from the participant photographer regarding the rights they passed to the researcher.

- Sustaining participant ownership of photographs to prevent the use of photographs for commercial use and ensuring the appropriate use of images.

Although relevant to the times, much has changed since Wang and Redwood-Jones’s (2001) article. The advances of the Internet, social media, and digital photography have forever altered cultural connections to photographs, and by extension, photovoice research. In line with such changes, new ethical issues specific to photovoice have emerged adding complexity to health and illness research, and more specifically, mental health and illness research. In this article, we discuss three ethical considerations that arose from a photovoice study on men’s depression and suicide wherein the perspectives of men who had previously experienced suicidality, and men and women who had lost a male to suicide took and talked to their photographs in sharing their experiences. Through detailing these ethical issues, we offer suggestions to guide the work of health researchers who use, or are considering the use of, photovoice methods.

A Photovoice Study of Men’s Depression and Suicide

In North America and Europe, men account for four out of every five suicides (Nock et al., 2008; Payne, Swami, & Stanistreet, 2008; Statistics Canada, 2012). The purpose of the Man Up Against Suicide project was to raise public awareness and destigmatize men’s depression in lobbying for male suicide prevention programs. Photovoice methods were used to provide avenues for participants to depict and describe their experiences and communicate their perspectives about men’s depression and suicide.

Following University ethics approval, 80 participants including 30 women and 20 men, who had lost a male to suicide, and 30 men who had previously experienced suicidal thoughts, plans, and/or attempts took part in the photovoice study. To recruit participants, postcards and posters were used at a variety of public locations and disseminated online through social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter), online classified ads (e.g., Craigslist), and community group newsletters. Potential participants were invited to contact the project coordinator if they were interested to share their stories about having lost a male to suicide or if they had previously experienced suicidality (thoughts, plans, and/or nonfatal suicidal behaviors). Participants were 19 years or older, English speaking, and resided in Canada. Eligible participants met twice with a research team member. The purpose of the first meeting was to explain the study and the photovoice component, obtain written consent (detailed later in this article), collect demographic information, and provide any additional details to participants about the project. This meeting also helped build rapport between participants and the researcher. Participants were invited to take a series of photographs to tell their story with a focus on how male suicide might be prevented. Participants had up to 2 weeks to complete the photo assignment, after which a second interview—lasting 1 to 3 hours—took place wherein participants were invited to tell their stories through the images they had submitted.

Individual interviews began with open-ended prompts and questions: Tell me a little about your background, family and friends, and work, and what are your connections to and experiences around male suicide? Participants were invited to tell their stories through their photographs, with occasional prompts including “What does this photograph mean to you?” “Why did you decide to take it?” and “Who is in this photograph?” to elaborate on the details shared by participants. For participants who had lost a man to suicide, there were questions that focused on their relationship to the deceased prior to his death, their reaction to hearing the news, and how they made sense of the death. Men who had, themselves, previously experienced suicidality were asked about their perspectives and strategies to avoid self-harm.

Data were collected, 2014–2016, from participants residing in urban and rural communities in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada. Interviews were conducted by researchers trained in qualitative methods and trauma research, and participants received Can$200 to acknowledge their contribution to the study. Although this honorarium might be considered high, we thought it appropriate given the expected investment of time and energy by the study participants. Contact information for professional mental health and grief and crisis intervention services were provided to participants. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and checked for accuracy. All the transcribed interviews were anonymized by removing potentially identifying information, and participants’ interview transcripts were allocated a numerical code and a pseudonym to link specific photographs and narratives to the inductively derived study findings.

Emergent Ethics Issues

Over the course of the study, the research team formally met on a weekly basis to discuss the project and emergent ethical issues. Early on, we narrowed specific problems, discussed philosophical underpinnings, and proposed potential solutions for challenges that emerged during data collection. Notes detailing these conversations were made, and these data were revisited and analyzed using interpretive descriptive methods (Thorne, 2016). Specifically, the authors read the notes to inductively derive descriptive labels, and data were organized within and across categories. Consensus about the findings and illustrative examples were reached through numerous meetings and in the writing of the current article. The first issue, indelible images, details the complexity of consent and copyright when participant-produced photographs are shown at exhibitions and online where they can be copied and disseminated beyond the original scope of the research. The second issue, representation, focuses on the ethical implications that can arise when participants and others have discordant views. The third issue, vicarious trauma, highlights the potential for triggering mental health issues in researchers and viewers of the particiant-produced photographs. Through a discussion of these ethical issues, interpretations and suggestions are offered to guide the work of health researchers who use, or are considering the use of, photovoice methods.

Indelible Images

Since Wang and Redwood-Jones’s (2001) article, (much of) the world has experienced a digital revolution. Social media sites including Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, and Twitter have made the sharing and dissemination of photographs on the Internet increasingly ubiquitous. The production of high-quality digital images, while still not entirely democratized, is no longer the purview of professional photographers. In light of these changes, and the experiences of completing the Man Up Against Suicide project, we found ethical issues around content and copyright of participant-produced photographs were ever present.

Because digital images can be easily downloaded and repurposed, consent for the use of the participant-produced photographs is especially complex. University research ethics boards (REBs) have raised concerns about the dissemination of online images and public exhibitions of participant-produced photographs and, given the speed by which technologies have advanced, the ability of participants to understand the potential risk of such dissemination (Allen, 2012; Catalani & Minkler, 2010; Ponic & Jategaonkar, 2012). With this in mind, we ensured approval to not only share participant photographs, but in regard to the specific formats and contexts in which the images were to be used. To do this, we followed the three-stage process of consent outlined by Wang and Redwood-Jones (2001) that included (a) an initial consent form with the project aims, risks, and benefits and rights of the participants, (b) a consent form for nonresearch participants who were photographed by participants, and (c) a final consent regarding the release of creative materials. In the last form, participants could choose whether they wanted their photographs to be used only for the research interview or also for manuscripts, books, conference presentations, and in-person and online exhibitions (Pink, 2007; Prosser & Loxley, 2008). In an additional process, at the completion of the photovoice interview, participants were invited to revisit their consent and, given the opportunity, to remove photographs or limit their use. Although study consent forms delineated if the participant-produced photographs could be used and the specific ways that they could be utilized within the project, it was also important to have locale and platform specific knowledge of copyright and privacy issues in photography (Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic, 2014).

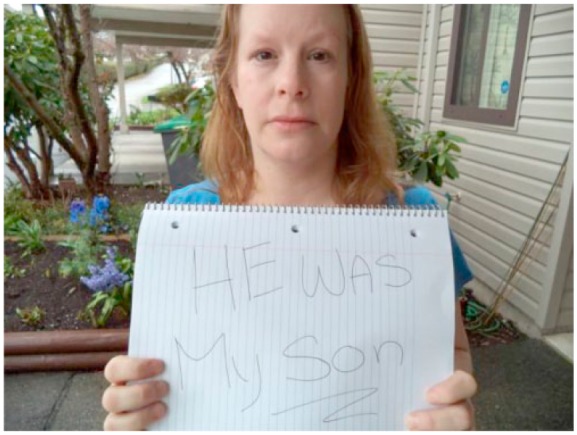

Despite efforts to be as thorough as possible in raising participant awareness about the implications of sharing photographs, we still had some concerns about how the use of photographs might heighten some participant vulnerabilities. For example, a 22-year-old participant lost her brother to suicide when he was away at University. Her photographs depicted the sadness, shock, and surprise that her family had experienced following his death. In the months leading up to his death, there was no indication that he was experiencing distress or suicidal thoughts, and the mother, in particular, felt a deep sense of guilt and self-blame that she had been unable to prevent her son’s suicide. The sister of the deceased included Figure 1, a picture of her mother holding a note, which said, “He was my son.”

Figure 1.

He was my son.

Although the participant’s mother (depicted in the Figure 1) consented to the reproduction of the photograph, enabling us to share this powerful image here, online, in conference presentations and at in-person exhibits, we were concerned that her viewpoint could change over time, wherein she might crave some respite and anonymity in her grief. We wondered if her emotional state at the time of the study might have also impeded her ability to give valid consent for the use of the photograph.

Conversely, excluding the photograph from these knowledge sharing activities—when the participant’s mother had given consent—seemed at odds with a methodology centered on giving participants voice. After all the philosophical underpinning of photovoice is to destigmatize issues and provide platforms for individuals to speak up and be heard (Boxall & Ralph, 2009; Clark et al., 2010; Ponic & Jategaonkar, 2012; Reid et al., 2011). It seemed paternalistic for us to impose our own judgments in censoring content that we had solicited. As Lincoln (2005) argued, some University REBs and researchers have problematically adopted the stance that those in the academy are better able than participants themselves to protect participants from undue harm.

The other option available to us to maintain the participant’s mother’s privacy was to anonymize her photograph using computer software to alter pixilation and/or blur her face (Wang & Redwood-Jones, 2001; Wiles, Crow, Heath, & Charles, 2008). We were reticent to employ such an approach. As Wiles et al. (2008) reflected, the effects of altering images can be variable, and achieving anonymity with such adjustments can decontextualize and perhaps obscure the meanings and experiences that participants are wanting to communicate. When dealing with a stigmatized topic such as men’s depression and suicide, Banks’s (2007) affirmed that pixelating images can dehumanize the individuals in them. To attempt to “protect participants from themselves” and deny them the opportunity to fully participate in the project in the way that they chose seemed both patronizing and counter to the central goal for using photovoice methods—to empower participants and provide them a platform to tell their stories.

In this scenario, and in similar situations that we encountered over the course of the Man Up Against Suicide project, the values of photovoice and PAR in leveling the hierarchies between researcher and participant prevailed. After rechecking the signed consent, and confirming earlier permissions, we included this photograph at in-person exhibitions, the online gallery, and presentations and articles (including the current article) arising from the project. In line with participatory research principles, consent around the use of photographs was understood as provisional, wherein the participant or person in the photograph could withdraw the image at any time. However, herein lies another challenge—our inability to guarantee the withdrawal of images that have previously been shared.

For example, Figure 1 was copied by a filmmaker who, struck by the power of the image, included it in a written pitch soliciting financial support for the making of a documentary on suicide. Although the filmmaker had no ill intent, and agreed to remove the photograph on our request, it was clear that the photograph had been copied and was used, albeit briefly, outside of the original agreement and consent between the researcher and participant. The online photograph gallery, despite having the right click save options disabled on the image thumbs and click expanded photographs, could still be copied. For example, a screen capture and crop of the image or taking a photograph of the photograph at an in-person exhibition could have been used to copy and reproduce the image. This experience confirms that photovoice researchers and University REBs cannot guarantee that participant-produced photographs will not be copied and used outside of the study consent and original researcher-participant agreement. In terms of remedying this, it is imperative that participants are aware of this potential risk, and a note to that effect should be included in the consent forms.

In summary, the ethical issues inherent in indelible images poignantly reminded us of the complexities of using photovoice methods and the limits of what can be reasonably promised both in terms of the use and reproduction of participant-produced photographs in this digital age. We advocate for signed consent wherein participants and individuals agreeing to be photographed give permission for their images to be shared publicly by the researchers. Included in the consent[s] also should be explicit notification that there is the potential risk that photographs may be copied and/or used outside the original study agreement. Building on this point, we strongly recommend that the research team engage in ongoing discussions to nimbly respond to emergent issues unique to photovoice methods and the use of photographs in health and illness research.

Representation

True to constructivist ontologies (Elliott, 2005), study participants’ “storying” of the deceased was privileged as an important account of the life and death of a male by suicide. Within this context, there was potential for other accounts to emerge, which might counter or contradict the participant story being offered. Although the existence of contrasting positions (within a family, social network, community) is understood and recognized within qualitative research, this is a particularly important consideration in suicide research. Here, we are collating a story on a (deceased) other, subjectively constructed, potentially disputable across persons, and certainly heavily shaped by the life views of the storyteller. This raises a series of complexities around how the research fosters certain subject positions and even (arguably) reifies particular ontologies of illness, wellness, and care (or in this case loss).

In terms of the study at hand, participants who told stories about a loved one who had died by suicide often revisited painful experiences and memories wherein a range of photographs were used to explore and explain the circumstances leading to the man’s suicide. Embedded here was the potential for disparate views about contributing factors to male suicide and as such for people to narrate the events, causes, and consequences very differently according to their subject position, life world, and world views. An example of this related to a 24-year-old participant who lost her brother when he hung himself from a tree less than a kilometer from where she lived. Although she was close to her brother, and remembered him lovingly as a kind and gentle person, she was also clear that he had been experiencing challenges linked to drug and alcohol overuse as well as mental illness in the years leading up to his suicide. Included in the photographs that she submitted were images of her brother smoking marijuana with the caption “Dazed and Confused” (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Dazed and Confused.

This participant’s mother also participated in the study. In deciding to include the sister’s perspective about the intersections between substance use and suicide at an “in-person” exhibition (as requested by the sister), we anticipated the potential for emotional distress and/or disagreement and conflict between the mother and daughter regarding the deceased’s substance use. Upon seeing the sister’s photograph and caption, it turned out that the mother’s suspicions about her son’s drug and alcohol overuse were confirmed. Although the severity of the situation (according to the sister) was not known to the mother, the details to some degree, over time, afforded the mother context to better understand that there were a myriad of factors implicated in her son’s suicide. Although the sharing that occurred in this example provided clarity, we were reminded that representations can vary significantly, and the potential for distress was ever present, especially in the context of the grief and loss survivors experienced in losing a loved one to suicide. Other than asserting acknowledgment of the constructivist nature of photography in shaping a worldview, we found no way of mitigating the potential for multiple and potentially discordant representations of the deceased. Acknowledging the subjectivity of representation, however, is an important component of the analytic process and should be accounted for within the ethics application and the empirical findings.

In deciding to include diverse representations, we attempted to align to the constructivist ontologies (Elliott, 2005) we espoused. However, there were limits wherein within the photographic exhibitions, we could not fully tell or represent all the stories that were shared by participants. Recognizing this, we asked each participant to nominate and caption three of their photographs best suited to be included in exhibitions. Although we thoughtfully considered participant preferences, ultimately the research team decided on the photographs that were shown. This was done to reduce content repetition (e.g., there were many photographs of landscapes—mountains and sea) and include diverse perspectives and expressions (e.g., grief, hope, anger, distress) in the exhibited participant-produced photographs and captions. We recognized, however, that by limiting the number and governing the content of the photographs shown, we strongly influenced the representation of the collection as a whole, and by extension, we tendered particular participant narratives and excluded others. For example, one participant submitted a photograph of his penis as a way of representing his struggle as a gay survivor of child sexual abuse. Referring to the verbal and written instructions (included on the consent form) that prohibited the use of nudity or sexually explicit images, we explained that the photograph could not be used in presentations, in articles, or within online or the “in-person” exhibitions. The participant expressed concerns that he had wasted his time because his photographs and narratives could not be shared. We were reminded by this situation that photovoice methods must be explicit and reiterated with all participants with regard to what cannot—as well as what can be publicly shared about their experiences.

Issues of representation also emerged when the participant photographs were viewed by others. For example, when shown online or at “in-person” exhibitions (see Figure 3), the participant-produced photographs and accompanying narratives took on a somewhat authorless state, inviting the viewers to engage, interpret, and respond to what they saw (as distinct from what the participant might have been wanting to communicate). Adages—a picture is worth a thousand words and photographs never lie—imply images can and do contain knowledge and truth (Clark-Ibanez, 2007). However, while the photographs exhibited on behalf of the Man Up Against Suicide study participants were linked to their accompanying narratives, a range of potentially diverse interpretations, views, and conversations emerged. This points to the importance of recognizing the value and limits of visual methodologies. That, in fact, photographs can also be misleading, they can be repurposed by the “user,” and they can be misinterpreted by the viewer.

Figure 3.

Photo exhibition.

With respect to representation, we recognized the potential for exhibit audience readings of participant photographs and narratives in ways that neither we nor the participant had intended. Many photographs were highly evocative, vividly depicting the deep pain experienced by participants. Guilt, regret, loss, and pain all emerged, and the deeply personal nature of the photographs served to draw viewers into conversations about their experiences, and the need for male suicide prevention programs. That said, volunteering to have these photographs exhibited heightened the vulnerability of both the participant and the viewer. The participant because of the potential for, as Clark et al. (2010) noted, upset if a viewer misinterprets the message or the intention of the photograph and narrative, and the viewer if a photograph elicits intense negative triggers rather than a therapeutic moment.

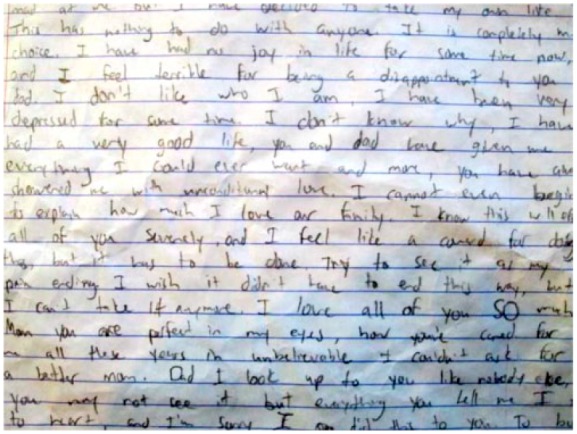

An example of this came in the photograph and narrative of a man who had lost his son to suicide. A 52-year-old male participant recalled how he had received a call from his wife to come home immediately. He arrived home to find his 16-year-old son on the ground in the barn having been cut down from the rafters from which he had hung himself. Inside the house, the parents and older sister found a note detailing the distress the deceased had endured leading up to the suicide. In his note, the son apologized for the pain he had caused, saying that his family had given him all the love and support that he ever could have hoped for. The participant submitted a photograph of the note (Figure 4) suggesting that this image might raise awareness about how even families that appear “happy” with children who seem well-adjusted can experience the tragic loss of suicide. The participant articulated a fervent wish that he should have modeled vulnerability to his son, so that his son might have felt free to talk about his depression and feelings of failure. In his narrative, the participant spoke courageously, imploring other fathers to break the silence and stoicism modeled to their sons.

Figure 4.

Last words.

Although the participant’s motivation of altruism and a desire to reduce male suicide through challenging dominant frames of masculinity was clear to us, we were aware of the potential for misinterpretation and/or triggering for viewers/readers of this letter. For those unprepared, reading this private letter might trigger distress and anxiety—the antithesis of the participant’s intent. To create as safe an environment as possible in the context of the exhibition, we provided a list of services that attendees could access if they experienced distress. In the larger exhibitions, particularly on opening nights, professional counselors and mental health care providers were available to those who wanted to discuss their response to the photographs and narratives. Warnings were also included in the exhibit programs that some of the photographs and narratives might trigger viewers.

Available through the ethical issues that representation brings forth are insights to the complexities and challenges for doing constructivist photovoice work. In terms of ethics, it is clear that showing participant-produced photographs demands significant planning and expertise to minimize the risk for harm to participants and viewers. Although these issues might be amplified by morally loaded health issues such as men’s depression and suicide, sharing participant-produced photographs from photovoice studies is an ethically intricate and specialized knowledge translation strategy.

Vicarious Trauma

We were conscious of the potential for photovoice interviews to cause participant distress. Even when suicide or suicidality was in the distant past, the telling of the stories could bring up painful memories. Foreseeing this, we scaffolded interviews to cycle participants between their story and the photographs to provide some respite and distance from the suicide or suicidality they had previously experienced (Kantrowitz-Gordon & Vandermause, 2015). Prior to leaving the interview, we ensured that participants were not in distress, asking them about their experience of the interview and the photovoice project amid providing a comprehensive list of mental health resources that they could access should they become triggered. Fortunately, the interview process did not appear to have negative effects on participants and, for many, it served as a therapeutic experience. Indeed, for some participants, the photovoice interview was emotionally freeing in being able to talk about their previous experiences of suicidality or having lost a man to suicide.

What neither we nor the University REB did not fully anticipate were challenges to the mental health of the research staff (Mitchell & Irvine, 2008). The research team, including the project manager, interviewers, and transcribers, came to the project not as disinterested parties but connected in some way to the issue of suicide. Most had lost someone to suicide, and all the project staff were deeply affected and moved by the participant photographs and narratives. Hearing graphic details about suicide amid talking about photographs depicting struggles with mental illness deeply affected some research staff. One story discussed by a member of the research team was that of a 23-year-old woman whose younger brother had died by suicide. Although he had been acting a “little oddly” for a while, the participant only became aware of the extent of her brother’s mental illness when he was admitted to the psychiatric unit of the local hospital after experiencing a psychotic break. As an inpatient, her brother seemed to be gradually getting better and reported that he was looking forward to being discharged. Unfortunately, he escaped from the locked ward. His friends and family searched for days until being told by the police that his remains had been found next to the train tracks. Struck by the powerful imagery and graphic detail, the researcher had difficulty moving forward with other interviews. In addition to the pressure on interviewers invoked by hearing about gruesome details and/or being exposed to the pervading tone of hopelessness, some interviews went on too long—some up to 3 hours. Moreover, despite supervisor advice to do only one interview per day, some researchers completed two or even three interviews in a day, leaving them exhausted.

In the past two decades, there has been an abundance of research focused on describing the impact of hearing stories of trauma and suffering on the researcher (Beale, Cole, Hillenge, McMaster, & Nagy, 2004; Bowtell, Sawyer, Aroni, Green, & Duncan, 2013; Paterson, Gregory, & Thorne, 1999). As Connolly and Reilly (2007) differentiated, the psychotherapist, social worker, or counselor attends to the story from the perspective of a helper, someone who will work with the individual to move them toward a place of healing, whereas the researcher is a repository for stories of trauma, left holding the narratives intact (Connolly & Reilly, 2007). Figley (1995) advised that compassion fatigue, “the natural consequent behaviours and emotions resulting from knowing about the traumatizing event experienced by a significant other” (p. 13), and vicarious trauma commonly affect researchers engaging in explorations of difficult material.

Embedded in this issue are also broader considerations in researching suffering, distress, illness, and care. Emotions are not merely “researched,” and participant experiences of suffering are not merely collated—rather, there is a coproduction of this story, and the researcher necessarily is part of the narration. Moreover, the affective atmosphere of the moment—or series of moments—around suicidality, in this case, is experienced, created, and endured by all participants, including the researcher. In different ways than participants, the researchers can suffer, absorbing (at times even deflecting) the negative affectivity. To access as a researcher is in turn to engage in as a person, with subjective affective entanglements, which offer considerable complexity in and around such research. Thus, the interpersonal and the affective (unintended consequences) are not only crucial to explore and to embrace but also to ensure that such entanglements do not harm either researcher or participant. The more powerful the approach, the more engagement one will also see from researchers—and the greater impact on the emotions and lifeworlds of all participants. This is a core ethical consideration.

Participant-produced photographs summonsed stories and drew participants and interviewers into many compelling narratives. In this regard, photovoice in men’s depression and suicide research, while yielding rich data and insights, also comes with significant risks. Patton (1990) suggested that the researcher should adopt a position, “empathic neutrality”—that is, empathic engagement with the stories the participants share, but neutrality regarding the content of the material generated. However, as Connolly and Reilly (2007) countered, trying to be “neutral and objective” when hearing powerful and provocative stories can amplify the experience of distress among researchers. Likewise, Behar (1997) maintained that sharing the experience and how it changed you is the true and honest essence of meaningful qualitative research. Although arguing that “anthropology that doesn’t break your heart isn’t worth doing” (Behar, 1997, p. 177), there is an ethical and moral responsibility to protect researchers from burnout and the risks that accompany photovoice interviews.

In our project, we followed Wray, Markovic, and Manderson’s (2007) recommendations. First, the principal investigator monitored researcher distress and fatigue, encouraging researchers to attend the debrief sessions offered by experts in counseling psychology. The primary remedy shared in these individual or group sessions (depending on the researcher’s preference) related to skills and strategies for exerting more control over the structure and duration of the interview (e.g., keeping on time and on topic). Although the interview guide was designed for interviews to last between 60 and 90 minutes, interviewers reported that it was difficult to close out participants’ talk, especially in the midst of them telling (or retelling) their experiences of losing a man to suicide or previous experiences of suicidality. Interviewers also observed that when interviews went beyond 90 minutes, participant fatigue was evident. To overcome this, interviewers were coached to preempt the interview to gently and sensitively remind participants that the interview was time limited, and usually was complete within 90 minutes. Strategies to self-manage feelings of depression and anxiety were also shared when necessary. To protect transcribers from being caught off guard by stories of sexual abuse, domestic violence, exploitation, or drug use, interviewers provided a list of potential triggers for each of the digitally recorded interviews. The research team also met to discuss progress, to discuss interpretations of the data, and to provide updates on their own energy levels and well-being.

Conclusion

Many photovoice and health scholars conclude that there is a need to develop an ethical framework that is contextually sensitive and responsive to current technologies and social realities (Clark et al., 2010; Guillemin & Gillam, 2004; Ponic & Jategaonkar, 2012; Reid et al., 2011). Rather than relying on the existing University REB sensitivities and approvals, photovoice should be adapted to address a range of ethical issues and strategies, including those outlined in the current article. To avoid disempowering participants, researchers need to be prospectively aware of and responsive to the unique considerations in conducting photovoice research.

While advocating thoughtful consideration and anticipation of ethical complexities, some of which may be unique to photovoice methods, it is important to acknowledge the autonomy of researchers and participants in the current study. For example, researchers presumably embarked on the project for their own benefit (self-interest) and for the benefits of others (altruism). Similarly, participants, to varying degrees, might be understood as choosing to speak up about the taboo issue of suicide to benefit self and others. Our intent, therefore, is to raise awareness and stimulate dialogue about the ethical considerations in photovoice rather than to discourage the use of this important and powerful method. Through encouraging researchers and participants to anticipate an array of ethical considerations in photovoice, study designs and procedures can be developed to fully embrace the complexities of this robust method.

In terms of limitations, it is acknowledged that the current article does not fully engage an in-depth discussion of various ethics theories and frameworks. To address this, we encourage photovoice researchers to extend on our insights to delve into sensitive and ethically challenging areas of human experience to further important debates about photovoice research. It is our hope that this article goes some way toward advancing those much needed conversations as the means to ethically harvest the valuable contributions photovoice methods can make to health and illness research.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to all the study participants.

Author Biographies

Genevieve Creighton, is a post doctoral Fellow in the UBC School of Nursing.

John L. Oliffe, is a professor in the UBC School of Nursing.

Olivier Ferlatte, is a post doctoral Fellow in the UBC School of Nursing.

Joan Bottorff, is a professor in the UBC School of Nursing.

Alex Broom, is a professor of Sociology at UNSW Sydney.

Emily K. Jenkins, is an assistant professor in the UBC School of Nursing.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was made possible by Movember Canada (Grant #11R18455). The first author was supported by a Post Doctoral Fellowship from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

References

- Affleck W., Glass K. C., MacDonald M. E. (2013). The limitations of language: Male participants, stoicism, and the qualitative research interview. American Journal of Men’s Health, 7, 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen Q. (2012). Photographs and stories: Ethics, benefits and dilemmas of using participant photography with Black middle-class male youth. Qualitative Research, 12, 443–438. [Google Scholar]

- Banks B. (2007). Using visual data in qualitative research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Beale B., Cole R., Hillenge S., McMaster R., Nagy S. (2004). Impact of in-depth interviews on the interviewer: Roller coaster ride. Nursing & Health Sciences, 6, 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar R. (1997). The vulnerable observer: Anthropology that breaks your heart. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowtell E., Sawyer S. M., Aroni R., Green J., Duncan R. (2013). “Should I send a condolence card?” Promoting emotional safety in qualitative health research through reflexivity and ethical mindfulness. Qualitative Inquiry, 19, 652–663. [Google Scholar]

- Boxall K., Ralph S. (2009). Research ethics and the use of visual images in research with people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34, 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brydon-Miller M., Greenwood D., Eikeland O. (2006). Strategies for addressing ethical issues in action research. Action Research, 4, 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic. (2014). Copyright and privacy in photography. Retrieved from https://cippic.ca/en/FAQ/Photography_Law#Who

- Catalani C., Minkler M. (2010). Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior, 37, 424–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A., Prosser J., Wiles R. (2010). Ethical issues in image-based research. Arts & Health: An International Journal for Research, Policy and Practice, 2, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Ibanez M. (2007). Inner-city children in sharper focus: Sociology of childhood and photo-elicitation interviews. In Stanczak G. C. (Ed.), Visual research methods: Image, society and representation (Vol. 47, pp. 167–196). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Clements K. (2012). Participatory action research and photovoice in a psychiatric nursing/clubhouse collaboration exploring recovery narrative. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19, 785–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly K., Reilly R. C. (2007). Emergent issues when researching trauma: A confessional tale. Qualitative Inquiry, 13, 522–540. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton G. M., Brussoni M., Oliffe J. L., Han C. (2017). Picturing masculinities: Using photo-elicitation in men’s health research. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(5), 1472–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J. (2005). Using narrative in social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Figley C. (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary trauma stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. New York: Brunner Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Guillenmin M., Gillam L. (2004). Ethics, reflexivity, and “ethically important moments” in research. Qualitative Inquiry, 10(2), 261–280. [Google Scholar]

- Hergenrather K. C., Rhodes S. D., Cowan C. A., Bardhoshi G., Pula S. (2009). Photovoice as community-based participatory research: A qualitative review. American Journal of Health Behavior, 33, 686–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joanou J. P. (2009). The bad and the ugly: Ethical concerns in participatory photographic methods with children living and working on the streets of Lima, Peru. Visual Studies, 24, 214–223. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkowski J. M., Paul-Ward A. (2007). Photovoice with vulnerable populations: Addressing disparities in health promotion among people with intellectual disabilities. Health Promotion Practice, 8, 358–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz-Gordon I., Vandermause R. (2016). Metaphors of distress: Photo-elicitation enhances a discourse analysis of parents’ accounts. Qualitative Health Research, 26(8), 1031–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal S., Jarus T., Suto M. J. (2012). A scoping review of the photovoice method: Implications for occupational therapy research. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79, 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y. S. (2005). Institutional review boards and methodological conservatism. In Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. S. (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 165–181). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- López E., Eng E., Randall-David E., Robinson N. (2005). Quality-of-life concerns of African American breast cancer survivors within rural North Carolina: Blending the techniques of photovoice and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 99–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell W., Irvine A. (2008). I’m okay, you’re okay? Reflections on the well-being and ethical requirements of researchers and research participants in conducting qualitative fieldwork interviews. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 7, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Moletsane R., de Lange N., Mitchell C., Stuart J., Buthelezi T., Taylor M. (2007). Photo-voice as a tool for analysis and activism in response to HIV and AIDS stigmatisation in a rural KwaZulu-Natal school. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 19, 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock M. K., Borges G., Bromet E., Cha C., Kessler R., Lee S. (2008). Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic, 30, 133–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Bottorff J. L. (2007). Further than the eye can see? Photo elicitation and research with men. Qualitative Health Research, 17, 850–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panazzola P., Leipert B. D. (2013). Exploring mental health issues of rural senior women residing in southwestern Ontario, Canada: A secondary analysis photovoice study. Rural and Remote Health, 13, Article 2320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson B., Gregory D., Thorne S. (1999). A protocol for researcher safety. Qualitative Health Research, 9, 259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Payne S., Swami V., Stanistreet D. (2008). The social construction of gender and its influence on suicide: A review of the literature. Journal of Men’s Health, 5, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pink S. (2007). Doing visual ethnograph. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ponic P., Jategaonkar N. (2012). Balancing safety and action: Ethical protocols for photovoice research with women who have experienced violence. Arts & Health: An International Journal for Research, Policy and Practice, 4, 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser J., Loxley A. (2008). Introducing visual methods (No. 010). National Centre for Research Methods: University of Leeds. [Google Scholar]

- Reid C., Ponic P., Hara L., LeDrew R., Kaweesi C., Besla K. (2011). Living an ethical agreement: Negotiating confidentiality and harm in a feminist participatory action research project. In Creese G., Frisby W. (Eds.), Feminist methodologies in community research. (pp 189–209). Vancouver: University of British Columbia. [Google Scholar]

- Sitvast J. E., Abma T. A., Widdershoven G. A. M. (2010). Facades of suffering: Clients’ photo stories about mental illness. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 24, 349–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2012). Table102-0561—Leading causes of death, total population, by age group and sex, Canada, annual CANSIM (database). Retrieved from http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1020561

- Thompson N. C., Hunter E. E., Murray L. (2008). The experience of living with chronic mental illness: A photovoice study. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 44, 14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. (2016). Interpretive description. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Burris M. (1997). Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education Behaviour, 24(1), 369–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Redwood-Jones Y. A. (2001). Photovoice ethics: Perspectives from flint photovoice. Health Education & Behaviour, 28, 560–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warin J. (2011). Ethical mindfulness and reflexivity: Managing a research relationship with children and young people in a 14-year Qualitative Longitudinal Research (QLR). Qualitative Inquiry, 17, 805–814. [Google Scholar]

- Wiersma E. C. (2011). Using photovoice with people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease: A discussion of methodology. Dementia, 10, 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles R., Crow G., Heath S., Charles V. (2007). The management of confidentiality and anonymity in social research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 9(2), 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wray N., Markovic M., Manderson L. (2007). “Researcher saturation”: The impact of data triangulation and intensive research practices on researcher and qualitative research process. Qualitative Health Research, 17, 1392–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]