Cholangiocarcinoma — evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2018 Mar 1.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017 Oct 10;15(2):95–111. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.157

Abstract

Cholangiocarcinoma is a disease entity comprising diverse epithelial tumours with features of cholangiocyte differentiation: cholangiocarcinomas are categorized according to anatomical location as intrahepatic (iCCA), perihilar (pCCA), or distal (dCCA). Each subtype has a distinct epidemiology, biology, prognosis, and strategy for clinical management. The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma, particularly iCCA, has increased globally over the past few decades. Surgical resection remains the mainstay of potentially curative treatment for all three disease subtypes, whereas liver transplantation after neoadjuvant chemoradiation is restricted to a subset of patients with early stage pCCA. For patients with advanced-stage or unresectable disease, locoregional and systemic chemotherapeutics are the primary treatment options. Improvements in external-beam radiation therapy have facilitated the treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. Moreover, advances in comprehensive whole-exome and transcriptome sequencing have defined the genetic landscape of each cholangiocarcinoma subtype. Accordingly, promising molecular targets for precision medicine have been identified, and are being evaluated in clinical trials, including those exploring immunotherapy. Biomarker-driven trials, in which patients are stratified according to anatomical cholangiocarcinoma subtype and genetic aberrations, will be essential in the development of targeted therapies. Targeting the rich tumour stroma of cholangiocarcinoma in conjunction with targeted therapies might also be useful. Herein, we review the evolving developments in the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma.

Cholangiocarcinomas are diverse biliary epithelial tumours involving the intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal biliary tree1. Cholangiocarcinoma is the second most common hepatic malignancy after hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and the overall incidence of cholangiocarcinoma has increased progressively worldwide over the past four decades2–4. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (iCCAs) arise above the second-order bile ducts, whereas the cystic duct is the anatomical point of distinction between perihilar cholangiocarcinomas (pCCAs) and distal cholangiocarcinomas (dCCAs)1. Two histopathological subtypes of the disease are predominant: cancers with cylindrical, mucin-producing glands; and those with cuboidal, non-mucin-producing glands5. However, cholangiocarcinomas commonly have a mixture of these histopathological characteristics. Importantly, substantial differences exist in the molecular characteristics, biology, and management of the anatomical cholangiocarcinoma subtypes1.

Cholangiocarcinomas are aggressive tumours, and most patients have advanced-stage disease at presentation6. Diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma at an early stage remains a challenge owing to its ‘silent’ clinical character (most patients with early stage disease are asymptomatic), difficult to access anatomical location, and highly desmoplastic, paucicellular nature, which limits the sensitivity of cytological and pathological diagnostic approaches. Nonetheless, advanced cytological techniques, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and mutational analysis, have emerged as essential diagnostic modalities7,8.

Surgery is the preferred treatment option for all three disease subtypes, but a minority of patients (approximately 35%) have early stage disease that is amenable to surgical resection with curative intent6. Similarly, only a small subset of carefully selected patients with pCCA are candidates for liver transplantation following neoadjuvant chemoradiation9. Typically, iCCA is considered a formal contraindication for liver transplantation; however, results published in 2016 support liver transplantation as a treatment option for patients with ‘very early’ iCCA10. For patients with advanced-stage or unresectable cholangiocarcinoma, the available systemic therapies are of limited effectiveness: the median overall survival with the current standard-of-care chemotherapy regimen (gemcitabine and cisplatin) is <1 year11. The desmoplastic stroma and genetic heterogeneity both contribute to the resistance of cholangiocarcinoma to therapy; the rich tumour microenvironment fosters potent survival signals and might pose a barrier to the delivery of chemotherapy to the tumour. Advances in genetic profiling and classifications coupled with targeted therapies, radiation therapy, and immunotherapy might help improve survival outcomes of patients with this otherwise devastating malignancy. Herein, we review these advances, focusing on the current state-of-the-art and emerging concepts.

Evolving epidemiology

The anatomical subtypes of cholangiocarcinoma differ geographically in their incidence, presumably reflecting differences in the global distribution of risk factors, in addition to genetic variation. Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma have previously been reviewed elsewhere1,12. Herein, we focus on the secular trends in the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma.

The incidence of iCCA and pCCA/dCCA

The international classification of cholangiocarcinoma does not, unfortunately, distinguish between pCCA and dCCA, and in this section we have aggregated these cancers together as ‘pCCA/dCCA’. Together, pCCA (50–60%) and dCCA (20–30%) account for approximately 80% of all cholangiocarcinomas diagnosed in the USA; the remaining 20% are iCCA13,14. The global incidence of cholangiocarcinoma is highest in northeast Thailand, with age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs) of approximately 100 per 100,000 individuals among men and 50 per 100,000 individuals among women15; in the West, ASIRs range between 0.5–2.0 per 100,000 individuals15–17. The high incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in Thailand and neighbouring areas has been attributed to endemic liver fluke infection, in particular, with Opisthorchis viverrini15. Multiple studies reported that the incidence of iCCA increased by up to 10-fold, while the incidence of pCCA/dCCA decreased at a similar or slightly slower rate, over a 2–3-decade period around the turn of the 20th century in Australia, Japan, the USA, the UK, and across Europe3,4,18–21.

Given the poor prognosis of cholangiocarcinoma, patient mortality should parallel incidence rates. A study using data from the WHO revealed an overall decrease in age-standardized mortality rates (ASMR) among patients with pCCA/dCCA in the first decade of the 21st century across 13 European Union (EU) countries (−6% in males, −17% in females), the USA (−20%, −17%), Japan (−5%, −10%), and Australia (−69%, −28%)22. By contrast, overall ASMRs for iCCA increased by 36.5% in males and 36.2% in females across the 13 EU countries, with the largest increases in Austria, Spain, France, Germany, Italy, and Denmark22. ASMRs for iCCA also rose in the USA (by 11.2% in men and 13.8% in women) and Australia (30.2%, 19.5%), but remained stable in Japan (0.4%, 0.3%)22. Two other studies, however, demonstrated that the incidence of both iCCA and pCCA/dCCA remained stable in Burgundy, France23, and decreased in Denmark24. Furthermore, data from the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries indicate that the incidence of iCCA fell between 1998 and 2003 (annual percentage change (APC) −8% per year), then rose between 2003 and 2009 (APC 6% per year); the incidence of pCCA/dCCA increased between 1998 and 2003 (APC 9% per year), before plateauing from 2003 to 2009 (REF. 25).

Contributing factors

Several factors might explain the inconsistent trends in cholangiocarcinoma epidemiology, including some that are potentially artefactual. Cholangiocarcinoma classification in large epidemiological datasets is problematic, owing to the lack of differentiation between pCCA and dCCA. Furthermore, International Classification of Disease for Oncology (ICD-O;http://codes.iarc.fr/) editions change every few years, but are adopted by countries at different times. For example, the second edition of the ICD-O (ICD-O-2) assigned ‘Klatskin’ tumours (pCCA) a unique histology code, but this was cross-referenced to the topography code for intrahepatic rather than extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Using the ICD-O-3, however, Klatskin tumours can be cross- referenced to either intrahepatic or extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. In the USA, the switch from ICD-O-2 to ICD-O-3 occurred in 2001, whereas in the UK, this switch did not occur until 2008 (REF.26). In a study of cholangiocarcinoma ASIRs between 1990 and 2008 in England and Wales26, a marked increase in iCCA and a decrease in pCCA/dCCA incidences were found, and remained evident after transferring all Klatskin tumours from intrahepatic to extrahepatic codes; however, only 1% of all cholangiocarcinomas were reportedly Klatskin, which cannot be a true reflection of all pCCA cases26. Of note, UK cancer registries reported that if a tumour site is unspecified, most would classify cholangiocarcinoma as intrahepatic26. In the same study26, an analysis of US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data revealed that the ASIR of iCCA rose from 0.6 per 100,000 individuals in 1990 to 0.9 per 100,000 individuals in 2001; that year, concomitant with the uptake of ICD-O-3, the ASIRs for iCCA began to decrease, before plateauing at 0.6 per 100,000 individuals by 2007 (REF. 26). Conversely, ASIRs for pCCA/dCCA remained stable at around 0.8 per 100,000 individuals until 2001, and then began increasing, reaching 1.0 per 100,000 individuals by 2007 (REF. 26). These trends suggest that pCCA, the most-common subtype of cholangiocarcinoma, might have been misclassified as iCCA, the least common subtype, thereby falsely skewing the reported rates of iCCA.

Other studies have highlighted the misclassification of cholangiocarcinoma. Systematic under-reporting of the incidences of pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma was found by examining the concordance between Swedish cancer registries and patient registries: between 1990 and 2009, 44% of cholangiocarcinomas were reported only in the patient registries27. In Sweden, most deaths from liver cancer are classified by the Cancer Register as ‘unspecified’, and evidence indicates that the incidence of HCC is also under-reported28,29. The same classification and reporting issues probably apply to cholangiocarcinomas.

Whereas the incidence of iCCA has increased over the past 2–3 decades, a concomitant decline in the incidence of cancer of unknown primary (CUP) has been observed2. In a prospective, phase II trial involving patients with previously untreated CUP (n = 289)30, molecular tumour profiling enabled determination of the tissue of origin in 98% of patients. Of these, 18% of patients were predicted to have biliary tract cancer30. Hence, the enhanced clinical distinction between CUP and iCCA might be another factor contributing to the apparent increase in iCCA incidence31.

Aside from technical classification issues, and improvements in the accuracy and availability of diagnostic tools, several demographic trends could also be affecting the true incidence of cholangiocarcinoma subtypes, including rising obesity rates and the changing burden of chronic viral hepatitis (which are recognized risk factors for iCCA, as well as for HCC32); with improved antiviral therapy, the contribution of chronic viral hepatitis to the incidence of iCCA will probably decline in the future. Other demographic factors potentially influencing the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma include population migration between different risk areas.

In conclusion, the trends in cholangiocarcinoma incidence are complex and need to be interpreted with caution. Going forward, epidemiological data need to be recorded uniformly and accurately; this responsibility resides with both clinicians and cancer registries.

Standard of care: diagnosis and therapy

iCCA

Diagnosis

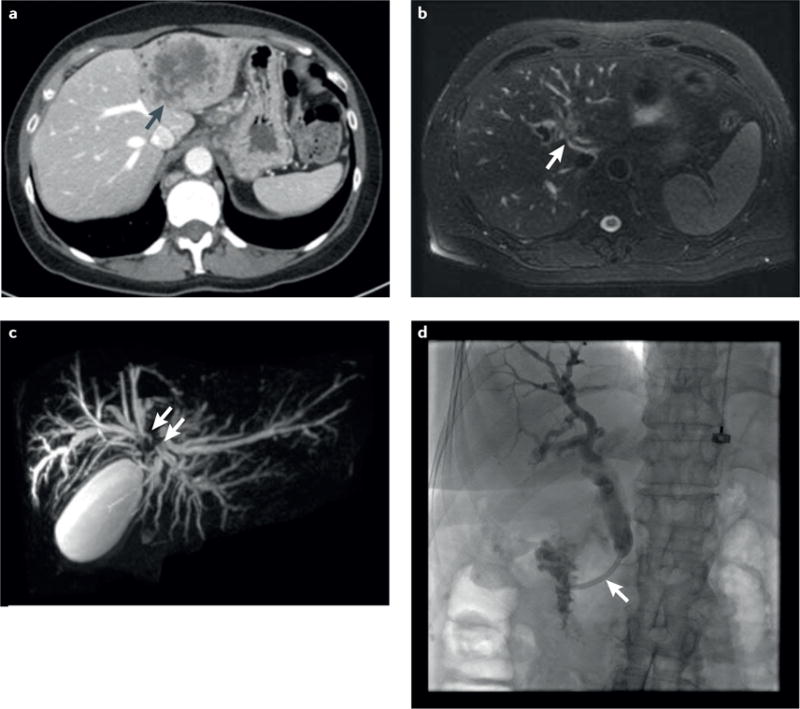

iCCA is typically detected as a hepatic mass lesion, often during routine imaging surveillance for HCC in patients with cirrhosis; in a cirrhotic liver, the differential diagnosis of HCC and iCCA can be difficult. Whereas arterial phase enhancement with subsequent delayed phase washout is diagnostic of HCCs33, dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MRI and CT scanning of iCCA yields an initial rim or peripheral arterial phase-enhancement pattern followed by centripetal enhancement in the delayed phases34,35. CT and MRI have comparable performance in the detection of primary and satellite iCCA lesions, but CT imaging is superior for the detection of vascular enhancement and, thus, assessment of resectability36(FIG. 1). Cancer antigen 19–9 (CA 19–9) is the primary serum biomarker used in the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma37,38, and CA 19–9 levels >1,000 U/ml have been associated with the presence of metastatic disease39. Of note, however, patients who are Lewis-antigen-negative (7% of the general population) have undetectable CA 19–9 levels40. A histopathological assessment of a biopsy specimen is essential for the diagnosis of iCCA.

Figure 1. Illustrative examples of the radiographic modalities used in the visualization of the different anatomical subtypes of cholangiocarcinoma.

a | Axial CT image of a large, left lobe heterogeneous mass with peripheral bile-duct dilatation (black arrow) consistent with an intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA). The pattern of vascular enhancement on CT imaging, with initial rim enhancement followed by centripetal enhancement, helps distinguish iCCA from hepatocellular carcinoma, but does not enable assessment of resectability. b | Axial T2-weighted MRI scan of a circumferential, soft-tissue, perihilar mass (white arrow) consistent with a perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA). c | Coronal magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image of pCCA separating the right and left hepatic ducts (white arrows). d | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography image of a malignant-appearing (‘dominant’) distal stricture (white arrow) consistent with a distal cholangiocarcinoma.

Surgical resection or liver transplantation

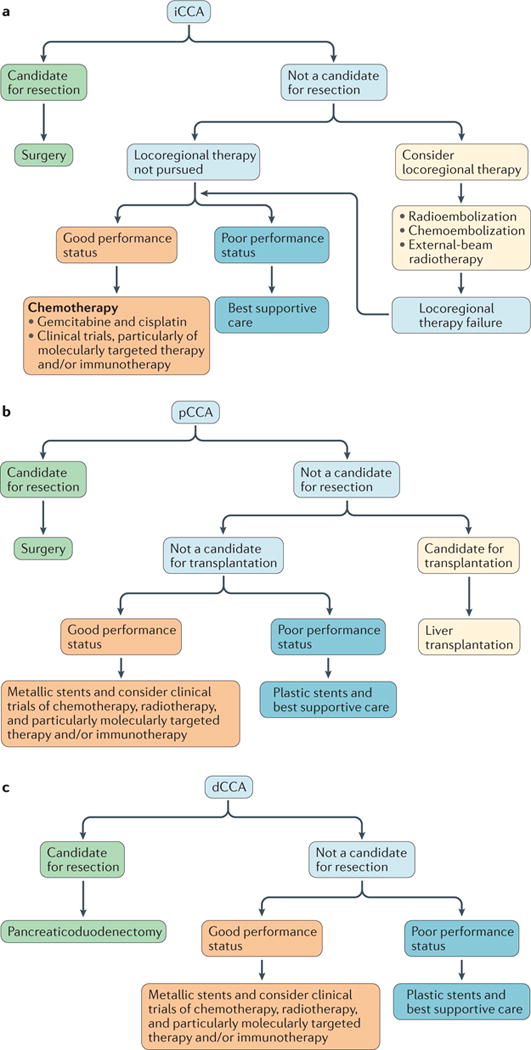

Surgical resection remains the mainstay of potentially curative therapy for iCCA (FIG. 2a), with median disease-free survival (DFS) durations of 12–36 months reported in various patient series41,42. Notably, the median overall survival of patients with R0-resected iCCA was 80 months in one cohort13. Predictors of short DFS durations include large tumour size, the presence of multiple liver lesions, and regional lymph-node involvement42. Cirrhosis is also an independent factor associated with unfavourable survival outcomes in patients with iCCA undergoing surgical resection43. iCCA has conventionally been considered a contraindication for liver transplantation owing to poor survival outcomes and a high risk of recurrence44,45. In 2014, however, a retrospective multicentre study demonstrated an excellent 5-year actuarial survival after liver transplantation of 73% in eight patients with cirrhosis and ‘very early’ iCCA, defined as single tumours ≤2 cm in diameter46. A follow-up study with a larger, international, multicentre cohort of patients found a 5-year survival of 65% in 15 patients with very early iCCA versus 45% in 33 patients with ‘advanced’ iCCA (single tumour >2 cm or multifocal disease)10. These studies indicate that liver transplantation might be an effective treatment option for a subset of cirrhotic patients with early iCCA.

Figure 2. Current clinical management algorithms for adult patients with cholangiocarcinoma.

a | For patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA).b | For those with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA).c | For patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma (dCCA). Patients with unresectable pCCA/dCCA who are not candidates for liver transplantation and have a poor performance status generally have short survival durations; thus, the use of plastic stents is usually sufficient and probably more cost-effective than the use of metallic stents.

Locoregional therapies

Locoregional therapies are a reasonable treatment approach in patients with advanced-stage iCCA (FIG. 2a). In patients with localized, unresectable iCCA, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is considered a safe treatment option and is associated with median overall survival durations of 12–15 months47–49. In one such cohort, TACE with drug-eluting beads resulted in a median overall survival of 11.7 months, compared with 5.7 months with conventional TACE50. Radioembolization using yttrium-90 microspheres is an alternate treatment option for unresectable iCCA, with reasonable effectiveness (median overall survival durations of 11–22 months) and safety51,52. High-dose, conformal external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) has emerged as an acceptable treatment for select patients with localized, unresectable iCCA (see ‘The evolving role of radiation therapy’ section). To date, no randomized controlled trials have compared different forms of locoregional therapy for iCCA. Patients who are not candidates for surgical resection or locoregional therapies should be considered for enrolment in a clinical trial of a targeted therapy (FIG. 2a).

pCCA

Diagnosis

A combination of CT and MRI with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) imaging is used for the detection of pCCA: MRI–MRCP has a higher level of diagnostic accuracy for the detection of biliary neoplastic invasion (FIG. 1), whereas CT enables a better assessment of vascular involvement53,54. The use of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) alone is associated with a high tumour detection rate compared with the use of CT or MRI, with better performance in the detection of dCCA versus pCCA (100% versus 83%, respectively)55. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) during EUS carries a high risk of tumour seeding: among 191 patients with pCCA, 5 of 6 patients (83%) who underwent a transperitoneal primary tumour biopsy developed peritoneal metastases, compared with 14 of 175 (8%) of those who did not undergo a transperitoneal biopsy56. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has an integral role in pCCA management by enabling not only the detection of malignant biliary strictures, but also the acquisition of biliary brushing samples for cytological and genetic assessment.

A number of emerging cytological techniques have potential clinical utility in pCCA diagnosis (BOX 1). Conventional biliary cytology has a high specificity (97%) in the detection of pCCA, but limited sensitivity (43%)57, predominantly because cholangiocarcinomas are desmoplastic, paucicellular tumours potentially located in inaccessible regions of the biliary tree, causing difficulties in adequate specimen retrieval. FISH analyses have improved the diagnostic performance of conventional cytology. Chromosomal instability is a hallmark of cancer, and the diagnostic FISH assay involves the use of fluorescently labelled DNA probes to detect chromosomal aneusomy (gains or losses of chromosomal regions), with FISH polysomy indicating the presence of five or more cells with gains detected for two or more probes. An optimized FISH probe set targeting the 1q21, 7p12, 8q24, and 9p21 loci has been developed, and can detect pancreatobiliary malignancies, including cholangiocarcinoma, with a sensitivity and specificity of 93% and 100%, respectively7. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) for known or candidate oncogenic targets can enhance the diagnostic utility of conventional biliary cytology. In 33 patients with malignant-appearing pancreatobiliary strictures, NGS combined with cytology had a sensitivity of 85% in the detection of high-risk neoplasia or malignancy, compared with 67% for cytology alone58. Moreover, NGS revealed driver mutations in 24 patients, including KRAS, TP53, and_CDKN2A_ aberrations58.

Box 1. Diagnosis of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA).

Various emerging cytological and genetic techniques that can be performed on biliary brush specimens, bile, and serum for the detection of pCCA based on the presence and/or abundance of characteristic molecular markers are listed below.

Cell-based assays on biliary brush specimens

- Conventional cytology, potentially with next-generation sequencing (NGS) of cellular material

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization, particularly with optimized probe sets

Molecular diagnostics on bile

- Analysis of microRNAs (miRNAs) from extracellular vesicles (EVs)

- NGS of cellular material (RNA and DNA)

- Mutational profiling of cell-free DNA (cfDNA)

Biomarkers in the peripheral circulation

- Serum levels of cancer antigen 19–9 (CA 19–9)

- Differentially methylated regions in circulating cfDNA

- Components of serum EVs, such as proteins and miRNAs

The cytological diagnosis of pCCA is not always possible, often necessitating a diagnosis based on clinical criteria (for example, a mass lesion and malignant-appearing stricture with elevated serum CA 19–9 levels); the major differential diagnosis for a perihilar stricture is pCCA versus IgG4 cholangiopathy59. Molecular profiling techniques, however, have the potential to improve cholangiocarcinoma diagnosis. For example, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as promising diagnostic markers (BOX 1). Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are present in many biological fluids, including bile, and participate in intercellular communication; human biliary EVs contain abundant miRNA species60. A panel of miRNAs isolated from EVs in bile had a reported sensitivity of 67% and a specificity of 96% for the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma60. Furthermore, a separate proteomic analysis indicated that greater levels of oncogenic proteins are present in EVs obtained from cultures of human cholangiocarcinoma cells versus those derived from nonmalignant human cholangiocytes61. In addition, Severino et al.62demonstrated that patients with malignant biliary strictures have a significantly higher concentration of EVs in bile than those with nonmalignant strictures (2.4 × 1015 versus 1.6 × 1014 nanoparticles/l in the discovery cohort,P <0.0001; 4.0 × 1015 versus 1.3 × 1014 nanoparticles/l in the verification cohort,P <0.0001). Moreover, these authors identified an EV proteomic signature that can help discriminate malignant from common nonmalignant bile-duct strictures62.

Genomic and molecular advances have increased the clinical utility of circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) or cell-free DNA63. The plasma concentration of ctDNA correlates with tumour size and stage; hence, ‘liquid biopsy’ approaches have the potential to be used for prognostication and disease monitoring in the management of cancer63 (BOX 1). In 69 patients with cholangiocarcinoma (94% with pCCA) and 95 individuals without cancer64, analyses of serum cell-free DNA revealed a panel of four genes that had differentially methylated regions (DMRs) in patients with cholangiocarcinoma (HOXA1, PRKCB,CYP26C1, and PTGDR). This DMR ctDNA panel had a sensitivity and a specificity of 83% and 93%, respectively, in the detection of cholangiocarcinoma64.

Surgical resection or liver transplantation

Surgical resection of pCCA is a potentially curative option for patients without the following exclusion criteria: bilateral involvement of the second-order bile ducts, bilateral or contralateral vascular involvement, presence of metastatic disease, and underlying primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). PSC is associated with underlying chronic parenchymal disease and a field defect that can be eliminated by liver transplantation, but not resection. The presence of regional lymphadenopathy, although not an absolute contraindication for resection, is associated with inferior patient outcomes65. Resection with curative intent often involves lobectomy with bile-duct resection, regional lymphadenectomy, and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy65. Surgical advances, such as extended lobectomy, vascular reconstruction, and techniques to increase remnant liver volume (including portal vein embolization and the associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) procedure), have facilitated the resection of tumours traditionally considered unresectable66–69.

Liver transplantation following neoadjuvant chemoradiation offers the best outcomes for patients with unresectable pCCA; however, only a minority of patients with early stage disease are candidates for this treatment option. Selection criteria — in an otherwise suitable candidate for liver transplantation — includes the presence of an unresectable tumour with a radial diameter of <3 cm, and the absence of intrahepatic or extrahepatic metastatic disease70. As alluded to previously, pCCA arising in the setting of PSC is best treated with liver transplantation regardless of resectability, owing to the field defect associated with this underlying chronic liver disease, which promotes carcinogenesis. Eligible patients typically undergo EBRT with radiosensitizing chemotherapy, brachytherapy, and maintenance oral chemotherapy before liver transplantation9. The 5-year DFS of patients with pCCA who underwent liver transplantation following neoadjuvant therapy was 65% across 12 US transplantation centres9. For patients with pCCA who are not candidates for surgical resection or liver transplantation, consideration should be given to enrolment in a clinical trial, particularly those evaluating targeted therapy (FIG. 2b; Supplementary information S1 (table)).

dCCA

Diagnosis

The same modalities that are used for the diagnosis of pCCA — CT, MRI–MRCP, ERCP, and EUS — are used to diagnose dCCA (FIG. 1). EUS with FNA of the lesion is usually diagnostic in patients with these tumours. The aforementioned molecular approaches to the diagnosis of pCCA might also be useful for the detection of dCCA.

Surgical resection

Surgical resection of dCCA typically entails a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure). In a large series of patients with cholangiocarcinoma undergoing surgical resection13, R0 resection was achieved in 78% of those with dCCA. In this cohort, dCCAs were mainly resected using a Whipple procedure; for smaller tumours, excision of the extrahepatic biliary tree with lymph-node dissection was used13. The 5-year overall survival of patients with dCCA was 23%, and was slightly higher (27%) if R0 resection was achieved (the median survival after R0 resection was 25 months)13. For patients with advanced-stage dCCA not amenable to resection, consideration should be given to enrolment in a clinical trial, potentially involving targeted therapy (FIG. 2c; Supplementary information S1 (table)).

Cytotoxic chemotherapies

The combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin is the current first-line chemotherapy for patients with advanced-stage cholangiocarcinoma not amenable to locoregional and surgical options, irrespective of anatomical disease subtype. Valle et al.11 reported a median survival of 11.7 months with this combination versus 8.1 months with gemcitabine alone; however, almost 40% of this cohort of patients in the UK had gallbladder cancer. Moreover, the 95% CI of the hazard ratio (HR) for death crossed one for the pCCA and dCCA subgroups11. A subsequent meta-analysis71, which incorporated data from the UK study11 and a Japanese study72, among others, reported similar results for the gemcitabine and cisplatin regimen, with a median overall survival of 11.7 months — and 11.1 months in the UK and Japanese study cohorts specifically. These data indicate that, at least for patients with advanced-stage pCCA/dCCA, enrolment in clinical trials of novel therapies could be considered in lieu of treatment with the current standard-of-care chemotherapy regimen (FIG. 2).

In the adjuvant setting, capecitabine has demonstrated efficacy in patients who had undergone surgical resection for cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder cancer: the median overall survival was 51 months in the treatment arm compared with 36 months in the observation arm73. Results of a phase III trial conducted in France, however, demonstrated that adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (GEMOX), initiated 3 months after R0 or R1 resection of biliary tract cancer, did not significantly improve recurrence-free survival compared with placebo (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.58–1.19; _P_= 0.31)74. More evidence is needed to clarify the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of cholangiocarcinoma.

The evolving role of radiation therapy

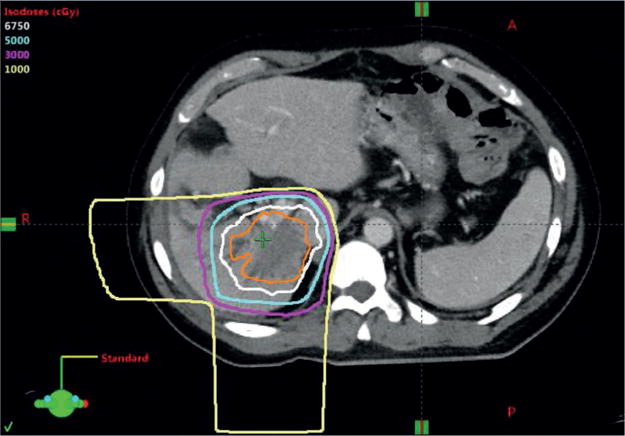

Technological advances have improved the safety and effectiveness of radiation therapy for cholangiocarcinoma75. High-resolution, multiphase helical CT and multiparametric MRI of the liver and biliary tree have enabled more-precise determination of cancer location and the extent of radiotherapy targeting. Moreover, CT-based treatment planning and dose calculation enables accurate estimation of radiation doses delivered to the tumour and nonmalignant tissues76,77. In addition, advanced EBRT techniques, such as 3D conformal radiotherapy (3D–CRT) and intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), are used to deliver conformal radiation to the target while sparing nonmalignant tissues. Alternatively, charged-particle (proton or carbon) beams have a more-favourable physical dose-deposition profile than that of conventional X-ray beams, which might yield advantages in sparing nonmalignant tissues78 (FIG. 3). Consequently, accelerated and hypofractionated regimens, including stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), have been used to deliver high-dose, ablative EBRT to patients with cholangiocarcinoma78–80. Image-guided, high-dose-rate brachytherapy can also be used as primary treatment or to provide a radiation boost for selected patients with localized disease81,82. Together, these technological advances might enable escalation of the radiotherapy dose to biliary tumours and/or improved protection of nonmalignant tissues, thus improving the therapeutic ratio for radiotherapy in the treatment of cholangiocarcinoma.

Figure 3. Proton radiotherapy of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA).

Proton-beam radiotherapy plan for a patient with localized, unresectable iCCA, with a total radiation dose of 6,750 cGy delivered in 15 fractions over 3 weeks. The orange line depicts the tumour. The white, cyan, magenta, and yellow lines represent the 6,750, 5,000, 3,000, and 1,000 cGy isodose lines, respectively. Radiation is delivered in two beams from the right lateral (R) and posterior (P) directions (as indicated by the 1,000 cGy isodose lines). Proton beams have no ‘exit dose’ deposition, which for this patient, enabled complete sparing of the left lobe of the liver, stomach, and bowel from radiation exposure.

For patients with resected cholangiocarcinoma, data from retrospective studies indicate a benefit from postoperative EBRT with concurrent chemotherapy, especially in patients with lymph-node-positive or resection-margin-positive disease83–85. Results of a multi-institutional, single-arm phase II study86demonstrated the safety and promising efficacy of adjuvant therapy consisting of gemcitabine plus capecitabine followed by conformal EBRT with concurrent capecitabine for patients with resected pCCA/dCCA and gallbladder cancer. The majority of patients (81%) received IMRT86. In the 54 patients with resected pCCA/dCCA, the 2-year overall survival and local control rates were 68% and 87%, respectively; no differences in overall survival or DFS were observed between patients with R0 versus R1 resection86. These results support the need for high-quality studies of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy for patients with resected cholangiocarcinoma.

Studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of high-dose, conformal EBRT for patients with localized, unresectable iCCA78,80. In a single-institution retrospective analysis80 involving 79 patients with localized, unresectable iCCA treated with high-dose, conformal EBRT (35–100 Gy, median 58.05 Gy, in 3–30 fractions), the median overall survival was 30 months. In a multi-institutional single-arm phase II study78, 37 patients with localized, unresectable iCCA received hypofractionated proton-beam therapy with a median dose of 58.05 Gy in 15 fractions delivered daily over 3 weeks. The median and 2-year overall survival was 22.5 months and 46.5%, respectively; the 2-year local control rate was 94%, and most recurrences occurred at extrahepatic sites78. These outcomes formed the basis for an ongoing multi-institutional phase III trial to assess the role of high-dose, conformal EBRT after initial gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy (NCT02200042).

For patients with localized, unresectable pCCA/ dCCA, the role of radiotherapy remains unclear. Retrospective analyses of large observational cohorts suggest a modest benefit from radiotherapy, although these analyses are hampered by considerable inherent biases87,88. By contrast, in single-institution retrospective series89–91, long-term DFS has been reported for a small subset of patients treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy. Randomized trials are needed to better define the relative roles of contemporary treatments for localized, unresectable pCCA/dCCA, including systemic therapies and modern locoregional radiotherapy (FIG. 2).

Emerging molecularly-directed therapies

Molecular pathogenesis

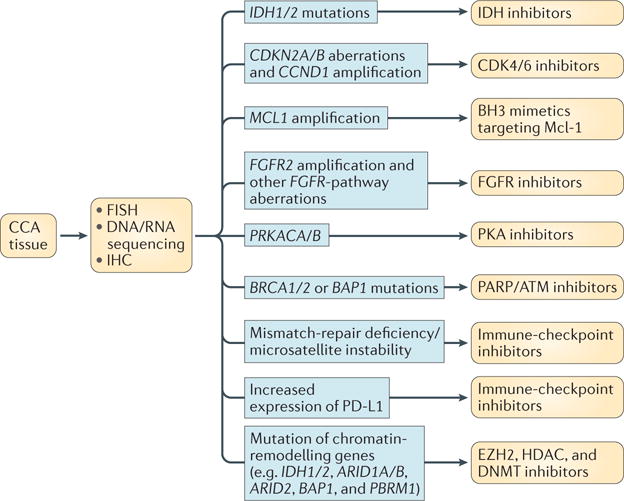

The marked intertumoural and intratumoural heterogeneity of cholangiocarcinoma has contributed to the lack of effective targeted therapies for this deadly disease. Moreover, in most clinical trials, investigators have grouped together patients with different subtypes of the disease, under the broad definition of ‘biliary tract cancer’, rather than stratifying patients according to the presence of relevant oncogenic drivers. Molecular profiling studies have better delineated the genomic and transcriptomic landscape of each cholangiocarcinoma subtype (FIG. 4). Comprehensive whole-exome and transcriptome sequencing in a large cohort of 260 patients with biliary tract cancers, including 145 with iCCA, 86 with pCCA/dCCA, and 29 with gallbladder cancer, revealed potentially targetable genetic driver alterations in ~40% of patients92. In this study by Nakamura et al.92, the repertoire of genetic alterations varied across the different cholangiocarcinoma subtypes. For example, recurrent mutations in IDH1, IDH2,FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3,EPHA2, and BAP1 were noted predominantly in iCCAs, whereas ARID1B, ELF3,PBRM1, PRKACA, and PRKACB_mutations occurred preferentially in pCCA/dCCA92. The characteristic genomic signatures associated with the different genetic aberrations in each disease subtype contribute to their distinct biological behaviour. Notably, fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) fusions that result in ligand-independent activation of this receptor-tyrosine kinase were identified exclusively in patients with iCCA92, consistent with prior observations93–97. Novel gene fusions involving PRKACA or PRKACB, which encode catalytic subunits of protein kinase A, were detected only in pCCA/dCCA92. The discovery of these aberrations is important because gene fusions are often targetable driver events. ELF3 was another novel candidate driver gene identified in this study92, primarily in pCCA/dCCA. Inactivating mutations in_ELF3 have since been identified in dCCA samples in two other genomic analyses98,99; thus, the ETS-related transcription factor ELF3 probably acts as a tumour suppressor in cholangiocarcinoma. In keeping with data reported by Nakamura et al.92, targeted sequencing of selected cancer-related genes in a study of 28 iCCA samples revealed potentially actionable alterations in IDH1,IDH2, FGFR2, KRAS, PTEN, and CDKN2A, among others95. The most common alterations involved_ARID1A_, IDH1, IDH2, and_TP53_ (each identified in 36% of the tumours), as well as MCL1 (amplified in 21% of tumours)95.

Figure 4. Evolving molecular stratification of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) and therapeutic implications.

Emerging and conventional analytical techniques, such as RNA and/or DNA sequencing, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and immunohistochemistry (IHC), can be used for the detection of molecular aberrations in CCA tissue obtained via biopsy or surgery. The listed molecular alterations represent potential therapeutic targets in CCA. ATM, ataxia-telangiectasia mutated; BH3, BCL-2 homology domain 3; CDK4/6, cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; HDAC, histone deacetylase; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; Mcl-1, induced myeloid leukaemia cell differentiation protein Mcl-1; PARP, poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase; PD-L1, programmed cell death 1 ligand 1; PKA, protein kinase A.

Discrete carcinogenic exposures might induce distinct somatic alterations in patients with cholangiocarcinomas, as highlighted by whole-exome sequencing data from 108 liver-fluke-related and 101 non-liver-fluke-related tumours100: non-liver-fluke-related iCCAs had a higher prevalence of mutations in_IDH1_ or IDH2 (encoding isocitrate dehydrogenase [NADP] cytoplasmic (IDH1) and mitochondrial (IDH2)), and loss-of-function mutations in the tumour-suppressor gene_BAP1_ (encoding the epigenetic regulator BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP1))100. By contrast, mutations in the tumour-suppressor gene TP53 were a more frequent occurrence in liver-fluke-related cholangiocarcinomas100. These findings suggest that distinct causative aetiologies determine the mutational landscape of cholangiocarcinoma.

An integrated genomic analysis of predominantly liver-fluke-negative, hepatitis-negative iCCAs by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) investigators101identified inactivating mutations in tumour-suppressor genes, including_ARID1A_, ARID1B, BAP1,TP53, and PTEN, and gain-of-function mutations in the oncogenes IDH1, IDH2,BRAF, and KRAS — recapitulating the aforementioned findings. Recurrent focal losses of CDKN2A, encoding p16INK4A, which inhibits the cyclin-dependent kinases CDK4 and CDK6 (as well as p14ARF, which also indirectly inhibits CDK4 and CDK6), were observed in 47% of the tumours101 — a substantially higher proportion than reported previously (7–15%)95,102. Consistent with prior reports92,95,103,104, mutations in IDH1 or_IDH2_ were detected exclusively in iCCA, and were highly enriched in a novel, distinct molecular iCCA subtype identified through cluster-of-cluster analysis of gene-expression, DNA-methylation, and copy-number profiles101. Interestingly, this subtype was associated with high and low levels of mitochondrial and chromatin-modifier gene expression, respectively, including probable epigenetic silencing of ARID1A101, which encodes a subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodelling complex. Two other molecular subtypes of iCCA were defined, one comprising tumours enriched for BAP1 mutations and/or FGFR2 fusions, and the other enriched for_CCND1_ amplification101.

Molecularly targeted therapies

Receptor-tyrosine-kinase inhibitors

Several selective and nonselective small-molecule inhibitors of FGFRs are currently being investigated in early phase clinical trials involving patients with advanced-stage solid-organ malignancies, including cholangiocarcinoma (Supplementary information S1 (table)). The pan-FGFR inhibitor NVP-BGJ398, having demonstrated potential in preclinical models of cholangiocarcinoma105, is currently being investigated in a phase II study in patients with advanced-stage cholangiocarcinoma harbouring_FGFR_ alterations (NCT02150967). An interim analysis of data from this study indicated that NVP-BGJ398 has impressive antitumour activity, with a disease-control rate of 82%, and a manageable safety profile106. Erdafitinib is another orally active, pan-FGFR inhibitor107, and is being investigated in clinical trials. In a phase I dose-escalation study (NCT01703481), erdafitinib had a manageable safety profile at doses associated with clinical responses; among 23 response-evaluable patients with solid tumours harbouring FGFR-pathway alterations, four patients had a confirmed response to treatment with erdafitinib, one had an unconfirmed partial response, and 16 had stable disease108. A phase II trial of erdafitinib is currently ongoing (NCT02699606). Other FGFR-selective inhibitors currently being evaluated in patients with advanced-stage solid-organ malignancies include derazantinib (NCT01752920), TAS-120 (NCT02052778), Debio 1347 (NCT01948297), and INCB054828 (NCT02924376, NCT02393248). Ponatinib, a nonselective tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, has shown promising efficacy in patients with advanced-stage iCCA with _FGFR2_fusions93, and is currently being evaluated in a phase II trial in this population (NCT02265341; Supplementary information S1 (table)).

Inhibition of heat-shock protein 90 (HSP90) is an alternative to direct FGFR-kinase inhibition in _FGFR2_-fusion-driven cancers. HSP90 is a molecular chaperone required for essential cellular housekeeping functions, such as protein folding and mediating post-translational protein homeostasis, as well as for maintenance of oncoprotein stability109. As proof of this concept, the selective HSP90 inhibitor ganetespib induced loss of fusion protein expression, inhibition of oncogenic signalling, and consequent cancer-cell cytotoxicity in FGFR-fusion-driven bladder cancer110. Moreover, ganetespib had a synergistic combinatorial benefit with NVP-BGJ398 in preclinical models, with a change in average tumour volume relative to the vehicle-treated animals of −23% for ganetespib alone, −20% for NVP-BGJ398 alone, and −66% for the combination110.

ROS1 kinase fusion proteins have an oncogenic role in several malignancies, including cholangiocarcinoma; an immunoaffinity profiling study revealed FIG–ROS1 gene fusions in 2 of 23 patients with cholangiocarcinoma (8.7%)111. In a mouse orthotopic allograft model, expression of the FIG–ROS1 fusion accelerated iCCA tumour development and inactivation of this fusion had the converse effect, indicating that ROS1 fusions are potent oncoproteins and a potential therapeutic target in cholangiocarcinoma112. Of note, a gene fusion involving the ROS1-related kinase ALK (EML4–ALK) has also been detected in a patient with iCCA92. The ALK and ROS1 inhibitor ceritinib is currently being evaluated in two phase II trials in patients with ROS1-positive or ALK-positive advanced-stage pCCA or iCCA (NCT02374489; Supplementary information S1 (table)), or advanced-stage gastrointestinal malignancies, including cholangiocarcinoma (NCT02638909). Entrectinib, a selective tyrosine-kinase inhibitor with activity against ROS1 and ALK (as well as TRKA, TRKB, and TRKC), is also being evaluated in a phase II study involving patients with advanced-stage solid tumours harbouring _ROS1_or ALK fusions (NCT02568267).

Activating mutations of the proto-oncogene KRAS are a frequent occurrence (11–25%, depending on disease subtype) in cholangiocarcinomas92,95,101, and are associated with unfavourable progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival95,102,113.KRAS activation upregulates signalling via downstream pathways, including the RAF–MEK–ERK (MAPK) pathway. Accordingly, KRAS_-mutant cholangiocarcinomas might be amenable to MEK inhibition. Results of a phase II study of selumetinib in patients with metastatic biliary cancer demonstrated a median PFS of 3.7 months and a median overall survival of 9.8 months114. In a subsequent phase Ib study in patients with advanced-stage biliary tract cancer, the combination of selumetinib, gemcitabine, and cisplatin conferred a median PFS of 6.4 months115. Neither of these studies involved patient selection based on_KRAS mutation status. BRAF mutations can also occur in cholangiocarcinoma (predominantly in iCCAs), albeit at a low frequency (3–5%)102,113,116. In eight patients with_BRAF_ V600-mutated cholangiocarcinoma, treatment with the oral BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib led to a partial response in one patient117.

Tyrosine-kinase signalling via the hepatocyte growth factor receptor MET is essential to a myriad of cellular processes required for cell survival. An integrated molecular analysis identified a proliferation class of iCCAs (62% of all iCCAs) characterized by activation of MET, EGFR, and MAPK signalling118; however, the results of early phase clinical trials of MET or EGFR inhibitors in patients with cholangiocarcinoma have been disappointing. A phase I study119 of the MET inhibitor tivantinib in combination with gemcitabine in patients with solid tumours, including cholangiocarcinoma, demonstrated partial responses and stable disease in 20% and 46% of patients, respectively; one patient with cholangiocarcinoma had a partial response. Cabozantinib, a multikinase inhibitor with activity against MET and VEGFR2, had limited activity (median PFS 1.8 months) and substantial toxicity in unselected patients with cholangiocarcinoma120. Moreover, MET expression did not correlate with patient outcomes in this study120. The combination of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor with activity against VEGFR and RAF family kinases, and the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib had disappointing clinical activity against advanced-stage biliary tract cancer121. In fact, this phase II study121 was terminated early owing to suboptimal PFS and overall survival. A phase II trial of the anti-HER2 antibody–drug conjugate trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in patients with HER2-positive advanced-stage malignancies, including cholangiocarcinoma, is currently ongoing (NCT02999672; Supplementary information S1 (table)). Umbrella and basket trial designs could facilitate the testing of these agents in what are essentially very rare molecular subtypes of cholangiocarcinoma.

Therapeutics targeting epigenetic alterations

The aforementioned genetic profiling studies have revealed that mutations affecting epigenetic regulators, such as IDH1, IDH2, BAP1, and ARID1A, are common in cholangiocarcinomas92,95,100,101; thus, epigenetic therapies are a promising endeavour122. Small-molecule inhibitors of mutant IDH1 or IDH2 have shown favourable efficacy in preclinical studies123,124; consequently, orally bioavailable inhibitors have entered clinical trials. Preliminary results from a phase I trial of AG-120 (NCT02073994; Supplementary information S1 (table)), an inhibitor of mutant IDH1, in a dose-escalation and dose-expansion cohort of patients with cholangiocarcinoma harbouring IDH1 mutations indicated a favourable safety profile125. Moreover, among 20 response-evaluable patients with cholangiocarcinoma treated with AG-120 in this study125, one had a partial response and 11 had stable disease. ClarIDHy, a global, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial involving 186 patients with_IDH1_-mutant cholangiocarcinoma, is currently underway (NCT02989857). Enasidenib, a first-in-class, oral, selective inhibitor of mutant IDH2, has demonstrated activity in preclinical models of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)126–128. Consequently, enasidenib has been granted priority review by the FDA for patients with AML harbouring an IDH2 mutation. Enasidenib is currently being investigated in a multicentre phase I/II trial in patients with _IDH2_-mutant advanced-stage solid tumours, including iCCA (NCT02273739; Supplementary information S1 (table)).

Of note, _IDH_-mutant iCCA cells are dependent on SRC activity for survival; the SRC kinase inhibitor dasatinib induced tumour regression of mouse _IDH_-mutant tumour xenografts129. This preclinical work provided the basis for a phase II trial of dasatinib in patients with advanced-stage _IDH_-mutant iCCA (NCT02428855; Supplementary information S1 (table)). In addition, the TCGA analysis suggests that_IDH_-mutant cholangiocarcinomas probably have epigenetic silencing of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodelling complex protein ARID1A101. In fact, mutation or silencing of SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling subunits, including ARID1A, ARID1B, ARID2, BAP1, PBRM1, SMARCA2, SMARCA4, and SMARCAD1, is a frequent occurrence in cholangiocarcinomas (and other cancers)92,101,130. Notably, tumours with mutations in genes encoding members of the SWI/SNF complex are dependent on the histone methyltransferase activity of EZH2 and, hence, are potentially susceptible to EZH2 inhibitors130. Indeed, EZH2 is typically overexpressed in cholangiocarcinomas, and EZH2 upregulation is correlated with a poor prognosis131,132. Furthermore, preclinical data indicate that EZH2 inhibition, in combination with gemcitabine, synergistically inhibits cholangiocarcinoma- cell proliferation133. Several active clinical trials are investigating EZH2 inhibitors, such as tazemetostat, but primarily in patients with haematopoietic or rhabdoid tumours. Trials of such agents in patients with cholangiocarcinoma are warranted.

The recurrent, inactivating mutations in chromatin regulators, including BAP1, ARID1A,ARID1B, ARID2, PBRM1, SMARCA2, SMARCA4, and_SMARCAD1_, support the notion that cholangiocarcinoma has an epigenetically-inclined mutational spectrum92,122,134,135. Loss of expression of ARID1A and PBRM1 seems to be a late event in cholangiocarcinoma carcinogenesis136,137. Several small-molecule inhibitors targeting chromatin-remodelling proteins are under investigation in preclinical and clinical studies of cholangiocarcinoma. These agents include histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, such as vorinostat, romidepsin, and valproic acid, and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors, including azacitidine and decitabine138–142. Results of a phase I/II study of valproic acid in 12 patients with advanced-stage pancreaticobiliary tract cancers indicate promising antitumour activity, with one patient achieving a partial response, 10 having stable disease, and one having progressive disease143.

Novel potential targeted therapies

Mesothelin, a cell-surface protein expressed in nonmalignant mesothelial cells, is often aberrantly expressed in cholangiocarcinomas, and is associated with advanced-stage and metastatic disease, and unfavourable overall survival144,145. Thus, this protein is an attractive target for therapy. Anetumab ravtansine, an anti-mesothelin antibody–drug conjugate, is being tested in a phase I trial open for enrolment of patients with advanced-stage cholangiocarcinoma with aberrant mesothelin expression (NCT03102320; Supplementary information S1 (table)).

The recurrent focal losses of CDKN2A, a gene encoding the proteins p16INK4A and p14ARF that are essential negative regulators of cell-cycle progression92,95,101, highlight the potential of CDK4/6 inhibitors, such as ribociclib and palbociclib, in the treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. These agents are approved treatments for breast cancer, and are in clinical trials for a range of other solid-organ malignancies (NCT03065062, NCT02022982), although the efficacy of these agents remains to be evaluated in patients with cholangiocarcinoma.

Somatic mutations of the tumour-suppressor genes_BRCA1_ and BRCA2 have been reported in cholangiocarcinomas92,102._BRCA_-mutated tumours are often sensitive to poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase (PARP) inhibition. Accordingly, in a retrospective clinical analysis in patients with_BRCA_-mutated cholangiocarcinoma (_n_= 18), one of the four patients who received PARP inhibitors had a sustained disease response with a PFS duration of 42.6 months146. Although PARP inhibitors and inhibitors of ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM), another DNA-repair protein, are currently being evaluated in multiple clinical trials for _BRCA_-mutated breast cancer, they have yet to be prospectively evaluated in patients with cholangiocarcinoma. A phase II trial of the PARP inhibitor niraparib is, however, planned in patients with advanced-stage malignancies, including cholangiocarcinoma, and with known mutations in BAP1 and other DNA double-strand break repair pathway genes — excluding, for an unspecified reason,BRCA1/2 mutations (NCT03207347; Supplementary information S1 (table)).

Immunotherapy for cholangiocarcinoma

Immunotherapy in oncology

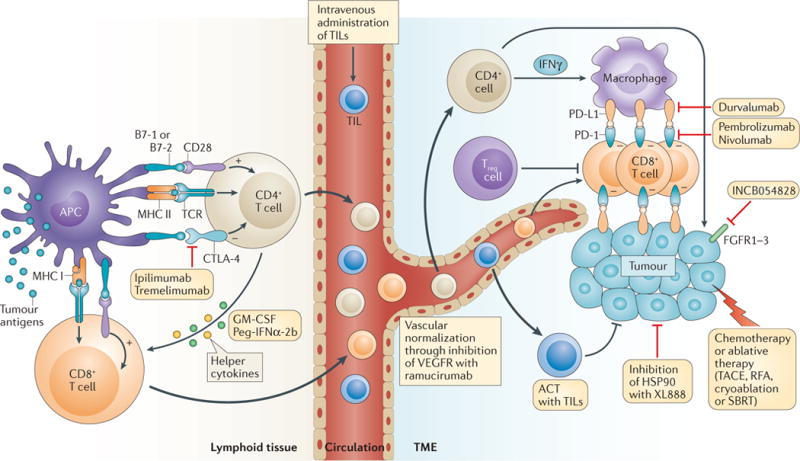

The immune system holds the remarkable potential to recognize and destroy aberrant cancer cells, but is regulated by a complex network of immune checkpoints that prevent uncontrolled immune activation. Cancers harness several mechanisms of immune escape to restrain or evade antitumour immune responses, including modulation of the local tumour microenvironment to create an immunosuppressive milieu; expression of immune-checkpoint proteins, such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1); and loss of MHC expression. The exact mechanisms underlying the immune escape of cholangiocarcinomas remain to be elucidated. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors, antibodies that block the inhibitory interactions between CTLA-4 or PD-1 and their cognate ligands (FIG. 5), have demonstrated robust and durable antitumour activity in subsets of patients across a variety of tumour types, coupled with low rates of immune-mediated toxicity147. Indeed, various immune-checkpoint inhibitors have now been approved for use in the treatment of several malignancies. Ongoing studies of these agents, combination therapies, and novel adoptive-cell therapies148 show great promise to identify novel indications, improve upon the current response rates, refine treatment selection and sequencing, and address therapy resistance.

Figure 5. Biological rationale for the ongoing clinical trials of immunotherapies for cholangiocarcinoma.

The mechanisms of action or targets of the immunotherapy combinations currently being tested in the ongoing trials listed in TABLE 1 are represented schematically. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) transmits inhibitory signals that limit T-cell priming by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells, in lymphoid organs, which can restrict responses to tumour antigens; thus, blockade of this inhibitory immune-checkpoint protein using the monoclonal antibodies ipilimumab or tremelimumab can enhance the activation of T cells with the capacity to recognize tumour cells. Similarly, programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) is an inhibitory immune-checkpoint protein commonly expressed by tumour cells and immune cells in the tumour microenvironment (TME). Antibodies targeting PD-L1, such as durvalumab, or its receptor programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), such as pembrolizumab or nivolumab, can inhibit immunosuppressive signalling in T cells capable of recognizing tumour cells, potentiating anticancer immune responses. In combination with immune-checkpoint inhibition, intravenous adoptive transfer of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) isolated from the TME and expanded ex vivo might enhance anticancer immunity. Alternatively, targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) with the monoclonal antibody ramucirumab might enhance T-cell recruitment into the TME, as a result of normalization of the dysfunctional tumour vasculature, and can also have direct, beneficial immunological effects, for example, on tumour-associated macrophages. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors are also being combined with helper cytokines that might potentiate anticancer immunity, such as granulocyte- macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and pegylated IFNα-2b (Peg-IFNα-2b), as well as small-molecular inhibitors of targets relevant to cholangiocarcinoma, such as fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR1–3) and heat-shock protein 90 (HSP90). ACT, adoptive cell therapy; MHC I, major histocompatibility complex class I; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TCR, T-cell receptor; Treg cell, regulatory T cell.

Rationale for and risks of immunotherapy in cholangiocarcinoma

In cholangiocarcinoma, a number of clinical and epidemiological factors might determine both the efficacy, and the potential risks associated with immunotherapy. A number of chronic infections, such as liver-fluke disease, viral hepatitis B and C, and bacterial pyogenic cholangitis, are established risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma1,149. Notably, immune- checkpoint inhibitors and other immunotherapies have shown promising efficacy in other tumours commonly associated with viral infections, such as head and neck cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, Merkel-cell carcinoma, and HCC150, and this relationship is thought to be mediated, in part, by the presentation of non-self or neoantigens associated with viral infections150–152. Notably, transcriptome sequencing and clustering of gene-expression profiles revealed a subgroup of patients with cholangiocarcinomas with a high mutational load, resulting in abundant tumour-specific neoantigens, and enrichment for expression of immune-related genes, including genes encoding inhibitory immune-checkpoint proteins92. Interestingly, this patient subgroup had the poorest prognosis92. These findings support the hypothesis that some patients with cholangiocarcinoma might benefit from immune-checkpoint inhibition to ‘release the brake’ on an existing anticancer immune response.

Indeed, a substantial proportion of cholangiocarcinomas are surrounded by a reactive tumour stroma, populated by host cells including cancer-associated fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells, including tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs)153,154. These stromal elements produce soluble factors including various interleukins, growth factors, and cytokines, which in turn can promote tumour-cell proliferation, survival, and invasiveness, and modulate anticancer immune responses. In a small retrospective study involving 39 patients with cholangiocarcinoma, high numbers of alternatively activated, ‘M2-like’ TAMs, which are generally considered to be immunosuppressive, were associated with unfavourable disease-free survival155. Thus, targeting stromal cells, such as immunosuppressive TAMs or cancer-associated fibroblasts156–158, might prove to be a beneficial therapeutic strategy, particularly in combination with immunotherapy (FIG. 5; TABLE 1).

Table 1.

Selected immunotherapy clinical trials for cholangiocarcinoma

| Immunotherapy approach | Trial description | Key eligibility criteria | ClinicalTrials.gov reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy | |||

| Pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 antibody) | Single-arm, open-label phase II trial; single-centre, single-arm, open-label, phase II trial | Advanced-stage CCA, with disease progression after first-line therapy, amenable to tumour-tissue sampling; advanced-stage solid tumours, including CCA, amenable to tumour-tissue sampling | NCT03110328; NCT02628067 |

| Nivolumab (anti-PD-1 antibody) | Single-arm, open-label, phase II trial | Advanced-stage CCA, with disease progression after systemic therapy (no more than two prior lines of systemic therapy) | NCT02829918 |

| Durvalumab (anti-PD-L1 antibody) | Multicentre, open-label, phase I trial | Advanced-stage solid tumours, including CCA, refractory to standard therapy, with at least one radiographically measurable lesion | NCT01938612 |

| Dual checkpoint inhibition | |||

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4 antibody) | Multicentre, randomized, phase II trial; single-arm, open-label, phase II trial | Advanced-stage CCA and radiographically measurable disease; advanced-stage rare tumours, including CCA, with tumour progression after standard systemic therapy | NCT03101566; NCT02834013 |

| Durvalumab + tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4 antibody) | Multicentre, open-label, phase I trial | Advanced-stage solid tumours, including CCA | NCT01938612 |

| Checkpoint inhibition plus microenvironmental targeting | |||

| Pembrolizumab + GM-CSF | Randomized, open-label, phase II trial | Advanced-stage CCA | NCT02703714 |

| Pembrolizumab + Peg-IFNα-2b | Multicentre, single-arm, open-label, phase II trial | Advanced-stage CCA, with tumour progression after prior systemic therapy | NCT02982720 |

| Pembrolizumab + ramucirumab (anti-VEGFR2 antibody) | Multicentre, open-label, phase I trial | Advanced-stage solid tumours, including CCA, with tumour progression after one or two prior systemic therapies, and with availability of tumour tissue for biomarker analysis | NCT02443324 |

| Checkpoint inhibition plus ablative local therapy | |||

| Tremelimumab+TACE, RFA, cryoablation, or SBRT | Open-label, phase I trial | Advanced-stage liver cancer, including CCA, after at least one line of systemic therapy | NCT01853618 |

| Durvalumab + tremelimumab + TACE, RFA, or cryoablation | Open-label, phase I/II trial | Advanced-stage liver cancer, including CCA, with at least two tumour lesions | NCT02821754 |

| Checkpoint inhibition plus chemotherapy | |||

| Pembrolizumab + mFOLFOX6 regimen | Open-label, phase I trial | Advanced-stage gastrointestinal cancers, including CCA, amenable tumour-tissue sampling | NCT02268825 |

| Pembrolizumab + capecitabine- oxaliplatin | Open-label, phase II trial | Advanced-stage CCA, with at least one focus of metastatic disease amenable to pretreatment and on-treatment biopsies | NCT03111732 |

| Nivolumab + gemcitabine–cisplatin | Multicentre, randomized, open-label, phase II trial | Advanced-stage CCA, with least one radiographically measurable focus of disease | NCT03101566 |

| Durvalumab + tremelimumab + gemcitabine–cisplatin | Open-label, phase II trial | Advanced-stage CCA, with at least one measurable lesion | NCT03046862 |

| Checkpoint inhibition plus molecularly targeted therapy | |||

| Pembrolizumab + INCB054828 (FGFR1–3 inhibitor) | Open-label, phase I/II trial | Advanced-stage solid tumours, including CCA, with genetic alterations in FGF or_FGFR_ genes | NCT02393248 |

| Pembrolizumab + XL888 (HSP90 inhibitor) | Open-label, phase Ib trial | Advanced-stage gastrointestinal malignancies, including CCA, after failure of at least one prior therapy | NCT03095781 |

| Checkpoint inhibition plus adoptive cell therapy | |||

| Pembrolizumab + tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes | Open-label, phase II trial | Advanced-stage solid tumours, including CCA, refractory to standard therapy | NCT01174121 |

Prevalent hepatic dysfunction and the propensity for biliary obstruction in patients with cholangiocarcinoma is associated with high rates of adverse events in studies of cytotoxic therapies11, and raises concerns regarding an increased risk of immune-mediated hepatobiliary toxicity, such as cholestasis or hepatitis, with immune-checkpoint inhibition. Reassuringly, in the phase I/II CheckMate 040 trial159, the incidence of grade 3 or 4 immune-mediated transaminase elevation among 214 patients with HCC who received the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab was approximately 4% (similar to the rates reported for patients with other tumour types), without any reported treatment-related hepatic decompensation. Autoimmune diseases, such as PSC and inflammatory bowel disease, are also known risk factors in a subset of patients with cholangiocarcinoma, raising additional concerns regarding the risk of flares in pre-existing colitis or biliary tract disease with the use of immune-activating therapies in this population. Of note, patients with underlying autoimmune disease have typically been excluded from clinical trials of immunotherapies; thus, the safety of such treatments in this subset of patients with cholangiocarcinoma remains uncertain.

Candidate biomarkers of response to immunotherapy

Many candidate biomarkers of a response to immune-checkpoint inhibition have emerged from studies relating to a range of tumour types. The most-studied biomarker to date is the PD-1 ligand, PD-L1; any expression of PD-L1 on tumour cells, and/or higher levels of tumour PD-L1 expression have both been associated with sensitivity to immune-checkpoint- inhibitor monotherapy in some tumour types, including melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), but with conflicting results in other diseases160–162. In studies of small numbers of cholangiocarcinoma tumour samples (n = 54–99), PD-L1 expression has been reported in 9–72% of specimens163–165, and on 46–63% of immune cells within the tumour microenvironment164,165. These data indicate that a substantial proportion of cholangiocarcinomas might be amenable to therapy with PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors. Further investigation of PD-L1 as a biomarker for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies is required in order to understand the effects of important covariates, including tumour-cell versus immune-cell expression, primary versus metastatic lesion sampling, prior treatment exposure, and concurrent therapies, as well as the specific assay and cut-off points used.

Certain tumour genetic aberrations have also been associated with a likelihood of response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors, which might relate to the expression of neoantigens capable of eliciting an antitumour T-cell response. One example is the presence of tumour DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency and/or microsatellite instability (MSI), which is associated with high rates and durability of responses to immune-checkpoint blockade across multiple tumour types166,167. Indeed, the anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic MMR-deficient and/or MSI-high solid tumours that progressed after prior therapy (when no satisfactory alternative treatment is available), independent of histology — which would include those with cholangiocarcinoma (https://www.fda.gov/drugs/informationondrugs/approveddrugs/ucm279174.htm). Notably, MMR deficiency has been reported to occur in 5–10% of cholangiocarcinomas168. In addition to MMR deficiency, the cumulative tumour mutational burden has been correlated with responsiveness to immune-checkpoint inhibitors in some cancers, including melanoma, NSCLC, and urothelial carcinoma169–171. In a whole-exome-sequencing study of 231 cholangiocarcinoma tumour samples92, a median of 39 and 35 somatic nonsynonymous mutations were identified in intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas, respectively; overall, ~6% of the cholangiocarcinomas had evidence of hypermutation (mutation rates of >11.13 per megabase; median number of 641 nonsilent mutations), with concurrent MMR deficiency and/or MSI detected in about 36% of these hypermutated tumours92. For comparison, in patients with NSCLC who derived durable clinical benefit from pembrolizumab (partial or stable response lasting >6 months), the median number of nonsynonymous mutations was 302 (REF. 169). These data suggest that immune-checkpoint blockade and immune-modulating therapies could be promising options for the subgroup of patients with cholangiocarcinomas harbouring high mutational loads.

Emerging clinical data from immune-targeted therapies in cholangiocarcinoma

At present, the clinical data on immunotherapy in cholangiocarcinoma and other biliary tract cancers are limited. Interim safety and efficacy data from the KEYNOTE-028 basket trial (NCT02054806) of the anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab have been reported for a small cohort of patients with PD-L1-positive biliary tract cancer163; 37 of 89 patients screened (41.6%) had PD-L1 expression on ≥1% of tumour cells by immunohistochemistry, 24 of whom enrolled in the study (20 with cholangiocarcinoma, four with gallbladder carcinoma)163. Of these 24 patients, four (17%, three with cholangiocarcinoma and one with gallbladder carcinoma) had a partial response, and four (17%) had stable disease163. The duration of partial response was protracted, with the median PFS not reached at the time of reporting. The rate of grade 3 toxicities was 16.7%, with no patients experiencing grade ≥4 toxicities, nor any marked hepatotoxicity163. The promising safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab in the KEYNOTE-028 biliary cancer cohort prompted a successor biliary cancer cohort of 100 patients in the ongoing KEYNOTE-158 basket trial (NCT02628067; TABLE 1).

Patients with MMR-deficient cholangiocarcinoma have also demonstrated responsiveness to treatment with immune-checkpoint inhibitors166,167,172. Among 86 patients with MMR-deficient tumours, encompassing 12 different tumour types including cholangiocarcinoma (n = 4), PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab resulted in objective radiographic responses in 53% of patients, and in 25% of patients with cholangiocarcinoma (one of the patients with cholangiocarcinoma had a complete response, and the other three had stable disease, for a disease-control rate of 100%)172; median PFS and overall survival were not reached at the time of publication172. These provocative preliminary clinical data hold promise for immunotherapy approaches in cholangiocarcinoma, while underscoring the importance of biomarker development to identify patients who are most likely to respond, and to guide the rational selection of combination therapies. A number of clinical trials evaluating novel immunotherapy approaches in patients with cholangiocarcinoma are currently ongoing (TABLE 1).

Conclusions

Cholangiocarcinomas are anatomically distinct and genetically heterogeneous tumours. Current modalities for establishing a cholangiocarcinoma diagnosis are insufficient, as detection of the disease at a sufficiently early stage to enable potentially curative surgical therapies remains an arduous task. Novel biomarkers that merit further investigation include DNA-methylation markers, non-coding RNAs, and peptide panels60,173–175. Thus, one can envision the application of advanced technologies such as proteomic analysis by mass spectrometry or 2D gel electrophoresis, and microRNA analysis for the detection of cholangiocarcinoma biomarkers in biological specimens, including bile, serum, or stool samples. In addition, FISH could potentially be used to detect novel gene fusions in patients with cholangiocarcinoma.

An enhanced understanding of the driver genetic aberrations in each disease subtype is integral to establishing a precision medicine approach to cholangiocarcinoma therapy. Moreover, recently described gene fusions and mutations in cholangiocarcinoma need further investigation in functional studies and clinical trials. Emerging therapies that hold considerable promise include FGFR inhibitors and IDH1 and/or IDH2 inhibitors, as well as immunotherapies. Identification of biomarkers for the selection of patients harbouring pertinent genetic aberrations is an essential factor in targeted therapy. In future trials, patients should be stratified according to disease subtype and genetic drivers. Such biomarker-driven trials will be imperative in the development of effective medical therapies for cholangiocarcinoma. The extensive interactions and crosstalk between the various signalling pathways involved in cholangiocarcinoma carcinogenesis highlights the importance of combination therapeutic approaches. In particular, the combination of molecularly targeted agents and immunotherapy with immune-checkpoint inhibitors merits further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Sup Table

Key points.

- Each anatomical subtype of cholangiocarcinoma, intrahepatic (iCCA), perihilar (pCCA) and distal (dCCA), has a distinct epidemiology, biology, and prognosis, thus necessitating different management approaches

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has improved the diagnostic performance of conventional cytology for the detection of pCCA and dCCA; several emerging diagnostic modalities, including liquid biopsy techniques, might further improve cholangiocarcinoma diagnosis

- Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by liver transplantation offers the best outcomes for a subset of patients with pCCA; liver transplantation might also be an option for patients with very early stage iCCA

- Emerging evidence indicates that high-dose, conformal external-beam radiation therapy is a potential treatment option for patients with localized, unresectable iCCA

- An enhanced understanding of the potential driver genetic aberrations in cholangiocarcinomas has heralded several novel drugs for advanced-stage disease, including FGFR inhibitors and IDH inhibitors; targeted therapy and immunotherapy combinations also hold promise

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Courtney Hoover for her excellent secretarial support. The work of the authors is supported by the US NIH (grants DK59427 to G.J.G., 1R03CA212877-01 to R.K.K., and DK84567 to the Mayo Center for Cell Signalling in Gastroenterology), and by the Mayo Foundation. S.I.I. has also received support from the Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation and from the Mayo Center for Cell Signalling in Gastroenterology (Pilot & Feasibility Award P30DK084567).

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to all aspects of the preparation of this manuscript.

Competing interests statement

R.K.K has received research support from Agios, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Novartis, via her institution, for conduct of clinical trials in cholangiocarcinoma. S.I.I., S.A.K., C.L.H., and G.J.G. declare no competing interests.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

See online article: S1 (table)

References

- 1.Ilyas SI, Gores GJ. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1215–1229. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saha SK, Zhu AX, Fuchs CS, Brooks GA. Forty-year trends in cholangiocarcinoma incidence in the US: intrahepatic disease on the rise. Oncologist. 2016;21:594–599. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan SA, et al. Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours. J Hepatol. 2002;37:806–813. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor-Robinson SD, et al. Increase in mortality rates from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in England and Wales 1968–1998. Gut. 2001;48:816–820. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardinale V, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: increasing burden of classifications. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2013;2:272–280. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2013.10.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarnagin WR, et al. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507–517. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barr Fritcher EG, et al. An optimized set of fluorescence in situ hybridization probes for detection of pancreatobiliary tract cancer in cytology brush samples. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1813–1824. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonda TA, et al. Mutation profile and fluorescence in situ hybridization analyses increase detection of malignancies in biliary strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:913–919. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darwish Murad S, et al. Efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoradiation, followed by liver transplantation, for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma at 12 US centers. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:88–98. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sapisochin G, et al. Liver transplantation for “very early” intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: international retrospective study supporting a prospective assessment. Hepatology. 2016;64:1178–1188. doi: 10.1002/hep.28744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valle J, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273–1281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Razumilava N, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2014;383:2168–2179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeOliveira ML, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2007;245:755–762. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251366.62632.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakeeb A, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463–473. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sripa B, Pairojkul C. Cholangiocarcinoma: lessons from Thailand. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:349–356. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282fbf9b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:115–125. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.West J, Wood H, Logan RF, Quinn M, Aithal GP. Trends in the incidence of primary liver and biliary tract cancers in England and Wales 1971–2001. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1751–1758. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel T. Worldwide trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies. BMC Cancer. 2002;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaib YH, Davila JA, McGlynn K, El-Serag HB. Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a true increase? J Hepatol. 2004;40:472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvaro D, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma in Italy. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergquist A, von Seth E. Epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;29:221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertuccio P, et al. A comparison of trends in mortality from primary liver cancer and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Europe. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1667–1674. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lepage C, et al. Trends in the incidence and management of biliary tract cancer: a French population-based study. J Hepatol. 2011;54:306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Tarone RE, Friis S, Sorensen HT. Incidence rates of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas in Denmark from 1978 through 2002. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:895–897. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altekruse SF, et al. Geographic variation of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0120574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]