Long-term Sustainability of Diabetes Prevention Approaches: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials (original) (raw)

This meta-analysis examines the use of medications and lifestyle modifications to reduce the progression to diabetes in persons with diabetes risks.

Key Points

Questions

How much do primary prevention strategies reduce the risk of conversion from prediabetes to diabetes, and are initial effects sustained over the long term?

Findings

In this meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials including 49 029 participants, lifestyle modification and medications promoting weight loss or insulin sensitization were associated with reduced diabetes risk by 36% to 39%. Effects of medications were not sustained after they were discontinued; effects of lifestyle modification, however, were sustained after intervention was stopped, although the effects waned over time.

Meaning

For individuals at risk for diabetes, healthy lifestyle changes, weight loss, or use of insulin-sensitizing medications slow the progression to diabetes similarly; lifestyle modification strategies are better in the long term, although strategies to maintain their effects are needed.

Abstract

Importance

Diabetes prevention is imperative to slow worldwide growth of diabetes-related morbidity and mortality. Yet the long-term efficacy of prevention strategies remains unknown.

Objective

To estimate aggregate long-term effects of different diabetes prevention strategies on diabetes incidence.

Data Sources

Systematic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases. The initial search was conducted on January 14, 2014, and was updated on February 20, 2015. Search terms included prediabetes, primary prevention, and risk reduction.

Study Selection

Eligible randomized clinical trials evaluated lifestyle modification (LSM) and medication interventions (>6 months) for diabetes prevention in adults (age ≥18 years) at risk for diabetes, reporting between-group differences in diabetes incidence, published between January 1, 1990, and January 1, 2015. Studies testing alternative therapies and bariatric surgery, as well as those involving participants with gestational diabetes, type 1 or 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, were excluded.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Reviewers extracted the number of diabetes cases at the end of active intervention in treatment and control groups. Random-effects meta-analyses were used to obtain pooled relative risks (RRs), and reported incidence rates were used to compute pooled risk differences (RDs).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was aggregate RRs of diabetes in treatment vs control participants. Treatment subtypes (ie, LSM components, medication classes) were stratified. To estimate sustainability, post-washout and follow-up RRs for medications and LSM interventions, respectively, were examined.

Results

Forty-three studies were included and pooled in meta-analysis (49 029 participants; mean [SD] age, 57.3 [8.7] years; 48.0% [n = 23 549] men): 19 tested medications; 19 evaluated LSM, and 5 tested combined medications and LSM. At the end of the active intervention (range, 0.5-6.3 years), LSM was associated with an RR reduction of 39% (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.54-0.68), and medications were associated with an RR reduction of 36% (RR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.54-0.76). The observed RD for LSM and medication studies was 4.0 (95% CI, 1.8-6.3) cases per 100 person-years or a number-needed-to-treat of 25. At the end of the washout or follow-up periods, LSM studies (mean follow-up, 7.2 years; range, 5.7-9.4 years) achieved an RR reduction of 28% (RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.60-0.86); medication studies (mean follow-up, 17 weeks; range, 2-52 weeks) showed no sustained RR reduction (RR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.79-1.14).

Conclusions and Relevance

In adults at risk for diabetes, LSM and medications (weight loss and insulin-sensitizing agents) successfully reduced diabetes incidence. Medication effects were short lived. The LSM interventions were sustained for several years; however, their effects declined with time, suggesting that interventions to preserve effects are needed.

Introduction

Diabetes is a burdensome, costly disease affecting 415 million adults globally, with projections of 642 million adults affected by 2040. Diabetes is the leading cause of end-stage renal failure, adult-onset blindness, and nontraumatic amputations and significantly contributes to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Treatment costs of type 2 diabetes (subsequently referred to as diabetes) remain a significant burden on individuals and health care systems, amounting to $245 billion in the United States alone in 2012. Primary prevention of diabetes has proved to be cost-effective in various populations and settings and is therefore crucial to reducing growing diabetes burdens. Yet, translating these findings into practice remains a major challenge.

Although many studies have tested different diabetes prevention interventions, data remain discordant on which modalities offer long-term efficacy. Previous reviews and meta-analyses have reported that both lifestyle modification (LSM) (ie, physical activity and dietary changes) and medications are beneficial in preventing progression to diabetes, but there are conflicting results regarding which type, frequency, and intensity of LSM or medications are most enduring that would inform clinical practice. Lack of evidence on the long-term efficacy of diabetes prevention interventions may compromise policy-making guidance. The need for such guidance is especially important as several countries embark on national diabetes prevention programs.

To deliver more granular direction in such efforts, this systematic review and meta-analysis provides an updated, rigorous evaluation of a large number of studies with comprehensive analysis of long-term efficacy of various nonsurgical diabetes prevention strategies using data from randomized clinical trials.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases for eligible articles published and indexed from January 1, 1990, to January 1, 2015. We used combinations of Medical Subject Headings and search terms, such as prediabetes, primary prevention, and risk reduction (full search strategy available in eTable 1 in the Supplement). There was no restriction on language of publication, and non-English articles were translated. We undertook the initial search on January 14, 2014, and performed an updated search on February 20, 2015. All publications were screened for eligibility independently by 2 of us (J.S.H., M.J.M.), with disagreements resolved by another one of us (M.K.A.). We adhered to PRISMA reporting guidelines for this systematic review and meta-analysis. No patients were directly involved in this meta-analysis.

Study Selection

We included published randomized clinical trials testing the efficacy of diabetes prevention interventions lasting at least 6 months in adults (age ≥18 years) with prediabetes, defined by either impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), impaired fasting glucose (IFG), or both, using diagnostic criteria according to the American Diabetes Association (1997 and 2003) or World Health Organization (1985, 1999, or 2006) and reporting between-treatment group differences in diabetes incidence rates. Diabetes was defined according to American Diabetes Association or World Health Organization criteria, which differed slightly depending on the year the study was performed, but all trials used either oral glucose tolerance tests and/or fasting plasma glucose levels to diagnose diabetes. We excluded studies involving individuals with type 1 or 2 diabetes, gestational diabetes, metabolic syndrome (where prediabetes status was not confirmed), and age younger than 18 years. We also excluded studies evaluating alternative therapies due to the large heterogeneity and lack of data on active ingredients or their potential physiologic effects. We excluded bariatric surgeries given the distinctive nature of these interventions, rigid inclusion criteria, and cost.

Data Extraction

From the identified studies, we extracted or calculated the number of persons who developed diabetes at the end of the active intervention period and, when reported, at the end of the washout or follow-up periods (ie, time when participants were observed after discontinuing interventions). Participant characteristics (eg, age, sex, and body mass index) and study characteristics (eg, sample size, treatment duration) were also extracted. Data were obtained using standardized abstraction templates. When the results of a study were reported in multiple publications, data from all publications were extracted under a single study identity and used for different subgroup analyses. In studies including mixed cohorts of people with prediabetes and diabetes or metabolic syndrome, we extracted data only for the prediabetes cohort. Thirty authors were contacted 1 to 5 times to clarify or obtain unpublished data required for our meta-analysis. Efforts were made to contact authors who had changed affiliation and contact information since publication. Of these, 6 authors provided additional data; in cases in which authors did not respond, we used data reported to calculate the needed values or did not include the study in the analyses.

Quality Assessment

To assess the quality of studies, we used a set of quality indicators adapted from those proposed by Jadad et al. The first indicator was blinding: whether the study blinded participants or health care professionals (1 point), both (2 points), or neither (0 points). The second indicator was attrition: whether an attrition rate of less than 20% (2 points), over 20% (1 point), or differential attrition between groups (0 points) was reported. The third indicator was statistical methods used to minimize the impact of attrition if intent-to-treat analysis (2 points) or per protocol (1 point) were applied, or if none were reported (0 points). Since all of our studies were randomized clinical trials, we replaced the random allocation indicator by a fourth indicator assessing whether CONSORT guidelines were used for appropriate randomized clinical trial reporting (2 points), no guidelines were used but reporting was clear (1 point), or reporting was unclear (0 points). Scores were summed to obtain composite quality scores for each study. Studies scoring 0 to 3 points were classified as low quality, 4 to 6 as medium quality, and 7 to 8 as high quality.

Statistical Analysis

We used random-effects meta-analysis models to account for heterogeneity between studies. For trials reporting zero events in 1 of the study arms, we used a continuity correction of 0.5. We estimated the aggregate relative risk (RR) for diabetes achieved at the end of active intervention in LSM and medication trials separately. We estimated aggregate RRs for different subtypes of LSM strategies (ie, diet, physical activity, or combined) and medication subclasses (eg, insulin sensitizers, insulin secretagogues). To explore intervention effects after treatment withdrawal, we estimated the aggregate RR for diabetes at the end of active intervention and at the end of the washout period for medication trials or at the end of the follow-up period for LSM trials.

We estimated heterogeneity across studies by computing _I_2, where _I_2 greater than 75% indicated significant heterogeneity. We used meta-regressions to explore the contribution of participant demographic characteristics and weight change to intervention effect heterogeneity. We assessed publication bias using the Egger test and visual exploration of funnel plots. The number of studies with null effects that were missing from the meta-analysis was estimated using the trim-and-fill method. Sensitivity analyses were conducted according to study quality category (low, medium, and high) to explore the risk of bias on the meta-analytic estimates. The metafor package in R, version 3.2.1 programming language was used to fit the models described.

Results

Study Characteristics

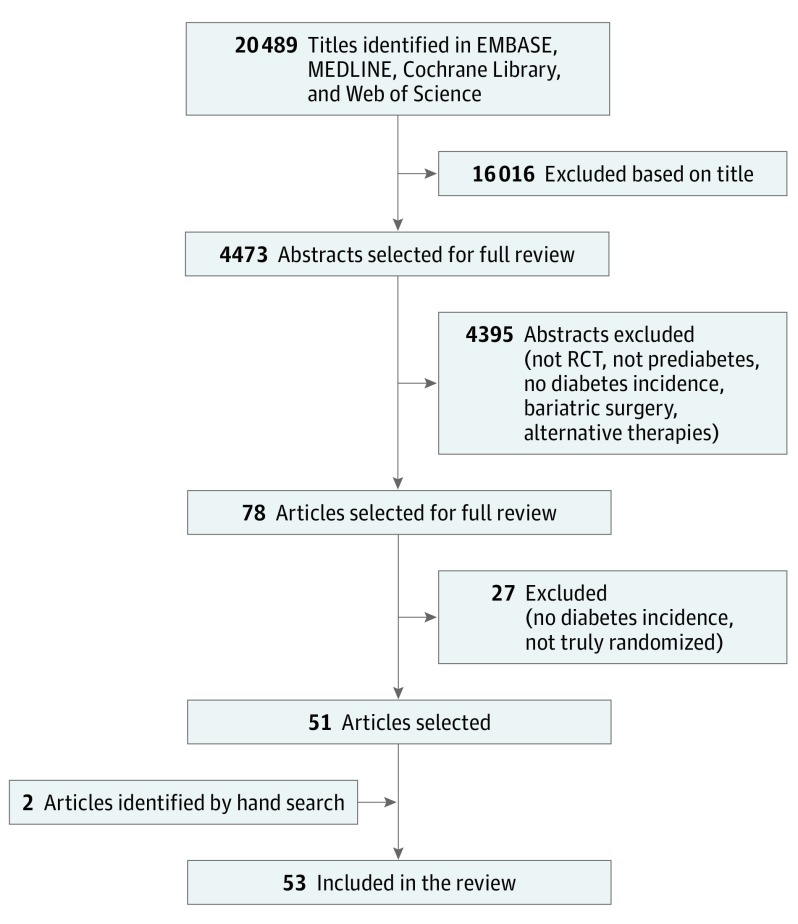

Of the 20 489 titles identified, 4473 abstracts were reviewed and 78 published articles were selected for full review. Of these, 51 articles were included, and 2 additional articles were identified manually. Overall, 53 articles were included in the systematic review (Figure 1). Of the included articles, 10 were not meta-analyzed because they either did not report the number of participants who developed diabetes at the end of the study (n = 3), did not report the number of people at risk for diabetes at baseline in each arm (n = 1), reported findings from a trial that was already included in the analyses (n = 5), or tested a drug (troglitazone) that has been discontinued (n = 1). Forty-three articles reported sufficient data for meta-analyses, and, based on quality assessment, data pooling was deemed appropriate among these studies.

Figure 1. Study Screening and Selection Flow.

Overview of study screening and selection process according to PRISMA guidelines. RCT indicates randomized clinical trial.

Of the studies analyzed, 19 evaluated single or multiple medications, 19 tested LSMs, and 5 tested both medication and LSMs. Forty studies had a total follow-up length ranging from 0.5 to 6.3 years, while the US Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS), and the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study (Da Qing) reported follow-up lengths of 10, 13, and 20 years since randomization, respectively. The total number of participants across studies was 49 029 (mean [SD] age, 57.3 [8.7] years; 23 549 [48.0%] men; baseline body mass index, 30.8 [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared]) and included Asian, North American, and European participants (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

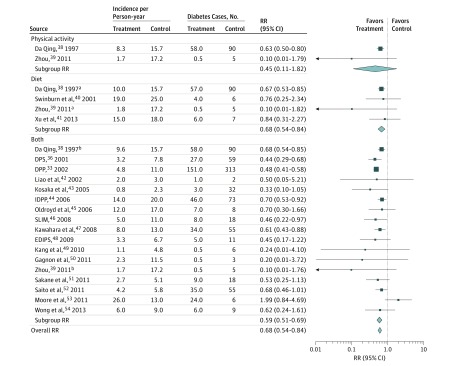

Efficacy of LSM Interventions

During the active intervention period (mean [SD], 2.6 [1.7] years; range, 0.5-6.0 years), LSM studies (n = 19) achieved an RR reduction of 39% (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.54-0.68). Diabetes incidence rates in intervention participants were 7.4 cases per 100 person-years compared with 11.4 cases per 100 person-years in control participants (risk difference [RD], 4.0; 95% CI, 1.8-6.3). Overall, 25 persons would need to be treated with LSM to prevent 1 case of diabetes. The DPP, DPS, and Da Qing studies achieved the largest RR reductions (Figure 2). Using dietary strategies alone was associated with a 32% RR reduction (RR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.54-0.84) in diabetes incidence, albeit only counseling with individualized diet plans achieved significant effects (RR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.53-0.85). Using physical activity interventions alone (n = 2) did not significantly reduce the risk for diabetes except in the Da Qing study, which implemented individualized exercise plans (RR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.50-0.80). Combined diet and physical activity strategies achieved a 41% RR reduction (RR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.51-0.69).

Figure 2. Relative Risks (RRs) and Diabetes Incidence Rates Among Lifestyle Modification Intervention Studies Stratified by Intervention Strategy at the End of the Active Intervention Period.

Nineteen studies including 24 comparisons were analyzed. Active intervention mean (SD) duration was 2.6 (1.7) years (range, 0.5-6.0 years). Overall RR is the pooled effect for all studies; subgroup RR is the pooled effect for a subgroup of studies. DPP indicates Diabetes Prevention Program; DPS, Diabetes Prevention Study; EDIPS, European Diabetes Prevention Study; IDPP, Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme; and SLIM, Study on Lifestyle-Intervention and Impaired Glucose Tolerance Maastricht.

aSecond arm of the same study.

bThird arm of the same study.

Efficacy of Medication Interventions

During the active intervention period (mean [SD], 3.1 [1.5] years; range, 1.0-6.3 years), medication trials (n = 21; 18 medication and 3 LSM plus medication trials) achieved an RR reduction of 36% (RR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.54-0.76). Diabetes incidence rates in intervention participants were 5.4 cases per 100 person-years compared with 9.4 cases per 100 person-years in control participants (RD, 4.0; 95% CI, 2.3-5.7). Overall, 25 persons would need to be treated to prevent 1 case of diabetes. Weight loss drugs (orlistat, combination phentermine-topiramate) achieved the largest RR reduction of 63% (RR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.22-0.62) (Figure 3). Insulin sensitizers (metformin, rosiglitazone, and pioglitazone) achieved an RR reduction of 53% (RR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.32-0.68). Among renin-angiotensin system blockade drugs, only valsartan achieved a significant 10% RR reduction (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.85-0.95). α-Glucosidase inhibitors (acarbose, voglibose) achieved a 38% RR reduction (RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.44-0.88), with 2 studies showing significant effects and 3 studies showing no effects. A lipid-lowering drug (bezafibrate) and insulin analogue (glargine) achieved RR reductions of 32% (RR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.48-0.95) and 21% (RR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.67-0.94), respectively. Hormone therapy (estrogen and progestin) and insulin secretagogues (glipizide, nateglinide) were not associated with significant RRs in diabetes incidence.

Figure 3. Relative Risks (RRs) and Diabetes Incidence Rates Among Medication Studies Stratified by Drug Class at the End of the Active Intervention Period.

Twenty-one studies including 24 comparisons were analyzed. Active treatment mean (SD) duration was 3.1 (1.5) years (range, 1.0-6.3 years). Overall RR is the pooled effect for all studies; subgroup RR is the pooled effect for a subgroup of studies. ACE indicates angiotensin-converting enzyme; ACT NOW, Actos Now for Prevention of Diabetes; BIP, Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention Study; CANOE, Canadian Normoglycemia Outcomes Evaluation; DAISI, Dutch Acarbose Intervention Study in Persons With Impaired Glucose Tolerance; DIANA, Diabetes and Diffuse Coronary Narrowing; DPP, Diabetes Prevention Program; DREAM, Diabetes Reduction Assessment With Ramipril and Rosiglitazone Medication; ER, extended release; HERS, Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study; IDPP, Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme; NAVIGATOR, Nateglinide and Valsartan in Impaired Glucose Tolerance Outcomes Research; ORIGIN, Outcome Reduction With Initial Glargine Intervention; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; STOP-NIDDM, Study to Prevent Non–Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus; TRANSCEND, Telmisartan Randomised Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease; and XENDOS, Xenical in the Prevention of Diabetes in Obese Subjects.

aSecond arm of the same study.

Sustainability of Diabetes Prevention

To explore whether diabetes prevention effects were sustained after treatment withdrawal, we estimated the RR for diabetes at the end of the intervention and at the end of the washout or follow-up periods among studies reporting these data (5 testing medications, 3 testing LSM, and 1 testing LSM and medication) (Table). Of medication trials, 2 tested insulin sensitizers (metformin, rosiglitazone), 1 evaluated an insulin secretagogue (glipizide), and the remaining 3 tested a renin-angiotensin system blockade, α-glucosidase inhibitor, and insulin. The mean observation periods for washouts across these studies was 17 weeks (range, 2-52 weeks). Compared with those receiving placebo, participants receiving the study drug had a 29% lower diabetes risk at the end of the active intervention (RR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55-0.92), while no significant RR reductions were observed at the end of the washout period (RR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.79-1.14). Of LSM trials, 4 (DPP, Da Qing, DPS, and Swinburn et al) provided follow-up data. Only the DPP trial implemented strategies to maintain lifestyle changes and offered the LSM intervention to control participants during the postintervention observation period. The mean follow-up duration across these studies was 7.2 years (range, 5.7-9.4 years). Compared with control participants, those receiving LSM intervention had a 45% lower diabetes risk at the end of the active intervention period (RR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.43-0.70) and a 28% lower risk at the end of the follow-up period (RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.60-0.86).

Table. Random-Effects Meta-analyses Exploring RR for Diabetes Among LSM and Medication Studies After Treatment Withdrawal.

| Source | Intervention | Active Intervention, y | End of Active Intervention, RR (95% CI) | Follow-upa | End of Follow-up, RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSM Trials | |||||

| Swinburn et al, 2001 | Reduced-fat diet | 1.0 | 0.76 (0.25-2.34) | 5.0 y | 0.70 (0.26-1.88) |

| DPP, 2002, 2009b | Diet and physical activity | 2.8 | 0.48 (0.41-0.58) | 5.7 y | 0.68 (0.63-0.73) |

| DPS, 2001, 2013 | Diet and physical activity | 4.0 | 0.44 (0.29-0.68) | 9.0 y | 0.63 (0.54-0.73) |

| Da Qing, 1997, 2008 | Diet and physical activity | 6.0 | 0.68 (0.54-0.85) | 9.4 y | 0.86 (0.81-0.92) |

| Pooled estimate | 0.55 (0.43-0.70) | 0.72 (0.60-0.86) | |||

| Medication Trials | |||||

| Eriksson et al,2006 | Glipizide | 0.5 | 0.41 (0.01-11.3) | 52 wk | 0.20 (0.03-1.53) |

| DREAM, 2006, 2011 | Rosiglitazone | 3.0 | 0.43 (0.37-0.48) | 10 wk | 1.07 (0.88-1.32) |

| DREAM, 2006, 2011b | Ramipril | 3.0 | 0.93 (0.82-1.04) | 10 wk | 1.08 (0.89-1.33) |

| DPP, 2002, 2003 | Metformin | 2.8 | 0.76 (0.66-0.88) | 2 wk | 0.76 (0.68-0.85) |

| STOP-NIDDM, 2002 | Acarbose | 3.0 | 0.78 (0.68-0.90) | 12 wk | 1.46 (0.90-2.36) |

| ORIGIN, 2012 | Insulin glargine | 6.2 | 0.79 (0.67-0.94) | 14 wk | 0.86 (0.74-0.99) |

| Pooled estimate | 0.71 (0.55-0.92) | 0.95 (0.79-1.14) |

Heterogeneity and Study Quality

Studies were heterogeneous, leading to a high proportion of variability between study effects. Heterogeneity was larger for medication (I2 range, 0%-89%) than LSM (I2 range, 0%-36%) studies. In a multivariate meta-regression, amount of weight lost, participant mean age, and proportion of male participants accounted for 59% of the heterogeneity (P < .01). In this model, only weight lost was significantly associated with diabetes risk, in which every kilogram lost explained an additional 7% decrease in diabetes relative risk (β = −0.07; P < .01) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Of the 43 pooled studies, 38 were unique trials and 5 were reports of different follow-up periods of studies already included. Of the 38 unique studies, 11 were classified as high-quality, 22 as medium-quality, and 5 as low-quality. In sensitivity analyses, high-, medium-, and low-quality studies showed similar RR reductions ranging from 35% in high-quality (RR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.50-0.84), 37% in medium-quality (RR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.54-0.73), and 42% in low-quality (RR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.41-0.81) studies.

We found evidence of publication bias (t = −4.139; P < .001), and visual examination of the funnel plot showed that studies with small or null effects were less likely to be published (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). The trim-and-fill test demonstrated that approximately 9 studies with null effects were missing, and sensitivity analysis showed that, if included, diabetes RR reduction would be smaller (33% vs 36%), albeit still significant (P < .001). When examined individually, no study was found to significantly influence aggregate estimates.

Discussion

This meta-analysis shows that LSM and certain medications are effective in preventing diabetes in persons at risk, although only LSM strategies seem to have a sustainable effect. Diet with physical activity or weight loss and insulin-sensitizing medications prevent progression to diabetes in individuals at risk, with 25 persons needing to be treated to prevent a single diabetes case. Across all interventions, weight loss appears to be the key factor associated with reduced diabetes progression.

Our findings show that LSM interventions are efficacious for preventing diabetes. The RR reduction that we observed in LSM interventions is similar to estimates from other meta-analyses. Combined diet alterations and physical activity proved to be more effective in reducing progression to diabetes than either strategy alone. Since caloric intake and physical activity are independently associated with reduced diabetes risk, combining these may exert an additive effect.

Medications are efficacious in preventing diabetes in those at risk in the short term, although they present with wide variations depending on the class of medication; these results are similar to those from previous meta-analyses. Our study expands this evidence by including combined phentermine-topiramate, a newer antiobesity drug. We showed that weight-loss medications, followed by insulin sensitizers, achieved the greatest diabetes risk reductions. Newer US Food and Drug Administration–approved weight loss medications (eg, liraglutide, combined naltrexone-bupropion) may also slow progression to diabetes, although studies testing these drugs were pending at the time of our literature search. Insulin sensitizers, such as the glitazones and metformin, have shown efficacy for diabetes prevention in other meta-analyses. We found mixed or small effects of α-glucosidase inhibitors and renin-angiotensin system blockers, indicating insufficient evidence to make firm conclusions.

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to explore the long-term effects of diabetes prevention interventions after treatment withdrawal. We found that participants receiving LSM interventions had lower risk for diabetes than control participants 5 to 9 years after completing the intervention, although the effects decreased over time. However, our aggregate findings regarding the durability of LSM may also be considered conservative since the control arm of DPP received the intervention when the trial was prematurely stopped; therefore, all long-term, between-group differences are smaller than if the control participants had not received any intervention. The 15-year follow-up results of the DPP found a similar waning of effects after the initial 2.8 years of active intervention, suggesting plateauing of effects or saturation among at-risk individuals as most have already progressed to diabetes. This diminished effect also suggests that maintenance strategies, such as those tested in the DPP, may be needed to sustain intervention effects. Regarding the sustainability of medication effects, our analysis using washout data showed that the initial effects of medications dissipated after the washout period. This finding suggests that medications do not permanently alter fundamental pathophysiology of insulin resistance or β-cell dysfunction and likely only suppress hyperglycemia for the time that they are administered. No weight loss medications were included in this subgroup analysis, indicating a need for further studies on the long-term effects of weight loss medications on both weight lost and regained and their effects on future diabetes incidence. Overall, our findings suggest that LSM interventions are promising long-term diabetes prevention strategies; however, maintenance interventions, even if intermittent, may be needed for prolonged intervention effects.

We found that every kilogram of weight lost was associated with an additional 7% decrease in risk of progression to diabetes. Other systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown variable effects of weight loss on the incidence of diabetes, reporting positive and null effects. Physiologically, it has been shown that losing weight depletes free fatty acids from both muscle and liver, resulting in improved insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis. Additional research has demonstrated that obesity-induced β-cell dysfunction can be restored with caloric restriction and reversion to normal weight in overweight and obese individuals. The long-term effect in insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction associated with weight lost due to lifestyle changes vs medications vs bariatric surgery requires further investigation.

Overall, the evidence that this meta-analysis provides is strong given that all of the studies used randomized clinical trial study designs and 79% of the included studies were deemed as having low risk of bias (ie, they were medium to high quality). However, we found evidence of publication bias, which means that smaller studies with null effects were less likely to be published. Countries that plan to launch national diabetes prevention programs should consider modeling their strategies after LSM interventions proven to prevent diabetes, such as the DPP, DPS, and Da Qing, and to implement strategies to sustain long-term effects. Gaps that remain include exploring intervention effects according to glucose intolerance type (ie, IFG vs IGT), publishing studies with null effects, and economic evaluations of long-term maintenance strategies. Future studies and meta-analyses should consider addressing these gaps.

Limitations

Although we provide a comprehensive, rigorous meta-analysis on the efficacy of diabetes prevention treatments, this study has some limitations. We found a high level of heterogeneity in treatment effects, which was only partially explained in meta-regressions and subgroup analyses. This heterogeneity suggests that there are other factors affecting treatment efficacy that were not accounted for, which may involve the pooling of both IFG and IGT definitions of prediabetes. Comparisons among studies require caution given that various definitions of diabetes were used in the trials (eg, World Health Organization 1985, 1999, and 2006; American Diabetes Association 1997, 2003), although they were used consistently within each trial. Another limitation is that we did not directly compare the efficacy of LSM against that of medications; a network meta-analysis is required for such comparison. Finally, we used English search terms, which may have prevented us from finding studies published in other languages.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that diabetes can be prevented in those at risk through multiple LSM strategies and certain medication classes, allowing health care professionals to individualize preventive care appropriate to community resources, individual motivations, and coverage for various interventions. Combined diet and physical activity programs and use of insulin-sensitizing and weight-loss medications achieve the largest diabetes risk reductions. Overall, LSM strategies provide better long-term effects than medications, although strategies to sustain intervention effects are needed. As intervention effects decrease over time, future research should identify cost-effective, successful maintenance strategies to prevent or delay progression to diabetes. Additionally, more studies identifying the differences in intervention effects for those with isolated IGT, isolated IFG, or both are needed to develop better individualized prevention approaches. Dissemination and real-world implementation of LSM with strategies for long-term sustainability on a large-scale is critical in addressing the global diabetes burden.

Supplement.

eTable 1. Search Terms and Combination MeSH Terms Used

eTable 2. Characteristics of Included and Analyzed Studies

eFigure 1. Meta-Regression Examining the Influence of Weight Lost on Diabetes Risk Among Studies Reporting This Outcome

eFigure 2. Funnel Plot Exploring Publication Bias

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas—7th Edition www.diabetesatlas.org. Accessed December 15, 2015.

- 2.World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010 Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li R, Qu S, Zhang P, et al. Economic evaluation of combined diet and physical activity promotion programs to prevent type 2 diabetes among persons at increased risk: a systematic review for the Community Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):452-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillies CL, Abrams KR, Lambert PC, et al. Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;334(7588):299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens JW, Khunti K, Harvey R, et al. Preventing the progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults at high risk: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of lifestyle, pharmacological and surgical interventions. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;107(3):320-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuen A, Sugeng Y, Weiland TJ, Jelinek GA. Lifestyle and medication interventions for the prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus in prediabetes: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34(2):172-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balk EM, Earley A, Raman G, Avendano EA, Pittas AG, Remington PL. Combined diet and physical activity promotion programs to prevent type 2 diabetes among persons at increased risk: a systematic review for the Community Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):437-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merlotti C, Morabito A, Pontiroli AE. Prevention of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of different intervention strategies. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(8):719-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torjesen I. NHS England rolls out world’s first national diabetes prevention programme. BMJ. 2016;352:i1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albright AL, Gregg EW. Preventing type 2 diabetes in communities across the US: the National Diabetes Prevention Program. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4)(suppl 4):S346-S351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(7):1183-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(suppl 1):S33-S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications; part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15(7):539-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization Definition and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intermediate Hyperglycemia: Report of a WHO/IDF Consultation Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(8):834-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F. Methods for Meta-analysis in Medical Research. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(3):1-48. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Effects of withdrawal from metformin on the development of diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(4):977-980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DREAM Trial Investigators Incidence of diabetes following ramipril or rosiglitazone withdrawal. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(6):1265-1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebbesson SO, Ebbesson LO, Swenson M, Kennish JM, Robbins DC. A successful diabetes prevention study in Eskimos: the Alaska Siberia project. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2005;64(4):409-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason C, Foster-Schubert KE, Imayama I, et al. Dietary weight loss and exercise effects on insulin resistance in postmenopausal women. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4):366-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oldroyd JC, Unwin NC, White M, Imrie K, Mathers JC, Alberti KG. Randomised controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of behavioural interventions to modify cardiovascular risk factors in men and women with impaired glucose tolerance: outcomes at 6 months. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2001;52(1):29-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenstock J, Klaff LJ, Schwartz S, et al. Effects of exenatide and lifestyle modification on body weight and glucose tolerance in obese subjects with and without pre-diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(6):1173-1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perreault L, Pan Q, Mather KJ, Watson KE, Hamman RF, Kahn SE; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group . Effect of regression from prediabetes to normal glucose regulation on long-term reduction in diabetes risk: results from the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2012;379(9833):2243-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li G, Hu Y, Yang W, et al. ; DA Qing IGT and Diabetes Study . Effects of insulin resistance and insulin secretion on the efficacy of interventions to retard development of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the DA Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2002;58(3):193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindström J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, et al. Prevention of diabetes mellitus in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(7)(suppl 2):S108-S113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindström J, Louheranta A, Mannelin M, et al. ; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group . The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS): lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(12):3230-3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindström J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, et al. ; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group . Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet. 2006;368(9548):1673-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knowler WC, Hamman RF, Edelstein SL, et al. ; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group . Prevention of type 2 diabetes with troglitazone in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes. 2005;54(4):1150-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. ; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group . Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. ; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group . 10-Year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1677-1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindström J, Peltonen M, Eriksson JG, et al. ; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS) . Improved lifestyle and decreased diabetes risk over 13 years: long-term follow-up of the randomised Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS). Diabetologia. 2013;56(2):284-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, et al. ; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group . Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1343-1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371(9626):1783-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance; the Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(4):537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou J. [Life style interventions study on the effects of impaired glucose regulations in Shanghai urban communities]. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2011;40(3):331-333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swinburn BA, Metcalf PA, Ley SJ. Long-term (5-year) effects of a reduced-fat diet intervention in individuals with glucose intolerance. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(4):619-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu DF, Sun JQ, Chen M, et al. Effects of lifestyle intervention and meal replacement on glycaemic and body-weight control in Chinese subjects with impaired glucose regulation: a 1-year randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr. 2013;109(3):487-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liao D, Asberry PJ, Shofer JB, et al. Improvement of BMI, body composition, and body fat distribution with lifestyle modification in Japanese Americans with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(9):1504-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kosaka K, Noda M, Kuzuya T. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: a Japanese trial in IGT males. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;67(2):152-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S, Mukesh B, Bhaskar AD, Vijay V; Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme (IDPP) . The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme shows that lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1). Diabetologia. 2006;49(2):289-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oldroyd JC, Unwin NC, White M, Mathers JC, Alberti KG. Randomised controlled trial evaluating lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;72(2):117-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roumen C, Corpeleijn E, Feskens EJ, Mensink M, Saris WH, Blaak EE. Impact of 3-year lifestyle intervention on postprandial glucose metabolism: the SLIM study. Diabet Med. 2008;25(5):597-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawahara T, Takahashi K, Inazu T, et al. Reduced progression to type 2 diabetes from impaired glucose tolerance after a 2-day in-hospital diabetes educational program: the Joetsu Diabetes Prevention Trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(10):1949-1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Penn L, White M, Oldroyd J, Walker M, Alberti KG, Mathers JC. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in adults with impaired glucose tolerance: the European Diabetes Prevention RCT in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kang JY, Cho SW, Sung SH, Park YK, Paek YM, Choi TI. Effect of a continuous diabetes lifestyle intervention program on male workers in Korea. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;90(1):26-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gagnon C, Brown C, Couture C, et al. A cost-effective moderate-intensity interdisciplinary weight-management programme for individuals with prediabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37(5):410-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sakane N, Sato J, Tsushita K, et al. ; Japan Diabetes Prevention Program (JDPP) Research Group . Prevention of type 2 diabetes in a primary healthcare setting: three-year results of lifestyle intervention in Japanese subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saito T, Watanabe M, Nishida J, et al. ; Zensharen Study for Prevention of Lifestyle Diseases Group . Lifestyle modification and prevention of type 2 diabetes in overweight Japanese with impaired fasting glucose levels: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1352-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moore SM, Hardie EA, Hackworth NJ, et al. Can the onset of type 2 diabetes be delayed by a group-based lifestyle intervention? a randomised control trial. Psychol Health. 2011;26(4):485-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wong CKH, Fung CSC, Siu SC, et al. A short message service (SMS) intervention to prevent diabetes in Chinese professional drivers with pre-diabetes: a pilot single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;102(3):158-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, Sjöström L. XENical in the Prevention of Diabetes in Obese Subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):155-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Henry R, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in subjects with prediabetes and metabolic syndrome treated with phentermine and topiramate extended release. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(4):912-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bosch J, Yusuf S, Gerstein HC, et al. ; DREAM Trial Investigators . Effect of ramipril on the incidence of diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1551-1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McMurray JJ, Holman RR, Haffner SM, et al. ; NAVIGATOR Study Group . Effect of valsartan on the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(16):1477-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barzilay JI, Gao P, Rydén L, et al. ; TRANSCEND Investigators . Effects of telmisartan on glucose levels in people at high risk for cardiovascular disease but free from diabetes: the TRANSCEND study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):1902-1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tenenbaum A, Motro M, Fisman EZ, et al. Effect of bezafibrate on incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in obese patients. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(19):2032-2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li CL, Pan CY, Lu JM, et al. Effect of metformin on patients with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabet Med. 1999;16(6):477-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zinman B, Harris SB, Neuman J, et al. Low-dose combination therapy with rosiglitazone and metformin to prevent type 2 diabetes mellitus (CANOE trial): a double-blind randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2010;376(9735):103-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu YH, Lu JM, Wang SY, et al. Outcome of intensive integrated intervention in participants with impaired glucose regulation in China. Adv Ther. 2011;28(6):511-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D, Schwenke DC, et al. ; ACT NOW Study . Pioglitazone for diabetes prevention in impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(12):1104-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eriksson JG, Lehtovirta M, Ehrnström B, Salmela S, Groop L. Long-term beneficial effects of glipizide treatment on glucose tolerance in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. J Intern Med. 2006;259(6):553-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kataoka Y, Yasuda S, Miyamoto Y, et al. ; DIANA Study Investigators . Effects of voglibose and nateglinide on glycemic status and coronary atherosclerosis in early-stage diabetic patients. Circ J. 2012;76(3):712-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gerstein HC, Bosch J, Dagenais GR, et al. ; ORIGIN Trial Investigators . Basal insulin and cardiovascular and other outcomes in dysglycemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(4):319-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kanaya AM, Herrington D, Vittinghoff E, et al. ; Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study . Glycemic effects of postmenopausal hormone therapy: the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(1):1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Karasik A, Laakso M; STOP-NIDDM Trial Research Group . Acarbose for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the STOP-NIDDM randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9323):2072-2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nijpels G, Boorsma W, Dekker JM, Kostense PJ, Bouter LM, Heine RJ. A study of the effects of acarbose on glucose metabolism in patients predisposed to developing diabetes: the Dutch Acarbose Intervention Study in Persons With Impaired Glucose Tolerance (DAISI). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(8):611-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kawamori R, Tajima N, Iwamoto Y, Kashiwagi A, Shimamoto K, Kaku K; Voglibose Ph-3 Study Group . Voglibose for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomised, double-blind trial in Japanese individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. Lancet. 2009;373(9675):1607-1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gerstein HC, Yusuf S, Bosch J, et al. ; DREAM (Diabetes REduction Assessment with ramipril and rosiglitazone Medication) Trial Investigators . Effect of rosiglitazone on the frequency of diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9541):1096-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.NAVIGATOR Study Group Effect of nateglinide on the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(16):1463-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(11):866-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DeFronzo RA, Eldor R, Abdul-Ghani M. Pathophysiologic approach to therapy in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(suppl 2):S127-S138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Malandrucco I, Pasqualetti P, Giordani I, et al. Very-low-calorie diet: a quick therapeutic tool to improve β cell function in morbidly obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(3):609-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement.

eTable 1. Search Terms and Combination MeSH Terms Used

eTable 2. Characteristics of Included and Analyzed Studies

eFigure 1. Meta-Regression Examining the Influence of Weight Lost on Diabetes Risk Among Studies Reporting This Outcome

eFigure 2. Funnel Plot Exploring Publication Bias