Peripheral Arterial Disease in Women: an Overview of Risk Factor Profile, Clinical Features, and Outcomes (original) (raw)

Abstract

Purpose of Review

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is the third most common manifestation of cardiovascular disease (CVD), following coronary artery disease (CAD) and stroke. PAD remains underdiagnosed and under-treated in women.

Recent Findings

Women with PAD experience more atypical symptoms and poorer overall health status. The prevalence of PAD in women increases with age, such that more women than men have PAD after the age of 40 years. There is under-representation of PAD patients in clinical trials in general and women in particular. In this article, we address the lack of women participants in PAD trials. We then present a comprehensive overview of the epidemiology/risk factor profile, clinical features, treatment, and outcomes.

Summary

PAD is prevalent in women and its global burden is on the rise despite a decline in global age-standardized death rate from CVD. The importance of this issue has been underlined by the American Heart Association’s (AHA) “Call to Action” scientific statement on PAD in women. Large-scale campaigns are needed to increase awareness among physicians and the general public. Furthermore, effective treatment strategies must be implemented.

Keywords: Peripheral arterial disease, Women, Sex differences

Background

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) remains a significant health concern across the globe. As of 2010, more than 200 million people worldwide are living with PAD, representing a 29% increased prevalence in low-middle income countries and 13% increase in high income countries [1, 2]. In the USA alone, PAD affects 8 million Americans aged > 40 years [3]. In the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry, the cumulative end point of major cardiovascular events, vascular interventions, and hospitalization was significantly higher in patients with PAD than patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) [4]. PAD is associated with equal morbidity and mortality and economic costs as CAD and ischemic stroke [5, 6]. In a scientific statement on Women and PAD from the AHA in 2012 [7], Hirsch et al. noted the increased prevalence of PAD in adults ≥ 40 years of age, and highlighted the need for raising clinical awareness, focused treatment plans, and expanding research on PAD in women. Women have higher rates of asymptomatic/subclinical disease and the majority have atypical symptoms. They also have a poorer overall health status. Women with PAD suffer more from depression compared to women without PAD [8–15, 16•].

Overall, there is limited recruitment of patients with PAD in cardiovascular trials, especially women, minorities, and the elderly [17•]. For the purpose of this review, we will focus on the different aspects of PAD in women including data on representation in research studies, epidemiology, clinical features, and outcomes.

Representation of Women in PAD Studies

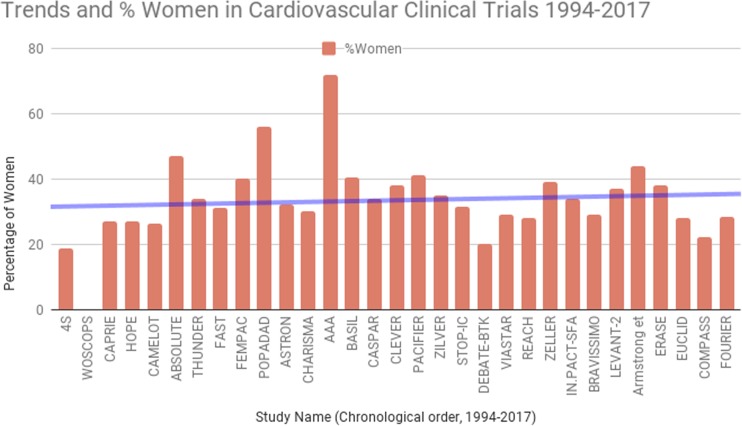

Sex differences in PAD have been reported not only in prevalence, diagnosis, and clinical presentation but also in outcomes. Women continue to have variable enrollment in studies on PAD (Table 1 and Fig. 1). In more than half of these studies, women comprise < 35% of the whole study population. In the Nation Wide inpatient sample of patients with PAD, women comprised 41% of the study population. However, in randomized control trials (RCT) of vascular surgery, women represented only 22% [18]. In a systematic review of cardiovascular trials, which collectively enrolled 412,048 patients, only 27% of the total population were women [17•]. While enrollment of women has increased overall in clinical trials, it continues to lag behind their overall representation in this disease [19•].

Table 1.

Brief overview of PAD trials and percentage of women enrolled

| Study design | Follow-up | Salient features | No. of patients | Men (%) | Women (%) | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacotherapy | |||||||

| CASPAR | RCT placebo | 2 years | Patients undergoing vascular grafting as a treatment for PAD and 2 to 4 days after bypass surgery | 851 | 66 | 34 | Combination of clopidogrel plus ASA did not improve limb or systemic outcomes in the overall population of PAD patients requiring below-knee bypass grafting. Subgroup analysis: clopidogrel plus ASA conferred benefit in patients receiving prosthetic grafts |

| AAA | Intention-to-treat double-blind RCT | 8.2 years | Patients free of clinical cardiovascular disease, recruited from a community health registry, with a positive ABI screening test | 3350 | 28 | 72 | Aspirin did not result in a significant reduction of vascular events among patients without clinical cardiovascular disease and a low ABI |

| POPADAD | RCT, double-blind, 2 × 2 factorial, placebo-controlled | 6.7 years | Adults aged > 40 with type 1 or type 2 diabetes and an ABI of 0.99 or less but no symptomatic cardiovascular disease | 1276 | 44 | 56 | No benefit from either aspirin or antioxidant treatment on the composite hierarchical primary end points of cardiovascular events and cardiovascular mortality |

| CAPRIE | Double-blind RCT | 1.91 years | Patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease | 6452 | 73 | 27 | Long-term administration of clopidogrel to patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease is more effective than aspirin in reducing the combined risk of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or vascular death |

| CHARISMA (PAD subgroup) | RCT, double-blind, 2 × 2 factorial, placebo-controlled, multicenter | 28 months | Patients with PAD identified in CHARISMA study. Current intermittent claudication + an ABI ≤ 0.85, or a history of intermittent claudication + previous related intervention (amputation, surgical or catheter-based peripheral revascularization) | 3096 | 70 | 30 | Among patients with PAD, the primary end point occurred in 7.6% in the clopidogrel plus aspirin group and 8.9% in the placebo plus aspirin group (p = 0.18). The rate of MI and hospitalization for ischemic events were lower in the DAPT arm than aspirin alone |

| EUCLID | Double-blind, event-driven RCT | 30 months | 50 years of age with symptomatic peripheral artery disease. One of two inclusion criteria: previous revascularization of the lower limbs for symptomatic disease more than 30 days before randomization or hemodynamic evidence of peripheral artery disease | 13,885 | 72 | 28 | The primary efficacy end point occurred in 10.8% receiving ticagrelor and in 10.6% receiving clopidogrel failing to show ticagrelor to be superior to clopidogrel for the reduction of cardiovascular events (p = 0.65) |

| COMPASS | Double-blind double-dummy RCT using a 3-by-2 partial factorial design | 23 months | Adults who meet criteria for CAD, PAD or both | 27,395 | 78 | 22 | Combination therapy with rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) plus aspiring among patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease had statistically significant better cardiovascular outcomes and more major bleeding events than those assigned to aspirin alone |

| 4S | Double-blind RCT | 5.4 years | Adults 35–70 years with history of angina pectoris or MI | 4444 | 81.3 | 18.7 | Simvastatin produced significant reduction of cardiovascular mortality in patients with CAD. Probability of a woman > 60 years escaping a major coronary event was 77.7% in placebo and 85.1% in simvastatin arm (p = 0.01). RR of death or coronary event in women < 60 were 0.63 and 0.61, respectively |

| WOSCOPS | Double-blind RCT | 4.9 years | Fasting LDL > 155; no history of MI, arrhythmia or other serious illness, men with stable angina who had not been hospitalized within the previous 12 months | 6595 | 100 | 0 | Pravastatin lowered plasma cholesterol levels by 20% and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels by 26%. A 22% reduction in the risk of death from any cause in the pravastatin group was observed |

| HOPE | Double-blind, 2 × 2 factorial, RCT | 3.5 years | Adults > 55 years old with history of CAD, PAD, CVA, or DM + another CV risk factor | 9297 | 73 | 27 | Treatment with ramipril-reduced rates of death from cardiovascular causes, MI, stroke, death from any cause, revascularization procedures, heart failure and complications related to DM |

| CAMELOT | Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT | 24 months | Adults 30–79 years old requiring coronary angiography for evaluation for chest pain or percutaneous coronary intervention + DBP < 100 with or without treatment | 1991 | 73.7 | 26.3 | Administration of amlodipine to patients with CAD and normal blood pressure resulted in reduced adverse cardiovascular events particularly in women (RRR 42.8%) + IVUS showed evidence of slowing of atherosclerosis progression |

| FOURIER (PAD subgroup) | Double-blind RCT | 2.2 years | Clinically evident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease including prior MI, prior ischemic stroke, or symptomatic PAD (intermittent lower extremity claudication and an ankle-brachial index < 0.85, a history of a peripheral artery revascularization procedure, or a history of amputation attributable to atherosclerotic disease) | 3642 | 71.8 | 28.2 | ARR for CV death, MI, or stroke 3.5% in patients with PAD, and 1.4% in patients without PAD |

| STOP-IC | Prospective RCT, open-label, multicenter | 12 months | Patients with symptomatic PAD attributable to de novo femoropopliteal lesions | 191 | 68.5 | 31.5 | The angiographic restenosis rate at 12 months was 20% in the cilostazol group in comparison with 49% in the noncilostazol group (p = 0.001; odds ratio, 0.26; 95% confidence interval, 0.13–0.53) |

| Exercise therapy | |||||||

| CLEVER | Multicenter RCT across 29 centers in US and Canada | 18 months | Adults > 40 years of age with moderate to severe claudication due to aortoiliac PAD. Moderate to severe claudication was defined as the ability to walk at least 2 min on a treadmill at 2 miles per hour at no grade, but <11 min on a graded treadmill test using the Gardner-Skinner protocol | 111 | 62 | 38 | Supervised exercise provides a superior improvement in treadmill walking performance compared to both primary aortoiliac revascularization and optimal medical care (home walking and cilostazol) over 6 months (p < 0.001 for the comparison of SE versus OMC, p = 0.02 for ST versus OMC, and p = 0.04 for SE versus ST). This benefit was also associated with an improvement in self-reported walking distance, an increase in high-density lipoprotein, and a decrease of fibrinogen. Secondary measures of treatment efficacy favored primary stenting, with greater improvements in self-reported physical function |

| ERASE | Parallel-design RCT conducted in the Netherlands at 10 sites | 12 months | PAD and stable claudication (≥ 3 months) with a resting ABI of < 0.90 or if their ABI decreased by more than 0.15 after treadmill testing regardless of their ABI at rest. All participants also had 1 or more vascular stenoses at the aortoiliac level, the femoropopliteal level, or both. Maximum walking distance had to be between 100 m and 500 m | 666 | 62 | 38 | Combination therapy of endovascular revascularization followed by supervised exercise resulted in significantly greater improvement in walking distances and health-related quality of life scores compared with supervised exercise only |

| Interventional | |||||||

| IN.PACT SFA | prospective, multicenter, single-blinded, RCT | 12 months | Patients with intermittent claudication or ischemic rest pain due to superficial femoral and/or popliteal PAD | 331 | 66 | 34 | Drug-coated balloon was superior to PTA and had a favorable safety profile for the treatment of patients with symptomatic femoropopliteal peripheral artery disease |

| LEVANT-2 | Single-blind, RCT | 12 months | Rutherford stage 2–4 with ≥ 70% angiographically significant atherosclerotic lesion in the superficial femoral or popliteal artery, or both. The total treated lesion length had to be 15 cm or less, and the reference diameter of the target vessel had to be 4–6 mm | 476 | 63 | 37 | PTA with a paclitaxel-coated balloon resulted in a rate of primary patency at 12 months that was higher than the rate with angioplasty with a standard balloon |

| THUNDER | RCT, multicenter | 5 years | Symptomatic peripheral artery disease with one or more obstructive lesions, either new lesions or restenoses, at least 70% of vessel diameter and at least 2 cm in length, in the superficial femoral artery, the popliteal artery, or both | 154 | 65.5 | 34.5 | Use of paclitaxel-coated angioplasty balloons (PCB) during percutaneous treatment of femoropopliteal disease is associated with significant reductions in late lumen loss and target lesion revascularization. Reduced rate of revascularization following PCB treatment was maintained over a 5 year period, although noted to be higher in women |

| ABSOLUTE | Single-institution RCT | 12 months | Symptomatic PAD with Rutherford stage 3–5; > 50% or occlusion of the ipsilateral superficial femoral artery, a target lesion length of more than 30 mm, and at least one patent (< 50% stenosis) tibioperoneal runoff vessel | 104 | 53 | 47 | At 6–12 months, treatment of superficial femoral artery disease by primary implantation of a self-expanding nitinol stent yielded results that were superior to those with the currently recommended approach of balloon angioplasty with optional secondary stenting |

| ASTRON | Multicenter RCT | 12 months | Symptomatic PAD Rutherford class 3–5; > 50% stenosis or occlusion of the SFA with a target lesion length between 30 mm and 200 mm, and at least one patent (< 50% stenosis) tibioperoneal runoff vessel | 73 | 68 | 32 | Primary stenting with a self-expanding nitinol stent for treatment of intermediate length SFA disease resulted morphologically and clinically superior midterm results compared with balloon angioplasty with optional secondary stenting |

| FAST | Multicenter RCT in 11 European centers | 12 months | De novo SFA lesion located at least 1 cm from the SFA origin with a length between 1 and 10 cm. Target lesion diameter stenosis had to be at least 70% by visual estimate. The popliteal artery as well as 1 of the infrapopliteal (below-the-knee) vessels had to be continuously patent for sustained distal runoff. Clinically, patients to have at least Rutherford category 2 | 244 | 69 | 31 | No statistically significant difference between treatment groups was observed at 12 months in the improvement by at least 1 Rutherford category of peripheral arterial disease |

| PACIFIER | Investigator-initiated multicenter RCT conducted in three German institutions | 12 months | Claudication or critical limb ischemia (Rutherford 2–5); disease of SFA or popliteal artery; lesion length 3–30 cm; an occlusion or a grade of stenosis ≥ 70%, and absence of contraindications to dual antiplatelet therapy | 85 | 59 | 41 | DEB was associated with significant reductions in late lumen loss and restenosis at 6 months, and re-interventions after femoropopliteal percutaneous transluminal angioplasty up to 1 year of follow-up |

| VIASTAR | Prospective, single-blind, multicenter, RCT | 24 months | Symptomatic PAD in the Rutherford stage 2–5, de novo arteriosclerotic stenosis or occlusion of the SFA and proximal popliteal artery 10–35 cm in length (TASC II classes B-D), patent or successfully treated iliac artery inflow, and outflow of at least 1 tibial artery | 141 | 71 | 29 | In lesions ≥ 20 cm, (TASC class D), the 12-month patency rate was significantly longer in VIA patients. Freedom from target lesion revascularization was 84.6% for Viabahn versus 77.0% for BMS. The ankle-brachial index in the Viabahn group significantly increased compared with the BMS at 12 months |

| DEBATE-BTK | Single-center, parallel-group, open blinded end point RCT | 12 months | presence of diabetes mellitus, CLI (Rutherford class 4 or greater), stenosis or occlusion ≥ 40 mm of at least 1 tibial vessel with distal runoff to the foot, and agreement to 12-month angiographic evaluation | 132 | 80 | 20 | Drug-eluting balloons compared with PTA strikingly reduce 1-year restenosis, target lesion revascularization, and target vessel occlusion in the treatment of below-the-knee lesions in diabetic patients with critical limb ischemia |

| ZILVER | Prospective, multinational RCT with a complementary single-arm study | 24 months | Rutherford category ≥ 2, ≥ 50% diameter stenosis, reference vessel diameter 4–9 mm, lesion length up to 14 cm, and at least 1 patent runoff vessel with < 50% stenosis throughout its course | 474 | 65 | 35 | Primary DES group demonstrated significantly superior 2-year event-free survival and primary patency |

| FEMPAC | Multicenter RCT | 6 months | Occlusion/stenosis ≥ 70% diameter of the SFA and/or popliteal artery with clinical Rutherford stages 1–5; successful guidewire passage of the lesion during angiography | 87 | 60 | 40 | The number of target lesion revascularizations was lower in the paclitaxel-coated balloon group than in control subjects (p = 0.002). Improvement in Rutherford class was greater in the coated balloon group (p = 0.045), whereas the improvement in ankle-brachial index did not achieve statistical significance |

| BASIL | Multicenter RCT, prospective, across 27 UK hospitals | 5.5 years | Severe limb ischemia, for > 2 weeks, and who on diagnostic imaging had a pattern of disease which, in joint investigator opinions, could equally well be treated by either infra-inguinal bypass surgery or balloon angioplasty | 452 | 59.5 | 40.5 | In patients presenting with severe limb ischemia due to infra-inguinal disease and who are suitable for surgery and angioplasty, a bypass surgery-first and a balloon angioplasty-first strategy are associated with broadly similar outcomes in terms of amputation-free survival, and in the short-term, surgery is more expensive than angioplasty |

| ACHILLES | Prospective multicenter RCT in nine European countries | 1 year | Adults with infrapopliteal PAD. Reasons for exclusion were significant stenoses (> 50%) distal to the target lesion that might require revascularization or impede runoff; angiographically evident thrombus or history of thrombolysis within 72 h; untreated lesions (> 75% stenosis), Cr > 2.5 mg/dl | 200 | 71.5 | 28.5 | lower angiographic restenosis rates (22.4 vs 41.9%, p = 0.019), greater vessel patency (75.0% vs 57.1%, p = 0.025), and similar death, repeat revascularization, index-limb amputation rates, and proportions of patients with improved Rutherford class for sirolimus-eluting stents vs PTA |

| DESTINY | RCT, multicenter European | 12 months | Symptomatic PAD due to a maximum of two focal de novo atherosclerotic target lesions in one or more infrapopliteal vessels | 140 | 63.5 | 36.5 | Treatment of the infrapopliteal occlusive lesions of CLI with everolimus stents demonstrated an 85% patency vs 54% with BMS at 12 months, decrease in restenosis, as well as statistically significant independence from revascularization |

| YUKON-BTX | Double-blind RCT | 12 months | Rutherford class 3–5, presence of a single primary target lesion in a native infrapopliteal artery that was 2.5–3.5 mm in diameter and that did not exceed 45 mm in length | 161 | 66.5 | 33.5 | BMS placement was associated with a hazard ratio for restenosis of 3.2 (95% CI 1.5 to 6.7; p = 0.003) compared with sirolimus-eluting stents (SES) after 1 year. No significant differences between the study groups concerning mortality and amputation rates were observed, but mean ABI and Rutherford scores showed significant improvements in sirolimus group |

| IN.PACT DEEP CLI | Prospective multicenter RCT | 12 months | Rutherford class 4–6 symptomatic CLI patients; reference vessel diameters between 2 and 4 mm; single or multiple lesions with ≥ 70% stenosis of different lengths in one or more main afferent crural vessels including tibioperoneal trunk | 358 | 74.3 | 25.7 | IN.PACT Amphirion drug-eluting balloons demonstrated comparable and non-inferior efficacy to PTA in CLI patients. The overall complication rate, a composite of core laboratory-adjudicated incidence of vasospasm, abrupt closure, vessel recoil, thrombus, and perforation, was higher in the IA-DEB arm versus the PTA arm (9.7 vs 3.4%; p = 0.035). Major amputation-free survival had a trend favoring DEB |

| IDEAS | Prospective RCT | 6 months | Rutherford classes 3–6 and angiographically documented infrapopliteal disease with a minimum lesion length of 70 mm | 50 | 76 | 34 | DES are related with significantly lower residual immediate post-procedure stenosis and have shown significantly reduced vessel restenosis at 6 months |

Fig. 1.

Trends and % women in cardiovascular clinical trials 1994–2017

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Women with PAD present on average 10–20 years later than men [20]. Around 20–30% of women aged 70 years or older are affected by PAD [21, 22]. This is hypothesized to be secondary to the loss of the vascular protective effects of estrogen which promotes vasodilation and has anti-oxidative effects. In a study of > 370,000 surgical inpatients with PAD, Vouyouka et al. found that women were more likely to be older, obese, and black [23•]. Overall risk factors for PAD remain similar among men and women, including smoking, age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia [3]. Diabetes and hyperlipidemia have been shown to increase the risk of intermittent claudication by fourfold in women [24, 25]. Importantly, ethnic differences have been shown to affect the prevalence of PAD as well, with the highest prevalence of PAD among non-Hispanic black women over the age of 70 (25%) [26•]. Other studies have shown association between obesity [27], levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) [28, 29], osteopenia/osteoporosis [30, 31], hypothyroidism, and PAD. In the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) [29], women had higher levels of CRP than men, after adjustment for comorbidities, hormonal status, and age. Conflicting data has emerged for the association between hormone replacement therapy and PAD in women. In the Women Health Initiative (WHI) and Heart and Estrogen/Progestin replacement (HERS) studies, no benefit was observed from HRT use for PAD or CAD. Conversely, the Rotterdam study showed a 52% decreased risk of PAD in women who used HRT for > 1 year [32–34]. Interestingly, vascular complications associated with pregnancy have also been associated with an increased risk of PAD. The Cardiovascular Health After Maternal Placental Syndrome (CHAMPS) study showed a threefold increased risk of PAD and twofold increased risk of coronary artery and cerebrovascular disease in patients with maternal placental syndromes, including pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension, placental abruption, and placental infarction [35]. The mechanisms for this association are unclear, although one likely hypothesis is underlying endothelial dysfunction.

The treatment of risk factors varies by gender. In the REACH registry [4], consisting of > 68,000 outpatients, risk factor control was less frequently observed in patients with diagnosis of PAD. Optimal risk factor control was twice as likely for men than women despite a higher incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and elevated total cholesterol in women.

Symptoms

Both men and women present with typical, atypical, or asymptomatic PAD. Studies have shown that the majority of PAD patients do not have typical claudication [11, 36]. Asymptomatic disease is defined as absence of exertional leg symptoms in the presence of an ankle-brachial index (ABI) < 0.90, while atypical symptoms are defined by leg symptoms present at rest and exercise [37, 38]. In the Women Health and Aging study (WHAS), of the 933 women enrolled, 35% (n = 328) had an ABI of 0.90; of these, 328 patients (63%) had no exertional leg symptoms [39]. Importantly, asymptomatic PAD has been shown to be more common in women than in men (13 vs 9%; p < 0.03) [40]. When symptomatic, women seek medical attention with more complex (multilevel) and severe disease including critical limb ischemia (CLI) [16•, 40, 41]. In patients with CLI, women had a twofold higher incidence of femoropopliteal disease compared to men [42]. This finding was reproduced in another patient cohort undergoing angioplasty that showed pronounced femoropopliteal disease in women while men had more below-the-knee disease [43]. Additionally, women have greater lower extremity functional impairment [8], with shorter treadmill distance to intermittent claudication [44], shorter maximal treadmill walking distance [8, 44], and poorer quality of life scores compared to men [45]. Other studies have demonstrated a higher prevalence of asymptomatic disease in women, which may lead to a late presentation, thus contributing to severe disease or CLI [41].

Treatment

The principle components of PAD treatment consist of supervised exercise therapy, pharmacological treatment, and lower extremity revascularization. Patients with PAD are less likely to receive guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) than are patients with other forms of cardiovascular disease, including CAD [46–48]. For example, in one study on secondary prevention of PAD, statin use was reported in only 31%, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use in 25%, and aspirin use in 36% [48]. Data also exists on suboptimal use of systemic vascular treatment or lack of adherence to standard therapy. In the NHANES study, only 24–34% adherence to preventive therapy was reported [48]. CHAMPS study cited similar suboptimal use of GDMT but was particularly notable for lower rates in women and older patients [31]. In terms of intensity of treatment with standard pharmacologic agents, men were more likely to receive all agents (antiplatelets, statins, and angiotensin enzyme inhibitors) than women (22.4 vs 18.2%) [31]. This finding was reproduced in another study from Quebec which showed that men were more likely to receive statins, antiplatelet agents, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors than women (22.4 vs 18.2%, p < 0.001) [31].

Patients with PAD experience a profound limitation in exercise performance. There is evidence of a well-established benefit following a typical 12-week exercise training program [49, 50]. Lower extremity exercise training has been shown to increase time to claudication, increase distance before claudication, and increase overall walking distance [51]. Unfortunately, women with PAD have been shown to be less responsive to exercise rehabilitation programs [52], particularly diabetic women. This may partly be due to a greater impairment in calf muscle oxygen saturation during and following exercise [53]. Gardner et al. reported that improvements in absolute walking distance were significantly less for women than men after 1 year of standard exercise therapy. Women also reported less subjective improvement on walking impairment questionnaire domains [54]. These differences have been attributed to lower hemoglobin saturation during ambulation [53], poorer leg strength [55], higher inflammation, higher level of oxidative stress, and insulin resistance [53].

Endovascular revascularization and open bypass surgery are two strategies for disabling claudication after failure of medical therapy or for those with CLI. Although the choice of procedure depends on many lesion characteristics including lesion site [56, 57], the 2016 AHA/ACC Guidelines recommend an endovascular approach first for both lifestyle limiting claudication and CLI. While data has been equivocal, sex differences have also been reported in lower extremity endovascular versus bypass treatment. Using 69 million discharge records from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 1998 to 2006, Roe et al. reported discrepancies in the proportion of endovascular procedures being performed in women compared to men. Women were less likely to undergo amputation or open vascular surgery than men. Women, however, were more likely to undergo an endovascular procedure during hospitalization [58, 59]. Several possible reasons have been cited for lower bypass rates, including the observation that women with PAD are generally older with more advanced disease, comorbidities, and may have smaller vessel size precluding bypass.

Carotid Artery Stenosis and Management

Women have a greater risk of disabling stroke (58 vs 48%) and stroke-related mortality (20 vs 14%) [60]. Stroke-related mortality has not changed over the past 50 years in women and is attributed to older age at onset of stroke among women [60]. Multiple trials have demonstrated a reduction in the risk of stroke in select patients with symptomatic internal carotid artery disease and to a lesser extent, in those with asymptomatic carotid artery disease [61–63]. However, it is noteworthy that women comprised only 28–34% of enrolled patients in these trials. In an analysis of the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) and ACAS trial, 30-day risk for death was higher in women than in men (2.3 vs 0.8%, p = 0.002), owing to higher risk of fatal stroke [64]. Both men and women benefited from carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for stroke prevention. However, in another study, the risk of stroke or death within 30 days after CEA in symptomatic patients was greater in women (8.7%) vs men (6.8%) [65], a finding which was reproduced in a systematic review of 36 studies [66]. However, other studies have shown no significant difference in complications and mortality following CEA [67, 68]. Regarding carotid artery stenting, women have worse outcomes, including higher rates of in-hospital mortality and stroke [69]. Risk of stroke or mortality was 1.7-fold higher in symptomatic women and 3.4-fold higher in asymptomatic women with carotid artery stenosis (CAS) compared to CEA. Asymptomatic women experienced worse outcomes compared to men, with higher stroke rates after CEA and higher myocardial infarction rates after both CEA and CAS [70].

Quality of Life

Quality of life scores have become an important tool to assess treatment effectiveness in the general population. Multiple studies have shown worse health status and health-related quality of life in women when compared with men suffering from PAD [10, 12, 13]. In addition, functional status has been determined to be significantly lower for women [45]. This was associated with greater mood disturbances [12]. Female gender has been adversely associated with durability of the revascularization or the quality of life following revascularization for claudication or CLI [71]. In a longitudinal study of a large PAD population, women with PAD were found to have compromised health status both at diagnosis and 12 months after follow-up. The mechanism for poor health status in these women was thought to be associated with lower education and lack of social support (women were less likely to have a partner) [72].

Outcomes/Prognosis

Outcome trials of endovascular or surgical revascularization in men and women have reported conflicting results. Several studies have reported an unfavorable impact of sex on outcomes after peripheral revascularization procedures Women tend to have higher perioperative mortality whether undergoing surgical or endovascular procedures [73, 74]. Furthermore, they have inferior patency rates after surgical revascularization [75–77], higher risk of stent thrombosis with endovascular revascularization [77], wound complications [78], and bleeding events [23•]. On the other hand, multiple other studies, including some systematic reviews, have found no sex difference in patency rates and amputation-free survival [79–81].

PAD is associated with increased risk of CVD mortality and morbidity. A low ABI (≤ 0.9) is associated with a threefold increased risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in both men and women [82]. Women with PAD have a two- to fourfold increased risk of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity compared to women without PAD [15]. Compared to men, women are more likely to be admitted for acute myocardial infarction [83], more likely to be admitted emergently with longer hospital stays and more likely to require rehabilitation or nursing home care [16•, 59, 84]. Similarly, women with CLI have higher in-hospital mortality after both endovascular treatments and open surgery [85].

Conclusions

PAD remains a major healthcare problem. It remains underdiagnosed and understudied in women. The major challenge in PAD treatment in women is their late presentation and the higher prevalence of asymptomatic disease which may lead to more advanced disease at presentation and a higher risk of adverse events and mortality. Concerted research efforts should be carried out to further determine the effects of sex on different aspects of PAD including risk factors, clinical burden, treatment, and outcomes. In addition, campaigns to raise awareness among clinicians and the general public should be undertaken. Efforts along the lines of the “National Wear Red Day” campaign by the AHA should be pursued aggressively to increase awareness.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Qurat-ul-ain Jelani, Mikhail Petrov, Sara C. Martinez, Lene Holmvang, Khaled Al-Shaibi, and Mirvat Alasnag declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Women and Ischemic Heart Disease

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

- 1.Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, Aboyans V, Denenberg JO, McDermott MM, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9901):1329–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sampson UK, Fowkes FG, McDermott MM, Criqui MH, Aboyans V, Norman PE, et al. Global and regional burden of death and disability from peripheral artery disease: 21 world regions, 1990 to 2010. Glob Heart. 2014;9(1):145–58 e21. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):480–486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW, D’Agostino R, Sr, Ohman EM, Rother J, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2007;297(11):1197–1206. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.11.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahoney EM, Wang K, Cohen DJ, Hirsch AT, Alberts MJ, Eagle K, Mosse F, Jackson JD, Steg PG, Bhatt DL, on behalf of the REACH Registry Investigators One-year costs in patients with a history of or at risk for atherothrombosis in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1(1):38–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.775247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch AT, Hartman L, Town RJ, Virnig BA. National health care costs of peripheral arterial disease in the Medicare population. Vasc Med. 2008;13(3):209–215. doi: 10.1177/1358863X08089277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirsch AT, Allison MA, Gomes AS, Corriere MA, Duval S, Ershow AG, Hiatt WR, Karas RH, Lovell MB, McDermott MM, Mendes DM, Nussmeier NA, Treat-Jacobson D, on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention. Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia. Council on Clinical Cardiology. Council on Epidemiology and Prevention A call to action: women and peripheral artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(11):1449–1472. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824c39ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, Criqui MH, Guralnik JM, Celic L, et al. Sex differences in peripheral arterial disease: leg symptoms and physical functioning. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(2):222–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safley DM, House JA, Laster SB, Daniel WC, Spertus JA, Marso SP. Quantifying improvement in symptoms, functioning, and quality of life after peripheral endovascular revascularization. Circulation. 2007;115(5):569–575. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.643346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mastenbroek MH, Hoeks SE, Pedersen SS, Scholte Op Reimer WJ, Voute MT, Verhagen HJ. Gender disparities in disease-specific health status in postoperative patients with peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;43(4):433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDermott MM, Mehta S, Greenland P. Exertional leg symptoms other than intermittent claudication are common in peripheral arterial disease. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(4):387–392. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oka RK, Szuba A, Giacomini JC, Cooke JP. Gender differences in perception of PAD: a pilot study. Vasc Med. 2003;8(2):89–94. doi: 10.1191/1358863x03vm479oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloemenkamp DG, Mali WP, Tanis BC, van den Bosch MA, Kemmeren JM, Algra A, et al. Functional health and well-being of relatively young women with peripheral arterial disease is decreased but stable after diagnosis. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(1):104–110. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(02)75465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smolderen KG, Spertus JA, Vriens PW, Kranendonk S, Nooren M, Denollet J. Younger women with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease are at increased risk of depressive symptoms. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(3):637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Higgins JA. Epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease in women. J Epidemiol. 2003;13(1):1–14. doi: 10.2188/jea.13.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson EA, Munir K, Schreiber T, Rubin JR, Cuff R, Gallagher KA, Henke PK, Gurm HS, Grossman PM. Impact of sex on morbidity and mortality rates after lower extremity interventions for peripheral arterial disease: observations from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(23):2525–2530. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vyas MV, Mrkobrada M, Donner A, Hackam DG. Underrepresentation of peripheral artery disease in modern cardiovascular trials: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(5):4875–4876. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoel AW, Kayssi A, Brahmanandam S, Belkin M, Conte MS, Nguyen LL. Under-representation of women and ethnic minorities in vascular surgery randomized controlled trials. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50(2):349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melloni C, Berger JS, Wang TY, Gunes F, Stebbins A, Pieper KS, Dolor RJ, Douglas PS, Mark DB, Newby LK. Representation of women in randomized clinical trials of cardiovascular disease prevention. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(2):135–142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.868307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen L, Liles DR, Lin PH, Bush RL. Hormone replacement therapy and peripheral vascular disease in women. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;38(6):547–556. doi: 10.1177/153857440403800609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Manolio TA, Polak J, Fried LP, Borhani NO, Wolfson SK. Ankle-arm index as a marker of atherosclerosis in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Cardiovascular Heart Study (CHS) collaborative research group. Circulation. 1993;88(3):837–845. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.88.3.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Criqui MH, Fronek A, Barrett-Connor E, Klauber MR, Gabriel S, Goodman D. The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in a defined population. Circulation. 1985;71(3):510–515. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.71.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vouyouka AG, Egorova NN, Salloum A, Kleinman L, Marin M, Faries PL, Moscowitz A. Lessons learned from the analysis of gender effect on risk factors and procedural outcomes of lower extremity arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(5):1196–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.05.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerhard M, Baum P, Raby KE. Peripheral arterial-vascular disease in women: prevalence, prognosis, and treatment. Cardiology. 1995;86(4):349–355. doi: 10.1159/000176899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Update on some epidemiologic features of intermittent claudication: the Framingham study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1985;33(1):13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1985.tb02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eraso LH, Fukaya E, Mohler ER, 3rd, Xie D, Sha D, Berger JS. Peripheral arterial disease, prevalence and cumulative risk factor profile analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(6):704–711. doi: 10.1177/2047487312452968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu B, Zhou J, Waring ME, Parker DR, Eaton CB. Abdominal obesity and peripheral vascular disease in men and women: a comparison of waist-to-thigh ratio and waist circumference as measures of abdominal obesity. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208(1):253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Plasma concentration of C-reactive protein and risk of developing peripheral vascular disease. Circulation. 1998;97(5):425–428. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.97.5.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lakoski SG, Cushman M, Criqui M, Rundek T, Blumenthal RS, D’Agostino RB, Jr, D'Agostino RB, Jr, Herrington DM. Gender and C-reactive protein: data from the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) cohort. Am Heart J. 2006;152(3):593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aronow WS. Osteoporosis, osteopenia, and atherosclerotic vascular disease. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7(1):21–26. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.20599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paquet M, Pilon D, Tetrault JP, Carrier N. Protective vascular treatment of patients with peripheral arterial disease: guideline adherence according to year, age and gender. Can J Public Health. 2010;101(1):96–100. doi: 10.1007/BF03405572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, Wu L, Barad D, Barnabei VM, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA. 2007;297(13):1465–1477. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.13.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grady D, Herrington D, Bittner V, Blumenthal R, Davidson M, Hlatky M, Hsia J, Hulley S, Herd A, Khan S, Newby LK, Waters D, Vittinghoff E, Wenger N, HERS Research Group Cardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy: Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study follow-up (HERS II) JAMA. 2002;288(1):49–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsia J, Simon JA, Lin F, Applegate WB, Vogt MT, Hunninghake D, Carr M. Peripheral arterial disease in randomized trial of estrogen with progestin in women with coronary heart disease: the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study. Circulation. 2000;102(18):2228–2232. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.18.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Cardiovascular health after maternal placental syndromes (CHAMPS): population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1797–1803. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, Regensteiner JG, Creager MA, Olin JW, Krook SH, Hunninghake DB, Comerota AJ, Walsh ME, McDermott M, Hiatt WR. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1317–1324. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirsch AT, Hiatt WR, Committee PS PAD awareness, risk, and treatment: new resources for survival--the USA PARTNERS program. Vasc Med. 2001;6(3 Suppl):9–12. doi: 10.1177/1358836X0100600i103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, Guralnik JM, Criqui MH, Dolan NC, et al. Leg symptoms in peripheral arterial disease: associated clinical characteristics and functional impairment. JAMA. 2001;286(13):1599–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.13.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDermott MM, Fried L, Simonsick E, Ling S, Guralnik JM. Asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease is independently associated with impaired lower extremity functioning: the women's health and aging study. Circulation. 2000;101(9):1007–1012. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sigvant B, Wiberg-Hedman K, Bergqvist D, Rolandsson O, Andersson B, Persson E, Wahlberg E. A population-based study of peripheral arterial disease prevalence with special focus on critical limb ischemia and sex differences. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(6):1185–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brevetti G, Bucur R, Balbarini A, Melillo E, Novo S, Muratori I, Chiariello M. Women and peripheral arterial disease: same disease, different issues. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2008;9(4):382–388. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3282f03b90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ortmann J, Nuesch E, Traupe T, Diehm N, Baumgartner I. Gender is an independent risk factor for distribution pattern and lesion morphology in chronic critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(1):98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diehm N, Shang A, Silvestro A, Do DD, Dick F, Schmidli J, Mahler F, Baumgartner I. Association of cardiovascular risk factors with pattern of lower limb atherosclerosis in 2659 patients undergoing angioplasty. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31(1):59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gardner AW. Sex differences in claudication pain in subjects with peripheral arterial disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(11):1695–1698. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collins TC, Suarez-Almazor M, Bush RL, Petersen NJ. Gender and peripheral arterial disease. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(2):132–140. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishnamurthy V, Munir K, Rectenwald JE, Mansour A, Hans S, Eliason JL, Escobar GA, Gallagher KA, Grossman PM, Gurm HS, Share DA, Henke PK. Contemporary outcomes with percutaneous vascular interventions for peripheral critical limb ischemia in those with and without poly-vascular disease. Vasc Med. 2014;19(6):491–499. doi: 10.1177/1358863X14552013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Selvin E, Hirsch AT. Contemporary risk factor control and walking dysfunction in individuals with peripheral arterial disease: NHANES 1999–2004. Atherosclerosis. 2008;201(2):425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pande RL, Perlstein TS, Beckman JA, Creager MA. Secondary prevention and mortality in peripheral artery disease: National Health and Nutrition Examination Study, 1999 to 2004. Circulation. 2011;124(1):17–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hiatt WR, Regensteiner JG, Hargarten ME, Wolfel EE, Brass EP. Benefit of exercise conditioning for patients with peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 1990;81(2):602–609. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.81.2.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hiatt WR, Wolfel EE, Meier RH, Regensteiner JG. Superiority of treadmill walking exercise versus strength training for patients with peripheral arterial disease. Implications for the mechanism of the training response. Circulation. 1994;90(4):1866–1874. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.4.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parmenter BJ, Raymond J, Dinnen P, Singh MA. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials: walking versus alternative exercise prescription as treatment for intermittent claudication. Atherosclerosis. 2011;218(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gardner AW, Parker DE, Montgomery PS, Blevins SM. Diabetic women are poor responders to exercise rehabilitation in the treatment of claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(4):1036–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gardner AW, Parker DE, Montgomery PS, Blevins SM, Nael R, Afaq A. Sex differences in calf muscle hemoglobin oxygen saturation in patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.12.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gommans LN, Scheltinga MR, van Sambeek MR, Maas AH, Bendermacher BL, Teijink JA. Gender differences following supervised exercise therapy in patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62(3):681–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gardner AW, Montgomery PS, Blevins SM, Parker DE. Gender and ethnic differences in arterial compliance in patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(3):610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jude EB, Eleftheriadou I, Tentolouris N. Peripheral arterial disease in diabetes--a review. Diabet Med. 2010;27(1):4–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malgor RD, Alahdab F, Elraiyah TA, Rizvi AZ, Lane MA, Prokop LJ, et al. A systematic review of treatment of intermittent claudication in the lower extremities. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(3 Suppl):54S–73S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rowe VL, Weaver FA, Lane JS, Etzioni DA. Racial and ethnic differences in patterns of treatment for acute peripheral arterial disease in the United States, 1998–2006. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(4 Suppl):21S–26S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Egorova N, Vouyouka AG, Quin J, Guillerme S, Moskowitz A, Marin M, Faries PL. Analysis of gender-related differences in lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(2):372–8 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carandang R, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Kelly-Hayes M, Kase CS, Kannel WB, Wolf PA. Trends in incidence, lifetime risk, severity, and 30-day mortality of stroke over the past 50 years. JAMA. 2006;296(24):2939–2946. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Methods, patient characteristics, and progress. Stroke. 1991;22(6):711–720. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.22.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet. 1998;351(9113):1379–87. [PubMed]

- 63.Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. JAMA. 1995;273(18):1421–8. [PubMed]

- 64.Alamowitch S, Eliasziw M, Barnett HJ, North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy T, Group ASAT, Carotid Endarterectomy Trial G The risk and benefit of endarterectomy in women with symptomatic internal carotid artery disease. Stroke. 2005;36(1):27–31. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000149622.12636.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP, Barnett HJ, Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists C. Endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis in relation to clinical subgroups and timing of surgery. Lancet. 2004;363(9413):915–924. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15785-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rothwell PM, Slattery J, Warlow CP. Clinical and angiographic predictors of stroke and death from carotid endarterectomy: systematic review. BMJ. 1997;315(7122):1571–1577. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7122.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yavas S, Mavioglu L, Kocabeyoglu S, Iscan HZ, Ulus AT, Bayazit M, Birincioglu CL. Is female gender really a risk factor for carotid endarterectomy? Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24(6):775–785. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rockman CB, Castillo J, Adelman MA, Jacobowitz GR, Gagne PJ, Lamparello PJ, Landis R, Riles TS. Carotid endarterectomy in female patients: are the concerns of the asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis study valid? J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(2):236–240. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.111804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vouyouka AG, Egorova NN, Sosunov EA, Moskowitz AJ, Gelijns A, Marin M, Faries PL. Analysis of Florida and New York state hospital discharges suggests that carotid stenting in symptomatic women is associated with significant increase in mortality and perioperative morbidity compared with carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(2):334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bisdas T, Egorova N, Moskowitz AJ, Sosunov EA, Marin ML, Faries PL, Vouyouka AG. The impact of gender on in-hospital outcomes after carotid endarterectomy or stenting. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44(3):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wann-Hansson C, Hallberg IR, Risberg B, Lundell A, Klevsgard R. Health-related quality of life after revascularization for peripheral arterial occlusive disease: long-term follow-up. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51(3):227–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dreyer RP, van Zitteren M, Beltrame JF, Fitridge R, Denollet J, Vriens PW, Spertus JA, Smolderen KG. Gender differences in health status and adverse outcomes among patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;4(1):e000863. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hultgren R, Olofsson P, Wahlberg E. Sex-related differences in outcome after vascular interventions for lower limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35(3):510–516. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.120043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McCoach CE, Armstrong EJ, Singh S, Javed U, Anderson D, Yeo KK, et al. Gender-related variation in the clinical presentation and outcomes of critical limb ischemia. Vasc Med. 2013;18(1):19–26. doi: 10.1177/1358863X13475836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.AhChong AK, Chiu KM, Wong M, Yip AW. The influence of gender difference on the outcomes of infrainguinal bypass for critical limb ischaemia in Chinese patients. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23(2):134–139. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abbott WM, Green RM, Matsumoto T, Wheeler JR, Miller N, Veith FJ, et al. Prosthetic above-knee femoropopliteal bypass grafting: results of a multicenter randomized prospective trial. Above-Knee Femoropopliteal Study Group. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(97)70317-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ballard JL, Bergan JJ, Singh P, Yonemoto H, Killeen JD. Aortoiliac stent deployment versus surgical reconstruction: analysis of outcome and cost. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28(1):94–101. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(98)70204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nguyen LL, Brahmanandam S, Bandyk DF, Belkin M, Clowes AW, Moneta GL, Conte MS. Female gender and oral anticoagulants are associated with wound complications in lower extremity vein bypass: an analysis of 1404 operations for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46(6):1191–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eugster T, Gurke L, Obeid T, Stierli P. Infrainguinal arterial reconstruction: female gender as risk factor for outcome. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;24(3):245–248. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Harthun NL, Cheanvechai V, Graham LM, Freischlag JA, Gahtan V. Arterial occlusive disease of the lower extremities: do women differ from men in occurrence of risk factors and response to invasive treatment? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127(2):318–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ballotta E, Gruppo M, Lorenzetti R, Piatto G, DaGiau G, Toniato A. The impact of gender on outcome after infrainguinal arterial reconstructions for peripheral occlusive disease. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(2):343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ankle Brachial Index C, Fowkes FG, Murray GD, Butcher I, Heald CL, Lee RJ, et al. Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham Risk Score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(2):197–208. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hussain MA, Lindsay TF, Mamdani M, Wang X, Verma S, Al-Omran M. Sex differences in the outcomes of peripheral arterial disease: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4(1):E124–E131. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20150107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Riess HC, Debus ES, Heidemann F, Stoberock K, Grundmann RT, Behrendt CA. Gender differences in endovascular treatment of infrainguinal peripheral artery disease. Vasa. 2017;46(4):296–303. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lo RC, Bensley RP, Dahlberg SE, Matyal R, Hamdan AD, Wyers M, Chaikof EL, Schermerhorn ML. Presentation, treatment, and outcome differences between men and women undergoing revascularization or amputation for lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(2):409–18 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.07.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]