Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci for type 2 diabetes-attributed end-stage kidney disease in African Americans (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

End-stage kidney disease (ESKD) is a significant public health concern disproportionately affecting African Americans (AAs). Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the leading cause of ESKD in the USA, and efforts to uncover genetic susceptibility to diabetic kidney disease (DKD) have had limited success. A prior genome-wide association study (GWAS) in AAs with T2D-ESKD was expanded with additional AA cases and controls and genotypes imputed to the higher density 1000 Genomes reference panel. The discovery analysis included 3432 T2D-ESKD cases and 6977 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls (N = 10,409), followed by a discrimination analysis in 2756 T2D non-nephropathy controls to exclude T2D-associated variants.

Results

Six independent variants located in or near RND3/RBM43, SLITRK3, ENPP7, GNG7, and APOL1 achieved genome-wide significant association (P < 5 × 10−8) with T2D-ESKD. Following extension analyses in 1910 non-diabetic ESKD cases and 908 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls, a meta-analysis of 5342 AA all-cause ESKD cases and 6977 AA non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls revealed an additional novel all-cause ESKD locus at EFNB2 (rs77113398; P = 9.84 × 10–9; OR = 1.94). Exclusion of APOL1 renal-risk genotype carriers identified two additional genome-wide significant T2D-ESKD-associated loci at GRAMD3 and MGAT4C. A second variant at GNG7 (rs373971520; P = 2.17 × 10–8, OR = 1.46) remained associated with all-cause ESKD in the _APOL1_-negative analysis.

Conclusions

Findings provide further evidence for genetic factors associated with advanced kidney disease in AAs with T2D.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40246-019-0205-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: African Americans, Genome-wide association study, Type 2 diabetes, Diabetic kidney disease, End-stage kidney disease

Introduction

Increasing evidence suggests that genetic factors play a major role in susceptibility to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). This is particularly relevant in African Americans (AAs) where incidence rates of ESKD are more than threefold greater than European Americans (EAs) [1]. The mortality rates for ESKD, dialysis, and transplant patients are 136, 166, and 30 per 1000 patient-years, respectively, and account for 7.2% of Medicare-paid claims costs [1]. Diabetes, of which 95% of patients have type 2 diabetes (T2D), remains the leading reported cause of ESKD in the USA accounting for > 44% of cases [1]. Improvements in glycemic, lipid, and blood pressure control have not markedly reduced the prevalence of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) [1, 2]. In addition, familial aggregation of DKD is independent from socioeconomic status and established environmental risk factors [3, 4]. Although the G1 and G2 alleles in the apolipoprotein L1 gene (APOL1) contribute to 50–70% of non-diabetic ESKD in AAs, they do not fully explain the excess risk of T2D-attributed ESKD (T2D-ESKD) in this population [5–7].

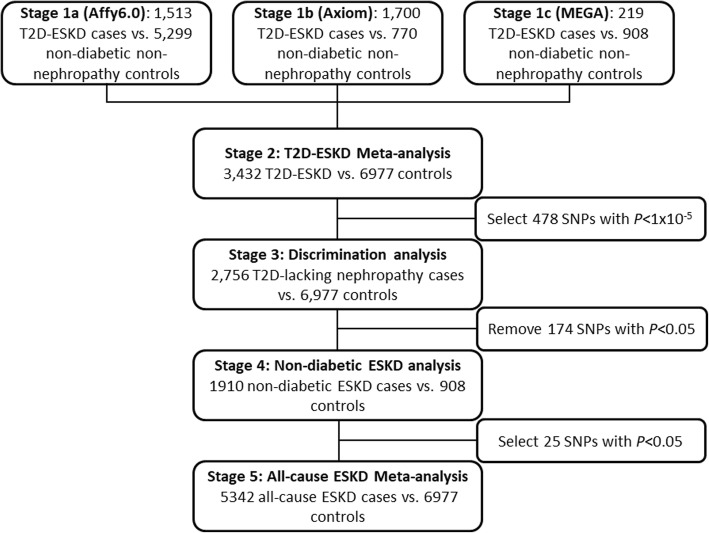

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified > 70 genome-wide significant variants associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD), albuminuria, or renal function in European ancestry populations [8–11]. However, few loci were associated with DKD in diverse populations and they do not consistently replicate, in part due to limited sample sizes [12–18]. The etiology of kidney complications in patients with T2D is likely more heterogeneous than in patients with type 1 diabetes [16]. Therefore, careful phenotyping and larger sample sizes are required to improve statistical power. To explore the genetic architecture of advanced kidney disease in T2D, we extended our previous GWAS (2890 ESKD patients and 1719 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) efforts in a larger sample of AAs with severe kidney disease. Association analyses were performed in six independent AA cohorts (Wake Forest School of Medicine, WFSM; Family Investigation of Nephropathy and Diabetes, FIND; Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, ARIC; Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, MESA; Jackson Heart Study, JHS; and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults, CARDIA) for T2D-ESKD or non-diabetic ESKD through a multi-stage study design (Fig. 1). This encompassed 15,075 AAs classified into four phenotypic groups: T2D-ESKD cases (N = 3432), non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls (N = 6977), T2D-lacking nephropathy controls (N = 2756), and non-diabetic ESKD cases (N = 1910).

Fig. 1.

Workflow of T2D-ESKD GWAS in AAs (baseline model)

In the discovery stage, GWAS was performed in 3432 T2D-ESKD cases and 6977 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls, followed by a discrimination analysis to exclude T2D-associated loci in 2756 T2D non-nephropathy controls. Extension analyses were performed in 1910 AAs with non-diabetic ESKD and 908 non-nephropathy controls to assess the contribution of T2D-ESKD-associated loci to non-diabetic kidney disease. A meta-analysis of diabetic and non-diabetic ESKD cases assessed genetic associations in all-cause ESKD. APOL1-associated forms of non-diabetic kidney disease and T2D often co-exist in patients. As such, many diabetic patients with kidney disease may be misclassified as having DKD, since diagnostic kidney biopsies are usually not performed. Herein, a second GWAS analysis excluding individuals with APOL1 renal-risk genotypes was performed to minimize misclassification of T2D-ESKD.

Results

Study overview

This study has > 80% power to detect common variants (MAF ≥ 0.10) with moderate effect (OR ≥ 1.3) at a significance level of 5 × 10−8 (http://csg.sph.umich.edu/abecasis/cats/). In all, seven genome-wide significant loci (P < 5 × 10−8) associated with T2D-ESKD were identified in either the baseline model (RND3/RBM43, SLITRK3, ENPP7, GNG7, and APOL1) or _APOL1_-negative model (ENPP7, GRAMD3, and MGAT4C). In addition to APOL1, two loci, EFNB2 and GNG7, also reached genome-wide significance in the all-cause ESKD meta-analysis under either the baseline or _APOL1_-negative models.

Clinical characteristics of study participants

Tables 1 and 2 include detailed characteristics of study participants. ESKD cases were recruited from the WFSM (Affy6.0, Axiom, and MEGA), FIND, and ARIC studies. Individuals with T2D-ESKD or T2D-lacking nephropathy were older (or of similar age) compared to the non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls at recruitment. However, the average age at diagnosis of T2D in T2D-ESKD cases and T2D-lacking nephropathy controls were younger than non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls at recruitment. All T2D non-nephropathy controls and non-diabetic, non-nephropathy controls had normal eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73m2. In addition, non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls had fasting glucose levels < 126 mg/dl. Controls with T2D-lacking nephropathy were more obese than T2D-ESKD or non-diabetic ESKD cases and non-diabetic, non-nephropathy controls, except that T2D-ESKD cases in ARIC were more obese than the other groups.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of participants from the Affy6.0 datasets (stage 1a)

| WFSM | FIND | ARIC | JHS | MESA | CARDIA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2D-ESKD | Non-diabetic non-nephropathy | T2D-ESKD | T2D-lacking nephropathy | T2D-ESKD | Non-diabetic non-nephropathy | T2D-lacking nephropathy | Non-diabetic non-nephropathy | T2D-lacking nephropathy | Non-diabetic non-nephropathy | T2D-lacking nephropathy | Non-diabetic non-nephropathy | T2D-lacking nephropathy | |

| N | 790 | 891 | 627 | 299 | 96 | 1318 | 807 | 1569 | 343 | 774 | 278 | 747 | 165 |

| Females (%) | 63 | 56 | 54 | 76 | 65 | 62 | 63 | 59 | 68 | 54 | 53 | 60 | 66 |

| Age (years) | 62.1 ± 10.0 | 47.2 ± 11.8 | 56.84 ± 12.0 | 59.8 ± 11.1 | 68.2 ± 6.6 | 60.2 ± 6.1 | 60.3 ± 5.8 | 53.4 ± 11.6 | 59.3 ± 9.1 | 63.9 ± 9.2 | 65.6 ± 9.2 | 47.6 ± 5.0 | 49.4 ± 4.3 |

| Age of onset of diabetes (years) | 40.4 ± 11.8 | – | – | – | 47.3 ± 10.4 | – | 57.4 ± 10.8 | - | 44.9 ± 11.3 | – | – | – | 32.3 ± 7.9 |

| Duration of diabetes prior to ESKD (years) | 18.5 ± 9.6 | – | – | – | 20.5 ± 8.6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Duration of ESKD (years) | 3.3 ± 3.6 | – | – | – | 0.6 ± 1.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Fasting serum glucose (mg/dl) | 193 ± 64 | – | – | – | 293 ± 115 | 105 ± 9 | 192 ± 94 | 90 ± 8 | 156 ± 66 | 98 ± 10 | 164 ± 59 | 96 ± 9 | 167 ± 66 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | - | 96.7 ± 21.3 | – | – | - | 78.6 ± 12.5 | 79.5 ± 12.6 | 95.5 ± 17.6 | 92.7 ± 18.5 | 78.9 ± 12.1 | 82.9 ± 16.0 | 91.1 ± 13.1 | 95.6 ± 13.6 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.8 ± 7.0 | 30.0 ± 7.0 | – | – | 33.4 ± 7.3 | 29.2 ± 6.1 | 32.2 ± 6.8 | 31.6 ± 7.7 | 35.4 ± 7.7 | 29.8 ± 5.8 | 31.8 ± 6.5 | – | – |

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of participants genotyped using Axiom and MEGA arrays (stage 1b and 1c)

| WFSM-Axiom | WFSM-MEGA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2D-ESKD | Non-diabetic non-nephropathy | T2D-lacking nephropathy | T2D-ESKD | Non-diabetic non-nephropathy | T2D-lacking nephropathy | Non-diabetic ESKD | |

| N | 1700 | 770 | 663 | 219 | 908 | 201 | 1910 |

| Females (%) | 56 | 49 | 64 | 49 | 59 | 62 | 41 |

| Age (years) | 62.0 ± 10.8 | 47.9 ± 12.0 | 55.7 ± 11.6 | 62.0 ± 11.0 | 44.8 ± 13.9 | 55.8 ± 9.5 | 55.4 ± 14.4 |

| Age of onset of diabetes (years) | 39.7 ± 12.8 | – | 46.2 ± 12.3 | 37.8 ± 9.6 | – | 43.7 ± 10.3 | – |

| Duration of diabetes prior to ESKD (years) | 19.1 ± 10.0 | – | – | 20.4 ± 9.5 | – | – | – |

| Duration of ESKD (years) | 3.6 ± 3.6 | – | – | 4.1 ± 3.1 | – | – | 6.2 ± 5.8 |

| Fasting serum glucose (mg/dl) | 184 ± 89 | 96 ± 22 | 163 ± 92 | 127 ± 33 | 96 ± 11 | 174 ± 62 | 90 ± 3 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | – | 96.0 ± 20.8 | 91.3 ± 19.7 | – | 85.9 ± 17.3 | 95.2 ± 17.3 | – |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.7 ± 7.1 | 29.6 ± 7.4 | 33.1 ± 7.8 | 30.8 ± 7.0 | 29.7 ± 6.6 | 33.0 ± 6.5 | 27.8 ± 7.2 |

Stage 1 and stage 2 T2D-ESKD association analysis

In stage 1 discovery, GWAS was conducted separately in three datasets: (1) 1513 T2D-ESKD cases and 5299 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls genotyped on Affy6.0, contributed by WFSM, FIND, ARIC, JHS, MESA, and CARDIA (stage 1a); (2) 1700 T2D-ESKD cases and 770 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls from WFSM genotyped with Axiom Biobank genotyping array (stage 1b); and (3) 219 T2D-ESKD cases and 908 non-diabetic, non-nephropathy controls from WFSM genotyped on MEGA (stage 1c). A meta-analysis (stage 2) was performed to combine association results for 3432 T2D-ESKD cases and 6977 non-diabetic, non-nephropathy controls from stages 1a, 1b, and 1c. An inflation factor λ of 1.013 was observed after correcting for genomic control (Additional file 1: Figure S1), suggesting that population structure and cryptic relatedness were sufficiently adjusted. Among variants demonstrating suggestive associations (P < 1 × 10−5), 59 variants with _I_2 ≥ 80% were excluded due to high heterogeneity in effect sizes across studies. A total of 478 remaining variants were assessed in a discrimination analysis (81 of them achieved genome-wide significance; Additional file 1: Table S2).

Stage 3 discrimination analysis

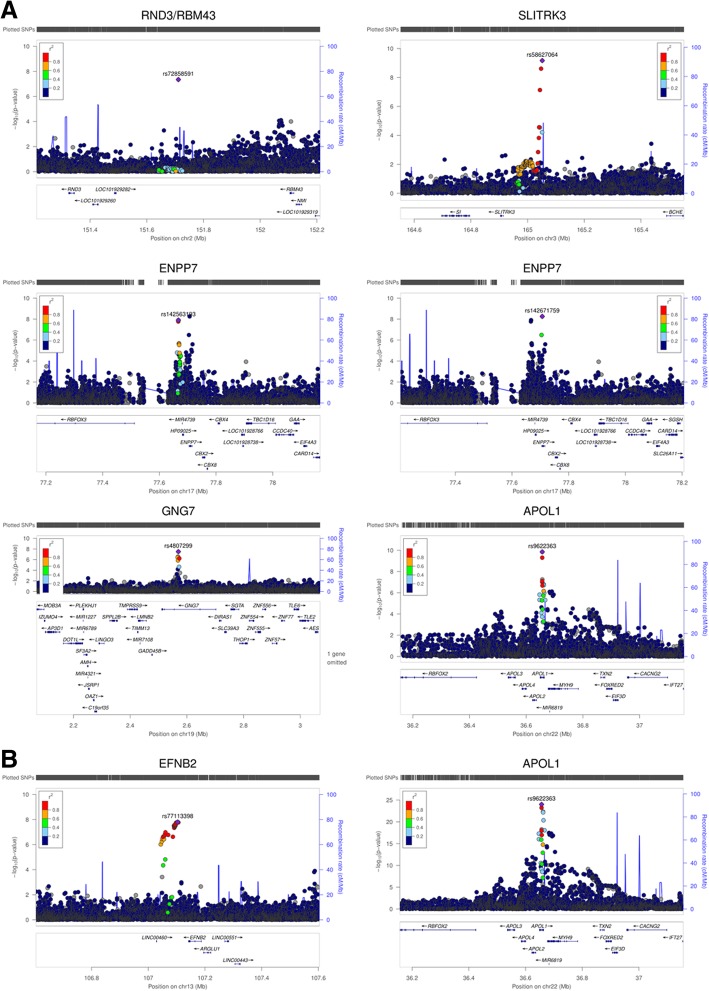

To determine whether the T2D-ESKD associations identified in stage 1 meta-analysis were driven by association with T2D per se, a discrimination analysis was performed for T2D contrasting 2756 AAs with T2D-lacking nephropathy with 6977 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls from stage 1 (Affy6.0, Axiom, MEGA; Additional file 1: Table S3). We subsequently excluded 174 of 478 T2D-ESKD-associated variants nominally associated with T2D in the absence of nephropathy. Among the remaining T2D-ESKD associations, top variants representing 6 independent associations achieved genome-wide significance (Table 3, Fig. 2a). The strongest association was observed for rs9622363 located at APOL1 (P = 1.42 × 10−10, OR = 0.77, EAF = 0.45). This variant was in moderate linkage disequilibrium (_r_2 = 0.33 and 0.34, respectively in YRI) with the APOL1 G1 alleles (rs60910145, rs73885319) associated with non-diabetic ESKD [6]. The second strongest association was at rs58627064, an intergenic variant located near SLITRK3, (P = 6.81 × 10−10, OR = 1.62, EAF = 0.06). Two independent signals, rs142563193 (P = 1.24 × 10−8, OR = 0.74, EAF = 0.23) and rs142671759 (P = 5.53 × 10−9, OR = 2.26, EAF = 0.02) on chromosome 17 located near ENPP7, respectively, were also genome-wide significant. In addition, two associations with T2D-ESKD, rs4807299 (P = 3.21 × 10−8, OR = 1.67, EAF = 0.05) located in GNG7 and rs72858591 (P = 4.54 × 10−8, OR = 1.43, EAF = 0.10) located in RND3/RBM43 were identified (Fig. 1a).

Table 3.

Genome-wide significant T2D-ESKD associations (P < 5 × 10−8) in baseline model

| Lead variant | CHR | POS | Locus | Effect/other alleles | Stage 1a (1513 T2D-ESKD cases vs. 5299 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | Stage 1b (1700 T2D-ESKD cases vs. 770 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | Stage 1c (219 T2D-ESKD cases vs. 908 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | Stage 2: Meta-analysis (3432 T2D-ESKD cases vs. 6977 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | Info | EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | Info | EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | Info | EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | HetP | |||||

| rs72858591 | 2 | 151711452 | RND3/RBM43 | C/T | 0.10 | 1.55 (1.33,1.8) | 1.32E−08 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 1.19 (0.92,1.54) | 0.18 | 0.98 | 0.10 | 1.14 (0.72,1.82) | 0.57 | 0.97 | 0.10 | 1.43 (1.26,1.62) | 4.54E−08 | 0.15 |

| rs58627064 | 3 | 165051826 | SLITRK3 | T/G | 0.07 | 1.84 (1.53,2.2) | 4.38E−11 | 0.91 | 0.06 | 1.19 (0.87,1.64) | 0.27 | 0.97 | 0.06 | 1.25 (0.7,2.23) | 0.46 | 1.00 | 0.06 | 1.62 (1.39,1.89) | 6.81E−10 | 0.045 |

| rs142563193 | 17 | 77667171 | ENPP7 | A/G | 0.22 | 0.69 (0.6,0.78) | 3.27E−08 | 0.64 | 0.23 | 0.81 (0.68,0.96) | 0.018 | 0.97 | 0.25 | 0.91 (0.66,1.26) | 0.57 | 0.97 | 0.23 | 0.74 (0.67,0.82) | 1.24E−08 | 0.15 |

| rs142671759 | 17 | 77706698 | ENPP7 | C/T | 0.03 | 2.82 (2.05,3.87) | 1.53E−10 | 0.73 | 0.02 | 1.15 (0.62,2.12) | 0.66 | 0.82 | 0.02 | 1.53 (0.57,4.13) | 0.40 | 0.92 | 0.02 | 2.26 (1.72,2.97) | 5.53E−09 | 0.029 |

| rs4807299 | 19 | 2570002 | GNG7 | A/C | 0.05 | 1.95 (1.58,2.41) | 7.31E−10 | 0.79 | 0.04 | 1.12 (0.76,1.65) | 0.56 | 0.88 | 0.05 | 1.16 (0.58,2.32) | 0.68 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 1.67 (1.4,2) | 3.21E−08 | 0.028 |

| rs9622363 | 22 | 36656555 | APOL1 | A/G | 0.46 | 0.78 (0.7,0.85) | 2.55E−07 | 0.87 | 0.44 | 0.77 (0.66,0.89) | 0.00040 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.77 (0.58,1.03) | 0.08 | 0.97 | 0.45 | 0.77 (0.72,0.84) | 1.42E−10 | 0.995 |

Fig. 2.

Locus plots of genome-wide associations in the baseline model. a Locus plots of T2D-ESKD associations at P < 5 × 10−8 in the baseline model. b Locus plots of all-cause ESKD-associated variants at P < 5 × 10− 8 in the baseline model. Abbreviations: T2D, type 2 diabetes; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; Baseline model: adjusted for age, sex, and PC1. APOL1 risk genotype carriers were included; reference genome: hg19/1000 Genomes Nov 2014 AFR.

Stage 4 non-diabetic ESKD analysis and stage 5 all-cause ESKD meta-analysis

After the discrimination stage, 304 variants exhibiting suggestive association with T2D-ESKD (P < 1 × 10−5) were tested in 1910 independent non-diabetic ESKD cases and 908 controls from stage 1c. The goal of the stage 4 analysis was to evaluate the contribution of T2D-ESKD-associated loci to non-diabetic kidney disease. After excluding variants with heterogeneity _I_2 ≥ 80%, 25 variants were nominally associated with non-diabetic ESKD (P < 0.05). Strong associations (1.27 × 10−29 < P < 8.86 × 10−15) were observed in the APOL1-MYH9 region, confirming their role in non-diabetic kidney disease. An all-cause ESKD meta-analysis, including 5342 all-cause ESKD and 6977 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls, was conducted to evaluate the generalizability of the 25 T2D-ESKD-associated variants with broader forms of ESKD (stage 5). Thirty-five genome-wide significant variants at two loci were found to be associated with all-cause ESKD, including 15 variants within or near EFNB2 and 20 variants at APOL1 (Fig. 1b). The top association in APOL1 was rs9622363 (P = 1.96 × 10−25, OR = 0.68, EAF = 0.43), and the top signal near EFNB2 was rs77113398 (P = 9.84 × 10−9, OR = 1.94, EAF = 0.023) (Table 4, Fig. 2b). Four additional independent loci demonstrated suggestive association (P < 5 × 10−6) with all-cause ESKD at LPP, FSTL5, OPRK1/ATPV1H, and SYBU/KCNV1 (Table 4, Fig. 2b).

Table 4.

All-cause ESKD-associated variants at P < 5 × 10–6 in baseline model

| Lead variant | CHR | POS | Locus | Effect/other alleles | Info | Stage 2 (3432 T2D-ESKD cases vs. 6977 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | Stage 4 (1910 non-diabetic ESKD cases vs. 908 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | Stage 5: Meta-analysis (5342 all-cause ESKD cases vs. 6977 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | HetP | ||||||

| rs76971802 | 3 | 188607071 | LPP | T/C | 0.95 | 0.087 | 1.35 (1.19,1.54) | 8.66E−06 | 0.084 | 1.42 (1.08,1.87) | 0.013 | 0.087 | 1.35 (1.2,1.52) | 1.36E−06 | 0.86 |

| rs5863506 | 4 | 162909217 | FSTL5 | TA/T | 0.96 | 0.33 | 1.22 (1.12,1.32) | 1.64E−06 | 0.33 | 1.19 (1.01,1.40) | 0.033 | 0.33 | 1.21 (1.12,1.30) | 4.57E−07 | 0.87 |

| rs141746998 | 8 | 54310938 | OPRK1/ATP6V1H | CAT/C | 0.94 | 0.031 | 0.62 (0.5,0.76) | 9.40E−06 | 0.034 | 0.61 (0.39,0.93) | 0.022 | 0.031 | 0.61 (0.5,0.75) | 1.44E−06 | 0.96 |

| rs11997465 | 8 | 110891977 | SYBU/KCNV1 | C/G | 0.99 | 0.28 | 1.22 (1.12,1.33) | 3.21E−06 | 0.28 | 1.21 (1.02,1.43) | 0.026 | 0.28 | 1.22 (1.13,1.31) | 6.72E−07 | 0.65 |

| rs77113398 | 13 | 107103906 | EFNB2 | A/G | 0.93 | 0.023 | 1.94 (1.52,2.47) | 1.25E−07 | 0.021 | 1.87 (1.08,3.24) | 0.025 | 0.023 | 1.94 (1.55,2.43) | 9.84E−09 | 0.96 |

| rs9622363 | 22 | 36656555 | APOL1 | A/G | 0.95 | 0.45 | 0.77 (0.72,0.84) | 1.42E−10 | 0.35 | 0.42 (0.36,0.48) | 4.32E−29 | 0.43 | 0.68 (0.64,0.73) | 1.96E−25 | 1.14E−09 |

Association analysis excluding APOL1 renal-risk-genotype carriers

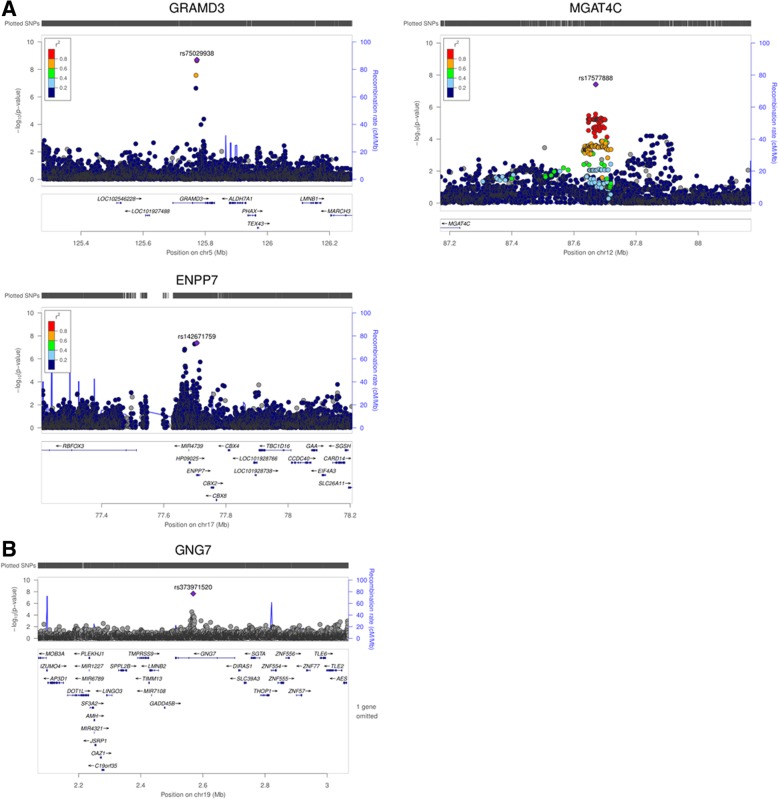

A secondary analysis was performed excluding APOL1 renal-risk-genotype carriers in T2D-ESKD cases and non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls (_APOL1_-negative model) to enrich for T2D-associated ESKD. The baseline model showed a strong association of APOL1 and MYH9 with T2D-ESKD (Table 3, Fig. 1a) suggesting that some cases may have been misclassified and more likely had non-diabetic ESKD. A total of 664 T2D-ESKD cases and 918 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls were excluded from stage 1 analysis, leaving 2768 T2D-ESKD cases and 6059 controls in the _APOL1_-negative model. Nominal associations with T2D-ESKD (P < 1 × 10−5) were observed with 522 variants (66 of them achieved genome-wide significance; Additional file 1: Table S2), and these were selected for stage 3 discrimination analysis. Two hundred twenty-three variants that had evidence of association with T2D per se (Additional file 1: Table S4) and 24 variants showing strong heterogeneity (_I_2 ≥ 80) in the meta-analysis were removed. Among the genome-wide significant variants identified in the baseline model, rs142671759 in ENPP7 (P = 4.10 × 10−8, OR = 2.30, EAF = 0.024) showed a consistent association with T2D-ESKD in the _APOL1_-negative model. Two additional variants reached genome-wide significance, rs75029938 in GRAMD3 (P = 2.02 × 10–9, OR = 1.89, EAF = 0.042) and rs17577888 in the MGAT4C region (P = 3.87 × 10−8, OR = 0.67, EAF = 0.087) (Table 5, Fig. 3a).

Table 5.

Genome-wide significant T2D-ESKD associations (P < 5 × 10−8) in _APOL1_-negative model

| Lead variant | CHR | POS | Locus | Annotation | Effect/other allele | Stage 1a (1205 T2D-ESKD cases vs. 4669 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | Stage 1b (1377 T2D-ESKD cases vs. 657 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | Stage 1c (186 T2D-ESKD cases vs. 733 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | Stage 2: Meta-analysis (2768 T2D-ESKD cases vs. 6059 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | Info | EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | Info | EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | Info | EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | HetP | ||||||

| rs75029938 | 5 | 125773333 | GRAMD3 | Intron | T/C | 0.044 | 2.27 (1.78,2.88) | 1.88E−11 | 0.87 | 0.036 | 1.01 (0.62,1.65) | 0.97 | 0.69 | 0.032 | 1.23 (0.51,2.96) | 0.65 | 0.94 | 0.042 | 1.89 (1.54, 2.34) | 2.02E−09 | 0.0094 |

| rs17577888 | 12 | 87670213 | MGAT4C | Intergenic | T/G | 0.089 | 0.69 (0.58,0.82) | 1.99E−05 | 1 | 0.086 | 0.59 (0.44,0.78) | 0.00029 | 0.99 | 0.073 | 0.84 (0.46,1.55) | 0.59 | 0.99 | 0.087 | 0.67 (0.58, 0.77) | 3.87E−08 | 0.50 |

| rs142671759 | 17 | 77706698 | ENPP7 | Intron | C/T | 0.025 | 2.71 (1.92,3.82) | 1.46E−08 | 0.73 | 0.019 | 1.52 (0.78,2.94) | 0.22 | 0.82 | 0.016 | 1.19 (0.39,3.7) | 0.76 | 0.92 | 0.024 | 2.29 (1.7, 3.07) | 4.1E−08 | 0.16 |

Fig. 3.

Locus plots of genome-wide associations in the _APOL1_-negative model. a Locus plots of T2D-ESKD associations at P < 5 × 10−8 in the _APOL1_-negative model. b Locus plots of all-cause ESKD associations at P < 5 × 10−8 in the _APOL1_-negative model. Abbreviations: T2D, type 2 diabetes; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; P, P value; _APOL1_-negative mode, adjusted for age, sex, and PC1. APOL1 risk genotype carriers excluded; reference genome: hg19/1000 Genomes Nov 2014 AFR.

We further tested 275 suggestive T2D-ESKD associations that passed discrimination and had _I_2 < 80 in 1019 additional AA non-diabetic ESKD cases that excluded APOL1 renal-risk-genotype carriers. Fifteen variants showed nominal evidence of association with non-diabetic ESKD. These were subsequently tested in an all-cause ESKD meta-analysis including 3787 all-cause ESKD cases and 6059 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls of which APOL1 renal-risk-genotype carriers were excluded. A 2-base pair deletion in GNG7, rs373971520 (P = 2.17 × 10−8, OR = 1.46, EAF = 0.11), achieved genome-wide significant association with all-cause ESKD (Fig. 3b). Seven additional loci displayed nominal association with all-cause ESKD (P < 5 × 10−6), including LPP, ALK/YPEL5, MNX1-AS1/UBE3C, NUP98, LINC01075/LINC00448, TMCO5A, and SULF2/LINC01522 (Table 6). The top associations from the baseline model had moderate attenuation in significance, despite the similar effect sizes, due in part to the reduced sample size (Additional file 1: Table S5).

Table 6.

All-cause ESKD-associated variants at P < 5 × 10−6 in _APOL1_-negative model

| Lead variant | CHR | POS | Locus | Effect/other allele | *Info | Stage 2: Meta-analysis (2768 T2D-ESKD cases vs. 6059 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | Stage 4 (1019 non-diabetic ESKD cases vs. 733 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | Stage 5 (3787 all-cause ESKD cases vs. 6059 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | EAF | OR(95% CI) | P | EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | HetP | ||||||

| rs12472637 | 2 | 30304514 | ALK/YPEL5 | A/G | 0.94 | 0.33 | 0.81 (0.74, 0.89) | 6.05E−06 | 0.36 | 0.8 (0.66, 0.96) | 0.019 | 0.33 | 0.82 (0.76, 0.89) | 4.47E−06 | 0.83 |

| rs76971802 | 3 | 188607071 | LPP | T/C | 0.95 | 0.09 | 1.43 (1.24, 1.65) | 1.06E−06 | 0.08 | 1.45 (1.03, 2.05) | 0.032 | 0.088 | 1.42 (1.24, 1.62) | 5.76E−07 | 0.93 |

| rs6459733 | 7 | 156930550 | MNX1-AS1/UBE3C | G/C | 0.97 | 0.39 | 1.25 (1.15, 0.87) | 1.32E−07 | 0.39 | 1.25 (1.03, 1.53) | 0.026 | 0.39 | 1.24 (1.15, 1.35) | 7.17E−08 | 0.83 |

| rs4910809 | 11 | 3813850 | NUP98 | C/G | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.53 (0.4, 0.7) | 9.46E−06 | 0.02 | 0.53 (0.29, 0.95) | 0.034 | 0.023 | 0.53 (0.41, 0.69) | 2.12E−06 | 0.63 |

| rs219020 | 13 | 63013622 | LINC01075/LINC00448 | C/T | 0.97 | 0.14 | 1.31 (1.17, 0.86) | 6.84E−06 | 0.11 | 1.38 (1.02, 1.87) | 0.037 | 0.14 | 1.31 (1.17, 1.47) | 2.12E−06 | 0.58 |

| rs113452507 | 15 | 37954309 | TMCO5A | C/G | 0.92 | 0.16 | 1.29 (1.15, 1.45) | 9.71E−06 | 0.16 | 1.38 (1.07, 1.77) | 0.014 | 0.16 | 1.31 (1.18, 1.45) | 8.48E−07 | 0.93 |

| rs373971520 | 19 | 2568805 | GNG7 | –/CA | 0.81 | 0.11 | 1.47 (1.28, 1.7) | 8.97E−08 | 0.11 | 1.39 (1.01, 1.91) | 0.044 | 0.11 | 1.46 (1.28, 1.67) | 2.17E−08 | 0.016 |

| rs6094913 | 20 | 46561443 | SULF2/LINC01522 | G/A | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.72 (0.63, 1.6) | 8.28E−06 | 0.10 | 0.67 (0.48, 0.91) | 0.012 | 0.092 | 0.72 (0.63, 0.83) | 2.5E−06 | 0.70 |

In addition, a third GWAS was performed with APOL1 included as a covariate in the model (_APOL1_-adjusted model) and comparing −log (P) values with baseline and _APOL1_-negative models. High correlation (Person correlation coefficient r = 0.95) was observed between _APOL1_-adjusted and _APOL1_-negative models. The results of all three comparisons are included in the supplementary documentation (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

Discussion

We report the results of a high-density GWAS investigating genetic susceptibility to T2D-ESKD in 15,075 AAs. Top variants associated with T2D-ESKD were subsequently assessed for association with non-diabetic ESKD, and a meta-analysis was performed to test for their generalizability to common forms of ESKD. Eight independent associations in seven genetic loci displayed genome-wide significant association with T2D-ESKD in the baseline or _APOL1_-negative models, including RND3/RBM43, SLITRK3, ENPP7, GNG7, APOL1, GRAMD3, and MGAT4C. In addition to APOL1, two genome-wide significant loci were associated with all-cause ESKD, EFNB2 and GNG7. Further, 10 genetic loci demonstrated nominal association with all-cause ESKD (P < 5 × 10−6), including LPP, FSTL5, OPRK1/ATP6V1H, SYBU/KCNV1, ALK/YPEL5, MNX1-AS1/UBE3C, NUP98, LINC01075/LINC00448, TMCO5A, and SULF2/LINC01522.

The most significant association with T2D-ESKD (OR = 0.77, P = 1.42 × 10−10) and all-cause ESKD (OR = 0.69, P = 1.96 × 10−25) in the baseline model was an intronic variant rs9622363 in the APOL1 region associated with non-diabetic kidney disease in individuals with African ancestry. Conditioning on the APOL1 G1 and G2 alleles dramatically diminishes its significance [6]. rs9622363 is reported to alter transcription factor (TF) binding motifs (Additional file 1: Table S6). In a recent study, rs9622363 and APOL1 G1 alleles formed a haplotype that achieved the strongest association with CKD in Nigerians [19]. Unlike G1 or G2, the major allele in rs9622363 (G, EAF = 0.57) is associated with the risk of CKD. After excluding APOL1 renal-risk-genotype carriers, association with rs9622363 was attenuated. This confirmed that rs9622363 and APOL1 G1 and G2 alleles contribute to the same signal. Identification of rs9622363 in the baseline model may suggest misclassification of some cases as T2D-ESKD.

An intergenic variant (rs72858591) located between a GTPase protein gene RND3 and RBM43, encoding RNA binding motif protein 43, revealed genome-wide significant association with T2D-ESKD. It is associated with TF binding motif changes and overlap with both promoter and enhancer regions (Additional file 1: Table S6). An independent intergenic variant (rs7560163, _r_2 = 0.01, YRI) in this region was previously associated with T2D in AAs [20]. In contrast, rs72858591 was not associated with T2D (P = 0.073) in the present study. This may suggest that two different sets of variations in this locus independently contribute to T2D and T2D-ESKD, a possible pleiotropic effect. Two independent variants (rs142563193 and rs142671759) that were genome-wide significantly associated with T2D-ESKD are located near ENPP7. These variants overlap with enhancer and promoter regions, DNase hypersensitive peaks, and/or TF binding motifs (Additional file 1: Table S6). The protein encoded by ENPP7 is an intestinal alkaline sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase that converts sphingomyelin to ceramide and phosphocholine. ENPP7 reportedly affects cholesterol absorption [21], and numerous studies suggest that high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels are risk factors for CKD in patients with diabetes [22–24].

Two variants located in GNG7 were associated with either T2D-ESKD (rs4807299; P = 3.21 × 10−8, baseline model) or all-cause ESKD (rs373971520; P = 2.17 × 10−8; _APOL1_-negative model). Rs4807299 is associated with TF binding motif changes and overlaps with both promoter and enhancer regions (Additional file 1: Table S6). GNG7 encodes G Protein Subunit Gamma 7, involved in central nervous system function [25] and cancer risk [26, 27].

Since African Americans with diabetes and proteinuria often do not get a diagnostic kidney biopsy, their ESKD is typically presumed to have been caused by DKD. However, _APOL1_-associated non-diabetic kidney disease may be the true cause of kidney disease in many such patients. Analyses excluding APOL1 renal-risk-genotype carriers created a more homogeneous case group and provided an opportunity to uncover the genetic architecture of T2D-ESKD that is independent of APOL1 effect. In the _APOL1_-negative model, in addition to replicating ENPP7 identified in the baseline model, two novel loci achieved genome-wide significant association with T2D-ESKD: GRAMD3 (rs75029938; P = 2.02 × 10−9) and MGAT4C (rs17577888; P = 3.87 × 10−8). Functional annotation suggested that both variants are co-located with TF binding motifs. Rs75029938 may fall into enhancer and promoter regions, and rs17577888 was associated with transcript abundance of FLVCR1 gene in peripheral blood monocytes (P = 6.41 × 10−6; Additional file 1: Table S6). Genetic variation in GRAMD3 has been associated with adiposity in a multi-ethnic genome-wide meta-analysis [28]. Previous studies suggest that obesity is a major risk factor for DKD [29]. MGAT4C encodes Mannosyl (Alpha-1,3-)-Glycoprotein Beta-1,4-_N_-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase, Isozyme C, which participates in the transfer of _N_-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) to the core mannose residues of N-linked glycans. The potential involvement of MGAT4C in DKD requires further study.

This analysis included a cohort of AAs with non-diabetic ESKD to evaluate the generalizability of T2D-ESKD-associated loci in common forms of CKD. The meta-analysis combining cases with T2D-ESKD and non-diabetic ESKD identified two novel genome-wide significant loci associated with all-cause ESKD in addition to APOL1; rs77113398 near EFNB2 (P = 9.84 × 10−9; baseline model) and rs373971520 in GNG7 (2.17 × 10−8; _APOL1_-negative model). Rs77113398 overlaps with enhancer, promoter regions, and DNase peaks (Additional file 1: Table S6). Prior genome scans in AAs identified significant evidence for linkage to ESKD on chromosome 13q33 including the EFNB2 region in both diabetic ESKD and non-diabetic ESKD [30, 31]. A follow-up study examined 28 tagging variants spanning 39 kilobases (kb) of the EFNB2 coding region demonstrated nominal associations between two variants and all-cause ESKD [32]. However, these reported variants were not correlated with rs77113398. Ephrin-B2 (EFNB2) is expressed in the developing nephron; interactions between ephrin-B2 and its receptors play an important role in glomerular microvascular assembly [33]. In addition, ephrin-B2 reverse signaling protects against peritubular capillary rarefaction by regulating angiogenesis and vascular stability during kidney injury [34]. Ephrin-B1 also co-localizes with CD2-associated protein (CD2AP) and nephrin at the podocyte slit diaphragm and plays an important role in maintaining barrier function at the slit diaphragm [35]. Ephrin B4 receptor kinase transgenic mice develop glomerulopathy, manifested by fused afferent and efferent arterioles bypassing the glomeruli [36]. Thus, multiple lines of evidence support the potential EFNB2 association with CKD, and it is the most promising causal gene underlying association of rs77113398.

This study has strengths and limitations. Although the multi-stage study design was well-powered including 15,075 AAs, it lacked replication of T2D-ESKD associations, particularly for rare variants. Furthermore, several genome-wide significant signals showed significantly different effect sizes across stages, which was likely attributable to sample size differences across stages, and a consequence of the “winner’s curse,” a phenomenon describing that the true genetic effect size is overestimated because of the initial positive finding. Future replication is needed to confirm these findings. There are few other existing collections with appropriate samples in AAs; this limited replication efforts. Moreover, it is difficult to exclude all individuals misclassified with DKD due to the frequent lack of kidney biopsies. Therefore, we carefully excluded samples with ESKD attributed to non-diabetic etiologies based on clinical phenotypes and subsequently excluded APOL1 renal-risk-genotype carriers at high risk for non-diabetic ESKD. This should minimize misclassification.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a GWAS was conducted in AAs with T2D-ESKD and seven genetic loci displayed genome-wide significant evidence of association, including in RND3/RBM43, SLITRK3, ENPP7, GNG7, APOL1, GRAMD3, and MGAT4C. Beyond APOL1, EFNB2 and GNG7 were also associated with non-diabetic ESKD and revealed genome-wide significant association with all-cause ESKD. Future investigations including genetic replication and experimental validation of these newly identified associations are required to assess their potential impacts on the biological processes leading to advanced DKD in populations with recent African ancestry.

Methods

Study participants

Study participants were recruited by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (WFSM; N = 8052), Family Investigation of Nephropathy and Diabetes (FIND; N = 926), Jackson Heart Study (JHS; N = 1912), Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC; N = 2221), Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA; N = 912), and Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA; N = 1052). Analyses were approved by local institutional review boards, and all participants provided written informed consent. Cases were considered to have T2D-ESKD, including severe DKD, when diabetes was diagnosed ≥ 5 years prior to the onset of ESKD or with diabetic retinopathy to ensure adequate T2D duration, with renal replacement therapy, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≤ 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 (CKD4), or urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥ 300 mg/g (macroalbuminuria). Participants with CKD4 or macroalbuminuria (N = 138) were included as cases given their high risk of developing ESKD. T2D was diagnosed according to American Diabetes Association criteria with a fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl, 2-h oral glucose tolerance test glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl, random glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl, use of diabetes medications, or physician-diagnosed diabetes. Cases with non-diabetic ESKD lacked diabetes (or had T2D for < 5 years) at the initiation of renal replacement therapy, and ESKD was attributed to chronic glomerular disease (e.g., focal segmental glomerulosclerosis), HIV-associated nephropathy, hypertension, or unknown cause. Patients with ESKD attributed to surgical or urologic causes, polycystic kidney disease, autoimmune disease, hepatitis, IgA nephropathy, membranous glomerulonephritis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, or monogenic kidney diseases were excluded. Non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls included participants without diabetes or kidney disease (eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and UACR < 30 mg/g). Subjects with T2D-lacking nephropathy had eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and UACR < 30 mg/g.

Sample preparation, genotyping, imputation, and quality control

The study participants were genome-wide genotyped using three different platforms: (1) 8704 samples recruited from WFSM, ARIC, CARDIA, JHS, MESA, and FIND were genotyped on the Affymetrix Genome-wide Human single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array 6.0 (Affy6.0); (2) 3133 samples recruited from WFSM were genotyped on the Affymetrix Axiom Biobank Genotyping Array (Axiom); and (3) 3238 samples recruited from WFSM were genotyped on the Illumina Multi-Ethnic Genotyping Array (MEGA). Quality control and imputation were performed separately by each genotyping platform as described below.

Variants that passed quality control (QC) were imputed to a combined haplotype reference panel including the 1000 Genomes phase 3 cosmopolitan reference panel (October 2014 version) [37] and a version of the African Genome Variation Project (AGVP) reference panel including 640 African ancestry haplotypes kindly provided by the African Partnership for Chronic Disease Research and Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute [38]. Pre-phasing was performed using SHAPEIT2 [39], and imputation was performed using IMPUTE2 [40]. Post-imputation QC was conducted to exclude variants with allele mismatch or with large frequency discrepancy (≥ 0.2) with the reference panel (0.2 × frequency in EUR + 0.8 × frequency in AFR) and imputation info score < 0.4. A subset of samples was directly genotyped for APOL1 G1 and G2 variants using Sequenom (Sequenom, San Diego, CA). The concordance was 95% with imputed genotypes.

Affy6.0 datasets

As described previously [41], 1513 T2D-ESKD cases, 5299 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls, and 1892 T2D non-nephropathy controls from WFSM, FIND, JHS, ARIC, CARDIA, and MESA cohorts were genotyped using Affy6.0 (Table 1). In each study, standard QC measures were applied to exclude variants with call rate < 95%, minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.01, or showing departure from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) (P < 0.0001). Sample QC was performed to exclude subjects with call rates < 95%, DNA contamination, duplicates, or population outliers. Given that CARDIA, JHS, and MESA lacked cases with T2D-ESKD, samples from these studies were combined for imputation and association analyses along with WFSM, FIND, and ARIC.

Axiom dataset

At WFSM, 1700 AA cases with T2D-ESKD, 770 AA controls without diabetes or nephropathy, and 663 AA controls with T2D who lacked nephropathy were genotyped on a customized Axiom genotyping array (Table 2). Detailed variant information, custom content design, including fine mapping of candidate regions, genotyping methods, and QC were previously reported [42]. In brief, this array included approximately 264K coding variants and insertions/deletions (indels), 70K loss-of-function variants, 2K pharmacogenomic variants, 23K eQTL markers, 246K multi-ethnic population-based genome-wide tag markers, and 115K custom content markers. Variants with call rates < 95%, departure from HWE (P < 0.0001), and monomorphic variants were excluded. A total of 724,530 variants were successfully called for downstream QC, imputation, and analyses. Sample QC was performed to exclude individuals with low call rate (< 95%), gender discordance, DNA contamination, duplication, or population outliers.

MEGA dataset

At WFSM, 1910 non-diabetic ESKD cases, 219 T2D-ESKD cases, 201 controls with T2D lacking nephropathy, and 908 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls were genotyped on the MEGA array (Table 2). This array was designed to improve fine-mapping and functional discovery by increasing variant coverage across multiple ethnicities. The array includes (1) backbone content containing highly informative variants for GWAS and exome analyses in ancestrally diverse populations and (2) custom content used to replicate or generalize index GWAS associations, augment GWAS tagging variants in priority regions, enhance exome content in priority regions, fine-map GWAS loci, identify functional regulatory variants, explore medically important variants, and identify novel variant loci in candidate pathways [43]. Genotyping was performed at WFSM. DNA from cases and controls were equally interleaved on 96-well plates to minimize artifactual errors during sample processing. A total of 48 samples sequenced as part of the 1000 Genomes Project [44] at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research were included in genotyping and had a concordance rate of 98.57%. Genotype calling was performed using GenomeStudio (Illumina, CA, USA). Variants with missing position, missing allele, allele mismatch, call rates < 95%, departure from HWE (_P_ < 0.0001), frequency difference > 0.2 comparing with 1000 Genome Project phase 3 reference panel, and monomorphic variants were removed. Multiple probe sets were compared, and only the one with the highest call rate was kept. A total of 1,705,970 variants were successfully called for downstream QC, imputation, and analyses. Sample QC was performed to exclude individuals with low call rate (< 95%), gender discordance, DNA contamination, duplication, or population outliers. DNA swapping was identified and corrected.

Statistical analysis

Discovery stage

We used a multi-stage study design to identify variants associated with T2D-ESKD and their potential role in all-cause ESKD. In the discovery stage, 3432 T2D-ESKD cases and 6977 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls from all three datasets were included (Fig. 1). Association analysis was performed for each dataset using a logistic mixed model method implemented in the program GMMAT [45] under an additive genetic model. This method controls for population structure and cryptic relatedness through including a genetic relationship matrix (GRM) estimated from a set of high-quality autosomal variants as a random effect. The principal component analysis was performed using EIGENSOFT [46] for each genotyping platform. The first eigenvector (PC1) along with age and sex was used as covariates. A meta-analysis was performed in the three datasets using a fixed effect inverse variance weighting method implemented in METAL [47]. Suggestive associations for T2D-ESKD with P < 1 × 10−5, minor allele count (MAC) > 400, and heterogeneity _I_2 < 80 were selected for discrimination analysis.

Discrimination stage

To determine whether putative T2D-ESKD-associated loci in the discovery stage were driven by associations with T2D per se, a meta-analysis combining 2756 AAs with T2D-lacking nephropathy and 6977 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls from the three datasets (Affy6.0, Axiom, and MEGA) was performed (stage 3, Fig. 1). Variants showing nominal association (P < 0.05) with T2D were excluded to remove T2D-associated variants.

Extension analysis of non-diabetic ESKD and meta-analysis of all-cause ESKD

Genetic variants showing suggestive association with T2D-ESKD (P < 1 × 10−5) but not associated with T2D were examined in a non-diabetic ESKD cohort including 1910 non-diabetic ESKD cases and 908 non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls from the WFSM-MEGA dataset for association with non-diabetic etiologies of kidney disease (stage 4). Variants showing nominal association (P < 0.05) were tested in a meta-analysis of all-cause ESKD using all T2D-ESKD, non-diabetic ESKD, and controls from the three datasets (N = 12,319, Affy6.0, Axiom, MEGA) (Fig. 1). This meta-analysis evaluated whether T2D-ESKD associations contributed to the risk of all-cause ESKD. We also looked up our top kidney disease-associated variants for putative association with T2D in AAs from the MEDIA consortium (N = 15,043 cases and 22,318 controls); SNPs with P < 0.05 after multiple comparison corrections were removed.

Exclusion of APOL1 risk genotype carriers

The APOL1 G1 and G2 alleles contribute to risk for non-diabetic kidney disease [6, 48]. To minimize misclassification of T2D-ESKD, a second analysis was performed excluding APOL1 two-renal-risk-variant carriers and those with missing APOL1 genotypes from T2D-ESKD cases and non-diabetic non-nephropathy controls (_APOL1_-negative model). This analysis reduced the heterogeneity of the population despite reducing sample size and having lower statistical power. Specifically, 308 T2D-ESKD cases and 630 controls from the Affy6.0 datasets, 323 T2D-ESKD cases, and 113 controls from the Axiom dataset, and 33 T2D-ESKD cases and 175 controls from the MEGA dataset were removed. In addition, we removed 891 of 1910 all-cause ESKD cases. This analysis may unmask the effects of other non-diabetic ESKD loci beyond APOL1. Individuals were considered APOL1 renal-risk-variant carriers if they carried two G1 alleles (rs60910145 G allele, rs73885319 G allele), two G2 alleles (rs143830837, 6 base pair in-frame deletion), or were compound heterozygotes (one G1 and one G2 allele) [6].

Functional characterization

Proxies of genome-wide significant T2D-ESKD-associated variants (_r_2 ≥ 0.7 in 1000 Genomes AFR population) from the baseline and _APOL1_-negative models were selected using LDlink [49]. The lead variants and proxies were then queried for functional annotations from HaploReg [50], which included chromatin state and protein binding annotation from the Roadmap Epigenomics [51] and ENCODE projects [52], sequence conservation across mammals, the effect of variants on regulatory motifs, and gene expression from eQTL studies.

Additional file

Acknowledgements

We thank all the study participants for their valuable contributions to the parent studies (ARIC, CARDIA, FIND, JHS, MESA, WFSM). We thank the contributions of investigators and staff of the parent studies for data collection, genotyping, and data analysis.

ARIC

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds

from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (contract numbers HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700004I, and HHSN268201700005I), R01HL087641, R01HL086694; National Human Genome Research Institute contract U01HG004402; and National Institutes of Health contract HHSN268200625226C. The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. Infrastructure was partly supported by Grant Number UL1RR025005, a component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

CARDIA

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201300025C & HHSN268201300026C), Northwestern University (HHSN268201300027C), University of Minnesota (HHSN268201300028C), Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201300029C), and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (HHSN268200900041C). CARDIA is also partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and an intra-agency agreement between NIA and NHLBI (AG0005). Genotyping was funded as part of the NHLBI Candidate-gene Association Resource (N01-HC-65226). This manuscript has been reviewed by CARDIA for scientific content.

FIND

This study was also supported by FIND grants U01DK57292, U01DK57329, U01DK057300, U01DK057298, U01DK057249, U01DK57295, U01DK070657, U01DK057303, U01DK070657, U01DK57304, and CHOICE study DK07024 from the NIDDK and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIDDK.

A list of the members of the FIND Research Group follows (key: *Principal Investigator; **Co-investigator; #Program Coordinator; §University of California, Davis; †University of California, Irvine; ‡Study Chair). Genetic Analysis and Data Coordinating Center, Case Western Reserve University: *S.K. Iyengar,**R.C. Elston,**K.A.B. Goddard,**J.M. Olson, S. Ialacci, # J. Fondran, A. Horvath, R. Igo Jr., G. Jun, K. Kramp, J. Molineros, S.R.E. Quade; Case Western Reserve University: *J.R. Sedor, **J. Schelling, #A. Pickens, L. Humbert, L. Getz-Fradley; Harbor-University of California Los Angeles Medical Center: *S. Adler, **E. Ipp, **†M. Pahl, **§M.F. Seldin, ** S. Snyder, **J. Tayek, #E. Hernandez, #J. LaPage, C. Garcia, J. Gonzalez, M. Aguilar; Johns Hopkins University: *M. Klag, *R. Parekh, **L. Kao, **L. Meoni, T. Whitehead, #J. Chester; NIDDK, Phoenix, AZ: *W.C. Knowler, **R.L. Hanson, **R.G. Nelson, **J. Wolford, #L. Jones, R. Juan, R. Lovelace, C. Luethe, L.M. Phillips, J. Sewemaenewa, I. Sili, B. Waseta; University of California, Los Angeles: *M.F. Saad, *S.B. Nicholas, **Y.-D.I. Chen, **X. Guo, **J. Rotter, **K. Taylor, M. Budgett, #F. Hariri; University of New Mexico, Albuquerque: *P. Zager, *V. Shah, **M. Scavini, #A. Bobelu; University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio: *H. Abboud, **N. Arar, **R. Duggirala, **B.S. Kasinath, **F. Thameem, **M. Stern; Wake-Forest University: *‡B.I. Freedman, **D.W. Bowden, **C.D. Langefeld, **S.C. Satko, **S.S. Rich, #S. Warren, S. Viverette, G. Brooks, R. Young, M. Spainhour; Laboratory of Genomic Diversity, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD: *C. Winkler, **M.W. Smith, M. Thompson, #R. Hanson, B. Kessing; Minority Recruitment Centers: Loyola University: *D.J. Leehey, #G. Barone; University of Alabama at Birmingham: *D. Thornley-Brown, #C. Jefferson; University of Chicago: *O.F. Kohn, #C.S. Brown; NIDDK program office: J.P. Briggs, P.L. Kimmel, R. Rasooly; External Advisory Committee: D. Warnock (chair), L. Cardon, R. Chakraborty, G.M. Dunston, T. Hostetter, S.J. O’Brien (ad hoc), J. Rioux, R. Spielman. We acknowledge the contributions of the Wake Forest participants and coordinators Joyce Byers, Carrie Smith, Mitzie Spainhour, Cassandra Bethea, and Sharon Warren and the contributions of FIND participants and physicians and CHOICE patients, staff, laboratory, and physicians at Dialysis Clinic Inc. and Johns Hopkins University.

JHS

The Jackson Heart Study is supported and conducted in collaboration with Jackson State University (HHSN268201300049C and HHSN268201300050C), Tougaloo College (HHSN268201300048C), and the University of Mississippi Medical Center (HHSN268201300046C and HHSN268201300047C) contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). The authors thank the participants and data collection staff of the Jackson Heart Study. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

MESA

MESA and the MESA SHARe project are conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with MESA investigators. Support for MESA is provided by contracts HHSN268201500003I, N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168, N01-HC-95169, UL1-TR-000040, UL1-TR-001079, UL1-TR-001420, UL1-TR-001881, and DK063491. Funding for SHARe genotyping was provided by NHLBI Contract N02-HL-64278. Also, supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, CTSI grant UL1TR001881, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Diabetes Research Center (DRC) grant DK063491 to the Southern California Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center. Genotyping was performed at Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA, USA) and the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT (Boston, MA, USA) using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0.

WFSM

In Wake Forest School of Medicine (WFSM), genotyping services were provided by the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR). CIDR is fully funded through a federal contract from the National Institutes of Health to The Johns Hopkins University, contract number HHSC268200782096C. The work at Wake Forest was supported by NIH grants K99 DK081350 (NDP), R01 DK066358 (DWB/MCYN), R01 DK053591 (DWB), R01 DK087914 (MCYN), U01 DK105556 (MCYN), R01 HL56266 (BIF), R01 DK070941 (BIF) and in part by the General Clinical Research Center of the Wake Forest School of Medicine grant M01 RR07122.

Funding

ARIC has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (contract numbers HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700004I and HHSN268201700005I), R01HL087641, R01HL086694; National Human Genome Research Institute contract U01HG004402; and National Institutes of Health contract HHSN268200625226C. Infrastructure was partly supported by Grant Number UL1RR025005, a component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

CARDIA is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201300025C & HHSN268201300026C), Northwestern University (HHSN268201300027C), University of Minnesota (HHSN268201300028C), Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201300029C), and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (HHSN268200900041C). CARDIA is also partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and an intra-agency agreement between NIA and NHLBI (AG0005). Genotyping was funded as part of the NHLBI Candidate-gene Association Resource (N01-HC-65226).

FIND is supported by grants U01DK57292, U01DK57329, U01DK057300, U01DK057298, U01DK057249, U01DK57295, U01DK070657, U01DK057303, U01DK070657, U01DK57304 and CHOICE study DK07024 from the NIDDK and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIDDK.

JHS is supported and conducted in collaboration with Jackson State University (HHSN268201300049C and HHSN268201300050C), Tougaloo College (HHSN268201300048C), and the University of Mississippi Medical Center (HHSN268201300046C and HHSN268201300047C) contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD).

Support for MESA is provided by contracts HHSN268201500003I, N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168, N01-HC-95169, UL1-TR-000040, UL1-TR-001079, UL1-TR-001420, UL1-TR-001881, and DK063491. Funding for SHARe genotyping was provided by NHLBI Contract N02-HL-64278. Also, supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, CTSI grant UL1TR001881, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Diabetes Research Center (DRC) grant DK063491 to the Southern California Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center.

The genotyping services of WFSM were provided by CIDR, which is fully funded through a federal contract from the National Institutes of Health to The Johns Hopkins University, contract number HHSC268200782096C. The work at Wake Forest was supported by NIH grants K99 DK081350 (NDP), R01 DK066358 (DWB/MCYN), R01 DK053591 (DWB), R01 DK087914 (MCYN), U01 DK105556 (MCYN), R01 HL56266 (BIF), R01 DK070941 (BIF) and in part by the General Clinical Research Center of the Wake Forest School of Medicine grant M01 RR07122.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

AA

African Americans

AGVP

African Genome Variation Project

APOL1

Apolipoprotein L1

ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study

CARDIA

Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults

CKD

Chronic kidney disease

DKD

Diabetic kidney disease

EA

European Americans

EAF

Effect allele frequency

eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

ESKD

End-stage kidney disease

FIND

Family Investigation of Nephropathy and Diabetes

GRM

Genetic relationship matrix

GWAS

Genome-wide association analysis

MESA

Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

OR

Odds ratio

PC

Principal component

QC

Quality control

SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

T2D

Type 2 diabetes

T2D-ESKD

Type 2 diabetes-attributed kidney disease

UACR

Urine albumin to creatinine ratio

WFSM

Wake Forest School of Medicine

Authors’ contributions

MG and MCY designed the study. MG performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. BIF, DWB, NDP, and LM helped to design the study and interpret the results. PJH performed APOL1 genotyping. LD and JX performed server administration and data management. JMK, SKD, YIC, JC, MF, NF, HK, CDL, JCM, RSP, WSP, LJR, SSR, JIR, JRS, DT, AT, JGW, and FIND Consortium performed data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Analyses were approved by local institutional review boards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Wake Forest University Health Sciences and Barry Freedman have rights to an issued US patent related to APOL1 gene testing. Dr. Freedman is a consultant for Ionis and AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals.

The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Maggie C. Y. Ng, Phone: 336-716-6310, Email: maggie.ng@vumc.org

FIND Consortium:

A. Bobelu, A. Horvath, A. Pickens, B. Kessing, B. Waseta, B. I. Freedman, B. S. Kasinath, C. Garcia, C. Jefferson, C. Luethe, C. D. Langefeld, C. S. Brown, C. Winkler, D. Thornley-Brown, D. Warnock, D. J. Leehey, D. W. Bowden, E. Hernandez, E. Ipp, F. Hariri, F. Thameem, G. Barone, G. Brooks, G. Jun, G. M. Dunston, H. Abboud, I. Sili, J. Chester, J. Fondran, J. LaPage, J. Molineros, J. Rioux, J. Rotter, J. Schelling, J. Sewemaenewa, J. Tayek, J. Gonzalez, J. M. Olson, J. P. Briggs, J. R. Sedor, J. Wolford, K. Kramp, K. Taylor, K. A. B. Goddard, L. Cardon, L. Getz-Fradley, L. Humbert, L. Jones, L. Kao, L. Meoni, L. M. Phillips, M. Aguilar, M. Budgett, M. Klag, M. Pahl, M. Spainhour, M. Stern, M. Thompson, M. F. Saad, M. F. Seldin, M. Scavini, M. W. Smith, N. Arar, O. F. Kohn, P. Zager, P. L. Kimmel, R. Chakraborty, R. Duggirala, R. Hanson, R. Igo, Jr, R. Juan, R. Lovelace, R. Parekh, R. Rasooly, R. Spielman, R. Young, R. C. Elston, R. G. Nelson, R. L. Hanson, S. Adler, S. Ialacci, S. Snyder, S. Viverette, S. Warren, S. B. Nicholas, S. C. Satko, S. J. O’Brien, S. K. Iyengar, S. S. Rich, T. Hostetter, T. Whitehead, V. Shah, W. C. Knowler, X. Guo, and Y.-D. I. Chen

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System. 2016 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2016.

- 2.de Boer IH, Rue TC, Hall YN, et al. Temporal trends in the prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2011;305:2532–2539. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spray BJ, Atassi NG, Tuttle AB, et al. Familial risk, age at onset, and cause of end-stage renal disease in white Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;5:1806–1810. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V5101806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freedman BI, Tuttle AB, Spray BJ. Familial predisposition to nephropathy in African-Americans with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:710–713. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tzur S, Rosset S, Shemer R, et al. Missense mutations in the APOL1. Hum Genet. 2010;128:345–350. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0861-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, et al. APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. JASN. 2011;22:2129–2137. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011040388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kottgen A, Pattaro C, Boger CA, et al. Multiple new loci associated with kidney function and chronic kidney disease: the CKDGen consortium. Nat Genet. 2010;42:376–384. doi: 10.1038/ng.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pattaro Cristian, Köttgen Anna, Teumer Alexander, Garnaas Maija, Böger Carsten A., Fuchsberger Christian, Olden Matthias, Chen Ming-Huei, Tin Adrienne, Taliun Daniel, Li Man, Gao Xiaoyi, Gorski Mathias, Yang Qiong, Hundertmark Claudia, Foster Meredith C., O'Seaghdha Conall M., Glazer Nicole, Isaacs Aaron, Liu Ching-Ti, Smith Albert V., O'Connell Jeffrey R., Struchalin Maksim, Tanaka Toshiko, Li Guo, Johnson Andrew D., Gierman Hinco J., Feitosa Mary, Hwang Shih-Jen, Atkinson Elizabeth J., Lohman Kurt, Cornelis Marilyn C., Johansson Åsa, Tönjes Anke, Dehghan Abbas, Chouraki Vincent, Holliday Elizabeth G., Sorice Rossella, Kutalik Zoltan, Lehtimäki Terho, Esko Tõnu, Deshmukh Harshal, Ulivi Sheila, Chu Audrey Y., Murgia Federico, Trompet Stella, Imboden Medea, Kollerits Barbara, Pistis Giorgio, Harris Tamara B., Launer Lenore J., Aspelund Thor, Eiriksdottir Gudny, Mitchell Braxton D., Boerwinkle Eric, Schmidt Helena, Cavalieri Margherita, Rao Madhumathi, Hu Frank B., Demirkan Ayse, Oostra Ben A., de Andrade Mariza, Turner Stephen T., Ding Jingzhong, Andrews Jeanette S., Freedman Barry I., Koenig Wolfgang, Illig Thomas, Döring Angela, Wichmann H.-Erich, Kolcic Ivana, Zemunik Tatijana, Boban Mladen, Minelli Cosetta, Wheeler Heather E., Igl Wilmar, Zaboli Ghazal, Wild Sarah H., Wright Alan F., Campbell Harry, Ellinghaus David, Nöthlings Ute, Jacobs Gunnar, Biffar Reiner, Endlich Karlhans, Ernst Florian, Homuth Georg, Kroemer Heyo K., Nauck Matthias, Stracke Sylvia, Völker Uwe, Völzke Henry, Kovacs Peter, Stumvoll Michael, Mägi Reedik, Hofman Albert, Uitterlinden Andre G., Rivadeneira Fernando, Aulchenko Yurii S., Polasek Ozren, Hastie Nick, Vitart Veronique, Helmer Catherine, Wang Jie Jin, Ruggiero Daniela, Bergmann Sven, Kähönen Mika, Viikari Jorma, Nikopensius Tiit, Province Michael, Ketkar Shamika, Colhoun Helen, Doney Alex, Robino Antonietta, Giulianini Franco, Krämer Bernhard K., Portas Laura, Ford Ian, Buckley Brendan M., Adam Martin, Thun Gian-Andri, Paulweber Bernhard, Haun Margot, Sala Cinzia, Metzger Marie, Mitchell Paul, Ciullo Marina, Kim Stuart K., Vollenweider Peter, Raitakari Olli, Metspalu Andres, Palmer Colin, Gasparini Paolo, Pirastu Mario, Jukema J. Wouter, Probst-Hensch Nicole M., Kronenberg Florian, Toniolo Daniela, Gudnason Vilmundur, Shuldiner Alan R., Coresh Josef, Schmidt Reinhold, Ferrucci Luigi, Siscovick David S., van Duijn Cornelia M., Borecki Ingrid, Kardia Sharon L. R., Liu Yongmei, Curhan Gary C., Rudan Igor, Gyllensten Ulf, Wilson James F., Franke Andre, Pramstaller Peter P., Rettig Rainer, Prokopenko Inga, Witteman Jacqueline C. M., Hayward Caroline, Ridker Paul, Parsa Afshin, Bochud Murielle, Heid Iris M., Goessling Wolfram, Chasman Daniel I., Kao W. H. Linda, Fox Caroline S. Genome-Wide Association and Functional Follow-Up Reveals New Loci for Kidney Function. PLoS Genetics. 2012;8(3):e1002584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pattaro C, Teumer A, Gorski M, et al. Genetic associations at 53 loci highlight cell types and biological pathways relevant for kidney function. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10023. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tin A, Colantuoni E, Boerwinkle E, et al. Using multiple measures for quantitative trait association analyses: application to estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) J Hum Genet. 2013;58:461–466. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maeda S. Genome-wide search for susceptibility gene to diabetic nephropathy by gene-based SNP. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2004;66:S45–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pezzolesi MG, Poznik GD, Mychaleckyj JC, et al. Genome-wide association scan for diabetic nephropathy susceptibility genes in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58:1403–1410. doi: 10.2337/db08-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonough CW, Palmer ND, Hicks PJ, et al. A genome wide association study for diabetic nephropathy genes in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2011;79:563–572. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandholm Niina, Salem Rany M., McKnight Amy Jayne, Brennan Eoin P., Forsblom Carol, Isakova Tamara, McKay Gareth J., Williams Winfred W., Sadlier Denise M., Mäkinen Ville-Petteri, Swan Elizabeth J., Palmer Cameron, Boright Andrew P., Ahlqvist Emma, Deshmukh Harshal A., Keller Benjamin J., Huang Huateng, Ahola Aila J., Fagerholm Emma, Gordin Daniel, Harjutsalo Valma, He Bing, Heikkilä Outi, Hietala Kustaa, Kytö Janne, Lahermo Päivi, Lehto Markku, Lithovius Raija, Österholm Anne-May, Parkkonen Maija, Pitkäniemi Janne, Rosengård-Bärlund Milla, Saraheimo Markku, Sarti Cinzia, Söderlund Jenny, Soro-Paavonen Aino, Syreeni Anna, Thorn Lena M., Tikkanen Heikki, Tolonen Nina, Tryggvason Karl, Tuomilehto Jaakko, Wadén Johan, Gill Geoffrey V., Prior Sarah, Guiducci Candace, Mirel Daniel B., Taylor Andrew, Hosseini S. Mohsen, Parving Hans-Henrik, Rossing Peter, Tarnow Lise, Ladenvall Claes, Alhenc-Gelas François, Lefebvre Pierre, Rigalleau Vincent, Roussel Ronan, Tregouet David-Alexandre, Maestroni Anna, Maestroni Silvia, Falhammar Henrik, Gu Tianwei, Möllsten Anna, Cimponeriu Danut, Ioana Mihai, Mota Maria, Mota Eugen, Serafinceanu Cristian, Stavarachi Monica, Hanson Robert L., Nelson Robert G., Kretzler Matthias, Colhoun Helen M., Panduru Nicolae Mircea, Gu Harvest F., Brismar Kerstin, Zerbini Gianpaolo, Hadjadj Samy, Marre Michel, Groop Leif, Lajer Maria, Bull Shelley B., Waggott Daryl, Paterson Andrew D., Savage David A., Bain Stephen C., Martin Finian, Hirschhorn Joel N., Godson Catherine, Florez Jose C., Groop Per-Henrik, Maxwell Alexander P. New Susceptibility Loci Associated with Kidney Disease in Type 1 Diabetes. PLoS Genetics. 2012;8(9):e1002921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandholm N, Zuydam NV, Ahlqvist E, et al. The genetic landscape of renal complications in type 1 diabetes. JASN. 2017;28:557–574. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016020231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iyengar SK, Sedor JR, Freedman BI, et al. Genome-wide association and trans-ethnic meta-analysis for advanced diabetic kidney disease: Family Investigation of Nephropathy and Diabetes (FIND) PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahajan A, Rodan AR, Le TH, et al. Trans-ethnic fine mapping highlights kidney-function genes linked to salt sensitivity. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:636–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tayo BO, Kramer H, Salako BL, et al. Genetic variation in APOL1 and MYH9 genes is associated with chronic kidney disease among Nigerians. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45:485–494. doi: 10.1007/s11255-012-0263-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer ND, McDonough CW, Hicks PJ, et al. A genome-wide association search for type 2 diabetes genes in African Americans. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang P, Chen Y, Cheng Y, et al. Alkaline sphingomyelinase (NPP7) promotes cholesterol absorption by affecting sphingomyelin levels in the gut: a study with NPP7 knockout mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;306:G903–G908. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00319.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang Y-H, Chang D-M, Lin K-C, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and the risk of nephropathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:751–757. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams Ashley N., Conway Baqiyyah N. Effect of high density lipoprotein cholesterol on the relationship of serum iron and hemoglobin with kidney function in diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2017;31(6):958–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceriello Antonio, De Cosmo Salvatore, Rossi Maria Chiara, Lucisano Giuseppe, Genovese Stefano, Pontremoli Roberto, Fioretto Paola, Giorda Carlo, Pacilli Antonio, Viazzi Francesca, Russo Giuseppina, Nicolucci Antonio. Variability in HbA1c, blood pressure, lipid parameters and serum uric acid, and risk of development of chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2017;19(11):1570–1578. doi: 10.1111/dom.12976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwindinger WF, Betz KS, Giger KE, et al. Loss of G protein gamma 7 alters behavior and reduces striatal alpha(olf) level and cAMP production. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6575–6579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211132200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohta M, Mimori K, Fukuyoshi Y, et al. Clinical significance of the reduced expression of G protein gamma 7 (GNG7) in oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:410–417. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demokan S, Chuang AY, Chang X, et al. Identification of guanine nucleotide-binding protein γ-7 as an epigenetically silenced gene in head and neck cancer by gene expression profiling. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:1427–1436. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu AY, Deng X, Fisher VA, et al. Multiethnic genome-wide meta-analysis of ectopic fat depots identifies loci associated with adipocyte development and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2017;49:125–130. doi: 10.1038/ng.3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zoppini G, Targher G, Chonchol M, et al. Predictors of estimated GFR decline in patients with type 2 diabetes and preserved kidney function. CJASN. 2012;7:401–408. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07650711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowden DW, Colicigno CJ, Langefeld CD, et al. A genome scan for diabetic nephropathy in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1517–1526. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Rich SS, et al. A genome scan for all-cause end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:712–718. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hicks PJ, Staten JL, Palmer ND, et al. Association analysis of the ephrin-B2 gene in African-Americans with end-stage renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:914–920. doi: 10.1159/000141934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi T, Takahashi K, Gerety S, et al. Temporally compartmentalized expression of ephrin-B2 during renal glomerular development. JASN. 2001;12:2673–2682. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12122673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kida Y, Ieronimakis N, Schrimpf C, et al. EphrinB2 reverse signaling protects against capillary rarefaction and fibrosis after kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:559–572. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012080871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hashimoto T, Karasawa T, Saito A, et al. Ephrin-B1 localizes at the slit diaphragm of the glomerular podocyte. Kidney Int. 2007;72:954–964. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andres A-C, Munarini N, Djonov V, et al. EphB4 receptor tyrosine kinase transgenic mice develop glomerulopathies reminiscent of aglomerular vascular shunts. Mech Dev. 2003;120:511–516. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.1000 Genomes Project Consortium A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurdasani D, Carstensen T, Tekola-Ayele F, et al. The African genome variation project shapes medical genetics in Africa. Nature. 2015;517:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nature13997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delaneau O, Marchini J, Zagury J-F. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat Methods. 2011;9:179–181. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, et al. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ng MCY, Saxena R, Li J, et al. Transferability and fine mapping of type 2 diabetes loci in African Americans: the Candidate Gene Association Resource Plus Study. Diabetes. 2013;62:965–976. doi: 10.2337/db12-0266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guan M, Ma J, Keaton JM, et al. Association of kidney structure-related gene variants with type 2 diabetes-attributed end-stage kidney disease in African Americans. Hum Genet. 2016;135:1251–1262. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1714-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bien SA, Wojcik GL, Zubair N, et al. Strategies for enriching variant coverage in candidate disease loci on a multiethnic genotyping array. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.1000 Genomes Project Consortium A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen H, Wang C, Conomos MP, et al. Control for population structure and relatedness for binary traits in genetic association studies via logistic mixed models. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:653–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. Population structure and Eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Lu L, et al. Differential effects of MYH9 and APOL1 risk variants on FRMD3 association with diabetic ESRD in African Americans. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Machiela MJ, Chanock SJ. LDlink: a web-based application for exploring population-specific haplotype structure and linking correlated alleles of possible functional variants. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3555–3557. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D930–D934. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium Kundaje a, Meuleman W, et al. integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518:317–330. doi: 10.1038/nature14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.The ENCODE Project Consortium An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.