Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome in adults (original) (raw)

Notes

Editorial note

This 2008 review predates the mandatory use of GRADE methodology to assess the strength of evidence, and the review is no longer current. It should not be used for clinical decision‐making. The author team is no longer available to maintain the review.

Abstract

Background

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a common, debilitating and serious health problem. Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) may help to alleviate the symptoms of CFS.

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness and acceptability of CBT for CFS, alone and in combination with other interventions, compared with usual care and other interventions.

Search methods

CCDANCTR‐Studies and CCDANCTR‐References were searched on 28/3/2008. We conducted supplementary searches of other bibliographic databases. We searched reference lists of retrieved articles and contacted trial authors and experts in the field for information on ongoing/completed trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials involving adults with a primary diagnosis of CFS, assigned to a CBT condition compared with usual care or another intervention, alone or in combination.

Data collection and analysis

Data on patients, interventions and outcomes were extracted by two review authors independently, and risk of bias was assessed for each study. The primary outcome was reduction in fatigue severity, based on a continuous measure of symptom reduction, using the standardised mean difference (SMD), or a dichotomous measure of clinical response, using odds ratios (OR), with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

Fifteen studies (1043 CFS participants) were included in the review. When comparing CBT with usual care (six studies, 373 participants), the difference in fatigue mean scores at post‐treatment was highly significant in favour of CBT (SMD ‐0.39, 95% CI ‐0.60 to ‐0.19), with 40% of CBT participants (four studies, 371 participants) showing clinical response in contrast with 26% in usual care (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.76). Findings at follow‐up were inconsistent. For CBT versus other psychological therapies, comprising relaxation, counselling and education/support (four studies, 313 participants), the difference in fatigue mean scores at post‐treatment favoured CBT (SMD ‐0.43, 95% CI ‐0.65 to ‐0.20). Findings at follow‐up were heterogeneous and inconsistent. Only two studies compared CBT against other interventions and one study compared CBT in combination with other interventions against usual care.

Authors' conclusions

CBT is effective in reducing the symptoms of fatigue at post‐treatment compared with usual care, and may be more effective in reducing fatigue symptoms compared with other psychological therapies. The evidence base at follow‐up is limited to a small group of studies with inconsistent findings. There is a lack of evidence on the comparative effectiveness of CBT alone or in combination with other treatments, and further studies are required to inform the development of effective treatment programmes for people with CFS.

Plain language summary

Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a very common and disabling condition, in which people suffer from persistent symptoms of fatigue that are unexplained. Cognitive behaviour therapy is a psychological therapy model that is commonly used to treat a range of psychological and chronic pain conditions. This review aimed to find out whether CBT is effective for CBT, both as a standalone treatment and in combination with other treatments, and whether it is more effective than other treatments used for CFS. The review included 15 studies, with a total of 1043 CFS participants. The review showed that people attending for CBT were more likely to have reduced fatigue symptoms at the end of treatment than people who received usual care or were on a waiting list for therapy, with 40% of people in the CBT group showing clinical improvement, in contrast with 26% in usual care. At follow‐up, 1‐7 months after treatment ended, people who had completed their course of CBT continued to have lower fatigue levels, but when including people who had dropped out of treatment, there was no difference between CBT and usual care. The review also compared CBT against other types of psychological therapy, including relaxation techniques, counselling and support/education, and found that people attending for CBT was more likely to have reduced fatigue symptoms at the end of treatment than those attending for other psychological therapies. Physical functioning, depression, anxiety and psychological distress symptoms were also more reduced when compared with other psychological therapies. However at follow‐up, the results were inconsistent and the studies did not fit well together, making it difficult to draw any conclusions. Very few studies reported on the acceptability of CBT and no studies examined side effects. Only two studies compared the effectiveness of CBT against other treatments, both exercise therapy, and just one study compared a combination of CBT and other treatments with usual care. More studies should be carried out to establish whether CBT is more helpful than other treatments for CFS, and whether CBT in combination with other treatments is more helpful than single treatment approaches.

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a condition characterised by persistent fatigue and significant associated disability, but without evident physical or psychological disorder to explain the problem. Sufferers endure fatigue which may cause considerable and persisting debility. They may also experience a lack of understanding from others, including health professionals. This may be exacerbated by normal or equivocal findings on physical examination or investigation despite the sufferer's experience of illness. It is an important health care issue, presenting major problems for both its sufferers and for health services. Whilst fatigue is so common as to be almost a normal consequence of life (Ridsdale 1989), many of the population experience fatigue which is much more severe or long‐lasting. About one in three of the UK population report substantial fatigue, and one in five report fatigue having been present for over six months (Cox 1987). Some of these sufferers have physical or psychological disorders which cause fatigue. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of people with disabling and chronic fatigue appear to have a disorder which is medically unexplained. The term CFS describes this more defined, and serious, problem, which is thought to affect up to 1% of the general population (Wessely 1995), with a reported range of 0.006% up 3% depending on the setting and criteria used (Afari 2003).

CFS has had many names in recent decades. These include Royal Free disease, Iceland disease, neurasthenia, myalgic encephalomyelitis ('ME'), and post‐viral fatigue syndrome. All these appear to describe groups of patients with a similar problem, that is, persistent medically unexplained fatigue which causes disability and distress. The term CFS has been adopted and clearly defined in order to foster research on this common problem. Opinions regarding the cause have tended to focus on either mainly physical or mainly psychological explanations. There is increasing awareness in a range of illnesses of the potential interaction of physical and psychological factors in the development and maintenance of the disorder. Such illnesses include irritable bowel syndrome, low back pain and CFS.

Many people with CFS in the community attend their general practitioners for assessment and treatment. Some attend alternative practitioners, disappointed with the results of orthodox medical practice. Others are referred to out‐patient clinics for assessment. Referral to a variety of specialist clinics, including general medicine, endocrinology, infectious diseases, neurology, and psychiatry, reflects uncertainty and, often, disagreement among doctors and sufferers about the causes of CFS. Sufferers' and professionals' struggle to understand the illness may lead to unsatisfactory patient‐professional relationships, and dissatisfied patients.

Description of the intervention

Until recently, research studies have been unable to offer neither a convincing explanation of the causes of CFS nor evidence for effective treatments. Often, sufferers have been advised to limit the demands placed upon their bodies, in order to promote recovery and prevent deterioration, which may lead to further impairment of quality of life. Treatment strategies for CFS include psychological, physical and pharmacological interventions. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been carried out to assess the effectiveness of treatments as diverse as exercise therapy (Fulcher 1997, Wearden 1998), self‐help treatment (Chalder 1997), antidepressants (Behan 1995, Vercoulen 1996, Wearden 1998) and dietary supplementation with fatty acids (Warren 1999) and folic acid (Kaslow 1989). Over the last 15 years, an increasing number of trials for CFS have focused attention on psychological therapies, including supportive 'non‐directive' interventions and treatments that draw from cognitive and behavioural approaches.

How the intervention might work

First developed in the 1960s, and later manualised as cognitive therapy (CT) (Beck 1979), cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) incorporates elements of both behavioural therapy (BT) and cognitive therapy approaches. CBT facilitates the identification of unhelpful, anxiety‐provoking thoughts, and challenges these negative automatic thoughts and dysfunctional underlying assumptions through collaborative 'hypothesis‐testing', using behavioural tasks of diary‐keeping and validity‐testing of beliefs between sessions, together with skills training within sessions.

For the treatment of CFS, CBT combines a rehabilitative approach of a graded increase in activity with a psychological approach addressing thoughts and beliefs about CFS that may impair recovery. A gradual increase in activity, negotiated and agreed with the patient, can be used as a 'behavioural experiment', in which core beliefs, such as about the link between increased activity and worsened physical symptoms, can be tested. Catastrophic interpretations of transient increases in physical symptoms can be challenged by orthodox cognitive therapy techniques, such as the 'double column technique', in which the original, anxious, unhelpful thought is written alongside new, more realistic, more helpful alternatives.

Recent developments in CBT include 'third wave' approaches, including mindfulness‐based therapy (Kabat‐Zinn 1991; Segal 2002), compassion‐focused therapy (Gilbert 2005) and acceptance and commitment therapy (Hayes 2003). Originally focusing on the treatment of depression (Segal 2002), and now being used with a number of other disorders, including CFS, mindfulness training incorporates meditation techniques and teaches participants to observe thoughts, emotions and sensations without trying to escape, avoid or change them (Kabat‐Zinn 1991).

Why it is important to do this review

The current body of evidence for CBT remains limited to narrative synthesis within generic CFS reviews (NICE 2007; Chambers 2006) or to meta‐analysis of mean effect sizes (Malouff 2008). Furthermore, potential heterogeneity has been largely based on qualitative assessment and the impact of symptom severity and healthcare setting are uncertain moderators of effect (NICE 2007). An in‐depth, up‐to‐date, systematic review of CBT alone and in combination with other treatments for CFS is of key importance to inform treatment decision by patients, clinicians and policy‐makers. This review is central in a programme of Cochrane reviews for CFS, which also cover exercise therapy (Edmonds 2004), pharmacological treatments (Rawson 2007) and complementary approaches, including acupuncture (Zhang 2006) and traditional Chinese herbal medicine (Adams 2007).

Objectives

1. To examine the effectiveness and acceptability of CBT for CFS compared with usual management or waiting list control 2. To examine the comparative effectiveness and acceptability of CBT for CFS against other interventions (immunological, pharmacological, other psychological therapies, exercise alone, complementary/alternative and supplements) For the purposes of the updated version of this review, a third objective has been added: 3. To examine the effectiveness and acceptability of CBT in combination with other interventions against CBT alone or against other interventions alone

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs), both published and unpublished, in any language, were included in the review.

Cluster RCTs, in which centres or therapists were randomised to intervention or control groups were included, provided that the specific aim of the study was to examine the effect of the intervention.

Types of participants

Patient characteristics and setting Trials of male and female participants over the age of 16 were included, irrespective of culture and setting

Diagnosis Trials of patients who fulfilled the following diagnostic criteria for CFS were included: 1) fatigue was the principal symptom 2) the fatigue was medically unexplained, i.e. did not appear to be adequately explained by abnormalities found on examination or investigation, by diagnosed physical disorder, or by psychiatric disorder including eating disorders, alcohol or drug misuse, psychosis, bipolar affective disorder or severe depressive illness 3) the fatigue was of sufficient severity to significantly disable or distress the patient 4) the fatigue was over six months in duration*

Trials involving several disorders were included, provided that over 90% of the patients had a primary diagnosis of CFS according to the above criteria. Trials in which less than 90% of participants had a primary diagnosis of CFS were included in the review if data limited to CFS participants were provided

* Although there are a number of differences between diagnostic criteria used for CFS (Sharpe 1991; Lloyd 1988; Fukuda 1994; Carruthers 2003), they are all consistent in specifying a duration of at least six months since onset.

Comorbidity Studies involving participants with comorbid physical or common mental disorders were eligible for inclusion, as long as the comorbidity was secondary to the diagnosis of CFS. However, studies involving patients with a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis of substance‐related disorder, schizophrenia or psychotic disorder were excluded.

Types of interventions

Intervention Trials of experimental interventions which met the following criteria were included: 1) The psychological treatment(s) of interest incorporated attempted modification of thoughts and beliefs about symptoms and illness and attempted modification of behavioural responses to symptoms and illness, such as rest, sleep and activity. 2) The intervention was clearly described and was supported by appropriate references 3) No restrictions were imposed on the length of treatment, in terms of duration or number of sessions, or time between sessions 4) Both individual and group treatment modalities were eligible for inclusion

In the original version of the review, the way in which modification of thoughts, beliefs, rest, and activity was attempted was used to delineate two 'types' of CBT. 'Type A' attempted to increase activity and reduce rest time in a systematic manner, independent of symptoms, towards 'normal' levels. 'Type B' attempted to tailor the patient's rest and activity towards levels which were compatible with the limitations imposed by the disorder. Therefore, Type B CBT did not explicitly attempt to increase the patient's physical or psychological capacity beyond improving their ability to 'cope' with their disabilities.

For the purposes of updating the review, following discussion between the review authors, it was agreed that distinguishing between the two types of CBT described above was not feasible. This approach to categorising studies was therefore not adopted. Instead, interventions were categorised according to their theoretical underpinning, as follows: 1) Traditional CBT models, including cognitive behavioural approaches drawing from Beckian principles (Beck 1979). 2) Recently developed CBT models, including mindfulness training (Kabat‐Zinn 1991), compassion‐focused therapy (Gilbert 2005) and acceptance and commitment therapy (Hayes 2003).

Control conditions The following control interventions were included: 1) Minimal or usual medical management (also sometimes described in trials as standard care, treatment as usual or waiting list), to be defined here as being elements of clinic attendance, investigation, reassurance, and simple advice, without explicit psychological therapy, and also including naturalistic prescribing of medication and/or other interventions 2) Immunological therapy, to include immunoglobulin, staphylococcus toxoid and interferon 3) Pharmacotherapy, to include hydrocortisone preparations and antidepressants (all classes) 4) Non‐CBT psychological therapies, to include non‐directive (supportive) therapies, behavioural relaxation training and psychodynamic therapy 5) Exercise as a stand‐alone intervention 6) Complementary/alternative therapies, to include homeopathy, acupuncture, massage 7) Supplements, to include general supplements, essential fatty acids and other mineral and vitamin based preparations

Combination therapy For the purposes of the updated review, CBT in combination with other interventions was investigated, with therapies combined with CBT categorised as immunological, pharmacological, complementary/alternative and supplements. Exercise in the form of graded exercise or paced activity, was assumed to be an integral component of CBT.

Main comparisons For the purposes of the updated review, the following main comparisons were planned: 1. CBT versus usual care (to include treatment as usual and waiting list) 2. CBT versus immunological therapies 3. CBT versus pharmacological therapies 4. CBT versus other psychological therapies 5. CBT versus exercise 6. CBT versus complementary/alternative therapies 7. CBT versus nutritional supplements 8. CBT + other interventions (see control condition categories) versus usual care 9. CBT + other interventions versus CBT alone 10. CBT + other interventions versus other interventions alone

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The principal outcome used in this review was fatigue, measured as follows: 1) Reduction in fatigue severity (continuous), measured using the Chalder Fatigue Scale (Chalder 1993), a 14 item self‐rated scale measuring physical and mental fatigue, sometimes shortened to 11 items, or any other validated fatigue scale. 2) Clinical recovery or improvement (dichotomous), based on diagnostic interview or defined cut‐off on validated scales, as specified by trial authors.

Secondary outcomes

- Improvement in overall physical functioning, measured using rating scales, either patient‐rated such as the Physical Function dimension of the Short Form‐36 (Ware 1993), or clinician‐rated, such as the Karnofsky index (Karnofsky 1948). Other possible measures included timed walking tests and tests of strength or aerobic capacity 2) Depression symptoms, using measures such as Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) (Hamilton 1960), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1987) or Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond 1983) 3) Anxiety symptoms, using measures such as State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger 1983) or Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck 1988) 4) General psychological distress, using measures such as Symptom Checklist‐90 (SCL‐90) or General Health Questionnaire 5) Quality of life, using instruments such as Short Form 36 (SF‐36) (Ware 1993) 6) Acceptability of treatment, measured through: a) self‐rated acceptability/satisfaction scales b) dropout rates from trials due to adverse effects or ineffectiveness 7) Adverse effects: proportion of participants experiencing one or more adverse effects of treatment ( adverse effects being defined as those that are behavioural in basis e.g. self‐harm, substance misuse, suicidal attempts/suicide, violence to others) 8) Overall dropout rates from trials 9) Occupational outcomes, including employment status and work absence 10)Health service resource use e.g. primary care consultation rate, secondary care referral rate, use of alternative practitioners

Outcomes were classified as post treatment, short term follow‐up (I ‐6 months post‐treatment), medium term follow‐up (7‐12 months post‐treatment) and long term (longer than 12 months).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

- The Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Cochrane Review Group Trials Registers were searched during December 2006, with an updating search carried out in March 2008.

CCDANCTR‐Studies was searched on 28/3/2008 using the terms

Diagnosis = chronic fatigue syndrome

and

Intervention = *therap*'.

CCDANCTR‐References was searched on 28/3/2008 using the terms

Full‐text = fatigue or CFS

- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Issue 4, 2006) was searched using the search terms (chronic and fatigue and syndrome or CFS or myalgic encephalomyelitis) within title, abstract or keywords. 3) Index to Theses of Great Britain and Ireland (from 1716 to 14 December 2006) was searched at www.theses.com using advanced search (stemming on, fuzziness level 4) as follows: (chronic AND fatigue AND syndrome) OR (myalgic AND encephalomyelitis). 4) We searched during January 2007 for ongoing studies at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (free text search for 'chronic fatigue' or 'myalgic encephalomyelitis'), and http://www.controlled‐trials.com (all registers in the meta‐register of controlled trials, (chronic and fatigue and syndrome) or cfs, or myalgic and encephalomyelitis.

Searching other resources

1) Citation checking Citation lists of potentially relevant papers obtained by these methods were searched for further relevant trials, as were the reference lists of those further relevant trials. In addition, the citation lists of relevant and recent systematic reviews were perused (NICE 2007; Chambers 2006; Cho 2005; Clark 2005; Rimes 2005; Carruthers 2003; CFS/ME WG 2002; RACPWG 2002; Mulrow 2001).

2) Personal contact Known specialists in the field and principal authors of those studies, identified by the above methods, were contacted and asked to provide details of additional trials, published or unpublished, of which they were aware.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JP and EM or VH) independently decided whether each potential trial fulfilled inclusion criteria. Review authors were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions, journal of publication, and results, when they applied the inclusion criteria. Any disagreement on the eligibility of a study was discussed with the third review author, the decisions documented and, where necessary, the authors of the studies were contacted for further information.

Data extraction and management

Full data extraction, using a standardised data extraction sheet, was performed by two review authors independently (EM and ET) on studies selected for inclusion in the review. Information was collected regarding the characteristics of participants, characteristics of interventions (including 'type' of CBT), characteristics of outcome measures, and results. Data on the number with each outcome event was sought by allocated treatment group, irrespective of compliance and whether or not the patient was deemed ineligible or otherwise excluded from treatment or follow‐up, in order to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis. If any of this information was not available in the published trial, it was sought by correspondence with the trial authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Methodological quality in the context of a systematic review of treatment trials means the extent to which design is likely to have reduced the impact of bias on the results. For the purposes of the updated version of the review, methodological quality was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias. The following domains of risk of bias were used: 1) Sequence generation: Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? 2) Allocation concealment: Was allocation adequately concealed? 3) Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors for each main outcome or class of outcomes: Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study? 4) Incomplete outcome data for each main outcome or class of outcomes: Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? 5) Selective outcome reporting: Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? 6) Other sources of bias: Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

Trials were allocated to three categories within and across studies as follows: 1. Low risk of bias 2. Unclear risk of bias 3. High risk of bias.

During this procedure, review authors (EM and VH) worked independently of each other. The review authors were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions, journal of publication and results of the trials. The review authors compared their results, and any disagreements were resolved by discussion. In the event of disagreement, a third review author (JP) was consulted, the decisions documented, and where necessary, the authors of the studies were contacted for further information.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous outcomes: where studies used the same outcome measure for a comparison, data were pooled by calculating the weighted mean difference (WMD). Where different measures were used to assess the same outcome for a comparison, data were pooled by calculating the standardised mean difference (SMD), using 95% confidence intervals.

Dichotomous outcomes: dichotomous outcomes were analysed by calculating an odds ratio (OR) for each comparison, with the uncertainty in each result expressed using 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For studies where the number of participants showing clinical response were not presented in the original articles, but means and standard deviations were reported for continuous symptomatology scales, the number of responders was calculated and imputed from continuous data using a validated statistical method (Furukawa 2005). When overall results were significant, the number needed to treat (NNT) to produce one outcome was calculated by combining the overall relative risk with an estimate of the prevalence of the event in the control group of the trials.

Unit of analysis issues

Where studies had two or more active treatment arms to be compared against TAU, data were managed as follows: Continuous data ‐ means, SDs and number of participants for each active treatment group were pooled across treatment arms as a function of the number of participants in each arm (Law 2003) to be compared against the control group. As an alternative strategy, the active comparison considered to be of greatest relevance was selected (e.g. CBT was selected in preference to CT or BT arms). Dichotomous data ‐ active treatment groups were collapsed into a single arm for comparison against the control group, or the control group was split equally into two.

Dealing with missing data

Missing dichotomous data were managed through intention to treat (ITT) analysis, in which it was assumed that patients who dropped out after randomisation had a negative outcome. Best/worse case scenarios were also calculated for the clinical response outcome, in which it was assumed that dropouts in the active treatment group had positive outcomes and those in the control group had negative outcomes (best case scenario), and that dropouts in the active treatment group had negative outcomes and those in the control group had positive outcomes (worst case scenario), thus providing boundaries for the observed treatment effect.

Missing continuous data were either analysed on an endpoint basis, including only participants with a final assessment, or analysed using last observation carried forward to the final assessment (LOCF) if LOCF data were reported by the trial authors. Where SDs were missing, attempts were made to obtain these data through contacting trial authors. Where SDs were not available from trial authors, they were calculated from t‐values, confidence intervals or standard errors, where reported in articles (Deeks 1997). If these additional figures were not available or obtainable, the study data were not included in the comparison of interest.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity was formally tested using the natural approximate chi‐square test, which provides evidence of variation in effect estimates beyond that of chance. Since the chi‐squared test has low power to assess heterogeneity where a small number of participants or trials are included, the p‐value was conservatively set at 0.1. Heterogeneity was also tested using the I2 statistic, which calculates the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance, with I2 values over 50% indicating strong heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

Where sufficient numbers of trials allowed a meaningful presentation, funnel plots were constructed to establish the potential influence of publication bias.

Data synthesis

A fixed effect model was used in the first instance to combine data. Where there was evidence of statistical heterogeneity, results were recalculated using a random effects model, in order to obtain a more conservative estimate.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Clinical characteristics were examined in subgroup analyses to compare their influence on the size of the treatment effect. Where sufficient studies were available for inclusion, subgroup analyses were performed for: 1) Type of control condition (minimal management/standard care vs waiting list) 2) Modality of treatment (individual therapy vs group therapy) 3) Therapy process (face‐to‐face contact versus self‐help) 4) Therapist experience/qualifications (delivered by trained therapists vs trainee therapists) 5) Increased activity introduced as component of intervention versus tailoring activity/rest to fit current limitations or not specified 6) Number of CBT sessions (up to and including 8 sessions vs more than 8 sessions) 7) Severity/chronicity of CFS symptomatology at baseline 8) Setting (clinic‐based versus home‐based) These subgroup analyses were also used to examine potential sources of clinical heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

Where sufficient studies were available for inclusion, sensitivity analyses were planned to test the robustness of the findings obtained by removing studies based on the following internal validity criteria: 1) Inadequate allocation concealment 2) Use of less stringent diagnostic inclusion criteria, such as those set out by Lloyd 1988. 3) Dropout rate higher than 20% 4) Lack of formal testing of fidelity to psychological therapy manual These sensitivity analyses were also used to examine potential sources of methodological heterogeneity.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

An updating search of CCDANCTR‐Studies and CCDANCTR‐References was performed in March 2008. Of 14 studies identified through the search of CCDANCTR‐Studies, seven were selected for inclusion in the review. Three of the studies had been included in the original review (Deale 1996; Lloyd 1993; Sharpe 1993) and a further four studies were included in the updated review (King 1999; O'Dowd 2000; Prins 2001; Jason 2007). The search of CCDANCTR‐References identified an additional two studies for inclusion (Huibers 2004; Strang 2002).

A further 20 full articles on potentially eligible studies, including two unpublished papers and a PhD thesis, were obtained through supplementary searches and personal communication with experts in the field. Of those studies, six were selected for inclusion in the review (Barrett 1992; Ridsdale 2004; Russell 2001; Strang 2002; Whitehead 2002; Stevens 1999). Two studies (Chalder 1997; Powell 2001) are currently awaiting assessment. Futher details are provided below.

Included studies

In total, the combined searches identified 15 completed studies that were eligible for inclusion in the review. Descriptive information for each study, including an appraisal of risk of bias for methodological domains, is presented in the Characteristics of Included Studies table.

Design All the studies were of a randomised trial design, with randomisation at the patient level for 14 trials. One trial (Whitehead 2002) randomised general practices to intervention or control groups.

The overall duration of trials including follow‐up ranged from 6 weeks (Strang 2002) to 14 months (Prins 2001), with a mean duration of 7.5 months. Four studies (Barrett 1992, Russell 2001, Strang 2002, Surawy 2005) measured final outcomes immediately after the termination of intervention (no follow‐up). The longest period of follow‐up after intervention was 8 months (Huibers 2004, O'Dowd 2000). The overall mean duration of follow‐up after intervention of 3.8 months for the 11 studies for which it could be calculated.

Seven studies reported obtaining ethical approval, and nine studies stated that patient consent had been obtained. Two studies made no mention of ethical approval or patient consent (King 1999; Russell 2001).

Sample sizes The mean sample size of studies was 91 subjects, ranging from 18 subjects in a randomised trial component of a larger series of exploratory studies (Surawy 2005), to 278 subjects in a trial conducted at three centres (Prins 2001). Nine studies reported using power calculation to estimate the required sample size prior to subject recruitment.

Comparison groups Studies used between two and four arms to conduct comparisons between groups. Not all arms of all studies were used in this review. Lloyd 1993 used a four arm trial combining psychological therapy with active or placebo immunologic therapy; only the two placebo arms were used in this review. Ridsdale 2004 used three arms comprising CBT, graded exercise therapy (GET), and a 'booklet and usual care' (BUC) group. This last group was described as a prospective cohort (not being randomised at the same time as the other groups), and was not used for comparison in this review.

Setting Eight studies were conducted in the UK, three in the USA, two in The Netherlands, and two in Australia.

Four studies were conducted in a primary care setting (general practice surgeries) (Huibers 2004; Ridsdale 2004; King 1999; Whitehead 2002), and eight in secondary care (hospital outpatients or psychology department clinics). The setting of the remaining three studies was unclear. Two studies by doctoral researchers (Stevens 1999, Strang 2002) recruited subjects from sources such as physicians, psychiatrists, advertisements and local CFS support groups, but did not specify the setting in which intervention occurred. The remaining study (Surawy 2005) did not specify sources of subject recruitment or the setting of intervention.

Participants The combined sample size across the 15 included studies was 1374 participants, of which 1043 participants met the inclusion criteria for this review. In three studies, participants with a diagnosis of CFS rather than chronic fatigue symptoms were selected for inclusion (Huibers 2004; King 1999; Ridsdale 2004). One study included additional treatment arms that were not eligible for the purposes of this review (Lloyd 1993). Ten studies gave reasons why not all patients eligible for inclusion were recruited to the study, of which seven studies reported the total number of patients eligible for inclusion. Only five studies reported the total number of patients assessed for eligibility.

Eleven studies provided extensive demographic information on their samples such as marital and occupational status, as well as age and gender. The remaining four studies (Lloyd 1993, Russell 2001, Whitehead 2002; Surawy 2005) provided only minimal demographic information comprising gender, mean age, or age range.

Age of participants Of the ten studies which stated age criteria for subject recruitment (or the age range of their eventual sample), four studies included participants under the age of 18 years, as well as adult participants. The lower age range of these studies was 17 years for one study (Lloyd 1993), 16 years for two studies (King 1999, Ridsdale 2004), and 15 years for one study (Whitehead 2002). The oldest upper age range was 75 years (King 1999, Ridsdale 2004). Six studies provided the mean age of their sample, and a further eight studies provided the mean ages of comparison groups from which the weighted overall mean age could be calculated. The overall mean age of subjects was 40.9 years in these 14 studies. One study (Surawy 2005) did not provide a mean age of the sample or comparison groups.

Gender composition of participants All studies reported the gender composition of their samples. 70.1% of subjects were female.

Duration of illness Three studies provided the mean duration of illness of their sample, and a further nine studies provided the mean illness duration of comparison groups from which the weighted overall mean illness duration could be calculated. The mean duration of illness in these subjects was 56.5 months (4.7 years).

Inclusion criteria All studies specified inclusion criteria requiring that participants had fatigue as their main or major complaint, the minimum duration of fatigue being six months in 12 studies, at least four months in one study (Huibers 2004), and at least three months in the two remaining studies (King 1999, Ridsdale 2004). There was heterogeneity of other recruitment criteria between studies. Seven studies used the 'CDC' ('Fukuda') criteria (Fukuda 1994) for inclusion. One of these studies (Prins 2001), waived the requirement of four of eight additional symptoms included in the CDC criteria to be present. Three studies (Sharpe 1996, Deale 1996, Surawy 2005) used the 'Oxford' criteria (Sharpe 1991) for participant inclusion. The sample in Deale 1996 fulfilled CDC as well as Oxford criteria. Two studies (Barrett 1992, Lloyd 1993) used the 'Australian' criteria (Lloyd 1988).

Three studies did not use standard CFS criteria. Two of these studies (King 1999, Ridsdale 2004) used a score of at least 4 on the Chalder fatigue scale (Chalder 1993) as the basis for inclusion. The remaining study (Huibers 2004) included subjects who scored 35 or more on the Dutch Checklist Individual Strength; Vercoulen 1999) and who had been completely absent from work for 6‐26 weeks on health grounds. These studies thus had samples suffering from chronic fatigue, of which a sub‐sample met CDC chronic fatigue syndrome criteria (28% in King 1999, 21% in Ridsdale 2004, and 44% in Huibers 2004). Only these subgroups were used in the current review.

Exclusion criteria Twelve studies specified exclusionary criteria, and two (Strang 2002, Whitehead 2002) did not. The remaining study (Russell 2001) did not stipulate any specific exclusion criteria, but did describe an assessment process for "readiness to engage in the rehabilitation process, group suitability, and the presence of other complicating psychological difficulties". It is not, however, clear whether this process resulted in exclusion of subjects. Eight studies excluded subjects with current mental disorder such as depression or bipolar disorder (n=3), psychosis (n=6), somatisation disorder (n=1), substance use (n=2), or who "were at significant risk of suicide or required urgent psychiatric treatment" (n=1). Two studies excluded those on psychiatric medication e.g. antidepressants, unless the dose was stable. Six studies excluded subjects whose symptoms were attributable to a comorbid condition or a diagnosis other than CFS. Other conditions excluding participation included pregnancy (n=2), learning difficulties precluding completion of questionnaires (n=1), organic brain syndromes (n=1), severe obesity (n=1), and asthma or ischaemic heart disease contraindicating a step‐test (n=1).

Other exclusionary criteria were: likely inability to attend all sessions e.g. non ambulatory subjects (n=9), insufficient English language to allow participation (n=4), ongoing physical investigations (n=2), fertility treatment (n=1), previous immunologic therapy (n=1), involvement in other previous or current CFS research (n=1).

Assessment of participants for recruitment In eleven studies, inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied by interviewing the subject to obtain a problem history. Some of these studies also made use of further measures such as structured or semi‐structured psychiatric interviews e.g. SCID (n=5), questionnaires or rating scales (n=7), physical examination of the patient (n=4), and laboratory investigations such as full blood count, biochemistry, autoantibody screening, thyroid function tests, and screening for infectious disease (n=6).

Two studies (Stevens 1999, Strang 2002) used a validated questionnaire as the sole method of determining recruitment eligibility, and two studies (Whitehead 2002, Ridsdale 2004) recruited subjects by referral from general practitioners who had themselves made a diagnosis of CFS using respective study criteria.

Interventions Comparison groups Ten studies compared a CBT model of therapy against a wait list (WL) (n=5) or 'treatment as usual' (TUC) control condition (n=6). Three of these studies (Barrett 1992, Prins 2001, O'Dowd 2000) had additional comparison arms consisting of guided support/education to control for non‐specific effects of therapy. A further study (Lloyd 1993) similarly compared CBT versus a TUC group, but both groups also attended clinic biweekly to receive intramuscular injections of saline as placebo for dialyzable lymphocyte extract (DLE). One study (Jason 2007) compared CBT with three comparison groups comprising cognitive therapy, anaerobic activity therapy, and relaxation therapy. The remaining studies compared CBT with comparison groups comprising relaxation therapy (Deale 1996), psychodynamic counselling (King 1999) and graded exercise therapy (Ridsdale 2004).

Manualisation Seven studies reported using manuals or treatment protocols for the CBT intervention (Deale 1996; Huibers 2004; Jason 2007; King 1999; Ridsdale 2004; Strang 2002; Prins 2001). Three studies reported testing of fidelity to manuals through audio or videotaping a random selection of CBT sessions (Jason 2007; King 1999; Prins 2001) and two studies measured fidelity to manuals through research team meetings (Deale 1996) or through supervision/checking written records (Huibers 2004).

Model of CBT Twelve studies used a 'traditional' model of CBT. Three studies deviated from traditional models of CBT (in terms of underlying theory as opposed to delivery). One of these studies (Stevens 1999) used a chronobiologically‐oriented treatment protocol (Nixon 1995), focusing on "sleep‐hygiene education, biofeedback‐assisted relaxation training, breathing re‐training, and cognitive therapy" (Stevens 1999). Another study (Strang 2002) used an element of personal mastery training (Reich 1981) alongside traditional CBT, and one study (Surawy 2005) used mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR; Kabat‐Zinn 1991) and mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (Segal 2002) as the basis of its treatment model.

Ten studies (Barrett 1992, Lloyd 1993, Sharpe 1993, Deale 1996, Stevens 1999, Prins 2001, Strang 2002, Whitehead 2002, O'Dowd 2000, Jason 2007) attempted to increase activity and reduce rest time as part of the CBT intervention. Other studies either attempted to tailor the patients' rest and activity towards levels compatible with limitations imposed by fatigue, or made no mention of activity/exercise in their intervention.

Delivery of intervention Ten studies delivered therapy on a one‐to‐one therapist to participant basis, including one study (Lloyd 1993) that invited subjects to bring a close family member with them, and a further study (Whitehead 2002) that used a booklet and diary keeping in addition to one‐to‐one GP contact. Five studies used a group therapy format, with group sizes of 8 or fewer subjects (Russell 2001), 8‐10 subjects (Strang 2002), 8‐12 subjects (O'Dowd 2000) or of unspecified size (Barrett 1992, Surawy 2005).

Therapist characteristics In six studies, therapists conducting CBT were clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, and/or trained cognitive (‐behavioural) therapists. One study (Barrett 1992) used a doctoral level psychologist as therapist, after an initial session with a psychiatrist. Two other studies (Stevens 1999, Strang 2002) also used doctoral level psychologists or their trained assistants to delivery therapy. Two studies (Whitehead 2002, Huibers 2004) used GPs to deliver therapy. One study (Jason 2007) used trained nurses with experience of delivering psychotherapy. Three studies did not specify the nature and training of therapists.

Supervision and protocol fidelity checks Six studies (Deale 1996, Prins 2001, King 1999, Huibers 2004, Ridsdale 2004, Jason 2007) specified that the therapists were supervised, and a further study (Whitehead 2002) offered telephone support to GP therapists, but this did not amount to formal supervision. Four studies (Prins 2001, King 1999, Huibers 2004, Jason 2007) assessed treatment fidelity (e.g. through blind assessment of video‐taped sessions by experienced therapists), and a further study (Deale 1996) stated that regular meetings were held to ensure sessions adhered to the treatment protocol.

Total, frequency and length of intervention sessions The frequency of sessions ranged from weekly in five studies (Barrett 1992, Sharpe 1993, Deale 1996, Stevens 1999, Surawy 2005), once every two weeks (Lloyd 1993, Prins 2001, Ridsdale 2004, O'Dowd 2000, Jason 2007), or with a variable gap between sessions not exceeding three weeks (Deale 1996, Strang 2002, Whitehead 2002, Huibers 2004). One study (King 1999) did not specify the frequency of sessions.

The minimum number of sessions specified was five to seven (Huibers 2004), and the maximum was sixteen (Sharpe 1993, Prins 2001), though in one study (Whitehead 2002) participants were asked to visit their GPs for therapy weekly or once every two weeks over 12 months.

Session length ranged from a minimum of 30 minutes (Huibers 2004) to a maximum of 150 minutes in a group format including a 30 minute break (Russell 2001). The modal length of session was 60 minutes. One study did not specify the length of treatment sessions (Surawy 2005), and in a further study (Whitehead 2002) session length was set by the treating GPs.

For the eleven studies in which total protocol treatment time could be determined, the minimum time was 4½ hours (Ridsdale 2004), and the maximum time 30 hours (including breaks) (Russell 2001). The mean total treatment specified in these studies' protocols was approximately 13 hours. In the five studies (Prins 2001, King 1999, Huibers 2004, Ridsdale 2004, Jason 2007) reporting actual treatment adherence across conditions, the mean time spent in CBT or control treatment was approximately eight hours.

Non‐intervention elements of care programmes Of the five studies (Deale 1996, Stevens 1999, Prins 2001, Huibers 2004, O'Dowd 2000) reporting whether non‐intervention aspects of treatment protocols were similar, only one (Prins 2001) noted differences (forbidding participants in the CBT condition to have physical investigations related to chronic fatigue syndrome during the intervention, but allowing participants in the 'guided support' and 'natural course' conditions to do so). Five studies explicitly stated that psychiatric medication e.g. antidepressants and anxiolytic drugs, was not forbidden by protocol. A further study (Prins 2001) noted that other treatments for CFS were forbidden by trial protocol (but made no mention of psychiatric medication). One study (Sharpe 1993) noted that two participants (7%) in its TUC condition received supportive psychotherapy, and that one participant (3%) in the CBT condition received counselling as part of vocational training. A further study (Huibers 2004) noted that 18% of CBT and 31% of TUC participants received "psychosocial co‐interventions" during the intervention period.

Outcomes A wide range of outcomes were used in the included studies. These include measures of this review's primary outcome (fatigue), as well as secondary outcomes such as physical functioning, depression, anxiety, acceptability of treatment, quality of life, occupational outcome, treatment compliance, dropout rate, health service resource use, illness attribution, and adverse effects. A range of rating methods were used including self‐report questionnaires (e.g. Chalder fatigue scale; Chalder 1993), observer‐rated outcomes (e.g. Karnofsky performance status scale; Karnofsky 1948) and physiological measures (e.g. step test, white cell count).

The most common measure of fatigue was the Chalder fatigue scale, followed by the Profile of Mood States (POMS) fatigue scale (McNair 1992). The most common measures of physical functioning were the Karnofsky scale and physical functioning subscale of the Medical Outcomes Survey (MOS) SF‐36 scale (Ware 1993). Commonly used measures of depression included the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1961), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond 1983), the latter also being the most common measure of anxiety along with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck 1990). Quality of life was most often measured by the SF‐36 in its entirety (including physical and mental functioning subscales). Other outcomes had more heterogeneous measures.

Six studies (Sharpe 1993, Deale 1996, Prins 2001, Huibers 2004, Ridsdale 2004, O'Dowd 2000) used pre‐determined criteria for successful outcomes on major measures which were deemed to represent clinical improvement. These outcomes were either of physical functioning (n=4) and/or fatigue (n=2).

Eight studies detailed dropout rates during treatment. Five studies reported dropout rates across the duration of the trial including follow‐up. One study (Whitehead 2002) presented data as to how many patients were using activity diaries at different points of follow‐up. One study reported only the mean dropout rate across all conditions (Jason 2007).

Excluded studies

CCDANCTR‐Studies and CCDANCTR‐Refs searches identified two studies (Friedberg 1994; Burgess 2001) that could not be immediately excluded by perusal of title or abstract, but were deemed not to meet the inclusion criteria for the review after scrutinising the full articles. Another ten studies identified through supplementary searches or personal communication with experts in the field were excluded after obtaining the full articles (Allen 2006, Bleichhardt 2004, Butler 1991, Candy 2004, Donta 2003, Gielissen 2006, Goudsmit 1996, Lyles 2003, Soderberg 2001, Taylor 2004). These are detailed in the table entitled Characteristics of Excluded Studies, with reasons for their exclusion from the updated version of this review.

Ongoing studies Searches of CCDANCTR‐Studies and CCDANCTR‐Refs identified a total of six ongoing studies (Wearden 2006, White 2005; Bleijenberg 2008; Carney 2008; Gibson‐Saxty 2002; Vissers 2008) that appear to meet the inclusion criteria for this review. No findings have yet been reported or obtained from these studies.

Studies awaiting assessment Two studies were identified which may fulfil review criteria but could not be included in the present review. The first study (Chalder 1997) randomised participants to either a self‐help booklet with specific advice (incorporating cognitive behavioural elements), or a no treatment control group. Participants were primary care patients complaining of fatigue who had previously presented with a possible viral illness. Inclusion criteria were deliberately broad, but included a subgroup of participants who met 'Oxford' criteria for CFS (12% of sample). However, the review authors have as yet been unable to obtain this subgroup data for inclusion in the review.

The second study (Powell 2001), compared "evidence based‐explanation of symptoms that encouraged graded activity" against standardised medical care. Delivery of intervention was in three groups (minimum, telephone, and maximum intervention groups) with varying amounts of face‐to‐face contact. Whilst each intervention included some cognitive‐behavioural principles, the review authors have been unable to establish with the study authors which, if any, of these interventions might satisfy inclusion criteria for this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

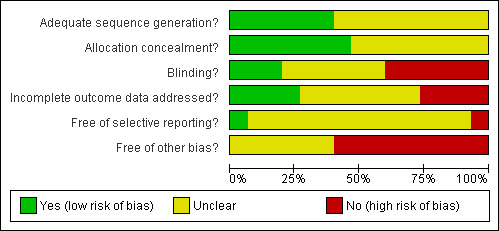

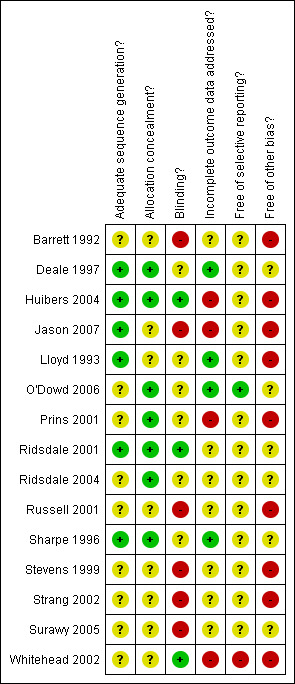

The methodological quality of the 15 studies included in the review was classified according to the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing the risk of bias. The risk of bias in each of the six domains of validity (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants/personnel/outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias) was rated independently by two review authors as 'high', 'low' or 'unclear', and differences between authors were reconciled. The final ratings are reported in the Characteristics of Included Studies table. A risk of bias summary graph (Figure 1) and summary figure (Figure 2) are also presented.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgement about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Sequence generation Whilst all studies specified that participants were randomly allocated to conditions (or GP practices randomised to treatment or control conditions in the case of Whitehead 2002), only seven studies specified the method of generating the sequence leading to random allocation, whether by computer (n=3) or random number table (n=4). No study specified a sequence generation method that was quasi‐ or non‐random, therefore these seven studies received a 'low' risk of bias rating for sequence generation, with the remaining eight studies receiving a rating of 'uncertain'.

Eight studies reported using blocked randomisation, and four studies stratified their samples, by presence of major depressive disorder (Sharpe 1993), by source of referral (Deale 1996), by length of work absence (Huibers 2004), or by duration and severity of fatigue (Ridsdale 2004). Allocation concealment Method of concealing assignment to condition from investigators and participants was described by seven studies through the use of numbered/opaque envelopes (variously described as being opened in front of the participant, immediately before his/her first session, or being handled by third parties).

Nine studies conducted preliminary univariate analyses of demographic and historical characteristics to check that randomisation had resulted in appropriate comparability of groups for demographic characteristics, with six reporting differences between groups. Sharpe 1993 reported that significantly fewer CBT participants were actively employed, and spent significantly more days in bed than TUC subjects. Deale 1996 reported that CBT participants were on average seven years older than the relaxation group. A greater number of the CBT group in Strang 2002 received disability compensation than the wait list group, while the CBT patients in Whitehead 2002 were younger and had a shorter duration of illness than their TUC counterparts. CBT subjects in Ridsdale 2004 had a longer median duration of fatigue than GET participants. In O'Dowd 2000, the CBT group had twice as many males as the other two arms.

Ten studies reported baseline differences between groups on outcome variables, either explicitly or via inference from confidence intervals in data tables. Of these ten studies, five reported that pre‐treatment differences did indeed exist. Stevens 1999 reported their CBT group had more morning insomnia, awoke more at night, had worse SF‐36 scores, and outperformed the WL group on step‐testing. The CBT participants in Whitehead 2002 were significantly more fatigued as measured by the Chalder fatigue scale. TUC subjects in Huibers 2004 were significantly more distressed as measured by the SCL‐90 scores but had better physical functioning as measured by MOS SF‐36 scores, whilst the CBT subjects in Ridsdale 2004 were more fatigued on the Chalder fatigue scale. CBT and anaerobic activity therapy groups in Jason 2007 had higher scores on a self‐efficacy measure than subjects in the relaxation therapy condition.

Blinding

One trial (O'Dowd 2000) stated that "both the participants and those administering the assessments were unaware of which cohort the subject was in", and indeed described its protocol as a "double‐blind randomised controlled trial". The only formal test of participant blinding to treatment group was in the case of active or placebo DLE injection in Lloyd 1993 (which described itself as a 'double blind, randomised, placebo controlled study'), which showed participants estimations of whether they received active or placebo DLE bore no significant correlation with actual treatment received. Only one study (Huibers 2004) specifically mentioned that researchers and treatment providers were not blinded to treatment allocation.

Of the four studies comparing CBT with other psychological/exercise therapy interventions, only two (King 1999 and Jason 2007) assessed treatment fidelity. Of these, one study (King 1999) used four independent assessors of recorded sessions and found differentiation in the management approaches of the two groups according to specified protocol. The other (Jason 2007) used a licensed and masters level psychologist (who had acceptable inter‐rater reliability) to rate a random sample of sessions according to therapists' use of techniques unique to the four treatment conditions, and indeed found the conditions were discriminant according to corresponding treatment manuals. A third study (Deale 1996) did not formally assess treatment fidelity, but did hold regular meetings to ensure protocol adherence. Two other studies (Prins 2001, Huibers 2004) also assessed treatment fidelity, not to differentiate CBT from other psychological or graded exercise treatment, but to check quality of CBT intervention.

The outcome variables in ten studies were assessed by self‐report scales or were based on physiological data (e.g. step‐test, white cell count). The remaining five studies included outcome measures that were based on observer assessment. Three of these studies used the Karnofsky scale. Of these, one study (Prins 2001) used "an independent clinical psychologist" to rate Karnofsky score who by this description is presumed to have been blind. Another study (Sharpe 1993) reported using a blinded researcher to rate participants Karnofsky status, on the basis of an interview made with participants by another researcher; however, the blinding status of the researcher conducting the interview was not specified. The remaining study to use the Karnofsky scale (Lloyd 1993) made no mention of blinding of assessor.

Two further studies used assessors to rate the change of participants on clinical dimensions. One study (Jason 2007) included a clinician global impression of change in the patient's overall functioning. No mention of blinding to treatment group was made. One study (Deale 1996) included an assessor rating of participants' degree of fatigue and disability through a structured interview. The assessors for this outcome were blinded through no test of blind was made.

Incomplete outcome data

Dropout rates Whilst not all studies differentiated between dropouts during therapy and those lost to follow‐up assessment, 14 studies reported dropout rates between baseline and end of treatment (or first post‐treatment assessment) by comparison group. The remaining study (Jason 2007) reported a mean drop‐out rate across all conditions.

Studies used varying criteria to define a dropout. For example, Ridsdale 2004 used a conservative estimate of failing to complete all six of the sessions of therapy specified in the study protocol, whereas Jason 2007 reports a participant was deemed to have dropped out if they completed four or fewer sessions out of 13 specified. Some studies (e.g. O'Dowd 2000) defined dropouts not on the basis of intervention sessions attended, but instead on whether participants attended follow‐up assessment or not. Another study (Prins 2001) used different criteria for dropout between groups; in the TUC group, only participants not attending assessments were classified as dropouts. In the CBT group, stopping coming to therapy was defined as a dropout, whereas in the guided support group, frequent non‐attendance was not classified as a dropout (a dropout was only counted if the participant formally declared an intention to withdraw). Whitehead 2002 reported dropouts as those unavailable for assessment at six months (31% of subjects). However, over 70% of subjects had terminated use of their treatment diaries or GP contact by that time.

The mean aggregate reported dropout rate of all 15 studies was 16.4%. Dropout rates ranged from 0% (Sharpe 1993) to 40% (Whitehead 2002), with six studies (Prins 2001, King 1999, Strang 2002, Whitehead 2002, Ridsdale 2004, Jason 2007) reporting dropout rates of over 20%. For the 14 studies reporting dropout rates by comparison group, the mean dropout rate for the CBT intervention was 16.8%. Of the four studies comparing CBT with another active psychological/graded exercise therapy, only one (Jason 2007) detailed that there were no differences between dropout rates of comparison groups (mean 25%). Dropout rates were broadly similar in the other three studies: 10% CBT vs 13.3% relaxation (Deale 1996); 36.3% CBT vs. 31.3% counselling (King 1999); and 28.6% versus 40% graded exercise therapy (Ridsdale 2004). Dropout rates between comparison groups also appeared broadly similar in the three studies comparing CBT with a guided support/education arm: 6.7% CBT versus 0% education and support (Barrett 1992); 36.6% CBT versus 30.9% guided support (Prins 2001); and 5.8% versus 10% education and support (O'Dowd 2000).

Reasons for dropouts Five studies (Barrett 1992, Lloyd 1993, Deale 1996, Stevens 1999, Whitehead 2002) reported reasons for dropouts during treatment by comparison group. In none of these studies did the reasons for dropout between groups appear dissimilar. A further study (Huibers 2004) reported reasons for dropout by CBT group but not for any other comparison group, and two other studies (King 1999, Ridsdale 2004) gave aggregate reasons for dropout not detailed by comparison groups. Four studies (Deale 1996, King 1999, Huibers 2004, Ridsdale 2004) investigated differences between dropouts and completers on demographic and baseline variables.

Method of dealing with missing data Five studies (Lloyd 1993, Prins 2001, Russell 2001, Whitehead 2002, O'Dowd 2000) did not provide means and/or standard deviation (SD) data for outcome variables. Baseline data for completers was also not inferable from the data presented by King 1999. Where data was required for this review, authors were contacted. Data were received from the authors of Prins 2001 (with the exception of two variables which were unobtainable) and King 1999.

Eight studies reported how they dealt with missing data (from dropouts or due to another reason such as inability/unwillingness to complete a walking test). Seven of these studies (Sharpe 1993, Deale 1996, Prins 2001, King 1999, Huibers 2004, Ridsdale 2004, O'Dowd 2000) presented sensitivity analyses (examining any differential effect of carrying forward data, using multiple value imputation, or abolishing dropouts from final analysis) or employed a full 'intention to treat' analysis carrying forward previous data values or assuming a negative outcome for dropouts.

Selective reporting

Only one study (O'Dowd 2000) made reference to deviation from its trial protocol, and only one study (Barrett 1992) specified an outcome variable which it did not report (delayed type hypersensitivity skin‐test). Two other studies indicated outcomes for which they did not then provide data (SF‐36 in King 1999; HADS in Whitehead 2002).

Whilst Lloyd 1993 collected data concerning the adverse effects of DLE injection, data referring to adverse effects of psychological treatment was not systematically presented by any study. One study (Sharpe 1993) noted reasons given by subjects for any deterioration during treatment, with two of four CBT participants who were subjectively 'worse' or 'much worse' after treatment blaming the treatment for deterioration. Huibers 2004 noted that 'no adverse event attributable to CBT was reported'. Jason 2007 reported numbers of participants who endorsed 'worse' or 'unchanged' to a 'Treatment made me feel' statement, but did not differentiate between the two categories or further investigate reasons, making inference of adverse effects impossible.

Other potential sources of bias

Five studies (Barrett 1992, Stevens 1999, Russell 2001, Strang 2002, Surawy 2005) made use of a wait‐list control condition, a design feature that may affect the natural course of fatigue or other symptoms, either in a directive direction through the implicit suggestion that recovery should be placed 'on hold' until treatment, or in a positive direction, through anticipated 'rescue' by treatment.

Less than half of the included studies reported the use of manuals or treatment protocols to standardise the CBT provided, and only three studies reported testing treatment fidelity through assessment of a random selection of video or audio tapes of sessions (King 1999; Jason 2007; Prins 2001), thus introducing uncertainty that therapists provided and adhered to CBT interventions in sessions.

Effects of interventions

Of 15 studies included in the review, 12 studies contributed data to primary and secondary outcomes, and three studies contributed to the secondary outcome of dropout only. Statistical heterogeneity was examined for each outcome, and where indicated to be statistically significant, I2 figures were reported in the text. The fixed effects model was used for all outcomes unless otherwise stated in the text. Subgroup analyses of the primary outcome were conducted where data from at least two studies were available for each sub‐group.

COMPARISON 01: COGNITIVE BEHAVIOUR THERAPY vs USUAL CARE Nine studies contributed to this comparison at post‐treatment (Prins 2001, Huibers 2004, O'Dowd 2000, Barrett 1992, Strang 2002, Lloyd 1993, Russell 2001, Whitehead 2002) with an additional study providing data at follow‐up (Sharpe 1993). The studies by Lloyd 1993, Russell 2001 and Whitehead 2002 provided post‐treatment data for the secondary outcome of attrition only. For the purposes of this comparison, short and medium‐term follow‐up outcomes were combined.

Primary outcome Seven studies contributed data to the primary outcome meta‐analysis. Measures used to assess fatigue symptoms and clinical response comprised the fatigue subscale of the CIS (Huibers 2004, Prins 2001), Chalder Fatigue Scale (O'Dowd 2000, Surawy 2005), POMS fatigue scale (Barrett 1992), Fatigue Severity Scale (Strang 2002) and a single‐item fatigue Likert scale (Sharpe 1993).

1) Reduction in fatigue severity Post treatment (Graph 01 01) Five traditional CBT studies and one mindfulness/compassion‐focused CBT study (373 participants in total) contributed to this outcome. The difference in fatigue mean scores between the CBT group and usual care group was highly significant in favour of the CBT group (SMD ‐0.39, 95% CI ‐.0.60 to ‐0.19). No statistical heterogeneity was indicated.

Short/medium term follow up (Graph 01 09) Four traditional CBT studies (330 participants in total) contributed to this outcome. The difference in fatigue severity mean scores between the CBT and usual care group was highly significant in favour of CBT (SMD ‐0.47, 95%CI ‐0.69 to ‐0.25). No statistical heterogeneity was indicated.

2) Clinical response Post treatment (Graph 01 02) Four studies (371 participants) contributed to this outcome. A total of 40% of participants in the CBT group showed clinical response to treatment, in contrast with 26% in the treatment as usual care group. The difference between the two groups was highly significant (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.76). No statistical heterogeneity was indicated.

Short term follow up (Graph 01 10) Three studies (353 participants) contributed to this outcome. No significant difference in clinical response rates was indicated between the CBT and usual care groups (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.00). Some heterogeneity was indicated (I2=40%), and a random effects model was used.

Secondary outcomes

1) Improvement in physical functioning Post treatment (Graph 01 03) Three traditional CBT studies and one mindfulness/compassion‐focused CBT study (318 participants in total) contributed to this outcome. Measures used to assess physical functioning comprised Karnofsky performance status scale (one study) and SF‐36 physical functioning subscale (three studies). The difference in physical functioning mean scores between the CBT group and the usual care group was not significant (SMD 0.11, 95%CI ‐0.32 to 0.54). Significant heterogeneity was indicated (I2 = 68%) and a random effects model was used.

Short/medium term follow‐up (Graph 01 11) Three traditional CBT studies (275 participants) contributed to this outcome. The difference in physical functioning mean scores between the CBT group and the usual care group was not significant (SMD 0.15, 95%CI ‐0.21 to 0.51). Significant heterogeneity was indicated (I2 = 53%) and a random effects model was used.

2) Reduction in depression symptoms Post treatment (Graph 01 04) Three traditional CBT studies and one mindfulness/compassion focused CBT study (183 participants in total) contributed to this outcome. Measures used to assess depression symptoms comprised the depression subscale of the HADS (two studies) and BDI (two studies). The difference in depression mean scores between the CBT group and the usual care was not significant (SMD ‐0.24, 95%CI ‐0.53 to 0.05). No statistical heterogeneity was indicated.

Short/medium term follow‐up (Graph 01 12) Two traditional CBT studies (149 participants) contributed to this outcome. Both studies used the HADS depression subscale to measure depression symptoms. The difference in depression mean scores between the CBT group and the usual care group was significant (MD ‐1.39, 95%CI ‐2.60 to ‐0.18). No significant heterogeneity was indicated.

3) Reduction in anxiety symptoms Post treatment (Graph 01 05) Three traditional CBT studies and one mindfulness/compassion focused CBT study (183 participants in total) contributed to this outcome. Measures used to assess anxiety symptoms comprised the anxiety subscale of the HADS (two studies), BAI (one study) and the STAI (one study). The difference in anxiety mean scores between the CBT group and usual care was significant (SMD ‐0.30, 95%CI ‐0.59 to ‐0.01). No statistical heterogeneity was indicated.

Short/medium term follow‐up (Graph 01 13) Two traditional CBT studies (149 participants in total) contributed to this outcome. Both studies used the HADS anxiety subscale of HAD to measure anxiety symptoms. The difference in anxiety mean scores between the CBT group and the usual care group was not significant (MD ‐1.38, 95% CI ‐2.91 to 0.16). No statistical heterogeneity was indicated.

4) Reduction in psychological distress Post treatment (Graph 01 06) Three traditional CBT studies (191 participants in total) contributed to this outcome. Measures used to assess psychological distress symptoms comprised the SCL‐90 (one study), the GHQ (one study) and a single item Likert scale of distress (one study). The difference in mean scores between the CBT group and usual care did not reach significance (SMD ‐0.27, 95%CI ‐0.56 to 0.01). No significant heterogeneity was indicated.

Short term follow‐up (Graph 01 14) One traditional CBT study (61 participants) contributed to this outcome. The difference in psychological distress mean scores between the CBT group and the usual care group was not significant (MD ‐0.24, 95% CI ‐28.95 to 28.37).

5) Improvement in quality of life Post treatment (Graph 01 07) One traditional CBT study (184 participants) contributed to this outcome. The measure used to assess improvement in quality of life comprised the Euro‐Qol. The difference in QoL improvement rates between the CBT group and the usual care group was not significant (OR 1.19, 95%CI 0.58 to 2.46).

Short term follow‐up (Graph 01 15) One traditional CBT study (125 participants) contributed to this outcome. The difference in QoL mean scores between the CBT group and the usual care group was significant (MD 8.00, 95% CI 0.68 to 15.32).

6) Acceptability of treatment No studies contributed to this outcome at post treatment or follow‐up.

7) Adverse effects No studies contributed to this outcome at post treatment or follow‐up.

8) Overall dropout rates Post treatment (Graph 01 08) Eight traditional CBT studies and one mindfulness/compassion‐focused study (586 participants in total) contributed data to this outcome. The attrition rate was 20.6% in the CBT group and 13.9% in the usual care group. The difference in attrition rate between the CBT group and the usual care group was significant in favour of usual care (OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.63). No statistical heterogeneity was indicated.

Short/medium term follow‐up (Graph 01 16) Four traditional CBT studies (413 participants in total) contributed data to this outcome. One study had no dropouts. The attrition rate was 22.7% in the CBT group and 14.8% in the usual care group. The difference was significant in favour of the usual care group (OR 1.46, 95% CI 0.52 to 4.10). Statistical heterogeneity was indicated (I2 = 56%) and a random effects model was used.

9) Occupational outcomes Short/medium term follow‐up (Graph 01 17 and Graph 01 18) Two traditional CBT studies contributed data to this outcome. They recorded occupational outcome in quite different ways, and therefore their results were not combined. One study (61 participants) reported the number of days of absenteeism during the 12‐month follow‐up period. The difference between the CBT group and usual care group was not significant (MD 4.35, 95% CI ‐50.06 to 58.76) (Graph 01 17). The other study (60 participants) reported improvement in work status at 12 months. The difference between the CBT group and the usual care group was significant (RR 3.17, 95% CI 1.47 to 6.81).

10) Health service resource use No studies contributed data on health service resource use.

Sub‐group analyses Subgroup analyses were conducted for the outcome of reduction in fatigue symptoms at post treatment.

a) Individual vs group therapy (Graph 05 01) Two studies used an individual CBT modality and four studies used group CBT. A highly significant difference in effect was shown for individual therapy and a significant difference of lesser magnitude was shown for group therapy when compared with usual care.

b) Treatment as usual vs waiting list (Graph 05 02) Three studies used a treatment as usual condition and three studies used a waiting list as the control condition. A highly significant difference in effect was shown for the CBT group when compared with treatment as usual. In contrast a non‐significant difference in effect was shown for the CBT group when compared with the waiting list condition.

c) Increased activity as component of CBT (Graph 05 03) Four studies incorporated an increased activity component into the CBT intervention and two studies tailored activity and rest to the needs of the individual or did not specify an activity schedule. A highly significant difference in effect was shown for the CBT group in which increased activity was incorporated when compared with usual care. In contrast, a non‐significant difference in effect was shown for the studies in which increased activity was not part of the CBT intervention when compared with usual care.

d) Number of sessions (Graph 05 04) Four studies offered eight or fewer sessions of CBT, and two studies offered more than eight sessions of CBT. A highly significant difference in effect of similar magnitude was shown for both CBT groups when compared with usual care.

COMPARISON O2: COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY vs OTHER PSYCHOLOGICAL THERAPIES Four studies contributed to this comparison at post‐treatment (Barrett 1992, Deale 1996, Prins 2001, O'Dowd 2000), with two additional studies contributing data at short‐term (King 1999) and medium term (Jason 2007) follow‐up. The studies compared a traditional CBT approach with relaxation (Deale 1996, Jason 2007), counselling (King 1999), guided support (Prins 2001) and education and support (O'Dowd 2000, Barrett 1992).

Primary outcome All six studies contributed data to the primary outcome meta‐analysis. Measures used to assess fatigue symptoms and clinical response comprised the fatigue subscale of the CIS (Prins 2001), Chalder Fatigue Scale (O'Dowd 2000, Deale 1996, King 1999), POMS fatigue scale (Barrett 1992) and Fatigue Severity Scale (Jason 2007).

1) Reduction in fatigue severity Post treatment (Graph 02 01) Four studies (313 participants in total) contributed to this outcome. The difference in fatigue mean scores between the CBT group and other psychological therapies group was highly significant in favour of the CBT group (SMD ‐0.43, 95% CI ‐0.65 to ‐0.20). No statistical heterogeneity was indicated.

Short term follow up (Graph 02 09) Four studies (294 participants in total) contributed to this outcome. The difference in fatigue severity mean scores between the CBT group and other psychological therapies group was significant in favour of CBT (SMD ‐0.47, 95%CI ‐0.83 to ‐0.11). Significant heterogeneity was indicated (I2 = 54%) and a random effects model was used.