Impact of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart failure (ExTraMATCH II) on mortality and hospitalisation: an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised trials (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2020 Jun 1.

Published in final edited form as: Eur J Heart Fail. 2018 Sep 26;20(12):1735–1743. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1311

Abstract

Aims

To undertake an individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis to assess the impact of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (ExCR) in patients with heart failure (HF) on mortality and hospitalisation, and differential effects of ExCR according to patient characteristics: age, sex, ethnicity, New York Heart Association functional class, ischaemic aetiology, ejection fraction, and exercise capacity.

Methods and results

Randomised trials of exercise training for at least 3weeks compared with no exercise control with 6-month follow-up or longer, providing IPD time to event on mortality or hospitalisation (all-cause or HF-specific). IPD were combined into a single dataset.We used Cox proportional hazards models to investigate the effect of ExCR and the interactions between ExCR and participant characteristics. We used both two-stage random effects and one-stage fixed effect models. IPD were obtained from 18 trials including 3912 patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction. Compared to control, there was no statistically significant difference in pooled time to event estimates in favour of ExCR although confidence intervals (CIs) were wide [all-cause mortality: hazard ratio (HR) 0.83, 95% CI 0.67–1.04; HF-specific mortality: HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.49–1.46; all-cause hospitalisation: HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.76–1.06; and HF-specific hospitalisation: HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.72–1.35]. No strong evidence was found of differential intervention effects across patient characteristics.

Conclusion

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation did not have a significant effect on the risk of mortality and hospitalization in HF with reduced ejection fraction. However, uncertainty around effect estimates precludes drawing definitive conclusions.

Keywords: Cardiac rehabilitation, Exercise training, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

Introduction

With increasing numbers of people living longer with symptomatic heart failure (HF), the effectiveness and accessibility of health services for HF patients have never been more important. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (ExCR) is recognised as integral to the comprehensive care of HF patients.1,2 Cardiac rehabilitation is a process by which patients, in partnership with health professionals, are encouraged and supported to achieve and maintain optimal physical health.2 Exercise training is at the centre of rehabilitation provision for HF. In addition, it is now accepted that programmes should be comprehensive in nature and also include education and psychological care, as well as focus on health and lifestyle behaviour change and psychosocial wellbeing.2,3

Systematic reviews have shown ExCR offers important health benefits for HF patients.4–7 The 2014 Cochrane review, based on aggregate trial data up to 12-month follow-up, reported a reduction in the risk of overall hospitalisation [relative risk (RR) 0.75, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.62–0.92] and HF-specific hospitalisation (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.46–0.80) compared with no exercise control.7 However, there is uncertainty as to whether there are differential effects of ExCR across HF patient subgroups. In 2004, the Exercise Training Meta-Analysis of Trials in Chronic Heart Failure (ExTraMATCH) Collaborative Group published an individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis based on nine randomised trials in 801 HF patients.8 ExTraMATCH reported a reduction in all-cause mortality [hazard ratio (HR) 0.65, 95% CI 0.46–0.92] and in the composite of mortality and hospital admission (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.56–0.93) with ExCR compared with no exercise control. There were no statistically significant treatment effects across subgroups. Given the small number of trials, patients, and events, those subgroup analyses are likely to be underpowered. As the ExTraMATCH analysis did not take into account the cluster (or trial-level) nature of the data, it is likely to have underestimated the precision of the treatment effect. Since the ExTraMATCH analysis, there have been publications of trials of ExCR in HF, including HF-ACTION, a large US National Institute of Health funded trial with 2331 HF patients recruited from 82 centres.9

The ExTraMATCH II Collaboration brings together the most comprehensive IPD meta-analysis of randomised trial data for ExCR in HF to date. Using contemporary IPD meta-analysis statistical methods, this study aimed to assess the impact of ExCR on the time to event outcomes (all-cause mortality, HF-specific mortality, all-cause hospital admission, and HF-specific hospital admission), and to identify subgroups of patients with HF that may respond differently to ExCR.

Methods

This study was conducted and reported in accordance with current IPD guidance and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Individual Participant Data (PRISMA-IPD) statement.10,11 The study was registered with the PROSPERO (CRD42014007170) and our full study protocol has been published elsewhere.12,13

Search strategy and selection criteria

Trials for inclusion were identified from the original ExTraMATCH IPD meta-analysis and the current Cochrane systematic review of ExCR for HF.7,8 The Cochrane review searched the following electronic databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Medline, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Conference proceedings were searched on Web of Science. Trial registers (Controlled-trials.com and ClinicalTrials.gov) and reference lists of all eligible trials and identified systematic reviews were also searched. No language limitations were imposed. Details of the search strategy used are reported in the study protocol.12

Trials which met the following criteria were eligible for inclusion in this analysis: (i) randomised trials of adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) with a diagnosis of HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) or HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) based on objective assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and on clinical findings; (ii) trial intervention (ExCR) that included an aerobic exercise training component performed by the lower limbs, lasting a minimum of 3 weeks,7 either alone or as part of a comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programme which may also include health education and/or a psychological intervention; (iii) a control arm which did not prescribe an exercise intervention; (iv) a minimum follow-up of 6 months; and (v) a sample size of at least 50 (to ensure that the logistical effort in obtaining, cleaning and organising the data was commensurate with the contribution of the dataset to the analysis).14,15

Data management

The principal investigators of included trials were invited by email to participate in this IPD meta-analysis and share their anonymised trial data. Included datasets had ethical approval and consent from their sponsors. The complete list of all requested variables and details regarding collaboration with principal investigators are reported in the study protocol.12 Each dataset was saved in its original format and then converted and combined into one overall master dataset with standardised variables. All files are stored on a secure password protected computer server managed in accordance with the data management standard operating procedures of the nationally registered Exeter Clinical Trials Unit. Data from each trial were checked on range, extreme values, internal consistency, missing values, and consistency with published reports. Data discrepancies or missing information were discussed with trial investigators. Access to data at all stages of cleaning and analysis was restricted to core members of the research team (O.C., R.S.T., F.C.W., and S.W.).

Specification of outcomes, subgroups, and risk of bias assessment

We sought patient level time to event data from investigators for the following outcomes: time to all-cause and HF-specific mortality, and time to first all-cause and HF-specific hospitalisation. We also sought IPD on the following pre-defined patient characteristics: age, gender, ejection fraction, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, HF aetiology (ischaemic or non-ischaemic), ethnicity (white or other), and baseline (pre-randomisation) exercise capacity [e.g. peak oxygen uptake (VO2)]. Study quality/risk of bias was assessed using the TESTEX quality assessment tool.16

Statistical analysis

A detailed statistical analysis plan was prepared (available from authors). All analyses were carried out according to the principle of intention to treat (i.e. patients included according to their randomised trial arm) and included only patients with observed baseline data (where required) and outcome data at follow-up. Where missing data were noted within an individual trial, contact with the author was attempted and data added if available. Given the relatively small levels of missing outcome and covariate data within trials, we did not undertake data imputation.

In the primary analysis, a two-stage approach was taken, with each trial first analysed using a Cox proportional hazards regression model, and then trial-specific estimates of treatment effect (HR) or treatment–covariate interactions (HR of the interaction effect) were combined across trials using a random effects model. A random effects model was preferred due to the high degree of clinical heterogeneity across the individual trials, which included different patient populations, types of ExCR intervention, and comparators.18 The overall estimate of the effect of ExCR for each outcome, both by trial and as a pooled estimate, was presented as a HR and 95% CI. Additionally, the I2 and _τ_2 statistics were reported alongside the associated _P_-value for the results of the main analyses.19

Secondary analyses were based on a one-stage meta-analysis approach. Due to failure of convergence of one-stage random effects models, which was likely to be due to the low level of statistical heterogeneity between trials (indicated by the _τ_2 statistic), a fixed effect approach was used: Cox regression models, stratified by trial. Stratification allowed the baseline hazard to vary between trials, rather than forcing the baseline hazards in individual trials to be proportionate to each other.20 To investigate subgroup effects, specifically interactions between ExCR effect and patient characteristics, we used the approach recommended by Riley et al.21 Continuous covariates were centred around the mean value within each trial; binary covariates were centred around the proportion within each trial. To present the results graphically, we performed individual subgroup one-stage fixed effect IPD meta-analyses.

To test the robustness of primary and secondary analyses, we undertook a number of pre-specified sensitivity analyses: (i) exclusion of the largest trial (HF-ACTION9); (ii) truncation of outcomes at 1-, 2-and 5-year follow-up. Small study effects were assessed for each outcome by funnel plot asymmetry and using the Egger test.17 Results are reported as estimated HRs with 95% CIs. All analyses were undertaken using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Study selection

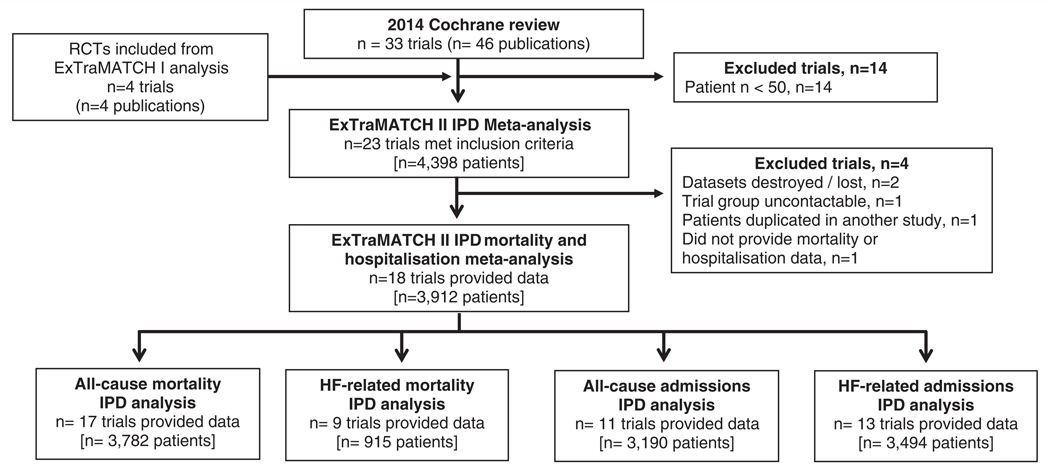

A total of 23 trials were deemed eligible for this IPD meta-analysis. Data from six trials have been analysed previously and were available from the ExTraMATCH database.22–27 We were unable to include data from three trials (355 patients); for two trials data were no longer available28,29 and the investigators of the other trial could not be contacted.30 Of the remaining 17 trials, 14 investigators responded positively and shared their trial data. After obtaining IPD, one trial31 was excluded as it was determined that it included patient data that overlapped with another trial.32 A further trial was not included as insufficient data were provided to allow calculation of survival time or time to hospitalisation.33 This resulted in the inclusion of 18 trials comprising 3912 patients (n = 1948 ExCR, n = 1964 control) with a median follow-up of 19 months for mortality outcomes and 11 months for hospitalisation outcomes. Figure 1 summarises the study selection process. Full citations of included trials are provided in the online supplementary Appendix S1 (ref. no. e1–e18).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. HF, heart failure; IPD, individual patient data; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Characteristics of included trials and participants

Patient baseline characteristics were well balanced between ExCR and control patients (Table 1). The majority of patients were male (75%), with a mean age of 61 years [standard deviation (SD) 13]. The mean baseline left ventricular ejection fraction was 26.7% (SD 8.1%); no included trials recruited patients with HFpEF (ejection fraction > 45%), and most patients were in NYHA functional class II (59%) or III (37%). Trials from Europe and North America were published between 1990 and 2012 (Table 2). Sample size ranged from 50 to 2130 patients. All trials evaluated an aerobic exercise intervention; six also included resistance training (online supplementary Appendix S1, ref. no. e3,e4,e8,e9,e14,e15) Exercise training was most commonly delivered in either an exclusively centre-based setting or a centre-based setting in combination with some home exercise sessions. Three trials were conducted in an exclusively home-based setting (online supplementary Appendix S1, ref. no. e4,e9,e13). The dose of exercise training ranged widely across trials. ExCR was delivered over a period of 12 to 90 weeks, with between 2 and 7 sessions per week; median session duration was between 15 and 120 min (including warm-up and cool-down). The intensity of exercise ranged between 50% to 85% peak VO2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | ExCR (_n_=1948) | Control (_n_=1964) | All (_n_=3912) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.3 ± 12.7 | 61.4 ± 13.2 | 61.3 ± 13.0 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1442 (74) | 1489 (76) | 2931 (75) |

| Female | 506 (26) | 475 (24) | 981 (25) |

| Baseline ejection fraction (%) | 26.8 ± 8.2 | 26.7 ± 8.1 | 26.7 ± 8.1 |

| NYHA class | |||

| I | 25 (1) | 28 (1) | 53 (1) |

| II | 1107 (59) | 1130 (60) | 2237 (59) |

| III | 700 (37) | 708 (37) | 1408 (37) |

| IV | 47 (3) | 26 (1) | 73 (2) |

| Aetiology | |||

| Ischaemic | 1094 (57) | 1080 (56) | 2174 (57) |

| Non-ischaemic | 809 (43) | 838 (44) | 1647 (43) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 1100 (70) | 1140 (72) | 2240 (71) |

| Non-white | 472 (30) | 445 (28) | 917 (29) |

| Peak VO2 (mL/kg/min) | 14.9 ± 4.4 | 15.0 ± 4.6 | 14.9 ± 4.5 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of included trials

| Study characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Publication year | |

| 1990–1999 | 2(11) |

| 2000–2009 | 12(67) |

| 2010–2012 | 3(17) |

| Unpublished | 1 (6) |

| Main study location | |

| Europe | 14 (78) |

| North America* | 4(22) |

| Study centre | |

| Single | 12 (67) |

| Multiple | 5(28) |

| Not reported | 1 (6) |

| Sample size | |

| 0–99 | 10 (56) |

| 1 00–999 | 7(39) |

| ≥1000 | 1 (6) |

| Duration of follow-up in dataset (months) | |

| Mortality | 18.6 (11.8–419) |

| Hospitalisation | 11.2 (2.6–98) |

| Intervention characteristics | |

| Intervention type | |

| Exercise only programmes | 5(28) |

| Comprehensive programmes | 12 (67) |

| Not reported | 1 (6) |

| Type of exercise | |

| Aerobic exercise only | 12 (67) |

| Aerobic plus resistance training | 6(33) |

| Dose of intervention | |

| Duration of intervention (weeks) | 30 (1 2–90) |

| Frequency (sessions per week) | 2.8 (2–7) |

| Length of exercise session (min) | 24 (15–120) |

| Exercise intensity, range | 40–80% maximum heart rate 50–85% peak VO2 12–18 Borg rating |

| Setting | |

| Centre-based only | 6(33) |

| Home-based only | 3 (1 7) |

| Centre-and home-based | 8 (44) |

| Not reported | 1 (6) |

Quality of included trials

The overall quality of included trials was judged to be moderate to good, with a median TESTEX score of 11 (range 9–14) out of a maximum score of 15 (online supplementary Table S1). The criteria of allocation concealment and physical activity monitoring in the control groups were met in only three trials (online supplementary Appendix S1, ref. no. e4,e7,e17); the other TESTEX criteria were met in 50% or more of trials.

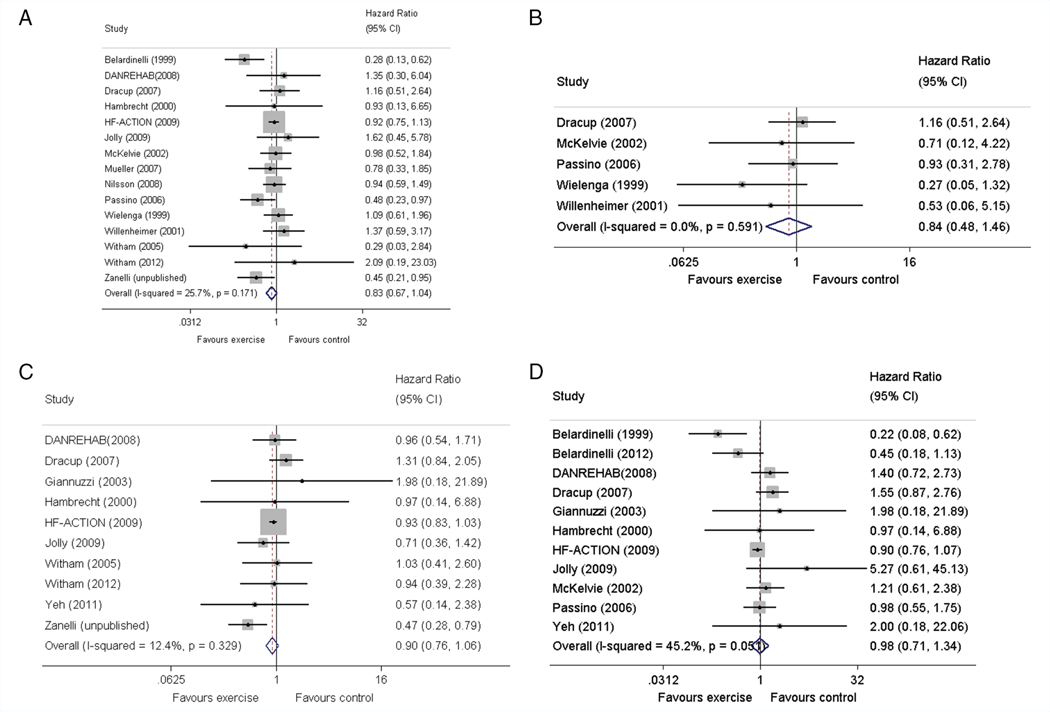

Effects of intervention on event outcomes

Compared with control, ExCR did not have a significant effect on mortality or hospitalisation. However, all time to event pooled treatment effects from random effects two-stage IPD meta-analysis were in favour of ExCR but with wide CIs [all-cause mortality: HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.67–1.04, P = 0.107, 17 trials, 3782 patients, I2 = 26%, _τ_2 = 0.04; HF-specific mortality: HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.49–1.46, P = 0.527, 9 trials, 915 patients, I2 = 0%, _τ_2 = 0.00; all-cause hospitalisation: HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.76–1.06, P = 0.210, 11 trials, 3190 patients, I2 = 12.4%, _τ_2 = 0.01; and HF-specific hospitalisation: HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.72–1.35, P = 0.902, 13 trials, 3494 patients, I2 = 45%, _τ_2 = 0.10] (Figure 2). These primary analysis results were broadly consistent across secondary and sensitivity analyses (online supplementary Tables S2–S5). Inferences did not change following the addition of trial level data from trials that met our study inclusion criteria but were not able to contribute IPD (data not shown, available from authors). There was no evidence of significant small study bias for the four outcomes (online supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Effect of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on mortality and hospitalisation across patient subgroups. (A) All-cause mortality. (B) Heart failure-specific mortality. (C) All-cause hospitalisation. (D) Heart failure-specific hospitalisation. CI, confidence interval.

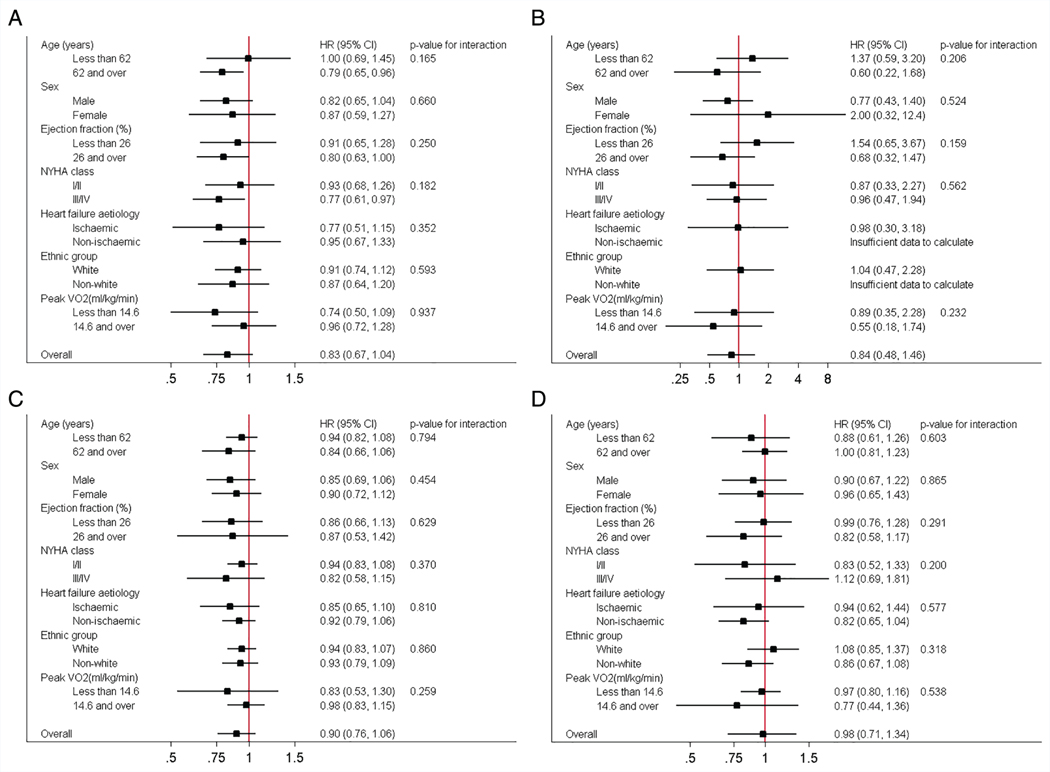

Differential treatment effects across patient characteristics (subgroups)

Interaction analyses for the two-stage model revealed no consistent interactions between the effect of ExCR and any of the pre-defined subgroups (age, gender, ejection fraction, NYHA class, HF aetiology, ethnicity and baseline peak VO2) for all-cause mortality, HF-related mortality, all-cause hospitalisation, or HF-related hospitalisation. For comparison of mortality and hospitalisation rates within each subgroup, the HR and associated 95% CI from individual subgroup one-stage IPD meta-analyses are shown in Figure 3, along with the _P_-value from the interaction test in the two-stage IPD meta-analyses. Some evidence of an interaction effect between ExCR and a patient characteristic (P < 0.05) was seen in four sensitivity analyses (online supplementary Tables S2–S5): (i) ExCR was associated with a larger reduction in all-cause mortality in older patients (P = 0.034) in the two-stage model with 2-year truncation; (ii) ExCR was associated with a larger reduction in HF mortality in older patients (P = 0.017) in the two-stage model with 2-year truncation; (iii) ExCR was associated with a larger reduction in HF-mortality in ischaemic patients (P = 0.047) in the one-stage model without truncation; and (iv) ExCR was associated with a larger reduction in all-cause hospitalisation in patients with lower baseline peak VO2 (P = 0.027) in the two-stage model with 1-year truncation.

Figure 3.

Effect of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on mortality and hospitalisation across patient subgroups. (A) All-cause mortality. (B) Heart failure-specific mortality. (C) All-cause hospitalisation. (D) Heart failure-specific hospitalisation. CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; NYHA, New York Heart Association; VO2, oxygen uptake.

Discussion

Compared with no exercise control, ExCR did not have a significant effect on mortality or hospitalisation in patients with HFrEF. Although we pooled IPD from 18 trials including 3912 patients, treatment effect estimates were imprecise. We found no strong evidence for a differential effect of ExCR according to patient characteristics.

Unlike the previous IPD meta-analysis, ExTraMATCH8, our analyses did not show a definitive benefit of ExCR in terms of either time to all-cause death or all-cause hospitalisation. The CIs around the effect of ExCR were wide and failed to reach statistical significance. The wide CIs may be due to several factors, including: (i) variation in the ExCR intervention across trials; (ii) variation in adherence to ExCR within trials; (iii) variation in treatment effect of ExCR among adherent patients; and (iv) variation in the composition/effectiveness of usual care within and across trials. A potential explanation for this reduction in strength of effect of ExCR on clinical events could be due to improvements in rates of mortality and hospitalisation with time as a result of the inclusion of more recent trials in this updated IPD analysis. More recent trials are more likely to have utilised prognostic innovations in usual care treatments for HF, including devices (resynchronisation and defibrillator therapy) and disease modifying drugs (beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists). However, the Cochrane systematic review of ExCR for HF showed that this may not be case. Meta-regression showed no statistical association between trial publication date and the magnitude of ExCR effect on mortality or hospitalisation.11,34 This Cochrane analysis also showed no association between the magnitude of ExCR effect and trial setting (single or multicentre), type of cardiac rehabilitation (comprehensive vs. exercise only), or ExCR dose.

Our finding of a lack of consistent evidence of a beneficial effect of ExCR for any HF patient subgroup agrees with both the previous ExTraMATCH and Cochrane 2014 analyses.7,8 However, these two previous studies had major limitations that are likely to have limited their ability to detect subgroup effects. ExTraMATCH included data on only 801 HF patients and observed 88 deaths and 300 patients with a composite outcome of death or hospitalisation, and therefore lacked statistical power. Using meta-regression analysis, the 2014 Cochrane review found no association between trial-level patient characteristics (age, gender, ejection fraction) and ExCR. However, meta-regression analysis is highly prone to study level confounding (ecological fallacy) and should be interpreted with great caution.35 Nevertheless, our findings are also consistent with the IPD subgroup interaction analyses from the multicentre HF-ACTION trial. The HF-ACTION investigators reported no significant interaction effect on their composite primary outcome (all-cause mortality or hospitalisation) between exercise training intervention and the subgroups of age (≤70 vs. > 70 years), gender, race (white vs. non-white), HF aetiology (ischaemic vs. non-ischaemic), ejection fraction (≤25% vs. > 25%), and NHYA class (II vs. III/IV).9,36

Strengths and limitations

Our ExTraMATCH II study has a number of strengths. We believe this to be the first IPD meta-analysis including sufficiently large numbers of HF patients (n = 3912) and events (701 all-cause deaths, 1642 first all-cause hospitalisations) to be able to identify differential effects of ExCR in patients with different characteristics. We were able to standardise the handling and analysis of time to event outcomes across trials. Our findings were broadly consistent across analytic approaches that included one-and two-stage IPD meta-analysis models and a range of sensitivity analyses. Finally, we found no evidence of publication bias. Whilst systematic reviews and meta-analyses of IPD from randomised trials are recognised as the gold standard for assessing intervention effects,37,38 our study has a number of limitations. First and foremost, there was a lack of consistency in how included trials with IPD in our analyses defined and collected clinical event outcome data. As noted in recent commentaries on clinical events in HF trials, with the exception of all-cause mortality, the collection and reporting of the other outcomes including cause-specific mortality and hospitalisation can be prone to confounding and bias.38 We made considerable efforts to contact study authors in order to clarify issues around the definition of hospitalisations and HF-specific deaths. Although we were able to resolve data issues in many cases, we recognise that a lack of consistency in outcome definition across included trials may exist, weakening the strength of our conclusions for these outcomes. Second, overall, IPD was available to ExTraMATCH II for 3912/4267 patients in 18/23 trials identified as eligible, equating to an omission of only 8% of all participants across all eligible trials. However, not all included trials collected IPD for the time to event outcomes or patient characteristics assessed in this study. The large multicentre HF-ACTION trial did not collect HF-specific hospitalisation, thus reducing our statistical power for this outcome. Although, across the trials that provided outcome data, the proportion of patients with missing clinical event or baseline covariate data was low, this may have introduced bias in our results. Finally, we did not have patient-level data on ‘ExCR dose’, i.e. adherence to duration, frequency and intensity of ExCR undertaken by an individual patient. Using IPD from HF-ACTION, Keteyian et al.39 found exercise volume [defined as metabolic equivalent of task (MET)-hour per week] to be a predictor for the composite outcome of all-cause mortality or hospitalisation (P = 0.03). Whilst this analysis indicates that patient level ‘ExCR dose’ is a key potential explanatory variable, these data were not available across the trials in our analyses.

Implications for practice and further research

In spite of the comprehensiveness of this IPD meta-analysis, findings of this study demonstrate that further evidence is still required to definitively assess the impact of ExCR on mortality and hospitalisation in patients with HFrEF; in particular, to increase the power to examine whether the effect of ExCR varies according to patient characteristics. To more reliably quantify the impact of ExCR on clinical outcomes and examine how these effects may vary across HF patients, there is an urgent need for trial investigators to more consistently collect, report, and share patient-level data in the future. Two central aspects of future data collection include a consensus on the definition, collection, and reporting of clinical event data, especially hospitalisation, plus the capture of data on patient-level adherence to the amount of exercise training during the ExCR intervention period. Our forthcoming IPD meta-analysis will examine the impact of ExCR on exercise capacity and health-related quality of life, and explore how this treatment effect may vary across according to HF patient characteristics.12,13

Conclusion

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation did not significantly reduce the risk of mortality and hospitalisation in patients with HFrEF. Although we pooled the IPD from a number of randomised trials, treatment effect estimates remain imprecise, which precludes drawing definitive conclusions. To allow definitive assessment of the effect of ExCR for patients with HF, and to investigate differential treatment effects across specific patient characteristics, a consensus in trial methodology needs to be reached that will allow more detailed and consistently recorded IPD to be routinely collected from clinical trials in ExCR.

Supplementary Material

supplementary material

Appendix S1. References of included trials.

Figure S1. Funnel plots. (A) All-cause mortality. (B) Heart failure-specific mortality. (C) All-cause hospitalisation. (D) Heart failure-specific hospitalisation.

Table S1. Assessment of quality using TESTEX scale of included studies in individual patient data meta-analysis.

Table S2. All-cause mortality – overall treatment effect and subgroups effects.

Table S3. Heart failure-specific mortality – overall treatment effect and subgroups effects.

Table S4. All-cause hospitalisation – overall treatment effect and subgroups effects.

Table S5. Heart failure-specific hospitalisation – overall treatment effect and subgroups effects in studies included in individual patient data meta-analysis.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of patient data from Dr. Rainer Hambrecht, Dr. Emanuella Zanelli, and the late Dr. Romualdo Belardinelli and late Dr. Pantaleo Giannuzzi. We thank Mr. Tim Eames, Exeter Clinical Trials Unit, for his advice and support on data management for this study, and Prof. Richard Riley, Professor of Biostatistics, Keele University, for his comments on a draft of this paper.

Funding

This work is supported by UK National Institute for Health Research funding (HTA 15/80/30). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

R.S.T. and H.M.D. are currently co-chief investigators and K.J. a co-investigator on a National Institute for Health Research funded programme grant designing and evaluating the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a home-based cardiac rehabilitation intervention for heart failure patients (RP-PG-1210–12004).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

Conflict of interest: All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bjarnason-Wehrens B, McGee H, Zwisler AD, Piepoli MF, Benzer W, Schmid JP, Dendale P, Pogosova NG, Zdrenghea D, Niebauer J, Mendes M; Cardiac Rehabilitation Section, European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Cardiac rehabilitation in Europe: results from the European Cardiac Rehabilitation Inventory Survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17:410–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR). The BACPR standards and core components for cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation 2017. 3rd edition.www.bacpr.com/resources/6A7_BACR_Standards_and_Core_Components_2017.pdf. (20 August 2018)

- 3.Dalal HM, Doherty P, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ 2015;351:h5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewinter C, Doherty P, Gale CP, Crouch S, Stirk L, Lewin RJ, LeWinter MM, Ades PA, Kober L, Bland JM. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials between 1999 and 2013. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015;22:1504–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haykowsky MJ, Timmons MP, Kruger C, McNeely M, Taylor DA, Clark AM. Meta-analysis of aerobic interval training on exercise capacity and systolic function in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fractions. Am J Cardiol 2013;111:1466–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smart N, Marwick TH. Exercise training for patients with heart failure: a systematic review of factors that improve mortality and morbidity. Am J Med 2004;116:693–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor RS, Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Briscoe S, Coats AJ, Dalal H, Lough F, Rees K, Singh S. Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(4):CD003331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piepoli MF, Davos C, Francis DP, Coats AJ; ExTraMATCH Collaborative. Exercise training meta-analysis of trials in patients with chronic heart failure (ExTraMATCH). BMJ 2004;328:189–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, Ellis SJ, Leifer ES, Kraus WE, Kitzman DW, Blumenthal JA, Rendall DS, Miller NH, Fleg JL, Schulman KA, McKelvie RS, Zannad F, Piña IL; HF-ACTION Investigators. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301:1439–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tierney JF, Vale C, Riley R, Smith CT, Stewart L, Clarke M, Rovers M. Individual participant data (IPD) meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: guidance on their use. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, Tierney JF; PRISMA-IPD Development Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Individual Participant Data: the PRISMA-IPD statement. JAMA 2015;313:1657–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor RS, Piepoli MF, Smart N, Coats AJ, Ellis S, Dalal H, O’Connor CM, Warren FC, Whellan D, Ciani O; ExTraMATCH II Collaborators. Exercise training for chronic heart failure (ExTraMATCH II): protocol for an individual participant data meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2014;174:683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor RS, Piepoli MF, Smart N, Coats AJ, Ellis S, Dalal H, O’Connor CM, Warren FC, Whellan D, Ciani O; ExTraMATCH II Collaborators. Exercise training for chronic heart failure (ExTraMATCH II): protocol for an individual participant data meta-analysis. PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews 2014. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42014007170. (20 August 2018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riley R, Lambert P, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ 2010;340:c221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed I, Sutton AJ, Riley RD. Assessment of publication bias, selection bias, and unavailable data in meta-analyses using individual participant data: a database survey. BMJ 2012;344:d7762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smart NA, Waldron M, Ismail H, Giallauria F, Vigorito C, Cornelissen V, Dieberg G. Validation of a new tool for the assessment of study quality and reporting in exercise training trials: TESTEX. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cleves M, Gould W, Marchenko Y. An Introduction to Survival Analysis Using Stata. 3rd edition College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riley RD, Lambert PC, Staessen JA, Wang J, Gueyffier F, Thijs L, Boutitie F. Meta-analysis of continuous outcomes combining individual patient data and aggregate data. Stat Med 2008;27:1870–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belardinelli R, Georgiou D, Cianci G, Purcaro A. Randomized, controlled trial of long-term moderate exercise training in chronic heart failure: effects on functional capacity, quality of life, and clinical outcome. Circulation 1999;99: 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hambrecht R, Gielen S, Linke A, Fiehn E, Yu J, Walther C, Schoene N, Schuler G. Effects of exercise training on left ventricular function and peripheral resistance in patients with chronic heart failure: a randomized trial. JAMA 2000;283:3095–3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKelvie RS, Teo KK, Roberts R, McCartney N, Humen D, Montague T, Hendrican K, Yusuf S. Effects of exercise training in patients with heart failure: the Exercise Rehabilitation Trial (EXERT). Am Heart J 2002;144:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willenheimer R, Rydberg E, Cline C, Broms K, Hillberger B, Oberg L, Erhardt L. Effects on quality of life, symptoms and daily activity 6 months after termination of an exercise training programme in heart failure patients. Int J Cardiol 2001;77:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zanelli E, Volterrani M, Scalvini S, Musmeci G, Campana M, Zappa C, Scotti C, D’Aloia A, Giordano A. Multidisciplinary non-pharmacological intervention prevents hospitalization, improves morbidity rates and functional status in patients with congestive heart failure [abstract]. Eur Heart J 1997;18(Suppl):647. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wielenga RP, Huisveld IA, Bol E, Dunselman PH, Erdman RA, Baselier MR, Mosterd WL. Safety and effects of physical training in chronic heart failure. Results of the Chronic Heart Failure and Graded Exercise study (CHANGE). Eur Heart J 1999;20:872–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson PM, Cockburn J, Newton PJ, Webster JK, Betihavas V, Howes L, Owensby DO. Can a heart failure-specific cardiac rehabilitation program decrease hospitalizations and improve outcomes in high-risk patients? Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17:393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austin J, Williams R, Ross L, Moseley L, Hutchison S. Randomised controlled trial of cardiac rehabilitation in elderly patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2005;7:411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klecha A, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Bacior B, Kubinyi A, Pasowicz M, Klimeczek P, Banyś R. Physical training in patients with chronic heart failure of ischemic origin: effect on exercise capacity and left ventricular remodeling. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007;14:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dubach P, Myers J, Dziekan G, Goebbels U, Reinhart W, Muller P, Buser P, Stulz P, Vogt P, Ratti R. Effect of high intensity exercise training on central hemodynamic responses to exercise in men with reduced left ventricular function. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;29:1591–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mueller L, Myers J, Kottman W, Oswald U, Boesch C, Arbrol N, Dubach P. Exercise capacity, physical activity patterns and outcomes six years after cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart failure. Clin Rehabil 2007;21: 923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gary RA, Dunbar SB, Higgins MK, Musselman DL, Smith AL. Combined exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy improves outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Psychosom Res 2010;69:119–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Briscoe S, Coats AJ, Dalal HM, Lough F, Rees K, Singh S, Taylor RS. Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2015;2:e000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson SG, Higgins JP. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med 2002;21:1559–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mentz RJ, Bittner V, Schulte PJ, Fleg JL, Piña IL, Keteyian SJ, Moe G, Nigam A, Swank AM, Onwuanyi AE, Fitz-Gerald M, Kao A, Ellis SJ, Kraus WE, Whellan DJ, O’Connor CM. Race, exercise training, and outcomes in chronic heart failure: findings from Heart Failure-a Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes in Exercise TraiNing (HF-ACTION). Am Heart J 2013;166:488–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chalmers I. The Cochrane Collaboration: preparing, maintaining, and disseminating systematic reviews of the effects of health care. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993;703:156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zannad F, Garcia AA, Anker SD, Armstrong PW, Calvo G, Cleland JG, Cohn JN, Dickstein K, Domanski MJ, Ekman I, Filippatos GS, Gheorghiade M, Hernandez AF, Jaarsma T, Koglin J, Konstam M, Kupfer S, Maggioni AP, Mebazaa A, Metra M, Nowack C, Pieske B, Piña IL, Pocock SJ, Ponikowski P, Rosano G, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Severin T, Solomon S, Stein K, Stockbridge NL, Stough WG, Swedberg K, Tavazzi L, Voors AA, Wasserman SM, Woehrle H, Zalewski A, McMurray JJ. Clinical outcome endpoints in heart failure trials: a European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association consensus document. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:1082–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keteyian SJ, Leifer ES, Houston-Miller N, Kraus WE, Brawner CA, O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Cooper LS, Fleg JL, Kitzman DW, Cohen-Solal A, Blumenthal JA, Rendall DS, Piña IL; HF-ACTION Investigators. Relation between volume of exercise and clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1899–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

supplementary material

Appendix S1. References of included trials.

Figure S1. Funnel plots. (A) All-cause mortality. (B) Heart failure-specific mortality. (C) All-cause hospitalisation. (D) Heart failure-specific hospitalisation.

Table S1. Assessment of quality using TESTEX scale of included studies in individual patient data meta-analysis.

Table S2. All-cause mortality – overall treatment effect and subgroups effects.

Table S3. Heart failure-specific mortality – overall treatment effect and subgroups effects.

Table S4. All-cause hospitalisation – overall treatment effect and subgroups effects.

Table S5. Heart failure-specific hospitalisation – overall treatment effect and subgroups effects in studies included in individual patient data meta-analysis.