Incidence and prevalence rates of diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia: An overview (original) (raw)

Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to report on the trends in incidence and prevalence rates of diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia over the last 25 years (1990–2015).

Design: A descriptive review.

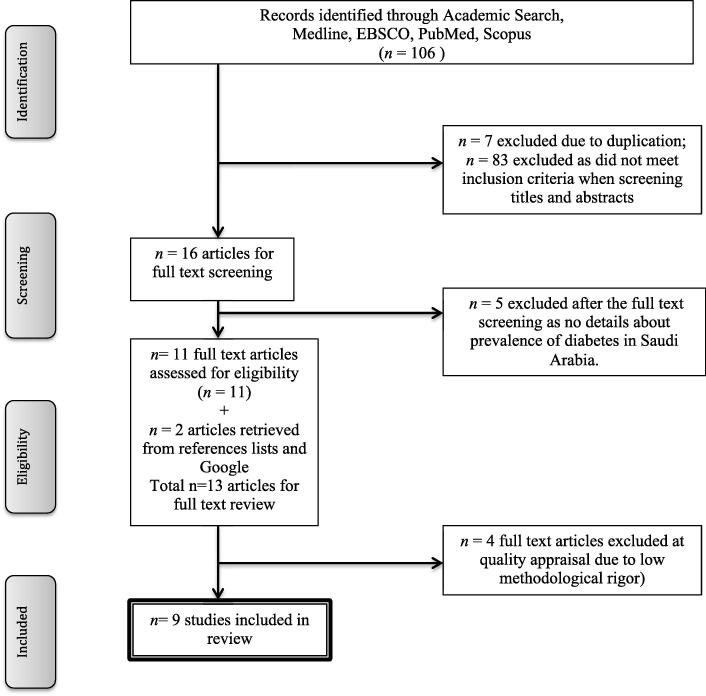

Methods: A systematic search was conducted for English-language, peer reviewed publications of any research design via Medline, EBSCO, PubMed and Scopus from 1990 to 2015. Of 106 articles retrieved, after removal of duplicates and quality appraisal, 8 studies were included in the review and synthesised based on study characteristics, design and findings.

Findings: Studies originated from Saudi Arabia and applied a variety of research designs and tools to diagnosis diabetes. Of the 8 included studies; three reported type 1 diabetes and five on type 2 diabetes. Overall, findings indicated that the incidence and prevalence rate of diabetes is rising particularly among females, older children/adolescent and in urban areas.

Conclusion: Further development are required to assess the health intervention, polices, guidelines, self-management programs in Saudi Arabia.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Prevalence, Incidence, Saudi Arabia

1. Introduction

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is a growing global health concern. In 2000, diabetes affected an estimated 171 million people worldwide; by 2011 this had increased to more than 366 million and numbers are expected to exceed 552 million by 2030 [1]. DM is a metabolic disease of multiple aetiologies, characterised by hyperglycaemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action or both, and associated with disturbance of carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism [2]. The three commonest types of diabetes are Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM), Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) [3].

The highest prevalence of diabetes overall is anticipated to occur in the Middle East and North Africa due to rapid economic development, urbanisation and changes in lifestyle patterns in the region [1]. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is not excluded from this global epidemic [4] and diabetes is the most challenging health problem facing this country [5]. According to a report by the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health, approximately 0.9 million people were diagnosed with diabetes in 1992, but this figure rose to 2.5 million people in 2010, representing a 2.7 times increase in the incidence rates in less than two decades. In 2015, 4660 patients with diabetes attended the family and medical clinics across Saudi Arabia [6]. This increasing burden of diabetes is due to various factors, including a rising obesity rate and an aging population [7].

Patients with diabetes commonly experience other associated chronic conditions, resulting in serious complications [3]. For example, the incidence of end stage renal disease is higher among patients with diabetes [8] and accounts for between 24% and 51% of those receiving renal replacement therapy [9]. Compared to the general population, patients with diabetes are two to four times more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, and two to five times more likely to die from this disease [10]. In addition to its impact on individuals, diabetes places a significant burden on healthcare services and the community as a whole [11]. Globally, diabetes accounted for 11% of the total healthcare expenditure in 2011; in Saudi Arabia, the annual cost of diabetes has been estimated at more than $0.87 billion [12].

It is essential to understand the epidemiology of diabetes in order to identify public health priorities, to generate policy initiatives and evaluate the effect of services in reducing the individual and social burden of diabetes [13]. Although prevalence estimates by countries and regions are provided by the International Diabetes Federation, there are substantial variations in time trends as these estimates are based on imputation [14]. To date, no systematic review has been reported on the incidence and prevalence of diabetes in Saudi Arabia. Considering the major socio-economic changes that have occurred in this country during the past few decades, and their marked impact on the lifestyles, eating habits and physical activities of the people of this region, along with the aging of the population, this is an important omission [12]. This review has therefore been conducted to report the trends in incidence and prevalence rates of diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia between 1990 and 2015.

2. Methods

2.1. Review design

This review employed a descriptive design to review and analyse studies reporting the incidence and prevalence rates of diabetes in Saudi Arabia. This approach is also referred to as correlational or observational design and is commonly used to obtain information about naturally occurring health states [15]. This descriptive study followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (2014) protocol for the review of prevalence and incidence studies, including search strategy, quality appraisal, data extraction and synthesis, results, discussion and conclusion.

2.2. Search strategy

A systematic literature search was performed to identify publications reporting the incidence and prevalence rates of diabetes in Saudi Arabia. Included publications focused specifically on studies describing the incidence and prevalence rates in relation to either a diagnosis of diabetes, or explicit blood glucose-level criteria for diagnosis of diabetes. Studies considering type 1 or type 2 diabetes, or both, were included as these account for over 90% of all diabetes [16]. Medical Subject Heading terms (MeSH) were used, including prevalence, incidence, diabetes mellitus, and Saudi Arabia. Synonyms for the identified concepts were generated including, “epidemiology” and “trend”; “type 1 diabetes” and “type 2 diabetes”. These concepts were combined using Boolean Operators (AND, OR). Four academic databases (Medline, EBSCO, PubMed and Scopus) were searched for relevant literature. The search was limited to English language papers published between 1990 and 2015. Papers published in languages other than English, and publication types other than primary studies (such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses, discussion papers, conference abstracts and dissertations) were excluded. In total, 106 citations of potential relevance were identified (Table 1). Initial screening of titles and abstracts revealed that 90% of these retrieved studies did not meet the review inclusion criteria, with 16 papers retained for full-text evaluation. Full text screening for relevance resulted in the exclusion of five further papers. Two articles were added from the reference lists of the reviewed articles and Google scholar.

Table 1.

Search terms, database and search output.

| Search No | Search Terms | Medline results | EBSCO results | PubMed results | Scopus results | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S 1 | Prevalence or epidemiology or trend | 579,280 | 1,061,711 | 2,656,747 | 2,749,216 | 7,046,954 |

| S 2 | Incidence | 229851 | 249,619 | 2355894 | 1,014,650 | 3,850,014 |

| S 3 | Diabetes mellitus | 495873 | 258,094 | 564756 | 699,008 | 2,017,731 |

| S 4 | Saudi Arabia | 9627 | 59,039 | 44900 | 34,024 | 147,590 |

| S 5 | S1and S2 and S3 and S4 with limits: date (1990–2015), Peer Reviewed, Human, Journal Article and English Language) | 12 | 15 | 61 | 18 | 106 |

2.3. Quality appraisal

These 13 articles were critically appraised for quality using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for studies reporting prevalence data [15]. All papers were evaluated on the basis of data relevance and methodological rigor, and papers that met a minimum of five of the nine criteria (see column headings, Tables 2 and 3) were included. The process resulted in the exclusion of four papers (Table 2; Fig. 1). The remaining nine studies employed appropriate quantitative designs for incidence and prevalence studies (Table 3).

Table 2.

JBI critical appraisal checklist applied for excluded studied reporting incidence and prevalence data.

| Author Name/Year | Sample was representative? | Participants appropriately recruited? | Sample size was adequate? | Study subjects and the setting described? | Data analysis conducted | Objective, standard criteria, reliably used? | Appropriate statistical analysis used | Confounding factors/subgroups/differences identified and accounted? | Subpopulations identified using objective criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abou-Gamel et al. (2014) | No | No | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Al-Orf (2012) | No | Unclear | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear |

| Alsenany and Al Saif (2015) | Yes | No | No | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Karim et al., (2000) | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

Table 3.

JBI critical appraisal checklist applied for included studies reporting incidence and prevalence data.

| Author Name/Year | Sample was representative? | Participants appropriately recruited? | Sample size was adequate? | Study subjects and the setting described? | Data analysis conducted | Objective, standard criteria, reliably used? | Appropriate statistical analysis used | Confounding factors/subgroups/differences identified and accounted? | Subpopulations identified using objective criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abduljabbar et al. [17] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | No |

| Al-Baghli et al. [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Al-Daghri et al. [19] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Al-Herbish et al. [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Al-Nozah et al. [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Al-Qurashi et al. [22] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Al-Rubeaan et al. (2015) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Al-Rubeaan [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Habeb et al. [18] | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection.

2.4. Data extraction

Data were extracted using a specifically designed data extraction table (Table 4), and examined, compared, discussed and agreed with all authors. Data were analysed descriptively, comparing and contrasting results across studies, taking into consideration the differences in date of study, sampling technique and sample size, age, setting, methods and type of diabetes.

Table 4.

Summary table of included studies.

| Authors (Date of publication) | Date of study | Sample size | Age | Type of diabetes | Sampling technique | Setting (urban / rural) | Method used | Incidence / prevalence per 100,000 or% | Overall per 100,000 or% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||||||||

| Abduljabbar et al. [17] | 1990–2007 | 438 | <15 years | T1DMa | Not reported | Dhahran, Eastern KSA (urban) | Not mentioned | 24.07 | 31.17 | 27.52 |

| Al-Herbish et al. [20] | 2001–2007 | 45, 682 | 0–19 years | T1DMa | Multi-stage stratified random sampling | Nationwide (rural & urban) | Self-report | 56.9 | 52.6 | 109.5 |

| Habeb et al. [18] | 2004–2009 | 419 | 0–12 years | T1DMa | Not reported | Al-Madinah (urban) | Self-report | 22.2 | 33.0 | 27.6 |

| Al-Baghli et al. [23] | 2004–2005 | 197, 681 | ≥30 years | T2DMb | Convenience sampling (approached participantsin their workplaces, major public places, malls and other venues) | Eastern Province (urban & rural) | FPGcCFBGdCCBGe & | 15.9% | 18.6% | 18.2% |

| Al-Daghri et al. [19] | 2011 | 9, 149 | 7–80 years | T2DMb | Cluster random sampling | Riyadh (Unknown) | FPGc | 34.7% | 28.6% | 31.6% |

| Al-Nozha et al. [24] | 1995–2000 | 16, 917 | 30–70 years | T2DMb | 2 stage, stratified cluster sampling | Nationwide (urban & rural) | FPGc | 26.2% | 21.5 | 23.7% |

| Alqurashi et al. [22] | 2009 | 6, 024 | 12–70 years | T2DMb | Convenience sampling (patients attending a primary care clinic) | Jeddah (King Fahad Armed Forces Hospital.) | Self-report | 34.1% | 27.6% | 30.0% |

| Al-Rubeaan et al. (2015) | 2007–2009 | 18, 034 | ≥30 years | T2DMb | Random sampling | Nationwide (urban & rural) | FPGc | 29.1% | 21.9% | 25.4% |

| Al-Rubeaan [21] | 2007–2009 | 23,523 | 0– ≥18 years | T1DMa/T2DMb | Multistage stratified cluster sampling | Nationwide (urban & rural) | FPGc | 44.32% (T1DM)47.06% (T2DM) | _55.68% (T1DM)_52.94% (T2DM) | 10.84% |

2.5. Data synthesis

Multiple sources of heterogeneity (research region and site, types of diabetes and age groups) were observed across the included studies. The heterogeneity was explored qualitatively by comparing the characteristics of the included studies. Studies were grouped according to the type of diabetes (Table 5).

Table 5.

General characteristics of included studies.

| Central region | East region | West region | Nationwide | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country regions | 1 study | 2 study | 2 studies | 4 studies |

| Al-Daghri et al. [19] | Abduljabbar et al. [17], Al-Baghli et al. [23] | Habeb et al. [18], Alqurashi et al. [22] | Al-Herbish et al. [20], Al-Rubeaan [21], Al-Nozha et al. [24], Al-Rubeaan et al. [25] | |

| Type of diabetes | Type 1 diabetes | Type 2 diabetes | Both types | |

| 4 studies | 6 studies | 4 studies | ||

| Abduljabbar et al. [17] | Al-Daghri et al. [19] | Al-Daghri et al. [19], Al-Rubeaan [21] | ||

| Habeb et al. [18] | Al-Rubeaan [21] | |||

| Al-Herbish et al. [20] | Alqurashi et al. [22] | Alqurashi et al. [22], Al-Nozha et al. [24] | ||

| Al-Rubeaan [21] | Al-Baghli et al. [23] | |||

| Al-Nozha et al. [24] | ||||

| Al-Rubeaan et al. [25] | ||||

| Age groups | Children/ adolescent | Adult | ||

| 4 studies | 6 studies | |||

| Abduljabbar et al. [17] | Al-Daghri et al. [19] | |||

| Habeb et al. [18] | Al-Rubeaan [21] | |||

| Al-Herbish et al. [20] | Alqurashi et al. [22] | |||

| Al-Rubeaan [21] | Al-Baghli et al. [23] | |||

| Al-Nozha et al. [24] | ||||

| Al-Rubeaan et al. [25] | ||||

| Research setting | Tertiary hospital | Primary healthcare center (PHCC) | Nursing home and households | |

| 4 studies | 3 studies | 3 studies | ||

| Abduljabbar et al. [17] | Al-Daghri et al. [19] | Al-Herbish et al. [20] | ||

| Habeb et al. [18] | Al-Baghli et al. [23] | Al-Rubeaan [21] | ||

| Alqurashi et al. [22] | Al-Nozha et al. [24] | Al-Rubeaan et al. [25] | ||

| Al-Baghli et al. [23] |

3. Findings

Of the nine included studies, two examined incidence rates [17,18], four reported the prevalence rates of T1DM among children and adolescents [19–22], while six studies reported the prevalence rate of T2DM among adults [19,21–25]. These studies included only Saudi nationals, with sample sizes ranging from 419 to 45,682. Four studies were conducted nationwide [20,21,24,25], one study was conducted in Dhahran (Eastern region) [17]; one recruited across the entire Eastern province [23], and one each were conducted in Riyadh (Central region) [19], Jeddah (Western region) [22] and Al-Madina (Western region) [18]. Four were conducted using random sampling techniques, two used convenience sampling, one used multistage stratified cluster sampling and the remaining two did not report the sampling technique used. The research settings of three studies were tertiary hospitals [17,18,22], two were set in primary health centres [19,24], three in households [20,21,25] and one was conducted in a range of settings including governmental public hospitals and primary health centres [21,23]. The reported prevalence and incidence rates of diabetes varied widely across different geographical areas (Tables 4 and 5).

3.1. Type 1 diabetes

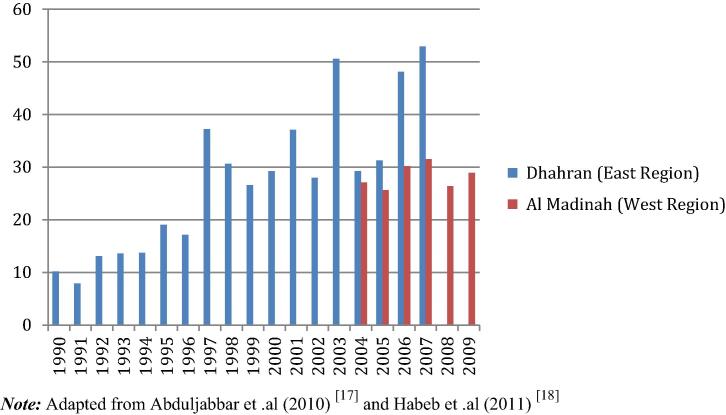

Two studies reported the incidence rates of T1DM between 1990 and 2009 in Dhahran, Eastern KSA [17] and in Al Madina, North West KSA [18]. The samples in these two studies were children and adolescents from 0 to 14 years old. The cumulative incidence rates of T1DM among these children and adolescents were very similar, at 27.52 per 100,000 and 26.7 per 100,000, respectively (Table 4). In the Dhahran study, an increasing trend in childhood and adolescence incidence rate of T1DM between 1990 and 2007 was observed (Fig. 2). The incidence rates of T1DM doubled among children in less than two decades, from 18.05 per 100,000 children between 1990 and 1998 to 36.99 per 100,000 children between 1999 and 2007, indicating an average annual increase in incidence of 16.8% [17]. In Al-Madina, no significant increase was observed in the overall annual incidence rate between 2004 and 2009 in Al-Madina[18]; children aged 0 to 4 years had an estimated incidence rate of 17.1 per 100,000, while children aged 5 to 9 and 10 to 12 years had incidence rates of 30.9 and 46.5 per 100,000, respectively. Children aged 5 to 9, and 10 to 12 years had 1.8 and 2.7 times greater risk of developing T1DM than children aged 0 to 4 years [18].

Fig. 2.

Incidence rate of T1DM between 1990 and 2009 in Saudi Arabia.

A nationwide study reported the prevalence of T1DM among children and adolescents aged up to 19 years at 109.5 per 100,000 between 2001 and 2007 [20]. The prevalence rate was highest among adolescents aged 13 to 16 years (at 243 per 100,000) and lowest among children aged 5 to 6 years at 100 per 100,000 [20]. Another nationwide study found the prevalence of T1DM between ages 13 and 18 years, at (0.46%), higher than amongst those who aged under 12 years at (0.37%) between 2007 and 2009 [21]. In addition, two studies conducted in Riyadh [19] and Jeddah [22] found that the prevalence rates of diabetes at younger ages between 7–17 and 12–19 years respectively, were higher in female than male populations.

In terms of gender, the incidence of T1DM was significantly higher among females (at 31.17 per 100,000) than males (at 24.07 per 100,000) in Dhahran, KSA between 1990 and 2007 [17]. In females the highest incidence rate was reported for those aged 7–11 years and for males similar rates were reported for those aged 8–12 years [17]. Females had significantly higher incidence rates than males (at 33.0 per 100,000 compared to 22.2 per 100,000 respectively) in Al-Madina between 2004 and 2009 [18]. A nationwide study found that prevalence was higher among females than males between 2007 and 2009. [21].

The highest prevalence rate (at 126 per 100,000) was recorded in the central region where the capital city of Riyadh is located and the environment is mostly urban; the lowest prevalence rate (at 48 per 100,000) was reported in the eastern region of KSA, which is predominantly rural [20]. Between 2007 and 2009, the majority (77.2%) of cases of T1DM was documented in urban rather than rural areas (at 22.7%) [21].

3.2. Type 2 diabetes

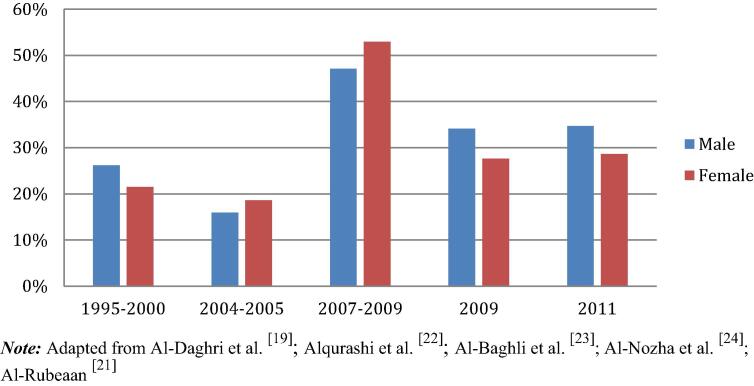

Prevalence rates of T2DM were reported in six studies, three of which were nationwide [21,24,25]. Of the remainder, one study was conducted in Riyadh [19], one in Jeddah [22] and one in the Eastern province [23]. All these studies reported prevalence rates of T2DM in different years between 1995 and 2011 and included only Saudi nationals aged between 7 and 80 years (Table 4). The studies demonstrated varying prevalence rates in different geographical regions in the country, ranging from 18.2% (in 2004–2005) in the study conducted in the Eastern province [23] to 31.6% in 2011 in the study conducted in Riyadh [19], nationwide prevalence rate increased from 23.7% between 1995 and 2000 to 25.4% between 2007 and 2009 [24,25]. When plotted figuratively, these six studies indicate a clear trend of overall increasing prevalence of T2DM with time (Fig. 3). Four studies reported significantly higher prevalence rates for T2DM in males than in females; one regional study from the Eastern province [23] and two nationwide studies, conducted between 2004 and 2005 [25] and between 2007 and 2009 [21] reported significantly higher prevalence rates for T2DM among females than males but these studies recruited by convenience and multistage stratified cluster rather than random sampling. Of the studies, which recruited using probability sampling (and for one of the two studies that used convenience sampling), there was an increasing prevalence of T2DM for both genders between 1995 and 2011, with higher prevalence rates among males than females (Fig. 3). Furthermore, T2DM was reportedly more prevalent among people in urban areas (at 25.5% compared to 19.5%) than in rural areas, and prevalence rates were highest in the northern region (at 27.9%) and lowest in the southern region (at 18.2%) between 1995 and 2000 [24].

Fig. 3.

Prevalence rate of T2DM between 1995 and 2011 in Saudi Arabia.

Between 2007 and 2009, prevalence rates amongst those with monthly incomes less than 4000 Saudi Riyal (SR; approx. 1067 USD) were higher among those in urban areas (27.2%) than those in rural areas (25.7%) [21]. However, no significant difference was reported in prevalence rates of urban and rural residents with monthly incomes of 8000SR (approx.. 2134 USD) and higher [25]; at a certain level of wealth, affluence appears to overcome the influence of residential area. Other differences noted included the mean age of diagnosis of the disease, reported as 53.4 years for females and 57.5 years for males [22]. In geographical terms, T2DM was most prevalent in the northern regions and least in the southern regions between 1995 and 2000 [24]. In terms of socio-demographic characteristics, in the Eastern Province the prevalence of T2DM was higher in individuals who were widowed (39.1%), unemployed (31.9%), and uneducated (32.3%) between 2004 and 2005 [23].

4. Discussion

The findings of this review indicate that diabetes mellitus is a growing health problem in Saudi Arabia. The findings broadly reflect high incidence rates of T1DM across the country, with rates rising particularly amongst children. One study conducted in the western region showed no increase in T1DM for the 5-year period between 2004 and 2009, but this may be due to the study’s limitation of including children only up to age 12 years [18]. Other studies indicate a significant increase in incidence rates of T1DM amongst groups older than 12 years [17,20]. This review’s findings concur with and expand on those of a report by the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health [17] as well as the latest report of the International Diabetes Federation (2015). The findings are also broadly consistent with epidemiological studies from several areas of Asia, Europe and North America, where the annual growth rates for T1DM have been reported at 4.0%, 3.2% and 5.3% respectively [26]. The latest report by the International Diabetes Federation cites 16,100 children aged 0–14 living with T1DM in Saudi Arabia, with an incidence of 31.4 new cases per 100,000 population [1]. The national incidence rate is higher than the incidence rates in Dhahran [17] and Al-Medina [18], reported in this review at 27.5 per 100,000 and 26.7 per 100,000, respectively. This implies an increase in new cases of T1DM in the country. Overall, studies included in this review recorded a higher incidence of T1DM among females than males. The International Diabetes Federation reported that the highest incidence rate of diabetes should be expected among females rather than males by 2030 [1]. The reason for this is uncertain; gender differences are often related environment and culture, whilst genetic factors are generally assumed to play a major role in the development of T1DM [27].

Contradiction of this reported higher incidence among females, Cucca et al. [28] found a greater prevalence among males. This seems to derive from the higher incidence rates of T1DM reported amongst males of European populations, which is not the case in non-European countries like Saudi Arabia [29]. Regardless of the gender distribution, the high rates of T1DM among children in Saudi Arabia are likely to increase burden on the country’s healthcare systems, as T1DM is implicated in the development of a wide range of end-organ complications. It has recently has also been associated with the development of obesity and overweight in early adulthood [30], which are independent risk factors for health problems such as cardiovascular disease and cancers. As with T1DM, a steady rise was also noted in the prevalence rates of T2DM especially during the years 2004–2005 and up to 2011, affecting both genders. This finding is widely supported by a number of research studies conducted in Saudi Arabia and other Arabian countries [31]. An alarming increase from 10.6% in 1989 to 32.1% in 2009 was documented in a systematic study conducted in Saudi Arabia, although some of those included in the review were non-Saudis [31]. Increased obesity, the popularity of fast foods, smoking, and sedentary lifestyles may explain recent increases in the prevalence of T2DM; the incidence of obesity, for instance, has been reported to be as high as 75% among females living in Saudi Arabia [32]. The higher prevalence of diabetes in urban rather than rural areas, where lifestyle changes are more prominent, lends support to the link between diabetes and life style risk factors. However, whilst affluence was clearly influential, so was poverty, in the Eastern province at least, and at higher incomes the link with urban living was lost [23].

Prevalence rates of T2DM were found to be higher among males than females although the age of onset was reported as earlier among females than males (at 53.4 years and 57.5 years) [22]. This finding is contrary to a study of Saudi adult patients at a primary healthcare centre, which reported a higher incidence among females (58%) than males (42%), but this discrepancy may be related to the well-recognised greater willingness of females than males to consult healthcare practitioners. In addition, females are also reported as more willing than males to adhere to diabetes daily management (e.g. restricted diet, monitoring blood-glucose, taking medication and regular foot-care) [33]. These findings call for prompt attention by the Ministry of Health especially because the heaviest burden of diabetes (of both type 1 and type 2) is its potential to progress to serious complications [34]. Awareness campaigns are viewed as the best option to at least initiate recognition of the need to modify unhealthy lifestyles, but recent campaigns launched in Saudi Arabia have not been successful so far [31]. Government-supported interventions are required to provide programs aimed at both preventing the development of diabetes and promoting self-care and management of the disease. The findings of this review highlight the importance of introducing measures into the Saudi healthcare system to update the knowledge and skills of all healthcare professionals involved with diabetes management to provide high quality diabetes care [31]. This is particularly important given the knowledge deficits reported in the nursing workforce both internationally and in Saudi Arabia [35,36].

4.1. Limitations of this review

Several limitations must be noted. First, this review was limited to T1DM and T2DM; it did not include the prevalence and incidence rates of gestational diabetes mellitus or childhood/adolescent onset of T2DM. Future reviews should consider each of these types of diabetes. Second, differences in assessment and diagnosis methods for diabetes have resulted in changed diagnosis criteria over time and heterogeneous methods and criteria were observed over time, across regions, and for different types of diabetes in the studies, resulting in some lack of statistical precision.

5. Conclusion

This is the first comprehensive review of the incidence and prevalence rates of T1DM and T2DM in Saudi Arabia. These were found to be high and rising, particularly among women. Females had higher incidence rates of T1DM among children and adolescents than males, and older age groups of children and adolescents had higher incidence rates of T1DM than younger age groups. The incidence rate of T1DM was higher in the central region of the country. Greater prevalence of T2DM was reported among those living in urban than rural areas, but there were socio-economic as well as geographical predisposing factors. This review recommends that urgent attention is paid to develop, support and implement health interventions, guidelines and policies nationwide, to assist in the prevention, diagnosis, management and promotion of self-management of diabetes. For the future, well-designed epidemiological studies are required to allow for more accurate and regular monitoring of the incidence and prevalence rates of diabetes across Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia.

Contributor Information

Abdulellah Alotaibi, Email: Abdulellah.M.Alotaibi@student.uts.edu.au, abaadi1982@hotmail.com.

Lin Perry, Email: Lin.Perry@uts.edu.au.

Leila Gholizadeh, Email: Leila.Gholizadeh@uts.edu.au.

Ali Al-Ganmi, Email: ali.h.al-ganmi@student.uts.edu.au.

References

- [1].International Diabetes Federation . IDF Diabetes Atlas. 7th ed. 2015. [cited 2015 July 2016]. Available from: http://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/EN_6E_Atlas_Full_0.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Supplement 1):S62–9. doi: 10.2337/dc10-s062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].International Diabetes Federation . IDF Diabetes Atlas. 6th ed. 2014. [cited 2015 april 14]. Available from: http://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/EN_6E_Atlas_Full_0.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Alhowaish AK. Economic costs of diabetes in Saudi Arabia. J Family Commun Med. 2013;20(1):1. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.108174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tabish SA. Is diabetes becoming the biggest epidemic of the twenty-first century? Int J Health Sci. 2007;1(2):V. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].The Ministry of Health Statistics report 2015. [cited 2015 5th Nov]. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Pages/default.aspx.

- [7].Kearns K, Dee A, Fitzgerald AP, Doherty E, Perry IJ. Chronic disease burden associated with overweight and obesity in Ireland: the effects of a small BMI reduction at population level. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Narres M, Claessen H, Droste S, Kvitkina T, Koch M, Kuss O, et al. The incidence of end-stage renal disease in the diabetic (compared to the non-diabetic) population: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bell S, Fletcher EH, Brady I, Looker HC, Levin D, Joss N, et al. End-stage renal disease and survival in people with diabetes: a national database linkage study. QJM. 2015;108(2):127–34. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Roper NA, Bilous RW, Kelly WF, Unwin NC, Connolly VM. Cause-specific mortality in a population with diabetes south tees diabetes mortality study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(1):43–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zimmet P, Alberti K, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001;414(6865):782–7. doi: 10.1038/414782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Naeem Z. Burden of Diabetes Mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Sci. 2015;9(3):V. doi: 10.12816/0024690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tracey ML, Gilmartin M, O’Neill K, Fitzgerald AP, McHugh SM, Buckley CM, et al. Epidemiology of diabetes and complications among adults in the Republic of Ireland 1998–2015: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2818-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tamayo T, Rosenbauer J, Wild S, Spijkerman A, Baan C, Forouhi N, et al. Diabetes in Europe: an update. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):206–17. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Joanna Briggs Institute . Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual: 2014 edition. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2014. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [16].American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Supplement 1):S11–61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-s011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Abduljabbar MA, Aljubeh JM, Amalraj A, Cherian MP. Incidence trends of childhood type 1 diabetes in eastern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2010;31(4):413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Habeb AM, Al-Magamsi MS, Halabi S, Eid IM, Shalaby S, Bakoush O. High incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes in Al-Madinah, North West Saudi Arabia (2004–2009) Pediatr Diab. 2011;12(8):676–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2011.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Al-Daghri NM, Al-Attas OS, Alokail MS, Alkharfy KM, Yousef M, Sabico SL, et al. Diabetes mellitus type 2 and other chronic non-communicable diseases in the central region, Saudi Arabia (Riyadh cohort 2): a decade of an epidemic. BMC Med. 2011;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Al-Herbish AS, El-Mouzan MI, Al-Salloum AA, Al-Qurachi MM, Al-Omar AA. Prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabian children and adolescents. Saudi Med J. 2008;29(9):1285–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Al-Rubeaan K. National surveillance for type 1, type 2 diabetes and prediabetes among children and adolescents: a population-based study (SAUDI-DM) J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2015;69(11):1045–51. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-205710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Alqurashi KA, Aljabri KS, Bokhari SA. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in a Saudi community. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(1):19. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.75773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Al-Baghli N, Al-Ghamdi A, Al-Turki K, Al Elq A, El-Zubaier A, Bahnassy A. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glucose levels in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia: results of a screening campaign. Singapore Med J. 2010;51(12):923. doi: 10.26719/2010.16.6.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Al-Nozha MM, Al-Maatouq MA, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Harthi SS. Diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2004;25(11):1603–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].AlRubeaan K, AlManaa HA, Khoja TA, Ahmad NA, Al-Sharqawi AH, Siddiqui K, et al. Epidemiology of abnormal glucose metabolism in a country facing its epidemic: SAUDI-DM study. J Diab. 2015;7(5):622–32. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Vlad I, Popa AR. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus: a current review. Roman J Diab Nutr Metab Dis. 2012;19(4):433–40. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dean L, McEntyre J. NCBI; 2004. The genetic landscape of diabetes [electronic resource] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cucca F, Goy JV, Kawaguchi Y, Esposito L, Merriman ME, Wilson AJ, et al. A male-female bias in type 1 diabetes and linkage to chromosome Xp in MHC HLA-DR3-positive patients. Nat Genet. 1998;19(3):301–2. doi: 10.1038/995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hackett C. Facts about the Muslim population in Europe. 2015 Pew Research Center Retrieved from Pew Research Center website: http://www pewresearch org/fact-tank/2015/11/17/5-facts-about-the-muslim-populationin-europe.

- [30].Szadkowska A, Madej A, Ziolkowska K, Szymanska M, Jeziorny K, Mianowska B. Gender and Age-Dependent effect of type 1 diabetes on obesity and altered body composition in young adults. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2015;22(1) doi: 10.5604/12321966.1141381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Alharbi N.S, Almutari R, Jones S, Al-Daghri N, Khunti K, de Lusignan S. Trends in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity in the Arabian Gulf States: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;106(2):e30–3. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Alsenany S, Al Saif A. Incidence of diabetes mellitus type 2 complications among Saudi adult patients at primary health care center. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(6):1727. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Albargawi M, Snethen J, Gannass AA, Kelber S. Perception of persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Int J Nurs Sci. 2016;3(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2016.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Alwakeel J, Sulimani R, Al-Asaad H, Al-Harbi A, Tarif N, Al-Suwaida A, et al. Diabetes complications in 1952 type 2 diabetes mellitus patients managed in a single institution. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28(4):260. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2008.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Alotaibi A, Al-Ganmi A, Gholizadeh L, Perry L. Diabetes knowledge of nurses in different countries: an integrative review. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;39:32–49. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Alotaibi A, Gholizadeh L, Al-Ganmi A, Perry L. Examining perceived and actual diabetes knowledge among nurses working in a tertiary hospital. Appl Nurs Res. 2017;35:24–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]