Changes in Perceived Stress After Yoga, Physical Therapy, and Education Interventions for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial (original) (raw)

Abstract

Objective

Perceived stress and musculoskeletal pain are common, especially in low-income populations. Studies evaluating treatments to reduce stress in patients with chronic pain are lacking. We aimed to quantify the effect of two evidence-based interventions for chronic low back pain (cLBP), yoga and physical therapy (PT), on perceived stress in adults with cLBP.

Methods

We used data from an assessor-blinded, parallel-group randomized controlled trial, which recruited predominantly low-income and racially diverse adults with cLBP. Participants (N = 320) were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of yoga, PT, or back pain education. We compared changes in the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) from baseline to 12- and 52-week follow-up among yoga and PT participants with those receiving education. Subanalyses were conducted for participants with elevated pre-intervention perceived stress (PSS-10 score ≥17). We conducted sensitivity analyses using various imputation methods to account for potential biases in our estimates due to missing data.

Results

Among 248 participants (mean age = 46.4 years, 80% nonwhite) completing all three surveys, yoga and PT showed greater reductions in PSS-10 scores compared with education at 12 weeks (mean between-group difference = −2.6, 95% confidence interval [CI] = −4.5 to −0.66, and mean between-group difference = −2.4, 95% CI = −4.4 to −0.48, respectively). This effect was stronger among participants with elevated pre-intervention perceived stress. Between-group effects had attenuated by 52 weeks. Results were similar in sensitivity analyses.

Conclusions

Yoga and PT were more effective than back pain education for reducing perceived stress among low-income adults with cLBP.

Keywords: Chronic Low Back Pain, Yoga, Physical Therapy, Stress, Underserved Populations

Introduction

Perceived stress occurs when individuals experience environmental demands that exceed their adaptive capacity [1]. Low-income and racially diverse populations are a high-risk group for perceived stress due to intersecting risk factors such as traumatic life experiences (e.g., violence, racism), work-related factors (e.g., high job demand, occupational injuries), and financial insecurity [2–5]. Perceived stress is associated with the onset and progression of many chronic conditions [6, 7], and its significant relationship with the onset and prevalence of persistent musculoskeletal pain has been described in various populations [8–10]. Low back pain is a common source of persistent musculoskeletal pain. Nearly all adults will experience at least one episode in their lifetime, and rates of chronic low back pain (cLBP) are higher in low-income populations [11, 12]. While perceived stress can increase the likelihood of acute low back pain becoming chronic [10], chronic pain also can generate ongoing stress [13]. Additionally, among adults with low-level or stable cLBP, a stressful life event may precipitate “flares” of back pain symptoms, which impact usual activities [14, 15]. While mind and body therapies contain components (e.g., meditation, aerobic exercise) that may alleviate both pain and perceived stress [16], few studies have evaluated treatments to reduce stress in patients with cLBP. Our study examined whether yoga and physical therapy (PT), two evidence-based cLBP treatments [17, 18], may reduce perceived stress in low-income, racially diverse adults with cLBP.

Yoga typically consists of physical poses, breathing exercises, and meditation. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) suggest that yoga reduces perceived stress in healthy individuals [19, 20], workers with either back pain or stress [21], and among populations known to experience chronic pain, including cancer patients [22], sedentary adults [23], and workplace employees [24]. Clinical studies of yoga on perceived stress are limited by small sample sizes, lack of randomization, nonstandardized interventions, short follow-up periods, and variations in outcome measurement [20]. Few studies have examined yoga for perceived stress among low-income populations or adults living with cLBP. One large trial of yoga for cLBP found that reductions in perceived stress midintervention did not independently mediate improvements in physical function [25], and end-of-intervention effects on stress were not published [26]. Thus, whether patients receiving yoga for cLBP also experience changes in perceived stress remains unknown.

PT is a common treatment for cLBP and typically involves stretching, strengthening, and aerobic exercise in a one-on-one setting with a physical therapist, who supports and encourages the patient [17]. Physical therapists commonly manage painful musculoskeletal conditions, but little attention has been dedicated to understanding non-pain-related stress in the pain experience [13]. While aerobic exercise, a fundamental component of PT, can reduce patients’ sensitivity to stress [27] and improve stress overall [28, 29], we are unaware of any RCTs that have examined the effect of PT on perceived stress. Given the biological links between chronic stress and pain, physical therapists have been encouraged to screen for perceived stress and to educate patients on the role of stress in pain to reduce fear-based responses [13].

To address these gaps in knowledge, we used data from the Back to Health Study, a recent large RCT demonstrating that yoga was noninferior to PT for improved pain and back-related function in low-income and racially diverse adults with cLBP [30]. We evaluated the effect of yoga and PT on perceived stress at both 12 weeks and 52 weeks. We hypothesized that yoga and PT participants would experience greater improvements in perceived stress postintervention compared with an education control group and that this improvement would be sustained over the follow-up period.

Methods

Study Design

The Back to Health Study protocol [31] and primary results [30] have been described in detail elsewhere. The original trial was registered (NCT01343927), and all study procedures were approved by the Boston University Medical Campus (BUMC) Institutional Review Board. Briefly, the current study is a secondary analysis of an assessor-blinded, parallel-group RCT of 320 participants recruited from a large academic safety-net hospital and seven affiliated federally qualified community health centers between June 2012 and November 2013. Follow-up ended in November 2014. Participants were predominantly low-income, racially diverse, English-speaking adults aged 18 to 65. Inclusion criteria included low back pain lasting ≥12 weeks and pain intensity rated ≥4 on a 0–10 numeric pain rating scale. Persons with specific causes of cLBP (e.g., spinal canal stenosis, sciatica where leg pain was greater than back pain) were excluded. All participants provided informed consent.

Participants were randomized using a computer-generated sequence in a 2:2:1 ratio to group yoga, one-on-one PT, or a back pain education book, respectively [31]. After the 12-week intervention phase, participants in the yoga and PT groups were further randomized for a 40-week maintenance phase. Participants in the yoga arm were randomized to either a weekly drop-in yoga class or home practice only; PT participants were randomized to either five “booster sessions” or home practice only. Because the maintenance phase groups were not significantly different in pain and function at 52 weeks [30], we collapsed maintenance groups for the purpose of these analyses.

Interventions

A manualized hatha yoga program [31] based on previous studies [32, 33] consisted of weekly 75-minute classes over the 12-week treatment phase. Classes focused on yoga postures complemented by relaxation and breathing exercises. Low participant–instructor ratios (<5:1) allowed instructors to provide prespecified modifications to accommodate different abilities.

A manualized, high-dose PT intervention [31] consisted of 15 hour-long sessions over the treatment phase delivered according to the treatment-based classification system [34]. Each session consisted of one-on-one work with a physical therapist and supervised aerobic exercise. Additionally, participants who scored high on the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire were given a copy of The Back Book [35], a brief resource that addresses psychosocial comorbidities that can negatively affect prognosis.

The education group received The Back Pain Helpbook [36], which has been used as a credible control arm in previous studies of back pain treatments [37, 38]. The Back Pain Helpbook comprehensively discusses cLBP and self-management strategies such as stretching, exercise, and lifestyle changes. Participants were provided a reading schedule and received check-in calls from study staff every three weeks. Newsletters were also sent to summarize each section.

Data Collection

Participants were administered the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) [1] at baseline, 12 weeks, and 52 weeks. The PSS-10 is an abbreviated version of the 14-item Perceived Stress Scale and has high validity and reliability. Participants rate the frequency with which they experienced 10 stress symptoms over the preceding 30 days on a five-point scale (0 = never, 4 = very often). Total scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater perceived stress. A cutoff of 17 for elevated perceived stress was selected because it is above all four estimates for the true population mean (13.0–16.1) derived from large studies (N = 1,143–2,387) [39–41]. This cutoff coincided with the median baseline PSS-10 score in our data set.

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, race (white, nonwhite), ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic), employment status (working, nonworking), and annual income (≤$30,000, >$30,000). Clinical characteristics included body mass index (BMI), baseline back-related pain intensity measured by an 11-point numerical scale [42], and function as assessed by the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) [43]. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8), measures of anxiety and depressive symptoms, respectively, were also reported.

Data Analysis

Baseline characteristics of the participants in each intervention group were compared using analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. If baseline differences existed (P < 0.05), these variables were adjusted for in our analyses. Our analytic sample included participants with complete data at 12 and 52 weeks. For participants who only answered nine of the PSS-10 questions, a total score was imputed using mean item substitution [44]. Adherence was defined a priori as attending at least nine yoga classes, 11 PT appointments (≥75% or ≥73% of sessions, respectively), and self-report of reading three-fourths of the assigned self-care book.

We calculated within-group PSS-10 differences from baseline to 12- and 52-week follow-up. Thus, negative values represent improvements in perceived stress. We calculated between-group differences in PSS-10 change scores at each follow-up using the education group as a reference. We performed an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to test between-group differences in 12- and 52-week changes in perceived stress after adjusting for age, gender, and baseline RMDQ score. Results were presented as mean change scores with 95% confidence intervals. We also computed Pearson correlation coefficients between baseline perceived stress and both back pain intensity and RMDQ scores. These calculations were repeated between change scores at 12 and 52 weeks.

Sensitivity analyses allowed us to estimate the effect of yoga and PT in two larger samples: participants who completed at least one survey at either 12 or 52 weeks and all 320 participants using multiple imputation. Estimates from these analyses were compared with results of the primary analysis (complete case) to assess potential bias.

Our sample included participants with low levels of stress who may have been excluded if the original study’s primary aim had been to evaluate changes in perceived stress. Thus, we repeated the above analyses separately in adult participants defined a priori as having elevated (PSS-10 ≥ 17) pre-intervention levels of perceived stress. We used published national median PSS-10 scores [39–41] to a priori establish the cutoff point.

All analyses were conducted using SAS Studio, version 3.7.

Results

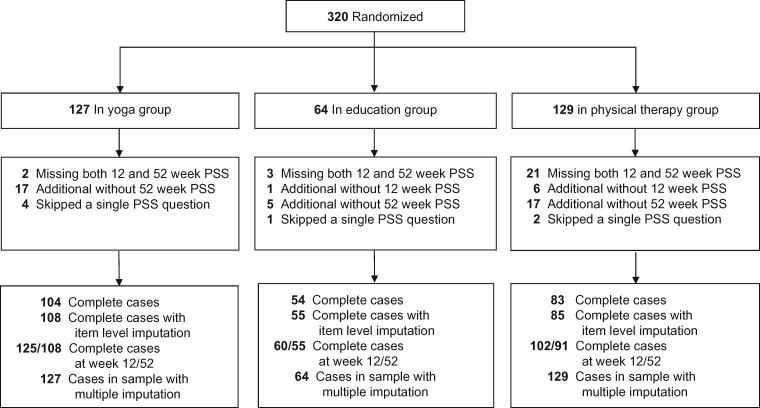

Among 248 participants with complete data, most were female (71%), middle-aged (mean age = 46.4 ± 10.4 years), nonwhite (80%), and low-income (59%) (Table 1). There were significant between-group differences in baseline RMDQ (P = 0.03) and gender (P = 0.02). Baseline PSS-10 scores (mean = 16.9 ± 6.7) did not vary significantly by treatment group. The 72 excluded participants were similar in most baseline characteristics, except that they were less likely to be white (11%) and female (40%). For the subset analysis, the entire sample (N = 320, mean PSS-10 = 17.3 ± 7.0) was split into elevated (N = 174, mean PSS-10 = 22.5 ± 4.7) and lower (N = 146, mean PSS-10 = 11.2 ± 3.7) pre-intervention perceived stress groups (Supplementary Data). The numbers of participants included in the complete case analysis and each of the sensitivity analyses are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the yoga, physical therapy, and education groups

| Characteristic | Yoga (N = 108) | Physical Therapy (N = 85) | Education (N = 55) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD), y | 46.6 (10.4) | 48.0 (10.6) | 43.8 (10.1) |

| Female, No. (%)¶ | 66 (61.1) | 67 (78.8) | 42 (76.4) |

| Race No. (%) | |||

| American Indian | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.8) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 (1.9) | 3 (3.5) | 3 (5.5) |

| Black | 60 (55.6) | 48 (56.5) | 37 (67.3) |

| White | 28 (25.9) | 14 (16.5) | 8 (14.5) |

| Other/multiple | 18 (16.7) | 19 (22.4) | 6 (10.9) |

| Hispanic, No. (%) | 18 (16.7) | 10 (11.8) | 5 (9.1) |

| Currently working, No. (%) | 48 (44.4) | 33 (38.8) | 27 (49.1) |

| Annual income ≤$30,000, No. (%) | 67 (62.0) | 47 (55.3) | 33 (60.0) |

| Body mass index (SD), kg/m2 | 30.6 (6.8) | 32.7 (7.7) | 32.2 (7.7) |

| Perceived Stress Scale 10-item (SD) | 17.0 (7.1) | 16.9 (6.5) | 16.7 (6.5) |

| Back pain intensity (SD)* | 7.1 (1.5) | 7.3 (1.5) | 7.0 (1.4) |

| Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (SD)¶† | 13.7 (5.5) | 15.7 (4.9) | 15.1 (4.9) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (SD)‡ | 6.9 (6.0) | 6.7 (5.9) | 7.0 (5.4) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire 8-item (SD)§ | 7.9 (6.1) | 8.2 (6.0) | 8.1 (5.3) |

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Adherence in the treatment and maintenance phases has been described previously [30]. Of the participants with complete data, the median treatment phase yoga and PT attendance (interquartile range) was eight (4–11) classes and 10.5 (6–13) appointments, respectively. Based on an a priori definition of adherence, the yoga and PT groups both had 49% adherence, while education was at 44%.

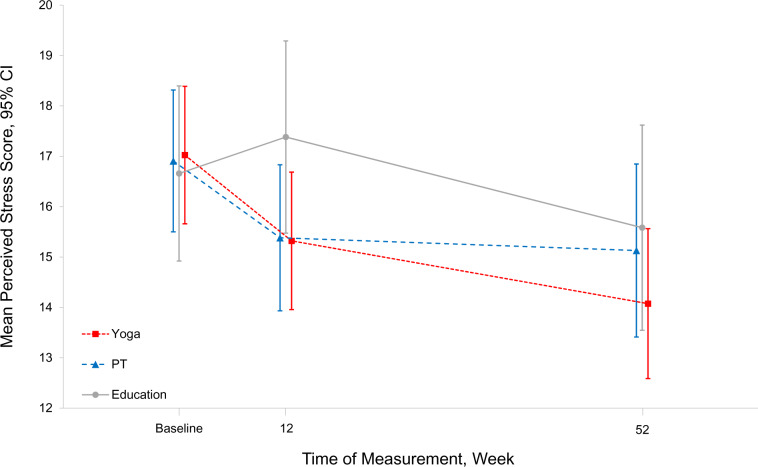

At 12 weeks, participants in the yoga and PT treatment groups, but not the education group, reported significant reductions in perceived stress (Figure 2, Table 2). After adjusting for age, gender, and baseline RMDQ score, participants in these groups improved significantly relative to those receiving education (yoga: mean between-group difference = −2.6, 95% confidence interval [CI] = −4.5 to −0.66; PT: mean between-group difference = −2.4, 95% CI = −4.4 to −0.48). Among participants with elevated pre-intervention stress, we observed larger between-group differences for both yoga and PT compared with education (yoga: mean between-group difference = −3.4, 95% CI = −6.0 to −0.77; PT: mean between-group difference = −3.2, 95% CI = −6.0 to −0.54).

Figure 2.

Changes in perceived stress scale scores for 248 participants with complete data at baseline, 12 weeks, and 52 weeks.

Table 2.

Changes in perceived stress scale scores for 248 participants with complete data at baseline, 12 weeks, and 52 weeks

| Mean Within-Group Change | Mean Between-Group Difference* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Baseline | 12 Weeks | 52 Weeks | 12 Weeks | 52 Weeks | 12 Weeks | 52 Weeks |

| All participants | |||||||

| Education (N = 55) | 16.7 ± 6.5 | 17.4 ± 7.2 | 15.6 ± 7.6 | 0.72 (−0.84 to 2.3) | −1.1 (−3.0 to 0.89) | Reference | Reference |

| Yoga (N = 108) | 17.0 ± 7.1 | 15.3 ± 7.1 | 14.1 ± 7.7 | −1.7 (−2.8 to −0.63) | −2.9 (−4.2 to −1.7) | −2.6 (−4.4 to –0.66) | −2.1 (−4.5 to 0.35) |

| PT (N = 85) | 16.9 ± 6.5 | 15.4 ± 6.7 | 15.1 ± 8.0 | −1.5 (−2.7 to −0.30) | −1.8 (−3.4 to −0.15) | −2.4 (−4.4 to –0.48) | −0.93 (−3.4 to 1.5) |

| Baseline PSS ≥17 | |||||||

| Education (N = 28) | 21.8 ± 4.1 | 21.7 ± 6.1 | 18.9 ± 7.2 | −0.04 (−2.5 to 2.4) | −2.8 (−6.0 to 0.35) | Reference | Reference |

| Yoga (N = 56) | 22.7 ± 4.1 | 19.0 ± 6.6 | 17.2 ± 7.6 | −3.7 (−5.1 to −2.3) | −5.5 (−7.2 to −3.8) | −3.4 (–6.0 to −0.77) | −2.7 (−6.1 to 0.62) |

| PT (N = 43) | 22.0 ± 4.8 | 18.6 ± 6.2 | 18.3 ± 7.4 | −3.4 (−5.0 to −1.7) | −3.7 (−6.0 to −1.5) | −3.2 (–6.0 to −0.54) | −1.5 (−5.0 to 1.9) |

| Baseline PSS <17 | |||||||

| Education (N = 27) | 11.4 ± 3.7 | 12.9 ± 5.2 | 12.1 ± 6.6 | 1.5 (−0.55 to 3.6) | 0.73 (−1.6 to 3.0) | Reference | Reference |

| Yoga (N = 52) | 10.9 ± 3.6 | 11.3 ± 5.2 | 10.7 ± 6.3 | 0.45 (−1.1 to 2.0) | −0.18 (−1.9 to 1.6) | −1.2 (−3.9 to 1.4) | −0.05 (−3.3 to 3.2) |

| PT (N = 42) | 11.7 ± 3.1 | 12.1 ± 5.6 | 11.9 ± 7.3 | 0.34 (−1.3 to 2.0) | 0.21 (−2.1 to 2.5) | −1.4 (−4.1 to 1.3) | −0.34 (−3.6 to 2.9) |

At 52 weeks, we observed within-group improvements among all three groups, with statistically significant improvements in perceived stress for yoga and PT only (Figure 2, Table 2). The effects of yoga and PT relative to education at 52 weeks were attenuated and no longer statistically significant (mean between-group difference = −2.1, 95% CI = −4.45 to 0.35, and mean between-group difference = −0.93, 95% CI = −3.4 to 1.5, respectively). Similar 52-week outcomes were observed in those with elevated pre-intervention PSS-10 scores.

Sensitivity analyses showed similar results at 12 and 52 weeks (Figure 1; Supplementary Data). The magnitude of the effect of yoga and PT compared with education at 12 weeks was partially attenuated by half of a point in analyses using multiple imputations for missing data but remained significant.

Perceived stress exhibited a nonsignificant positive relationship with reported back pain intensity (r = 0.12, P = 0.06) and a weak negative relationship with function (r = −0.17, P = 0.007) at baseline. Slightly stronger relationships were also observed between changes in stress and changes in pain and function at 12 weeks (r = 0.32 and −0.29, respectively, P < 0.001) and 52 weeks (r = 0.36 and –0.27, respectively, P < 0.001).

Discussion

In a large sample of predominantly low-income adults with cLBP, we observed a larger reduction in perceived stress among those randomized to yoga or PT interventions, compared with a back pain education control group at 12 weeks. The effect of yoga and PT on perceived stress was larger among adults with elevated pre-intervention perceived stress. While improvements in stress were maintained over the 52-week period, the effect of yoga and PT compared with education had attenuated by 52 weeks and was no longer statistically significant. Sensitivity analyses using several imputation methods for missing data observed similar effects of yoga and PT at 12 and 52 weeks.

Our findings are consistent with clinical trials indicating modest to moderate improvements in perceived stress from yoga. Of eight small RCTs (N = 59–100) evaluating the effect of similar yoga interventions using the PSS-10, seven detected significant improvements ranging from −2.7 to −7.8 points in populations including workers with either back pain or stress [21], pregnant women [45, 46], cancer patients [47], health profession students [48], and others [23, 49]. The nonsignificant RCT found only a small reduction (–1.5 points) in perceived stress among 100 nurses [50]. One larger study (N = 239) of yoga in a high-stress workplace population found a large reduction in perceived stress after 12 weeks (−8.2 points) [24]. The smaller effect observed in our study may be in part due to our lower mean baseline PSS-10 score (16.9 vs 24.9). Indeed, when we restricted analyses to 56 participants with elevated perceived stress (mean baseline PSS-10 of 22.7), we observed a larger reduction in PSS-10 at 12 weeks and 52 weeks of −3.7 and −5.5, respectively. Low adherence rates in yoga and PT interventions may have also contributed to modest treatment effects observed in both groups.

Although no studies, to our knowledge, have assessed PT’s effect on perceived stress, the effect of aerobic exercise, a major component of our PT intervention, is associated with lower stress levels [29, 51]. However, fewer studies have evaluated aerobic exercise as a stress reducer in a chronic pain population. Individuals with pain may avoid exercise because it exacerbates pain or they fear re-injury [52]. Stress itself may prevent people from being physically active [53]. Structured supportive interventions are needed to overcome stress- or pain-related barriers for individuals to start or progress through an exercise routine. Among studies with smaller samples (N = 50–151), the effectiveness of aerobic exercise interventions for reducing perceived stress has not been demonstrated [54–56].

One potential mechanism by which yoga or PT may improve perceived stress in adults with cLBP is through reducing pain and improving function. However, we found that improvements in pain and function were only weakly correlated with improvements in perceived stress, suggesting other aspects of these treatments may contribute to reducing perceived stress. Yoga has several components that are thought to reduce stress, such as meditation, rhythmic breathing, and stretching techniques, as well as social support [57]. Our PT intervention included screening for fear-avoidance beliefs, a treatment-based classification algorithm, and one-on-one education and support from the physical therapist. Studies have shown that a strong patient–therapist relationship, defined by a sense of collaboration, warmth, and support, is associated with reduced pain and disability and higher patient satisfaction [58, 59]. These aspects of PT may also help account for the improvements in perceived stress at 12 weeks, as the provider–patient relationship may provide unique opportunities to tailor care and reassure the participant, for example, addressing fear-avoidance beliefs that can perpetuate stress [52].

This study had several limitations. The complete case analysis did not maintain randomization. Given that this was a secondary analysis, the yoga and PT interventions tested in this trial were designed to target cLBP, not perceived stress. Modifying these interventions may enhance their effect on perceived stress, for example, a greater focus on mindfulness, meditation, or coping skills. As minimum pre-intervention levels of perceived stress were not required at study entry, participants with very low pre-intervention PSS-10 may have had less opportunity to improve due to floor effects. The PSS-10 does not ask participants to identify the source(s) of their stress (e.g., a traumatic life experience, work-related stress, or stress from their chronic pain experience). Therefore, we were unable to assess whether distinct sources of stress modify the effects of yoga or PT on stress outcomes. Finally, this trial did not include objective assessments of chronic stress biomarkers (e.g., salivary cortisol) that might elucidate potential psychoneuroendocrine mechanisms underlying yoga- and PT-related health benefits.

Study strengths include use of a validated measure of perceived stress, multiple time points of measurement over 52 weeks of follow-up, and a socioeconomically diverse sample that is particularly vulnerable to stress and cLBP [11, 60]. We also conducted sensitivity analyses using various imputation methods due to missing data, which obtained similar results.

Our findings may have public health and clinical implications. Back pain and mental health conditions are leading causes of disability worldwide [61]. Recent findings from the National Health Interview Survey show an exponential increase in the use of yoga in the United States from 2002 to 2017, with many Americans reporting yoga to be helpful for pain and mental health conditions [62]. As yoga can be done in a group with fairly minimal equipment, it would conceivably be a fairly low-cost option for patients with co-occurring stress and cLBP in low-income areas. However, further research is needed to determine whether our results are generalizable to community yoga, which is nonmanualized and often has higher participant–instructor ratios. Additionally, primary care providers, physical therapists, and other clinicians who manage cLBP may also want to ask their patients about perceived stress. Patients may be more comfortable talking about perceived stress than often-stigmatized mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression [63].

In conclusion, yoga and PT were effective for reducing perceived stress compared with an education control in a predominantly low-income, racially diverse cLBP population, especially among participants with high perceived stress pre-intervention. Yoga and PT are often offered in the community. Improving access to these treatment options in underserved communities may improve the management of stress in these settings.

Author Contributions

Mr. Berlowitz and Drs. Saper and Roseen had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Berlowitz, Sherman, Saper, Roseen. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Berlowitz, Hall, Joyce, Fredman, Sherman, Saper, Roseen. Drafting of the manuscript: Berlowitz, Roseen. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Berlowitz, Hall, Joyce, Fredman, Sherman, Saper, Roseen. Statistical analysis: Berlowitz, Roseen. Obtained funding: N/A. Administrative, technical, or material support: Berlowitz, Saper, Roseen. Study supervision: Saper, Roseen.

Supplementary Material

pnaa150_Supplementary_Appendices

Contributor Information

Jonathan Berlowitz, Department of Family Medicine, Boston Medical Center and Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts.

Daniel L Hall, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; Health Policy Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Christopher Joyce, Department of Rehabilitation Science, Massachusetts General Hospital Institute of Health Professions, Boston, Massachusetts; School of Physical Therapy, Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Worcester, Massachusetts.

Lisa Fredman, Department of Epidemiology, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts.

Karen J Sherman, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, Washington; Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Robert B Saper, Department of Family Medicine, Boston Medical Center and Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts.

Eric J Roseen, Department of Family Medicine, Boston Medical Center and Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; Department of Rehabilitation Science, Massachusetts General Hospital Institute of Health Professions, Boston, Massachusetts.

Funding sources: The Back to Health Study (5R01-AT005956) was funded by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). Funding from the NCCIH also supported the work of Drs. Hall (K23AT010157-01) and Roseen (1F32AT009272, K23AT010487-01). Mr. Berlowitz received funding through the Boston University Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program to support his work on this project.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no financial or other relationships that would constitute a conflict of interest.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01343927.

References

- 1.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R.. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24(4):385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conyersm FG, Langevin HM, Badger GJ, Mehta DH.. Identifying stress landscapes in Boston neighborhoods. Glob Adv Health Med 2018;7:216495611880305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steptoe A, Feldman PJ.. Neighborhood problems as sources of chronic stress: Development of a measure of neighborhood problems, and associations with socioeconomic status and health. Ann Behav Med 2001;23(3):177–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stronks K, van de Mheen H, Looman CW, Mackenbach JP.. The importance of psychosocial stressors for socio-economic inequalities in perceived health. Soc Sci Med 1998;46(4–5):611–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychological Association. Stress and Health Disparities: Contexts, Mechanisms, and Interventions Among Racial/Ethnic Minority and Low-Socioeconomic Status Populations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2017.

- 6.Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel SD.. Stress and health: Psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005;1(1):607–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE.. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA 2007;298(14):1685–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osteras B, Sigmundsson H, Haga M.. Perceived stress and musculoskeletal pain are prevalent and significantly associated in adolescents: An epidemiological cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2015;15(1):1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuboi Y, Ueda Y, Naruse F, Ono R.. The association between perceived stress and low back pain among eldercare workers in Japan. J Occup Environ Med 2017;59(8):765–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buscemi V, Chang WJ, Liston MB, McAuley JH, Schabrun SM.. The role of perceived stress and life stressors in the development of chronic musculoskeletal pain disorders: A systematic review. J Pain 2019;20(10):1127–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang H, Haldeman S.. Behavior-related factors associated with low back pain in the US adult population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018;43(1):28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018;391(10137):2356–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hannibal KE, Bishop MD.. Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: A psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Phys Ther 2014;94(12):1816–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costa N, Ferreira ML, Setchell J, et al. A definition of “flare” in low back pain: A multiphase process involving perspectives of individuals with low back pain and expert consensus. J Pain 2019;20(11):1267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa N, Hodges PW, Ferreira ML, Makovey J, Setchell J.. What triggers an LBP Flare? A content analysis of individuals’ perspectives. Pain Med 2020;21(1):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EM, et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174(3):357–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Tomlinson G.. Systematic review: Strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med 2005;142(9):776–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wieland LS, Skoetz N, Pilkington K, Vempati R, D'Adamo CR, Berman BM.. Yoga treatment for chronic non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;1:CD010671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chong CS, Tsunaka M, Tsang HW, Chan EP, Cheung WM.. Effects of yoga on stress management in healthy adults: A systematic review. Altern Ther Health Med 2011;17(1):32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma M. Yoga as an alternative and complementary approach for stress management: A systematic review. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 2014;19(1):59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartfiel N, Burton C, Rycroft-Malone J, et al. Yoga for reducing perceived stress and back pain at work. Occup Med (Lond) 2012;62(8):606–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin KY, Hu YT, Chang KJ, Lin HF, Tsauo JY.. Effects of yoga on psychological health, quality of life, and physical health of patients with cancer: A meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011;2011:659876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hewett ZL, Pumpa KL, Smith CA, Fahey PP, Cheema BS.. Effect of a 16-week Bikram yoga program on perceived stress, self-efficacy and health-related quality of life in stressed and sedentary adults: A randomised controlled trial. J Sci Med Sport 2018;21(4):352–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolever RQ, Bobinet KJ, McCabe K, et al. Effective and viable mind-body stress reduction in the workplace: A randomized controlled trial. J Occup Health Psychol 2012;17(2):246–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherman KJ, Wellman RD, Cook AJ, Cherkin DC, Ceballos RM.. Mediators of yoga and stretching for chronic low back pain. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:130818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Wellman RD, Cook AJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing yoga, stretching, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med 2011;171(22):2019–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salmon P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clin Psychol Rev 2001;21(1):33–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsatsoulis A, Fountoulakis S.. The protective role of exercise on stress system dysregulation and comorbidities. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1083(1):196–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerber M, Puhse U.. Review article: Do exercise and fitness protect against stress-induced health complaints? A review of the literature. Scand J Public Health 2009;37(8):801–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saper RB, Lemaster C, Delitto A, et al. Yoga, physical therapy, or education for chronic low back pain: A randomized noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med 2017;167(2):85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saper RB, Sherman KJ, Delitto A, et al. Yoga vs. physical therapy vs. education for chronic low back pain in predominantly minority populations: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15(1):15–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saper RB, Sherman KJ, Cullum-Dugan D, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Culpepper L.. Yoga for chronic low back pain in a predominantly minority population: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Altern Ther Health Med 2009;15(6):18–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saper RB, Boah AR, Keosaian J, Cerrada C, Weinberg J, Sherman KJ.. Comparing once- versus twice-weekly yoga classes for chronic low back pain in predominantly low income minorities: A randomized dosing trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:658030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fritz JM, Cleland JA, Childs JD.. Subgrouping patients with low back pain: Evolution of a classification approach to physical therapy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2007;37(6):290–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roland M, WG K, Moffett K, Burton K, Main C, Cantrell T.. The Back Book. Norwich, UK: The Stationary Office; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore JL, Von Korff M, Gonzalez VM, Laurent DD.. The Back Pain Helpbook. New York: Perseus Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, Miglioretti DL, Deyo RA.. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2005;143(12):849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cherkin DC, Eisenberg D, Sherman KJ, et al. Randomized trial comparing traditional Chinese medical acupuncture, therapeutic massage, and self-care education for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med 2001;161(8):1081–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D.. Who’s stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 20091. J Appl Soc Psychol 2012;42(6):1320–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perera MJ, Brintz CE, Birnbaum-Weitzman O, et al. Factor structure of the Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS) across English and Spanish language responders in the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychol Assess 2017;29(3):320–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen S. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, eds. The Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology the Social Psychology of Health. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1988:31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korff Jensen VM, Karoly MP.. P. Assessing global pain severity by self-report in clinical and health services research. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(24):3140–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, Singer DE, Chapin A, Keller RB.. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20(17):1899–908; discussion 909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newman DA. Missing data: Five practical guidelines. Organ Res Methods 2014;17(4):372–411. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ganpat TS, Kurpad A, Maskar R, et al. Yoga for high-risk pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2013;3(3):341–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Satyapriya M, Nagendra HR, Nagarathna R, Padmalatha V.. Effect of integrated yoga on stress and heart rate variability in pregnant women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;104(3):218–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vadiraja HS, Rao RM, Nagarathna R, et al. Effects of yoga in managing fatigue in breast cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Indian J Palliat Care 2017;23(3):247–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharma VK, Trakroo M, Subramaniam V, Rajajeyakumar M, Bhavanani AB, Sahai A.. Effect of fast and slow pranayama on perceived stress and cardiovascular parameters in young health-care students. Int J Yoga 2013;6(2):104–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amaravathi E, Ramarao NH, Raghuram N, Pradhan B.. Yoga-based postoperative cardiac rehabilitation program for improving quality of life and stress levels: Fifth-year follow-up through a randomized controlled trial. Int J Yoga 2018;11(1):44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mathad MD, Pradhan B, Sasidharan RK.. Effect of yoga on psychological functioning of nursing students: A randomized wait list control trial. J Clin Diagn Res 2017;11(5):KC01–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ng DM, Jeffery RW.. Relationships between perceived stress and health behaviors in a sample of working adults. Health Psychol 2003;22(6):638–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, Bentley G.. Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception–I. Behav Res Ther 1983;21(4):401–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Sinha R.. The effects of stress on physical activity and exercise. Sports Med 2014;44(1):81–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jazaieri H, Goldin PR, Werner K, Ziv M, Gross JJ.. A randomized trial of MBSR versus aerobic exercise for social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychol 2012;68(7):715–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daley AJ, Grimmett C, Roberts L, et al. The effects of exercise upon symptoms and quality of life in patients diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome: A randomised controlled trial. Int J Sports Med 2008;29(09):778–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cadmus LA, Salovey P, Yu H, Chung G, Kasl S, Irwin ML.. Exercise and quality of life during and after treatment for breast cancer: Results of two randomized controlled trials. Psychooncology 2009;18(4):343–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kinser PA, Goehler LE, Taylor AG.. How might yoga help depression? A neurobiological perspective. Explore (NY) 2012;8(2):118–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Latimer J, Adams RD.. The therapeutic alliance between clinicians and patients predicts outcome in chronic low back pain. Phys Ther 2013;93(4):470–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, Latimer J, Ferreira ML.. The influence of the therapist-patient relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: A systematic review. Phys Ther 2010;90(8):1099–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Myers HF. Ethnicity- and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: An integrative review and conceptual model. J Behav Med 2009;32(1):9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388(10053):1545–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang CC, Li K, Choudhury A, Gaylord S.. Trends in yoga, Tai Chi, and Qigong use among US adults, 2002-2017. Am J Public Health 2019;109(5):755–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Office of the Surgeon General, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institute of Mental Health. Culture counts: the influence of culture and society on mental health. In: Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2001:23–49. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44249/ (accessed May 2, 2020). [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

pnaa150_Supplementary_Appendices