Secondary Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial of Yoga for Veterans with Chronic Low-Back Pain (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2022 Mar 30.

Published in final edited form as: Int J Yoga Therap. 2020 Jan 1;30(1):69–76. doi: 10.17761/2020-D-19-00036

Abstract

Chronic low-back pain (cLBP) is a prevalent condition, and rates are higher among military veterans. cLBP is a persistent condition, and treatment options have either modest effects or a significant risk of side-effects, which has led to recent efforts to explore mind-body intervention options and reduce opioid medication use. Prior studies of yoga for cLBP in community samples, and the main results of a recent trial with military veterans, indicate that yoga can reduce back-related disability and pain intensity. Secondary outcomes from the trial of yoga with military veterans are presented here. In the study, 150 military veterans (Veterans Administration patients) with cLBP were randomized to either yoga or a delayed-treatment group receiving usual care between 2013 and 2015. Assessments occurred at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Intent-to-treat analyses were conducted. Yoga classes lasting 60 minutes each were offered twice weekly for 12 weeks. Yoga sessions consisted of physical postures, movement, focused attention, and breathing techniques. Home practice guided by a manual was strongly recommended. The primary outcome measure was Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire scores after 12 weeks. Secondary outcomes included pain intensity, pain interference, depression, fatigue, quality of life, self-efficacy, and medication usage. Yoga participants improved more than delayed-treatment participants on pain interference, fatigue, quality of life, and self-efficacy at 12 weeks and/or 6 months. Yoga participants had greater improvements across a number of important secondary health outcomes compared to controls. Benefits emerged despite some veterans facing challenges with attending yoga sessions in person. The findings support wider implementation of yoga programs for veterans, with attention to increasing accessibility of yoga programs in this population.

Keywords: chronic low-back pain, yoga, veterans, complementary and integrative health

Background

Chronic low-back pain (cLBP), defined as low-back pain with a duration of 12 weeks or longer,1 afflicts 70% of all people during their lifetimes.2 Military veterans3,4 have higher rates of chronic pain than the general population, and the lower back was the most frequently reported location of chronic pain in a 2009 study.5 Pain is only one aspect of the symptoms and impairment experienced by those with cLBP People with cLBP also commonly report increases in disability6 and psychological symptoms7,8 as well as overall reductions in health-related quality of life (HRQOL).9,10 cLBP is also a costly condition, exemplified by U.S. statistics showing that cLBP is the second most frequently cited reason for physician visits.11 Billions of dollars are spent annually to treat cLBP, and cLBP is the leading cause of lost productivity in the workforce.12

In the past, guidelines for treating cLBP recommended initially providing self-care information13 followed by medications as needed.13,14 However, the widespread use of opioid medications to treat cLBP has resulted in addiction, overdose deaths, and other consequences,15,16 leading to strong interest in nonpharmacological treatments for cLBP.17,18 A 2017 review19 concluded that integrative health approaches such as yoga produce benefits similar to other conventional nonpharmacological treatments. That study also included clinical guidelines and recommended the use of both integrative and conventional nonpharmacological treatments, along with self-care, as the first course of treatment for cLBP.19

In two large randomized controlled trials (RCT) of yoga for cLBP published in 2011, yoga was found to reduce disability, pain, and/or medication use. However, these RCT samples20,21 were 65%–70% female, recruited in community settings, and did not report military veteran status or data on rates of psychological disorders and substance use. These factors are important because almost 90% of U.S. veterans are male, and Veterans Administration (VA) patients are more likely than the general population to be disabled, have lower incomes,22 and have elevated rates of mental health conditions.23 Given the characteristics of prior study participants,20,21 the generalizability of those results to VA patients or U.S. military veterans as a whole was unclear. Only small nonrandomized preliminary studies had been conducted with veterans.24,25 Therefore, the effectiveness of a yoga intervention for treating cLBP in VA patients was assessed in a single-site RCT. The study methods26 and main results27 have been published previously and indicated that yoga participants had significantly greater decreases in back-related disability and pain severity than comparison group participants at follow-up assessments. The objective of the current study was to present the results of additional secondary outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

A previous publication details the study design and methods.26 From 2013–2014, 150 VA patients consented and were enrolled and randomized to either the yoga intervention or to a delayed-treatment (DT) comparison group. Yoga intervention participants were asked to begin the 12-week yoga program immediately after randomization. The DT comparison participants received ongoing usual care for 6 months and were then offered the same 12-week yoga intervention. Outcomes were assessed at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months. The study and interventions were conducted at a large VA medical center.

The primary recruitment method was referral by VA clinicians from clinics, including primary care, physical medicine and rehabilitation, psychology, and pain medicine. Additionally, fliers were posted and distributed at the medical center.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were verbally reviewed with veterans inquiring about study participation. Those still interested were scheduled to attend a screening examination with study clinicians who applied inclusion and exclusion criteria. The criteria have been published previously26 and are included in Supplementary Table 1.

Participants were recruited and randomized in six cohorts. Participants attended a group baseline assessment; after completing the assessment, the study coordinator randomly assigned them to an intervention group at a 1:1 ratio via a computer program that used 10-participant blocks to facilitate balanced assignment.

Interventions

Before, during, and after the intervention period, all participants continued to receive usual care. However, participants were asked to avoid changing treatments for their cLBP during the 6-month study period unless deemed medically necessary by their medical providers. Usual care for cLBP in study participants was individualized and thus varied, but typically comprised nonprescription and prescription pain medications, physical therapy, spinal manipulation, exercise, and other self-help treatments. Participants assigned to the DT group were asked to not practice yoga until their 6-month assessment was completed.

The yoga intervention consisted of two 60-minute yoga sessions per week for 12 consecutive weeks. Yoga sessions were led by a yoga instructor with more than 7 years of teaching experience and experience teaching yoga to people with cLBP. The intervention can be described as Hatha Yoga of mild to moderate intensity, consisting primarily of yoga postures, movement sequences, and breathing techniques. Focused attention and brief periods of meditation were also included. The interventions and postures were designed by physicians and yoga experts to be safe for persons with cLBP and to accommodate beginners. The intervention was also designed to be adaptable for a variety of functional abilities and rates of progression over the 24 sessions. An instructor manual was created to guide sessions and improve standardization. Yoga participants received a home practice manual, and 15–20 minutes of home practice was recommended on days without formal yoga sessions. The home manual included a selection of basic postures from the class sessions and emphasized safety. Participants could consult with the instructor about any home practice issues. More detail on the intervention has been published elsewhere.26

The importance of attendance at the yoga sessions and regular home practice of yoga were emphasized at the baseline assessment and reinforced by the yoga instructor during sessions. Consistent with resources provided to many VA patients for travel to clinical care appointments, participants received 5peryogasessionattendedtooffsettravelcostsandencourageattendance.Studystaffcontactedparticipantsiftheymissedmorethanoneyogasessionwithoutexplanation.Allparticipantswerecontactedbystudystaffmonthlytoremindthemoftheirnextassessmentwindow.Reminderlettersandphonecallswereprovideddirectlyprecedingassessments.Participantswerecompensated5 per yoga session attended to offset travel costs and encourage attendance. Study staff contacted participants if they missed more than one yoga session without explanation. All participants were contacted by study staff monthly to remind them of their next assessment window. Reminder letters and phone calls were provided directly preceding assessments. Participants were compensated 5peryogasessionattendedtooffsettravelcostsandencourageattendance.Studystaffcontactedparticipantsiftheymissedmorethanoneyogasessionwithoutexplanation.Allparticipantswerecontactedbystudystaffmonthlytoremindthemoftheirnextassessmentwindow.Reminderlettersandphonecallswereprovideddirectlyprecedingassessments.Participantswerecompensated30 for completing each assessment.

Measures

Data were collected via self-report questionnaires and VA medical records. Participants spent 30–45 minutes completing self-report questionnaires at each of the four assessments (baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months). Sociodemographic characteristics were assessed with a brief self-report questionnaire. Medical record data were accessed to apply enrollment criteria. The primary outcome was change over time on the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) score.28 The main results for the primary outcome (RMDQ), pain severity (measured by the Brief Pain Inventory [BPI]), intervention attendance, adverse events, and pain medication use have been reported previously.27

For the secondary outcomes reported here, the short version of the BPI was used to assess pain interference.29 This 13-item measure has been validated with low-back pain patients.30 The Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) was used to assess the impact and severity of fatigue.31,32 Depressed mood was assessed using the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale (CES-D 10).33,34 Physical and mental aspects of HRQOL were assessed with the Short-Form 12 (SF-12),35 and global HRQOL was assessed with the EuroQol (EQ-5D),36,37 which has 5 questions and provides a single QOL summary score that can be used to calculate quality-adjusted life years. Anxiety was measured with the Brief Anxiety Inventory (BAI),38 which has well-established reliability and validity.39 Self-efficacy for controlling cLBP was measured using items developed by Lorig40 in mixed chronic diseases and adapted to be specific to cLBP. Sleep quality was measured with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).41 This 9-item measure provides an overall sleep quality score, with lower scores indicating better sleep.

A number of other secondary outcomes were collected for the purpose of exploring the mechanisms by which yoga improves back pain and reduces disability. These physiological variables, such as grip strength, flexibility, and core strength, will be reported in a separate manuscript.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using an intent-to-treat approach and R Statistical Software. For secondary outcomes including pain interference, fatigue, HRQOL, depression, anxiety, sleep quality, and self-efficacy, the hypotheses tested were that participants randomized to yoga would have significantly greater improvements than DT comparison participants after 12 weeks and 6 months. Linear mixed-effects modeling was used to assess changes in secondary outcomes longitudinally. The main effect of group and time (coded as a categorical variable for baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months) and a group-by-time interaction were included in the model. Linear modeling allowed for the inclusion of all data points collected from all 150 subjects. Missing data were not replaced otherwise.

Baseline characteristics were included as a covariate in the multivariable mixed-effects model if a variable was significantly associated with the outcome or significantly different between the two study groups. Insignificant covariates were removed from the multivariable model using backward selection, and only covariates with p < 0.100 were included in the final model. The significance of both random intercept and random slope were assessed using the likelihood ratio test.

Results

Participant flow is depicted in Supplementary Figure 1. Of the 152 assessed and randomized at baseline, 2 participants later requested withdrawal of participation and all data. Thus, 75 participants were randomized to each arm of the study. Attrition at follow-up assessments was about 20%, 20%, and 27.3% at the 6-week, 12-week, and 6-month assessments, respectively. However, intent-to-treat analyses using linear mixed models allowed for data from all 150 subjects to be included even if only a baseline score was provided.

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Supplementary Table 2. All participants were U.S. military veterans eligible for care in the VA Healthcare System. Participants had a mean age of 53 years and were 74% male and 49% non-Hispanic White. Most had attended college; 66% were single, divorced, separated, or widowed; 21% were unemployed; 18% had been homeless in the last 5 years; and 20% were being treated with opioid pain medication at baseline.

As previously reported in the main results manuscript, yoga participants had significantly greater decreases in the primary outcome, back-related disability, at 6 months but not at 12 weeks. Pain severity decreased significantly more among yoga participants at all three assessments.27 Opioid pain medication use decreased significantly for the study sample as whole but did not significantly differ by intervention group.

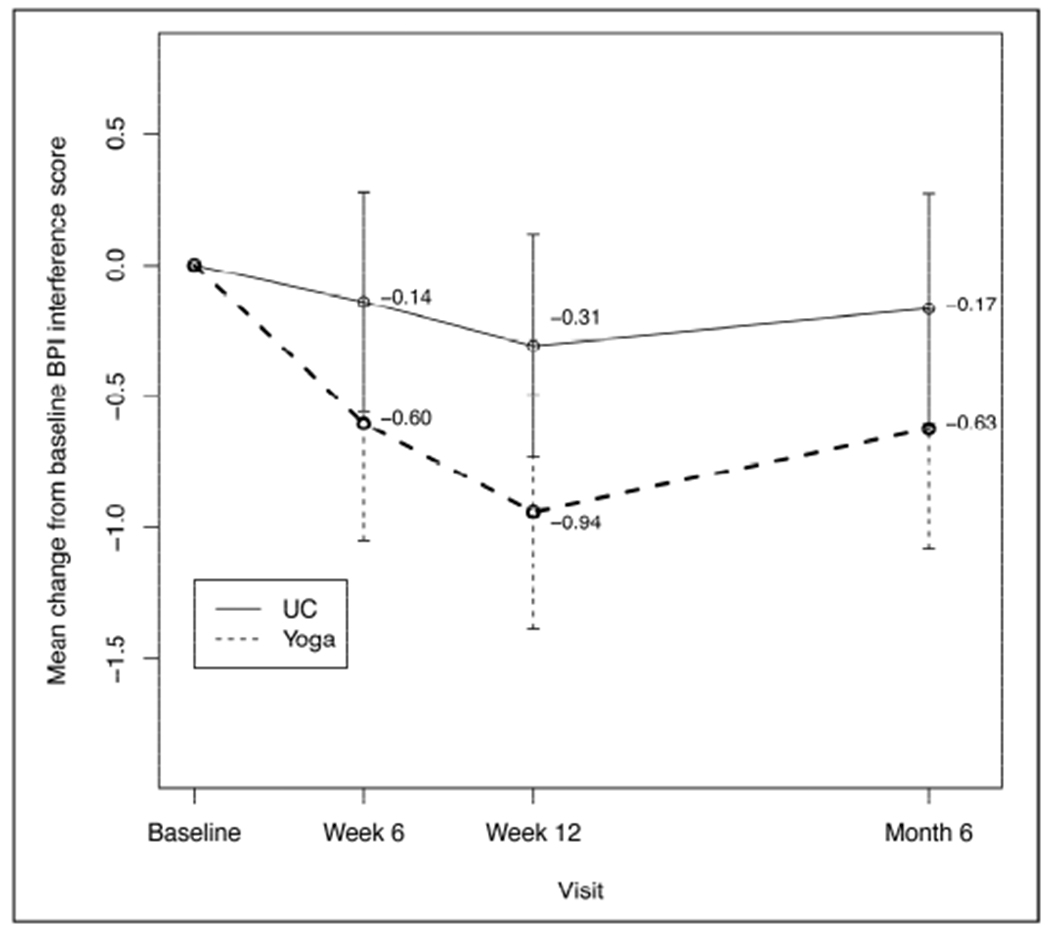

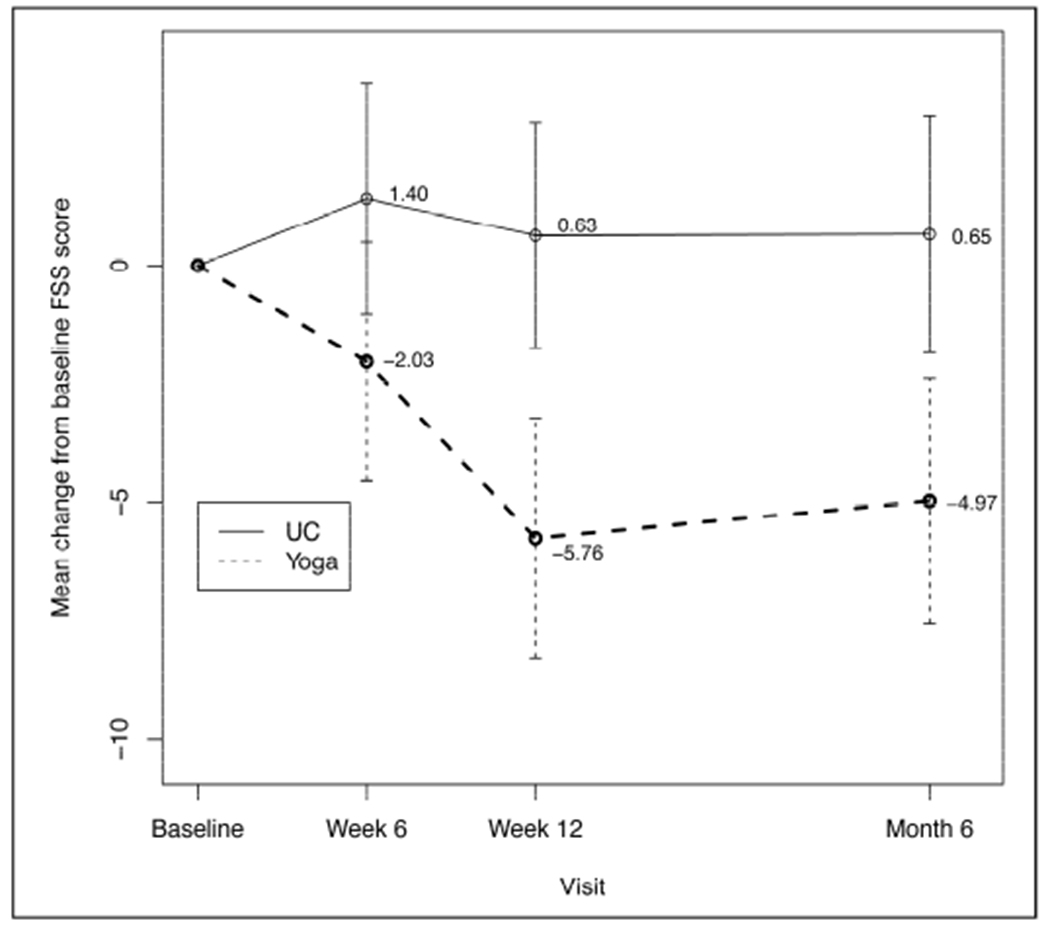

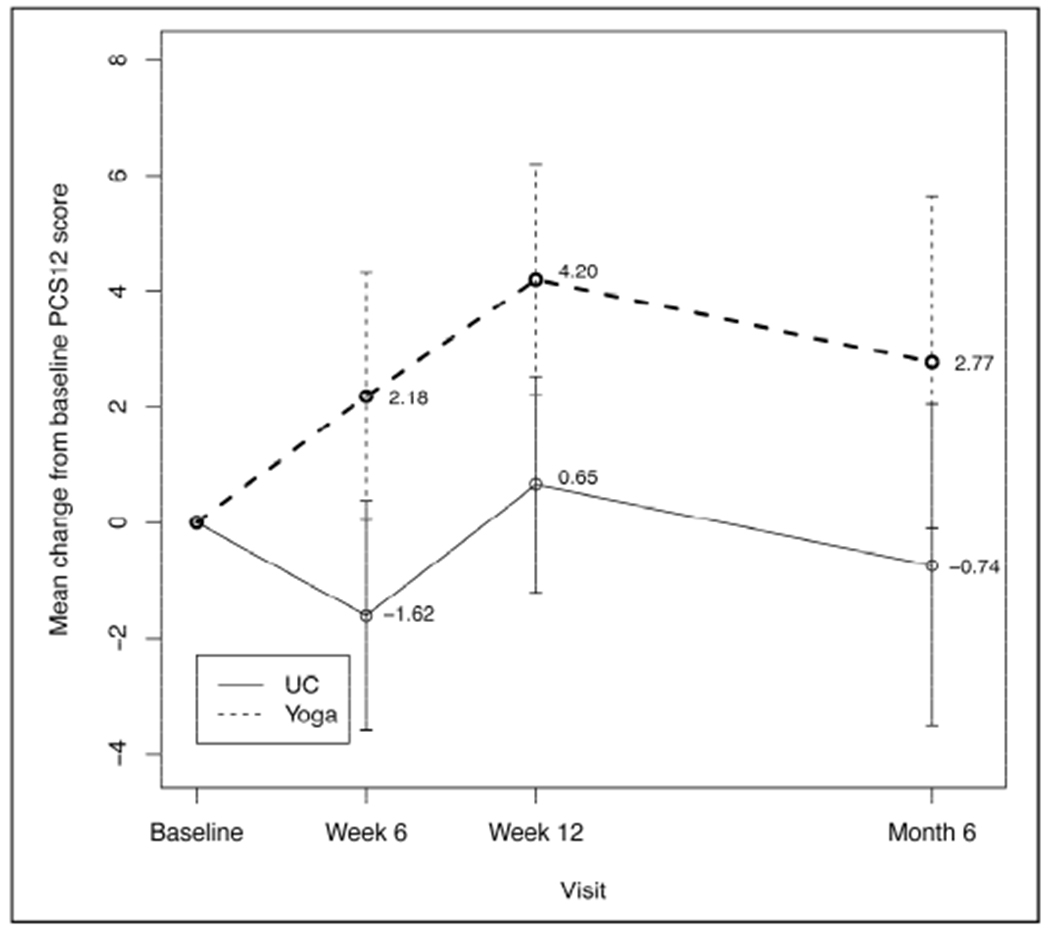

Results on other secondary outcomes (Table 1) indicate that yoga participants reported significantly greater decreases in pain interference at 12 weeks (p = 0.044; Fig. 1); significantly greater decreases in fatigue at 6 weeks (p = 0.027), 12 weeks (p < 0.001), and 6 months (p = 0.003; Fig. 2); significantly greater increases in SF-12 physical QOL at 6 weeks (p = 0.011) and 12 weeks (p = 0.012; Fig. 3); significantly greater increases in global QOL (EQ-5D) at 6 months (p = 0.002); and significantly greater increases in self-efficacy at 12 weeks (p = 0.031). No significant differences over time were found between the intervention groups on depression, anxiety, or sleep quality.

Table 1.

Linear Mixed-Effects Model of Change at Post-Baseline Visit in Secondary Outcomes

| Variable | Mean Baseline Score (SD) | 6 wk (95% CI) | p Value | 12 wk (95% CI) | p Value | 6 mo (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain interference | |||||||

| Yoga | 4.73 (2.18) | −0.60 (−1.05, −0.16) | −0.94 (−1.39, −0.49) | −0.63 (−1.08, −0.17) | |||

| Delayed treatment | 4.77 (2.54) | −0.14 (−0.56, 0.28) | −0.31 (−0.73, 0.11) | −0.17 (−0.60, 0.27) | |||

| Between-group difference | −0.46 (−1.07, 0.15) | 0.137 | −0.63 (−1.25, −0.02) | 0.044* | −0.46 (−1.09, −0.17) | 0.155 | |

| Fatigue | |||||||

| Yoga | 39.3 (12.5) | −2.34 (−4.78, 0.10) | −5.77 (−8.21, −3.32) | −4.97 (−7.56, −2.38) | |||

| Delayed treatment | 38.9 (13.3) | 1.47 (−0.84, 3.77) | 0.61 (−1.70, 2.92) | 0.80 (−1.62, 3.22) | |||

| Between-group difference | −3.81 (−7.16, −0.45) | 0.027* | −6.38 (−9.74, −3.02) | < 0.001† | −5.37 (−8.83, −1.91) | 0.003** | |

| SF-12 Physical | |||||||

| Yoga | 36.3 (9.29) | 2.18 (0.05, 4.32) | 4.20 (2.20, 6.19) | 2.77 (−0.10, 5.64) | |||

| Delayed treatment | 36.2 (10.5) | −1.62 (−3.60, 0.38) | 0.65 (−1.22, 2.53) | −0.74 (−3.53, 2.04) | |||

| Between-group difference | 3.80 (0.88, 6.72) | 0.011* | 3.54 (0.81, 6.28) | 0.012* | 3.51 (−0.48, 7.51) | 0.086 | |

| SF-12 Mental | |||||||

| Yoga | 37.7 (6.95) | 0.23 (−1.52, 1.99) | −0.10 (−1.90, 1.71) | −1.62 (−4.15, 0.92) | |||

| Delayed treatment | 37.8 (6.50) | 0.47 (−1.22, 2.16) | −0.48 (−2.21, 1.26) | −0.50 (−3.01, 2.02) | |||

| Between-group difference | −0.24 (−2.68, 2.20) | 0.848 | 0.38 (−2.12, 2.88) | 0.767 | −1.12 (−4.69, 2.45) | 0.539 | |

| EQ-5D global QOL | |||||||

| Yoga | 0.66 (0.19) | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.06) | 0.08 (0.03, 0.12) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.10) | |||

| Delayed treatment | 0.66 (0.21) | −0.001 (−0.04, 0.04) | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.06) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.04) | |||

| Between-group difference | 0.014 (−0.05, 0.07) | 0.656 | 0.06 (−0.003, 0.12) | 0.065 | 0.06 (0.001, 0.13) | 0.047* | |

| Depression | |||||||

| Yoga | 13.7 (4.97) | −1.12 (−2.18, −0.06) | −1.80 (−2.85, −0.75) | −1.75 (−2.81, −0.60) | |||

| Delayed treatment | 13.3 (4.87) | −0.12 (−1.11, 0.87) | −0.73 (−1.72, 0.26) | −0.81 (−1.86, 0.24) | |||

| Between-group difference | −1.00 (−2.45, 0.45) | 0.179 | −1.07 (−2.51, 0.37) | 0.147 | −0.94 (−2.43, 0.56) | 0.220 | |

| Anxiety | |||||||

| Yoga | 16.2 (11.4) | −1.79 (−3.69, 0.10) | −1.51 (−4.01, 0.99) | −2.81 (−5.34, −0.29) | |||

| Delayed treatment | 15.3 (12.7) | 0.26 (−1.62, 2.14) | −0.39 (−2.80, 2.02) | −0.82 (−3.30, 1.66) | |||

| Between-group difference | −2.05 (−4.72, 0.61) | 0.132 | −1.12 (−4.59, 2.35) | 0.527 | −2.00 (−5.53, 1.54) | 0.269 | |

| Sleep quality | |||||||

| Yoga | 11.4 (3.66) | −1.18 (−2.02, −0.34) | −1.49 (−2.33, −0.65) | −1.73 (−2.60, −0.86) | |||

| Delayed treatment | 10.5 (3.86) | −0.28 (−1.08, 0.52) | −0.98 (−1.79, −0.18) | −0.88 (−1.71, −0.04) | |||

| Between-group difference | −0.90 (−2.06, 0.26) | 0.127 | −0.51 (−1.67, 0.66) | 0.392 | −0.85 (−2.06, 0.35) | 0.166 | |

| Self-efficacy | |||||||

| Yoga | 5.73 (2.02) | −0.06 (−0.52, 0.40) | 0.26 (−0.20, 0.72) | 0.04 (−0.43, 0.51) | |||

| Delayed treatment | 6.04 (2.32) | −0.28 (−0.71, 0.15) | −0.44 (−0.88, −0.01) | −0.37 (−0.82, 0.08) | |||

| Between-group difference | 0.22 (−0.41, 0.85) | 0.492 | 0.70 (0.07, 1.33) | 0.031* | 0.41 (−0.24, 1.06) | 0.214 |

Figure 1.

Mean Change in Pain Interference Scores

BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; UC = usual care.

Figure 2.

Mean Change in Fatigue Scores

FSS = Fatigue Severity Scale; UC = usual care.

Figure 3.

Mean Change in Physical Quality-of-Life Scores

PCS12 = physical component of Short-Form 12 (SF-12) QOL measure; UC = usual care.

Discussion

Secondary outcomes from an RCT of yoga for military veterans with cLBP are presented. The main results of the study, showing that disability and back pain intensity improved more among yoga participants, were published earlier.27 Yoga participants had significantly greater improvements on secondary outcomes, including pain interference, fatigue, various aspects of QOL, and self-efficacy, than the comparison group. These findings add valuable data on health outcomes that are not always reported or measured in similar studies.20,21

Coinciding with our finding on self-efficacy for managing pain, Tilbrook et al.21 reported that yoga participants had larger increases in pain self-efficacy compared with a usual-care group, but no differences were found for QOL (SF-12). Our finding that pain interference was reduced after yoga participation is similar to a result from a study that compared yoga for cLBP to stretching or self-care and found that yoga participants had less pain “bothersomeness” at 12 weeks.20 Pain bothersomeness and pain interference are slightly different constructs, but both attempt to quantify the self-reported consequences of pain on one’s life. That study did not, however, report other comparable secondary outcomes.

The health outcome on which the intervention groups differed the most over time was fatigue. Fatigue has not been measured in most large trials of yoga for cLBP or in cLBP trials more generally. However, scientific literature does conclude that chronic pain leads to or causes increased fatigue.42,43 Although the mechanisms of this process are complex, people who are coping with chronic pain report less energy available for activities. Greater reductions in fatigue among yoga participants have been reported before in a nonrandomized pre-post trial of yoga for veterans with cLBP.24,25

Improved HRQOL among participants assigned to yoga was evidenced on two different measures, the SF-12 PCS (physical component score) and the EQ-5D. The SF-12 and its parent measure, the SF-36, have been used in a number of previous trials of yoga for cLBP. As noted above, Tilbrook et al.21 did not find any difference between yoga participants and usual-care participants on the SF-12, despite yoga participants having greater improvement in back function over time. Saper et al.44 found that participant groups attending either once- or twice-weekly yoga both had significant improvements on the SF-36 physical score, but only the one-weekly yoga group had significant increases in SF-36 mental scores. A separate study comparing yoga to physical therapy and health education also found significant increases over time on the SF-36 using a noninferiority design, but no group differences were found.45 However, comparisons are difficult to make because these studies used the broader SF-36 and did not have usual-care comparison groups.

The EQ-5D is a preference-based measure that provides a single summary score ranging from 0.0 to 1.0; it is useful for calculating quality-adjusted life years for cost-effectiveness analysis.37 No studies of yoga specifically for cLBP were located that measured HRQOL with the EQ-5D measure. However, a cost-effectiveness study of yoga for managing musculoskeletal conditions in the workplace did find significantly greater improvements in yoga participants over time.46 In comparison to those findings, the size of the mean difference over time in the study presented here was about twice as large. With the minimum clinically important difference for the EQ-5D ranging from 0.3–0.5 in chronic pain studies,47,48 the yoga intervention in the current trial had a clinically important effect across all randomized participants.

A number of unique aspects of the study may limit generalizability or conclusions and should be considered. This was the first RCT of yoga for cLBP among military veterans and in VA patients more specifically. Overall, VA patients face more health challenges, with about 45% having a military service–connected disability. When compared to samples studied in previous RCTs of yoga for cLBP, the current sample had a higher mean age, higher unemployment and history of homelessness, less education, a 50% longer duration of cLBP, and higher rates of opioid medication use at baseline. Coinciding with these greater challenges, our sample had lower attendance rates, more attrition from assessments, and slightly smaller effect sizes across some outcomes.27 However, attrition rates remained within guidelines indicating no major concern of bias.52 Analyses to examine systematic attrition have been reported previously, finding no differences between completers and attriters and thus no evidence of bias.27

Conclusions

In addition to significantly larger reductions in back-related disability and pain severity, U.S. veterans with cLBP who were assigned to a yoga intervention had greater improvements in pain interference, fatigue, QOL, and self-efficacy compared to a DT comparison group. These results provide additional support for concluding that yoga is a beneficial treatment for many people with cLBP and can improve multiple aspects of health and function. The results also indicate that yoga can be effective in diverse populations, including those facing greater challenges with attendance and a wider profile of comorbid conditions. Additionally, the study demonstrated that a 12-week intervention in this population can have durable effects observable 3 months later. The results support ongoing efforts to expand the availability of mind-body interventions in the VA Healthcare System, especially for veterans with chronic pain.

Supplementary Material

1

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from VA Rehabilitation Research and Development (VA RR&D grant # RX000474). This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02524158).

We thank Ilanit Young and Eric Eichler, who donated time as yoga instructors for delayed-treatment sessions, and Debora Goodman, Meghan Maiya, Neil Yetz, and Danielle Casteel, who assisted with assessments.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial relationships to disclose.

References

- 1.Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CW, Macedo LG, McAuley J, & Maher C (2010). An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. European Spine Journal, 19(12), 2075–2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson GBJ (1997). The epidemiology of spinal disorders. In Frymoyer J (Ed.), The adult spine: Principles and practice (2nd ed.). New York: Raven Press, 93–141. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goulet JL, Kerns RD, Bair M, Becker WC, Brennan P, Burgess DJ, … Brandt CA (2016). The musculoskeletal diagnosis cohort: Examining pain and pain care among veterans. Pain, 157(8), 1696–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerns RD, Otis J, Rosenberg R, & Reid MC (2003). Veterans’ reports of pain and associations with ratings of health, health-risk behaviors, affective distress, and use of the healthcare system. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 40(5), 371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lew HL, Otis JD, Tun C, Kerns RD, Clark ME, & Cifu DX (2009). Prevalence of chronic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, and persistent postconcussive symptoms in OIF/OEF veterans: Polytrauma clinical triad. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 46(6), 697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo HR, Tanaka S, Halperin WE, & Cameron LL (1999). Back pain prevalence in US industry and estimates of lost workdays. American Journal of Public Health, 89(7), 1029–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Currie SR, & Wang J (2004). Chronic back pain and major depression in the general Canadian population. Pain, 107(1-2), 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan MJ, Reesor K, Mikail S, & Fisher R (1992). The treatment of depression in chronic low back pain: Review and recommendations. Pain, 50(1), 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burström K, Johannesson M, & Diderichsen F (2001). Swedish population health-related quality of life results using the EQ-5D. Quality of Life Research, 10(7), 621–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosinski MR, Schein JR, Vallow SM, Ascher S, Harte C, Shikiar R, … Vorsanger G (2005). An observational study of health-related quality of life and pain outcomes in chronic low back pain patients treated with fentanyl transdermal system. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 21(6), 849–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, & Martin BI (2006). Back pain prevalence and visit rates: Estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine, 31(23), 2724–2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, Birbeck G, Burstein R, Chou D, … U.S. Burden of Disease Collaborators. (2013). The state of US health, 1990-2010: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA, 310(6), 591–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT Jr., Shekelle P, … American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel. (2007). Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147(7), 478–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou R, & Huffman LH (2007). Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: A review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147(7), 505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banerjee G, Edelman EJ, Barry DT, Becker WC, Cerdá M, Crystal S, … Marshall BD (2016). Non-medical use of prescription opioids is associated with heroin initiation among US veterans: A prospective cohort study. Addiction, 111(11), 2021–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller M, Barber CW, Leatherman S, Fonda J, Hermos JA, Cho K, & Gagnon DR (2015). Prescription opioid duration of action and the risk of unintentional overdose among patients receiving opioid therapy. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175(4), 608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Iorio D, Henley E, & Doughty A (2000). A survey of primary care physician practice patterns and adherence to acute low back problem guidelines. Archives of Family Medicine, 9(10), 1015–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freburger JK, Carey TS, & Holmes GM (2005). Physician referrals to physical therapists for the treatment of spine disorders. Spine Journal, 5(5), 530–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Hashimoto R, Weimer M, … Brodt ED (2017). Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: A systematic review for an American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Annals of Internal Medicine, 166(7), 493–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Wellman RD, Cook AJ, Hawkes RJ, Delanye K, & Deyo RA (2011). A randomized trial comparing yoga, stretching, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(22), 2019–2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tilbrook HE, Cox H, Hewitt CE, Kang’ombe AR, Chuang LH, Jayakody S, … Torgerson DJ (2011). Yoga for chronic low back pain: A randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 155(9), 569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, & Layde PM (2000). Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160(21), 3252–3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finney JW, Willenbring ML, & Moos RH (2000). Improving the quality of VA care for patients with substance-use disorders: The Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) substance abuse module. Medical Care, 38(6 Suppl. 1), I105–I113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groessl EJ, Weingart KR, Aschbacher K, Pada L, & Baxi S (2008). Yoga for veterans with chronic low-back pain. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 14(9), 1123–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groessl EJ, Weingart KR, Johnson N, & Baxi S (2012). The benefits of yoga for women veterans with chronic low back pain. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 18(9), 832–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groessl EJ, Schmalzl L, Maiya M, Liu L, Goodman D, Chang DG, … Baxi S (2016). Yoga for veterans with chronic low back pain: Design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 48, 110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groessl EJ, Liu L, Chang DG, Wetherell JL, Bormann JE, Atkinson JH, … Schmalzl L (2017). Yoga for military veterans with chronic low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(5), 599–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roland M, & Fairbank J (2000). The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine, 25(24), 3115–3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cleeland CS, & Ryan KM (1994). Pain assessment: Global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 23(2), 129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, & Cleeland CS (2004). Validity of the Brief Pain Inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 20(5), 309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, & Steinberg AD (1989). The Fatigue Severity Scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Archives of Neurology, 46(10), 1121–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pepper CM, Krupp LB, Friedberg F, Doscher C, & Coyle P K. (1993). A comparison of neuropsychiatric characteristics in chronic fatigue syndrome, multiple sclerosis, and major depression. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 5(2), 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, & Patrick DL (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenkinson C, Layte R, Jenkinson D, Lawrence K, Petersen S, Paice C, & Stradling J (1997). A shorter form health survey: Can the SF-12 replicate results from the SF-36 in longitudinal studies? Journal of Public Health Medicine, 19(2), 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaplan RM, Tally S, Hays RD, Feeny D, Ganiats TG, Palta M, & Fryback DG (2011). Five preference-based indexes in cataract and heart failure patients were not equally responsive to change. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(5), 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kind P (1996). The EuroQol instrument: An index of health-related quality of life. In Spilker B (Ed.), Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, & Steer RA (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fydrich T, Dowdall D, & Chambless DL (1992). Reliability and validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 6(1), 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorig K (1996). Outcome measures for health education and other health care interventions. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, & Kupfer DJ (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buckley RC (2018). Chronic pain and fatigue: Timescale, feedback, and overrides. Pain, 159(7), 1429–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Damme S, Becker S, & Van der Linden D (2018). Tired of pain? Toward a better understanding of fatigue in chronic pain. Pain, 159(1), 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saper RB, Boah AR, Keosaian J, Cerrada C, Weinberg J, & Sherman KJ (2013). Comparing once- versus twice-weekly yoga classes for chronic low back pain in predominantly low income minorities: A randomized dosing trial. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/658030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saper RB, Lemaster C, Delitto A, Sherman KJ, Herman PM, Sadikova E, … Weinberg J (2017). Yoga, physical therapy, or education for chronic low back pain: A randomized noninferiority trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 167(2), 85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hartfiel N, Clarke G, Havenhand J, Phillips C, & Edwards RT (2017). Cost-effectiveness of yoga for managing musculoskeletal conditions in the workplace. Occupational Medicine, 67(9), 687–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parker SL, Mendenhall SK, Shau DN, Adogwa O, Anderson WN, Devin CJ, & McGirt MJ (2012). Minimum clinically important difference in pain, disability, and quality of life after neural decompression and fusion for same-level recurrent lumbar stenosis: Understanding clinical versus statistical significance. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine, 16(5), 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soer R, Reneman MF, Speijer BL, Coppes MH, & Vroomen PC (2012). Clinimetric properties of the EuroQol-5D in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine Journal, 12(11), 1035–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2015). Annual benefits reports, 2000 to 2013; Veterans Health Administration, Table A: VHA Enrollment, Expenditures, and Patients National Vital Signs, September Reporting 2000 to 2013. In: Veterans Benefits Administration OoPaP, ed. Washington, DC: National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 50.U. S. Census Bureau. (2015). Service-connected disability rating status and ratings for civilian veterans 18 years and over. 2015 American community survey 1-year estimates. Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

- 51.U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. (2016). Unique veteran users profile FY 2015. pp. 4, 16. Retrieved from www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Unique_Veteran_Users_2015.pdf

- 52.Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M, & Editorial Board CBRG. (2009). 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine, 34(18), 1929–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1